William Krist's Blog, page 22

October 3, 2022

Trade and Development Report 2022

Chapter I: Global Trends and Prospects

A. TOO CLOSE TO THE EDGE

1. A year of serial crises

After a rapid but uneven recovery in 2021, the world economy is in the midst of cascading and multiplying crises. With incomes still below 2019 levels in many major economies, growth is slowing everywhere. The cost-of-living crisis is hurting the majority of households in advanced and developing countries. Damaged supply chains remain fragile in key sectors. Government budgets are under pressure from fiscal rules and highly volatile bond markets. Debt-distressed countries, including over half of low-income countries and about a third of middle-income countries, are edging ever closer to default. Financial markets are jittery, as questions mount about the reliability of some asset classes. The vaccine roll-out has stalled, leaving vulnerable countries and communities exposed to new outbreaks of the pandemic. Against this troubling backdrop, climate stress is intensifying, with mounting loss and damage in vulnerable countries who lack the fiscal space to deal with disasters, let alone invest in their own long-term development. In some countries, the economic hardship resulting from these compounding crises is already triggering social unrest that can quickly escalate into political instability and conflict.

The resulting policy challenges are daunting, especially in an international system marked by rising distrust. At the same time, the institutions of global economic governance, tasked since 1945 with mitigating global shocks, delivering international public goods and providing a global financial safety net, have been hampered by insufficient resources and policy tools and options that are “rigid and old fashioned” (Syed, 2022; Yellen, 2022). Even as growth in advanced economies slows down more sharply than anticipated in last year’s Report, the attention of policymakers has become much too focused on dampening inflationary pressures through restrictive monetary policies, with the hope that central banks can pilot the economy to a soft landing, avoiding a full-blown recession. Not only is there a real danger that the policy remedy could prove worse than the economic disease, in terms of declining wages, employment and government revenues, but the road taken would reverse the pandemic pledges to build a more sustainable, resilient and inclusive world (chapter III).

As noted in last year’s Report, the pandemic caused greater economic damage in the developing world than the global financial crisis. Moreover, with their fiscal space squeezed and inadequate multilateral financial support, these countries’ bounce back in 2021 proved uneven and fragile, dependent in many cases on a further build-up in external debt. The immediate prospects for many developing and emerging economies will depend, to a large extent, on the policy responses adopted in advanced economies. The rising cost of borrowing and a reversal of capital flows, combined with a sharper than expected slowing of China’s growth engine and the economic repercussions from the war in Ukraine, are already dampening the pace of recovery in many developing countries, with the number of those in debt distress rising, and some in default. With 46 developing countries already severely exposed to financial pressure from the high cost of food, fuel and borrowing, and more than double that number exposed to at least one of those threats, the possibility of a widespread developing country debt crisis is a very real one, evoking painful memories of the 1980s and ending any hope of meeting the sustainable development goals (SDGs) by the end of the decade.

The acceleration of inflation beginning in the second half of 2021 (figure 1.1) and continuing even as economic growth began to slow down in the final quarter of the year has led many to draw parallels with the stagflationary conditions of the 1970s. Despite the absence of the wage-price spirals that characterized that decade, policymakers appear to be hoping that a short sharp monetary shock – along the lines, if not of the same magnitude, as that pursued by the United States Federal Reserve (the Fed) under Paul Volker – will be sufficient to anchor inflationary expectations without triggering recession. Sifting through the economic entrails of a bygone era is unlikely, however, to provide the forward guidance needed for a softer landing given the deep structural and behavioural changes that have taken place in many economies, particularly those related to financialization, market concentration and labour’s bargaining power.

UNCTAD

To read the full report, please click here.

The post Trade and Development Report 2022 appeared first on WITA.

September 30, 2022

Nature Dependent Exporters: What Do They Have in Common?

Planet Tracker set out to identify those territories and countries which are dependent on nature for export trade revenues. To do so, natural resource-based exports are defined rather narrowly, excluding ecotourism and similar non-physical contributions to a nation’s wealth and trade.

This is not to say that experiential values from the environment do not have value. In fact, for some nations, ecotourism is a substantial source of foreign currency. Rather, we are interested in the dependency of nations specifically on physical goods traded in the international market. These are goods which are often inputs to other production processes and any shocks to global markets will be experienced by their producers first and then reverberate through the rest of the global supply chain.

The forms of natural capital are then further divided into renewables such as agricultural, forestry and seafood products, and non-renewables such as oil and gas, minerals, metals and ores. This division occurs because the dynamics of renewable versus non-renewable resources – the decision-making processes involved – tend to be different in many respects.

The definition of export dependency on nature is based on trade data covering 5,000 different product categories which are then sorted into whether they are directly dependent on natural capital. We recognize that all goods are at least partially dependent on nature. To make the approach actionable, we establish cut-off points. A product which is processed but remains almost entirely made of materials that are harvested from nature, e.g. soybean oil extracted from the seeds of the soybean, is classified as nature dependent. Where a product is changed physically or chemically in a way that makes the product significantly different from its original form, e.g. limestone, marl and clay which are converted into cement, it is excluded.

Following this logic, all complex manufactured goods coming from, for example, the chemical, plastic or machinery industries are excluded. The results are then aggregated to arrive at the percentage by value of each nation’s total exported goods that are directly dependent on nature. Their production and export and the relationship to a nation’s stability are of primary interest in this study. As all nations’ exports are at least in part dependent on nature, we use the term Nature Dependency of Exporters, alternatively Nature Dependent Exporters (NDEs) based on their level of natural resource exports and classify countries into high (HNDE), medium (MNDE) and low (LNDE) groups.

Having established NDE groups, for both renewable and non-renewable resources, Planet Tracker then compares the data using a set of common characteristics. Of primary interest, we explore whether there is a typical profile of HNDEs, exploring what characteristics they may have in common, using twelve metrics and a holistic, exploratory method to discover similarities.

NDE-report

By Filippo Grassi: Data Analyst, Planet Tracker. Dr. Zachary Turk: Visiting Fellow, Department of Geography and Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science; Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter, Agrar- und Umweltwissenschaftliche Fakultät, Universität Rostock. Professor Ben Groom: Dragon Capital Chair in Biodiversity Economics, Land, Environmental Economics and Policy (LEEP) Institute Department of Economics, University of Exeter Business School; Visiting Professor Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment London School of Economics and Political Science. John Willis: Director of Research, Planet Tracker.

To read the original report by Planet Tracker, click here.

The post Nature Dependent Exporters: What Do They Have in Common? appeared first on WITA.

September 1, 2022

Developing Public-Private Partnerships to Support the Goals of the IndoPacific Economic Framework (IPEF)

As officials gather in Los Angeles for the IPEF ministerial this week, ALI releases its newest report, Developing Public-Private Partnerships to Support the Goals of the IndoPacific Economic Framework (IPEF). Given that IPEF is a new type of trade agreement, which doesn’t include tariff concessions, the report examines how using U.S. government capacity-building resources to create public-private partnerships (PPPs) with American companies and civil society could provide incentives for IPEF member countries. Launching a robust PPP initiative as part of IPEF would both demonstrate U.S. regional leadership and incentivize member countries to advance IPEF’s goals.

A program which galvanizes U.S. investment in the region will also be an important counterpart to China’s presence in the region. While the U.S. will never match China’s funding dollar for dollar, it can work with IPEF partners to create different terms and standards for Indo-Pacific investment as concerns grow over China’s abusive lending terms, corrosive capital, and environmental standards. The U.S. emphasis on creating resilient supply chains, advancing digitization, increasing decarbonization, and raising labor and environmental standards will spur growth, while enhancing U.S. leadership in the region. It will also strengthen U.S. national security and boost the economic future of our workers and businesses.

The report starts by recommending the creation of an IPEF Partnership Program entity, examines capacity-building funding available in U.S. government agencies, and highlights examples of PPP projects which could be replicated in the IPEF countries.

Developing+Public-Private+Partnerships+to+Support+the+Goals+of+the+IndoPacific+Economic+Framework

By Dr. Orit Frenkel, CEO and co-founder of the American Leadership Initiative and Rebecca Karnak, Director of Digital Projects at the American Leadership

Initiative.

To read the original report by the American Leadership Initiative, please click here.

The post Developing Public-Private Partnerships to Support the Goals of the IndoPacific Economic Framework (IPEF) appeared first on WITA.

August 30, 2022

Biden could reduce inflation, mitigate a recession, and strengthen democracy with a new EU-US trade agreement

On both sides of the Atlantic, economies are showing signs of turmoil: Inflation is at the highest level in more than 40 years, the U.S. stock market has plunged significantly since its peak on January 3, and expectations for a recession are increasing both in the EU and in the U.S., particularly as the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank are aggressively increasing interest rates to combat inflation. At the same time, the Russian war against Ukraine—with implicit support from China—has underlined the importance of the transatlantic partnership as a democratic bulwark against brutal authoritarian regimes and as a pillar of stability in the world. Policymakers looking for solutions to combat rapidly rising prices—fueled by a mix of supply chain bottlenecks (leading to a shortage of certain goods), rising energy prices, and heightened consumer demand—have largely turned to traditional monetary policy by raising interest rates, risking recession.

However, unfortunately, neither policymakers in the U.S. nor in the EU have so far publicly considered an additional policy measure which could solve several problems at once: to revive and complete an EU-U.S. free trade agreement, building on the Obama administration’s efforts to establish the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). A TTIP successor would not only have the potential to significantly ease existing supply chain woes and reduce inflation in the medium-term but also increase economic growth on both sides of the Atlantic, thereby reducing the risk of a prolonged recession in the U.S. and the EU. While reviving an EU-U.S. free trade agreement will take some time, central bankers now expect that inflation pressures might last longer than expected and that we might not be returning to the low-inflation environment we faced before the pandemic. This underscores the importance of finding other policy measures that curb inflation but do not reduce economic growth. Moreover, an EU-U.S. free trade agreement would lead to greater integration between these two vital blocs, deepening economic and political ties in line with the existing close military ties, increasing regulatory harmonization, and building a more coherent counterweight to the increasingly assertive authoritarian alliance between Russia and China. Reviving a TTIP successor could help improve the economy, reduce inflation, and strengthen ties with our democratic allies.

President Biden would have a good basis to restart negotiations with the EU by building on the far-reaching efforts to implement TTIP by the Obama administration. Before the Trump administration scuttled TTIP and antagonized the EU by imposing tariffs on European goods, President Obama had made significant progress in negotiating an EU-U.S. free trade agreement after launching talks in 2013. The U.S. could pick up where it left off in 2016 by adopting the provisions settled by the initial 15 rounds of negotiations and renewing these talks.

TTIP would have effectively eliminated 98-100% of tariffs, reduced non-tariff barriers to trade with Europe by 10-25%, and been the largest trade deal in history (see Appendix Table 1 for an overview of tariff reductions). Based on estimates of the impact of TTIP on the U.S. economy, wages for high- and low-skilled U.S. workers would have increased, U.S. exports would have spiked, and millions of American jobs would have been created. The deal would have also spurred broad economic growth by increasing U.S. GDP an estimated 0.2-0.4%, or about $75 billion annually.[1] For the EU, TTIP would have increased GDP by 0.3-0.5%, or about $64 billion annually.[2]

Importantly, an often-overlooked benefit of free trade agreements is that they can ease inflationary pressures by streamlining trade between nations, thus increasing the supply of goods and reducing prices. That is, rather than curb demand as interest rate increases do, free trade works through the supply side. Because the current inflation spike can at least partly be attributed to stresses on supply chains, a free trade agreement inducing greater supply would be one step to help ameliorate the magnitude of inflation. By bolstering supply chains, a new free trade agreement would also help relieve shortages of certain goods that have persisted since the pandemic, such as the recent baby formula shortage, and ensure greater access to essential products.

THE EXPECTED BENEFITS OF AN EU-U.S. FREE TRADE AGREEMENT

Economic growth and jobs

The economics behind free trade is clear: Liberalizing trade between two economies increases competition by expanding market access to firms and encouraging firm entry. The lower barriers to entry and resultant increase in competition drives down prices for the consumer and helps to mitigate market concentration. This core argument has been proved by numerous empirical research studies in the past few decades.

While the U.S. does have “most favored nation” status with the EU, American exporters still faced an average 5.2% tariff to the EU in 2018. This was even higher for agricultural products at 12%. Many U.S. industries that ship non-agricultural products could benefit from a free trade agreement as well, including fish and seafood, which incur up to a 26% EU tariff, trucks at 22%, and passenger vehicles and processed wood products, each at 10%.

The effects of TTIP would have been far-reaching because of how large the transatlantic trade market is. A 2014 European report valued all goods and services traded between the EU and the U.S. at 517 and 376 billion euros, respectively. By liberalizing trade, TTIP would have increased total U.S. exports by 11.3% and total U.S. imports by 4.6%, meaning the U.S. trade deficit would have been reduced. Total U.S. exports to Europe would have increased by a staggering 35.7%.

In addition to these broad economic effects, the American worker would have benefitted, too. TTIP would have likely raised wages for low-skilled American workers by 0.4% and for high-skilled American workers by 0.3% (however, these increases in wages would not lead to more expensive goods, since prices would be offset by higher competition and the direct impact of lowering tariffs). Unlike other countries with which the U.S. has free trade agreements, such as Mexico and Colombia, the EU is a high-wage economy. This means American workers would not be directly competing with foreign low-wage workers, alleviating concerns about downward pressure on wages in certain sectors.

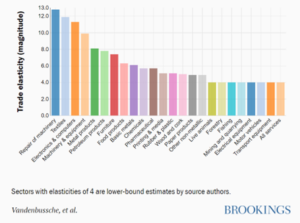

To see which industries stand to benefit most from trade economists generally look at trade elasticity, which measures the proportionate increase in demand after a reduction in trade costs allows the price of a good to decrease. Sectors with higher trade elasticities see higher demand for their products as barriers to trade are reduced. Figure 1 shows trade elasticity by sector.[3]

An economic report co-authored by the Atlantic Council estimated that TTIP would have added over 740,000 jobs to the U.S. economy in total, while a Munich-based think tank estimated that 400,000 jobs would have been created in Europe. Analysis of TTIP shows that the motor vehicle, machinery, furniture, computer and electronics, textiles, and food sectors were among those poised to benefit most from the deal, partly due to their trade elasticities and partly due to the types of goods that comprise EU-U.S. trade. Specifically, one German think tank estimated that TTIP would increase U.S. auto exports to the EU by 250%, while an Atlantic Council report said that the U.S. could increase metal manufacturing exports by 125% and processed food exports by 102%. The increase in motor vehicle exports would have been especially important to states in the South and Midwest. (Ohio and Illinois would have gained an estimated 27,000 and 30,000 jobs, and Southern states like Texas and Tennessee would have gained 68,000 and 13,000 jobs, respectively.) The West Coast stood to benefit, as well, as they rely most heavily on services trade with the EU, which makes up over one-third of the total services trade industry in all three West Coast states. In fact, with TTIP, all fifty states would have increased their exports to the EU and created jobs.

Figure 1: Magnitude of trade elasticity by sector

Biden’s Treasury secretary, Janet Yellen, has stated that increasing free trade could have “desirable” effects on inflation. Indeed, there is evidence that free trade can help reduce inflation through several mechanisms, particularly if it is part of more permanent, structural changes that can help ease inflationary pressures.

Since the bulk of tariffs are paid by consumers, thereby directly raising the price of goods, eliminating tariffs between the EU and the U.S. would directly lower costs for consumers. It is estimated that TTIP would reduce the consumer price index in the EU by 0.3%, and likely by a comparable amount in the U.S. When combined with the estimated long-term increase in real income of 0.4% and 0.5% for these regions, respectively, goods would broadly become more affordable by increasing the purchasing power of the average consumer. Relatedly, there would be lower barriers to entry for both the EU and U.S. markets for their respective companies, allowing potentially greater room for new market entrants, again increasing competition and lowering costs for consumers. As the World Trade Organization (WTO) simply put it, “protectionism is expensive.”

Free trade has historically brought down prices. In the U.S., WTO estimates that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, both created in the 1990s, have together increased the purchasing power of the American household by up to $2,000 per year. Certain industries that have been targeted by free trade agreements also demonstrate the benefits of trade liberalization. When the WTO reduced trade barriers on textiles in 2005, clothing prices in Europe fell by 15%. The organization also estimates that protectionist food policies in Europe in the 1990s cost the average family $1,500 per year, while a U.S. tariff levied on sugar in 1988 cost Americans $3 billion in one year. These price increases disproportionately hurt lower-income people, since this cohort spends a larger proportion of their money on goods.

To read the full report, click here

The post Biden could reduce inflation, mitigate a recession, and strengthen democracy with a new EU-US trade agreement appeared first on WITA.

August 24, 2022

What Policy Initiatives Advance Friend-Shoring?

Although the spotlight in recent weeks has been on policy developments in the United States, other nations have taken initiatives that smack of friend-shoring. This briefing describes the state of play as of August 2022.

When it comes to friend-shoring, the Biden Administration has willed the ends but not specified the means. Instead, a patchwork of executive and legislative initiatives have been taken—some of which may induce production relocation to allies, while others are tantamount to subsidy-induced import substitution. Developments in other trading powers suggest alternative approaches are feasible, as this note makes clear.

As U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo has noted, the United States has been taking “a dual approach” in tackling supply chain disruptions and strengthening economic resilience – “investing in domestic manufacturing, as well as pursuing ‘friend-shoring’ like-minded partners fully integrated into our supply chains.” In this regard, several high-profile initiatives have been enacted or announced in recent months.

CHIPS and Science Act

One high-profile initiative to address supply chain disruptions will follow the signing into law of the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 (CHIPS Act) in 9 August 2022. With the CHIPS Act, the U.S. extended substantial financial incentives having a total value of USD 52.7 billion to participants in the American semiconductor supply chain. The majority of this funding (USD 39 billion) took the form of manufacturing incentives. In addition, the CHIPS Act provided a 25% investment tax credit for capital expenses when manufacturing semiconductors and associated equipment.

The CHIPS Act primarily sought to encourage the onshoring of manufacturing of semiconductors. However, the Act also included provisions prioritising partnerships with allies and steps to weaken commercial ties with China. Specifically, the Act allocated a USD 500 million to coordinate with foreign governments to support cooperation in secure semiconductor supply chains as well as in the development and adoption of secure telecommunications networks. In this context, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said “this fund will help deepen efforts with key allies and partners in alignment with this historic domestic investment in these critical technology areas.” He further argued that “[the CHIPS and Science Act] is an important step to further prepare our economy for the 21st century and strengthen our regional supply chain diplomacy, including through the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, and the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity.” Apart from the incentives, the Act established guardrails that prevent the recipients of the federal funds from expanding semiconductor manufacturing capacity in countries that present a national security concern to the United States for 10 years.

Inflation Reduction Act

Just a few days after the enactment of CHIPS Act, on 16 August 2022, President Biden signed into law the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022. Arguably, the IRA has friend-shoring elements. The IRA extended and revised a number incentives to related to climate change and energy security, including a number of tax credits and funding to support the production of electric vehicles (EVs), renewable energy technologies, critical minerals. The incentives have an estimated value of USD 369 billion.

Find further timely analyses on globaltradealert.org/reports 2 of 4 Similar to the CHIPS Act, IRA included safeguard provisions against China as well as stronger provisions promoting ‘friend-shoring’ relating to the manufacturing processes as well as sourcing of the materials. More specifically, concerning the tax credits to be provided to electric vehicles (‘EVs’), only vehicles whose final assembly occurs in North America are eligible for the tax credit.

The IRA also included a provision that prohibited manufacturers from benefiting from a tax credit unless they satisfy critical mineral and battery component requirements. Specifically, manufacturers can claim a tax credit if 40% of critical minerals contained in battery “(i) extracted or processed; (a) in the United States, or (b) in any country with which the United States has a free trade agreement in effect; or (ii) recycled in North America”. That sourcing percentage would increase to 80% by 2027.

In terms of battery components, a tax credit can be claimed by an EV manufacturer as long as a 50% of “the value of the components contained in such battery (…) manufactured or assembled in North America”. The percentage would increase to 100% by 2027. On top of this, EVs are barred from a tax credit if any of the battery components including critical minerals were sourced in countries that present a national security concern to the U.S.

Upon the passage of IRA, the Alliance for Automotive Innovation which represents automakers producing over 95% of vehicles sold in the U.S. argued that it will be difficult for the sector to meet the new conditions. Specifically, the CEO of the Alliance for Automotive Innovation John Bozzella has written that of the existing 72 EV brands currently available: “Seventy percent of those EVs would immediately become ineligible when the bill passes.”

Mr. Bozzella also complained about ‘selective’ friend-shoring introduced by IRA and argued that the U.S. is incapable of supplying sufficient critical materials and batteries domestically. In his view, the friend-shoring in the IRA does not go far enough. He proposed the following reform: “Expanding the definition of eligible countries from which batteries, battery components and critical minerals can be sourced to include nations that have collective defense arrangements with the United States, like NATO members, Japan and others. Broadening the list of eligible countries will provide more options to more quickly reduce our reliance on China.”

Defense Production Act

American officials often argue that shortages of critical minerals and materials are one source of vulnerability in U.S. clean energy supply chains. The demand for critical minerals has been rising and is projected to rise further in the coming decades. Meanwhile, the mining and processing of these minerals is seen as dominated by adversaries. To tackle with these vulnerabilities and to strengthen resilience, in the recent months, the Biden Administration has invoked the Defense Production Act (DPA) and authorised a number of subsidies to strengthen the domestic industrial base for these minerals and materials.

The DPA Title III program provides the President a broad set of authorities to ensure the timely availability of essential domestic industrial resources that are critical for national security. However, existing DPA provisions don’t allow outward funding such as developing new mines in foreign countries. For this purpose, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) asked Congress to amend the DPA to allow Pentagon to fund projects in the U.K. and Australia that process strategic minerals used to make electric vehicles and weapons. DoD said in its request to Congress that making Australia and UK eligible for funding under the DPA would “allow the U.S. government to leverage the resources of its closest allies to enrich U.S. manufacturing and industrial base capabilities and increase the nation’s advantage in an environment of great competition.” These legislative requests were complemented by the following ‘friend-shoring’ initiative.

Minerals Security Partnership

On 14 June 2022, the United States together with ‘like-minded’ countries, established the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) with the purpose of creating their own supply chains in critical minerals. The goal was to “ensure that critical minerals are produced, processed, and recycled in a manner that supports the ability of countries to realise the full economic development benefit of their geological endowments.”

Previously, in June 2021, critical minerals and materials were identified in a report by the Biden Find further timely analyses on globaltradealert.org/reports 3 of 4 White House as one of the key products subject to supply chain vulnerabilities along with semiconductors, batteries, and pharmaceuticals. And for these products, it is stated that “the United States must work with allies and partners to diversify supply chains away from adversarial nations”. In fact, in that report the term ‘friend-shoring’ was used for the first time. The MSP initiative can be regarded as the realisation of some of that report’s objectives.

There were antecedents to this Biden Administration move. In his first year of his presidency, in 2017, President Trump issued Executive Order on critical minerals directing the relevant agencies to look for “options for accessing and developing critical minerals through investment and trade with our allies and partners”. Later, in 2020, Trump Administration, acknowledged that “reliance on critical minerals from foreign adversaries constitutes an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States.” President Trump declared a national emergency with the Executive Order on Addressing the Threat to the Domestic Supply Chain from Reliance on Critical Minerals from Foreign Adversaries. One of the policy objectives of the Executive Order was to “reduce the vulnerability of the United States to the disruption of critical mineral supply chains through cooperation and coordination with partners and allies” as well as to “build resilient critical mineral supply chains, including through initiatives to help allies build reliable critical mineral supply chains within their own territories”. In short, the term ‘friend-shoring’ may be new, but key characteristics of this approach can predated the Biden Administration.

Other international initiatives taken by the United States

Apart from MSP, in the recent months, the US announced several international initiatives including Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) in May 2022, and revitalised the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council (TTC) to promote friend-shoring as a fix to supply chain vulnerabilities. The underlying logic in these initiatives is “to collaborate to reduce dependencies on unreliable sources of strategic supply, promote reliable sources in our supply chain cooperation, and engage with trusted partners.” Also, the U.S., Australia, Japan and India (Quad) have committed to develop Rare Earths projects and technologies to challenge China’s dominance in the sector. This partnership will involve loans to mining and refining businesses.

EU: Region-wide subsidies to build capacity in selected sectors

On the other side of Atlantic, the EU has been utilising its Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI) programme to strengthen its “strategic autonomy” and to pursue the goal of supply chain resilience. As of this writing, the European Commission approved three IPCEI projects relating to the microelectronics, batteries, and hydrogen supply chains. Rather than any one EU member state trying to establish each stage in a value chain, “IPCEIs make it possible to bring together knowledge, expertise, financial resources and economic actors throughout the Union.” Since EU member states are by definition allies, these projects embody the essence of friend-shoring—although IPCEI projects have not been characterised in those terms. Still there are limits: the EU acknowledges that IPCEI projects cannot alone solve the dependency on key raw materials.

Furthermore, on 8 February 2022, the European Commission proposed adoption of a European Chips Act, seeking to mobilise more than EUR 43 billion funds through to 2030 with an eye to strengthening semiconductor value-chains within the EU. Specifically, the Act will address semiconductor shortages in the EU and improve EU resilience to supply chain disruptions by building more production capacity. As a result, the EU aims to become more self-sufficient in semiconductor manufacturing and has set a goal of increasing its market share of semiconductor manufacturing from 9% to 20% by 2030. While targeting “reducing excessive dependencies”, the European Chips Act also included friend-shoring component by proposing “building semiconductor international partnerships with like-minded countries”.

Japan: Paying factories to move our of China – home and to South East Asia

Japan adopted a high-profile scheme during the COVID-19 pandemic that appeared to have a Find further timely analyses on globaltradealert.org/reports 4 of 4 friend-shoring element. The underlying logic is familiar: it was argued by Japanese politicians that certain supply chains were over-reliant on sourcing from China. In this context, Cabinet chief secretary Yoshihide Suga highlighted the importance of resilience and said: “We must avoid being overly dependent on certain countries for products or materials and we have to repatriate production sites for the goods necessary for daily life.”

To try to address this apparent problem, Japan created a USD 2.2 billion fund for the relocation of production from abroad, particularly from China, back home or to South East Asian nations. In principle, then, this initiative has a friend-shoring dimension. However, three pertinent facts arose during the implementation of this initiative. First, that the average subsidy payment per recipient was small (around $15 million) and therefore unlikely to materially affect commercial calculation for large scale production facilities. Second, that the Japanese government differentiated between awards to firms to relocate production for goods largely sourced from abroad and awards to firms to build up local production in general. The former are onshoring initiatives while both substitute for imports. And, third, that little or no funding was provided to relocate factories to South East Asia.1 The subsidy limit for the latter was a tenth of the size of that for relocating production to Japan.

Concluding observations

Leading Western economic nations are now developing initiatives with friend-shoring components. This is not to imply that the mutual support between “allies” is central to the design and execution of the supply chain initiatives reviewed here. Nor is there any implication of that a grand strat1 For a discussion of this Japanese initiative see chapter 5 of the 27th Global Trade Alert report, available at https://www.globaltradealert.org/repo.... egy has emerged to marginalise or otherwise denude certain nations of productive capacity. That may well come.

Still, now that these Western initiatives are underway the policy-related content of friend-shoring is coming into focus. For now, by and the large, Western governments are using carrots rather than sticks to advance friend-shoring. Whether that policy mix is sustained will have an important bearing on whether the world trading system fragments further into groups, in particularly in sectors deemed sensitive.

Halit Harput is Senior Trade Policy Analyst at the St.Gallen Endowment for Prosperity through Trade. For the Global Trade Alert initiative he reports on trade-related policy changes by several nations, including the United States. Previously, Halit served as an official in the Turkish Ministry of Trade. He thanks Simon J. Evenett and Johannes Fritz for their comments and guidance on earlier drafts of this note.

To read the full briefing, please click here.

The post What Policy Initiatives Advance Friend-Shoring? appeared first on WITA.

August 18, 2022

The Global Struggle to Respond to an Emerging Two-Bloc World

“It’s not a question of one country or the other per se; it’s really a question of the best deal that we can strike.” Nigerian Foreign Minister Geoffrey Onyeama, November 19, 2021

Even prior to the pandemic and invasion of Ukraine, Europe was struggling to find the best approach to the emerging international dynamics of a post-unipolar world. As the underlying fabric of the rules-based global system gets stretched – between the United States and its partners, China and its growing list of friends, and everyone else in the middle – the sense that a two-bloc world is gradually re-emerging is greater than at any time since the Cold War. It was accelerated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine only a few weeks after China and Russia reaffirmed their “no limits” partnership and committed to solidify their own bloc. European leaders now face some stark realities as the rules-based international order they are used to risks being undermined by this new dynamic.

However, countries all over the world are attempting to respond to shifting global dynamics and a rising China, not just close allies of Beijing or Washington. And Beijing sees what is at stake very clearly: the success or failure of its ambition to regain global power status by 2049 and play a central role in reforming the present international order hangs on how countries outside the traditional “West” respond to its growing strategic footprint and rivalry with the United States.

It is of major importance to European leaders to understand how actors outside the usual grouping of rich, liberal market economies view this changing ecosystem, and how they think about Europe in a complex world of actors who all have agency. To that end, we commissioned eight contributors to describe their countries’ views of China and US-China rivalry. Their analyses cover Bangladesh, Chile, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. The eight countries were chosen for their geographic and cultural diversity, varied levels of development, different government types and varied degrees of proximity to China.

Contributors universally reported that their countries “do not want to ‘choose’” between Beijing and Washington – instead, governments hope to remain in the middle and see what opportunities might emerge out of US-China competition over third countries. However, it is possible these countries may nevertheless be pushed to “choose.” There is therefore a pressing need to understand their interests and perspectives better now, rather than after the fact.

More immediately likely, however, is that these eight countries (and others too often overlooked by European leaders) might choose sides in smaller, specific matters under the rules-based international system. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine provided a glimpse as to how such matters can play out. When the UN General Assembly (UNGA) held a vote in early March 2022 on a resolution to condemn the invasion, 141 countries supported it, 35 abstained, and 5 opposed. Of the eight countries selected (prior to the invasion) for this project:

Abstentions came from Bangladesh and Kazakhstan, countries with close ties to Russia, or to the USSR in the past.

Two votes in support came from Chile and Turkey, which have mutual defense pacts with the United States; the third, Saudi Arabia, is heavily reliant on the United States as a security provider.

The remaining three – Indonesia, Kenya, and Nigeria – also voted in support of the resolution. All have much larger trade flows – all of which are surpluses – with the United States than with Russia.

From a European perspective, it is worth considering how these eight countries, and others in their respective neighborhoods, might exercise their agency and leverage their positions in multilateral institutions. Or within the emerging blocs, if push comes to shove. Compared with modern Russia, China’s vastly larger economic ties with much of the world, coupled with its growing role as a security provider to a swathe of countries, would likely produce very different calculations if UNGA members were asked to vote to condemn something China did. Add to this that Beijing has repeatedly demonstrated willingness to use economic coercion when faced with even minor diplomatic slights. This dynamic begs two questions: would the 141 countries that condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine do the same if China had been the aggressor? What does Europe need to do to enhance its value in the eyes of such countries to shift the calculus in favor of the rules-based system?

Key trends: Chinas narratives in western liberal democracies are not mainstream in the rest of the world

Attitudes towards China in the eight countries diverged widely from the mainstream narratives in developed liberal democracies; the same was true of attitudes to US-China tensions. There were several common trends among the eight, though key differences emerged too.

Economic ties with China have expanded in nearly all eight countries since 2012. Trade with China has grown significantly for most during the last decade. Overall volumes have risen by several multitudes for most, but the trend has brought sizable trade deficits with China for all except two – Chile and Saudi Arabia. Several countries saw imports skyrocket while their exports remained flat. Yet looking at overall trade with all partners, China now takes a much larger share of both imports and exports. It has become – for most – either the largest trading partner, or among the largest. Closer business ties, growing trade, and Chinese inbound investment were generally viewed positively, with some exceptions:

Nigerian companies are concerned at how Chinese imports undercut prices and displace small producers.

Large companies in Chile view China as an opportunity, but smaller companies struggle to compete, especially footwear producers.

MERICS-Papers-On-China-Beyond-blocs-Global-views-on-China-and-US-China-relations_0

To read the full report from Mercator Institute for China Studies, please click here.

The post The Global Struggle to Respond to an Emerging Two-Bloc World appeared first on WITA.

August 12, 2022

A Turning Point for US Climate Progress: Assessing the Climate and Clean Energy Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act

On August 12th, the US House of Representatives passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) after the Senate did the same five days before. The climate change and clean energy investments are the single largest component in the package, out of the many issues that the IRA addresses. When President Biden signs it, the IRA will be the single largest action ever taken by Congress and the US government to combat climate change.

In this report, we provide a detailed assessment of the key energy and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions impacts of this historic legislation. The IRA is a game changer for US decarbonization. We find that the package as a whole drives US net GHG emissions down to 32-42% below 2005 levels in 2030, compared to 24-35% without it. The long-term, robust incentives and programs provide a decade of policy certainty for the clean energy industry to scale up across all corners of the US energy system to levels that the US has never seen before. The IRA also targets incentives toward emerging clean technologies that have seen little support to date. These incentives help reduce the green premium on clean fuels, clean hydrogen, carbon capture, direct air capture, and other technologies, potentially creating the market conditions to expand these nascent industries to the level needed to maintain momentum on decarbonization into the 2030s and beyond.

We also find that the IRA cuts household energy costs by up to an additional $112 per household on average in 2030 than without it, cuts electric power conventional air pollutants by up to 82% compared to 2021, and scales clean generation to supply as much as 81% of all electricity in 2030. The IRA represents major progress by Congress, and at the same time more action will be needed for the US to meet its 2030 target of reducing emissions by 50-52% below 2005 levels. With the IRA enshrined as law, all eyes will be on federal agencies and states, as well as Congress, to pursue additional actions to close the emissions gap.

A-Turning-Point-for-US-Climate-Progress_Inflation-Reduction-Act (1)

To read the full report from the Rhodium Group, please click here.

The post A Turning Point for US Climate Progress: Assessing the Climate and Clean Energy Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act appeared first on WITA.

August 11, 2022

Analysis of Section 301 Tariff Impacts on Imports of Consumer Technology Products

Over the past four years, the United States has waged a trade war with China. In 2018, the Trump administration imposed Section 301 tariffs in response to China’s unfair trade practices, which include forced technology transfer and intellectual property theft. They were also intended to compel U.S. companies to move supply chains out of China. These tariffs are taxes paid by American businesses and consumers.

Americans deserve to know whether the Section 301 tariffs were effective, as well as how they affected our economy more broadly. With that goal in mind, the Consumer Technology Association (CTA) commissioned Trade Partnership Worldwide LLC to develop this report on the impact of the tariffs on the U.S. and global consumer technology industry.

The report shows that consumers and the consumer technology industry paid over $32 billion in tariffs through 2021. That sum has surely grown even larger over the past six months, likely reaching close to $40 billion. As the U.S. economy slowly recovers from several years of shutdowns and snarled supply chains, this means that companies are allocating scarce resources toward tariff payments. Instead, they could be investing in the research and development, equipment, job creation or workforce upskilling that helps bring new and innovative products to market.

Many technology companies, which include global technology companies as well as small businesses and startups, say they can no longer absorb the costs of tariffs without increasing prices for products. This trend is exacerbated by continued global supply chain challenges and higher shipping rates imposed by foreign ocean carriers. For American consumers, this means the technology they love and have come to rely on is less accessible and less affordable. Amid rising prices across all sectors of our economy, removing tariffs is an important step to help fight inflation.

As the report makes clear, the tariffs also failed to substantially shift supply chains. In the United States, Section 301 tariffs did not spur job creation or significant new investments in manufacturing. In fact, employment in the consumer technology industry stagnated and, in some cases, declined throughout the “trade war” period. Further, China remains a manufacturing base and source of finished technology products and inputs for the United States. In fact, imports of Section 301-affected tech products have risen or leveled off since mid-2020, suggesting that Section 301 tariffs are no longer motivating companies to leave China.

Meanwhile, certain U.S. trading partners are benefiting from the U.S.-China trade war. This report shows that production is shifting to markets with fewer barriers to trade: Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Thailand. However, the United States does not currently have free trade agreements with these markets, making it harder for U.S. companies to compete in global markets.

Tariffs have not been an effective approach to addressing our economic disputes with China. They hurt U.S. businesses and consumers.

We call on U.S. policymakers to:

• Eliminate tariffs on consumer technology products to mitigate inflation, lower costs and unlock the innovative power of the U.S. economy.

• Eliminate tariffs on inputs to revitalize U.S. jobs and U.S. manufacturing of technology products.

• Immediately create new and expand existing trade agreements, including with Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia and Thailand, to make manufacturing investments in the U.S. more attractive.

CTA is proud to contribute to the ongoing national discussion on the China Section 301 tariffs, and I hope you find the data and insights contained in this report as compelling as I do.

CTA_Section 301 Tariff Whitepaper

To read the full report from the Consumer Technology Association, please click here.

The post Analysis of Section 301 Tariff Impacts on Imports of Consumer Technology Products appeared first on WITA.

August 5, 2022

Why Conflict Between International Economic and Rights-Based Governance Is Inevitable

International organizations mandated to govern social rights are colliding with international organizations mandated to govern economic development. While disagreeing over the nature of overlap and conflict across international organizations, legal and social science scholars offer various proposals to unify global governance. Those proposals assume that unification will come naturally. That assumption is wrong.

The distinct legal instruments that govern international organizations render conflict inevitable and unification more challenging than commonly believed. By closely examining the pandemic-related activities carried out by the International Labor Organization (ILO), the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in the same forty-one countries, the implications of that conflict become clearer. Governments must choose between competing approaches and activities to the detriment of coherence, national policies, and organizational legitimacy. To protect against those perils, international organizations must cooperate on an in-country basis, which would allow them to negotiate over conflicting policies while respecting their diverse mandates and government constituencies.

To read the full extract, please go to page 7:

(40.1) Full Issue PDF

To read the original report from the Berkley Journal of International Law, please click here.

Desirée LeClercq is an Assistant Professor of International Labor Law, Cornell ILR School & Associate Member of the Law Faculty, Cornell Law School

The post Why Conflict Between International Economic and Rights-Based Governance Is Inevitable appeared first on WITA.

August 2, 2022

Securing Semiconductor Supply Chains: An Affirmative Agenda for International Cooperation

Technological innovation has been a driving force for U.S. global leadership and economic prosperity for over a century. This legacy of innovation largely stands on the foundation of a key component: semiconductor chips, found today in almost all electronic products. Semiconductors are an integral component of various consumer products across industries, including cars, smartphones, and household appliances. But semiconductors can also be used in dual-use goods—products that have both military and civilian applications—such as air guidance systems for both civilian and military aircraft. The tension between economic gain and security risk inherent within dual-use semiconductor goods is heightened in fields with national security implications, such as supercomputing and artificial intelligence (AI). How the government and private sector manage the global value chains (GVCs) of chips will directly affect U.S. global competitiveness and national security going forward.

The past two years have underscored the importance of semiconductors to the U.S. economy and its national security interests. Pandemic-induced spikes in consumer demand boosted semiconductor demand by 17 percent between 2019 and 2021. Global sales reached $555.9 billion in 2021, 26.2 percent more than the year before. Although China remains the largest market in the world for semiconductors, sales in the Americas represented the largest region for industry growth in 2021. However, this spike in demand, along with stagnating investment, inadequate input supplies, and logistics breakdowns, has led to an unprecedented shortage of semiconductors that has reverberated throughout the roughly 200 downstream industries that depend on chips. In the automotive industry alone, it was projected that global semiconductor shortages were responsible for $210 billion in lost revenue as of September 2021. Short-term supply chain disruptions for the semiconductor industry are compounded by long-term geopolitical challenges and the need to rethink what constitutes both secure and resilient supply chains. While China is a top customer for the semiconductor industry, the perception of China has shifted in recent years from potential partner to existential threat. This shift has led companies and countries alike to rethink their dependency on China as both partner and customer. In particular, the Biden administration has sought policies that attempt to accelerate progress and prolong the United States’ innovative edge, while simultaneously dampening China’s influence throughout the semiconductor marketplace. Countries around the world have begun thinking about ways to reduce dependencies on China, enhance supply chain resiliency, and keep costs down.

In the United States, this confluence has manifested in calls for nearshoring and “friend-shoring.” As Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said in April 2022 remarks, “friend-shoring means . . . that we have a group of countries that have strong adherence to a set of norms and values about how to operate in the global economy and about how to run the global economic system, and we need to deepen our ties with those partners and to work together to make sure that we can supply our needs of critical materials.” The key difference between onshoring and friend-shoring is that friend-shoring is not restricted to domestic production, but rather seeks to move production to allied partners.

220802_Reinsch_Semiconductors

To read the full report from CSIS, please click here.

The post Securing Semiconductor Supply Chains: An Affirmative Agenda for International Cooperation appeared first on WITA.

William Krist's Blog