R.M. Kinder's Blog, page 3

May 3, 2021

Revisiting Mary Troy’s Swimming On Hwy N

Recently I reread Mary Troy’s Swimming on Hwy N and was again caught up by the liveliness and depth of the work. It’s surprising, entertaining, filled with quirky characters and odd events–all sharply realistic—and episodic. It encourages a laid-back reader. It’s also a compassionate view of humankind, flaws and all. That reading comes gradually, as Troy guides readers to encounter contradictions, at least dualities, in the characters and values. There’s an underlying unity that subtly establishes authority and draws all the parts to one end: Every person is a complex being, a mixture of good and bad, whose history may be so different from what the surface suggests, that dealing with one person is like dealing with the representative of another country. It’s a broad view of us, the good and the bad, the ideal and the reality. With her usual wry touch, Troy urges us to embrace one another. We needn’t agree or love one another, but we must recognize kinship: we’re in and of the same family.

Troy does this with a cast of characters that grows to an almost uncountable number, suggesting exponentially everyone in the country. Seven characters are the core group, and three of them are the genetic and harshly divided family. Madeline, in her 60s, has retired to the Missouri Ozarks which she distains as uncivlilized. Her unwelcome mother Wanda appears on the scene, the unstable sister Angie aka Misery moves in, and a man Madeline is considering as possible husband number 4, Randy, engages her and her entourage in helping a young AWOL solider and his reluctant lover to escape to Canada. With the aid of another older man, B., in a caravan of 1969 Volkswagon bus and Chevalier car, they cooperate, quarrel, encounter one set back after the other. They also meet and interact with many other characters, e.g. bounty hunters, a militant nun, a volatile patriot, so the community of humans is ever expanding and inclusive. The core group ends up at a family union for Phil, Wanda’s first husband and father to her daughters. All the plots converge here, not yet in Canada, still within the bounds of their own country. This is a remarkable structure—the unfolding of a huge family, a nation, circling or spiraling along the same plot. It seems random, perhaps intuitive, but it’s beautifully done.

The characters are fascinating in themselves. Even the seemingly minor ones add some rich element. Gene, for example, a brain-injured hitchhiker whose greatest goal is to attend his sister’s future, is hampered by his body’s insatiable appetite (ideal goal vs base need) and must accept charity from women he detests and considers crazy. But the real power of Troy’s characters is that taken together they reveal the amorphous nature of values—the relativity that is a natural outcome of individuality, a society of humans. Everyone gets attention in Troy’s worlds, gets to espouse a point of view about something important, because each person is important. They exemplify and even express varying definitions of concepts such as culture, justice, motherhood, god, miracle, family. Wanda is the strongest in this respect, her history and personality so faceted that even at the end she’s a mystery to the reader and possibly to herself. She’s certainly an abusive mother. One example is enough: She struck her seven year old daughter, Angie, in the head with a cast iron skillet. She is also the victim of an abusive mother and a horrific environment. Her character raises questions about memory, language, personal visions, truth. She sees visions that are strangely correct—Gene is a Red Squirrel that harbors death–but may be the result of advancing dementia. She wonders if she speaks from the Indian heritage of her mother and remembered facts or if she makes them up. She doesn’t know. Neither does the reader. Wanda may also have the gift of healing, if such is possible, though perhaps her success is coincidental. She can’t decide which gods, if any, would favor her. She’s not truly religious and not clearly altruistic. She aligns herself with the traditional force of good: “She knew what she was, knew if there was a god and its opposite, as most believed, she was closer to the opposite” (26). Though she may manipulate others and be mostly self-serving, she is honest about her nature and her beliefs. A riveting character, shifting before our eyes. In the history of the family she married into and left, Phil’s family, she was/is an Indian princess, beautiful and exotic, and Phil still loves her. She is comic at times, yes, despicable, and admirable. A great character.

One of the most interesting topics to explore in Troy’s novel is the nature of knowledge—how one acquires it, how one uses it—and Angie is a good focus. Wanda’s youngest daughter, Angie has a “mangled” mind, perhaps resulting from that skillet blow. She takes medication to help her avoid deep depression and inability to communicate and function. Angie has an eidetic memory and can recall and repeat anything she’s read (or heard). At times she loses the connection of thoughts, sentences, and even identifiable words. When she’s “normal” (one questions that word entirely), she inserts bits of esoteric knowledge at odd moments, perhaps that have a hidden meaning to her. But they don’t pertain. Lisette, girlfriend of AWOL Henry, questions what’s the use of knowledge that doesn’t mean anything, and Angie says knowing something, anything, can’t be bad. Her factual blurts, and this argument, have a function in the development of Troy’s novel, as a technique, revealing character, adding bits of color, comic relief, so to speak. They’re also real facts—true—and thus interesting in themselves. They often show a layer of reality that isn’t always pretty, not what we prefer to discuss in polite conversation: a weasel’s penis has a bone; “seventy percent of dust is shed human skin” (101). They function in the story and they function for Angie in her world. They’re a sign of her special ability and the unfathomable loss of power she experiences at times.

(Angie is of particular interest to me because I’ve quarreled with a judgment I heard many years ago, though I can’t recall the authority who voiced it: if you can’t express something, you don’t know it.)

The swimming pool invites some conjecture, too. It must represent a gene pool, the personal one of Madeline. She swims in it in her red bikini, right by Hwy N. She takes it along on the trip north, inflates it in a hotel, shares it with others, ends up having to replace it (it’s stolen along with the bus), and continues on. One assumes that as people travel and mingle, so do genes. I have to admit when Gene the hitchhiker appeared I assumed he was a gene Gene, another underlying play of Troy’s. Such gems of possible meaning and discovery thread the work.

What I remembered most from the first reading was even more evident this time, an assurance that we needn’t be so hard on ourselves, a permission to feel what we feel: Some parents—some people—are bad and it’s okay not to like them, to save yourself from them. It’s okay not to feel guilt about them or the need to accept them. The desire to protect self and to escape is nothing to be ashamed of. Everyone is escaping something, perhaps just boredom. What’s natural to you will out itself. It’s likely that given the correct circumstances each of us is capable of almost anything. How very complex is the mingling of humans, the shaping of self to match the community needs. We need to recognize what great effort might be required to make the smallest gesture. With whom are we speaking? Which cultural world are they from? What are the rules and expectations? What’s the native language? Any trigger words or gestures? This is the world Troy unfolds along this wild ride with characters who are simply reflecting the rest of us.

Swimming on Hwy N. Moon City Press, November 1, 2016.

252 Pages.

April 23, 2021

On Shakespeare’s Birthday, a Double Superlative

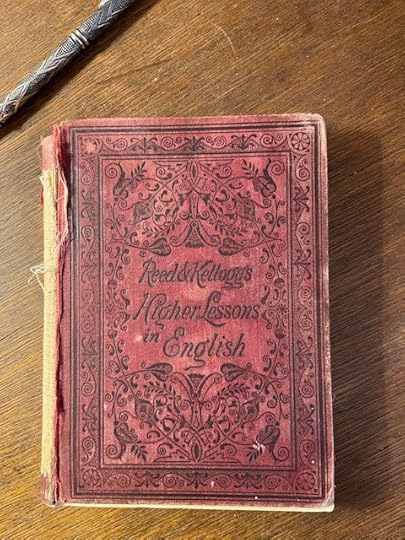

My favorite grammar book is this old Reed and Kellogg Higher Lessons in English, a teacher’s handbook. I believe it was in a box of books my mother was given by two retired teachers, sisters, who lived three houses south of us in Bloomfield, Missouri. I could have acquired it later in life, but on a blank page inside is a sketch I recognize as my early and awkward attempt to draw Cyrano de Bergerac. (I was enamored of Cyrano when young and then again when I saw Steve Martin’s Roxanne.) No grammar book I’ve seen has been better arranged or clearer than this one, and I’ve used it repeatedly, since some rules I simply can’t remember.

An enjoyable feature is the authors’ explanatory footnotes. One is particularly apt today–Shakespeare’s birthday. The note addresses and includes a brief line spoken by Cleopatra’s attendant Charmian as she and another attendant probe a soothsayer about their future (Anthony and Cleopatra, Act I, Scene II). Below is the footnote just as presented in the textbook, including punctuation, italics, and spacing. It references Shakespeare for the double comparative, the Bible for the double superlative.

Double comparatives and double superlatives were formerly used by good writers for the sake of emphasis ; as, Our worser thoughts Heaven mend !—Shakespeare. The most straitest sect.–Bible

The footnote itself is a good example of how language changes over time, as do punctuation and format.

This little line is the real find. “Our worser thoughts, Heaven mend.” It’s a rich statement standing alone, outside the play, not in a comic scene, not even in a tragedy. I may feel that way because I know who wrote it and I know the play. It’s a good plea, though, for any of us, and the word “worser” is perfect.

Alonzo Reed and Brainerd Kellogg, Higher Lessons in English (New York: Maynard, Merrill, & Co., 1895), 226.

March 28, 2021

Churches Omitted in Last Post

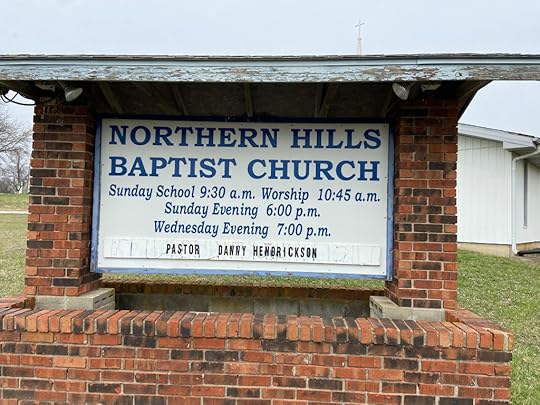

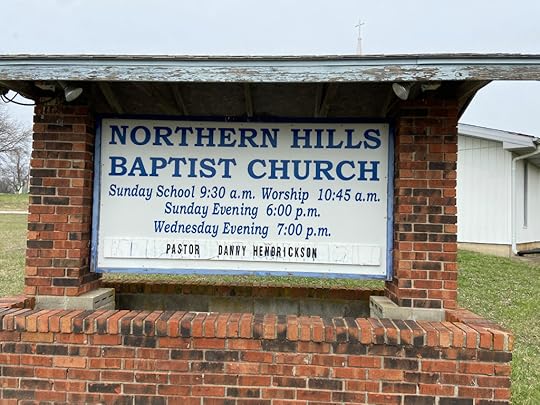

I did omit some Warrensburg churches from my last post. Here they are. I believe there’s another Church of Christ in town but I don’t know where. The one below is on Maguire, where the movie house once was. The sign for Northern Hills Baptist is a repeat in order to accompany the photo of the building–I couldn’t get an angle to capture them together. I just recalled that a Unitarian group meets in the Warrensburg Depot. That’s a beautiful building, too!

Churches used to keep their doors open twenty-four hours a day. In Tucson and during my early years in Warrensburg, I would occasionally drop by a church and just sit on a pew for a while. While I was doing graduate work at the University of Arizona, I asked one of the professors who had a doctorate in comparative religions how he chose to be Catholic when he had studied so many faiths. He said, basically, that there was one god and individuals should choose the faith with which they were comfortable. A Catholic church in Tucson was a favorite place—not during a service, but empty and quiet. Maybe someone lighting a candle. I find churches and what they’re supposed to represent very comforting.

[image error] Church of Christ Northern Hills Baptist (from northeast

Northern Hills Baptist (from northeast

Northern Hills Baptist church sign (from Ssouthwest)

[image error]

Grover Park Baptist Church

Northern Hills Baptist church sign (from Ssouthwest)

[image error]

Grover Park Baptist Church

Episcopal Church

Episcopal Church

Warrensburg Depot

Warrensburg Depot

March 22, 2021

A Friend’s House

My husband and I went for a drive yesterday and today because the weather has been so nice, spring is here, and the future looks a little rosier than it has in a year. We enjoy looking at churches so we tried to take a photo of every church in Warrensburg. Certainly, we missed some and hope to find them another day.

In my small hometown, which had a population of about 1800, there were at least seven churches. My young friends and I were all from different denominations but we thought of differences primarily in terms of who could do what–dance, wear jeans, listen to popular music, lead the singing, have instruments. A few of us used to play King of the Mountain on the wall of the old Nazarene church, which had burned down long before. We weren’t Nazarene, but the site seemed, if not holy, precious.

Once I told my mother how much I liked churches–that even being near them made me feel good. She said, “Of course. A friend lives there.”

First Presbyterian Church

[image error]

Northside Christian Church

First Presbyterian Church

[image error]

Northside Christian Church

Sign only for Northern Hills Baptist Church

[image error]

New Life United Pentecostal Church

Sign only for Northern Hills Baptist Church

[image error]

New Life United Pentecostal Church

Mormon Church

Mormon Church

Life Church of the Nazarene

Life Church of the Nazarene

Jesus Saves Pentecostal Church

[image error]

Historic Methodist Church

Jesus Saves Pentecostal Church

[image error]

Historic Methodist Church

First United Methodist Church

First United Methodist Church

First Christian Church

First Christian Church

First Baptist Church

First Baptist Church

Cumberland Presbyterian Church

[image error]

Community of Christ Church

Cumberland Presbyterian Church

[image error]

Community of Christ Church

Church of the Brethren

Church of the Brethren

Bethlehem Lutheran ChurchSome Churches in Warrensburg, Missouri

Bethlehem Lutheran ChurchSome Churches in Warrensburg, Missouri

March 14, 2021

Mixed Blog: End of One Pandemic Year at Home

For three months, I’ve been suffering from tendonitis, so writing of any kind has been painful and thus limited. A friend commented that Willa Cather (my most admired writer) had a similar ailment. That was interesting but not very comforting. I am no Willa Cather, and pain is pain. But my new book is out, beautiful, traveling through good promotion by University of Notre Dame Press, by word of mouth, a few wonderful reviews, and readings (see rmkinder.net). I wish it well and will love it into the future as best I can.

Given the tendonitis, I’ve made only brief and limited attempts at playing. I can now chord the piano to accompany singing some songs or backing up (slow versions of) standard hoedowns. This last week my husband and I managed 30 minutes on the dulcimer. We played “Amazing Grace,” “Fly Around My Pretty Little Miss,” “Bach’s Minuet,” “Cotton Eyed Joe,” “Cajun Waltz,” and a few others. Joy! Here’s my Sadie McSpadden, lovely girl.

It’s been a long, hard year for many people and in many ways. I’m grateful for the activities I love and can still enjoy. Looking forward to tomorrow and the day after, and after.

November 9, 2020

A Model for Bold Writing: Adam Johnson

The first story in Adam Johnson’s Fortune Smiles reminded me of the world he explores—the human situation, realistically, at its worst and at its best. I recalled specifically his novel The Orphan Master’s Son in which the horrors of North Korea’s totalitarian society were closely depicted. As a reader, I wanted to escape that regime, find happy endings for everyone, but stayed because of the truth being presented and because of a core thread, a love of and respect for humans and humanity. That love and respect pervades also Fortune Smiles. The collection would be a good study for writers who want to examine but not exploit sensitive and even ugly situations.

Johnson’s characters are in extreme circumstances, some of them off-putting, but certainly real: a man facing and dealing with the complete paralysis of his young wife; a man taking care of a young boy in the aftermath of the Katrina and Rita hurricanes in New Orleans; a woman dying of cancer in the midst of her young family; a man being introduced, by his victim, to his own part in the holocaust; a pedophile fighting his nature and fighting against those who share it; defectors who love their country. All these extremes are believable and understandable because multiple, specific details establish Johnson’s authority and his world’s reality: complex settings of intimate or foreign nature, modern technology in myriad uses, medicine, communication, punishment, crime.

Throughout, there’s little doubt what to admire, what at least to understand, what to fight and deplore. Even the most callous, seemingly unredeemable character, has a moment when, though the reader might not soften judgment a character does—not forgiving, but showing compassion to the compassionless. It is the high road we have learned to see better and appreciate in our time. We also see the circuitous, evasive reasoning that allows a person to hide from self and others.

In Johnson’s Fortune Smiles, we have the family defined as the family of man. It’s overtly stated in one story and implied by the collection. The problems rampant in our own culture and in the world are being suffered by humans—those we like and those we don’t; they’re part of our community.

Johnson’s stories aren’t for everyone. I wouldn’t recommend them to many of my reading friends who aren’t prepared to explore sad situations. Sometimes we want to be entertained, to have our hearts lifted, to laugh, and go into the world with a good feeling. There are many, many works that provide that vital warmth. But Johnson’s work looks deeply at suffering and how the spirit deals with it, rises above it, and that is also hopeful and warm. He has a great moral strength and reading his work bolsters that while also educating and increasing empathy in hard-to-understand situations, something our divided country needs more than ever.

November 5, 2020

Song About Missouri

September 8, 2020

Writing in the Ocean: Write, Read, Write

We learn something, good or bad, from every book we read—maybe what not to do. More often, there’s something to gain. My reading includes German comic books about Max and Brett, German folk tales—a dual language reader, because my German isn’t strong enough to read without help–some Spanish language novels, a slow go, too, though Spanish is more familiar to me, my having lived in Tucson. I also read about home remedies, poisons, superstitions, Biblical sources (e.g.,Harold Bloom’s the Book of J), the history of witchcraft, angels, animals, great tragedies, heroism. If I’m interested in a subject, I read about it. Toads. Salamanders.

But my consistent reading for pleasure and for learning is literature, stories and novels and essays by the best prose writers—not only the critically acclaimed but also those I stumble upon. Thus, it’s difficult for me to say at any given moment who is the best writer, who has influenced my writing. That depends on the genre, era, and my mood. I couldn’t complete a list if I had to begin with the most ancient text and come forward. Always among relatively recent favorites are Chekhov, William Faulkner, Willa Cather, Flannery O’Connor, Thomas Wolfe, Katherine Porter, Carson McCullers, Raymond Carver, and on and on. Right now I’m tense because of the hundreds of names I’m skipping. Per Petersen.

Because there are so many writers whose skills are greater than mine can ever be and because my experience personally is so limited—raised in a small town, low income, no travel until recent years—I am in awe of the field I work in—writing, in awe of what’s gone before and what’s current. That awareness can sometimes stop me. I sometimes put my writing away, or criticize it to the trash bin, or submit it without adequate introduction—a nice letter from a writer who loves words. My words and my confidence become heavy, I move with stones.

It’s possible that my writing, anyone’s writing, has a purpose, meets a need, whether or not the writing contributes to the grand art itself. Some people truly do write only for themselves, to satisfy a need for expression, to discover thoughts and patterns—many possible, good reasons. Sometimes we find journals and diaries that reveal a character and time and maybe a talent that we wish had been recognized earlier. Those are precious finds. They point to a truth about writing—you can’t be sure what effect your writing will have on the world. If you want to ensure that it’s never read, and serves only your own needs, then possibly you should burn whatever you’ve written. Heirs may print and distribute it or give it to a local historical society for posterity.

I’ve written earlier posts about how certain texts have changed my life. One has some bearing on how I feel about being so small in the ocean of writers. It was Bernard Malamud’s The Fixer. The novel is about a man wrongly imprisoned and tortured for years. I was moved by how fiercely the character defended his self-identify which was in effect his freedom. As long as he didn’t capitulate and confess to what was not true about him, he was free. A friend advised me that that concept had been presented many times, in greater works and stronger ways. Probably true. There’s always something better depending on what pool of knowledge surrounds you. But Malamud’s particular example of freedom came at the right time for me to appreciate it, maybe because it was the strongest element of the work, maybe because the nature of the torture was more horrific to me, or because of a myriad other reasons. A book can affect a reader in powerful ways because the reader is ready for the message. None of us can be certain of the effect our manuscripts may have on others. We can hope and strive toward a worthy goal—to have a good message, to offer understanding of the human situation, or hope in times of despair, or just a moment of pleasure, an instant of beauty. We might even dream, maybe subconsciously, of producing a masterpiece someday. Regardless our work will have some effect, possibly an important one, even if only to a small audience, maybe a single person.

Most recently I have been caught and stilled by the work of Annie Proulx, specifically Barkskins. The breadth and depth and beauty of the novel astonishes me. With historical accuracy and fictional power she’s covering the settling of Canada over generations, the great wealth offered by the country and native people and the gradual diminishing of both. She unfolds a panorama, vivid characters and scenes, cultures, customs, biases, wars, flora, fauna, illnesses, medicines, and in beautiful, clear, immediate prose. One needn’t grieve at the loss of a character, because he will surface again in the story of his sons or his sister or his enemy. Great achievements and great losses. Great writing. I love her and her talent.

And so it goes. I read, I write. I immerse myself in prose and ideas that enrich my world. Maybe I get stronger from resting a while and then I plunge on.

August 22, 2020

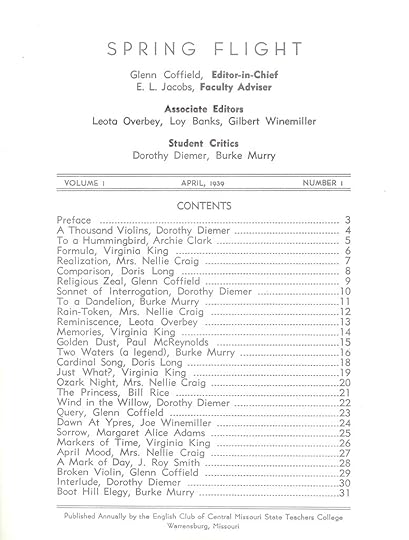

Spring Flight Poets

The writers and editors are aware that their art is not yet burnished to its ultimate perfection; they admit the presence of flaws in some facets of their handiwork; but they have had pleasure in writing and editing the poems, and they hope their friends will find pleasure in reading them.

This statement ends the preface to the first issue of Spring Flight, creative writing by members of the English Club of Central Missouri State Teachers College (now UCM), Warrensburg, Missouri in 1939. The contents page appears below. Copies of the first issue are probably scarce, but my copy is still in good shape. I’ll tag some or all of the names so relatives have a chance of finding them. I didn’t know any of the people though I recognize a name or two, from local buildings. The publication later became Cemost, then Pleiades.