R.M. Kinder's Blog, page 2

December 1, 2021

Our Cat Who Loved a Tree

We lost one of our cats last year, Twitch, a slow, easy-loving, fellow. We miss him, especially now, as Christmas approaches. Twitch loved our old Christmas tree. We tried a smaller one, but he didn’t accept it, just stared at it. I’m posting these pictures to show how he loved the one tree, even bit by bit as it came down. I know people over-sentimentalize pets (and maybe all animals). Guilty. But the creatures bring that about if you pay attention to them. Not all, of course. Some of them prefer no attention.

November 10, 2021

About Anne Tyler’s Redhead by the Side of the Road

Here’s a book to warm the heart. Every character is flawed but within likeable parameters and Tyler’s acceptance and fondness embraces large variations of personalities. The best is Micah Mortimer, the lead character. Following him is like accompanying a dear fellow and bolstering him, rooting for him to open his eyes. It is so refreshing to have problems presented that aren’t dark, dead end, don’t require superhuman fortitude, but just honesty, perseverance, self-examination, gradually at least, an open mind and heart. And yet, the conflicts are serious, as timely now as in the past—the need for a family, the desire to know who your parents were, to find your own path, to be different and accepted, to love and be loved.

Central is that Micah Mortimer loses lovers and doesn’t know why. He wonders what’s his flaw, and is in search of the answer. One wonders why, too. He seems to be the kindest, sweetest guy, deserving of better working positions than computer troubleshooter and apartment manager. Then, as it occurs in real life, we come to know him and realize, Ah, yes. Micah is a perfectionist, obsessive compulsive, whose sweet nature is combined with micro-management. He has a definite, wonderful urge to be kind, to help others, but that loving trait is accompanied by a too sharp eye for small faults, and a too rigid schedule for comfort.

Tyler’s explanation for Micah’s nature is really a careful, believable blend of nature and nurture. We see him interact with customers, with neighbors, with former lovers, and with his family. Contrasting Micah’s nature is his boisterous, chaotic, creative family who reveal his uniqueness. He loves them dearly just as they are but wants and needs order and quiet. They accept him, too, and his need for control. This need may have been innate, but made more solid perhaps by the environment—his family. So, Micah comes across as a normal person, somewhere on the spectrum of human, who needs to pare down his control a bit.

A personality quirk that weakens the romantic element is Micah’s apparent capability of loving any decent woman, moving from one to the next with a similar level of hope and emotion. Perhaps that makes the work even more realistic. We can, after all, love many people and not all grand passions are healthy ones. Tyler’s ways of showing love in the perception of another is very touching. I’m tempted to say it’s also the feminine approach. Micah notes the tiny details of a person that please him, just the sight or sound. It’s the way we all react surely to something we love, the grace of it, the feeling it brings to us. Tyler captures that beautifully.

One slightly strange plot line is that a young man appears who believes Micah is his father from a limited liaison with his mother. Micah knows it isn’t true—and the reader knows—but Micah doesn’t totally disillusion the needy young man. Instead, he assumes a helping role, rather fatherly. That’s an act many kind people do, sometimes for a community of children.

In the world of this novel, we don’t lose people. Lives intersect and intersect later in a new way. Things change but not drastically and horribly. Tyler’s work suggests we may have a chance to understand, to explain, to regain relationships and broaden our sense of self.

Each time I read a Tyler book, I recall how much I enjoy her novels, her characters, her respect for them and people in general. I’m always fortified by her view on life. (Mary Oliver’s poetry does that for me, too. Sees the beauty in the small and the whole). I want to write books like this. A wonderful group of normal people, all important and lovable, and nothing false or overwrought, nothing dire and dark, subtle, gentle, and moderate in today’s world. We write what we know and write toward what we wish to know and believe.

August 13, 2021

From a Good Heart and a Great Pen: Honeyman’s Eleanor Oliphant

Even though this book has been out for four years and reviewed many times (I’ve read none of them), it’s new to me, and I want to sing its praises. It does have a few flaws, but they are minor in contrast with its virtues. There’s a very dark element—something horrendous has happened—that will thread throughout, be clearly exposed and understood, but it’s balanced and actually overwhelmed by quirky characters, good people, and good warm messages. While entertaining from beginning to end, it fosters understanding of how very different we are in our interpretation of what’s normal, standard, and even what’s happening at a given moment. And it illustrates that being open to experience and interacting with others may be awkward and painful, but it’s the road to knowing who you are.

Eleanor Oliphant (not her real name) is Scottish, works as an accountant in the back office of a company. She has four immediate coworkers, but others interact occasionally. Eleanor is disfigured with a scarred face, and the cause of the disfigurement haunts her in brief memories. Her upbringing has prepared her for a certain kind of “normal” and a certain place in the world. From her point of view what she does is the proper way, but to those around her, she is perhaps “right nutty.” She has lived in the same apartment for about 10 years, with no visitors, no social life. She has frequent conversations with her verbally vicious mother, and weekend visits with a bottle of vodka. Though isolated, she knows of popular culture and trends, though only generally, beauty shops, bikini waxes. Recently, she has set her heart on musician Johnnie Lomond, whom she hasn’t met, as the man who will be her life partner—her savior. While she’s trying to reinvent herself to capture his interest, she’s being courted by a kind of oversized nice guy coworker, Raymond, from IT.

Eleanor is a very quirky character, and very winning. Articulate, intelligent, judgmental, occasionally biting, she can switch dialects and verbal domains (talk high society or low, British or Scots), and seems familiar with philosophy, literature, French—enough for light social discourse. One wonders how she came by this training. And one learns. Her innocent anticipation about such matters as bikini waxes, hair styling, and especially about food are humorous and possibly match many of our own awkward introductions into a culture, sub or main.

At times realism is stretched. At the beginning, Eleanor’s physical disfigurement appears to be a major disfigurement, not so later on, manageable with makeup. Some of Eleanor’s insight and consequent changes occur too swiftly. They outstep development, especially for a person as rigorously locked in a pattern as she seems to be. The quickness, though, keeps the story lively, and unpredictable. And there’s the possibility that she changes quickly because her core nature, under training and experience, is ready to burst out with the first opportunity and sense of safe landing.

The mystery of what happened to Eleanor—and her role in it–unwinds a little at a time and is never the real draw, just one part. That’s refreshing, letting the reader know or at least suspect that this isn’t going to be a graphic horror. Horror, yes, in the sense of what happens to people in life, but not scene to scene depicted. In fact, it’s a kind of gentle mystery, not a cozy, but like a British mystery where the crime is vile, but the people are the reward of the book, quirky, but basically good. The mystery is honestly answered. There’s no surprise, and a reader accustomed to mysteries will likely identify the clues—not be able to project totally, but to feel on a good track, and at the end say Aha!

The language is particularly appealing. Some passages are so perfect to that character and her world, and yet, one may want to adopt them. Eleanor explains that when she wants to know something, she relies on the animal world, and might ask herself “What would a salamander do?” If we consider that a bit deeply, she’s saying she has to rely on what she knows. Which is what she does. Perhaps we all do. Here are a few examples from many that are immediately touching. Describing herself: “I am matte dull and scuffed.” Upon seeing a crying baby finally being comforted: “My heart soared for him.” And at a certain moment: “Silence sat between us, shivering with misery.” Such lines at the right time are so valuable to readers, at least this one. I like to feel the story as well as to read and know it.

This was Gail Honeyman’s first book. I look forward to any writing from her good heart and great pen.

Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine: a Novel

Penquin 2017, 2018

Available on Amazon and everywhere else

August 8, 2021

Raccoon and I: Two Poor Decisions

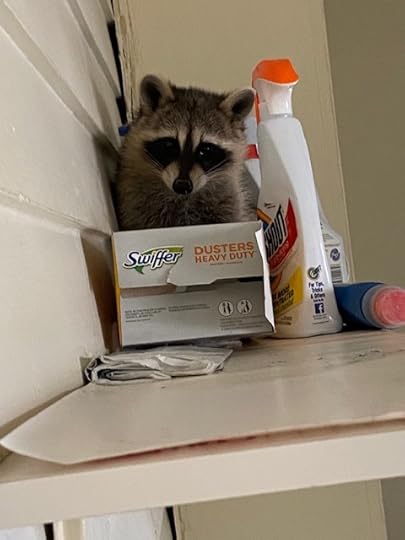

What I assumed was a wool feather duster had a strange appearance. Instead of lying horizontally on the laundry room shelf, half of it hung down, very soiled. The dirty areas were layered, ringed, actually, and that clued me to look closer. Behind the soapnuts bag, the softening sheets, and mopping pads was a scrunched down raccoon. I thought he had to be a baby, because he could hide in such limited space. I spoke to him a few times and he raised up to study me. I said a few more words, softly, since he wasn’t erratic or threatening or even cowering. Then I worried that his calmness might not be natural. He might be rabid. So, what now?

It was too early for an Animal Control officer to be on duty, and I wasn’t certain we even had such an officer in our town. During the pandemic, the animal shelter was taken over by volunteers and funded privately. Now a tax supports it. A call to the police department might result in the animal being put down. I wasn’t ready to be responsible for that. The raccoon had seemed friendly, perhaps a little accustomed to humans. I found two live-catch cages in our backyard shed, but couldn’t reach the biggest one, so settled for the smallest—large enough for a cat and thus suitable for a little raccoon. I set the trap with a bit of peanut butter in the rear, and put it in the floor of the laundry room. That’s a narrow space, with washer and dryer—and shelf above—on one side, and a long closet on the other. The raccoon would have the option of going out the cat window by which he entered, or onto the floor and into the cage. Or he could stay on the shelf for a long period since three bowls of food were on the dryer below him. A bathroom on one end offered water, especially for a crafty raccoon. Leaving the door to the laundry room open wasn’t an option, since we have two dogs and two cats. Mayhem at least, and death at worst, might result.

I taped the cat-door flap up, so a window to the outside was clearly visible and the scents of outside could waft in. I called to the raccoon from the outside window and waved with my hand. Here’s the way, fellow. Baby. He didn’t budge. He looked like he might sleep there.

After 8:00 a.m. I called the Police Department’s non-emergency number. They were unable to send an officer since they offered on-hands assistance only for domesticated animal problems. But they connected me with Samuel Whisler at the Missouri Department of Conservation. A gentle-voiced man, he was on the side of the raccoon (as was I). He advised me that raccoons are very seldom rabid and that I just needed make a clear path to outside and to make the raccoon’s inside position uncomfortable. I needed something long to prod him with from a distance, something like a shovel. No way could I lift and maneuver a shovel without hurting something, mostly myself. Mr. Whisler stayed on the phone for my first try—a timid push with a long-handled brush stuck into a Swiffer box. I wielded it with one hand, phone in the other. The raccoon looked perplexed, not afraid or nervous. Questioning. I hung up the phone. I felt guilty.

Talking constantly, I used a kitchen broom to push the box toward the raccoon. Now he was being dislodged, and he went into a slow-motion action. He was really a laid-back raccoon. He somberly nudged or pushed everything off the shelf, including the iron. He turned his back to me and tried to climb the cupboards or to pull them from the wall as if opening a door that way. He repeatedly looked back at me. He wet suddenly, so much that liquid ran the length of the shelf, dripping over the sides and over the end. I didn’t blame him. But. I withdrew, closed the kitchen door, and hoped his panic would guide him out the window or into the trap.

From the kitchen, I heard a thump on metal. He was down from the shelf, onto the washer or dryer. I ran out the kitchen door to the deck in time to see him going over the side, behind the tree and on up to his escape.

Even then, I knew I was enjoying the encounter, because he was never a threat. Some raccoons might be, particularly if ill, as might be any cornered animal. This one was doing the best he could. He may have hissed at me once, but if he did, I forgive him. I reported the result to Samuel Whisler, with my thanks. He advised me that the real danger here was to the raccoon–leaving cat food out could lead to the raccoon’s death. Cats carry distemper, though they don’t get the disease, don’t suffer from it. They do transmit it. And raccoons die from distemper. It’s a real problem, he said.

Cleaning the laundry was a hassle. The handprints are still on the wall. I can’t get a good photo of them, but I remember how his hands looked as he patted and gripped. I didn’t know jumping from the shelf to the dryer was so difficult. He wanted to climb or hang down, not jump. He eventually made a bold move.

Now, I take up the cats’ food at night. They’ll learn to wait for breakfast and to hurry for a late night snack before it disappears. I would very much like to leave something outside for the raccoon, but I know that would be more meeting a need of mine that of meeting his. I wish I had been less concerned with allowing him to escape and more with allowing him to live a good life. If I had held out longer, he would have gone into the cage. I could have taken him to Cave Hollow Park or Knob Noster Park where food would be abundant, and he wouldn’t have to eat cat food, or go inside houses, or find trash cans. My impatience was stronger than my foresight.

July 28, 2021

Short Response to Lightning Flowers by Katherine E. Standefer

An inspiring and uplifting book for anyone facing—or loving someone who faces—a life-changing and life-threatening crisis. The first part of this memoir is a very personal account of the onset of a devastating, life-changing health condition. The narrator is a strong, hopeful person who gradually accepts the new reality of her life. The prose style is lovely—authentic, clear, emotional, passionate, and yet objective enough to avoid too much sympathy. That objectivity prepares the reader for a shift into the second part of the memoir, research about the treatment for the condition, and into all aspects of that treatment. The boldness of the author in meeting her challenges reveals a strength of character that is totally believable, supported by the depth of details and research, and very admirable. She loves life and has values she doesn’t relinquish. Her story heartens the spirit. I recommend it highly.

Little, Brown, Spark 2020

Available through Amazon

July 20, 2021

Patricia Lawson’s Short Fiction

Patricia Lawson’s Odd Ducks is a very charming book, gentle despite some dark edges. The nine stories are set in Kansas City suburban communities from the sixties through the eighties and focused on common conflicts among neighbors and families. The characters are familiar and non-threatening, librarians, teachers, salesmen, children, artists; they are Catholic, Jewish, agnostic, gay—a mixed group as today in most cities. There’s no graphic violence, and very little sexuality and crudity, just enough that the stories are for adults, not children. Children are, though, a highlight of this work—the wonder of their imagination, especially. Creativity is itself a major focus. One teacher tells her students a project is a “homage to creativity” and this small book seems to be that also.

Humor is a big draw throughout, though the stories aren’t actually funny. The situations invite humor and the characters’ thoughts and dialog are often colorful and surprising. This is particularly true when children are central actors. A teacher’s advice to “Think like an artist,” brings a chuckle, but a fourth grader’s artistic creation Butterfly Man eventually brings a chill. The opening piece prepares readers for these unexpected shifts. In” Dead Ducks” (the title is a clue), a fellow who likes to work hefty crossword puzzles shaves his neighbor’s dog (does a bad job), is befriended by the neighbor, a beer-guzzling, rough-talking womanizer, and has to go duck hunting with him. The anticipated hunt is off-text. The nice guy returns with a duck mangled like a cartoon rubber duck and with his own expression and bearing skewed by the ugly experience he actually had–and that earlier details foretold.

Lawson explores serious topics but in a fresh and multi-view manner: fidelity, animal hoarding, community rules, teaching children, proper literature, media influence, cartoon violence, outcasts, bigotry. One of the funniest and thematically strong stories is “Her Religious Advisors” in which college student Carol must write an argumentative essay on her religious beliefs. The sources she recalls in preparation are disparate, creative and dramatic. One teacher had enacted Bible stories and added vivid details. Another made fictional and historical characters part of her daily life, and of Carol’s lessons. Later, Carol, willing to please but honest to the bone, can’t write the argument because all the stories inside her are part of her truth. She reasons if non-Bible stories are not equal to Bible stories, they are at least “right next door.” In Lawson’s world, most people are creative in answering life’s questions. They draw on whatever source is available and interpret with their own experiences. That experience includes what they’ve read, been told, seen, or felt.

People seem unable really to change. They can change direction and place, and aspire to a better personality or nature, and they can acquire graces, but the cold ones remain cold, the sympathetic and loving, still so. It’s a fair take of people, suggesting they would do better if they could. Perhaps they have had hard lessons.

That dark vein in the collection is powerful, though. It’s heightened by a strange laugh at a moment of insight and isolation. The laugh occurs overtly and dramatically in at least three stories, “My Religious Advisors,” “Adventures in Learning,” and “Miss Mauve and Miss Green.” In the first, a “husky laugh” seems to be coming from outside the room where a friend lies dying and Carol rushes to the corridor only to find it empty. In the second, Elise, 11, hears a “sort of chuckling sound” that seems to come from downstream. She hears it just as she’s privy to the compassion and pain of a girl near Elise’s age, a girl she wants to comfort but can’t. In the third, Miss Green wonders what the young artists are doing in the bathroom and “it seemed she could hear a long, low chuckle escaping from within.” This occurs just after she discovers a secret addition to the young men’s artwork. In each case, loneliness and powerlessness fill the present moment. Is this what awaits everyone? Learning that something is missing that others know? Is it the laughter of something bigger than the characters? Is it the raw, unknown part of life, and whoever controls that unknown is what laughs? Maybe humor always has that dark side to someone. Here it isn’t pleasant, in any case.

Odd Ducks is a particularly good read now when differences among us have become so indicative of a greater divide that we risk losing touch of our commonalities. These stories deal with bias and false judgment and questionable values but through a kind, understanding view. People are a long time forming and when adult, they bring with them realities that differ. This collection offers some insight into the making of us, into individuality, and the intensity of human longing to be true to self and to be accepted by and part of the community.

Odd Ducks. BkMk Press 2020, 202 pages.

June 28, 2021

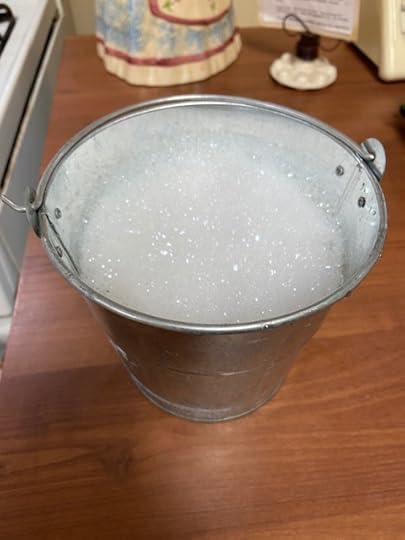

Elderberry, Beetles, Reading and Writing

This is a blooming elderberry bush, also known as elder plant, and is similar in size and blossoms to the parent of the three small elderberry bushes in my yard. Mine bloomed only this year, the lovely floating blossoms creating that “pagoda-like” image in My Antonia. I had planned to make “elderberry” punch, using just blossoms, water, and sugar. Elderberry wine, “elder blow wine” would also be possible, though I’m not that ambitious. Having the plants, seeing the blossoms, and drinking the punch were just a small goal rising from my fondness for Willa Cather’s work (and values) and for some community customs.

But. Japanese beetles have struck. Last year, they decimated the rose bush and they filigreed every leaf on the plum tree. The rose bush looks like a curse blackened it. The plum tree is gone, but not because of the beetles. They don’t kill plants, they only mate on the blossoms and consume them. The plum tree died from age and too many ice storms and broken limbs. Its last year, though, was not pretty. I don’t have photos of that. I didn’t know beetles would devour the leaves. I had eyes on the rose.

A few blossoms remain on my elderberries, but inroads have been made and I seriously doubt that any will survive. Even if they do, I won’t want to make punch from them. Maybe when the beetles finish their own natural seasonal rush, more blossoms will appear and I can have a late summer purer elderberry punch.

The problem with fighting the beetles is much like other battles on a grander scale. Complicated. The sure way of decimating the beetle population (an ugly thought in itself) poses danger to other life. The one supposed “safe” insecticide will harm bees. We hadn’t seen bees on our property for two years and this year they appeared, probably because of the elderberry blossoms. I spotted only three. I think letting them coexist with the beetles as long as the blossoms last is better than killing one bee. It’s not really a tough decision.

It’s possible to fight the beetles by personally drowning them. Even a gentle swipe will dislodge a group of them into a waiting pail of soapy water. That method seems in the right spirit given my inspiration and my goal. That or conceding.

June 21, 2021

John Mort’s Down Along the Piney: Finding the Dream

Rarely have I enjoyed a collection of short stories as I have John Mort’s Down Along the Piney: Ozarks Stories. The details are so specific and sharp that Mort almost lays a map as the characters move through their lives, which are sometimes not along the Piney. The reader is privy through him to the Missouri Ozarks, towns, churches, denominations, stores, food, drink, songs, language, and, of course, people. Shining in all the stories is Mort’s fondness for that country and those people, even as he presents some truly ugly behavior and painful losses. The reader can count on understanding what the real conflict is—what’s at stake at the heart level—on understanding and caring for the characters, and, at the end, both knowing and feeling the resolution. His stories blossom. The ending one expects isn’t what occurs but is earned and right.

Sometimes that sudden complete insight is enough to bring a gasp, as in one of my favorite stories, “Blackberries.” It’s a very short piece that demonstrates the dream, the disillusionment, and also Mort’s mastery of small details. Here, a teenaged boy has been caring for his mother who is dying of cancer. He has such hope that all the effort will keep her alive. It must. With snippets of dialog, brief movements and the boy’s thoughts, the complex relationship among four people unfolds. Only at the end does the boy’s full understanding become clear as he makes his own call for reality. His need is wrenching. The epiphany is not for the character, but for the reader.

This acknowledgement of and respect for the individual dream is the aspect of John Mort’s Down Along the Piney that is most touching and most memorable. The reality of it appears in every story, not necessarily as the conflict but as a human trait, differing with the individual, and built from personal need and from a concept of the ideal. For some it’s a guiding principle, a calling, a place, an achievement. In the first story, it’s a search that utilizes a man’s skills and continues his image of his best self; in “Mission to Mars,” Brad Naylor longs to have been part of space exploration or some great endeavor and settles for a sliver of his dream; Thomas Hovey hears a great voice from a railcar and must obey, to “find a church, bring the gospel, and help the poor.” The dreams are as natural as breathing and can be as flawed as the human creator. The best life is the simple one, food, shelter, work, love, but that is, in the Ozarks, more and more impossible, and comes more by chance than effort. One man wins the lottery and gives a lot of money away as he drives deeper into the country and revives a dying town. That is perhaps the ideal dream come to fruition, providing the wherewithal for happiness to a dying region.

An especially moving account of the individual dream is that of Birdy Blevins. He’s a totally believable character, one that raises hackles and concerns too. He’s not a fully functioning young man though the exact problem isn’t clear. Severe abuse and isolation have certainly damaged him, as has extensive drug use, and perhaps genetics, too. He’s the “best marksman in New Jerusalem” and guns are natural to him. Birdy wants a principle to live by and finds it: “thou shalt not kill.” But his fervor to please is manipulated to serve someone else’s principle. Birdy wants to do something noble. What happens is the result of zeal and strength and lack of understanding set loose, armed, and pointed. His dream was to do good, to sacrifice. He is frightening and sad. He is perhaps too true a representation of some zealots acting today, or longing to act.

Women in Mort’s world are a mystery. They can be as, or more, ambitious, talented and driven as a man, but they are the unknown. Their allure is more than physical, though even a nice walk or shapely leg can be enough to invite a pursuit. Mort seems in awe of, in love with, drawn to, and cautious about women. He’s comfortable with men and sees their sexuality as more a physical need, strong and almost irresistible, but an obstacle to clearer and perhaps higher passions. Throughout, early marriages are the first step toward disaster. In “Book Club,” a woman has been released on parole from prison, though her crime isn’t clear. She seems a victim immediately because she’s given old clothes, a scant bit of money, and no way to get anywhere. It’s like a dismissal from the world or from the tribe. She is taken in by women who have an organized life around the reading of old books, but who are somehow more like the community in Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery. The situation is elusive, though many interpretations are possible, among them that the façade of women’s book clubs disguises some cold and dangerous natures.

John Mort has published several books, including three collections of short fiction. This fourth collection won the 2018 Richard Sullivan Short Fiction Award, and has already won great praise. It is a warm and engaging book about real people, hodgepodge humanity, the people drawing us in with their hope and hurt. Down Along the Piney: Ozarks Stories highlights the depth of Mort’s understanding of human nature. Reading it is like travelling through a region of one’s own home ground with an intelligent, gentle guide, a person who is intimately familiar with all of it and honest about it. A worthy and telling journey.

Down Along the Piney

University of Notre Dame Press

September 30, 2018

0268104050

Available on Amazon

May 21, 2021

Flourishing

I’m very sentimental, and I like to mark special occasions with some memento or ritual. When my first book was released, I bought three ballpoint pens that I planned to sign books with. The pens looked a little romantic (now I think Gothic), and they were a bit heavy, hefty. They seemed perfect and I planned to keep them my entire career. By that, I meant life, because I intended for my career to last as long as my life.

The pens weren’t really easy to write with. The ink tube didn’t emerge far enough and was more round than pointed, so the pen dragged rather than glided and the letters were somewhat thick and blurry. Since the years from first publication to the next were many, the pens became less a reminder of something grand and more a reminder of a failing—of heart and success. Single short story publications are themselves a gift, and a great boost to the spirit, but not the momentous event of a book publication. For sure, short stories don’t usually prompt anyone to ask for a signature. The romantic pens were eventually misplaced in my very realistic life.

The next book publication happened sixteen years later. The ink in the ritual pens had caked, the nibs had retreated even further. I didn’t plan to use them, bulky as they were, and not particularly good omens, given the lengthy wait. I bought a new pen. That was at the Southeast Missouri State University bookstore, just an hour or so before a reading. The pen had the university’s emblem on it, was red, slender and modern, and produced a medium script. I planned to use it from then on. I lost it. I went back to fountain pens which I had used during my years in college, especially graduate school. The new fountain pens, though, held cartridges, which invariably leaked. I didn’t care.

This year my fifth book of fiction was published, thirty years after the first. And here are my three pens. They have new inserts, which still don’t emerge much. The movement is still draggy and the script too full. But I adore them, especially recalling how I felt with that first urge to buy them, the glow of hope and commitment. At a reading a few years ago, a gentleman asked me if I would sign his book “with a flourish.” I understood the request, and I tried to comply. I was using a ballpoint pen then, well capable of that particular extra flair, but I didn’t manage it very well. Since then, I’ve practiced and can naturally sign my name with a forceful and somewhat graceful flourish. Actually, it’s just a quick line backward and forward above my name, sometimes with a slight trailing upward curve. I plan to practice that signature with the old pens. I want especially to be able to do that, no matter which one I pick up, or for which book. I know the flourish will have a distinct air not possible with all the other fly-by-nights. I am so very grateful for being able to write, to enjoy it so, and to have had any success at all. These pens are not boon companions—they’re inanimate, after all—but they have still accompanied me and I want to keep them involved until the end of, you know, end.

May 11, 2021

An Affinity for Kindness

In a pre-interview conversation, the host asked if I felt an affinity with George Saunders’ fiction since two pieces in my latest collection, “Alvie and the Rapist” and “Mother Post,” stretch the bounds of realism. At the time, I hadn’t read George Saunders’ work but I recalled that one of his stories appeared in a recent New Yorker. (I habitually stack the issues up and read them as I can find time.) I immediately read “Ghoul,” ordered Pastoralia, and read the title story. They were a new kind of story to me, dire and funny, too—beautifully absurd seemed the right description. That limited sampling humbled and informed me that I have no affinity with Saunders’ fiction in the sense the host intended, which was the reach into the surreal. Saunders’ settings in “Ghoul” and “Pastoralia” are futuristic, an extrapolation of now, where we’re headed if we don’t stop our skidding values. “Alive and the Rapist” and “Mother Post,” on the other hand, are very now, and what appears to be fantasy is just an aspect of our present mentality and action.

In both “Ghoul” and “Pastoralia” readers encounter a fractured human society where life is a simulation, a huge theme park. The individual has a role and groups are parceled into entertaining small stages like living museums or reality shows. The stages and actors are the visual part of the world, the consumers of necessities, such as food and drink and shelter. The power behind them, whatever provides sustenance and codes and protection, is behind the scenes. In “Ghoul” life is underground, offering among other shows the Wild West, Victorian Weekend, and The Maws of Hell. Resident actors wait for the never arriving guests and one occasionally discovers there is no entrance and no exit. In “Pastoralia,” the enactments are above ground, in a large area of hills and valley, offering living exhibits, such as a normal day in the life of a Neanderthal couple. The humans in both these societies are required to follow restrictive rules that disallow individuality and personal codes, deny love, friendship, variety, trust, and especially choice. They must report any nonconformity and if they don’t, that will be reported and punished. I was glad to encounter characters who protest, sometimes mildly, such as being hesitant to kick a downed fellow or refusing to report a violation, and sometimes only in self-defense. But there’s always a desire and an effort for better behavior and to fulfill higher needs. A character will risk a bit of truth, will warn another person. He may fail and conform, as in “Pastoralia,” but chances are he’s only biding his time.

In both “Alvie and the Rapist” and “Mother Post” the fantastical elements are in the minds of the characters. Alvie has an aberrant mind. She interprets events in an unusual way, mixing her beliefs—or understandings, or references—about God and Christ into her experiences. She can’t report what happens to her in a fashion easily understood by another person. Her potential rapist also has a fantasy life that identifies his victim and himself in particular, strange roles. The psychiatrist, trying to interpret Alvie’s belief that God is out to get her, to impregnate her, can’t know what’s happening. So the story isn’t fantasy. It’s realistic, reporting and exploring mindsets, not the times, but the people. The seemingly unreal details in “Mother Post” are the kind of conjecture that arises in a community and becomes rumor facts, eventually history, though not true. The narrator is a collective sensibility and voice. It reports what people are saying and fearing, and what they may be doing. Do post mailboxes actually just pop up out of the earth overnight? Does someone actually put roadkill on a car or mail a bit of personal something to another person? Did a group of local women actually emasculate a man years ago? That’s what people said, so it’s realism in the story, in their time, not fantasy.

While my fictional world is not Saunders’, there are some similarities, among them the uncertainty of what’s true, the ever presence of threat, the power of conjecture, and the longing for trust, safety, and love. Saunders’ stories urge us to maintain the better human traits, kindness and understanding, and to be brave. If a code requires less of us, we must resist. I hope my stories do the same. He also manages the sane touch of humor. I aspire to more of that.

Now, having addressed the question of my two stories by a limited comparison to two stories by Saunders, I’ve ordered Saunders’ Congratulations, by the way: Some Thoughts on Kindness and Tenth of December. I’m certain that hope and compassion are central, even if it’s the loss of them.

“Ghoul.” New Yorker, April, 2021: 50-64.

“Pastoralia.” Pastoralia. New York: Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 8-57, 2000. Kindle. https://www.penguin.com/publishers/riverhead.