Kelly Jensen's Blog, page 89

March 25, 2015

On Being a Feminist YA Author and Daring to Write “Unlikable”: Guest Post by Amy Reed

Today's guest post for the "About the Girls" series comes to us from Amy Reed. She's talking about writing those "unlikable" girls and why she does it.

Amy Reed is the author of the gritty, contemporary YA novels BEAUTIFUL, CLEAN, CRAZY, OVER YOU, and DAMAGED. Her new book, INVINCIBLE, the first in a two-book series, releases April 28th. Find out more at www.amyreedfiction.com.

Something I see a lot in reviews of YA fiction (including my own books) is the complaint that a main character isn’t “likeable.” A book can be written beautifully and have a compelling plot, but if the protagonist isn’t likeable, it’s as if the rest of the book’s great qualities don’t matter. It’s as if the book isn’t worthy of being read if the main character doesn’t meet a certain list of qualities that a perfect girl should have. I don’t know if I’ve ever seen this complaint in a review of an adult literary novel written by a man. In fact, some of the most celebrated books in the straight white male literary cannon—Infinite Jest, A Confederacy of Dunces, The Catcher in the Rye, anything by Jonathan Franzen-- are full of main characters who are detestable. Lolita is about a pedophile. Crime and Punishment is about a murderer. No one says these books suck because the main character is unlikeable. These books, these characters, are judged by a different set of criteria.

So who are these girls we’re supposed to be writing? Are they girls we think our readers would want to be friends with? Are they girls we think boys want to date? I think about some of the best-selling YA books I’ve read over the years, and there is definitely a standard “type” in many of them. These girls are white and of average height. They are thin, but not too thin. They are smart, but not too smart. They are a little bit shy, but not disastrously so. They are mostly nice, and when they are not nice, they feel bad about it. They make mistakes, but recognize them quickly. They want to be good. They fall deeply and madly in love with a boy, and that love defines them. The conflicts in their lives tend to be external rather than resulting from their own character flaws. Theirs are the stories of good girls fighting against a world that wants to corrupt good girls.

But what about the rest of us? I imagine myself as a teenager and reading these characters. I imagine myself throwing these books across the room. Not because they are not good books, but because I did not see myself in their pages. I was not the good girl they described. I was a girl who did bad things and did not always feel bad about them. I was a girl who struggled with addiction and mental illness. I starved myself skinny and I ate myself borderline obese. I loved both boys and girls, but my relationships were rarely about love. My friendships were deep and passionate and far more meaningful than any romance. I was a leader, a loner, and sometimes a follower. I was a mean girl and I was bullied. I was too smart and too entitled. I was a bitch and I was a victim. I was obnoxious and righteous, and I was pathologically shy and insecure. I was a million different kinds of girls. And they were all valid.

These are the girls I know. These are the girls I write. They are sometimes unlikable, but they are always worthy of love. They are worthy of having their stories told.

I am a feminist YA author. I want a feminist YA. I want a YA where all girls see themselves represented, where all girls see hope and truth, struggle and redemption. I want them to find home inside the pages. I want them to find both escape and gritty reality. I want them to see their mistakes being made, their feelings being felt, and their problems being resolved. I want them to know it is okay that they exist. I want them to know their existence is worthy of being written about.

If we are to have a feminist YA, we must write about all the girls, not just the ones that are “likeable”. Because “likeable” is just another way of prescribing a right way to be a girl. Because girls and women are complicated and deep and layered and messy and infinitely fascinating. Because if male characters are allowed to be those things and still be worthy of reading, so should female characters. Because I don’t want to read just one kind of woman. Because I don’t want to be one kind of woman. Because if we do not give our female characters the right to be all kinds of women, how do we expect our readers to know they have that right, too?

***

Invincible will be available April 28.

Related StoriesWhy Friendship Books Are Essential: Guest Post by Stacey LeeStrong Heroines: Guest Post by Mary E. PearsonAppropriate Literature: Guest Post by Elana K. Arnold

Related StoriesWhy Friendship Books Are Essential: Guest Post by Stacey LeeStrong Heroines: Guest Post by Mary E. PearsonAppropriate Literature: Guest Post by Elana K. Arnold

Published on March 25, 2015 22:00

March 24, 2015

Why Friendship Books Are Essential: Guest Post by Stacey Lee

Today's guest post comes from debut YA author Stacey Lee. She's talking about the importance of friendship books and why girls need these stories, be they about girl-to-girl friendships or not.

Stacey Lee is a fourth generation Chinese-American whose people came to California during the heydays of the cowboys. She believes she still has a bit of cowboy dust in her soul. A native of southern California, she graduated from UCLA then got her law degree at UC Davis King Hall. After practicing law in the Silicon Valley for several years, she finally took up the pen because she wanted the perks of being able to nap during the day, and it was easier than moving to Spain. She plays classical piano, wrangles children, and writes YA fiction.

Stacey Lee is a fourth generation Chinese-American whose people came to California during the heydays of the cowboys. She believes she still has a bit of cowboy dust in her soul. A native of southern California, she graduated from UCLA then got her law degree at UC Davis King Hall. After practicing law in the Silicon Valley for several years, she finally took up the pen because she wanted the perks of being able to nap during the day, and it was easier than moving to Spain. She plays classical piano, wrangles children, and writes YA fiction.UNDER A PAINTED SKY is her debut book.

Tastes change. At two years old, my daughter couldn’t get enough of Everyone Poops, but by age three, she had discarded that one for The Holes In Your Nose. After sticking her fingers up her nose got old, she moved to If You Give a Mouse a Cookie (which might explain her insatiable need for cookies), and so on and so forth.

Somewhere along the way, she’s become a tween, and now she can’t get enough of friendship stories. But even as she evolves into wanting the more ‘lovey dovey’ books, I hope the friendship story is one she will never outgrow.

So why are friendship books so important?

First, let’s look at why friendships are so important. Studies show that the strongest predictor of having a fulfilling life is to build healthy relationships with others, especially for women. One landmark study showed that women respond to stress with a cascade of brain chemicals that cause them to befriend other women. Up until then, it was thought that stress provoked a fight or flight response, but that was due to the test subjects historically consisting of men. This ‘befriending’ response buffers stress for women in a way that doesn’t occur in men. Another study found that the more friends women have, the less likely they are to develop physical impairments as they age. Friendships are as essential to women as a good diet and exercise.

1. Friendship stories encourage us to seek out good friendships.

Books that show healthy friendships encourage us to foster these relationships in our lives. How many of us wanted an amazing spider for a best friend after reading Charlotte’s Web? Someone who would save our hides from becoming bacon when the world turned against us? E.B. White created such relatable emotions in her two unlikely characters of Wilbur the pig and Charlotte the spider, it’s not surprising this book is the best selling paperback of all time. The ending still chokes me up.

Another classic series, the Betsy-Tacy-Tib books by Maud Hart Lovelace, centers around three best friends who are constantly getting into trouble for things like throwing mud at each other, and cutting off each other’s hair. When I read them, I longed for a friend I could throw mud at. (Instead, I had sisters, who were almost as fun.) To this day, I still seek out the kind of people I can be silly with, because of those girls.

2. Friendship stories help us to be good friends.

My daughter loves the Gallagher Girl series by Ally Carter, about an elite spy school for teen girls. When I asked her what she likes most about the books, it wasn’t the gadgets or the girls’ crazy adventures. Instead, she loves how the girls rely on each other in tough situations, whatever that involves – boys, parents, ancient international terrorist organizations. I felt a moment of pride when she told me, “When I read (these books), they help me be a good friend.”

Returning to Charlotte’s Web, while I wanted a spider for a best friend, more often I imagined that I could be that selfless spider someday. Books help us imagine ourselves at our best, and if we can imagine it, we can achieve it.

3. Books that show unhealthy friendship help us understand others and ourselves.

Alexis Bass’ brilliant novel Love and Other Theories is about a group of girl ‘players’ who follow certain rules to avoid heartbreak. These girls are cruel and catty, and the indignation expressed by Goodreads reviews is a testament to how well the author captured these characters. But the book shows us how easy it is to get caught up in toxic relationships, and the harm that can result. It encourages us to emerge from such relationships, stronger and wiser, and may even help us understand these flawed characters in a redemptive way.

In one of my favorite books, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie, Junior’s best friend Rowdy rejects him when Junior switches to an all-white school. But even while Rowdy is beating up on Junior, Alexie somehow makes us care about both of them, showing us the power of best friends to hurt and to heal.

4. Books about friendship give us hope.

One of my favorite adult friendship titles is Waiting to Exhale, by Terry McMillan, about the lives of African American women living in Arizona. Each have their own stories –a woman tries to find Mr. Right, a divorcée rebuilds her life, a mother deals with an empty nest, and a serial dater questions whether she needs a man. What carries these women through their own personal heartbreaks is their friendship with one another.

In writing my debut, UNDER A PAINTED SKY, I wanted to show how essential friendship is to our survival. Samantha, a Chinese violinist, and Annamae, a runaway slave make a perilous escape out of Missouri in 1849. Each has separate missions that will require them to eventually split up, but their unlikely friendship might be the only thing that can save them.

Friendship books assure us that in the midst of life’s worst struggles, as long as we have friends, we can prevail. As the famous Calvin and Hobbes cartoonist Bill Watterson put it, “Things are never quite as scary as when you have a best friend.” I couldn’t agree more.

Friendship books in YA I recommend:

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, Sherman AlexieLove and Other Theories, Alexis BassJellicoe Road by Melina MarchettaThe Orphan Queen, Jodi MeadowsWhen Reason Breaks, Cindy RodriguezWe All Looked Up, Tommy WallachI Am the Messenger, Markus Zusak

Friendship books in my TBR pile:

Tiny Pretty Things, Sona Charaipotra & Dhonielle ClaytonMexican White Boy, Matt De La PeñaBecoming Jinn, Lori GoldsteinThe Distance Between Lost and Found, Kathryn HolmesLucy the Giant, Sherri L. Smith

***

Under a Painted Sky is available now.

You can find more about Stacey in these places: www.staceyhlee.com

@staceyleeauthor [Twitter]

https://www.facebook.com/staceylee.author

https://www.pinterest.com/staceyleeauthor/

https://www.tumblr.com/blog/staceyleeauthor

Related StoriesStrong Heroines: Guest Post by Mary E. PearsonAppropriate Literature: Guest Post by Elana K. ArnoldAbout The Girls: Year Two

Related StoriesStrong Heroines: Guest Post by Mary E. PearsonAppropriate Literature: Guest Post by Elana K. ArnoldAbout The Girls: Year Two

Published on March 24, 2015 22:00

March 23, 2015

Strong Heroines: Guest Post by Mary E. Pearson

Today's guest post comes to us from one of the very first YA authors I read as an adult and one that Kimberly admires: Mary E. Pearson. She's talking about strong heroines, particularly in science fiction and fantasy.

Mary E. Pearson is the author of The Kiss of Deception and many other award-winning books for young adults. You can learn more about Mary and her books here.

March is National Women’s History Month and this year’s theme is about weaving women’s stories into the “essential fabric of our nation’s history.” There are so many strong, amazing women who helped build this country and often they’ve been left out of the historical record. The National History Women’s Project aims to correct that and says, “Accounts of the lives of individual women are critically important because they reveal exceptionally strong role models who share a more expansive vision of what a woman can do. The stories of women’s lives, and the choices they made, encourage girls and young women to think larger and bolder, and give boys and men a fuller understanding of the female experience.”

I think this applies to fiction too. I love reading about strong women. Why shouldn’t I? They are a part of our lives. They are everywhere. Our mothers, daughters, sisters, friends, and colleagues. They inspire us, hold us up, and help to move us forward in our own dreams. They help us to see all that we are and all that we can be, in spite of our flaws, our weaknesses, and fears. The stories of strong women, both in history and in fiction, need to be heard! And heard by both our daughters and our sons.

I’ve had some incredible strong women role models, one of whom was my grandmother. She didn’t take crap from anyone. Maybe it stemmed from an oppressive childhood. She grew up in in a small town in Arkansas, and though she fell in love with one boy, her father forced her to marry another—a man actually—much older than she was. He was “wealthy.” He owned the only car in town which was a big deal back then—at least to her father. It was a loveless marriage and two children later she walked out, defying both her father and her husband. Being a single mother during the Depression wasn’t easy, but somehow she kept her children fed, including the “love child” that came along later. Yes, scandalous for her time, but she made no apologies. She moved forward.

That’s what I’ve seen with the strong women in my life. They may get knocked down; they might make mistakes along the way, but that doesn’t stop them. They move forward drawing on their own unique strengths and the ones they’ve gained on their journey—and there are so many ways to be strong. One way of course, is through plain physical power. I know a lot of women with incredible physical endurance—and ones who can pack a wallop! But there are many shades of strength, including bravery, compassion, intelligence, perseverance, vision, curiosity, cleverness, ambition, resolve, and so many more.

I love seeing the whole spectrum in so many amazing heroines. In celebration of Women’s History Month, I’d like to share a few of my favorites from recent reads:

Sybella

Sybella

Oh Sybella, how I ached for you. From the time she was introduced in the first book of the series, I was pricked with curiosity about the depth of her story. When at last it unfolded in Dark Triumph, I was undone. Yes, it is a fantasy novel, but Sybella’s story cut me to the quick with its gritty realism. Sybella somehow finds the strength to reach deep and overcome a lifetime of betrayals. She broke my heart and then pieced it back together again with hope. I loved all the female protagonists in the His Fair Assassin series by Robin LaFevers, but Sybella’s strength melted into my core.

Charley

Charley

Charley is fun. She is clever. She is strong. She’s the kind of girl you want for a best friend—whether you’re a guy or a girl. She is resourceful, and has a sense of humor even as she is desperately trying to survive after being thrown into the most dire of circumstances on an island—without food, water, or clothes. Yes, she is naked, which she notes with all the shock and horror that my own seventeen year-old self would have had. Charley, the main protagonist in Lynne Matson’s debut, NIL, has stuck with me and still makes me smile when I think of her. She is a survivor.

Cress

Cress

Humorous like Charley, Cress is a different kind of survivor. She’s on an island of another sort, a prisoner in a satellite high above the earth. Locked away from almost all human contact, Cress uses her imagination to survive. She is a dreamer and envisions a different life from the one she has had. Yes, Cress is flawed and naïve—what else could you expect from someone who has had to endure a life of isolation—but she is also skilled at things like hacking computer systems and when she realizes how she has been used, she puts those skills to good use. In her naivety Cress is so different from the other heroines in Marissa Meyer’s Lunar Chronicles, but that is what captured my heart too. Her world has only been seen through the lens of a netscreen and from that she pieces together some semblance of a life—until she has the opportunity to grab for another.

Celaena

Celaena

She’s a bad ass. There is no other way to say it. Dangerous and driven, violence is all Celaena has ever known. She was raised to be an assassin—and she’s damn good at it. But besides setting her adversaries on edge with her knife skills, she can do it with her humor too. That’s my kind of girl. She lets no strength go unmined. My grandmother would love her. So do I. I’ve only read the first book in The Throne of Glass series by Sarah J. Maas, but I can’t wait to see what mayhem Celaena stirs in the rest.

For the sake of space, I’ll have to use shorthand here, but more strong heroines I loved were Kestrel from The Winner’s Curse (clever and calculating!), Wilhelmina from The Orphan Queen (courageous and determined!), Rosie from The Vault of Dreamers (curious, creative, and brave!) and . . . okay, there are a lot of great heroines out there.

Even though all the stories I’ve mentioned are fantasy, I think the fantasy elements help illuminate the very real strengths in all of us. All these incredible heroines had tough choices to make, just as we all do every day, and they meet the challenges of their fate and circumstances through trial and error, calculations and intelligence, missteps and perseverance, vision and triumph—and plenty of badassery. Sometimes a girl’s gotta do what a girl’s gotta do.

The NWHP says, “There is a real power in hearing women’s stories” and I couldn’t agree more. The female voice, experience, and perspective is unique, and reading about it enriches all of our lives, girls and women, boys and men alike.

There! Go link arms with one of these women and let them take you on a powerful journey.

***

Kiss of Deception is available now. The sequel, The Heart of Betrayal, will be available July 7.

Related StoriesAppropriate Literature: Guest Post by Elana K. ArnoldAbout The Girls: Year TwoWrapping Up "About the Girls"

Related StoriesAppropriate Literature: Guest Post by Elana K. ArnoldAbout The Girls: Year TwoWrapping Up "About the Girls"

Published on March 23, 2015 22:00

March 22, 2015

Appropriate Literature: Guest Post by Elana K. Arnold

Today's "About the Girls" guest post is from author Elana K. Arnold. She's here to talk about the idea of "appropriate literature" and how that applies to girls, girls reading, and feminism.

Elana K. Arnold has a master's degree in Creative Writing from UC Davis. She writes books for and about young people and lives in Huntington Beach, California with her family and more than a few pets. Visit Elana at www.elanakarnold.com.

A few days ago, I got an email. This is what it said:

“My 13 year old daughter is interested in reading your books. I research novels before she reads them to ensure they are age appropriate. Can you please provide me with information regarding the sexual content, profanity, and violence so I can make an informed decision.”

The subject of the email was: Concerned Mother.

I’m not proud to admit that my first reaction was a twist in my stomach, a lurching sensation. Was I attempting to lead her daughter astray, were my books nothing more than thinly disguised smut, or pulp?

And I wasn’t sure how to respond. Yes, my books have sexual content. They have profanity. There is violence. But my books—like all books—are more than a checklist, a set of tally marks (Kisses? 6. Punches thrown? 4.)

Then I began thinking about myself at thirteen, about what was appropriate for me in that year, and those that followed.

When I was thirteen, I read whatever I wanted. No one was watching. Largely I found books in my grandmother’s home library. I roamed the shelves and chose based on titles, covers, thickness of the spines. I read All You Ever Wanted To Know About Sex (But were afraid to ask). I read The Stranger. I read Gone with the Wind. And I read at home too, of course, and in school—Anne of Green Gables and Bridge to Terabithia and Forever.

Those early teen years were steeped in sex, even though I wasn’t sexually active. In junior high school, there were these boys who loved to snap the girls’ bras at recess. I didn’t wear a bra, though I wished desperately for the need to. I was sickened by the thought that one of the boys might discover my secret shame, reach for my bra strap and find nothing there.

So one day I stole my sister’s bra and wore it to school. All morning I was aware of the itch of it, its foreign presence. I hunched over my work, straining my shirt across my back so the straps would show through.

At recess, I wandered dangerously near the group of boys, heart thumping, hoping, terrified. Joe Harrison did chase me—I ran and yelped until he caught me by the arm, found the strap, snapped it.

And then his words—“What are you wearing a bra for? You don’t have any tits.”

The next year, there was a boy—older, 15—who didn’t seem to care whether or not I needed a bra. We kissed at a Halloween party, just days after my thirteenth birthday. I was Scarlett O’Hara. He was a 1950’s bad boy, cigarettes rolled into the sleeve of his white T-shirt. He was someone else’s boyfriend.

The next day at school, a well-meaning girl whispered to me, just as class was about to start, “If you’re going to let him bang you, make him finger bang you first. That way, it won’t hurt as much.”

Later that year, before I transferred schools when my family moved away, my English teacher told me I was talented, and that he would miss me. Then he kissed me on the mouth.

The next year, a high school freshman, I was enrolled in Algebra I, and I didn’t think I was very good at it. Truthfully, I didn’t pay much attention to whatever the math teacher/football coach was saying up there, preferring to scribble in my notebook or gaze into half-distance, bringing my eyes into and out of focus.

On the last day of class, the teacher called me up to his desk. “You should fail this class,” he told me. “You went into the final with a D, and you got less than half of the questions right.”

I had never failed a class. I was terrified.

“But,” he went on, smiling, “I’m gonna give you a C-, because I like the way you look in that pink leather miniskirt.”

At fifteen, a sophomore, I took Spanish. I raised my hand to ask a question, and the teacher—who liked the students to call him Señor Pistola—knelt by my desk as I spoke. When I finished, instead of answering me he said, “Oh, I’m sorry. I didn’t hear a word. I was lost in your beautiful eyes.”

I wasn’t having sex. I had only kissed one boy. But still, I was brewing in it—sex, its implications, my role as an object of male desire, my conflicting feelings of fear and excitement.

Recently, I taught an upper division English class at the University of California, Davis. The course topic was Adolescent Literature. Several of my book selections upset the students, who argued vehemently that the books were inappropriate for teens because of their subject matter—explicit sexual activity, sexual violence, and incest. The Hunger Games was on my reading list, too, a book in which the violent deaths of children—one only twelve years old—are graphically depicted. No one questioned whether that book was appropriate. Of course, none of the characters have sex. Not even under the promise of imminent death do any of the featured characters decide to do anything more than kiss, and even the kissing scenes end before they get too intense.

So I think about the mother who wrote me that email, asking me, Are your books appropriate for my daughter? I think about the girl I was at thirteen, and the girls I knew. The girl who told me about finger banging. The other girls my English teacher may have kissed. The girls who had grown used to boys groping their backs, feeling for a bra strap, snapping it.

I think, What is appropriate? I want to tell that mother that she can pre-read and write to authors and try her best to ensure that everything her daughter reads is “appropriate.” But when I was thirteen, and fourteen and fifteen, stealing my sister’s bra and puzzling over the kiss of the boy at the party, the kiss of my teacher in an empty classroom, what was happening to me and around me and inside of me probably wouldn’t have passed that mother’s “appropriate” test. Still, it all happened. To a good girl with a mother who thought her daughter was protected. Safe.

And it was the books that I stumbled upon—all on my own, “inappropriate” books like Lolita and All You Ever Wanted to Know about Sex—these were the books that gave me words for my emotions and my fears.

Maybe the books I write are appropriate. Maybe they are not. But I think it should be up to the daughters to make that decision, not the mothers. Censorship—even on a familial level—only closes doors. We may want to guard our daughters’ innocence, we may fear that giving them access to books that depict sexuality in raw and honest ways will encourage them to promiscuity, or will put ideas in their heads.

I don’t think our daughters need guardians of innocence. I think what they need is power.

Let your daughter read my books, Concerned Mother. Read them with her. Have a conversation. Tell her your stories. Let her see your secrets, and your shames. Arm your daughter with information and experience.

Give her power.

***

Infandous is available now.

Related StoriesAbout The Girls: Year TwoWrapping Up "About the Girls"Links of Note: March 22, 2014

Related StoriesAbout The Girls: Year TwoWrapping Up "About the Girls"Links of Note: March 22, 2014

Published on March 22, 2015 22:00

March 21, 2015

About The Girls: Year Two

Tomorrow kicks off our second annual "About the Girls" series here at STACKED. It's nearly two weeks of guest posts about girls, girl reading, and feminism in honor of Women's History Month. We dedicate so much time to boys and their reading and interests but spend hardly a fraction of the same time considering the question "what about the girls?" That's what this series hopes to address. If you missed last year's series, spend some time with it.

I didn't prompt my guests with anything. I left it open to them to decide what it was they wanted to talk about when it came to girls, girls reading, and feminism in YA. Each guest came up with something entirely unique and yet, the entire series builds upon itself. There is a lot to think about and discuss with each of these posts, which range from discussing the role of abortion within and outside of YA fiction to girls who kick serious ass in science fiction. As with last year's series, I hope readers walk away with a lot to think about when it comes to teen girls, their reading habits, and their interests, and I hope that every reader walks away with at least one new book added to their reading lists. I spent a long time making decisions on who to invite to this series, as I wanted a wide variety of voices, experiences, and backgrounds at the table.

Because I envision this series as a conversation, I open up the floor to readers and other bloggers to feel free to write "about the girls" in some capacity before March ends. Those who do and would like their work shared, feel free to pass along links to me. I would be thrilled to round them up into another post for STACKED readers to check out. You can talk about favorite female characters, favorite female authors, or about anything girls or girls reading related. The only "goal" is that it be an answer to that question, "what about the girls?" It's my hope to post a few times outside the guest posts with pieces of interest or connection to this series as well.

We've seen a lot of discussion about sexism and about girls and feminism in the last few months on social media. But rather than dive into specifics, I wanted to instead highlight what I think is an important and worthwhile campaign happening on April 14: #ToTheGirls. The campaign, run by YA author Courtney Summers, is about telling girls how important they are and why they matter. All it asks is on that date, you share something to the girls and tell them why they matter, why their voices are important, and that they're loved. It's easy, simple, free, and it can make a tremendous impact on girls who hear that message. All of the details are here. If you're on social media, I encourage you to take part.

Read these posts. Think about them. Talk about them. Share them. Get ready to get invested in girls, girls reading, and their complex, challenging, and rich lives.

Related StoriesWrapping Up "About the Girls"Links of Note: March 22, 2014Challenging the Expectation of YA Characters as "Role Models" for Girls: Guest Post by Sarah Ockler

Related StoriesWrapping Up "About the Girls"Links of Note: March 22, 2014Challenging the Expectation of YA Characters as "Role Models" for Girls: Guest Post by Sarah Ockler

Published on March 21, 2015 22:00

March 19, 2015

This Week at Book Riot

Due to last week's need to get off social media, I didn't pull together the posts I'd written on Book Riot over here on Friday. I also decided to take a much-needed writing break at Book Riot this week, so all of these pieces are from last week. Not that that really matters!

This week, I put the finishing touches on the first YA Quarterly Box for Book Riot, including writing a letter to subscribers about the contents and why I chose them. That was a blast. I hope anyone who subscribed finds the picks to be exciting, fun, and perhaps even surprising choices.

Coming up next week is Stacked's second annual "About the Girls" blog series. It's fortuitous timing, but it's been in the works for over a month now, and the guest posts from a variety of authors and other industry folks are outstanding. The introduction will go up this weekend and you'll get the chance to enjoy nearly two weeks of great, thought-provoking posts on girls, girl reading, and feminism.

Onto the posts at Book Riot:

For 3 On A YA Theme, I highlighted 3 books with awesome black teen faces right on the cover.

These two posts rounding up literary and bookish Final Jeopardy! answers took me five months to put together. But they were a blast, and I hope anyone who is a fan of trivia enjoys these. Part one and Part two.

I took on the "Buy, Borrow, Bypass" feature and talked about three recent YA books that feature diverse teen girl duos. They're all absolutely worth reading.

Related StoriesThis Week at Book Riot

Related StoriesThis Week at Book Riot

Published on March 19, 2015 22:00

March 18, 2015

March Debut YA Novels

I don't know if it's this way everywhere, but this March is already a welcomed weather relief. As I'm putting together, I have my windows open because it's 60 degrees and there's almost no snow left on the ground.

Like always, this round-up includes debut novels, where "debut" is in its purest definition. These are first-time books by first-time authors. I'm not including books by authors who are using or have used a pseudonym in the past or those who have written in other categories (adult, middle grade, etc.) in the past.

All descriptions are from WorldCat, unless otherwise noted. If I'm missing any debuts out in February from traditional publishers, let me know in the comments. As always, not all noted titles included here are necessarily endorsements for those titles.

Duplicity by N. K. Traver: When seventeen-year-old Brandon, a tattooed bad boy skilled in computer hacking, is sucked into a digital hell and replaced with a preppy Stepford-esque clone, his life and sanity rest on the shoulders of a classy girl he never thought he would fall for.

Under A Painted Sky by Stacey Lee: In 1845, Sammy, a Chinese American girl, and Annamae, an African American slave girl, disguise themselves as boys and travel on the Oregon Trail to California from Missouri.

The Wrong Side of Right by Jenn Marie Thorne: After her mother dies, sixteen-year-old Kate Quinn meets the father she did not know she had, joins his presidential campaign, falls for a rebellious boy, and when what she truly believes flies in the face of the campaign's talking points, Kate must decide what is best.

Everything That Makes You by Moriah McStay: In alternating voices, Fiona "Fi" Doyle experiences her teen years in two ways, with and without a disfiguring accident that occurred at age six, dealing with its effects on her brother and parents, her friendships, her dating life, her involvement in sports and hobbies, her future plans, and especially her self-image.

Mosquitoland by David Arnold: After the sudden collapse of her family, Mim Malone is dragged from her home in northern Ohio to the "wastelands" of Mississippi, where she lives in a medicated milieu with her dad and new stepmom. Before the dust has a chance to settle, she learns her mother is sick back in Cleveland. So she ditches her new life and hops aboard a northbound Greyhound bus to her real home and her real mother, meeting a quirky cast of fellow travelers along the way. But when her thousand-mile journey takes a few turns she could never see coming, Mim must confront her own demons, redefining her notions of love, loyalty, and what it means to be sane.

The Storyspinner by Becky Wallace: The Keepers, a race of people with magical abilities, are seeking a supposedly-dead princess to place her on the throne and end political turmoil, but girls who look like the princess are being murdered and Johanna Von Arlo, forced to work for Lord Rafael DeSilva after her father's suspicious death, is a dead-ringer.

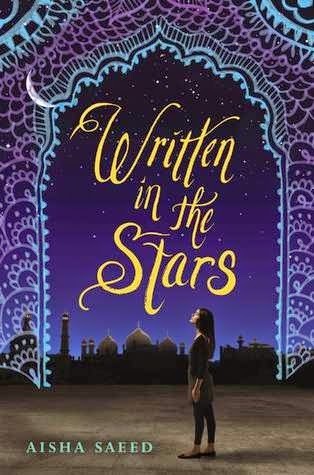

Written in the Stars by Aisha Saeed: Naila's vacation to visit relatives in Pakistan turns into a nightmare when she discovers her parents want to force her to marry a man she's never met.

Solitaire by Alice Oseman: In case you're wondering, this is not a love story. My name is Tori Spring. I like to sleep and I like to blog. Last year - before all that stuff with Charlie and before I had to face the harsh realities of A-Levels and university applications and the fact that one day I really will have to start talking to people - I had friends. Things were very different, I guess, but that's all over now. Now there's Solitaire. And Michael Holden. I don't know what Solitaire are trying to do, and I don't care about Michael Holden. I really don't.

Unlikely Hero of Room 13B by Teresa Toten: Adam not only is trying to understand his OCD, while trying to balance his relationship with his divorced parents, but he's also trying to navigate through the issues that teenagers normally face, namely the perils of young love.

My Best Everything by Sarah Tomp: When her father loses her college tuition money, Lulu works with Mason, a local boy, making and selling moonshine but their growing romance may mean giving up her dream of escaping her small Virginia hometown.

Dead to Me by Mary McCoy: In 1948 Hollywood, a treacherous world of tough-talking private eyes, psychopathic movie stars, and troubled starlets, sixteen-year-old Alice tries to find a young runaway who is the sole witness to a beating that put her sister, Annie, in a coma.

How to Win at High School by Owen Matthews: Partly for the sake of his brother Sam, who is paralyzed, Adam decides to go from high school loser to god by selling completed homework assignments, buying alcohol, and arranging for fake IDs, but before the end of junior year, he realizes his quest for popularity has gone way too far.

The Memory Key by Liana Liu: In the not-so-distant future, everyone is implanted with a memory key to stave off a virulent form of Alzeimer's. Lora Mint fears her memories of her deceased mother are fading, but when her memory key is damaged she has perfect recall--of everything-- which brings her mother's memory vividly back--but may also drive Lora mad

Related StoriesFebruary Debut YA NovelsJanuary Debut YA NovelsGuest Post: On Writing Realistic, Flawed Parents in YA by Bryan Bliss (& giveaway of NO PARKING AT THE END TIMES)

Related StoriesFebruary Debut YA NovelsJanuary Debut YA NovelsGuest Post: On Writing Realistic, Flawed Parents in YA by Bryan Bliss (& giveaway of NO PARKING AT THE END TIMES)

Published on March 18, 2015 22:00

March 17, 2015

Romance Roundup

Any Duchess Will Do by Tessa Dare

I read a Tessa Dare book a couple of years ago and was underwhelmed. But I keep seeing her on lists of favorites, so I decided I’d give her another try. I’m glad I did. Any Duchess Will Do is funny, swoony, and narrated quite well by Eva Kaminsky, who nails both the upper-crust English voice of the hero (a duke) and the lower-class English voice of the heroine (a serving girl). It’s a re-telling of Pygmalion/My Fair Lady, in a way: the duke claims he will not get married, his mother tells him he must, he picks out a serving girl to annoy her, the mother says “game on” and decides to turn the serving girl into a duchess, hoping her son will then marry her.

The duke, Griffin, is kind of a jerk, but not in an “I’m going to go out of my way to make you feel awful” way. It’s more of an “I’m just concerned with myself and only myself” way. He makes an appearance in a previous book in the series, where he comes off rather badly. He does better for himself here. I doubted Dare’s ability to make me see him sympathetically, but she does a good job. Pauline, the serving girl, is a vastly more interesting character though. She has aspirations to start a library, stocked with naughty books for the ladies of her town to read, and she agrees to go through duchess training because Griffin has agreed to pay her to do a bad job and help get his mother off his back. The money he promises her will start the library. The pairing is a little different from most romances (where the woman is usually high-born), making this a refreshing read.

Just Like Heaven by Julia Quinn

I’ve read two of the other books in Quinn’s Smythe-Smith quartet, which share a universe with her much-beloved Bridgerton series. I didn’t really love them. They weren’t terrible, but their leads didn’t have much chemistry, the stakes felt ridiculous, and there wasn’t much personality to them – surprising to me, since Quinn’s books are usually loaded with personality. That’s what makes her so hugely popular.

Just Like Heaven, narrated by Rosalyn Landor, is actually pretty good. It’s the first book in the series (I read romance series out of order since there’s really no spoiling anything here) and it’s a sweet one. It doesn’t put its characters through the wringer. The hero isn’t particularly tortured and the heroine not particularly self-doubting or put upon by others. They love their families and have been friends for years. They actually get together rather easily, compared to most romances I’ve read lately. If this sounds a little boring, that’s because it sort of is. It’s not Quinn’s best work, but coming off of the other two disappointing books, it was nice to get a solid one. And there’s always room for the sweet stuff in historical romance. We don’t need all Tragic Heroes all the time.

The Luckiest Lady in London by Sherry Thomas

My previous experiences with Sherry Thomas have all been with her YA books, which are excellent. This was my first historical romance by her and I’m so sad my library doesn’t own anything else of hers on audio. Corrie James narrates this one, and she does an excellent job – but it’s Thomas’ writing that carries it.

The book features a hero whose parents modeled a loveless, manipulative marriage and a heroine who must marry well in order to support her impoverished family. Neither is looking for love, and when they marry each other, they don’t expect to find it. I’m not normally a fan of romances where marriage happens before deep affection or love, but this one works really well. Thomas’ writing is sharp, her portraits of these two flawed characters well-done. The exchanges between the two leads are witty, like the best banter from the Bridgerton books, but with a darker edge. I thoroughly believed in their attraction at the outset and their love at the end. There’s no real “hook” to this story plot-wise that sets it apart from others; it’s the execution that makes it shine.

Related StoriesRomance Roundup - Sarah MacLean EditionWritten in the Stars by Aisha SaeedThe Only Thing to Fear by Caroline Tung Richmond

Related StoriesRomance Roundup - Sarah MacLean EditionWritten in the Stars by Aisha SaeedThe Only Thing to Fear by Caroline Tung Richmond

Published on March 17, 2015 22:00

March 16, 2015

Written in the Stars by Aisha Saeed

Naila is a first-generation American, the daughter of conservative Pakistani immigrants. Her parents allow her a fair amount of freedom, they think: she can choose her friends and what she studies in college and what her career will be, but boys are off-limits. They will choose her husband.

Naila is a first-generation American, the daughter of conservative Pakistani immigrants. Her parents allow her a fair amount of freedom, they think: she can choose her friends and what she studies in college and what her career will be, but boys are off-limits. They will choose her husband. But Naila has fallen in love with a classmate, Saif, a boy of whom she knows her parents will disapprove. When they find out, they are disappointed, angry, outraged. They decide to visit Pakistan over the summer, ostensibly to help Naila learn about her culture and her heritage. Naila actually enjoys her time there, getting to know family she has never met and a place she’s never been. But her parents keep delaying their return to the United States, and Naila eventually learns the reason for the frequent visits from families with young sons: her parents intend to marry her off, and Naila will not have a choice in the matter.

This is a nail-biter of a book. It’s under 300 pages with relatively large text and short chapters. Naila’s knowledge of her impending forced marriage comes rather late in the book, but it’s something the reader has known all along (provided they read the jacket flap). I think this actually heightens the tension, allowing us to keep our eyes peeled for clues and hoping against hope that Naila will figure it out soon enough. She doesn’t. Her escape attempts are harrowing. Saeed is very good at getting us inside Naila’s head, letting us see just how terrifying it is to be alone, in a country you know very little about, where no one seems to wish you well. Where your own family treats you as less than a person.

The following paragraph is somewhat of a spoiler, but I think it’s important to discuss in my review, so you can feel free to skip to the next paragraph if you want to go in relatively blind. Once Naila’s marriage actually happens, the book takes a turn into some very dark territory. She’s deposited on her new family’s doorstep, and now lives with him and her mother-in-law plus two sisters-in-law. None of them are sympathetic to her. None of them care that she didn’t want this marriage. None of them even think to ask. (“Life is full of sadness. It’s part of being a woman. Our lives are lived for the sake of others. Our happiness is never factored in,” one of her new sisters-in-law tells her.) Her mother-in-law has no patience with Naila’s sadness and treats her cruelly. Her husband rapes her. She becomes pregnant. She has no passport and no visa and no method of transportation. Her immediate family has returned to America. She becomes resigned to her new life. It’s hard to read about, but it’s honest and wouldn’t have been a believable part of the story otherwise.

Despite the book’s brevity, Saeed packs a lot into it. Her writing style is simple, but it works for Naila’s story and the voice is authentic. Her descriptions of Pakistan, of the markets and the food and the buses and the packed house with visiting aunts and cousins, sprinkled with Urdu words, paint a vivid picture. It’s not difficult to see why Naila falls in love with the place and with her extended family.

Saeed’s own experience with a happy, arranged marriage (not a forced marriage, as Naila’s is) adds interest to the novel. Along with Saeed’s deft descriptions of Pakistan and the people not directly involved in Naila’s marriage, it helps prevent the book from being an indictment of Pakistani culture for non-Pakistani readers (not necessarily the most vital thing, but important when providing windows to young readers). It’s also important to note that arranged marriages (by choice or forced) happen in many cultures, including Western ones, which is something Saeed addresses in her author’s note.

Written in the Stars is a debut novel and it’s not perfectly polished. Some transitions happen too quickly or seem awkward, and the ending is rushed. Despite the imperfections, this is a heck of a book, one that I read in a single sitting and that should have high appeal to teens. I think the concept sells itself, particularly when I consider that it’s written like a thriller but actually happens to teenage girls (not the case with a lot of thrillers). It’s fascinating, intense, horrifying, and ultimately hopeful – a novel packed with love and a great deal of nuance. Definitely worth a read.

Written in the Stars will be published March 24. I received a finished copy from the publisher.

Related StoriesRealistic YA Review Round-Up: This Side of Home by Renee Watson, I'll Meet You There by Heather Demetrios, and Read Between the Lines by Jo KnowlesThe Only Thing to Fear by Caroline Tung RichmondBooklist: Synesthesia in Middle Grade and YA

Related StoriesRealistic YA Review Round-Up: This Side of Home by Renee Watson, I'll Meet You There by Heather Demetrios, and Read Between the Lines by Jo KnowlesThe Only Thing to Fear by Caroline Tung RichmondBooklist: Synesthesia in Middle Grade and YA

Published on March 16, 2015 22:00

24 Thoughts on Sexism, Feminism, YA, Reading, and The Publishing Industry

This requires no more introduction than saying it's a handful of thoughts worth considering and working through after the last week.

1. My feminism isn't about making you comfortable.

As a feminist, I am not obligated to make you comfortable. As a feminist, what I owe is honesty, integrity, and truth, no matter how uncomfortable it is. Not liking my feminism is your problem, not mine.

2. Being part of an oppressed class means using subversive means.

Having a conversation in a calm, collective, "professional" manner depends entirely on how we define calm, collective, and "professional." Those definitions are made through those in positions of power and privilege. And when the powerful class doesn't want a critical lens turned on them, they will deny the oppressed class those calm, collective, "professional" tools.

So you do things in the way you need to to achieve a desired effect. Satire. Humor. Sarcasm. Protesting.

Those who don't want to be criticized and don't want to face the truth won't listen to you anyway, so you do what you can, how you can, in order for everyone else to hear and understand.

3. Means, methods, tools, and places for criticism vary.

You can't use the same critical tools in every situation. Your methods depend entirely upon your goal and on the subject and situation at hand. When talking about an issue of sexism, if talking about the texts at hand won't do the job, then you pick up the next tool available to you. This includes public commentary and interviews.

Sometimes a blog post is effective. Sometimes Twitter is effective. Sometimes Tumblr. Sometimes the best tool isn't online at all but in an interview in person. On a panel discussion. During a Q&A.

If one tool doesn't work, you pick up another.

4. White male allies need to step back.

Quit patting yourself on the back for "empathy," "niceness," or "feminism," especially if you're a "nice, empathetic, feminist white guy."

Use your platforms and your privilege to amplify the voices of the oppressed. You don't need to interpret it through your perspective. Let others have your stage for a bit and listen.

As Eric Mortenson put so well -- and this is hands down one of the best things I read this week: "If you're really on women's side, you don't need to tell them. They'll know."

5. We love amplifying the white male ally voice.

Take a hard look at whose voices you're relating to and sharing. If it looks like a sea of white men, reassess.

Watch who you're crediting when you're crediting an internet "kerfluffle." Watch who you're crediting when you're crediting a discussion of sexism in publishing.

Bet it's not the same people getting credit.

6. When you speak in generalities, people insist on examples. When you provide examples, you're called a bully.

When you talk about institutional sexism in a broad sense, people want explicit examples. But when you provide explicit examples, you're a bully for doing the very thing you were told you needed to do in order to prove your arguments legitimate.

7. "Nice" doesn't mean above criticism.

Plenty of nice people screw up every day. Plenty of nice people have good intentions.

Your "niceness" doesn't mean you're above being critiqued or above being called out for a thing you did that's not good. Your "niceness" doesn't absolve you from responsibility. Your "niceness" has zero bearing on what you create and the art or thought you put out in the world.

8. Art and artist are not one in the same. It is HARD to separate art from artists, as well as art from personal taste.

We are complex, challenging creatures. We don't always know what we're doing when we're doing it. We don't always know what we've created until it's outside of ourselves. Let's be generous enough to allow artists to live separately from the art they've created.

Art and artist are also separate from personal taste. You may find someone's art distasteful; I may find it enjoyable. That is not a reflection upon the artist or his talent.

9. Girls don't get points for experimenting. They have to get it right the whole way through. Men are right when they try, even if they fail.

"Trying" to be better isn't the same as being better. Especially in a world where women can never be right and are never getting better.

"Trying" doesn't pass for women.

10. We insist we love critics and criticism until the heat is on.

Back in the day, artists used to critique one another and did so harshly. There wasn't fear that saying something critical about another artist's work meant doom for your own career.

Now that we rely on outside critics more often than not, in the form of trade reviews and yes, blog reviews, we constantly talk about the important role those criticisms play. Those who take this seriously do so because they care deeply about the art and they care deeply about representation, voice, accuracy, and a whole host of other things.

But as soon as critics start to actually criticize art, suddenly, they're out for blood. They're the enemies. They have a vendetta.

11. Criticism isn't easy, and it certainly isn't fun.

It would be worthwhile to praise those critics who work with the heat is on high as much as it's worthwhile to continually pat those on the back who praise things generously, with less criticism.

There are people who are absolutely, positively dedicated to change and fair representation. They put their criticisms out there every day in hopes of sparking change.

It's not easy.

It's NECESSARY.

It makes us BETTER.

12. You don't get to determine whether someone's concerns about sexism, or any other -ism, is correct or incorrect.

Just because it isn't sexist to you doesn't mean it's not sexist to those who are speaking up about it, as well as the legions who are too scared to speak up or don't have the means to speak up.

13. Nothing is either/or, but/and. Everything is a spectrum. Everything is complex.

Calling out a weakness in an author's work -- or a series of work -- doesn't mean that the rest of the work is done poorly. Badly drawn female characters are not an indictment against how the boys are written.

Suggesting that girls should be fully developed characters doesn't take away from boys being fully developed or being the absolute center of the story. It's not saying the books are bad.

It means readers want these stories, where both boys and girls are fully developed.

14. Sometimes people who are "outsiders" have to speak up because insiders are too close to the source.

Outsiders are reading the criticism. They offer a perspective that those too close to the art could never offer without bias.

Critics put their work out into the world for outsiders, not insiders.

It's your job to help your friends and colleagues. It's not mine.

15. Being called out sucks. Learn and do better.

We are all problematic. We are not without fault. And when you're called out on something, it sucks, especially if you were trying everything to not be wrong. Sometimes you still are.

I am not above being called out. You are not above being called out. No one is.

Learn from your mistakes. Listen to those who are offering you insight. Then DO better. When you're given the chance to learn from your mistakes, take it.

It takes privilege to leave the conversation before it's over. And certainly, when you decide you're exiting a conversation, rather than acknowledging it's even happening -- even with a simple "I am busy and can't talk about this right now but will soon" -- you're not listening.

Listening means sticking around for the hard parts.

16. There aren't fair levels of scaffolding in this industry. Be aware of yours and what others are.

Critics don't usually have agents, editors, publicists, publishing houses or any other level of scaffolding behind them. There aren't other people to step in and do damage control or offer up insight into process.

If there are people on your side with a financial stake in your career when you go up to bat for something, are selling a product, or creating art, you're damn lucky.

17. You don't get to invoke someone's personal life as an excuse or value judgment. That's theirs and theirs alone.

You aren't empathetic or understanding when you invoke my mental illness as part of your "being understanding" of what I may be going through when I speak out. You also aren't entitled to bring someone else's personal life into the explanation for their creative weaknesses.

Those things are personal and the individual owning them is the only person who gets to invoke them in discussion, even if they've been open about it.

18. If you express criticism directly at someone, you're a bully. If you don't, you're subtweeting/talking about them behind their backs.

Damned if you do, damned if you don't. See #6. See #12.

19. Criticism isn't bullying.

The purest definition of bullying is this: when a person with superior strength or influence uses their their influence to force a person to do what s/he wants.

Speaking up about sexism isn't bullying.

Being told you should die and never come back or else you'll be given a reason never to come back is bullying.

20. No one likes being called a cunt, a whore, a bitch, a pain in the ass, and no one deserves to be told they should be given something to be scared about.

Women don't often engage in conversation about sexism because they are fun and the rewards are high.

21. People go to the ends of the Earth to defend a nice guy. People don't defend women in the same way.

See: #KeepYAKind, #GrasshopperGate, #AndrewSmith, change your avatars to a Smith cover, buy all of the Smith books, give away all of the Smith books.

The only reason I (and others, all female) knew people cared about me or defended my right to say what I did and how I did it was because I was reached out to.

Privately.

Those who agree with you most are the ones with the most to lose if they speak up. Speaking up without fear of career consequence is a privilege I have that many others in this industry -- those who experience the DIRECT CONSEQUENCES OF SEXISM IN THIS INDUSTRY THIS IS DIRECTED TOWARD IN THE FIRST PLACE -- do not.

Because that's how institutionalized sexism and racism work.

22. True feminism isn't about ideation. It's about action.

If you don't put your money where your mouth is, you're not working toward a solution to the problem. You're hot air.

You can't just believe in change. You have to be an active part of doing something about it.

And it's not only about women. It's about ALL classes of people that face oppression.

I assure you straight white males are not part of the oppressed. Even if they think they are.

23. These conversations are born from hurt

No one decides overnight to highlight direct examples of sexism.

They are the result of people being hurt over a long time.

24. I have the right to speak.

The risk of speaking up for women, as a woman, is great and often ends in threats of violence and death. When I told another woman I don't know how some feminists do this every single day, she said, "If you stay, as a woman in this fight, you end up steel whether you want to or not."

For further reading:

Anne Ursu on Some Exhibits in YA Coverage and Kindness, Sexism, and This Infernal MessSarah McCarry On KindnessLeila Roy on If You Don't Have Anything Nice to SayAna at The Book Smugglers on Andrew Smith, Systematic Sexism, and the Call for KindnessTessa Gratton on Andrew Smith and Sexism and In Which I Keep TalkingPhoebe North on Why

Related StoriesThis Week in Reading: Volume 12The Rise of Suicide in YA Fiction and Exploring Personal Biases in ReadingA Pair of Audiobook Reviews

Related StoriesThis Week in Reading: Volume 12The Rise of Suicide in YA Fiction and Exploring Personal Biases in ReadingA Pair of Audiobook Reviews

1. My feminism isn't about making you comfortable.

As a feminist, I am not obligated to make you comfortable. As a feminist, what I owe is honesty, integrity, and truth, no matter how uncomfortable it is. Not liking my feminism is your problem, not mine.

2. Being part of an oppressed class means using subversive means.

Having a conversation in a calm, collective, "professional" manner depends entirely on how we define calm, collective, and "professional." Those definitions are made through those in positions of power and privilege. And when the powerful class doesn't want a critical lens turned on them, they will deny the oppressed class those calm, collective, "professional" tools.

So you do things in the way you need to to achieve a desired effect. Satire. Humor. Sarcasm. Protesting.

Those who don't want to be criticized and don't want to face the truth won't listen to you anyway, so you do what you can, how you can, in order for everyone else to hear and understand.

3. Means, methods, tools, and places for criticism vary.

You can't use the same critical tools in every situation. Your methods depend entirely upon your goal and on the subject and situation at hand. When talking about an issue of sexism, if talking about the texts at hand won't do the job, then you pick up the next tool available to you. This includes public commentary and interviews.

Sometimes a blog post is effective. Sometimes Twitter is effective. Sometimes Tumblr. Sometimes the best tool isn't online at all but in an interview in person. On a panel discussion. During a Q&A.

If one tool doesn't work, you pick up another.

4. White male allies need to step back.

Quit patting yourself on the back for "empathy," "niceness," or "feminism," especially if you're a "nice, empathetic, feminist white guy."

Use your platforms and your privilege to amplify the voices of the oppressed. You don't need to interpret it through your perspective. Let others have your stage for a bit and listen.

As Eric Mortenson put so well -- and this is hands down one of the best things I read this week: "If you're really on women's side, you don't need to tell them. They'll know."

5. We love amplifying the white male ally voice.

Take a hard look at whose voices you're relating to and sharing. If it looks like a sea of white men, reassess.

Watch who you're crediting when you're crediting an internet "kerfluffle." Watch who you're crediting when you're crediting a discussion of sexism in publishing.

Bet it's not the same people getting credit.

6. When you speak in generalities, people insist on examples. When you provide examples, you're called a bully.

When you talk about institutional sexism in a broad sense, people want explicit examples. But when you provide explicit examples, you're a bully for doing the very thing you were told you needed to do in order to prove your arguments legitimate.

7. "Nice" doesn't mean above criticism.

Plenty of nice people screw up every day. Plenty of nice people have good intentions.

Your "niceness" doesn't mean you're above being critiqued or above being called out for a thing you did that's not good. Your "niceness" doesn't absolve you from responsibility. Your "niceness" has zero bearing on what you create and the art or thought you put out in the world.

8. Art and artist are not one in the same. It is HARD to separate art from artists, as well as art from personal taste.

We are complex, challenging creatures. We don't always know what we're doing when we're doing it. We don't always know what we've created until it's outside of ourselves. Let's be generous enough to allow artists to live separately from the art they've created.

Art and artist are also separate from personal taste. You may find someone's art distasteful; I may find it enjoyable. That is not a reflection upon the artist or his talent.

9. Girls don't get points for experimenting. They have to get it right the whole way through. Men are right when they try, even if they fail.

"Trying" to be better isn't the same as being better. Especially in a world where women can never be right and are never getting better.

"Trying" doesn't pass for women.

10. We insist we love critics and criticism until the heat is on.

Back in the day, artists used to critique one another and did so harshly. There wasn't fear that saying something critical about another artist's work meant doom for your own career.

Now that we rely on outside critics more often than not, in the form of trade reviews and yes, blog reviews, we constantly talk about the important role those criticisms play. Those who take this seriously do so because they care deeply about the art and they care deeply about representation, voice, accuracy, and a whole host of other things.

But as soon as critics start to actually criticize art, suddenly, they're out for blood. They're the enemies. They have a vendetta.

11. Criticism isn't easy, and it certainly isn't fun.

It would be worthwhile to praise those critics who work with the heat is on high as much as it's worthwhile to continually pat those on the back who praise things generously, with less criticism.

There are people who are absolutely, positively dedicated to change and fair representation. They put their criticisms out there every day in hopes of sparking change.

It's not easy.

It's NECESSARY.

It makes us BETTER.

12. You don't get to determine whether someone's concerns about sexism, or any other -ism, is correct or incorrect.

Just because it isn't sexist to you doesn't mean it's not sexist to those who are speaking up about it, as well as the legions who are too scared to speak up or don't have the means to speak up.

13. Nothing is either/or, but/and. Everything is a spectrum. Everything is complex.

Calling out a weakness in an author's work -- or a series of work -- doesn't mean that the rest of the work is done poorly. Badly drawn female characters are not an indictment against how the boys are written.

Suggesting that girls should be fully developed characters doesn't take away from boys being fully developed or being the absolute center of the story. It's not saying the books are bad.

It means readers want these stories, where both boys and girls are fully developed.

14. Sometimes people who are "outsiders" have to speak up because insiders are too close to the source.

Outsiders are reading the criticism. They offer a perspective that those too close to the art could never offer without bias.

Critics put their work out into the world for outsiders, not insiders.

It's your job to help your friends and colleagues. It's not mine.

15. Being called out sucks. Learn and do better.

We are all problematic. We are not without fault. And when you're called out on something, it sucks, especially if you were trying everything to not be wrong. Sometimes you still are.

I am not above being called out. You are not above being called out. No one is.

Learn from your mistakes. Listen to those who are offering you insight. Then DO better. When you're given the chance to learn from your mistakes, take it.

It takes privilege to leave the conversation before it's over. And certainly, when you decide you're exiting a conversation, rather than acknowledging it's even happening -- even with a simple "I am busy and can't talk about this right now but will soon" -- you're not listening.

Listening means sticking around for the hard parts.

16. There aren't fair levels of scaffolding in this industry. Be aware of yours and what others are.

Critics don't usually have agents, editors, publicists, publishing houses or any other level of scaffolding behind them. There aren't other people to step in and do damage control or offer up insight into process.

If there are people on your side with a financial stake in your career when you go up to bat for something, are selling a product, or creating art, you're damn lucky.

17. You don't get to invoke someone's personal life as an excuse or value judgment. That's theirs and theirs alone.

You aren't empathetic or understanding when you invoke my mental illness as part of your "being understanding" of what I may be going through when I speak out. You also aren't entitled to bring someone else's personal life into the explanation for their creative weaknesses.

Those things are personal and the individual owning them is the only person who gets to invoke them in discussion, even if they've been open about it.

18. If you express criticism directly at someone, you're a bully. If you don't, you're subtweeting/talking about them behind their backs.

Damned if you do, damned if you don't. See #6. See #12.

19. Criticism isn't bullying.

The purest definition of bullying is this: when a person with superior strength or influence uses their their influence to force a person to do what s/he wants.

Speaking up about sexism isn't bullying.

Being told you should die and never come back or else you'll be given a reason never to come back is bullying.

20. No one likes being called a cunt, a whore, a bitch, a pain in the ass, and no one deserves to be told they should be given something to be scared about.

Women don't often engage in conversation about sexism because they are fun and the rewards are high.

21. People go to the ends of the Earth to defend a nice guy. People don't defend women in the same way.

See: #KeepYAKind, #GrasshopperGate, #AndrewSmith, change your avatars to a Smith cover, buy all of the Smith books, give away all of the Smith books.

The only reason I (and others, all female) knew people cared about me or defended my right to say what I did and how I did it was because I was reached out to.

Privately.

Those who agree with you most are the ones with the most to lose if they speak up. Speaking up without fear of career consequence is a privilege I have that many others in this industry -- those who experience the DIRECT CONSEQUENCES OF SEXISM IN THIS INDUSTRY THIS IS DIRECTED TOWARD IN THE FIRST PLACE -- do not.

Because that's how institutionalized sexism and racism work.

22. True feminism isn't about ideation. It's about action.

If you don't put your money where your mouth is, you're not working toward a solution to the problem. You're hot air.

You can't just believe in change. You have to be an active part of doing something about it.

And it's not only about women. It's about ALL classes of people that face oppression.

I assure you straight white males are not part of the oppressed. Even if they think they are.

23. These conversations are born from hurt

No one decides overnight to highlight direct examples of sexism.

They are the result of people being hurt over a long time.

24. I have the right to speak.

The risk of speaking up for women, as a woman, is great and often ends in threats of violence and death. When I told another woman I don't know how some feminists do this every single day, she said, "If you stay, as a woman in this fight, you end up steel whether you want to or not."

For further reading:

Anne Ursu on Some Exhibits in YA Coverage and Kindness, Sexism, and This Infernal MessSarah McCarry On KindnessLeila Roy on If You Don't Have Anything Nice to SayAna at The Book Smugglers on Andrew Smith, Systematic Sexism, and the Call for KindnessTessa Gratton on Andrew Smith and Sexism and In Which I Keep TalkingPhoebe North on Why

Related StoriesThis Week in Reading: Volume 12The Rise of Suicide in YA Fiction and Exploring Personal Biases in ReadingA Pair of Audiobook Reviews

Related StoriesThis Week in Reading: Volume 12The Rise of Suicide in YA Fiction and Exploring Personal Biases in ReadingA Pair of Audiobook Reviews

Published on March 16, 2015 05:54