Kelly Jensen's Blog, page 88

April 6, 2015

Get Genrefied: Westerns

IntroductionFor this month's genre guide, we're focusing on Westerns. Classic Westerns that most people are familiar with are usually characterized by their setting: the American frontier in the 18th and 19th centuries. They're often high on action and feature an abundance of cowboys, outlaws, sheriffs, and settlers. They're also known for often problematic depictions of American Indians. Popular authors for adults include Zane Grey, Louis L'Amour, Elmer Kelton, and Larry McMurtry.

IntroductionFor this month's genre guide, we're focusing on Westerns. Classic Westerns that most people are familiar with are usually characterized by their setting: the American frontier in the 18th and 19th centuries. They're often high on action and feature an abundance of cowboys, outlaws, sheriffs, and settlers. They're also known for often problematic depictions of American Indians. Popular authors for adults include Zane Grey, Louis L'Amour, Elmer Kelton, and Larry McMurtry.I have to admit, I've put off writing about Westerns for a while because I just don't read them that often. I'm not the only one: Western reading hit its zenith in the 1960s and has been dropping off ever since. Anecdotally, we've significantly reduced the number of Western titles for adults at my library because they're simply not being read as often as they used to be. There's a bit of a bias against them as being old, dusty, and irrelevant. Even the covers of newly-published Westerns set in contemporary times have a very retro feel.

That doesn't mean there's not a readership for them. When you find westerns in YA, they're usually not marketed as such (probably at least in part because of the bias I mentioned above). Instead, they fall under the umbrella term of historical or contemporary fiction, and the selling point is the adventure or a specific part of the setting (the Oregon Trail, for example), rather than the Western setting in general. This makes searching for YA Westerns a bit more difficult since they're usually not physically delineated in the bookstore or library (then again, neither is historical fiction). Subject headings are your friend: Frontier and pioneer life, West - History - Fiction, and Overland journeys to the Pacific are a few that would net results.

Despite its decline in popularity, there are a number of authors doing fresh and interesting work with the genre today, particularly for teens. They're helping to diversify the genre (Stacey Lee) and expand its definition (Moira Young). Genre crossover happens frequently, such as with Patricia C. Wrede's Frontier Magic series. Teens interested in stories about brave young women and men tackling dangerous situations, exploring unknown lands, and surviving on their own in a harsh setting would be interested in YA Westerns, though they may not know to ask for them specifically.

ResourcesThe Hub has a couple of good posts discussing YA Westerns, including reading lists.The Western Writers of America is an organization dedicated to promoting the literature of the American West, and their definition is expansive. They give out the Spur Awards annually, including one for juvenile fiction.Women Writing the West is an organization that promotes Westerns by and about women and girls. They also offer an award, the WILLA, that recognizes the best published stories each year about women and girls set in the American West, including a Children's/Young Adult category.The 2001 Popular Paperbacks committee selected 22 Westerns for teens.Historical Novels has a list of YA books set in the American Old West organized by topic. Most of these titles are older (early 2000s and before).BooksBelow are a few books published within the last five years, a few forthcoming titles, and a few that are a bit older but still circulate well among teens. I've also thrown in a few middle grade titles that may appeal to younger teens. Descriptions are from WorldCat and links lead to our reviews when applicable. Any we missed? Any diverse titles in particular to add to the list? Let us know in the comments.

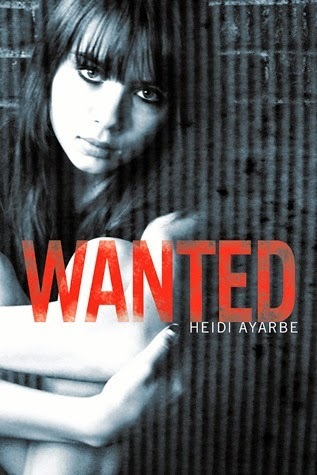

Wanted by Heidi Ayarbe

Seventeen-year-old Michal Garcia, a bookie at Carson City High School, raises the stakes in her illegal activities after she meets wealthy, risk-taking Josh Ellison.

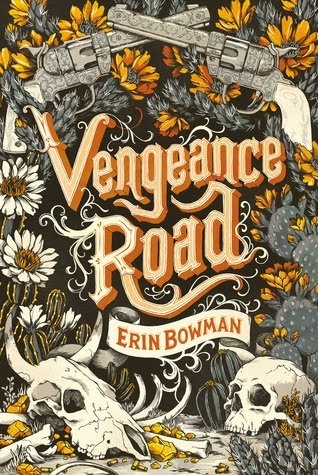

Vengeance Road by Erin Bowman (September 2015)

When her father is killed by the notorious Rose Riders for a mysterious journal that reveals the secret location of a gold mine, eighteen-year-old Kate Thompson disguises herself as a boy and takes to the gritty plains looking for answers--and justice.

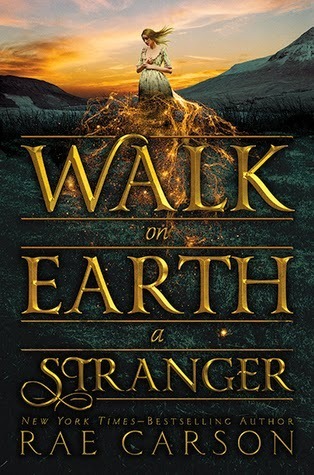

Walk on Earth a Stranger by Rae Carson (September 2015)

A young woman with the magical ability to sense the presence of gold must flee her home, taking her on a sweeping and dangerous journey across Gold Rush–era America.

Relic by Renee Collins

After a raging fire consumes her town and kills her parents, Maggie Davis is on her own to protect her younger sister and survive the best she can in the Colorado town of Burning Mesa. Working in a local saloon, Maggie befriends the spirited showgirl Adelaide and falls for the roguish cowboy Landon. But when she proves to have a particular skill at harnessing the relics' powers, Maggie is whisked away to the glamorous hacienda of Álvar Castilla, the wealthy young relic baron who runs Burning Mesa.

Nobody But Us by Kristin Halbrook

Told in their separate voices, eighteen-year-old Will who has aged out of foster care, and fifteen-year-old Zoe whose father beats her, set out for Las Vegas together, but their escape may prove more dangerous than what they left behind.

The Water Seeker by Kimberly Willis Holt

Traces the hard life, filled with losses, adversity, and adventure, of Amos, son of a trapper and dowser, from 1833 when his mother dies giving birth to him until 1859, when he has grown up and has a son of his own.

Grace and the Guiltless by Erin Johnson

When Grace's parents and siblings are murdered by the Guiltless Gang for their Arizona horse ranch outside Tombstone, she vows to devote her life to revenge--but the Chiricahua she finds sanctuary with try to teach her a better way.

Hattie Big Sky by Kirby Larson

After inheriting her uncle's homesteading claim in Montana, sixteen-year-old orphan Hattie Brooks travels from Iowa in 1917 to make a home for herself and encounters some unexpected problems related to the war being fought in Europe. | Sequel: Hattie Ever After

Under a Painted Sky by Stacey Lee

In 1845, Sammy, a Chinese American girl, and Annamae, an African American slave girl, disguise themselves as boys and travel on the Oregon Trail to California from Missouri. | Read Stacey Lee's guest post on friendship for our About the Girls series.

The Devil's Paintbox by Victoria McKernan

In 1865, fifteen-year-old Aiden and his thirteen-year-old sister Maddy, penniless orphans, leave drought-stricken Kansas on a wagon train hoping for a better life in Seattle, but find there are still many hardships to be faced.

The Last Summer of the Death Warriors by Francisco X. Stork

Seventeen-year-old Pancho is bent on avenging the senseless death of his sister, but after he meets D.Q, who is dying of cancer, and Marisol, one of D.Q.'s caregivers, both boys find their lives changed by their interactions.

How I Became a Ghost by Tim Tingle

A Choctaw boy tells the story of his tribe's removal from the only land its people had ever known, and how their journey to Oklahoma led him to become a ghost--one with the ability to help those he left behind.

Moon Over Manifest by Clare Vanderpool

Abilene Tucker feels abandoned. Her father has put her on a train, sending her off to live with an old friend for the summer while he works a railroad job. Armed only with a few possessions and her list of universals, Abilene jumps off the train in Manifest, Kansas, aiming to learn about the boy her father once was.

Thirteenth Child by Patricia C. Wrede

Eighteen-year-old Eff must finally get over believing she is bad luck and accept that her special training in Aphrikan magic, and being the twin of the seventh son of a seventh son, give her extraordinary power to combat magical creatures that threaten settlements on the western frontier. | Sequels: Across the Great Barrier, The Far West

Blood Red Road by Moira Young

In a distant future, eighteen-year-old Lugh is kidnapped, and while his twin sister Saba and nine-year-old Emmi are trailing him across bleak Sandsea they are captured too, and taken to brutal Hopetown, where Saba is forced to be a cage fighter until new friends help plan an escape. | Sequels: Rebel Heart, Raging Star

Related StoriesGet Genrefied: Alternate/Alternative FormatsOn The Radar: 12 YA Books For AprilMarch Debut YA Novels

Related StoriesGet Genrefied: Alternate/Alternative FormatsOn The Radar: 12 YA Books For AprilMarch Debut YA Novels

Published on April 06, 2015 22:00

April 5, 2015

On The Radar: 12 YA Books For April

One of the most popular posts I do over at Book Riot is the round-up of upcoming YA fiction titles, and one of the most popular questions I seem to get on Twitter and in my inboxes is "what should I be looking out for in YA?" For a lot of readers, especially those who work with teens either in classrooms or in libraries, knowing what's coming out ahead of time is valuable to get those books into readers' hands before they even ask.

Each month, I'll call out between 8 and 12 books coming out that should be on your radar. These include books by high-demand, well-known authors, as well as some up-and-coming and debut authors. They'll be across a variety of genres, including diverse titles and writers. Not all of the books will be ones that Kimberly or I have read, nor will all of them be titles that we're going to read and review. Rather, these are books that readers will be looking for and that have popped up regularly on social media, in advertising, in book mail, and so forth. It's part science and part arbitrary and a way to keep the answer to "what should I know about for this month?" quick, easy, and under $300 (doable for smaller library budgets especially).

For April, here are 12 YA titles to have on your radar. All descriptions are from WorldCat, and I've noted why it should be included.

Don't Stay Up Late by R. L. Stine (April 7): Ever since a car accident killed her father and gave her a severe concussion, high school junior Lisa's been plagued by nightmares and hallucinations, and when she accepts a babysitting job in hopes it will banish the disturbing images, she faces new terror as she begins to question exactly who--or what--she's babysitting.

Why: It's the second book in the relaunch of the "Fear Street" series. Here's some staple horror.

All The Rage by Courtney Summers (April 14): After being assaulted by the sheriff's son, Kellan Turner, Romy Grey was branded a liar and bullied by former friends, finding refuge only in the diner where she works outside of town, but when a girl with ties to both Romy and Kellan goes missing and news of him assulting another girl gets out, Romy must decide whether to speak out again or risk having more girls hurt.

Why: An important and powerful story about rape culture, victimization, and about the way we treat girls in society. Also, since it's the Tumblr Reblog Book Club's pick for April and May, it'll be really popular.

None of the Above by I. W. Gregorio (April 7): When Kristin Lattimer is voted homecoming queen, it seems like another piece of her ideal life has fallen into place. She's a champion hurdler with a full scholarship to college and she's madly in love with her boyfriend. In fact, she's decided that she's ready to take things to the next level with him.

But Kristin's first time isn't the perfect moment she's planned--something is very wrong. A visit to the doctor reveals the truth: Kristin is intersex, which means that though she outwardly looks like a girl, she has male chromosomes, not to mention boy "parts."

Dealing with her body is difficult enough, but when her diagnosis is leaked to the whole school, Kristin's entire identity is thrown into question. As her world unravels, can she come to terms with her new self? (Description via Goodreads).

Why: This story deals with an issue we don't see in YA: an intersex teen. This is written in an incredibly appealing way.

Eden West by Pete Hautman (April 14): Tackling faith, doubt, and transformation, National Book Award winner Pete Hautman explores a boy's unraveling allegiance to an insular cult. Twelve square miles of paradise, surrounded by an eight-foot-high chain-link fence: this is Nodd, the land of the Grace. It is all seventeen-year-old Jacob knows. Beyond the fence lies the World, a wicked, terrible place, doomed to destruction. When the Archangel Zerachiel descends from Heaven, only the Grace will be spared the horrors of the Apocalypse. But something is rotten in paradise. A wolf invades Nodd, slaughtering the Grace's sheep. A new boy arrives from outside, and his scorn and disdain threaten to tarnish Jacob's contentment. Then, while patrolling the borders of Nodd, Jacob meets Lynna, a girl from the adjoining ranch, who tempts him to sample the forbidden Worldly pleasures that lie beyond the fence. Jacob's faith, his devotion, and his grip on reality are tested as his feelings for Lynna blossom into something greater and the End Days grow ever closer. Eden West is the story of two worlds, two hearts, the power of faith, and the resilience of the human spirit.

Why: "National Book Award winner Pete Hautman" might be enough there, but it's worth noting this is a cult title, which is a popular trend in YA this year. Likewise, it explores faith and religion, and I know Kimberly found Hautman's last series -- The Klaatu Diskos -- extremely well done.

An Ember in the Ashes by Sabaa Tahir (April 28): Laia is a Scholar living under the iron-fisted rule of the Martial Empire. When her brother is arrested for treason, Laia goes undercover as a slave at the empire's greatest military academy in exchange for assistance from rebel Scholars who claim that they will help to save her brother from execution.

Why: There has been huge buzz around this title -- I've received more than one review copy of it, and I've seen plenty of rave reviews. It's a stand alone fantasy novel.

Lying Out Loud by Kody Keplinger (April 28): High school senior Sonny Ardmore is an accomplished liar who uses lies to try and control her out-of-control life which has been further complicated by the fact that she is secretly staying every night in her best friend Amy's house because she has been kicked out by her own mother--but when she gets into a online conversation with the stuck-up new boy Ryder, who has a crush on Amy, she finds herself caught up in one lie to many.

Why: This is a companion novel to The DUFF, and with The DUFF still being a New York Times Bestseller with renewed interest following the movie, this should garner some good interest. (Interesting to note it's a different publisher than The DUFF, though set in the same world and featuring different characters).

The Remedy by Suzanne Young (April 21): Seventeen-year-old Quinn provides closure to grieving families by taking on the short-term role of a deceased loved one, until huge secrets come to the surface about Quinn's own past.

Why: This is a novel set in the same world as Young's NYT Bestselling "The Program" series. It's a prequel, though reading the other titles isn't necessary to get this one. Young might be writing some of the best authentic teen dialog in YA.

Magonia by Maria Dahvana Headley (April 28): Aza Ray Boyle's life has been defined by a unique lung disease and her evolving friendship with Jason, but just before her sixteenth birthday, she is swept up into the sky-bound world of Magonia and discovers her true identity.

Why: A stand alone fantasy likened to Neil Gaiman. Early reviews and buzz on this have been really positive.

Simon Vs. The Homo Sapiens Agenda by Becky Albertalli (April 7): Sixteen-year-old, not-so-openly-gay Simon Spier is blackmailed into playing wingman for his classmate or else his sexual identity--and that of his pen pal--will be revealed.

Why: This is a fun read, featuring a gay main character.

Challenger Deep by Neal Shusterman (April 21): A teenage boy struggles with schizophrenia.

Why: This is Shusterman, so that's already the sell on the book, but it's a powerful, authentic, painful look at mental illness. The teen boy at the center of this one is also on the younger side of teen, which stood out to me when I read it.

Miss Mayhem by Rachel Hawkins (April 7): In the sequel to REBEL BELLE, Harper Price and her new boyfriend and oracle David Stark face new challenges as the powerful Ephors seek to claim David for their own.

Why: It's the sequel to Rebel Belle. Hawkins writes in a fun style, and she's extremely appealing to teen readers.

Palace of Lies by Margaret Peterson Haddox (April 7): After a terrible fire destroys her home and kills her twelve sister-princesses, Desmia must rise above those who intend to manipulate her and sieze power for themselves--and find out the truth.

Why: The third and final book in "The Palace Chronicles" series. These are especially good for the younger YA reading set.

Since I'm trying really hard to keep these lists to between 8 and 12 titles, I know I have to leave some really good stuff off. But if you have it in your budget to add one more title in April, I'd also put Amy Spalding's fun, funny, and romantic Kissing Ted Callahan (And Other Guys) in your cart.

Related StoriesOn The Radar: 13 Books for MarchMarch Debut YA NovelsWritten in the Stars by Aisha Saeed

Related StoriesOn The Radar: 13 Books for MarchMarch Debut YA NovelsWritten in the Stars by Aisha Saeed

Published on April 05, 2015 22:00

April 3, 2015

About The Girls Around The Web

Here's a round-up of some of the posts I've read over the last couple of weeks that fit into the question of "what about the girls?" Some have been sent to me and others came up in my own daily reading. I've also included a post I cowrote with Preeti Chhibber at Book Riot at the end, which gives practical things you can do to promote female writers you love, be they published authors or budding creators.

If you've written something that fits recently, feel free to link to it in the comments. I'm staying away from linking to reviews, but any thoughtful commentary, round-up, or responses are totally worth a share here. I'll let these do the talking for themselves:

Why I've Written A Funny, Feminist Novel 6 Female Illustrators Weigh in on Sexism, Feminism, and the Newsweek FiascoThe Nitty Gritty DetailsGirls ARE Interesting#StoryGirls Run the World: Celebrating Diverse GirlhoodsWomen Carving Out A Place For Themselves in Sci Fi (a response)Girls Behind Bars Tell Their Stories (I just finished Ross's book and it's so, so good. Get this for your collections. It's worth the price. Ross does this all on his own.)The Importance of Girls' Stories: An Interview with Nova Ren SumaTake part in Courtney Summers's #ToTheGirls campaign on April 14How to Support Rad Lady Authors

Related StoriesWhat About Intersectionality and Female Friendships in YA?: Guest Post by Brandy ColbertAbortion, Girls, Choice, and Agency: Guest Post by Tess SharpeOn (Not) Reading Science Fiction as a Teenage Girl

Related StoriesWhat About Intersectionality and Female Friendships in YA?: Guest Post by Brandy ColbertAbortion, Girls, Choice, and Agency: Guest Post by Tess SharpeOn (Not) Reading Science Fiction as a Teenage Girl

Published on April 03, 2015 22:00

April 2, 2015

Where Do We Go From Here? Wrapping Up "About The Girls"

Throughout the course of this series, as well as the on-going discussions of sexism in the YA -- and larger -- world, I've struggled with what it is I wanted to end "About the Girls" talking about. For a while, I thought doing a piece on mentoring would be worthwhile. How often are we seeing depictions of mentorships in YA fiction, where a teen girl has a solid grown-up female in her corner? There are some, but there certainly aren't a whole lot of them.

Then I wondered about how worthwhile it would be to talk about how we build those sorts of relationships with the teens in our lives. How can librarians, educators, and those who are advocates for teenagers arm girls with the knowledge and power to become strong, independent, vocal, and ready for what lies ahead? We can model, we can teach, and we can empower them by talking about our own experiences with adversity and how we stood up and kept fighting.

But what happens when we as adult females, those who have the ability to help mold and shape future girl leaders, are ourselves struggling with these very questions? If we ourselves are fighting with feeling inadequate, with feeling as though the battle is not worth continuing, with hitting wall after wall after wall, what sort of encouragement remains to share?

In the last month, I've received numerous threats. I've had incredible feminist friends and colleagues share with me similar stories, that they've received threats. In the midst of it, I've wondered about my role in all of this. Whether speaking up and using my voice is even worth it when I know there will be consequences for doing just that. For doing the thing I encourage other people to do in order to make any strides toward change. Just this week, a man took it upon himself to write a lengthy blog post talking about my choices, my decisions, my words, and my actions, calling for me to be fired from my job for simply ... doing my job.

I've struggled with a lot of fear over the last few weeks. Not just for myself. Not just for those friends and colleagues who've been supportive of me and who've told me what they're experiencing. I'm fearful that, no matter how many steps forward we do make, that the change we want to see won't happen. That, even when we are able to point to instances of sexism, our voices will still be summarily dismissed. Because we're female. But also because those we most want to change, the ones we point to as illuminating the problems, aren't going to be convinced to do so no matter how loud we shout and no matter how hard we fight. Those who are benefiting from the system don't want to step back and assess the privileges that allow them that power.

Yet, in dismantling that fear bit by bit, I've come to discover what's worth talking about and what's worth wrapping up this series with, and that's this: things can, do, and will change loudly and quietly, on the daily, in ways we see, and ways we won't.

This is how: for every one person who makes a sexist comment and is called out for it, more than one person is seeing that discussion and reassessing how they're talking. They're rethinking each word they're using when they type a comment on a blog post or they're reassessing what voices they're amplifying in their social spaces. They're stepping back and listening much more closely to women, to people of color, to those with disabilities, and anyone from a disadvantaged class of people.

The root of change, big and small, comes from people willing to listen, whether they're loud or not.

Those who are making changes, who are reconsidering their words and actions, aren't immediately quantifiable. Being a good ally comes in many forms.

As much as it's not fun to be called every name in the book, and as much as it's not fun to go into a discussion knowing that you're not going to change the minds of those arguing with you, perhaps it's easier to do so going in with the knowledge that change isn't always immediately visible and those who aren't actively speaking may still be affecting it in the ways they can.

Thousands and thousands of people read the "About the Girls" posts these last two weeks. They were shared hundreds of times. But there were only a few comments, comparatively. If a single post has 15 comments in one day, that looks great, especially when the comments are positive, thought-provoking, and encouraging. But when you know the post had over 7,000 hits in that same day, that 15 looks like a tiny number.

So what of those over 6,000 some readers that day?

They're being changed, too.

Whether they're capable of speaking up about it, whether they're capable of putting new thoughts into actions immediately, is something that's impossible to know. But it's not impossible to believe it. Perhaps some didn't speak out because of fear. Perhaps some don't speak up because they're sitting back and listening. Perhaps more are doing what it is I hope for when I put this series together: they're finally asking the question "what about the girls?" and inserting themselves and their experiences, their powers, and their understandings into being the sorts of mentors and role models that the younger girls in their lives so desperately need.

I'm still fearful when I speak up. I always hesitate when I call something out. There's almost always some sort of repercussion for doing so, most of which comes privately and in ways that aren't going to be out there for general consumption.

But when I speak up, I do so on behalf of those who don't, and I do so to show other girls, my contemporaries and those who are still growing, be they younger or older, that speaking up matters. That the act in and of itself is a powerful and empowering one.

Even if change isn't obvious.

Keep asking about the girls.

Keep wondering how we can do better so that they, too, can do better.

Related StoriesOn (Not) Reading Science Fiction as a Teenage GirlOn Curiosity: Guest Post by Jordan BrownStaking Our Claim in the Science Fiction Universe: Guest Post by Alexandra Duncan

Related StoriesOn (Not) Reading Science Fiction as a Teenage GirlOn Curiosity: Guest Post by Jordan BrownStaking Our Claim in the Science Fiction Universe: Guest Post by Alexandra Duncan

Published on April 02, 2015 22:00

April 1, 2015

On (Not) Reading Science Fiction as a Teenage Girl

About ten years ago, I was at the local Barnes and Noble, browsing the science fiction and fantasy aisle for a good book (or two or three). I was back in Texas, on break from college where I was studying English, and looking forward to diving into a book that was far from my assigned reading at UNC. Even if I didn’t end up buying anything (rare), simply being there next to all those books that promised so many terrific adventures felt like home.

Usually I browsed alone, sometimes camping out on the floor to read the first few pages of a likely candidate. This time, there was a man browsing the same aisle. He was about my age. He had brown hair and a beard. He made eye contact with me and I saw a surprised, but pleased, look overtake his face. I regretted making the eye contact (the absolute worst for a shy person) and wanted to just ignore him, but he must have felt the need for some sort of comment, because he told me he was surprised to see me browsing that aisle.

I was confused by the comment. We didn’t know each other. This was the aisle I always browsed when I shopped for books. I didn’t make any reply, just smiled thinly and continued shopping. I thought about telling him that I was looking for fantasy novels, which may have cleared up his confusion, but opted to just stay silent.

This is a small moment, but it’s one that’s stuck with me (and I have a notoriously sieve-like memory). I don’t remember when I first learned that science fiction was a boys’ arena, but it was something I had internalized from an early age, reinforced by small incidents like the one with the man at the bookstore who was surprised to see me shopping for SF.

This moment, and so many others, is why Alexandra Duncan’s guest post resonated so strongly for me, and it's why I wanted to write my own piece for our About the Girls series this year.

We all know that representation matters for readers. In my experience, this is especially true for teenagers. When I was a teen, I craved seeing myself in the books I read. I wanted to see girls on the covers, and I wanted them to be the focus. I wanted to put myself in their shoes and imagine that I was saving worlds, falling in love, and finding my power. I wanted to pilot a space ship and meet aliens. I wanted to get away from a life I often hated and pretend I could do incredible things. Furthermore, as someone who dreamed of being a writer when I grew up, I wanted to see books written by women. I wanted to know that there were other women out there writing the kind of stuff that I wanted to write.

With a few exceptions (Anne McCaffrey, basically), I didn’t find books like this in science fiction.

That’s not to say they weren’t there, as Maureen accurately points out. As an adult, this is easy for me to recognize. But the existence of women in SF – both as creators and as subjects – doesn’t necessarily make these books accessible, especially to teens who have limited resources to do research on their own. When I was a teenager, I found my books by browsing my library’s shelves and my bookstore’s shelves (usually a Barnes and Noble or a Half Price Books). I’ve always been interested in stories that are out of this world, that are heavy on the fantastic and the impossible. In both my library and the bookstores, these kinds of stories were found in the combined Science Fiction and Fantasy section. The science fiction authors I found there were overwhelmingly male: Isaac Asimov, Orson Scott Card, Piers Anthony, Ben Bova, Frank Herbert. Their covers and their stories featured men and the synopses on the back had little relevance to my life. When women were on the covers, they were often not wearing much or kneeling at the foot of a man or dead. I found the women in the fantasy novels: Juliet Marillier, J. V. Jones, Anne Bishop, Elizabeth Haydon, Sara Douglass. I began to recognize a science fiction novel by its cover, which usually had a black background and blocky lettering. Those I would quickly bypass in search of something more likely to include someone like myself.

Getting past the easy reach is, well, not easy. For most people, myself included at that age, it’s not even something that would cross their minds. What is on the shelf is what exists. If it’s not there? It functionally does not exist for the reader looking for it. Thus I came to believe that science fiction was not for me. Science fiction was for boys, and they knew it, too. Of course, books by and about men are also for women, and I read a lot of them, but when I realized over and over again that I would never see myself in these books, that the girls and women who were in these books were always portrayed via the male gaze, I mostly gave up on them. I would tell people I preferred fantasy over science fiction. It became my primary love and the genre in which almost all of my own fictional scribblings at this time belonged.

What I came to realize much later is that I preferred fantasy to the science fiction I could find, not necessarily the science fiction that existed. While I don’t absolutely love The Hunger Games, I am so glad for its stratospheric popularity, for much the same reason Duncan mentions. It, and its legions of dystopian and post-apocalyptic readalikes, made science fiction by and about women much more visible to people like teen me, who only saw what the booksellers and the librarians chose to buy. YA science fiction helped bring me to the genre I had always wanted to love, if only it would love me back.

Since reading The Hunger Games, I’ve become much more cognizant of what SF is actually out there, how certain books are marketed, and the inherent biases in people’s reading choices. That’s due to my professional life as a librarian, which has led to an effort on my part to get beyond the easy reach – for the benefit of myself as well as my patrons. It’s easier for me to find both hard and soft SF about girls when I want it because I have the tools to do so. But if my professional life hadn’t given me those tools? It would be a lot harder. I wouldn’t have known that so many great books even existed.

I’m reminded of a conversation I had as a teen with a black girl around my age who was volunteering at the library alongside me. We were talking books and reading and I mentioned that I loved historical fiction. She told me she didn’t really care for it, and I was so surprised. I loved historical fiction so much I just figured its appeal was universal. I told my mom later on that my friend said she didn’t like historical fiction, and my mom’s reply was that it might be due to the fact that there’s not much historical fiction about black girls. I was dumbstruck, having never thought about that before. I have no idea if this is the real reason she didn’t care for it. I’ve since learned that quite a lot of people don’t like historical fiction simply because they think it’s boring (sacrilege!). But I wouldn’t be surprised if it were.

Visibility matters. You can talk about books by women writers and writers of color and LGBTQ writers until you’re blue in the face, but if none of their books make it to library or bookstore shelves, most people – especially teens – aren’t going to read them. The mega success of books like The Hunger Games, their ubiquity, tells girls they belong in science fiction – reading it, writing it, imagining it.

So let's continue to remind people that women have always been a part of science fiction - all kinds of it. But let's also remember how privileged it is to know this history and be aware of these books when they're not on endcaps at bookstores. And let's continue to work to fix that.

Related StoriesOn Curiosity: Guest Post by Jordan BrownStaking Our Claim in the Science Fiction Universe: Guest Post by Alexandra DuncanWhat About Intersectionality and Female Friendships in YA?: Guest Post by Brandy Colbert

Related StoriesOn Curiosity: Guest Post by Jordan BrownStaking Our Claim in the Science Fiction Universe: Guest Post by Alexandra DuncanWhat About Intersectionality and Female Friendships in YA?: Guest Post by Brandy Colbert

Published on April 01, 2015 22:00

March 31, 2015

On Curiosity: Guest Post by Jordan Brown

To round out the guest posts for this year's "About The Girls" series, I've asked editor Jordan Brown to share some thoughts. I won't preface this with more than that because his post is powerful.

Jordan Brown is an executive editor for Walden Pond Press and Balzer + Bray, both imprints of HarperCollins Children’s Books. Recent releases he’s edited include Laura Ruby’s Bone Gap, Mindee Arnett’s Polaris, Chris Rylander’s Countdown Zero, and Gris Grimly’s illustrated version of A Study In Scarlet. He lives in Brooklyn.

I’m honored and humbled to be included in this series of blog posts—even more so as I’ve been reading the previous entries by this brilliant group of women. Some of their words even helped me to form this post, in which I’d like to talk about a couple incidents that have divided the community of children’s book folks in the last month.

You may have seen a recent series of blog posts and tweets by the author Shannon Hale. If you haven’t, please take a moment to look at these two excerpts:

http://oinks.squeetus.com/2015/02/no-boys-allowed-school-visits-as-a-woman-writer.html

https://twitter.com/haleshannon/status/580817335449034752

The posts are recent, but the issue is hardly new; this is not the first time that concern for young boy readers has been offered up as a reason for removing women writers, and books about women, from their presence. Talk to a dozen women writers and you will get a dozen such stories.

I probably don’t have to explain to you that there is not a single element in Shannon Hale’s books—biological, social, intellectual, emotional—that eschews male participation, unless you simply believe that books about girls written by women are automatically of zero interest to a young boy and have zero value to his development. Which, apparently, many people do. While girls are generally free to read whatever books they’d like without fear of shame or ridicule, boys are often cut off, in one way or another, from the thoughts, feelings, and experiences of half the planet’s population, at least as far as reading material goes. I know this because it was not long ago that I would spout accepted wisdom about “boy books” vs “girl books”, discussing with publishing colleagues the idea that girls will read anything while it’s difficult to get boys to pick up a book featuring a girl protagonist—as if this profound incuriosity about girls were a part of a young boy’s genetic makeup, and not something ingrained in him by adults that constantly remind him that thinking about the interior lives of girls runs counter to everything that defines boys and men in our culture.

Now, I don’t necessarily think there’s anything wrong, intrinsically, with talking about gender and reading. I think it’s important that we think specifically about what values and modes of thought we want to encourage in our young people; and in a culture dominated by gender paradigms and prescription, I will agree with those who say that instilling in them those sorts of values and thoughts can require different approaches based on gender. I am the proud editor of Jon Scieszka’s Guys Read short story anthology series, after all. And I also don’t think there’s anything wrong with a large portion of a boy’s reading material including stories that feature boys as primary characters and model and address answers to their emerging questions about themselves. My problem arrives when those ideas about gendered books bring with them the same troubling paradigms and prescriptions I mentioned—specifically the reductive idea that unless a book includes boys in the most dynamically-developed roles, is concerned primarily with traditional presentations of those characters’ thoughts and feelings, and is more often than not written by a man (especially if it is less than thirty years old), then it is not meant for them; and that we need to help boys avoid situations in which they are exposed to literature by women that concerns what girls think, feel, and experience. This, of course, is rarely something that is actively stated or spoken aloud, but it need not be: it’s present in how books are marketed and sold and reviewed, how panels at conferences are planned and populated, etc. For a business that puts such a premium on encouraging the curiosity and creativity of young people, this is a particularly troubling instance of us all falling asleep at the wheel.

The problem with the deeply sexist attitudes that Hale and other women writers battle with daily is that they are bred not of active bias, but of good intentions mixed with passive acceptance of the dominant narrative I mentioned above. Many smart people who work more directly with children than I do will agree that boys sometimes take to reading more reluctantly than girls, and thus require literature that speaks to their experience of the world in order to more directly foster enjoyment in the act of reading. This is something that many boys already carry with them as they enter their educational years, and it’s left to teachers and media specialists to address. But this endeavor—fostering enjoyment in the act of reading—seems to be the primary motivation that allows some people to deprioritize the development of an interest in what girls think and feel in boys at this age. In any case, the message has been received: there is certainly no dearth of bestselling, critically acclaimed, and award-winning reading material for boys of all ages involving traditionally “male” content, and generations of young boys are not only allowed to exclusively read books featuring a distinctly male point of view, but are actively and passively prevented from reading anything else. In Shannon Hale’s case, this means that they are not allowed to be in the room with her while she talks about an adventurer using cunning and skill to battle monsters, because that adventurer happens to be a princess.

When she posted her essay, Hale got some truly horrid responses. The majority of disagreements with her and other writers who choose to speak out are not all quite as ill-conceived as this one, but they tend to imply something similar: the problem isn’t with society, or with the message we’re sending to boys, but rather with the women writers themselves who presume to feel slighted by the natural order of things. I’m a man, and so my tweets about Hale's experience didn’t produce such vitriolic responses directly into my mentions, but the one negative response to my assertion that her blog post is “the most important thing you’ll read today” was “Hope not.”

“Hope not.” If I may extrapolate: how depressing it would be for the responder if this frivolous issue were not eventually put out of mind by something more worthy of his attention. This was not an aggressive response at all—it was simply one in line with the general idea that an objection to this sort of line-drawing where gender is concerned is much ado about nothing, and ought to be dismissed to deal with issues more pressing about boys and their development. This assertion carries with it the idea that not only are these women authors self-obsessed, but they don’t have the best interests of the kids they claim to be writing for at heart—a point raised by Hale’s responder above. To him, it’s a failure of empathy on her part that she thinks boys might want to read about a girl. Sit with that for a moment.

Of course, this isn’t the only time in the last month that we’ve seen this sort of hostile response to female writers’ objections to sexism. I’m not going to talk in detail about Andrew Smith’s words when he responded to his interviewer’s question about the lack of multi-dimensional female characters in his books, nor the overall character of the defense of his words; writers much smarter and more eloquent than I have covered this. I bring it up because I believe it ties into this conversation about curiosity. Smith implied that he believed he was constitutionally and experientially unable to understand the interior lives of women, and didn’t feel it necessary to attempt to do so until recently—and while I agree with those who say that Smith didn’t intend any harm with these words, his response seems directly in line with what we’ve been discussing here today. More than this, a particularly troubling strain of the defense of what he said—exemplified by this blog post—suggests that one need not even listen to a thoughtful and earnest analysis of sexism by a woman with a degree in gender studies, as it can be nullified by, for instance, the opinion of someone whose point of reference for sexism is a dictionary entry. This seems to me to be the result of practices like what Hale describes: a life lived in a world where men are actively discouraged from listening to women. And it has manifested itself in a culture in which, in so many unfortunate cases, we find ways (often inadvertently, I’d like to believe) to silence those women when any of them presume that their own personal experience with sexism in our business might be relevant to the conversation.

The truth is that this is a desperately important issue. We hear how difficult it can be for women to speak out when dealing with experiences of body dysmorphia, internet harassment, physical abuse, sexual assault, etc—and we see, again and again, that so many of the men in their lives feel no responsibility to simply trust their words. So many of us mitigate women’s pain, deny women’s experience, and believe it is our place to do so—that these are situations where our perspective is needed to bring necessary objectivity to the conversation. It’s difficult for me to not draw a straight line between the attitudes of those who presume to inform a women what sexism is or isn’t and the attitudes of those who presume to inform them about what rape is, or what domestic violence is, or what a women’s rights are. All of them stem from a belief that a man’s experience alone is enough to evaluate and judge that of a woman. And why wouldn’t it be? Male experiences are all we’ve ever been taught are worth our time and attention.

For the record, I don’t believe that anyone from our community involved in this conversation truly thinks that sexism and the other issues mentioned above are fabrications, or don’t need be addressed when they arise. But I do believe that a culture in which boys are not expected to pay attention to girls during their formative years can lead to men who have an impaired sense of judgment when more subtle, complex, pernicious, or insidious instances of systemic sexism do come along. I know this because, until relatively recently, I was one of these men—one who presumed himself to be thoughtful, intelligent, and empathetic enough to believe that if I wasn’t personally offended by an instance of sexism or racism, or had what I thought was a perfectly legitimate reason to mitigate it, then it probably didn’t exist, or at the very least was being blown out of proportion by those people discussing it, who obviously couldn’t see the big picture as objectively as I could.

What changed for me, then? It’s funny—of the endless forks in the recent path of conversation about sexism and publishing and the internet, the one that bums me out the most is the conversation about outrage culture, and the fact that nothing meaningful can happen online. Because it’s on Twitter, on blogs, on various internet platforms, that I was exposed daily to the thoughts, feelings, and perspectives of intelligent people who don’t look anything like me—and it’s here that I learned to listen to them. The internet allows the perspectives of people who are traditionally marginalized in our culture to coalesce, to build off of one another, in ways that were rarely possible before. It’s here that I could see patterns emerge where before I only saw disconnected incidents. I learned when it was appropriate to shut the hell up and listen, and heard so many perspectives different from mine that it eventually became an act of profound ignorance and naiveté to continue to think that my opinion could be informed when it took no one’s experience into account but my own. I learned that there are dozens of people right here in our community—people like Shannon Hale, Gayle Forman, Justina Ireland, Ellen Oh, Liz Burns, Brandy Colbert, Sarah McCarry, Amanda Nelson, Tess Sharpe, Marieke Nijkamp, Ilene Wong, Angie Manfredi, Roxane Gay, Courtney Summers, Kelly Jensen, Leila Roy, Melissa Posten, and many, many others—who could speak loudly and powerfully about female experiences in ways I didn’t understand previously. And I could see men—Mike Jung, Daniel José Older, Saladin Ahmed, Andrew Karre, and many more—be unafraid to tweet and retweet with an interest, understanding, and curiosity for those same experiences, to be able to add their voice and perspective to the conversation in ways that recognize and respect them (including those moments when their voices simply aren’t needed). I’d been a reader my whole life, but it was on the internet that I recognized in a way I never had before that reading, at its heart, is about listening.

One has to be curious in order to listen. Children’s and YA lit represents the bulk of the books actively contributing to the formation of a child’s values, and, where middle grade is concerned, the majority of the books that end up in a child’s hands are, on some level, prescribed by adults. This is a desperately important time to be cultivating a curiosity in young people about others’ experiences, and we’re not going to be able to do that properly if we remain entrenched in the same ideas about “boy books” and “girl books” that we’ve been working with up to this point. Books can be powerful tools for change in this respect—to teach young boys and girls to look outside themselves, to frame empathy as a trait not reserved for girls but as an important part of being a boy as well. The way in which we talk about gender with regard to books for kids and teens is certainly not the sole problem here, no more than any other aspect of American culture—but unlike those other aspects, we are in a unique position to be a part of the solution. The choices that writers, publishing professionals, booksellers, educators, reviewers, etc make with regard to framing gender can have a profound impact on these issues. Because books are one place where smart, kind, passionate men whose life experiences have simply prevented them from connecting with the perspectives of women can find that connection.

But first, we need to let them in the room.

Related StoriesStaking Our Claim in the Science Fiction Universe: Guest Post by Alexandra DuncanWhat About Intersectionality and Female Friendships in YA?: Guest Post by Brandy ColbertAbortion, Girls, Choice, and Agency: Guest Post by Tess Sharpe

Related StoriesStaking Our Claim in the Science Fiction Universe: Guest Post by Alexandra DuncanWhat About Intersectionality and Female Friendships in YA?: Guest Post by Brandy ColbertAbortion, Girls, Choice, and Agency: Guest Post by Tess Sharpe

Published on March 31, 2015 22:00

March 30, 2015

Staking Our Claim in the Science Fiction Universe: Guest Post by Alexandra Duncan

Today, Alexandra Duncan is taking part in the series to talk about females in science fiction and why it is we belong in it.

Alexandra Duncan is an author and librarian. Her YA sci-fi novel Salvage (2014) was a 2014 Andre Norton Award nominee and a 2015 Amelia Bloomer Project selection. Its companion novel, Sound, is forthcoming in September 2015. Her short fiction has appeared in several Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy anthologies and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. She lives with her husband and two monstrous, furry cats in the mountains of Western North Carolina.

When you think of “girly” books, chances are, you’re not thinking about science fiction. Sci-fi, along with horror and other “weird” fiction, has long been male territory, where women are the exception. I learned this lesson over and over again as a teenager searching for sci-fi written by or starring women. Not that I didn’t get any pleasure from Robert Heinlein’s “boys” novels, for example, or gain insight about issues like poverty (Citizen of the Galaxy) or self-determination (Farmer in the Sky), but there was a special kind of excitement in finding a sci-fi novel with a female protagonist. After all, even Ursula Le Guin, who inspired me and whose books I loved dearly, often wrote about men.

The big boom in young adult literature came right after I graduated from college. Suddenly, here were all the books I had been desperate to read as a teenager, when my YA reading choices were limited to Sweet Valley High (too fluffy and formulaic), John Knowles’s A Separate Peace (good, but about rich boys courting tragedy at boarding school), and I Know What You Did Last Summer (the best of the bunch). Now I could read about kick-ass young women with magical powers and girls doing everything I had dreamed of as a teen. But the sci-fi pickings were still fairly slim. I loved fantasy, too, and now there was plenty of it, but where were the spaceships? Where were the girls surviving on hostile planets, like Rod Walker in Heinlein’s Tunnel in the Sky?

I had come across Anne McCaffrey’s Crystal Singer, about a young woman sent to a planet to help mine crystals by singing, at a used book store in high school. I wanted so desperately to finish reading the trilogy, but my small-town public library didn’t have the other two books, and the internet hadn’t quite caught on in rural North Carolina at that point, so I couldn’t track them down. Every time I went to a used book store for the next five years, I checked for the rest of the Crystal Singer series, with no luck. I’m sure there were other sci-fi books by and about women out there, but they were so few and far between, the chances of them making their way into my orbit were slim to none. Like many girls and women, I was making do with glimmers of what could be, like the scene in Return of the Jedi where Leia disguises herself as a bounty hunter and tries to rescue Han (before she ends up chained and in a bikini).

I had come across Anne McCaffrey’s Crystal Singer, about a young woman sent to a planet to help mine crystals by singing, at a used book store in high school. I wanted so desperately to finish reading the trilogy, but my small-town public library didn’t have the other two books, and the internet hadn’t quite caught on in rural North Carolina at that point, so I couldn’t track them down. Every time I went to a used book store for the next five years, I checked for the rest of the Crystal Singer series, with no luck. I’m sure there were other sci-fi books by and about women out there, but they were so few and far between, the chances of them making their way into my orbit were slim to none. Like many girls and women, I was making do with glimmers of what could be, like the scene in Return of the Jedi where Leia disguises herself as a bounty hunter and tries to rescue Han (before she ends up chained and in a bikini). Enter The Hunger Games. I was working at a book store at the time and managed to snag an ARC before the first book came out. I read the whole thing in one sitting, incredibly moved and energized. I felt like Molly Grue in Peter S. Beagle’s The Last Unicorn when she comes across the title character for the very first time and bursts into tears, shouting, “Where have you been?” Where had books like this been when I was a teenager? Why had it waited to show up until I was at an age where I was “supposed” to be reading adult books? But like Molly Grue, what was ultimately important to me was that it was here now. I didn’t know it yet, but The Hunger Games was about to usher in a tidal wave of dystopian fiction. It was going to lead all of its fellows out of the sea.

Some people don’t think of dystopian fiction, which women are writing in staggering numbers, as part of science fiction. I have to disagree. When you have genetically modified monsters running around a reconstructed post-apocalyptic North America with advanced technology and striking class divisions, you’ve got sci-fi. Others refer to dystopian novels dismissively as “soft” science fiction, as if books that deal with bio-ethical or sociological issues are not “real” science fiction. “Real” sci-fi is “hard” sci-fi, and it belongs to men.

Of course, this is a fallacy, too. Women have staked out territory in all areas of sci-fi in recent years. Beth Revis’s Across the Universe trilogy has made major inroads in introducing female YA readers to harder science fiction. Marissa Meyer has given us a cyborg Cinderella in her Lunar Chronicles series. Lauren DeStefano has deftly intertwined genetics and feminist issues in her Chemical Gardens trilogy. And the international writing team of Amie Kaufmann and Meagan Spooner has shown us through their Starbound series that all kinds of girls are welcome in the science fiction universe, both kick-ass soldiers and those whose appreciation of a nice ball gown doesn’t change the fact that they are whip-smart survivors.

Of course, this is a fallacy, too. Women have staked out territory in all areas of sci-fi in recent years. Beth Revis’s Across the Universe trilogy has made major inroads in introducing female YA readers to harder science fiction. Marissa Meyer has given us a cyborg Cinderella in her Lunar Chronicles series. Lauren DeStefano has deftly intertwined genetics and feminist issues in her Chemical Gardens trilogy. And the international writing team of Amie Kaufmann and Meagan Spooner has shown us through their Starbound series that all kinds of girls are welcome in the science fiction universe, both kick-ass soldiers and those whose appreciation of a nice ball gown doesn’t change the fact that they are whip-smart survivors.The fundamental trouble here, though, is the false dichotomy set up between hard and soft science fiction. Why do we think we can’t have our space ships and explosions together with our explorations of the ethics of cloning or ruminations on the ways alien cultures might view sexuality differently from our own? Why do some people think of “soft” sci-fi as somehow lesser? Many women, myself included, write soft science fiction because sociological issues like cultural bias, discrimination, and abuse materially affect our lives. Authors like Nnedi Okorafor, who writes both YA and adult novels, Mary E. Pearson, and Alaya Dawn Johnson deftly bring social issues into focus under a science-fictional lens, and the result is dazzling.

In actuality, science fiction is the perfect arena for exploring sociological issues, because the genre has long taken on hot topics and attempted to reframe them in a way that might help us view our own world differently. We can take a fresh look at race, class, or terrorism without the baggage we have when reading the news, then return to those real-world issues with a fresher, deeper understanding. Women like the ones I’ve mentioned have proved they are not afraid to do this. In fact, they excel at this, one of the most fundamental values underpinning science fiction writing.

Women carving out a space for themselves in science fiction is changing the face of the genre, and changing it for the better. It is broadening and deepening the conversations we have in science fiction. If we keep reading and writing, who knows what brave new worlds we’ll discover next?

***

Salvage is available now. The companion, Sound, will be available September 22.

Related StoriesWhat About Intersectionality and Female Friendships in YA?: Guest Post by Brandy ColbertAbortion, Girls, Choice, and Agency: Guest Post by Tess SharpeOn Being a Feminist YA Author and Daring to Write “Unlikable”: Guest Post by Amy Reed

Related StoriesWhat About Intersectionality and Female Friendships in YA?: Guest Post by Brandy ColbertAbortion, Girls, Choice, and Agency: Guest Post by Tess SharpeOn Being a Feminist YA Author and Daring to Write “Unlikable”: Guest Post by Amy Reed

Published on March 30, 2015 22:00

March 29, 2015

What About Intersectionality and Female Friendships in YA?: Guest Post by Brandy Colbert

To kick off the second week of "About the Girls" guest posts, Brandy Colbert is here to talk about friendship in YA. More specifically, she's here to talk about how important it is to see diverse, intersectional friendships in YA between and among girls.

Brandy Colbert is the author of Pointe, which was named a best book of 2014 by Publishers Weekly, BuzzFeed, Book Riot, the Chicago Public Library, and the Los Angeles Public Library. Her second novel, Little & Lion, is forthcoming from Little, Brown Books for Young Readers. She lives and writes in Los Angeles, and you can find her on Tumblr, Twitter, and brandycolbert.com.

When I was in first grade, I was part of a trio of friends that included two girls we’ll call S and K. They were both small and white and blond, and K was born with two fingers on one of her hands. We’d all hold hands as we walked around the school and playground, as little kids do, but I remember the first time I noticed K’s hand. I went home that day and asked my parents about it. At the time, she was one of the first people I’d ever met with a physical disability, and especially who happened to be my age. Without missing a beat, they calmly informed me that K’s hand didn’t define her, that we’re all different in some way, and to never believe I’m better than (or not as good as) anyone else because of those differences.

That talk has stuck with me nearly thirty years later, and it was incredibly timely in my childhood. The next year our family moved across town where as a second-grader, I was one of only a handful of black kids in my entire elementary school. I grew up in a town that was predominantly white and only 3 percent black, but the school I’d attended with K and S was quite racially diverse, all things considered. Suddenly I knew what it was like to be the one who was “different.”

I lost track of K over the years, but I’ve always wondered if she dealt with similar issues I had growing up: Namely, always having to explain myself. For me, it was: Why does your hair look/feel/stick out like that? Can you actually get sunburned? Would I be able to see it if you blushed? And then there were the not-so-subtle looks (and sometimes pointed questions) during the slavery discussions in history class. And let’s not forget the girl who, at my part-time job, pulled me aside to ask if both of my parents were black…and only admitted she broached the topic because of the way I speak after I prompted her.

Despite how exhausting and demoralizing it can be to not only have to explain your differences and feel like the spokesperson for black America before the age of ten, part of me appreciates those questions, looking back. Plenty were mean-spirited, meant only to remind me of how I’d never truly fit in among my peers. But some were thoughtful; some people truly wanted to learn, and if I could help them understand why and how a person different than them might go through a separate set of challenges and experiences in their lives, it was worth my time and effort.

Because of where I grew up, the majority of my friends were white until I moved away from southwest Missouri. Which meant these conversations took place anywhere and any time, but most often with my white female friends. I spent the most time with them, after all—at the dance studio after school and on weekends, at sleepovers, on the dance team in high school, talking on the phone for hours upon hours. I still have several white women friends as an adult, and I was surprised I didn’t know the term intersectional feminism until embarrassingly recently. I can’t remember where I first heard it, but social media came into play. I knew that I didn’t always feel like the feminism my white friends talked about and promoted was totally inclusive, but to hear there was an actual term for it felt so validating. What I’d been thinking and going through all these years wasn’t in my head.

The concept of intersectional feminism has been around and discussed for many decades, but law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw, a black woman, is credited as being the first person to coin the term in 1989, which is loosely defined as recognizing that women experience different layers of oppression, including race, class, gender, ethnicity, and ability.

So, in other words, the reasons my white female friends didn’t seem to quite get what I was going through was because most of their experiences were colored through the experience of being a white woman. Full stop. Race and ethnicity weren’t an issue for them, and typically class and ability weren’t, either.

I remember sitting in my therapist’s office in Chicago several years ago when she asked, “How do you define yourself?” I looked at her, confused, and she said, “If someone asked you to define all the things you are, what would you say and in what order?” It didn’t take long for me to reply: “Black. Woman. Writer.” To me, I am all of those equally, but I know society doesn’t always see or treat me that way.

My childhood friends and I were avid readers, trading paperbacks and poring over the Scholastic catalog together. Now, even in 2015, children’s publishing has a diversity problem. But this was back in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and so nearly 100 percent of the books I read were about white, straight, able-bodied kids. I didn’t think to question it; I yearned to read about kids who looked like me, but if I hadn’t read the books that were out there, I wouldn’t have read anything at all. I started writing fiction when I was seven years old, and even my own books at the time featured exclusively white characters because I just assumed people didn’t publish contemporary books about black kids.

One thing I’d like to see more of in children’s literature—particularly young adult fiction—is friendships between girls from different backgrounds. I want to see white, middle-class girls who have friends other than other white, middle-class girls. I want books where marginalized people aren’t presented as token best friends or love interests, but rather fully fleshed-out characters with their own stories and hopes and desires. I want to see books that show microaggressions and how those can build up and eat away at a person over time, how telling someone “It’s just a joke” isn’t helpful when those “jokes” are thrown at them day in and day out. I want to see characters who are black and Latina and Native American and Asian and biracial and white have friends with disabilities, and lesbian and bisexual and transgender friends. I want to see different combinations of those friendships and I’d especially like to see books where girls fit into more than one of these categories themselves.

I want to see these girls supporting and understanding each other’s differences—or listening and trying to understand if they don’t already. Because while I may have felt the time and effort of explaining myself to people in the past was worth it, all that explaining is exhausting the older you get. You still feel like the spokesperson for your group, even if you know you’re relaying a singular experience. And besides that, as an adult, you wonder why other adults aren’t seeking out other sources to educate themselves. Books are a wonderful way into different lives and worlds, so I can’t stress enough how much we need to see more novels published that focus on marginalized characters.

But while I was thinking of this magical wish list, it occurred to me that perhaps I missed an opportunity to delve into intersectional feminism in my own book.

In Pointe, the protagonist, Theo, is black American and grows up in a place not unlike my own hometown, in that it is suburban and almost entirely white. She’s known Ruthie, one of her oldest and closest friends at her dance studio, since they were toddlers, and they are both on the professional ballet track, ready to audition for summer intensives. Throughout the book, Theo and Ruthie speak honestly about their lives, but looking back, I wonder if their friendship could have been even more realistic if I’d included a conversation about the struggles of black ballet dancers. Theo herself acknowledges how difficult the journey could be for her, what with the lack of black dancers in the professional ballet world. And on some level, she is aware that Ruthie likely stands a greater chance of success than her—even though they are equally talented—simply based on her skin color. Would the book have been improved with a scene where they acknowledged these differences? I don’t know. Writers are always thinking, and I don’t believe we’re necessarily ready to write about what we’re currently pondering. But I’d like to think I’ll be more conscious of portraying certain experiences from here on out, and work to include even more examples that are authentic to my main characters’ worlds.

Naturally this whole topic got me thinking about what’s already out there in YA fiction in terms of portraying female best friends with different backgrounds. Not surprisingly, I came up short in what I’ve read that fits the bill. Although, how I loved the friendship in Sarah McCarry’s gorgeous novel Dirty Wings, between Maia, who’s Vietnamese and adopted by a white family, and her best friend, Cass, who is white. In Nina LaCour’s Everything Leads to You, Emi, the protagonist, is a lesbian; I can’t recall if the sexuality of her best friend, Charlotte, was ever mentioned, and don’t want to assume that she is straight because of that. But this novel was one of the first that I’d read with a lesbian protagonist in which her sexuality was not an issue, yet we still saw Emi’s romantic struggles with girls, and the easy way she was able to confide in Charlotte.

One of the most wonderfully diverse books I’ve read in some time is Maurene Goo’s Since You Asked…, whose main character, Holly, is of Korean-American descent, and whose best girl friends, Elizabeth and Carrie, are Persian and white. Not only was it so refreshing to read about how they celebrate and share in the varying aspects of their cultures, but Goo managed to effortlessly encapsulate the racially and ethnically blended lives of Southern California teens.

I’m very much looking forward to Under a Painted Sky by Stacey Lee, which was just released in March and features a Chinese girl and a black girl making their way West on the Oregon Trail. And when I asked my lovely host Kelly for more books I might have missed, she suggested Swati Avasthi’s Chasing Shadows and Hannah Moskowitz’s Not Otherwise Specified—neither of which I’ve yet read, but both have been on my radar.

The truth is, it’s really damn hard to be a girl in this world, and I’m grateful for the ones who’ve taken the time to understand me, who listen when I speak about challenges they may never face. I’m thankful to have met someone so early in life, my old friend K, who helped me recognize the struggles someone different from me is dealing with. I’m here for girls of all kind, and I hope young adult fiction starts to reflect more of that idea in the future.

Do you have more suggestions for books that fit my wish list? Leave them in the comments or tweet me @brandycolbert!

***

Pointe is available now.

Related StoriesAbortion, Girls, Choice, and Agency: Guest Post by Tess SharpeOn Being a Feminist YA Author and Daring to Write “Unlikable”: Guest Post by Amy ReedWhy Friendship Books Are Essential: Guest Post by Stacey Lee

Related StoriesAbortion, Girls, Choice, and Agency: Guest Post by Tess SharpeOn Being a Feminist YA Author and Daring to Write “Unlikable”: Guest Post by Amy ReedWhy Friendship Books Are Essential: Guest Post by Stacey Lee

Published on March 29, 2015 22:00

March 26, 2015

Abortion, Girls, Choice, and Agency: Guest Post by Tess Sharpe

Today's guest post comes from author Tess Sharpe and it takes a keen look at the messages and insights YA books that explore abortion offer. Where it's been said abortion is the last taboo of YA fiction, perhaps that's not really the case. Rather, there's still a lot of room for exploration.

Born in a backwoods cabin to a pair of punk rockers, Tess Sharpe grew up in rural northern California. She is the author of FAR FROM YOU and SOMEWHERE BETWEEN RIGHT AND WRONG (out Fall 2016). She lives, writes, and bakes near the Oregon border.

Born in a backwoods cabin to a pair of punk rockers, Tess Sharpe grew up in rural northern California. She is the author of FAR FROM YOU and SOMEWHERE BETWEEN RIGHT AND WRONG (out Fall 2016). She lives, writes, and bakes near the Oregon border.

When I was a little girl, my father volunteered as an escort at our local abortion clinic. “Escort” is the nice way of saying “bodyguard” or “human shield.” They lead the women into the clinic, putting their bodies between the women and the protestors, just in case. But they can’t block out the garish signs, the accusations of baby killer and whore or the God loves yous. They can’t hide the women from the protestors—who might be friends, family members, neighbors, or fellow church members.

In the ’90s (and now), my conservative small town was one of the few places you could get an abortion, and escorting—like working or volunteering there—was (and still is) dangerous work. One day, there was a knock at our door, and one of the protestors was standing there on our porch, wanting to “invite” my father and our family to church. The message was clear: we know where you live.

There was reason to fear: By the time I was a teenager, the clinic had been firebombed five times, and has been destroyed, totally flattened, twice.

When I was in college, the fear got personal: My only sister now ran that clinic, and would do so for a decade. I once asked her to carry pepper spray. She just shrugged and said pepper spray wasn’t going to help her against a bomb or bullets.

Fighting for reproductive freedom and bodily autonomy runs in the veins of all the women in my family. Which is why, when Kelly asked me to write a post for Women’s History Month, I latched onto the idea of exploring YA’s abortion narratives. I put out a call for titles and talked with several clinic workers who have heard thousands of women’s stories to learn what they consider the most important factors in an abortion narrative. Armed with this knowledge, I was ready to read and identify any themes or patterns I found—as well as enjoy a bunch of great books.

Not a lot of YA books mention abortion, and even fewer feature characters who choose to have an abortion or point-of-view characters having an abortion. I compiled a list of around 20 titles, and got my hands on about 15 of them to read.

After my talk with the clinic workers, I identified three important factors:

Economics: How the books address the financial burden of abortion—from the cost of the actual procedure (around $500, on average) to the many associated costs of actually getting to a clinic—often not an easy feat, especially if you’re a girl or woman living in the U.S., where many states have recently closed down and severely restricted clinic operations under the false pretext of “making them more safe.”

Because most teenagers aren’t working full-time and aren’t mothers already, I removed the job factor as well as the childcare factor from my analysis. But in reality, with the draconian laws that have been passed, especially in the last few years, many women must travel hundreds of miles, take days off work (often risking their job), and sleep in their car if they can’t afford a motel—if they have a car—all of this just to get a legal medical procedure. Many of these women are already mothers, so child-care is yet another crucial factor.

Accessibility: How accessible is the abortion? Does the character need to travel? Does she need to hide what she’s doing from authority figures? Does she need help to get to the clinic/location where the abortion takes place? Who transports her to and from the abortion provider?

Support: Who is helping the character getting the abortion? Her boyfriend? Her best friend? Parents? Aunt? (Aunts, it turns out, are kind of big in abortion books. When I discussed this with the clinic workers, they agreed. Often, teen girls will be accompanied by their aunts, best friends, or older sisters).

What kind of support is being offered? Positive or reluctant? Parental? Monetary? Emotional?

Overwhelmingly, the books I read did not address the economics of abortion at all: The cost is never mentioned in most, and isn’t a genuine problem in most that do bring it up. For example, in GINGERBREAD, Cyd reconnects with her estranged father to get the money to pay for her abortion, unwilling to tell her mother about it. He’s an affluent man who is easily able to afford it.

Accessibility is also not deeply discussed or even touched upon in most of the books. In most contemporary YA abortion narratives, it’s assumed that there’s an abortion clinic in town. I did not come across any books that included an actual scene in a clinic, though, through poetry and a few flashbacks, we see hints in AND WE STAY. Emily, the main character, also does travel to Boston with her parents to stay at her aunt’s to get the abortion there, but there are no scenes of the procedure itself—only before and after.

IN TROUBLE is the exception when it comes to accessibility. It goes deeply into the subject of abortion access, and that’s because it’s set pre–Roe vs. Wade, in the world of back alley abortions. Here, accessibility is discussed constantly because abortion was still illegal at that time. There is talk of women throwing themselves downstairs (something the character tries in desperation) and of downing 7-Up and vodka in a bid to miscarry. There is talk of neighbors who “know someone” who can help a girl “in trouble.” It examines in depth the coded language women had to use with doctors who were willing to risk their licenses to perform abortions. It also describes pregnant women who fake mental illness, hoping to be deemed unfit so that the hospital is forced to give them an abortion.

Support is an interesting aspect of YA abortion narratives. Almost always, the teenagers tell one or both of their parents, often quite soon after finding out the pregnancy. Interestingly, I found several books featuring divorced parents in which the teen confesses to one parent—who decides not to inform the co-parent.

Most of the books have a “confession” scene in which the parents are told about the pregnancy. Almost always, the parents react with initial anger but then accept the situation, moving straight to support. Even in AND WE STAY, where Emily’s parents come off as cold in many ways, they immediately get to work on fixing the “problem.”

In these books, parental awareness of the pregnancy ties directly into the lack of consideration regarding the economics of abortion as well as problems with transportation: If the parents know, it’s assumed they’re paying for it (and providing transport to the clinic), so the cost is never mentioned.

The difficulties that many girls and women face in reality are rarely addressed in the fictional world of YA abortion narratives. Lying to one’s parents, going without support, finding the money, finding the transportation, and finding the time (many states have waiting periods, and often clinics only perform abortions on one day of the week).

With the exception of a few, most of the books that have a character getting an abortion feature white, privileged, “good girls”—affluent girls who were virgins and are going to college… girls who aren’t “that kind of girl.” This pattern avoids the stigma and myth of the “slut who uses abortion as birth control” perpetuated by the anti-choice movement, as well as the lit community’s own problem with judging girl characters much more harshly than boys.