Kelly Jensen's Blog, page 146

May 14, 2013

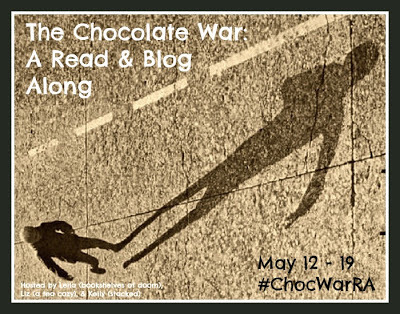

Guest Post: Why The Chocolate War Matters by Angie Manfredi

Today as part of our Chocolate War read and blog along, we have a guest post from librarian and blogger Angie Manfredi about why this book matters to her and to YA lit more broadly.

Michelangelo Antonioni and Ingmar Bergman, two of cinema’s greatest directors, died on the same day. A few weeks later, The New York Times simultaneously published appreciations of their work by two more of cinema’s greatest directors. Martin Scorsese wrote a piece about Antonioni entitled The Man Who Set Film Free and Woody Allen wrote a piece about Bergman entitled The Man Who Asked Hard Questions. The cinephile in me fluttered with joy at this but, more than that, the book lover in me saw those two titles and thought instantly of one writer: the young adult author, Robert Cormier.

To me, no one is a better fit for these two monikers. Cormier was the man who set young adult literature free and, perhaps more than anything, he was a man who asked hard questions.

In none of his books is this more evident than in the classic The Chocolate War. Published in 1974, it’s sometimes referred to as the first young adult novel, but if I were making judgments about that, I’d give the honor to S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders which appeared in 1967. But there is a real case to be made for The Chocolate War as the beginning of young adult literature as we know it today and it’s not just “this book was different than children’s books because it was still for juvenile readers but it had teen characters and dealt with ‘mature’ topics!” No, The Chocolate War is the book that asks hard questions simply because it doesn’t claim to have any answers.

I will spare you the standard recap, you probably know it already. But let’s pretend you don’t: Jerry goes to a private Catholic boy’s school. Jerry dares disturb the universe and resists the mandate from the ruling clique at his school that he must sell chocolates to fundraise for their cronyism.

You know what happens next, don’t you?

Jerry collects a band of fellow misfits and begins to truly question the power structures inherent not just at his school but in the world. Jerry and his misfits rise up, against great odds and with much at stake, to expose the injustice.

Of course!

And you know what happens next, don’t you?

Jerry and friends are victorious! Slowly but surely the rest of the school rallies around them inspired by their courage to also speak out, there’s a empathic adult there to lend insight and support at just the right time (possibly Jerry’s father, who has roused himself from the depression he’s been in for most of the book to really be there and connect with his son) and Jerry who stood up for what he knew what was right ... Jerry’s so glad he disturbed the universe.

Ah, wait.

That is, of course, not at all the way The Chocolate War ends. No, The Chocolate War ends with the status quo safely in place, the adults in the story more than just blindly looking the other way, but actively shielding and defending the teens who have committed criminal acts. And the bullies? Their power is not just intact, nay, it has been strengthened by this show of ultimate force. We leave Jerry literally beaten to a pulp, muttering to his single ally that trying to disturb the universe won’t work and, in fact, isn’t worth it.

And it is this ending, completely devoid of even a shred of hope or light, that is the brutal crowning grace of The Chocolate War and, moreover, this is the moment young adult literature is really and truly set free from the constraints and conventions of children’s literature. Nothing before this moment has achieved the same severing of young adult literature from children’s literature. Yes, there’s an actual death in The Outsiders, but we leave Pony Boy with a pen in his hand, the hope for words and healing. There is none of that in The Chocolate War - the powerful stay powerful, corruption runs deeper than we could have guessed, and our hero is hauled out on a stretcher.

To me, Cormier’s greatest legacy is the clear definition between children’s and young adult literature. There was no mistaking it - this was not a book for children. It was a book for older readers, those ready to tackle big, hard questions and moral grey areas, readers who didn’t demand or need everything all wrapped up with a big bow. Yet even with that, it still wasn’t for adults. No - this was a book just for teens. All these years later, it still is.

When Kelly and Liz announced this project, I decided I wanted to participate. I re-read it for what was about the fifth time in preparation for writing and the one thing that stood out to me was how current, how immediate, it still feels. Reading about the way adults not only refuse to get involved but often support the bullies? I couldn’t help but think of places like Steubenville, Ohio. The powerlessness Jerry feels? Cormier builds that tension with an intense, almost claustrophobic mastery - you are entirely wrapped up in this insular and sharply dangerous world. That’s a reality so many teens still live with. Adult readers may feel unsettled by The Chocolate War but I think teen readers, still, will find much to relate to in it.

With The Chocolate War, Cormier asked hard questions about morality and justice that young adult literature is still trying to answer. It’s this reason, after all this time, he’s still the writer that set us free.

***

Angie Manfredi is the Head of Youth Services for Los Alamos County Libraries. She blogs at www.fatgirlreading.com and tweets incessantly @misskubelik. Her most recently finished book was Sidekicked by John David Anderson.

Related StoriesThe Chocolate War: A Cover Retrospective, English EditionsThe Chocolate War: First ImpressionsThe Chocolate War Read & Blog Along: Starting Line

Related StoriesThe Chocolate War: A Cover Retrospective, English EditionsThe Chocolate War: First ImpressionsThe Chocolate War Read & Blog Along: Starting Line

Published on May 14, 2013 22:00

May 13, 2013

The Chocolate War: A Cover Retrospective, English Editions

Here's a little fun. How many different looks does Cormier's The Chocolate War have, anyway? The book first published in 1974, and it's remained in print since then, with a number of different cover designs. Let's talk a walk down cover memory lane.

Before I dive in, I want to note that it is really hard to research the covers of this book. There are many of them, and finding dates for when the cover first appeared wasn't easy. So if there are big inaccuracies (and I am hoping there aren't) or you know of additional covers, I'd love to know in the comments. Some of the dates I'm going to throw out are best guesses, too, based on the research I could tease out.

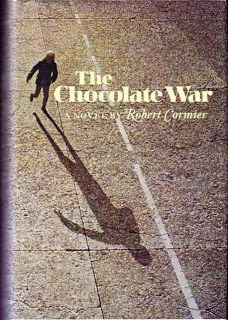

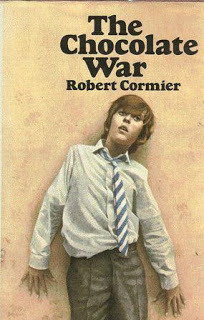

Let's start at the beginning, shall we? Here's our 1974 cover.

You might note that this is the same image that was used in the 30th anniversary edition of The Chocolate War, too. What's interesting is how there's really not too much about the cover: it's dark, and there's the ominous shadow of the boy on the cover. I do love how huge and almost foreboding the shadow looks, too. The boy himself appears young, too. But otherwise, this cover doesn't tell the reader a whole lot about the book. It fits with what was in vogue in YA covers for the 70s (of what I've seen anyway) and it looks like the kind of book that could have a wide appeal to it.

On the left is a cover from the late 1970s, and it sure tells a different story than the original. First, the tagline is pretty great: "A compelling combination of The Lord of the Flies and A Separate Peace." There's also a blurb from The New York Times that calls the book "Masterfully structured and rich in theme." And here we have boys with faces, all wearing some nice suit jackets, and they're standing in front of what I assume is Trinity. All of the boys look high school age here, maybe even older. I can't tell too well because of the cover's size, but I could see the guy standing in the middle being an adult, even. He's dressed a little more professionally. Perhaps one of the Brothers?

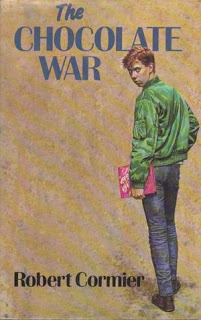

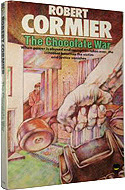

The cover on the right is one of the -- if not the -- original UK covers. I really dig the look on this because I feel like it conveys the story quite well. The boy's dressed as though he's going to a fancy prep school, and yet he's disheveled like he's scared or nervous or worried. Or all three. His back is against the wall too, which I think gets to the heart of the book without being too obvious or too symbolic. I think the boy looks kind of young for high school but I almost like that because it heightens those thoughts and feelings he's portraying physically.

The 1985 UK edition of The Chocolate War offers up a boy who is giving the reader one of the fiercest looks I've seen on a cover. And that is in no way how I imagine Jerry looking, either. The cover model is a little too exaggerated for what image I have in my mind. But boy do I love that green jacket and pink notebook look going on here. Not to mention the very fitted jeans -- I think it's with what the style was at the time of publication.

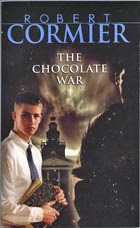

Here's where I wonder about my research on the covers. The one on the right is the cover I got with my ebook and which I know I had a few years ago in print. From what I researched, this was the 1985 cover, too. But there have been, as you'll see in a bit, some additional cover choices between 1985 and today. Either way, this is probably my favorite of the cover renditions because I think it captures the feelings of the book perfectly. You get the prep school in the back, and it's not a friendly-looking place (the cloudy background definitely amplifies that). Then you have Jerry on the left, with his button down and tie look, which is definitely prep school. This is how I picture Jerry in my mind, too: he looks like your average teen boy. He has the short, buzzed cut. He's your everyday looking high school boy. Who is the shadowy figure on the right though? That's where I like this cover a lot: it could be so many people. And it's ominous and dark and just looming over Jerry. Plus, there's the use of shadow and light, of black and white. It's smart, simple, and gets to the point. Also, I think it's pretty memorable.

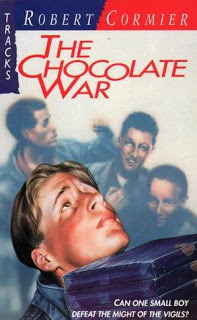

The cover on the left is a 1988 edition. Talk about a very . . . representative cover. There's Jerry (I'm assuming) buried beneath the weight of boxes of chocolate, while three boys make threatening and ridiculous faces and gestures in the background. I don't know what's going on with the guy on the far left because it looks like he's got it out for the guy in the middle. I could make some guesses on who is who here, but it's almost more enjoyable to take the image in as a whole. This book came with a tag line, too: "Can one small boy defeat the might of the vigils?" What's maybe most interesting to me in this cover is that I don't recall Jerry every being physically buried under the weight of the literal boxes of chocolate. I mean, it's up to his chin!

In 1986, we had our first cover which alludes to the fact Jerry plays football in the story. Doesn't he ever look sad in this one? He's standing, surrounded by clouds, and there's a school far in the background. While this is far from my favorite cover for the book, what I do like is that the shadow is there again. I like the play of the black and white and the shadow and light.

Here's a 1991 edition from Britain, and all I can say is that it certainly dates itself. Why are the chocolates so many fancy shapes surrounding Jerry's face? What's going on in the background with his face, is it a really big shoulder (presumably shoulder pads with his football uniform) or is there just a chunk of white coloring beneath a chunk of dark blue coloring?

On the right, a 2001 paperback edition of The Chocolate War offers us something technicolored and out of the early 1990s. Why is the guy green here? And why does he have really long hair and look like he's wearing something that would never fly in a prep school? I guess I'm glad we see the first, as if there really is a war to be fought. The chocolate-colored background is a nice touch.

The cover on the left is for one of the bindup editions out in the 2000s, so it includes both The Chocolate War and Beyond the Chocolate War. It's pretty non-memorable and not noteworthy, though I like that it uses chocolate coloring, I guess.

But check out this cover for one of the Recorded Books editions of the book. Talk about prep school. Look at this proper young boys. None of them would ever be bad. None of them would ever do nasty things. They all look so, so innocent. And so YOUNG. No way those are high schoolers! But I do have my eye on the curly haired red head in the back on the right. He looks like trouble. I should note that none of these books looks a thing like what I imagined anyone in the book to look like.

I could find nothing about this cover, and I would love to know more. When I first ran across it, it didn't make a lot of sense to me. Why a phone? Why is there a boy hiding in the background. But, after I read the book, this cover actually made perfect sense. The prank calling. The emotions expressed in the veiny arm itself. The way the phone looks like it's being slammed down. Then the boy in the background, he looks a little scared or intimidated. But he's not cowering. He's not entered into complete fear yet. The color scheme on the cover makes me think this is an early edition -- 1970s or 1980s -- but I can't find anything to tell me a definitive date.

Of all the covers, I think my favorite is the one that's still around in print today, noted above. It seems most representative and most appealing to me. It has a timeless quality to it.

Do you have any preferences? Know of any other English (US, UK, or Australian) editions or have any dating information on these covers? I'd love to know.

And you better believe I have a post coming later this week with some of the amazing foreign editions of The Chocolate War that aren't in English. There are some stark differences in what images are representative of the story elsewhere -- some which are good and some which are all together misleading.

Related StoriesThe Chocolate War: First ImpressionsThe Chocolate War Read & Blog Along: Starting LineThe Chocolate War Read & Blog Along

Related StoriesThe Chocolate War: First ImpressionsThe Chocolate War Read & Blog Along: Starting LineThe Chocolate War Read & Blog Along

Published on May 13, 2013 22:00

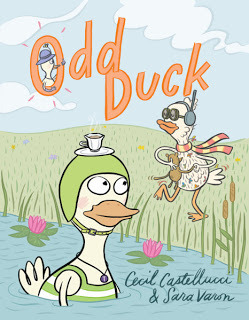

Odd Duck by Cecil Castellucci and Sara Varon

What happens when two favorite authors team up and make a graphic novel? You get Odd Duck and it is everything you'd hope it could be -- and maybe even a little more!

What I love about Sara Varon's work is how she tells stories of friendship that aren't sappy and that are real in their imperfections. Cecil Castellucci does the same thing in her stories -- the friendships are flawed and yet, wholly real in those flaws.

In Odd Duck, we meet Theodora, who is perfect. She loves her life, including the fact she's the only duck who buys mango salsa and the only duck who checks out certain books in the library (the librarian has to even dust those titles since they've been shelf sitters for so long). She doesn't want anything to change because she is happy with who she is. Things are calm, peaceful, and serene.

But then Chad moves in next door. Chad colors his feathers, lives in a house that's boarded up and messy, and he's anything but coordinated nor quiet. He frustrates Theodora's quiet and peaceful life. Why does he have to be there and ruin everything she has going for her? Theodora is not happy.

When the two of them finally talk, bonding over their shared love and appreciation for the night sky, they discover they have a lot more in common than appears on the surface. But when they're going for a walk one afternoon and overhear the other ducks whispering about the "Odd Duck," each accuses the other of being the weird one. Neither of them wants to admit to being the "odd duck." Because neither of them are, of course -- Theodora is perfectly normal in her quiet ways and Chad is perfectly normal in his more colorful life. But when called out, it appears both Chad and Theodora think of each other as odd, even if they never wanted to admit it.

Suddenly, the two of them find themselves fighting. Now everything Chad does irritates Theodora and vice versa.

But of course, they find themselves lonely. They miss each other's odd habits, and they miss spending time together. It's not too long before they decide to make amends and choose to be friendly with one another again.

Maybe it was each other's embracing of their own oddness that made them so companionable after all.

This is charming read without being saccharine, and it's wildly funny. It's perfectly appropriate for very young readers. There's nothing to blush at here -- it's the kind of book that will work for elementary readers through your older adult readers who appreciate a fun, lighthearted read about the power of friendship and embracing your eccentricities.

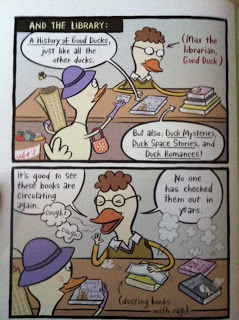

The art, as one would expect from Varon, is fantastic, vibrant, and equally as funny as the writing itself. The design of this book is super appealing, too: it's a hard cover, and the boards are done in the many portraits of Theodora and Chad. Odd Duck is the kind of book you read more than once. You first read it for the story, then you go back again and again to pick up on all of the subtleties in the illustrations. There's a keen attention to detail that distinguishes Theodora from Chad. I love the panels on the right -- Theodora is prim and proper, even wearing gloves as she's checking out old books from the library. Max, the librarian, is a good duck -- though I would argue he could use some help weeding his collection a little better.

The art, as one would expect from Varon, is fantastic, vibrant, and equally as funny as the writing itself. The design of this book is super appealing, too: it's a hard cover, and the boards are done in the many portraits of Theodora and Chad. Odd Duck is the kind of book you read more than once. You first read it for the story, then you go back again and again to pick up on all of the subtleties in the illustrations. There's a keen attention to detail that distinguishes Theodora from Chad. I love the panels on the right -- Theodora is prim and proper, even wearing gloves as she's checking out old books from the library. Max, the librarian, is a good duck -- though I would argue he could use some help weeding his collection a little better. I give bonus points to Castellucci and Varon for how easy it is to see Theodora is an introvert and completely happy with her introverted lifestyle and yet, she's still able to develop a worthwhile and valuable friendship with someone so opposite herself. It's a smaller detail, but it's one I really appreciated.

Odd Duck is clever and fun and a book that earns a worthy spot right next to other graphic novels like Robot Dreams and Bake Sale as ones worth visiting again and again.

Review copy received from the publisher. Odd Duck is available now.

Related StoriesNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong -- Faith Erin Hicks on the collaborative effortNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin HicksThree Cybils Reviews: The Clunkers

Related StoriesNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong -- Faith Erin Hicks on the collaborative effortNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin HicksThree Cybils Reviews: The Clunkers

Published on May 13, 2013 22:00

May 12, 2013

The Chocolate War: First Impressions

I've read The Chocolate War before.

It was one of the first YA books I read in the YA Lit class I took in graduate school. Which means it's a book Kimberly's read, too -- for those of you just tuning in, she and I met when we took that class.

Let me tell you a little bit about myself, circa September 2008: I had yet to actually work in a library with teenagers. I'd worked with teenagers before, but it was in a classroom setting for one summer. These were a very narrow group of teens. And this is nothing against them because they were wonderful to work with, but they all came from privilege, were all gifted, and they were all selected to participate in this series of advanced-level summer classes.

In other words, I'd yet to see the extremes of teens. I saw a pretty homogenous group with similar backgrounds.

My reading and reflection upon books and their audience very much was telling in my own experiences. (Isn't it neat to see that in yourself, though? That's one huge benefit of keeping track of your thoughts on books -- you see your own growth and development as a reader and thinker and professional.)

To be fair, I don't think I liked any of the books I read in the class I took. We read only a handful of classics, and the book that was most updated in our reading was The Geography Club. I did record all of my reactions to the books in Goodreads, so naturally, I have a nice review of The Chocolate War to share:

Not as controversial as I hoped, though I was disgusted by the characters discussing how they raped attractive girls with their eyes.

That's all I had to say about Cormier's book on my first read. I suspect my second read might merit a few more words, and I'm dying to know whether either of these statements still hold true. What did I want in terms of controversy in 2008? Will I see gender issues still? I'm actually pretty surprised to see that pop up in my review because when I thought about my reading of the book back then, gender wasn't something I remembered at all. But it was apparently noteworthy!

Now, I should note that I did a couple of significant projects on banned and challenged books before I went to library school. My threshold for what I controversial, well. Let me say The Chocolate War may have been the most gritty (if that's even the word I want) book I read to date at that point. So my perspective was not necessarily what it is today now that I've discovered dark contemporary books are totally my thing.

I've read so much more since 2008. I've also learned about reading and about the history of YA. I bring a lot more to the book and to the history of it now. Will this context and experience change my reading experience?

I guess we'll find out at the end of the week.

Related StoriesThe Chocolate War Read & Blog Along: Starting LineThe Chocolate War Read & Blog Along

Related StoriesThe Chocolate War Read & Blog Along: Starting LineThe Chocolate War Read & Blog Along

Published on May 12, 2013 22:00

So You Want to Read YA?: Guest Post from Author Cecil Castellucci

This week's contribution to "So You Want to Read YA?" comes from author Cecil Castellucci. She's straight to the point, too!

Cecil Castellucci is the author of books and graphic novels for young adults including Boy Proof, The Plain Janes, First Day on Earth, The Year of the Beasts and Odd Duck. Her picture book, Grandma’s Gloves, won the California Book Award Gold Medal. Her short stories have been published in Strange Horizons, YARN, Tor.com, and various anthologies including, Teeth, After and Interfictions 2. She is the YA editor of the Los Angeles Review of Books, Children’s Correspondence Coordinator for The Rumpus and a two time Macdowell Fellow. She lives in Los Angeles. She can be found on Twitter @misscecil and at http://www.misscecil.com.

We all know why we’re here.

As a lady who moves fluidly between the young adult world, comic book world and the adult literary scene everyone always tells me how much they love YA. But they haven’t actually read that much of it. They’ve mostly read the few standards that everyone reads and says they’ve read to keep up with the Jones’s and sound cool at cocktail parties: Twilight, Harry Potter, The Golden Compass, The Hunger Games and The Fault in our Stars. And while we all agree those books are good to have a toe dipped into our fabulous pool, I really feel that we need to get some other YA books into adult land heavy rotation.

So what to suggest to people as a place to go to after they’ve whet your appetite with the regular books that everyone’s already heard of? In my list I’m sticking to older classics that have stood the test of time by being out already for a few years.

1) Feed by MT Anderson

2) Ash by Malinda Lo

3) The Chaos Walking trilogy by Patrick Ness

4) Swallow Me Whole by Nate Powell (*he also drew my book The Year of the Beasts which is adult friendly)

5) Little Brother by Cory Doctorow

6) Flygirl by Sherri L Smith

7) The Ruby in Smoke by Phillip Pullman

8) Daughter of Smoke and Bone by Laini Taylor

9) When you Reach Me by Rebecca Stead

10) I am the Messenger by Markus Zusak

Related StoriesSo You Want to Read YA?: Guest Post from Author Bryan BlissSo You Want to Read YA?: Guest Post by Kate Testerman, Literary AgentSo You Want to Read YA?: Guest Post from librarian/blogger Sarah Bean Thompson

Related StoriesSo You Want to Read YA?: Guest Post from Author Bryan BlissSo You Want to Read YA?: Guest Post by Kate Testerman, Literary AgentSo You Want to Read YA?: Guest Post from librarian/blogger Sarah Bean Thompson

Published on May 12, 2013 22:00

May 11, 2013

The Chocolate War Read & Blog Along: Starting Line

This is the week! Liz Burns, Leila Roy, and myself will be reading and blogging about our experiences and thoughts about Robert Cormier's The Chocolate War. Anyone is welcome to join in during the week, by either blogging about the book or contributing a piece to STACKED. Just leave a note and I can hook you up. I've got a few posts planned throughout the week tackling everything from first impressions to a formal review and more things I don't want to lay out quite yet.

If you're joining in and posting on your own blog, please drop a link for each post you write in the comments. We'll try share it across our social networks, and we'll do a roundup of selected posts at the end of the week to highlight everyone else's thoughts and posts. And please feel free to steal our image above and use it for your posts!

Let's get real with one of the most well-known YA, not to mention one of the foundational, realistic titles.

Related StoriesThe Chocolate War Read & Blog Along

Related StoriesThe Chocolate War Read & Blog Along

Published on May 11, 2013 22:00

May 9, 2013

Secret Historical Societies of Teenage Girls: A Brief List

I don't know if I can fairly call this a mini-trend, since it seems like something that's been ongoing since I was a teen, but it's one I love: historical girls who join all-female secret groups or societies to carry out dangerous but important activities. Usually the secret group has an innocent, innocuous, and thoroughly gender-appropriate cover - it's a finishing school or a nunnery; the girls learn to be lady's maids or governesses. In reality, though, the girls learn how to spy, how to kill, how to be physically and intellectually powerful in a world where otherwise they would have had almost no agency of their own.

Women and girls in the time periods highlighted in these books generally would have had very little power in any of the traditional roles, and I think this is a fun way to subvert that. Y. S. Lee, who writes the excellent Agency series, states as much in her author's note, which I return to again and again:

The title of her series is a nod to this as well, I think.

Complicating these stories is the fact that in many of them, the girls are forced against their will into these secret societies. What does that say about the power they have - or don't have - within the group compared to the world at large?

I have always been drawn to these sorts of stories. As a girl, it was a

way for me to have my cake and eat it too: I could escape to another

time while also not encounter all the strictures of that historical

period most girls would have endured. A lot of what I read as a teenager

was a way for me to read about girls with power (magical and

otherwise), since I felt I had so very little of it myself. I think this

is a major reason these stories continue to be popular today.

I've collected just a smattering of recent titles that explore this concept below. Each book is the start of a series, and all descriptions come from Worldcat. I've linked each title to either Goodreads or my review.

Maid of Secrets by Jennifer McGowan

In 1559 England, Meg, an orphaned thief, is pressed into service and

trained as a member of the Maids of Honor, Queen Elizabeth I's secret

all-female guard, but her loyalty is tested when she falls in love with a

Spanish courtier who may be a threat.

Grave Mercy by Robin LaFevers

In the fifteenth-century kingdom of Brittany, seventeen-year-old

Ismae escapes from the brutality of an arranged marriage into the

sanctuary of the convent of St. Mortain, where she learns that the god

of Death has blessed her with dangerous gifts--and a violent destiny.

Etiquette and Espionage by Gail Carriger

Sophronia, a fourteen-year-old tomboy, has been enrolled in a finishing

school to improve her manners. But the school is not quite what her

mother was expecting -- here young girls learn to finish...everything.

As well as the finer arts of dress, dance and etiquette, they also learn

how to deal out death, diversion and espionage.

The Agency by Y. S. Lee

Rescued from the gallows in 1850s London, young orphan and thief Mary

Quinn is offered a place at Miss Scrimshaw's Academy for Girls where she

is trained to be part of an all-female investigative unit called The

Agency and, at age seventeen, she infiltrates a rich merchant's home in

hopes of tracing his missing cargo ships.

Have I missed any biggies published for teens within the past few years? I'm looking specifically for historical titles, so stories about girls training at a secret school to be spies in modern times aren't the target (though I do love those sorts of books, they are not quite the same). Do you read and love these books as much as I do?

Related StoriesIn the Shadow of Blackbirds by Cat WintersNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin HicksThe Lucy Variations by Sara Zarr

Related StoriesIn the Shadow of Blackbirds by Cat WintersNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin HicksThe Lucy Variations by Sara Zarr

Women and girls in the time periods highlighted in these books generally would have had very little power in any of the traditional roles, and I think this is a fun way to subvert that. Y. S. Lee, who writes the excellent Agency series, states as much in her author's note, which I return to again and again:

Women's

choices were grim in those days, even for the clever. If a top secret

women's detective agency existed in Victorian England, it left no

evidence - just as well, since that would cast serious doubt on its

competence. The Agency is a totally unrealistic, completely fictitious

antidote to the fate that would otherwise swallow a girl like Mary

Quinn.

The title of her series is a nod to this as well, I think.

Complicating these stories is the fact that in many of them, the girls are forced against their will into these secret societies. What does that say about the power they have - or don't have - within the group compared to the world at large?

I have always been drawn to these sorts of stories. As a girl, it was a

way for me to have my cake and eat it too: I could escape to another

time while also not encounter all the strictures of that historical

period most girls would have endured. A lot of what I read as a teenager

was a way for me to read about girls with power (magical and

otherwise), since I felt I had so very little of it myself. I think this

is a major reason these stories continue to be popular today.

I've collected just a smattering of recent titles that explore this concept below. Each book is the start of a series, and all descriptions come from Worldcat. I've linked each title to either Goodreads or my review.

Maid of Secrets by Jennifer McGowan

In 1559 England, Meg, an orphaned thief, is pressed into service and

trained as a member of the Maids of Honor, Queen Elizabeth I's secret

all-female guard, but her loyalty is tested when she falls in love with a

Spanish courtier who may be a threat.

Grave Mercy by Robin LaFevers

In the fifteenth-century kingdom of Brittany, seventeen-year-old

Ismae escapes from the brutality of an arranged marriage into the

sanctuary of the convent of St. Mortain, where she learns that the god

of Death has blessed her with dangerous gifts--and a violent destiny.

Etiquette and Espionage by Gail Carriger

Sophronia, a fourteen-year-old tomboy, has been enrolled in a finishing

school to improve her manners. But the school is not quite what her

mother was expecting -- here young girls learn to finish...everything.

As well as the finer arts of dress, dance and etiquette, they also learn

how to deal out death, diversion and espionage.

The Agency by Y. S. Lee

Rescued from the gallows in 1850s London, young orphan and thief Mary

Quinn is offered a place at Miss Scrimshaw's Academy for Girls where she

is trained to be part of an all-female investigative unit called The

Agency and, at age seventeen, she infiltrates a rich merchant's home in

hopes of tracing his missing cargo ships.

Have I missed any biggies published for teens within the past few years? I'm looking specifically for historical titles, so stories about girls training at a secret school to be spies in modern times aren't the target (though I do love those sorts of books, they are not quite the same). Do you read and love these books as much as I do?

Related StoriesIn the Shadow of Blackbirds by Cat WintersNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin HicksThe Lucy Variations by Sara Zarr

Related StoriesIn the Shadow of Blackbirds by Cat WintersNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin HicksThe Lucy Variations by Sara Zarr

Published on May 09, 2013 22:00

On Cover Flipping

I love a good conversation about book covers, so when Maureen Johnson stepped up and called for discussion and commentary on gendered covers, I started thinking. First, go read post which contains some of the redesigned covers created by readers. The long and short of the post is that female-authored books tend to have covers with a feminine slant, while male-authored books tend to have more literary covers to them (or more masculinely slanted covers).

This is actually not a new discussion at all. It's something Kiersten White brought up a few months ago on Twitter, in relation to John Green's The Fault in Our Stars. Would the cover look different if it were Jennifer Green instead? That's not a knock on the book nor on the quality. It's a good question about what we assume of books penned by male authors, as opposed to female.

Maureen's post set off a number of really interesting reactions, some of which I saw stemming from her post and some which took a part of her post and went in a different direction. Justina Ireland wrote about feminism and about how she can like girly covers. Amanda Hocking wrote about how she's complex, and how she like both those things which are girly and those which typically aren't. Trish Doller wrote about her own cover and how books with similar themes as her own have different covers than hers (which is much more romantic in nature than the book itself).

I could write at length about any or all of these topics, but what has been sticking out in my mind is that of the male voice in YA. More specifically, the male voice as written by a female.

The male voice as written by a female whose names appear on covers like this:

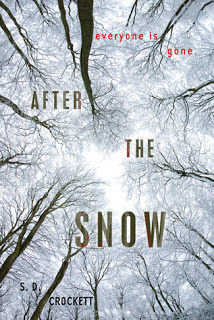

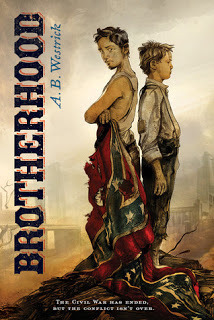

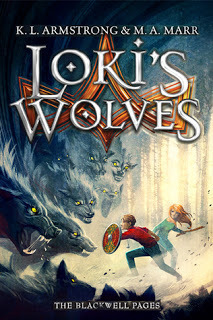

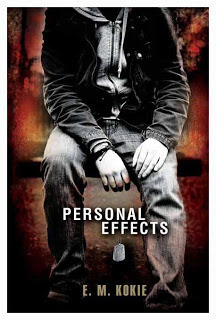

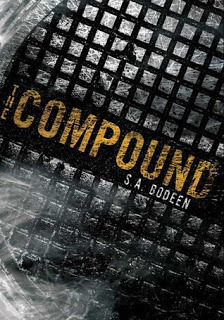

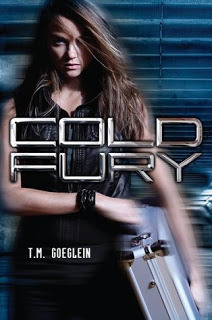

All of these male-voices YA titles are written by women whose names are initials on the cover. More specifically, all of these first YA novels featuring male voices have initialized author names on the cover, degendering their names. Note that Marissa Marr and Kelly Armstrong's first middle grade collaboration, which is a male-voiced novel, uses this technique too.

Obviously plenty of females use initials for their names. Many of the authors listed above likely do just that. But what's interesting to me is that this trend doesn't happen much the other way around. And maybe it's that there are fewer male writers whose first books are written in a female voice.

I can think of one first YA novel written by a male with a lead female where his name is initialed.

Maybe what's as interesting to me as the initial use is that all of the covers above are either images that are gender neutral or they feature a male on the cover. These books appeal to both male and female readers in equal measure for both those reasons.

Does using an initial or two in place of an author's full first name, though, impact reader perceptions of the book or the voice within it? In other words, had S. D. Crockett's After the Snow had her first name on it -- Sophie -- would readers see the book differently? Would they not believe the male voice?

I have a lot more I want to say on covers like C. Desir's Fault Line, but since it doesn't come out until the fall, I'm saving my comments until then. I've had a lot of pause for thought lately, and I think that Maureen's bringing up this topic of gendered covers is an important one. I think about it from the point of view of a librarian who works with teens and who adamantly believes that there is no such thing as gender in a book. Sure, covers can tap into the visually appealing elements that are socially associated with females and those which are socially associated with males. And there is absolutely nothing wrong with a cover that has a couple kissing on it -- if that's what the book is about, then it's going to find its audience pretty well.

So then I wonder: are names and the way they appear on YA covers a marketing technique, too? Is using one's initials to "degender" a name a means of reaching that elusive male readership if the book features a male voice? Would boy readers not believe the authenticity of any of the books above or others if the name on the cover was Emily or Erin or Sarah or Stephanie or Christina?

There's a lot to chew on, and I'd be curious if anyone can think of examples either way: where the male-led novel written by a female has her initials as her author name or where a female-led novel written by a male has his initials as his author name. As I said before, this is a trend I've noticed in first YA novels, but it's possible there are instances where pseudonyms are used. Lay them on me!

This is actually not a new discussion at all. It's something Kiersten White brought up a few months ago on Twitter, in relation to John Green's The Fault in Our Stars. Would the cover look different if it were Jennifer Green instead? That's not a knock on the book nor on the quality. It's a good question about what we assume of books penned by male authors, as opposed to female.

Maureen's post set off a number of really interesting reactions, some of which I saw stemming from her post and some which took a part of her post and went in a different direction. Justina Ireland wrote about feminism and about how she can like girly covers. Amanda Hocking wrote about how she's complex, and how she like both those things which are girly and those which typically aren't. Trish Doller wrote about her own cover and how books with similar themes as her own have different covers than hers (which is much more romantic in nature than the book itself).

I could write at length about any or all of these topics, but what has been sticking out in my mind is that of the male voice in YA. More specifically, the male voice as written by a female.

The male voice as written by a female whose names appear on covers like this:

All of these male-voices YA titles are written by women whose names are initials on the cover. More specifically, all of these first YA novels featuring male voices have initialized author names on the cover, degendering their names. Note that Marissa Marr and Kelly Armstrong's first middle grade collaboration, which is a male-voiced novel, uses this technique too.

Obviously plenty of females use initials for their names. Many of the authors listed above likely do just that. But what's interesting to me is that this trend doesn't happen much the other way around. And maybe it's that there are fewer male writers whose first books are written in a female voice.

I can think of one first YA novel written by a male with a lead female where his name is initialed.

Maybe what's as interesting to me as the initial use is that all of the covers above are either images that are gender neutral or they feature a male on the cover. These books appeal to both male and female readers in equal measure for both those reasons.

Does using an initial or two in place of an author's full first name, though, impact reader perceptions of the book or the voice within it? In other words, had S. D. Crockett's After the Snow had her first name on it -- Sophie -- would readers see the book differently? Would they not believe the male voice?

I have a lot more I want to say on covers like C. Desir's Fault Line, but since it doesn't come out until the fall, I'm saving my comments until then. I've had a lot of pause for thought lately, and I think that Maureen's bringing up this topic of gendered covers is an important one. I think about it from the point of view of a librarian who works with teens and who adamantly believes that there is no such thing as gender in a book. Sure, covers can tap into the visually appealing elements that are socially associated with females and those which are socially associated with males. And there is absolutely nothing wrong with a cover that has a couple kissing on it -- if that's what the book is about, then it's going to find its audience pretty well.

So then I wonder: are names and the way they appear on YA covers a marketing technique, too? Is using one's initials to "degender" a name a means of reaching that elusive male readership if the book features a male voice? Would boy readers not believe the authenticity of any of the books above or others if the name on the cover was Emily or Erin or Sarah or Stephanie or Christina?

There's a lot to chew on, and I'd be curious if anyone can think of examples either way: where the male-led novel written by a female has her initials as her author name or where a female-led novel written by a male has his initials as his author name. As I said before, this is a trend I've noticed in first YA novels, but it's possible there are instances where pseudonyms are used. Lay them on me!

Published on May 09, 2013 12:23

May 8, 2013

Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong -- Faith Erin Hicks on the collaborative effort

We have a really fun guest post today about Prudence Shen and Faith Erin Hicks's graphic novel Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong (reviewed yesterday). I was curious what the collaborative process was like -- how do you take a story idea in words and make it into a graphic novel and do so without sacrificing the art or story? Lucky for me, Faith was happy to answer, and I find this totally fascinating. I hope you do, too.

As a bonus, we have a copy of Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong up for grabs, too, to one reader in the US. Just fill out the painless form and I'll pick a winner in a couple of weeks.

Hi, I'm Faith Erin Hicks, and I write and draw comics for a living. I took a very funny, very sweet prose novel called Voted Most Likely by Prudence Shen, and turned it into a graphic novel now called Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong, which is being published by First Second Books this week.

Let me set the stage for you: it is 2010, and it is the hottest week I've ever experienced in the five years I've lived in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Temperatures reached at least 30 degrees Celsius. I had recently finished work on my graphic novel Friends With Boys (also published by First Second Books), and was casting around for my next project. Cartoonists are a lot like sharks: we are constantly hungry and consume everything in our path, and if we don't keep moving (that is to say, working), we die.

My editor at First Second books emailed me with a proposal: she had a prose novel, one she assured me was very funny and very cool, that she wanted turned into a comic. Was I interested? I printed out a copy of Prudence's novel, and headed to a nearby air-conditioned coffee-shop to read and beat the heat. I spent most of the next four days there, reading Prudence's novel and nursing a lemonade.

I liked Voted Most Likely. It had comedy, it had heart, and most importantly, I thought it would be a lot of fun to draw, and would translate well to the medium of comic books.

The trickiest thing about turning something that's one artistic thing (a prose novel) into another thing (a graphic novel) is you have to be sure to honour the original of the story, but the final product must still be something wholly different from it. I couldn't just take Prudence's original novel, strip out the dialogue and slap some pictures down on the page. I had to transform her story, taking the subtlety of the characters' interactions, their inner thoughts and development, and make it visual art. It's tough!

I started with an outline. I read through Voted Most Likely several times, picked out the parts I thought were the most important, and wrote an outline. That outline I passed to my editor and Prudence, and once they approved it, I went forward with writing a script. I did a lot of cutting of Prudence's story. Nate's long suffering family, including his sister? Cut. Charlie's school basketball team making a run at serious competition? Cut. The details of the election sabotage? Cut cut cut. Some of the cuts I felt bad about, but I knew unless I wanted to spend the next ten yeas drawing a 1,000 page graphic novel, they were necessary.

When I script, I thumbnail at the same time. I get a thick lined notebook and fill it full of tiny stick people drawings and lay out the entire graphic novel, inserting dialogue in where it needs to be. This allows me to pay attention to the pacing of the comic while I'm writing the script. This is my personal choice to work this way (other cartoonists work differently), but I like it. Comics are a symbiosis of art and writing; in the best comics, I think, one does not take precedence over the other. Doing thumbnails and the script for a comic at the same time allows me to develop them both in tandem.

After I finished my rough handwritten script (and thumbnails), I typed the script up and sent it to my editor and Prudence. I stuck close to Prudence's original story, except for a few things at the end: I felt for a satisfying arc, the Science Club needed to face down a nemesis at the Robot Rumble, something that was lacking in the original story, and the ending would need to be a little different, as much of Charlie's basketball-related story had been cut. Prudence agreed, and we worked on the revamped scenes together.

For the most part, we worked separately, me slaving away at my drawing desk for a year and a half, Prudence ... I believe she was in the UK for at least some of the time I was working on Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong. Maybe she is secretly James Bond. Finally I emerged from my cartooning hole in the ground with the finished comic, flush with the success of completion, and craving breakfast food. And soon you will be able to read it! I hope you enjoy Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong. It is especially nice when read in an air conditioned coffee-shop during a heat wave.

Loading...

Related StoriesNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin HicksThree Cybils Reviews: The ClunkersA Pair of Cybils Reviews

Related StoriesNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin HicksThree Cybils Reviews: The ClunkersA Pair of Cybils Reviews

As a bonus, we have a copy of Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong up for grabs, too, to one reader in the US. Just fill out the painless form and I'll pick a winner in a couple of weeks.

Hi, I'm Faith Erin Hicks, and I write and draw comics for a living. I took a very funny, very sweet prose novel called Voted Most Likely by Prudence Shen, and turned it into a graphic novel now called Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong, which is being published by First Second Books this week.

Let me set the stage for you: it is 2010, and it is the hottest week I've ever experienced in the five years I've lived in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Temperatures reached at least 30 degrees Celsius. I had recently finished work on my graphic novel Friends With Boys (also published by First Second Books), and was casting around for my next project. Cartoonists are a lot like sharks: we are constantly hungry and consume everything in our path, and if we don't keep moving (that is to say, working), we die.

My editor at First Second books emailed me with a proposal: she had a prose novel, one she assured me was very funny and very cool, that she wanted turned into a comic. Was I interested? I printed out a copy of Prudence's novel, and headed to a nearby air-conditioned coffee-shop to read and beat the heat. I spent most of the next four days there, reading Prudence's novel and nursing a lemonade.

I liked Voted Most Likely. It had comedy, it had heart, and most importantly, I thought it would be a lot of fun to draw, and would translate well to the medium of comic books.

The trickiest thing about turning something that's one artistic thing (a prose novel) into another thing (a graphic novel) is you have to be sure to honour the original of the story, but the final product must still be something wholly different from it. I couldn't just take Prudence's original novel, strip out the dialogue and slap some pictures down on the page. I had to transform her story, taking the subtlety of the characters' interactions, their inner thoughts and development, and make it visual art. It's tough!

I started with an outline. I read through Voted Most Likely several times, picked out the parts I thought were the most important, and wrote an outline. That outline I passed to my editor and Prudence, and once they approved it, I went forward with writing a script. I did a lot of cutting of Prudence's story. Nate's long suffering family, including his sister? Cut. Charlie's school basketball team making a run at serious competition? Cut. The details of the election sabotage? Cut cut cut. Some of the cuts I felt bad about, but I knew unless I wanted to spend the next ten yeas drawing a 1,000 page graphic novel, they were necessary.

When I script, I thumbnail at the same time. I get a thick lined notebook and fill it full of tiny stick people drawings and lay out the entire graphic novel, inserting dialogue in where it needs to be. This allows me to pay attention to the pacing of the comic while I'm writing the script. This is my personal choice to work this way (other cartoonists work differently), but I like it. Comics are a symbiosis of art and writing; in the best comics, I think, one does not take precedence over the other. Doing thumbnails and the script for a comic at the same time allows me to develop them both in tandem.

After I finished my rough handwritten script (and thumbnails), I typed the script up and sent it to my editor and Prudence. I stuck close to Prudence's original story, except for a few things at the end: I felt for a satisfying arc, the Science Club needed to face down a nemesis at the Robot Rumble, something that was lacking in the original story, and the ending would need to be a little different, as much of Charlie's basketball-related story had been cut. Prudence agreed, and we worked on the revamped scenes together.

For the most part, we worked separately, me slaving away at my drawing desk for a year and a half, Prudence ... I believe she was in the UK for at least some of the time I was working on Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong. Maybe she is secretly James Bond. Finally I emerged from my cartooning hole in the ground with the finished comic, flush with the success of completion, and craving breakfast food. And soon you will be able to read it! I hope you enjoy Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong. It is especially nice when read in an air conditioned coffee-shop during a heat wave.

Loading...

Related StoriesNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin HicksThree Cybils Reviews: The ClunkersA Pair of Cybils Reviews

Related StoriesNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin HicksThree Cybils Reviews: The ClunkersA Pair of Cybils Reviews

Published on May 08, 2013 22:00

May 7, 2013

Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin Hicks

I have two descriptions that sum up what Prudence Shen and Faith Erin Hicks's graphic novel Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong is about: robots and high school politics.

Charlie is captain of the basketball team and the boyfriend of superhot popular cheerleader Holly. Nate is Charlie's unlikely best friend, president of the robotics team. The story begins when Charlie's been dumped by his girlfriend and Nate drops the news that the student activities funding, which will decide whether to spend their money on a national robotics event for the robotics team or on new uniforms for the cheerleaders, is being left to the student council.

Nate decides he's running for student council president so he can delegate the money to the cause he thinks deserves it more: his own.

The hitch in the plan is that Holly now wants to use Charlie to further her own cause for the cheerleaders. Yeah, they're broken up now, but Holly could bring Charlie's popularity down faster than anything if he doesn't listen to her. And her plan is simple, too: Charlie's going to run against Nate for student council president.

Enter a funny political battle. Except as funny as it is, it's also painful for Charlie and Nate, as their long-standing friendship is tested.

But when the principal gets wind of the backstabbing and the shenanigans going on in the election (because of course there is plenty of that -- we're talking social politics here of geeks vs. cool kids, of cheerleaders vs. robotics team members), he decides that the funding won't be left to the student council. Now both Charlie and Nate scramble to figure out what to do next.

That's where this story turns to robots! When there's a robotics competition with a grand prize of $10,000 -- enough money to cover both the new cheerleading outfits and the robotics event -- the two sides pitch in to build the strongest, baddest robot in order to win. But do they even have a chance on such a national level?

Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong was a fast-paced, fun story and both Nate and Charlie are well-developed. Charlie has a nice backstory going on with his family that didn't feel tacked on. Even though he's posited as the "popular" boy, there's a lot more to him than that; his parents aren't talking, and they haven't in a long time. His mom hasn't been in his life in a long time, and now she's sprung a new marriage on him. He's struggling with that and being the "nice guy" who has been strung along with Holly's plans and quest for popularity and superiority on the cheerleading squad. Nate, who on the surface looks like a quintessential geek, is more than that, too. It makes sense why these two are friends, and there are little moments in the illustrations that highlight it so well -- like when both boys are under Charlie's bed during a party-gone-wild at Charlie's parentless home. Even though this could tread the easy territory of also being a story about how cheerleaders are bad, Shen and Hicks avoid that stereotype, too, as is seen when they join in for the robotics competition and maybe even enjoy themselves while they're at it.

Shen's story is relatable for teen readers, and it's fun. The robot competition is a blast to watch unfold, and I love the subtle gender threads sprinkled through the story -- girls can kick ass in the science and robotics world, even if it's stereotypically boy-land. Hick's illustrations are appealing and enhance the story, rather than detract from it. The balance of story and paneling is done well: there's enough to pick up in both when they stand alone or when they're paired. The attention to details such as offering a diverse cast of characters was great, too. It's clear that Shen and Hicks worked well together.

Readers who enjoyed Raina Telgemeier's books and who are ready to read something at a little bit of a higher level will love this. It's a contemporary story with male friendship at the core. Also, did I mention there are robots? Because there are robots.

Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong is available now.

Review copy received from the publisher. Stop back tomorrow for a guest post about the collaborative process from Shen and Hicks themselves.

Related StoriesThe Lucy Variations by Sara ZarrThree Cybils Reviews: The ClunkersA Pair of Cybils Reviews

Related StoriesThe Lucy Variations by Sara ZarrThree Cybils Reviews: The ClunkersA Pair of Cybils Reviews

Published on May 07, 2013 22:00