Kelly Jensen's Blog, page 145

May 23, 2013

Mini-trend: Amnesia in YA

Current YA seems to be full of girls who can't remember who they are. Or perhaps if they can remember who they are, they don't remember the past five years, or five weeks, or five hours. Usually, someone is trying to kill them, and the clue to who and why lies in the lost memories.

After reading The Testing and The Program in quick succession, I realized that amnesia is a pretty huge topic right now in YA fiction. I can see the appeal - it adds automatic suspense and a sense of the mysterious. At the same time, it can be a bit of a cheat (memories come rushing back and all problems are solved!), and it often leads to a disappointing reveal.

Below are just a smattering of titles published within the last twelve months, plus a few upcoming ones we'll get later in 2013. I think it's pretty remarkable there are so many in just a little over a calendar year. If I extended the date range to two or three years, there'd be even more (such as Cat Patrick's Forgotten or Elizabeth Scott's As I Wake). So many! Descriptions come from Worldcat.

Don't Turn Around by Michelle Gagnon (August 2012)

After waking up on an operating table with no memory of how she got

there, Noa must team up with computer hacker Peter to stop a corrupt

corporation with a deadly secret. Kimberly's review

All the Broken Pieces by Cindi Madsen (December 2012)

Following a car accident, Liv comes out of a coma with no memory of her

past and two distinct, warring voices inside her head. As she stumbles

through her junior year, the voices get louder until Liv meets Spencer,

whose own mysterious past also has him on the fringe.

Hysteria by Megan Miranda (February 2013)

After stabbing and killing her boyfriend, sixteen-year-old Mallory, who

has no memory of the event, is sent away to a boarding school to escape

the gossip and threats, but someone or something is following her.

Pretty Girl-13 by Liz Coley (March 2013)

Sixteen-year-old Angie finds herself in her neighborhood with no

recollection of her abduction or the three years that have passed since,

until alternate personalities start telling her their stories through

letters and recordings. Kelly's review

Unremembered by Jessica Brody (March 2013)

A girl, estimated to be sixteen, awakens with amnesia in the wreckage of

a plane crash she should not have survived and taken into foster care,

and the only clue to her identity is a mysterious boy who claims she was

part of a top-secret science experiment. Kimberly's review

The Program by Suzanne Young (April 2013)

When suicide becomes a worldwide epidemic, the only known cure is The

Program, a treatment in which painful memories are erased, a fate worse

than death to seventeen-year-old Sloane who knows that The Program will

steal memories of her dead brother and boyfriend.

Arclight by Josin L. McQuein (April 2013)

The first person to cross the barrier that protects Arclight from the

Fade, teenaged Marina has no memory when she is rescued but when one of

the Fade infiltrates Arclight, she recognizes it and begins to unlock

secrets she never knew she had.

Nothing But Blue by Lisa Jahn-Clough (May 2013)

Aided by a mysterious, possibly magical dog named Shadow and by various

strangers, a seventeen-year-old with acute memory loss who calls herself

Blue makes a 500-mile trek to her childhood home, unaware of what she

has left behind.

The Testing by Joelle Charbonneau (June 2013)

Sixteen-year-old Malencia (Cia) Vale is chosen to participate in The

Testing to attend the University; however, Cia is fearful when she

figures out her friends who do not pass The Testing are disappearing. Kimberly's review

The Girl Who Was Supposed to Die by April Henry (June 2013)

She doesn't know who she is. She doesn't know where she is, or why. All

she knows when she comes to in a ransacked cabin is that there are two

men arguing over whether or not to kill her. And that she must run.

Follow Cady and Ty (her accidental savior turned companion), as they

race against the clock to stay alive.

Another Little Piece by Kate Karyus Quinn (June 2013)

A year after vanishing from a party, screaming and drenched in blood,

seventeen-year-old Annaliese Rose Gordon appears hundreds of miles from

home with no memory, but a haunting certainty that she is actually

another girl trapped in Annaliese's body.

Related StoriesThe Testing by Joelle CharbonneauSecret Historical Societies of Teenage Girls: A Brief ListNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin Hicks

Related StoriesThe Testing by Joelle CharbonneauSecret Historical Societies of Teenage Girls: A Brief ListNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin Hicks

After reading The Testing and The Program in quick succession, I realized that amnesia is a pretty huge topic right now in YA fiction. I can see the appeal - it adds automatic suspense and a sense of the mysterious. At the same time, it can be a bit of a cheat (memories come rushing back and all problems are solved!), and it often leads to a disappointing reveal.

Below are just a smattering of titles published within the last twelve months, plus a few upcoming ones we'll get later in 2013. I think it's pretty remarkable there are so many in just a little over a calendar year. If I extended the date range to two or three years, there'd be even more (such as Cat Patrick's Forgotten or Elizabeth Scott's As I Wake). So many! Descriptions come from Worldcat.

Don't Turn Around by Michelle Gagnon (August 2012)

After waking up on an operating table with no memory of how she got

there, Noa must team up with computer hacker Peter to stop a corrupt

corporation with a deadly secret. Kimberly's review

All the Broken Pieces by Cindi Madsen (December 2012)

Following a car accident, Liv comes out of a coma with no memory of her

past and two distinct, warring voices inside her head. As she stumbles

through her junior year, the voices get louder until Liv meets Spencer,

whose own mysterious past also has him on the fringe.

Hysteria by Megan Miranda (February 2013)

After stabbing and killing her boyfriend, sixteen-year-old Mallory, who

has no memory of the event, is sent away to a boarding school to escape

the gossip and threats, but someone or something is following her.

Pretty Girl-13 by Liz Coley (March 2013)

Sixteen-year-old Angie finds herself in her neighborhood with no

recollection of her abduction or the three years that have passed since,

until alternate personalities start telling her their stories through

letters and recordings. Kelly's review

Unremembered by Jessica Brody (March 2013)

A girl, estimated to be sixteen, awakens with amnesia in the wreckage of

a plane crash she should not have survived and taken into foster care,

and the only clue to her identity is a mysterious boy who claims she was

part of a top-secret science experiment. Kimberly's review

The Program by Suzanne Young (April 2013)

When suicide becomes a worldwide epidemic, the only known cure is The

Program, a treatment in which painful memories are erased, a fate worse

than death to seventeen-year-old Sloane who knows that The Program will

steal memories of her dead brother and boyfriend.

Arclight by Josin L. McQuein (April 2013)

The first person to cross the barrier that protects Arclight from the

Fade, teenaged Marina has no memory when she is rescued but when one of

the Fade infiltrates Arclight, she recognizes it and begins to unlock

secrets she never knew she had.

Nothing But Blue by Lisa Jahn-Clough (May 2013)

Aided by a mysterious, possibly magical dog named Shadow and by various

strangers, a seventeen-year-old with acute memory loss who calls herself

Blue makes a 500-mile trek to her childhood home, unaware of what she

has left behind.

The Testing by Joelle Charbonneau (June 2013)

Sixteen-year-old Malencia (Cia) Vale is chosen to participate in The

Testing to attend the University; however, Cia is fearful when she

figures out her friends who do not pass The Testing are disappearing. Kimberly's review

The Girl Who Was Supposed to Die by April Henry (June 2013)

She doesn't know who she is. She doesn't know where she is, or why. All

she knows when she comes to in a ransacked cabin is that there are two

men arguing over whether or not to kill her. And that she must run.

Follow Cady and Ty (her accidental savior turned companion), as they

race against the clock to stay alive.

Another Little Piece by Kate Karyus Quinn (June 2013)

A year after vanishing from a party, screaming and drenched in blood,

seventeen-year-old Annaliese Rose Gordon appears hundreds of miles from

home with no memory, but a haunting certainty that she is actually

another girl trapped in Annaliese's body.

Related StoriesThe Testing by Joelle CharbonneauSecret Historical Societies of Teenage Girls: A Brief ListNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin Hicks

Related StoriesThe Testing by Joelle CharbonneauSecret Historical Societies of Teenage Girls: A Brief ListNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin Hicks

Published on May 23, 2013 22:00

The reductive approach to YA

I'm surprised not more people have responded to the link I shared last week to the New York Times Book Review of Andrew Smith's Winger which spends a hefty chunk of the review discussing John Green and "Green Lit."

I've read Winger and I have read Looking for Alaska. Yes, both books are set in boarding schools. Yes, both books are narrated by male protagonists. Yes, both books are contemporary/realistic. Yes, both books are written by male YA authors.

But that's about where their comparisons end.

This post isn't about those two books and comparisons, though. It's about the fact we need to stop being so damn reductive in how we talk about YA books.

It wasn't too long ago when all associations to YA fiction came through Twilight. The joke was that all YA books were bad knock offs or were filled with sparkly vampires. When books like The Hunger Games came out, people took to it a little slower, skeptical because it defied some of the expectations of what YA lit was and wasn't -- Collins's book is no Twilight, so suddenly, the frame of reference shifted.

Now, of course, we're in the hey day of John Green mania. He's racked up almost every accolade possible, and everyone and their mother and their aunt and their uncle has read The Fault in Our Stars. It's GREAT that the world of YA grows as more people read it. And it's great that good, strong books are getting recognition and are getting recognition as books written for a young adult audience. No one is comparing John Green's oeuvre to Twilight because his books are "nothing like that." Even though Green writes for a YA audience and even though this book is being seen as an amazing contribution to YA from readers who'd otherwise eschew these books, many readers only have him as their frame of reference. That then limits their own view of YA and -- in this case -- contemporary realistic YA.

Going back to the New York Times review, AJ Jacobs, who is himself an adult non-fiction writer, talks in depth about all of Green's accomplishments. He's sold out Carnegie Hall. He's never off the NYT Best Sellers List. Even though he didn't "invent" realistic YA (that honor is given to JD Salinger who, I note, didn't even write books for young adults, let alone invent realistic YA), Green's books pretty much define contemporary realistic. Jacobs calls these books "Green Lit," and they're books featuring strong dialog with self-aware narrators who have crushes and deal with twists and disobey authority. Writers of realistic fictions are chasing the Green dream, as they want their books to do what it is his books do.

Here's the thing: not everyone wants to read a John Green book. Not everyone wants to write the John Green book.

Not every book that is set in our world, featuring authentic teen main characters is worth calling "Green Lit." Because the hallmark of good contemporary realistic fiction is authentic teen characters. They can be funny. They can be heart breaking. They can defy authority. They can fall in love or out of it. They can go to boarding school. They can suffer pain. It doesn't mean these characters, the readers who want these books, or the authors who write them, are all aiming for the Green dream.

Reducing an entire genre to one person's books as a source of comparison is limiting and reductive of the nuances, the depth, and the range of voices that exist within it. Believe it or not, John Green is not the be all, end all of contemporary realistic YA fiction. Many amazing authors came before him and wrote with goals to portray real characters in real world situations -- Laurie Halse Anderson, Judy Blume, SE Hinton, Robert Lipsythe, Paul Zindel, Robert Cormier -- and many amazing authors came after him and will continue to come after him. Yes, he has spent a long time on the NYT List. Yes, he's achieved a lot for having such a young career. Yes, he's easily recognized as one of the great YA authors. Yes, he's done a lot for the YA community.

But, he's one person who has written just a few books. He is not the definition of a genre, nor is he the definition of YA.

Comparisons among authors and books are inevitable. They're an important element of reader's advisory and they give grounding to new books and voices for readers who want to get a sense of a book's style. In short reviews, sometimes those comparisons to big, well-known authors is valuable -- it's a quick glance at what readers may like a book. But in an outlet like The New York Times, which is a big space with big readership, why is all of the richness of YA fiction reduced to a single name? And why is the review of Smith's novel really about Green's contributions to YA? Why is it written by someone who hasn't done their homework on the breadth of this field of work?

This chance to offer valuable insight into contemporary realistic fiction -- and insight into the broader spectrum of YA -- was a blown opportunity. It does service to no one.

I don't want to spend too much longer thinking or blogging about this, but I do want to raise a question to anyone willing to weigh in here. When we reduce YA to Twilight, it's meant as a sting and as a means of belittling the field. But when we reduce YA to John Green's books, it's meant as an ultimate compliment? Both authors have done exceptionally well. Both have appealed greatly to readers who are young adults and those who aren't.

Related StoriesGetting past the easy reach

Related StoriesGetting past the easy reach

I've read Winger and I have read Looking for Alaska. Yes, both books are set in boarding schools. Yes, both books are narrated by male protagonists. Yes, both books are contemporary/realistic. Yes, both books are written by male YA authors.

But that's about where their comparisons end.

This post isn't about those two books and comparisons, though. It's about the fact we need to stop being so damn reductive in how we talk about YA books.

It wasn't too long ago when all associations to YA fiction came through Twilight. The joke was that all YA books were bad knock offs or were filled with sparkly vampires. When books like The Hunger Games came out, people took to it a little slower, skeptical because it defied some of the expectations of what YA lit was and wasn't -- Collins's book is no Twilight, so suddenly, the frame of reference shifted.

Now, of course, we're in the hey day of John Green mania. He's racked up almost every accolade possible, and everyone and their mother and their aunt and their uncle has read The Fault in Our Stars. It's GREAT that the world of YA grows as more people read it. And it's great that good, strong books are getting recognition and are getting recognition as books written for a young adult audience. No one is comparing John Green's oeuvre to Twilight because his books are "nothing like that." Even though Green writes for a YA audience and even though this book is being seen as an amazing contribution to YA from readers who'd otherwise eschew these books, many readers only have him as their frame of reference. That then limits their own view of YA and -- in this case -- contemporary realistic YA.

Going back to the New York Times review, AJ Jacobs, who is himself an adult non-fiction writer, talks in depth about all of Green's accomplishments. He's sold out Carnegie Hall. He's never off the NYT Best Sellers List. Even though he didn't "invent" realistic YA (that honor is given to JD Salinger who, I note, didn't even write books for young adults, let alone invent realistic YA), Green's books pretty much define contemporary realistic. Jacobs calls these books "Green Lit," and they're books featuring strong dialog with self-aware narrators who have crushes and deal with twists and disobey authority. Writers of realistic fictions are chasing the Green dream, as they want their books to do what it is his books do.

Here's the thing: not everyone wants to read a John Green book. Not everyone wants to write the John Green book.

Not every book that is set in our world, featuring authentic teen main characters is worth calling "Green Lit." Because the hallmark of good contemporary realistic fiction is authentic teen characters. They can be funny. They can be heart breaking. They can defy authority. They can fall in love or out of it. They can go to boarding school. They can suffer pain. It doesn't mean these characters, the readers who want these books, or the authors who write them, are all aiming for the Green dream.

Reducing an entire genre to one person's books as a source of comparison is limiting and reductive of the nuances, the depth, and the range of voices that exist within it. Believe it or not, John Green is not the be all, end all of contemporary realistic YA fiction. Many amazing authors came before him and wrote with goals to portray real characters in real world situations -- Laurie Halse Anderson, Judy Blume, SE Hinton, Robert Lipsythe, Paul Zindel, Robert Cormier -- and many amazing authors came after him and will continue to come after him. Yes, he has spent a long time on the NYT List. Yes, he's achieved a lot for having such a young career. Yes, he's easily recognized as one of the great YA authors. Yes, he's done a lot for the YA community.

But, he's one person who has written just a few books. He is not the definition of a genre, nor is he the definition of YA.

Comparisons among authors and books are inevitable. They're an important element of reader's advisory and they give grounding to new books and voices for readers who want to get a sense of a book's style. In short reviews, sometimes those comparisons to big, well-known authors is valuable -- it's a quick glance at what readers may like a book. But in an outlet like The New York Times, which is a big space with big readership, why is all of the richness of YA fiction reduced to a single name? And why is the review of Smith's novel really about Green's contributions to YA? Why is it written by someone who hasn't done their homework on the breadth of this field of work?

This chance to offer valuable insight into contemporary realistic fiction -- and insight into the broader spectrum of YA -- was a blown opportunity. It does service to no one.

I don't want to spend too much longer thinking or blogging about this, but I do want to raise a question to anyone willing to weigh in here. When we reduce YA to Twilight, it's meant as a sting and as a means of belittling the field. But when we reduce YA to John Green's books, it's meant as an ultimate compliment? Both authors have done exceptionally well. Both have appealed greatly to readers who are young adults and those who aren't.

Related StoriesGetting past the easy reach

Related StoriesGetting past the easy reach

Published on May 23, 2013 09:19

May 22, 2013

May Debut YA Novels

Can you believe we're already more than five months into 2013? Some of us are still making our checks out to 2012 (how many ways can a person date herself in one sentence -- yes, I still use checks sometimes). We've been keeping track of this year's YA debut novels, and here are May's additions. As usual, all of these are by first time writers within in any genre or category, and all are traditionally published titles. Descriptions come from WorldCat, and as we review any of these titles during the year, we'll come back and link up our reviews.

If you know of other debut novels coming out in May, we'd love to know!

The Color of Rain by Cori McCarthy: If there is one thing that seventeen-year-old Rain knows and knows well, it is survival. Caring for her little brother, Walker, who is "Touched," and losing the rest of her family to the same disease, Rain has long had to fend for herself on the bleak, dangerous streets of Earth City. When she looks to the stars, Rain sees escape and the only possible cure for Walker. And when a darkly handsome and mysterious captain named Johnny offers her passage to the Edge, Rain immediately boards his spaceship. Her only price: her "willingness." Secretly and quickly Rain discovers that Johnny's ship serves as host for an underground slave trade for the Touched . . . and a prostitution ring for Johnny's girls. With hair as red as the bracelet that indicates her status on the ship, the feeling of being a marked target is not helpful in Rain's quest to escape. Even worse, Rain is unsure if she will be able to pay the costs of love, family, hope, and self-preservation.

Coda by Emma Trevayne: Ever since he was a young boy, music has coursed through the veins of eighteen-year-old Anthem -- the Corp has certainly seen to that. By encoding music with addictive and mind-altering elements, the Corp holds control over all citizens, particularly conduits like Anthem, whose life energy feeds the main power in the Grid. Anthem finds hope and comfort in the twin siblings he cares for, even as he watches the life drain slowly and painfully from his father. Escape is found in his underground rock band, where music sounds free, clear, and unencoded deep in an abandoned basement. But when a band member dies suspiciously from a tracking overdose, Anthem knows that his time has suddenly become limited. Revolution all but sings in the air, and Anthem cannot help but answer the call with the chords of choice and free will. But will the girl he loves help or hinder him?

The End Games T. Michael Martin: In the rural mountains of West Virginia, seventeen-year-old Michael Faris tries to protect his fragile younger brother from the horrors of the zombie apocalypse.

Nantucket Blue by Leila Howland: Seventeen-year-old Cricket Thompson is planning on spending a romantic summer on Nantucket Island near her long time crush, Jay--but the death of her best friend's mother, and her own sudden intense attraction to her friend's brother Zach are making this summer complicated.

Reboot by Amy Tintera: Seventeen-year-old Wren rises from the dead as a Reboot and is trained as an elite crime-fighting soldier until she is given an order she refuses to follow.

Riptide by Lindsey Scheibe: While training for a surfing competition to earn a college scholarship, Grace Parker struggles with her feelings toward her best friend Ford Watson and tries to conceal her family's toxic dynamics.

Out of This Place by Emma Cameron: Luke divides his time between hanging at the beach, working at the local supermarket, and trying to keep out of trouble. Bongo, his mate, gets wasted to forget about the brother who was taken away from his addict mom and his abusive stepdad. Casey, the girl they love, looks to leave her controlling dad and find her own path. But after they leave and move onto very different lives, can they leave behind the past? And will they ever see each other again?

Parallel by Lauren Miller: A collision of parallel universes leaves 18-year-old Abby Barnes living in a new version of her life every day, and she must race to control her destiny without losing the future she planned and the boy she loves.

The Rules for Disappearing by Ashley Elston: High school student "Meg" has changed identities so often that she hardly knows who she is anymore, and her family is falling apart, but she knows that two of the rules of witness protection are be forgettable and do not make friends--but in her new home in Louisiana a boy named Ethan is making that difficult.

Firecracker by David Iserson (from Goodreads): Being Astrid Krieger is absolutely all it's cracked up to be. She lives in a rocket ship in the backyard of her parents' estate. She was kicked out of the elite Bristol Academy and she's intent on her own special kind of revenge to whomever betrayed her. She only loves her grandfather, an incredibly rich politician who makes his money building nuclear warheads. It's all good until..."We think you should go to the public school," Dad said. This was just a horrible, mean thing to say. Just hearing the words "public school" out loud made my mouth taste like urine (which, not coincidentally, is exactly how the public school smells). Will Astrid finally meet her match in the form of public school? Will she find out who betrayed her and got her expelled from Bristol? Is Noah, the sweet and awkward boy she just met, hiding something?

Truth or Dare by Jacqueline Green: In the affluent seaside town of Echo Bay, Massachusetts, mysterious dares sent to three very different girls--loner Sydney Morgan, Caitlin "Angel" Thomas, and beautiful Tenley Reed--threaten both their reputations and their lives. Kimberly's review.

Wild Awake by Hilary T Smith: The discovery of a startling family secret leads seventeen-year-old Kiri Byrd from a protected and naive life into a summer of mental illness, first love, and profound self-discovery.

How My Summer Went Up in Flames by Jennnifer Salvato Doktorski: Placed under a temporary retstraining order for torching her former boyfriend's car, seventeen-year-old Rosie embarks on a cross-country car trip from New Jersey to Arizona while waiting for her court appearance.

The Summer I Became A Nerd by Leah Rae Miller (from Goodreads): On the outside, seventeen-year-old Madelyne Summers looks like your typical blond cheerleader—perky, popular, and dating the star quarterback. But inside, Maddie spends more time agonizing over what will happen in the next issue of her favorite comic book than planning pep rallies with her squad. That she’s a nerd hiding in a popular girl's body isn’t just unknown, it's anti-known. And she needs to keep it that way. Summer is the only time Maddie lets her real self out to play, but when she slips up and the adorkable guy behind the local comic shop’s counter uncovers her secret, she’s busted. Before she can shake a pom-pom, Maddie’s whisked into Logan’s world of comic conventions, live-action role-playing, and first-person-shooter video games. And she loves it. But the more she denies who she really is, the deeper her lies become…and the more she risks losing Logan forever.

The Falconer by Elizabeth May (Goodreads): 18-year-old Lady Aileana Kameron, the only daughter of the Marquess of Douglas, was destined to a life carefully planned around Edinburgh’s social events – right up until a faery kills her mother. Now it’s the 1844 winter season. Between a seeming endless number of parties, Aileana slaughters faeries in secret. Armed with modified percussion pistols and explosives, every night she sheds her aristocratic facade and goes hunting. She’s determined to track down the faery who murdered her mother, and to destroy any who prey on humans in the city’s many dark alleyways. But she never even considered that she might become attracted to one. To the magnetic Kiaran MacKay, the faery who trained her to kill his own kind. Nor is she at all prepared for the revelation he’s going to bring. Because Midwinter is approaching, and with it an eclipse that has the ability to unlock a Fae prison and begin the Wild Hunt. A battle looms, and Aileana is going to have to decide how much she’s willing to lose – and just how far she’ll go to avenge her mother’s murder.

Maid of Secrets by Jennifer McGowan: In 1559 England, Meg, an orphaned thief, is pressed into service and trained as a member of the Maids of Honor, Queen Elizabeth I's secret all-female guard, but her loyalty is tested when she falls in love with a Spanish courtier who may be a threat.

The S-Word by Chelsea Pitcher: Angie's quest for the truth behind her best friend's suicide drives her deeper into the dark, twisted side of Verity High.

Zenn Scarlett by Christian Schoon (from Goodreads): Zenn Scarlett is a resourceful, determined 17-year-old girl working hard to make it through her novice year of exovet training. That means she's learning to care for alien creatures that are mostly large, generally dangerous and profoundly fascinating. Zenn’s all-important end-of-term tests at the Ciscan Cloister Exovet Clinic on Mars are coming up, and, she's feeling confident of acing the exams. But when a series of inexplicable animal escapes and other disturbing events hit the school, Zenn finds herself being blamed for the problems. As if this isn't enough to deal with, her absent father has abruptly stopped communicating with her; Liam Tucker, a local towner boy, is acting unusually, annoyingly friendly; and, strangest of all: Zenn is worried she's started sharing the thoughts of the creatures around her. Which is impossible, of course. Nonetheless, she can't deny what she's feeling. Now, with the help of Liam and Hamish, an eight-foot sentient insectoid also training at the clinic, Zenn must learn what's happened to her father, solve the mystery of who, if anyone, is sabotaging the cloister, and determine if she's actually sensing the consciousness of her alien patients... or just losing her mind. All without failing her novice year. Kimberly's review.

The Beautiful and the Cursed by Page Morgan: Residing in a desolate abbey protected by gargoyles, two beautiful teenaged sisters in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Paris discover deadly and otherworldly truths as they search for their missing brother.

Transparent by Natalie Whipple: Sixteen-year-old Fiona O'Connell is the world's first invisible girl, which makes her the ideal weapon for her crime-lord father. But now, she and her mother have escaped and are hiding out in a small town where they're determined to start a normal life.

Related StoriesApril Debut YA Novels

Related StoriesApril Debut YA Novels

Published on May 22, 2013 22:00

May 21, 2013

The Testing by Joelle Charbonneau

Cia lives in Five Lakes colony, the region of the country that used to be the Great Lakes, but is now a blighted region thanks to the Seven Stages War, a terrible conflict that killed millions and left most of the world environmentally destroyed. The United Commonwealth is now focused on revitalizing the country, clearing out the deadly toxins from the water and forcing the Earth to grow food again.

To do this, the country needs leaders. When they graduate from school at 16, all children become eligible for the Testing, a series of rigorous tests that determine entry into the the country's (apparently only) college. Cia is one of the select few chosen to compete. She has no choice in the matter, but she's happy to go; she knows it's the only way to get into college and she's eager to help lead the healing of the Earth.

But the Testing is not what it seems. Before she leaves, Cia's father - who participated in the Testing - tells her that though all participants' minds are wiped of memories of the Testing to ensure no inside information can be given to others, he's been plagued by disturbing half-memories. He remembers violence, death, terrible things children did to each other. He warns Cia not to trust anyone. He tells her that most people who go to the Testing - the ones who don't pass - aren't ever seen again.

So, does this synopsis sound familiar to you? It should - it's basically the Hunger Games. And I don't mean that in the way Divergent or Legend are like the Hunger Games. Those two books certainly have strong similarities, but The Testing takes it to a whole new level. The bulk of the book involves, unsurprisingly, an arena-like test where the teens must make it from one part of the blighted country (human-made obstacles included) to another, and only a certain number who make it will be admitted. They quickly learn that it's to their advantage to thin the herd. There's also another boy from her colony who Cia may or may not have a crush on, but can she trust him? Is his affection just a clever ruse?

I think it's interesting that Kirkus (usually the more unforgiving of review journals) claims that Charbonneau "successfully makes her story her own." I don't agree with that statement completely. It's not a carbon copy, but the aspects that are similar are eerily similar, in a way that seems to verge worryingly close to theft. I realize this is a pretty strong statement, and I thought a long time about how I'd remark on it. I felt it was important to share, though, so there you have it.

Despite all of that, though, this is a fantastic book. I know. If the Hunger Games didn't exist and I'd never read it, I'd be shouting this book's praises all over the place. But the Hunger Games does exist, I have read it, and The Testing owes so much to it (including its very existence, most likely). We don't read in a vacuum, and I can't and shouldn't pretend that we do. But I also feel it's important to judge a book on its own merits without necessarily comparing it to something else, and on its own, this book is fantastic.

Actually, I liked it more than the Hunger Games, which I enjoyed but didn't love immediately. I found the premise of the Hunger Games a little harder to believe and its depiction of the terrible things adults force upon the children in their care a bit heavy-handed. The Testing couches its violence in something that I think is more immediately relatable to teens - the competition for admittance to college - and shows the consequences of what we do to our children (intentionally or not) in a slightly more nuanced way.

Enough with the Hunger Games comparisons, though. The Testing affected me in a visceral way, and I can honestly say that no other book in recent memory has gotten my heart rate going quite like this one has. I resented having to go to work in the morning because all I wanted to do was read this book. Charbonneau is a master of suspense, of creating tension so taut that it hurts to keep reading but hurts just as much to stop. I wanted to turn the pages faster, faster, but at the same time I had to force myself to slow down because I didn't want to miss a single word. This is the kind of book that makes readers bite their fingernails until their fingers bleed, tug bits of hair out, shout at their significant others to leave them alone because goddammit they are reading, can't you see?

Beyond that aspect, there are some truly creative things going on here. I found the tests prior to the main survival round hugely interesting and quite unique in their own right, particularly the third round one involving teamwork. It's a great example of some creative plotting as well as character-building, and is the first real opportunity we get to see how ruthless children can be. The way Charbonneau gradually moves the tests from completely innocuous to more and more sinister is masterfully done.

The Testing does have its weaknesses. Cia isn't a hugely memorable character (though neither is she flat). There's not much background about the Seven Stages War, which is something that frustrates me in any dystopia I read. Some elements of the plot are easy to see coming - betrayals, alliances, deaths. Still, Charbonneau throws in enough twists to keep readers thoroughly engrossed, and like I mentioned before, it's nearly impossible to stop reading it once you start.

So, obviously, this is a perfect book for your fans of the Hunger Games and other action-packed dystopias. I'd love to discuss it with other readers and get their views on its similarities. This is one I see people having very strong reactions to one way or the other. For myself, I'm really looking forward to the sequel.

Review copy received from the publisher. The Testing will be published June 4.

Related StoriesNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin HicksThe Lucy Variations by Sara ZarrIn the Shadow of Blackbirds by Cat Winters

Related StoriesNothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen & Faith Erin HicksThe Lucy Variations by Sara ZarrIn the Shadow of Blackbirds by Cat Winters

Published on May 21, 2013 22:00

May 20, 2013

30 Days of Awesome: Using My Platform Positively

design by John LeMasney via lemasney.com

What began as a way to keep track of my thoughts on books has turned into something much bigger than I ever anticipated. And for a long time, I made a point to be very careful about sharing anything non-book related and I still take great effort to avoid talking about personal stuff here. This is and will always be primarily a blog about books and reading. Because those are two big passions in my life.

As STACKED has grown over the last four years, though, I've also seen myself growing as a blogger and as a thinker. I talked about this a my post last month and I've thought about it a lot in terms of what personal stuff I'm more willing to put out there now. I've talked a lot about speaking up and out as a woman, and I've talked about being an introvert, among other things. I've talked about how females are depicted on book covers and how there aren't gendered spaces.

Yet the post I feel changed everything for me in terms of blogging was this one. When I spoke up about ARCs, suddenly I found this little blog about books and reading being responded to in other blogs, both those within librarianship and those outside of it. It was the post that riddled me with a lot of guilt, then frustration, sadness, then anger. I was mad and upset about how my words were read and twisted. It hurt how people responded to me in a personal manner -- as if my career and personal life choices and decisions were things that factored in to what I had said in one single post.

After sitting on what I'd put out there for a couple of weeks, and thinking about how my piece had spawned reaction, I realized something big.

I had a platform.

People were listening.

Rather than rest on posting, though, I figured out that using this platform as a means to speak out was just the first step. I needed to use what I had in order to implement change. If something like ARCs could spur such heated discussion and rile up the sort of response it did, maybe I was on to something. So I put those thoughts and that post into action, suggesting a panel for the American Library Association's conference on the topic. It was accepted, and now we're in the process of organizing over 500 responses to our survey on how librarians, booksellers, and others use Advanced Reader's Copies so we can talk about why they're valuable and how they're used in the book world.

Anyone who has spent time here knows I've talked about being a woman and the challenges of speaking up and out over the last year too. That, whether you know it or not, came about because of my ARC post. Because of how people responded to that particular post and the thoughts I'd shared in the after. But when other people started talking about being a woman and the challenges of recognition for achievements on the ground level in libraries, it hit me that this is not just something that impacts me. It's something much bigger.

But.

I could use my platform here to highlight the awesome things that other people are doing. That I could use this position to respond to and showcase those things that other librarians, teachers, other book and reading advocates were talking about that were interesting. Even if I didn't necessarily agree with it. The value exists in bringing attention to those things which provoke response and provoke thought.

That is part of what brought this "30 Days of Awesome" series into existence in the first place. Rather than continuing to just link to cool things people were putting out there, I worked with Liz and Sophie to put together a coordinated effort that asks people to talk about those very cool things they're doing. To shine a light on themselves and brag. Because it's not just about saying "look at the things I'm doing." It's about also saying "here is how you can do it, too."

Realizing I had a platform and that people were listening to me changed my perceptions of blogging and changed my perceptions of what it is I can contribute to the blogging and blog reading world.

Wil Wheaton wrote a blog post a couple of weeks ago that I've been thinking about and that ultimately made me figure out what it is I wanted to contribute as my own piece for this project: "They make comments." Being at the center of two weeks of comments regarding the ARCs post, where people chose to spin my words and meanings into every possible formation, made me realize that it is a lot easier to make a comment than it is to take ownership of creating something larger -- even if that something "larger" is a blog post. Because it's out there, and it's permanent.

No doubt, people haven't liked other things I've blogged about. My post on introversion brought out a pretty nice series of anonymous commenters. I've seen tweeting and subtweeting pop up on any number of other posts I've written that shared a real piece of who I was in them. I've seen people choose to call me out on silly things left and right. Yes, they get to me a lot. I'm surprisingly sensitive. But thinking about what Wheaton's post said -- I've made something. They've made comments.

It's not just about making something in this virtual space though. It's about taking this virtual space and allowing this platform to be a way to do more. To reach new and different audiences. To allow other people a chance to have their voices and opinions heard. To meet new people.

To share.

While I may blog about things people disagree with -- and I always welcome an intelligent discussion -- I'm trying to keep in mind that my blog is something I get to make a choice about since it's my platform and my voice.

I choose this to be a space dedicated to being critical, to being thoughtful, to being helpful, and to actively pursuing my passions. It's so much more enjoyable to lift people up than it is to knock them down. And if I am in the position to do the first, I want to do just that.

Published on May 20, 2013 22:00

May 19, 2013

So You Want to Read YA? Guest Post by Amy Stern, Literary Agent

This week's contribution to So You Want to Read YA? comes from literary agent Amy Stern.

Amy Stern is currently an assistant agent at the Sheldon Fogelman Agency. She taught science fiction and fantasy at the Simmons College Center for the Study of Children's Literature, where she also got her MA in children's literature and her MLS in library science. She is occasionally pretentious about children's literature on her twitter @yasubscription and her blog yasubscription.wordpress.com. She reads a lot about superheroes, watches a lot of reality television, talks a lot about problems with gender normativity in popular culture, and spends entirely too much time on the internet.

We talk a lot about finding the "right book at the right time for the right reader" when we're talking about getting things for other people to read. I don't think that we give it nearly as much thought when we're choosing what to read ourselves. We are people who crave good stories, and then talk about them on the internet. We are the opposite of the reluctant reader.

One of the hardest things I've had to do- as an agent, as a scholar, and perhaps most importantly as a person who loves stories- was come to terms with the fact that I can't actually separate myself from the books I read. I can recognize the artistry and skill that goes in to telling a story without loving it; conversely, I can recognize there are parts of a novel that are deeply flawed while still connecting with it on a deep visceral level. But I will always see the best stories as the ones that combine those two for me, and that's inherently subjective.

So for this blog post, I didn't choose what I think of as the "best" novels by some kind of arbitrary external standard that probably doesn't really exist. And I didn't choose my favorites, because that's more an exploration of my id than young adult as an overall category. Instead, I'm taking this opportunity to look at twelve novels that made me reexamine my own criteria for what makes YA something worth taking another look at- books that were the right book at the right time for me as a reader, and why each of them struck when they did.

A HOUSE LIKE A LOTUS by Madeleine L'Engle

The first time I read the novel, I didn't get it. I mean, I really didn't get it. I was in fifth grade, and I just kind of passed over the parts that didn't fit into my world view. Looking back, I'm not sure how I got anything out of it without all of those parts, but I did have that emotional connection that made it one of my favorite books. A HOUSE LIKE A LOTUS is about Polly, a teenaged girl struggling with her understanding of the world in both practical and abstract ways. When I was older and reread the novel, I was stunned by how much of the world she discovers; the novel explores- sometimes delicately, sometimes clumsily- sex and sexuality, childhood and adulthood, belief and betrayal.

If you're familiar with L'Engle's work, it's hard to separate LOTUS from the context of L'Engle's other books. Polly is the daughter of Meg and Calvin, two of the protagonists of her Newbery-winning A WRINKLE IN TIME. This is never brought to the forefront, but it's a constant undercurrent; if you're familiar with L'Engle's Time Quartet, the characters will ring very familiar. And it's through that lens that it hits so hard when Max, Polly's brilliant but troubled mentor, points out that Polly's mother is unhappy.

Lots of young adult books deal with the complexity of realizing that the adults in your life have as many conflicting emotions as you do, but this was the first novel where I couldn't escape the fact that the adult in question was a grown-up version of a teen protagonist I'd identified with. She hadn't just grown up and lived happily ever after; she'd made choices, and those choices had consequences, both good and bad. A HOUSE LIKE A LOTUS is Polly's story, but when I remember it, I think about how Charles Wallace is off on a secret mission and Calvin is performing cutting-edge surgery on animals and Sandy is an international diplomat and Meg is at home, helping with Calvin's research and not getting her PhD because she doesn't want any of her seven kids to feel "less than," the way she did compared to her own mother.

A HOUSE LIKE A LOTUS isn't the book that introduced me to intertextuality, but it's the one that taught me- many years after my first read- that a series of books can be more than the sum of its parts.

EVIL GENIUS by Catherine Jinks

First, a word of warning: this novel starts when Cadel is seven and ends when he's a young teenager. But this is not a middle grade novel. This is the first novel in a trilogy, and by the third book Cadel matches up to the age we expect in a YA novel, but this is not Harry Potter. There isn't sexual content, and the violence isn't horribly explicit, but a nine-year-old isn't going to get much out of this. I'm 28 and some of the sociological and scientific concepts the book covers confuse me.

That said, this book is totally worth the time and effort it takes.

I love stories about giftedness, but hate stories about smart kids whose intellect is rivaled only by their failure at basic social interactions. As an awkward, nerdy kid who both had friends and liked spending time alone, I resented the idea that academic talent was inextricably linked to wanting desperately to belong and falling flat. When a friend gave me a copy of EVIL GENIUS and told me I'd love it, I cringed, but decided to give it a shot. And the book did the impossible, by turning that plot I hate into something I deeply care about.

Cadel's genius lies largely in understanding complex systems, and he views everything as yet another case study. Being raised by not-terribly-well-meaning adults who are trying to make him the best super villain he can be does not increase his empathy. He doesn't interact with other kids much, and while he may be lonely, he doesn't have any real desire to be part of their world. He simply views them as gears in the larger machinery, and the story- told in close third person- allows the reader to see this as logically as he does. When Cadel slowly develops empathy, it feels earned, and we see that his intelligence wasn't at all a blockade to connecting to other people. In fact, he's able to use it as a bridge.

EVIL GENIUS is my reminder that there's no story out there that's been done to death, because there are always new angles making something old fresh. If that angle is supervillainy, so be it.

ON THE JELLICOE ROAD by Melina Marchetta

For context here, I have to explain that I am a pretentious jerk who desperately wants to be well-read enough that when the ALA awards are announced every January, I say "Oh, I read that" and promptly begin arguing whether or not the best story won. Some years, I get more into this goal than others.

The year JELLICOE won was probably the height of my commitment to this completely asinine goal. I basically stopped sleeping in favor of reading a YA novel every night. I read all of the prediction blogs, and used them to make lists that I took to libraries and bookstores. I started to get YA lit fatigue; each book I read started to feel more like a chore than a treat, and I was so stressed about reading what would win that I wasn't registering the individual stories as much besides items to check off on a list. The day before the ALA awards were announced, though, I decided that if I hadn't read it yet, I wouldn't have read it. I'd read something for fun- something to relax. And I'd really liked SAVING FRANCESCA, so I figured I'd give this book I'd picked up on a whim a shot. Instead, JELLICOE wrenched me apart, and then it put me back together again.

I could talk for days about the ways JELLICOE uses various literary techniques to build an outstanding story, one which stands up even better on second read than on first. Structurally in particular, JELLICOE does what I love most in a novel: even unrelated parts parallel each other, adding depth, by the end, every aspect of the story feels complete and whole, without a beginning or an end; this is a Moebius strip of a novel. Nothing is extraneous; every piece has emotional or plot payoff, if not both, and even as the story comes full circle, so does the reader, as the appreciation of each part snowballs in the context of the pieces around it.

But more than anything, JELLICOE is a novel about the power of stories and of storytelling that also recognizes how things which help you heal are often the ones that hurt the most. None of its answers are easy, and that makes all of its answers, both good and bad, feel honest. And what matters most to me is that I found all of that in the story, not when I was looking at it with the lens of "will this win an award?", but rather when I just sat down and let myself drown in it. When I got myself to a place where reading YA novels felt like work, JELLICOE reminded me why I choose to read in the first place.

HOUSE OF STAIRS by William Sleator

I love a good dystopia as much as the next YA aficionado, but I have to admit that every time I read one, my evaluation of it butts up against my feelings on this book. Nearly all of HOUSE OF STAIRS takes place in a single room, with only five characters. The novel is short, under 200 pages. The teenagers feel contemporary, but small details pop up which feel incongruous to what we know of our world. Gradually, the reader realizes how disturbing the world of HOUSE OF STAIRS is.

Everything about this novel is surprising, but in a way that's earned; once you've read it, you'll see how much all of the groundwork was expertly laid while you weren't looking. My favorite part, though, is how the characters subvert stereotypes. I'm almost afraid to say more, because it gives away too much, but reading the novel there's a sense of "Oh, I know all of the pieces in this game" that slowly dissolves as you realize you know nothing about this world- just like the characters! (Yeah, shit gets deep in this book.)

This is not a perfect book. On my most recent reread, I was horrified by the fat politics of the story; additionally, when you step back, the overall plot has some holes you could drive a truck through. But even when I was appalled or disbelieving, I never considered putting the book down; it's that gripping. HOUSE OF STAIRS is my reminder that

YA isn't about the biggest concept or the most ostentatious plot; a young adult novel is discovering more of your world, and that can be as big as the universe or as small as a single room with nothing but endless staircases.

DOING TIME: NOTES FROM THE UNDERGRAD by Rob Thomas

Like most librarians and publishing people on the internet, apparently, I saw Veronica Mars when it aired, fell in love, and immediately tracked down Rob Thomas's YA novels. But I wasn't just a quitter who stopped at RATS SAW GOD, or even SLAVE DAY. Oh no. I tracked down all of them. And while I understand why RSG was everyone's favorite, there will always be a special place in my heart for DOING TIME.

DOING TIME: NOTES FROM THE UNDERGRAD is not technically a short story collection, but it feels like it; after the introductory chapter, each story is a first-person account from the perspective of a different kid completing their school's mandatory volunteer hours. Nothing about this should work, but somehow it all fits together. When you hear the summary RATS SAW GOD, you say "Yes, this sounds fascinating and it definitely should work." When you hear the summary of DOING TIME, you say "what the fuck? Are you at all familiar with the young adult market?" But the miracle of this book is that each story is successful, on its own and as a part of a larger whole.

Objectively (or as objectively as anyone can when talking about literature), this isn't Rob Thomas's best book. It's self-consciously edgy, and some pieces feel like they're just present for the sake of controversy. While every story in the collection works, some are much more successful than others, and the stories aren't long enough to make me believe every character. DOING TIME isn't a book I can get lost in. But it is a reminder that in the right hands, even the craziest concepts can work.

EMPRESS OF THE WORLD by Sara Ryan

There are queer novels that function primarily as Queer Novels. They are fundamentally about gayness; they are important in our canon because rather than shying away from queer relationships they dive into them headfirst. These novels are important; they pave the way. But they pave the way for books which have queer themes and queer characters but aren't fundamentally ABOUT queerness, books that are primarily about characters discovering who they are, and if part of that is their sexuality, that isn't the whole. EMPRESS OF THE WORLD was the first queer novel I read that wasn't a Queer Novel, and I fell in love with it.

I can't pretend I wasn't predisposed to liking this. EMPRESS is about a group of teens at a summer camp for gifted students, and two of them- both girls- fall for each other. This is basically a checklist of things that would make me fall in love with a story. But EMPRESS uses all of these elements as a starting point, rather than the goal. There are both straight and queer romances in this novel, and obviously those are the focus, but what grabs me is the group's immediate deep friendship, the kind that you only develop at summer camp. I knew enough of the concept to expect, going in, that we'd see characters explore their sexualities, but what struck me even more the first time I read it was that this book had non-white and non-Christian characters, just as a matter of course.

Sexuality, race, and religion are all just factors in the greater task of exploring who these characters are as human beings, and no one part of their identities exists in a vacuum.

EMPRESS OF THE WORLD is the story that reminds me a novel is only as strong as the relationships that form its foundation, and world building is only as strong as the people inhabiting that space.

[Note that may or may not be necessary: I'm using "queer" here as a catch-all term for QUILTBAG- queer, uncertain, intersex, lesbian, trans*, bisexual, asexual, gay.]

THE ABSOLUTELY TRUE STORY OF A PART-TIME INDIAN by Sherman Alexie

This is not a book I would recommend if you're interested in young adult literature. This is a book I'd recommend if you live in the world.

A lot of these books I have a single explanation for, a specific thing that makes it special. The closest I can come with this book is that, while Junior is clearly the protagonist and we are definitely rooting for him, there isn't anyone I'd identify as straight-up villain. There are antagonists, but everyone is complex and human, and characters who do awful things also show complexity when you least expect it. This is a universe filled with people who behave like people, and through all the plot twists and turns, the novel never loses sight of how the root of every action is in real humans beings.

One of my golden rules for exceptional novels is that you should genuinely believe that, outside of the protagonist's point of view, every single character has a full life and is living out their own complex thematic arc that occasionally happens to intersect with the main character's. For me, this novel is the gold standard in that.

AFTER TUPAC AND D. FOSTER by Jacqueline Woodson

Jacqueline Woodson's novels tend to exist in the space between middle grade and young adult, and judging by the Newbery honor it got, I know that most people would classify this one as middle grade. The characters are only twelve, and while I'm sure some parts of the plot could be seen as "edgy," the three girls in this story are constantly aware of the dangers of the world without ever succumbing to them.

What makes this novel YA for me, though, is how much the story exists on a precipice. Neeka, D, and the narrator (she's never named) see all around them what growing up means- both becoming a teen and becoming an adult- and they're simultaneously desperate to make that jump and determined to stay where they are. What makes AFTER TUPAC AND D FOSTER exceptional, for me, is that it manages this without ever being nostalgic. The text doesn't romanticize adulthood, childhood, or adolescence. And that choice makes the emotional impact more, rather than less, because every development feels achingly real.

I've known for a while that young adult literature shouldn't be nostalgic, but this novel is what I look toward when I think about how that doesn't mean it can't remember the beautiful moments and the terrible moments that you don't always notice when you're in the middle of them.

NORTH OF BEAUTIFUL by Justina Chen

Mixed-media is my favorite style of art. I'm constantly amazed at what can be done with collage, using several different materials to create something that's more than the sum of its parts. But I'm always suspicious of art in literature. Too often, it's just there because the writer and much of the target audience (I include myself in this!) views a creative outlet as a necessary part of existing. Art needs to be used deftly, I think, to capture the idea that the act of creating isn't just a source of joy. It's also frightening, and that's part of what makes it so valuable.

The protagonist of NORTH OF BEAUTIFUL, Terra, loves working on collages even as she denies being an artist. Throughout the novel, she evaluates her circumstances in the context of her art. Her father doesn't support her art, and she doesn't have much faith in it herself, but at the same time, it shapes her world view. Terra is self-conscious about the birthmark on her face, and she uses her art to discover her own definition of beauty. She slowly learns to view each piece of her life as one item in a larger collage, and at the same time, to view her collages as things worthy of being seen and appreciated by others. Throughout this, though, the novel admirably refrains from hitting the reader over the head with the symbolism of collage. Terra is allowed to slowly discover how her art and her worldview are related, while rarely explicitly spelling it out.

NORTH OF BEAUTIFUL is about a lot of things. It's about geocaching; it's about living up to expectations; it's about unrealistic standards of beauty. All of those are probably more central to the plot than the motif of artwork. But none are more important to me. When I think about this novel, I think about the excitement and terror of destroying things to make new and better things, and how expertly that's woven into the text- one of many pieces that contributes to the novel being more than the sum of its parts. It's really difficult to integrate symbolism in a way that feels honest to the reader and realistic in the text, and it's to this book's credit that it pulls it off so well.

BLEEDING VIOLET by Dia Reeves

I love and hate books about mental illness in equal measure. I love them because I think, done right, they're some of the most brutally honest reflections on what it means to be a person. I hate them because, so often, a character is reduced to a stereotype of a disorder, and that stereotype is the plot of the story as well as the whole of what passes for personality.

Hanna identifies as bipolar. But that isn't all she is. Even though she's clearly unbalanced, far beyond bipolarity- within the first chapter we learn she talks to her father's ghost and she's probably killed someone- she's learned to allow herself to live a life that works for her, sometimes in ways that are incredibly detrimental but often in ways that show how people are fundamentally resilient. It isn't normal, but it's how she's learned to cope. So when she finds herself in the town of Portero, a town which is dangerously supernatural in ways no paranormal romance could prepare you for, she doesn't get frightened and leave. Her abrupt mood shifts and her tenuous grip on reality, which have hurt her in so many other places, help her adjust to a town where things change on a dime and the surreal is a fact of life. As a reader familiar with unreliable narrators, it's easy to place Hanna into that box, but that's as unwise as trusting Hanna completely. She's crazy, but she's also often right.

This is a bleak book. If you're squeamish, you don't want to read this. (And you especially don't want to read Dia Reeves's other book; compared to that, this is tame.) It's also a very disquieting reading experience. Much of the enjoyment in the book seems to stem from how much you believe Hanna, and how much you're willing to go along with her for the ride. I don't see this as a flaw with the writing, but rather a consequence of how successful the writing is. Hanna's psyche is dangerous, and getting tangled up in her mindset is unsettling. But that discomfort lends to the atmosphere of the book, and when I think about books with such strong character and voice that they can take me anywhere, BLEEDING VIOLET is the first that comes to mind.

HOUSE OF THE SCORPION by Nancy Farmer

In the same year, HOUSE OF THE SCORPION got a Printz honor, a Newbery honor, and the National Book Award medal. The year it won, my writing prof told me I'd get a lot out of reading it. I saw how long the novel was, saw the family tree at the beginning that told me how complex the story would be, and decided to ignore her advice. I didn't think any novel could be worth that much work. I was so, so wrong.

There are plenty of books for children and young adults about drugs, but very few are this nuanced. This isn't about the dangers of opium, or even of the drug trade; this is a novel about power and identity, and it uses contemporary issues to create a dangerous science-fiction world that feels terrifyingly plausible. From the first pages, we know Matt is the clone of a powerful dictator, who rules over a strip of land between the United States and what was once Mexico. Over the course of the novel, although the story goes deep, we are aware we're barely scratch the surface of what that means. We learn just enough to realize how many other layers lie just beneath.

Despite being blatant and even over-the-top about how terrible the world can be (there are multiple dystopias within the same universe, and the very idea of a place of safety is an illusion), HOUSE OF THE SCORPION is often quite subtle. It can achieve this because the novel is told from Matt's point of view. The novel can be terrifying, but while occasionally it's graphic, most of the true horror exists in the space between what Matt understands and what the reader does. When I want to remember how much authors can trust their audience to fill in the blanks, this is the text I return to.

WELCOME TO THE ARK by Stephanie S. Tolan

This book is a cheat to include on the list. I can't tell you what about it makes it good, or even that it really is good. What I know is that the first time I read this book I couldn't put it down, and that while the cover on my copy has fallen off, I refuse to replace it. This book is, for me, a marker in time and place; when and where I read it are as ingrained in me as the plot and the characters.

WELCOME TO THE ARK is ostensibly the first book of a trilogy (the third book still hasn't come out, and it's over ten years later), about two children and two teenagers who meet at an experimental group home within a mental institution. All four of them are extraordinarily gifted in different ways, and while alone each of them is isolated, they find themselves are able to connect with each other- and through that with the world- in ways which defy explanation. It's a mostly-realistic story that has fantasy elements; it is wish fulfillment for every kid who feels like there's no one in the world who sees the world as they do.

This is the book that reminds me that at the end of the day, the book that we need to read- whether or not we know why we need it, or even that we do- is a hell of a lot more important than any other standard we can place on the literature we read.

Related StoriesSo You Want to Read YA?: Guest Post from Author Cecil CastellucciSo You Want to Read YA?: Guest Post from Author Bryan BlissSo You Want to Read YA?: Guest Post by Kate Testerman, Literary Agent

Related StoriesSo You Want to Read YA?: Guest Post from Author Cecil CastellucciSo You Want to Read YA?: Guest Post from Author Bryan BlissSo You Want to Read YA?: Guest Post by Kate Testerman, Literary Agent

Published on May 19, 2013 22:00

May 17, 2013

Inspired by -- and Read Alikes to -- The Chocolate War

Now you've read The Chocolate War. What do you read next? Here's a short list with some suggestions for further reading. Some of these titles cover aspects of bullying. Some are about portraying the truth in the most honest and painful way possible. Some of them are about social dynamics and social truths. Some of them are all of the above.

Part of why I wanted to put together this short list is because a number of books that more recent YA readers have come to know were inspired by Cormier's classic, whether or not they were aware of it. In many ways, this book opened up a dialog about peer pressure, about conformity, and about the dynamics of relationships in high school in teen fiction and in teen lives.

All descriptions come from WorldCat. I'd love to know of other books you see as strong read alikes to The Chocolate War, and I'd also love to hear about books that were definitely inspired by Cormier's classic. Leave your thoughts in the comments!

Permanent Record by Leslie Stella: Being yourself can be such a bad idea. For sixteen-year-old Badi Hessamizadeh, life is a series of humiliations. After withdrawing from public school under mysterious circumstances, Badi enters Magnificat Academy. To make things "easier," his dad has even given him a new name: Bud Hess. Grappling with his Iranian-American identity, clinical depression, bullying, and a barely bottled rage, Bud is an outcast who copes by resorting to small revenges and covert acts of defiance, but the pressures of his home life, plummeting grades, and the unrequited affection of his new friend, Nikki, prime him for a more dangerous revolution. Strange letters to the editor begin to appear in Magnificat's newspaper, hinting that some tragedy will befall the school. Suspicion falls on Bud, and he and Nikki struggle to uncover the real culprit and clear Bud's name. Permanent Record explodes with dark humor, emotional depth, and a powerful look at the ways the bullied fight back.

What was most interesting to me in my read of Permanent Record was how many allusions to Cormier's classic were made. One of the teachers in Badi's new school wanted to use The Chocolate War as a classroom read, but in the end, decided not to. And rather than fight administration about using it, the teacher decided to forget about it all together. Which an interesting message to compare to what happened in Cormier's book. There's also Badi, who refuses to sell chocolates to raise money for student organizations at his new school. Though his resistance and reluctance is much more in-your-face than Jerry's ever was. There are some really fascinating aspects about identity in Stella's book, too. Badi has to take on a new name when he enters a new school, thus hiding his ethnicity. Jerry, in Cormier's novel, doesn't hide who he is in the least. These two books would make for an interesting discussion for how much they are similar -- but even more because of how much Badi and Jerry differ in their approaches to disturbing the universe.

The List by Siobhan Vivian: Every year at Mount Washington High School somebody posts a list of the prettiest and ugliest girls from each grade--this is the story of eight girls, freshman to senior, and how they are affected by the list.

Why The List as a read alike? Well, it sure seems inspired by Cormier's book in terms of bucking against school traditions. This book challenges the beauty myth and the tradition in Mt Washington High School which posts a list of the best looking and ugliest girls each year. This year's nominees each have an opportunity to give their views of the issue and readers get to experience what happens over the course of this week to the girls and to their peers. Does the list disappear? Do people learn about what beauty is and is not? If The Chocolate War were recast with all females, I think this one gets it pretty close. It's much less brutal, though, and much more internally and psychologically driven.

The Buffalo Tree by Adam Rapp: While serving a six-month sentence at a juvenile detention center, thirteen-year-old Sura struggles to survive the experience with his spirit intact.

I have to admit upfront I haven't read this book. But it came up for me as a strong read alike because it's a title that forces a main character to survive with his own sense of self and dignity while spending time in a place rapt with authority, power, and control. Knowing Rapp's writing style, I am confident it is unflinchingly honest. Anyone read this one? I think I'm going to pick it up sooner, rather than later.

The Mockingbirds by Daisy Whitney: When Alex, a junior at an elite preparatory school, realizes that she may have been the victim of date rape, she confides in her roommates and sister who convince her to seek help from a secret society, the Mockingbirds.

Why The Mockingbirds? Well, we have a boarding school setting with authority that's less interested in the best interests of the students and instead invested in the best face of the school and themselves. There's vigilante justice here, too, though in Alex's case, things pan out . . . a little bit better than they do for Jerry.

Twisted by Laurie Halse Anderson: After finally getting noticed by someone other than school bullies and his ever-angry father, seventeen-year-old Tyler enjoys his tough new reputation and the attentions of a popular girl, but when life starts to go bad again, he must choose between transforming himself or giving in to his destructive thoughts.

It's been a few years since I read Twisted, but what I remember noting is how it's a story about what it means to be a male. What the power struggles are and what the challenges of defining yourself as masculine are. These themes are definitely huge in The Chocolate War and Anderson's writing is, of course, not afraid to tackle the tough stuff.

Some Girls Are by Courtney Summers: Regina, a high school senior in the popular--and feared--crowd, suddenly falls out of favor and becomes the object of the same sort of vicious bullying that she used to inflict on others, until she finds solace with one of her former victims.

It's hard not to see the parallels between what happens in Summers's book about bullying and what happens in Cormier's. Except, this time it's about the power struggles among girls, rather than boys. It's brutal and honest, and there's not a hopeful ending or solid closure. Which is part of the honesty and part of Cormier's book, too. Summers also does a good job of showing both sides of how girls are nasty with one another -- the physical and the psychological.

The Tragedy Paper by Elizabeth LaBan: While preparing for the most dreaded assignment at the prestigious Irving School, the Tragedy Paper, Duncan gets wrapped up in the tragic tale of Tim Macbeth, a former student who had a clandestine relationship with the wrong girl, and his own ill-fated romance with Daisy.

Like the Rapp title, this isn't one I've had the chance to read yet. But by all reviews I've spent time reading, it sounds like the tight community within the school and the social tensions/politics would make this a strong read alike. Not to mention the history of tradition.

Sticks and Stones: Defeating the Culture of Bullying and Rediscovering the Power of Character and Empathy by Emily Bazelon: Bazelon defines what bullying is and, just as important, what it is not; explores when intervention is essential and when kids should be given the freedom to fend for themselves; dispels persistent myths about bullying; and takes her readers into schools that have succeeded in reducing bullying and examines their successful strategies.

I read this one but can't talk too much about it except to say it's one of the stronger non-fiction titles exploring teen bullying and brutality I've read. It's adult non-fiction but definitely has teen appeal, as it begins with three case studies of teens dealing with bullying in very different -- very painful and real -- ways.

I could add many more bullying books, but I'm not because I don't think that all bullying books are good read alikes to one another, nor are they all good read alikes to The Chocolate War. I am curious to hear, though, what you might think makes for a strong Cormier read alike or what books were clearly inspired by the classic.

Related StoriesThe Chocolate War by Robert CormierThe Chocolate War: A Cover Retrospective, Foreign EditionsGuest Post: Why The Chocolate War Matters by Angie Manfredi

Related StoriesThe Chocolate War by Robert CormierThe Chocolate War: A Cover Retrospective, Foreign EditionsGuest Post: Why The Chocolate War Matters by Angie Manfredi

Published on May 17, 2013 22:00

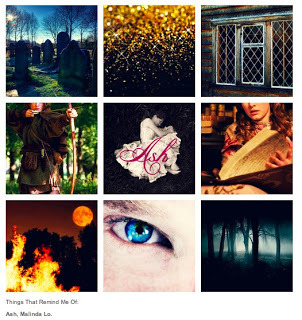

Links of Note, 5/18/13

I'm currently loving this series of "Things that remind me of" on this tumblr, and the image above is for the "Things that remind me of" for Malinda Lo's Ash. Spend a little time checking out all of the awesome posts here -- talk about a neat idea for visually thinking about books. I might have to try it.

This week's edition of Links of Note is short -- we've been collecting so many links for "30 Days of Awesome" and for the read and blog along to The Chocolate War. If you haven't spent time on either of those, you should.

If there's something I missed from the last couple of weeks worth knowing about, let me know.

Andrea Pinkney talks about diverse covers over at the CBC Diversity blog and calls for a love fest of favorite covers featuring the full faces or bodies of people of color.

At School Library Journal, there's a nice post about YA books you might have overlooked in the last couple of years. Interesting to me is the book that just came out being listed, only because it just came out. How could it already be overlooked? Either way, it's a good list.

Flavorwire has a fun post featuring the handwritten book outlines from well-known authors, including JK Rowling and Sylvia Plath.

Is it weird to include a post I helped write in the roundup? I'm going to anyway. Author Kathleen Peacock and I cowrote a piece about how piracy hurts libraries, authors, and readers. I talked specifically about how you can get books you want into your own library (and how piracy doesn't help that happen).

Hilary T. Smith, author of Wild Awake (which I have a review of coming in a couple weeks) has an interview with the designer of her book cover. This is a neat read!

A panel of authors on the question of likability. This is worth reading.

"Where are all of the funny YA books?" is a question I hate hearing. Sure, there's not necessarily a YA humor section but there are plenty of funny YA books. Lawrence Public Library in Lawrence, Kansas even made this awesome flowchart to funny YA.

This post is from earlier in May, but it resonated with me: what is the fate of the book blogger?