B.R. Sanders's Blog, page 40

December 9, 2013

RESISTANCE has a home!

Hey folks! I’m happy to announce that Resistance will be published by Inkstained Succubus press! I am honored to be part of their community of authors and super excited to be working with them on my debut novel! We are currently in the editing process, and Resistance is projected to be released in February 2014.

December 4, 2013

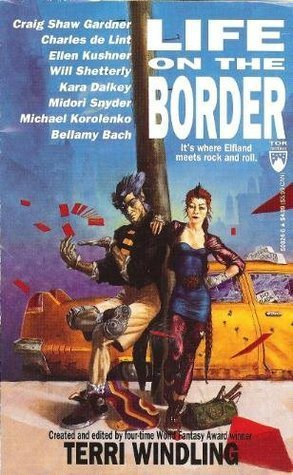

Book Review: LIFE ON THE BORDER

Life on the Border is the third installment of the Borderland series created and edited by Terri Windling. My reviews of the two previous volumes in the series are here and here. Life on the Border, like the two volumes before it, is an anthology of short stories by multiple authors set in a shared universe where Elfland has returned to the human world, bringing with it trade, unreliable magic and technology, and the elves. This volume is larger than the previous two and features new authors as well as familiar ones. But Life on the Border felt different from Borderland and Bordertown to me in a couple of important ways, both of which, I think, made it a stronger collection.

First, Life on the Border does a really excellent job capitalizing on the fact that it’s the third book in the series. The authors here dig deeper into the stories of characters who have come before, picking up threads and answering questions the other two volumes left behind. Bellamy Bach’s “Rain and Thunder,” for instance, revisits Gray, a character first introduced in Borderland who we last saw leaving the human world in the form of a cat. Stick and Koga, also introduced in previous volumes of the series, get a strange and unexpected shared backstory in Charles De Lint’s “Berlin.” And Will Shetterly starts Life on the Border with a Wolfboy story. The intertextual connections don’t stop there—Farrel Din alludes to the plot of “Prodigy” in this volume’s “Light and Shadow.” Characters who appear in one story within this volume, such as the curiously magical skateboarder Deki, show up again later. Altogether, this serves to create a sense of a real, living neighborhood. By using the groundwork laid by Borderland and Bordertown, this volume makes the reader feel more like they are coming home than venturing into some unknown place. Three volumes in and Bordertown has become a place where you know everyone’s name.

The other real strength of this volume is that it feels like it’s grown up with the reader. Borderland was published in 1986, and Life on the Border was published 5 years later in 1991. Where Borderland felt distinctively (and I believe intentionally) Young Adult in tone and content, Life on the Border feels much more adult. The first two volumes felt like the runaway’s honeymoon period; this volume feels like when the runaway really learns what town is like. The elves, for instance, have been flighty and tricky in previous volumes, but the elves in this volume especially are dark, mean creatures. Wolfboy runs into a particularly brutal batch of elves in the Nevernever who clearly see him as less than a person. Bordertown is plagued by an elvin monster in “Reynardine,” and it seems implied at the end of “Alison Gross” that Alison herself is an elvin witch since she’s banished across the border in Elfland. There is, again, the punishment meted out to Gray when the elves across the border find out she’s human. The protagonist of Ellen Kushner’s “Lost in the Mail” finds out the hard way that the theft of humans’ individuality is an elvin hobby when she lands in Oberon House—it’s a chilling, vampiric view of the elves that has stuck with me since I first read this volume years ago.

All in all, Life on the Border is the most cohesive volume in the Borderland series so far. Standouts for me in particular were “Nightwail” by Kara Dalkey, “Rain and Thunder” by Bellamy Bach and “Nevernever” by Will Shetterly. On the whole, I think the strengths of this book are lost if you haven’t read and loved the previous two volumes in the series, so I wouldn’t say it’s a stand-alone book or a particularly great introduction to the Borderland series, but it is an excellent extension of that series. I would have liked to see more insight into elvin culture—as I said, I appreciate the darkness of the elves here, but the book’s unrelenting focus on human stories could have been better balanced. It felt, a bit, like the book was written by the Pack—Bordertown’s staunchly human-only gang.

November 21, 2013

Stuck in Rewrite Mode

It’s hard to write the second half of a story when you’ve only ever written the first half. Extraction is done, and I’m working on its sequel, which I’ve tentatively titled The Incoming Tide. Drafting The Incoming Tide is a completely different experience than rewriting Extraction—as I mentioned in this post , Extraction brewed for years and was the fourth completely overhauled draft of the book. Extraction was a matter of writing the same story over and over; I knew what its themes were, and I knew where it needed to go before I ever sat down at the keyboard this time around.

The thing about The Incoming Tide is that it’s only ever existed as sketched-out worldbuilding notes. Because I’ve written past this moment in Aerdh’s history (notably in Ariah and sections of Sound and Song) I know how the story ends. And I have a fairly detailed outline worked out already. I know what I’m writing, but writing it the first time and writing it the fourth time are different experiences.

Since The Incoming Tide is yet in its infancy, it’s a strangely reflective process. According to my writing log*, I started The Incoming Tide on Halloween, which means I’ve been working on it for about three weeks. And I’ve made progress:

16k words in three weeks is not bad at all. Three chapters in as many weeks is nothing to smirk at. So, the writing is clipping right along. The thing about it is that I’m trying to work how how to write the story right along with what the story actually is. This two-headed discovery process characterizes first drafts for me, and sometimes it’s thrilling and sometimes it’s unnerving. This time, for whatever reason, it’s unnerving. I’m second-guessing everything—are these the right viewpoint characters? Is the pacing alright? I think I have to many plot threads going already and need to scale back; Extraction really crystallized as a book when I pared it down. Right now, the draft has two storylines working in parallel, and I think they could feasibly be split into separate books. But I like writing the characters in both! Argh.

The solution is simple, but it’s not all that easy: just keep writing. Just write it all and sort it out in the rewrite. Just write and write and write some more and get some fresh eyes on it to get it where it needs to be. Something about moving from a final iterative draft of Extraction to this completely new initial draft of The Incoming Tide has me doing something I haven’t done in years—it’s got me trying to approach a first draft like it’s the final draft. 16k words in and I’m still struggling to change my internal frame of reference.

*Spreadsheets for everything! It even has aggregation formulae and shit embedded in it!

November 18, 2013

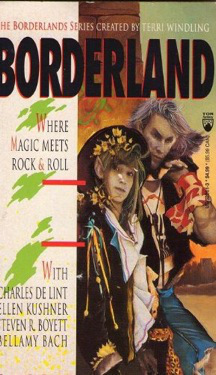

Book Review: BORDERLAND

Borderland is the very first installation in the series of the same name—a corpus of shared-world short stories and novels which collectively serves as a foundational text for the urban fantasy genre. Written in the 1980s, the books meld punk sensibilities and old-world high-fantasy glamour.

Borderland (this volume) is an anthology of four pieces of short fiction by Steven R. Boyet, Terri Windling writing as Bellamy Bach, Charles De Lint and Ellen Kushner. As with Bordertown, which I read and reviewed out of order, each of the stories serves as a conceptually self-contained aspect of the shared world. The stories are unified by setting—Bordertown, the city nestled between the Elflands and the human World. Three of the four stories as further connected through the youth of their protagonists and their occurrence in Bordertown’s history. The first of the set, “Prodigy”, bucks the trend: its protagonist, a formerly famous musician named Scooter, is notably older than many of the other POV characters scattered amongst the stories, and the story itself is set in the early years of Bordertown, likely some ten or fifteen years at least before the following entries.

As with any multi-author anthology, the mix of voices and approaches means your mileage will vary. The nature of shared-world creations means that inevitably a reader will find installments somewhat uneven. Taken as a whole, I think the stories in this collection are more polished than those in Bordertown—these stories have greater clarity, more concision in their language, and better consistency of perspective.

This volume spends more time than Bordertown exploring the fuzzy borders of magic, embodied and otherwise. In “Prodigy,” a man’s musical talent becomes a literal form of magic which rages through Bordertown. “Gray” tells the story of a runaway girl with strange magical abilities who trades her human street gang for the friendship of a well-meaning if vapid elf girl. While Gray toys with the problematic position of halfies in Bordertown, Gray is revealed to be fully human (though still in possession of magic). “Stick” confronts the precarious lives of halfies more directly—when Stick, Bordertown’s resident martial artist/vigilante, saves a halfie girl from a gang bet down, she ends up saving him in turn with the help of Farrel Din (an elvish wizard) and the Horn Dance (a rock band). “Charis” takes us up the Hill, to where the dignitaries and wealthy live. Here we get a glimpse of interworld politics when Charis, the naive daughter of two human politicians, gets dragged into a complicated elfin plot.

I especially liked “Gray” and “Charis” in this volume. The two stories pair well together, actually, working as sort of mirror images of what elf-looking human teenage girls in this world might do and deal with. “Stick” is a bit…optimistic for my particular taste, I think. And “Prodigy” fell quite flat with me. In both “Stick” and “Prodigy” the characterization could have been stronger. “Prodigy” also felt overly long for the story it told. But all in all, this book serves as a very strong introduction to Bordertown.

November 14, 2013

Book Review: SWORDSPOINT

Swordspoint, by Ellen Kushner, is a witty and unabashedly queer caper of a book. It is a quirky, quick thing full of precise violence and political intrigue written in a silvery voice. The book is low fantasy—set in a world that has never quite existed, but one which is thoroughly mundane and historically rooted; no magic or elves here, folks. The story follows Richard St. Vier, a half-crazy and meticulously genius swordsman for hire, his mysterious lover Alec, and the naive nobleman Michael Godwin as the three get swept into the subterfuge and deadly political games of the ruling class. There is honor in the book—it’s shot through with honor—but there’s no morality. Or what morality exists is aggressively gray. This is a book with no clear villains, just selfish people and ambitious people and callous people. It’s a book populated by very real people. This is a book that has some tricks up its sleeve: wonderful turns of phrase, pointed social commentary, and it’s a book packed to the brim with plot and plot twists.

Swordspoint has a deft hand in its treatment of both class and sexuality. The story moves repeatedly from high to low, up to the nobleman’s Hill and back down to Riverside. The realities and limitations of life in both cases are clearly drawn, and as the book goes on Kushner slowly reveals the deeply symbiotic relationship between the two classes. Richard St. Vier is the embodiment of this: a poor man living a poor man’s life who plays a vital role in the nobles’ politicking. Richard’s role manifests again in his relationship with his lover Alec, a clearly high bred man playing pauper who roams around Riverside starting fights Richard must finish for him. Sexuality is dealt with in a simple and wonderfully frank way; it’s refreshing to read a book where non-hetero relationships are written about as easily and with as much normalcy as straight ones. Again, there’s a classed element to this: the sexual liaisons up on the Hill are just another form of secretive political alliance, whereas everyone in Riverside knows everyone else’s business and no one particularly cares much.

The writing itself flows like wine. Kushner has a smooth, rarefied voice. She is a master of imagery, knowing exactly which details to include to make a picture crystal clear. All of her writing is seamless, and it all works even when, by rights, it shouldn’t. A case in point is Kushner’s tendency to head-hop, jumping from one POV character to another with no warning within the same scene. Usually this irks the living shit out of me. Usually I find it jarring and it rips me out of the narrative. For some reason (and I don’t know why the particular alchemy of her writing makes this work) it was no problem at all for me in Swordspoint. There’s a kind of force to Kushner’s writing, and a kind of tricky truth, that keeps the book from being the overwritten confusing mess it could have been in another writer’s hands. My hands, for instance, could not have produced something in this style that was remotely coherent or pleasant to read.

Swordspoint is extremely good, but it’s not perfect. While the book passes the Bechdel test it’s still very much a masculine book. The honor at play is masculine honor—even when manipulated by the beautiful and calculating Duchess Tremontaine it’s masculine honor at stake. We see hints of feminine agency in Riverside, but the book doesn’t dwell on them. This is a masculine book, and the queer elements at play here are masculine queer experiences. We see many men pursuing and loving and getting rebuffed by other men, and presumably that sexual openness extends to lesbian relationships, too, but we see exactly none of that in this book. This may be a failing of the scope of the narrative more than anything else; in my own writing, Ariah has the same exact weak spots.

The prodigious plot of the book could have been tighter. Specifically, the thread of Michael Godwin feels very much unresolved by the end of the novel. His prominence in the story and the ambiguous place he is left when we last encounter him makes him feel like a more important character than he turns out to be. It feels, a bit, like Kushner loved the character and wanted him in the book, but really his story only crosses the main narrative arc in one or two places. He’s not actually vital to the narrative. It may be that he plays a bigger part in the subsequent books in the series, I don’t know, but in this book his subplot is strangely disconnected and unresolved.

All that said, I truly enjoyed Swordspoint. I struggled, actually, to find something to read after finishing The Ghost Map. I wanted to read a very good and immersive piece of fiction that I hadn’t read before. I tried a couple of things that didn’t click and put them down. I tried to rage-read Ender’s Game* but that fizzled out because I wanted to be entertained instead of angry. I was just coming off a trip that stirred up feelings and thoughts about my gender and sexuality, and it came to me that maybe something enthusiastically queer would do the trick. I’ve had Swordspoint in my reading queue for awhile, and it turned out to be exactly the right thing to read just now. I would suggest reading this in hardcopy, though—the kindle version I read was sorely lacking in decent ebook design. It was very much a slapdash conversion which did this fine book no justice.

*That is a whole post of it’s own that I’ve been drafting in my head for a while. Stay tuned.

November 8, 2013

Book Review: THE GHOST MAP

The Ghost Map, by Steven Johnson, is very close to a perfect book. The book describes the birth of modern epidemiology as it arose in response to a virulent outbreak of cholera in a particular 1854 London neighborhood. If you, unlike me, are not horribly enthralled by cholera or nerdily swoon at epidemiology, this has the potential to be a very dry read. And, in fact, going into this book I already knew the story of this particular outbreak of cholera because I’d read about it in much less gripping books about Victorian medicine*. What makes The Ghost Map different, and what makes it the kind of book that I now want to thrust into the unsuspecting hands of everyone I know, is that it does a remarkable job contextualizing the outbreak such that you, as a modern reader who likely has no direct experience of cholera, understands the absolute terror the Londoners felt in this outbreak. You feel the visceral urgency that comes with that terror, the awful need to unravel what the horrible riddle that was cholera.

Much of the book follows Dr. Jon Snow**, who is an interesting historical figure in his own right. A pioneer of anesthesiology, Jon Snow also had a fascination with cholera. It was he who, without the aid of developed germ theory, deduced that cholera must be waterborne and traced the outbreak back to a particular water pump on Broad Street. The Ghost Map has shades of narrative non-fiction, just enough to draw Jon Snow and the other players as real people, complete people with thoughts and tragic flaws and beating hearts. The book never tips fully over into narrative non-fiction, restraining itself enough that it does not speak for these historical figures, which I appreciated.

But to say that this is a book about Jon Snow’s prodigious scientific contributions is to give it short shrift. The real strength of the book is that it takes this single narrative thread—Jon Snow’s proto-epidemiological investigations into the 1854 cholera outbreak—and locates it in a myriad of nested lenses. This narrative thread is explored from the lens of the microbial cholera itself, describing cholera’s life cycle and the way cholera adapted to the new context of a dense and dirty human metropolis. This narrative thread is explored from the sociological lens of why Snow’s waterborne theory had to fight so hard to gain traction against the classist and Social Darwinist competing miasmatic theory of cholera transmission. Ultimately, the unifying element of the book is that Stevenson frames the 1854 cholera outbreak in terms of waste recycling—he starts the book with descriptions of the London underclasses who survived by compiling and moving and disposing of the mountains of human waste that Victorian London produced. He frames microbes as creatures whose waste products ultimately gave rise to multicellular creatures like ourselves. It is a fascinating, cyclical framing device that allows the reader to understand just how smoothly all the pieces fit together.

If you are interested in medicine, or the human body, or biological systems, or cityscapes, or Victorian England or just really good non-fiction I cannot recommend this book enough.

*I told you I was into this stuff. I will not apologize for who I am, reader.

**Full disclosure, I read A Song of Ice and Fire before my interest in Victorian cholera outbreaks asserted itself, so every time I read about the illustrious Dr. Jon Snow I have a hard time imagining him as the small, proper Englishman he was. Instead Jon Snow as portrayed by Kit Harrington from the Game of Thrones TV show pops into my head in improbable full costume stalking around Victorian London doing science. Here is an illustration so you, too, can experience this:

November 5, 2013

Beta Readers Needed: REAL MONSTERS

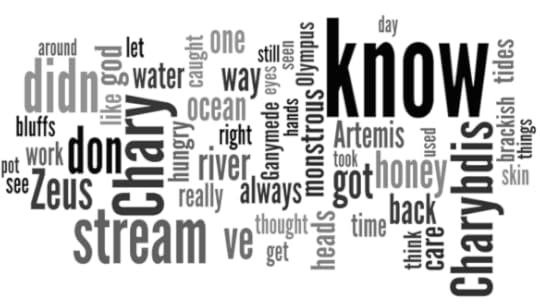

Scylla and Charybdis are sea monsters, but they didn’t start that way. In “Real Monsters,” Scylla tells her story. In Scylla’s version of events, what lies between Scylla and Charybdis is not death and destruction but a radical and vibrant love story. “Real Monsters” is a 3,600 word short story that uses Greek myth to interrogate what some conceive of as monstrous forms of love.

Interested? Let me know!

[contact-form]

October 29, 2013

Book Review: BORDERTOWN

Bordertown, an anthology of short stories edited by Terri Windling, has the distinction of being both a sparkling example of a shared-world concept and was a hugely influential excursion into the genre that would become urban fantasy. Written in the 1980s, this collection of short fiction marries high-fantasy constructs (elves, magic, etc) with punk rock sensibilities. The conceit is as follows: a long, long time ago magic was part of our world. For reasons no one now remembers, the Elflands departed and took magic with them. The two worlds existed in parallel until, with no explanation, the Elflands returned. A city—Bordertown—sits on the weird boundary between our world and the world of faery, existing in a liminal stretch where neither human technology or elvin magic works with anything like consistency. Bordertown, like all other fascinating cities before it, attracts runaways from both sides of the border. The collection includes four short stories, each set in a different part of Bordertown and each written by a different author.

I’ve read Bordertown and most of its companion collections several times each.* I read them a few times through as an adolescent who was distinctly an outsider in my home town (you can read a little bit about there here). I read them again in graduate school when I began to write my own fiction in earnest. I am one of the many genre-addicted misfit kids deeply influenced by this collection. Were I reviewing Bordertown on reach or downstream influence alone, five stars would not be adequate. I say all that by way of caveat, because I’m going to review the book, instead, on the text itself.

Bordertown is composed of four stories—“Danceland,” a murder mystery set in a punk night club; “Demon”, a story which explores the intersections of elvin and East Asian forms of magic; “Exile,” a quiet little thing about a very peculiar elvin girl; and “Mockery,” a love story set that reads like a La Boheme homage. Together, the four stories provide distinct snapshots into the lives of the youth of Bordertown. There’s no direct connection between the characters, no overarching plot. It’s a survey of what it’s like to live in Bordertown in a particular moment in time, a survey with a particular focus on the runaways and the kids just scraping by. But, as a glimpse into those people’s lives, it’s strangely romantic. I made a similar critique of Patti Smith’s autobiography, Just Kids; having known kids living these kinds of lives I can say with some certainty than not everyone makes it out in one piece. There are cursory nods to drugs and addiction, most explicitly in “Danceland”, but the most common and terrible outcomes of that kind of life, as well as the reasons substance abuse happens in those circumstances, are brushed neatly under the rug. Bordertown, for the people followed in these four stories, should be a much, much grittier place than it appears on the page. This is highlighted by the fact that a number of the protagonists we follow (with the notable exception of Michelle in “Demon” who inhabits a distinctly gritty and working class life) actually come from intact middle-class families either in the human suburbs on the edges of Bordertown or in the well-to-do elvin neighborhood uptown. These are kids, essentially, playing pauper. That’s a whole different ballgame than actually being a pauper. As such, the book dazzles us with its inherent coolness, a coolness I would like to point out still oozes from the pages, which is somehow not anachronistic in spite of how tied the book is to the decade which spawned it. Bordertown is escapist in nature. It’s exactly, precisely what I wanted to read when I was fifteen. Now I prefer a bit more nuance and realism in my fictional discussions of class in secondary universes, but this is pitch-perfect for the misfit teenager I used to be.

Taken separately, the stories are hit and miss. “Danceland” reads very much as the strong first chapter of a novel and less as a strong short story. And, indeed, the characters in “Danceland” appear down the road as protagonists in a couple of full-length Bordertown novels. “Demon” is an interesting conceit, but the writing left me flat—the author has a noticeable habit of head-hopping, or flitting between POV characters in a hard to follow and distracting way. “Exile”, I think, is the strongest of the bunch—it is the most grounded in simple emotional truths, it does a lot to explain and explore the foreignness of elvin culture through just a little insight into a elf girl cast out from her world, and it reads as a complete story populated by real people. “Mockery” I found overly long and overly romantic, but, my god, it influenced the hell out of me as a kid. Some years ago I wrote a novel which will never see the light of day, and that novel more or less completely ripped this particular story off wholesale. Yeah, my characters were musicians not painters (except one of them, extra oops) but the whole idea of very young and very talented and very wild kids living together and raising hell and changing things goddammit is stolen directly from this story. So, while I was less impressed by it this time around I will say that “Mockery” has a power to it.

Again, the influence of this collection can’t be overstated. Taken just on its own merits, though, I give Bordertown three stars out of five—it’s a book with a lot of heart, a lot of fearless gusto, but a book of short stories that could have used a couple more drafts.

*I own but have not yet read the most recent collection, Welcome to Bordertown. I felt like I should reread the past collections before diving into the new one, hence this reread.

October 28, 2013

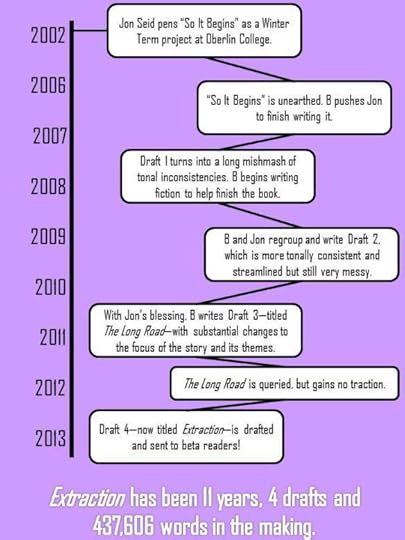

A Short History of EXTRACTION

Somewhat appropriately, this post marks the one year anniversary of this blog! Thanks to all my lovely readers!

Extraction is the latest iteration (hopefully the final iteration) of the very first piece of fiction to which I ever contributed or thought of as my own. As you can see in the infographic above, this current incarnation of the story now known to me as Extraction took 11 years to produce. It is the product of four separate drafts—and when I say separate drafts I mean four different raze-it-all-to-the-ground-and-start-from-scratch rewrites, each of which took several months to complete. A grand total of 437,606 word were written over the course of said 11 years*.

Now, there are many, many reasons to write your very first book and promptly abandon it. Most writers never publish their first completed novel; some sound advice is to treat your first novel essentially as practice. Let it languish in the desk drawer and use the experience to become a better writer next time around. And, if you read the infographic above, you can see that actually what became Extraction began as a short story penned by my partner, Jon. It wasn’t even my book to begin with. So why the commitment to this particular work of fiction? Why the dogged need to write and rewrite and rewrite and rewrite it again? Especially when the evolution of the story makes it so that the book is practically unrecognizable from one draft to another.

One reason I’ve kept plugging away at this book in particular is because the heart of the story—that individual choices in a war are almost always morally ambiguous—is worth exploring. The problem was that it took eleven years of writing practice (and of that only the last five or so have been years where I’ve been Seriously Writing For Realsies) to get to a point where I could get the story where I wanted it. I think most of us who write start first as readers. And not just any kind of reader, but highly attentive and engaged readers. It took until the last year or so where I would say I’m as good at writing a narrative as I am at reading it. So, I wanted to write this story, but it took a lot of patience to keep working at it until I got my chops where the story needed them.

Another reason is that I’m, perhaps, unduly attached to it. It would feel…perverse to publish a bunch of fiction over the years and for the spark that ignited the bonfire never to see the light of day. I think Extraction will see the light of day, and when it does, its debut will come with a great sense of resolution on my part.

In more practical terms, there are logistical reasons why it makes sense to polish this book up until it’s fit for public consumption. I write most of my books in the same secondary fantasy universe, and Extraction explores a set of pivotal events in that fantasy universe. The events outlined in the book’s narrative have direct links to things that happen in a bunch of my other books—notably, Resistance, The Prince of Norsa, Sound and Song and Ariah. The events here are essentially the pebble dropped in the narratological pond and the other books I’ve written are the ripples radiating outward. It would leave a weird, gaping hole in the Aerdh books taken as a whole not to get this one out.

I think it’s done. This draft needs polishing, it needs correcting, but I think this is the last wholesale re-draft. Extraction, it’s been a fun ride.

*This count is derived from the final word counts of each draft—it does not include the reams of text used for planning or excised texts and is such a frighteningly conservative figure.

October 20, 2013

Beta Readers Needed: EXTRACTION, A Tale of Rebellion Book 1

The rewrites for THE LONG ROAD are finally done! You can read about the rewrite process in this series of blog posts. The book has been rewritten more or less from scratch, and I’m very excited to share it with you all!

Times are desperate for the red elves: a generation of war has resulted in lost battles, a decimated population, and a handful of soldiers with low morale. When the humans develop vicious weaponry, the elvish captains retreat to devise a new strategy that will turn the war in their favor. But while the captains bicker they leave their soldiers behind on the front lines. EXTRACTION follows the last fighting band of soldiers left on the front when their captain, Li, returns with orders for a potentially suicidal mission to go into the heart of the war-torn country. As they travel, three of Li’s soldiers—the young and ruthless Rethnali, the bitter medic Sellior, and Li’s old friend and confidant Vathorem—begin to suspect this last mission is not what it seems.

Set in the unique and finely realized fantasy universe of Aerdh, EXTRACTION is a completed fantasy novel 83,000 words in length and the first of a series of books about the Lothic Elvish Rebellion. EXTRACTION is about the toll of war, the price of loyalty, and the cost of building a better future.

Interested? Let me know!

[contact-form]