B.R. Sanders's Blog, page 39

January 30, 2014

Epiphany Time: I’m Never Going to Leave My Day Job

my kiddo says you can pry my day job from my cold dead hands

I’m Officially Published now, not once but twice over. I now have Professional Fiction Writing Credits. That is amazing and wonderful and I am so proud of myself. It’s also set me thinking about what role writing plays in my life, both professionally and personally.

The ubiquitous dream of aspiring writers like myself is to make enough from your writing to live off of. A measure of whether or not a writer has “made it” is if they’ve been able to quit their day job. The thought of having all day to write at a leisurely pace, of taking an hour out of your day here and there to grant a fawning interview, yes that sounds divine. I think I just assumed that’s what I wanted, too. But I don’t really think it is.

To date I have made a sweet $23.00 off my writerly pursuits—shit, you guys, that’s a whole pizza! Obviously right now I have to keep my day job. I have spent more money on contest entries than I have earned back in sales. But here’s a thought experiment: let’s say one of my books really takes off. Like, it gets Harry Potter huge. What about then? It feels nigh-heretical to me, but I…think I want to keep my day job. I think I need to keep my day job for my own sanity.

Let me lay it out for you. I am the primary breadwinner of a family of four, and one of those four people is a toddler who depends on me for literally everything. I have two partners, both of whom do part-time or piecemeal work. Of the three of us, I am best positioned to get a solidly middle-class salaried position that can keep us afloat both by virtue of social/educational capital and by way of comfort working an office job. I am cool with it, and they are cool with it, too. If I were to tell my partners “hey, y’all, I think I want to give this writing-full-time thing a go, and I’m quitting my day job to do that” I have no doubt at all that they would support me. But life would be a scramble, and it would mean forcing one or both of them into positions where I get to pursue this at the expense of their quality of life. And most of all, it would be unstable.

I grew up in a financially unstable household. I grew up with bill collectors calling and the phone lines getting cut off; the whole nine yards. It is decidedly Not Fun. In my adult life, I have never paid my rent late, not one time, not ever. I am ridiculously conscientious with my family’s finances because I quite literally cannot go back to that kind of financial instability. I would lose my mind. These days, even the thought of not being the one in charge of paying the family bills and making the family budget lands me in a cold sweat. And if I wasn’t the breadwinner, would I have to give up that level of economic control within the family? I would think so. To manage the finances so closely otherwise would feel like overstepping a boundary.

I have an anxiety disorder, and it cozies up to the occasional major depressive episode. One thing that makes my anxiety flare up is financial instability. A couple of years ago, I finished my Ph.D. and went on the non-academic job market looking for a new gig. It was a nightmare. It was hellish. I could barely see straight I was so anxious. I was in danger of bursting into tears at any given moment. I couldn’t sleep. And I had a job while I was looking, which is the best case scenario since it meant I still had an income rolling in. But all those unknowns—what if I get fired if I go to this job interview? If I get that job, where will we live? Should we renew the lease? Should I be looking for jobs in a different area of the country?—those unknowns tore my brain to pieces. In many ways, the process of looking for a new job post-grad school was a time of pure psychological violence for me. Thanks capitalism.

With writing full time, there are no guarantees. There is no salary, no steady and reliable income. There are certainly no health care benefits (and as the only salaried full-time employee in the household, guess where the health care for my spouse and child comes from). Psychologically, I don’t have what it takes to be a starving artist. I crave the routine and stability of a day job. When I was on the job market? I hardly ever wrote fiction. Like most people, I can’t write for shit when I’m too anxious to handle making a sandwich. If I were to quit my job, I would be so obsessed with all the uncertainty of living off my writing that I ironically would probably not actually be able to write. Socially, it’s not really an option either. I have dependents. Starving artists just scraping by should not be doing so with children in tow. That’s selfish. It’s bad parenting.

I also need the balance of doing something other than writing. I need the contact with the outside world going to a job every day gives me. I get all weird when left alone too long. Weird and hermit-y and all Alan Moore-ish. Which, that’s fine for Alan Moore, but I do feel like there is value in being able to competently interface with society at large. I’d like to keep those skills sharpened, and introvert that I am, I am likely to let them go dull and unused without something to prod me to leave my house on the regular.

Besides that, I work in public education, which is something I am as passionate about as I am my writing. I really do need the balance; I love writing, and I fully believe that the act of writing can be radical and transformative and revolutionary. But it’s not the only way to effect change. I like to write my radical and revolutionary fictions and I like to push the education system hard from the inside. I want to have my cake and eat it, too.

My family makes ample space for me to write. I have a working routine, and I produce a lot of content while working full time. I would love to have a bestseller! Shit, it would be pretty sweet to scoop up the Nobel Prize for Literature. Or any prize for literature. But the mercurial and unpredictable life of a full-time writer is not something for which I am cut out. Which begs the question: if success for me is not financial, then what would success look like?

January 27, 2014

Book Review: FIERCE FAMILY

NOTE: This anthology includes a story penned by me, so there exists an obvious conflict of interest involved in me reviewing it and liking it and stuff. To that end, I’ve attempted to read it as if I didn’t contribute to it. Take that as you may.

Fierce Family is anthology compiled and published by Crossed Genres. The fifteen stories collected here are thematically joined by a focus on queer families as represented in speculative fiction. As someone living and growing a queer family who deeply loves speculative fiction, there was a good chance that I would like at least some of the stories here. That said, I’m also notoriously picky when it comes to short fiction anthologies, and especially multi-author short fiction anthologies. I am the type where one weak story can ruin the whole book for me.

This is a very well-executed anthology. The voices here are markedly different from story to story, but not jarringly so. The editor, Bart. R. Leib, seems to have paid close attention to the placement and order of the stories such that there are none of the disconcerting whiplash changes in tone or style you sometimes see in multi-author anthologies. I would have liked to see a closer hand at copyediting; there were a number of very minor grammatical or spelling mistakes that took me out of the stories from time to time.

I was pleasantly surprised by the depth and breadth of the stories themselves. The anthology contains a little of everything, and (so long as you’re not homophobic, obviously) there’s something in here for spec fic fans of every stripe: it’s got high fantasy, it’s got comic fantasy, it’s got space pirates and space warriors and contemporary sweet ghosts. There are stories here that are far-flung and far-future set in spaces our world does not resemble at all, and there are stories that could be happening to someone right now. Whatever floats your boat, this collection has something for it populated by a queer family.

I was also impressed by the diversity of the characters within the stories. It’s an wonderfully intersectional collection—most of the protagonists are people of color. The families range from single parent and child to wide open poly families with few biological ties. In some stories, the families are headed by queer parents; in some stories it’s the children who are queer. In some stories, it’s queertastically both.

For me, the standout stories were “Stormrider”, by Layla Lawlor, which features ice dragons. “Growth” by A. C. Buchanan hit me right in the heartstrings with a beautifully rendered bigender teen protagonist. “Form B: For Circumstances Not Covered In Previous Sections” by Stephanie Lai is perhaps the sweetest dystopian story I’ve ever read. “The Collared Signal” by J. L. Forrest has space pirates! And “Two Hearts” by Marissa James is a wonderful lesbian love story.

January 23, 2014

Book Review: DUST

Dust is the final installment in Hugh Howey’s Silo Saga. In Dust the plot threads introduced in the Wool books and the backstory exposited in the Shift books come to their inevitable head.

I enjoyed Dust—I enjoyed it more than the Shift books but not as much as the Wool books. But after Donald’s three shifts, I was ready to return to where Wool 5 left off: Juliette, the renegade cleaner, has returned to her silo determined to break the truth about her world to her friends and neighbors. Juliette, probably the most intricately drawn character in the the Silo Saga, stays true to form. As a reader, I trusted her to explore, to push boundaries, and to eventually lead her people out of her silo, and she fulfills that promise. Howey, characteristically, makes it a Pyrrhic victory once again.

Dust ties together Juliette’s plotline and Donald’s plotline, which was prefectly fine but not all that interesting to me. The banality of knowing where the silos come from has consistently failed to generate my interest when compared to the cloistered, claustrophobic lives of the other silos’ inhabitants. The books work best for me when we see the ways in which an entire life in a silo shapes people’s minds: the way the scope of the world narrows and how shocking and incomprehensible it is to Juliette and others when they realize there is so much more world than they ever thought possible. Donald and the others in Silo 1 feel patronizing and unnecessary. Donald’s storyline is there mostly to push exposition along and to ratchet up the stakes, but honestly I think that the stakes would have felt higher if he had stayed a disembodied voice on the illicit radio.

The exposition he delivers never quite pays off. Dust falls prey to the same thing that kills so many spec fic series: it’s got a myopia about the nuts and bolts that obscures the narrative. Ultimately, many of the revelations—what the argon in the airlocks really is, the state of the earth just beyond the hills, Thurman’s Pact—left me unsatisfied. Juliette’s struggles really sing, and her strengths and weaknesses as a leader drive the narrative beautifully, but Dust stumbles over its own clever trappings too often for it to fulfill the promise of the first five Wool books. Not every mystery needed to be explained, and Dust suffered in its insistence in spelling everything out for us instead of focusing on the heart of the narrative.

January 21, 2014

Book Review: SHIFT (Omnibus)

I was a couple years late to the Wool party, and the upside is that I didn’t have to wait to read the next installments in Hugh Howey’s Silo Saga. I finished the Wool books in bed and immediately bought the Shift omnibus on my kindle.

The Shift omnibus includes books 6, 7 and 8 of the Silo Saga: First Shift, Second Shift and Third Shift respectively. The Shift books functions as a series of nested prequels to the Wool books. Like the last three books in the Wool series, each of the Shift is structured around parallel or related narratives. Where the Wool books organized themselves according to location—Silo 17 or Silo 18—the narrative threads of the Shift books are separate by both time and space.

The titles of the books refer to the shifts of a man working in Silo 1, which controls and monitors the other forty nine silos. The people of Silo 1 were cryogenically frozen. Most are scheduled to be thawed back to life periodically for shifts six months long apiece. The Shift books track the histories of Silos 17 and 18 through the watchful eyes of one of Silo 1’s shift workers.

The Shift books have many of the strengths of the Wool—specifically the Howey’s sparse writing and knack for pacing. That said, without the dazzling newness of the worldbuilding Howey’s weak spots are weaker here than they were in Wool. The characterization tends to be thin throughout. The interpersonal complications outlined in Silo 1 have none of the heft or sharpness of life in the other silos, and the character whose shifts we follow is not fully realized enough to carry the books. The other figures in Silo 1 are sketched really just in relation to him, which leaves them one-note and flat. Given where Wool left us, Shift makes the mistake of squandering all that momentum instead of harnessing it.

January 17, 2014

New Pub: “Blue Flowers” in Anthology of QUILTBAG spec fic short stories!

Hi friends! I’m so proud to announce that one of my short stories, “Blue Flowers”, was chosen for inclusion in Crossed Genres’s Fierce Family anthology, which was released today! From the Crossed Genres page:

Strong, united families are rarely portrayed in speculative fiction. They’re often dysfunctional, combative, self-destructive, or miserable, when they’re portrayed at all. This is especially true for non-nuclear and adoptive families, single parent families and families with no children, which are easy targets for invalidation.

And QUILTBAG families are almost never portrayed in speculative fiction, regardless of whether their families are loving or falling apart.

15 exhilarating stories of QUILTBAG families experiencing adventure, disaster, and triumph make up Fierce Family. They are families of any constellation: all sizes and configurations, families of choice as well as families by birth. They are caring and connected – when outside conflict arises, they come together to defend and aid one another. Fiercely, and without hesitation.

Check out the anthology here!

January 4, 2014

Book Review: WOOL (Omnibus)

What I knew going into Hugh Howey’s Wool series was this: it was well-regarded science fiction, and it was hailed as one of the see-look-self-published-authors-can-totally-be-successful data points. Having read books 1 through 5 of Wool, which together comprise the first half of Howey’s Silo Saga, I can say the following: Wool is science fiction as its excellent atmospheric best and of-course-this-series-took-off-it’s-fucking-awesome.

Honestly, it’s hard to say more than that without spoiling some of the plot. The Wool series takes place in a post-apocalyptic world where the surface of the Earth is toxic; life can no longer survive above ground. We are introduced to a human population living in a vast, complicated silo. Life in the silo is regimented and tightly controlled—it has to be in order for the silo to function. Birth control and application procedures for both marriage and pregnancy prevent over population. The people we meet have been living in the claustrophobic confines of the silos for generations; they literally know nothing of the outside world except that it is deathly toxic. But why were the silos built? How did their first occupants get in their? These mysteries unravel over the course of the Wool series.

Wool deals with themes such as the collective value (or not) of honesty, of the way individual needs sometimes conflict with collective needs, and the mental toll of improbable survival. It’s set in a peculiar and minutely build future world, and Howey uses multiple viewpoint characters across the books to elaborate on different parts of the world through different lenses. His style, which is spare and precise and a little slow, fits the atmosphere of the book’s setting perfectly. The books, read together, follow a single narrative which gains speed and focus around book 3; the first two installments are related but stand alone well, but the subsequent three novellas are intricately tied together and really should be read as pieces of a whole. Again, the worldbuilding is fantastic, and the plot is riveting and dredges up a host of interesting philosophical questions. The only real complaints I have about the text are that the characters are somewhat flat throughout, existing mostly to push the plot forward instead of the other way around. If you’re not a slobbering fan of deep characterization like I am, though, this may not bother you at all.

December 31, 2013

2013 Retrospective

Here’s a quick look back at 2013 for me lit-wise! All in all, it’s been a great year: “The Other Side of Town” appeared in Redhead EZine; “Blue Flowers” and Resistance both are forthcoming next year. I consistently kept up with this blog! I’m looking forward to honing my skills and making more waves in 2014! Happy New Year, folks!

December 26, 2013

Why A Woman Writing As a Man is Different Than A Man Writing As A Woman

A few weeks ago, Writer’s Digest published an article by James Ziskin titled “Writing Across Gender: How I Learned to Write From a Female POV”. I let this article simmer in my saved folder in Feedly for awhile. I knew I wanted to read it, but I also knew I would Have Words To Say after I’d read it, and I wanted to be in the right headspace to clearly articulate said Words.

James Ziskin has written a novel which features a young woman as its protagonist. “I write like a girl,” he says. “More precisely, I write as a girl.” I have not read Styx and Stone, so I can’t say one way or another if he succeeded in my eyes.

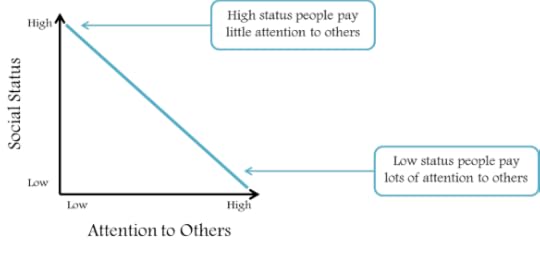

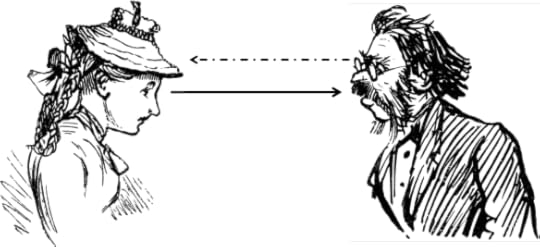

What I can say pretty definitively is that I have a huge amount of skepticism that he truly succeeded. The thing is that it is inherently harder for a man to successfully and authentically write a woman character than for a woman to write a man. This is a product of living in a socially stratified and hierarchical society. My background and training is as a psychological researcher, and much of my research focus on the exploration of power dynamics. There’s a robust finding in social psychology that social status and interpersonal attention are inversely related; that is, the higher up you are on the totem pole, the less you pay attention to other people. Especially those people lower than you on the totem pole.

Susan Fiske (1993) looked at this specifically in work contexts: an employee pays a whole lot of attention to their manager, but their manager typically pays little attention to them. We’ve all been there, right? You know how your boss takes their coffee, what it means when they get fidgety. You can predict how that meeting will go simply by the way they walk over to your cubicle. But your manager probably knows little about you—they don’t even know if you drink coffee, period, much less how you take it.

This finding has been extended to look at how the use of social power changes the way people attend to others and whether those using power can take people’s perspective. Guess what? The use of power tends to turn people away from thinking about how those around them feel, or how their actions might affect others (Galinsky et al., 2006).

What does all this have to do with Ziskin’s article? Well, the thing is that power is not only used in the workplace. Power is ubiquitous and nebulous. It’s a chameleon that manifests differently in the various domains in which we live—we experience, submit to and use power in our personal lives, with strangers, in schools, etc. It’s no stretch to map these findings onto society writ large; if we think of social status as markers of privileged identities, then the reasons why I am so skeptical of Ziskin start to get clearer.

I am a Female Assigned At Birth genderqueer person, which means that I was born what the medical establishment considered female and was raised as a girl. I am read by virtually everyone I meet as a woman; I am not physically androgynous though my gender presentation is all over the map. I have an authentic, if atypical, insight into what it is to be a woman in modern American society. I will posit that Ziskin does not.

A really big part of being a woman is learning to pay lots and lots of attention to the men around you. You learn that very early on—men are more likely than you to have wealth and opportunities and as such are usually the gatekeepers to you yourself getting access to those opportunities. Men are potentially dangerous (if you have not already, please read Schrodinger’s Rapist ). As a woman you have to learn to read men’s moods and be able to predict their actions with a fairly high level of accuracy. It’s not all that different than an underling knowing what kind of coffee their boss likes—in each case, noticing all the little things that can predict the bigger actions is important. Knowing how someone who has power over you is going to use that power is a necessary skill. It can, quite literally, be a matter of survival.

I should say here that I think this framing of social dynamics is an inherent part of the tension between marginalization and privilege. It is, in fact, a mechanism that helps to create and reproduce marginalization and privilege. What I mean to say that I think this dynamic where the marginalized has to know and understand the privileged better than the privileged ever know the marginalized is a common element of oppression. We have a lot of different ways of coding this: code-switching, being stealth, staying in the closet are all examples of marginalized people learning the way the privileged act and mimicking that in order to stay afloat.

But what does this mean for writers? It means that no one writes in a vacuum. It means that all of this happens through socialization and internalization of norms and perceptions that don’t disappear just because you’ve decided to tell a story. It means that no one writes from a place of objectivity; nor should they. It means when Ziskin sits down to write as Ellie Stone he does so having lived as a man in a society that privileges men over women. In essence, he is writing right into his own blind spots. Now, again, I haven’t read his book. But in the article he’s penned, he describes his heroine this way:

Ellie Stone is a self-described “modern girl” in 1960′s New York. In the days before feminism, she plays like a man, but make no mistake: she’s all woman. A Barnard graduate from a cultured family, she’s determined to have a career that doesn’t involve fetching coffee for a boss who pats her rear end when she’s done a good job. Or even when she hasn’t. She’s a realist, though, aware that a woman can go only so far in a man’s world, so she accepts a lowly position as a fledgling reporter for a small upstate daily. Her beat includes Knights of Columbus Ladies’ Auxiliary meetings and high school basketball games. But Ellie’s the smartest person in the room, a quick wit, and one of the fellas when it comes to holding her drink. She’d better be able to hold her drink, or be prepared to defend her honor.

If this is at all indicative of how Ziskin writes Ellie Stone in his novel than I would wager that he is not successful in his endeavor to “write as a girl.” This reads as a what a man thinks a woman thinks like. Over and over in this short block of text he asserts patriarchal dominance. He falls into the trap of going out of his way to assert her as beautiful. He mentions in an off-handed way that she deals with sexual harassment and possible sexual assault but the deep-bred visceral fear these interactions bring up in most of us who live as or are read as women is missing. I am also curious as to what he means by “she plays like a man…[but] she’s all woman.” The only way I can understand this is through gendered binaries of what women do and what women are like imposed by men—which are sometimes accurate due to patriarchal restrictions but often are just plain wrong. In short, Ellie Stone may very well end up a cipher; a set-back-then-when-men-were-men-and-women-were-women version of a Manic Pixie Dream Girl .

This isn’t entirely Ziskin’s fault, though I do think it’s an act of eyebrow-raising hubris that he feels so very comfortable writing women that he has proclaimed himself a master at it in a widely-read high-profile blog. The thing is that Ziskin can’t write Ellie Stone authentically because he literally does not know what would make her authentic. He hasn’t lived it. He doesn’t understand male privilege enough to know when to check himself in the writing and when to reassess his own writerly instincts.

I did some thinking after reading Ziskin’s article. I can name, easily, a number of women writers who I think have successfully captured a male voice—Ursula K. Le Guin comes immediately to mind, as does Susannah Clarke. Agatha Christie. J.K. Rowling. Margaret Atwood. Virginia Woolf. Flannery O’Connor. It is much harder for me to think of the reverse. Phillip Pullman does, for the most part, an excellent job with Sally Lockhart. I recently reread Mieville’s Embassytown, and I’m again impressed by his female lead. And that’s all I could think of on my own. I fielded the question to some of my women friends who are voracious readers, and I got Sally Lockhart again and Lyra from His Dark Materials. So, well done, Philip Pullman! Another suggested the lead in John C. Wright’s Orphans of Chaos, which I have not read, but which she says can still be read as problematic. A friend also cited Hopeful Monsters which I have not read and she says is pretty obscure. And that’s all we got. Five of us wracking our brains—brains that hold massive libraries—and that’s all we got. My point is not that it can’t be done, but that for a person with privilege to write a person marginalized along that same axis is extremely difficult. Mr. Pullman might as well be a unicorn.

And I don’t mean to vilify Ziskin. I am, I will admit, irked at the arrogance it takes to declare yourself successful at this, but, again, this isn’t really about him. It’s about how we don’t write anything in a vacuum and how every single word we write and choice we make as writers is informed by the lives we have led. A couple of months ago I had this wonderful idea for a book—the kind of idea that makes you feel high when it comes to you, truly inspired. The kind of idea that comes to you so perfectly and fully formed that it feels like you could write the whole damn novel in one go and you search desperately for the closest keyboard. I was about to launch in on it…

…and I stopped. Because the lead character was a black woman living in Baltimore just after the Civil War. And I just…I had to take a deep breath and put the idea on hold because I cannot speak to that character’s experience authentically. I can’t. I have some understanding of some of the issues facing the Black community in an intellectualized and abstracted academic way but I am in no way a part of that world. I am a well-meaning White person, and I had to check myself because the world does not need another well-meaning White person writing about the Black experience like they know anything about it. If I ever do write that book, it will be after a dissertation’s worth of research and even then it might never see the light of day. I have written about racial oppression before, but only in secondary fantasy contexts where the oppression doesn’t reflect the real histories of people whose voices are already silenced. And even then I get pangs of worry that I’ve overstepped my bounds, that I’ve been disrespectful and appropriative in presuming to know how that might feel to live through.

I guess to wrap up I would say this: not only is it inherently difficult to write about a person who is marginalized by privileges you hold, but I don’t think it’s appropriate, either. We have plenty of male writers writing women’s stories; we could use more women writing women’s stories. We have plenty of White people (like me) writing Black people’s stories; we would do better to shut up and hand the mic over to Black people, to step aside and let them tell their stories instead.

I don’t believe Ziskin can write as a girl. I don’t believe he should.

Cited:

Fiske, S. (1993). Controlling other people: The impact of power on stereotyping, American Psychologist, 48, 621-628.

Galinsky, A., Magee, J., Insei, M., & Gruenfeld, D. (2006). Power and perspectives not taken. Psychological Science, 17, 1068-1074.

December 21, 2013

Book Review: HOW CHILDREN SUCCEED

Hint: try being white and wealthy, kids!

Paul Tough’s How Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity and the Hidden Power of Character is another in a long line of books which tries to determine how we can better serve “underperforming” children—specifically children in poverty and children of color. Tough posits a fairly new approach to this social problem: character. He draws a distinction between cognitive skills, which are most often expressed through academic ability, and noncognitive skills like perseverance, conscientiousness, and eagerness to learn. Over the course of some 200 pages, Tough explores how and why these noncognitive skills develop from a variety of approaches—interviews with students and educators, positive psychological research, studies of rats’ mothering habits and biological stress responses.

The context of the book, though, is as important to my reading of How Children Succeed as its actual content. This is a book I see around my workplace often. It was, in fact, loaned to me by a coworker. And last year, while I was on fellowship as an Education Pioneers Analyst Fellow, some of my cohort read it in a book study. I work in the ed reform movement (something I have deeply ambivalent feelings about), and this book is fast becoming part of the ed reform lingo. It’s a natural fit. This book (and by extension its writer) comes from the same place as my TFA alum and Broad resident coworkers: this is a book written by a deeply privileged person who wants to fix education. That’s a noble goal. But the problem I see over and over in the ed reform movement is that these privileged people cannot see past their privilege, and so the ways they want to fix education continually read to me as shallow and ineffective.

Tough’s book is a great example of this tension. Tough grew up middle class, white, cisgender and male. At several points in the book, he discusses his decision to drop out of Columbia University as a tortured eighteen year old. The fateful dropout decision is not predicated on some external forces (a financial crisis or having to return home to take care of a relative in a tight spot) but on a vague notion that he wants to “try something that’s new”. Tough ends up bicycling halfway across the country, then returns to college only to drop out a second time. So, this is the author’s background. His research and reporting for the book takes him to the South Side of Chicago where he tries to understand the lives of struggling high schoolers. He seems to see these kids’ struggles mostly as a result of two things: the high levels of stress they’ve encountered in their short, violent, impoverished lives and the apparent absence of secure attachments to caregivers. Tough uses research on the HPA axis and biological effects of stress and research on attachment theory to largely explain why and how these kids haven’t yet developed the cognitive skills needed to get them to and through college. And while both of those things may play some small part in their current trajectory I believe he severely overstates the effects of both.

Let me tell you where I’m coming from. I am white, but I grew up poor and queer and struggling with my gender in a small, conservative town in Texas. My parents were both trapped in substance abuse. I was alternately neglected and abused by them, and as such, never developed a secure attachment to either. I also excelled in school (though I was a troublemaker). I got out—got into college, graduated, and then got a doctorate. I am what educational psychologists call “resilient”. I have what Tough calls character in spades. My sister is less resilient. The major difference between my sister and I? She is dealing with a different level of mental health issues than I am. She has a learning disability that was never diagnosed. She didn’t excel in school. In a word, she didn’t look like she could pass as middle class.

Tough makes the case that if poor kids have a positive adult role model to help them develop ‘character’ that they can ‘succeed’. He never stops to consider that what he has deemed ‘character’ is a very white middle-class idea of character. It is deeply steeped in the Protestant Work Ethic, for instance, and it may be that poor kids of color are developing a different kind of character, a set of noncognitive skills acutely attuned to the context in which they live. My avoidant attachment to my parents growing up, for instance, was a totally appropriate way of managing my relationship to unstable and unreliable caregivers. The same with his unspoken assumptions about what success looks like—this is a white, middle class idea of success. When Tough abstracts character and success from the context these people live in, divorcing it so neatly from the structural and institutional oppression caused by racism and classism, he presents the answer to our ‘education system’s failures’ as very simple. While reading the book, the message I got was that all we have to do is train poor black kids to act like well-off white kids and they’ll do just fine. The fact that this strips them of their culture, that it separates them from their families, that faking-it-til-you-make-it is another kind of colorblindness is not addressed. And I can say from my personal experience that I faked-it-til-I-made-it. That’s exactly how I got to and through both college and graduate school. And now I’m upwardly mobile but I’m still a kid who grew up poor. Navigating social class has only gotten harder as I’ve moved up the social ladder. I can’t imagine what it would be to be black or Latino on top of it and to have my marginalization so clearly written on my skin.

The heart of my issue with the ed reform movement, and this is something that Tough’s book falls prey to, is that it doesn’t see the American education system for what it really is. Today, the American Dream is synonymous with educational attainment. The problem is that the American Dream was never meant to apply to most of America. We’ve constructed our education system to explicitly create class divisions along racial lines. Our education system is not failing—it’s achieving exactly what it’s built to do. There’s no reforming it. No amount of character classes in charter schools attracting smart but impoverished kids of color is going to change that. The ed reform movement is a predominantly white, middle class movement and as such it is a movement that makes certain assumptions about the fairness and good faith of the institution of education as it currently exists that are false.

I succeeded in life because I am privileged enough to blend in with the privileged ruling class. I’m white. I’m academically gifted. I was an avoidantly attached enough kid that I was fully comfortable leaving behind my broken family. I worked very hard to lose my scraggly Texan accent when I arrived at college. The noncognitive skills that got me where I am today are largely those that let me forcibly blend into an unfamiliar environment ripe with opportunity. I am a fluke. I am the exception. And it’s not my kid sister’s fault or the poor black kid on the South Side’s fault that they didn’t make it. For other people it’s not so simple as just developing a better character, and on every page I felt insulted at the implication that Tough felt he’d found the silver bullet in this. There are no silver bullets. There’s no reform. The only thing that will work is rebuilding the system from the ground up. There’s no improving an inherently racist and classist institution—there’s only replacing it.

December 20, 2013

Book Review: EMBASSYTOWN

Embassytown, by China Mieville, is one of my all-time favorite books. I’ll give you a sense of the plot, but it won’t do the book justice. Avice Benner Cho hails from a tiny outpost on a far-flung planet. Arieka is a backwater notable only for the oddness of its sentient indigenous life-forms, the Ariekei. Mieville does a wonderful job creating aliens who are truly alien—this is my second time reading the book and I still can’t quite picture the Ariekei. They have wings and hooves and chitinous shells and eye stalks. They have two mouths, and use their double-layered voices to speak pure truth. Everything they say is literal. As contact with the humans increases and the Ariekei need more and more foreign things to say, they turn to the creation of similes. Avice Benner Cho is tapped in her childhood to become one such simile—the scene is minutely prepared, and so must have been envisioned somehow by the Ariekei, but cannot be spoken until it’s happened. This tension between wanting to break free of literalness and their inability to do so pops up again in the Festival of Lies—this amounts to an Ariekei extreme sport as one after another tries and fails to lie.

The story revolves around a crisis moment on Arieka where Language is put into dire jeopardy due to the political machinations of humans far removed from the day-to-day life of Embassytowners. The purity of language becomes first a philosophical and then a physically violent war. Avice, in part due to her status as a particularly flexible simile, leads the charge to break the Ariekei free of the literal bounds of Language; in essence, she sees their survival and her own as dependent on teaching them how to lie. Her estranged husband, Scile, is willing to see everyone on Arieka (human or otherwise) die to protect the purity of Ariekene Language.

Embassytown tells a story about epic, revolutionary change. It does so with an unflinching gaze and an outright refusal to sugarcoat just how horrifying and how brutal such a change, by necessity, is. Paradoxically (though I believe intentionally), for a book about the importance of lies and near-lies, it’s an extraordinarily honest book. The fact that the book itself is a work of fiction striving to uncover and articulate a truth about our modern world is not lost on me. Mieville is a Marxist, and in rereading the book it seems that the entire novel is a comment on false consciousness. Lies are a form of truth, he argues, if they can be used to break you from the way you’ve been forced to see the world. When we envision a better future, a different future, a future with no precedent, that is a kind of willful lying. When we attempt to reconfigure our place in society and the way in which we interface with the world around us, that is a kind of lie and a kind of truth at once. Near the end of the book an Ariekei character gives a beautiful, tender speech about this tension—before the ability to lie, it claims, it did not truly speak. All it did was describe the confines, the parameters, of its existence. It couldn’t create; it could only describe. And that is at the heart of the idea of hegemony and false consciousness—under the yoke of capitalism we can only describe what exists now, how we are now. It takes a fundamental, painful break from life as we’ve lived it to construct an alternative. I don’t want to spoil it, but I will say Mieville’s understanding of revolution and dialectics extends past this. The Ariekei, like Marx’s working class, have to literally break themselves down to rebuild themselves and their society. It is a violent, desperate, brutal process.

The other themes present in the book—the nature of addiction, the nature of the individual self vs the collective self, the parasitic element of bureaucracy—all tie back into these Marxism-tinged ideas about language. It is a book full to the brim with ideas, with careful and attentive thought. That Mieville manages to imbue all these thoughts into a book that is also packed with plot and characterization is amazing. Avice Benner Cho, who serves as our viewpoint into this world, is a wonderfully rich and fully realized character. Her voice is clear and never once does it ring false. There is a real economy of language here, but we feel it when her marriage falls apart even as she herself can’t quite articulate why it’s happening. And given the plot of the book, Avice is precisely the right character to tell the story: just insider enough to carry it, but outsider enough to allow for questions and inference. Just similar enough to the reader to feel familiar in this strange, unfamiliar setting.

Truly, I cannot recommend this book highly enough. Embassytown is a brilliant, moving novel. It’s a book that sticks with you long after you finish it. As much as Railsea meant to me personally, Embassytown is my favorite of Mieville’s works.