Andrea M. Jones's Blog, page 7

July 3, 2019

Groundsels

I’d need to dig deeper to narrow down the name, since we have a couple of variations in leaf shape/wooliness and some differences in the ray shape and arrangement. Based on the habitat here, chances are pretty good that these are Rocky Mountain groundsel, S. streptanthifolius.

In any event, these flowers have quite happily re-colonized the ground on the south side of the house, which I rather loosely call our “yard.” They bloom at the same time as, and are a very fetching combination with, blue-flowered veronica groundcovers.

This plant also shared time with the sticky geranium in yesterday’s photo.

This plant also shared time with the sticky geranium in yesterday’s photo.

July 2, 2019

Sticky Geranium

July 1, 2019

July Vacation

This morning began with work on a blog post I’ve had in mind since sometime in May. I took a batch of pictures for it on the first of June, and finally started writing this morning, running late but determined and optimistic. By mid-morning, I had a rough draft and broke off for a quick walk to take a few additional photos.

About twenty minutes into what turned into a meander of almost two hours, I decided to shelve the post until next year.

It was the flowers, you see.

They’re blooming. All of them. Everywhere.

Okay, maybe that’s an exaggeration, but there really are wildflowers blooming all over the place right now.

Our precipitation over the winter and through the spring was decent, and whether it’s simply water or pent-up desire after a run of several dry springs in a row, this booming bloom is something to see.

So I’ve created an excuse to go see it, as frequently as possible: I’m going to blog the bloom, in pictures.

Rather than hitting you with all this color all at once, I’ve decided to post a flowering plant each day for the month of July.

Here are the rules I made up as I was wandering, taking pictures, feeling tipsy on floral perfume, listening to the bees, and generally being dazzled.

Native plants only.

Photos don’t have to be taken the day they’re posted, but they all will be taken this July, 2019.

All plants will be observed from home on foot and thereby located in my local neighborhood.

Now, anybody who’s followed this blog for any length of time is likely thinking this all sounds farfetched in the extreme. Although I aspire to post fortnightly, I rarely sustain that pace for any span of time, and I’m particularly notorious for vanishing from the blogosphere for extended periods during the summer months (as rationalized here).

I decided back when I started this blog nearly six years ago that I’d prioritize writerly whim over punctuality and consistency. I thought then, and I’m even more certain now, that I’d feel boxed in by a strict schedule. I’ve pursued blogging as a reflective exercise, and have tried to find my discipline elsewhere. I’m still looking for the discipline, but the relaxed approach to blogging has kept it fun and interesting.

Given all this, a thirty-one day commitment feels risky. This project is based on a cheat, though, so I’m plunging forward. I’m aiming to post a daily photo, but I’m on vacation when it comes to writing: I might make a few comments here and there, but I’m not holding myself to an obligation to compose anything more substantial than plant names.

On which note, I’ll do my best to be specific and will try to supply the formal Latin at least occasionally, but I’m embracing this whole “vacation” concept and am not making any promises.

I’m also copping out a little, though, because I’m stymied by this first plant. It’s blooming in drifts right now, so enthusiastically it deserves to be up first, but I’d only be guessing if I offered a name. I call it “the little purple penstemon that blooms earlier than most of the penstemons.”

In my defense, here’s what my copy of Plants of the Rocky Mountains (Lone Pine Publishing) has to say about penstemons: “The genus Penstemon is a large and complex group of plants. There are dozens of species in the Rocky Mountains, and many of these species hybridize freely, producing populations of plants with characteristics that are intermediate between the 2 parents. This can make identification difficult.” (p.196).

We’re going to pretend that identification is too difficult in this case, but I can tell you this plant prefers east and south-facing slopes with plenty of rocks and not a lot of competition from grasses. The flower stalks are only about six inches tall, but the plants are so numerous that entire hillsides look as if a cloud shadow is passing over; but no, it’s just penstemons, in their thousands, bluing the hills.

May 31, 2019

One Last Fire

May 30, 7 a.m.

Spring, as I’ve said before, is a slow unfolding up here in the mountains of central Colorado: the season isn’t to be rushed. But eventually the days lengthen and long-dormant plants emerge. Among the first of these are rough cinquefoil, dark clustered leaves scattered like green pawprints through the dead grass, the silver-brown thatch of which will only later be later pierced by fine needles of new growth. The bluebirds show up and leave, show up and leave, and finally show up to stay, along with the wrens and the spotted towhees and Say’s phoebes. Sooner or later, I’ll be startled by what appears to be a cocktail garnish whisking between pine trees, but it’s a Western tanager, his head maraschino red atop his lemon-yellow body.

I start reaching for a brimmed hat rather than the wooly knit cap. More days than not, I put on barn shoes instead of snowboots, and contemplate throwing the latter into the back of the closet for the season. Some days, I’ll step outside before deciding: lightweight jacket or winter barn coat? After a long season of daily wear, said coat needs washing; it’s grungy with mud and horse slobber, fuzzed with shed horsehair, each pocket loaded with a few ounces of hay dust.

Snow collecting on the windows last winter: a pretty lace while it lasts, but it leaves muck on the glass.

I need to wash the grime of blizzard schmutz off the windows, too, and clean the fireplace. We’re ready to take a break from hauling firewood and splitting kindling. For a few months, we can leave off the afternoon ritual of lighting a fire against the early dark and settling cold….

Can’t we?

For a month now, whenever I think I’ve lit the last fire, the little raindrop icons on the extended weather forecast morph into snowflakes as the projected temperatures drop. The National Weather Service keeps authorizing my procrastination, justifying my avoidance of cleaning out ashes and scrubbing at sooty fireplace doors.

I wasn’t surprised when we woke up on the last day of April with a half-foot of snow on the ground. Our April showers usually fall as the white stuff. There’s always a chance of a late-season blizzard, but the ground has warmed up enough that such snow starts melting as soon as it falls, and the April close-out snow vanished into the ground within a day.

Ice on the pine boughs.

The weather warmed back up to rain-worthy temperatures for a week, but then dropped again on May 8th. The next day’s high was 31 degrees, with snow falling gently all day. I personally thought the winter reprise was a bit over the top, but at least I hadn’t already cleaned the fireplace. We were out of firewood at the house, but I scrounged the last split logs from down at the cabin, and built a fire.

A few days later, it was 70 degrees and the glories of spring had settled in (again). I thought about getting to work in the garden—and washing coats and cleaning the fireplace. Another weather system had appeared in the forecast, though, and I held off.

That storm materialized with slightly milder temperatures but it was still plenty cold enough to warrant a fire. I drove down to the neighbors’ house and filled the log bag from their well-stocked woodshed.* That storm dropped eight inches of snow, and when the sun came out the next day it was hard to tell which was happening faster: the snow melting or the grass growing.

Iced bunchgrass.

The day after that, however, I woke to the gloom of a house engulfed by heavy fog. I kept expecting it to burn off, but when I went for a walk after lunch I encountered a bitter wind blowing up from the south. The fine mist in the air froze onto everything it hit, glazing fence wire and gates and powerlines and individual blades of grass in clear ice. Pine boughs that might have waved in the stiff breeze merely rocked up and down, the trees creaking under the weight with a crinkly sound like cellophane being crumpled. I cut my walk short and hustled back to the house, where there was just enough wood left for the evening’s fire.

Another week of spring followed. Out walking, I found blooming cacti and sweet starbursts of mat daisies instead of icy sculpture. Then, on the 29th, the forecast again switched from rain to snow. As I headed down the driveway to feed the horses late that afternoon, a brusque wind smacked me in the face with fat heavy snowflakes. I had put on my coat but not the snowboots; my shoes and socks were quickly soaked. The horses, even wetter and colder than me, were outraged and belligerent. When I got back to the house, blobs of slush splatted onto the floor from my hat and stinking, sodden barn coat.

I disassembled to the shelf of scrap lumber we’d laid across the rails of the wood rack in the garage to catch flakes of pine bark, and built a fire with the planks. When we went to bed, there were a few boards left; just enough, perhaps, for one last fire.

*This lifting of the neighbors’ wood is authorized: we help with the splitting, and since they don’t overwinter, their stock runs down slower than ours.

May 9, 2019

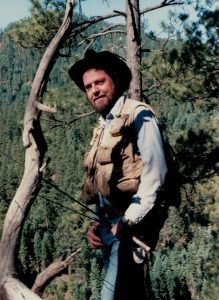

My Father at Eighty

My Dad as an old man is a mystery.

My Dad as an old man is a mystery.

Actually, I’m not sure that’s right—or if it is, I must qualify. My father, who would have been eighty years old on May 8, is the sort of mystery that is blankness, unanswerable, beyond the reach of workaday comprehension. This isn’t the mystery of suspense, not a whodunnit enticing you forward with tantalizing clues. Dad’s story is over. We know how it ends, and when: dead of brain cancer, aged 58, in December 1997.

His life ended, but my Dad still exists, which is the enigma. I’m grateful for the half-life a person lives in thought and memory, but I didn’t ask to be a keeper of his legacy. I’d rather he were still here, in charge of his own representation.

More than twenty years after he died, I still get lost in the hollows of “What would…?” Those hard questions settle like cobbles in the unfirm watercourse of memory, too heavy to be thrown out by the current of passing time. Such queries swirl and spin in hopeless entrapment, carving depressions, bowls, chambers. What would he be like now? What would he look like as an old man? What would he think of these times, our issues of the day? What would we talk about? What would our love look like?

When I’m with my family, we acknowledge such questions even as we sidestep the blankness they imply. My personal favorite is to ask “Can you imagine him with a cell phone?” deftly steering the conversation clear of confrontation with loss, diverting us into hyperbolic speculation and laughter about the many ways he’d never be away from the infernal thing. As it was, back before wireless technology, he always managed to be on the phone, tied to his desk by its springy cord, vanished from the bar or the restaurant table to a payphone in the hall by the bathrooms. Even while driving, he’d chat on the CB radio or raise the operator on the mobile telephone service: “Edith? It’s Jones. Can you dial….” To be in public with him meant making do with his divided attention.

As one of the curators of his memory, I want to be a good proprietor, but certain dishonesties are inevitable. I cannot see the world the way he did, and my perspective on even our shared history veers wide of his. When I was young, I knew plenty about his infidelities and indiscretions—more than a daughter probably should—but there’s lots more I don’t know, and don’t care to. During my college years, I often got dirty glares from cute female bartenders, women who bristled when I walked in to be greeted with a grin and a hug and a kiss, women who visibly relaxed when I was introduced as the daughter. He wasn’t cynical, and whether he rationalized away the cruelties of his relationships or simply found a way to ignore what was, to him, collateral damage, I don’t know. I do think he was sincere in his affections and honest in the intensity of his passions. He loved people, loved drinking and gambling, loved the mountains and fishing and hunting. He’d claim he had no regrets, but I was with him enough in his final months to believe that he was haunted by at least a few. This belief is just my opinion, of course, or it could just be whitewashing; either way, it’s another part of the mystery.

Gregarious and entrepreneurial, my father was compelled to be in company with people. He was constantly working deals, ever-ready to propose a get-together, spontaneous to the core. Meet me a the Elks in 30 minutes for a beer (although he would most likely be late); Let’s stop in to see __ on the way through town. We’re going camping on the Piedra this weekend, want to come?

What he wasn’t, and never will be, was old, and there are layers to this fact that trouble me more the older I myself become. It bothers me that picturing my father at eighty takes imagination, that he is, at that age, a fictional characterization.

He’s locked in memory as that familiar fifty-something guy, bearded, blue eyes bracketed with creases carved by an easy smile and a too-short lifetime of squinting in the Colorado sun. My mind’s eye involuntarily puts him outside, a bandana scarf around his neck and a sweat-stained cowboy hat on his head.

If the vocabulary file in my mind offers the word “ageless” in response to this image, the rest of my brain pounces, snarling. Anything but ageless. Gone way too fucking young.

April 26, 2019

Lifting the Moon

Not this full moon, and not moonrise the day after full, when it’s already dark when the moon is coming up. But one of my favorite moon photos.

On the evening after the full moon, as dark settles fully in, I’m settled in, too: sunk deep in the cushions of the reading chair, reading, with feet under a throw and a glass of wine at my elbow.

Doug, on the couch, stirs, gets up, announces he’s going into the hot tub. I nod but don’t move; I’ve reached a stage of life in which a hot soak before bed leads to an uncomfortable night. Besides, I’m feeling lazy.

Looking at the tops of the ponderosa pines beyond the deck to gauge wind speed, Doug adds, “Ooh. Nice moon.”

That’s enough to get me up, to at least admire the moonrise through the window. And it is nice—gorgeous in fact. Turning my back on it to return to the chair seems ungracious.

So, while Doug strips, I put on coat, hat, and gloves. It’s a pleasant night but “pleasant” when you’re 8900 feet up in the Colorado Rockies in April is a relative term.

Outside, a higher-than-usual hint of humidity chills the air and gives the moon’s glow a faint sepia tint. The light is warmer and more golden than the platinum glitter of a dry mid-winter’s night. There’s plenty of light for walking—enough, in fact, that my shadow leans in front of me like a dog straining at the leash.

Just over the crest of the hill leading down to the barn, there’s a line of shadow thrown by the ridge. I step out of the moonlight, but the sheen across the sky’s dome offers ample illumination, and I keep up my full-paced walk.

I don’t emerge out of the shadow until I’m out on the straightaway beyond the pasture gates. Turning to walk backward for a few steps, I admire the moon’s ambered disk shining through the black silhouettes of the pines along the top of the ridge. I stop, move forward a few steps to re-enter the shadow zone, and walk backward again, watching the moon rise out of the trees.

I turn and rejoin my shadow on our walk. The familiar landscape is filtered by dark, with each rank of hills progressively dimmed by distance. My feet are confident on the familiar road, but my eyes are looking across the frontier of their limits. I sense colors but cannot detect them. The details my mind provides are, I suspect, filled in by day-lighted memories.

Following the road downhill on my usual walking route, I reach the tree where Doug and I traditionally turn around when we’re out for a stroll, but I keep walking; the night is fine, and I have my eye on another line where the polish of moonlight on the ground is cast into shadow by a the wide hip of the land. I pace into the gloom of that moonless realm, turn around, and walk the moon up again.

That’s two moonrises tonight, I think to myself…or three? Or does the first one, over the horizon count if I wasn’t watching? In any event, not bad for one night.

Returning home with the moon in my eyes, I catch up to the ridge-shadow below the house, which has shortened considerably. As I pass into its shade, the moon sinks into the black bristles of the pines. I stop, step back a few paces, and lift it up again.

What fun, I think. I could do this all night.

But of course I can’t. The walk has been lovely but this moon-lifting is tiring and I’m ready to put my feet up again. My wineglass is waiting. The angle of the moon’s light as it glides toward lunar noon is erasing the margins of shadow thrown by folds in the landscape. The boundaries of more-light and less-dark I’ve been playing in are vanishing as the moon lifts itself out of my reach.

April 5, 2019

Mud

Griping about it seems peevish if not gallingly insensitive while a good portion of the nation’s midsection is suffering from the effects of widespread flooding, but I feel compelled to offer a few words on the topic of mud.

The thing is, we don’t see it much. In these parts, mud is a relative rarity. Its lack is one aspect of life on high ground: we live on terrain that tends to be anything other than flat. Water is inclined to be elsewhere, namely someplace downhill.

Meltwater pooled in rock.

The elevation of our place is such that we are the source of silt and sediment rather than the recipient of it. The dearth of flat terrain offers scarce habitat for pooling water; ushered downslope by gravity, water leaves the area at a pace that’s not usually conducive to canoodling with dirt long enough to create muddy progeny.

A puddle less conveniently located; at its height it covered the road.

Come to think of it, we don’t have an overabundance of dirt in the first place. Soil is slow to form in this semi-arid climate, with lush growth and speedy decomposition deterred by a lack of rain and humidity. Much of what passes for soil here would be referred to as fine gravel most other places: it is gritty, grainy, and non-absorbent. Water percolates swiftly through, filtering into hidden fissures. The sere air sucks moisture fast, too, with precipitation quickly met by evaporation.

Although we didn’t receive the dumps of snow that fell on some regions of Colorado this winter, a lot of what did fall, from October on, stuck around. When temperatures finally began to ratchet up and stick around long enough to melt accumulated sheets and drifts, still-frozen ground helped hold the resulting meltwater on the surface.

And so: mud happened.

Portions of the driveway walked through the garage and onto the doormats with each return trip from the barn or woodshed. No matter how often I vacuumed the rugs, wee chunks of grit and glittery mica-laced fines migrated upstairs, crunchy on wood and tile.

Mud art on the back window of the truck’s camper shell.

The local roads caked into wheel wells and splattered up car doors. Dust from drier sections of road between home and pavement wetted in the grimy spray thrown up on wet stretches, forming swirly red patterns on the back of the truck, an unplanned experiment in fluid dynamics.

The driveway and the road puddled and rutted. Under other circumstances, I might have been able to convince myself that the goo weighting down my boots every time I went outside was a good workout, but conditions were slick and a bout with the flu left me tired and very, very cranky. Going for a walk was singularly unpleasant there for a while; the roads were gloppy and slippery, the grasslands treacherous with crusted layers of old rotten snow or sheets of lumpy ice.

Braving the ick, after the mud began to dry.

The horses squished around, also cranky, mincing through the unstable and foot-sucking black grease around their feed tanks with ears pinned flat. That area is one of the few flat spots on our place, which makes it both a convenient feeding station and a logical location for the driveway. The downside is that it’s just below the crest of the ridge, which invites the drifting of snow. In the eons before we arrived, the extra moisture from winter drifting encouraged grass, yielding a nice layer of topsoil. That rich black earth, churned by the horses’ hooves, creates a boggy mess when it’s wet. Poor Moondo, who is fussy by nature and also now elderly and less steady on his feet, was particularly distressed by the glop. He would try to edge along on the drier grass next to the fence, or totter along the icy edge of the decomposing snowdrift. I watched him wallow through the drift one day, testing a route through crusty snow. I guess high-stepping his sore arthritic knee through the snow was worse than the mud, because he went back to picking his way through the goop.

Within a couple of weeks, though, the ground opened up enough to draw the water down from below, while the wind did its work from above.

“Mud? What mud?”

Ruts hardened on the road, and now jostle our vehicles like train cars switching tracks. Footprints sploodged into mud have hardened like ancient petrified trackways, documenting our perambulations. I finally washed my car a few days ago, leaving a red outline in the wash stall down in town, a few pounds of sediment fast-tracked from the high country to an elevation three thousand feet lower.

###

March 8, 2019

Winter Pasture

There’s a distinct pleasure in being able to make someone else happy. Sometimes their pleasure persists even as your own memories of the effort involved in said happy-making fade, tipping the scales of your satisfaction even further toward the positive.

There’s a distinct pleasure in being able to make someone else happy. Sometimes their pleasure persists even as your own memories of the effort involved in said happy-making fade, tipping the scales of your satisfaction even further toward the positive.

In the spring of 2018, almost a year ago now, I was getting started on a project that’s still making the horses happy: stringing fence around some acreage we had long planned to use as a winter pasture.

As with most improvement projects hereabouts, this was a slow process, starting with hiring a fencing crew. The new pasture occupies part of a flat plateau west of our house, and I suppose it’s a general rule of geography that high ground tends to be high because it’s hard: rocky or otherwise resistant to the patient forces of weathering and erosion that help render low ground low. The fencing guys cheerfully assured us they’d have no problem with the rocky ground, but when they left there were about two dozen T-posts strung out along the “fence” line, evidence that their jackhammering wasn’t all it was cracked up to be.

The next summer, we hired our problem-solving fellow, the guy who’s always willing to help us come up with solutions to unusual problems. He spent a couple of days forming up and pouring square concrete bases for the prone posts, getting them upright where they belonged.

It was another eight or ten months before I got going on my part, which was stringing the lines to complete the fence.

One of the things I like about the Electrobraid fence material we’ve been using for fifteen years now is that all the tools I need to string and maintain the fence fit in a two-gallon bucket. The spools of cable are light enough for me to carry by myself, too, so I can work on the fence independently…which, let’s face it, can be translated as “when I get around to it.”

Spring was already arriving by the time I got around the winter pasture, but oh well. I would go out for an hour or two on nice afternoons when the March wind wasn’t howling. By the time I was done I had walked that fence line dozens of times: placing insulators, unspooling cable for each of the three strands, splicing and terminating, connecting and grounding and tensioning.

When I let the horses out into their new pasture, it was pretty obvious they were happy, although theirs was a gustatory sort of joy, not high-heeled bucking and running and kicking. I led them up to the now-open gate, stepped through, and invited them to follow. They both threw me an incredulous look—“Really? Out there??”—and dropped their heads. Their butts weren’t even beyond the gate opening before they started eating.

For the rest of the spring and early summer, they spent most of their days—pretty much any time the wind wasn’t ripping, actually—out there on top of the ridge, noshing on cured bunchgrass that hadn’t been grazed by livestock in a couple of decades. Rather than getting fat, though, the horses got fit. The new pasture is a good half-mile walk from the waterer here near the house. The horses would march purposefully down for a drink five or six times a day, and then head just as decisively back out. When the vet came to administer spring vaccines in April, she had nice things to say about muscle tone, especially with Moondo, who is an older fellow for whom the extra movement is a great benefit.

I was a little worried when we closed the gate come summer, afraid the horses would resent being denied their new favorite hangout, but by then the grass had rebounded in their regular pasture, and they seemed content to focus their attentions there.

None of which is to say they weren’t conspicuously happy when I re-opened the gate in November.

I can’t see in to the new pasture from the house, so when the horses are up there I can’t look at them through binoculars, spying on them from my office as they nap or graze or play together. If I walk out to visit, though, or stop on the road as I’m coming in or going out, it’s hard not to think how content they look.

Sometimes I feel dumb about how happy making these two horses happy makes me. Particularly on days when I’ve been sunk in a fog of gloomy news or am pinching my nose hard against the miasma of human pissiness, I know life, and the world, is vastly more complicated. I know there’s at least one angle from which all this looks like avoidance or denial. I could—and feel like I should—try to account for some of the realities of privilege and lifestyle, for the effects of fences and domestic equines on wildlife and native grasslands.

But when I see—or even just think about—the horses hanging out, enjoying being in their place, I think, well: maybe it really is that simple. At least once in a while.

December 31, 2018

Top Twelve Books of 2019

No, that’s not a typo.

I know this cusp-of-the-new-year timeframe is a popular time to spotlight favorites and best of’s and top tens from the year about to pass, but I’m in the mood to look forward, not back.

A couple of years ago, I started gathering references to books I wanted to read together in one place, instead of rat-holing sticky notes and review clippings in various piles and cubby-holes where I would find them much later and never when I was in a bookstore or library. It has lately occurred to me that this list of books TO-READ just might be growing faster than my HAVE-READ list, which would seem to be a problem.

The obvious remedy is to get more books off the former list and onto the latter one. Rather than being paralyzed whenever I scroll through all those titles, I’ve decided to play favorites in a moment when I’m not looking for something to read, selecting a (hefty) handful of titles to get started with. Twelve seems manageable–more ambitious than ten, while still leaving plenty of room for serendipitous browsing or referrals from friends.

Without further ado, then, and in no particular order, here are twelve books I have every intention of reading in 2019. Some are by lesser-known authors, and a few have been out for a while. I’ve tried to give myself some variety, including titles that are relevant to my research, some that just intrigued me, and a few that I’ve been meaning to read for too long. You might find something here to add to your own TO-READ list…unless yours is also getting too long.

I’m not going to promise that I’ll get every one of these read , but I’m gonna try. I’ll meet you here around this time next year, and we’ll see how I did.

Scienceblind: Why our Intuitive Theories About the World are So Often Wrong, by Andrew Shtulman.

Quite possibly a “need-to-read” rather than a “want-to-read,” since this book promises to be highly relevant to my own work-in-progress, which is about scientific literacy. But it also just sounds interesting.

Sawbill: A Search for Place, by Jennifer Case.

One of the many advantages of thinking of myself as a writer is being able to justify going to writer’s conferences, where I meet cool and interesting people. Having met Jennifer and from reading some of her shorter essays, I know she’s a keen observer who has done deep thinking about place-based writing.

Where Bigfoot Walks: Crossing the Dark Divide, by Robert Micheal Pyle.

This one makes the list because the subject matter is exactly what I usually wouldn’t read. Pyle is an erudite and generous writer, though, and I’ve been starting to catch myself up on his books. I got to see him give a reading in Salida, CO in November. It’s hard to fault a naturalist/realist who, in this day and age, can make you laugh while admitting that we all have good reason to cry.

Known and Strange Things: Essays, by Teju Cole.

Because: essays, and I love essays. A new writer for me, too, and so maybe the best kind of book.

The Writer’s Eye: Observation and Inspiration for Creative Writers, by Amy E. Weldon.

I try to read one or two writing craft books a year, to remind myself how much I don’t know. I met Amy at the same conference where I also met Jennifer Case, so I guess this is sort of a theme running through the books I selected to push to the top of my reading list: to catch up on the accomplishments of friends. Besides that, Amy is wicked smart, crazy hard-working, and an insightful commentator on the effects of digital media, a topic that befuddles me almost to the point of paralysis.

The Biological Mind: How Brain, Body, and Environment Collaborate to Make Us Who We Are, by Alan Jasanoff.

Another book that’s likely relevant to my current writing project. I’m intrigued, too, because I’m a bit of a neurology nut, and this one looks like it might cross over to pick up on my place-based writing interests as well.

Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World, by Maryanne Wolf.

I read Wolf’s Proust and the Squid several years ago, and it might be a tough act to follow, since the earlier book thoroughly altered how I think about writing and reading in this, our computer age. As I said above, the digital universe baffles and befuddles me, even as I wallow around and try to make my way in it. As I also said above, I’m a neurology nut. I’ve been thinking I should re-read Proust and the Squid, but will try this new one first.

What is the What, by Dave Eggers.

I have some fairly entrenched reading habits. This book ventures outside of pretty much all of them. Which may be why I’ve been meaning to read it.

The Library Book, by Susan Orlean.

I always use the library as often as I should…which might be why that TO-READ list has gotten out of hand. Among other things, I include this one as a reminder to seek out some of the books on this present list at a venerable lending institution near me.

Ordinary Light: A Memoir, by Tracy K. Smith

Smith said this in an interview I read a couple of years ago: “I think any poem, no matter the topic, is an endeavor to get to whatever sits behind what we think we know or what we have learned to name.” If I could put a lofty label on how I’d like to write, “Endeavoring to get behind what I think I know” would be it. Also, I indexed a book several years ago by Smith’s husband, Raphael Allison, so even though I don’t know Smith, I can claim this funny kind of connection.

Coyote America: A Natural and Supernatural History, by Dan Flores.

I usually read a lot of natural history, so I need something in that vein to round out my target list. I’m seeing coyote tracks in the snow every time I go outside lately, so this seems like an appropriate pick.

The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire, by C.M. Mayo.

I don’t read a lot of fiction, but I loved Mayo’s travelogue about Baja Mexico, Miraculous Air. She is another scary intelligent and freakishly hardworking writer that I know personally, and it’s possible that I want to read more of her work in hopes that some smarts and diligence will rub off on me. Visit the Madam Mayo blog if you’d like to wander in the company of a brilliant and quirky guide.

December 20, 2018

Not an Owl

Having fresh snowfall is a bit like getting a local newspaper delivery: I learn about things going on in the neighborhood I wouldn’t otherwise know. Tracks on the fresh sheet of snow spread across the arena last month were like a headline, albeit one in a script I couldn’t read. But given that the track set appeared to have dropped from the sky—no trail in, no trail out—I knew that the language was avian, not mammalian. On closer examination, I learned that the author was a large bird. The tracks were almost three inches long, with dragging nails that joined one mark to the next like the pen strokes connecting letters in cursive writing. Here and there, dense scribbles tore through the clean sheet of snow to the underlying sand of the arena.

Having fresh snowfall is a bit like getting a local newspaper delivery: I learn about things going on in the neighborhood I wouldn’t otherwise know. Tracks on the fresh sheet of snow spread across the arena last month were like a headline, albeit one in a script I couldn’t read. But given that the track set appeared to have dropped from the sky—no trail in, no trail out—I knew that the language was avian, not mammalian. On closer examination, I learned that the author was a large bird. The tracks were almost three inches long, with dragging nails that joined one mark to the next like the pen strokes connecting letters in cursive writing. Here and there, dense scribbles tore through the clean sheet of snow to the underlying sand of the arena.

I was thinking owl, imagining the hunter dropping down onto an unsuspecting vole or mouse burrowing under the surface of the snow. A niggling protest from the back of my mind pointed out that there weren’t any rodent burrows evident where the bird had been, even though such excavations were obvious elsewhere. I pushed the thought away, along with the obnoxiously reasonable question of why an owl would wander around rather than striking and lifting off.

Another set of tracks appeared in front of the house a day or two later. There, too, the visitor left doodles and rummaged down into the snow in spots. The snow’s surface was crusted by then, hard enough to hold up the bird and capture impressions of the knobby joints of its feet. Many of the footprints showed an asymmetry in the alignment of the middle toe.

Back in the house, I checked my Peterson Guide to animal tracks. The author, Olaus Murie, concedes that birds merit only “some passing attention” in a guide devoted principally to animals, but the field sketches, complete with the offset middle toe, suggested a raven rather than an owl. I was more than a bit disappointed, and turned to the internet hoping to have my preferred preconception confirmed, but there too the evidence pointed to family Corvidae rather than Strigidae (typical owls) or Tytonidae (barn owls). I learned that owl feet (and hence their tracks) are zygodactyl; that is, comprised of a pair of toes pointing forward and a pair pointing back, although one ostensibly backward-pointing toe tends to jut out to the side. Ravens’ feet are anisodactyl: three toes out front and one to the back.

So my tracks were left by ravens.

So my tracks were left by ravens.

I’m not going to lie. I was disappointed. How cool it had been to think we’d been visited—twice!—under cover of dark by a shadowy silent predator.

But no. Just ravens.

Rationalizing my dismissiveness, I told myself that I liked the owl storyline better because owls are more rare. Corvus corax, the common raven is…well, common: I see them pretty much every day. This fact alone should have tipped me off that the track sets would almost certainly be left by a raven and not an owl, but such is the nature of bias. We see what we prefer, not what is real, or most likely.

I suppose I might have learned something new if the headline written on the arena had indeed announced a visit from an owl, but it’s more likely that, with my theory confirmed, I would have closed the mental book on the topic. As it was, uncertainty held my attention.

In researching the tracks, I learned a few new things (zygodactyl, anisodactyl); was reminded of some others (I watch ravens, but the ravens also watch me; they don’t hop with feet parallel but use a walking gait—and do so quite a bit for an animal capable of flight); and began to wonder about yet other things (why dig in those spots? Food, most likely, but perhaps not; perhaps, literally, just poking around? If a raven wrote a blog, what would it blog about?)

So, yeah, maybe it’s okay that it wasn’t an owl after all.

So, yeah, maybe it’s okay that it wasn’t an owl after all.

Postscript: unless you are willing to piddle away a day, don’t start looking for information on Corvids online. Ravens are smart. Crows hold grudges and attend funerals, Clark’s nutcrackers have capacious memory skills, and gray jays will make you rethink the uses of saliva.