Matthew Lewis's Blog, page 5

March 4, 2015

Richard III and The Catholic Herald

This blog is written in response to an article that appeared on the Catholic Herald website and can be found here: http://www.catholicherald.co.uk/commentandblogs/2015/03/04/richard-iii-fans-are-the-medieval-equivalent-of-911-truthers/

The article is entitled ���Richard III fans are the medieval equivalent of 9/11 truthers��� and displays a portrait with the caption ���Richard III: a monster���. So we���re pretty clear where this is going. This type of article is hardly unusual but I thought this time I���d put the record straight, for a number of reasons.

Ed West, the author of the piece and deputy editor of the Catholic Herald, then launches into a savaging of Richard III that traditional historians would be proud of. It isn���t hard to work out where the ideas come from as Mr West announces that he has read Dan Jones��� recent Wars of the Roses tome The Hollow Crown. Interestingly, he mentions The Daughter of Time but doesn���t appear to have read it, nor does he reference any revisionist history to offset the known dislike Dan Jones maintains for Richard III.

It is asserted that attempts to review Richard III���s reputation began in the early 20th century with the foundation of The Fellowship of the White Boar. It is not such a new phenomenon. Sir George Buck published his revisionist The History of King Richard the Third in the early 17th century. Jane Austen famously wrote that she felt Richard III had been hard done to by history, musing;

���The Character of this Prince has been in general very severely treated by Historians, but as he was a York, I am rather inclined to suppose him a very respectable Man. It has indeed been confidently asserted that he killed his two Nephews & his Wife, but it has also been declared that he did not kill his two Nephews, which I am inclined to believe true; & if this is the case, it may also be affirmed that he did not kill his Wife, for if Perkin Warbeck was really the Duke of York, why might not Lambert Simnel be the Widow of Richard. Whether innocent or guilty, he did not reign long in peace, for Henry Tudor E. of Richmond as great a villain as ever lived, made a great fuss about getting the Crown & having killed the King at the battle of Bosworth, he succeeded to it.���

Mr West summarises the Wars of the Roses as told by Dan Jones as ���mostly a good fun read about aristocratic psychopaths chopping each other���s heads off��� before warning that ���the story becomes very, very dark in April 1483���. Richard seizes the throne, kills Rivers, Grey, Vaughan and Lord Hastings and then, following Dan Jones��� conclusions, all but definitely murders his nephews. Richard���s coronation feast is meant to appear disgustingly opulent when it was, in fact, an integral part of a coronation until 1830 when William IV abandoned the idea as too expensive. Elizabeth Shore wasn���t paraded at the coronation, she was made to walk through London from St Paul���s as penance for harlotry and then put in prison, and all of this had more to do with being Edward IV���s mistress than Lord Hastings��� (and Edward IV���s stepson Thomas Grey, Marquis of Dorset too for good measure).

Let���s take a little look at how much darker things really got in 1483. Four men died to secure the throne for Richard III. Precisely four. Hastings, Rivers, Grey and Vaughan. None of these executions were illegal, whatever anyone may say. Richard was Constable of England and entitled to execute men for treason based on evidence that he had seen. Whether Richard was rightfully king or not, just four men. Thousands and thousands died to win the throne for Edward IV. Towton was a truly dark day. Thousands more perished to prise him off and see Henry VI restored only to have Edward IV back in place six months later. Who then was rightful king? We are seriously supposed to believe that four deaths are worse than many thousands. Four lives lost by men at the heart of the political turmoil threatening England are portrayed as being worth so much more than thousands of innocent men dragged from field to field around England to fight battles that had nothing to do with them for lords who didn���t care about them. I don���t buy that.

Even if we allow that he may have killed his nephews this is only so distasteful because of their ages and ignores a long history of murdering political rivals. If he did it, it is inexcusable, but it isn���t the only stand out crime of history, as it is painted by those convinced of Richard���s monstrous presence, haunting the annals of England���s history. Arthur, Duke of Brittany, a nephew of King John with a stronger claim than his uncle, mysteriously disappeared in 1203 after being imprisoned at Rouen by John. No one talks about this mystery. In 1470, just before he lost the throne, Edward IV had some of Warwick���s men executed. John Tiptoft, then Constable, oversaw the trials. The men were beheaded and then impaled on spikes, left on display with their severed heads atop the spikes driven through their backsides. When Charles II became king he had Oliver Cromwell and others exhumed, their rotten corpses beheaded, the bodies thrown into unmarked pits and the gory heads placed on spikes at the end of Westminster Hall where the men had sat in judgement on his father. This after promising no retribution. The murder of the Princes in the Tower, if it happened, has obtained such currency not only because it involved children, but because it is a morality tale that suited the Tudors and subsequent generations. Whenever the story rears its head there is an important context to consider.

Richard���s illegitimate children are given a mention to further smear his character. That Richard ���fathered several illegitimate children��� is a stretch. It was two (that are known of), both believed to have been born before he was married. John and Katherine were acknowledged as his natural children and provided for. Is that not to be applauded? No mention is given to Edward IV���s four or five illegitimate children, nor to the record of (approximately) 24 fathered by Henry I. Of course, mention of this would make Richard look positively chaste and that isn���t the aim of the article.

All of Richard���s well attested bravery and progressive legislation is given a cursory mention, but only to point out that it all counts for nothing because, at the end of the day, ���he murdered his nephews���. Somewhere, we lost the ���probably��� or ���I would conclude from the evidence���. This is something that always frustrates me. I can���t tell you that Richard III didn���t kill his nephews. I don���t try to. I like to explore alternatives, but it is undeniable that if they died, Richard is the prime suspect. This does not make him guilty, but neither can he be proved innocent. When Dan Jones tells you Richard did it, he���s offering his opinion, nothing more. The same is true of Alison Weir. Educated though it may be, it remains an opinion rather than a fact. We are confidently informed that by late 1483 ���everyone thought the princes dead���. Oh, apart from Henry VII who was worried by several pretenders until the end of the century. And apart from Sir William Stanley, executed in 1495 for saying that he would not fight against Perkin Warbeck if he really was the son of Edward IV. I could go on, but it was not a known fact then, and it isn���t now.

We are told that the ���odd thing about Ricardians is how unlikely Richard���s innocence is���. It is this that makes us ���late medieval equivalents of 9/11 truthers���. I���m sure that���s meant to be an insult, but if being accused of looking beyond someone else���s superficially presented opinion to explore an issue and reach a well-researched, well-reasoned conclusion of my own is an insult I���d suggest that this would say more about the article���s author than me. Fear of the truth and of investigation are hardly pinnacles of freedom and democracy. That conclusion, when reached, may well be that Richard did do it. Most Ricardians will freely concede that the possibility, perhaps even the probability, cannot be denied. Re-evaluation is what Ricardianism is about, not whitewashing. Some hold the view that Richard was innocent more passionately than others, just as some, including traditionalist historians, cannot see beyond his guilt to discuss the matter openly.

For me, the odd thing about traditionalists is their unwillingness to re-evaluate anything. For every Facebook group in which you will be rounded upon for accusing Richard of the murders there is another in which any mention of his innocence will be equally strongly opposed.

Mr West should perhaps read a few more books that might balance his views before peddling incorrect fact and second hand opinion. The same could be said for many people on both sides of the arguments. Catholics have been moved and upset by the lack of Catholic rites planned for Richard III���s re-interment but The Catholic Herald does not embrace the religious aspect of this debate but chooses instead to judge and condemn a man they demonstrably lack the knowledge to legitimately pillory. Ask questions, investigate possibilities, offer opinion. Don���t present poorly formulated conjecture as fact.

February 8, 2015

Book Review – Loyalty by Matthew Lewis (Audio Book)

A very very nice review of the audiobook of Loyalty from The Henry Tudor Society.

Originally posted on The Henry Tudor Society:

Originally posted on The Henry Tudor Society:

By Nathen Amin

I should start this review by pointing out that I do not enjoy audiobooks and can certainly not be considered sympathetic to Richard III or the theories of Ricardians. That being said, when I came across an audiobook on the subject of Richard III I couldn���t resist giving it a listen.

Loyalty by historian Matthew Lewis was first published in 2012 and has been well received amongst historical fiction aficionados, currently receiving on average in excess of a 4-star rating from over one hundred reviews on Amazon, an impressive statistic and indicative of its quality.

The book has been praised for its intriguing plotline that unusually takes place across two notorious reigns ��� that of Henry VIII and Richard III. The premise is that Tudor court artist Hans Holbein is summoned to the house of Sir Thomas More for a commission. Whilst in the presence of More���

View original 767 more words

December 24, 2014

Merry Christmas? It Is Now!

I just wanted to offer everyone a quick update regarding my son. It is good news, so bear with me! The messages of support and prayer after my last blog about him were so touching and meant a great deal to all my family.

We found out a few weeks ago that he had not in fact had viral meningitis. The lumbar puncture test showed no sign of the infection. We were then in the distressing position of learning from his consultant that they were looking at either a condition so rare that it only affects about 20 people in the world and which they have never treated, or tumour re-occurrence with talk of biopsy and treatment if that were the case.

Needless to say, it was terrifying news. Nick was due to have a more detailed than usual MRI scan early in December, but the scanner broke down in the morning and it had to be moved on a week. His consultant’s appointment also had to be moved on to yesterday, 23rd December. All of that put a bit of a dampener on Christmas preparations. He spent two and a half hours in the MRI scanner and we, along with the friends we are blessed with, have been praying (in our case frantically) for a good result.

We saw the consultant yesterday and it was the best news we could have hoped for. The scan was much improved. The areas of concern from the November scan had returned to normal. They now believe he has a condition called SMART – Stroke-like Migraine Attacks after Radio Therapy – a late effect of radiotherapy which is so rare that there isn’t really a treatment regime. Given the alternative to this, it was a relief and the best we could have wished for. Nick has once again faced all of this with his now customary strength and bravery.

We owe a huge debt of thanks to all of our friends, and to two in particular again. To everyone who sent messages of support and prayer through this blog and on social media, we cannot thank you enough. If anyone is looking for a demonstration of the power of prayer, you have it here. When Nick was originally poorly we used to joke (although how funny it is I don’t know) that God would save him just to get everyone that was praying for him to quiet down, such was the powerful response to his illness.

Thank you too to all of the amazing doctors, nurses and staff at the hospitals where he has been looked after. Their care has been faultless and I have nothing but praise for every single individual and the team of care and dedication that they make up.

I also need to say a huge thank you to the man upstairs. I have begged him for this outcome, one voice amongst many, and I believe that He has heard our prayers and answered them. My debt to Him increases and I still have no notion of how to pay it back beyond thanks, love and trying to live my life in a way that would make Him proud.

Well, it’s Christmas Eve. I hope that this is a positive message for you as we all hold our breath for the main event tomorrow. I wish every single one of you a Merry Christmas and the happiest of New Years. Enjoy the festive season. Forget the presents for a moment and enjoy the time and the company. Raise a glass over dinner to the real reason we celebrate. It’s Jesus’s 2014th birthday and he’s still going strong. Maybe take a mince pie to a neighbour or pick the phone up to a relative you haven’t spoken to for a while. If you know someone who’s on their own, give them ten minutes of your day. It just might mean the world to them.

As Tiny Tim says ‘God bless us, every one’.

And He will, you know. Just believe, and ask.

Merry Christmas everyone, and thank you.

The Lewis family

December 3, 2014

Richard III’s Remains Rumble On

So, there’s more news and more debate on Richard III’s remains, two years after they were discovered. It seems his story, as well as his bones, cannot be laid to rest. At least I welcome the first of these two things.

We are now to be 99.999% certain that the remains found under the Leicester car park are Richard’s. We can also be quite confident that he had blue eyes and that, at least as a child, he had blonde hair. I have to confess that this changes my mental picture of him a little, but it’s at least news.

The fact that there are two breaks in the paternal line is also news. Of a sort. Someone, somewhere (well, okay, two people), in the course of four centuries was unfaithful. I’m not sure that’s really news. That rate is beaten on a daily basis on Jeremy Kyle. It’s interesting, but the report can’t point to which branch of the family has the break, whether it was before or after Richard III, and it could run into the 18th century as easily as date back to the 14th.

What does this mean for the current royal family? Nothing.

What does it mean for previous monarchs? Nothing.

What does it mean for the Tudor’s legitimacy? Nothing.

It’s no more questionable than before!

What is being overlooked at every step is that no monarch has ever been illegitimate. The current Queen is selected and ratified by Parliament, not by her father or the blood in her veins. This has been true for several hundred years now.

More importantly, the coronation ceremony, in which the monarch is anointed with holy oil, appointed before God and swears their oath, corrects any flaw in a monarchs title. If I was anointed King, it would be beyond doubt that I would be the rightful king. The action of anointing has created a monarch for centuries.

Henry Tudor claimed the throne of England thanks to his defeating of the reigning king. His blood meant nothing. The same was true of Edward IV, who deposed an anointed king. And Henry IV, who was the first to break the Plantagenet line of descent. Even William the Conqueror became king in this manner, yet we doubt none of them as monarchs. In each case, the coronation ceremony corrected any flaw in their right, title or blood.

Had Richard III decided to allow his nephew Edward V to be crowned and anointed, he would, in the eyes of canon and common law, have been the legitimate king. The marking of the cross on his forehead with holy oil would have driven any fault and any doubt away.

The same is true of the Queen today. It is sensationalism for sensationalism’s sake to question this.

There have been several rumours about illegitimate medieval royals. John of Gaunt, third son of Edward III used to fly into rages at the contemporary rumour that he was a butcher’s son. The fact that Edward III did not attend his birth is cited as evidence that something was amiss.

Edward IV was rumoured in the French court, and later in England, to have been the son of an archer named Bleyborne, a huge man whose frame matched that of the tallest king in English and British history. Edward’s father’s departure on campaign eleven months before his birth is also suspicious, if no chance of his return were possible. Edward was christened in a quite ceremony in a side chapel. Yet Edward’s coronation corrected any flaw that may have existed. That is probably part of the reason Richard III switched his allegations from questioning Edward’s paternity to challenging the legitimacy of his children. Edward IV had been anointed. Edward V had not. His flaw was raw, uncorrected.

What does this mean?

At the most, it suggests that every castle had a tradesman’s entrance.

What does it mean for the Queen’s position?

Nothing.

Nothing at all.

November 29, 2014

Everyday Heroes, Heroes Everyday

This post is something of departure. It has nothing to do with history and is very personal. I am writing it because I made a promise over the last week or so. This is part of the fulfilment of that promise.

I won’t go into too much detail, but my son has been quite unwell for 11 years now. He had a brain tumour and seven spinal tumours aged 7. He had surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. He has lived with the consequences of these things for a decade, but he has lived. He is at college now. My believe in God and His power to affect our lives has always been with me, a part of who I am. Eleven years ago it was put to the test, and it did not wither. It blossomed.

Having just spent a week in hospital with suspected viral meningitis, he is now on the mend. When he had three seizures in as many hours, my first instinct was panic, but it was closely followed by one to pray. Utterly desperate prayer, but I needed to pray.

The absolutely amazing doctors and nurses sprang into action all about. I was lost on a tiny, dark, island of helplessness. I could do nothing. I was unable to contribute anything to his physical care. That’s a horrible feeling, but then I began to pray. Just as I had hit the emergency button to call for help from the medics who poured into the room, I hit the emergency button in my soul and called upon more help. And I believe that too poured into the room.

I called our friends. No. Friends simply doesn’t do these two amazing people justice. They know who they are, but I don’t know a word to sufficiently describe what they mean to us. They prayed, and they asked others in their church for prayers too. This may be lost on some people, it was not on us.

My faith is strong. I feel it challenged too often for my liking, but it’s not about my liking. I’m weak enough to find doubt hammering at my faith like a wrecking ball sometimes. But my faith is stronger than any doubt, stronger than me, and it does not fall. Without it, I don’t know what the last decade would have been like, but I believe it would have been even worse than it was. I believe that God saved my son. I do not seek to demean or belittle the incredible work of the surgeons, doctors and nurses who treated him. I simply see God’s hand in their work. Mankind is obsessed with understanding every single detail of our world. We never will. It is in that percentage we cannot explain or quantify, however small it is and however it diminishes, that I believe God is.

I am surrounded by heroes. I think I am the extraordinary one for being ordinary. Doctors and nurses spring into action to fix the physical. Family, the best friends a man could hope for, and the community of a church who don’t really know us, but open their hearts and give their prayers for my son, heal every bit as much as the medicine and the care that surrounds him in the hospital. The two are never at odds in my mind. They complement each other perfectly.

My son never complains. He never refuses a treatment, however often and however unpleasant. He is beyond brave, he is beyond strong. He is a hero who approaches life with a joy and enthusiasm that defies the challenges it constantly levels at him.

My other children are a forgotten brand of hero. They keep life going. Their presence and love is nourishment and comfort. Their steadfast strength, care for their brother and ability to cope astounds me. They are the rock upon which I face a tidal wave, certain it cannot reach me. They have been deeply scared by all that has happened, those most terrible of scars that no one can see, but they remain perfect and precious. Their contribution is no less than the doctors and nurses who treat him. A cheeky message from a sibling is a morsel of normality when there is nothing familiar to reach for, a torch grasped by desperately seeking fingers in the terrifying darkness.

People are heroes. God is their superpower. You don’t have to believe that for it to be true. My faith doesn’t need validation or approval from anyone but God. Yet I know plenty will think it folly to believe in such things in this modern age of science and medicine, engineering and progress. There often seems to be a choice between God and the modern world, as though He has no place in it, as though He has to justify our belief in Him. Why can’t the two go hand in hand? Faith is an old fashioned concept, out of time. This couldn’t be father from the truth.

All of this leads me to ask a question: What is faith in the 21st century? For me, it’s personal, but defines the person people know me as. I don’t want to bash anyone with faith. It’s the wheels that keep me moving, not the bright paintwork. If you don’t see it, it doesn’t mean it isn’t there. My faith steers me and the way I live my life is the demonstration of my faith. Ministry is important, vital even, but there is more than one way to achieve it.

I want people to think of faith as a soft cushion when life is uncomfortable. It’s jelly and ice cream when you’re feeling unwell. It is the reason I am. It is the reason I do. It is the reason I am thankful, because I do not see God at work when things go wrong, I see Him at work in how thinks turn out. My wife always says that all prayers are answered. The answer just isn’t always yes. That is when faith is hardest to have, when it is tested the most, and when it is most needed. I can’t explain why bad things happen. No one can. For every one that it is tempting to think God should have stopped, I wonder how many He did prevent without anyone even knowing. Who thanks Him for those?

Faith is different to religion. Religion is the group expression of faith, regulated by carefully structured and often fiercely guarded doctrine. Church is an amazing place, but I don’t buy any of the denominational doctrine. I know plenty do, and I respect that. I believe God can hear you, however you speak to Him and wherever you do it. I don’t believe there is a wrong way to worship Him. Worshipping Him is always right. I am often dismayed that doing the same thing in a different way can be a cause for argument and war. Jonathan Swift had it right in Gulliver’s Travels. It’s really like an argument over which end of an egg you should crack. It simply doesn’t matter. You still get egg. The furious argument is wholly manufactured. By whom, when, why and how are all forgotten. Just the argument remains, now self nourishing, set in perpetual motion, and deemed essential in spite of no one knowing why it should be necessary. However you name God, and however you worship Him, it only matters that you do so. This is the bridge that we should build to connect us, not the armed roadblock to be thrown up to keep us separate and desperate when neither are required. Faith should unify the world. Religion instead all too often divides it. We, as human beings, have focussed on, and continue to focus every day upon our differences, and ignore what draws us together.

I have no issue with people of different colour to me, different religion, different sexuality, different political views. I have no issue with these things because that would be to focus on what makes us different. The point many will make is that religious texts order us to despise these differences. Nonsense. Can you really say that you believe in a hateful, spiteful God? I fear Him, of course I do, but I have faith that he will love me as long as I am trying to do right. He doesn’t see success or failure, He sees your intentions. That is what exists only between you and God. And between every other person around you and God. That unites us. It is not my place, nor is it yours, to judge. That power and right is reserved for God. I will not spend my life determining who I am better than, who I am more entitled to God’s love than. That is between them and God. What is between me and God is the way I live my life. Do I choose to live it in hate and judgement, or in love and acceptance, deferring to God that which is His anyway?

I heard a sermon once that I found incredible in its simplicity. The Old Testament speaks of an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. It excuses, perhaps even encourages, vengeance to a level equal to the hurt inflicted upon us. Or does it? It is equally possible that this was the enforcement of a limit upon revenge rather than an encouragement to it. You may take an eye for an eye, but no more. The limit was required to prevent spirals of vengeance running out of control rather than to encourage the seeking of retribution. It was hope, that one day such a limit would no longer be required because there would be no hate. We still have that hope. It is a mark of human interpretation that we choose to see entitlement to bloody, gory revenge rather than a limitation upon it born of hope.

What is faith in the 21st century? It’s precisely what it was in every other century. It is belief in love over hate. It is hope in the victory of what connects us over what divides us. It is comfort in a hard world. As we push ever forward, what are we trying to reach? Truth? Knowledge? Power? Are we not reaching for God, even if we have forgotten that is what we are doing?

I believe in the power of prayer. I know what God can do. I pray. Because I am human, I worry that it isn’t enough. But I have faith and support. That, to me, is religion.

November 15, 2014

KRIII Visitor Centre Review

I have heard plenty about the King Richard III Visitor Centre in Leicester. Some positive, including the recent architectural award that the centre won, but plenty that was less complimentary. I finally made it there to judge for myself with my daughter and, for those who may be interested, here are my thoughts on the exhibition, entitled Dyansty, Death and Discovery.

Richard III Statue outside Leicester Cathedral

After buying our tickets, the first room to which we are directed is a flag stone floored chamber containing a throne, on which sit two discarded roses facing defiantly away from each other. This room offers an introduction to the Wars of the Roses from key figures in the live of Richard III – Cecily Neville, his mother, Richard Neville, the Kingmaker Earl of Warwick, Richard’s guardian as he grew to manhood, Vincent Tetulier, an armourer creating harness for Richard, Anne Neville, Richard’s wife and Edward IV, his brother and king. The brief tales they tell us mark stepping stones in Richard’s passage through the Wars of the Roses.

The Roses on the Throne

The throne was a cause of some controversy, with talk of the floor running with blood as a marker of Richard’s crimes. This was most likely taken out of context. Throughout the video, landmarks of the Wars of the Roses are projected onto the floor before the throne – the Battle of Towton etc – and shadowy blood seeps down from the throne. This very clearly relates to the prolonged bloodshed of the Wars of the Roses and caused me no offense. With a map of the battles of the Wars of the Roses and a family tree tracing the lines from Edward III to those involved in the troubles, this marks the Dynasty element of the display.

A example of the display in front of the throne

To the left of this room is an exhibition of the fabulous work of artist Graham Turner, whose medieval paintings are stunning. There is a fine array of his work here and it is a display not to be missed.

From the other side of the entrance display, the Visitor Centre walks us through the events of 1483 and Richard’s ascent to the throne. We are presented with the facts and offered opposing conclusions that can be drawn from these. Was Richard out for the crown from the beginning? Or was he reacting to events that happened around him? Whilst the displays may point out that most historians believe Richard was driving the events of that Spring and Summer (which, let’s face it, they do), it proffers the opposing view for the visitor to make up their own mind.

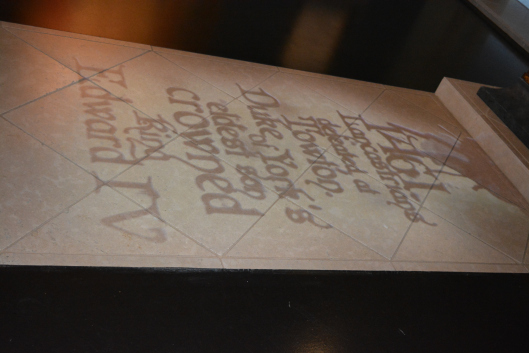

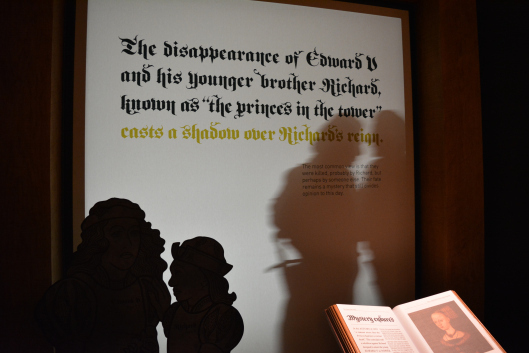

As you would expect from an exhibition that has seen input from the Richard III Society amongst others, the facts offered are just that – facts. I couldn’t fault any of them and there was no malevolent undercurrent dragging the viewer’s opinion of Richard down. A fine example of this is the display relating to the disappearance of Edward IV’s sons, the Princes in the Tower, which goes no further than noting that their uncertain fate cast a shadow over Richard’s reign. There can be no doubt that it did, and still does, but the exhibition does not lead the visitor to a pre-determined solution to the mystery.

The Princes in the Tower

I gave a talk in a local village recently on the life of Richard III, and told those listening that I couldn’t provide them answers to most of the questions that I would ask. It isn’t an easy approach to take because it sets the message up to be unsatisfying, creating more questions than it answers. The easy thing for the Visitor Centre to do might have been to perpetuate the shadowy myths many believe they know. They have not taken this easy route and I applaud them for taking the risk inherent in not providing definitive answers and presenting the controversy as just that.

As we moved through Buckingham’s Rebellion and displays detailing the influence on events of France, Brittany and Henry Tudor’s rise, and with Bosworth looming, I was struck by the incredible design work done within the displays. Each is crisp, clear and well presented. The information is accessible and the presentation clever. I even raised a smile at the Stanley ‘Swing-o-Meter’, and it’s not very often that that name paints my face happy!

The Stanley Swing-o-Meter

The display unashamedly informs us that the precise events at Bosworth are not clearly known, but that a view of the battle can be assembled from the fragments that have come down to us. Richard’s cavalry charge is dealt with as either a planned gambit, or an opportunistic reaction to the course of the battle, but a miscalculation either way. Is there much there to disagree with? The installation of pole-arms gives pause for thought. It is stark and brutal, just as Richard’s end was.

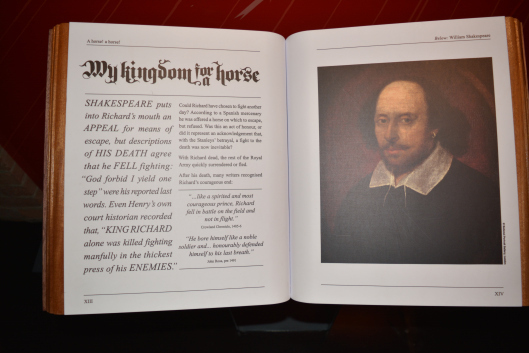

My one and only criticism of the exhibition comes here. It is a missed opportunity, an unfortunate perpetuation of a long-standing myth and a pet peeve of mine. We are told that ‘Shakespeare puts into Richard’s mouth an APPEAL for means of escape’ (display’s emphasis). No he doesn’t. The ‘A horse! a horse! my kingdom for a horse!’ quote is almost always taken out of context as a display of cowardice. In the context of the whole speech, it’s meaning is perfectly clear:

KING RICHARD III: A horse! a horse! my kingdom for a horse!

CATESBY: Withdraw, my lord; I’ll help you to a horse.

KING RICHARD III: Slave, I have set my life upon a cast, And I will stand the hazard of the die: I think there be six Richmonds in the field; Five have I slain to-day instead of him. A horse! a horse! my kingdom for a horse!

Richard calls for a horse. Catesby thinks that he means to flee, or at least encourages him to do so. Richard responds vehemently that he has cast the die of fate and will face the consequences. He has no intention of fleeing. He tells Catesby that there must be six Henry Tudors on the battlefield, because he has killed five men who he had mistaken for his enemy. He calls once more for a fresh horse, but he wants it to return him to the fray, to allow him to continue hunting Tudor, not to flee. Even Shakespeare, like every other writer on Richard’s end at Bosworth, concedes Richard’s bravery amongst the plethora of faults he imbues his character with. Even Shakespeare cannot deny him this. It would have been nice to have seen this misconception challenged rather than reinforced.

Shakespeare’s Richard III

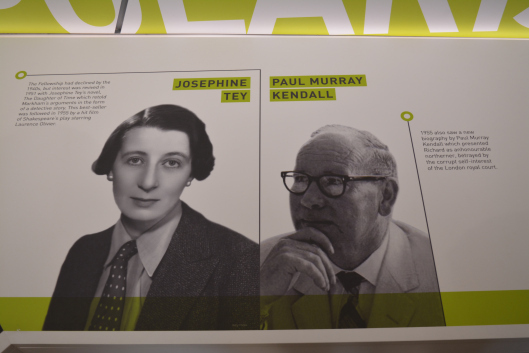

From here, the exhibition moves upstairs and it is a clear demarcation between the Death and the Discovery elements of the exhibition. The downstairs area has a thoroughly medieval feel that fits perfectly with its story. Upstairs is bright and crisp, telling the story first of Shakespeare’s version of Richard III and theatrical depictions through the ages. Revisionists such as Josephine Tey and Paul Murray Kendall get a look in at this point to, presenting both sides of Richard’s reputation through the centuries with equal weight.

Richard’s Revisionists

The connection between Shakespeare and Richard III is something many wish to disentangle as the main source of a conceived and incorrect image of Richard. I don’t think that this is necessarily required. It is the way in which many will first come into contact with Richard III and a proportion will go no further. Ricardians can harness Shakespeare to increase exposure to the truth. I have never viewed Shakespeare’s Richard III as anything but a masterpiece and I will never alter that opinion. But it is fiction. And the exhibition does a very good job of pointing that out to the visitor. For example, the story, we are told, draws upon an ancient notion of the evil uncle. It is clearly presented as fiction and I have to applaud this.

The story then moves through to the Discovery section, with details of the Looking for Richard Project’s initiation of the work, continuing through the University of Leicester’s involvement in the dig. I didn’t feel that the contributions of the Looking for Richard Project were belittled or sidelined. We listened to interviews with Philippa Langley and, although they didn’t occupy as much space as the details of the dig itself, which focussed on the University, their contribution was well presented.

Then there is the now infamous ‘Stormtrooper’ white suit of armour. It is, indeed, very white. Numbered blue stickers relate to a key beside the suit that names each of the pieces of armour that Richard would have worn. I didn’t feel that it created the impression that this was Richard’s actual armour, nor that his armour was bright white. Perhaps it might allow that misinterpretation I suppose. Museum curators have pointed out that such techniques are accepted and not uncommon teaching methods which, if anything, prevent the impression that this is an original suit of armour worn by Richard. That kind of suggests that the display couldn’t win either way. It’s either a Stormtrooper or creates a false impression of having Richard’s actual armour. Which is the lesser of those two evils? A decision had to be made. I didn’t find it ridiculous, though it didn’t quite seem natural either. Maybe it wasn’t meant to. It would certainly have been out of place downstairs, but fits in upstairs.

The Armour

We also saw the 3D print out of Richard’s spine and then the 3D recreation of the full skeleton with details of the wounds found on the remains. The marks detailed and clearly visible were powerful reminders of a savage death in a time we barely understand now. It was not only Richard that suffered this fate. Many others did at Bosworth, and many thousands had over the previous decades of civil war, countless further suffering similar fates in France. Neither was Richard the last to suffer in such a way, but it is a very personal and poignant moment to see what was done to a named individual, especially one who I have studied and tried to understand for so long.

The 3D Spine

3D Skeleton

Moving back downstairs, the final part of the exhibition leads to a quiet room with a glass section of flooring which overlooks the still-exposed site of the grave in which Richard III was found. Across the back wall is carved a verse from a prayer that can be found in his personal Book of Hours, a common prayer in his day, asking for God’s help in time of trouble, and offering him thanks for the gifts that He grants. I thought that this room was beautifully done. I don’t know quite what I expected, but I was thoroughly impressed.

Prayer from Richard’s Book of Hours

I was fortunate enough to visit the dig site during one of the open days, though we couldn’t see this site at the time. At intervals, a projection of the skeleton identifies the exact spot that the remains were found and how they were laid out. Although I think I see the need for this, I am glad that it isn’t on all of the time. The vacant space was enough for me. Looking into it, surrounded by buildings of so many eras, it reminds me how close the grave site must have come to complete destruction and eternal loss plenty of times.

The discovery of Richard III’s remains is an opportunity that was realised against all odds by a dedicated team at the Looking for Richard Project. I have nothing but respect and gratitude for their work. The University deserve a good deal of credit to for their technical expertise and experience in carrying out the dig. What has followed has often been unseemly and, in my opinion, unnecessary. I thoroughly understand that many deem it more than necessary and I do not seek to diminish their conviction nor challenge their right to it. If we seek to present Richard III as a more tolerant figure than history has passed to us, shouldn’t we also be more tolerant of differing views amongst ourselves?

I recently wrote to The Leicester Mercury and they were kind enough to publish my letter on their website. My call was to stop trying to portray Richard at either pole of the ‘goodie’ and ‘baddie’ scale but to seek out and try to understand the real man. The discovery of his remains has been far more divisive than I wish it had been. I think, if I’m honest, I was dreading the Visitor Centre pouring fuel onto the fire, kindling the destructive flames and peddling unreasonable, traditional nonsense in a sensationalist bid to cash in on the discovery.

I was very, very pleasantly surprised.

Okay, an ardent Ricardian may not learn anything new about Richard’s story, but for me, this should be aimed squarely at challenging what those who are less interested believe they know about Richard III.

The Visitor Centre achieves this.

By presenting the options without defining the conclusion the visitor should reach.

By using stunning graphics in a well defined and delineated space.

By pitching a message at exactly the right level.

By rounding it all off with a stunning, peaceful place to contemplate all that you have seen whilst reminding you that this is a very human story.

The story of a man.

I would thoroughly recommend going to see the exhibitions at the King Richard III Visitor Centre. An informative experience if you know little of the truth about Richard III.

A poignant space if your interest runs deeper.

Whatever you fear – misinformation, a lack of respect – lay those fears to rest. Richard III is done justice in that space. At least, I believe he is. Why not visit and see what you think?

Perhaps it is time for an end to York v Leicester, and a time for united Ricardians v the lies.

I’d love to hear your thoughts and experiences of the Centre.

I have written more about Shakespeare’s Richard III at mattlewisauthor.wordpress.com/2013/06/02/william-shakespeares-richard-iii-the-convenient-villain and at royalcentral.co.uk/blogs/history/the-defence-of-king-richard-iii-part-4-bosworth-shakespeare-that-horse-14699.

The letter on The Leicester Mercury website can be found at www.leicestermercury.co.uk/Richard-III-Stop-looking-saint-demon-try-man/story-24519152-detail/story.html

Matthew Lewis is the author of a brief biography of Richard III, A Glimpse of King Richard III along with a brief overview of the Wars of the Roses, A Glimpse of the Wars of the Roses.

Matt’s has two novels available too; Loyalty, the story of King Richard III’s life, and Honour, which follows Francis, Lord Lovell in the aftermath of Bosworth.

The Richard III Podcast and the Wars of the Roses Podcast can be subscribed to via iTunes or on YouTube

Matt can also be found on Twitter @mattlewisauthor.

October 12, 2014

The Fate of the House of York

Pinpointing the beginning and end of the Wars of the Roses has always been problematical. One thing is certain. On 22nd August 1485, the House of York lost its grip on power, but it was far from destroyed, and the infant Tudor regime was not as secure as it was to lead the world to believe. York persisted; and Henry VII was to find himself haunted and in need of a new kind of solution.

As early as Easter 1486 a Yorkist uprising threatened Henry’s fragile grip on power. Francis, Viscount Lovell, erstwhile friend of King Richard III, and the Stafford Brothers, Sir Humphrey and Thomas, tried to kindle revolt. Lovell attempted to raise the north as Henry approached on his progress and the Staffords cultivated support from their power base in the south of the Midlands.

The Stafford brothers managed to enter, seize and hold Worcester, but the north stuttered in the king’s presence and Lovell was forced to flee. As Henry stormed southward, the Staffords fled Worcester to sanctuary in Culham, from which Henry had them dragged forcibly by Sir John Savage. This incident led to Henry procuring the Pope’s approval for the removal of the right of sanctuary in treason cases. Sir Humphrey was hanged, Thomas was bound to good behaviour and Lovell fled to the court of Margaret, Dowager Duchess of Burgundy, sister of Edward IV and Richard III who was to become a magnet for Yorkist hopes.

What had been missing from this early attempted revolt was a figurehead. The rebellion was nominally in favour of Edward, Earl of Warwick, the young son of George, Duke of Clarence, nephew of Edward IV and Richard III. Warwick, though, was under Henry’s control in the Tower of London and this lack of a figurehead was to prove a death blow to the revolt.

The following year, an attempt was made to correct this flaw. Lord Lovell landed at Furness with a large force of professional Swiss mercenaries, paid for by Margaret of Burgundy, an army of Irish kerns supplied by the Earl of Kildare, reflecting lingering Yorkist affection in the Pale of Ireland that was to buck Tudor rule for many years, and two Yorkist figureheads.

John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln was the eldest nephew of Edward IV and Richard III, son of their sister Elizabeth, Duchess of Suffolk. John was approaching his mid twenties and had been working in the Council of the North under his uncle Richard. He may have been named Richard’s heir following the death of the Prince of Wales and was the senior male Yorkist in terms of age.

A portrait, believed to be of Richard de la Pole

The second figure was Edward, Earl of Warwick. The twelve year old senior male-line Yorkist heir who was safely tucked up in the Tower of London. This boy had been crowned King Edward VI in a lavish ceremony in Dublin before the invading army left Ireland. This rebellion not only had a figurehead, but noble support and even a spare.

The invaders were met on their landing by a handful of loyal Yorkist gentry and they headed for safe ground, marching toward York to recruit more support, but the sight of the bare chested, bare legged Irish kerns disconcerted the authorities of York, who closed their gates to the rebels. Turning south, the large army was forced to seek a confrontation with Henry without further help.

The king, no doubt slightly bemused by the appearance of the boy he thought he had locked up safely, paraded Edward, Earl of Warwick through London before mustering an army to meet the rebels at the Battle of Stoke Field on 16th June 1487. Henry’s army was around 12,000 strong and led by the Earl of Oxford, who had led Henry’s own invading army at Bosworth. Lincoln had around 8,000 men. King Henry remained at the rear of the battle with his uncle Jasper keeping an escape route open for him. He was not to need it.

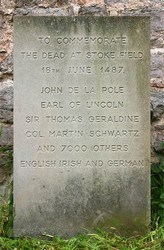

The battle was close for some time, with some of Oxford’s men fleeing the field, until the tide turned. Around half the Yorkist army was slain, with the Irish warriors taking the brunt of the losses, though the Swiss mercenary leader Colonel Martin Schwartz was amongst the casualties and appears on the memorial that marks the location of the battle. Lincoln was also killed during the fighting. Lord Lovell was injured and last spied crossing the Trent as he fled. He was never seen nor heard of again and vanishes from the historical record. In spite of a wealth of speculation, a safe passage through Scotland, which may or may not have been collected, and a mysterious story of a skeleton bricked up at the Lovell manor of Minster Lovell, his fate is unknown.

Monument at the site of the Battle of Stoke Field

The boy was captured and Henry ‘discovered’ that he was, in fact, an Oxfordshire boy named Lambert Simnell. Holding him up as an innocent pawn of the bitter Yorkists, Henry pardoned the boy, famously putting him to work in the royal kitchens as a spit boy. Lambert was last heard of as a royal falconer to Henry VIII in the mid 1520’s. His true identity remains a matter of doubt and discussion to this day. Dr John Ashdown-Hill’s next book may prove very interesting as he examines Lambert’s story more closely.

Small plots were continually uncovered by Henry VII’s busy network of spies. Men like Abbot Sant, Edward Franke and Thomas Rothwell are forgotten, but kept the fires of Yorkist hope alive, and kept Henry VII dancing on hot coals. The Yorkist threat seemed at least quietened, if not yet quite destroyed. John de la Pole had four remaining brothers, though one was in holy orders and was never to impact upon the political scene. John’s younger brother inherited the Dukedom of Suffolk on their father’s death in 1491, though in 1493 Henry VII downgraded the title to that of an Earl; something of a slap in the face to a family no longer posing a present threat but perhaps a hint that all was not as rosy as the Tudor iconography would like us to believe.

The mid-1490’s saw the next serious threat to Henry from a Yorkist cause that refused to die. A new Pretender emerged on the Continent, perhaps under the tutelage of Margaret of Burgundy. Known to history as Perkin Warbeck, he presented himself to the courts of Europe as Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, younger son of Edward IV and one of the infamous Princes in the Tower. Much has been written elsewhere about Warbeck and I shall not delve too deeply into that part of the story here.

Suffice it to say that Perkin gained a great deal of support, which perhaps had less to do with his true identity than with European leaders’ desire to destabilise the English king. By now, most of them owed Henry huge sums of money so had a financial interest in seeing him squirm a little. It is in the face of this threat that Henry VII took a radical step, the context of which is often overlooked.

Now, aged three and a half, Henry’s second son and namesake was propelled from the obscurity of his mother’s household onto the fraught playing field of politics. On All Saints Day 1494, as Warbeck proved an increasing nuisance and men of Cornwall marched on London, Henry was elaborately, conspicuously and pointedly created Duke of York at Westminster, being made a Knight of the Bath at the same time. This was a clear antidote to Warbeck’s assertion to entitlement to the support of the House of York. In an ancient echo of Tony Blair’s tactics twenty years ago, to prove that there is nothing new under the sun, Henry set about sculpting a New House of York to eclipse the memory of the Old. I’ve tried to arrive at a clever parallel between Tony Blair and Gordon Brown and the Tudor father and son, but kept hearing the Steptoe and Son theme tune in my head instead, so I gave up on that idea.

It also served to remind those clinging to hope that the cause of the Princes, Edward V and the old Duke of York, was dead, politically certainly, though it carried with it the connotation of physical demise too. Furthermore, it marked York, as it still does today, as very clearly second string, a subservient house.

Henry even looked like his grandfather. He was his mother’s son, the embodiment of the House of York. The old look with a new feel. Perhaps this physical similarity was the father of the idea.

If we look at those who surrounded Henry as Duke of York it is clear what his father was trying to do. If we leap ahead to look at those who joined Henry in the lists of a tournament shortly after his coronation, as mentioned in a previous blog, as a young king, it was an advertisement and affirmation of his Yorkist credentials. The effect is clear to see. Charles Brandon, one of Henry’s closest friends, later his brother-in-law and Duke of Suffolk, was the son of Sir William Brandon, who had died at Bosworth whilst carrying Henry Tudor’s standard. Sir William had been Edward IV’s Master of the Horse. He had abandoned the House of York under Richard III, under something of a criminal cloud according to the Paston Letters, but his Yorkist credentials were impeccable. The Howard family were mainstays of Henry’s rule but were old Yorkists. John Howard had died at Bosworth fighting for Richard III. His son, Thomas, who was to become second Duke, had fought at Bosworth for Richard but survived. Now, he was suddenly of use and was placed with the young Duke of York. Henry Bourchier, 2nd Earl of Essex was descended from Edward III but was also a nephew of Elizabeth Woodville. William Courtenay, Earl of Devon was married to Catherine of York, sixth daughter of Edward IV, and Arthur Plantagenet was an illegitimate son of Edward IV who was to become very close to his nephew, Henry VIII.

This was Henry VII’s clear step onto the front foot in response to the emergence of a serious threat from the House of York. He simply created a new one. Anyone deemed safe enough was placed around the new Duke to add an air of credibility to the new establishment. A side effect of this was that later betrayals by the House of York were to be viewed by Henry VIII as personal attacks and betrayals, which perhaps exaggerated and magnified his response to those threats.

Warbeck turned out to be a prolonged threat. He wasn’t captured until 1497, when he ‘confessed’ to being an imposter. In 1499, Warbeck was almost certainly used by Henry VII to entrap Edward, Earl of Warwick, now 24. The two were caught plotting to escape the Tower and executed. Warwick was the last of the legitimate male line of York and his removal was a requirement of Catherine of Aragon’s marriage to Arthur, something she was later to believe had cursed her. Judicial murder struck off two thorns with one axe.

Henry VII, having secured the marriage of his heir Arthur to Catherine, now resurrected another Yorkist tradition. It is striking the extent to which he reached back in his attempts to move forward. Just as Edward IV had sent his son to Ludlow to preside over a court of his own as Prince of Wales, so Arthur was despatched to demonstrate the new regime’s solid link to the past. The Tudors were new, but rooted in an old stability. Tony Blair was turning 500 year old tricks in the 1990’s.

Still, though, the petals of the Tudor rose were not without pests. Just before Arthur and Catherine’s wedding, Edmund and Richard de la Pole, younger brothers of John, fled to the court of Maximilian, the Holy Roman Emperor. Earlier, Sir Robert Curzon had told Maximilian that England was fed up with Henry’s “murders and tyrannies”, proposing Edmund as a rival claimant. Maximilian responded that he would do all that he could to see “one of Edward’s blood” returned to the throne. Doubtless this encouragement reached Edmund and Richard and directed their flight.

The brother they left behind, Sir William de la Pole, was arrested and imprisoned in the Tower of London in spite of his failure to join his brothers. For allowing Edmund to pass through Calais, Sir James Tyrell was ordered to submit to arrest. Calais was besieged when he refused until a promise of safe passage to an audience with the king caused him and his son to emerge, only for that assurance to evaporate as they were roughly taken into custody. Tyrell was tortured in the Tower for news on Edmund, though there is no record that he was ever even asked about the fate of the Princes in the Tower, nor that he confessed to arranging their murder.

Edmund began to call himself The White Rose, Duke of Suffolk and openly proclaimed his right to the throne. He found support from King John of Denmark, Norway and Sweden. The Chronicle of the Grey Friars records that on 22nd February 1502 “was Sir Edmund de la Pole pronounced accursed at St Paul’s Cross, at the sermon before noon”.

Things got worse for the new dynasty. On 2nd April 1502 Prince Arthur died. It is possible that the panic this fostered drove the trials on 2nd May 1502 of Sir James Tyrell, Sir John Wyndham and others. Tyrell and Wyndham were beheaded on Tower Hill, with several others hung drawn and quartered at Tyburn for their support of the de la Poles. It is also feasible that this same panic caused Henry to suggest to an ambassador that he was considering claiming Tyrell had confessed to the murder of the Princes. The ambassador apparently advised strongly against it and the matter was taken no further, but it is telling that at a time of crisis for the House of Tudor, it was the House of York that was perceived as the very real threat. The Princes again became an issue. Henry again avoided publically stating that they were dead. This remains odd to me, but is another story altogether.

In 1504, the threat Henry felt from The White Rose was again in evidence. He signed a trade treaty with the Hanseatic League so detrimental to English merchants that the only reason he could possibly have agreed was the provision that they offer no support or refuge to Edmund de la Pole. Edmund, though, was finding Maximilian’s means did not match his promises and support and money were beginning to dry up.

Also in 1504, John Flamank reported to the king a discussion that had taken place in Calais amongst several of the leading figures of the town. They reportedly spoke of what would happen after Henry’s death, Flamank reporting that they said “the king’s grace is but a weak man and sickly, not likely to be long lived … Some of them spoke of my lord of Buckingham, saying that he was a noble man and would be a royal ruler. Others there were that spoke, he said, likewise of your traitor, Edmund de la Pole, but none of them, he said, spoke of my lord prince.” The “my lord prince” in question was Henry VIII, and his father was surely disturbed that he was overlooked at a discussion of the succession. It did not bode well for Tudor security.

Matters took a turn in Henry’s favour in January 1506 by sheer luck. Maximilian’s son, Archduke Philip, ruler of Burgundy, heir to the Hapsburg empire and the Holy Roman Emperor title was shipwrecked on England’s south coast by a storm en route to see his wife, the heiress to the Spanish throne. This was a prize catch for which Henry had an important use in mind. Virgil wrote that Henry was “scarcely able to believe his luck when he realized that divine providence had given him the means of getting his hands on Edmund de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, who had been the leader of the conspiracy against him a few years previously”.

Philip was forced to sign a treaty resolving the current trade disputes in England’s favour, but was also required to give up Edmund de la Pole, and Henry made it clear that Philip would not leave England until Edmund was in the king’s custody. Edmund was collected from Mechlen and delivered to Calais, apparently on the promise that he would not be harmed, but that he would be fully pardoned and restored to his lands. Edmund, though, was bundled off to the Tower.

Henry VII died on 21st April 1509. For Henry VIII’s coronation, John Skelton wrote “The Rose both White and Red \ In one Rose now doth grow”. Edward Hall called the new king the “flower and very heir of both said lineages”. But the White Rose had not yet been properly reconciled. On 30th April 1509, to celebrate his coronation, Henry issued a general pardon that had been provided for in his father’s will, which excluded just 80 people. Top of the list was Edmund de la Pole, followed by his brothers Richard, who was still at large on the continent, and William, still languishing in the Tower.

In 1513, as Henry prepared to invade France, Louis XII offered Richard de la Pole support. Fearing the resurgence of the White Rose threat, Henry took advantage of Edmund’s outstanding attainder to have him quietly executed on Tower Green on 4th May 1513, just before leaving for France and in spite of his father’s promise the Edmund would not be harmed.

Henry VIII identified himself strongly with Henry V, in tapestry, in art and in his continental ambition. Almost a hundred years after the Agincourt campaign, Henry was trying to emulate the great warrior king. As Henry V prepared to leave in 1415, he was faced with a threat of rebellion known as The Southampton Plot. Richard of Conisburgh, Earl of Cambridge, the grandfather of Edward IV and Richard III, was a ringleader and was executed just before Henry V set sail. Perhaps Henry VIII sought to replicate the Agincourt campaign no precisely that he believed he required a Yorkist sacrifice to ensure success. Or maybe it simply marks the level of the threat of the White Rose that persisted.

But Henry VIII had left a lose end that Henry V had not. A White Rose in exile.

Richard de la Pole now styled himself The White Rose and Duke of Suffolk. Louis recognised him as King of England. In his mid-30’s, Richard was a natural soldier and was proving his military worth to Louis in Italy in an attempt to win further aid. In 1514, Louis provided Richard with vast sums of money and a huge army. John, Duke of Albany, Regent of Scotland agreed to take Richard to Scotland to launch his invasion. All was set. Just as Richard was about to sail, Louis signed a peace treaty with Henry and the attack was called off.

When Louis died in 1515, Richard’s close friend the Dauphin became Francis I. Henry seems to be have been genuinely concerned. He set Thomas Wolsey to oversee Sir Edward Poynings and the Lord Chamberlain, the Earl of Worcester, tasking them with arranging the assassination of Richard de la Pole. That men of such standing were appointed to this task is a mark of the threat that Henry perceived.

Percheval de Matte, Captain Symonde Francoyse and Robert Latimer are all recorded as being hired to complete the task. All failed, and for a decade Richard evaded Henry’s agents, moving frequently and attracting Yorkist stragglers to his court in exile.

On 25 February 1525, Richard commanded the right wing of Francis’s French army at the Battle of Pavia in Italy. The French army was crushed by that of the Holy Roman Emperor. Francis was captured and Richard was killed. When news reached Henry, bonfires blazed throughout London and a Te Deum was celebrated at St Paul’s. It’s hard to know whether Henry was more excited that Francis was a prisoner and his kingdom exposed or that Richard de la Pole, The White Rose, was dead.

The final chapter of the de la Pole threat closed in 1538. Sir William de la Pole died, still a prisoner in the Tower. His 37 year incarceration remains the longest stay in the Tower’s history.

Another branch of the still broad Yorkist family proved to be the most persistent thorn in the Tudor side. Edward, Earl of Warwick had a sister, Margaret. Shortly after Henry VII came to power she was married to a cousin of the new king, Sir Richard Pole, to neutralise her as a focus for disaffection. Sir Richard died before Henry VII did, but Henry VIII, perhaps encouraged by a guilty Catherine of Aragorn, restored Margaret to power shortly after his coronation. She was created Countess of Salisbury, one of her parents’ titles, in her own right, became a lady in waiting to Catherine and an outspoken supporter of Princess Mary. Margaret had four sons, who were men by the time Richard de la Pole was killed at Pavia in 1525. One of her daughters, Ursula, was married to the son of the Duke of Buckingham, whose fall in 1521 had cast a shadow of suspicion over the Poles.

Reginald Pole was Margaret’s second son, born in 1500 at Stourton Castle near Stourbridge. From an early age he was drawn to the church and Henry VIII contributed toward the cost of the young man’s education, perhaps happy to see some White Rose blood soak away into the clergy. When Reginald was 21, Henry encouraged and subsidised his six year period of study at Padua in Italy, where he met and befriended Erasmus. After his return to England in 1527, appointments and patronage denoted great royal favour.

After the death of Cardinal Wolsey in 1529, Reginald was offered the Archbishopric of York, but refused it. In a private audience with Henry, he argued eloquently and firmly against the divorce from Catherine of Aragon, causing Henry to storm out, slamming the door behind him. In 1532, Reginald left England, a decision that perhaps saved him from the fate of More and other critics of the King’s Great Matter. In 1535, he was again in Padua, where he received a letter from Henry asking for his opinion on the divorce again, clearly hoping that Reginald’s growing influence in Rome could serve the English king. There is a fascinating series of exchanges recorded in the state papers, with Henry eagerly nudging Reginald for his response and Pole asking Henry to bear with him just a little longer. It is uncertain whether Reginald had not yet finished writing, wrestling with his conscience or plucking up courage.

It took Reginald a year to reply. That was because he sent back not a letter, but a book. Known as De Unitate – A Defence of the Church’s Unity, it was written for Henry’s eyes only and was very definitely not what he had been hoping for. De Unitate tore apart Henry’s argument for the divorce, but then continued on to condemn a quarter of a century of poor rule and wasteful policies. Lord Montague, Reginald’s oldest brother, wrote to him slamming the danger he had placed the rest of the family in and Margaret wrote to her son of “a terrible message” that Henry had sent her.

In 1537 Reginald was created a Cardinal so that he could visit England as a Papal Legate. Significantly, he was never ordained as a priest because Papist plots began to revolve around marrying Reginald to Princess Mary to unite the White Rose and the Tudor Rose and restore England to Roman Catholicism. Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, apparently did not view Reginald as a valid candidate for the throne of England, referring to him as “El Ingles que esta en Venicia,” “the Englishman who stays in Venice”. Charles had his own idea of marrying Princess Mary to Don Luis, the infante of Portugal, and placing him on Henry’s throne.

Pope Paul III, though, had identified Pole as the man to achieve his end. He was given 10,000 ducats to recruit men in Flanders and Germany with the aim of kindling revolt in England. Under the guise of a peaceful visit as Papal Legate, Pole was to spark rebellion, marry Princess Mary and take Henry’s throne. Bergenroth wrote that “The “soldier of the true faith,” the pretender to the hand of the Princess Mary, and the candidate for the English crown was therefore made a cardinal in appearance, the Pope taking care that he should not enter even the lowest degree of holy orders, and content himself with having the tonsure shaved on his head.”

Cardinal Reginald Pole

In France, Francis I was only put off from supporting Pole by his own desire to snatch a chuck of England for himself.

One thing is perfectly clear. By the mid 1530’s, England was viewed as fair game. The throne was up for grabs. The only question was who would succeed in the smash and grab of Henry VIII’s failing kingdom.

Reginald did not get to England and by the end of 1537, Henry was advertising a reward of 100,000 gold crowns to anyone who brought Reginald to him, dead or alive.

During the following year, the White Rose faction in England appeared to throw caution to the wind. Henry Courtenay, the Marquess of Exeter, a grandson of Edward IV was only outdone in his criticism of the newly emerging England by Henry Pole, Lord Montague, who said that “the King and his whole issue stand accursed”. On 29th August 1538 Geoffrey Pole, Margaret’s third son, was suddenly arrested. He was, by turns, interrogated, threatened with the rack and offered a pardon to provide the “right” answers. After his first interrogation, Geoffrey tried to commit suicide in his cell in the Tower by stabbing himself with a knife, but failed to do enough damage.

On 4th November Exeter and Montague were arrested. Montague was tried on 2nd December and Exeter on 3rd. Both pleaded not guilty, but both surely knew that it would make no difference. When found guilty and condemned to death, Montague told the court “I have lived in prison these last six years”.

Montague, Exeter and Sir Edward Neville were beheaded on Tower Green. Two priest and a sailor who had been accused of carrying messages to Reginald, were amongst others hung drawn and quartered at Tyburn on the same day for their part in the affair. On 28th December, Geoffrey again attempted suicide, only to fail once more. Released the following year, he fled to Flanders, no doubt haunted by his experiences and the guilt of delivering his brother to the executioner’s block. The Exeter Conspiracy was almost certainly a figment of Henry VIII’s paranoiac fear but the king reacted savagely and it demonstrated the consuming fear he still had of the White Rose faction.

In February 1539, Henry wrote to Charles V that he had only narrowly escaped a plot to murder him, his son and his daughters and to place Exeter on the throne. At around the same time, Reginald arrived in Toledo for an audience with Charles to ask his backing for a Papal plot to invade England. Charles tactfully declined to help. A few months later, Countess Margaret was included in an attainder passed against those involved in the Pilgrimage of Grace and the Exeter Conspiracy.

In the autumn of 1539, there was a further shock when Countess Margaret, aged 65, was suddenly arrested and taken to the Tower without even a change of clothing. Her grandson, Montague’s son Henry, was also incarcerated there at the time. She remained in the Tower until 1541. In an echo of 1415 and of 1513, Henry had crushed a rebellion in the north and was planning to visit James V of Scotland. Before leaving, he had several prisoners executed, adding, apparently at the last minute, Countess Margaret Pole to the list. She was awoken early in the morning on 27th May and told that she would be executed at 7am. Bemused, she walked to the block and knelt. The inexperienced executioner slammed the axe into her shoulder, taking half a dozen more blows to complete his task. If anyone is unclear precisely why Henry VIII’s procurement of the skilled French executioner who dispatched Anne Boleyn was considered a mercy, it was because this was the likely and not infrequent alternative. The 67 year old Countess later became a Catholic saint for her martyrdom and these words were found carved into the wall of her cell:

For traitors on the block should die;

I am no traitor, no, not I!

My faithfulness stands fast and so,

Towards the block I shall not go!

Nor Make one step, as you shall see;

Christ in Thy Mercy, save Thou me!

Henry VIII died on 28th January 1547. His son, Edward VI died on 6th July 1553 aged just 15. In November 1554, with Queen Mary installed, Reginald Pole returned to England as Papal Legate, becoming Mary’s Archbishop of Canterbury with the Catholic restoration.

On 17th November 1558, Reginald died, aged 58, on the very same day as Queen Mary, so did not live to see Elizabeth return Protestantism to England, but the White Rose threat outlasted Henry VII, Henry VIII, Edward VI and Mary I. The influence of the threat, real or imagined, is perhaps as easy to overstate as it is to understate. One strand of the House of York survived quietly until today, leading from a daughter of Edward IV to Michael Ibsen, never having rocked the boat. It is certain, though, that the House of York’s threat to the throne, which perhaps saw its birth in Ludlow in 1459, did not end at Bosworth, nor even at Stoke Field. It ended quietly, in a bed, nearly 75 years after the Tudor dawn. The neat 30 year Wars of the Roses was a Tudor construct to draw a veil over generations of failure to rid themselves of shadows cast by the House of York. Henry VIII created England as a European super power by sleight of hand. The Tudor’s security was similarly a sleight of hand, a grand trick played as much upon themselves as the nation to hide desperate fears that haunted them for three quarters of a century.

For lots more detail on these events, I recommend Desmond Seward’s The Last White Rose.

Matthew Lewis is the author of a brief biography of Richard III, A Glimpse of King Richard III along with a brief overview of the Wars of the Roses, A Glimpse of the Wars of the Roses.

Matt has two novels available too; Loyalty, the story of King Richard III’s life, and Honour, which follows Francis, Lord Lovell in the aftermath of Bosworth.

The Richard III Podcast and the Wars of the Roses Podcast can be subscribed to via iTunes or on YouTube

Matt can also be found on Twitter @mattlewisauthor.

August 23, 2014

Why Is It Called Buckingham’s Rebellion?

The first serious threat to Richard III’s kingship came in mid October 1483, just four months after his coronation. It is hard now to properly judge the popular reaction to the new king and his seizure of power, but the fact that such a real threat came so swiftly points to some disaffection even during the honeymoon period. As Richard was progressing around his new kingdom refusing gifts of money and contenting “the people wher he goys best that ever did prince”, as Thomas Langton, Bishop of St David’s enthused, others were clearly less upbeat about the new king.

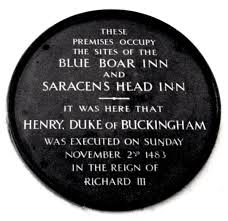

When rebellion came, it was famously to involve Richard’s closest and most powerful ally of the last few months, Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham. The Duke was to give his name to the uprising, but was this simply an early sleight of hand trick by … well, more on that anon.

Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham

Although Buckingham’s Rebellion would fail it is important to understand just how large and well organised a threat it really was and how fortunate Richard was when it finally broke. It is the nature of regimes, especially new ones seeking to put down roots, that rebellion should be understated, but we should not let that blind us to the size and complexity of what was planned.

The rebellion was to take place on 18th October, St Luke’s Day. It is likely people took less notice of the calendar date than feast days in mediaeval times and it is telling that huge royal events always coincided with feast days. So word would have spread that the Feast of St Luke was the day. Kent was set to rise and attack London from the south east, drawing Richard’s attention that way as men of the West Country, Wiltshire and Berkshire, swelled by Buckingham’s Welsh army crossing the Severn and Henry Tudor’s force of Breton mercenaries landing, probably, in Devon moved in from the west. With Richard’s attention on Kent, they would fall on him, catching him unawares, and bring down the might of their combined dissatisfaction upon him.

But how had Richard come to this so swiftly? In June his coronation had been a triumph. He had been well received all around the country, particularly in the north. Perhaps this is precisely where the problem began. Richard was something of an unknown quantity in London, and after the troubles that seemed barely behind them, few can have looked favourably on more uncertain times and more regime change, especially when this new arrival descended from the north and openly favoured the region. There will come a question of self-fulfilling prophecy to add to the cauldron of confusion.

The mystery of Buckingham’s turning of his coat is as fascinating as it is impossible to solve. He may have fallen out with Richard over the fate of Edward IV’s sons, though even this possibility is sub divided, since Buckingham may have been appalled by a plan outlined by Richard to do away with the boys, or Buckingham may have vehemently argued that it must be done only to be denied by Richard. Perhaps Buckingham saw some revenge against the Woodville clan he had been forced to marry into by killing two of its matriarch’s sons. The sources offer as much weight to a prevailing view that Buckingham had killed the boys as Richard had, and Buckingham had lingered in London for several days after Richard left on his progression. Simply, we have no answer to this, only possibilities that warrant examination.

We do know that Buckingham had long coveted the return of the vast Bohun inheritance, withheld from him by Edward IV. Richard was in the process of restoring this to Buckingham, awaiting only Parliamentary approval, but perhaps this was too slow for Buckingham’s liking and fed a niggling doubt that he would ever get it back.

There are two figures who probably do feature prominently in Buckingham’s defection, and possibly play a role that burrows much deeper into the foundations of Richard III’s rule. This inseparable and unstoppable duo are John Morton, Bishop of Ely and Margaret Stanley (nee Beaufort). I know that much is made of Margaret Beaufort’s involvement or lack thereof in, for example, the fate of the sons of Edward IV, but it remains too little examined for me. I have no doubt that many will take objection to what I offer, but I do not present it as fact, merely as a possible interpretation of what happened. I disagree with the view that Margaret Beaufort could not possibly have been involved in anything that went on as much as I do with the view that she definitely killed the boys.

Lady Margaret Beaufort

The Tudor antiquary Edward Hall wrote some 60 years later that Margaret Beaufort had chanced to meet Buckingham on the road near Bridgnorth as she travelled to Worcester and he returned to his lands in Wales. She supposedly pleaded with Buckingham to intercede with Richard on her behalf, to use his influence to secure the safe return of her son and his marriage to a daughter of Edward IV, an arrangement that had been close to fruition when Edward suddenly died. There is little of rebellion herein, except that, if this discussion ever took place, Margaret was making it clear to Buckingham that Richard was not one who seemed willing to deliver what had been hoped for under Edward, sowing seeds of doubt that Richard would deliver anything. Of little consequence to Buckingham, perhaps, but he was still hoping for those Bohun lands.

If a seed was sown, it was keenly tended by Bishop Morton when Buckingham reached Brecon Castle. The Bishop had been released from the Tower following the events surrounding Hastings’ execution into Buckingham’s care under a gentle form of house arrest. Morton was mentor to a young Sir Thomas More and it seems likely that More’s version of Richard stems from Morton, a man who seems to have hated Richard with a passion. An ardent Lancastrian, Morton had been reconciled to Edward IV’s rule after Tewkesbury and the death of the line of Lancaster. Buckingham’s family had been staunch Lancastrians too, his grandfather dying at the Battle of Northampton fighting to protect Henry VI. Morton apparently tugged at latent Lancastrian sympathy, perhaps even giving Buckingham hope of the throne for himself. The seed was fertilised and shooting. The Bishop must have been pleased with his work.

John Morton, Bishop of Ely

This is where many will disagree with my suggestion, but I think it is possible that more cultivating was going on in London at the same time. Margaret Beaufort wanted her son back. She seems to have decided that he would return best by seizing upon the discontent that bubbled around Richard to make himself king. I don’t subscribe to the view that she spent his entire life plotting to make him king, only that she desperately wanted him back and saw an opportunity to good to miss. An all or nothing gamble. But if she was going to gamble her precious only son, she would need to swing the odds as far in his favour as possible.

It is known that Margaret opened a channel of communication to Elizabeth Woodville in her sanctuary in Westminster Abbey. Unable to risk personal visits, Margaret’s physician, Dr Lewis Caerlon acted as a go between, serving Elizabeth as her physician too. By this medium a pact was reached. Elizabeth Woodville would call out her family’s support and, far more importantly, her late husband’s loyal followers, in support of Henry Tudor’s bid for the throne in return for an assurance that Henry would marry her daughter Elizabeth, making her queen if he were successful.