Matthew Lewis's Blog

October 23, 2021

Gone Medieval in The National Archives

This weekend’s episode of the Gone Medieval podcast from History Hit is a peek behind the scenes at The National Archives with Principal Medieval Records Specialist (might as well read kid in a sweet shop to me) Euan Roger. As well as talking us through the history and evolution of The National Archives, Euan talks about some of their treasures.

https://play.acast.com/s/gone-medieval

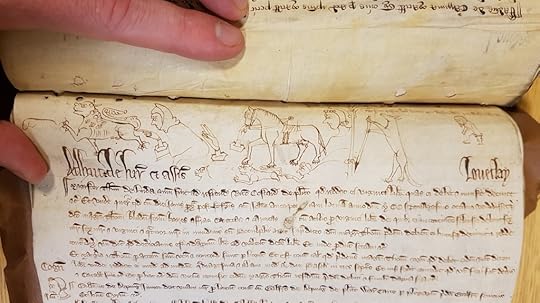

We also had a great chat about doodles Euan has come across in his studies. Here are a few photos of the ones we talked about.

This is Forster’s signature with a huge ‘F’. The man is, Euan suggested, Forster himself on a lads’ night out in London.

Horses are popular features in the doodles, as are hands and fingers – whatever they were up to!

Here’s another fancy horse jotted in a margin of government paperwork.

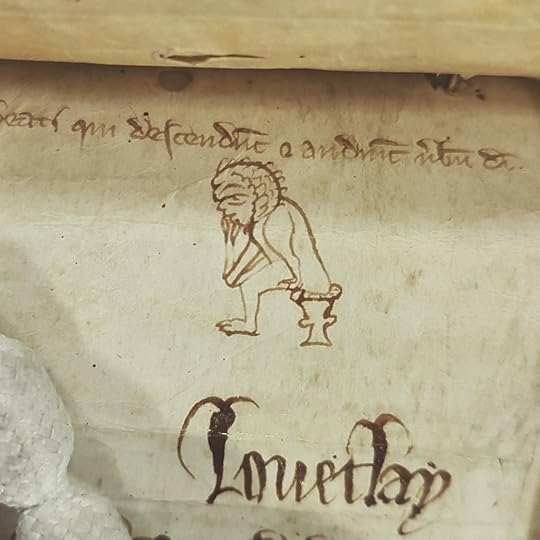

This man looks very pensive on the toilet. Penny for them?

Okay, this one is downright rude. This scribe clearly has the oldest jibe in the world for his boss!

I hope you’ll give the episode a listen, and if you enjoy it, please subscribe, and maybe even leave a review.

June 18, 2021

Richard III and the Fall of the Brandon Men – Guest Post by Sarah Bryson

The Brandon men, father Sir William Brandon and his three sons, William, Robert and Thomas, had been loyal servants to King Edward IV. The king died on 9th April 1483 and his successor was his twelve-year-old son, Edward. However, the new king’s Uncle, Richard of Gloucester had the boy and his younger brother, Richard of York, declared illegitimate due to a precontract his brother had with Lady Eleanor Butler. As the late king’s only legitimate heir, Richard was asked by Parliament to take the throne and he was crowned King on 26th June 1483.

With a new King on the throne, the loyalties of the Brandon men lasted less than a year.

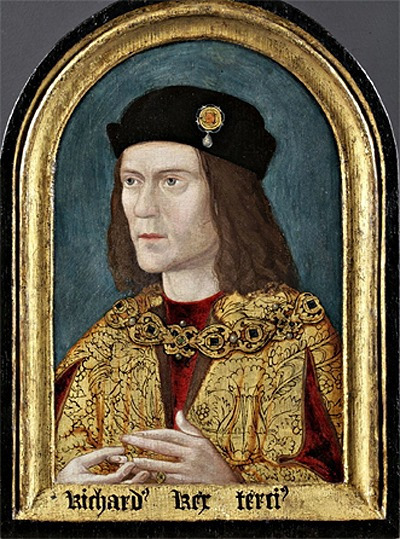

King Richard III

King Richard IIIDuring the summer of 1483 a rebellion was planned against Richard III. Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham had been convinced by Dr John Morton, Bishop of Ely, to switch his allegiance from Richard III to Henry Tudor, the Lancastrian claimant in exile. It should be noted that Dr Morton was an associate of Sir William Brandon and it is highly probable, with the following events, that Morton and Brandon spoke about Brandon’s participation and support in the rebellion. The Brandon men decided that the oldest son William, and his youngest brother Thomas, would join the Duke of Buckingham’s rebellion.

The rebellion was set to begin on the 18th of October however rebels in Kent rose early and began to march to London. In response Richard III sent John Howard, Duke of Norfolk to crush the rebels. It was planned that Buckingham and his men would meet up with supporters in the West. The weather was horrid and continual rain caused the rivers Severn and Wye to break their banks, flooding the surrounding lands making it near impossible for Buckingham to progress. With his soldiers beginning to retreat Buckingham knew the cause was lost and he fled. He was betrayed and quickly arrested, beheaded in the market place at Salisbury on the 2nd of November.

At the end of 1483 or early 1484 William and Thomas Brandon left England and headed to Brittany to join Henry Tudor. The actions of the Brandon sons clearly showed that they believed themselves to be in danger. However, on the 28thMarch 1484, a general pardon was granted to William Brandon II.

It is unknown if the pardon was issued before or after William Brandon left England to join Henry Tudor. If it was before and William knew of it, it may be that he did not trust Richard III. Or perhaps it was simply too late and Brandons had no knowledge of the pardon. Either way William Brandon II and his younger brother Thomas had thrown their lot in with Henry Tudor.

Less than a month later, on the 11th April William Brandon II was being referred to as a rebel in government documents. Three months later on the 7th July an act of Attainder was passed on William Brandon II. The act stripped Brandon of all his land, manors, property and wealth, which reverted to the Crown. In addition to this, the act charged Brandon with high treason. If caught his sentence would be death.

While this was happening William’s father, Sir William Brandon fled into sanctuary at Gloucester. Unfortunately, it is unknown what Robert Brandon, the middle son, was doing during this time. Perhaps he was simply laying low, trying to keep out of Richard III’s gaze.

On the 1st of August, after fourteen years of exile, Henry Tudor set sail from France to lay claim to the English throne. He set sail from the port of Harfleur accompanied by approximately 2,000 soldiers, one of those being William Brandon II. It is unknown if Thomas Brandon accompanied Henry, there are no records of him over the next few months. If he did not travel with his brother, it may be that he remained in France with William’s wife and newborn son, the future Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk.

The fleet landed on the 7th of August at Mill Bay six miles west of Milford Haven located along the Pembrokeshire coastline. Over the next two weeks Henry Tudor and his men marched across England gathering support and soldiers as they went. On the 21st August Henry chose to knight several men who had shown great loyalty to him throughout his time in exile, one of these men was William Brandon II.

The Battle of Bosworth Field took place on the 22nd of August 1485. It is estimated that Henry had an army of between 5 – 8,000 soldiers and Richard III had 12 – 20,000 men. Thomas and William Stanley had a combined force of approximately 6,000 men but they had not yet committed to either side. Sir William Brandon had been chosen to be Henry’s standard-bearer.

The battle was fierce and as the battle continued Richard III, despite being told to flee, saw an opportunity to charge at Henry Tudor. As he and his men surged forward, his aim to bring down Henry, his lance pierced Sir William Brandon II and broke in half. History records that William Brandon ‘hevyd on high’ [the Tudor standard] ‘and vamisyd it, tyll with deathe’s dent he was tryken downe.’

The Banners of Richard III and Henry Tudor at Bosworth

The Banners of Richard III and Henry Tudor at BosworthSir William Brandon II had given up everything to join Henry Tudor’s cause. Richard III had passed an Act of Attainder upon him, his land, his property and wealth forfeited and his life worthless. He had bid goodbye to his wife and baby son, sailed to England and ultimately given his life fighting for Henry Tudor’s cause.

Richard III and his men continued fighting and it was at this point that William Stanley and his men charged down in support of Henry Tudor and the rival armies clashed. At some point, Richard III was killed.

After Henry was declared victorious, he ordered that all those who had died to be buried, many of those being at the nearby church of St James the Greater, Dadlington. Sir William Brandon II was the only member of nobility on Henry Tudor’s side killed at Bosworth. Unfortunately, the exact location of Brandon’s grave remains unknown.

While the fortunes of the Brandon men had suffered under the reign of Richard III, with William Brandon II losing his life, when Henry VII claimed the throne fortune’s wheel turned upwards for the surviving Brandon men.

Henry VII reappointed Sir William Brandon I to the position of Marshall of the King’s Bench, of which he had been dismissed by Richard III. In addition to this he knighted Robert Brandon in 1487 and Thomas Brandon in 1497. He also trusted all three surviving Brandon men with overseeing various judicial matters across the country.

In 1499 Thomas Brandon was appointed as Master of the Horse, a position he was reappointed to under the rule of Henry VIII. In January 1503 Sir Thomas was part of a select group of ambassadors sent to meet with Maximillian I, Holy Roman Emperor in order to discuss the Emperor becoming a member of the elite Order of the Garter. He was also tasked with trying to persuade the Holy Roman Emperor not to support the staunch Yorkist, Edmund de la Pole, 3rd Duke of Suffolk.

In addition to all of this, in April 1507 Sir Thomas Brandon was elected into the Order of the Garter and also appointed as Marshal of the Court of Common Pleas.

The fortunes of the Brandon men suffered greatly under the rule of Richard III. For whatever reason the family became dissatisfied with Richard III. Perhaps they believed he did not deserve to be King, thinking instead the throne should have passed to Edward IV’s son. Or maybe they were simply unhappy with how Richard III sought to rule the country. For whatever reason the Brandon men threw their lot in with Henry Tudor. They had lost their freedom, their land and property and William Brandon II lost his life, but in 1485 their gamble paid off when Henry VII proved victorious at Bosworth. The first Tudor king proved to be a loyal King and lifted the Brandon men back to prominence.

Biography:

Sarah Bryson is a researcher, writer and educator who has a Bachelor of Early Childhood Education with Honours. She currently works with children with disabilities. She is passionate about Tudor history and has a deep interest in the Brandon family who lived in England during the 14th and 15th centuries. She has previously written a book on the life of Mary Tudor, sister of Henry VIII and wife of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk. She runs a website and facebook page dedicated to Tudor history. Sarah lives in Australia, enjoys reading, writing and Tudor costume enactment.

Links:

Website: https://sarah-bryson.com/

Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/SarahBryson44

Amazon: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Brandon-Men-Shadow-Kings/dp/1445686279

Enjoy the rest of Sarah’s Blog Tour

Enjoy the rest of Sarah’s Blog TourSources:

Brady, Maziere, The episcopal succession in England, Scotland and Ireland, A.D. 1400 to 1875: with appointments to monasteries and extracts from consistorial acts taken from mss. in public and private libraries in Rome, Florence, Bologna, Ravenna and Paris (Rome: Tipografia della Pace, 1876).

Bradley, John, John Morton: Adversary to Richard III, Power Behind the Tudors (Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing, 2019).

Burke, John, A genealogical and heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland, enjoying territorial possessions or high official rank, but uninvested with heritable honours, Volume 1, (London: R Bently, 1834).

Calendar of the patent rolls preserved in the Public Record Office, 1476–1485 Edward IV Edward V Richard III. Great Britain.

Calendar of the patent rolls preserved in the Public Record Office, 1485–1494 Henry VII v. 1. Great Britain

Calendar of the patent rolls preserved in the Public Record Office, 1494–1509 Henry VII v. 2. Great Britain.

Calendar of State Papers Relating To English Affairs in the Archives of Venice, (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1871).

Campbell, William, Materials for a history of the reign of Henry VII: from original documents preserved in the Public Record Office (London: Longman & Co, 1873).

Clowes, William, Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records, Volume 9 (London: Clowes and Sons, 1848).

Ellis, Sir Henry, Three books of Polydore Vergil’s English History: Comprising the reigns of Henry VI., Edward IV., and Richard III (London: Camden Society, 1884).

Gairdner, James, History of the Life and Reign of Richard the Third (Cambridge: University Press, 1898).

Gairdner, James, Letters and Papers Illustrative of the Reigns of Richard III and Henry VII (London: London, 1861).

Harris Nicolas, Sir Nicholas, History of the Orders of Knighthood of the British Empire; of the Order of the Guelphs of Hanover; and of the Medals, Clasps, and Crosses, Conferred for Naval and Military Services, Volume 2 (London: John Hunter, 1842).

Hutton, William, The Battle of Bosworth Field, Between Richard the Third and Henry Earl of Richmond, August 22, 1485 (Fleet Street: Nichols, Son, and Bentley, 1813).

Meyer, G.J., The Tudors The Complete Story of England’s Most Notorious Dynasty (New York: Delacorte Press, 2010).

Royle, Trevor, The Wars of the Roses, England’s First Civil War (United Kingdom: Abacus, 2009).

Skidmore, Chris, The Rise of the Tudors The Family That Changed English History (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2013).

Tudor Chamber Books, Kingship, Court ad Society: The Chamber Books of Henry VII and Henry VIII, 1485–1521 (The University of Winchester) <https://www.tudorchamberbooks.org/>.

February 7, 2021

The More I Read

A paper by Professor Tim Thornton of the University of Huddersfield, first published on 28 December 2020 and available here, has reached the national press, for example here, with claims that it has solved the mystery of the Princes in the Tower and proven the version of events provided by Sir Thomas More to be accurate. The paper is very interesting in its consideration of the emergence and evolution of the stories of the Princes in the Tower, with a focus on Richard III’s culpability in the murders. However, it will come as little surprise that I don’t see anything conclusive, and I concede that efforts to portray it as resolving the mystery may be tabloid clickbait headlines rather than Professor Thornton’s assertion, while noting that he believes it means More ought to be given almost unquestioned credence. The paper overlooks several aspects of More’s account as it reaches to establish the veracity of his version of the events of 1483.

The Princes in the Tower

The Princes in the TowerEssentially, the proposition is that the two sons of Miles Forrest, one of those More identifies as the murderers of Edward V and Richard, Duke of York, the Princes in the Tower, were at the court of Henry VIII, and acted as servants of Cardinal Wolsey. Having come into contact with Sir Thomas More, their testimony against their father is assumed to have been volunteered and used by More to record a true and accurate account of the murders thirty years later. I have previously written about my issues with More’s Richard III as historical evidence, including here and here, but I thought I would address it again in light of this new connection.

Professor Thornton is clear that the Forrest brothers, named Edward and Miles, cannot be definitively identified as the sons of the Miles Forrest of More’s account. The evidence cited is, though, compelling enough to accept that they probably were the sons of the servant of Richard III associated by More with the murders. The assertion that they came into contact with Sir Thomas More on occasions is established, but otherwise uninterrogated. There is an assumption that they were willing to tell the story they knew about their father to More for inclusion in his version of the event of 1483. This relies on the brothers knowing the story. When Miles Forrest died in 1484 and his widow and son Edward were provided an annuity by Richard III, no age is given for Edward, but there is a presumption that he was still quite young. The younger sibling, Miles, is not mentioned at all, suggesting he may have been no more than a babe, or even that he was born after his father’s death.

Assuming for a moment that Miles Forrest took part in the murders as More asserts, the Forrest brothers must have been too young in 1484 to have known or understood what their father had done. How, then, did they come to know such a story? Their mother may have told them, or another close associate of their father, but to what end? If it was such a secret that no one knew of Miles Forrest’s involvement until his sons told More, why perpetuate a tale that could only damage the family? Why would the Forrest brothers have been willing to believe the slur on their father if it were related to the years later?

Assuming Miles Forrest was involved in the murders, and his sons knew of their father’s crime, the next problem is their willingness to tell the story to Thomas More. As servants at court associated with Henry VIII and Thomas Wolsey, but not with service to Thomas More directly, it is hard to unravel a circumstance in which they would have volunteered such a dark family secret to a virtual stranger, even if they were aware he was writing about the events of 1483. As Professor Thornton points out, both men continued a long and successful career, unhampered by their willing association with the most heinous deed in living memory and beyond. Perhaps the sins of the father would not be held against the sons, but I am less certain that the risk would be one worth taking.

So, for me, the connection is interesting, but does not convince me of More’s veracity. The fact of their affiliation in an official capacity gives no hint at the nature of their relationship. The brothers donating information to More that damned their father suggests a level of trust and perhaps even friendship that cannot be evidenced. If the Forrest brothers were rivals during More’s rise, friendly or otherwise, they may have been eviscerated in his story in recompense for some trespass or perceived slight. It is hardly the act of a friend to accuse one’s father of the double murders of royal children.

Part of what makes the account offered by Thomas More superficially plausible is his use of real people sprinkled throughout his narrative. He is the first to involve Miles Forrest and John Dighton, the former clearly identifiable, the latter less definitively so. The messenger used by Richard, ‘one Iohn Grene whom he specially trusted’ possesses a name so common there are several candidates, meaning he may or may not have been real and involved. Of these three names introduced together by More, only one can be confidently attached to a person within the historical record. The other two may, or may not, have existed as the men used by More.

More is the third writer, after Polydore Virgil (some time between 1506 and 1513) and Robert Fabyan (some time between 1504 and 1512), to identify Sir James Tyrell’s involvement. All three accounts date from after Tyrell’s execution in 1502. More’s, however, written after the other two, is the only account to mention a confession of the murders of the Princes in the Tower being given by Tyrell at the time of his arrest, a detail even later Tudor writers appear unaware of. This requires More to have cognisance of something unknown to Virgil, Henry VII’s official court historian, writing almost contemporaneously. It would be odd for Virgil to be unaware of the confession, or for him to know of it, and accuse Tyrell without providing the confirmation offered by his confession. Given that an unverifiable family legend claims that James Tyrell hosted the Princes and their mother at his home at Gipping Hall when Richard III facilitated their meetings during his reign, More and others potentially seized on this truth of his involvement in their story to attach him to tales of their murders. All of the best lies are wrapped around a kernel of truth.

There is at least one other example of More’s incorrect use of a real person to blur or obscure the truth in his telling of Richard III’s story. More’s description of the emergence of the pre-contract story that ultimately led to the decision to bar Edward IV’s sons from the throne on the basis of illegitimacy is startling in bearing all of the hallmarks of throwing the kitchen sink at the problem. Dr Ralph Shaa’s sermon at St Paul’s Cross began, More relates, by alerting the people ‘that neither King Edward himself nor the Duke of Clarence were lawfully begot’.1 In the charge that Edward was described as illegitimate, More appears to follow Dominic Mancini’s difficult, and often inaccurate, account of events. Mancini, an Italian visitor to England in the pay of the French court, most likely as a spy, spoke no English and never met any of the central figures in the story he relates. Mancini himself describes his wish not to write down his account, but his resignation to doing so at the insistence of his patron.2

King Richard III

King Richard IIIMancini relates that the sermon insisted ‘that the progeny of King Edward should be instantly eradicated, for neither had he been a legitimate king, nor could his issue be so. Edward, they say, was conceived in adultery’.3 Here, Mancini probably betrays his continental bias and lack of understanding of England and English. The story that Edward was illegitimate, the son of an archer who shared his huge frame, was current at the French court throughout the reign of Edward IV and was a favourite joke of King Louis XI. Unable to understand what was said, if he even witnessed the sermon, Mancini layers what he knows, and what he believes his audience will appreciate and relate to, over the gaps in his comprehension. Mancini later adds that Shaa ‘argued that it would be unjust to crown this lad [Edward V], who was illegitimate, because his father King Edward [IV] on marrying Elizabeth was legally contracted to another wife to whom the [earl] of Warwick had joined him.4

More uses this charge, demonstrating that Mancini’s account may well have been in circulation in England, since no other contemporary or near contemporary, and no English, source mentions it. He adds the claim that the sermon designated George, Duke of Clarence as illegitimate too. This is novel. The reason for Clarence’s exclusion, or rather that of his children, since he had been executed in 1478, was his attainder for treason which parliament extended to exclude his descendants from the line of succession.5 Mancini was clear that this was the reason for the exclusion of Clarence’s children from consideration; ‘As for the son of the duke of Clarence, he had been rendered ineligible for the crown by the felony of his father: since his father after conviction for treason had forfeited not only his own but also his sons’ right of succession.’6 The Crowland Chronicler concurs that this was the reason for overlooking Clarence’s children; ‘the blood of his other brother, George, Duke of Clarence, had been attainted’.7

More continues to describe the pre-contract, the legal basis on which Edward IV’s children were declared illegitimate due to bigamy, naming Dame Elizabeth Lucy as the wife of King Edward IV before his marriage to Elizabeth Woodville. More then explains that Dame Elizabeth Lucy was brought to London in 1483, only to deny that she had been married to Edward IV.8 Mancini believed the pre-contract related to a marriage made by proxy by the Earl of Warwick on the continent.9 The lady identified as Edward’s first wife was, in fact, Lady Eleanor Butler, née Talbot, a daughter of the Earl of Shrewsbury, who had died in 1468.10

Sir Thomas More

Sir Thomas MoreElizabeth Lucy was a long-term mistress of King Edward IV, and was possibly the mother of one or more of his illegitimate children, perhaps including Arthur Plantagenet, Viscount Lisle. Her introduction by More into the story of the pre-contract in 1483 demonstrates the use of real, documented people improperly within the story to both add credence to his version and remove credibility from Richard III during the events of 1483. It is possible that Miles Forrest served a similar purpose for More. Details are also added by More that do not appear in other versions before or immediately after he wrote his account. Most notable of these is the supposed confession provided by Tyrell and John Dighton, Miles Forrest’s accomplice. ‘Very truth is it and well known that at such time as Sir James Tyrell was in the Tower, for treason committed against the most famous Prince, King Henry the Seventh, both Dighton and he were examined, and confessed the murder’.11 The phrase ‘Very truth is it and well known’ reads a little like ‘honest guv’nor’, particularly when no other writer records something supposedly well-known and so critical to the establishment of Richard III’s, and Tyrell, Forrest and Dighton’s, guilt. The introduction of the idea that Dighton ‘yet walks alive, in good possibility to be hanged ere he die’ only seems to add more incredulity to the tale. A confessed regicide and child murderer is simply allowed to walk away after confirming his guilt? Miles Forrest is described as ‘a fellow fleshed in murder’ when explaining his selection for the job of killing the Princes, so if his sons were More’s source of detail about their father, they must have despised the man who died when they were both young, possibly too young to even remember him.

The proliferation of other fates ascribed to the Princes in the Tower is also suggestive that, despite More’s insistence, their doom in the manner described by More was not well-known. One version that is worth particular mention is that of John Rastell, published in 1529. Rastell related the attempt to smother both boys, during which the younger escaped, was caught and had his throat slit.12 Rastell wrote that there were several theories about what happened to the bodies, including that they were locked alive inside a chest and buried beneath stairs in a similar story to More’s. Yet his first assertion is that they were placed into a chest, sailed along the Thames and thrown overboard on the way to Flanders.13 The variance in the story is narrowing, but more than a decade after More’s version was compiled, it is clear that other narratives still had currency. Rastell’s input is of particular interest because he was Sir Thomas More’s brother-in-law, married to Elizabeth More. Both Thomas and John were lawyers in London too, so it seems striking that more than ten years after More’s account, based on certain knowledge, testimony of witnesses and a signed confession which was ‘well known’, Rastell still presented alternative stories from his brother-in-law; similar, but not identical, still uncertain, and apparently unaware of the confessions.

Conviction that More presented a factually accurate account of events is demonstrably incorrect. The very first sentence of his The History of King Richard the Third is erroneous, not as a matter of interpretation or opinion, but of fact. ‘King Edward, of that name the fourth, after he had lived fifty and three years, seven months, and six days, and thereof reigned two and twenty years, one month, and eight days, died at Westminster’.14Edward IV was born on 28 April 1442 and died on 9 April 1483. He was therefore forty years old, a few weeks short of his forty-first birthday, not fifty-three. Edward ruled from 4 March 1461 to 9 April 1483, barring some six months of the Readeption. He was therefore king for Just over twenty-two years, or twenty-one and a half excluding the Readeption, but not twenty years, one month, and eight days by any measure. More therefore begins with an error, compounded by the precision he claims, down to the number of days. If the counter to this observation is that More surely meant to go back and check his data, then why be so precise, and why never correct something relatively easy to confirm, and why assert hids other claims are unquestionably true? Part of the reliance on More is anecdotally based on assertions that as a lawyer and a devout man, he would do his research properly and would not present lies, yet he does just this with his first sentence. He goes on to describe Edward V as ‘thirteen years of age’ when he was in fact twelve years, five months old, and his brother Richard as ‘two years younger’ when the Duke of York was nine years and seven months old at the time of their father’s death, three years younger.15

King Edward IV

King Edward IVIt is worth considering what More hoped to achieve by writing his History, and whether it ought to be considered a work of history as it might be presented today. I believe More’s work should be read as rhetoric and allegory rather than a factual work of history. More’s other famous work, Utopia, describes a perfect society. The full title of the work, published in 1516, at the same time More was gathering his story of Richard III together, translates as ‘A little, true book, not less beneficial than enjoyable, about how things should be in a state and about the new island Utopia’. A true book about a fiction island? More’s ideal pardise has many striking features; slavery (each household has two slaves) raises the question of whether the perfect society is perfect for everyone. There is no private property, euthanasia is legal, priests are permitted to marry, and a number of religions exist tolerant of each other. These are all societal structures held up as a model of perfection, but which More himself fundamentally disagreed with.

The errors that open his History are perhaps the clearest signpost that what follows is not an accurate relation of history. It may, or may not, be pertinent that King Henry VII (28 January 1457 – 21 April 1509) was fifty-two at his death, much closer to More’s description of Edward IV’s age. The two innocents destroyed for the new regime that wished to establish itself on the death of the old king might be intended to represent Sir Edmund Dudley and Sir Richard Empson, executed on 17 August 1510. Though they were not innocents in the sense that young children were considered to be, nevertheless they were arrested on Henry VIII’s accession and subsequently executed for no crime but doing as Henry VII had instructed them. It was a cynical and brutal bid for popularity. If read through this lens of contemporary political commentary, Richard III is used a vehicle to safely deliver an otherwise dangerous message; that tyrants who begin their reigns with unjustifiable murders risk losing the kingdom, the crown, and their lives.

The development of the manuscript through the 1510’s could have been a reaction to this unnerving early sign of reckless tyranny by the young Henry VIII. The work could then have been abandoned as More moved into royal service and either hoped to affect and influence the king and his policy in person, or felt the device too dangerous. The risks were something Sir Thomas would have been acutely aware of, if his son-in-law William Roper is to be believed. Roper related that Thomas More had, in parliament in 1504, made an eloquent and impassioned speech against Henry VII’s taxation that had affected the king’s income and led to the arrest of his father Sir John More on trumped-up charges as a warning to the young lawyer, who was protected by parliamentary privilege.16 Whatever the truth, More did put his manuscript down and never completed or published it, both tasks later undertaken by his nephew William Rastell, son of More’s sister Elizabeth and brother-in-law John.

John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury

John Morton, Archbishop of CanterburyAs a lawyer, More’s Richard III may have been little more than a legal exercise that was never meant for public consumption. Utopia was an example of arguing for a set of beliefs and standards that More fundamentally disagreed with. Can a case be constructed with minimal evidence and all of it circumstantial and hearsay testimony? Was he testing his own belief in Richard III’s character and guilt based on the stories related by his former patron Archbishop Morton? Was the manuscript Morton’s work, revisited by a former pupil, but abandoned for lack of evidence and the obvious errors included? Thomas More spent time as a teenager in the household of John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury and Chancellor after the accession of Henry Tudor. Morton was an inveterate and irreconcilable enemy to Richard III for reasons that remain unclear, and was arguably the greatest beneficiary of the Tudor victory at Bosworth besides the new king. This raises the possibility that More’s understanding of Richard III’s story was heavily influenced by Morton, who told the tale both to explain away his own part in treason and to indoctrinate young men into a new regime, strengthening its foundations, to protect his new prominence. Professor Thornton suggests that Morton’s personal testimony could have informed More’s reference to strawberries at the 13 June 1483 council meeting,17 but this would require the addressing of More’s additional reference to Richard’s withered arm, displayed at the meeting, which his skeletal remains have proven not to have existed.18 In addition, More repeats the claim that Lord Stanley was not only at this infamous meeting, but was injured and arrested.19 No contemporary source places Lord Stanley at the Tower that day, and the suspicion of his involvement in treason and arrest on 13 June makes little sense in light of his position carrying the Constable’s mace at Richard III’s coronation on 6 July.20

More potentially explored the use of a legal charge of notoriety to establish guilt in a crime. He may have been aware that a significant element of Titulus Regius, the act of parliament in 1484 that set out Richard III’s title to the crown, rested on a charge of notoriety to place a burden of proof on the accused.21 In Titulus Regius, the burden of proof was placed on the children of Edward IV to prove their legitimacy because of the notoriety attributed to the claim that Edward IV had married their mother bigamously. Titulus Regius purported to be a replication of the petition placed before Richard III in June 1483 asking him to take the throne. At the time, the children of Edward IV were not in a position to defend their legitimacy, so the charge of notoriety was a mechanism to avoid the scrutiny of an ecclesiastical court, to the jurisdiction of which a charge of legitimacy should usually have been referred. By 1484, More contended that the Princes were dead, so unable to counter the charge of notoriety. In More’s story, ‘Very truth is it and well known’ serves the same purpose. It introduces notoriety, placing the burden of proof on the accused who, in Richard III, is certainly dead and unable to refute the charge. Did the lawyer in More wonder whether this was enough to prove the case? He may be disturbed to find that 500 years after he wrote it, his unpublished work is used widely as proof of Richard III’s guilt and the detailed manner of the murders, as well as to convict Sir James Tyrell, John Dighton, and Miles Forrest of involvement.

Professor Thornton’s discovery of a connection between Sir Thomas More and two men who may well have been the sons of Miles Forrest is a fascinating addition to the thin but important bank of information on the events of 1483. No evidence appears to survive as to the nature of their relationship, so More’s use of the man likely to have been their father may be the result of rivalry or animosity as easily as a voluntary confession. It also does little to add weight to the claim that More’s work is accurate and to be believed. There remain too many unaddressed inaccuracies and problems, the above being by no means an exhaustive survey thereof. Contemporaries provided different versions of the event More described as well-known. His brother-in-law published an account more than a decade after Sir Thomas laid down his manuscript that was similar enough to suggest they had discussed it, but different enough to highlight the uncertainty still alive in 1529. The fixation on More, the desperation to prove his version of events authentic and truthful, and to attribute the murders of the Princes in the Tower to their uncle King Richard III consistently refuses to allow sufficient attention to other potential suspects, but ignores the much bigger question that the available evidence begs. What if there was no murder of the Princes in the Tower in 1483 at all? The narrow debate continues to detract from some of its most fascinating elements.

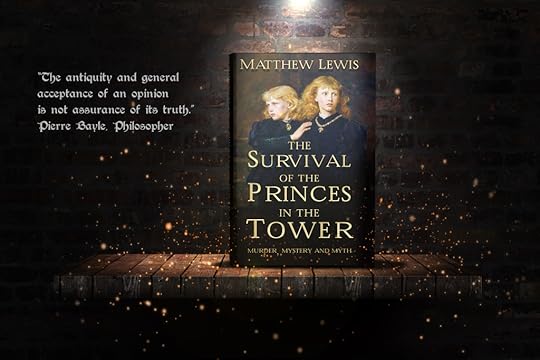

The Survival of the Princes in the Tower explores the theories the sons of Edward IV were not murdered in 1483.

The Survival of the Princes in the Tower explores the theories the sons of Edward IV were not murdered in 1483.Footnotes

Richard III The Great Debate, ed. P. Kendall, The Folio Society, 1965, p86The Usurpation of Richard III, Dominic Mancini, trans C.A.J. Armstrong, Alan Sutton Publishing, 1989, p57The Usurpation of Richard III, Dominic Mancini, trans C.A.J. Armstrong, Alan Sutton Publishing, 1989, p95The Usurpation of Richard III, Dominic Mancini, trans C.A.J. Armstrong, Alan Sutton Publishing, 1989, p97Rotuli Parliamentorum, Vol VI, pp193-5The Usurpation of Richard III, Dominic Mancini, trans C.A.J. Armstrong, Alan Sutton Publishing, 1989, p97Ingulph’s Chronicle of the Abbey of Croyland, trans H.T. Riley, London 1908, p489Richard III The Great Debate, ed. P. Kendall, The Folio Society, 1965, pp84-5The Usurpation of Richard III, Dominic Mancini, trans C.A.J. Armstrong, Alan Sutton Publishing, 1989, p97Rotuli Parliamentorum, Vol VI, p241; Ingulph’s Chronicle of the Abbey of Croyland, trans H.T. Riley, London 1908, p489Richard III The Great Debate, ed. P. Kendall, The Folio Society, 1965, p106The Pastyme of the People, J. Rastell, 1529, p139The Pastyme of the People, J. Rastell, 1529, p140Richard III The Great Debate, ed. P. Kendall, The Folio Society, 1965, p31Richard III The Great Debate, ed. P. Kendall, The Folio Society, 1965, p31The Lyfe of Sir Thomas Moore, Knighte, William Roper, ed. E.V. Hitchcock, London, 1935, pp7-8More on a Murder, Professor T. Thornton, The Historical Association, 2020, p20Richard III The Great Debate, ed. P. Kendall, The Folio Society, 1965, p70Richard III The Great Debate, ed. P. Kendall, The Folio Society, 1965, p71Richard III: Loyalty Binds Me, M. Lewis, Amberley Publishing, 2018, pp272-5Richard III: Loyalty Binds Me, M. Lewis, Amberley Publishing, 2018, p295 __ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-601fb62dccf45', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });October 2, 2020

Online History Talk

I’m planning to do a series of talks online using Crowdcast. This year has seen all of my in person speaking engagements cancelled, so I thought I’d try to find a way around it. Engaging with audiences and talking about my research and books is one of the most enjoyable aspects of this historian and author lark, and I’ve missed it this year.

Yes. It’s also left a dent in my income that I need to fill. Although I still can’t deliver talks face to face, this seems like a good compromise which I hope you will be able to enjoy.

The first talk covers the year 1450, and serves as background to the causes of the Wars of the Roses, and to the birth of Richard III, who is sure to be the focus of later talks.

So, if you’d like to see the talk, please grab your ticket and I’ll see you there.

September 24, 2020

Princes in the Tower Documentary

Yikes!! The fantastic History Hit have released the documentary we did on the #PrincesInTheTower and #RichardIII.

September 9, 2020

Richard III Movie News

I hope this will help to put some minds at ease.

[image error]Steve Coogan

There has been an explosion of interest in the announcement made by Steve Coogan last week that he is due to start filming a movie about Philippa Langley’s search for Richard III. I’ve seen a lot of slightly nervous noise on social media about the film. The main concerns seem to be that it will be a comedy, and that it will make fun of the dig, of those involved, and of Richard III.

We need Corporal Jones. Because there is absolutely no need to panic, Mr Mainwaring, or anyone else.

[image error]

Philippa has confirmed that she’s closely involved with the film.

The second thing to note is that it will not be a comedy. Steve Coogan is co-writing the script with Jeff Pope, a pairing that first delivered the BAFTA award-winning and four-time Oscar nominated Philomena in 2013. Steve Coogan will play Philippa’s husband in the movie – no news yet on who might be playing Philippa though. Jeff Pope is a multi-award-winning writer and the Head of Factual Drama at ITV Studios. This will be a drama, a human story, and not a comedy. Oscar-winning director Stephen Frears, who directed Philomena, The Queen and A Very English Scandal, is also rumoured to be attached to the project.

[image error]Jeff Pope

Steve Coogan and Jeff Pope made a low-key visit to the Richard III Visitor Centre in Leicester as long ago as 2017 as part of their research work on the project.

With filming due to begin next year, more details will hopefully be forthcoming soon. In the meantime, it’s exciting to look forward to a serious film that will explore the drama of a search against all the odds for the remains of one of history’s most famous kings. And it’ll be weird to see some friends portrayed in the film!

August 31, 2020

Author Interview with Toni Mount

Toni Mount’s new novel The Colour of Shadows, the eighth instalment of her brilliant Seb Foxley Mysteries, is release tomorrow, 1 September 2020. At last, this year has a bit of good news! Toni has been on a blog tour this month preparing for the launch. You can catch up with her fascinating posts at any of her stops.

[image error]

Toni is a writer of fictional novels set in medieval London as well as several highly recommended non-fiction books on the period. Frequently giving talks as her alter ego, the medieval housewife, Toni is an expert on the aspects of day to day medieval life that too often go unnoticed, but which give her novels depth and offer readers an almost tangible medieval world to stroll through. I would say that you can almost smell the streets of London, but I’m not sure that would sound like the compliment I’d intend it to be!

The Colour of Shadows sees the intrepid Seb Foxley confronted by the body of a child found in his workshop, another missing boy, and a race against time that drags him into London’s grubby underbelly. All this while an old nemesis returns to add to his troubles. Can Seb and his growing family survive what The Colour of Shadows has in store?

I was lucky enough to catch up with Toni for an interview to celebrate the release of her latest novel.

Do you prefer writing fiction or non-fiction? Why?

Both require quite a bit of research which I always enjoy. Often, I’ll discover a gold nugget during my research and it will spark a story line for a new novel or another idea for a factual book, so sometimes, rather than researching material for a book, it works out that the research inspires a book. I enjoy the discipline of non-fiction writing but have to admit that the freedom to invent characters, situations and events, let my imagination fly – within reason – is a wonderful experience.

How do you go about researching the detail that makes your books feel so real?

Much of my daily life in medieval London research was done years ago, partly to set the tone for a Richard III trilogy of novels [originally saved on 30 floppy disks, if you can remember that far back, then saved on CD but otherwise never seen] and as background stuff for my Medieval Housewife persona. Then back in 2014 I wrote my most successful non-fiction book Everyday Life in Medieval London – I’ve become a bit of a specialist on everyday medieval life and I’m always adding new material as I discover it. Caroline Barron’s London in the Later Middle Ages is my bible with its lists of Lord Mayors, sheriffs, coroners, street maps etc. When I visit the modern city, I tend to find my way using my medieval mind map, thinking ‘the Panyer Inn was here, so Seb’s house would have been there’. Fortunately, the stinks have to be my invention. I have been known to get lost because many churches and other medieval buildings that once were there weren’t rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1666.

Other than Seb, do you have a favourite character?

I love most of the good guys and Seb’s family feels almost part of my own. In fact, my sons commissioned a portrait of Seb for my big birthday recently and it hangs over the fireplace as if he was an ancestor. My favourite in previous stories was Jack but he’s growing-up and moving on now. Thaddeus Turner, the City Bailiff, is coming to the fore in more recent books and if readers want to know what he looks like, he’s based on Aiden Turner – hence the name – as he appears in TV’s Poldark series.

[image error]Seb Foxley by Dmitry Yakhovsky

Is it fun writing the bad guys too?

Oh, yes, the bad guys are tremendous fun. I know Ricardians hate me for it but having Francis Lovell, Richard’s best mate, as a recurring villain and two-faced Janus is so enjoyable [see The Colour of Poison and The Colour of Shadows]. I apologise [a tiny bit] to his fans. Elizabeth Woodville and her brother Anthony appeared as the baddies in The Colour of Murder and that was huge fun. Others of my villains are entirely fictional, like the murderous priest in The Colour of Cold Blood and the new villains in the book I’m writing now [The Colour of Evil] give me so much pleasure.

If you were transported to Seb Foxley’s London, what would you miss the most about the present (2020 being a bad example!)

Coffee. How would I survive without it? I’ve never tasted genuine medieval ale. It was probably sweeter than modern beer, being made without hops, and less alcoholic, otherwise everyone would have lived permanently inebriated and woken with a hangover every day. Even so, I wouldn’t want to live on the stuff and where would I be without caffeine? Tea and chocolate are also vital. Hot showers and a washing machine – I like to be clean without too much effort. And without modern medicine, I wouldn’t be here… The list is a long one.

Seb is exposed to London’s grubby underbelly in The Colour of Shadows. How dodgy were places like Bankside?

Crime was rife there, south of the Thames, but I think the medieval perception of Bankside probably made it seem even worse than it was. It’s hard to gauge because crimes are recorded in numerous contemporary sources: Court Rolls, Plea & Memoranda Rolls, etc. but good deeds are rarely noted to balance the scales. Imagine the picture painted for future historians by modern newspapers. Full of crime, scandal and assorted misdeeds, good news is not regarded as worthwhile because it doesn’t sell but there are plenty of decent, kind people out there who don’t make the headlines – the marvellous Captain Sir Tom being a worthy exception.

If anyone hasn’t started the Seb Foxley Series yet, with The Colour of Poison, why should they join Seb’s adventures?

Historical novels are a brilliant way to get into our history. I failed my History GCSE (or ‘O’ Level exam as it was called centuries ago), that’s how little interest I had in the subject at school. Studying Corn Laws, acts of Parliament, treaties, the Franco Prussian War, entente cordiale… who cares about that? Then, in my twenties, a work colleague lent me a Jean Plaidy novel in her Plantagenet series. Suddenly, history was full of interesting people. [For the O level, Otto von Bismarck got a mention, I think, but Queen Victoria, Gladstone, Disraeli, etc. didn’t.] Characters bring history alive, whether real or fictitious. I began reading non-fiction history and I’m still going. As for Seb’s adventures, they bring a Sherlock Holmes element for readers to get involved with. A decent hero getting into scrapes in medieval London + a whodunnit mystery: what more could a reader want?

[image error]The Colour of Poison: Book 1 in the Seb Foxley Mysteries

The Colour of Shadows is Seb Foxley’s eighth outing. Is he getting tired of all the mystery yet, or does he still have plenty left in the tank?

No, Seb’s not done yet. As I mentioned, The Colour of Evil [no.9] is well on its way and storylines are evolving for The Colour of Rubies [no.10], The Colour of Bone [no.11] and The Colour of Secrets [no.12]. For avid Ricardians, Secrets might throw light on that perennial mystery of the Princes in the Tower. Seb may well be involved and solve that one.

What does your desk look like when you write (if you write at a desk) – tidy and organised, or chaotic mountains of research?

A large pile of books, certainly, and often on wide ranging topics. At present, I’m writing an article on the Lisle Letters and Arthur Plantagenet, so there are a couple of relevant volumes on that. In The Colour of Evil, Seb is commissioned to write a copy of De Re Militari by Vegetius for the king. Richard III had a copy and the details of its content and format are in Sutton and Fuchs work Richard III’s Books, so that’s on the pile. Lots of volumes on medieval sex and marriage because that’s the next factual book I’ve been commissioned to write. It’s a teetering heap but there’s room for my coffee cup, so all is well.

Do you have a favourite medieval word that you’ve come across?

I found some super medieval insults recently – by accident while researching the medieval sex and marriage book but that’s how it often happens – in an academic collection The Trials and Joys of Marriage in the Middle English Texts Series. In ‘The Treatise of Two Married Women and a Widow’ by William Dunbar, a woman is describing her useless husband to her friends. Apparently, he is a wallidrag [a slovenly fellow], a waistit wolroun [lazy oaf], a bag full of flewme [phlegm], a skabbit skarth [a scabby monster (my personal favourite)] and more besides. Sounds like a real sweetheart, doesn’t he? I have just the character to use those words in The Colour of Evil so you’ll find them there in the next novel.

Who is a writer that you admire and think more people should read?

For medieval crime mysteries way back, Ellis Peters’ Brother Cadfael series was full of gems. The TV series starred Derek Jacobi and was brilliant. Can’t imagine why it’s not been repeated. Mel Starr’s Hugh de Singleton novels are in the same vein and worth a look. And of course the master of the genre, C. J. Sansom.

Non-fiction authors I admire include Lucy Worsley, Ruth Goodman and Stephen Porter and, I’m not sure if you’ve heard of him, but Matthew Lewis is to be recommended [There’s a rumour that he writes novels too].

[image error]Derek Jacobi as Ellis Peters’ Brother Cadfael – a fantastic series.

You and I are both Ricardians. What do you think is the enduring appeal of Richard III?

For me, it was always the mysteries surrounding him: was he a great man or a monster? Was he deformed? Was he a serial killer? Finding his skeleton in the car park was a disaster for my personal take on what happened post-Bosworth, the subject of my aforementioned unpublished trilogy. Thank goodness the Crown refuses to allow DNA testing to be done on the bones in the urn at Westminster: I don’t want another mystery solved. The less we know, the more we can imagine.

Thank you Toni for your fascinating answers. You can keep up to date with all Toni’s book news on her website at www.tonimount.com. All of Toni’s novels and non-fiction books are available at Amazon from her Author Page. The Colour of Shadows is available from tomorrow, 1 September 2020, so enjoy a great late summer read with Seb.

June 11, 2020

Eleanor the Crusader

My next book – due for release in October, all being well – is about Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. They were one of Europe’s most fabulous power couples, ruling lands that spread from the North Sea to the Mediterranean. Eleanor was nine years Henry’s senior. When they married in 1152, he was a brash nineteen-year-old, already Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy, and planning to add the crown of England to his already glittering haul. Eleanor was twenty-eight, and until recently had been the Queen of France. Her first husband, Louis VII of France, had arranged for their marriage to be set aside on the favourite grounds of consanguinity – being too closely related. He had failed to foresee her swift remarriage to one of his most impressive and therefore threatening subjects.

Everything had come to Henry easily in his teens. His father, Geoffrey the Handsome, Count of Anjou, had conquered Normandy and handed it to his son, and with Geoffrey’s death in 1151, Anjou had also come into Henry’s possession. If his start had been impressive, the rest of his life was to be a story of epic successes, heartbreaking setbacks, war and high politics. By the time of their marriage in 1152 though, Eleanor already had a vast wealth of experience behind her. Although the vast territories of Aquitaine and the chance to get one over on Louis must have formed part of Henry’s thinking in accepting the match, this intimate familiarity with power, particularly royal authority, probably contributed to Eleanor’s appeal too. Before Henry was out of his teens, she had already lived through more than most would see in a lifetime.

[image error]

The Angevin Empire Controlled by Henry II & Eleanor of Aquitaine

When Louis VII committed to lead the Second Crusade in response to increasingly desperate pleas from the Holy Land for help defending Jerusalem and the states founded by the First Crusade, Eleanor went with him. Many chroniclers point to the king’s puppy-like adoration of his queen, but by 1147 when the host became the journey east, their relationship was not as rosy as it had seemed at first. Louis was a complex character. The second son of Louis VI, he was not born to be king, and his initial education had been a cloistered, religious one. Wrenching him from the surroundings left a deep scar, and the early exposure to the Church’s dislike and distrust of women similarly never healed. Eleanor would famously remark that she feared she had married a monk rather than a king. If Eleanor remained in Paris, she would have a claim to regency powers, and Louis preferred his old mentor Abbot Suger to rule without the potential for a power struggle. Taking Eleanor was more about getting her away from Paris than fear of missing out on her company.

The crusaders left Paris on 11 June 1147, travelling via Metz, through Bavaria, taking two weeks to cross Hungary and arriving at Belgrade in Bulgaria in mid-August. They had been in touch with the envoys of Emperor Manuel Komnenos of the Byzantine Empire, Passage through Constantinople was vital, but the emperor was wary of the approaching army. The king and queen arrived in the fabled city on 4 October. They spent three weeks as the emperor’s guests, staying at the Philopatium, a favourite imperial hunting lodge. The lavish, comfortable surroundings allowed them to recover from their journey and prepare for the hardest part that was still to come. The lighter atmosphere may well have reminded Eleanor of her home in Aquitaine, a bright memory undimmed by the drab, sober dullness of Paris.

[image error]

Eleanor and Louis VII leaving France for the Second Crusade

Before the end of October, the army crossed the Bosporus and entered Asia. They almost immediately came under frequent, probing attacks as they marched onward. In early January 1148, disaster struck, and Eleanor’s reputation began its tumble into scandal and, let’s face it, lies. On 6 January the crusaders had to cross Cadmos Mountain. It was a logistical nightmare for such a vast army under constant pressure from the Seljuk Turks. Command of the vanguard, leading the crossing, was given to Geoffrey de Rancon, a Poitevin and a vassal of Eleanor’s. The plan was for Geoffrey to reach the peak and wait for the rest of the army to avoid them becoming too strung out. When he got there, Geoffrey found there was not enough room for the remainder of the force and moved on to make space for them. The Seljuks took advantage of the situation and attacked the army as it stretched along the mountain roads. It was a slaughter, Louis himself was in grave danger, and forty of his bodyguard lay among the dead. For those increasingly hostile to the Poitevin queen, the failure of one of her vassals was all the ammunition they needed to blame Eleanor for the loss.

The next stage of the journey was no less perilous. Louis paid Greek guides at Attalia to lead the bulk of the army across land while he, Eleanor and some of his men sought safe passage by sea to Antioch. The three-day journey took a fortnight as the fleet was buffeted relentlessly by storms. Only about half of those who marched out of Attalia reached Antioch alive. The Greek guides had taken the king’s money and betrayed his men. The bedraggled force, described by John of Salisbury as ‘the survivors from the wreck of the army’, were at least safe in the embrace of Antioch. Prince Raymond, the ruler of the Frankish outpost, was Eleanor’s uncle, and the chance to see a member of her shrinking family may well have been part of the lure of the Holy Land to Eleanor. Louis and Raymond appeared to get on well, and the time to recuperate was just what the king and his army needed.

Raymond was desperate to obtain Louis’s help with an assault on Aleppo. It was, the prince explained, a critical step in regaining Edessa, the stated aim of the crusade. Louis, quite possibly already disillusioned with the idea of crusading, was focussed only on reaching Jerusalem to complete a personal pilgrimage. Louis, according to John of Salisbury, became annoyed when ‘the attentions paid by the prince to the queen, and his constant, indeed almost continuous, conversation with her, aroused the king’s suspicions.’ He decided to leave Antioch, but Eleanor expressed a wish to stay with her uncle, backing his strategic desire to attack Aleppo. Raymond offered to keep Eleanor safe ‘if the king would give his consent’, but Louis most assuredly would not. John of Salisbury’s is the earliest account of the rumours that grew from the disagreement, though he never quite gives full form to the story, nor comments on its veracity. He wrote that one of Louis’s secretaries, a eunuch named Thierry Galeran, who was frequently mocked by Eleanor, suggested that ‘guilt under kinship’s guise could lie concealed’. Driven to distraction, Louis packed his things in the middle of the night, and Eleanor was ‘torn away and forced to leave for Jerusalem’. John concluded that this was the beginning of the end of their relationship. Eleanor questioned the validity of their marriage on the grounds of consanguinity, and ‘the wound remained, hide it as best they might.’

It is from this episode that the rumour later emerged, developed and became entrenched that Eleanor had engaged in a sexual relationship with her uncle at Antioch. It was misogynistic mud-slinging: why else would the queen defy the king, a woman rebuke her husband? It was outside the accepted norm, and it never really occurred to them that Eleanor might have her own mind, her own ideas, and, heaven forbid, a better tactical grasp than the king. Clutching around for an explanation, sex was the only one the men writing down these events could settle on. Women were, they believed, driven by an insatiable lust that caused them to try and lead men astray. Eleanor must have seduced her uncle Raymond and been inspired by lustful desire to defy her husband. Essentially, it meant that the whole mess that the Second Crusade was becoming could be blamed firmly on Eleanor. She had ruined what the men, led by her husband, would have made glorious otherwise. If they had been forced to consider the failures of the king, of the men, or the possibility that God had abandoned them, it opened a whole can of worms. That slippery meal was neatly avoided by blaming Eleanor for being a woman.

For centuries afterwards, this affair was largely accepted as fact and Eleanor’s reputation accordingly tainted. William of Tyre was less discrete than John of Salisbury, writing of Raymond, Louis and Eleanor: ‘He resolved also to deprive him of his wife, either by force or by secret intrigue. The queen readily assented to this design, for she was a foolish woman. Her conduct before and after this time showed her to be, as we have said, far from circumspect. Contrary to her royal dignity, she disregarded her marriage vows and was unfaithful to her husband.’ This is the view of Eleanor that persisted, and which accompanied her into her second marriage to Henry. It coloured the view of all of her actions afterwards, but there is no evidence that it is even remotely true.

[image error]

An Image of Medieval Jerusalem

Louis and Eleanor reached Jerusalem in May 1148. When a council meeting, held by King Baldwin II and attended by Louis, met on 24 June, it was decided that Damascus would be the first target. Raymond and the Count of Tripoli refused to participate in the council meeting, preventing a fully coordinated Christian effort. Still, on 24 July, a month after the meeting, the army arrived outside Damascus. The inhabitants immediately appealed to Nur ad-Din for aid and a vast army was sent to relieve the city. Four days after their arrival, the Christians packed up and left. Louis stayed on in Jerusalem for a while, touring the religious sites. He and Eleanor spent Easter 1149 in the city, at the locations of the crucifixion and resurrection. It was surely an experience to savour at the end of a disastrous expedition.

In April, after increasingly pressing letters from Abbot Suger urging Louis to return, the couple left Jerusalem for Acre. They crossed the sea in separate ships, perhaps a symptom of their worsening relationship. The convoy was attacked and scattered. Louis landed at Calabria, but Eleanor reached land at Palermo, apparently ill. She took several weeks to recuperate before rejoining Louis. The couple made their way to Tusculum, where they visited Pope Eugenius to debrief him on the failures of the crusade. During the visit, Eugenius forbade the couple to mention their consanguinity ever again and provided a bed for them to sleep together in while they stayed with him. Nine months later, they had a daughter, but it was not to save their marriage.

The experience of the Second Crusade must have left a deep mark on Eleanor. She had travelled halfway across the known world, to the place considered the centre of the world. She had endured hardship, faced the mortal peril of battle and constant guerrilla attacks, enjoyed the surroundings of Constantinople and Antioch, where she met her uncle. She had become the increasing focus of an effort to apportion blame for failures, from a vassal disobeying instructions in the mountains to the allegations she had been sleeping with her uncle. In Jerusalem, she had found herself at the religious heart of the world in a profoundly spiritual age. She spent Easter at the very spots Jesus was crucified and resurrected. The journey had ended with the Pope all but forcing her into her husband’s bed to conceive a papally approved child. All this, and she was just twenty-five when she got back to France. Somehow, though, this was not to prove the most dramatic experience of her life. Young Henry was looming on her horizon, and her life would never be the same again.

June 18, 2019

One Final Charge – Please Sign the Petition

What if you could save a 534-year-old piece of history? Well, you can.

Imagine there was a delicate, fragile, but beautifully preserved medieval jewel. It’s yours to enjoy whenever you want and to pass on to your children. Now suppose someone comes along and says they want a piece. They’ll snap it off the side and give the rest back, then you can go on looking at it, but it will always have a piece missing; a jagged edge and a noticeable chunk gone forever. And you’ve got to explain the damage to your children when you pass it on.

That is precisely what is happening at the site of the 1485 Battle of Bosworth, an event that altered the course of English and British history. The autumn of 2018 was a rollercoaster shock to the system. Within days of the Battle of Bosworth Festival Weekend, the news broke that Japanese technology firm Horiba MIRA had submitted a planning application to build a driverless car test track that would encroach onto the registered battlefield site. It seemed impossible that it would be approved, but we watched on, campaigned and screamed in vain as it slid through Hinckley and Bosworth’s planning committee with only a minimal bump; the opposition of a few councillors who were quickly removed from the committee. You can read a bit more about the meeting and the controversy here and here.

Anyway, despite the opposition of the Battlefields Trust, the Richard III Society and a petition that gathered over 15,000 supporters, it was given the go ahead. The formal, written permission was issued on the night of the meeting, which not only prevented an appeal but demonstrated that the decision had been made before the committee even sat down. Presented with a frustratingly smug fait accompli, concerned parties and individuals were left horrified at the impending destruction of the battlefield and the frightening precedent such a move sets for other heritage sites across the country.

Much was made of the minimal area to be affected, but it is the spot on the battlefield that current interpretations give as the approach route and muster point for Henry Tudor’s army. It is in the area where the largest cluster of medieval cannon balls ever found was discovered, and will be built over at least one of the find spots. So, although in percentage terms it represents a small amount of the registered battlefield, it is in the very place at which current thinking places most of the fighting. It might be small, but it is critical.

[image error]

The outline of the proposed development can be seen in red on the western side of the registered battlefield. The red line and arrow shows the route it is believed Henry Tudor took to the battlefield and the area where his army was arrayed for battle. The red circles mark cannon ball finds and the area where much of the fighting is now believed to have taken place.

At the recent local elections, control of Hinckley and Bosworth Council changed to the Liberal Democrats, and it was their councillors who had opposed the approval of the plans. This offers a glimmer of hope for a more sympathetic ear, but it still seemed like a done deal that could not be unravelled.

But it isn’t.

The Town and Country Planning Act 1990 permits the revocation of planning permission after it has been granted and up until such time as the development is entirely completed. Section 97(1) states that ‘If it appears to the local planning authority that it is expedient to revoke or modify any permission to develop land granted on an application made under this Part, the authority may by order revoke or modify the permission to such extent as they consider expedient.’ Section 97(3a) explains that the power may be exercised ‘where the permission relates to the carrying out of building or other operations, at any time before those operations have been completed’. You can read the Act here and a parliamentary briefing on the revocation of planning permission here.

Bosworth Battlefield can still be saved, for this generation and all those that follow. There is a petition on the government’s website asking that this statutory power be used to revoke the planning permission granted at Bosworth. Unfortunately, it can only be signed by UK residents, because this is a matter of international importance that has caused outrage around the globe. If you are eligible, I ask you to sign the petition and help try to preserve this precious medieval jewel. Ask your friends and family to add their weight to the request. At 10,000 signatures, the government is required to respond. At the very least, they will then have to explain why they will not save this precious landscape. At 100,000 signatures, the petition will be eligible for debate in the House of Commons. This might represent our last chance to make it clear to the government and local planning committees everywhere that the destruction of our heritage is too high a price to pay.

https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/261339

[image error]

May 31, 2019

International Trade between Medieval England and Iceland

Guest post by Toni Mount

In my latest Seb Foxley medieval murder mystery, The Colour of Lies, set in London in the 1470s, the trouble begins with the theft of three exceptionally valuable items from a stall during the annual St Bartholomew’s Fair. They are unicorn horns belonging to a Bristol merchant, Richard Amerike (or Ameryk). In the Middle Ages, nobody doubted that creatures with a single horn existed somewhere in the world but they were so illusive and descriptions of them so variable, it was unsurprising that they proved difficult to locate and impossible to identify, yet their horns were real enough, if rare indeed. A unicorn horn could be worth twenty times its weight in gold and a large one could weigh fourteen pounds. Even in small pieces or powdered – a form used medicinally to treat any and every ailment, from plague to piles – it was worth ten times the value of gold. My research into the origins of these marvellous artefacts revealed a surprising source: Iceland. So how might a Bristol merchant have come to acquire the unicorn horns?

[image error]

I had already completed my novel in which Richard Ameryk, a very real medieval merchant from Bristol, appears as a minor character, when I attended the Richard III Society’s conference in early April this year, held at King’s Lynn in Norfolk. Had it not been with the publishers but still a work in progress, I would probably have changed Ameryk’s character for that of a merchant from Lynn because two of the conference speakers – Anne Sutton and Mark Gardiner – informed us about the Norfolk port’s trade connections with Iceland in the medieval period. This article makes full use of the notes I made at the time and Anne’s paper ‘East coast ports and the Iceland trade, 1483-5: (protection and compensation)’ that she so kindly sent me. Also to Mark’s paper: ‘Trading and Fishing Sites in Medieval Iceland’, co-written with Natascha Mehler, which I found on the internet. I’m indebted to both speakers.

England’s main concern with Icelandic trade was fish. The richest fishing was to be had in the seas off the south-west of Iceland and English ships, first recorded in the area in 1412, were there to catch fish themselves as well as trading with the Icelanders for dried cod and vadmal, the local rough sheeps’-wool cloth. The following year, having realised the potential, thirty fishing vessels and a merchant ship arrived. These heralded what the Icelanders call ‘the English Age’ that lasted into the Tudor period. In the 1470s, an average of three merchant ships was sailing to Iceland from Bristol every spring, making the three to six month voyage into the North Atlantic, known then as the Mare Oceanum or the Ocean Sea.

By the mid-fifteenth century, the English, with a thriving woollen textile trade of their own, were less interested in vadmal cloth and the emphasis was on fish. Stockfish was locally caught cod that the Icelanders gutted, filleted, opened up and put on drying racks – known as stocks – to cure in the cold wind and sun. In the process, the fish lost 80% of their weight and would be layered with salt in barrels by which means they would keep for months, years even, long enough to bring them back to Europe. Although some of the fish would be for English consumption, having been soaked overnight to remove most of the salt and reconstitute the flesh, much of it was sold by the Bristol merchants to Portuguese and Spanish traders. At the time, all Roman Catholic countries, including England, were obliged to consume a great deal of fish in accordance with the doctrines of the Church and stockfish was cheap, stored well and was, therefore, available all year round.

Stockfish were traded with Iceland in exchange for basic goods, such as flour, malt, beer, salt, wax, honey, pitch, iron and linen; manufactured metal goods such as copper kettles, knives, horseshoes, swords and helmets; along with luxury items, such as soap, pins, needles and buttons. Oak trenchers and wood for construction and fuel were also tradable items in treeless Iceland. There was a rate of exchange for stockfish, drawn up in 1420, against all these goods since Iceland had no coinage system and remained a barter economy. Yet stockfish was not the only commodity available: Iceland manufactured fish-skin leather goods, purses were particularly popular; shark-skin provided the medieval equivalent of sand-paper and, of course, occasionally ‘unicorn’ horns were available for trade. These were the exquisite, solitary ivory spirals from the narwhal, a member of the whale family then found more frequently in the arctic seas around Iceland.

Ships from Bristol were not the only English vessels making the Iceland voyage. The east coast ports of Scarborough, Hull, Dunwich, Kings Lynn and even London were involved. Many of them were doggers or farcosts, basically fishing vessels that could also carry cargo, but by the 1470s bigger, purpose-built merchant ships, like the three-masted carracks, were making the trip – the fictitious Eagle, as in my novel, The Colour of Lies, is just such a vessel.

Officially, after an international dispute between King Edward IV of England and King Christian I of Denmark and Norway in 1475, English direct trade with Iceland was made illegal, Iceland being annexed to the Scandinavian kingdom. All English vessels were required to have a licence and either trade was to be conducted through the port of Bergen in Norway or else English ships were to stop off there to pay customs dues and tariffs on cargoes bought and sold in Iceland. Records show that a number of east coast merchants paid for licences and others are noted as having visited Bergen to pay the tariffs, yet few appear on both lists, so clearly not everyone was following the regulations. The Bristol merchants appear to have ignored the rules completely, although the west coast fishing vessels somewhat curtailed their efforts in Icelandic waters, finding new fishing grounds further west, off Greenland. The Bristol merchants were hardly inclined to add thousands of hazardous miles to the voyage by sailing home via Norway and the North Sea just to pay customs duties, reducing their profit margins in the process.

Instead, they did much of their business through Galway on the west coast of Ireland. To this Irish port, the Spaniards brought wine, the Portuguese cheap salt and wine. The Bristol merchants would exchange English wool textiles for wine, also for the salt which they required for the next stage of the voyage. In Iceland, English goods and Iberian wines would be exchanged for both stockfish and freshly salted fish. Both commodities needed the cheap salt to preserve them. The English ships carried their own supplies of wooden planks and a cooper to construct the barrels to bring back the fish. Without trees, Iceland had no wood for such purposes. The ships then returned to Galway, selling much of the highly prized fish to the Spanish and Portuguese merchants for a decent profit, taking on more wine for the home market, along with some remaining fish – the Iberians paid more handsomely for codfish than the English and customs duties in Bergen were avoided.

English sources suggest that Bristol merchants did much of their trading in the Icelandic port of Snaefellness on the west coast but my research, carried out in Iceland, seems to indicate that Eyrar – now Eyrarbakki – on the south coast was at the centre of the island’s trade with the English.

[image error]

Detail from Carta Marina by Olaus Magnus, 1531.

Allowing for the inaccuracy of the map above, Eyrar would be situated at the bottom of the island, just left of centre. There are shown the turf-walled booths – the English called them ‘caves’ – roofed with canvas ‘tents’, just as the Icelandic sources describe the English traders using as temporary warehouses. Further to the left, and looking liked stacked logs, are the stockfish, ready for sale. Eyrar was a bustling place during the summer trading season, when local farmer-fishermen would assemble to exchange their dried fish for the basics which Iceland could not produce. Over the winter, the population probably reduced to the six hundred who live in Eyrarbakki today.

As an interesting footnote to trade between Iceland and England, during the reign of Henry VIII, in a single year, 1528, no fewer than 149 English fishing vessels were catching cod in Icelandic waters, using hooks and lines in the traditional way; not nets. In 1509, on becoming king, Henry had unilaterally rescinded the requirement for licences or paying tariffs in Bergen. King Christian II of Denmark and Norway was not amused by this loss of revenue, particularly since, at the time, he was in need of cash. Realising how important this enterprise was to the English and setting previous disputes aside, Christian attempted to mortgage Iceland to King Henry. In 1518, he sent an envoy to Henry, secretly asking for a loan of 100,000 florins, pledging Iceland as collateral. The envoy was instructed to go as low as 50,000 florins, if necessary (today’s equivalent of about 6.5 million US dollars). Nothing came of this because, by that date, Henry himself was in financial difficulties, having spent his father’s bulging treasury on wars and a lavish regal lifestyle. Had Christian made his request just a few years earlier, Iceland may have become part of the United Kingdom.

I hope readers have enjoyed this brief article. I put my research to good use as part of the backstory for my new Seb Foxley medieval murder mystery, The Colour of Lies.

Researched at the Whales of Iceland Museum, Reykjavik, Iceland, 2018.

Researched at the Newport Medieval Ship Centre, South Wales, NP19 4SP, 2017.

Broome, Rodney, Amerike, The Briton who gave America its Name, [Sutton Publishing, Glos, 2002], p.31.

Gissurarson, Hannes H., ‘Proposals to Sell, Annex or Evacuate Iceland, 1518-1868’ [accessed online 29th April 2019].

Toni is a history teacher, a writer, and an experienced public speaker – and describes herself as an enthusiastic life-long-learner; she is a member of the Richard III Society Research Committee and a library volunteer, where she leads the creative writing group.

Toni attended Gravesend Grammar School and originally studied chemistry at college. She worked as a scientist in the pharmaceutical industry before stopping work to have her family. Inspired by Sharon Kay Penman’s Sunne in Splendour Toni decided she too wanted to write a Richard III novel, which she did, but back in the 1980s was told there was no market for more historic novels and it remains unpublished.