Katherine Villyard's Blog, page 5

September 16, 2024

Anne Rice Completionist Kit Giveaway!

Do you love Anne Rice? Do you want ALL of her Vampire Chronicle books?

This prize package contains paperbacks of:

Interview With the Vampire The Vampire Lestat The Queen of the Damned The Tale of the Body Thief Memnoch the Devil The Vampire Armand Merrick Blood and Gold Blackwood Farm Blood Canticle Prince Lestat Prince Lestat and the Realms of Atlantis Blood CommunionAND the two “New Tales of the Vampires” as a single paperback:

PandoraVittorio the VampireAND (US) DVDs of

Interview with the Vampire (1994 film starring Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise)Queen of the Damned (2005 film starring Stuart Townsend and Aaliyah, could only find used, sorry!)Interview with the Vampire TV series season 1 (2022; season 2 comes out on October 8 and I’ll send it to you).AND

A promotional photo of Brad Pitt as Louis (black and white)A script of the TV series pilot (I need to read the fine print, LOL, it has “reprinted” signatures of Jacob Anderson, Sam Reid, Assad Zaman, and Eric Bogosian)A signed photo of Anne Rice!This is a prize package worth over $250, although I’ve seen people selling just the books on eBay for $1195 (okay, two of the eBay ones were signed). Go! Enter now!

All entrants will receive a copy of my vampire short story “Becoming.”

September 2, 2024

COVER REVEAL

I think it’s updated at all retailers where I have preorders, but it’s not instantaneous. So:

I’m madly in love with this cover! It’s perfection!

(Preorders are up some places. More coming soon!)

August 26, 2024

19th century Jewish London

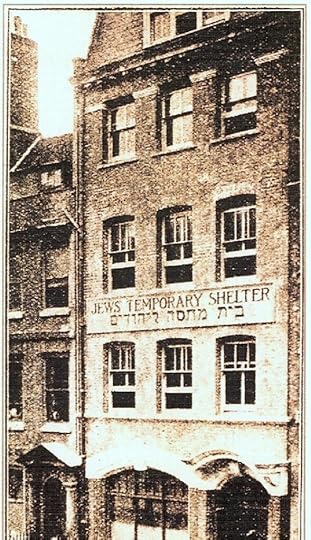

Because it came up recently-ish… 19th century Whitechapel was full of Eastern European Jews. There are modern walking tours of the area to see the Jewish sights.

My character engages with these Eastern European immigrants. The Jewish population in England increased from 46,000 in 1880 to about 250,000 in 1919. To quote the Jewish East End of London page, “The Ashkenazi immigrants were often illiterate, poor and regarded as an embarrassment by co-religionists already settled here.�� These Ashkenazi Jews had fled to the West as refugees from Russian persecution.” The Jewish population of London in 1899 was 135,000.

I don’t consider myself an expert on Jewish history! but I already I knew this from two particular sources, neither of which was particularly flattering: Dracula and Jack the Ripper. Yes, Jack the Ripper was terrorizing a poor Jewish immigrant community! There was graffiti at the time blaming the Jews for Jack the Ripper’s crimes, or at least for sheltering the killer. (See “The Goulston street graffito;” the police suppressed this because they feared it would lead to antisemitic riots.)

Dracula, well. Dracula is in many ways a reverse colonization narrative. There are apparently antisemitic remarks in the book that sailed right over my head because I’m not up on bigoted 19th century stage plays, but… the sly Eastern European count stalking the dark, foggy streets of London can be read as a representation of the influx of Eastern European immigrants, particularly those escaping Pogroms in the Pale of Settlement.

So, my characters know that Whitechapel has a reputation for “being Jewish” and seek Jews there. These characters are Yiddish speakers and eat Eastern European foods. There are lots of great photos here, including Yiddish newspapers and the like.

August 17, 2024

Minotaur

This story originally appeared in in Alien Abduction: Short Fiction on the Themes of Alien and Abduction, September 28, 2015, and was reprinted in Love Stories.

The spires of Miros were tall and slender, much like Ted’s captors. They walked in the streets below the spires that shaded the streets and cast long shadows. Ted’s wrists ached from the manacles. He kept moving, although he stumbled on the stone-paved streets. His Mirosian captors, strong for their slight builds, shoved him forward, and the cold metal crushed his wrists again. As they crossed the street, the light reflected off the guard’s green exoskeleton.

Rumors said the Mirosians worshipped some kind of monster as a God. This God demanded sacrifice. Ted lowered his eyes to avoid glaring at the bald brightness of his captor’s head, and found himself staring at wings instead. There were other rumors, too, tales of insectoid hive minds. The guards murmured among themselves, though, so they must have some individuality.

A small Mirosian child shuddered at the sight of a human, its eyestalks waving and shrinking towards its skull. Ted’s stomach clenched. Other Mirosians flew to entrances above street level. The children were all about the same size, which made him think they were also the same age. He wondered if reproduction had been forbidden during their spaceflight.

As Ted’s captors shoved him down the street, they approached a large, ornate building. A palace? When he hesitated, the soldier behind him shoved a rifle in his back. Ted pulled himself up to his full height, raised his head, and marched up the stairs.

Another Mirosian sat at the end of the hall. Their King? Ted had heard of him. If so, he was the first male Ted had seen. Like the other Mirosians, he was tall and had a secondary pair of arms and large wings, but he was broader than the others, with an ornate structure atop his head that might have been a part of his body or could have been a crown. He also wore more ornate clothing and carried a ceremonial sword. If Ted had been armed, he could have struck a blow for human freedom, but he couldn���t end the sacrifices by killing the King. Another King would take his place.

Next to the King, a graceful young Mirosian female stood, wearing the robes of a priestess. She and the King murmured to one another.

Then the guard behind Ted said, “Prisoner of the Goddess, kneel!” She kicked Ted in the back of the knees, and they hit the stone floor. Pain radiated up his legs and he gasped.

All Ariane could think was how the prisoner was so fragile. All his insides on the outside, so exposed and vulnerable. And yet they kicked him in his unprotected joints. It was unkind, and she leaned over and whispered so to her father.

Father smiled at her and patted her hand. He turned back to the prisoner. “You will meet the Goddess the day after tomorrow. Until that point, we must feed you and give you rest.”

The human said nothing. One of the guards unshackled the human’s wrists, and he rubbed them.

They’d hurt him, Ariane thought. Surely the Mother wouldn’t want that. “Will She really eat him? He seems too soft.”

Father lifted a wing. “Humans are hard on the inside.”

The human watched her. She knew the Holy Mother had to eat, but it was cruel to feed her something sentient that hadn’t volunteered. Of course, her order ate no animal life at all, so perhaps she was projecting her feelings onto the Holy Mother. After all, the animals that fed the soldiers and the Mother didn’t want to be eaten, either.

A soldier offered the human a plate of food. He ignored it.

The human must be hungry after his long walk. Ariane walked to him and squatted in front of him, like she would before a child. The guards tensed, readying their weapons, but she ignored them. “Please eat. We don’t want you to suffer.”

The human stared at her, then looked away. He smelled like sweat and fear. Ariane sighed and walked back to her father.

“You shouldn’t have done that, Ariane,” her father said. “The creature is dangerous. It could hurt you.”

“He won’t hurt me, father,” she said. “He’s helpless and surrounded, and his species isn’t strong.”

Her father ran a finger along her eye ridge. “I fear the order has made you soft.”

Ariane pulled away. “May I return to my cloister?”

“Of course.” Her father sighed. “Be well, my child.”

Ariane left, walking towards the palace’s back entrance, approaching her order’s headquarters. She nodded to the guards who watched her enter the cloister. Inside, everything was calm and airy, smelling of bread, vegetables, and the Goddess. Ariane continued to the chapel, which was white and covered with statuary of the Goddess and God.

Bacran prayed inside. He smiled, mandibles sliding out, broad with genuine pleasure, and scooted sideways on the bench to make room for her, placing his ceremonial sword on the floor. “The mind of the Mother is such a calm place.”

Ariane nodded, and she knelt beside Bacran. Soon she felt the familiar ancient wisdom, the connection with all Mirosians, the peace and understanding that came from opening her heart to the Goddess.

The next morning, Ariane and Bacran were supposed to pray over the prisoner and help him attain a holy state of mind. As they left the cloister, Bacran murmured to her that he had never seen a prisoner in a mental state he would call holy. The volunteers, he added, would feed the Mother with joy in their hearts.

Bacran handed his sword to Ariane’s father for safekeeping before they started the ritual. They then pushed their way to the center of the armed guards, where the human waited, arms crossed over his chest. Ariane sprinkled the human with holy water while Bacran blew incense onto him. They sang the most beautiful prayer they knew, rubbing their wings for accompaniment. The music swelled and rose and echoed in the royal hall, the incense was an exquisite cloud of sweetness. The human curled his lip at it. Ariane���s father watched from his throne.

Bacran said, “Do you have anything to say before you meet the Goddess?” He said it in the alien language, and Ariane thought he said it quite well.

“As a matter of fact,” he said.

Bacran inclined his head to the human, and Ariane did the same.

“My name is Theodore Watson,” he said. “We didn’t know this planet was inhabited when we launched our sleeper ships. We don’t have the resources to go home.”

Poor things. Ariane imagined they’d leave if they could.

“We’re intelligent, sentient beings who don’t deserve to be treated like animals.”

“You sound so noble,” Ariane’s father said from behind them, “but you were the ones who attacked us.”

“We’d never met a intelligent non-humans before,” Ted said. “We were afraid.”

“You were xenophobic,” Ariane’s father said.

Bacran’s voice was quiet and gentle, yet firm. “There’s no need for accusations.”

“I’d never met an alien before yesterday,” Ariane said. “I can see how it would be frightening.” Both the human and Bacran stared at her. She stared at the floor until they stopped. “Are you hungry, Theodore Watson?”

“No,” he said.

“Were you finished with your statement?” Bacran asked.

“To kill one person is murder. To sacrifice someone to a God? We stopped doing that centuries ago. It’s barbaric.”

Ariane looked to Bacran’s serene face for reassurance.

Bacran’s voice was gentle when he asked, “How were you chosen for to be tribute to the Goddess?”

“Random chance,” the human said. “We drew lots. My friend Mike lost. He has a wife and kid, so I took his place.”

The Goddess wanted the best; it appeared She had received it.

“So you believe in the sacrifice of one to save the greater whole,” Bacran said.

“Yes,” the human said, “but as my choice.”

���Drawing lots is not choice,” Bacran said.

“We all took our chances.”

���So your friend is more equal than you are.”

The human set his jaw at Bacran, which Ariane assumed meant he was angry.

“I am merely pointing out that the situation is more complex than you are making it sound,” Bacran said. “I did not wish to give offense.”

“I can’t believe that a species that believes in human sacrifice is in a position to judge complex situations,” the human said.

“That is because your cultural biases blind you,” Bacran said.

Ariane asked, “Do you believe in a God?”

The human said, “I believe in one God, yes.”

“Only one?” Ariane asked. “Is God lonely?”

The human opened his mouth, then closed it. He stared at Ariane again. Finally, he said, “You’re strange.”

Ariane didn’t answer.

“I’m finished with my statement,” the human said.

Ariane started to pray again.

“You should eat something,” Bacran said.

“Fattening me up?” The human snorted. “No, thank you. I’d rather be stringy and tasteless.”

“Come, Ariane,” Bacran said. “We’re finished here.” He retrieved his sword from Ariane’s father and sheathed it.

“Ariane,” the human said. ���Pretty name.”

“Thank you, Theodore Watson.”

“Ted,” the human said.

Ariane inclined her head. “Ted.” Then she followed Bacran back to the cloister.

The skinny little priestess–Ariane–returned with yet another tray of food. Ted wished she’d go away. The tray smelled like fresh fruit, and his stomach growled.

“Please eat something, Ted,” she said. “We don’t want you to suffer.”

He wondered if it was possible to kill a God. Then he decided he needed his strength to put up a halfway decent fight. Whether or not he could win, he wanted to go down fighting. So he smiled at Ariane, took the tray, and said, “Just for you.”

She smiled back. It was the weird, bug-mouthed sideways smile of the Mirosians, but he’d pleased her. Interesting. Interesting and disturbing, since she had a mandible and smiling involved a lot of hinged motion.

He sat on the floor with the tray, which was piled high with fruits and vegetables. “I don’t suppose you have any meat?” Then he found himself hoping he wouldn’t be offered human meat, though he���d never heard of Mirosians eating humans… except for him.

“My order is vegetarian,” Ariane said.

Ted took a bite of something unfamiliar. He expected it to taste like apple, since it was round, but it was more like a carrot. “Our colony have these.”

“They’re not native,” Ariane said. “We brought them.”

“We brought plants and animals, too, but they’re not well adapted to this planet,” Ted said.

“Rhodots are rare,” Ariane said.

So they weren’t giving him any old garbage. Interesting. He wondered if the Mirosians thought they were honoring him by feeding him to a God. “Do you have any string?”

Ariane cocked her head at him.

“Never mind.” He picked up a stalk of something the humans called Mirosian Rhubarb, a native plant like orange celery but sweet. “This, we have,” he said, and he took a big bite.

She smiled again, and he ate in earnest. The rhodot wasn’t bad, once he got used to it. He finished everything on the tray and then handed it back.

Ariane inclined her head towards him and said, “Sleep well, Ted.” She started to stand.

Ted wanted her to stay. “Will you be in the order forever?”

She settled back on the ground. “I haven’t decided yet. Probably.”

“What do you do all day?”

She cocked her head at him. “We pray and commune with the Goddess. It keeps Her from getting lonely.”

“I don’t think our God gets lonely,” Ted said. “He’s everywhere all at once, and knows what everyone is thinking and doing.”

“Are you communicating with Him right now?” she asked.

“He knows what I’m thinking, but I don’t know what He’s thinking. So I suppose I’m just assuming that He’s not lonely.”

“So the communication only goes one way,” Ariane said. “I think your God is lonely.”

“You have two-way communication with your God?”

“Of course.” Her eyestalks shone. “You’ll see.”

So the Mirosians’ Goddess was going to talk to him before eating him? Ted didn’t like the sound of that.

Ariane picked up the tray and stood. “Do you need a blanket?”

“No, thank you.” What he really needed was a mattress or pillow.

“Sleep well, Ted.” Ariane turned and went back to her convent, or whatever it was.

Ariane liked Ted. She didn’t want him to be eaten. She walked past the guards, who saluted her, their wings ruffling air at her, and she took the tray to the kitchen. She handed it to the novices there and went up to the chapel to pray.

She had the sanctuary to herself and, when she opened her heart to the Goddess, she let the Goddess know the trouble that had settled there. The Goddess understood, but that didn’t make Ariane feel much better, because the Mother still needed to eat. Someday it would be Father’s turn to be eaten, but at least he got to be King first. Ted didn’t get anything but a couple of days of food.

Ariane felt from Mother that it was more than that, that Ted would be Her bridge to understanding humans and ending the conflict between them. Peace was good. That should make Ariane happy.

It didn’t. Bacran might be unruffled in the face of Ted’s sacrifice, but she wasn’t.

The Mother added that this would spare her father’s life for another generation. This comforted Ariane, but it was still unfair to Ted.

And then there was a hand on her shoulder, and she looked up to see Bacran. “Troubled?” he asked.

She nodded, and he knelt beside her. She felt him, too, at the edges of Mother’s consciousness, and his belief that all things change. She wished she had his self-assurance.

“Be careful, Ariane,” Bacran said. “He is not one of us, and you cannot know his heart. Not like you know ours. Humans live their whole lives trapped alone in their heads, and he can’t know your heart any more than you can know his.”

Ariane remembered her father saying that humans were hard on the inside.

Bacran nodded.

“His God is alone, with no one to talk to,” she said.

The Mother thought that Ted’s God must be insane.

“Don’t give him your heart, Ariane,” Bacran said. “You might not like what he does with it.”

When Ariane came back with his breakfast, Ted smiled and said, “How’s my favorite priestess this morning?”

She smiled the odd bug-smile again and slowed down.

He smiled back and asked, “What do you have for me this morning?” He sat up, stiff as hell from sleeping on the stone floor. His hips ached.

She handed him the tray. More fruits and vegetables, damn it. Raw fruits and vegetables. It might be worth getting eaten by a God just to get away from the boring food. But he wanted her to think he was pleased, so he said, “Yum, yum,” and took a bite of rhodot. It was fresh and crunchy.

“If you like the rhodots,” she said, “I could bring you more than one next time.”

“That’s very thoughtful of you,” Ted said.

She smiled again, and he started to wonder if she had a crush on him. That was ridiculous; she was an insect. On the other hand, Mike���-his friend–had told him stories about sheltered convent girls back on Earth. He’d seduced more than his fair share before his wife Mia stole his heart.

Ted shifted to a less sore part of his butt. “So, tell me about the Goddess.”

“She’s our Mother,” Ariane said. “We all come from her, and she watches over us and comforts us.”

“If she’s a Goddess, why does she have to eat?” Ted took another bite of rhodot.

Ariane tilted her head at him, and her antennae waved. “I don’t understand the question.”

Ted chewed, swallowed. “So she’s corporeal?” She didn’t answer, so he added, “Physical? She has a physical existence?”

“What else is there?” Ariane asked. “She’s not imaginary, if that’s what you’re asking. Is your God imaginary?”

Anger, white hot. Ted struggled to maintain composure. “No, He transcends physical reality.”

Ariane’s eye stalks moved closer together . “I don’t understand how anything can transcend reality. Reality is everything that is.”

“So your Gods are physical beings, like you and me? They’re mortal, and are born and die?” If so, they weren’t Gods, and he could kill them.

“The God dies and is reborn. The Goddess is eternal.”

So. Christ and the Virgin Mary, perhaps, although the Virgin Mary didn’t eat people. Interesting. “And yet she needs to eat.”

“I don’t understand why that surprises you,” Ariane said. “Although I suppose I should, since your God sounds so strange to me.”

“In what way?”

“Your God doesn’t need to eat, because He’s not physical, but He’s not imaginary and hears you but you can’t hear Him. If you can’t hear Him, how do you know He hears you?”

A small, traitorous voice pointed out that if God heard him, Ted wouldn’t be here. “It’s called faith. He wants us to believe in Him.”

Ariane’s antennae twitched. She stood and stepped backwards. “I’m sorry to have upset you. I’ll come back for your tray.” She started walking towards the door.

Ted sighed. “Wait. I’m sorry.”

Ariane stopped, She didn’t move at all for a long moment.

Ted needed information if he was going to defeat her Goddess. “Please don’t go. I like talking to you. We’ll talk about something else.”

Ariane came back, looking at the ground. She sat down on the floor next to his cell but didn’t say anything.

“I’m sorry,” Ted said, “I shouldn’t have snapped at you.”

She didn’t look at him. “Is there anything else you’d like for dinner?”

He’d kill for some meat. “No, thank you. You’re very kind.”

When she looked at him, her eyes were hurt and vulnerable. “Thank you.”

He reached between the bars and brushed the backs of his fingers across her cheek. It was hard, but smooth and silky. She flinched from his touch.

“Sorry,” he said. “I was curious. I’ve never touched a Mirosian before.” Well. Not willingly.

“Have you ever killed one?” she asked.

Six, all soldiers. “No. You?”

She laughed. “My order forbids me to kill. I cannot eat meat, or any whole plant.”

That explained the menu. “Not even a plant?”

She shook her head, smiling that odd Mirosian sideways smile. Ariane wasn’t what he expected. He’d been told that Mirosians were all cold-blooded killers.

It didn’t matter. Her people would feed him to a monster in the end.

“What else are you forbidden to do?” he asked.

“There is less that I am forbidden and more that I am required,” she said. “I must do penance if I am cruel, even if it is unintentional. I must help the poor; my order feeds and clothes them. I must pray twice a day, but usually do it more often. Mother’s voice is soothing.”

Ted felt a surge of envy. He’d love to hear the voice of God. He reassured himself that the Mirosian’s Goddess wasn’t God, and asked, “What about love?”

“I am supposed to love all beings,” Ariane said, “although sometimes it is difficult when they’re tired and grouchy.”

“I guess I was talking about romantic love,” Ted asked. “You know. Pair bonding.”

Ariane tilted her head at him. “You mean, as in reproduction?”

“Is that forbidden?”

“No,” she said

Ted finished his fruits and veggies and set down his tray. “Have you ever been in love?”

“Not in the way you mean,” Ariane said. “But Bacran is easy to love.”

“But not in the way I mean?” Ted smiled at her.

“No,” Ariane said.

She wasn’t looking at him. His questioning bothered her.

She picked up his tray. “It is time for prayer.”

Ted watched her leave, wondering if there was something she was hiding about love.

The next morning, the soldiers led Ted down stone stairs, below the palace and cloister. He expected the dungeon to smell musty, but it was clean. He was stiff and sore, and he resisted, but a Mirosian carried him the rest of the way down. At the bottom of the stairs was a large doorway, with a smaller door cut into it. They opened the smaller. He fought harder then–if they shot him, the Goddess didn’t eat–but they were stronger and shoved him through. The door slammed behind him.

The walls were smooth, and the only light came from a skylight. Ted looked around for something he could use as a weapon. He searched for a handhold, a foothold, some way to climb.

Now he had an almost blinding headache. Shaking his head, he continued to look for an exit. The sensation spread across the bottom of his head, and a gray blur expanded across his vision.

Ted shivered. Goosebumps covered his arms. He spun around, expecting someone inches behind him. Nothing. He looked back to the wall. The gray blur grew.

Curiosity. He wondered what he was curious about, until he realized he wasn’t the one who was curious. Ted leaned against the wall and said, “Get. Out.”

She didn’t get out. Instead, She moved closer, all of Miros behind Her, the bug hive-mind touching Her, not him. He had no secrets, no barriers, so instead he thought about how much he wanted to kill Her.

She was old and had seen hate before. She wasn’t impressed by his hate.

Ted found himself reviewing the defenses of the few free human colonies. Tears streamed down his face. He wished she would just kill him.

His altruism touched Her, but he didn’t want Her compassion. He wanted Her to hate him as much as he hated Her. She was truly a God, and She loved and accepted him in all of his alien flaws, and he hated Her for it.

There was a movement in the shadows then, and She showed herself, a giant figure in jade, the Mother, the Queen. Her mandible was the size of his torso. Her front claws could snap a cow in two.

Ted realized then why Ariane had been so bemused by questions of romantic love. Ariane, the daughter of the King–were they all children of the King?–was a worker bee.

No. Ariane was an attendant of the Queen.

The Mother came closer still. She was going to eat him now. An odd calm spread over him, and Ted realized it was Her. He fought, tried to be angry, hateful, defiant. But the Queen needed to eat. His flesh would nourish a new generation of Mirosians.

The door opened, but he couldn’t even move enough to see who opened it, let alone run.

“Let him go.” Ariane. “He doesn’t want to die.”

Everything dies.

Ted had wanted to die, just a moment ago, but he couldn’t remember why.

Ariane’s mind was a pure, bright flame, innocent and burning for truth and justice. Ted loved her then with all his heart, and the Mother did too. Then Ariane grabbed his hand and pulled him from the room.

He followed her, running down the street in a daze. The Mirosians around him were also dazed, uncertain, and Ted realized they knew his heart as surely as the Mother did. He loved them, all of them, but especially Ariane. She took him up a hill, far from the Mirosian city. He didn’t know how far they’d gone, how long they’d run, he just knew he should follow her.

Once over the hill, he was Ted again. Oh, God. She’d saved him, but what was he going to do with her? He couldn’t take her back with him. Humans would kill her.

He’d used her, tricked her, and even with telepathy she couldn’t see it. Ted shoved her away from him, and she tumbled down the hill. He didn’t look back.

What if she had seen his deception, and forgiven him?

Ted ran in the opposite direction. He’d lead an attack, humans would destroy the Queen, and they’d end this war by wiping out all the insects, starting with their Queen.

A deep whirring buzz sounded overhead. Ted looked up. Bacran dove, wings beating. And then the sword came, and Ted’s head bounced down the hill as his vision went dark.

Ariane wept at the bottom of the hill. How could Ted turn on her after seeing her heart? Poor humans, all alone in their heads. They were mad, just like their God was mad. And hard on the inside.

Bacran landed and knelt beside her. “Are you injured?”

Ariane shook her head. She managed to stand, despite the overwhelming smell of human blood. She was relieved when Bacran lifted her like he would a small child and carried her back to the city. A guard told her that her Father was dead, that he hadn’t said a word to anyone. He went downstairs and fed the Mother. It was time, and everyone knew it.

Ariane hungered, and the fruits no longer satisfied. When she started to grow, she knew the Mother had chosen her. Soon, Ariane would begin to lay.

She went to the chapel, and the Mother confirmed it. She would take Bacran, some of the sisters, and some of the guards, and she would start a colony where the Mother could protect them until her children grew. Humans reproduced so slowly that the Mirosians would soon outnumber them by a factor of hundreds, then thousands, especially if the Mother called more attendants to be Queens. No matter how mad the humans were, they would surely see the odds were against them, and the fighting would end.

Ariane didn’t want to take Bacran. He might become King. He was easy to love.

As she watched the towers being built, she mourned her father. She mourned the animals that died to feed her. She even mourned Ted. Soon, the time of mourning would be over, and the time of peace and new life would begin.

Want another short story? There���s one here.

August 12, 2024

Broad Universe Rapid Fire Reading

The reading went great! I got to read with my sister, and… generally if the Broads are in the house, GO SEE THEM.

I read from Immortal Gifts, and people chuckled in all the right places, so there you are.

July 30, 2024

Psst! Are you on Apple or Kobo?

Do you want to preorder a COOL BOOK?

Apple Books readers, click here!

Kobo readers, click here!

(It’ll be on other retailers as well. Stand by for more links, or join my mailing list!)

P.S. It’s also on Goodreads!

July 16, 2024

Grandfather Paradox

This story was originally published in Electric Velocipede, issue #17/18, Spring 2009, reprinted in Escape Pod, March 10, 2011, and reprinted in Love Stories.

JUNE 23, 1994

Ann stuffed her blood-spattered clothes into the next door apartment complex���s dumpster. He wasn���t dead, but it was harder to get a knife through someone���s chest than she���d expected. Maybe he���d bleed to death before someone found him. She didn���t care either way. She was a juvenile, so it wasn���t like she was going to fry.

She walked. The YMCA was open. She locked herself in the men���s room, curled up on the floor, and fell asleep.

The next morning, she stopped at an IHOP and told a grey-haired waitress, ���I don���t have any money, but can I have a cup of coffee?��� The waitress must have felt sorry for her: she bought her breakfast. Afterwards, she went to Safeway and hid a steak and a bottle of beer under her coat and walked out. And kept walking. Someone had a barbecue grill in their back yard. She took it, and the charcoal, too.

What she could really go for now was some mushrooms. She should swipe some Kool-Aid and find a cow pasture. Or maybe she could rob a veterinary clinic. Anything to get the thought of him touching her out of her head, and that beer wasn���t going to cut it.

Steak and beer. Almost luxurious.

The sign read ���Open House.��� Yes, that sounded about perfect. She spent the night there, on the carpet smelling faintly of shampoo.

It had happened to him, too. What her father had done to her, his father had done to him. Which, in her opinion, just made it worse. He knew what it was like.

When the police arrived and told her she was under arrest for murder, she couldn���t stop laughing.

JANUARY 4, 2014

The crane lifted the sealed concrete container out of the hole in the ground. Ann lay down in the snow next to the hole and reached inside. ���My arms are too short,��� she said.

Martin lay down next to her.

���Excuse me?��� Dr. Chandler, the president of the university, said.

���I���m sorry,��� Martin said. ���I thought my department chair had spoken to you. Martin Robbins, physics. My head programmer, Ann O���Connell. Please, continue.���

Dr. Chandler gave them a dirty look, then walked over to the microphone. ���This time capsule was sealed in 1914. The items inside represent what they wanted us to know about the past. I���m sure our history department is hoping I���ll cut the speech short and let them get at it������

There was a chuckle from the crowd.

���Got it,��� Martin said. He pulled out a grimy Tyvek envelope, and opened it. Inside, there was a penny dated 2013. Martin smiled at her. ���Looks like our own time capsule arrived intact.���

FEBRUARY 9, 2014

���How are you feeling today, Ann?��� Dr. Katz asked. Her glasses were perched precariously on her nose, and her bun was in danger of falling down.

Screw her. ���Is my hour up yet?���

���No.���

Fine. Be that way.

���How are things going with Martin?���

���I stopped dating Martin.���

���Why?���

���Because he wanted to sleep with me. It was awful. Ugh.���

Dr. Katz was giving Ann that psychiatrist look. Well, Ann had felt like she had to. Saying no would be rude. Well, not rude, but��� Anyway, no more Martin. She���d had her phone number changed, and if he came around again? Restraining order. Work the system, or the system works you.

���How does that affect your job?��� Dr. Katz asked.

���I have vacation time,��� Ann said. ���I took it.���

Dr. Katz looked like she felt sorry for her. Ann hated that.

Dr. Katz asked, ���Do you have any remorse over your father?���

���Do you think I should?��� Ann asked.

���I was asking you,��� she said. Crafty. Ann guessed that was why she paid her the big bucks.

���Is my hour up yet?���

���I know you���re tired of my asking you that, but you���ve never answered.���

Ann shrugged and looked away.

���Do you really think his dying made your life any better?���

No. Ann didn���t have to live with him any more, but it still happened.

Hmm. Maybe Dr. Katz was worth the money Ann paid her after all.

FEBRUARY 10, 2014

Martin looked skittish. Well, Ann supposed she didn���t blame him.

���I���m sorry I��� whatever it was I did,��� Martin said.

���It���s not you,��� Ann said, and smiled the most charming smile she could muster. ���It���s me.���

Martin just looked confused. Confused and skeptical.

���Can we take it slower?��� Ann said.

���You tell me,��� Martin said.

Ann looked away. ���How���s the project?���

Oh, he seemed so excited she���d asked. ���After the penny,��� he said, ���we tried animal subjects, but it���s a lot harder to confirm that those arrived safely. We think they did.���

Perfect. ���Will you show me the notes?���

Martin seemed to consider it. ���Well,��� he said. ���I suppose you do work here.���

NOVEMBER 11, 1955

Ann dropped her blood-spattered lab coat in an alley and hotwired the car. It was an older model, of course���perhaps she should say ���contemporary model��� instead���but those were easier. Billy Watson had taught her how to hotwire cars in exchange for a blow job. She���d promptly stolen his car.

Grandfather was in the phone book. They lived out in the suburbs.

Time to change a little history.

DECEMBER 25, 1988

Ann sat on the floor with her Raggedy Ann doll. Her grandmother was in the kitchen, cooking. Daddy was��� well, she wasn���t sure where he was.

���Ann? Sweetie?���

Ann looked up.

Ann���s grandmother was holding a sheet of cookies fresh out of the oven. ���Where���s your father?���

���Outside, I think.���

���Go and tell him Christmas dinner is ready.���

Ann put on her coat and gloves, and picked up her doll. She went outside, shutting the door behind her. ���Daddy?��� she said.

There was no answer, but there were footprints leading to the back yard, already filling up with snow. Daddy was lying in a snowdrift with a bottle, his eyes closed. He was covered in a light layer of snow, too, melting off his face, but clinging to his eyelashes.

���Daddy?���

He opened his eyes.

Ann didn���t know what to say. She thought she should know. She was nine years old, not a baby any more. But she stood there, clutching her doll and looking at him.

He sighed, and sat up, and said, ���What���s up, baby girl?���

���Dinner is ready,��� Ann said.

Daddy started to cry. He dried his eyes and wiped his nose on his sleeve, then took Ann���s hand and went into the house with her.

���You���re drunk,��� Grandmother said. ���Couldn���t you just behave yourself for one day?���

���He put his cigarettes out on my arm,��� Daddy said. ���Look!��� He tried to roll up his sleeve and failed.

Grandmother started to cry. Ann stood there in her coat and hugged her doll.

AUGUST 12, 1989

The car came to a stop in front of their house. ���Thank you for taking me, Mrs. King,��� Ann said.

���It was good having you with us,��� Mrs. King said. ���It���s a shame your father doesn���t take you camping more often.���

���He gets sick a lot,��� Ann said.

���I���ll wait here and make sure you get inside okay.���

Ann climbed out of the station wagon and retrieved her backpack. She walked up the sidewalk and unlocked the front door. She opened the door, and Mittens the cat rushed out. There was an awful smell.

Mittens cried, a mournful meow.

Ann stepped in, cautious, slow, walking towards���

She screamed, and ran out the door. Mrs. King was starting to drive away. She chased the station wagon, and Mrs. King stopped. She climbed in.

���Drive,��� Ann said.

���What���s the matter, Ann?���

���Wait! I want Mittens!���

���Ann?���

���Wait!��� Ann opened the car door and picked up the cat, then got back in and shut the door.

Mrs. King just looked at her.

���He���s dead,��� Ann said, and started to cry.

FEBRUARY 9, 2014

���If I could give my father one gift,��� Ann told Dr. Katz, ���I would give him a happy childhood.���

She wasn���t a detective, but she wanted to solve her grandfather���s murder. She���d read all the newspaper accounts. If it wasn���t for grandfather���s murder, Daddy would still be alive.

���Maybe we should talk about the abortion,��� Dr. Katz said.

���I panicked,��� Ann said. ���I just don���t think I���m psychologically healthy enough to be a parent.���

���And Martin?���

���We���re getting a divorce.���

���How does that affect your job?���

���It���s a bit uncomfortable,��� Ann said. ���But it���s not like we aren���t professionals.���

Ann had been afraid for a moment that Martin would change the access codes, but that was silly. She was divorcing, not fired, and the wheels of academe turn slowly.

Maybe she could set things right, once and for all. She wasn���t sure what would happen to her, but maybe she could make things right for Daddy.

NOVEMBER 11, 1955

Ann sold her engagement ring and bought a car. Finding the house was easy; she���d lived there after Daddy died.

Grandmother was a tired-looking woman on the front porch with a black eye. ���Don���t remarry,��� Ann said.

���I beg your pardon?��� Grandmother said.

Ann���s timing must have been off, because the man who came to the front door wasn���t her step-grandfather.

���Remarry?��� he said. ���Who are you?���

���A friend,��� Ann said.

���Eileen ain���t got no friends,��� he said. ���Get off my porch.���

Grandmother looked scared, so she did. She headed down to the edge of the property.

That���s where Ann saw her. Herself. Whoever. If this whole time-travel thing became common, the linguistics people were going to have a problem. She didn���t know how this was possible, but she supposed time-travel was really Martin���s area. Although she suspected he���d be unsettled to meet himself, too.

���Fancy meeting you here, doppelganger,��� the other Ann said. ���Guess I didn���t quite get this one right.���

There were raised voices coming from the house. Grandmother screamed.

���If she loses the baby, we���re both done for,��� Ann said.

���We can take him,��� the other Ann said. ���The two of us? No problem.���

���What?���

The other Ann gave her a scornful look. ���You���re not scared of him, are you? The things father did to us, he did to father first. He deserves to die.��� She beckoned. ���Come on. We���ll get it over with.���

���You think I came here to kill him?���

���You didn���t?��� the other Ann said. ���Why did you come?���

NOVEMBER 11, 1955

Ann hated her doppelganger.

Ann shouldn���t hate her doppelganger. She made her. She was her: the Ann she wanted to be, the Ann she created by coming back to kill Grandfather. She thought she���d love her, but no, seeing her, she was so full of hate and envy her throat was full and she couldn���t breathe.

If she was going to kill for her, shouldn���t she love her?

���Apparently,��� her doppelganger said, sitting on the ground, ���Grandmother has no taste. Her next husband was a bastard, too.���

Damn. Ann had never thought of that. ���Well,��� she said, ���we can���t have a long line of us coming back in time to kill her husbands, can we?

Doppelganger Ann laughed a little. ���No. Maybe if we called Child Protective Services������

���I don���t think they have Child Protective Services yet.���

���The police?���

���For an unborn child?��� Which meant that they couldn���t just cut to the chase and kill Grandmother, unfortunately.

���What are we going to do, then?���

���I can���t not kill Grandfather,��� Ann said, sitting on the ground next to her. ���You���ll cease to exist if I don���t.���

���I don���t want you to kill anyone,��� the doppelganger said.

���We���re all born of original sin,��� Ann said. ���Except you. You were born of my sin.���

Somehow Ann didn���t think that was what her doppelganger wanted to hear. ���There���s more than just cause and effect going on here,��� the doppelganger said. ���Ethos anthropos daimon. Character is fate. Maybe if we changed Grandmother somehow.���

Apparently, they���d taken similar coursework in college. ���Character is created by cause and effect,��� Ann said.

The doppelganger shook her head. ���No. I have no control over the things that happened to me, but I can control how I react to them. That���s character.���

���You may have free will,��� Ann said, ���but not me. I am a product of causal determinism.���

���Don���t be such a fatalist.���

���You know,��� Ann said, ���we can argue free will all day, but right now, I have a child molester to kill. What say we continue this philosophical discussion later, over wine and cheese?���

���But this impacts whether what you do makes any difference!���

���Either way,��� Ann said, ���I���m performing a service to society, and I suggest you not interfere.���

���But he hasn���t done anything yet!���

���How do you know?��� Ann stood.

Her doppelganger stood, too. ���I can���t let you do this.���

���I���ll say it again: stay out of my way.���

At least her doppelganger seemed to have the wit to be scared. She stood aside, and Ann went back into the house. Grandmother was weeping at the foot of the stairs. Grandmother started when she saw her, but Ann put a finger over her lips and mouthed, ���Gun.���

Grandmother looked at Ann like she was her savior, and pointed at the back door. There was a shotgun next to it. Ann picked it up and started up the stairs, moving as quietly as she could.

He was lying on the bed, looking at the ceiling. He saw her peering around the corner. ���What the hell do you want?��� he asked. ���How did you���?���

She pointed the shotgun at him. ���I know what you are. I know what you���re going to do to Eileen���s child.���

He sat up and stared, looking terrified.

���It happened to you, too, didn���t it?���

���I don���t know what you���re talking about.���

���Wrong answer,��� she said, and pulled the trigger. It went straight through his heart, which was probably an easier death than he deserved, but in a sense he was a victim, too. What happened to her happened to him. But what happened to her happened because of him, because of what he did, because of what happened to him.

Stop the cycle. I want to get off.

NOVEMBER 11, 1955

Grandmother looked at her so strangely when she came in the front door, but otherwise she took a second Ann surprisingly well. ���I���m not her,? Ann said.

Grandmother looked up the stairs, then raised an eyebrow at Ann.

She probably only had a moment. ���Listen to me,��� Ann said. ���No matter how nice he seems, don���t marry the investigating officer.���

���How will I support my child if I don���t remarry?���

���Can you move back in with your parents?���

���I wouldn���t raise a child in my father���s house,��� she said.

Oh.

There was a gunshot upstairs.

���Don���t touch the gun,��� Ann said. ���It���ll have her fingerprints on it. Say it was a strange woman, say you think your husband was having an affair with her, they���ll believe you.��� After all, it worked the first time.

���Who are you?��� she said.

���We���re your granddaughter,��� Ann said. Grandmother seemed to take that better than Ann expected.

The other Ann came barreling down the stairs. ���Time to go, doppelganger.��� She looked at Grandmother. ���Don���t touch the gun. Call the police.���

Grandmother nodded.

���Don���t forget what I told you to tell them,��� Ann said. ���They���ll never believe the truth.���

���I don���t think I believe the truth,��� she said.

NOVEMBER 11, 1955

They ducked under a bridge. ���Well, this sucks,��� the other Ann said.

���What?���

���I was hoping that I would cease to exist at this point,��� she said. ���I guess it doesn���t work that way.���

Ann heard a car come to a stop on the bridge over them, and ducked under a bush into the mud. She heard the other Ann make a disgusted noise, and the car doors opened, followed by the sound of footsteps.

���Come out with your hands up,��� a voice said. ���This is the police. You���re under arrest for the murder of Charles O���Connell.���

The other Ann started to laugh.

JANUARY 19, 1956

Grandmother brought a date to the trial, a good-looking older guy who appeared to have money. Ann didn���t like the way he kept his hand on her back. Possessive. Like he owned her. On the other hand, there were only two Anns running around so far, which might be a good sign.

The other Ann pled guilty and suggested the death penalty. The judge looked disturbed by that and sentenced her to life in prison.

Ann found herself thinking of Martin. She supposed that it didn���t matter what she did now. Unless, of course, she wanted to steal her father from her grandmother and raise him herself. She still didn���t think she���d make a great parent, although she figured she couldn���t do that much worse than grandmother. But she���d had her chance, and she���d aborted it. So she bought herself a big bottle of vodka, and found herself a nice snowdrift to drink it in.

JANUARY 4, 2014

The crane lifted the sealed concrete container out of the hole in the ground. Martin lay down in the snow next to the hole and reached inside. Ann stood next to him, her hand resting on her pregnant belly.

Martin pulled out a grimy Tyvek envelope. ���Got it!��� he said.

Ann threw her arms around his neck and kissed him.

Want another short story? There’s one here.

July 15, 2024

Broad Universe Rapid-Fire Reading

Are you going to WorldCon in Glasgow? You can SEE ME there!

August 11, 2024 at 4pmBroad Universe Rapid Fire Reading – Castle 2Meet the Broads of Broad Universe! The authors of Broad Universe will drop you into their fictional universes with short readings from multiple authors and works. Within the session you will hear a variety of writers in a variety of speculative fiction subgenres, like a variety box of chocolate! Broad Universe is an international organization dedicated to promoting women and traditionally marginalized genders in Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror.

Prospective Participants: D. H. Timpko, E. C. Ambrose, Jo Miles, Katherine Villyard, Kathryn Sullivan, Randee Dawn, Cynthia Villyard

June 27, 2024

The Interview with the Vampire TV Series

OH MY $DEITY I AM OBSESSED.

So, I’m a book fan–not a “True Fan,” as I read the first three and stopped–but I read and loved the first three books very much. (I recently read Tale of the Body Thief as well and enjoyed it!) But it’s as someone who read these books at an impressionable age that I come to the series.

Pros:

There is no subtext, only text. BRING ON THE GAY!I love the changes to the time period and ethnicity of the vampires. As I said in my vampire post, BRING ON THE SYMPATHETIC BLACK VAMPIRES. There were racist cartoons in the post-Civil-War south depicting Black men as vampires, and I feel that the best way to defang (pun intended) that narrative is to make them the heroes. It has a very Anne Rice “feel.”Cons:

Basically, I don’t agree with some of the character choices. They gave a lot of Lestat’s character notes to Louis to make Lestat more antagonistic, for example. I mean. Lestat is the antagonist of Interview with the Vampire. Armand is the antagonist of The Vampire Lestat. And they’re doing a lot of “memory is a monster” unreliable narrator fun. But there are some Lestat would never moments.Sometimes I’m uncertain about internal consistency, but also “memory is a monster” and they are approaching Rashomon levels of different narratives here.In short, I might set my alarm for 3am Sunday to watch the finale, and am waiting anxiously for season 3!

As you were.

June 15, 2024

La Divinia Commedia

This story originally appeared in ChiZine, October 2011, and was reprinted in Broad Spectrum: The 2012 Broad Universe Fiction Sampler (October 30, 2012, and in Love Stories.

INFERNO

Last time this happened, I was Orpheus.

Ethan was lost, pale, gone in a haze of Zoloft and Lithium and anorexia, and he assured me he was in hell, and I missed him so much that the rocks and trees wept. And when neither of us could bear it any more, I descended into the underworld and went to the King. I sang such a song of grief that I even moved the King of the Underworld to tears, and he said I could bring my Eurydice back to the light of day if only I didn’t turn back and look upon him. As I walked through the fluorescent halls and the smell of bleach and urine I knew this was hell, and I couldn’t bear the thought of my beloved locked away from the sun like this forever. So I led the way singing, and the janitors and nurses wept and cleared a path for us as we walked down the hall.

As I opened the front door, I turned. Ethan had a tic and couldn’t stop moving his left arm. He threw his right arm over his eyes and screamed that my hair was on fire. Maybe I should lay off the henna. And then he was gone, vanished back into the underworld like smoke, and I was alone.

Apparently, being Orpheus doesn’t work.

I don’t imagine you would want to be my Eurydice anyway, my darling. I think you think of yourself more as a Lancelot, all shining armor and devotion to your lady fair. But there are no stories of Lancelot in the underworld, at least not that I know of. Lancelot was from the wrong part of the world for Dante’s attention.

Perhaps I should be Inanna instead. I like that. Inanna is sexy. It fits in a way, you and I have a lot more spark than Ethan and I ever did.

So I come and join you in the underworld, my love. I don’t see how this has happened again, and this time, since I am not Orpheus, they won’t let me in as a visitor. So I come in the only way I can. At the first gate, they take my purse. At the second, they take my jewelry. At the third, they take my shoes. By the seventh gate, I’m wearing a simple shift, like an inmate. The rituals of the dead are ancient and cannot be questioned.

Your eyes when you see me are worth it. Before I know it, you’re in my arms again, at last. You’re warm and lucid, with hot lips and roaming hands. You’re like the sun. You warm all the parts of me that are cold, clear to the bone, and you make me feel like the Queen of Heaven. I’m looking out of the corner of my eye for a relatively private place to take you when dull, bored men in white tell us we aren’t allowed to kiss and separate us.

The doctor is a woman with cold, dark eyes; she calls me words like “sick” and “codependent.” I expect this. Inanna is a corpse in the underworld for three days.

I would suffer to get you back, but in those three days your eyes are cold, lifeless, dark. We are corpses together, my love, locked away from the sun. Inanna and Damuzi, together in hell. It’s not the Christian hell; it’s cold and dark, full of the dead and the smell of industrial cleaner and the metallic tang of what passes for our food, and we all rot together.

After three days, I smell. Not as badly as I would if I were truly a corpse, but my hair is stringy and sweaty and my eyes are sunken. When I lay my hand on your shoulder and say, “I did it for you,” you turn.

“This isn’t your story!” you say. Your voice is so loud, your face so red, you turn so quickly that I think for a moment that you might strike me, and in that moment I decide that Doctor Ereshkigal is right. I shouldn’t be here.

“You’re right,” I say to you, and tell the Doctor, “Keep him.” I turn on my heel and check myself out, feeling like I have condemned you to hell in my place, and think that I may never love again.

PURGATORIO

The world has gone grey, like a monastery.

“I just have some issues I need to work on,” you tell me. You’ve lost weight, your color is bad and your eyes are haunted. You avoid looking me in the eye, like you’re afraid I’ll see through you, see into your heart.

I don’t feel like Inanna any more. I don’t feel sexy. I’m tired and my heart aches from seeing you suffer. I feel like Mary in the Pieta, only Mary was lucky enough to hold what was left of her beloved son and weep over him. But you’re not my son. You’re my lover, despite the way you’re avoiding touching me.

In lieu of hugging you, I say, “I know, sweetheart.”

“I just, I didn’t get this way overnight, and I’m not going to get better overnight. I’m a work in progress.” Your voice breaks, like you might burst into tears at any moment.

I want to cry. I want to wrap you up in a blanket and feed you soup. “I baked you cookies,” I say.

“I don’t deserve cookies,” you say.

I want to grab you and shake you for being such a fucking drama queen. Shake you until your teeth rattle. But it’s no use; this is your story, and forgive me, darling, but you’re not the storyteller I am. One note, like plainsong. Pie Jesu Domine, dona eis requiem.

You’re neither a monk nor an ascetic. I shove the bag of cookies into your hands and brush your hair out of your eyes.

You shudder away from my touch and almost drop the cookies. “I’m not allowed to eat sweets. I have to eat complex carbohydrates, like brown rice.” You hand the bag of cookies back.

I grit my teeth and force my voice into patience. “You’re not going to tell me what’s wrong?”

You shake your head, a bit too vigorously. It’s a little frightening in your fragile state. You look like you might snap in half. “I can’t. I want to, it would be such a relief, but I can’t. I just��� I need to work on some issues.”

“Okay,” I say. “I love you. Feel better.”

And then you start to cry. Dona nobis pacem.

PARADISO

I don’t have a happy ending for you. I suppose this is still your story, and you’ll have to make your own happy ending.

But I have a story, too. I am Persephone, back from the dead. My mother and I go to the botanical gardens and admire the roses together, and I can’t remember the last time I’ve seen her so happy.

There are butterflies, and greenhouses full of orchids and cacti, and so many flowers. I reach up and run my fingers over the roses, petals like velvet. Soft, yielding. Sensuous. It’s been too long since I’ve taken a lover, but I’ve shed old Mary’s robes in favor of a gauzy dress and sandals.

Unlike Persephone, I don’t intend to go back to you in the underworld. If you want me, you’re going to have to come out of the underworld yourself and get me. Not like Hades with his dark chariot, like Dante. Like someone who doesn’t plan to go back. I don’t care how. Hell, you be Inanna for a change. Damuzi was the Sumerian Persephone, after all.

I don’t care what story you pick. You’re the author of your own story, after all. Just pick one.

When I see you coming out of the tunnel you’re blinking, like you haven’t seen the sun in a long time. “I am Lazarus, come from the dead, come back to tell you all, I shall tell you all.”

My mother stiffens at the sight of you, and this odd speech of yours makes her shiver. But this is a story I know.

I hand you a peach. “We should go walking at the beach.”

You look at the peach for a while, like it’s going to bite you. Finally, you bite it, and, like Persephone in reverse, I feel it trap you in the here and now. We go to the beach, where you take off your shoes and roll up your jeans. I take off my sandals. The sand is hot. The water is salty cool and stings a little where my sandal rubbed my foot wrong. We talk about what it would be like if there really were mermaids, if we could hear them singing, each to each, and agree that they would not sing to us. With each step, you become more solid and real. With each bite of peach, you become less Hades and more J. Alfred Prufrock.

I’d like to say we live happily ever after, but this isn’t that kind of story, is it?

Want another short story? There’s one here.