Kristin Rix's Blog

May 16, 2017

Book Review: Aurora by Kim Stanley Robinson

Aurora by Kim Stanley Robinson is the first novel I’ve read by this author. I read one of his short stories in an all-sci-fi issue of Wired magazine and loved it, plus I’d heard all the (positive) commotion about his novel New York 2140. So I was excited to dive in. I recently graduated college and immediately after (well honestly about a week before, I was really excited) went to the bookstore and bought a stack of science fiction to read. This is the first time in a very long time that I’m actually able to read books *I* want to read. Anyway, Robinson was at the top of my list of new authors I want to check out, and I decided to start with Aurora. I was not disappointed.

Aurora is about a group of people on a spaceship about to arrive at their new home, a planet called Aurora in the Tau Ceti system. The voyage was begun many generations ago by people who eventually died of old age without seeing the end of their adventure. It’s a bittersweet start, in part because I couldn’t help but mourn the lives of the people who were in the middle generation. They didn’t get the excitement of starting out, and they didn’t get the excitement of getting there.

Robinson has put a lot of thought into the science of his work, and it seems that while he is perfectly capable of letting his imagination run wild with possibility, he is also able to rein in that imagination with a cold hard look at the science of the thing. It’s very practical science fiction, focused on the human condition and its role in the universe we’ve created for ourselves. The drama and conflict here does not involve epic space battles or Alien-level monsters. The battles are of our own making, the monsters sometimes in the mirror.

And that is what I think makes Aurora such a chilling read: it is so plausible because it’s rooted in a deep understanding of humanity. Robinson looks at who we are and where we seem to be going, and crafts his space opera around those two quantities. Then he backs it up with science.

This book did a great job of making me see our planet in new and interesting ways, and ask important questions of myself, especially in the use of a poem at the end which I won’t relay. I don’t want to give anything away. But that’s exactly the kind of science fiction I love best. It’s moving, it has a feeing of being bigger than all of us, and it makes me reflect on big questions. Those are the kinds of stories that have shaped me since I first started reading science fiction, and what I strive for in my own writing.

So, if you’re looking for a big action adventure, this is probably not your book. But if you like well-thought-out science, deep character development, and big questions, Aurora is a winner.

Related articles

[image error] After the Flood: Author Kim Stanley Robinson Describes Future NYC Underwater

[image error] The Best Sci-Fi Comedies You’ve Never Seen

The post Book Review: Aurora by Kim Stanley Robinson appeared first on Kristin Rix.

December 2, 2013

Dramatic Division

– Advertisement –

// ]]>

–

Dramatic Division: An Analysis of the 3- and 5-act Structure of Dramatic Writing

Introduction

IntroductionResearch into the difference between 3- and 5-act play structures is very difficult. Few books address this topic directly unless they are dealing with scriptwriting, though I believe it to be a topic of great interest to the budding writer of all forms: fiction, nonfiction, drama, screen, and even poetry. What are the different structures? they ask. Why choose one or the other? Why have structure at all? How can I use the theory of structure to aid me in my writing? Indeed, as I mature as a writer I’m indelibly drawn to these same questions. It is my belief that few books go in-depth into this question because the form was established so long ago by Aristotle. Any who wished to approach the task of dramatic writing assumed that structure and moved on with the business of getting the play written. Jackson G. Barry, in his book Dramatic Structure, is ambivalent about act division, and believes the division of acts to be an afterthought, something that is either “purely conventional or organic and, in either case, its dictated divisions may or may not be physically marked for an audience at the playhouse” (Barry 86). Act division is, he says, “certainly conventional, the product of historical precedent” (Barry 86).

When it is discussed, it is done so only briefly, usually a brief chapter somewhere between scene and plot. I am always baffled by this, because the number of acts and the way they are structured seems to me to be the first choice a writer would make about their work. If you have ten items you need to place in a box, wouldn’t you want to pick the right box for your items? Would the type of box affect the order in which you place your items? Perhaps it is a more personal aspect of approach by an individual writer, but I am of the mind that knowing the major structure of my work at the beginning of writing is beneficial in crafting scene structure.

Screenwriters have since figured this out, and many screenwriting books address the topic directly. This is perhaps due to the close connection between a successful screenplay and the bottom line for movie production companies. There is little deviance and experimentation because production companies are more interested in earning money than they are setting new standards of dramatic structure. Therefore, writers who attempt screenplays begin with the dramatic structure that is most often used in film: 3 acts.

The 3-act structure has begun to pervade fiction writing courses as well. The pattern of crisis, climax, and resolution that is characteristic of a 3-act structure is one that is being used by fiction writers in order to capitalize on the tension that it builds in the reader. This crisis, climax, resolution concept has been likened by some feminist theorists to the sexual climax of men, and claim that the pervasiveness of the 3-act structure is representative of the oppression of the feminist perspective.

Regardless of one’s opinion on the 3-act structure, there is little argument that it is the most popular structural form in modern dramatic writing. However, plays can be written in any number of acts the author chooses. Some plays have only 1 act, while others have none at all. It is my concern that the limited amount of information, and the one-sided approach that scriptwriting takes, is a failure for the future of dramatic writing, and writing in general.

Is an “act” merely a division of convenience to aid the readers and theorists in their discussion? Or is it something more fundamental in the way we tell our stories? Is the act fundamental and necessary to our experience of the dramatic arts? It is precisely these questions I hope to answer by taking a closer look at both the 3- and 5-act dramatic structures.

Literature Review

Poetics by Aristotle, Joe Sachs trans. Originally published in 335 BC.

The Art of Poetry by Horace Originally published in 18 BC.

Techniques of the Drama by Gustav Freytag, Elias J. MacEwan trans. Originally published in 1863.

A Doll House by Henrik Ibsen, Rolf Fjelde trans. Originally published in

Hamlet by William Shakespeare

The 3-Act Structure

The 3-act structure is by some accounts the oldest form of drama there is. The definition of the 3-act structure is often attributed to Aristotle. In his treatise on drama, The Poetics, he writes,

A whole is that which has a beginning, middle, and end: a beginning is that which is not itself necessarily after anything else, but after which it is natural for another thing to be or come to be; an end is the opposite, something that is itself naturally after something else, either necessarily or for the most part, with no other thing naturally after it; and a middle is that which is itself both after something else and has another thing after it. Therefore, well-organized stories must neither begin from wherever they may happen to nor end where they may happen to, but must have the look that has been described (Aristotle 30).

Thus he is describing the essential nature of the three acts: the beginning (crisis), middle (conflict), and end (resolution).

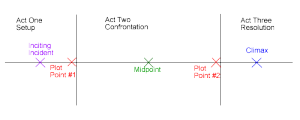

Examining the screenwriting industry is a good way to get a grasp on the nature of dramatic structure. Syd Field, one of the most highly respected authors on the topic of screenwriting, says in The Screenwriter’s Workbook that “a thorough knowledge and understand of structure [is] essential in the writing of a screenplay” (27). As said earlier, the 3-act structure is most prolifically discussed with regards to screenwriting, which has established for itself a very definite formula with which most film scripts are written. Though of course films can go outside this structure, it has proven to be a successful technique for many films. Screenwriting manuals even go so far as to time out the events. Field, for example, outlines what he calls the screenwriting “paradigm” (Field 40). If a movie is one hundred twenty minutes, and therefore roughly one hundred twenty pages long, act one would comprise one quarter, or thirty pages, of the script, act two would comprise one half, or sixty pages of the script, and act three would comprise the final quarter of thirty pages. A further analysis of the structure of screenwriting sheds light on the elements of each act (fig 1).

Figure 1 – The 3-Act Structure in Screenwriting (Pruter)

Figure 1 – The 3-Act Structure in Screenwriting (Pruter)Act 1 is traditionally considered to be the setup. It is in Act 1 that we meet the protagonist, develop a sense of the story context, and learn about the central problem of the

story. Act 1 also contains the “Inciting Incident”, the event which causes the initial problem, or the “call to adventure” (51) as described by Joseph Campbell in his book The Hero With a Thousand Faces. This is the event that gets it all going. Though these structural definitions come from a manual on screenwriting, we can look at A Doll House by Henrik Ibsen, a 3-act play, to see how its structure coincides with these concepts. In Act 1 we meet Nora, the protagonist of the play. We learn of her character as a lighthearted and frivolous woman, and of her context as a wife to wealthy bank manager Torvald Helmer. The inciting incident is, when Krogstad appears at the Helmer household to complicate Nora’s life.

Plot Point #1 is the moment in Act 1 where the protagonist has decided to accept the call to adventure and face the challenges ahead, and signals the transition to Act 2. In Doll House this is the moment where Nora realizes that she cannot simply talk Torvald into doing what Krogstad wants. She cannot reveal her situation to her husband because of his intense distaste for dishonesty. Her situation is truly desperate, and as she realizes this she also realizes that she will do anything to find a way out of her predicament.

Act 2 is often labeled “confrontation” because the majority of this act tends to deal with complications and confrontations for the protagonist. In screenwriting, the midpoint is the culmination of

these complications, the moment in which the protagonist loses hope. It is the central even that everything leads up to, and that everything is a result of. Again, if we look at A Doll House, we can consider the midpoint moment to be when Krogstad places the letter in the mailbox. The letter is then the subject of much concern and conjecture, of planning and scheming, and represents a loss of hope for Nora since she cannot get to it without alerting her husband to her troubling situation.

Plot Point #2 is the transition from Act 2 to Act 3. It takes all the confrontation and turns it into the final climb up to the climax of the story. In A Doll House, Nora has managed to distract her husband from opening the letter box, but she knows it’s only a matter of time until he does and her world falls apart. He’s agreed to wait until the following evening, and in doing so seals her fate and the time she thinks she still has to live.

Finally, Act 3 is the resolution. The climax of the story is culmination of all the tension and complication the protagonist has experienced. Finally, once the climax has occurred, there is often a falling action, or denouement. In A Doll House, the climax is when Torvald finally reads the letter and knows what his wife has kept from him. It is a revelation for Torvald, but it is also a revelation for Nora and is the culmination of her character arc, the line of change that can be traced for her throughout the play. Once she has experienced her revelation, the story falls into its denouement. Nora decides to leave, and does.

Some critics of the 3-act structure claim that it reflects the domination of western culture and civilization by the male perspective. As Edwin Wilson notes in his introductory theater textbook The Theater Experience, radical feminist theorists “saw the plot complications, crisis, and denouement in tragedy as a duplication of the male sexual experience of foreplay, around and climax” (Wilson 166). In response, feminists have called for a dramatic form “that stressed ‘contiguity,’ a form…which is ‘fragmentary rather than whole’ and ‘interrupted rather than complete.’ This form is often cyclical and without a single climax” (Wilson 166). Though Wilson notes that not all feminists embrace this definition of new dramatic structure, it is clear that they are taking the opportunity to experiment with finding their own structure and form.

The 5-Act Structure

Gustav Freytag is credited with defining the 5-act structure of dramatic writing. However, the 5-act structure has been used by playwrights for a very long time. The Roman philosopher Horace, who lived from 65 BC to 8 BC, first proposed the 5-act structure in his Ars Poetica, or The Art of Poetry, when he says, “A play which is to be in demand and, after production, to be revived, should consist of five acts—no more, no less” (Dukore 71). The dissemination of this work throughout Europe led to a revival of this structure format by Renaissance playwrights. Shakespeare wrote all of his plays in 5 acts.

Fig 2 – Freytag’s 5-act Structure

Fig 2 – Freytag’s 5-act StructureFreytag, a German novelist and critic of the nineteenth century, observed pattern of structure and plot in a variety of plays throughout history. In this way, he was able to identify the elements that made up each of the 5 acts of a play (fig 2). He called these a) introduction, b) rising action, c) climax, d) return or falling action, and e) catastrophe. Each act is separated by what he calls a stirring action, “through which the parts are separated as well as bound together” (Freytag 115). They are the moments which transition the dramatic action from Act to Act.

In Act 1, introduction, of course, introduces the audience to the context of the play and to the main characters. In ancient plays this was often done in a prologue. In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, we are of course introduced to Hamlet and his father’s ghost, thus setting the stage, and tone, for the action to follow.

In Act 2, the rising movement, Freytag writes that, “the action has been started; the chief persons have shown what they are; the interest has been awakened” (125). In Hamlet, Polonius and the King notice Hamlet’s despair but fail to properly diagnose it. Instead they contrive ways of finding out his ills that cause complications for everyone, especially poor Ophelia.

In Act 3, the climax of the story is the greatest moment of tension. The climax is the turning point and this third arc effects a change either for the better or for the worse in the protagonist’s situation. In act 3 of Hamlet, the players act out their play as Hamlet watches the reaction of his mother and uncle. Hamlet then has an opportunity to kill his uncle but waits. He then confronts his mother but notices someone hiding behind the curtain. After he stabs the figure, he discovers he has murdered Polonius. He must now leave.

In Act 4, the falling action begins. Now that the climax has occurred, the characters must deal with the consequences. Hamlet must dispose of Polonius’s corpse. The King must address his court and send Hamlet away. Ophelia has gone insane and her brother Laertes demands justice for the wrongs done to his family. Finally, Ophelia takes her own life.

In Act 5, the denouement signals the end, and all things are resolved. For Hamlet this means that all interested parties take part in one final scene where everyone ends up dead.

Analysis

The exposition of Act 1 in a 5-act structure is, of course, the “setup” seen in Act 1 of the 3-act structure. It sets the scene and introduces the protagonist. The stirring action that exists between Act 1 (exposition) and Act 2 (rising action) is the “inciting incident.” It is the protagonist’s response to this stirring action that causes the rising action.

One clear difference between the 5-act and 3-act structure is the location of the climax. In the 3-act structure, for example, Hamlet’s play-within-a-play would be the midpoint, the moment in which all is lost for Hamlet. Everything would lead up to the fight scene, which would be the climax. It is interesting that Freytag does not consider this to be the climax of the play. To a modern mind, the action and finality of Act 5 seem to make it very climactic, with little to no denouement. It is a new perspective on the importance of certain elements in Hamlet that, for me, give it a new light.

Conclusion

Ultimately there are far more similarities than differences between the 3-act and 5-act structure. It seems to come down to a matter of language more than anything inherent in the structure itself. Freytag’s definition of the 5 acts is very similar to the present understanding of the 3 acts, especially in terms of the philosophy of screenwriting.

It is interesting to note that Ibsen abandoned the prevalent 5-act structure in favor of experimentation with 3 acts. It is perhaps the extensive influence his work has had on the modern dramatic arts that has led to the present-day approach to the 3-act format, and why his play The Doll House can so easily be analyzed against our present understanding of that structure.

I believe that a thorough understanding of each method is important to understanding the dominant method of story structure for the last several thousand years—really for as long as we have been recording poetics and our ideas about them. Is the 3-act structure better or worse than the 5-act structure? No. Is it crucial that the chosen structure be made apparent to the reader or audience? Not really. The true benefit of knowing and using these structures is the development of a compelling storyline that will resonate with its intended audience.

Works Cited

Aristotle. Poetics. Trans. Joe Sachs. Newburyport: Focus, 2011. Print.

Barry, Jackson G. Dramatic Structure. Berkley: University of California Press, 1970. Print.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973. Print.

Dukore, Bernard F. Dramatic Theory and Criticism. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1974. Print.

Field, Syd. The Screenwriter’s Workbook. New York: Bantam Dell, 2006. Print.

Freytag, Gustav. Technique of the Drama. Trans. Elias J MacEwan. New York: Benjamin Blomm, 1968. Print.

Ibsen, Henrik. The Complete Major Prose Plays. Trans. Rolf Fjelde. New York: New American Library, 1978. Print.

Kaucher, Dorothy Juanita. Modern Dramatic Structure. Columbia: The University of Missouri, 1928. Print. The University of Missouri Studies: A Quarterly of Research vol. 3 no. 4.

Pruter, Robin Franson. “3-act Structure.” College of DuPage, 8 Mar. 2004. Web. 24 Nov. 2013. [http://www.cod.edu/people/faculty/pru...].

Wilson, Edwin. The Theater Experience. 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011. Print.

Related articles

Syd Field, Screenwriting, and Three-Act Structure

Syd Field, Screenwriting, and Three-Act Structure “Each scene must be a drama in itself”

“Each scene must be a drama in itself” In Memoriam: Syd Field (1935-2013)

In Memoriam: Syd Field (1935-2013) Studying Aristotle’s “Poetics” – Part 13(B): A Well-Constructed Plot

Studying Aristotle’s “Poetics” – Part 13(B): A Well-Constructed Plot The Principles of Dramatic Structure: What is Rising Action?

The Principles of Dramatic Structure: What is Rising Action?

The post Dramatic Division appeared first on Kristin Rix.

October 30, 2013

Fiction: The Unsaid

Carlos watched the crowd pass by while April talked with the cheese vendor. He could hear her soft tones beneath the noise of the crowd. He was always listening for the sound of her voice, even when she wasn’t around; it was like the magnetic pull of the earth’s core. When she finished, he slipped his arm around her waist and pulled her close as they continued walking through the farmer’s market. She told him what cheese she’d bought, and he nodded.

Carlos watched the crowd pass by while April talked with the cheese vendor. He could hear her soft tones beneath the noise of the crowd. He was always listening for the sound of her voice, even when she wasn’t around; it was like the magnetic pull of the earth’s core. When she finished, he slipped his arm around her waist and pulled her close as they continued walking through the farmer’s market. She told him what cheese she’d bought, and he nodded.

“What wine should we get?” she asked, the beige mesh knit shopping bag slung over her shoulder, her free arm in her pocket. Carlos lit a cigarette and then removed his arm so they could share it between the two of them. April took small, careful drags and let the smoke float from her lips.

“A malbec is always nice,” he replied, hoping he was right. She smiled and nodded, and he smiled back. A man ran past them, bumping into Carlos’s shoulder and making him drop the cigarette. Carlos began to swear but April shrugged.

“There’s that wine shop across the street up here, we should stop now so we can enjoy the rest of the day.” She tugged on his hand and he let himself be pulled after her, in the same direction as the running man. The crowd grew thick around them, and he had a hard time holding onto her. He began to worry, but she stopped abruptly against a thick wall of observers. She turned to look at him, a silent question in her eyes, but he shrugged. He probably knew less than she.

A river of men and women were moving down the street, crowded together and shouting with one voice. It was hard to make out exactly what their words were, but Carlos had heard them before. “Let’s go back,” he said to April. “We can get wine elsewhere.”

April looked back at him, her nostrils flared with excitement. “Such bravery, Carlos,” she said. “They fight for their humanity. Have you ever felt so passionate about anything in your own life?” Then she turned back to watch the people pass.

Carlos looked at the back of her head, her long brown hair waving with the turn of her head as she strained to look. “Still,” he said. “It isn’t safe, and we have our anniversary to enjoy.”

April watched a moment longer, then let herself be pulled away. “I can’t imagine being denied the basic rights of humanity,” April continued when they’d gotten far enough away. “It’s like we’re living in the dark ages.”

Carlos pursed his lips. “I agree, but they really aren’t human, are they? Can you honestly expect humans to accept them as equals simply because they are sentient enough to demand it? Look how history has treated those who are different.”

“There is nothing that makes them different from us,” April said.

“Nothing except that humans are made by God, and they are made by humans.” Carlos titled his head back toward the street as he squeezed her hand, then let her lead him up the stairs into their flat. April began putting groceries away while Carlos made some espresso. He opened the tall balcony doors to let in the fresh air, then lit a cigarette and sat at the kitchen table to drink his coffee. April joined him and lit herself a cigarette. The sounds of the city drifted in through the window, and they both listened and smoked. Carlos could tell that April still worried at the issue in her mind.

“If there is no real difference, my love, would you consent to allow your child to marry one?” Carlos tapped the ashes of his cigarette onto his saucer. April frowned down at the ash, and he remembered that she hated it, so he moved to dump the ash into the sink. He extinguished his cigarette in a drop of water and threw it into the drain. Then he pulled out the cutting board, knife, and a few small plates and began to prepare their anniversary lunch. April stood and took some wine glasses down from the cupboard. She opened the drawer to the right of the sink and removed the bottle opener, her elbow brushing against his as she moved. She twisted the screw into the cork, turning and pulling until it popped.

“That’s a dirty question, Carlos,” April finally said. She leaned one hip against the counter near where he worked, her arms crossed, her eyes tilted up and to the right. “Objectively, no, of course not. Love is love. But such a marriage would be so dangerous and complicated, I wouldn’t wish it on my child. Would you?”

Carlos sighed quietly. “I wouldn’t wish it, no. But what if it happened, and there was no stopping it? What if you had no choice but to accept your child’s romance or to cut ties completely?”

“I would accept it. Of course I would.” April had no children, but talked often of wanting them. Carlos could never provide her with children, although he’d kept it to himself for the years of their relationship. It was one of the most painful secrets he kept from her. April carried the wine and the glasses to the table and set them down.

Sweat leaked down from Carlos’s brow into his eyes, and they stung, watering. His hand slipped with the knife against the leathery skin of the tomato, and he felt the knife slide into the flesh of his finger, his blood mingling with the slippery red intestines of the fruit. He gasped.

April rushed over, panicked. “Carlos,” she cried out. “Careful!”

“It’s ok, it’s ok,” Carlos said, turning to place his body between his hand and her. “Don’t look, it’ll only upset you.”

April tsked and pushed her way around him, a turquoise dish towel in her hand. When she saw his cut, she stopped. Her eyes were wide and focused on the blood, blood the exact same shade as the towel.

“April,” Carlos whispered. She laid the towel on the counter next to his hand, a corner falling into the formed pool and beginning to lap up the liquid. Then she looked up at him, looked him in the eye, and he could see there that her brave idealism had been a façade all along.

The post Fiction: The Unsaid appeared first on Kristin Rix.

July 12, 2013

Inspiration: MIT’s Silk Pavilion

MIT’s Mediated Matter group has constructed a silk dome using 6,500 silkworms–the first step in biological 3-D printing. The idea itself is, of course, fascinating. Here is a description of the dome from the MIT Mediated Matter webpage for the project:

The new MIT Media Lab building (E14) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The Silk Pavilion explores the relationship between digital and biological fabrication on product and architectural scales.The primary structure was created of 26 polygonal panels made of silk threads laid down by a CNC (Computer-Numerically Controlled) machine. Inspired by the silkworm’s ability to generate a 3D cocoon out of a single multi-property silk thread (1km in length), the overall geometry of the pavilion was created using an algorithm that assigns a single continuous thread across patches providing various degrees of density. Overall density variation was informed by the silkworm itself deployed as a biological printer in the creation of a secondary structure. A swarm of 6,500 silkworms was positioned at the bottom rim of the scaffold spinning flat non-woven silk patches as they locally reinforced the gaps across CNC-deposited silk fibers. Following their pupation stage the silkworms were removed. Resulting moths can produce 1.5 million eggs with the potential of constructing up to 250 additional pavilions. Affected by spatial and environmental conditions including geometrical density as well as variation in natural light and heat, the silkworms were found to migrate to darker and denser areas. Desired light effects informed variations in material organization across the surface area of the structure. A season-specific sun path diagram mapping solar trajectories in space dictated the location, size and density of apertures within the structure in order to lock-in rays of natural light entering the pavilion from South and East elevations. The central oculus is located against the East elevation and may be used as a sun-clock. Parallel basic research explored the use of silkworms as entities that can “compute” material organization based on external performance criteria. Specifically, we explored the formation of non-woven fiber structures generated by the silkworms as a computational schema for determining shape and material optimization of fiber-based surface structures. Research and Design by the Mediated Matter Research Group at the MIT Media Lab in collaboration with Prof. Fiorenzo Omenetto (TUFTS University) and Dr. James Weaver (WYSS Institute, Harvard University).

I first read about it on Wired.com in an article titled “A Mind-Blowing Dome Made By 6,500 Computer-Guided Silkworms” dated July 11, 2013. The article discusses the potential applications:

Potential applications are varied, but include fashion and architecture, and it’s possible to imagine a system like this being deployed in the aftermath of a natural disaster to build environmentally friendly shelters for refugees — if they could get over the slightly terrifying notion of living in what looks to be a giant spider web. “The project speculates about the possibility in the future to implement a biological swarm approach to 3D printing,” says Oxman. ”Imagine thousands of synthetic silkworm guided by environmental conditions such as light or heat — supporting the deposition of natural materials using techniques other than layering. This will allow us to exclude waste and achieve increased control over material location, structure and property.” Oxman sees a big future for these tiny creatures. “Google is for information what swarm manufacturing may one day become for design fabrication.”

Photograph courtesy Russell Watkins, U.K. Department for International Development from NationalGeographic.com.

Photograph courtesy Russell Watkins, U.K. Department for International Development from NationalGeographic.com.What I love most is the idea of synthetic silkworms crafting garments, structures, and more out of raw material like these silkworms. “Swarm manufacturing” reminds me of a story I read some time ago about rogue nanobots swarming around the planet infecting people and taking over their minds and actions. Now imagine a swarm of these manufacturers who, perhaps, got loose and began building weird structures of their own design. I imagine a haunting, spider-webbed landscape much like when floodwaters forced spiders into the trees of Pakistan, where they spun out of control (pardon my pun). What sort of buildings might they create? If their primary directive is to create, and they were somehow imbued with a higher intelligence, or the swarm itself at least was, what would happen? I’m also reminded of a story called “I, Rowboat” by Cory Doctorow which I came across in the Kristin Rix.

April 15, 2013

Book Review: A Visit From the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan

April 8, 2013

Fiction: The Almost Was

Saltwater lapped gently against the hull of the little sixteen foot Almost Was, and it rocked like a baby by its mother. It was the only sound besides Ray’s heavy breathing and Ed’s clomp clomping around the boat pointlessly. John sat quietly, trying to ignore the breathing and clomping, focusing on the calming sounds of the water, but his ears kept coming back to those sounds. Ray had his windbreaker propped up on some fishing poles, creating a makeshift shelter from the sun. His head lolled back, and despite the shade his face was very red, his lips cracked. John’s own lips were cracked, too, but he spent more time in the sun and had a much darker complexion, and so was faring better than both Ray and Ed, the owner of the boat they currently wallowed in. Ray was the worst, by far. His soft pink skin was like a solar panel, sucking in the rays of the harsh Atlantic sun, and the little pleasure craft that was so gently rocking them offered nothing in the way of protection from that sun.

Saltwater lapped gently against the hull of the little sixteen foot Almost Was, and it rocked like a baby by its mother. It was the only sound besides Ray’s heavy breathing and Ed’s clomp clomping around the boat pointlessly. John sat quietly, trying to ignore the breathing and clomping, focusing on the calming sounds of the water, but his ears kept coming back to those sounds. Ray had his windbreaker propped up on some fishing poles, creating a makeshift shelter from the sun. His head lolled back, and despite the shade his face was very red, his lips cracked. John’s own lips were cracked, too, but he spent more time in the sun and had a much darker complexion, and so was faring better than both Ray and Ed, the owner of the boat they currently wallowed in. Ray was the worst, by far. His soft pink skin was like a solar panel, sucking in the rays of the harsh Atlantic sun, and the little pleasure craft that was so gently rocking them offered nothing in the way of protection from that sun.

John popped a button into his mouth to try to relieve some of the dryness, a trick he’d seen on a movie once. Thank God for Hollywood, eh? Ray stirred and made a sound, and John wondered if he was starting to suffer from heatstroke. He gave a nervous look back at Ray, who was pointing listlessly off into the horizon. John scanned it, but saw nothing, and looked at Ed. Ed had his hand up over his eyes and was turned in the direction Ray pointed, a frown of concentration on his face. John tried to lick his lips but it was like licking shredded cardboard.

“Holy crap,” Ed said finally. “I think Ray spotted a boat.” Ed went to the small footlocker at the back of the boat and began to rummage through it, finally pulling out a flare gun.

When Ed dropped the lid of the locker closed, his foot knocked over the empty gas cans, and John felt a flush of anger again at Ed. If it weren’t for those empty cans, and the three-quarters empty tank, they wouldn’t be on their third morning of floating around in the goddamn Atlantic ocean. They’d have relaxed happily in some beach-side bar on the keys and been home for dinner. If Ed weren’t such a fucking cheapskate he’d have a decent radio for them to call for help.

“I’ve only got one flare,” Ed said, stepping back to the side of the boat to gaze at the horizon again, and John’s anger deepened. Of course, John thought. He was so fucking thirsty, and it just fed into his anger at Ed. They sure weren’t going to be spending Christmas together this year, or any year. Once they got out of this, if they got out of this, John was going to white-out Ed’s name personally from his family’s address book. Delete his name from his contacts list. Hire a lawyer and sue his ass.

The boat had floated a little closer, and John could see it now. It was impossible to tell anything about it except that it was moving slowly, but in their direction. “Don’t waste it, then,” John grumbled.

Ed just nodded, focused on the boat. “Yeah, yeah, wait till we’re sure they can see it,” he nodded again. There was a thick line of sweat salt crusted into a ring around the armpits of Ed’s shirt, and John was reminded of when they’d tried the transponder the first day. “No worries, guys,” Ed had said as he flipped the switch, but nothing had happened. He flipped it several more times, then pulled open the panel to check the batteries. They sat in a thick layer of white and yellow crust. “Damn,” Ed had said. Damn, John thought. Ray had puked at the sight.

Ed must have seen John out of the corner of his eye, pacing and sort of snarling at him, because he jumped a little and turned in John’s direction. “Man, you ok? Calm down, we’ll be ok.”

“Ok?” John spat. “Ok would have been plenty of drinking water and some emergency rations instead of McDonald’s and a twelve-pack of Old Milwaukee. Ok would have been the captain,” John poked Ed’s chest, forcing him back against the rail, “of the fucking” poke “boat” poke “making sure we had enough gas to make it.”

“Hey man,” Ed stammered, his hands fumbling with the flare gun. He almost lost it into the ocean. John looked down at it and went a little pale, backing up.

“Hey, sorry, Ed.” John wiped his face. There was barely any sweat, and his head was spinning. He realized suddenly that he’d swallowed the button, and when he looked down at his shirt he discovered that there were five buttons already missing. He didn’t remember five buttons. His shirt flapped open, the tails listing a little to the left, pulling against the single top button that was left. Tommy Bahama, his mind said. He shook his head a little, and Ray made another sound. They both looked back at the boat and it was much closer. John shivered in excitement and started to shout, waving his arms. His voice was hoarse and dry, though, and came out rather less passionately than he felt.

Someone on the boat waved their arms, and John could see that the boat was filled with people. As it drifted closer and closer, it became apparent that the boat was actually smaller than theirs, a dinghy really, and was brimming with men and women, their extremely dark skin glistening in the hot sun. People were sitting on the thin rails and holding onto each other to stay in. Some of the women held heavy bundles on their heads with their long, slim black arms. Their voices began to drift on the wind to where the men sat silently, and John could detect some French Creole. Suddenly the flare launched itself from behind John and he jumped, turning.

“What the hell, Ed?” John chirped. “Do you realize what that is?” He pointed at the boat behind him.

“It’s a possible rescue,” Ed replied. His eyes fell on the boat, squinted, and went wide. “Oh, crap.”

The boat was close enough for them to see the faces of what John suspected were Haitians. Their bright white eyes were all turned on the three men, and they chattered quickly among themselves. The women spoke louder than the men, and underneath it all was the strained hum of the tiny motor pushing against the weight of so many people.

“What if they try to board us?” John whispered. “They might have guns.”

Suddenly all the Haitian eyes turned and looked past the Almost Was, and the voices of the women rose in pitch. The men’s dark faces grew angry, and they began pointing and shouting at John, Ed, and Ray, as they passed them. John and Ed turned to look behind them, and John’s body went cold with relief as the distinctive cut of a U.S. Coast Guard boat came into view. It approached the two boats at a swift clip. The Haitian boat swung around and began chugging slowly back the way they came. “This is the United States Coast Guard,” the ship boomed. “Please turn off your engine and await further inquiry.”

The Haitian boat’s engine cut out, making a sort of coughing sound at the end. A man fell out and began to swim away from the boat and the Guard, one woman in particular yelling at him loudly and flailing her arm. The Coast Guard pulled up on its starboard side, leaving the Almost Was on its port side. One of the officers leaned over the rail and shouted down, “Hey, you guys doin’ ok?”

“No!” John and Ed shouted at the same time. “We ran out of gas,” Ed continued. “We’ve been here three days and I’m pretty sure my buddy is suffering from heat stroke.”

The officer shielded his eyes and took a good look at them, then disappeared back into the boat. Ed and John stood speechless until he returned, tossing them a few bottles of water and some Power Bars. “The refugees take priority, but we’ll radio a nearby ship to pick you up.”

“Wait, what the fuck?” Ed shouted. “We’re tax-paying Americans and we could die out here, man. We should take fucking priority.”

The officer grimaced. “Look, sir,” he said carefully. “It’s not our job to pick up assholes who run out of gas. We have better things to do with our time.” He hooked a thumb back over his shoulder.

John sat down on the locker next to Ray, and turned to give him some of the water. He heard the officer shout behind him, “Don’t let your friend drink too much all at once. He’ll throw it up, won’t do him any good. Soak his clothes to help cool him off.” He tossed some more water over to them, the bottles bouncing onto the floor of the boat as they hit. “We’ll get you some help, don’t worry. Sit tight a little longer.” He gave a short, tight little wave and went back to the other side of the boat.

Ed watched helplessly as the Coast Guard sailed away with the Haitians, while John poured water onto the collar of Ray’s shirt. Ray’s fingers grasped for more, but he was weak and John was able to pull the bottle away. “More like asshole, singular,” Ray rasped quietly, nodding at Ed’s pacing, sweaty back, and a loud, barking laugh escaped John before he could catch it.

“What’s so funny?” Ed asked, taking huge gulps of water. John took a couple of small sips himself, not trusting his own physical state to take more. Instead he poured the rest of the bottle down the back of his neck, soaking his own shirt. Neither John nor Ray answered.

John felt overcome by calm after having seen the Coast Guard and heard the officer’s voice, though once the ship disappeared back over the horizon the whole experience began to fade like dream, a heat mirage. Still, having seen the crumbs of civilization after three brutal days of endless blue oblivion snapped John back into sanity, and he began to realize that they could make it out of this alive. A few hours ago, they might as well have been floating on the forgotten oceans of Mars for all they saw around them; not even so much as a dolphin snorting at them from the side of the boat or the flecks of gull shit on their unsuspecting backs and heads. The Coast Guard had put John’s world back into perspective.

Ed leaned over the side of the Almost Was and retched up the water he had gulped too quickly. John frowned but helped Ray drink a little more water. There was a Power Bar by John’s foot. He leaned down and grabbed it, ripping open the golden wrapper with his teeth and taking a small bite. The texture was a little rubbery, but the vanilla flavor was about the best thing he’d ever tasted. He pulled off a small bite and handed it to Ray, who ate it gingerly; his lips were in pretty bad shape. John gave him another sip, squirming a little on the uncomfortable lid of the locker. Ray’s windbreaker shade was falling across John’s face now, too, and a breeze picked up, cooling them from the water that now soaked their shirts. John closed his eyes and sighed, the water soaking into his skin, into his soul. Ray patted his shoulder and he smiled without opening his eyes, nodded. They were going to be okay.

The post Fiction: The Almost Was appeared first on Kristin Rix.

February 28, 2013

Fiction: The Rattlers of Blackwell, OK

Wayland Delray rocked his 1984 Dodge Ram over the tongue of the Comfort Inn parking lot, one hand palming the steering wheel in big, round circles. He tucked it in between two other trucks; one a Ram and the other some foreign-made piece of crap. He grabbed his duffel from the space behind his driver’s seat and slung the strap over his shoulder. His boots made a satisfying heel-on-gravel crunch in the quiet of the fading day. He could see into the tinted windows of the bar that sat in one corner of the parking lot, just opposite the motel doors which made for an easy stumble in any kind of weather. A couple of guys sat at the bar, beers in hand, with the identical shoulder slumps of a long day’s end. On an average day, Wayland would be right there next to them, bloodshot eyes rolled up to the glare of the television, transfixed like blind moles seeing the shine of God for the first time.

Wayland Delray rocked his 1984 Dodge Ram over the tongue of the Comfort Inn parking lot, one hand palming the steering wheel in big, round circles. He tucked it in between two other trucks; one a Ram and the other some foreign-made piece of crap. He grabbed his duffel from the space behind his driver’s seat and slung the strap over his shoulder. His boots made a satisfying heel-on-gravel crunch in the quiet of the fading day. He could see into the tinted windows of the bar that sat in one corner of the parking lot, just opposite the motel doors which made for an easy stumble in any kind of weather. A couple of guys sat at the bar, beers in hand, with the identical shoulder slumps of a long day’s end. On an average day, Wayland would be right there next to them, bloodshot eyes rolled up to the glare of the television, transfixed like blind moles seeing the shine of God for the first time.

Instead, Wayland walked toward to lobby doors, which swished open as he neared.

“Welcome back, Wayland.” The woman at the counter wore a small rectangle of burgundy plastic pinned to her coordinating polo. It bore a white strip with the raised letters of “Donnette.” Donnette often worked the front desk in the afternoons. “Checkin’ in?” Her permed curls were pulled back into a white banana clip, and her bangs were teased into a pouf of hair set with what Wayland often imagined must be a fortune in hair spray. She always had a different color eye shadow swept across her upper lid; today it was bright turquoise. Her lips glistened with a soft pink gloss. Wayland suspected that she thought there was something between them, that his business brought him to Blackwell but his heart brought him to her motel. He thought she might be right in that, but hadn’t had the time to court her in the ways his papa had showed him was proper. Besides, tonight would be his last night. By next week Donnette will have found another man to fancy herself engaged with, and Wayland would be nothing but a bad memory.

“Staying all week again?” Donnette’s fingernails clicked on the keyboard of her computer.

“No, ma’am,” Wayland replied. “Just the night.”

Donnette stopped typing and she looked up at him with her icy blue eyes, one darkly-painted eyebrow arched up. “Is that so?”

“Work’s just about finished.” Wayland didn’t meet her gaze until he heard her fingernails start to tap again.

“Well maybe you’ll be over at the bar for a drink tonight. I know I will,” she paused, “when I get off at nine.”

“May be,” he replied, making sure not to inflect the word one way or another.

Donnette dropped his key onto the counter and let her fingers linger a moment, so he had to wait before he could take the key. Finally she moved her hand away and he took it, the plastic card scraping against the worn particle-board edge of the counter where the burgundy paint had begun to chip.

“You feelin’ ok, Wayland Delray?” Donnette looked hard at him.

“Yes, ma’am.” Wayland turned away.

Donnette usually gave Wayland room 127 out of habit, and today was no different. It was easier on motel staff to give regulars the same rooms. Wayland turned right past the front desk and walked down the hall. About halfway down, a room door opened and a man came out tugging his cowboy hat on. Wayland tried to avoid it, but the man caught his eye and so they exchanged straight-faced nods. After the man passed, he waited until the hall was clear, then stopped at room 125 and put his ear to the door. He held his breath, and his heart was pounding so loud, but he didn’t think he heard anyone on the other side. He decided to knock, and when he did he scooted down the hall to his own room and stuck his key in the slot to unlock it. There was a grinding noise and the little light flashed red at him. He cursed, but 125 hadn’t opened so he let himself breathe a little. He tried his key again, this time drawing the card out slowly, and the light flashed green. There was a heavy click. He turned the handle and pushed the door in.

Wayland dropped his duffel in front of the mirrored sliding doors of the closet, then closed and latched his door. He walked to the door that adjoined his room to 125 and pressed his ear against it, his palms flat on either side of his head. Still nothing. Carefully, he turned the deadbolt lock until it clicked, and put his hand on the handle of the door, slowly pushing down. The door swung open onto the backside of 125, and Wayland took the handle of that door. His palm was sweaty, so his wiped it on the thigh of his jeans. Then he took the handle again, and slowly pushed down.

The door cracked open onto darkness, and Wayland let out a woosh of breath he hadn’t known he’d been holding. He pulled the door shut again, not so much as glancing into the quiet of the room beyond. Then he closed the door on his side, but left it cracked. He stared at the door until he heard the talk and laughter of men moving down the hallway outside.

Wayland took a shower. He used all of the shampoo in the little free bottle, and half a bar of soap, scrubbing the work and sweat of the day off himself. As he soaped down, he stared at the web of blackened tile grout in the corner of the shower, where mold had stained it. He left the evidence of his shower in a disheveled pile on the floor behind the toilet, and he used his forearm to wipe away some of the steam so he could comb his hair. He parted it down the side as always, and let the short hairs in front curl over. There was more gray streaked through the dark brown than Wayland remembered.

He dressed all the way to his belt and boots, then repacked his duffel and zipped it closed. Then he unzipped it and pulled it open so that it yawned wide. He moved the duffel closer to the adjoining door so that it sat next to where the door opened. Then he pulled the bag open wide again.

Wayland took up the television remote and sat in the upholstered chair. As he flipped stations, he noticed that the upholstery had probably never been cleaned, and years of working men’s hands rested on the ends, leaving their mark in layers of dirt that turned the gold-flecked burgundy fabric to a shade of dark pink. Dusky rose, his momma would have called it.

At some point, Wayland fell asleep. His head jerked up, and he looked around the dark room wildly, trying to fix his eyes on a source of light. Then he heard it, from the room next door: his neighbor had come back. Wayland could hear all too much through that adjoining door. The clink of glasses, the laughter; it sounded like a celebration. Wayland spat on the floor in front of him, then used the toe of his boot to rub the wet mucous into the carpet. He used the remote to turn the television off, and he sat in the dark staring at the door with intent. He would not fall asleep again.

Finally the sounds quieted, and he heard the door open and close. As he listened, Wayland could track his neighbor’s actions through the room: the final trip to the bathroom, boots kicked off against the wall, pants falling to the floor, the belt buckle hitting the wire frame of the suitcase stand, the squeak of bedsprings. Twenty minutes later, the sound of snoring.

Wayland stood and stretched. He walked to the window and slid it open. Cool autumn air spilled in, and he looked out onto the dark, quiet parking lot. The bar was closed, its neon signs shut off. His truck sat just two spaces down from the window. Wayland turned and made his way to the adjoining door, stopping to reach into his duffel bag. He pulled out a long-handled knife, the blade rusted from the execution of rattlers who’d had the misfortune to cross Wayland’s path. He had one more rattler to kill. He gently pulled the adjoining door open, paused, and opened the other door, slipping into 125.

The post Fiction: The Rattlers of Blackwell, OK appeared first on Kristin Rix.

February 9, 2013

Book Review: Among Others by Jo Walton

Buy on Amazon.com

Buy on Amazon.comMy Goodreads rating: 5 of 5 stars

Winner of the 2011 Nebula Award for Best Novel

Winner of the 2012 Hugo Award for Best Novel

“Among Others” is a coming-of-age story written in the style of a young girl’s journal.

It has taken me several months to decide how I ultimately feel about this book. Immediately after finishing it, I liked it more than I did while reading it. I am immensely impressed with how Jo Walton is able to make the complete book more than the sum of its parts, and how, at least for me, the thesis of it isn’t apparent until the whole thing has been read.

The inner world of the main character, Morwenna, is compelling and magical. The way she views and experiences magic is exactly how any intelligent young girl with an imagination and an interest in fantasy/sci fi would explain magic to herself. Morwenna exists in a world inhabited by adults who do crazy, irrational, and frightening things. At any moment her crazy mother or absent father could swoop in and decide to take her away, or threaten her life, or things she can’t even anticipate, and so she lives in a constant state of insecurity with regards to the people who are supposed to provide her with security. She has no control over her life. To maintain her sanity, and to give herself a sense of security, she believes that she can affect the world through the use of magic and spells. It is this belief that ultimately saves her.

What I enjoyed most about this book is that it is never made explicitly clear whether or not the magic and fairies are real or in Morwenna’s imagination. This is especially true once I finished the book, because at any given time while reading it I was always waiting for that one definitive moment where I knew for sure. On one hand, it could all be true and work exactly as Morwenna described. On the other hand, it could all just be a coping mechanism in her imagination. When I originally read the book I assumed that Morwenna, the narrator, was a reliable witness. I look forward to rereading it knowing that she may not be, and see how it might change the experience.

I also appreciate the way the author handles magic. It is both classic and unique at the same time. I enjoy the way Morwenna thinks about magic all the time, about its rules and how it would or wouldn’t work, and how casting spells work. I also enjoyed the fairies. It felt very much like the sort of spellcrafting and fairy knowledge you would get from an ancient part of Europe, from an old woman who learned it from her granny, who learned it from HER granny, who was a hedge witch. It all tickled the part of me that likes to find dusty old books about herbs in the back corner of used book stores, that hoards rusty old keys, and that always looks through holes in stones to see if fairies are around. It’s magic that is worn around the edges, a little dirty, a little sinister and unpredictable. You know, “real” magic.

While I was reading, it wasn’t exactly a perfect experience for me. It’s “another” book involving magic and a boarding school, as we have seen with (of course) Harry Potter, and Lev Grossman’s The Magicians, to name a couple. It was well done and seemed appropriate, but I’m just saying it’s been done before. In a similar vein, it seems like all of the exciting stuff happens off screen. Morwenna alludes to events that sound very dramatic and exciting, but that happened in the past. Instead we experience a pretty typical series of events for a young person at a boarding school: boys, books, holidays, the difficulty of making friends, etc. Again, it was well done and seemed appropriate, but I hadn’t really realize I was getting myself into that type of “coming of age” story prior to starting it. Finally, Morwenna spends a lot of time talking about other science fiction books, about their themes and covers and characters. I really enjoyed this about the book because I am a huge sci fi fan, but occasionally I would have liked to have seen the mentioned cover, or had a more detailed explanation of why Morwenna believed something about a character. Often times she would state an opinion but say nothing more about why. I can understand that this is how a young person would journal, but I would have enjoyed the added detail.

Walton has a way of spinning a world around her words that is evocative of both the modern day and a storied and mythic past. The characters have depth and history and complexity. This is one of the few books I’ve read that I look forward to reading again.

Related articles

Among Others by Jo Walton – review

Among Others by Jo Walton – review A cool use of Pintrest: The books of ‘Among Others’

A cool use of Pintrest: The books of ‘Among Others’ Jo Walton on Ursula Le Guin’s Tehanu

Jo Walton on Ursula Le Guin’s Tehanu [SPOILERS] Jo Walton Uses Her Krell-Like Brain to Visualize the Cosmic All of Patrick Rothfuss’s Trilogy

[SPOILERS] Jo Walton Uses Her Krell-Like Brain to Visualize the Cosmic All of Patrick Rothfuss’s Trilogy Jo Walton Reviews Vernor Vinge’s “A Fire Upon the Deep”

Jo Walton Reviews Vernor Vinge’s “A Fire Upon the Deep”

The post Book Review: Among Others by Jo Walton appeared first on Kristin Rix.

November 13, 2012

“The Watcher” Takes Spot in First-Honorable Mentions

Visit Readers’ Realm

Visit Readers’ Realm“The Watcher,” a flash-fiction horror story I entered into the Readers’ Realm Scary Flash Fiction contest last month, took a spot in the First-Honorable Mentions. Of the piece, the judges said “The writing itself was elegant.” Be sure to read “The Watcher,” and all of the other great entries over at Readers’ Realm.

The post “The Watcher” Takes Spot in First-Honorable Mentions appeared first on Kristin Rix.

October 13, 2012

Essay: Colon End Parenthesis

Punctuation: An Ever Evolving Form of Communication

The word “punctuation” comes from the Latin punctus, meaning “point.” Indeed, punctuation marks were originally called “points” (Partridge 3). Therefore, “punctuation” means “the use of points” (Reimer par 2). Malcolm Beckwith Parkes wrote in his authoritative work Pause and Effect that “punctuation is a phenomenon of written language, and its history is bound up with that of the written medium” (1). Indeed, the evolution of punctuation runs parallel with the development of technology surrounding the written word, and the dissemination of the ability to produce the written word has allowed more and more individuals to participate in that evolution. Students today learn set rules, and yet, punctuation is an ever-changing and reinterpreted aspect of conveying meaning to a reader. As Pico Iyer wrote in an essay for Time magazine, “By establishing the relations between words, punctuation establishes the relations between people using the words” (Iyer 80). As our understanding of the relationship between the reader and the written word, and the technology used to convey the written word, has evolved, so has our understanding and use of punctuation.

Reading As a Byproduct of the Spoken Word

Saint Augustine, in the dialog De Magistro, said of the reader’s experience of writing, “thus it is that when a word is written it makes a sign to the eyes whereby that which pertains to the ears enters the mind” (Ita fit cum scribitur verbum, signum fiat oculis, quo illud quod ad aures pertinent veniat in mentem) (Parkes 9). Therefore, Augustine viewed writing as a mere representation of the spoken word. Writing arose from a culture of oratory, wherein the ability to make a good speech in tribunals and public assemblies was considered the ideal. Parkes notes that “literacy was the product of a conservative educational tradition in which teaching was directed towards the preparation of pupils for effective public speaking” (9). The ability to read was of secondary concern. At that early time, it was a rather unheard-of idea for someone to read silently. Because the words were meant to be spoken, it was inconceivable that a good reading could occur without it being spoken aloud.

Figure 1: Scripta Continua as seen in an early copy of Virgil’s Aeneid (Parkes 162)

Early Punctuation and the Emergence of Conventions

The oldest-known method for organizing and formatting text was called scripta continua (fig 1), “continued script,” in which there were no spaces between words, and all letters were the same height. It has been found in surviving texts from as early as the second century BCE (Parkes 161). It is hard to imagine a time in which something as simple as separating words had not yet been invented. Eventually, however, scribes recognized that it would be useful to indicate moments of pause for dramatic effect, and opportunities for the reader to breathe. One can see forms of this in figure 1 (circled), as this particular scribe employed early periods and apostrophes. By the twelfth century, the fundamental conventions of writing had been established (Parkes 41). Scribes began to use word separation and varied letter height to aid readers and create word units. However, scribes were at liberty to copy, or not copy, punctuation marks from works they were reproducing. The twelfth century saw a decline in monastic scribes, and an increase in commercial scribes who copied books both for customers and for themselves. Because the commercial scribes did not work with the same sort of discipline and practice seen in a monastery, they were often left to their own devices in deciphering unfamiliar punctuation, or even layers of different superimposed marks from generations of readers, in a work. Such scribes often ignored the confusion in favor of whatever system they preferred (Parkes 42).

The Period

As stated before, punctuation was originally called “points,” and the use of them called “pointing.” This is, perhaps, due to one of the first and (arguably) the most important of them all: the period. The period has also been called a point, full (or perfect) point, full (or complete) pause, and full stop. It was called a “period” because it came at the end of a periodic sentence (Partridge 9), and thus referred to the sentence as a whole, rather than just the mark. In French, the periode, Latin the periodus, and Greek the peridos, from peri, meaning “round” and hodos, “a way,” and thus “a going round,” or “a rounding off,” especially as applied to time, and more especially still to the time represented by breathing (Partridge 9). It provided an opportunity for the reader, who was originally assumed to be reading aloud, to breathe between sentences.

The Comma

The comma is a Latin translation of the Greek homma, related to hoptein, “to cut,” and thus “a cutting” or “a cutting off.” As a comma tends to separate a clause, it can be seen as “cutting the clause off” from the rest of the sentence. In Italian, the word comma actually means “paragraph,” as in a section of the work that is cut off, or separated, from the rest of the work. The comma originally looked a little like a modern question mark, with the curved part we now use situated above a period:  This older version was used most frequently by fourteenth-century scribes, but became the modern version once the printing press was invented (Parkes 303). The virgil, or “/”, was originally used by the French as a comma. It is more commonly known as the oblique, or oblique stroke/line. The French still call a comma virgule, from the Latin virgula, a small rod, even though they now use the modern small semi-circular form (Partridge 151).

This older version was used most frequently by fourteenth-century scribes, but became the modern version once the printing press was invented (Parkes 303). The virgil, or “/”, was originally used by the French as a comma. It is more commonly known as the oblique, or oblique stroke/line. The French still call a comma virgule, from the Latin virgula, a small rod, even though they now use the modern small semi-circular form (Partridge 151).

The Paragraph

The paragraph was originally indicated by a stroke, usually with a dot over it. It was used especially to indicate the various characters in a speech or stage play. Understanding this leads one into the etymology of the word itself. “Paragraph” comes from the Late Latin paragraphus, Greek paragraphos, which mean a line or stroke drawn at the side: para (beside) and graphein (to write). The modern practice of indenting at the start of a new paragraph, in fact, comes from the habit of early printers to leave a blank space for an illuminator to insert a large decorated initial (Partridge 165).

The Printing Press Establishes Early Standardization

It was not until the printing press that standardization of punctuation occurred, mostly due to an Italian printer by the name of Aldus Manutius, who operated his “Aldine” Press in Venice (Partridge 6) in the fifteenth century (Parkes 51). He is also attributed with the invention of the Italic form. The font which he produced became the European norm of the time, and was called the “old roman” letter. It was in this “old roman” font that some of the more familiar versions of modern punctuation can be found, such as the “semi-circular ‘comma’, the semi-circular parentheses, the upright interrogativus [question mark], and…the semi-colon” (Parkes 51). The invention of the printing press, by Johannes Gutenberg in the middle of the fifteenth century, allowed books to be produced at a far faster rate than before, causing a “great increase in the number produced” (Kreis). Thus, more books were getting into the hands of more people. Though the production of the books was retained by the press operators, the written word itself, and its punctuation, was being seen by more than just scholars and the wealthy or noble.

Technology as Broader Communication Tools

The invention of the typewriter further disseminated the production and use of the written word, and punctuation. Though it only last a few hundred years, it put the creation of the written word into the hands of mere mortals, as long as they could afford to buy one. The patent for the first typewriter was issued in 1714 (The Typewriter). It was originally conceived of for business and government use, but was quickly integrated into the public use. Many great novelists wrote their work on a typewriter. Jack Kerouac wrote On the Road using a continuous roll of teletype paper fed into a typewriter (Two-Minute History). Soon, though, the computer came along. It, too, was originally conceived of for business and government, but as time went by, more and more people had a computer in their home. Finally, the advent of the internet allowed for all of our digital words to quickly and easily flood out into the world.

Modern Evolutionary Steps

Even today, we can see a continued evolution of punctuation. For example, digital discourse has evolved punctuation into a form of visual-linguistic art, called emoticons, and are used to express whole words and emotions by the combination of multiple punctuation marks and letters. The smiley face, represented by “:)” or “:-)”, is one of the more common of such emoticons (Garrison 119). It is created using a colon and an end parenthesis, or a colon, hyphen, and end parenthesis. Though not accepted in the context of formal work, the use of emoticons and other specialized abbreviations of phrases are being assessed as a separate and legitimate new aspect of language, made possible by the advent of digital publication. As David Bergland wrote in Printing in a Digital World, “digitalization is just the most recent step in the abridging tactic of language. So language survives digitalization easily because it has already traveled most of the way there” (Brody 156). Language, like punctuation, is fluid and constantly changing based on the needs of the people who use it. Research indicates that one of the ways emoticons are used in online discourse is as an enhancement to punctuation. Emoticons are used in several places within an online utterance: before the utterance, in the middle of the utterance, after the utterance, and alone as the entire utterance. An utterance, as used in this context, is any expression used in online communication, such as a text message, email, or instant chat session. The repetitive use of such emoticons, and in such ways, indicates that there is a generally-known convention about their use. When emoticons are seen to be used in the middle of sentences, they often “[distinguish] the main idea of the utterance (the subject) from its supporting information” (Garrison 122). The emoticon is thus being used to punctuate the utterance in a manner much like a comma or a colon (Garrison 115). They set the tone and nuance of the communication, and indicate the expected response for the utterance in ways that the early punctuation marks set the pause and breathing marks for people who read a piece aloud.

Seeing Deeper Into a Message

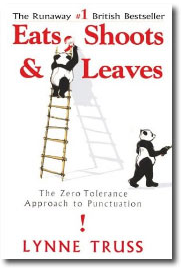

The better we, as writers and readers, understand how punctuation affects our words, the more powerful our words will be, and the more enduring the message. Iyer put it very eloquently when he said “punctuation, in short, gives us the human voice, and all the meanings that lie between the words” (80). A string of words has meaning, but often too many possible meanings or a meaning that is very different from the one intended. It isn’t until punctuation is inserted that the nuance of meaning is established and the message clarified. For example, in the book Eats, Shoots & Leaves (seen left), the author uses the title itself to prove her point. Read without the comma, as “eats shoots and leaves,” it suggests that a panda much like the one on the cover eats the shoots and leaves of bamboo trees. Yet with the comma, it reads as “eats, shoots, and leaves”—an altogether different connotation entirely, especially where the panda is concerned. The panda on the 2004 cover knows its stuff, though, and is seen on a ladder eliminating the deadly comma.

The better we, as writers and readers, understand how punctuation affects our words, the more powerful our words will be, and the more enduring the message. Iyer put it very eloquently when he said “punctuation, in short, gives us the human voice, and all the meanings that lie between the words” (80). A string of words has meaning, but often too many possible meanings or a meaning that is very different from the one intended. It isn’t until punctuation is inserted that the nuance of meaning is established and the message clarified. For example, in the book Eats, Shoots & Leaves (seen left), the author uses the title itself to prove her point. Read without the comma, as “eats shoots and leaves,” it suggests that a panda much like the one on the cover eats the shoots and leaves of bamboo trees. Yet with the comma, it reads as “eats, shoots, and leaves”—an altogether different connotation entirely, especially where the panda is concerned. The panda on the 2004 cover knows its stuff, though, and is seen on a ladder eliminating the deadly comma.

Punctuation as Art

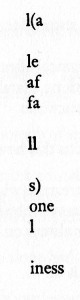

Punctuation often appears to be the workhorse of the literary world, but it has a creative side as well. Punctuation is much like a refined brushstroke. A painter must first understand how to properly use the medium before creativity can be unleashed. Picasso began formal art study at six or seven (McNeese 17). It wasn’t until he mastered his technique and understanding of the medium that he could form his own style and begin to explore the deeper creative realms of his art. Indeed, Picasso deconstructed painting in a series labeled as his “Cubist” period, where objects are painted as though seen from many different angles at once. A similar deconstruction occurs in the poem “One” by E.E. Cummings, from his series 95 Poems (seen left). In this poem, Cummings plays with font (mis)representation, placement, and the meaning of parentheses to create a simple poem but a powerful meaning. The font character “1” can appear to mean both the number “one” or the lowercase version of the letter “L.” That is, at least, in the Times New Roman font, which is the font used for the poem itself. The title of the poem, being the first in a series of ninety-five poems, leads the reader to see this character as a “one.” Cummings does love his parentheses; the image isolated by them is of a leaf falling. Yet once we get to the end of the parentheses, there we have “one” again, followed by what appears to be another numeral “one” and the confusing “iness.” What could this mean? We go back and read the poem again, this time ignoring what was inside the parentheses (as it is theoretically extraneous information), and we come to the conclusion of the poem: loneliness. Thus, in just twenty-three characters and only two punctuation marks, we are shown the depth of the loneliness in a singular falling leaf.

Punctuation often appears to be the workhorse of the literary world, but it has a creative side as well. Punctuation is much like a refined brushstroke. A painter must first understand how to properly use the medium before creativity can be unleashed. Picasso began formal art study at six or seven (McNeese 17). It wasn’t until he mastered his technique and understanding of the medium that he could form his own style and begin to explore the deeper creative realms of his art. Indeed, Picasso deconstructed painting in a series labeled as his “Cubist” period, where objects are painted as though seen from many different angles at once. A similar deconstruction occurs in the poem “One” by E.E. Cummings, from his series 95 Poems (seen left). In this poem, Cummings plays with font (mis)representation, placement, and the meaning of parentheses to create a simple poem but a powerful meaning. The font character “1” can appear to mean both the number “one” or the lowercase version of the letter “L.” That is, at least, in the Times New Roman font, which is the font used for the poem itself. The title of the poem, being the first in a series of ninety-five poems, leads the reader to see this character as a “one.” Cummings does love his parentheses; the image isolated by them is of a leaf falling. Yet once we get to the end of the parentheses, there we have “one” again, followed by what appears to be another numeral “one” and the confusing “iness.” What could this mean? We go back and read the poem again, this time ignoring what was inside the parentheses (as it is theoretically extraneous information), and we come to the conclusion of the poem: loneliness. Thus, in just twenty-three characters and only two punctuation marks, we are shown the depth of the loneliness in a singular falling leaf.

Punctuation’s Evolutionary Past, Present, and Future

Though the average English class would make someone think otherwise, the use of punctuation and its rules and symbols have evolved drastically over time. The understanding of and requirements for the written word have informed decisions about punctuation and determined how they have evolved. When writing itself was a new technology, written language started as the record of oratory, and marks were made to assist that goal. As understanding of the written word and its relationship to the reader evolved, so did the marks. When the printing press was invented, the format and technology of the written word further evolved, and the marks were developed into a standard. Now, with the advent of electronic communication, we are seeing further evolution in the use of punctuation marks. The dissemination of our written language has enabled more and more individuals to participate in the ongoing dialog of language and punctuation use. This, in turn, has shaped the direction and flow of punctuation evolution. More people using punctuation means more people thinking about, and redrawing the lines of, punctuation. Though proper knowledge and use of punctuation is critical to the effective communication of ideas, there is still much room for manipulation of the marks to bridge the gap between the word and the mind, between the mind and the imagination. Our world is evolving before our very eyes, and one need only look to punctuation to see the proof.

Works Cited

Brody, Jennifer Devere. Punctuation: Art, Politics, and Play. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008. Print.

Cummings, E.E. 95 Poems. New York: Liveright, 2002. Print.

Garrison, Anthony, et al. “Conventional Faces: Emoticons in Instant Messaging Discourse.” Computers & Composition 28.2 (2011): 112-125. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 28 September 2011.

Iyer, Pico. “In Praise of the Humble Comma.” Time June 1988: 80-81. Print.

Kreis, Steven. “The Printing Press.” History Guide. HistoryGuide.org 2004. Web. 11 October 2011.

McNeese, Tim. Pablo Picasso. New York: Infobase Publishing, 2006. Print.

Parkes, Malcolm Beckwith. Pause and Effect: An Introduction to the History of Punctuation in the West. Berkley: University of California Press, 1993. Print.

Partridge, Eric. You Have a Point There: A Guide to Punctuation and Its Allies. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1953. Print.

Reimer, Stephen R. “Manuscript Studies: Medieval and Early Modern; IV.vii. Paleography: Punctuation.” Edmonton, Canada: University of Alberta, 1998. Web. 22 September 2011.

“The Typewriter: an Informal History.” IBM Archives. IBM August 1977. Web. 11 October 2011.

Truss, Lynne. Eats, Shoots & Leaves. New York: Pengui-Gotham, 2003. Print.

“Two-Minute History of the Kerouac Scroll.” Kerouac Scroll Tour Schedule. On the Road.org n.d. Web. 11 October 2011.

Related articles

Crucial Grammar Rules for Writers

Crucial Grammar Rules for Writers Leadership Through Punctuation

Leadership Through Punctuation The Cambridge comma

The Cambridge comma Is a comma grammar?

Is a comma grammar? The Joy of Punctuation

The Joy of Punctuation

The post Essay: Colon End Parenthesis appeared first on Kristin Rix.