Jeff Edwards's Blog, page 4

January 21, 2014

LCS In Trouble

What happens when a warship isn’t ready for combat? I’ve got some personal experience with that question, and it’s not a comfortable feeling.

Senior Pentagon officials have been asking that same question about the Littoral Combat Ship program, and the future of LCS is in serious doubt as a result. In a memo issued earlier this month, acting deputy defense secretary Christine Fox ordered the Navy to stop LCS production at 32 ships, and begin developing a “more capable surface combatant.”

Her doubts about the program are reinforced by a 2012 report from Rear Admiral Samuel Perez, which questions the ability of both LCS variants to carry out their combat missions, or even to defend themselves against the kinds of threats they can be expected to encounter.

Her doubts about the program are reinforced by a 2012 report from Rear Admiral Samuel Perez, which questions the ability of both LCS variants to carry out their combat missions, or even to defend themselves against the kinds of threats they can be expected to encounter.

As I mentioned earlier, I’ve got some experience with that situation. In the early eighties, I was stationed aboard a Leahy class guided missile cruiser. Plenty of missiles and anti-air firepower, but no guns. We could defend an aircraft carrier against hostile air power, but our only protection against close-in surface threats consisted of four fifty-cal machine guns. That wasn’t a problem most of the time, because we usually deployed with a carrier battle group. If we got into trouble, there were frigates and destroyers covering our back.

But independent steaming was another matter. If we were operating alone when a surface threat popped up, we were essentially screwed. We could have been cut to ribbons, simply because we didn’t have the right mix of weapons to repel a close-in surface threat.

That never happened while the Leahy class was in service, but those of us who served aboard those ships knew that it could happen. It’s not a good feeling, going into harm’s way with a ship that’s not ready for battle.

The Department of the Navy and the Office of the Secretary of Defense are working on a probation program to re-evaluate and improve the combat capabilities of LCS. I hope they succeed. More importantly, I hope the Littoral Combat Ships turn out to have more resilience than the current evaluations suggest.

Those are our Sailors out there, hanging their lives over the line in defense of our country. They deserve a ship that can fight.

January 19, 2014

Navy Prepares Laser Weapon For Sea

I don’t know if this is the future of naval warfare, but it’s pretty damned cool…

The Navy is gearing up to deploy the prototype LaWS (Laser Weapons System) aboard the amphibious ship USS Ponce later this year. Apparently, the testing to-date has gone pretty well, because this deployment is nearly two years ahead of schedule.

Unfortunately, the video clip has no audio track, but the pictures tell the story nicely.

According to Chief of Naval Research Admiral Matthew Klunder, the cost of firing such ”directed energy” weapons could be less than $1 per shot.

The only thing cooler than getting your Death Star on, is doing it at Wal-Mart prices.

January 14, 2014

The Other Side of the Mike

I’ve got a smattering of talent in several areas, or at least I like to pretend that I do. I write; I sketch; I play guitar; I mess around a bit with animation, and my forays into the culinary arts occasionally result in something that resembles food. I don’t let any of these meager proficiencies go to my head, because I know that my limitations equal (or exceed) my abilities. For instance… I stink at basketball; I can’t keep a houseplant alive for more than about three hours, and I dance like a wildebeest with a dislocated pelvis. (I’m not kidding. Don’t make the mistake of dancing with me unless you heal quickly, and your medical coverage doesn’t have a clause that limits catastrophic injuries.)

I’ve recently discovered another of my limitations. I have exactly zero talent as a voice artist. I know this for two reasons…

First, I spent an afternoon in a sound studio a few weeks ago, recording the Author’s Notes for the audiobook edition of The Seventh Angel. And second, I’ve had the pleasure of working with a real voice artist, so I know what actual vocal talent looks like. Or rather, what it sounds like.

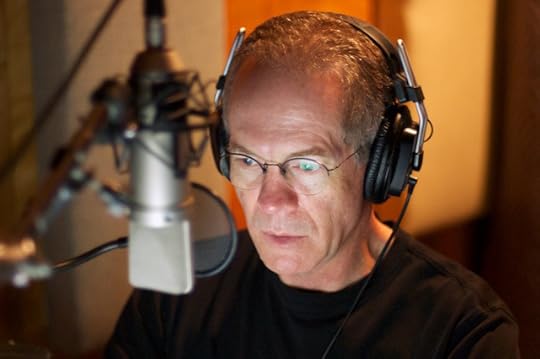

Craig Good at the mike. (Photo courtesy of Catalina Good.)

If you’re signed up for my email list, you already know that we managed to hook Craig Good of Lucasfilm and Pixar fame as the voice artist for The Seventh Angel. Craig is every bit as talented behind the microphone as I am not. Known for his work on movies like Toy Story, Finding Nemo, Cars, and Monsters, Inc., Craig didn’t just narrate the book. He brought the crew of my fictional USS Towers to life. His performance was everything I hoped it would be, and more.

I listened to Craig’s recording tracks at least six times while the book was in pre-production, and now that it’s available for sale, I’m getting ready to download it from Audible.com so I can listen to it again.

Script and Control Board. (Photo courtesy of Catalina Good.)

Somewhere in the process, Craig talked me into recording the Author’s Notes myself. That sounded like a cool idea to me. Sort of like making a cameo appearance in my one of my own books. So he arranged some studio time for me, and presto! I was a star! Or… Maybe not so much…

The Sound Engineer doing his magic. (Photo courtesy of Catalina Good.)

Turns out that professional voice work is damned hard. And it also turns out that I have precisely no talent whatsoever in that particular arena. After many (as in countless) mumbles, false starts, and outright flubs on my part, the engineer eventually managed to piece together something vaguely intelligible from my lackluster performance. But it was very clear that I had no business behind the mike.

Craig where he belongs. (Photo courtesy of Catalina Good.)

The good news is, my so-called performance is only a couple of minutes long, and you can ignore it entirely without missing a single word of the actual story. But you’re not going to want to miss one second of Craig’s performance. It’ll knock you out of your freaking socks. (A bit like my dancing, but without the broken bones and contusions.)

The Seventh Angel audiobook is available now on Audible, and coming soon to Amazon and iTunes.

January 13, 2014

The Last Ship

A friend of mine pointed me to this trailer today…

It’s been a while since I read The Last Ship, by William Brinkley, but it looks like Michal Bay has sprinkled in some kick ass surface warfare action. (As a career tin can sailor, I’m morally obligated to watch any film that depicts U.S. Navy destroyers getting their whup-ass on.)

January 11, 2014

A Rendezvous With History

There’s a commonly-accepted saying in antisubmarine warfare… The best way to hunt a submarine is with another submarine.

Having spent the better part of two and a half decades chasing subs, training to chase subs, and thinking about how to chase subs, I’ve come to believe in the accuracy of that particular adage. As a career tin can sailor, I’d love to be able to say that the ultimate ASW platform is a U.S. Navy destroyer. That may have actually been true at certain points on the timeline of struggle between surface and subsurface warships, but for at least the last few decades, the balance in cross-boundary warfare has been tilted heavily in favor of submarines.

This (of course) raises an obvious question… What’s the second best way to hunt a submarine? Recently, I had a chance to lay hands on a piece of hardware that perfectly embodies the answer.

My wife and I were in Palm Springs a few weeks ago, and after driving past it several times, we decided to make a stop at the famous Palm Springs Air Museum. If you’re ever in the area, it’s a must-see. They have one of the largest collections of flyable World War II aircraft in the world, and you’re allowed to touch and examine most of the exhibits. For me, the biggest attraction was the PBY Catalina. It caught my attention from the street, and my eye was drawn back to it every time we passed within line-of-sight.

For those who aren’t familiar with this beautifully-ugly seaplane, it’s an enormous twin-engine flying boat, built by Consolidated Aircraft in the 1930s and 1940s. With a buoyant fuselage, hydro-dynamically sculpted for landing and taking off directly from the ocean, the Catalina served with every branch of the U.S. military throughout World War II. These planes saw countless tours of combat duty as patrol bombers, convoy escorts, search and rescue platforms, cargo carriers, and (need I say it?) sub hunters.

For those who aren’t familiar with this beautifully-ugly seaplane, it’s an enormous twin-engine flying boat, built by Consolidated Aircraft in the 1930s and 1940s. With a buoyant fuselage, hydro-dynamically sculpted for landing and taking off directly from the ocean, the Catalina served with every branch of the U.S. military throughout World War II. These planes saw countless tours of combat duty as patrol bombers, convoy escorts, search and rescue platforms, cargo carriers, and (need I say it?) sub hunters.

At their top-rated speed of about 196 miles per hour, the Catalinas were considered slow even at the outset of the war. And their sluggish performance rapidly lagged farther behind the power curve as innovations in aviation technology continued to accelerate.

Despite their lackluster flight characteristics, they remained in continual military service for more than fifty years. There were a handful of Catalinas in use by foreign militaries as recently as the late 1980s, and even now—eight decades after its initial test flights—the aircraft is still in use in aerial firefighting operations all over the world.

My own introduction to the Catalina occurred when I was about six years old. I was watching the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical South Pacific on television with my dad—generally ignoring the show tunes and story line while soaking up the 20th Century Fox Technicolor interpretation of the south seas islands—when the comically-cumbersome shape of a seaplane appeared on the screen. I was instantly fascinated by this odd-looking machine. Maybe it was because the Catalina bore so little resemblance to other planes that I was familiar with. Or maybe I was enthralled by the idea that such an unlikely contraption could skim along the surface of the waves and then jump into the sky and fly away. I don’t know what it was that captured my imagination, but I do know that my crayon drawings of aerial combat suddenly took on a new and unlikely star. In my Crayola depictions of battle, the lumbering bulk of the Catalina displaced the shark-like forms of my previous two favorites: the P-40 Warhawk and the P-51 Mustang.

My own introduction to the Catalina occurred when I was about six years old. I was watching the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical South Pacific on television with my dad—generally ignoring the show tunes and story line while soaking up the 20th Century Fox Technicolor interpretation of the south seas islands—when the comically-cumbersome shape of a seaplane appeared on the screen. I was instantly fascinated by this odd-looking machine. Maybe it was because the Catalina bore so little resemblance to other planes that I was familiar with. Or maybe I was enthralled by the idea that such an unlikely contraption could skim along the surface of the waves and then jump into the sky and fly away. I don’t know what it was that captured my imagination, but I do know that my crayon drawings of aerial combat suddenly took on a new and unlikely star. In my Crayola depictions of battle, the lumbering bulk of the Catalina displaced the shark-like forms of my previous two favorites: the P-40 Warhawk and the P-51 Mustang.

In later years, when I began to study the history of ASW, I was surprised to learn that my old friend the PBY Catalina was one of the earliest and most effective sub hunters ever built. Although historical accounts vary slightly on the exact numbers, Catalinas are known to have sunk at least 19 Japanese submarines in the Pacific theater, and somewhere between 35 and 50 German U-boats in the Atlantic. In all the decades before or since, the Catalina’s record has never been equaled (or even seriously approached) by any other antisubmarine aircraft. This is especially impressive when you know that German U-boats were well-armed with anti-aircraft guns by 1943, and that many of the Catalina’s kills were the result of brutal shootouts with the submarines they were hunting.

All of these facts and childhood memories were swirling around in my head as we bought our tickets to the Palm Springs Air Museum, and made our way through the display hangars to the outdoor runway exhibits. We strolled past an F8F Bearcat, an F4U Corsair, a B25 bomber, an ex-Soviet MiG-21, and so many amazing warplanes that I literally lost count. We eventually went back and looked at the other planes, but I had really come to see the Catalina.

There she was, sitting on the concrete under the bright California sun. A great whale of a seaplane: dented, oil-stained, and showing every minute of her seventy-plus years. She was every bit as ungainly as I’d imagined, and she was utterly beautiful.

I laid my palm on the battered sheeting of her curved fuselage and felt the history of this magnificent old war bird seep through the sun-warmed metal into my fingers. I wished she could tell me about the things she had seen; the eight-man crews who had flown her into action; the countless thousands of miles that had scrolled beneath her salt-flecked wings. Unfortunately, the old girl’s powers of speech were limited to the words printed on the museum placard, and the aura of bygone adventure that I soaked up while standing in her presence.

I can’t say that I came away from the encounter with more wisdom or knowledge than I walked in with. Nor can I claim to have been fundamentally altered by a few minutes of quiet communion with an aging aircraft. But I have changed my mind about one small point. I no longer buy into the idea that the best way to hunt a submarine is with another submarine. As far as I’m concerned the best way to hunt a submarine is with a preposterous old seaplane, covered in oil-stains, and reeking of unspoken history.

This is a flat contradiction of accepted tactical wisdom, but I know that I’m right. Just give me a blank sheet of paper and a box of Crayolas. I can prove every word.

January 1, 2014

Silver Screen Leadership

Lately, I’ve been itching to re-watch Crimson Tide, a 1995 submarine warfare movie directed by Tony Scott. If you haven’t seen this film yet, you should definitely add it to your Netflix queue. Gene Hackman plays the commanding officer of a U.S. ballistic missile submarine on a nuclear deterrence patrol during a military coup in post-Soviet Russia. Denzel Washington portrays the submarine’s new executive officer, brought aboard at the last minute because the assigned XO is medically unfit to deploy.

After some quick buildup and a bit of character development, the sub receives an authenticated Emergency Action Message, ordering the crew to launch nuclear missiles against a Russian missile installation that’s fallen into the hands of the bad guys. The tension is absolutely palpable as the CO (Hackman) and XO (Washington) go through the preparatory steps for firing the first shots of World War III.

This is scary/exciting by itself, but the real conflict heats up when the sub receives a second Emergency Action Message that gets chopped off in mid-transmission. The XO interprets the fragmentary second message as an order to abort the missile launch. The CO insists that operational doctrine requires him to disregard unauthenticated or fragmentary messages. He orders his missile crew to continue the attack. The XO refuses to confirm the order, and the movie’s true battle is joined. The ensuing confrontation escalates into mutiny as two military leaders—each convinced that he’s operating lawfully and in the best interests of the United States—wrestle for command of the submarine and her payload of nuclear destruction.

It’s a hell of a good movie. Amazing human drama in a pressure-cooker environment where the stakes are (quite literally) the future of the entire world. The acting is brilliant; the production values are top-notch, and the action is pure adrenalin.

As you’ve probably gathered, I’m a big fan of Crimson Tide. I saw it twice in the theater and it’s been a treasured part of my movie collection since it was first released on home video. But despite all of its good points, the movie completely drops the ball in one important respect. The filmmakers couldn’t resist overinflating the heroic qualities of Denzel Washington’s character. As a result, the contributions and sacrifices of the submarine crew are marginalized to the  point of invisibility. The real heroes of the story are pushed so far into the background that they become scenery.

point of invisibility. The real heroes of the story are pushed so far into the background that they become scenery.

This is illustrated clearly by a scene which occurs prior to the showdown with Gene Hackman’s character. When a fire breaks out in the submarine’s galley, Denzel’s character rushes directly to the site of the blaze, pausing only to grab an oxygen breathing apparatus and flash hood along the way. Breathing mask in place, he arrives on scene, where he elbows his way past the damage control team. These men know their boat intimately, and they’ve practiced for variations of this scenario at least a hundred times. But somehow, these trained firefighters bungle about like confused preschoolers until their brand new XO shows up to hit the button that dumps carbon dioxide on the fire, bringing the emergency to an end.

Something similar occurs later in the movie, when the sub’s radio transceiver is damaged at a highly inopportune moment. Denzel’s character goes down to personally supervise the troubleshooting effort. The subtext of the scene is unmistakable… The technician cannot hope to repair the damaged equipment without a pep talk from his executive officer. Forget the fact that the tech has months (or years) of detailed technical training. Forget the fact that the XO probably can’t tell a diode from a capacitor. The important work can’t get done until the hero shows up to put his magic blessing on things.

I’m not complaining about lack of accuracy. I have no problem with artistic license in the telling of a story. Tony Scott wasn’t directing a documentary, and I certainly don’t expect to see anything approaching realism in a summer blockbuster.

I’m also not talking about on-screen heroics. I enjoy it when the main character rolls up his or her sleeves and kicks some ass. What bothers me is the notion that the ordinary crew members are almost irrelevant to the story.

Does this oversight destroy the movie? Not for me it doesn’t. I own Crimson Tide on Blu-ray, and I had a copy on DVD before that. As I mentioned earlier, I’m a big fan of this film. But I wish the filmmakers—and Hollywood in general—would make an effort to highlight the heroism of the deck plate Sailors. They’re the true heroes of the story, whether the camera is pointed in their direction or not.

December 23, 2013

The Hero Recipe

Believe it or not, there’s a recipe for creating heroes. It’s a bit like the Colonel’s secret recipe for Kentucky Fried Chicken, but without the eleven mysterious herbs and spices. Also, it’s not a secret. With minor variations, the recipe has been in common use for centuries, but it works just as well today as it did for the Ancient Greeks.

Take one adult person (usually male), mix in stunning good looks, superb physical conditioning, amazing technical capabilities, keen personal insight, and combat skills that border on the supernatural. Pour the entire mixture into a larger-than-life mold and bake at 425 degrees until your oven begins to whistle the title theme from any Chuck Norris film. Garnish with undying courage, a healthy dash of rebelliousness, and the kind of sexual magnetism that makes members of the opposite gender forget where they put their car keys.

Voilà! You’ve got yourself a hero. A well-muscled paragon of kick-assery who can fight like Jet Li, shoot like a world class sniper, and buck the entire system to get the job done—despite the ineptitudes and interferences of the clueless yahoos in his chain of command. (I say ‘his,’ because something upwards of 95% of the heroes created using this recipe are endowed with a Y chromosome.)

Voilà! You’ve got yourself a hero. A well-muscled paragon of kick-assery who can fight like Jet Li, shoot like a world class sniper, and buck the entire system to get the job done—despite the ineptitudes and interferences of the clueless yahoos in his chain of command. (I say ‘his,’ because something upwards of 95% of the heroes created using this recipe are endowed with a Y chromosome.)

If you’re worried that your hero is a little too perfect, you can scuff the corners a little, as a salutary nod toward ordinary humanity. This may take the form of a few masculine scars, a tarnished reputation from some past failure that must not be repeated, or a negative personality trait that has to be overcome before he can reach his full potential. Such imperfections only need to be a single layer deep. When you scratch below the surface, it’s perfectly okay if the true perfection beneath is revealed.

Of course, this recipe doesn’t work very well in real life, but it works like clockwork in fiction. I’ve seen hundreds (or even thousands) of examples in popular movies and novels. Chances are, you’ve encountered them just as often as I have. Countless manifestations of the two-fisted swashbuckling loner who downs his whiskey straight, charms supermodels out of their designer lingerie, and snatches victory from the proverbial jaws of defeat—usually when there are about three seconds remaining on the doomsday clock countdown.

It may sound like I’m disparaging the time-honored hero archetype, but I’m not. I’m a lifelong fan of heroic characters like James Bond, Travis McGee, Dirk Pitt, Jack Ryan, Ethan Hunt, and Indiana Jones. I love those guys.

Even so, I have to wonder why such a disproportionate percentage of fictional heroes are male. Yes, I know there are a number of heroic female characters, but for every Lisbeth Salander, Ellen Ripley, and Laura Croft, there seem to be a hundred James Kirks and John Rambos.

And why do they always seem to be lone wolf types? Why do so many authors and screenwriters assume that heroes must be rogue warriors who work outside of the boundaries of the established system?

Again, I’m not knocking the hero recipe. It works. It’s fun. I’ve turned innumerable pages and munched many (many) bags of overpriced theater popcorn as larger-than-life heroes have punched, shot, and charmed their ways to victory. But these are not the kinds of heroes I’ve come to know and appreciate. In 23 years of active duty and a couple of tours of combat, I never met anyone resembling Jack Ryan, or John Rambo, or Ethan Hunt. Not once.

This begs the question, where were those guys? When there was work to be done, and an actual mission to be accomplished, the archetypical heroes were conspicuously absent. And I can tell you that they were damned well not around when the shooting started.

Instead, I saw a different kind of hero. I saw ordinary men and women who worked together to accomplish extraordinary things. Most of them weren’t tall and blindingly attractive. Their only superpowers were cooperation, dedication, and skill born of training, experience, and personal effort.

Faced with an imperfect system, they didn’t abandon military discipline, or put themselves outside of the chain of command. They figured out how to accomplish the mission anyway, despite unclear orders, faulty equipment, and rules of engagement that often made their jobs many times harder than they should have been.

I’m no longer surrounded by these unacknowledged heroes on a daily basis, but they’re still out there. They’re still doing the job every second of every day, often in places you’ve never heard of, under conditions that most people can scarcely imagine. Week after week, year after year, they risk their lives for a citizenry that rarely recognizes or appreciates their sacrifices.

These are the quiet warriors. The ones who never seem to make it onto the movie screen or the bestseller list. They’re not products of the ancient hero recipe. They’re not flashy. Most of them don’t have six-pack abs and biceps of steel. They’re not imbued with astonishing abilities. They’re the real thing.

When I set out to start writing novels about the military, I decided to acknowledge and celebrate the kind of collective heroism that actually keeps this country safe and strong. I promised myself that the men and women who populate my stories wouldn’t look or act like Tom Cruz or Angelina Jolie.

I’m doing my best to keep that promise. When you open one of my books, the heroes you find will look a lot like your daughter, or your nephew, or that twenty-something kid standing in front of you in the supermarket checkout line. And if you happen to wear the uniform yourself, some of my heroes probably look quite a bit like you.

November 19, 2013

Auto-Responders and the Hotel Room of Doom

Dear Corporate America:

Auto-responders are not always your friend. If you remove human intelligence from your communications loop, the results of your (no doubt) well-intentioned correspondence can end up making you look like idiots.

Case in point…

During a business trip early last year, I stayed at the worst hotel it’s ever been my misfortune to encounter. In the interest of keeping this blog on a polite footing, I won’t identify the festering pit hotel as the Days Inn in Yuma, Arizona. (Or maybe I will.)

What was so bad about it? Let me count the ways…

Torn bed sheets.

Colonies of mildew on the ceiling. (I think it was mildew. If not, I don’t want to know what it was.)

Broken shower head hanging out of the wall.

Cracked fiberglass in the shower stall.

Smears of some ugly brown substance on the wall. (I never figured out whether it was blood, feces, or something else. Either way, the ick factor is pretty much through the roof.)

That ain’t all, but you get the general idea.

Just the act of walking into the room made me feel like I needed a tetanus shot. But it was the end of a very long day, and I was too exhausted to go hotel shopping. I decided to risk one night in the room of doom.

I had reservations for a week, but I checked out the next morning to search for cleaner accommodations. The desk clerk inquired politely about my early departure, so I told him about the conditions in the chamber of secrets. I also showed him a few snapshots I had taken of the room’s unadvertised amenities. I thought the clerk might offer to move me to a room with fewer health hazards, but he just wished me safe travels, so I smiled and departed. I found a nice hotel at the same rate a few blocks away, and finished my business trip in peace and comfort.

That probably would have been the end of things, but then the auto-responders starting pinging me. First, I was invited to participate in an online survey, to rate my experience as a recent guest of Days Inn. No problem, so far. Here was a chance to let the nice people at Days Inn know that they had some issues in Yuma. I gave the hotel bottom marks for cleanliness, materiel condition, maintenance, and just about everything else. I believe I gave a passing grade for friendliness of the staff. Their complete unconcern about room conditions aside, they had seemed polite to me. In the comments section of the survey, I described my stay as the worst hotel experience of my life. I explained that I had checked out four days early, because I wasn’t willing to risk a second night in that roach trap. I probably said something about never staying at a Days Inn hotel again. I even offered to provide photos of some of the room’s more egregious problems, as a guide for improvement.

I halfway expected to receive an apologetic email from Days Inn Customer Service sometime in the next few weeks. I didn’t get one. No big deal.

What I did get was an auto-responder message, telling me that Days Inn was delighted to hear that my recent stay had been such an overwhelmingly pleasant experience.

A few weeks later, I got another auto-responder, congratulating me for being a loyal Days Inn customer, and promising me similar superb hotel stays in the future.

It’s been nearly a year since I informed Days Inn that my experience with their chain ranks just about on par with sleeping on the floor of a gas station restroom that hasn’t been touched by Lysol since the Reagan Administration. At some point, given the extremely negative nature of my feedback, you might expect a bit of intervention by some person capable of recognizing that I am the absolute antithesis of a satisfied customer. But their auto-responders continue to treat me like an undying fan of the Days Inn hotel chain.

A couple of hours ago, I received another chirpy auto-response, cheerfully reminding me that it’s time to book my Days Inn reservations for the holidays. As auto-spam goes, it’s actually a very festive email, complete with a heartwarming picture of Grandma and three generations of family gathered around a food-laden table while Grandpa carves a plump Thanksgiving turkey. (I didn’t notice any smears of blood or excrement on the walls, but those features were probably cut off by the camera frame.)

I’d like to close with three thoughts for the people at Days Inn, and their brethren in corporate America.

First, if you’re going to go to the trouble of asking for customer feedback, you might want to actually read what the customer has to say.

Second, if your software blithely assumes that all customer interactions are positive, you’re going to make yourself look stupid.

And third, I really do have pictures. Let me know if you want to see them.

Happy Holidays, and watch yourself in that shower. It’s not pretty in there.