Brandon Stanton's Blog, page 102

October 24, 2018

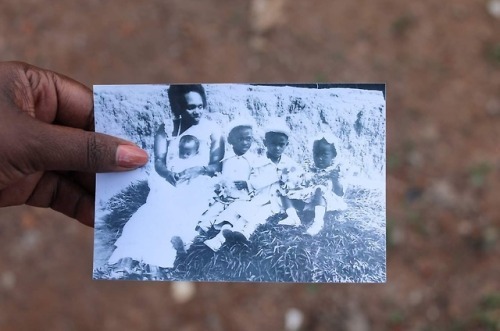

(1/9) “My father was well respected in the community. He...

(1/9) “My father was well respected in the community. He was a university lecturer and a choir member. But he was always working, so my mother was primarily the one who raised us. Her name was Consolee. She had this deep sorrow about her. She was an orphan because her parents had been killed in the 1963 genocide. Whenever we asked her to tell the story of our grandparents, she’d just say: ‘Give it time. Soon you’ll see for yourself.’ I tried to help her as much as I could. The eldest daughter acts like a mother in our culture, so I raised my six younger sisters. They thought I was too strict. They were always saying that I behaved like a nun. But they looked up to me too. And they loved me. Occasionally I’d help to keep them out of trouble. When my sister Francine cut her foot on a bottle, she was terrified to tell our mother because she wasn’t supposed to be barefoot. I helped her conceal the crime by cutting a hole in the bottom of her shoe. At night all my sisters would pile into my bed. They’d beg me to tell them stories. And I always did, until they fell asleep, and I’d carry them into their beds one by one. The youngest was a boy. He always took the longest because I had to rock him to sleep. His name was Edmond Richard, but we called him ‘Bebe.’ He was was 1.5 years old when the genocide began.”

(Butare, Rwanda)

October 23, 2018

(6/6) “I was given the opportunity to visit Rwanda as part of...

(6/6) “I was given the opportunity to visit Rwanda as part of my internship with the US Senate. I was accompanying an important delegation. But they must have thought I was crazy, because when we arrived in Rwanda, I began speaking to people in the streets. I was convinced that everyone looked like me. I wanted to find members of my family. I wanted to see my old school. I wanted to find my old house. But all I could remember was the location of my grandmother’s house because it had been so close to the airport. So that’s where we went. We knocked on the door. I didn’t reveal my identity. When I asked the current resident if he knew about me, he told me that I had been killed. But then he said that some of my family was still alive. He told us that my sister was working at a nearby market. So we decided to drive there. The sun was going down. At this point I was sure that I’d lost my mind. Because we drove by a playground, and I saw a little boy that looked exactly like me. I even took his photo. I had no idea that he was my brother. When we arrived at the market, it was almost completely dark. But I saw my sister. And she saw me. She recognized me immediately because of the scar on my forehead. Our brother had given me this scar when we were toddlers. He didn’t survive the genocide. When my sister saw me, we embraced. We both started crying. And she told me everything that happened while I was gone. And I won’t share the details, because those aren’t my stories to tell. But she gave me the biggest news of all. I remember picking up the phone, and immediately calling Anne Peterson. I told her: ‘Mom, you’re not going to believe this. But I just found my mother.’”

(Kigali, Rwanda)

———————————————–

If you are wondering why Nyanja is back in Rwanda, it’s because she has founded an organization called Little Hills, which aims to improve health services for children in Rwanda. Her ultimate goal is to build a children’s hospital. She’s created a small fundraiser, which I’ve kicked off with a $5,000 donation from the HONY Patreon. If you’d like to empower Nyanja in the next phase of her life, and help improve healthcare for children in Rwanda, you may do so here: https://bit.ly/2PR1BXN

(5/6) “During high school I got a lot of counseling. I began...

(5/6) “During high school I got a lot of counseling. I began to process what had happened to me. I remember in tenth grade we had an English teacher who used to tell us to look in the mirror every morning and say: ‘I’m good and I’m beautiful.’ But I would always add: ‘And I’m extremely lucky.’ I’d look at myself closely and try to recognize my mother. I started reading a lot of books. One of them was called Anne of Green Gables, about an orphan girl who was different. I decided that I was going to be like Anne and not let my bad luck ruin my life. I went to college at Washington State. I got an internship to work in the US Senate. I even dreamed about one day becoming Secretary General of the United Nations. But it was during this time that I also began to meet other people who’d escaped from Rwanda. I listened to their stories. And I began to realize the full context of what happened during the genocide. I read about it obsessively. I learned that the world had abandoned Rwanda. The United Nations may have saved me, but they failed everyone else. One million people were left to die. At first I felt angry. Then the anger turned into guilt. Why had I survived? For the longest time I didn’t even want to tell my story. Because I didn’t want to give the United Nations any credit. I didn’t want my story being used to put a positive spin on the situation. I felt confused and conflicted. But then at the age of twenty-one, I was given an opportunity to return to Rwanda.”

(Kigali, Rwanda)

(4/6) “After a year we were chosen for resettlement in the...

(4/6) “After a year we were chosen for resettlement in the United States. As soon as we arrived, I was separated from my grandmother. She was put in a nursing home, and two months later she passed away. It was the first time I’d cried since I left Rwanda. She was all I had left. I lived with my uncle for awhile but he was very abusive. He treated me like a maid. So I was removed from the home and put into foster care in Boise, Idaho. But that was also a bad situation. I was on the verge of running away. And I’m pretty sure my social worker informed my school. Because my art teacher started asking me about my plans. Her name was Anne Peterson. She was one of those teachers that you could talk to about anything. So I answered all her questions. I told her my story. And I started bragging about my plan to take care of myself. I think she decided: ‘Absolutely not.’ Because that’s when she chose to become my Mom. Oh my God, it was amazing. Ms. Peterson lived in a big, beautiful house. I was the only child there. I had my own room. It was safe. I didn’t have to worry about surviving. Mom took care of everything. She would wake me up to go to school every day. She always made sure I had lunch. She took me out to eat at restaurants. It was amazing. I was already fifteen years old. But for the first time in years, I felt like a kid.”

(Kigali, Rwanda)

(3/6) “The plane took us to a refugee camp in Nairobi, Kenya....

(3/6) “The plane took us to a refugee camp in Nairobi, Kenya. It would be our home for the next year. When I finally learned what was going on, I became one hundred percent convinced that my mother had been killed. Other refugees were telling me stories. Many of them had lost their entire families. My uncle told me that everyone in our neighborhood had been captured, and he was almost positive that my mother was dead. Surely if my mother was alive, she would have come for me. My grandmother’s house was not far from our home. So I accepted the truth. But I didn’t have much time to think about it. Because we had to fight for survival in the refugee camp. My grandmother was paralyzed and couldn’t chew hard food. So I’d spend my days trying to find her things to eat. I’d negotiate with people for their eggs and bananas. I spent the rest of my time by her side. She couldn’t move so I had to keep the flies away. But it wasn’t all bad. I made friends with a few of the other kids in camp. And I remember one time we stole money from the adults. We snuck out of the camp and bought French fries from a roadside shop. They were horrible quality. They came in a little plastic bag. But at the time I remember thinking they were the best thing I’d ever tasted.”

(Kigali, Rwanda)

(2/6) “We stayed in the house for two nights. On the third...

(2/6) “We stayed in the house for two nights. On the third morning a neighbor warned us that the killing groups were coming our way, so we decided to leave without packing anything. We were fortunate because my grandmother lived right next to the airport. Her house backed right up to the airstrip, and it was one of the few places in the city still under the protection of the United Nations. So my uncle cut a hole in the fence, and we began running toward some old trucks. We couldn’t run very fast because we were pushing my grandmother in her wheelchair. On the way I lost one of my yellow flip-flops. I remember thinking: ‘My mother is going to kill me when I see her again.’ So I tried to turn back, but the adults screamed at me to keep running. Finally we reached one of the old trucks and climbed beneath it. We stayed under that truck for a week. The UN knew we were there, but they left us alone. Occasionally I’d run out and ask the soldiers for food. There was one soldier in particular who always gave me biscuits and sardines. He felt sorry for me because I was so small. And when the UN finally evacuated, he came and got us. They put us in the back of a cargo plane with some containers. Nobody explained anything to me. I was cold. I was hungry. I was tired. All I wanted to do was go home and see my mother.”

(Kigali, Rwanda)

(1/6) “I was only ten years old at the time so I don’t...

(1/6) “I was only ten years old at the time so I don’t remember much. Nobody explains things to you when you’re a child. I was never told that I was different. Or that some people wanted to kill us. My mother basically raised me by herself, but it wasn’t an unhappy childhood. I do remember feeling afraid sometimes. I remember occasionally being kept home from school. And I remember not being allowed to play freely in the streets. But these things were never fully explained to me. When the genocide began, I was visiting my grandmother. It was a school holiday. I’d made good grades that semester, so my mother had bought me a pair of yellow flip-flops as a reward. I was obsessed with them. I remember waking up that morning and realizing something strange was going on. I could hear gunshots outside and people screaming. My grandmother told me to stay inside the house. She’d recently had a stroke and was confined to a wheelchair, so it was just me and her alone in the room. Eventually I got bored and decided to sneak outside to see what was happening. All the streets were empty except for young boys with machetes. That’s when my uncle came over, and I overheard him telling one of the maids that it was extremely dangerous outside. He said that all of us might be killed.”

(Kigali, Rwanda)

October 21, 2018

(3/3) “When I woke up, I found myself lying alongside a very...

(3/3) “When I woke up, I found myself lying alongside a very deep pit. It was full of bodies. My stepfather was standing over me. Somehow he had learned about the attack, and had come with his bodyguards to rescue me. He picked me off the ground. I was barely conscious. When we returned home, my stepfather called the government to complain about what had happened. But he was told to watch his back. He was told that our family was no longer under protection. My mother begged me stop helping people. She told my bodyguards to not let me leave the house. But by that time the Rwandan Patriotic Front was getting very close to our village. The fighting grew very intense. My family packed everything and fled toward the border with Congo. Four of my sisters were killed on the journey. I remained behind with the seventy people. Our bodyguards were gone. We were helpless. We had no guns. We just prayed the rebels would liberate us as soon as possible. I knew the killing groups would be coming to my home, so I gathered all the remaining biscuits and water. I took everyone to the house of someone who had already been murdered. It seemed like the safest place to be. I closed them inside and padlocked the door. Then I finally ran off to reunite with my family. I learned later that everyone in that house was rescued. Only four of the seventy lost their lives. And almost all of them are still alive today. We remain friends. We’re still neighbors. They bring me gifts. I see them in the streets almost every day, and whenever we meet, they show me their love.”

(Kigali, Rwanda)

2/3) “The killings were being encouraged by the national...

2/3) “The killings were being encouraged by the national radio station. Every day they would announce how many people had been killed. They’d announce the location of the killings. And they’d give thanks to those who were doing the killing. One morning I was sitting in my bedroom, and I heard an announcement on the radio: ‘Everyone is being killed in Gatobotobo except for those under the protection of the Felix family.’ I knew then that we were in danger. Not long after the announcement, the Minister of Internal Security came to our village for a meeting. It took place on a hill overlooking our property. He could see everything that was happening in our compound. When he left the meeting, his convoy began driving toward our home. The minister was riding in a truck full of armed soldiers. When he passed by me in the street, the truck slammed on the brakes. All my bodyguards ran away and I was left completely alone. My neighbors began to gather around. They were laughing and applauding and saying, ‘This is the guy who was stopping the killings.’ The minister walked over to me. He pushed me on the ground and leaned over my body. He was covered with sweat. His eyes were wide. There was dried spit on the edges of his lips. He had the face of the devil. He took off his belt and began beating me until I lost consciousness.”

(Kigali, Rwanda)

(1/3) “The genocide was an opportunity to get rich....

(1/3) “The genocide was an opportunity to get rich. Murdering people was the quickest way to accumulate wealth. We were given permission from the government to seize the property of anyone we killed. We were told it was our god given right. But I never felt the temptation. My family owned a very big supermarket. I had my own car. When the killings began in 1994, I had a scholarship to study in Greece and I was just waiting to begin university. My stepfather was Vice President of our region, so we had four bodyguards in the house. These guys were highly trained with automatic weapons. They became good friends of mine. I’d take them to the bar every night. I’d drive them around and buy them anything they wanted. They were also good human beings. One night over drinks we discussed the genocide, and all of us decided: ‘We’re going to put an end to this in our neighborhood.’ The next morning I woke up to my neighbor screaming. I looked out the window and saw that he’d been surrounded by a mob with machetes, and was bleeding badly from the head. I’d been friends with him since childhood. So I sent my bodyguards to save him. The machetes were no match for our guns. Word spread quickly after that. Tutsi families came to our compound seeking refuge. I took long walks with my bodyguards every morning, looking for people to save. We drove to surrounding farms and searched the fields for survivors. At one point we had seventy people under our protection. Nobody challenged us. I was young and cocky. I thought we were untouchable.”

(Kigali, Rwanda)

Brandon Stanton's Blog

- Brandon Stanton's profile

- 769 followers