Tyson Adams's Blog, page 24

May 12, 2019

Book vs Movie: The Little Mermaid – What’s the Difference?

[image error]

This month’s What’s the Difference? from Cinefix looks at the classic children’s story that became a(nother) Disney movie.

My memory of The Little Mermaid story is what you would call hazy. The Hans Christian Andersen tales, from my recollection of them, were a lot darker and nastier than would generally be acceptable for young children these days.

The movie is much easier for me to recall, as my daughter has recently taken a liking to the tale. Except for the bits with Ursula in them, which are far too scary. Fortunately, I’m usually on hand for hugs during those scenes.

The thing that has struck me the most about The Little Mermaid, and Disney kids films in general, is how much they have progressed in the last 30 years as compared to the 30 years prior. Several of the Disney films released in the 70s and 80s (The Little Mermaid, The Fox and the Hound, The Aristocats, Winnie the Pooh) bear a lot of similarities to earlier films (101 Dalmatians, Lady and the Tramp, Bambi*). The leap that was made after Toy Story is profound, such that newer films are just in a whole other league (Tangled, Frozen, Zootopia).

Almost as big of a leap as children’s book have made since Hans Christian Anderson was writing.

The source material behind Disney’s animated classic, Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, is a surprisingly metal fairy tale. Let’s take a look at all the ways the filmmakers changed the source material, talking crabs and all! It’s time to ask What’s the Difference?

* But not Dumbo. That film has aged badly. There is a lot to cringe at in Dumbo and the film itself climaxes with a very short scene, so it feels a little underdone.

May 9, 2019

Book review: The Boys by Garth Ennis

The Boys Omnibus, Volume One by Garth Ennis

The Boys Omnibus, Volume One by Garth Ennis

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

The words you don’t want to hear from someone with superpowers: Because I can.

The Boys series by Garth Ennis shows us a world where superheroes are a marketing gimmick for a military-industrial company – Vought America – and these all-powerful beings – such as The Homelander – have to be kept from overindulging in hedonism, vice, and collateral damage. But there is more at stake, as Vought scheme and The Homelander plots.

It was interesting to revisit this series 7 years later as the TV series is set to commence. I remember enjoying the series for its interesting take on superheroes. Much like Irredeemable and Incorruptible, The Boys tries to imagine a more realistic scenario for how people with superpowers would behave. This gives Ennis a chance to pour in his trademark nudity, sex, violence, and toilet humour.

But underneath that facade is a much more interesting story. The Boys team are comprised of trauma victims who (mostly) have interesting story arcs. The superheroes are portrayed in a way that feels much truer to life; especially if you take them as a stand-in for actors, models, rich socialites or the like and the shady stuff we know they get up to. The political and business machinations throughout stands as a cautionary tale. And the series is pretty much one big swipe at the military-industrial complex.

I think I appreciated the depth of this series more on the second read. The Boys is worth reading, especially if you’ve seen other Ennis comics and ever wondered what he really thinks of superheroes.

A quick comment on the TV show: I’m hoping the series is good. From the trailer, it appears they’ll be doing some things a bit differently to the comics, notably The Homelander’s personality and the more prominent corporate criticism. Karl Urban, Antony Starr*, and Elizabeth Shue are great actors, so just their presence should make it worthwhile.

* Antony was the lead in the criminally underappreciated Banshee. If you haven’t watched that series, do so.

May 7, 2019

How does it end?

May 2, 2019

The Week

This is fantastic. I also like the irony of posting this on a Friday (Thursday for many of you, since I’m in Australia).

Check out Lunarbaboon and buy his stuff.

April 30, 2019

Respect for genre

I’ve previously written about how some literary authors don’t really understand nor respect genre fiction. Of course, that doesn’t appear to give them pause before sitting down with their quill and parchment – literary authors exclusively use olde timey equipment: true fact – to knock out a genre novel. Their attempts at writing genre tend to reflect this disdain and ignorance of the form, and they end up doing a poor job of writing it.

Enter the nineteenth most powerful person in British culture, Mr Ian McEwan, an author so influential that Simon Cowell ranked higher on that list. He – Ian not Simon – recently made headlines for his comments about science fiction.

[image error]Source

Well, at least we know he’s treading on well-worn paths and reinventing all the tropes he’s painfully unaware of with his latest novel. But good on him for flying the ignorance flag so high so we don’t waste our time as readers.

It gets better. I received the monthly recommended review books from Penguin and saw McEwan’s new novel, Machines Like Me, on the list. This was the publisher’s blurb:

Our foremost storyteller returns with an audacious new novel, Machines Like Me.

Britain has lost the Falklands war, Margaret Thatcher battles Tony Benn for power and Alan Turing achieves a breakthrough in artificial intelligence. In a world not quite like this one, two lovers will be tested beyond their understanding.

Machines Like Me occurs in an alternative 1980s London. Charlie, drifting through life and dodging full-time employment, is in love with Miranda, a bright student who lives with a terrible secret. When Charlie comes into money, he buys Adam, one of the first batch of synthetic humans. With Miranda’s assistance, he co-designs Adam’s personality. This near-perfect human is beautiful, strong and clever – a love triangle soon forms. These three beings will confront a profound moral dilemma. Ian McEwan’s subversive and entertaining new novel poses fundamental questions: what makes us human? Our outward deeds or our inner lives? Could a machine understand the human heart? This provocative and thrilling tale warns of the power to invent things beyond our control. Source.

Yes, it even has a love triangle. This is certainly not a bog-standard sci-fi novel at all. No sir. This explores big ideas… This is the cover art…

[image error]Looks very professional. Not a first attempt at self-publishing nor creepy at all.

There are several potential explanations here:

McEwan is one of the arrogant literati who would never stoop to reading such crass material as genre fiction. Of course, when they write it, it is very important literature that you should absolutely buy and praise them for writing it.

McEwan is painfully ignorant to the point that someone really should have taken him aside during the (above quoted) interview and shown him the Wikipedia page for Science Fiction on the magical communication box they carry in their pocket.

McEwan is hoping that his comments will stir controversy that will help sell more copies of his books.

Now I am a bit late to the internet pile-on that inevitably results from modern faux pas as it is reactionary and lowers the quality of discourse. Definitely not because I got distracted on other things. Anyway, the reason why I have come back to this incident is that it ties into a thread I have been commenting on for several years now: Literary snobbery, or the Worthiness argument.

People like to think of the difference between genre and literature as akin to the difference between entertainment and art. Because no art is entertaining. Some have suggested the difference is in the plot-driven versus character-driven narratives. This doesn’t hold up to much scrutiny, as some call literature just another genre, and others have suggested it is more about genre being built on structure. A lot of people will also exclaim, “I know it when I see it.” But this ignores the reality that literary merit is a spectrum.

But the most interesting argument I have seen defining the difference between literature and genre fiction was around the class divide. The snobbery was literally built into the divide because genre stories were published in cheaper books for the workers and the more literary stories were published in fancier books for the new middle class.*

So it is quite possible that the reason why we have comments like McEwan’s is because they are tapping into 150 years of class snobbery that disallows them from reading or appreciating genre fiction. If they do read some, it will be classed as a guilty pleasure, because they can’t be seen actually acknowledging genre as having substance.

Or it could just be about attention seeking to sell some books.

* The argument doesn’t really discuss what rich people read. I assume that the rich people were too busy counting money to be bothered reading either genre or literature.

April 28, 2019

Book Review: The Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord

The Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord

The Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

“Quotations are useful in periods of ignorance or obscurantist beliefs.”

The Society of the Spectacle is an aphoristic set of polemic essays that examines the “Spectacle,” Debord’s term for the everyday manifestation of capitalist-driven phenomena; advertising, television, film, and celebrity. He argues that we have become alienated from ourselves and reality in order to have us serve the economy/capitalism with the production of commodities and accumulation of wealth.

I first encountered the idea of the Spectacle from Peter Coffin (see below) and his video essays related to what he terms Cultivated Identity. This is a fascinating idea and particularly relevant today in the age of mass media, late-stage capitalism, and the commodified zeitgeist. Look at how much of our society is obsessed with or based upon edifying upward mobility, celebrity, fame, reputation, and positions of power or prestige.

This ultimately means that our media has become what tells us how to think and it is essentially inescapable within our modern society. Thus, the limits of our conversations and thinking have already been defined, which then becomes a feedback loop for the media we consume. Click “Like” if you already agree.

The only drawback of this work was that it is obscurus and jingoistic. Aphorisms might be cool for ancient philosophers, but they don’t make for great enlightenment nor clear communication of ideas. I’ve actually gained more from reading and watching related overviews of The Society of the Spectacle than from Debord’s actual work.

Wikipedia

Illustrated Guide to Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle

Super Summaries

Peter Coffin’s video essays on the Spectacle:

Discussion of the Spectacle by a philosopher:

And her blog post on it: https://dweeb.blog/2018/12/21/the-society-of-the-spectacle/

An audiobook in Spectacle form:

April 25, 2019

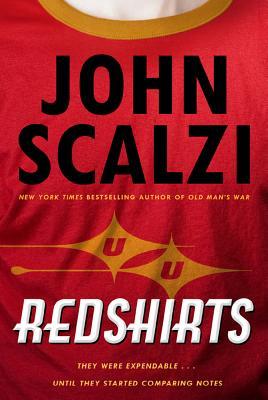

Book Review: Redshirts by John Scalzi

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Sometimes you can create characters that are a little bit too realistic.

Ensign Andrew Dahl has just been assigned to the Intrepid as a xenobiologist. But from his first day onboard he notices that something is wrong with the rest of the crew. He and his fellow new recruits quickly realise that people on away missions have a nasty habit of dying. Except for a select handful of important crew members that is. They also notice that reality doesn’t make much sense at times when The Narrative takes over. Can Dahl and his friends figure it out before an away mission kills them too?

After reading the first chapter of Redshirts I had to consult with the interwebz to answer a question about this book: Is it worth reading the whole thing? Aside from one notable review that captured several of my concerns, the vast majority of my fellow readers loved Scalzi and this book. So I decided to persist and found myself at the end of Redshirts with the same reservations as I had at the end of the first chapter.

Firstly, this book was good enough to keep me reading. Redshirts has a very strong premise and the story is mostly well executed. The main story – more on the codas in a minute – steams along and is pretty entertaining. It won a Hugo, so clearly it has a lot to offer.

Now, let’s get to the buts.

For what is clearly a comedic novel, Redshirts is nowhere near as funny as it thinks it is. He said. He said. It has a cast of characters that are meant to be shallow and interchangeable, but they are so interchangeable that you wouldn’t know who was talking if you weren’t constantly reminded. He said. He said. The premise may be very strong, but I felt it wasn’t fully realised, which left me frustrated. And then the three codas arrived and shifted away from the previous 25 chapters’ lighthearted tone. All three, but especially 2 and 3, had a much more serious tone and felt like they belonged in a different novel.

So while I mostly enjoyed reading Redshirts, I feel it wasted its premise and wasn’t as well executed as I’d have liked.

NB: My wife said I had to tell everyone that I’ve spent all day complaining about the ending to Redshirts. She feels it would be disingenuous of me not to mention that and to also give you an idea of how much she is looking forward to me reading something else.

April 23, 2019

The Beauty and Anguish of Les Misérables!

[image error]

It’s Lit! returns to discuss Les Miserables.

Yeah, I haven’t read it, nor seen the musical nor the musical movie. A title that literally means the miserable and a narrative to match isn’t really my cup of tea. The issues discussed in Les Mis were very real, if romanticised somewhat, and still bear some relevance to the modern day. I discussed one such issue in a previous It’s Lit post.

Maybe I’ll read it one day. Meanwhile, quick overviews will have to suffice.

Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables is one of history’s most famous novels and one of the longest-running musicals in Broadway history. On this special episode of It’s Lit! we explore how Les Miserable became both a national and revolutionary anthem, and so publicly adored that all 1,900 pages never went out of print.

April 21, 2019

Book Review: Socialism A Very Short Introduction by Michael Newman

Socialism: A Very Short Introduction by Michael Newman

Socialism: A Very Short Introduction by Michael Newman

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

How will we have anyone to look down upon if we all work together to make a better and fairer society?

The “A Very Short Introduction” series explores the topic of Socialism promising exactly what the title suggests. Michael Newman seeks to give an overview of socialism; the good, the bad, the misunderstood, and the misrepresented.

In my continued effort to dig into a few of the current bogeymen of cultural discourse, I went looking for an introductory text on socialism that wouldn’t shy away from the flaws but would also be more honest than most detractors. I think Newman succeeds in this respect. Many discussions of socialism treat it as a monolith – which they ironically still manage to misrepresent – which Newman is able to dispell by discussing some of the many iterations. Socialism also tends to have many ills landed at its door without adequate context – e.g. Stalin’s totalitarianism and Lysenkoism are all treated as completely socialism’s fault whilst under other policial regimes we divorce or distance those issues (people starving under capitalism isn’t capitalisms fault… apparently). Newman discusses examples like Cuba and Sweden with enough context to show how internal and external forces impacted what we regard as socialism.

This was a handy overview of socialism and certainly one that people should be encouraged to read before espousing views on the subject.

April 18, 2019

Book Review: Incorruptible by Mark Waid

Incorruptible Digital Omnibus by Mark Waid

Incorruptible Digital Omnibus by Mark Waid

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Lifetime villains just don’t know the recipe for being good.

Max Damage was at ground zero the day the Plutonian went berserk. But Max knew it was coming, he’s known the Plutonian’s secret since the day he was sent down the path of criminality. Now with his own superpowers, he realises that if the world’s greatest hero has switched sides, he has to become a hero. It was never going to be that simple though.

Incorruptible is the companion series to Mark Waid’s fantastic Irredeemable. When I originally read both series in 2011-12, I thought they were both very comparable, but that I enjoyed Max’s story more. Now upon re-reading, I’ve switched sides.

The story for Incorruptible deals with more of the consequences to the world after Superman/Plutonian turns villain. The redemption of such a despicable and immoral character is much more interesting than good guy turns bad. But where Irredeemable looks at the repercussions on multiple characters, Incorruptible mostly focuses on Max. This would be fine if Max was actually the protagonist. Unfortunately, Max is merely along for the ride, with major plot points and decisions taken away from him by the events in Irredeemable.

So if you are going to read Incorruptible, do so at the same time as Irredeemable.