Felix Abt's Blog, page 5

May 25, 2017

COMMUNIST NEWSPAPER “IL MANIFESTO” SCOLDS NORTH KOREAfor...

COMMUNIST NEWSPAPER “IL MANIFESTO” SCOLDS NORTH KOREA

for embracing capitalism “in 2004 when Felix Abt founded the Pyongyang Business School for senior business executives and government officials” (”sin dal 2004, quando lo svizzero Felix Abt ha fondato la Pyongyang Business School”).

Is Felix Abt the culprit or North Korea’s government or both?

More on the Pyongyang Business School here.

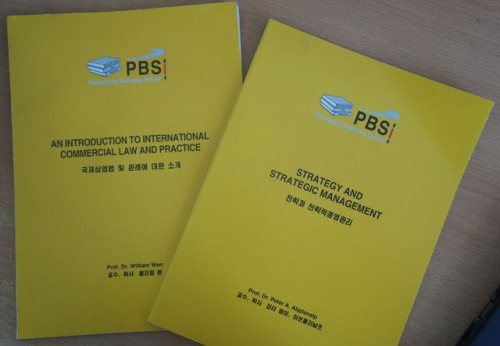

Picture shows booklets in English/Korean that were used at the Pyongyang Business School.

April 19, 2017

THE BANNED NORTH KOREA INTERVIEW

This interview was taken by...

THE BANNED NORTH KOREA INTERVIEW

This interview was taken by The Penn Political Review, a publication by the University of Pennsylvania, the Alma Mater of Donald Trump and Ivanka Trump, in

October 2016.

It was not published! The publishers say it is a magazine

which includes “a wide spectrum of student, faculty, and guest opinions from

the University of Pennsylvania and beyond.” And they also explain it is “created and motivated by

freedom of speech”.

Perhaps they are not motivated by it, but Felix Abt is and that’s why the interview is now published here!

A SOBER LOOK AT BUSINESS AND INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS

IN NORTH KOREA

Penn Political Review (PPR): What are some of the most

profitable investments in North Korea?

Felix Abt: Since many consumers have risen from a

destitute level of income over the last 15 years to a level that covers basic

needs or that reaches a middle-income, or even became part of the emerging

entrepreneurial middle class, consumer-oriented businesses, from fast-moving

consumer goods to telecommunication, have seen a significant boost in sales and

profits. The mobile phone subscription by more than 3 million inhabitants of

this country of 25 million within a few years illustrates this development.

This has been rather breath-taking by North Korean standards.

As a result, the processing of products such as

cloth or leather to meet consumers’ rising demand for affordable yet more

trendy clothes, shoes and bags has made sense for small and medium-sized

Chinese and other investors. Other items currently made in North Korea by

foreign investors, which can be partly sold domestically as well as exported to

China and other Asian countries, range from artificial flowers to false teeth.

Since the manufacturing of such products is rather low tech and requires only a

6- to 7-digit USD investment, they have attracted dozens of smaller Chinese

manufacturers.

PPR: Can western companies expect these markets to

be opened soon?

Abt: North Korea has been open for foreign

investors and traders for about two decades. When I compared the Foreign Direct

Investment (FDI) laws and regulations of China and Vietnam with North Korea’s

more than a decade ago, I couldn’t notice, at least not on paper, any

significant differences. But let’s look at the bigger picture:

1. We have to keep in mind that emerging or frontier markets are

high-risk markets with a very high rate of

business failures that will decline only over many

years as all stake holders learn from a lengthy trial and error period. Prudent

investors in these markets clearly prefer to invest in smaller projects or

disburse larger amounts of capital over a long

period of time to minimize risks and even try

to keep control over key components of their North Korean manufacturing venture.

Let me illustrate this protracted process with a

concrete example: In the nineties the German chancellor and the Vietnamese

prime minister set up a German-Vietnamese dialogue forum where complaints and

issues between German (and other foreign) investors and their Vietnamese

counterparts were addressed. I was an active participant as I was then

representing a large pool of German companies in Vietnam. Over many years the

thick book full of issues became thinner. Both sides went through an important

and unavoidable learning process leading to a smoother investment and business

environment which helped Vietnam’s economy achieve extraordinarily high growth

rates.

2.

Though the long-term market potential of an emerging market may be high,

business volumes at the beginning are usually small, and so are profits.

Investors in such markets think long-term and invest in a strong market position

(that is high market shares) to harvest over-proportionally when the emerging

market gets more mature and larger. (Followers who try to avoid the risks the

‘early birds’ take enter the market at this ‘late’ stage but will then have to

pay a high market entry price as they’ll face an uphill struggle against the

established competitors)

And

3. Let’s

not forget that entrepreneurs always take risks and that most entrepreneurial

start-ups fail, and not

only in emerging markets.

PPR: How is the legal system changing to attract

foreign investment?

Abt: The legal system is following the changes in

society, and they have been quite dramatic under the surface, hardly noticed by

the outside world. Let me illustrate that: When I settled in Pyongyang advertising

was still illegal. That was truly upsetting for a foreign businessman. But I

discussed the necessity to do advertising to allow my enterprise to survive

with the authorities for quite a long time until I was allowed to start doing

advertising. And you can imagine how pleased I was when a student of the Pyongyang Business

School which I co-founded and run, officially set up North Korea’s first advertising

company.

To give you another example: Staff was at first

always allocated by the state. Thus I had not been allowed to choose from

different candidates when I hired employees. I wanted to change that too: I

once saw a very enthusiastic North Korean lady successfully selling stuff at an

exhibition. I was impressed and decided to hire her. After lengthy negotiations

we reached a deal with her employer who allowed her to quit and join us. With

such “deals” we managed to get the best suited staff from various organizations

thereafter.

PPR: In your opinion, has Western media

misrepresented the development in the country?

Abt: Western media reports contain lots of

opinions, mostly biased, and speculations, often unfounded, but few facts and

seldom an objective analysis. So as an investor in such a frontier market you

learn much more by talking to five different Chinese entrepreneurs on their

experiences in North Korea than reading all North Korea articles published by

the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post and the Economist combined.

One example: North Korea is portrayed as the world’s

most corrupt country by the mainstream media. When I was a regional director of

a pharmaceutical multinational corporation in Africa we were often confronted

with health officials and gatekeepers who tried to use coercive ways to press

personal gains out of my company. So when, for example, we wanted to launch an

effective anti-malarial (after other anti-malarials had become ineffective due

to overuse causing high resistance), a health minister of an African country

could come up and say that he would only allow the registration, that is admission,

of this new pharmaceutical if we sponsored his son’s university studies in the

United States.

However, when I ran a pharmaceutical enterprise in

North Korea I was never confronted with demands to bribe anybody to get the

pharmaceuticals registered and onto the pharmacy shelves. I was involved in

other businesses in North Korea and there too I was never confronted with the nefarious

demands that I had found quite frequent in the other developing countries where

I had done business. Of course, there is corruption but at least foreign

investors are clearly less confronted with it in North Korea than in so many other

developing countries. That’s based on my private comparisons with investors in

other developing countries.

PPR: How profitable were your own ventures?

Abt: There was a good measure of business failures

for a number of reasons – and I couldn’t blame all of them on North Korea. But

overall my ventures have been profitable, albeit profits were quite moderate.

And the profit and other taxes we paid to the government would not have been large

enough to help fund the political system for a minute, let alone help finance

the country’s nuclear program…

PPR: Moving forward, what factors will determine

the development of business in the country?

Abt: At present, there is not much that drives

business forward; on the contrary, most if not all industries require at least

some products (such as so-called dual use items) for their manufacturing

processes, which are banned by sanctions. If these sanctions are enforced,

manufacturers will have a stark choice to make: manufacture either faulty

products or shut down production. Also, the country’s exports (coal, metals and

minerals) have been banned by sanctions with only a few exceptions. If they’re

enforced, the country’s hard currency income will vanish quickly and imports

cannot be paid for any longer. Numerous other products, from American lipsticks

to French cheese, to Italian salami to Swiss ski lifts and watches, considered as luxury,

are prohibited as well. Moreover, North Korea’s banking system is cut off from

the international banking system. This has become so absurd that foreign

investors have to bring money in a suitcase and have to collect their dividends

in bags in Pyongyang. And if the U.S. succeeds in persuading China to prohibit

North Korea’s state carrier to fly to China, foreign business people with

little time to waste will be forced to undertake long train journeys to and from

North Korea.

Obviously, current U.S. and South Korean government

policies are aimed at bringing the DPRK down. It means that any business

considered legitimate in other countries, are now increasingly “illegitimate”

in North Korea, as such policies tend to ostracize and criminalize all business

activities with this so-called Pariah state. And in a jungle of sanction laws

and regulations that differ from country to country, foreign business people

sourcing across the globe without always knowing the exact origin of an item

can easily be held responsible for any of the numerous sanctioned products in

any country and incur a huge reputational damage, regardless of the fact that

they’re used for civilian purposes. So doing business with North Korea makes

you prone to becoming a serious casualty in an economic war.

For these reasons I have started divesting my

financial participation in North Korean joint venture companies. Other

investors are likely to do the same and potentially new ones will shy away from

the country. Not only foreign investors, but North Korea’s middle class is also

likely to be strongly hurt and massive poverty in the hinterland may re-emerge.

Also, we should not forget that rising middle classes in formerly authoritarian

Asian countries, from Indonesia to the Philippines to Taiwan, forced their

regimes to change. It’s an illusion that sending balloons with propaganda

material to North Korea could transform it and that the domestic and foreign

entrepreneurs couldn’t. All hostile activities are doing is making the regime

feel more insecure and having it allocate more of the very scarce resources to

its self-preservation, while reforms are shelved and repression increases.

PPR: How does one get a job like yours?

Abt: The ABB Group, a global leader in power and automation

technologies, asked me to become their resident country

director in North Korea and build up their business there. I had worked

for ABB before, so they knew me. But I don’t know the exact reason why they

chose me. When they did I was reporting to a Swedish member of the Executive

Committee who had successfully set up one of the very first foreign-invested

factories in China when it opened up. That had then definitely not been a task

for the faint-hearted, but for a pioneer and change agent that he was. He

expected me to follow in his footsteps in North Korea.

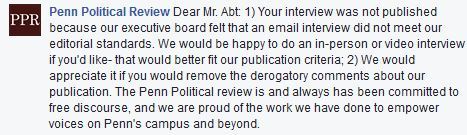

UPDATE:

Comments in reaction to this post from the Facebook page of A Capitalist in North Korea:

☆

☆

☆

☆

☆

Picture:

Felix Abt together with Dr. Jon Sung Hun

, CEO of North Korea’s Pugang Group. Pugang has been called “the North Korean equivalent of South Korea’s Samsung Group”. This North Korean business leader was repeatedly featured by the Financial Times, the Washington Post and others.

He is a great marketer of - in his own words - “cool motorbikes” and of natural products with allegedly extraordinary

health benefits, something which is very much loved by journalists in

desperate need of writing sensationalist North Korea pieces (and to attribute his personal marketing claims to the country’s leader).

This former Kim Il Sung university professor has a gregarious and

humorous personality. He wasn’t offended when Felix Abt dared to make fun of his

“miraculous” drugs. To journalists it must be

surprising (and perhaps disappointing) that Abt wasn’t sent to a Gulag or

at least instantly expelled as a consequence of challenging Dr. Jon’s claims.

☆

☆

☆

☆

☆

#NorthKorea #miraculous #drugs #pharmaceuticals #Viagra #hot #motorbikes #Pugang #interview #PennPoliticalReview @universityofpennsylvania

ON BUSINESS AND INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS

IN NORTH...

ON BUSINESS AND INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS

IN NORTH KOREA

Penn Political Review: What are some of the most

profitable investments in North Korea?

Felix Abt: Since many consumers have risen from a

destitute level of income over the last 15 years to a level that covers basic

needs or that reaches a middle-income, or even became part of the emerging

entrepreneurial middle class, consumer-oriented businesses, from fast-moving

consumer goods to telecommunication, have seen a significant boost in sales and

profits. The mobile phone subscription by more than 3 million inhabitants of

this country of 25 million within a few years illustrates this development.

This has been rather breath-taking by North Korean standards.

As a result, the processing of products such as

cloth or leather to meet consumers’ rising demand for affordable yet more

trendy clothes, shoes and bags has made sense for small and medium-sized

Chinese and other investors. Other items currently made in North Korea by

foreign investors, which can be partly sold domestically as well as exported to

China and other Asian countries, range from artificial flowers to false teeth.

Since the manufacturing of such products is rather low tech and requires only a

6- to 7-digit USD investment, they have attracted dozens of smaller Chinese

manufacturers.

PPR: Can western companies expect these markets to

be opened soon?

Abt: North Korea has been open for foreign

investors and traders for about two decades. When I compared the Foreign Direct

Investment (FDI) laws and regulations of China and Vietnam with North Korea’s

more than a decade ago, I couldn’t notice, at least not on paper, any

significant differences. But let’s look at the bigger picture:

1. We have to keep in mind that emerging or frontier markets are

high-risk markets with a very high rate of

business failures that will decline only over many

years as all stake holders learn from a lengthy trial and error period. Prudent

investors in these markets clearly prefer to invest in smaller projects or

disburse larger amounts of capital over a long

period of time to minimize risks and even try

to keep control over key components of their North Korean manufacturing venture.

Let me illustrate this protracted process with a

concrete example: In the nineties the German chancellor and the Vietnamese

prime minister set up a German-Vietnamese dialogue forum where complaints and

issues between German (and other foreign) investors and their Vietnamese

counterparts were addressed. I was an active participant as I was then

representing a large pool of German companies in Vietnam. Over many years the

thick book full of issues became thinner. Both sides went through an important

and unavoidable learning process leading to a smoother investment and business

environment which helped Vietnam’s economy achieve extraordinarily high growth

rates.

2.

Though the long-term market potential of an emerging market may be high,

business volumes at the beginning are usually small, and so are profits.

Investors in such markets think long-term and invest in a strong market position

(that is high market shares) to harvest over-proportionally when the emerging

market gets more mature and larger. (Followers who try to avoid the risks the

‘early birds’ take enter the market at this ‘late’ stage but will then have to

pay a high market entry price as they’ll face an uphill struggle against the

established competitors)

And

3. Let’s

not forget that entrepreneurs always take risks and that most entrepreneurial

start-ups fail, and not

only in emerging markets.

PPR: How is the legal system changing to attract

foreign investment?

Abt: The legal system is following the changes in

society, and they have been quite dramatic under the surface, hardly noticed by

the outside world. Let me illustrate that: When I settled in Pyongyang advertising

was still illegal. That was truly upsetting for a foreign businessman. But I

discussed the necessity to do advertising to allow my enterprise to survive

with the authorities for quite a long time until I was allowed to start doing

advertising. And you can imagine how pleased I was when a student of the Pyongyang Business

School which I co-founded and run, officially set up North Korea’s first advertising

company.

To give you another example: Staff was at first

always allocated by the state. Thus I had not been allowed to choose from

different candidates when I hired employees. I wanted to change that too: I

once saw a very enthusiastic North Korean lady successfully selling stuff at an

exhibition. I was impressed and decided to hire her. After lengthy negotiations

we reached a deal with her employer who allowed her to quit and join us. With

such “deals” we managed to get the best suited staff from various organizations

thereafter.

PPR: In your opinion, has Western media

misrepresented the development in the country?

Abt: Western media reports contain lots of

opinions, mostly biased, and speculations, often unfounded, but few facts and

seldom an objective analysis. So as an investor in such a frontier market you

learn much more by talking to five different Chinese entrepreneurs on their

experiences in North Korea than reading all North Korea articles published by

the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post and the Economist combined.

One example: North Korea is portrayed as the world’s

most corrupt country by the mainstream media. When I was a regional director of

a pharmaceutical multinational corporation in Africa we were often confronted

with health officials and gatekeepers who tried to use coercive ways to press

personal gains out of my company. So when, for example, we wanted to launch an

effective anti-malarial (after other anti-malarials had become ineffective due

to overuse causing high resistance), a health minister of an African country

could come up and say that he would only allow the registration, that is admission,

of this new pharmaceutical if we sponsored his son’s university studies in the

United States.

However, when I ran a pharmaceutical enterprise in

North Korea I was never confronted with demands to bribe anybody to get the

pharmaceuticals registered and onto the pharmacy shelves. I was involved in

other businesses in North Korea and there too I was never confronted with the nefarious

demands that I had found quite frequent in the other developing countries where

I had done business. Of course, there is corruption but at least foreign

investors are clearly less confronted with it in North Korea than in so many other

developing countries. That’s based on my private comparisons with investors in

other developing countries.

PPR: How profitable were your own ventures?

Abt: There was a good measure of business failures

for a number of reasons – and I couldn’t blame all of them on North Korea. But

overall my ventures have been profitable, albeit profits were quite moderate.

And the profit and other taxes we paid to the government would not have been large

enough to help fund the political system for a minute, let alone help finance

the country’s nuclear program…

PPR: Moving forward, what factors will determine

the development of business in the country?

Abt: At present, there is not much that drives

business forward; on the contrary, most if not all industries require at least

some products (such as so-called dual use items) for their manufacturing

processes, which are banned by sanctions. If these sanctions are enforced,

manufacturers will have a stark choice to make: manufacture either faulty

products or shut down production. Also, the country’s exports (coal, metals and

minerals) have been banned by sanctions with only a few exceptions. If they’re

enforced, the country’s hard currency income will vanish quickly and imports

cannot be paid for any longer. Numerous other products, from American lipsticks

to French cheese, to Italian salami to Swiss ski lifts and watches, considered as luxury,

are prohibited as well. Moreover, North Korea’s banking system is cut off from

the international banking system. This has become so absurd that foreign

investors have to bring money in a suitcase and have to collect their dividends

in bags in Pyongyang. And if the U.S. succeeds in persuading China to prohibit

North Korea’s state carrier to fly to China, foreign business people with

little time to waste will be forced to undertake long train journeys to and from

North Korea.

Obviously, current U.S. and South Korean government

policies are aimed at bringing the DPRK down. It means that any business

considered legitimate in other countries, are now increasingly “illegitimate”

in North Korea, as such policies tend to ostracize and criminalize all business

activities with this so-called Pariah state. And in a jungle of sanction laws

and regulations that differ from country to country, foreign business people

sourcing across the globe without always knowing the exact origin of an item

can easily be held responsible for any of the numerous sanctioned products in

any country and incur a huge reputational damage, regardless of the fact that

they’re used for civilian purposes. So doing business with North Korea makes

you prone to becoming a serious casualty in an economic war.

For these reasons I have started divesting my

financial participation in North Korean joint venture companies. Other

investors are likely to do the same and potentially new ones will shy away from

the country. Not only foreign investors, but North Korea’s middle class is also

likely to be strongly hurt and massive poverty in the hinterland may re-emerge.

Also, we should not forget that rising middle classes in formerly authoritarian

Asian countries, from Indonesia to the Philippines to Taiwan, forced their

regimes to change. It’s an illusion that sending balloons with propaganda

material to North Korea could transform it and that the domestic and foreign

entrepreneurs couldn’t. All hostile activities are doing is making the regime

feel more insecure and having it allocate more of the very scarce resources to

its self-preservation, while reforms are shelved and repression increases.

PPR: How does one get a job like yours?

Abt: The ABB Group, a global leader in power and automation

technologies, asked me to become their resident country

director in North Korea and build up their business there. I had worked

for ABB before, so they knew me. But I don’t know the exact reason why they

chose me. When they did I was reporting to a Swedish member of the Executive

Committee who had successfully set up one of the very first foreign-invested

factories in China when it opened up. That had then definitely not been a task

for the faint-hearted, but for a pioneer and change agent that he was. He

expected me to follow in his footsteps in North Korea.

*****

This interview was taken by

Mr. Jesus

Alcocer of The Penn Political Review in

October 2016 and has not been published. It says it is a publication

which includes “a wide spectrum of student, faculty, and guest opinions from

the University of Pennsylvania and beyond.” And it also explains it is “created and motivated by

freedom of speech”. Now I’m not so sure how valid this claim is…

*****

Picture:

Felix Abt together with Dr. Jon, CEO of North Korea’s Pugang Group. This North Korean business leader was repeatedly featured by the Financial Times and the Washington Post.

He is a great marketer of - in his own words - “cool motorbikes” and of natural products with allegedly extraordinary

health benefits, something which is very much loved by journalists in

desperate need of writing sensationalist North Korea pieces (and even attribute his personal marketing claims to the country’s leader).

This former Kim Il Sung university professor has a gregarious and

humorous personality. He wasn’t offended when Felix Abt dared to make fun of his

“miraculous” drugs. To journalists it must be

surprising (and perhaps disappointing) that Abt wasn’t sent to a Gulag or

at least instantly expelled as a consequence of challenging Dr. Jon’s claims.

*****

#NorthKorea #miraculous #drugs #pharmaceuticals #Viagra #hot #motorbikes #Pugang #interview #PennPoliticalReview @universityofpennsylvania

July 18, 2016

WHEN CAPITALISM CAME TO NORTH KOREAHow a Chinese businessman...

WHEN CAPITALISM CAME TO NORTH KOREA

How a Chinese businessman helped spark North Korea’s

pharmaceutical industry.

By Felix Abt

As one of the first business people to representmultinational groups and smaller organizations in North Korea, I was involved

in the negotiation of well over a dozen joint ventures, most of which didn’t

materialize: the production of transformers and electric cables to give a boost

to North Korea’s dilapidated power grid; milk powder and dairy production to

enable malnourished kids to have a daily glass of milk – sponsored by foreign

donors; and even e-commerce to help North Korean painters sell their

beautiful paintings across the globe.

Of course, setting up businesses in emerging and frontier

markets isn’t for the faint-hearted. And capital is a shy animal which doesn’t

want to be invested in a highly unpredictable and risky environment full of

legal and other uncertainties. I warned the few daring investors that

spectacularly large projects often lead to spectacular failures and recommended that they instead set up smaller

projects with capital disbursement over a longer period and encouraged them to

maintain control of imported key components for their manufacturing ventures as

a way of minimizing the inherently high risks.

This cautionary approach was based on my past experience

with other demanding emerging markets. But North Korea, with an opacity even

greater than China and Vietnam when they had first opened up, was the toughest

place of all. It had very much to do with significant philosophical differences

from the other socialist countries, which had started reforms decades earlier.

Of all the socialist countries North Korea came closest to Karl Marx’s

communist ideal: it became the most demonetized country in our lifetime,

providing all housing, education, food, healthcare, transportation, and so on

completely free of charge.

Apart from Cuba, North Korea was also the country that

received the most aid from other socialist countries. When North Korea’s

socialist trading partners and benefactors, in particular the Soviet Union,

collapsed in the nineties, its entirely state-planned economy and public

distribution system largely collapsed too. It triggered a famine resulting in

many North Koreans starting small-scale private trading activities to survive

and to make a living and other, mostly Western donors stepping in to provide

food and medicine for free.

A few years later, when I settled down in Pyongyang, it felt

like a cultural shock for the North Koreans. They had grown accustomed to

foreigners coming to their country simply to donate goods for free, but had

never before seen foreigners set up and run businesses for profit.

As the CEO of North Korea’s first pharmaceutical joint

venture, I was initially not allowed to set up a sales department and to do

advertising for our products and services, a practice that was then considered

anti-socialist. “In our country, companies don’t have sales departments and

advertising is against the law” was one of the explanations given to me. I

replied that the foreign investors would not be prepared to continue to pump

money into a loss-making enterprise and that if business practices could not be

changed in a way as to make it sustainable thanks to decent profits, it would

be shut down.

To prevent this from happening, changing minds and behavior

patterns became an almost Herculean challenge. To get advice and support I

reached out to a pioneer in China’s pharmaceutical industry, who went through a

similar experience in China just after its Cultural Revolution.

During the Cultural Revolution, he was radically demoted to

the factory’s most toxic production area. After that hazardous and depressing

period was over, Henry Jin was reinstated as head of Shanghai Pharmaceuticals,

one of China’s largest medicine producers. His re-emergence coincided with the

dawn of China’s transformation from a state planned economy to a more

market-driven one. This induced the first foreign investors to arrive, and soon

multinational pharmaceutical giant Bristol Myers Squibb was knocking on

Shanghai Pharmaceuticals’ doors. Recognizing his outstanding competence, the

government appointed Henry to set up the first pharmaceutical joint venture in

Shanghai with this American company.

As Henry explained to me, what started off as promising soon

became wrought with challenges. For one thing, the American majority investors

did not simply want land use rights for the new factory, but also demanded a

substantial cash infusion from the Chinese partners. At the end of a meeting

with senior officials chaired by Shanghai’s mayor Jiang Zemin (who later became

China’s president), the mayor asked if anyone had questions or remarks. Henry

raised his hand: “I’m tasked with setting up the first pharmaceutical joint

venture. Some cash is required but all the banks I’ve contacted have refused to

give us a loan as we don’t have any collateral.” Jiang boldly exclaimed: “I am

your collateral!” And Henry got the necessary bank credits, overcoming the

first of countless other hurdles during “a long march” to doing business in a

modern and efficient way.

In North Korea, I felt quite lonely on the board and frequently

found myself “provoking” and even angering my North Korean colleagues with

ideas which, due to our completely different life experiences, seemed very

strange to them.

Things became much easier for me when Henry accepted my

invitation to serve as a director. He did not want any fee for his invaluable

advice, but simply wanted to help this pharmaceutical enterprise succeed.

Making safer, effective, and more affordable medicine for the North Korean

people was his motivation. He was a contented octogenarian gentleman with a

generous heart who had dedicated himself to charity since his retirement some

years earlier. He became my best ally on the board and a dear friend. He

whole-heartedly supported my business plans and patiently explained to the

North Korean colleagues why things had to be done in the way I suggested.

While our North Korean friends preferred to talk about

adding new production capacities – even as existing ones remained largely

underutilized – Henry and I were advocating the need for setting up an

effective marketing and sales organization, without which the company

could not survive. Henry and I spared no efforts to convince our local partners

of the unavoidable need to adopt new business practices.

To this effect we held board meetings in China and made sure

our directors could meet and talk to Chinese colleagues while there. They were

surprised to learn from directors of state companies that Chinese authorities

were no longer interfering with day-to day-business and were actually firing

and replacing directors who failed to achieve targets, which included profits.

North Korean factories, on the other hand, were then still micromanaged by a

host of government agencies in the same style that Chinese enterprises had been

run decades earlier.

As I was not only interested in developing the factory but

also a wholesale, distribution and retail business, Henry tapped into his huge

network and opened doors for our North Korean board members and company managers

to gain access to Chinese wholesale companies, distributors and pharmacy chains

where they were even allowed to take pictures — something the hosts would never

have allowed their fellow Chinese to do.

As an early bird, circumstances were totally against me.

With the help of highly knowledgeable, empathetic Henry, who enjoyed enormous

respect among all the North Koreans he met, the early heavy losses of the enterprise slowly turned into profits. Though he was

short in terms of body height he was a giant as a humanist and he was convinced

that strong human capital, or better still, a skillful staff, thanks to intense

capacity building (training and exposure to international business practices),

was more important for the good of all stakeholders than the company’s fixed

assets. I was happy that Henry saw the fruits of his efforts: ours became an

award-winning North Korean team and the first to be recognized by the World

Health Organization (WHO) for our Good

Manufacturing Practices (GMP). Thanks to this we also became the first

North Korean enterprise to win

contracts against Asian and European rivals in competitive bidding.

It was plain to see for the North Koreans that our business

approach worked well for all stakeholders and this inspired them.

Pharmaceutical companies started knocking on our doors asking us to share our

management and production expertise with them. Henry’s charisma and leadership,

and experiences during China’s own economic transition, not only inspired our

team but paved the way for North Korea’s emergence in the pharmaceutical

industry.

Henry Jin (2nd left,

standing) together with North Korean company executives, Chinese peers, and

Felix Abt in Shanghai.Our flyers, when advertising was not

considered anti-socialist any longer. (Image courtesy of Felix Abt)A product of ours for heart conditions

and one to treat worms in adults and kids. These medicines were sold to the

WHO, which distributed them to needy hospitals in North Korea’s hinterland at a

fraction of the price it would have cost to produce in Western countries.

(Image courtesy of Felix Abt)

***

This piece was published by The Diplomat magazine in June 2016.

WHEN ‘SUNSHINE’ RULED ON THE KOREAN PENINSULARemembering a...

WHEN ‘SUNSHINE’ RULED ON THE KOREAN PENINSULA

Remembering a period of unprecedented cooperation

between the two Koreas, despite being technically still at war.

By Felix

Abt

This piece was published by The Diplomat magazine in July 2016

Before South Korea’s conservative presidents severed

ties with North Korea from 2008, their liberal predecessors Kim Dae-jung and

Roh Moo-hyun promoted peaceful engagement and rapprochement, an approach called

the “sunshine policy.” The name stemmed from an ancient Greek fable where the

wind and the sun competed to remove a man’s cloak. No matter how strongly the

wind blew, the man only wrapped his cloak more tightly to keep warm. But when

the sun shone, the warmth made him take his cloak off. The wind symbolized

unsuccessful coercive policies toward North Korea and the sun stood for an

approach able to persuade North Korea to take off its anachronistic and

uncomfortable cloak, changing at last. It wasn’t a “leftist” policy, as it was

labeled by critics from the right, since South Korea’s strongman President Park

Chung-hee had tried a similar policy in the 1970s.

The critics called Kim and Roh’s North Korea

engagement “checkbook diplomacy,” an expensive flop, and considered both

presidents as either naïve, striving for fame, or having a sinister agenda to

strengthen North Korea’s regime. An influential American journalist gave his

book the title Korea Betrayed: Kim Dae-jung and Sunshine. And

“sunshine” even became a term of mockery. In addition, the opponents of

engagement cited North Korea’s first nuclear test in 2006 as an irrefutable

proof of the complete failure of the sunshine policy. To North Korea, it meant

dissuasion and a bargaining chip in negotiating with Washington as the George

W. Bush administration “reversed the age of warm sunshine back to the age of

cold wind,” which made North Korea abandon the non-proliferation treaty, oust

International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors, and start testing long-range

missiles, Kim Dae-jung explained in a speech at Harvard University.

Kim had indeed a very ambitious plan to decrease

inter-Korean tensions and work toward a peaceful reunification. The Korean War

still lingers, as only an armistice was concluded in 1953, not a peace treaty.

Kim was aware of the fact that Pyongyang couldn’t and wouldn’t change quickly

and that he wouldn’t get much gratitude for his efforts either. A transformation

of North Korea similar to the transformations of China and Vietnam, which

brought about significant changes after the West normalized relations with

them, wasn’t just around the corner.

The tool to further Kim’s agenda was the set-up of a

wide cooperative framework that included infrastructure development, such as

the restoration and construction of roads and railways, economic assistance, as

well as a wide variety of inter-Korean business ventures. It was aimed at both

increasing living standards in the North and upping its dependence on the

South. More than 40 different types of agreements were concluded between the

two Koreas during this period. South Korean companies were not only permitted

but actively encouraged to interact with the North; in many cases they

benefited from subsidies. South Korean firms became involved in the North in

mining, agriculture, tourism, car manufacturing, and textile production. The

most outstanding achievement of Kim Dae-jung’s policy was an industrial park in

the North Korean city of Kaesong, where more than a hundred South Korean

companies employed more than 50,000 North Korean workers until South Korea’s

current President Park Geun-hye pulled the plug in 2016 and buried the last

remnants of “Sunshine.”

I lived and worked in North Korea both when the

sunshine policy peaked and when it faded away. As I was also involved in

North-South projects I experienced up close how it played out.

As resident country director of the ABB

Group, a global leader in power technologies,

I participated at a trade fair in Pyongyang where we exhibited an innovative,

environmentally-friendly large transformer for utility and industrial

applications. The transformer was made in an ABB-factory in South Korea. This

triggered lively discussions with North Koreans, who were interested in

transferring at least part of the factory in the South to the North, from which

transformers could be sold to the South, China, and elsewhere.

As CEO of North Korea’s first foreign-invested pharmaceutical

enterprise I explored ways to sell Northern

traditional herbal medicine in the South. I examined the possibility of setting

up up a small processing unit at the Kaesong Industrial Park from which to

distribute the products southward. Our North Korean company co-owners liked the

plan. Yet we were ahead of the times — though the South Korean medicine

wholesalers and retailers I talked to found the idea intriguing, they cautioned

that marketing would become a costly endeavor as Southerners would not trust

that medicine from the North would be safe.

The CEO from a large South Korean construction company

invited me to Seoul to help him draft a plan to get sand, scarce in the South

but abundant in the North.

The former CEO of South Korea’s largest dairy firm

wanted me to help him set up a dairy business in the North. Many members of

this cooperative were farmers of northern descent and enthusiastically

supported the idea. It was a commercial project with a humanitarian component:

Koreans and other donors around the world pledged to sponsor a daily glass of

milk for every North Korean child.

I was also leading the negotiations between North

Koreans and a large South Korean chaebol (business group) on a water project on

Paekdu, a “holy” mountain shared by North Korea and China and revered by the

surrounding peoples throughout history. Both the North and the South Korean

interlocutors were convinced that the magical natural water from Mount

Paekdu (to be sold as is or carbonated or as drinks blended with fruit

juice or artificial flavors) would become a huge commercial and PR-success.

Negotiations were not easy. The mistrust between the

North and South Korean business partners was an important obstacle to business

development. While the Northerners suspected Southerners of having a hidden

agenda to make a hostile takeover, the Southerners feared the Northerners were

out to rip them off. Both sides seemed to have trusted a neutral Swiss

businessman more than their fellow Koreans. Still, the chairman of one of South

Korea’s largest law firms once asked me bluntly: “On which side are you?” “On

my side!” I retorted.

To my surprise, I soon had to face one big anomaly,

namely that the input costs (rent, salaries, electricity, etc.) for South

Koreans businesses were substantially higher than for European and Chinese

businesses. I disagreed with this discrimination and raised the issue with the

authorities who replied, “The Southerners helped destroy our country, that’s

why they have to pay a higher price.”

I wanted to understand the reasoning behind this

attitude and asked a history professor at Kim Il Sung University who explained

to me:

Unfortunately, Northerners have often

been mistreated by Southerners throughout our common history. Southerners

helped foreigners exploit the North’s riches and the North’s people, forced

Northern women into prostitution in the South, forced Northern men to fight

Southern kingdoms’ wars and more recently helped Japan colonize our country and

supported the United States to destroy our cities and dams and other

infrastructure during the Korean War. They can’t get away without paying any

compensation.

That also made me understand why Kim Dae-jung transferred

hundreds of millions of dollars to North Korea, which was called corruption by

his detractors, before the historical first meeting between a North and a South

Korean leader.

During the Sunshine years, not only more and more

business people from the South came to the North. NGOs, artists, religious

groups, and tourists also crossed the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Close to two

million South Koreans visited scenic Mount Kumgang. More than 20,000 South

Koreans also met there with their Northern family members. An old North Korean

told me he was never as happy in his life as when he met his Southern family,

torn apart during the Korean War, at Mount Kumgang.

Every day, about 400 South Korean vehicles crossed the

DMZ, which Bill Clinton called the most dangerous place on earth, to North

Korea. About 1,000 people entered the North on a daily basis. In 2008 North

Korea even decided to allow South Korean visitors to use their own cars to make

the trip.

Most of the visits which now had become commonplace

were limited to mount Kumgang, Kaesong, and Pyongyang. But more and more South

Koreans were visiting other parts of the country, in particular when they were

involved in agricultural projects. Of course, they were watched and controlled,

but they also learned a lot as they could understand Korean and, more

importantly, they played the role of ambassadors representing the rich,

imitable South Korea in North Korea’s impoverished hinterland.

This was also a time when North Korean officials

started admitting that mistakes have been made in the past and interaction with

the outside world to help improve things was welcome. Sunshine allowed North

Korea to see a future beyond Kimilsungism, its state ideology.

I watched my staff and other North Koreans observe

Southern visitors. They tried to do so discreetly, but couldn’t always suppress

their amazement with an open mouth or a spontaneous smile. Southerners were

well dressed, looked well fed and healthy, and were tall by Northern standards.

They brought the latest cameras with them, were relaxed, and showed

self-confidence. Their appearance must instantly have neutralized the North’s

propaganda myths of South Koreans oppressed by the U.S. imperialists and their

South Korean puppets.

It was also interesting for me to observe when North

Korean and South Korean business people interacted outside the formal setting

of business meetings — in karaoke rooms for example. Singing together, holding

hands, and even hugging one another (and sometimes getting drunk and very

emotional together) wasn’t choreographed. The encounters transcended politics

and showed me Koreans on both sides of the fence as human beings who could get

along very well if politics did not stand in their way.

In December 2007, South Koreans were disenchanted by

what they perceived as a liberal president’s failed domestic economic policy

(not related to “Sunshine”). They elected Lee Myung-bak, a businessman

from the conservative opposition party as president, thinking he could fix

their woes. Lee had previously made an impressive career in the construction

industry and was nicknamed “bulldozer.” He had been an opponent to “Sunshine”

and when he took over the presidency in early 2008 he quickly started

bulldozing what his predecessors had built up.

Shortly after his election I went to a meeting with

North Koreans working on a North-South project. I explained that it would be a

waste to continue to work on the project given the new political circumstances.

I must have shocked them with bad news that hadn’t reached them yet. It was the

first time I looked into so many genuinely disappointed and sad North Korean

faces. With Sunshine gone, the smiles were gone too.

Pictures from left to right:

North Korean businessmen and Felix Abt outside Pyongyang after strenuous

business meetings.

“Sunshine” made it possible: South

Korean lawmakers, visiting a trade fair in Pyongyang, meet up with Felix Abt

and his North Korean staff at their booth.

One

of the last South Korean goodwill ambassadors to North Korea before the sunset

of sunshine policy: Lee Ji-sun, Miss Korea 2007, visiting Pyongyang on behalf

of the World Trade Centers Association, pictured together with Felix Abt

☆

☆

☆

☆

☆

When ‘Sunshine’ Ruled on the Korean...

When ‘Sunshine’ Ruled on the Korean Peninsula

Remembering a period of unprecedented cooperation

between the two Koreas, despite being technically still at war.

By Felix

Abt

ties with North Korea from 2008, their liberal predecessors Kim Dae-jung and

Roh Moo-hyun promoted peaceful engagement and rapprochement, an approach called

the “sunshine policy.” The name stemmed from an ancient Greek fable where the

wind and the sun competed to remove a man’s cloak. No matter how strongly the

wind blew, the man only wrapped his cloak more tightly to keep warm. But when

the sun shone, the warmth made him take his cloak off. The wind symbolized

unsuccessful coercive policies toward North Korea and the sun stood for an

approach able to persuade North Korea to take off its anachronistic and

uncomfortable cloak, changing at last. It wasn’t a “leftist” policy, as it was

labeled by critics from the right, since South Korea’s strongman President Park

Chung-hee had tried a similar policy in the 1970s.

The critics called Kim and Roh’s North Korea

engagement “checkbook diplomacy,” an expensive flop, and considered both

presidents as either naïve, striving for fame, or having a sinister agenda to

strengthen North Korea’s regime. An influential American journalist gave his

book the title Korea Betrayed: Kim Dae-jung and Sunshine. And

“sunshine” even became a term of mockery. In addition, the opponents of

engagement cited North Korea’s first nuclear test in 2006 as an irrefutable

proof of the complete failure of the sunshine policy. To North Korea, it meant

dissuasion and a bargaining chip in negotiating with Washington as the George

W. Bush administration “reversed the age of warm sunshine back to the age of

cold wind,” which made North Korea abandon the non-proliferation treaty, oust

International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors, and start testing long-range

missiles, Kim Dae-jung explained in a speech at Harvard University.

Kim had indeed a very ambitious plan to decrease

inter-Korean tensions and work toward a peaceful reunification. The Korean War

still lingers, as only an armistice was concluded in 1953, not a peace treaty.

Kim was aware of the fact that Pyongyang couldn’t and wouldn’t change quickly

and that he wouldn’t get much gratitude for his efforts either. A transformation

of North Korea similar to the transformations of China and Vietnam, which

brought about significant changes after the West normalized relations with

them, wasn’t just around the corner.

The tool to further Kim’s agenda was the set-up of a

wide cooperative framework that included infrastructure development, such as

the restoration and construction of roads and railways, economic assistance, as

well as a wide variety of inter-Korean business ventures. It was aimed at both

increasing living standards in the North and upping its dependence on the

South. More than 40 different types of agreements were concluded between the

two Koreas during this period. South Korean companies were not only permitted

but actively encouraged to interact with the North; in many cases they

benefited from subsidies. South Korean firms became involved in the North in

mining, agriculture, tourism, car manufacturing, and textile production. The

most outstanding achievement of Kim Dae-jung’s policy was an industrial park in

the North Korean city of Kaesong, where more than a hundred South Korean

companies employed more than 50,000 North Korean workers until South Korea’s

current President Park Geun-hye pulled the plug in 2016 and buried the last

remnants of “Sunshine.”

I lived and worked in North Korea both when the

sunshine policy peaked and when it faded away. As I was also involved in

North-South projects I experienced up close how it played out.

As resident country director of the ABB

Group, a global leader in power technologies,

I participated at a trade fair in Pyongyang where we exhibited an innovative,

environmentally-friendly large transformer for utility and industrial

applications. The transformer was made in an ABB-factory in South Korea. This

triggered lively discussions with North Koreans, who were interested in

transferring at least part of the factory in the South to the North, from which

transformers could be sold to the South, China, and elsewhere.

As CEO of North Korea’s first foreign-invested pharmaceutical

enterprise I explored ways to sell Northern

traditional herbal medicine in the South. I examined the possibility of setting

up up a small processing unit at the Kaesong Industrial Park from which to

distribute the products southward. Our North Korean company co-owners liked the

plan. Yet we were ahead of the times — though the South Korean medicine

wholesalers and retailers I talked to found the idea intriguing, they cautioned

that marketing would become a costly endeavor as Southerners would not trust

that medicine from the North would be safe.

The CEO from a large South Korean construction company

invited me to Seoul to help him draft a plan to get sand, scarce in the South

but abundant in the North.

The former CEO of South Korea’s largest dairy firm

wanted me to help him set up a dairy business in the North. Many members of

this cooperative were farmers of northern descent and enthusiastically

supported the idea. It was a commercial project with a humanitarian component:

Koreans and other donors around the world pledged to sponsor a daily glass of

milk for every North Korean child.

I was also leading the negotiations between North

Koreans and a large South Korean chaebol (business group) on a water project on

Paekdu, a “holy” mountain shared by North Korea and China and revered by the

surrounding peoples throughout history. Both the North and the South Korean

interlocutors were convinced that the magical natural water from Mount

Paekdu (to be sold as is or carbonated or as drinks blended with fruit

juice or artificial flavors) would become a huge commercial and PR-success.

Negotiations were not easy. The mistrust between the

North and South Korean business partners was an important obstacle to business

development. While the Northerners suspected Southerners of having a hidden

agenda to make a hostile takeover, the Southerners feared the Northerners were

out to rip them off. Both sides seemed to have trusted a neutral Swiss

businessman more than their fellow Koreans. Still, the chairman of one of South

Korea’s largest law firms once asked me bluntly: “On which side are you?” “On

my side!” I retorted.

To my surprise, I soon had to face one big anomaly,

namely that the input costs (rent, salaries, electricity, etc.) for South

Koreans businesses were substantially higher than for European and Chinese

businesses. I disagreed with this discrimination and raised the issue with the

authorities who replied, “The Southerners helped destroy our country, that’s

why they have to pay a higher price.”

I wanted to understand the reasoning behind this

attitude and asked a history professor at Kim Il Sung University who explained

to me:

Unfortunately, Northerners have often

been mistreated by Southerners throughout our common history. Southerners

helped foreigners exploit the North’s riches and the North’s people, forced

Northern women into prostitution in the South, forced Northern men to fight

Southern kingdoms’ wars and more recently helped Japan colonize our country and

supported the United States to destroy our cities and dams and other

infrastructure during the Korean War. They can’t get away without paying any

compensation.

That also made me understand why Kim Dae-jung transferred

hundreds of millions of dollars to North Korea, which was called corruption by

his detractors, before the historical first meeting between a North and a South

Korean leader.

During the Sunshine years, not only more and more

business people from the South came to the North. NGOs, artists, religious

groups, and tourists also crossed the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Close to two

million South Koreans visited scenic Mount Kumgang. More than 20,000 South

Koreans also met there with their Northern family members. An old North Korean

told me he was never as happy in his life as when he met his Southern family,

torn apart during the Korean War, at Mount Kumgang.

Every day, about 400 South Korean vehicles crossed the

DMZ, which Bill Clinton called the most dangerous place on earth, to North

Korea. About 1,000 people entered the North on a daily basis. In 2008 North

Korea even decided to allow South Korean visitors to use their own cars to make

the trip.

Most of the visits which now had become commonplace

were limited to mount Kumgang, Kaesong, and Pyongyang. But more and more South

Koreans were visiting other parts of the country, in particular when they were

involved in agricultural projects. Of course, they were watched and controlled,

but they also learned a lot as they could understand Korean and, more

importantly, they played the role of ambassadors representing the rich,

imitable South Korea in North Korea’s impoverished hinterland.

This was also a time when North Korean officials

started admitting that mistakes have been made in the past and interaction with

the outside world to help improve things was welcome. Sunshine allowed North

Korea to see a future beyond Kimilsungism, its state ideology.

I watched my staff and other North Koreans observe

Southern visitors. They tried to do so discreetly, but couldn’t always suppress

their amazement with an open mouth or a spontaneous smile. Southerners were

well dressed, looked well fed and healthy, and were tall by Northern standards.

They brought the latest cameras with them, were relaxed, and showed

self-confidence. Their appearance must instantly have neutralized the North’s

propaganda myths of South Koreans oppressed by the U.S. imperialists and their

South Korean puppets.

It was also interesting for me to observe when North

Korean and South Korean business people interacted outside the formal setting

of business meetings — in karaoke rooms for example. Singing together, holding

hands, and even hugging one another (and sometimes getting drunk and very

emotional together) wasn’t choreographed. The encounters transcended politics

and showed me Koreans on both sides of the fence as human beings who could get

along very well if politics did not stand in their way.

In December 2007, South Koreans were disenchanted by

what they perceived as a liberal president’s failed domestic economic policy

(not related to “Sunshine”). They elected Lee Myung-bak, a businessman

from the conservative opposition party as president, thinking he could fix

their woes. Lee had previously made an impressive career in the construction

industry and was nicknamed “bulldozer.” He had been an opponent to “Sunshine”

and when he took over the presidency in early 2008 he quickly started

bulldozing what his predecessors had built up.

Shortly after his election I went to a meeting with

North Koreans working on a North-South project. I explained that it would be a

waste to continue to work on the project given the new political circumstances.

I must have shocked them with bad news that hadn’t reached them yet. It was the

first time I looked into so many genuinely disappointed and sad North Korean

faces. With Sunshine gone, the smiles were gone too.

***

Pictures from left to right:

North Korean businessmen and Felix Abt outside Pyongyang after strenuous

business meetings.

“Sunshine” made it possible: South

Korean lawmakers, visiting a trade fair in Pyongyang, meet up with Felix Abt

and his North Korean staff at their booth.

One

of the last South Korean goodwill ambassadors to North Korea before the sunset

of sunshine policy: Lee Ji-sun, Miss Korea 2007, visiting Pyongyang on behalf

of the World Trade Centers Association, pictured together with Felix Abt

***

This piece was published by The Diplomat magazine in July 2016

NORTH KOREA’S ILLICIT INTERNETA brief history of the internet in...

NORTH KOREA’S ILLICIT INTERNET

A brief history of the internet in North Korea — and North

Korea’s private intranet.

By Felix Abt

North Korea has only a few thousand internet users in a

country of 25 million. To enjoy this exclusive privilege, a North Korean must

first successfully apply for a permit from the government to own a computer and

a second permit to access the internet with it. In contrast, more than 90 percent

of the people in South Korea, one of the world’s most wired countries, are

netizens.

While living in North Korea, I witnessed many changes, some

quite dramatic by North Korean standards, including the emergence of the

internet, and more significantly, its own version, namely a steadily expanding

intranet.

For internet users, North Korea’s telecom at first offered a

slow dial-up connection to a web server hosted in a Chinese province bordering

North Korea. As a resident foreigner, I didn’t need a permit and had

unrestricted access to any website. The restrictions were technological, not

political. Emails with larger

attachments were costly as their transfer often took minutes rather than

seconds, and at that time email use would cost several dollars a minute. Later

I used the internet through access set up by a German business man. An American

satellite link enabled access from North Korea’s telecom to his web server in

Germany. Thanks to his much lower prices I saved several thousand dollars a

month. To the satisfaction of its users, the evolving internet became faster

and cheaper over the years.

In parallel, North Korea developed its “Kwangmyong” which

means literally “bright” or “light.” This free, domestic-only network or

intranet opened in 2000. It offers a Firefox-style browser called “Our Country”

with which users can navigate more than 5,000 websites at present. It is a

large library, a place to propagate information, and a communication platform

between government agencies, universities, industry, and commerce. It has many

pages copied from the World Wide Web and includes flight and train schedules,

weather forecasts, and news sites. Many of North Korea’s three million mobile

phone users are using their devices to surf this intranet.

Intranet content is strictly subject to government approval;

as it says, it wants to “let the breeze from the internet in while shutting out

the mosquitoes.” Its Facebook-like pages, chat rooms, and emails are closely

monitored. It also has been difficult for the North Korean engineers of the first-foreign invested software company I co-founded to

work on projects online with clients abroad, as is common practice in the

software industry. This turned out to be an important competitive disadvantage

for us.

The intranet is also used for commercial purposes and

entertainment. When I was CEO of a pharmaceutical company, we were among the first to set up a

commercial domestic website. It helped us a lot to build our brand and

competitive services and to communicate with the medical profession

across the country while also selling and distributing our pharmaceuticals and

other healthcare products to remote provinces.

Pyongyang’s critics claim the regime is afraid of giving its

population access to the larger internet, as it would undermine its authority.

They may be right. They may also be ignoring the fact that North Koreans know

much more about the outside world than the outside world knows about them:

North Korea has less than 3.000 Western visitors a year, but many more North

Koreans flock to China every year. China issues up to 40,000 work visas for

North Koreans per year. Unsurprisingly South Korean soap operas and some

Hollywood films, which are wildly popular, find their way across the porous

Chinese border into the so-called Hermit Kingdom and North Korea’s youngsters,

reportedly, even watch porn movies.

Therefore the threat from the inflow of information may be

less real than the regime and its foes believe. But even if North Korea allowed

all its citizens unrestricted access to the internet, their access would remain

heavily censored and limited — by the United States, no less. As I’ve noted previously:

Under the conditions of international sanctions imposed

by the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control … all major

tech companies such as Google (NASDAQ:GOOG), Yahoo (NASDAQ:YHOO), Microsoft

(NASDAQ:MSFT) and Oracle (NASDAQ:ORCL) among others, also restrict access to

their products from sanctioned countries.

LinkedIn blocked my North Korea-based account in compliance

with the U.S. Treasury Department’s directive. I couldn’t use my credit card in

North Korea either but I was one of the few who could and did use Google and

Facebook as these companies seemed to have ignored U.S. sanctions law.

When I lived in Vietnam in the mid-nineties very few people had access to the Internet, then also

perceived as highly risky by the government. By mid-1998 there were an

estimated 1,500 customers, or approximately 4,000 individual internet users, in

Vietnam (population in 1998: 76 million). In this respect it was exactly the same

as when I arrived in North Korea some years later.

But, unlike in North Korea, some significant geopolitical

events would soon help change Vietnam’s landscape: On February 3, 1994,

President Bill Clinton lifted the U.S. trade embargo. On July 11, 1995,

Clinton announced the normalization of U.S.-Vietnam relations, and soon

thereafter a U.S. embassy was set up in Hanoi.

As a consequence, the fear of opening up and letting more

people have access to a hitherto “hostile” internet with its many infectious

“Western mosquitoes” diminished over the years.

As of 2015, some 20 years later, Vietnam has more than 44

million internet users (44 percent of the population), including 30 million

Facebook users.

If the United States were to end the Korean War, sign a

peace treaty and normalize its relations with the “Hermit Kingdom,” it is quite

likely North Korea could also count at least 44 percent of its population — if

not much more — as internet users in 20 years’ time.

***

Picture: Uncompromising on the

battle field, for reconciliation and reforms after the war: Vietnam’s legendary

General Giap, the mastermind behind the military defeat of the French Colonial

Power and the war against the invading U.S. military, together with his wife

and Felix Abt

***

This piece was published by The Diplomat magazine in June 2016

May 29, 2016

ON BUSINESS ETHICS, HUMAN RIGHTS, SANCTIONS AND REFORMS IN NORTH KOREA

Here is Felix Abt’s full interview with The Huffington Post

December 6, 2015

A DISTURBING NORTH KOREA EXPERIENCE - CENSORED BY THE FREE...

A DISTURBING NORTH KOREA EXPERIENCE - CENSORED BY THE FREE WESTERN PRESS

When

reporting on North Korea the Western media publish vilifying claims

with alacrity; happy to go to press without substantiation. The more

disparaging and absurd or outlandish the story the more likely,

apparently, it will make it into print: from an ongoing Holocaust with

bodies floating in North Korea’s rivers and piling up on its streets

(which bewilderingly has not been witnessed by either residents or

visiting foreigners, nor picked up by the plethora of satellites

monitoring the ‘rogue state’ and, furthermore, it is hardly credible to

equate this apocryphal carnage with a population steadily on the

increase ), to its leader shooting an amazing 11 holes-in-one, achieving

an unprecedented 38-under-par game on a regulation 18-hole golf course -

on his first try at golf. Were this story to have any basis in fact,

surely the one place it would have been widely promulgated is within the

country itself, to inspire the populace or praise the leadership, but

very few North Koreans were aware of this preposterous claim, so widely

spread in the West, and then only through Western media sources.

Hawkish

recommendations on how to ‘deal with’ North Korea similarly get plenty

of media attention. For example Joshua Stanton, an advocate of the

continuing strangulating sanctions and vociferously opposed to any kind

of engagement, has his opinions readily quoted and published by the

‘free’ press. But the supposed balance which Western media claims for

itself is conspicuously absent in its reportage of North Korea. To

attempt to prove the partisan nature of the press Felix Abt submitted the

article below to the following media and opinion leaders:

The

Guardian, The Independent, The Times (of London), The Telegraph, The

Financial Times, The Washington Post, The Huffington Post, The Diplomat,

Wired, The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, Thomson Reuters, Forbes, The

New York Times

It was rejected by every single one. We can only

conclude that they have no desire to publish views contrary to their

established editorial position on North Korea, but rather seek to

suppress such views, even when they come from a source with intimate

personal experience of the state of affairs within the country and

presenting verifiable facts. Wild, unsubstantiated claims make better

copy apparently.

With the exception of The Financial Times, ALL OF

THESE MEDIA have also ignored Abt’s book A Capitalist in North Korea: My

Seven Years in the Hermit Kingdom. Other publications on North Korea,

particularly where they tell horror stories of suppression and death,

whether true or invented, get pages of media attention and praise. The

New York Times, for example, recently published a positive review of a

book by a tourist who visited Pyongyang and its neighborhood for just

one week! Since its author called North Korea the ‘worst place on earth’

she apparently deserved the acclaim. Understandably, its writer, an

American woman, hasn’t traveled to Somalia, Yemen, Iraq, Syria or

Afghanistan as she could easily have been abducted, raped and killed

there. Nevertheless, one week in the ‘hell hole’ of North Korea, as it

is referred to by other widely quoted book authors, deserves full

attention. An honest account of seven years living there, and working

and interacting with North Korean workers, engineers, farmers, doctors

and scientists, however, is too unpalatable to receive recognition from

the blinkered Western media.

If you want to challenge the

information and opinion monopoly held by a press that claims to defend

free speech (with delicious Orwellian irony), please post the link of Felix Abt’s

article: http://38north.org/2012/12/fabt122312/ wherever you can.

March 23, 2015

AUTOMATONS, SLAVES OR MEMBERS OF THE 1% ELITEThat’s the...

AUTOMATONS, SLAVES OR MEMBERS OF THE 1% ELITE

That’s the stereotypical portrayal of North Koreans by foreign media and authors of books on the country. My personal experience of the people of

the DPRK was very different.

I recruited

staff from universities, commercial enterprises and other organizations

in North Korea and had a good mix of ages and backgrounds. Initially

around half were women, but this was increased substantially over time

as women were generally found to be more diligent and dedicated to tasks

than their male counterparts. In my experience, this seems to be true

throughout Asia. Just a small proportion belonged to the

Korean Labor Party.

Most were slim when they started with us,

but many added a little padding the longer they stayed. Older members of

staff were usually married, younger staff often in love and some even

showing symptoms of lovesickness. A few displayed signs of, or confided

to, difficult relationships and a small number were divorced. There were

rumors that some married staff members were not entirely faithful. Some

colleagues liked one another better than others and sometimes there

were misunderstandings and arguments. In other words, it was just like

any of the companies I had worked in around the world.

All of my

staff were hard workers, and if they weren’t they didn’t stay long.

Exceptionally, the harder working staff asked for better training or the

replacement of lazy or incompetent ones. Some always seemed to wear a

serious face, others were often smiling. Some were introvert, others

garrulous and fun-loving, telling jokes and enjoying a laugh. North

Koreans love to joke and tell funny stories, as I experienced in

numerous encounters with not only the employees, but also suppliers and

customers. Some of the jokes would merit a xxx-rating in other

countries!

Without exception the staff loved their children and

were bursting with pride over their achievements. If a child

successfully passed the entrance exam to a good school there was

jubilation. Conversely, a child underperforming was the cause of huge

anguish and could result in tearful scenes. I had great pleasure in

meeting children of my staff on various occasions and found them just

like kids anywhere else: some were shy and reticent, others were curious

and bursting with questions for me. That the staff’s adult children

married well was a very important topic, and so were grandchildren.

There was none so proud among the staff as a contented grandparent.

Though

media in the West claim most North Korean adults use meth and other

drugs, I saw no signs of it among the workforce. I believe I am well

aware of the signs and what to look for and knew that users of such

drugs would typically display the symptoms after a while. On the other

hand, most men were heavy smokers and loved to drink Soju and other hard

alcoholic drinks. However, the latter was generally restricted to

special occasions such as holidays or birthday parties.

As we

jointly had to achieve some really tough objectives in a very demanding

environment a close bond developed between my staff and me. They trusted

me that I wouldn’t betray them and so I learned more about their

families, friends, interests and hobbies than was usual for a westerner.

We became even closer as we organized outings, sport days and Karaoke

evenings and often played volleyball or table tennis together after

work.

My video above

shows one of my female staff members in the company canteen giving a

short performance of ‘Tul’ (also teul or 틀 in Korean), which is as

rigorous and precise as a Swiss clock, on the way to mastering North

Korea’s favorite national sport Taekwondo, the equivalent to the ‘kata’

in karate.