George Levrier-Jones's Blog

October 15, 2025

The Romans in the Central Sahara: Cornelius Balbus' Expedition

Cornelius Balbus' expedition into the heart of the central Sahara in 19 BCE reads like one of those stubborn footnotes that suddenly throws a spotlight on the limits and ambitions of Rome. Ordered during Augustus' long reign of consolidation, the campaign against the Garamantes, a long-established people centered in the Libyan Fezzān (with a capital often written as Garama or Germa), was not an attempt to annex a vast Saharan empire so much as a punitive and strategic effort: to punish raiding that menaced Roman North Africa, secure trans-Saharan trade routes, and demonstrate imperial reach beyond the familiar Mediterranean littoral.

Terry Bailey explains.

Lucius Cornelius Balbus statue in Cadiz, Spain. Source: Peejayem, available here .

Ancient literary sources record that Lucius (or sometimes rendered as Cornelius) Balbus celebrated a triumph in Rome after operations in the region, and later Roman authors, chiefly Pliny the Elder and writers summarized by Cassius Dio, place a handful of Garamantian settlements under Roman pressure or control around that time.

What actually happened on the ground and how far south Balbus' columns pushed, remains a matter for cautious reconstruction rather than neat storylines. Classical authors describe the Garamantes as a confederation that could strike along the coastal provinces and carry on a lively inland commerce; in 19 BCE the Romans, led by Balbus, are said to have captured multiple settlements and brought back evidence of victory to Rome, enough to earn a public triumph recorded on the Roman fasti.

Ancient historians framed the campaign as both corrective and economic: remove the threat of raids that harmed coastal cities such as Leptis Magna, and (if possible) open or safeguard commercial arteries feeding Roman markets. However, the surviving literary traces are short on operational detail and generous on Roman self-description, so scholarship treats the narratives as a starting point, not a literal map.

Archaeology has been invaluable in turning those literary hints into a more concrete picture of Garamantian power and how an outsider like Balbus might have engaged it. The Garamantes were far from the purely nomadic caricature of some classical writers: excavations and surveys across the Fazzān have exposed permanent settlements, cemeteries of distinctive tomb-pyramid forms, irrigation systems (the foggaras or qanat-like galleries) that tapped fossil aquifers, and networks of forts and farmed oases that made sedentary agriculture possible in the now hyper-arid landscape.

Satellite imagery and field survey in recent decades have revealed rings of forts and the outlines of defended centers in and around Germa. These Garamantian capital installations could be the objective or the spoils of a Roman punitive expedition. This material context helps explain why Romans would bother to project force into the Sahara: the Garamantes controlled water, people, and routes that mattered to commerce and coastal security.

Direct archaeological evidence pointing specifically to Balbus' 19 BCE raid is necessarily limited. Unlike a campaign that left garrison forts with Latin inscriptions, the available material tends to show interaction rather than long-term occupation: imported Roman goods and amphorae found at Garamantian sites, references in Roman placards (the Fasti Triumphales) to Balbus' triumph, and the wider circulation of objects such as carnelian beads that testify to Saharan long-distance trade.

Sources of traded materials

Scientific work tracing the sources of traded materials, for instance studies on carnelian provenance from the Fazzān supports the interpretation that the region was enmeshed in exchange networks linking sub-Saharan Africa, the Sahara, and the Mediterranean. In other words, archaeology corroborates the literary claim that Garamantian centers were prosperous and connected and therefore plausible targets for a high-profile Roman campaign even if it does not produce a single, unambiguous "Balbus layer" in the sand.

Modern archaeological narratives also complicate the older Roman story. Where some classical writers presented the Garamantes as perennial raiders, the material record shows complex, largely sedentary settlements with irrigation engineering that required organized labor and administration. Recent surveys and excavations argue for a polity that could sustain agriculture, fortifications and caravan ways.

Remote sensing, (the use of satellite imagery and aerial survey), has been especially transformative: archaeologists have mapped previously invisible lines of forts, settlement clusters and irrigation channels, revealing a landscape of infrastructure rather than scattered nomads. Those same tools have fed the debate over whether Roman operations produced any lasting control; most specialists now favor the view that Balbus' action was a decisive but short-term blow that destabilized and humiliated opponents without creating long-term Roman rule deep in the Sahara.

Putting the sources together produces a balanced verdict: Cornelius Balbus' 19 BCE expedition matters less because it produced an enduring Roman province than because it reveals how far Roman imperial ambition extended, and how Mediterranean powers interacted with African polities that were neither "primitive" nor marginal. The Romans used military theatre, political spectacle (the triumphal parade in Rome) and occasional force to regulate trade and security beyond their borders; the Garamantes, for their part, were sophisticated desert engineers and traders with the resources to attract Roman attention.

Archaeology has not so much confirmed every detail of the ancient accounts as given us a richer world in which to place them: a networked Sahara of wells and foggaras, fortified towns, and caravan routes, all of which help explain why a Roman commander like Balbus would march and why Rome would brag about it in the Forum.

Today the ruins of Germa and the Fazzān remain powerful reminders of that encounter. They are fragile in the face of climate change, looting, and modern instability, but their tombs, irrigation galleries, and the scattered Roman imports found there let us read a short, vivid chapter of cross-Saharan interaction: a Roman triumph, a desert polity's engineering achievement, and the faint, material outlines of a meeting between worlds that were geographically close yet culturally distinct.

As scholarship and remote-sensing techniques progress, archaeologists may yet recover more direct remains of the 19 BCE operations, inscriptions, datable destruction layers or battlefield debris but even now the combined weight of texts and material culture makes Balbus' expedition a plausible, illuminating episode in Rome's long dialogue with Africa.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Cornelius Balbus' expedition to the Garamantes stands as a moment where history, archaeology, and imperial ambition intersect. It was not the production of new borders or the founding of colonies that gave the campaign its importance, but the symbolic weight of Rome's ability to project power into the vast Sahara and to claim victory over a people whose influence reached across desert trade routes.

The Garamantes, far from being a shadowy footnote in Roman annals, emerge through archaeology as a complex society of farmers, engineers, and traders who were both resilient and connected to broader worlds. Balbus' march thus becomes more than a fleeting military episode: it highlights the limits of empire, the realities of cross-cultural contact, and the delicate balance between spectacle and substance in Rome's dealings beyond its frontiers.

The story, refracted through ancient texts and sharpened by modern research, continues to remind us that Rome's triumphs often tell us as much about the societies it encountered as they do about the empire itself.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here .

Notes:

Roman fasti

The fasti were chronological lists or calendars that the Romans used to record the passage of time and important public events. Originally, the term referred to the official calendar that marked days as dies fasti (days on which legal and political business could be conducted) or dies nefasti (days when such activities were forbidden, often due to religious observances).

Over time, the scope of the fasti expanded to include records of magistrates, priests, triumphs, and other significant occurrences that structured Roman political and religious life. They were inscribed on stone or bronze tablets and often displayed publicly, ensuring that both civic order and Rome's collective memory were preserved for its citizens.

One of the most famous examples is the Fasti Capitolini, discovered in the Roman Forum during the Renaissance. These inscriptions, dating to the reign of Augustus, recorded the names of Roman consuls year by year from the founding of the Republic, alongside magistrates and notable triumphs. Such records were crucial for Roman historiography, as they provided a backbone of chronology against which events could be measured. They also carried ideological weight: Augustus, for instance, used the fasti not only to establish a coherent timeline but also to underline Rome's enduring greatness and the legitimacy of his own reign as the restorer of order.

Beyond their practical function, the fasti served as instruments of political propaganda. Recording triumphs and priesthoods, they immortalized Rome's victories and the men who achieved them, reinforcing the notion that Roman history was a continuous narrative of conquest, piety, and civic order. They were as much about shaping collective memory as about documenting the past. For example, the entry noting Cornelius Balbus' triumph after his expedition to the Garamantes ensured that his deeds were remembered in the same continuum as those of Rome's greatest generals. In this way, the fasti were not merely dry lists, but enduring symbols of Roman identity, linking religious practice, political authority, and historical consciousness in a single, monumental record.

October 11, 2025

The Plan for Napoleon’s Secret Escape to America

Napoleon Bonaparte lost the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, which ultimately led to his departure from France. There was much speculation about where he would end up after leaving France – including the possibility of Napoleon going to America.

Michael Thomas Leibrandt explains.

Napoléon in Sainte-Hélène by František Xaver Sandmann.

I’ve always loved that iconic painting by Jacques-Louis David of Emperor Napoleon on his horse crossing the Alps. It’s not just the beautiful grandeur of his military attire on parade — on his way to a victory at the Battle of Marengo — and ascension from First Consul of France to become Emperor. It’s the boldness of command that he showed as his French Army surprised the Austrian forces under Michael von Melas. This summer season marks 210 years since Napoleon’s final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo.

After crossing the river at Charleroi— Napoleon came between the British and Prussian forces — engaging and defeating Marshal Blucher at Ligny. But when Napoleon was lured into Battle around the village of Waterloo — Lord Wellington’s forces were able to hold out just long enough for the Prussians to arrive. At the end of the Battle — for one of the only times in history — Napoleon’s Old Guard was defeated in combat.

But immediately after vacating the battlefield at Waterloo — Napoleon wanted to continue the war after recently escaping his first exile on the island of Elba and landing once again on French soil. But to the surprise of some — Napoleon didn’t seize power with the shattered remnants of the French Army. Instead — he would abdicate the thrown for the second time on June 22nd after returning to Paris on June 21st.

On June 25th — Napoleon departed the French capital for the last time ever. He would see his mother for the last time in Malmaison — and most ironically would arrive on July 3rd in Rochefort with visions of boarding a ship to America — just hours before the celebration of American Independence from Britain. Napoleon’s plan would be to land somewherebetween Maryland and Virginia. But the French Provisional Government never provided the correct documents and passports.

For the man who had conquered most of Europe at his height of power — America offered the Emperor a new beginning. England had been at war with the United States just three years earlier — which meant that requesting that the American government extradite Napoleon Bonaparte at the Seventh Coalition’s request could be unlikely.

In the end — Napoleon would board a ship. It just wasn’t one bound for America. Instead — Napoleon Bonaparte landed on the island of Aix. He then surrendered to the British Army — and was exiled once again to the island of St. Helena — nearly one thousand miles off the coast of Africa despite his request to retire to the countryside of England. He would arrive on St. Helena in October of 1815 courtesy of the British ship (Northumberland.) He would perish on the island six years later.

With his death — so too faded the attempt of Napoleon to get to American shores. It’s interesting to speculate what it would have meant for Napoleon — Emperor of the French and nearly unbeatable on land — could have given military guidance to the United States Army. Before surrendering to the British — he would proclaim, “I put myself under the protection of their laws; which I claim from your Royal Highness, as the most powerful, the most constant, and the most generous of my enemies.”

Michael Thomas Leibrandt lives and works in Abington Township, PA.

October 9, 2025

Howard Carter and the Discovery of King Tutankhamun’s Tomb

When asked about the Ancient Egyptians, and in particular King Tutankhamun, many will think of iconography like mummies wrapped in bandages, imposing pyramids and talk of curses. In November 1922, British archaeologist Howard Carter discovered the sealed tomb of King Tutankhamun and it became an international sensation. When his benefactor Lord Carnarvon died suddenly in April 1923, the press had no trouble in whipping up a sensationalist story of ill fortune and supernatural curses. Carter and his team were thrown into the limelight of hungry gazes tracking their every move, waiting for something to happen. Not only did Carter’s excavation site become one of interest, but also publicized Egyptology as a branch of archaeology often previously overlooked. Frequently the focus has been on the discovery itself rather than the discoverer and how Carter dedicated his life to Egypt that peaked with his career defining excavation in 1922. This article will explore the excavation of King Tutankhamun with focus on the Egyptologist, Howard Carter and his relentless search for the tomb.

Amy Chandler explains.

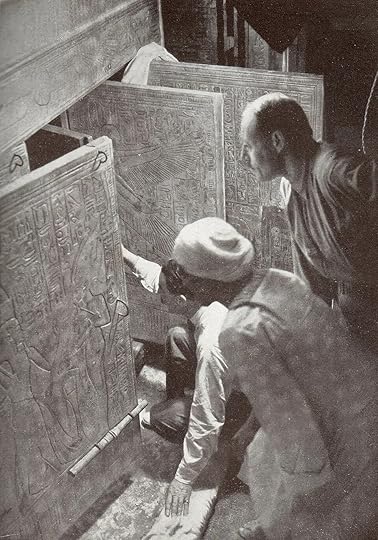

Howard Carter (seen here squatting), Arthur Callender and a workman. They are looking into the opened shrines enclosing Tutankhamun's sarcophagus.

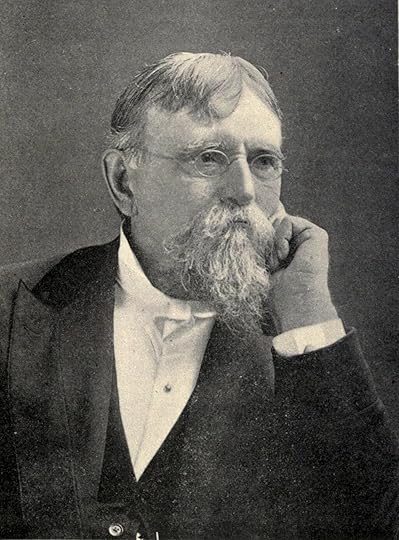

Howard Carter

Howard Carter’s story is one of a series of coincidences, hard work in the dust and rubble of excavation sites and unwavering conviction that there was more to discover. He was not content until he had seen every inch of the Valley of the Kings and only then would he resign to the fact there was nothing left to discover. Carter’s fascination with Egypt began when he was a child and his family moved from London to Norfolk due to his childhood illness. (1) A family friend, Lady Amherst owned a collection of Ancient Egyptian antiquities, which piqued Carter’s interest. In 1891, at seventeen years old, his artistic talent impressed Lady Amherst and she suggested to the Egypt Exploration Fund that Carter assist an Amherst family friend in an excavation site in Egypt despite having no formal training. He was sent as an artist to copy the decorations of the tomb at the Beni Hasan cemetery of the Middle Kingdom. (1)

During this time he was influential in improving the efficiency of copying the inscriptions and images that covered the tombs. By 1899, he was appointed Inspector of Monuments in upper Egypt at the personal recommendation of the Head of the Antiquities Services, Gaston Maspero. Throughout his work with the Antiquities Services he was praised and seen in high regard for the way he modernized excavation in the area with his use of a systematic grid system and his dedication to the preservation and accessibility to already existing sites. Notably, he oversaw excavations in Thebes and supervised exploration in the Valley of the Kings by the remorseless tomb hunter and American businessman, Theodore Davis who dominated the excavation sites in the valley. In 1902, Carter started his own search in the valley with some success but nothing that was quite like King Tutankhamun’s tomb. His career took a turn in 1903 when a volatile dispute broke out between Egyptian guards and French tourists, referred as the Saqqara Affair, where tourists broke into a cordoned off archaeological site. Carter sided with the Egyptian guards, warranting a complaint from French officials and when Carter refused to apologize he resigned from his position. This incident emphasizes Carter’s dedication, even when faced with confrontation, to the rules set out by the Antiquities Service and the preservation of excavation sites.

For three years he was unemployed and moved back to Luxor where he sold watercolor paintings to tourists. In 1907, Carter was introduced to George Herbert, the fifth earl of Carnarvon (Lord Carnarvon) and they worked together in Egypt excavating a number of minor tombs located in the necropolis of Thebes. They even published a well-received scholarly work, Five Years’ Exploration at Thebes in 1911. (2) Despite the ups and downs of Carter’s career, he was still adamant that there was more to find in the Valley of the Kings, notably the tomb of the boy king. During his employment under Carnarvon, Carter was also a dealer in Egyptian antiquities and made money from commission selling of Carnarvon’s finds to the Metropolitan Museum of New York. (2) After over a decade of searching and working in the area, Carter finally had a breakthrough in 1922.

Excavating in the Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings, located near Luxor, was a major excavation site and by the early 1900s, it was thought that there was nothing left to discover and everything to be found was already in the hands of private collectors, museums and archaeologists. Davis was certain of this fact so much so that he relinquished his excavation permit. He’d been excavating in the area between 1902 to 1914 on the West bank of Luxor until the outbreak of The Great War in 1914. By the end of the war, the political and economic landscape of Europe and the Egypt had changed significantly. In 1919, Egypt underwent a massive political shift with the Egyptian Revolution that saw the replacement of the Pro-British government that had ruled since 1882 with a radical Egyptian government that focused on a strong sense of Nationalism. This political shift also changed the way that British and foreign archaeologists could operate in the area. In particular, the government limited the exportation of artefacts found and asserted the claim on all “things to be discovered.” (3) This meant that everything found in Egyptian territory was the property of Egypt and not of the individual or party that discovered it. Previously, it was a lot easier for artefacts to be exported into the hands of private collectors and sold or worked on the partage system of equally sharing the finds between the party working on the site. All excavations had to be supervised by the Antiquities Services. These regulations only expanded what was already outlined in the 1912 Law of Antiquities No. 14 regarding ownership, expert and permits. (4) Any exceptions or special concessions had to be approved by the Antiquities Services and have the correct permit issued. In many ways, this ‘crack down’ on free use of Egyptian territory pushed back against the British colonial rule and the desire to take back what was rightfully Egyptian and taking pride in Egyptian culture and heritage.

The strict approach towards foreign excavators coupled with Davis’ public decision to relinquish his permit changed the way archaeologists like Carter could operate. Early 1922, Carter and Carnarvon worked a tireless 6 seasons of systematic searching, only to have no success. It was estimated that the workers moved around 200,000 tons of rubble in their search. (2) Carnarvon gave Carter an ultimatum, either he found something in the next season or the funds would be cut. Despite the suggestion that the valley was exhausted and there was nothing left to find, Carter was adamant there was more. A fact only proven true when he discovered several artefacts with Tutankhamun’s royal name. In November 1922, Carter re-evaluated his previous research and ordered for the removal of several huts from the site that were originally used by workers during the excavation of Rameses VI. Below these huts were the steps leading to the sealed tomb of Tutankhamun. In fear of another archaeologist discovering the tomb, Carter ordered the steps to be covered again and sent a telegram to Carnarvon on 6 November. Two weeks later on 23 November work began on excavating and uncovering the tomb. Damage to the door suggested the entrance had been breached previously and badly re-sealed by tomb robbers, but they didn’t get any further than the corridor. It took three days to clear the passage from rubble and quickly redirected electric light off the grid being used in another tomb in the valley for tourists to Carter’s site. (2) Once news broke out, Carter enlisted the help of experts, English archaeologists, American photographers, workers from other sites, linguists and even a chemist from the Egyptian Government’s department for health on advice on preservation. (2) Each object was carefully documented and photographed in a way that differed to the usual practice on excavation sites. They utilized an empty tomb nearby and turned the space into a temporary laboratory for the cataloguing and documentation process of antiquities found.

Public attention

By 30 November, the world knew of Carter and Carnarvon’s discovery. Mass interest and excitement sent many tourists and journalists to flock to the site and see for themselves this marvelous discovery. Carter found his new fame in the limelight to be a “bewildering experience”. (5) As soon as the discovery was announced, the excavation site was met with an “interest so intense and so avid for details” with journalists piling in to interview Carter and Carnarvon. (5) From Carter’s personal journal, it is evident that the fame associated with the discovery wasn’t unwelcome, but more of a shock. Historians have suggested that this surge in fascination was due to boredom with the talk of reparations in Europe following the war and the thrill of watching the excavation unfold. Problems came when individuals looked to exploit or use the excavation to gleam a new angle to further their own gain – whether that be journalists or enthusiasts hoping to boast to their friends back home.

Once news of the discovery made headlines, Carnarvon made an exclusivity deal with The Times to report first-hand details, interviews and photographs. He was paid £5000 and received 75% of all fees for syndicated reports and photographs of the excavation site. (2) This deal disgruntled rival newspapers and journalists who needed to work harder to find new information to report. One rival in particular was keen to cause trouble for Carter. British journalist and Egyptologist Arthur Wiegall was sent by the Daily Express to cover the story. He had a history with Carter that led to his resignation as Regional Inspector General for the Antiquities Service in Egypt between 1905 to 1914. Carter made the Antiquities Services aware of rumors that Wiegall had attempted to illegally sell and export Egyptian artefacts. Arguably, Weigall wanted to experience the excavation site first hand and be the first to report any missteps. He is often referred to as the ringleader for disgruntled journalists that made trouble for Carter, especially when Carnarvon died. Interestingly, Weigall worked with Carnarvon years before Carter in 1909 and helped Carnarvon discover a sarcophagus of a mummified cat – his first success as an excavator. (2) Arguably, there was a jealous undercurrent that only intensified the pressure that Carter was faced with by the press and other Egyptologists. In the weeks after the initial publication by The Times, Carter received what he called a sack full of letters of congratulations, asking for souvenirs, film offers, advice from experts and copyright on the style clothes and best methods of appeasing evil spirits. (5) The offers of money were also high that all suggest that the public were not necessarily interested in Egyptology or the culture and historical significance of the tomb, but the ability to profit and commercialize the discovery.

Furthermore, the growth in tourism to the area was a concern. Previously, tours to visit monuments and tombs in the Valley of the Kings was an efficient and business like affair with strict schedules. This all changed, by the winter all usual schedules and tour guides were disregarded and visitors were drawn like a magnet to Tutankhamun’s tomb and the other usually popular sites were forgotten. From the early hours in the morning, visitors arrived on the back of donkeys, carts and horse drawn cabs. They set up camp for the day or longer on a low wall looking over the tomb to watch the excavation with many reading and knitting waiting for something to happen. Carter and his team even played into the spectacle and were happy to share their findings with visitors. This was especially evident when removing artefacts from the tomb. At first, it was flattering for Carter to be able to share his obvious passion for Egyptology and the discovery. This openness only encouraged problems that became more challenging as time went on. Letters of Introduction began piling up from close friends, friends of friends, diplomats, ministers and departmental officials in Cairo, all wanting a special tour of the tomb and many bluntly demanded admittance in a way which made it unreasonable for Carter to refuse for fear they could damage his career. (5)

The usual rules involved in entering an excavation site were dismissed by the general public and the constant interruption to work was highly unusual. This level of disrespect for boundaries also caused a lot of disgruntlement and criticism from experts and other archaeologists who accused Carter and his team of a “lack of consideration, ill manners, selfishness and boorishness” surrounding safety and removal of artefacts. (5) The site would often receive around 10 parties of visitors, each taking up half an hour of Carter’s time. In his estimation, these short visits took up a quarter of the working season just to appease tourists. These moments of genuine enthusiasm were soon overshadowed by visitors who weren’t particularly interested in archaeology but visited out of curiosity, or as Carter stated, “a desire to visit the tomb because it is the thing to do.” (5) By December, after 10 days of opening the tomb, work on excavating the tomb was brought to a standstill and the tomb was filled with the artefacts, the entrance sealed with a custom made steel door and buried. Carter and his team disappeared from the site for a week and once they returned to the tomb, he placed strict rules including no visitors to the lab. The excavation team built scaffolding around the entrance to aid their work in the burial chamber and this further deterred visitors from standing too close to the site. Artefacts were quickly catalogued and packed after use and many were sent to the museum in Cairo and exhibited while work was still being done. Visitors were urged to visit the museum to view the artefacts on display rather than directly engaging with the tomb. As they solved the issue of crowds, disaster struck enticing journalists back to the site when Lord Carnarvon died in April 1923. Despite Carnarvon’s death, work still continued on the tomb and did not complete until 1932.

Conclusion

Carter’s discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb transformed Egyptology as a branch of archaeology into a spectacle and a commodity rather than genuine interest. Instead of a serious pursuit for knowledge the excavation became a performance and this greatly impacted work. The sensationalist story of an Ancient Egyptian curse that circulated after Carnarvon’s death has also tarnished how the world perceives Egyptology. This has only been compounded further by popular culture and ‘Tutmania’ that often replaces fact. However, Carter’s discovery has brought a sense of pride and nationalism to Egypt. In July 2025, a new museum – Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) - opened in Cairo, located near the Pyramids of Giza, to specifically preserve and display the collection of artefacts from King Tutankhamun’s tomb. (5) It was important that these objects were brought back to Egypt rather than be on loan around the world. Historians and Egyptologists work hard to present and reiterate the facts rather than fuel the stories weaved by popular culture. Without Carter’s discovery, historians wouldn’t have the depth of knowledge that they do now. Despite Carter’s success, he was never recognized for his achievements by the British government. Historians have suggested he was shunned from prominent Egyptology circles because of personal jealousy, prejudice that he received no formal training or his personality. (1) He is now hailed as one of the greatest Egyptologists of the twentieth century and his legacy lives on, even if the field has become tainted by the idea of Ancient Egyptian curses. It is a steep price to pay for knowledge. After the excavation was completed in 1932, Carter retired from field work and continued to live in Luxor in the winter and also stay in his flat in London. (1) As the fascination with the excavation simmered down, he lived a fairly isolated life working as a part-time dealer of antiquities for museums and collectors. He died in his London flat in Albert Court located near the Royal Albert Hall from Hodgkin’s disease in 1939, only nine people attended his funeral. (1) Sadly, some have commented that after dedicating decades to Egyptology Carter lost his spark of curiosity once he discovered Tutankhamun. Presumably this was due to the fact that he knew that there was nothing left to discover and his search was over.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here .

References

1) S. Ingram, ‘Unmasking Howard Carter – the man who found Tutankhamun’, 2022, National Geographic < https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/howard-carter-tomb-tutankhamun# >[accessed 11 September 2025].

2) R. Luckhurst, The Mummy’s Curse: The True History of a Dark Fantasy (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2012), pp. 3 -7, 11 – 13.

3) E. Colla, Conflicted Antiquities: Egyptology, Egyptomania, Egyptian Modernity (Duke University Press, Durham, 2007), p. 202.

4) A. Stevenson. Scattered Finds: Archaeology, Egyptology and Museums (London, UCL Press, 2019), p. 259.

5) H. Carter. And A. C. Mace, The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen (Dover, USA, 1977), pp. 141 – 150.

6) G. Haris, ‘More than 160 Tutankhamun treasures have arrived at the Grand Egyptian Museum’, 2025, The art newspaper < https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2025/05/14/over-160-tutankhamun-treasures-have-arrived-at-the-grand-egyptian-museum >[accessed 27 August 2025].

October 8, 2025

Ferdinand Magellan: The Man who First Circumnavigated the Globe

Ferdinand Magellan's name is etched into history as the man who led the first expedition to circumnavigate the globe, an achievement that forever reshaped humanity's understanding of the world. His journey was a story of daring ambition, perilous voyages, and unyielding determination, all undertaken in the age of discovery when maps were incomplete and much of the Earth remained mysterious. Yet Magellan himself would not live to see the full success of his enterprise, perishing before his fleet returned home. His legacy, however, endured as one of the most significant milestones in the history of navigation and exploration.

Terry Bailey explains.

Discovery of the Strait of Magellan (Descubrimiento del Estrecho de Magallanes) by Álvaro Casanova Zenteno.

Magellan was born around 1480 in northern Portugal, likely in the small town of Sabrosa, though the details of his childhood are not fully certain. He came from a noble but not particularly wealthy family and entered the service of the Portuguese court at an early age. As a boy, he was educated in navigation, cartography, astronomy, and seamanship, skills that would later serve him well as an explorer. Like many young men of Portugal's noble class, he became a page at the royal court and soon grew fascinated by the maritime exploits of Portugal's great navigators. Portugal at the time was at the forefront of global exploration, having pioneered trade routes along the coasts of Africa and toward India, and Magellan found himself immersed in this world of maritime ambition.

By his early twenties, Magellan joined expeditions to the East, sailing first to India and later to the fabled Spice Islands, the Maluku archipelago in present-day Indonesia, through the Portuguese route around the Cape of Good Hope. These journeys acquainted him with both the riches of Asia and the complexity of long-distance navigation. Yet his career in Portugal was not without friction. After serving in several campaigns, including military action in Morocco, Magellan fell out of favor with King Manuel I. Denied further command and accused of illegal trading, he turned instead to Spain, Portugal's great maritime rival, to pursue his ambitions.

In 1517, Magellan offered his services to King Charles I of Spain (later Holy Roman Emperor Charles V), proposing an ambitious plan: to reach the Spice Islands by sailing westward, thus avoiding Portuguese-controlled waters in the east. The Spanish crown, eager to break Portugal's monopoly on the spice trade, accepted his proposal. In 1519, Magellan set sail from Seville with five ships, the Trinidad, San Antonio, Concepción, Victoria, and Santiago, and roughly 270 men. His goal was nothing less than to chart a western passage to Asia.

Hardship

The voyage was fraught with hardship from the very beginning. Storms battered the fleet in the Atlantic, and crew mutinies tested Magellan's authority. Yet he pressed on, hugging the South American coastline in search of a strait that would lead to the Pacific. For months the fleet explored treacherous inlets until, in October 1520, Magellan discovered the passage that now bears his name, the Strait of Magellan at the southern tip of South America. The narrow, winding waters were perilous, but they opened into an ocean unlike any Magellan had ever seen. He named it the Mar Pacífico—the "peaceful sea"—for its calm compared to the turbulent Atlantic he had left behind.

Crossing the Pacific proved far from peaceful for the crew. The crossing was unimaginably vast, lasting over three months without fresh provisions. Many sailors succumbed to scurvy and starvation, chewing leather and sawdust to survive. Yet the fleet pressed on, eventually reaching the islands of Guam and then the Philippines in March 1521. Here, Magellan sought both provisions and an opportunity to convert local rulers to Christianity, aligning with Spain's imperial and religious mission.

It was in the Philippines, however, that Magellan met his end. In April 1521, he became embroiled in a conflict between rival local chiefs. Leading his men into the Battle of Mactan, Magellan was struck down by warriors led by the chieftain Lapu-Lapu. His death was a heavy blow to the expedition, but his men carried on under new leadership. After further hardships and the loss of several ships, the expedition was reduced to a single vessel, the Victoria, commanded by Juan Sebastián Elcano. In September 1522, the Victoria returned to Spain with just 18 men, completing the first circumnavigation of the Earth.

As Magellan had succumbed to the attack led by the chieftain Lapu-Lapu he naturally did not witness this triumph, but the success of the voyage confirmed what many had only speculated: that the Earth was indeed round and that its oceans were interconnected. The circumnavigation provided crucial new knowledge of global geography. It revealed the staggering size of the Pacific Ocean, recalibrated European conceptions of distance and trade, and laid the foundation for future maritime empires. Spain now had a claim to the Spice Islands and the prestige of sponsoring the first global voyage, though Portugal would contest these claims fiercely.

Impact

Magellan contributed more than geography to the world's understanding. His expedition demonstrated the practical possibility of circumnavigation, proving that long-distance navigation could be achieved through careful seamanship, astronomical observation, and the use of advanced navigational instruments such as the astrolabe and quadrant. He and his crew also documented winds, currents, and coastlines that would guide sailors for generations. In terms of society, his journey helped to knit together the world's continents into a global network of trade and cultural exchange, albeit one that was often marked by exploitation and conquest.

Unlike some explorers of his era, Magellan did not himself leave behind a written account of his travels. The most detailed records of the voyage came from Antonio Pigafetta, an Italian nobleman who sailed with him. Pigafetta's chronicle is one of the most important documents of the age of exploration, providing vivid details not only of the geography encountered but also of the cultures, languages, flora, and fauna observed.

Without Pigafetta's writings, much of what we know about Magellan's expedition would have been lost. Ferdinand Magellan's life was cut short on distant shores, yet his vision carried forward across oceans. His ambition to connect the world, his courage in the face of mutiny and hardship, and his role in proving the vast scale of the globe make him one of history's most consequential explorers. His voyage, completed in his absence, inaugurated a new era of global history, an age in which continents were no longer isolated worlds but parts of a single, interconnected planet.

Ferdinand Magellan's story closes not with his own return but with the rippling consequences of his vision. Though his death on the shores of Mactan left him absent from the final triumph, the voyage he conceived and set in motion altered the trajectory of human history, proving that perseverance could pierce the unknown, and that oceans, once thought to be insurmountable barriers were in fact vast highways binding the continents together.

The circumnavigation redefined geography, expanded commerce, and opened a new chapter in cultural exchange, for better and for worse, as Europe's expansion reached every corner of the globe. Magellan's name thus endures as both a symbol of bold exploration and a reminder of the human cost of conquest. His expedition was not merely a feat of navigation but the dawn of a global age, and in this, his legacy remains as expansive and enduring as the oceans he first crossed.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here .

Notes:

The pen that carried the voyage.

If Ferdinand Magellan's ships carried his expedition across the oceans, it was Antonio Pigafetta's pen that carried its memory across centuries. A Venetian nobleman who volunteered to join the voyage, Pigafetta kept a meticulous daily record of the expedition. His chronicle, later titled Primo viaggio intorno al mondo ("First Voyage Around the World"), became the most detailed and enduring account of Magellan's journey.

Pigafetta's writings were more than a sailor's log. They were an ethnographic and geographic treasure, documenting not only the route and hardships but also the peoples, languages, flora, and fauna encountered along the way. From the Strait of Magellan to the Philippines, his descriptions vividly depicted unfamiliar worlds that Europeans could scarcely imagine. His account of the Battle of Mactan, in which Magellan was killed, immortalized the event and shaped the narrative of the voyage for posterity.

In Europe, the chronicle captured imaginations at a moment when maps were still being filled in. Published and circulated widely after Pigafetta's return, it gave Europeans a tangible sense of the vastness of the Earth and the diversity of its peoples. The work influenced cartographers, natural philosophers, and writers of the Renaissance, contributing to a more accurate picture of the globe and reinforcing the idea of a single interconnected world.

Without Pigafetta, Magellan's feat might have remained only a line in royal records. Instead, his chronicle transformed the expedition into a legend, ensuring that Magellan's vision and Europe's first true glimpse of a global horizon would never be forgotten.

Myth and legacy of Magellan

Over the centuries, Ferdinand Magellan's name has often been wrapped in myth. Popular retellings sometimes call him "the first man to circumnavigate the globe," a claim that is both true and false. While his expedition was the first to achieve this feat, Magellan himself never completed the journey, as indicated in the main text he was killed in the Philippines in 1521, halfway around the world. It was Juan Sebastián Elcano and the surviving crew of the Victoria who sailed back to Spain, closing the loop. Yet Magellan's vision and leadership set the course that made the achievement possible.

This blurring of fact and legend reflects the power of exploration narratives in shaping historical memory. To many in Europe, Magellan came to symbolize the courage to test the limits of the known world, even at the cost of his life. His voyage became a metaphor for human endurance and the relentless pursuit of knowledge, themes that resonated throughout the Renaissance and beyond.

Magellan's name has endured in geography and culture alike. The Pacific's Strait at South America's tip bears his name, as do the Magellanic Clouds, two dwarf galaxies visible from the southern hemisphere, first noted by his crew. These celestial names reinforce his place not only in the history of navigation but also in the broader story of humanity's relationship with the cosmos.

In truth, Magellan's legacy is more complex than the myth suggests. He was both a daring visionary and a figure of empire, whose voyages helped open pathways for global trade but also paved the way for conquest and colonization. His story embodies both the triumphs and the contradictions of the Age of Discovery, an era when the world became at once larger and more interconnected.

October 5, 2025

A History of Film’s Greatest Bad Guys and What They Reveal

The American Film Institute’s list of the ‘ 100 greatest heroes and villains ’ reflects key trends in American cinematic storytelling and the enduring power of specific character archetypes. In effect, the history of bad guys, villains, and enemies is a fascinating story of cinema and society itself. Cinematic antagonists have evolved from simple one-dimensional figures to complex characters demonstrating a psychological understanding of the audience. From the master criminal Fantomas to the highly-sophisticated cannibalistic serial killer, Hannibal Lecter, we continue to be fascinated by these great villains.

Jennifer Dawson explains.

The Silent Era to Mid-Century

In early cinema, villains were often set apart from the hero with a clear role of creating conflict and testing the protagonists. They were primarily motivated by greed, lust for power, or simple malice. Visual cues focused on their physical appearance to project villainy. As such, the bad guys might have facial scars, stern expressions, or portray albinism. For example, the moustache-twirling villain is traced back to Victorian melodrama and early silent films. Exaggerated gestures and facial hair helped convey the character’s wickedness. Barney Oldfield’s Race for Life released in 1913 is widely cited by film historians as the movie that popularized the iconic image of the melodramatic villain. The villain played by Ford Sterling wears a huge, black mustache and is shown gleefully engaging in devious acts often literally twirling his mustache while plotting.

Another key archetype is the Master Criminal - these are intellectual but purely evil characters. Think of Fantomas and Dr. Mabuse, two of the earliest and most terrifying master criminal archetypes in 20th century popular culture. Essentially, these characters created the model for the modern super villain and criminal mastermind. Fantomas is a character from French crime fiction, a criminal genius whose face and true identity remain unknown. Described as a phantom, he often wears the identity of a person he has murdered. On the other hand, Dr. Mabuse is a character from German fiction. Brilliant and educated, he used his knowledge to destroy society. Other important early archetypes are the Classic Monster with figures like Count Dracula and Frankenstein’s Monster creating fears of the unknown, the supernatural, and the unchecked science.

1930s to 1960s

During this period, villains started embodying greater social and political anxieties. One such example was Mr. Potter in It’s a Wonderful Life, representing the danger of unhindered corporate or economic power. The femme fatale concept also began with women like Phyllis Dietrichson in Double Indemnity using their allure and beauty to manipulate the male hero to his downfall.

Foreign villains in spy thrillers started to feature prominently in early James Bond films like Auric Goldfinger. Later on, psycho villain characters were introduced bringing in more complex, psychologically disturbed individuals who just looked like ordinary guys. Hitchcock’s Psycho, starring Anthony Perkins as Norman Bates, the shy and seemingly normal proprietor of Bates Hotel, explores identity, madness, and the psychological impact of his past.

The Modern Era

Flash forward to the 1970s and beyond, and the audience sees a great shift towards three-dimensional villains with complex histories and sinister motivations. A prime example is Darth Vader, a figure of pure evil who is transformed into a tragic corrupt figure. Hollywood films also frequently use hacking scenes to establish a sense of modern dangerportraying villains as technologically brilliant and highly dangerous individuals. Live Free or Die Hard (2007) dramatically shows a systematic multi-stage cyberattack that takes down America’s transportation, financial, and utility infrastructure.

During the late 70s and 80s, the audience was shown what were basically unstoppable villains. More often than not, they had no clear motive and were pure relentless evil. Michael Myers (Halloween series) and Jason Voorhees (Friday the 13th series) are two of the most recognized and feared protagonists of the horror movie genre. The 1975 film, Jaws, also featured a non-human antagonist in the shape of a great white shark. Films such as The Joker (2019) showcased the rise of characters inspired by chaos or extreme ideologies. Likewise, films now tackle conflict within a corrupted system, institution, or society such as Agent Smith in The Matrix (1999). Psychological thrillers also continued to represent a modern fascination with and fear of the human psyche, mental illness, and deviance. Hannibal Lecter in the Silence of the Lambs (1991) is such an iconic villain because of the extreme contrast between his high culture and barbaric depravity.

The enduring popularity of the film villain suggests that the capacity for evil is not a supernatural force, but a human one. As society grew more complex, so did the vilification of the bad guys evolving from monsters and spies to ideological mayhem and psychological breakdown.

October 4, 2025

Jackie Robinson and Kent Washington: Fascinating Sportsmen, Different Challenges

With the banning of books that detail important historical facts and the silencing of various cultural stories which show the diversity of our once ‘Proud’ nation. It seems even more essential to relay the journeys of American to Americans for context and understanding. Knowing our past history, clearly enables and guides us into the future, ‘for better or worse.’ That is why I chose to discuss the journeys of two athletes and the challenges they endured as ‘firsts.’ Hopefully, readers will either want to learn more about them or relay the details of their stories to others. Erasing or altering historical facts is detrimental in understanding ourselves.

Here, we look at Jackie Robinson and Kent Washington’s stories.

Kent Washington and his translator and coach during a game timeout.

Challenges of Robinson and Washington

In attempting to justly compare these two pioneers’ paths and the situations they endured, it would be irresponsible to favor either person’s journey. The difficulty is to lay out the evidence without allowing bias to influence the reader. Undeniably, both Jackie Robinson and Kent Washington are worthy of our praise for their distinction in history. These gentlemen have endured challenges that we cannot even imagine and only by reading about their achievements are we able to grasp and relive their journey. While most Americans know the story of Jackie Robinson, not as many have even heard of Kent Washington. Thus making the comparison that more interesting and hopefully still attaining a “spirited” discussion.

Jackie’s Journey

Jackie Robinson was one of the most heralded athletes of our time. Known for being the first African American to play in Baseball’s Major League (modern era). Not only did he integrate baseball, but he was really good at it! Coming from the ‘Negro (Baseball) League’ he was already very competitive and talented, that wasn’t in question. His abilities were worthy of him playing professionally in the Major League. The dilemma was whether he could withstand the challenges of the times when African Americans were not accepted in professional sports. Could Jackie endure “Racism” and/or “Racist Behavior” by the fans, opponents and teammates? He clearly understood that he was integrating baseball and that there would be challenges he would have to endure. Special accommodations had to be made on road trips, since he could not stay in certain hotels and eat in certain restaurants (Jim Crow Laws). Some of his teammates were against him playing and refused to play with him. They were upset with the “Press” coverage that it brought as they were looked upon as being compliant in the decision for him to play. As well as how they travelled and where they stayed on road trips. Opponents driven by racism were enraged at the mere thought that a African American could compete in their league. Pitchers often threw at him purposely and other players used unsavory tactics to injure and dissuade him from continuing. Fans were incensed that a African American was even allowed to play on the same field as white players. Taunting and hateful screams from the stands were commonplace during games. Taking all of this into consideration Jackie agreed to “break the color barrier” and play.

Kent’s Journey

Kent Washington, is the first American to play professional basketball behind the “Iron Curtain.” He played in Communist Poland from 1979-83 during a tumultuous social and political time. The challenge of being discriminated against (he was the only Black person many Poles had ever seen) was complicated by a lifestyle that was far below the standard he was used to. The locker room in the practice facility was underwhelming. Plumbing, refrigeration, electricity and nutrition were problematic, however endurable if he was to stay and play. Basketball rules were vastly different from rules in the USA. Polish, a very difficult language to speak and understand, was a greater challenge. Television and radio were incomprehensible which led to feelings of isolation. Not being able to communicate with family in America because of a lack of international telephone lines was concerning. Living in a single-room in a house, where a Polish grandma took care of him, resulted in miscommunication about washing clothes, food choices, and other daily routines. Another problem for Kent was when “Marshall Law” was implemented, the stores were left bare of all daily items needed to survive. He was given a “rationing card” that served as coupons to buy such things as butter, flour, soap, toilet paper, detergent, meat and other basic needs. Standing in long lines for items was a daily routine in Poland during this time. But, if he wanted to play basketball this would be his “new” life!

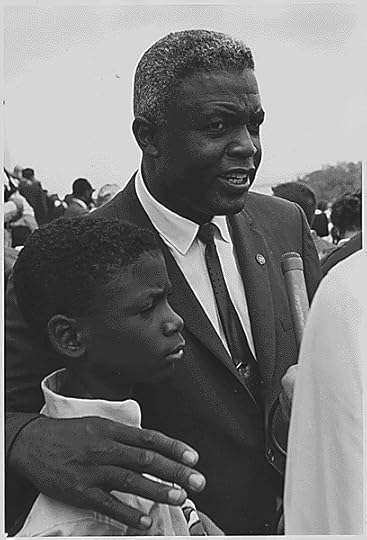

Jackie Robinson and his son during the 1963 March on Washington.

Character Matters

As one can clearly see, both athletes had to endure burdensome challenges to pioneer their way into history. Jackie had to experience more “racially” motivated encounters. While Kent had to tolerate the daily cultural differences in a Communist society. Both admit that they may not have been the best player representing Blacks, but they were the “right” player for that time!” They had the mindset to understand that their passion and drive were needed to conquer those challenging situations put before them. Jackie had personal support from his family and the backing of thousands of Black people behind the scenes and at the games cheering him on. Kent lacked family support because he was alone in a foreign country. So he used his passion and obsession for basketball to guide him. Regardless of the surrounding environment, these two pioneers had something in their character that separates them from you and I. In Jackie’s case, most would have thrown the bat aside and yelled, “I’ve had enough of this sh…!” and walked away. In Kent’s shoes, many would have gotten on the “first flight home” after they saw the locker room in the practice facility. However, both of them dug down deep to a place that only they knew and met the challenges head on!

Hopefully, the two athletes were justly compared as they were both instrumental in breaking barriers and pioneering a path that others have taken advantage of. Jackie is a national hero and most know the story that follows him. Kent not as much, however hopefully now a comparison can be made. Which athlete endured more? Both have books that show you their respective journeys in case you need more evidence.

Jackie Robinson’s “I Never Had It Made” is his autobiography and Kentomania: A Black Basketball Virtuoso in Communist Poland, is Kent’s memoir.

October 2, 2025

Major General Lewis “Lew” Wallace

Lew Wallace was the youngest Major General in the Union Army at the time of his appointment early in the Civil War, which is especially interesting since he never went to West Point. His father was a lawyer and served as Governor of Indiana, while his grandfather was a Circuit Court judge and congressman. Born in Indiana in 1827, Wallace possessed natural talents in writing and drawing. Although he studied law and briefly served as a second lieutenant during the Mexican War, he did not see any action. Subsequently, he ventured into various pursuits such as publishing a newspaper, practicing law, organizing a Zouave unit militia, and being elected as a state attorney. However, his book did not achieve success.

Lew Wallace wrote Ben Hur, the best-selling American novel of the 19th century, and its success made him a wealthy and internationally famous man. Years earlier, he had been an acclaimed war hero and the youngest major general in the Union Army, before losing his command when blamed for the near disaster at the Battle of Shiloh. Wallace would devote much of his life to trying to clear his name of that charge.

Lloyd W Klein explains.

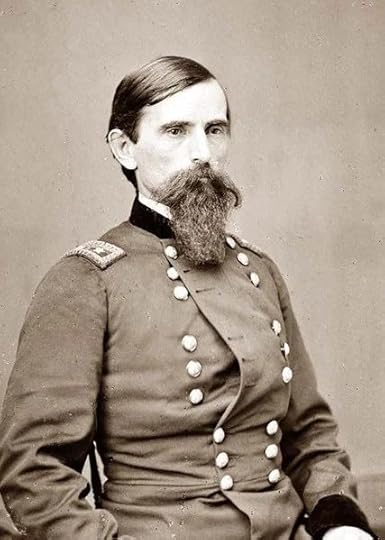

Lewis Wallace.

Civil War

The outbreak of the Civil War brought about significant changes in Wallace's life. As a staunch supporter of the Union, he switched his party allegiance and demonstrated exceptional skills in recruitment. Lew Wallace commanded the Indiana Zouaves, 11th Indiana Regiment Infantry. The 11th Indiana Infantry Regiment was organized at Indianapolis on April 25, 1861, for a three-month term of service, then reorganized and mustered in for the three-year service on August 31, 1861, with Col. Lewis Wallace as its commander. He served as Indiana's adjutant general and eventually assumed command of a regiment, despite lacking formal military education. In June 1861, he led a successful skirmish, resulting in his promotion to brigadier general and the command of a brigade.

Although he did not participate in the battle, he was entrusted with the command of Fort Henry by General Henry Halleck as the Union advanced towards Fort Donelson. Despite Grant's orders to remain on defense, Wallace took the initiative to launch a counterattack, preventing the enemy from escaping and reclaiming lost ground. His actions during the Battle of Fort Donelson earned him a promotion to major general at the age of 34.

Wallace commanded a brigade of volunteers at the Battle of Fort Donelson in Tennessee in February 1862. After his initiative and boldness had help secured the Federal victory and the capture of the entire Confederate army there, he was promoted to major general, making him the youngest major general in the Federal army.

Shiloh

Shiloh (April 6–7, 1862) was the place where Grant and Sherman came into their own, but it was almost the end of their careers. PGT Beauregard planned a surprise advance and attack at Pittsburg Landing, on the west bank of the Tennessee River. Exactly how involved Albert Sidney Johnston's role in the planning of the battle has been a subject of controversy. Larry J Daniel argues that Johnston was ill-equipped for the task and lacked the necessary skills. The northern newspapers exaggerated the nature of the surprise at the time. Although there was no entrenchment, Sherman had received prior warning and some elements of the army quickly discovered the southern lines. Despite facing early setbacks, Sherman displayed remarkable tenacity and skill, proving to himself and others that he possessed the emotional and cognitive abilities required to lead an army.

At the time of the battle, Brigadier General Lew Wallace commanded a division under Major General Grant. On April 6, 1862, Confederate forces under Albert Sidney Johnston launched a surprise attack against Grant’s army near Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee. Wallace’s division was stationed several miles away at Crump’s Landing, north of the battlefield. When the Confederate attack began, Wallace received orders to move his division to support the Union line.

Grant claimed he ordered Wallace to take a specific route that would bring him directly into the Union right flank. Wallace, however, had already set off on a different route—one that made more sense based on the situation earlier that morning and where Union forces had been positioned. Wallace’s division was at Crump's Landing, five miles north of the Union line at the start of the battle. When the battle opened, Grant took his steamboat, Tigress, south to Crump's Landing, where he ordered Wallace to prepare his division to move, but did not specify the route to be taken.

Wallace did not initiate the movement of his division until noon. He then marched his forces towards Sherman's location, utilizing a road near the river. At 2:00 pm, a messenger informed Wallace that he had taken the wrong road. Wallace believed that he was supposed to reinforce Sherman and McClernand at their original camps, unaware that these divisions had been pushed back towards Pittsburg Landing. Consequently, Wallace found himself behind enemy lines and had to retrace his steps. As a result, he did not arrive on the first day of the battle.

He was eventually ordered to turn back and take another route, which cost several hours. His division did not arrive in time to participate in the fighting on the first day of the battle.

Much of the responsibility for the near disaster at Shiloh was pinned on Wallace. As the battle unfolded, commanding general U.S. Grant ordered Wallace to bring his men to the front. Unaware that the Federals had been driven back from their original position, Wallace took the road leading to where they had been before the battle began. Once he learned that the road he was on was taking him away from the army he was supposed to reinforce, rather than toward it, he countermarched his command and took a different road. The delay prevented Wallace from reaching the battlefield until the first day’s fighting had ended. Grant was furious, insisting that his orders specifically directed Wallace to take the other road. Wallace denied the claim, saying the orders had given no directions as to which road to take, and that he had taken the one that he believed would bring him to the action quickest.

In the confusion of the battle the written order was lost, so that what it actually said will never be known. But the blame nonetheless fell on Wallace and he was relieved of command. After the battle, Grant was unsure why Lew Wallace’s division did not arrive when and where he expected it.

Wallace’s men finally arrived late in the day and participated in the Union counterattack on April 7, helping turn the tide in the North’s favor. However, the damage to Wallace’s reputation had been done. Had he arrived earlier, his command of 5000 men might have assisted at the Hornet’s Nest, perhaps saving some of those from surrendering.

On the second day of the battle, the Army of the Ohio, led by Don Carlos Buell, arrived, along with Lew Wallace's division. The Union forces launched a successful counterattack, taking advantage of the Confederate lines, which had become disorganized and outnumbered. The fortunes of the battle shifted in favor of the Union, as Beauregard's men became entangled and exhausted. The Union forces pushed the Confederate lines back entirely, securing a significant victory.

The Controversy

Wallace, deeply wounded by the long-standing criticism, defended himself publicly and privately for decades. He claimed that Grant’s original orders were vague and that he acted in good faith. Wallace wrote letters, articles, and memoirs attempting to clear his name. In one pointed comment, he said: “I have been held responsible for a disaster I did not cause, and prevented from earning honors I might otherwise have won.” He also believed that politics and Grant’s rising prominence after the war made it unlikely that Grant would ever admit error or to clear him.

Grant in Battles and Leaders (1885) was sharp and critical of Wallace. He portrayed Wallace as having misinterpreted orders and delayed his movement to the battlefield, suggesting that Wallace’s failure to arrive on April 6 was a significant lapse that could have cost the Union the battle. This account echoed the prevailing narrative at the time—that Wallace was slow, took the wrong road, and failed to support his commander in a crisis.

In his Personal Memoirs (1885–1886) written while dying of cancer and racing against time, Grant’s tone softened. He still repeated the version of events that Wallace took the “wrong road” and had to be redirected, but he avoided assigning overt blame. He did not accuse Wallace of incompetence, nor did he suggest malice or dereliction of duty. Grant showed greater understanding of the confusion and fog of war. He acknowledged that Wallace believed he was following the correct route based on earlier assumptions about Union positions. Though Grant didn’t retract his earlier criticism, he presented the episode in a more even-handed, factual way, without the sting of his previous judgment. In a footnote, Grant acknowledged learning from Ann Wallace, the wife of General William H.L. Wallace (not related to Lew, who had been killed at Shiloh), that Lew Wallace’s division had taken a different route—presumably the one that made sense earlier in the day when Union lines were thought to be farther forward. This new information shaped Grant’s perception of the event, and he included it in his memoirs. Grant's memoirs, specifically on page 286, contain his admission that Lew Wallace's actions were understandable.

Modern historians tend to side more with Wallace, attributing the delay to ambiguous orders, a rapidly changing battlefield, and the primitive state of Civil War communications and maps In hindsight, both men were partly right: Wallace did what he thought was correct based on initial orders, and Grant had reason to be frustrated when desperately needing reinforcements. But Grant never formally or publicly admitted Wallace had done nothing wrong, and Wallace never felt vindicated in his lifetime.

After Shiloh

Following the battle, Halleck relieved Wallace of his command, although it is usually suggested that this was done at the behest of Grant, although there is no documentary evidence of that. Wallace then took charge of organizing the defenses of Cincinnati and northern Kentucky. However, in March 1864, he returned to command as the leader of the VIII Corps, with headquarters in Baltimore.

In July 1864, a small force under his command was able to sufficiently delay Confederate General Jubal Early at the Battle of Monocacy in Maryland that he may have saved Washington D.C. from capture. Nevertheless, the cloud of the Shiloh controversy still hung over him and would for the rest of his life.

Battle of Monocacy

Early's advance into the Shenandoah Valley and subsequent movement into Western Maryland in 1864 encountered a significant obstacle in the form of Lew Wallace's defense at Monocacy, just outside Frederick, Maryland. At this time, General Robert E. Lee had established his forces in entrenched positions at Petersburg and Richmond, while a Confederate army contingent approached Washington DC. However, the only opposition in their path was a smaller force of inexperienced Union infantry, led by the disgraced General Wallace. This outfit had no battle experience, and all of the resources were going to Grant. His 2300 men were mostly 100-day men: a true backwater command.

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, General Ulysses S. Grant dispatched 3,500 men under General Ricketts to support Wallace. Nevertheless, there were virtually no other Union army units positioned between Frederick and Washington DC. Wallace understood the need to delay Early's advance until a more substantial defense could be organized.

Without receiving any specific orders from his superiors, Wallace made the strategic decision to position his forces along the Monocacy River, a few miles south of Frederick. This defensive stance aimed to protect the routes to both Baltimore and Washington DC. Following several skirmishes, a full-scale battle took place on July 9. Despite being heavily outnumbered, with Early's forces totaling 16,000 compared to Wallace's 4,500, the Union army held its ground. Even a cavalry attack failed to dislodge them, despite the Confederates attempting to outflank the Union forces. Eventually, the Confederate infantry executed a double envelopment maneuver, forcing the Union army to retreat across a stone bridge. Remarkably, the Union army survived five attacks from one of the most skilled division commanders in the Confederate army at that time. After 24 hours of intense fighting, the Union forces were compelled to fall back. Early's losses amounted to approximately 800 men out of the 14,000 engaged, while Wallace's forces suffered 1,300 casualties out of their 5,800. Wallace subsequently retreated to Baltimore. However, Early's delay in breaching this defensive line provided crucial time for the fortification of Fort Stevens. In his memoirs, Early himself acknowledged the critical impact that the Battle of Monocacy had on his ability to launch an attack on Washington DC.

The disgraced general, despite his valiant stand, initially faced blame from General Grant for yet another error. Consequently, following the Union's defeat, he experienced a brief demotion. Grant promptly relieved Wallace of his command, appointing Edward Ord as the new commander of the troops. However, once Federal officials recognized Wallace's accomplishments, he was reinstated to his position. Grant, in his memoirs, generously acknowledges Wallace's contribution. It was only later realized that, despite facing overwhelming odds, Wallace had bought crucial time that ultimately saved Washington DC. Although the battle at Monocacy was relatively small, its impact was significant. The engagement effectively halted General Early, providing Washington with a day's worth of time to secure reinforcements. This delay cost Early the initiative, from which he could never fully recover. The subsequent battle near Washington DC at Fort Fisher proved unsuccessful. Sheridan pursued Early back into the Shenandoah Valley and defeated him in multiple battles, most notably at Cedar Creek. Furthermore, the preservation of Washington influenced the course of the War and played a role in Lincoln's re-election. Wallace's actions at Monocacy should have been sufficient for Grant to recognize and revive his career.

Instead, Grant entrusted Wallace with non-command responsibilities. He sent Wallace to Texas in 1865 to negotiate a surrender with Kirby Smith. Wallace also served on the Lincoln Conspiracy Commission and headed the Wirz Commission. Later, he assumed the role of governor of the New Mexico territory, served as a minister to the Ottoman Empire, and, of course, became an esteemed author of a significant piece of American literature.

Post Bellum Activities

After the war, Wallace briefly accepted an appointment as general in the Mexican army before returning home to Indiana to resume his law practice and politics. He was defeated in two runs for Congress, but his loyal service to the Republican party (and to candidate James Garfield) earned him an appointment as Territorial Governor of New Mexico. Afterwards, he was appointed U.S. Minister to the Ottoman Empire (succeeding his former Confederate adversary James Longstreet).

Governor Of New Mexico Territory

Billy the Kid, also known as Henry McCarty, adopted the alias William H Bonney, which was not his true name. Despite his young age of 21, he had already taken the lives of 21 men before his own demise. Although his connection to Lew Wallace and the Civil War was not direct, it provides an intriguing insight into the historical context of that era.

At the tender age of 15, McCarty found himself orphaned. His first brush with the law occurred at 16 when he was arrested for stealing food in 1875. Merely ten days later, he committed another offense by robbing a Chinese laundry. Although he was apprehended, he managed to escape shortly after. Fleeing from the New Mexico Territory to the neighboring Arizona Territory, McCarty effectively transformed himself into an outlaw and a federal fugitive. It was during this time, in 1877, that he began using the name "William H. Bonney".

Following an altercation in August 1877, Bonney took the life of a blacksmith, making him a wanted man in Arizona. He subsequently returned to New Mexico and joined a group of cattle rustlers. Bonney gained notoriety in the region when he became a member of the Regulators and participated in the Lincoln County War of 1878. Alongside two other Regulators, he was later accused of killing three individuals, including Lincoln County Sheriff William J. Brady and one of his deputies.

Bonney's notoriety reached new heights in December 1880 when his crimes were reported by the Las Vegas Gazette and The Sun in New York City. Sheriff Pat Garrett successfully apprehended Bonney later that month. In April 1881, Bonney stood trial and was convicted for the murder of Brady. He was sentenced to be hanged in May of the same year. However, on April 28, Bonney managed to escape from jail, killing two sheriff's deputies in the process. He remained on the run for over two months before Garrett eventually caught up with him. On July 14, 1881, at the age of 21, Bonney was shot and killed by Garrett in Fort Sumner. It is worth noting that rumors circulated suggesting that Garrett did not actually kill Bonney, but rather orchestrated his escape.

Lew Wallace around 1903.

Billy the Kid

Wallace's arrival in Santa Fe on September 29, 1878, marked the beginning of his tenure as governor of the New Mexico Territory. This period was characterized by rampant lawlessness and political corruption, posing significant challenges for Wallace. One of his primary objectives was to address the Lincoln County War, a violent and contentious conflict among the county's residents. Additionally, Wallace sought to put an end to the series of Apache raids on territorial settlers.

In his efforts to restore order in Lincoln County, Wallace took decisive action on March 1, 1879. Recognizing that previous attempts had failed, he issued orders for the arrest of those responsible for the local killings. Notably, one of the outlaws apprehended was Billy the Kid. while governor of New Mexico, Wallace issued the “Wanted Dead or Alive” order for Billy the Kid. Subsequently, on March 17, 1879, Wallace held a clandestine meeting with Bonney, who had witnessed the murder of a prominent Lincoln County lawyer named Huston Chapman. Wallace's objective was to secure Bonney's testimony in the trial of Chapman's accused murderers. However, Bonney had his own demands, seeking protection from his enemies and amnesty for his past crimes. During their meeting, an agreement was reached, with Bonney becoming an informant in exchange for a full pardon. To ensure Bonney's safety, Wallace orchestrated a "fake" arrest and confined him in a local jail on March 20. As agreed, Bonney testified in court on April 14, providing crucial information against those involved in Chapman's murder. However, the local district attorney reneged on the agreement, refusing to release the outlaw. Faced with this betrayal, Bonney managed to escape and resumed his violent activities. In response, Garrett, a friend of Wallace, offered a $500 reward for Bonney's capture. This turn of events raises questions about whether Wallace genuinely intended to grant Bonney the promised pardon or if it was merely a ploy to gain his cooperation. The controversy remains whether or not he offered the bargain cited above.

Ben Hur

Just before leaving for Constantinople, Wallace published a novel he had written during his tenure in New Mexico. That book, Ben Hur, would become the best-selling American novel of the 19th century.

Wallace's literary career was born out of his boredom with studying law, as he openly admitted. Among his various works, his most renowned novel is the historical tale titled "Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ" (1880). This book achieved remarkable success, becoming the best-selling American novel of the 19th century and maintaining that distinction until Margaret Mitchell's "Gone With the Wind" surpassed it. Interestingly, Wallace completed this masterpiece while serving as the territorial governor of New Mexico in Santa Fe. "Ben-Hur" narrates the gripping story of Judah Ben-Hur, a Jewish nobleman who endures false accusations and subsequent enslavement by the Romans after being wrongly convicted of attempting to assassinate the Roman governor of Judaea. The novel not only explores themes of revenge and redemption but also intertwines the hero's journey with that of Jesus Christ.

Wallace had dedicated a significant portion of his life attempting to make amends for his perceived mistake at Shiloh, a theme that he also incorporated into his novel "Ben-Hur.". The novel drew heavily on Wallace’s life experience and the Shiloh controversy, particularly the sting of misunderstanding, unjust blame, and the long quest for redemption, which deeply influenced the emotional and moral fabric of the novel. The themes of Injustice and vindication, and the journey toward forgiveness, are the underpinnings of the novel. Wallace felt he had been wronged at Shiloh, unfairly blamed for failing to support Grant in time, and branded with a stain on his military career that haunted him for decades. The emotional core of Ben-Hur is the story of a man undone by injustice, who fights for redemption and meaning, and is a deeply personal reflection of Lew Wallace’s own life journey, including his painful legacy from Shiloh.

In Ben-Hur, the central character, Judah Ben-Hur, is a man falsely accused of attempted murder and condemned to slavery. Like Wallace, Ben-Hur spends much of his life struggling to restore his honor and find his place in a world that had cast him aside. Wallace was a deeply reflective man, especially later in life, and came to see personal injustice in a larger moral and even spiritual context. In Ben-Hur, Judah ultimately finds peace not through vengeance but through an encounter with Christ, which reshapes his understanding of justice, mercy, and purpose. This reflects Wallace’s philosophical reconciliation with the past—though he never fully forgave Grant, he found a higher peace through faith and writing. The famous chariot race, where Ben-Hur defeats his rival Messala (a stand-in for betrayal and empire), is often read as a metaphor for triumph over false judgment and humiliation. While not a literal retelling of Shiloh, it’s a narrative inversion: where Wallace had lost public esteem, Ben-Hur regains it, spectacularly and righteously.

Later in life, Wallace acknowledged that his religious searching and his internal struggles—including those tied to Shiloh—helped shape Ben-Hur. He once said: “The consciousness of having been wronged… became a sort of spur. It made me want to show that I was capable of something more.”