Martin Shaw's Blog, page 10

March 23, 2020

‘Herd immunity and let the old people die’ – Boris Johnson’s callous policy and the idea of genocide

On 17 March, when the extent of the British government’s failure to protect the population from the coronavirus had become clear, the respected political commentator Ian Dunt tweeted, ‘The Conservative party is not composed of genocidal murderers. They are not trying to cull the population’, commenting that it’s ‘depressing that this needs saying. … I’m seeing way too much of this on my timeline.’ In justification he continued, ‘If the Tories were genocidal murderers, then the very last group they would target are older people, because that is their actual voter base.’ A couple of political scientists made the same point.

These comments don’t read so well now that Dominic Cummings, Johnson’s chief of staff and his principal strategist since the days of Vote Leave in 2016, is credibly reported as having stated at the end of February that the Government’s strategy was ‘herd immunity, protect the economy and if that means that some pensioners die, too bad’; or as summed up even more succinctly by a senior Tory, ‘Herd immunity and let the old people die’. It seems that the voters, or ‘some’ of them, were dispensable after all; there would always be more where they came from, perhaps from slightly younger people (the Wetherspooners) grateful not to have had their freedom to consume disrupted to protect the elderly.

But where does that leave ‘genocide’? I work on the topic, and I have to say that even after researching the role of Dominic Cummings in Brexit, and despite his notorious interest in eugenics, I didn’t quite see us getting into a situation where this accusation could be made even half seriously, still less that I would (as an over-70) be part of the supposed target group, probably condemned like many older Italians to take their chances at home (should I get the virus) because the minimal supplies of critical care beds, ventilators and nurses would be dedicated to people in their 50s and younger.

Nevertheless once Johnson said on This Morning on 5 March that ‘one of the theories is, that perhaps you could take it on the chin, take it all in one go and allow the disease, as it were, to move through the population, without taking as many draconian measures. I think we need to strike a balance’, and this segment of the interview was widely circulated, it was obvious that something was up and that Cummings’ fingerprints were all over it.

When the head of No. 10’s Behavioural Policy or ‘nudge’ unit, the social psychologist Dr David Halpern, then put the term ‘herd immunity’ into the public domain, I recalled Michel Foucault’s idea of ‘biopower’ and his explanation that in modernity, ‘power is situated at the level of life, the species, the race, and the large-scale phenomena of population’ (The Will to Knowledge, p. 137). Clearly, modern epidemiology in general operates at this level (if we understand ‘race’ as the human race); what Foucault explained was that ‘genocide is the dream of modern powers’ in this condition.

I think Foucault particularly had in mind the rulers of mid-twentieth century totalitarian states, but it seems that, as with the nationalist-racist fantasy of Brexit, Johnson-Cummings also had the ‘dream’ of planning to allow ‘some’ to suffer or in this case die for the good of the race. One hundred thousand deaths might have been acceptable, apparently, even though, in a supreme irony, the Chinese Communist dictatorship, heirs to Mao Zedong – author of the ‘Great Leap Forward’ during which between 15 and 45 million died in 1958-61 – had restricted deaths to barely 3,000.

There is a debate about whether the famine which Mao’s policies caused was actually genocidal. Michael Mann argues that there was no genocidal intent in Mao’s fantasy schemes for crash collectivisation and backyard industrialisation which precipitated mass death. The policy was, rather, like Stalin’s earlier ‘terror-famine’ centred on Ukraine, an example of a ‘callous revolutionary policy’ rather than genocide. We might, however, argue that despite these origins, it became genocidal as Mao and the leadership which was in thrall to him doubled down on then policy and allowed the toll to escalate to a level unparalleled in modern history.

‘Callous revolutionary policy’ also sounds about right for Cummings-Johnson (you’ll notice that I can’t quite decided which way round to pair them). But unlike Mao, limits to callousness were obvious from the start. Johnson had gone on from his ‘on the chin’ exposition to state that ‘I think it is very important, we’ve got a fantastic NHS, we will give them all the support that they need, we will make sure that they have all preparations, all the kit that they need for us to get through it. But I think it would be better if we take all the measures that we can now to stop the peak of the disease being as difficult for the NHS as it might be, I think there are things that we may be able to do.’

So the issue was always, how many deaths are acceptable and with what ‘balance’, as Johnson put it, with harm to the UK economy? We have subsequently learnt that when the Imperial College study reported that the ‘herd immunity’ strategy would lead to 250,000 deaths with ‘mitigation’, 510,000 without, Cummings realised that the price was too high and became a firm advocate of ‘suppression’ which the Imperial authors clearly showed was the only alternative. The Government then changed tack and their Chief Scientific Advisor, Sir Patrick Vallance, talked of the ‘hope’ that excess deaths would be limited to 20,000. But despite Cummings’ support for suppression, Johnson continued to vacillate, and a University College London study has now shown that we may expect 35-70,000.

It could be argued that the implicit limits, and especially the retreat, demonstrate that there was never any genocidal intent. However Johnson remains determined to tolerate a situation in which tens of thousands of people will die unnecessarily from his policies, despite having had relatively successful examples of early suppression from China, South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan. The supposed ‘grown-ups in the room’, Vallance and the Chief Medical Officer, Sir Chris Whitty, have been prepared to go along with this strategy, despite knowing of the horror caused by Covid-19 in China, Italy and elsewhere and the depletion of the National Health Service’s resources.

All of this will be the stuff of future research and, surely, public enquiries. The most lenient judgement on those responsible will probably emphasise wilful ignorance and denial of the nature of the disease, over-emphasis on superficial ideas such as that most cases were ‘mild’ (ignoring the fact that in China, the non-severe disease included many ‘moderate’ cases, more serious than seasonal flu); that only the over-70s and those with previous conditions were ‘vulnerable’ and that these could be ‘cocooned’ (ignoring the fact that in Italy, hospitals were full of the under-60s); and that the NHS would cope (despite chronic underfunding and understaffing). The nudge unit’s advice that the population would become bored with restrictions, if introduced too soon, will surely be another focus of attention. Another social-psychological idea, group-think, is likely to play a prominent role in explaining what went wrong.

The base line for such enquiries should, however, be political. Johnson-Cummings’ primary reason for being prepared to tolerate mass death is not to save the economy, businesses or jobs as such (their Brexit policies have demonstrated their willingness to accept substantial economic damage to achieve their political goals), but to get the political balance which retains the Government’s (suitably modified) electoral base.

Rather than resorting to genocide theory, the study of modern war may provide better clues. There is a parallel here with governments’ tolerance of life-risk in war, which happens to be my other area of expertise. Since the disaster of Vietnam, Western governments’ military interventions have ever more sought to calibrate the life-risk to which they expose both their own citizens in uniform and civilian populations with the political risks they themselves take in pursuing conflict.

The bottom line, we have found, is that while casualties are acceptable if the overall policy aims are widely accepted and the outcomes successful, public opinion is intolerant of failure and above all of unnecessary death. If that is true when the casualties are military personnel who have signed up for life-risks, how much more will it be true now that they are innocent civilians.

February 13, 2020

Jamaica flight: Johnson/Cummings believe that symbolic racist cruelty will send the ‘red wall’ voters the message that the Government is on their side

[image error]

After a court judgment forced the government to remove more than half the people from the recent deportation flight to Jamaica, the prime minister’s press secretary said that the reaction to the case showed that ‘certain parts of Westminster still haven’t learned the lessons of the 2019 election’.

What this tells us is that for Johnson and his chief of staff, Dominic Cummings, the Tories’ success is winning Northern and Midlands seats (the so-called ‘red wall’) from Labour, was not primarily because of voters’ desire for better infrastructure but was, at base, about racist hostility to immigration and ethnic diversity.

This should not be surprising because the same team won the 2016 referendum by serving up a flood of racist anti-migrant propaganda and reprised the crude propaganda, with xenophobic language about Europeans thrown in, during the General Election itself. Remainers have often been criticised for calling Leave voters racist – but that is what Johnson/Cummings themselves believe! Labour leadership contender Lisa Nandy may be right in principle that we should ‘listen’ to the Northern voters who backed Leave and switched to the Tories – but we should be careful to hear more than the recycling of Cummings’ propaganda.

Racist symbols like the deportation flight give Johnson cover to ditch Cameron’s and May’s unworkable ‘tens of thousands’ target for immigration numbers, despite the continuing support for this from groups like Migration Watch, and introduce small changes to the immigration system like reducing the earnings threshold from £30k to £25.6k. However as I argued when Johnson/Cummings took power, there is no real liberalisation of the ‘hostile environment’ system, just a recalibration. The Windrush flight reminds us of its bottom line.

December 16, 2019

Goodbye Corbyn, destroyed by the Brexit he evaded

In the German film Goodbye Lenin, a loyal supporter of East Germany’s Stalinist regime goes into a coma before the fall of the Berlin Wall and when she comes round, her son goes to extraordinary lengths to pretend that nothing has changed. In the story of the British Labour Party since 2015, a minor left politician with Stalinist leanings is plucked by fate to become leader and is surrounded by supporters who confirm his belief that the Bennite politics he has embraced since the 1970s can be an election winner in the 2010s, becoming a catalyst for the hopes of a new socialist generation. He and they lived in their bubble for four and a half years. But now it has well and truly burst.

Core contradictions

The contradictions of the emerging Corbyn project were apparent when he was elected. He was a socialist influenced by the far left, but like his mentor Tony Benn had no Marxist intellectual formation and was prone to present the evils of capitalism in a conspiratorial and moralising way. He was a man of peace, committed strongly to the Irish and Palestinian causes, but had aligned himself with the militarised wings of these struggles, the Provisional IRA and the Palestine Liberation Organisation (he claimed that he had talked to the IRA’s political wing Sinn Fein to promote ‘dialogue’, but was known as a long-time supporter of their armed struggle). He was an anti-imperialist who was hyper-sensitive to the dangers of US power, but minimised those of Putin’s Russia and the Assad regime in Syria. He was an anti-racist who found it difficult to recognise antisemitism in some of the pro-Palestinian figures he campaigned alongside. He was a man with an attractive ecumenical style, but who operated in narrow political circles.

In 2015 it was possible to believe that Corbyn was the man of the hour, largely because there was no credible alternative. Tony Blair’s phenomenally successful ‘New Labour’ project had run into the sand after his disastrous embrace of the Iraq War in 2003, and expired under the less inspiring leadership of Gordon Brown in 2010. Ed Miliband’s attempt to steer Labour moderately leftwards had been defeated in 2015. The other candidates for Labour’s leadership, the “Brownites’ Andy Burnham and Yvette Cooper and the ‘Blairite’ Liz Kendall, offered no answers to the obvious exhaustion of New Labour.

It was possible to hope that, with leadership thrust upon him, Corbyn might rise to the demands of the hour and offer an open, inclusive approach to the party and the wider socialist, liberal and Green left. He did not. Meanwhile the centre-right of the Labour Party, supported by the Tories and the tabloid press, quickly demonised his leadership, beginning the process of embedding a negative image of Corbyn which would be all too fully exploited in the 2019 election. Corbyn’s baggage, together with his compromised approach to the ‘antisemitism’ crisis which arose in the party under his leadership, gave them ample material, but it was his failures in addressing the existential national crisis of Brexit which fundamentally sealed the fate of the Corbyn project.

Labour, the UK constitution, Scotland and Brexit

When Corbyn was elected, the UK had just gone through the Scottish independence referendum of September 2014, in which Labour had fought alongside the Conservatives to defeat independence by 55:45 per cent. However Labour uniquely paid the price of this success: the Scottish National Party destroyed Labour’s support in Scotland, while David Cameron’s Tories weaponised southern English fear of Scottish independence to achieve an unexpected majority by almost eliminating their erstwhile coalition partners, the Liberal Democrats. Cameron was, moreover, committed to holding a referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU, to which he had rashly agreed in 2013, and which his majority now obliged him to hold.

Neither Corbyn nor the other 2015 candidates seriously addressed either the Scottish or EU challenges in the leadership election, in which the debate focused on socio-economic issues and Iraq. Indeed they all, together with most of the parliamentary Labour party, shared a deep blindness to the remaining deep constitutional challenges of the UK’s flawed democracy.

Blair’s government, to its credit, had addressed two fundamental constitutional issues, the Northern Ireland crisis (with the 1999 ‘Good Friday’ agreement) and Scottish and Welsh devolution, while tinkering with the anachronistic second chamber, the House of Lords (restricting but not removing the representation of hereditary peers), and introducing forms of Proportional Representation in Scottish, Welsh and European elections and in Scottish local government.

However Blair had reformed only the periphery of the UK’s constitution, not only leaving the Lords fundamentally unreformed, but also reneging on Labour’s 1997 election pledge to hold a referendum on PR for the House of Commons, proposals for which had been produced by a Labour-commissioned report chaired by Roy Jenkins. At the same time, New Labour cosied up to, rather than challenging, the other fundamental pillar of Britain’s compromised democracy, the sensational, overwhelmingly right-wing tabloid press owned by Murdoch and other oligarchs.

Labour ignored the PR challenge even when the 2005 election showed its support shrinking to 35 per cent, a level which suggested it was highly vulnerable to Tory resurgence and might soon need Liberal Democrat support to continue in government. When that happened in 2010, the momentum was with Cameron and the Lib Dems sold him their support for something far short of PR, a referendum on the Alternative Vote (which the Tories in turn would actively oppose).

Corbyn and the 2016 EU referendum

Corbyn, like much of the Labour Party, had less interest than Blair in constitutional reform. Yet Scottish nationalism was a fundamental obstacle to his chances of winning power, and Brexit was the defining challenge of his time. Corbyn evaded it as far as possible, but as we now know, it destroyed him in 2019.

One of Ed Miliband’s best decisions had been to refuse to commit Labour to an EU referendum. However after his defeat, the party rolled over and supported Cameron’s bill to hold the vote, introduced before the 2015 leadership election but only finally approved after Corbyn had won. Crucially, Labour did not try to insist on any ‘supermajority’ clause, such as the requirement that 40 per cent of registered electors should support change, which had been imposed in the 1979 Scottish devolution referendum (if this had been introduced, Brexit would have failed, since like devolution it was supported by only 37 per cent of electors).

Corbyn like many Labour MPs on all sides regarded the referendum as unnecessary but inevitable. When it took place in 2016, Labour did not participate in a joint ‘In’ campaign (as it had for ‘No’ to Scottish independence), because of its fear of being tarnished by association with the Tories. Instead, a dedicated but ineffectual Labour pro-EU campaign was led by the former Cabinet minister Alan Johnson, while the cross-party Stronger In was dominated by Cameron. Together pro- and anti-EU Tories claimed almost three quarters of all TV coverage.

Historically Corbyn had been a supporter of what came to be called ‘Lexit’, the left-wing case for exiting the EU in order to have fuller freedom to introduce socialism in the UK. In particular, he believed that the EU’s ‘state aid’ rules restricted a future Labour government. However by 2016 Labour was an overwhelmingly pro-EU party; almost all of its MPs and two-thirds of both Labour members and voters supported Remain.

Corbyn squared this circle by minimal engagement with the referendum: he left the campaign to Johnson and Party HQ, even going abroad on holiday for a week (!) and when he returned speaking to Labour meetings, avoiding interviews with terrestrial TV and the main debates (his only full interview was on Sky; apart from that he appeared on a show where he gave the EU a lukewarm ‘7 out of 10’). In short, the Corbyn strategy was not to invest in the referendum, let Cameron take the blame from Leave voters if (as expected) Brexit was defeated, and if by some chance it won, to fight for a ‘socialist Brexit’ afterwards.

What Corbyn and his circle obviously did not foresee was that the official Vote Leave campaign, led by Boris Johnson and directed by Dominic Cummings, would (like Leave.EU, the secondary Nigel Farage-Arron Banks campaign) major on massive, lurid anti-immigration propaganda in order to turn out racist voters. Someone in Corbyn’s team must have watched the disgraceful racist TV election broadcast which was put out repeatedly over a month, or seen some of the 1.5 billion targeted Facebook ads. But the ‘great anti-racist’ held to his strategy and did not respond to this racist campaign until, finally, Jo Cox was murdered. Only then did he make an oblique reference to the ‘well of hatred’ which had killed her.

Corbyn also took no action against Labour MPs who supported Vote Leave, like its co-convenor Gisela Stuart (who would support the Tories in 2019) and John Mann (later Corbyn’s scourge over antisemitism, who has taken a peerage from Johnson), despite this record of racism, or against Kate Hoey who worked closely with Farage, promoter of the notorious Breaking Point poster.

From the referendum to the 2019 election

This racism of the Leave campaigns, reflected in surveys which showed opposition to immigration as a major driver of the 52 per cent Brexit vote, proved to have a fundamental effect on the Brexit process. As the few Leavers to seriously address the process of leaving had argued, the only credible way to deliver Brexit quickly was to adapt an off-the-shelf solution, modelled for example on the Norwegian relationship with the EU including Single Market membership. This idea had been endorsed by various Leave leaders at different points and it continued the traditional Tory Eurosceptic position of supporting economic union while opposing political union.

However the new Tory leader, Theresa May, author of the ‘hostile environment’ which aimed to deliver Cameron’s annual immigration target of ‘tens of thousands’, rejected this because it would have entailed accepting freedom of movement, which had come to represent unrestricted immigration. Like May, who had also been a nominal Remainer, Corbyn capitulated not only to Brexit but to the demand to end freedom of movement, which was also made by more centrist Labour figures like Miliband.

Corbyn’s first reaction to the referendum result was to call for the triggering of Article 50 to launch the formal two-year withdrawal process; May delayed some months, and Corbyn then led the majority of Labour MPs into voting for this. However her decision to do so before achieving outline agreement with the EU has been widely criticised as a fundamental mistake which boxed the UK into a tight deadline.

May, Corbyn and their teams were united in wholly failing to understand the complexity of the Brexit challenge. She embarked on tortuous negotiations with the EU, but in June 2017 tried to exploit her apparent popularity to achieve a larger majority which would have enabled her to ignore the hard-Brexit right of her party and more easily come to a deal with the EU. The 2017 election proved, of course, the beginning of her downfall and the highpoint of the Corbyn project, as a combination of the popularity of his socio-economic policies and tactical Remainer support propelled Labour’s vote to 40 per cent only just behind the Tories’.

In this context, May and the EU produced the December 2017 proposals including the Irish ‘backstop’ which was needed because the UK proposed to leave the Single Market and the EU’s customs union. This was anathema to the hard-right Tory Brexiters in the European Research Group, who were joined in their opposition in 2018 by the opportunistic Johnson. The epic 18-month parliamentary struggles over Brexit began, and among the electorate, research showed Leave and Remain identities hardening and overtaking party loyalties.

Yet Corbyn believed that since his triangulation had worked in 2017, it would continue to work, so his responses to this drawn-out crisis increasingly satisfied no one. Within the party, even Momentum started to revolt, and Corbyn was very slowly dragged to supporting a second referendum on Brexit while maintaining the fiction of a ‘jobs-first’ Labour Brexit different from the Tory offer.

In Parliament itself, Labour provided the numbers for the opposition to May and, in the end, Johnson, and by summer 2019 finally engaged in the limited cooperation with the SNP, Liberal Democrats and ex-Tory and ex-Labour independents which frustrated Johnson’s greatest affronts to parliamentary authority. But in the end, none of them was prepared to use their combined majority over Johnson to create even an interim government to force through a confirmatory referendum on a Brexit deal. Corbyn is by no means alone in the responsibility for this, which is shared by all the opposition groups. But it is striking that he was happy to vote for an election he was almost certain to lose, condemning the country to Brexit and five years of a Johnson ‘elective dictatorship’, rather than compromise.

Preliminary research on the 2019 election has shown that while Labour’s manifesto support for a new referendum held on to enough Remain voters to prevent a complete wipe-out, it still alienated more Remainers than Leavers (there were many more Remainers in Labour’s electorate to start with) and the combined desertions lost a huge number of ‘Leave’ as well as ‘Remain’ seats (because both groups of dissatisfied abandoned the party in both types of seat).

The other thing which is striking from the recent election is that Corbyn and Labour largely avoided answering the compelling Tory message ‘Get Brexit Done’, offered no equally direct message of its own, and largely left the field free for Johnson’s dishonest propaganda on Brexit. Many Labour candidates – even while asking Remain voters to vote tactically for them – used a standard election address which did not even mention Brexit. Moreover as the Tories, under Cummings’ influence, once again ramped up lurid propaganda on immigration and attacked EU citizens as ‘foreigners’ in the final weeks of the campaign, Corbyn once again failed to respond.

Why Labour lost – not ‘Corbyn’ or ‘Brexit’, but ‘Corbyn’s evasion of Brexit’

It is clear, then, that Labour did not lose ‘because of Brexit’ in the sense that it abandoned its Leave voters. If it had not moved as far as did towards Remain, it would have lost even more badly. Equally, it did not lose ‘because of Corbyn’ in the sense that his personal and political failings, real and demonised, independent of Brexit, were the dominant factor. Labour lost primarily because it had no coherent answer to Brexit and Corbyn manifestly was not a leader with credibility on the issue.

These failings, moreover, go back over four years. They are not Corbyn’s alone, or even just those of his team or faction, but embrace a large part of the Labour parliamentary party including many who oppose him. But they centre on Corbyn.

We can imagine that a different Labour leader might have seriously fought to remain in the EU. The 52:48 margin in the 2016 referendum might even have been reversed. Even if had not been, a strong principled opposition from Labour’s leader to Leave’s racism – such as Sadiq Khan expressed when he charged Johnson with ‘Project Hate’ – could have changed the subsequent dynamics. The Labour leader could have defended remaining in the Single Market, with continuing freedom of movement.

Corbyn and antisemitism

The central charge against Corbyn must surely be that, throughout this whole sorry period, he and his circle evaded Brexit and – when they could not – capitulated to it and its core racist dynamic. A connection is not often made between Corbyn’s posiitons on Brexit and on antisemitism, which is central to most accusations made against his personal political position. But essentially there is much similarity. Just as Corbyn has not called out Brexit racism because of his own sympathy with the project, so he has been slow to call out antisemitism because of his sympathy for Palestinian opposition to Israel.

It is not that Corbyn is a racist or an antisemite; but because of his political positions, neither is he the fearless, consistent anti-racist he claims to be. Everyone in Labour and the liberal left opposed apartheid in the 1970s: you don’t get to be a great anti-racist by taking the easy calls, but by challenging those which arise around positions you sympathise with.

The Labour antisemitism issue is a minefield which there is not space to fully unravel in this article. I understand where Corbyn and his supporters are coming from: pro-Israelis have long tried to define antisemitism in a way which encompasses radical criticism of Israel, proposing that anti-Zionism constitutes a ‘new antisemitism’. In some cases, people who were clearly not antisemitic have been accused of antisemitism.

At the same time, however, opposition to Israel over its treatment of the Palestinians has increasingly been accompanied, in some quarters, by classical ‘old’ antisemitic sentiment. It is always a danger of national conflicts that the other side are racialised – something we can see, indeed, in the racism of many Israeli politicians towards Palestinians.

It was probably inevitable that as opposition from Israel went from being a fairly marginal, specialist campaign to a mainstream position in a major political party, it would attract supporters who were less discriminating in their criticisms of the Jewish state and liable to express their opposition in antisemitic terms. In the fetid world of Facebook and Twitter, this kind of sentiment has ballooned.

Corbyn’s problem has been that he has often not seen, wanted to see, or sufficiently quickly deal with, demonstrably objectionable material. His supporters in the party machine have sometimes tried, whistleblower evidence suggests, to block effective action. Most importantly, Corbyn himself has never tried to coherently and systematically lay out a principled position on Israel and Palestine which would reassure the majority of British Jews who have turned against him. Instead, as with Brexit, Corbyn has evaded the challenge, opened himself to the charge of tolerating racism, and confirmed the suspicions of his critics.

November 15, 2019

Towards Another ‘Turkey Week’? The Threat of Strategic Racism in the UK General Election

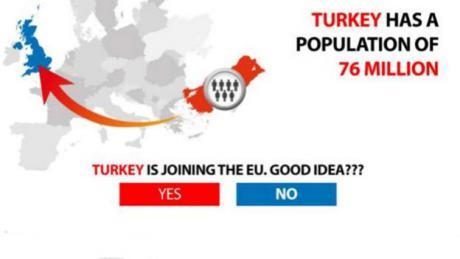

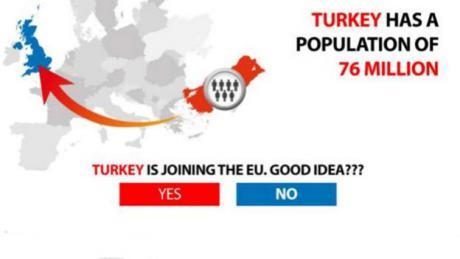

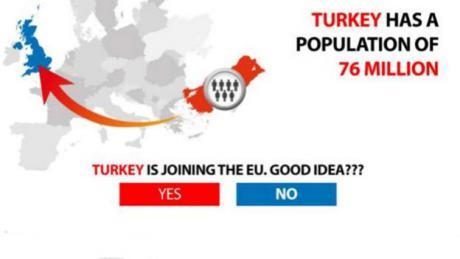

[image error] Endemic racism in the two main parties is a serious problem, but could be dwarfed by the Tories’ strategic moves towards weaponising immigration and the fear of others, as in this new Facebook ad.

Racism is widely recognised as a serious problem in the UK General Election, as shocking comments by individual candidates and party supporters are reported, reflecting what many observers regard as different forms of endemic racism in the two main party milieux – chiefly antisemitism in Labour and Islamophobia among Conservatives. The main charge made against the party leaders is that they have failed sufficiently address expressions of hostile sentiment towards particular groups by their supporters, particularly online, i.e. that they are failing to take racism seriously.

In the case of Jeremy Corbyn, it is suggested that he has failed to manage antisemitism, and sometimes that this is because he personally shares some antisemitic attitudes, instanced by his failure to recognise an antisemitic mural and comment about Zionists’ failure to appreciate English irony, both before he became leader. In the case of Boris Johnson, historic racist comments on ‘piccaninnies’ were reinforced by a recent Telegraph column about Burqa-wearers appearing like ‘letterboxes’, on which he doubled down during the Tory leadership election. Whereas Corbyn has mainly appeared embarrassed by the accusations, while denying antisemitism, Johnson has continued to signal the substance of his statements to his supporters, even while denying Islamophobia.

Strategic racism – the 2016 referendum and the current election

However it is wrong to think that these matters, troubling as they are, represent the main racist threat in the election. As I suggested four months ago, in the aftermath of Johnson’s election as Tory leader and appointment of Dominic Cummings as his principal advisor, a different kind of political racism is likely to take centre stage. Then Tim Shipman and Caroline Wheeler reported on 3rd November, ‘Tory sources predict Cummings and [Paul] Stephenson will revisit some of their greatest hits from the referendum campaign, including “Turkey week” in which they highlighted the potential for Turkish accession to the EU. This time it would involved drawing attention to the policy passed at Labour conference. “His official policy is open borders so Turkey week isn’t far away,” said one source.’

In 2016 Cummings directed the Vote Leave campaign, headed by Johnson, Gove and the ex-Labour MP Gisela Stuart (who is supporting the Tories in the current election), which systematically and effectively exploited racism on a massive scale.

They ran an election broadcast, which scandalously aired on all major TV channels, with a racist theme straight out of Enoch Powell’s 1968 speech, in which a vulnerable old white women was reduced to tears as a surly foreigner barged ahead in A&E.

VL targeted, according to Cummings, 1.5 billion pieces of propaganda at Facebook users, mostly at 7 million people in the final stages of the campaign. The main themes of this propaganda were that ‘5 million more immigrants’ were coming to the UK, while ‘76 million Turks’ would be able to come after Turkey ‘joined’ the EU (which they knew was not going to happen). The otherness of poor, mainly Muslim Turks was mostly implicit, like a lot of antisemitic sentiment, but no less effective for that.

While the material varied for different segments of the audience, the cruder, habitually non-voting racist was a particular target. VL was credited with bringing out 2 million who didn’t normally vote – the margin of victory was 1.3 millions.

Although many observers wrongly identified Nigel Farage and Leave.EU as the main source of racism in the referendum campaign, Sadiq Khan accused Johnson of ‘Project Hate’, and in his recent memoirs David Cameron (having kept quiet at the time) ‘effectively accused Boris Johnson of mounting a racist campaign by focusing on Turkey and its possible accession to the EU. “It didn’t take long to figure out Leave’s obsession,” he writes. “Why focus on a country that wasn’t an EU member? The answer was that it was a Muslim country, which piqued fears about Islamism, mass migration and the transformation of communities. It was blatant.” Indeed, Cameron echoes the explicitly racist Conservative campaign slogan used in Smethwick in 1964: “They might as well have said: ‘If you want a Muslim for a neighbour, vote “remain”.’

A week after Shipman and Wheeler’s report, Michael Gove launched the first salvo of the new campaign in The Times: ‘Labour is now explicitly in favour of unlimited and uncontrolled immigration. And Nicola Sturgeon is their staunchest ally. The Corbyn-Sturgeon policy is extreme, dangerous and out of touch with the British people. It would mean massive pressure on public services – creating a shortage of school places, putting a huge strain on the NHS and increasing demand for housing. It would also mean Britons are less safe, as a Corbyn-Sturgeon alliance wouldn’t put in place the controls necessary to stop criminals crossing our borders.’ On cue, Conservative Twitter accounts and Facebook advertising began to pump out similar propaganda.

Responding to strategic racism

This strategic weaponising of racism is quite different from the endemic racism among sections of the main parties’ supporters, and the political charge we should make against it is the opposite: rather than failing to take racism seriously, strategic racism acknowledges the seriousness of racism by utilising it for electoral gain.

So we face a double challenge of racism in this election. So far the debate has focused on its endemic forms, and particularly on whether anti-Tories and anti-Brexiters can vote, even tactically, for a Labour Party which is compromised by its failure to eliminate antisemitism, even if the Conservatives are contaminated – perhaps even more broadly – by Islamophobia.

However the threat of strategic racism alters the stakes. Racism looms towards the very centre of the election. Corbyn, for all his faults, is not weaponising antisemitism; indeed he wishes the whole issue would go away. Johnson, on the other hand, is already exploiting and arousing fear of migrants, anxiety about migration and xenophobia, in a calculated and determined way. He may yet reprise 2016’s implicit anti-Muslim and anti-European material.

If that campaign is anything to go by, the biggest danger points will probably be at what one of Shipman’s and Wheeler’s informants calls ‘squeeky bum time’ – if and when the Tory lead falls below the level likely to guarantee a majority. In any case, on the 2016 model, the worst material will be pumped out most incessantly in the final week or ten days, to drum out voters who might otherwise stay at home.

This election is now about whether a party which is prepared to mobilise fear and hate will win an overall majority, to deliver a Brexit in which racism is already baked in by years of UKIP campaigning as well as Vote Leave and Leave.EU. It is about reawakening anti-immigrant sentiment which has calmed in the last three years, as neither the Tories nor Farage have bothered to keep it on the boil. It is about a party prepared to provoke the kind of active hostility which resulted in serious racist abuse and violence towards Europeans and others after 2016.

The anti-Conservative forces in this election, who are mostly content to face Johnson’s hard-right Tories in a divided way, have hardly come to terms with the ruthlessness of his and Cummings’ machine and how it is prepared to win. They need to wise up, and quickly.

July 25, 2019

Dominic Cummings’ appointment reminds that whatever liberal gestures Johnson makes on immigration, he is focused on winning an early election – and will reach for whatever dirty, racist weapons he needs

[image error]Boris Johnson is making liberal gestures on race and immigration – appointing the largest number of cabinet ministers of BME (black and minority ethnic) background, refusing to commit to cutting immigrant numbers after Brexit, even repeating his support for the idea of an amnesty for irregular immigrants. Some liberal observers see Johnson’s position as more promising than Theresa May’s notorious obsession with reducing immigration numbers, blamed for the red line on freedom of movement which determined the shape of her Brexit. Johnson may even try to pivot, Tom Kibasi suggests, to open-ended transitional membership of the Single Market – with continuing freedom of movement – while a future trade relationship is negotiated.

However Johnson’s appointment of Dominic Cummings, who ran the 2016 Vote Leave campaign for which Johnson was the figurehead, suggests sharp limits to his liberalism. Cummings (who has since demonstrated his contempt for Parliament) orchestrated an utterly ruthless, scaremongering racist campaign (see ad above) to get Leave its narrow win. His appointment is a clear sign that Johnson is focused on winning an early election, and that he will do whatever it takes to win – including renewed exploitation of racist anti-immigration sentiment.

The Tories’ core political reality

It’s true that Johnson’s attempt to show a liberal face comes as polling shows that the salience of ‘immigration’ in British politics has drastically declined since 2016, while more positive attitudes to immigration have gained support. In his new book, Jonathan Portes argues that developments like the Windrush Scandal have shown that ‘it is possible for politicians to appear too tough on immigration’. It is in this context that some have suggested that a Johnson government’s immigration policy may build on the largely rhetorical movement beyond the ‘hostile environment’ era which has taken place in the last year of the May regime.

Even Farage has let up on immigration. As he went from rally to rally in the European elections, his supporters boasted to me on Twitter that he ‘hadn’t even mentioned’ the subject. Instead, his pitch centred on the ‘betrayal’ of Brexit by the ‘establishment parties’. Even after the election, as the Brexit Party’s ‘new’ star, former Tory minister Anne Widdecombe, made out-and-out reactionary pronouncements about British ‘enslavement’ by the EU and the possibility of ‘gay cure’, she too appears to have steered clear of immigration issues.

However this question is far simpler for the ‘insurgent’ Farage than for Johnson. Not only does he only have to appeal to one side of the Brexit cleavage. He’s also the man who brought immigration to the centre of the European debate, clearly taking aim at Romanians and other East Europeans while claiming that it was all about numbers, not ‘overt racism’. After two decades’ campaigning, this appeal is baked into Farage’s brand. He doesn’t need to mention immigration all the time because his electorate understands that he’s against it.

Johnson, in contrast, will hope to hold on to the Tory voters who didn’t defect to the Brexit Party as well as the majority who did. Yet his core political reality is that not only the Tory membership but also their potential vote has become overwhelmingly pro-Brexit, and Brexiters are overwhelmingly anti-immigration. The Tories are now a Brexit party and they will only win an election by winning the majority of Leavers away from the Brexit Party. The European election result was not an aberration – research has shown that two-thirds of 2016 Leave voters had already voted at least once for UKIP before the referendum.

Johnson’s marker for the racist vote

Therefore while playing both sides, using studied ambiguity as a political method (not just a style), Johnson has also put down a marker for the racist vote. His Islamophobic statements about women who wear burqas were not casual remarks, but written for publication – not long after his meeting with Steve Bannon.

When challenged about these comments in the leadership election, Johnson doubled down, saying that ‘it is vital that we as politicians remember that one of the reasons why the public feels alienated now from us all as a breed is because we are muffling and veiling our language. We don’t speak as we find and cover it up in bureaucratic language when what they want to hear is what we really think.’ This was a signal not just to the Islamophobic Tory selectorate, but also the wider racist vote, that he shares their feelings.

Racism is baked into Brexit

An optimistic view of the prospects on immigration and race must downplay the huge harm that has already been done, before as well as since the referendum. The ‘hostile environment’ was not only Theresa May’s policy; it was first and foremost David Cameron’s response to the rise of UKIP. May’s red line on freedom of movement was not only a reflection of her reactionary instincts; it was her response to the salience of immigration in the Leave vote. Racist aggression has been stirred, and Europeans have been forced to apply for a new status just to stay in the UK.

Not only was ‘immigration’ one of two main reasons for Leave voting; it also gave the only meaningful substance to the other reason, to ‘take back control’ (few voters are excited about independent trade deals). It is difficult to believe that any Tory leader would not have adopted May’s red line. Although a ‘soft’ Brexit made economic sense, it was politically a non-starter because of the toxic anti-immigration campaign that had pushed Leave over the line to a narrow victory.

The decline in the salience of immigration in the polls over the last 3 years needs to be understood in this light. The most probable main reason for the shift is that the British right, Tory, Faragist and tabloid, has been obsessed with Brexit itself, and has had no particular incentive to campaign on immigration. At the same time, Brexit has already caused a drastic reduction in European migration, as our fellow-Europeans have taken stock of British Europhobia and the falling pound and voted with their feet.

A crisis election, a no-holds-barred campaign?

Therefore the ‘Whiteshift’ political scientist Eric Kaufmann is right to say that ‘the ghost of immigration’ has not been exorcised from British politics. This is not because because (as he says) Leavers’ ‘cultural’ objections to immigration remain unaddressed, but because the hiatus in anti-immigration campaigning will come to an end.

Any 2019 poll will be a crisis election such as the UK has not seen for 45 years. Either Johnson will be forced into an election by Parliament’s failure to support him, or he will make a dramatic bid for a majority. Either way, the stakes are huge, with the country already divided in unprecedented and novel ways which are causing huge electorial volatility.

In these circumstances, the incentive for a no-holds-barred campaign will prove irresistible and Cummings’ appointment is a salutary reminder. Moreover Lynton Crosby, who is likely to be a key campaign figure, is well known as the master of the dog whistle, who was responsible for Zac Goldsmith’s campaign against Muslims in the 2016 London Mayoral election and the anti-Scottish scare campaign in the 2015 General Election.

The more overt the Tories are, the greater the likelihood that Farage will up the ante. There has been much speculation about a deal between them, but a widespread electoral pact seems unlikely, since Farage’s ambitions go far beyond serving as handmaiden to a Boris Brexit. A Tory-BP war for the Leave vote could get very crude: as the elite ‘Remainer’ conspiracy is blamed, Europeans, ethnic minorities and gays will feel the heat from frustrated Leavers in society. Amidst the chaos and harm of No Deal, things will be particularly nasty.

After the election – unless Labour and the Remain parties get their acts together and Remain voters manage to vote tactically to block a right-wing majority – the UK could end up with an extreme right-wing parliament as well as government. There will hardly be a liberal climate on immigration and race.

January 8, 2019

Brexit: The Uncivil War – the TV drama disguised the ugly truth

At the beginning of Channel 4’s drama Brexit: The Uncivil War, the ex-Tory Ukip MP Douglas Carswell tells Matthew Elliott and Dominic Cummings, newly appointed to run Vote Leave, that they will offer a “respectable alternative” to the “rightwing thugs” Nigel Farage and Arron Banks. Cummings, the “strategist” (and anti-hero of this semi-biopic), soon returns to the theme: the Conservative-led and soon to be officially recognised campaign “needs to be respectable”, appealing beyond Ukip’s base if it is to win 50% plus one and the referendum. Elliott drums the point home: “We need to get them [Farage and Banks’ Leave.EU] to do the heavy lifting on the migration stuff – then we keep our hands clean.”

However Cummings has a problem. The EU’s supranational institutions, demonised by Brexiters, are “too complicated, too remote” to be the focus of the campaign. It needs a “simple message repeated over and over and over”, if it is to appeal to the “three million extra voters that the other side have no idea exist” who Cummings’ new friend Zack Massingham, of the shadowy AggregateIQ, promises can tip Vote Leave over the line.

What the programme doesn’t tell us is that they are habitual non-voters, the sort of people who have almost zero interest in politics – and are quite likely to include racists. To “appeal to their hearts”, Vote Leave needs a message very like that of the despised Farage and Banks. “£350m and Turkey” shouts Cummings, standing on a table, to his staff. Or to be more accurate, £350m, Turkey and the NHS.

What the film doesn’t tell us is how low he went to push this. It shouldn’t be a secret, since Vote Leave repeated the same election broadcast (now pulled from YouTube) on all terrestrial TV channels throughout the last 30 days of the campaign. Following lurid graphics representing the threat of 76 million Turks joining the EU and coming to the UK, it climaxed with a split screen showing (staying in the EU) a surly foreign man elbowing a tearful elderly white woman out of the queue in A&E, while (leaving the EU) the woman is contentedly treated without having to wait. It was a homage to Enoch Powell, whose 1968 speech highlighted a fearful old white woman living in a street taken over by “negroes”.

Cummings’ 1bn Facebook ads picked up the broadcast’s themes and graphics, but were “micro-targeted”. Less racist voters got pictures of Boris Johnson (“I’m pro-immigration, but above all I’m pro-controlled immigration”), while the “3 million” got ads shouting “5.23 MILLION MORE IMMIGRANTS ARE MOVING TO THE UK! GOOD NEWS???” and when they clicked “No” were bombarded with scores of variations on the theme. It was the same story with leaflets, whistleblower Shahmir Sanni says: “The campaign was always talking about immigration. The most proud moment for many of Vote Leave’s staff was how well the Turkey leaflet did.”

Leave voters didn’t like being accused of racism: “We can’t say nothing now without that coming up,” complains a focus group member in the film. Indeed the point isn’t that anti-immigrant voters were racist, but that Vote Leave assumed they were. The ads laboured how poor Turks were – they didn’t need to say that they were Muslim and foreign, but these were the buttons they aimed to push. The racism was Vote Leave’s, and it was easily turned against the other 3 million, the Europeans in the UK. “Project Hate”, Sadiq Khan called it.

The programme shows Cummings demanding “complete independence”, with Vote Leave’s figureheads Johnson, Michael Gove and Labour’s Gisela Stuart (who chaperoned Johnson on the notorious bus) barely understanding what he was doing. “That is just the actual population of Turkey,” replies Johnson, when a voter throws “70 million Turks” back at him; “I thought we weren’t pushing immigration,” says Gove. Only a game Penny Mordaunt actually tells Andrew Marr: “One million may come here from Turkey in the next year.”

It’s all too convenient. The drama lets Cummings blame Banks and Farage, while he is the fall-guy for Johnson and Gove, who commissioned him to run this shameful campaign. They can’t tell us that neither they nor any of their staff ever watched the election broadcast, picked up any of the leaflets or saw its Facebook ads.

Vote Leave learned from Farage that you couldn’t win Brexit without immigration, and brought racism to the centre of British politics. Now Theresa May is selling her deal the same way.

View on The Guardian

My take on Brexit racism: The Uncivil War TV drama disguised the ugly truth (new article on the Guardian site)

Now available on The Guardian

January 3, 2019

Separating ‘racial self-interest’ from racism doesn’t work

Can we ‘cordon off’ the overtly racist attacks and abuse against Europeans which followed Brexit from the demand from immigration control supported by a majority of Leavers – one of the two main motivations (along with ‘sovereignty’) for people to vote Leave? Eric Kaufmann thinks we can regard immigration-restriction as the ‘racial self-interest’ of the ‘white British’ and cites Max Weber to present this as a ‘rational’ attitude. In my new paper, available now in draft form, I accept that ‘instrumental’ can be regarded as distinct from ‘absolute’ racial attitudes, but argue that they both manifest racism.

If we are to examine immigration attitudes in Brexit, we need to start from how the issue was weaponised, not only by Nigel Farage and Leave.EU, but also by the officially recognised Vote Leave campaign led by Boris Johnson, Michael Gove and then Labour MP Gisela Stuart.

If we are to examine immigration attitudes in Brexit, we need to start from how the issue was weaponised, not only by Nigel Farage and Leave.EU, but also by the officially recognised Vote Leave campaign led by Boris Johnson, Michael Gove and then Labour MP Gisela Stuart.

I argue that Vote Leave engaged in strategic racism; through a discussion of its TV and Facebook propaganda I show how ‘instrumental’ and ‘absolute’ racist tropes were combined, and through a discussion of voters’ attitudes, I argue that it would be difficult to disentangle ‘instrumental’ and ‘absolute’ racial positions. Ironically an ‘instrumental’ racism of a different kind is clearly distinguishable mainly in the choices of Vote Leave’s leaders. (It will be interesting to see how far Channel 4’s drama, Brexit: The Uncivil War, focusing on Vote Leave’s strategist Dominic Cummings, who I refer to a lot, confronts these issues when it airs this week.)

I argue that Weber’s methodology as a whole points us in the direction of seeing racism as a general, structural concept, and I analyse Vote Leave’s strategy and propaganda as an adaptation to structural dilemmas of political racism in Britain since Enoch Powell.

Readers who are interested mainly in Vote Leave may find the shorter summary published on openDemocracy more accessible.

Separating ‘racial self-interest’ from racism doesn’t work, and examining Vote Leave’s strategy and propaganda in the 2016 referendum shows why.

Can we ‘cordon off’ the overtly racist attacks and abuse against Europeans which followed Brexit from the demand from immigration control supported by a majority of Leavers – one of the two main motivations (along with ‘sovereignty’) for people to vote Leave? Eric Kaufmann thinks we can regard immigration-restriction as the ‘racial self-interest’ of the ‘white British’ and cites Max Weber to present this as a ‘rational’ attitude. In my new paper, available now in draft form, I accept that ‘instrumental’ can be regarded as distinct from ‘absolute’ racial attitudes, but argue that they both manifest racism.

If we are to examine immigration attitudes in Brexit, we need to start from how the issue was weaponised, not only by Nigel Farage and Leave.EU, but also by the officially recognised Vote Leave campaign led by Boris Johnson, Michael Gove and then Labour MP Gisela Stuart.

If we are to examine immigration attitudes in Brexit, we need to start from how the issue was weaponised, not only by Nigel Farage and Leave.EU, but also by the officially recognised Vote Leave campaign led by Boris Johnson, Michael Gove and then Labour MP Gisela Stuart.

I argue that Vote Leave engaged in strategic racism; through a discussion of its TV and Facebook propaganda I show how ‘instrumental’ and ‘absolute’ racist tropes were combined, and through a discussion of voters’ attitudes, I argue that it would be difficult to disentangle ‘instrumental’ and ‘absolute’ racial positions. Ironically an ‘instrumental’ racism of a different kind is clearly distinguishable mainly in the choices of Vote Leave’s leaders. (It will be interesting to see how far Channel 4’s drama, Brexit: The Uncivil War, focusing on Vote Leave’s strategist Dominic Cummings, who I refer to a lot, confronts these issues when it airs this week.)

I argue that Weber’s methodology as a whole points us in the direction of seeing racism as a general, structural concept, and I analyse Vote Leave’s strategy and propaganda as an adaptation to structural dilemmas of political racism in Britain since Enoch Powell.

Readers who are interested mainly in Vote Leave may find the shorter summary published on openDemocracy more accessible.

Separating ‘racial self-interest’ from racism doesn’t work, and examining Vote Leave’s strategic racism and propaganda in the 2016 referendum shows why: my new paper now available in draft online

Can we ‘cordon off’ the overtly racist attacks and abuse against Europeans which followed Brexit from the demand from immigration control supported by a majority of Leavers – one of the two main motivations (along with ‘sovereignty’) for people to vote Leave? Eric Kaufmann thinks we can regard immigration-restriction as the ‘racial self-interest’ of the ‘white British’ and cites Max Weber to present this as a ‘rational’ argument. In my new paper, available now in draft form, I accept that ‘instrumental’ can be regarded as distinct from ‘absolute’ racial attitudes, but argue that they both manifest racism.

If we are to examine immigration attitudes in Brexit, we need to start from how the issue was weaponised, not only by Nigel Farage and Leave.EU, but also by the officially recognised Vote Leave campaign led by Boris Johnson, Michael Gove and then Labour MP Gisela Stuart.

If we are to examine immigration attitudes in Brexit, we need to start from how the issue was weaponised, not only by Nigel Farage and Leave.EU, but also by the officially recognised Vote Leave campaign led by Boris Johnson, Michael Gove and then Labour MP Gisela Stuart.

I argue that Vote Leave engaged in strategic racism; through an discussion of its TV and Facebook propaganda I show how ‘instrumental’ and ‘absolute’ racist tropes were combined, and through a discussion of voters’ attitudes, I argue that it would be difficult to disentangle ‘instrumental’ and ‘absolute’ racial positions. Ironically an ‘instrumental’ racism of a different kind is clearly distinguishable mainly in the choices of Vote Leave’s leaders. (It will be interesting to see how far Channel 4’s drama, Brexit: The Uncivil War, focusing on Vote Leave’s strategist Dominic Cummings, who I refer to a lot, confronts these issues when it airs this week.)

I argue that Weber’s methodology as a whole points us in the direction of seeing racism as a general, structural concept, and I analyse Vote Leave’s strategy and propaganda as an adaptation to structural dilemmas of political racism in Britain since Enoch Powell.

Readers who are interested mainly in Vote Leave may find the shorter summary published on openDemocracy more accessible.

that this may have aided a new consolidation of racist structures in British politics and society, which in turn could cause new tensions and require new responses.

As the campaign for a second Brexit referendum hots up, my paper analysing

Martin Shaw's Blog

- Martin Shaw's profile

- 6 followers