Axl Barnes's Blog, page 7

July 22, 2018

On Berdyaev's "Slavery and Freedom"

What should the power relation between man and society be? Should society crush and use the individual for a "common good," like in totalitarian regimes, or should the individual be enabled to rise above all societal pressures?

What should the power relation between man and society be? Should society crush and use the individual for a "common good," like in totalitarian regimes, or should the individual be enabled to rise above all societal pressures? These are the basic questions that Nikolay Berdyaev tackles in his book "Slavery and Freedom." His answer is personalist socialism. His view of personality is central to his account. According to Berdyaev, personality is an existential, spiritual center of freedom and creativity. In this way, he echoes Romanian philosopher Lucian Blaga who stated that humans, as opposed to animals, are beings who live "into mystery and for revelation." Personality is a mystery, a question with no set answer. Human beings are not part of the natural world, they're not objects in the world, but subjects. They exist in the realm of freedom, not in the realm of nature and necessity. As occupant of this realm of freedom, the individual is engaged in a creative dialogue with nature, other individuals and God. God as well is a personality, a subject who can experience joy and suffering alongside his creation. It is as a personality that man was created in the image of God, which means that man is engaged in a perpetual existential dialogue with God. So, on Berdyaev's view, personality is not egotistically closed off to the world, but engaged with other personalities (alive or dead) in a quest for self-discovery and authenticity. On this point, Berdyaev's view resembles narrative views of the self championed by Martin Heidegger and Charles Taylor.

Now, this spiritual quest is something that each personality must take up on his own, it is the individual's freedom and responsibility. However, Berdyaev argues, many people are overwhelmed by this burden of responsibility and decide, consciously or unconsciously, to become objects or slaves, that it, to repress their own humanity and let their personality dissolve in the external world: "Personality is not only capable of experiencing suffering, but in a certain sense personality is suffering. The struggle to achieve personality and its consolidation are a painful process. The self-realization of personality presupposes resistance, it demands a conflict with the enslaving power of the world, a refusal to conform to the world. Refusal of personality, acquiescence in dissolution in the surrounding world can lessen the suffering, and man easily goes that way. Acquiescence in slavery diminishes suffering, refusal increases it. Pain in the human world is the birth of personality, its fight for its own nature." [p. 28] Thus, man is always tempted to surrender his freedom and become a slave. That is the Fall of Man. Possessed by his instinct to obey, man invents a host of false Gods, like the state, the nation, the economy, civilization, technology and so on. But, Berdyaev argues, human personality should always be the supreme value. Nothing should stand above personality.

Now, the question becomes: what social, political and economic system respects the absolute value of personality?

A capitalist system is to be immediately rejected. Capitalism is based on the exploitation of the workers or proletarians. In this system, people are used as things or commodities, not as personalities or free beings. Even the ruling class, the bourgeoisie, is not really free in capitalism. They are also slaves to the system of power that they created. Following Hegel's discussion of the master/slave dialectic, Berdyaev argues that the master himself is a slave to his slave. The master understands himself only in opposition to the slave, and this power relation narrows his consciousness and his freedom.

Turning toward socialism, Berdyaev distinguishes between its metaphysical side and its social and economic side. "The metaphysics of socialism in its prevalent forms are entirely false. They are founded upon the supremacy of society over personality. This is a collectivist metaphysics, it is the lure and temptation of collectivism. Socialists on all hands profess monism and deny the distinction between Caesar's things and God's, between what is natural and social and what is spiritual. Socialist metaphysics regard the common as more real than the individual, class as more real than man; they see the social class behind the man instead of seeing the man behind the social class. Totalitarian, integral socialism is a false outlook upon the world; it denies the spiritual principle, it generalizes man down to the very depth of him.

But the social and economic side of socialism is right and just, it is elementary justice. In this sense socialism is the social projection of Christian personalism. Socialism is not necessarily collectivism, it may be personalistic and anti-collectivist. Only personalist socialism is the liberation of man; collectivist socialism is enslavement." [p. 209]

In personalist socialism the basic necessities of life are covered for all people, but this economic equality does not erase the important differences and inequalities between individuals. There are no classes in personalist socialism, but that doesn't mean that all people are spiritually equal. On the contrary, the socialization of economics should give rise to the individualization of men and women:

Personalist socialism which is founded on the absolute supremacy of personality, of each personality over society, over the state, the supremacy of freedom over equality, offers "bread" to all men while preserving their freedom for them, and without alienating their conscience from them. [p.210]There will always be an arrangement of qualitatively distinct groups in a society, which are connected with professions, vocations, gifts, or a high degree of culture, but there is no element of class in all this. Classes should, in the first place, be replaced by professions. Society cannot be a homogeneous mass devoid of qualitative distinctions. In every society which has arrived at a definite form, there is a tendency towards inequality and it is not permissible to demand a leveling down to the lowest grade. The domination of a rabble might be organized in that way, but that is not a people. But personalism does not allow the class debasement of man. The advancement of man is above all a spiritual advancement; materially, on the other hand, man ought not so much to be raised as to be leveled. [p. 217] Following Marx, Berdyaev argues that in Capitalism, man's natural disposition to work is distorted and labour becomes alienated, being turned into a commodity. In personalist socialism labour would regain the natural place it has in human life.

Daily bread ought to be guaranteed for all men and for every man. There ought not to be any proletariat; there ought not to be people who have been made into a proletariat, who have been dehumanized and depersonalized; labor ought not to be exploited, it ought not to be turned into an article of commerce; and the meaning and dignity of labour ought to be discovered. It is not to be borne that there are people who are outcasts and deprived of any guarantee of existence. It is nothing but a deep-rooted lie which affirms that these elementary problems of human existence are insoluble. There exists no such things as economic laws which require the destitution and unhappiness of the greater part of mankind. These laws are an invention of bourgeois political economy. [p. 218]The emancipation of the workers from the enslaving power of labor, and emancipation which is entirely just and right, raises the problem of the leisure which they do not know how to occupy. The rationalization and technization of economics in the capitalist structure of society create unemployment, which is a most terrible condemnation of that structure. Other forms of social organization, more just and more humane, can give release from too long and too arduous labour, and create leisure, which will be occupied by 'innocent games and amusements.' Can it be said that complete emancipation from the burden of labour and the conversion of human life into unbroken leisure is the goal of social life? That is a wrong way of looking at human life; it is a denial of the seriousness and hardship of human life upon earth. Labour ought to be freed from slavery and oppression, but complete release from labour is not a possibility. Labour is the greatest reality of human life in this world, it is a primary reality. Neither politics, nor yet money is a primary reality, they represent the power of fictions. And the primacy of the reality of labour ought to be an accepted maximum. In labour there is both a truth of redemption ("in the sweat of thy face shalt thou gain thy bread") and a truth of the creative and constructive power of men. Both elements are present in labour. Human labour humanizes nature; it bears witness to the great mission of man in nature. But sin and evil have perverted the mission of labour. A reverse process has taken place in the dehumanization of labour, an alienation of human nature has taken place in the workers. This is an evil and injustice which belongs both to the old slavery and to the new capitalist slavery. Man has been seized with the desire to be not only the master of nature, but also the master of his brother man, and he has enslaved labour. This represents an extreme form of the objectivization of human existence. [...]But if labour ought to be emancipated, it ought not to be deified and turned into an idol. Human life is not only labour, not only working activity, it is also contemplation. Activity is exchanged from time to time for contemplation, and that cannot be driven out of human life. The exclusive power of working activity over human life may enslave man to the flow of time, while contemplation may be a way out from the sway of time into eternity. Contemplation also is creativeness but of another kind than labour. [SAF, p. 220-221] While I agree with Berdyaev's personalist socialism in principle, there's a lot of work to be done regarding how such a social system could be applied in practice. One of these problematic areas concerns the notions of labour, personal freedom and creativity, leisure and contemplation. Berdyaev points out that, "There will always be an arrangement of qualitatively distinct groups in a society, which are connected with professions, vocations, gifts, or a high degree of culture, but there is no element of class in all this. Classes should, in the first place, be replaced by professions." Now, a personality might be related in different ways to his profession, vocation or gift. Let's say someone likes to make shoes, and is thus considered by his group to be a shoemaker. If he becomes tired of making shoes though, it would be oppressive for the community to force him to make shoes anyway, no matter how talented he is. That goes against the spirit of personalism, in which personality is always the highest value and can never be used as a mere means.

The same applies to the notions of vocation or gifts. Berdyaev seems to assume that if someone finds their gift or vocation then they'll automatically decide to do that with their lives. But that's not the case. Someone may be a great pianist but not care much about music, about using that specific gift. In reply, it might be argued that such gifts come from God and man has an obligation to follow God's will. However, that would be in contradiction to Berdyaev's personalism, where God is not a despotic deity but another personality and his supreme gift to man is that of freedom. In addition, there's people who are multi-talented and it would be up to them to decide which talent, if any, they want to cultivate more.

Berdyaev opposes the idea that personalist socialism should do away with labour altogether and replace it with unbroken leisure: "Other forms of social organization, more just and more humane, can give release from too long and too arduous labour, and create leisure, which will be occupied by 'innocent games and amusements.' Can it be said that complete emancipation from the burden of labour and the conversion of human life into unbroken leisure is the goal of social life?" Berdyaev rejects this idea but his argument hinges on a narrow view of leisure. Leisure is actually the basis of culture and civilization. Plato and Aristotle, medieval philosophers, the great artists of the Renaissance period, they didn't have to sell their labour, their creations came mostly from free contemplation and leisure. Bertrand Russell makes this point forcefully: "In the past there was a small leisure class and a large working class. The leisure class enjoyed advantages for which there was no basis in social justice; this necessarily made it oppressive, limited its sympathies, and caused it to invent theories by which to justify its privileges. These facts greatly diminished its excellence, but in spite of this drawback it contributed nearly the whole of what we call civilization. It cultivated the arts and discovered the sciences; it wrote the books, invented the philosophies, and refined social relations. Even the liberation of the oppressed has usually been inaugurated from above. Without the leisure class mankind would never have emerged from barbarism." [Russell, In Praise of Idleness]

Now, there's a number of problems that Berdyaev doesn't address explicitly: what's the relationship between personalism and authentic labour? Is emancipated labour something that is paid for or just results in recognition from other community members? What's the relation between God and authentic labour? And, more generally, do money play a role in personalist socialism? Let's take a concrete example: creative intellectual labour. Being a writer, let's say. A lot of work goes into becoming a good writer. Malcolm Gladwell famously and controversially argued that 10.000 hours go into mastery of a skill, and writing is a complicated skill. That's roughly 3 hours a day for 10 years. But this is time in which you practice writing. Someone like Stephen King indeed writes almost every day for 3 or 4 hours. But, in order to be a good writer, one should also read a lot. And that takes tons of time. Put that in a personalist socialist framework where everyone does what they want and you may get a society of starving artists. So, there should be time that everyone sets aside for the manual labour of providing the necessities of life for everyone. Now, with the technological progress humanity has achieved, as Russell points out, this volunteered time should be minimum. My suggestion is that man can use workdays for leisure and weekends for community, economic work. So, the opposite of what we have now. From my personal experience I know that intellectual labour cannot be sustained for more than five days in a row. The brain needs a break ("All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy") Manual labour can actually provide that break as it stimulates different brain centers and keeps the person physically active. In the long run, I think new discoveries in brain science and the neuroscience of different types of labour will make a big contribution toward deciding how much time one can productively spend in different types of activities. Naturally, such information will not take the form of law but more of a guideline of the amount of mental energy different types of labour involve.

Now, there's a number of problems that Berdyaev doesn't address explicitly: what's the relationship between personalism and authentic labour? Is emancipated labour something that is paid for or just results in recognition from other community members? What's the relation between God and authentic labour? And, more generally, do money play a role in personalist socialism? Let's take a concrete example: creative intellectual labour. Being a writer, let's say. A lot of work goes into becoming a good writer. Malcolm Gladwell famously and controversially argued that 10.000 hours go into mastery of a skill, and writing is a complicated skill. That's roughly 3 hours a day for 10 years. But this is time in which you practice writing. Someone like Stephen King indeed writes almost every day for 3 or 4 hours. But, in order to be a good writer, one should also read a lot. And that takes tons of time. Put that in a personalist socialist framework where everyone does what they want and you may get a society of starving artists. So, there should be time that everyone sets aside for the manual labour of providing the necessities of life for everyone. Now, with the technological progress humanity has achieved, as Russell points out, this volunteered time should be minimum. My suggestion is that man can use workdays for leisure and weekends for community, economic work. So, the opposite of what we have now. From my personal experience I know that intellectual labour cannot be sustained for more than five days in a row. The brain needs a break ("All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy") Manual labour can actually provide that break as it stimulates different brain centers and keeps the person physically active. In the long run, I think new discoveries in brain science and the neuroscience of different types of labour will make a big contribution toward deciding how much time one can productively spend in different types of activities. Naturally, such information will not take the form of law but more of a guideline of the amount of mental energy different types of labour involve. There's also the case in which one chooses freely to do some work that benefits the community greatly; let's say she decides to become a doctor or nurse or work on a new technology that would speed up food production or the building of houses. In that case, I think there will be a collective agreement that that person is exempt from other duties toward the community. They will have the weekend off to focus on family life or just relax. However, no matter how central one's work is to the welfare of the community, the community cannot force the individual to continue doing that work no matter how talented he is. If someone has existential anxiety and needs time off to figure things out about what they want to do with their lives then the others need to give him the peace and quiet necessary for introspection. This is a way of showing respect for their personality and not treating them as a mere means.

All in all, I've found Bedyaev's book very inspirational in the fact that he's able to forge a middle way between egotistic individualism and collectivism. A personality is naturally open to the social and natural world and is engaged in a spiritual conversation with others and with God. Putting yourself first, doesn't mean being selfish, because your self is but a web of narrative spun from your interactions with others, with your social traditions and physical environment. You and others were all created as personalities by God and God is there with you engaged in the same free activity of creative self-knowledge. As personalities, we're all entitled to autonomy and respect as we're all part of the Kingdom of God. Plus, we're all entitled to our daily bread and the basic necessities of life. Personality is the unity of body, soul and spirit. Starvation is an affront to personality. The practical task ahead of us is working out the details of an economic system that centers around the absolute value of personality.

Published on July 22, 2018 14:41

July 15, 2017

Closing Shift (short story)

Isolation Architect by Blemished Projections It's always the last hour that is the longest and time passes slower and slower. No customers, just the wait and aimless wandering. No more thoughts, I'm reduced to being there, a body, defending the merchandize —shoes and menswear —from some unlikely thief. I can't do much in that last hour except fight a losing battle against boredom. Mandip, the woman in menswear, she folds until the last minute, like a machine, as if in some sort of trance, pushing her clothes folding table around like a walker. She's not ugly but suffers from some kind of chronic stomach pain and always looks like she's about to cry, dark circles under her eyes.

Isolation Architect by Blemished Projections It's always the last hour that is the longest and time passes slower and slower. No customers, just the wait and aimless wandering. No more thoughts, I'm reduced to being there, a body, defending the merchandize —shoes and menswear —from some unlikely thief. I can't do much in that last hour except fight a losing battle against boredom. Mandip, the woman in menswear, she folds until the last minute, like a machine, as if in some sort of trance, pushing her clothes folding table around like a walker. She's not ugly but suffers from some kind of chronic stomach pain and always looks like she's about to cry, dark circles under her eyes.Once Thomas, my schooled friend, explained to me Zeno's paradox. How you can't get from point A to point B because you have to cross half the distance first and then half of the remaining distance and then half of that and so on for all fucking eternity. That's how time feels in that last hour. As if every passing moment increases the gaping void ahead. The finish line becomes ever more distant, impossible to reach, like a nightmarish race through quick-sand.

In the background, Cher started singing: "Do you believe in life after love? / I can feel something inside me say / I really don't think you're strong enough?" Is there life after work? I asked myself. Do you believe in life after rape?

I was definitely not felling strong enough. Thomas wasn't able to hang out after my shift, spending too much time with his stupid new girlfriend. I told him he should share her, just for kicks, but he just ignored me. He maybe caught feelings for the cunt. When she's not around, we'd mostly get high and play first-person shooters, sometimes drug my mom's cat just for fun. Of course, I could do all those things by myself but it wouldn't be the same. I considered stopping at Safeway to buy some junkfood but that desire wasn't strong enough either. I was just there, enduring that final hour, with no hope or want to move me, just existing, breathing.

My feet took me to the menswear area, in a half-assed attempt to check some new clothes, although most of them were too tight for me. They had some new cool shorts in the Point Zero brand but they weren't on sale.

Suddenly, I noticed something on the floor, by Mandip's folding table. I thought it was a pile of black clothes some customer left behind, but something pink stood up on top of the pile. As I got closer, I recognized a face, Mandip's sad face; it appeared stretched and almost liquid. I gaped at her in shock. The whole thing seemed like one of those magic tricks where some bearded wizard brandishes a wand and the monster disappears in a puff of smoke leaving its clothes behind. Except, in this case, Mandip only half-disappeared, her flesh was left behind, boneless, melted.

In the background, Cher's song made way to Lady Gaga's Born This Way.

Mandip looked at me with crazed, pitiful eyes. They were widely spread on her flattened face. Her toothless mouth struggled to form words, "Jjjjjack, I don't ffffeel wwwwell..." She spoke with spittle in a way that reminded me of Sylvester the Cat.

Slowly, I took my cell phone out of my pocket and asked, "Should I call an ambulance?"

"No," she spit. "I have to shtay tillup the end of mmmy sshhift...jjjust a bit mmmmooore."

I stared at her in disbelief. "But...you seem to be dying."

"Noooo!! I'm ok, I'm sure I'll get bbbbetter later. I'm jjjust tired, you know? But I need to finish my sshhift for the mmmoney. I don't want my mmmanager to be mmmad at me and cut mmmy hoursh. Is ssshe hhere?"

Catherine, our manager, was also on the closing shift, but she rarely ventured upstairs. I looked around and didn't see her and told this to Mandip.

"Good," she mumbled and just stayed there, waiting, her black, tearful eyes darting around to make sure no one sees her.

"Are you sure you're gonna be ok?" I probed.

"I'll be jjust fine," she said. "After I finish this sssshift and get home and make ssome tea. I'm jjjust exjausted. Worked sixsh days in a rrrrow"

I highly doubted some tea would fix Mandip's problem. I looked down at her with pity and disgust. I really didn't give a shit about her. Not about anybody, except maybe Thomas. Sometimes I go through the motions to show that I give a fuck and am civil but I really don't. If all my coworkers died overnight, I wouldn't give a rat's ass.

Suddenly, with a flabby, trembling hand, Mandip lifted her ID card toward me. "Will you help me sssswipe out ppplease...when ttttime comesh?" Obviously, in her current state it was difficult for her to climb on top of the desk and swipe the card and punch in the required keys.

"Sure," I said. "I'll see you at closing time."

I hurried back to my department. On the plus side, the small incident killed some time. My cell phone said we only had half an hour left. I did a final walk through my footwear department to make sure no shoes were on the floor and no boxes on the display shelves and tables. I did the final clean-up at a snail's pace. Soon, Catherine's voice came from the speakers. "Good evening customers, the store will be closing in fifteen minutes. Please take your final purchases to the nearest cash-desk. The last doors to be left open are on the main floor by the women's apparel department."

Fifteen more minutes, that was three times five minutes. Five minutes sounded more manageable. I pulled out my cell phone and started browsing through pictures and vids of some fresh meat on Toiletwhores. Ashley Sartre was almost as depraved as Tasha Suicide. Soon, the metallic sound of change being counted signalled that the cashiers were closing the tills. I put my phone back and adjusted my boner. I went to the stockroom and grabbed my backpack that still had some lunch leftovers, pop, and expired chocolate that the store idiots wanted to throw away.

At five to nine I headed to the cash registers area to swipe out. Mandip was there, waiting in between baskets full of clothes and other merchandize that customers had returned throughout the day. She looked grateful to see me. There were no more shoppers and the cashiers were focused on counting the money and paid no mind to Mandip and I. I took her ID card and swiped out for her. Like a Jack-in-the-box she stretched her rubbery neck to look up at the screen and make sure everything was ok. The desired message popped up, "Well done! Thank you and have a good day." I returned her card and she put it in her purse. Then she began slithering toward the escalator, like an octopus navigating the bottom of the sea, leaving a slimy track in her wake. I knew she was taking the escalator out of habit, without thinking, and I had a gut feeling I had to stay behind to avoid any responsibility. I swiped out and waited. Mandip oozed down the metal steps. Sure enough, in a few seconds screams pierced the quiet of the store. The cashiers and I ran to the top of the escalator.

As I expected, Mandip was pierced by the metal teeth of the combplate at the bottom of the stairs. Her clothes and amorphous flesh were getting shredded. The two cashiers stared in disbelief, their brains trying to make sense of the gruesome sight. I didn't want to press the emergency stop, why ruin a perfect experience? Mandip's flabby hands slapped on the metal platform but she could gain no purchase as her belly and tits and legs were ripped and chewed by the mechanism. Blood and excrement splashed the steps and the glass of the balustrade as her agonized screams turned to blubbering and then subdued gurgling. Gore and bits of flesh dripped in the pit below the stairs like meat from a grinder.

"Code white, code white!" Catherine screamed over the pager. "John, bring the first aid!" John was the guy from Loss Prevention. I saw Catherine run and press the emergency stop at the bottom of the stairs. Too little, too late for poor Mandip, who was just a ripped, crumpled, stinking bag by now. I doubted a first aid kit would do anything. Maybe just call the cleaning lady.

As the spectacle was over, I made my way to the elevator and went to the lowest floor. On my way I saw John run with his first-aid kit and I bit down a smile. Talk about being useless. Through the employee exit I stepped outside. The long summer day was turning grey. I grabbed my smokes from the backpack and lit one up. The nicotine struck my brain and I had an idea. But it was too late and the regret made my legs feel rubbery. I realized I played the whole thing wrong. I should have gagged Mandip, stuffed her in my backpack and taken her home. Maybe show her to Thomas the day after and see what he thought. Just for kicks.

Published on July 15, 2017 19:42

May 9, 2017

Satanism without Gimmicks

I know many metalheads who consider themselves extreme, yet whenever I approach them I gag from the stench of nine-to-five easy meat. They are easy in more ways than one. It's easy to wear metal shirts and piercings and tattoos, it's easy to play guitar and emulate your favorite band, it's easy to go to metal shows, chug a few beers and wallow in a cheap sense of community. But when you take away the appearances, gimmicks, and conditioned behaviour you're left with the wriggling wormy body of the Satanist's arch-enemy: THE SLAVE!!

I know many metalheads who consider themselves extreme, yet whenever I approach them I gag from the stench of nine-to-five easy meat. They are easy in more ways than one. It's easy to wear metal shirts and piercings and tattoos, it's easy to play guitar and emulate your favorite band, it's easy to go to metal shows, chug a few beers and wallow in a cheap sense of community. But when you take away the appearances, gimmicks, and conditioned behaviour you're left with the wriggling wormy body of the Satanist's arch-enemy: THE SLAVE!! Besides a mixture of amusement and sadness, my encounter with this new embodiment of the archetypal peasant made me reflect of criteria we can use to tell apart the real Satanist from the multicolored scum. By definition, the Satanist is a rebel, an outsider, a master of his own destiny. He's full of his own will and, depending on his mood, either anti-social or asocial. A lone wolf, he regards others as either inconveniences or useful tools, and befriends only a chosen few. By contrast, the Slave is eager to follow and obey the will of others, he can't bear solitude or any sort of personal responsibility, he's most at home in crowds, and dreams of shaking off his humanity and one day turning into a sex doll.

So, if we are to identify the real Satanists in a society at a given time we first have to ask: What are the most oppressive forces operating in this society? We live in an age of unfettered capitalism and wage slavery. The oppression characteristic of such a system is very dangerous and insidious as it doesn't come from a well-defined center of power, as in more classical totalitarian systems, but it's spread out in a network of tunnels and economic traps hidden by the attractive facade of free market ideology. In this context, language heavy with political import and other means of thought control are also tremendous and sophisticated instruments of coercion. In addition, things like one's family or friends or "tribe" have always been known to try to manipulate the individual by imposing requirements like carrying on the family name, participating in meaningless family events or defending various social traditions or customs the individual has no genuine interest in.

In a capitalist society, the Satanist should be either grudgingly employed or unemployed and living on welfare. Anyone who willfully sells themselves for a full-time job is NOT A SATANIST, but A LIFE-DENYING SLAVE! The Adversary might work full-time when running out of options but he never does it happily or willfully and he knows he'll have to take his revenge for every second of such humiliation. The Satanist sells his labor while plotting his revenge. He controls his alienation with savage thoughts of bloody payback. Part-time and casual employment or living on welfare are always more seductive for a rebellious spirit. Rather than looking for him in an office building, there's a better chance of finding the authentic Opposer at the public library reading The Communist Manifesto, or down the river valley having sex, writing poetry or exchanging survival tips with the tented homeless.

The real Satanist doesn't care about family or tribe or nation or any sort of community he contingently finds himself in. He only cares about himself, his will, his life. If you see a happy family man, behold, that is A WRETCHED SLAVE!! For a Satanist having kids is the equivalent of suicide, or even worse, a long-drawn sordid self-torture. The Satanist has a few like-minded friends but is always vigilant about the terms of those friendships. If a friend succumbs to the siren call of slavery he's immediately rejected before he starts spewing his nonsense and poisoning the elite group. The Aristocrat only socializes on his own terms and never wastes his time on worthless, boring people, unless he indulges his cruel desire to mock them and introduce them to their own weakness.

Ash from Nargaroth and a kindred spirit. The genuine Master is usually quiet and doesn't enjoy running his mouth and engaging in endless small-talk. Language is a trap, a form of thought control, a great force that constantly saps the powers of the individual. That's why the Satanist strives to be creative in his language use, and tries to resist and dismantle the disciplinary power implicit in the value-laden vocabulary uncritically used by his troglodyte contemporaries. False idols like God, Money, Nation, Love, are but amusing targets for the Rebel's steaming jet of urine. Like a true artist, The Satanist delights in the game of creation and destruction, destruction and creation. Art is the highest expression of freedom, and a good artist is always an original. Originality is a satanic ideal by definition because it involves the highest degree of self-knowledge. The artist is a creator of worlds rather than part of a world created by someone else.

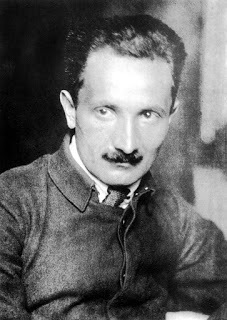

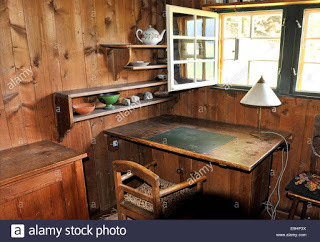

Ash from Nargaroth and a kindred spirit. The genuine Master is usually quiet and doesn't enjoy running his mouth and engaging in endless small-talk. Language is a trap, a form of thought control, a great force that constantly saps the powers of the individual. That's why the Satanist strives to be creative in his language use, and tries to resist and dismantle the disciplinary power implicit in the value-laden vocabulary uncritically used by his troglodyte contemporaries. False idols like God, Money, Nation, Love, are but amusing targets for the Rebel's steaming jet of urine. Like a true artist, The Satanist delights in the game of creation and destruction, destruction and creation. Art is the highest expression of freedom, and a good artist is always an original. Originality is a satanic ideal by definition because it involves the highest degree of self-knowledge. The artist is a creator of worlds rather than part of a world created by someone else. Philosopher Martin Heidegger

Philosopher Martin Heidegger The desk at which Martin Heidegger wrote is masterpiece Being and Time, a work that revolutionized western thought and invented a new language to describe the human experience. Martin Heidegger is a poetic hero by definition.

The desk at which Martin Heidegger wrote is masterpiece Being and Time, a work that revolutionized western thought and invented a new language to describe the human experience. Martin Heidegger is a poetic hero by definition. As you can see, being a Satanist isn't easy. It's not for everyone. It's a life of almost unbearable lucidity, constant struggle with others as well as the shadows of others in one's self, a life of endless, neurotic vigilance. Yet it is also a life of euphoric delight in one's creative powers, in one's strength to overcome one's self, learn and develop, and in one's capacity to find kindred spirits and imagine new ways of being free. So, if you're ready to go to a metal show, take a good look in the mirror at the symbols you're wearing and decide for yourself if you're worthy of them. What anti-social deed have you done lately? In what interesting ways are you different from the mindless scum that makes up society? Did you create anything of value in your life? Are you a hero or just a follower? If that introspection isn't going well, there's always the option of transcending yourself with a bullet or a knife.

Published on May 09, 2017 15:22

August 27, 2016

"Odin Rising" — chapter two, Alex's Open Eye

Alex opened his bedroom window, lit up a cigarette, and rested his elbows on the window sill.

Tonight was Studio Rock night. The radio show would start in an hour, at ten.

He looked forward to listening to metal and learning about new releases while getting hammered. The fact that they had no math tomorrow made things even sweeter.

No Mr. Stan!No Mr. Fucking Stan!

Alex's apartment was on the main level and he could closely follow the activity on his block. The view wasn't perfect, because of the trees in the building's yard and the chain-link fence around them. But Alex could see the Galaxyshop across the street, and its proud owner, Mr. Tache.

Mr. Tache was chatting with two guys out front, while Magda busied herself with the till inside. Short, fat, and bold, Mr. Tache wore his sunglasses. He was a poker player and, running a business, he never tired of saying, was a lot like playing poker. Sunglasses helped him bluff. His tight red Nike t-shirt barely covered the navel of his bulging belly. Left hand deep in the pocket of his tight blue jeans, Mr. Tache used his right hand to gesticulate broadly as he spoke.

Now, Alex noticed, the businessman was pointing toward his new car, a dark blue Audi parked on Alex's side of the street, right in front of the chain-link fence. The car keys hung from Tache's index finger. The West European car was something to brag about in a country were many people still drove horse-drawn carts or Russian Volgas and Ladas.

One of Tache's interlocutors, a young gypsy, crossed the street and peered inside the car. "The boss is right, it's all automatic," he shouted back over his shoulder. Tache nodded, beaming with smug pride. The gypsy crossed back and resumed listening to Tache's expostulations.

Alex hated Mr. Tache. He wanted him dead.

He remembered how the man had been a nobody before the revolution. Alex used to play with Tache's son, Florin, and had been to their apartment a few times. Alex had noticed that Florin's parents were even poorer than his own. Didn't even have a color TV or record player.

After the revolution, Tache jumped on the entrepreneurial bandwagon and opened Galaxy to sell blue jeans, Coca-Cola and the latest must-have American imports. The corrugated iron shack was a big hit. Under the influence of shows like Dallas, Romanians thought that under capitalism they had to wear blue jeans like the American ranchers. After lining up for hours customers had to use the bushes behind the shack as a fitting room.

That's how Tache became a somebody overnight. At first, he and his wife were the only staff. When business picked up he hired Magda, a fresh high school graduate, and an older woman with retail experience. A few months later, Tache divorced his wife and shacked up with Magda in the new apartment he bought. All the men on the block looked at him with deep respect mixed with bitter envy.

Now he was showing off his brand new car.

Alex exhaled cigarette smoke through pursed lips and spat on the ground. He turkey fucked a new cigarette into life, smashed the filter of the old one on the window sill and tossed it outside.

He forced his mind away from the infuriating Mr. Tache.

Instead, his thoughts turned to his obsession: Romania's destiny. Alex found inspiration in Romania's past: Decebal, Vlad Ţepeş, Ştefan the Great, Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, a.k.a. "The Captain," Marshal Ion Antonescu, whose surname Alex proudly bore.

"Alex Antonescu." A name meant for the history books.

But, Alex thought, after the Second World War Romania had deteriorated. The fascist leaders of the 20s and 30s, Zelea Codreanu and Horia Sima, had envisioned joining Hitler in the war against the Bolshevik plague. But then, during the invasion of Russia, things went terribly wrong, especially in the battles of Moscow and Stalingrad.

Every time Alex thought about the Führer's defeat he felt like crying.

After the war Romania was trapped in the Soviet nightmare of humiliation and degradation that culminated in the dictatorship of Nicolae Ceauşescu, the butcher of his nation's soul.

In 1989 Romanians took to the streets, defying Ceauşescu's regime. Many were massacred, a blood sacrifice for freedom. In the end, revolutionaries seized and killed the dictator and his horrible wife.

And what did they get in return?Alex asked himself bitterly.

They had deposed the socialist Jew only to meet his capitalist twin, the merchant Jew. Romania opened for business in the world market and the American capitalist worm wriggled inside her.

That's how Tache had become a hero.

Trying to swallow a lump in his throat, Alex remembered the words of his idiotic history teacher, Mr. Ion: "In capitalism, everything is for sale."

Alex cringed. The teacher should have been dismissed for spewing such traitorous nonsense.

Alex firmly believed that both communism and capitalism must be eradicated and Europe had to be returned to its rightful leaders: the Aryan race. Other races, whether Slavs, Gypsies, or Blacks, were to become slaves. Either that or be exterminated.

In the youth's view, Germany and the Northern Countries were waking from centuries of slumber and Romania had to join the Aryans or be destroyed in their brutal war of revenge. Alex thought of himself as the representative of the Aryans in Eastern Europe. His life’s mission was to raise the racial consciousness of Romanians, to remind them of the main commandment from the God of nations: protect the survival of the Aryan race by enslaving or decimating the inferior races, the physically and morally ugly, the mentally ill, the handicapped, the mercantile Jews.

Unlike his classmates, Alex had clear plans for his future. He wanted to get into the Theoretical High School and to qualify for the National History Olympiad and, in senior year, the International Philosophy Olympiad. He also needed to master English and German. Then he would go to the University of Bucharest to study political science and form a radical right-wing political party. He wasn't sure of the name yet but "Land and Blood" tripped nicely from his tongue. Once his fascist party gained power, it would purge the nation's tired body of all foreign parasites and effect Romania's transfiguration.

Besides being a prodigy, Alex had no doubt he was a natural born leader, like his idol, Adolf Hitler. People obeyed him instinctively. Even his parents submitted to his will. They knew he was already a smoker and a drinker but never protested. The teachers loved and respected him. His classmates strove to please him. He had always felt that he radiated a magnetic energy, just like the golden halo around the heads of saints. This meant only one thing: he was one of the chosen.

Like the Führer, Alex had a talent for oratory, a skill he wanted to cultivate during his political career. Once, when Mr. Ion had begun lecturing on Nazi Germany's war in the East, Alex, tired of the teacher's mistakes and omissions, jumped from his desk, snatched the pointer from the teacher's hands and went to the map at the head of the class. Humiliated, the young teacher sat at his desk and listened to his student. Alex lectured for a whole hour, making his classmates see and feel the battles. They listened transfixed. During that hour Alex was all powerful. He felt he had hypnotized the class and they would do whatever he wanted. Kill, rape, torture. With brutal savagery.

Alex knew his best friends, Tudor and Edi, were just followers. Tudor would assume leadership from time to time, but was uncomfortable doing so. He was born to follow. Alex knew of Tudor's raw power, having witnessed him destroy Cornel. But that power needed to be channeled by a true leader. A natural ruler, Alex thought, needed to choose his acolytes carefully. If they proved faithful and competent, they were to be promoted and encouraged. If otherwise, brutally punished or mercilessly rejected. Maybe in ten years or so, Alex reflected, if they displayed enough strength and spirit of sacrifice, Tudor and Edi would lead two nests of "Land and Blood."

Land and Blood, Alex murmured to himself, staring at the green yard outside his bedroom window. The Blood was essential. It was about the Aryan blood pumping through Alex's veins. He was blond, with blue eyes and an elongated skull. He was already 5'7, as tall as Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer of the SS. On his mom's side, his roots were in Brașov, a German settlement in Transylvania.

In Romanian lit. they had learned about Mihail Sadoveanu, who claimed to hear the voices of his ancestors, unknown heroes and warriors, whispering their stories to him. Alex felt the same way. His Germanic ancestors were alive in his blood.

The language of blood transcended space and time. Alex had received the call in sixth grade. The caller was none other than Vlad Ţepeş, a.k.a. Dracula. It happened during summer camp at Sinaia, deep in the Carpathian Mountains. The teachers had organized a day trip to Târgoviște, the medieval capital of Wallachia, the southern part of Romania. Tudor and Edi didn't want to go, being more interested in the soccer tournament at the camp. At Târgoviște, they visited the Chindia Tower, the only fortification remaining from Ţepeş' castle. Alex and the group climbed the spiral staircase to the second floor and looked through a narrow window at the courtyard below. While the guide explained that the courtyard had been Ţepeş’ execution grounds, Alex's head exploded.

He was rocked by a flash of light deep within his brain. Alex looked out the window again and saw the courtyard filled with impaled victims. Some dead and decayed, some still twitching like pinned frogs. He felt trapped in someone else's body, unable to control his movements.

The eyes of his host scanned his surroundings and settled on two monks. The elder of the bearded, brown-robed monks was speaking, his bushy eyebrows furrowed in anger. Alex didn't understand the words, but it sounded like Latin. Abruptly, the monk stopped talking and his eyes rolled back in his head. Blood gushed out of his mouth, spattering his beard and chest. As his white eyes bulged in terror, the sharp tip of a bloodied stake emerged from his mouth. Alex's host shook with bombastic laughter. His visual field reddened, becoming a window deluged with a rain of blood. The laughter stopped, and a deep voice intoned a warning:

The day of judgment shall come,My rule in blood!!

That "blood" resounded with anger and thirst, causing Alex to envision the dark prince's full, red lips under a thick moustache. He remembered how, when dining among the impaled, Vlad Ţepeş would chase his food with his victim's blood instead of wine.

When Alex returned to his ordinary senses, he lay on the floor, surrounded by the worried faces of the guide and the other students.

In the following months, Alex thought long and hard about his experience and read voraciously about psychic and mystic visions. It all made sense when he found Mircea Eliade's description of initiation rites in archaic societies. Around puberty, novices were sent by themselves into the wilderness, where some, the chosen ones, were contacted by the spirits of their ancestors. The spirits imparted wisdom and sacred knowledge. The more powerful novices experienced more profound visions, which sometimes shook their minds to the brink of insanity.

Since the sixth grade, Alex had regularly seen visions, usually of scenes from the history books he devoured. But school and the desolate town didn't provide an environment for spiritual growth. He ached to escape into the wilds of the Carpathians, to find the deep roots of the Romanian nation. Now, he planned to visit his aunt in Brașovin the summer and to venture alone into the mountains for a week or so. He still needed to work out the details and find a way to hide his absence. But his mind was settled. He'd bring only bread, water, and hard liquor. He knew first-hand that alcohol facilitated entering ecstatic states by undermining the authority of the conscious mind and giving free reign to the unconscious, where the memory of the sacred lay hidden. He'd sleep in the woods, with no tent or other shelter, purifying his body and mind of the toxins of "civilization." As Eliade explained, the novice must become dead to the world. As a clean spirit craving enlightenment, Alex hoped to receive wisdom and guidance from ancient Romanian warriors and shamans, noble spirits disgusted by the degeneration of their race.

Now, with a few minutes remaining before Studio Rock, Alex thirsted for a strong drink. He opened his bedroom door and listened. The hallway was dark and quiet. His parents must have gone to bed. The teen stepped through the darkness toward the kitchen. He flicked on the light, opened the fridge, and grabbed tomato juice and a lemon. From the cupboards he produced an empty glass and a small pepper shaker. He placed the lemon into the empty glass.

Alex turned off the kitchen light and returned to his bedroom with the four items. He placed the ingredients on his desk and retrieved a bottle of vodka from under the bed. He filled half the glass with the liquor. Then, with a hunting knife he produced from the drawer of his desk, he cut the lemon in half and squeezed its juice into the vodka. After adding tomato juice and pepper, he took a sip.

Pleased, he drank deeply.

The liquor sent chills through his body. He released a satisfied sigh.

The Bloody Mary was his favorite drink; vodka for those who didn't want to get smashed right away.

Alex unwrapped a blank cassette, removed it from its plastic case, and inserted it into his boombox. He turned on the radio and selected the right frequency, 98.3 FM. Static ceded the airwaves to Leni's deep voice greeting the listeners. Alex pressed the Play and Rec buttons and the cassette started recording.A

Alex sipped his Bloody Mary, reclined in his chair, and lit up a cigarette.

When Leni began talking about Rammstein, the German industrial metal band, Alex turned the volume to the maximum and ensured the player was recording.

The mention of his favorite band felt like and electricity jolt and the teen jumped from his chair and began pacing up and down the room.

"Their shows are literally incendiary," Leni said. "The frontman, Till Lindemann, performs while on fire!!"

Petre Malin, the co-host, added, "I bet our listeners are eager to hear about Rammstein's new album."Damn straight, Alex mumbled, his heart racing.

Papers rustled in the background. Then, Leni's voice: "Yes, indeed, Sehnsucht, their second studio album, was released last week and has already reached number 1 in Germany. It is selling better than their first release, Herzeleid, which itself was a stunning success."

"Here's the title track from the album," Malin announced. "Afterward we'll let you know how to order Sehnsucht through Heavy Metal Magazine."

Alex obsessively checked whether the tape was rolling and then struck his chest and thrust his hand outward, palm down. Heil Hitler!

The song started with a simple, eerie, melancholic keyboard melody. Then the musical panzer division exploded into a rhythmic frenzy. Alex banged his head wildly up and down, his blond hair lashing his face. His mind filled with black and white images of marching German soldiers accompanied by motorized divisions and Stukas that dominated the sky. Lindemann's deep, hypnotic voice blended into the martial music. His obsessive refrain — "Sehn-sucht/Sehn-sucht" —was at once victorious and heartbreaking. After the chorus and the reprise of the wailing keyboard bit, the drums and guitar boomed back to life. Alex jumped onto the bed and launched himself into a flying knee. He hammered his thighs with his fists while banging his head.

When the song ended there were beads of sweat on his forehead. Dizzied by the intensity of his musical rapture, he stumbled to his desk, sat, and emptied his glass. He pushed the bangs from his eyes and, with trembling hands, meticulously prepared another Bloody Mary. More vodka this time.

Ordering Sehnsucht was now Alex's first priority. Then listening to it all day, learning the lyrics by heart, and singing along.

Buzzing from alcohol and anticipation, he took a deep drink and sat back in his chair.

Leni announced how Sehnsucht could be ordered by writing to HMM. The host also advertised new Rammstein merchandise for hardcore fans, as well as tickets for their show in Budapest. Unfortunately, the band wasn't scheduled to come to Romania. But dedicated fans could travel to Hungary for the opportunity to see their idols live. Now, after the fall of communism, Leni reminded his audience, no visa was required.

Alex considered going to Budapest for the show. He looked at the large map of Europe hanging on the wall above his desk, and followed the path from Bucharest to Budapest. It led through the Carpathians. It would be a nice trip to make with Tudor and Edi, and they could stop at his aunt's place in Brașov, meet some of his metalhead friends, and head for Budapest as a group. This was a golden opportunity to make friends with other neo-Nazis, although, as a Romanian nationalist, Alex hated Hungarians, a most inferior people. However, the youth realized bitterly, the concert was in late August, during the high school entrance exams. He couldn't miss those for anything.

Preparing another Bloody Mary, Alex thought he'd have plenty of opportunities to see Rammstein live. Maybe he could write them, beg them to come to Bucharest. Write to them in German.

Petre Malin interrupted Alex's reverie with his top ten of black and death metal songs. The section featured brutal songs from Cannibal Corpse, Morbid Angel, Carcass, as well as the Swedish band Grave, whose song "Soulless" caught Alex's attention. Gorgoroth and Emperor represented Satanic Norwegian black metal.

In the middle of the Emperor song, Alex got up to flip the cassette and made a mental note to order their new album.

As he grew more intoxicated, Alex found it increasingly difficult to keep track of all the bands and new album titles. Thankfully, he would be able to revisit the recording in the following days, when more lucid.

By the time the show ended at midnight, Alex was halfway through his vodka and seeing double. His blurred hand found the cassette with the Rammstein song and inserted it into the player.

He thumbed the Play button.

The quality of the recording was good.

He rewound the tape to the beginning of the song and pushed Play again. Now, the eerie keyboard melody impressed him more. The wailing expressed the pain of a nation. The cry of Germany, its Aryan spirit suffocated by Slavic waves of filth. The bass guitar pulsated evenly, like the heartbeat beneath the ruins of Berlin, the vital rhythm of the Nordic Man’s battered soul.

The song slowly tightened its grip on Alex’s mind, sending vibrations through every cell in his body. His fingers rewound the tape and pushed Playautomatically.

Until they stopped.

Alex's body froze, like a robot that ran out of power. The song was imprinted in his brain, a code that would unlock the door to his unconscious. Alex opened the mental gate and staggered under the force of an icy gale. Clenching his teeth, he willed himself into the frozen landscape.

A blinding light exploded in his head.

His physical eyes rolled back. His mind's eye opened.

He was flying.

He was in an aircraft, piloting over snow-covered territory. Lucid and free from his physical body's intoxication, Alex looked through his host's eyes. The wind was blowing snow to powder, obscuring the land below. But during gaps in the blizzard, Alex could distinguish charred fragments of ruined houses, with only chimneys left standing. Here and there he spotted rusty skeletons of tanks, like carcasses of prehistoric giants.

He was in an aircraft, piloting over snow-covered territory. Lucid and free from his physical body's intoxication, Alex looked through his host's eyes. The wind was blowing snow to powder, obscuring the land below. But during gaps in the blizzard, Alex could distinguish charred fragments of ruined houses, with only chimneys left standing. Here and there he spotted rusty skeletons of tanks, like carcasses of prehistoric giants.Alex lifted his gaze to the horizon. Between columns of black smoke he recognized a structure: the massive Grain Elevator. The rectangular concrete building commanded the Stalingrad skyline. It stood like a decayed tooth, windows and walls smashed by artillery and Stukaattacks.

"I'm at Stalingrad!," he shouted in his mind.

But his enthusiasm was clouded by the sense of doom surrounding the place, its dark, heavy, suffocating ambiance. It was as if the tortured souls of the thousands of dead people coagulated into a plasma that covered the ruined city and devoured everything around it. Even the plane was unable to ascend over the clouds seemingly trapped by the black aura of the industrial wasteland.

Fighting the gloom, Alex realized with excitement that German soldiers were on the ground below, hiding in trenches and dugouts.

"Germans, down!" he thought, trying to manipulate the hidden mechanism of his vision.

He willed himself down.

He hurtled through a tunnel of light and alit in a dugout. Despite the log-lined walls and fire crackling in the stove, the room was frozen. In flickering yellow lamplight from, Alex discerned half a dozen bodies. The men were inert, and Alex was unsure whether they were alive, dying, or already dead. With scarves wrapped around their heads and their large dirty coats over their tunics, they resembled a group of old hags. Only the Nazi eagle emblem on some hats and helmets identified them as German soldiers.

Alex knew he must be inside the mind of a Nazi soldier but his hosts' brain was devoid of thought. The young guest fought off sudden panic when he imagined getting trapped inside a soldier’s dead body. But then his host moved his head and looked down at the comrade leaning against his legs. He shook him by the shoulder, sending the soldier's head lolling up and down. Alex's host rose and inspected his comrade. Alex saw a face disfigured by frostbite: black, lacerated nose and cheeks under sunken, vacant eyes; bloody, swollen lips twisted in a rigid grimace. A mass of lice crawled from the head of the unresponsive man onto the hand and wrist of Alex's host. The soldier shook his hand free of the parasites. At last Alex recorded a spark of brain activity: an image of winter boots. Alex's suddenly enlivened host dropped his comrade and pulled off the dead man’s boots. He slowly stripped off the rags wrapping his feet. Alex looked through his host’s eyes at a foot ravaged by winter. Only one crooked and black toe remained. The big one. The other piggies stayed home in the filthy rags. Or were eaten by mice. The foot reeked of rot.

The soldier’s anguished scream catapulted Alex out of his mind.

Alex landed in a conference room. His new host was discussing strategy over a map spread on a large table. Hands moved in big sweeps over the chart dotted with swastika flags. The man looked up. A few Nazi generals came into view. Alex immediately recognized Friedrich Paulus, commander of the Sixth Army, and Franz Halder, Chief of the German Army General Staff.

Alex couldn't contain his excitement.

He had landed the big one. He was inside the Führer.

Afraid his joy might tear the thin fabric of his vision, Alex focused on the historical meeting unfolding before him. Paulus was explaining something, pointing at Stalingrad. Halder intervened and indicated the Caucasus. Alex felt the Führer's anger as he looked at the map and the city bearing the name of Stalin, his arch enemy. Suddenly, ripples formed on the surface of the map, as though it had turned liquid. When he looked more carefully, Alex saw undulating snakes, their skin changing its pattern to reflect the chart below. The reptiles slithered rapidly from the Urals into eastern Russia and Poland, leaving bloody trails.

When he realized the snakes were moving toward Germany, Hitler panicked. His vision blurred and shook, stuttering like the image on a broken TV. The hands that moments before had swept grandly over the map now clenched into fists and smashed the camouflaged snakes. Blood jetted from the strikes and splattered on the paper. Red drops splashed the Führer's eyes, and he shut them reflexively. Trapped in the dark, Alex felt paralyzing venom pervade his host's body. Afraid he'd be trapped buried alive in Hitler's mind, Alex panicked and screamed.

He woke at his desk, drenched in sweat. For a few moments his eyes rested on the map of Europe above the desk. He visualized the progress of the Red Army: Kiev, Bucharest, Budapest, Vienna, Berlin.

How could this happen?

Alex broke down in tears and covered his face with his hands.

He wept convulsively, trying to catch his breath between sobs. "Fucking slaves! They were nothing! Less than nothing! The slaves of slaves! How could they beat the Führer?" he demanded through a curtain of tears and spittle.

After a while the sobs diminished. Alex lit a cigarette, rose from the chair and sat on the edge of his bed. Dark thoughts filled his mind, the echoes of his nightmarish visions. He imagined Hitler spending the last months of the war in the Führerbunker, a shadow of his former self. He had a hump, Parkinson’s disease, an ineradicable tremor in his left hand. His eyes were dull, and his skin had a greyish, mortuary complexion. He was nothing but a beaten dog in hiding. A scared and humiliated old dog. When he ventured outside the bunker, he looked like a ghost haunting the ruined city.

Alex clenched his teeth and his eyes teared up again when the next bitter thought came.

He knew the war was lost but couldn't understand why.

A cyanide pill and a bullet in the head wouldn't help him understanding. The old dog would die consumed by the fear that Stalin would find his body and hang it upside down in disgrace, like they did with Mussolini.

Alex started weeping again and the room blurred with his tears. "Berlin must burn!" he declared stridently. Then he took a long drag of his cigarette, clenched his left hand into a fist, and pressed the fiery tip into the pale skin of his forearm. Pain hit his numb brain and he smelled burnt flesh.

"Burn, Berlin, burn!" he said through cigarette smoke. "You're not fit for life!"

In an agonized haze, Alex managed to crush the cigarette butt in an ashtray. Then he passed out on the bed, the darkness behind his closed eyes still lighted by flames.

A booming thunder woke him an hour later. He looked around with bloodshot, crusty eyes. He realized he had left the bedroom window open, and now rain water wetted the curtains and the window sill. As he got out of bed, a jolt of pain from his left arm made him grimace. He closed the window, turned off the lights, and looked out into the rainy night. The neon yellow Galaxy sign warped and glimmered, refracted by the torrent. Lightning illuminated the grey apartment building across the street like artillery fire. The street was dark and deserted. The whole neighborhood slept.

Hopefully it will swell the river and flood this fucking town.

He remembered the flood from the mid '80s, when he was just a kid. The waters had drowned the gypsy slums in the valley and the authorities had to build tall dykes on both sides of the Amara. But on a night like this the angry waters might break the dyke and wash away the scum again.

A rainy night like this, Alex thought, was perfect cover for a surprise attack. The lightning outside coincided with a flash in Alex's mind. The war wasn't over. He was a German soldier deep in enemy territory. Although Hitler was dead, he, Alex, was very much alive. And this wasn't Hitler's war; it wasn’t the Great War or the Cold War. No, nothing like that! This was the primordial war between the majestic blond race and the inferior, resentful apes.

It was a spiritual war in the name of the cultural progress of humanity waged by its most evolved biological creation: the Aryan Man.

Emboldened by the rightness of his sacred operation, Alex formulated his strategy in a split second. Possessed by a sense of invincibility, he disregarded all tactical obstacles.

He left his bedroom, walked to the front door, and slipped on his black high-top hiking shoes. From the hallway he could hear his parents snoring in loud, regular unison. Back in his room, he opened his closet and grabbed a black hoodie and a black balaclava his parents had bought him when they'd gone skiing in Brașov. He also put on his pair of black gloves, so he wouldn't leave any fingerprints. Together with his black sweatpants, the new ensemble would make him almost invisible against the dark night.

Then the teen grabbed his hunting knife, sheathed it, and put it in the large pocket of his hoodie. He opened the window and breathed a deep draft of fresh, humid air. The wet pavement glistened in the pale light of streetlamps. The paws of stray dogs on the asphalt punctuated the rain’s drumbeat. Probably on their way to the dumpster, he thought. Another lightning strike split the horizon but the delayed crack of thunder showed that the storm was slowly moving away.

Alex jumped through the window into the small yard. The ground was muddy, so he shifted his weight onto his toes to avoid leaving footprints. He reached the short chain-link fence and scanned his surroundings. No one in sight. Mr. Tache's Audi was just beyond the fence, a glittering token of the triumph of the Slaves.

Alex wondered whether the car had an alarm system.

He squatted and fumbled for a stone. He lobbed the small rock over the fence, onto the car’s hood. It ricocheted unceremoniously onto the pavement.

No alarm.

Relieved, Alex jumped the fence and crouched by the passenger door. His heart hammered in his chest, and his back was drenched by intermingled sweat and rain. After a few seconds he brandished his knife and impaledt the the front tire. Air escaped the tire like the last exhalation of a euthanized beast, its usefulness exhausted after years under the yoke. The car slowly leaned forward. He repeated the procedure with the rear tire and then sidled to the other side. He was now visible to the street and the adjacent apartment building. Crouching in the lamplight, he impaled the two tires in quick succession and withdrew to the dark space between car and fence.

Still no sound but the drumming of the rain. No footsteps, no movement.

Alex was soaked but ecstatic. He decided to add artistry to violence. He reversed his knife and engraved a swastika onto the hood of the car. The blade easily penetrated the dark paint. The emblem shone clearly in the Galaxy’s neon light.

He sheathed his knife and put it in his pocket.

Overjoyed, he jumped back into the yard and crouched down behind a tree trunk. Still no sound or movement, as if the constant raining lulled everyone into deep sleep.

Alex looked at the Galaxy and the logos crowding its large front windows: Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Levi's, Adidas. The shelves were bursting with merchandise: on one side clothing, on the other food and drinks.

Suddenly, Alex felt the small shop was the pinnacle of perversity, the embodiment of everything he hated.

How he wished for a hand grenade! But, for now at least, smashing those windows was enough. Alex fumbled through the mud looking for a rock. He rejected one as too small for his task. Then he unearthed a stone the size of a brick and wiped away the mud adhering to its surface. Stretching his neck, he calculated the distance to the shop's window. Hefting the stone, he computed the force and trajectory of the throw. He scanned the missile’s flight path for obstacles. Then, tensing all his muscles, he fired the stone high into the air. His breath caught in his lungs. A cacophony shattered the night as the Galaxy's window disintegrated into tiny shards that traced glinting arcs along their route to the shop floor. A moment of silence followed the commotion. Alex stood motionless behind the tree trunk. Although his heart pounded in his chest, he was smiling.

Shortly afterward, someone opened a window and shouted. "Who's there? I'll call the police!" the voice demanded from the building across the street. Alex saw windows light up and shadows move behind curtains. The crowns of the trees hid him from the residents of his building. He crept slowly toward his window. He grabbed the sill and dragged himself up. After he jumped back inside he carefully closed the window.

Mission accomplished!

Quietly, he stowed his gear in the closet, lay down in his bed, and folded his hands on his chest, a huge grin splitting his face.

I did it! I fucking did it!! Mr. Tache will shit his pants!

Shortly afterward, Alex heard police sirens and people talking outside. Dim red and blue lights played on the rain-splashed window and on the ceiling.

Soon, Alex fell asleep, his lips curled into a smile.

There were no more nightmares.

Published on August 27, 2016 09:00

June 20, 2016

Natasha Suicide (Funeral Portraits Part 2)

Natasha Suicide has lived up to her name. Or died up to her name to be exact; the anti-human, anti-life Russian beauty. I've meet her on an online forum where she was avidly commenting about Depressive Suicidal Black Metal. Her beauty was stunning — elegant face, straight blonde hair, large green eyes — but there was something alien hidden in those expressive eyes, like she was there but not really, like she could turn into the chick from The Exorcist at the flip of a switch.

Natasha Suicide has lived up to her name. Or died up to her name to be exact; the anti-human, anti-life Russian beauty. I've meet her on an online forum where she was avidly commenting about Depressive Suicidal Black Metal. Her beauty was stunning — elegant face, straight blonde hair, large green eyes — but there was something alien hidden in those expressive eyes, like she was there but not really, like she could turn into the chick from The Exorcist at the flip of a switch. When we'd chat from time to time she always threatened suicide and I knew she wasn't a poser, like the slut from Fight Club, feigning suicide just to get Brad Pitt's fat juicy cock. Natasha was the real deal. I mean, Russians are fucked!! Ever heard of Chernobyl? She lived in a town just like that, some fucking Stalinist monotone industrial nightmare, Elektrovorsk or some shit. You don't need a nuclear disaster to want to die if you live there. Hell, you're basically born dead. Speaking of Russians, have you seen the hoards of sick fucks, dressed in rags like zombies, who went to see Metallica and Pantera when they first played there after the fall of the Iron Curtain? More than one million rockers came to the show in Moscow. Were those musicians on that stage or Gods descended from a leaden sky? Poverty breeds a special kind of metalhead, a true kind, a dangerous kind. But, back to Natasha, I live in Canada and there wasn't much I could do to help her. And why bother anyway? Why help someone when you can sit back, study their self-destruction in slow motion, and wait for inspiration to strike.

When she abruptly deleted her Facebook profile I knew her time has come. She was gone from the online world and probably from the physical world as well. I only found out the gory details later on from the list of internet comments her suicide had spawned. Yuliana, one of the nurses, was more than happy to spill the beans in exchange of some social media attention. Natasha's suicide was probably big news in the small industrial town and fate had placed Yuliana in the thick of the action. At first I thought the nurse might exaggerate a bit for dramatic effect but everything she said fit perfectly with my idea of Natasha's macabre style.

Natasha had jumped from the tenth floor of her apartment building. Alas, she didn't die right away. Within minutes, they managed to pile her skinny, broken body in an ambulance, and rush her to the ER. She had a gas mask on her face, nobody knew why. One of the paramedics removed the mask and handed it to Yuliana as they reached the hospital. Even though agitated and shocked, Yuliana swears there were strange black patterns on the eyes of the mask, like satanic, occult symbols drawn with a marker. Then the paramedic nodded toward Natasha, unable to speak. When she looked at the mangled body on the stretcher the nurse gasped; Natasha's head was all covered in duct tape, like a weird mummy, tufts of blond hair sticking out here and there, blood seeping through the gaps. Her black "Life is Pain" t-shirt and cut off jeans were soiled with blood and barely held together a slim body that was but a bag of bones. Her tiny bare feet were twisted at weird angles from her shinbones and knees. She looked like a doll that suffered the vicious tantrum of some insane child in the middle of playing doctor.

No amount of practice could ready Yuliana for this sight. The norms of her training flashed in her mind like some weird abstractions.

Breathing.

First and foremost, they needed to make sure the patient was able to breathe. Then they'd try to stop the massive bleeding and probably get a blood transfusion. But if the patient's mouth and nose were sealed by duct tape Natasha could asphyxiate and choke on her own blood. With trembling hands that seemed miles away Yuliana grabbed some scissors and started cutting through the grey mask. Soon, a gargling sound came from deep inside Natasha's throat. That meant she was still alive. Yuliana cut faster, all the way to the temple by Natasha's left eye. Blood stuck to the tape and scissors like jelly. When the nurse unglued the cover from her mouth and nose and her left eye, Natasha's jaw fell down on her neck like an unhinged plate. A black thing coated in blood slid out of her mouth. It was her iPhone. The gore didn't penetrate its slick case. It seemed like Natasha had pulled out her teeth and sliced the tendons of her jaw prior to the jump in order to better fit the device in her mouth. The black earphones still protruded from its jack and black strings went to Natasha's ears.

She's still listening to music, Yuliana realized as a cold shiver went through her. Mechanically, she removed one of the ear plugs. As if the nurse pressed the wrong button on a twisted robotic doll, Natasha began convulsing and screaming, spit and blood flying from her exposed tongue. Except what came out of Natasha's throat, Yuliana insisted on clarifying, was not so much a scream but sounded more like the squeals of a stuck pig. Natasha's left eye, the one not covered by duct tape, also opened and stared at Yuliana, bulging with hatred. That green eye now tinged with pure red rage. The nurse said that she was suddenly, irrationally afraid for her life. As if that mangled, ruined body would somehow manage to pull itself together, get up, and chew on the fringes of her sanity. Rip at it with that horribly dislodged jaw. Frantically, Yuliana placed the earplug back in Natasha's ear and the dying girl instantly stopped convulsing. The green eye squeezed shut and Yuliana swore she saw tears roll out of it. But that might just be her bullshit. Then the dying girl's body was rocked by puking fits as a black, reeking substance gushed from her ruined throat, drowning the already soiled phone. And then Natasha went still, a hideous doll, nurses in white uniforms gaping at her, a faint vibration of sad music still spilling from her phone into her skull and the sudden silence of the ER.

Autopsy revealed that Natasha had also ingested a lethal amount of pesticide prior to her jump, Yuliana was happy to share. Natasha just wanted to be on the safe side, I thought, and do a thorough job. Suicide is tricky business. Hitler ate a bullet, popped a cyanide pill, and had ordered his body burned. Natasha was far worse than Hitler, trust me on this, although you won't find her name in stupid history books. She hated all life and the pest of humanity. She knew her enemy well, she strategized. She knew the deceitful hideous thing would cling to her with its slimy limbs like a rejected and obsessive lover, and she needed to battle it with all her strength. Fight it till the end, fight it in style.

Published on June 20, 2016 16:12

June 1, 2016

Emil Cioran and Depressive Suicidal Black Metal (Part 1)

There are many interesting connections between the work of nihilist philosopher Emil Cioran and the art of Depressive Suicidal Black Metal (for short DSBM). This should come as no surprise since Cioran authored such books as On the Heights of Despair, The Trouble with Being Born, and A Short History of Decay. Throughout his life, Cioran had suffered from insomnia and the pest of lucidity and deep awareness in a cold and meaningless universe. Trapped in a painful dilemma, Cioran hated living just as much as he did dying. While he praised suicide, he always lamented it coming too late, like all actions rooted in a mind on the brink of madness. Despising a moribund God, Cioran only craved the dark forgetfulness of the complete void, which he received when he was blessed with dementia in his old age.

In this post I just highlight a deep, organic connection between Cioran's early remarks on despair and the grotesque and the dark imagery of DSBM. Cioran wrote On the Heights of Despair at the age of 20, and already considered himself an expert in the problem of death. This fragment is from his early book.

Despair and the Grotesque