Andrew Cartmel's Blog, page 41

June 16, 2013

Comments, Replies and Corrections...

First of all I want to thank all the readers of this blog who have taken the trouble to not only read my postings, but also to provide feedback.

First of all I want to thank all the readers of this blog who have taken the trouble to not only read my postings, but also to provide feedback.If you look at the bottom of each post you'll see there's a little area which allows comments and responses. Many of you make use of this facility and I've often been impressed with the insights and information you've provided. I always read these with interest, appreciation and gratitude. What I haven't been able to do it reply to them.

Because, although there is a great big button marked 'Reply', all this would do is allow me to write a long and considered response — my feedback on your feedback — and then when I pushed the button it would disappear. Into the void. Forever.

After doing this half a dozen times, you can understand why I despaired and gave up replying. Of course, I tried to figure out what was going wrong. This being Blogger, though, the help and guidance provided is pretty much non-existent. So I asked more technically savvy friends. They too were baffled.

And naturally I trawled the internet for clues. Which is where, last week, I finally found the answer. I won't bore you with the details but it involved adjusting the third party cookies on my browser. Whatever they are. (The pictures from The Nutty Professor at the beginning of this post will give you some idea of my own estimate of my abilities in this technical area.)

So now I can reply to comments, and I'll endeavour to do so in a timely fashion. But just so I don't feel all alone with my screw-ups I thought I'd talk briefly about other people's. In particular, blunders by publishers.

So now I can reply to comments, and I'll endeavour to do so in a timely fashion. But just so I don't feel all alone with my screw-ups I thought I'd talk briefly about other people's. In particular, blunders by publishers.Following on last week's discussion on The Great Gatsby I re-read Fitzgerald's novel, the better to compare it to the film (which I must say is holding up rather well). I read the handsome vintage Penguin Modern Classics copy I had on my bookshelf.

Unfortunately, it contains a risible printing mistake.

There's a scene where the narrator Nick Carraway is drunk at a party in an upstairs apartment in New York City. He looks out the window and describes "the casual watcher in the darkening streets". In my Penguin edition (Chapter 2, page 42) it goes on to say "and I saw him too, looking up and wondering."

Well, anyone who has read another edition of the book or seen the film, with Toby Maguire standing down in the street and looking up at himself in the window, will know the passage should actually read "and I was him too, looking up and wondering". (Italics in both quotes are mine.)

Well, anyone who has read another edition of the book or seen the film, with Toby Maguire standing down in the street and looking up at himself in the window, will know the passage should actually read "and I was him too, looking up and wondering". (Italics in both quotes are mine.)Quite a difference.

Although perhaps not as much as a blunder as in the first Penguin edition of Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita, which contains an afterword by the author, which concludes with the words "which the native illusionist, frac-tails flying, can magically use..."

(Frac-tails, as you may have guessed, are those long old fashioned black tailcoats.)

Well the Penguin edition rendered this as "frac-tails frying" (my italics). Which is not the same thing at all.

Well the Penguin edition rendered this as "frac-tails frying" (my italics). Which is not the same thing at all.(Advice to publishers: try not to get a misprint in the last sentence of a book. Even the first sentence isn't as bad as that.)

That's all for now folks. And if you spot any typos in this post, you can leave a comment. And I can reply. The picture from The Nutty Professor at the end of this post will indicate that I'm a lot happier about my abilities in this area now. Jerry's happy because he's got Stella. I'm happy because I've triumphed over my cookies.

(The image of Jerry Lewis from the Nutty Professor holding the test tube full of green stuff is from Broadway dot Com. The Penguin Gatsby with the Kees Van Dongen cover painting is from good old GoodReads. The Penguin Lolita is from Giraffe Days. The Nutty Professor image with the pink background is, by a very odd coincidence, from a site called Lolita's Classics. The other Nutty Professor image featuring Jerry and Stella Stevens is from Cinésthesia. The photo of Josephine Baker looking decidedly fetching in her frac-tail coat is from Stage Wear. By the way, don't try and look up 'frac-tails' online, because the moronic search engines will insist that you mean 'fractals'.)

(The image of Jerry Lewis from the Nutty Professor holding the test tube full of green stuff is from Broadway dot Com. The Penguin Gatsby with the Kees Van Dongen cover painting is from good old GoodReads. The Penguin Lolita is from Giraffe Days. The Nutty Professor image with the pink background is, by a very odd coincidence, from a site called Lolita's Classics. The other Nutty Professor image featuring Jerry and Stella Stevens is from Cinésthesia. The photo of Josephine Baker looking decidedly fetching in her frac-tail coat is from Stage Wear. By the way, don't try and look up 'frac-tails' online, because the moronic search engines will insist that you mean 'fractals'.)

Published on June 16, 2013 01:25

June 9, 2013

The Great Gatsy: Fitzgerald meets Luhrmann

F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby now sells more copies every month than it did in the author's entire troubled lifetime. Deservedly so, since the book is a small masterpiece.

F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby now sells more copies every month than it did in the author's entire troubled lifetime. Deservedly so, since the book is a small masterpiece.I say 'small' masterpiece not to denigrate it but because it's a short novel, a novella actually — around 50,000 words, or half the length of your average novel today.

It is also lean in its prose. Saving the occasional purple lurch, Fitzgerald writes sparsely and economically, with precision and elegance. Elegance in the sense of an elegant mathematical equation, which achieves its goal directly and minimally, without extra detail or unnecessary effort.

Balance this against the director responsible for the latest screen adaptation — Baz Luhrmann (Romeo + Juliet, Moulin Rouge).

Luhrmann, whatever his virtues — and I've often enjoyed his films — is a film maker who likes to pour on the syrup, and then add a layer of custard and cream. And possibly several scoops of tutti-frutti ice cream.

Luhrmann, whatever his virtues — and I've often enjoyed his films — is a film maker who likes to pour on the syrup, and then add a layer of custard and cream. And possibly several scoops of tutti-frutti ice cream.So, not surprisingly, the early section of the film is a classic example of Luhrmann extravagance. But despite this it turns out to be an admirable adaptation of the book. Partly because Fitzgerald's original is strong enough to be impervious to camp excess.

But also, in fairness, because Luhrmann and his longtime screenwriting partner Craig Pearce have taken great pains to be faithful to the novel. (Besides his movies with Luhrmann, Craig Pearce also worked on the superior screenplay for The Death and Life of Charlie St Cloud, from Ben Sherwood's novel).

The result is a startlingly effective Gatsby, despite its flaws. Perhaps this isn't surprising since Romeo + Juliet was also a refreshingly smart adaptation of a classic text.

Both these films share the crucial virtues of a sharp script and superb casting.

Leonardo DiCaprio is perfect as Gatsby, Fitzgerald's "elegant young roughneck." I can't imagine a better performance. He understands the character completely, and inhabits him with total conviction.

Daisy, the object of Gatsby's doomed love, is played by Carey Mulligan. I wasn't sure of her in the early part of the film, but as soon as she is put together on screen with DiCaprio the effect is electric. When Daisy looks at Gatsby, emotion just wells up in her and the whole movie comes to life.

The early part of the film is probably its biggest problem. Luhrmann and Pearce have devised a framing story in which Nick Carraway (Tobey Maguire) , the narrator, is in a nut house. He relates the film to a shrink who encourages him to turn it into a book. And thus he writes the story of Gatsby.

It's easy to see the attraction of this device, but frankly its creaky and just encumbers the movie.

There's also the problem that Gatsby doesn't turn up on screen for a long time. Again, the appeal of doing this is easy to understand. It really builds the character up and makes for a big impact when he does arrive.

But it also means that the early section of the movie just flounders. It's a vacuum which Luhrmann fills by doing his big production number schtick, which some might unkindly describe as Ken Russell without the genius. It's unsatisfactory stuff and despite Luhrmann's generally great use of music, Bryan Ferry's wonderful retro-jazz version of 'Love is the Drug' gets thrown away.

There are also some annoying anachronisms in the film. Did people really indulge in air-kissing in the 1920s? They certainly didn't call anyone a "scumbag", not for about another 50 years. (They did, however, talk about tabloid journalism, which surprised me — I'm glad I checked before I castigated the screenwriters on this.)

There are also some annoying anachronisms in the film. Did people really indulge in air-kissing in the 1920s? They certainly didn't call anyone a "scumbag", not for about another 50 years. (They did, however, talk about tabloid journalism, which surprised me — I'm glad I checked before I castigated the screenwriters on this.)Enough nitpicking, as soon as Gatsby turns up, we're off to the races. And the film does a marvellous job of depicting his tormented love affair with the married Daisy.

Despite its imperfections, it's hard to imagine a more faithful or effective adaptation of the Fitzgerald novel.

Ultimately Baz Luhrmann's The Great Gatsby is a beautiful painting — perhaps even a masterpiece — in a distractingly ornate and over-decorated frame.

(The book cover is from Wikipedia. Daisy poster detail is from Indie Wire. The whole poster is from First Showing, as is the DiCaprio poster. The 'profile' posters of Mulligan and DiCaprio and the Maguire poster are from Bad Ass Digest. The still of Gatsby and Daisy together is from Contact Music. Gatsby with champagne glass and fireworks is from The Boar.)

Published on June 09, 2013 01:22

June 2, 2013

John Huston & W.R. Burnett: High Sierra

W.R. Burnett, now shamefully forgotten, is one of the greatest American crime writers. (He also wrote some notable Westerns, which makes him the Elmore Leonard of his day.)

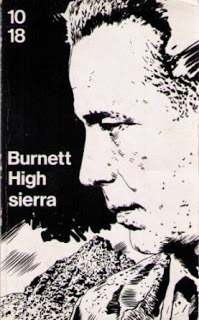

W.R. Burnett, now shamefully forgotten, is one of the greatest American crime writers. (He also wrote some notable Westerns, which makes him the Elmore Leonard of his day.)High Sierra may well be Burnett's masterpiece, it's certainly one of my favourite crime novels, and it deserves a blog post all of its own. However, to do it full justice I'm going to have to re-read it. So that's for another time.

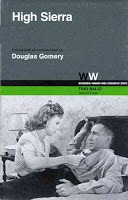

Today we're talking about the screenplay of High Sierra, which was made available by the nice people at the University of Wisconsin Press in their Warner Bros. Screenplay series and which has been my reading-on-trains-and-buses book lately.

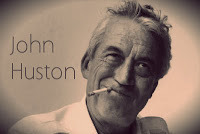

Today we're talking about the screenplay of High Sierra, which was made available by the nice people at the University of Wisconsin Press in their Warner Bros. Screenplay series and which has been my reading-on-trains-and-buses book lately.I recently posted about John Huston's film of The List of Adrian Messenger. Huston is one of our finest film directors. He was also a top screenwriter. And he wrote the script of High Sierra based on W.R. Burnett's novel. (Burnett also gets credit on the title page of the script, which suggests he did early drafts before Huston was brought in.)

The U. of W. book is a lovely item. It features an introduction, footnotes and photographs. And, crucially, it contains scenes which were cut from the final version of the film. It's also a real screenplay, containing the dialogue and scene directions as Huston (and Burnett) wrote them — not like some published "screenplays" which are nothing more than transcriptions from a DVD of the movie, taken down by some poor hack (Faber & Faber, I'm looking at you here).

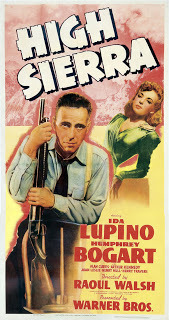

The U. of W. book is a lovely item. It features an introduction, footnotes and photographs. And, crucially, it contains scenes which were cut from the final version of the film. It's also a real screenplay, containing the dialogue and scene directions as Huston (and Burnett) wrote them — not like some published "screenplays" which are nothing more than transcriptions from a DVD of the movie, taken down by some poor hack (Faber & Faber, I'm looking at you here).High Sierra tells the story of Roy Earle (played in the film by Humphrey Bogart, a tough and experienced bank robber serving life who is sprung from the penitentiary (pardoned thanks to a bribe) to take place in a jewel heist at a resort in the eponymous mountain range.

When Roy arrives in the clean air of the wild peaks he soon finds himself acquiring a loyal and loving girlfriend (Marie, played by the admirable Ida Lupino) and an equally loyal and adoring dog (Pard). Both Marie and Pard are strays. And Roy has been a loner all his life. Now he becomes part of a family virtually overnight.

The reader's heart goes out to him...

Unfortunately, he still has that robbery to pull.

And his cohorts are not as strong and reliable as his new mistress ("The girl's the best man of the lot," says Roy) — or even the dog. Sadly, Marie and Pard aren't part of the jewel-raid team, otherwise things might have turned out differently.

High Sierra is a heist-gone-wrong story, but it is also much more than that. Mostly, to me, it's a tragedy about Roy Earle, an admirable man trapped by circumstance.

One of its strongest sub plots concerns a family of hicks whom Roy rescues and befriends. The grand daughter, Velma, is a pretty young woman with a club foot. Roy pays for the surgery to have it repaired. He is smitten with the girl.

One of its strongest sub plots concerns a family of hicks whom Roy rescues and befriends. The grand daughter, Velma, is a pretty young woman with a club foot. Roy pays for the surgery to have it repaired. He is smitten with the girl.This is where the script and the novel diverge. In the book Roy visits Velma, recovering in bed after her successful surgery, and clumsily proposes to her.

She turns him down, because she is loyal to her 'boyfriend' back home. There is a strong suggestion that this guy just shagged and her and ditched her, and Velma's feelings are misplaced. Anyway, she makes the classic suggestion to Roy that they can still "be friends" (some dialogue just never dates).

She turns him down, because she is loyal to her 'boyfriend' back home. There is a strong suggestion that this guy just shagged and her and ditched her, and Velma's feelings are misplaced. Anyway, she makes the classic suggestion to Roy that they can still "be friends" (some dialogue just never dates).In the screenplay, something similar happens. But the crucial difference is that the post-op Velma, liberated from her club foot, is revealed to be an empty headed little jitterbugging slut, partying with a bunch of moronic lowlifes.

In both versions Roy is rejected, but in the John Huston script his kindness and generosity is shown to be utterly wasted by the revelation of Velma's true nature. This sort of twisted cynicism is highly characteristic of Huston — and I must say, I like it. I think it's probably even stronger than W.R. Burnett's original.

In both versions Roy is rejected, but in the John Huston script his kindness and generosity is shown to be utterly wasted by the revelation of Velma's true nature. This sort of twisted cynicism is highly characteristic of Huston — and I must say, I like it. I think it's probably even stronger than W.R. Burnett's original. In any case, I recommend both Burnett's novel and Huston's script in the highest possible terms. The actual movie I can't vouch for. I haven't seen it for years. But it was directed by Raoul Walsh — Huston 'only' wrote the screenplay — and I am not a huge fan of Walsh. He certainly isn't in Huston's league as a film maker. And I suspect the movie has dated somewhat, despite Bogart's iconic presence.

In any case, I recommend both Burnett's novel and Huston's script in the highest possible terms. The actual movie I can't vouch for. I haven't seen it for years. But it was directed by Raoul Walsh — Huston 'only' wrote the screenplay — and I am not a huge fan of Walsh. He certainly isn't in Huston's league as a film maker. And I suspect the movie has dated somewhat, despite Bogart's iconic presence.But I'll have to get the DVD and check it out.

Like Donald Westlake's Parker, Roy Earle is a totally professional armed robber. Like Parker he is only vulnerable when let down by treacherous, amateurish or incompetent associates. Unfortunately, unlike Parker, he didn't go on to enjoy some two dozen capers.

Like Donald Westlake's Parker, Roy Earle is a totally professional armed robber. Like Parker he is only vulnerable when let down by treacherous, amateurish or incompetent associates. Unfortunately, unlike Parker, he didn't go on to enjoy some two dozen capers. More's the pity.

(Picture credits: The really striking 10 18 French paperback with its graphic Bogart profile cover is from Amazon. I like this so much I'm tempted to buy a copy even though I don't speak French — yet. The cover of the screenplay is from the Strand Bookstore and you can buy a copy there. The orange movie poster ("He must be killed!" — which expresses the Hays Code morality of movies of the day) is from Docs on Film. The narrow pink and yellow film poster is from a useful site called Noir of the Week. The attractive variant on this poster is from Cinema Gumbo which is replete with great images. The VHS cover (I think that's what it is) is from Detnovel. The image of the slightly dodgy DVD cover is from Daily Kos. The nice shot of Roy, Pard and Marie is from Aurora's Gin Joint, a classic film blog. The photo of Bogart with his rifle crouching in the mountains is from Classic Film 101. I couldn't find a decent image of this photo on the internet, but I loved it so much I included this pixelated one. The great still of Bogart in a chair with a shotgun is from the Night Editor. Bogart with the two .45s is from Flixster.)

(Picture credits: The really striking 10 18 French paperback with its graphic Bogart profile cover is from Amazon. I like this so much I'm tempted to buy a copy even though I don't speak French — yet. The cover of the screenplay is from the Strand Bookstore and you can buy a copy there. The orange movie poster ("He must be killed!" — which expresses the Hays Code morality of movies of the day) is from Docs on Film. The narrow pink and yellow film poster is from a useful site called Noir of the Week. The attractive variant on this poster is from Cinema Gumbo which is replete with great images. The VHS cover (I think that's what it is) is from Detnovel. The image of the slightly dodgy DVD cover is from Daily Kos. The nice shot of Roy, Pard and Marie is from Aurora's Gin Joint, a classic film blog. The photo of Bogart with his rifle crouching in the mountains is from Classic Film 101. I couldn't find a decent image of this photo on the internet, but I loved it so much I included this pixelated one. The great still of Bogart in a chair with a shotgun is from the Night Editor. Bogart with the two .45s is from Flixster.)

Published on June 02, 2013 01:43

May 26, 2013

Philip MacDonald: Gethryn on Film

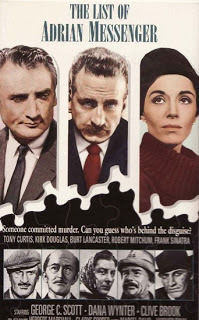

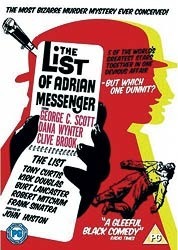

A couple of weeks ago I wrote about The List of Adrian Messenger. This was the last of Philip MacDonald's 12 novels featuring his intelligence officer turned amateur detective Anthony Gethryn (great name).

A couple of weeks ago I wrote about The List of Adrian Messenger. This was the last of Philip MacDonald's 12 novels featuring his intelligence officer turned amateur detective Anthony Gethryn (great name).Now thanks to my favourite DVD shop, Fopp (when in London, shop at Fopp) I have a copy of John Huston's film of The List of Adrian Messenger which I watched as soon as I got it home.

I'm a big admirer of Huston and I'd actually once seen this movie, or some of it, on television, over 20 years ago. I had vague memories of foxhunting and latex masks — which, as it turns out, are not too inaccurate.

The first thing to be said about the film is that it seriously understates Philip MacDonald's contribution. His authorship of the novel isn't even mentioned. Instead he gets on-screen credit in small letters for providing the 'story' of the film.

The first thing to be said about the film is that it seriously understates Philip MacDonald's contribution. His authorship of the novel isn't even mentioned. Instead he gets on-screen credit in small letters for providing the 'story' of the film.Now, in the language of screenwriting attribution a story credit usually means the writer either wrote a brief treatment on which the film was based, or did the first draft of the script which was subsequently massively altered.

Meanwhile in large letters the screenplay is credited to Anthony Veiller. Veiller was a veteran screenwriter who had often collaborated with John Huston, notably on Night of the Iguana, The Killers and Beat the Devil.

Meanwhile in large letters the screenplay is credited to Anthony Veiller. Veiller was a veteran screenwriter who had often collaborated with John Huston, notably on Night of the Iguana, The Killers and Beat the Devil.As a result of his work on the Messenger script, Anthony Veiller was nominated by the Mystery Writers of American for their Edgar Alan Poe award in 1964.

Veiller (and presumably Huston, who was himself a first rate screenwriter) certainly did an excellent job of adapting MacDonald's novel. The book has been ingeniously compressed and conflated and some very effective new material has been invented, notably at the end.

Veiller (and presumably Huston, who was himself a first rate screenwriter) certainly did an excellent job of adapting MacDonald's novel. The book has been ingeniously compressed and conflated and some very effective new material has been invented, notably at the end.However, Philip MacDonald's contribution has been unfairly glossed over by the minuscule story credit. The plot of his book has been faithfully followed (up until the end) with many of the incidents carefully retained, the characters and their relationships are present and correct — even the love story, featuring the delectable Dana Wynters as Lady Jocelyn, has been transferred intact, and is handled charmingly and amusingly — perhaps even more so than it was in MacDonald's original.

And much of MacDonald's (excellent) dialogue has been lifted straight from the novel for the movie.

In any case, it's great to see Gethryn (well played by George C. Scott) come to life on screen complete with his regular police stooges — sorry, collaborators — Lucas and Pike.

The acting throughout the movie is mostly of an agreeably high standard, with perhaps the exception of Tony Huston, the director's young son who has been cast out of his depth and seems uncomfortable in the role of an English heir to a large fortune — which provides the movie's McGuffin.

The acting throughout the movie is mostly of an agreeably high standard, with perhaps the exception of Tony Huston, the director's young son who has been cast out of his depth and seems uncomfortable in the role of an English heir to a large fortune — which provides the movie's McGuffin.This is an engrossing, intelligent, well made film, shot in black and white with Ted Scaife contributing to the photography and a music score by the great Jerry Goldsmith.

As I mentioned, the ending of the movie differs considerably from the book. I didn't mind this, partly because the conclusion of the novel wasn't entirely satisfactory, involving as it did a sudden shift in location (from England to America) and the introduction of a new group of characters to assist the good guys.

In the film the climax is kept in England, and indeed is set in the estates of the family who are central to the plot, which makes a lot of sense. And by allowing the psychopathic killer to actually enter into the home of the aristocratic family it makes for a more satisfactory game of cat and mouse.

However, there is a minor flaw but annoying flaw here. When the killer turns up to join the foxhunting aristocrats, Gethryn knows exactly who he is. So why doesn't he just arrest him? Well, because he doesn't have any evidence. The entire case against the killer (played by Kirk Douglas) is circumstantial.

But someone needed to point this out in dialogue.

But there is a much bigger problem with the film. In the novel the killer makes use of disguise to change his identity. In the movie they decided to really go to town on this, with the result that Kirk Douglas staggers around under layers of latex, wearing some of the most egregious and phony make up I've ever seen in my life.

But there is a much bigger problem with the film. In the novel the killer makes use of disguise to change his identity. In the movie they decided to really go to town on this, with the result that Kirk Douglas staggers around under layers of latex, wearing some of the most egregious and phony make up I've ever seen in my life. Unbelievably, the film makers seemed to have thought these prosthetic disguises were so impressive that they'd make them a major part of the movie's marketing. And so there are risible cameos by big stars (Tony Curtis, Robert Mitchum, Frank Sinatra, Burt Lancaster) in tiny roles, also buried under these ludicrous, lumpy-faced joke-shop masks. I wish they hadn't bothered.

Unbelievably, the film makers seemed to have thought these prosthetic disguises were so impressive that they'd make them a major part of the movie's marketing. And so there are risible cameos by big stars (Tony Curtis, Robert Mitchum, Frank Sinatra, Burt Lancaster) in tiny roles, also buried under these ludicrous, lumpy-faced joke-shop masks. I wish they hadn't bothered.What makes this exercise even more pointless is the fact that some of the supposed cameos weren't even played by the stars in question, but rather a disguised actor called Jan Merlin.

But none of this prevents The List of Adrian Messenger being a superior thriller and a worthy adaptation of the novel.

But none of this prevents The List of Adrian Messenger being a superior thriller and a worthy adaptation of the novel.There were five films of Gethryn novels, but I suspect this is by far the best of them.

The DVD doesn't feature any extras, but it a nice crisp transfer and is available for a bargain price.

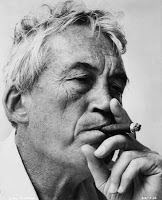

(Image credits: the nice poster at the top is from Torrent Butler, a site with a fantastic collection of John Huston film posters which is well worth a visit. Indeed, Huston seems to have attracted a lot of excellent internet activity. The photo of George C. Scott as Gethryn and the other bloke — John Merrivale as Adrian Messenger himself — with his back to us and the shot of Kirk Douglas removing his disguise are from an impressive blog called Every John Huston Movie. Check it out. The photo of Huston with his son Tony on location is from A Certain Cinema. The still of Gethryn at the chalkboard is from Talkin' Oldies. The British knife-in-the-back DVD cover is from the distributor Metrodome. No one actually gets knifed in the movie though — our careful psychopath's whole schtick is to make the killings look accidental.The brightly coloured alternative DVD cover is from Film List. The foxhunt still with Gethryn in the foreground and, if you look carefully, John Huston in a cameo on horseback in the background, is from Mounds and Circles. Dana Wynter as Lady Jocelyn holding a cat — no pussy jokes, please — is from 148 Bonnie Meadow Road, a laudable blog about cats in the movies. The French movie poster is from Film Affinity, as is the second French poster. The image of Huston smoking one of the cigars that killed him is from Good Fellas Movie Blog. The image of Huston smoking one of the cigarettes that killed him is from MUBI. The final smoking picture is of Huston as Noah Cross in Chinatown and is from Wikipedia, where it is mislabeled.)

(Image credits: the nice poster at the top is from Torrent Butler, a site with a fantastic collection of John Huston film posters which is well worth a visit. Indeed, Huston seems to have attracted a lot of excellent internet activity. The photo of George C. Scott as Gethryn and the other bloke — John Merrivale as Adrian Messenger himself — with his back to us and the shot of Kirk Douglas removing his disguise are from an impressive blog called Every John Huston Movie. Check it out. The photo of Huston with his son Tony on location is from A Certain Cinema. The still of Gethryn at the chalkboard is from Talkin' Oldies. The British knife-in-the-back DVD cover is from the distributor Metrodome. No one actually gets knifed in the movie though — our careful psychopath's whole schtick is to make the killings look accidental.The brightly coloured alternative DVD cover is from Film List. The foxhunt still with Gethryn in the foreground and, if you look carefully, John Huston in a cameo on horseback in the background, is from Mounds and Circles. Dana Wynter as Lady Jocelyn holding a cat — no pussy jokes, please — is from 148 Bonnie Meadow Road, a laudable blog about cats in the movies. The French movie poster is from Film Affinity, as is the second French poster. The image of Huston smoking one of the cigars that killed him is from Good Fellas Movie Blog. The image of Huston smoking one of the cigarettes that killed him is from MUBI. The final smoking picture is of Huston as Noah Cross in Chinatown and is from Wikipedia, where it is mislabeled.)

Published on May 26, 2013 03:17

May 19, 2013

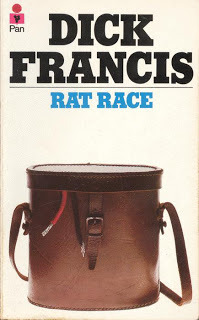

Dick Francis: Rat Race

It comes as something of a relief to have read a Dick Francis novel which I can't immediately recommend as a flawless small masterpiece.

It comes as something of a relief to have read a Dick Francis novel which I can't immediately recommend as a flawless small masterpiece.Rat Race is very good indeed. As with Smokescreen he refreshes the horse racing mileiu by making his hero peripheral to it — in this case he is the pilot of a small plane that carries trainers, owners and jockeys to the race tracks. And the flying world is beautifully evoked.

But Rat Race comes with a couple of semi-fatal flaws.

Both of these flaws relate to a character called Chanter (great name). Chanter is a hippie art teacher who is in the book as a spoiler for Nancy, who is the object of Chanter's affections as well as the hero's.

Now, Chanter is an interesting and amusing character.

He wears utterly outlandish costumes (one described as a "dark green chenille table cloth" with a hole in it for his head), which stretch the bounds of crediblity.

But, despite that, he's surprisingly three dimensional. A big boost to this feeling of reality is the fact that Nancy doesn't entire abjure his attentions and even, on some level, fancies him a little. Plus the fact that Chanter "really can draw".

No, the problem with Chanter is the way he talks.

I first noticed this issue in Smoke Screen with a young American character. Now, normally Dick Francis's dialogue is spot on.

Besides being vivid, amusing and informative it is also authentic. Hs horse-racing people, film makers and (in this novel) aviation folk all speak in an utterly convincing way.

I assume this is because Francis had a chance to observe such people, and listen to them, at close quarters. Not so with Americans and hippies, sadly.

The American in Smokescreen kept saying things like "sure" and "" in exactly the way that real Americans don't. (The way to nail American dialogue is to have them say things like "gotten" where an Enlgishman would say "got". The great Nigel Kneale knew this.)

And here Chanter says things like "You're a drag, man. I mean, cubic". Now, it's not impossible that such things were uttered at times by real live hippies. But they much more often came out of the mouths of dreadful cardboard stereotypes.

Strictly from Cliché City, man. Or should I say Trope Town?

Anyhow, this is the only Achilles heel I've detected so far in the writing of Dick Francis, who remains a genius and my hero.

There is one more problem with Rat Race, though.

This also relates to Chanter. What happens is that our hero and the alluring Nancy are getting closer and closer to, ahem, consumating their relationship... when this is suddenly kibboshed by the sort of arbitrary and far fetched misunderstanding which is a staple of bad romantic fiction.

This also relates to Chanter. What happens is that our hero and the alluring Nancy are getting closer and closer to, ahem, consumating their relationship... when this is suddenly kibboshed by the sort of arbitrary and far fetched misunderstanding which is a staple of bad romantic fiction. So she runs off (we think) with Chanter for a while, before everything is sorted out and normal service is resumed.

I would by no means advise you to steer clear of Rat Race just because of these minor imperfections.

The book also features the most sustained and nail-biting setpiece of suspense writing I've encountered in the novels of Dick Francis (and possibly anywhere). I'll only tell you that it involves an airplane.

The book also features the most sustained and nail-biting setpiece of suspense writing I've encountered in the novels of Dick Francis (and possibly anywhere). I'll only tell you that it involves an airplane.There are also the breathtaking sudden moments of unexpected violence. Francis really is a master of the form. And here he breaks new ground with his beautifully realised evocation of pilots and flying.

Despite the Chanter factor, I found Rat Race so gripping that I almost missed my station while reading it on the train.

(Yet again we have the admirable Jan-Willem Hubbers to thank for the stylish cover that begins this blog, with the photo by Colin Thomas. the Dick Francis Library cover is from Waterstones. The dynamic image photo image of the jockeys racing is from Fantastic Fiction. The green bomb cover is from Biblio Dot Com. The very nice first edition cover is again from Ash Rare Books. The painted cover is by Greg Montgomery and is from the artist's own website.)

Published on May 19, 2013 00:22

May 12, 2013

Philip MacDonald: More Colonel Gethryn

Anthony Ruthven Gethryn (the middle name is pronounced 'riven') was the detective protagonist created by the gifted British novelist and screenwriter Philip MacDonald. MacDonald is now largely, and undeservedly, forgotten.

Anthony Ruthven Gethryn (the middle name is pronounced 'riven') was the detective protagonist created by the gifted British novelist and screenwriter Philip MacDonald. MacDonald is now largely, and undeservedly, forgotten.And the Gethryn novels, possibly with the exception of his earliest outing, The Rasp (1924), are still worth reading.

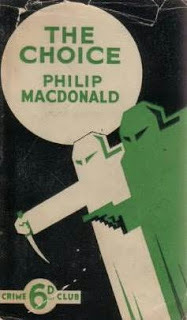

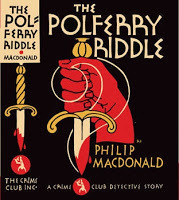

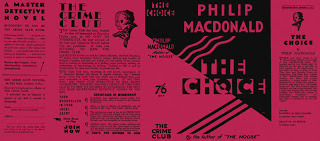

The Choice is the fifth novel in the series and was published in 1931. Interestingly, it begins as a classic 'locked room' type murder mystery, but then soon modulates into a chase thriller before returning to the locked room mystery at its conclusion.

MacDonald was an intelligent and imaginative writer and the way he blends and bends genre conventions is altogether admirable.

The Choice (aka The Polferry Mystery and The Polferry Riddle) also foreshadows the final, and perhaps finest, Gethryn adventure The List of Adrian Messenger in the way it presents a race to stop a killer completing a sequence of assasinations, and to work out the reason for his murderous spree.

It also prefigures a couple of the murder methods in that later novel — the small boat drowning and the spooked horse. For a little while I even thought that the motivation behind the killing of the victims on the list would be the same in both books.

But MacDonald is much too good a writer to duplicate himself like that and, thankfully, The Choice eventually explores very different territory to The List of Adrian Messenger.

But MacDonald is much too good a writer to duplicate himself like that and, thankfully, The Choice eventually explores very different territory to The List of Adrian Messenger. One thing about the Gethryn novels; even though he is a sleuthing genius, the police are never treated like dolts. There is an attitude of mutual respect — and affection — between Gethryn and the Scotland Yard officers. This was even true of the first novel The Rasp.

(I was perhaps a little hard on The Rasp in my earlier post. It did feature some excellent, vivid characterisation. Like the effeminate, corrupt private detective Mr Pebble, who only features on about one page but makes an indelible impression.)

And on a police procedure note, I was intrigued to see that even in 1931 the police issued the familiar caution: "Anything you tell us..." "I know, I know, may be taken down and used as evidence against me."

And on a police procedure note, I was intrigued to see that even in 1931 the police issued the familiar caution: "Anything you tell us..." "I know, I know, may be taken down and used as evidence against me."  Elsewhere in the novel, MacDonald is up to his old trick of rendering the dialogue of the lower orders phonetically, for the amusement of the reader. However, to his credit, he actually does a reversal of this procedure here when a taxi driver is asked to describe his fare. He says the man was a 'toff' and goes on to mimic the toff's voice as it commanded him: "Drave me lake L to Jook Squaw". Translation: "Drive me like hell to Duke Square."

Elsewhere in the novel, MacDonald is up to his old trick of rendering the dialogue of the lower orders phonetically, for the amusement of the reader. However, to his credit, he actually does a reversal of this procedure here when a taxi driver is asked to describe his fare. He says the man was a 'toff' and goes on to mimic the toff's voice as it commanded him: "Drave me lake L to Jook Squaw". Translation: "Drive me like hell to Duke Square."MacDonald actually has quite a good ear for this idiomatic stuff, and now I've read an example of him using it to mock the upper class as well as the working class, it sits a lot more comfortably with me.

And there's some fine little touches of descriptive prose: a floorboard is torn up "with a little crashing scream."

Incidentally the Mayflower Dell copy which I read, featuring the yellow lamp, is very misleading showing as it does the bloodstained cut throat razor. The whole point of the story is that the razor is mysteriously missing. But this isn't just artistic licence, it's fundamentally inaccurate in other ways. I won't say any more, except to add that the Black Dagger Crime edition, with its red cover, is much more on-target.

I'm keen to read some more Anthony Gethryn adventures. And if you're wondering what the image of the automobile is about, it's a French Voisin of the same vintage as the one Gethryn drives. (Also a favourite motor of the architect Le Corbusier.)

(Image credits. The generic but striking green, white and black Crime Club cover is from Fantastic Fiction. The beautiful hardcover dustwrappers, both UK and USA, are from the wonderful Facsimile Dust Jackets. The Vintage paperback with its jigsaw design (I'm beginning to realise this was a very stylish series) is from eBay. The red razor blade cover — much more relevant than some others — is from The Bunburyist, a blog which features a perceptive post about this novel by Elizabeth Foxwell. The Mayflower Dell yellow lamp cover is again from and is exactly the copy I bought and read. The radiator of the Voisin is from Beloblog, where I learned about the Le Corbusier connection.)

(Image credits. The generic but striking green, white and black Crime Club cover is from Fantastic Fiction. The beautiful hardcover dustwrappers, both UK and USA, are from the wonderful Facsimile Dust Jackets. The Vintage paperback with its jigsaw design (I'm beginning to realise this was a very stylish series) is from eBay. The red razor blade cover — much more relevant than some others — is from The Bunburyist, a blog which features a perceptive post about this novel by Elizabeth Foxwell. The Mayflower Dell yellow lamp cover is again from and is exactly the copy I bought and read. The radiator of the Voisin is from Beloblog, where I learned about the Le Corbusier connection.)

Published on May 12, 2013 12:37

May 4, 2013

Dick Francis: Smokescreen

I'd like to thank Mark, a reader of this blog, for recommending that Smokescreen should be my next Dick Francis novel.

I'd like to thank Mark, a reader of this blog, for recommending that Smokescreen should be my next Dick Francis novel.I read it and it's dynamite. I am more and more impressed with Francis. His stuff is so good — thank god there's so much of it to read.

There is an interesting development and expansion in these novels. Although they all feature the world of horse racing, Francis varies this formula by not necessarily making his protagonist part of that world.

So we have Edward Lincoln, nicknamed Link, hero of Smokescreen. He is, of all things, a movie star.

So we have Edward Lincoln, nicknamed Link, hero of Smokescreen. He is, of all things, a movie star.Now, this is a potentially disastrous choice of milieu and character, but the formidable Dick Francis pulls it off. He writes as knowledgeably about film making as he does about horses and jockeys.

Indeed, professional filmmakers admire the authenticity of his writing on the subject.

Another possible disaster area is the unusual location of the story. South Africa.

I assumed Smokescreen would just be a breezy thriller set in an 'exotic' location and that the political and racial nightmare of the country would be ignored. But, again, our author is far too clever for that. He cannily addresses the whole issue by letting one of his South African characters launch into an obtuse defence of her country — thereby subtly offering a critique of it.

I assumed Smokescreen would just be a breezy thriller set in an 'exotic' location and that the political and racial nightmare of the country would be ignored. But, again, our author is far too clever for that. He cannily addresses the whole issue by letting one of his South African characters launch into an obtuse defence of her country — thereby subtly offering a critique of it.But to hell with politics, this is a thriller and an outstanding one. The nerve wracking sequences of violence and suspense come out of nowhere and nail the reader utterly. I couldn't stop devouring the book. It was kind of an agonising pleasure.

The characters are also beautifully depicted, and given considerable depth and authenticity.

For example, Link has a brain damaged young daughter. In any other genre novel she would be allotted a huge chunk of the plot, and probably receive a miracle cure at the end. But here she is just briefly mentioned, to give a bittersweet three-dimensional quality to our hero's life. To make us care about him.

For example, Link has a brain damaged young daughter. In any other genre novel she would be allotted a huge chunk of the plot, and probably receive a miracle cure at the end. But here she is just briefly mentioned, to give a bittersweet three-dimensional quality to our hero's life. To make us care about him.These sort of details lend the book an indelible vividness and a sense of reality.

Best of all, Smokescreen features a blithe psychopath (to use Charles Willeford's phrase) of the kind who used to feature so memorably in the novels of John D. MacDonald.

A really chilling bad guy, to set against the likable and sympathetic hero.

And, as I've come to expect from Francis, there's notable moments of wit, perceptive writing, sharp observation and excellent dialogue.

Here we have the cinematographer admiring an attractive young woman: "Conrad took in her colour temperature with an appreciative eye."

Elsewhere a poised, snobbish woman learns that her friend is terminally ill: "her grief showing through the social gloss like a thistle among orchids."

Or: "A couple of vultures... perched on a nearby tree like brooding anarchists awaiting the revolution."

More Dick Francis, please.

Incidentally, the cover photo looks like some kind of stirrup...

It's a handcuff.

(Note to blog reader Dawn Over London: I hope you enjoyed Nerve by Dick Francis. Smokescreen is well worth a look, too, as you will have gathered.)

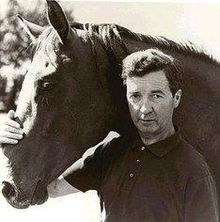

(Image credits: As is traditional, I used one of the boldly graphic Colin Thomas covers as the main image, and it's borrowed from Jan-Willem Hubbers' fine website. The stylish and apt "blue moon" cover is from eBay. The somewhat dull first-edition clapper board cover is from Ash Rare Books.The excellent photo of Dick Francis with a horse is from his Wikipedia entry. The yellow Pan cover is from Biblio.Com's Dick Francis page. The nice (though somewhat misleading — this book isn't much about horses, or about shooting at targets at all — did anyone even read it?) 'Dick Francis Library' cover is from Waterstones.)

Published on May 04, 2013 23:08

April 28, 2013

Philip MacDonald: The First and Last of Colonel Gethryn

Colonel Gethryn is Anthony Gethryn -- he hates to be referred to by his military rank. An intelligence officer in both World Wars, he consults with the police on an informal basis.

Colonel Gethryn is Anthony Gethryn -- he hates to be referred to by his military rank. An intelligence officer in both World Wars, he consults with the police on an informal basis.He is Philip MacDonald's detective hero and featured in a sequence of some twelve novels which began with The Rasp in 1924 and ended with The List of Adrian Messenger in 1959.

I started with the last book, and then proceeded to the first. It was an unconventional procedure, but an enlightening one.

By the time he wrote The List of Adrian Messenger (great title, by the way), Philip MacDonald was a writer fully in command of his craft with almost half a century of experience, and it shows. This is a taut, expertly plotted thriller with evocative locations, memorable characters and a compelling villain.

The bad guy here is reminiscent of the monstrous antagonists in Thomas Harris or John D. MacDonald.

Indeed, the scheming ruthless psychopath killing for gain could come straight out of the pages of one of John D. MacDonald's Travis McGee novels.

The List of Adrian Messenger is a race-against-time thriller where Gethryn has to work out who the victims are, and why, and identify the killer and stop him. It's beautifully done and well worth a read. It has hardly dated.

The same can't be said of The Rasp, which as I said was published in 1924 and was for decades regarded as a masterpiece and a classic of crime fiction in the great tradition.

The Rasp appears to be MacDonald's first solo effort. His earlier works were two novels under the pseudonym Oliver Fleming, written in collaboration with his father Ronald MacDonald -- a name which, to the modern reader, seems hilarious.

Given that The Rasp is effectively his first novel, and that Philip MacDonald was still three years away from his masterpiece Patrol, I guess one should cut him some slack.

However, I found The Rasp a major disappointment. It is a whodunnit and features a 'locked-room' style puzzle murder. Unfortunately, the solution to the puzzle wasn't sufficiently original, convincing or ingenious to impress yours truly.

This is in complete contrast to MacDonald's Rynox, written in 1930, which was also a locked room puzzle, and is a work of sheer genius which had me chuckling with awestruck delight.

Much worse than the weakness of the central conceit in The Rasp is the gooey romance which encumbers the book (in fact, three gooey romances). This gives rise to some of MacDonald's most unfortunate prose. I was particularly amused by the line "a dark proud face whose beauty was enhanced by its pallor."

But, as I said, within three years MacDonald would be writing the brilliant hard-boiled prose of Patrol. And even here in The Rasp there's much excellent writing, as when he describes the "low angry mutter of thunder."

And the other early Gethryn novels are by no means to be ignored. I'm currently reading the fifth one, from 1931, and it's turning out rather well.

I'll report about it soon.

(Note: I wish I could have included a link to the great Thomas Harris/Hannibal Lecter website Hannotations. But it has vanished and the real estate is now occupied by some jerks who want to offer links to "Lebanese Girls" and "Funny Funny Pictures". Like I'm going to click on those. Hannotations was a magnificent resource and if I'd known it was going to disappear I would have printed out every page. On the other hand, John D. MacDonald is very well served online, and Steve Scott's The Trap of Solid Gold, referenced above, is informative, detailed and a labour of love. Also, there were too many good Travis McGee websites for me to link to them all above. Check out this one by S. Rufener and also the handiwork of the admirable Book Slut.)

(Image credits: The striking black and white Bantam paperback of The List of Adrian Messenger (by Sanford Kossin, I think) is from Good Reads. The groovy German The List of Adrian Messenger is from Prisma 631 on Flickr. The Vintage jigsaw cover of Adrian Messenger is from Amazon. The Vintage jigsaw cover of The Rasp is from Paperback Swap. The wonderful early dustjackets of The Rasp, one British and two American, are from the magnificent Facsimile Dust Jackets site. I urge you to shop there.)

Published on April 28, 2013 01:33

April 21, 2013

Zen and the Art of Murder

Dashiell Hammett once wrote an essay about the most common — and annoying — mistakes in crime fiction.

Dashiell Hammett once wrote an essay about the most common — and annoying — mistakes in crime fiction.Number one on the list was for the writer to confuse an automatic pistol with a revolver. Hammett said: "A pistol, to be a revolver, must have something on it that revolves."

He wrote those words in 1930, but it's a lesson that still needs to be learned. Perhaps it seems like a nit-picking detail, but if the author gets something like this wrong it spoils the whole illusion of reality which is essential to the artifice of fiction: disbelief ceases to be suspended.

Which is why I was so disappointed when Michael Dibdin's marvellous Italian detective Aurelio Zen digs out a pistol obtained by his father when Zen was a little boy. It's a Beretta 9mm revolver.

Beretta are famous for their automatic pistols. They did, eventually, manufacture a couple of revolvers for the American market in the 1980s, but there was never a 9mm model and the period piece described by Dibdin simply doesn't exist.

Beretta are famous for their automatic pistols. They did, eventually, manufacture a couple of revolvers for the American market in the 1980s, but there was never a 9mm model and the period piece described by Dibdin simply doesn't exist.And that's a real pity, because in other respects Cabal, the novel in question, is a wonderfully diverting piece of crime fiction and Aurelio Zen is a great creation.

Moving through the corrupt world of Italian policing and politics, Zen is himself an amiably semi-corrupt individual. When he is summoned by the Vatican authorities to assist them in covering up a murder, his response is pretty much an enthusiastic 'sure thing'.

This is such a refreshing change from the unbending square jawed crusaders who dominate the literature.

This is such a refreshing change from the unbending square jawed crusaders who dominate the literature.And Dibdin writes very amusingly: "The stairwell was dark, and the timer controlling the lights had been adjusted for the agility of a buck chamois in rut rather than a middle-aged policeman going about his dubious business."

In this case, his dubious business is framing a suspect. But it turns out someone has arrived before him and (very ingeniously) murdered the man...

I also loved Zen's girlfriend Tania, who works in police administration, but in fact spends her days using the office's resources to run her thriving food wholesale business, selling local delicacies from her home town.

What's more, the way Dibdin handles his shadowy, sinister conspiratorial Vatican sect in this novel should be adapted as a model for other writers — notably Dan Brown.

It would make for a lot more fun.

There are eleven Aurelio Zen books.

The BBC did some adaptations for television, based on the first three: Ratking, Vendetta and Cabal. I missed these and the series was cancelled after one season.

I now regret both these facts.

(Note: the Dashiell Hammett essay I quoted was published in the Saturday Review of Literature on 7 June and 3 July 1930. Astonishingly, it isn't available on the internet, though there's some excerpts here. Until some kind soul types it out and posts it, you'll have to find it in a physical book, like Richard Layman's excellent Hammett biography Shadow Man, on pages 122-125. It's well worth a read. And the rare hybrid automatic-revolver Hammett mentions is described here.)

(Note: the Dashiell Hammett essay I quoted was published in the Saturday Review of Literature on 7 June and 3 July 1930. Astonishingly, it isn't available on the internet, though there's some excerpts here. Until some kind soul types it out and posts it, you'll have to find it in a physical book, like Richard Layman's excellent Hammett biography Shadow Man, on pages 122-125. It's well worth a read. And the rare hybrid automatic-revolver Hammett mentions is described here.)(Image credits: the book covers for Cabal, Ratking and Vendetta are all from the Faber website. Nice designs, folks. The DVD cover is from Silverdisc.com. The stylish Shadow Man cover is from Amazon. Buy a copy. They're going cheap.)

Published on April 21, 2013 03:49

April 14, 2013

Dick Francis: Nerve

Another cracking thriller by Dick Francis.

Another cracking thriller by Dick Francis.I'm currently writing a series of novels about a record collector turned detective. Someone asked me how many stories there can be concerning mystery, murder and mayhem revolving (ahem) around records?

My reply was, Dick Francis managed about three dozen concerning the world of jockeys and horse racing.

But I didn't realise how damned good they were.

Nerve concerns a jockey, Rob Finn who is just starting to build a reputation when that reputation is cruelly and deliberately sabotaged.

It is a riveting story of his attempts to salvage his career -- and gain retribution against his tormentor (Finn describes his plan of revenge to his cousin: "I told her. It took some time. She shivered. 'He didn't know what he was up against when he picked on you'.")

It is a riveting story of his attempts to salvage his career -- and gain retribution against his tormentor (Finn describes his plan of revenge to his cousin: "I told her. It took some time. She shivered. 'He didn't know what he was up against when he picked on you'.")And Francis can really write. His characters and background detail are beautiful.

Finn is the only non-musical member of a family of professional musicians. This is from a description of their sitting room: "A cello and a music stand rested side by side like lovers along the length of the sofa."

Elsewhere he describes a man struggling to lead a powerful, impatient horse "hanging on to his leading rein like a small child on a large kite."

There are many other lovely concise bits of scene setting. He talks about "the freezing dawn" and "a damp raw January afternoon". And immediately the reader is there.

There are many other lovely concise bits of scene setting. He talks about "the freezing dawn" and "a damp raw January afternoon". And immediately the reader is there. Nerve was written in 1964 and there is an interesting air of Cold War terror shimmering subtly in the background.

Amazingly, it was only his second novel.

Many thanks to my blog reader Frank Fair for pointing out that Stanley Kubrick was also a Dick Francis fan (pity he never adapted one of the novels) while another one was script writing guru Syd Fields, who praised Francis' depiction of film making.

Another reader Mark recommends Smokescreen so I'm delighted to say I've now obtained a copy of that, and I'm reading it next. Many thanks.

(Also, I'm hypnotised by this review of 1965's Odds Against, from The Sun: "a spot of kinkiness in the delectable shape of a sado-masochistic femme fatale.")

I love Francis' terse evocative titles, by the way.

(Image credits: Once again the striking Colin Thomas photo cover is from Jan-Willem Hubbers excellent and useful website, a terrific Dick Francis resource. The great first edition cover is from Wikipedia.

The Penguin edition with the stylish graphic design by Cato is from The Woman in the Wood's photostream on Flicker. The grey painted cover is by Greg Montgomery and the artist's website is here. The yellow Pan cover is from LeLivre.com via Antiqbook. This is the copy I read and I don't recommend it because the cover painting gives too much of the plot away, particularly the back cover. Do they think people read books without turning them over?)

The Penguin edition with the stylish graphic design by Cato is from The Woman in the Wood's photostream on Flicker. The grey painted cover is by Greg Montgomery and the artist's website is here. The yellow Pan cover is from LeLivre.com via Antiqbook. This is the copy I read and I don't recommend it because the cover painting gives too much of the plot away, particularly the back cover. Do they think people read books without turning them over?)

Published on April 14, 2013 01:19