Andrew Cartmel's Blog, page 37

April 6, 2014

Starred Up by Jonathan Asser

At first glance, from the trailers, Starred Up appeared to be just one more thuggish, thick ear British gangster movie, albeit one with a very odd title. But then I read an interview in Sight & Sound with the screenwriter, Jonathan Asser.

At first glance, from the trailers, Starred Up appeared to be just one more thuggish, thick ear British gangster movie, albeit one with a very odd title. But then I read an interview in Sight & Sound with the screenwriter, Jonathan Asser.Starred Up is a prison movie and Asser had worked for years in education, at Feltham Young Offenders Institution, and then Wandsworth Prison. Suddenly I was interested in the film. It was a rare instance of someone writing from a position of knowledge.

And it turns out Starred Up is a great film. Certainly one of the best of the year. I can't recommend it too highly... though it is unremittingly brutal, so be warned.

And it turns out Starred Up is a great film. Certainly one of the best of the year. I can't recommend it too highly... though it is unremittingly brutal, so be warned. The title refers to young offenders who are so violent and unmanageable that they are 'starred up', i.e. transferred to an adult prison. In this case, the young offender has a reason for wanting to be sent to a grown up jail. (Incidentally, the original title was 'L Plate' — sardonic prison slang for a life sentence.)

When Asser wasn't working in prisons he was writing poetry. And the visual quality of his poems suggested to an astute reader that he should try a screenplay. He took a shot at it, and after years of encouragement and mentoring he developed the brilliant script that is Starred Up. Perhaps the most crucial piece of advice was to change the nephew/uncle relationship to a son/father one. (A classic principle of screenwriting: always concentrate situations and make them more powerful.) Now the film suggests that its hero has deliberately plunged into the hell of adult prison in search of his father...

When Asser wasn't working in prisons he was writing poetry. And the visual quality of his poems suggested to an astute reader that he should try a screenplay. He took a shot at it, and after years of encouragement and mentoring he developed the brilliant script that is Starred Up. Perhaps the most crucial piece of advice was to change the nephew/uncle relationship to a son/father one. (A classic principle of screenwriting: always concentrate situations and make them more powerful.) Now the film suggests that its hero has deliberately plunged into the hell of adult prison in search of his father...Besides the outstanding script, Starred Up is also superbly directed, by David Mackenzie who made one of my favourite films of 2009, the offbeat and cynical Spread (you'll never forget the end title sequence!). And the cast of Starred Up is also first rate, including Jack O'Connell as the young inmate and Ben Mendelsohn, who was so great in Killing Them Softly, as his dysfunctional dad.

The film depicts a situation of violence, cruelty and utter hopelessness, yet it manages to find a glimmer of hope. It is extremely powerful. After the (very moving) conclusion there was spontaneous applause from audience at the Thursday night screening I attended — in Wandsworth, appropriately enough.

(Image credits: The black and white poster is from IMDB. The photo of Jonathan Asser beside the poster is from Film 4. The photo of O'Connell and Mendelsohn is from Coreplan. The colour poster is from Letterboxd.)

Published on April 06, 2014 01:34

March 30, 2014

Captain America By Markus & McFeely

It's getting embarrassing, all these movies based on Marvel comics. It used to be that I could dismiss at least half of them as junk. Now, to my chagrin, every one is a winner. It makes me seem like I have no critical faculties left. But I prefer the thesis that the films are simply getting better. More specifically, they're getting better

written

.

It's getting embarrassing, all these movies based on Marvel comics. It used to be that I could dismiss at least half of them as junk. Now, to my chagrin, every one is a winner. It makes me seem like I have no critical faculties left. But I prefer the thesis that the films are simply getting better. More specifically, they're getting better

written

.Captain America: the Winter Soldier is overlong and has some dull patches, but it's really good. The writing is excellent and even the bits of the movie that shouldn't work — the overblown action scene at the beginning, the obligatory car chase — do work. In fact, this film features the first car chase in years which actually had me engaged. I might even have been on the edge of my seat, but I'm reluctant to admit that.

On top of that, one of the three big surprises in the script did surprise me. Completely. That's a hell of a good result.

The only thing I really didn't like was the wonderful Scarlett Johansson being portrayed as a redhead. (Ironically enough.) Plus the character she plays, Black Widow, is a total bust as a superhero. Her special power? She shoots people with guns. Awe inspiring.

The only thing I really didn't like was the wonderful Scarlett Johansson being portrayed as a redhead. (Ironically enough.) Plus the character she plays, Black Widow, is a total bust as a superhero. Her special power? She shoots people with guns. Awe inspiring.  Speaking of which, the gun battles were exceptional. If you were ever caught up in something like that in real life it would be a terrifying, unforgettable, almost hallucinatory experience. Whereas gunfights in movies are a big yawn. Yet the set piece on the freeway in this one actually caught a whiff of how frightening and extraordinary such violence would really be. It crackled with fear and brutality.

Speaking of which, the gun battles were exceptional. If you were ever caught up in something like that in real life it would be a terrifying, unforgettable, almost hallucinatory experience. Whereas gunfights in movies are a big yawn. Yet the set piece on the freeway in this one actually caught a whiff of how frightening and extraordinary such violence would really be. It crackled with fear and brutality.It's the sort of sequence that James Cameron, at his best, can deliver magnificently. I still remember seeing the first Terminator movie. There had never been a shootout like that in the history of cinema. And Captain America: the Winter Soldier, for a few seconds, put me in mind of it. No small achievement.

This film was written by Christopher Markus & Stephen McFeely (note that ampersand) who wrote the Narnia trilogy, the first Captain America picture and the recent excellent Thor movie. It was based on comics written by Ed Brubaker. The directors were Joe Russo and Anthony Russo, who previously worked in television comedy, and a lot of credit must go to them, too.

This film was written by Christopher Markus & Stephen McFeely (note that ampersand) who wrote the Narnia trilogy, the first Captain America picture and the recent excellent Thor movie. It was based on comics written by Ed Brubaker. The directors were Joe Russo and Anthony Russo, who previously worked in television comedy, and a lot of credit must go to them, too.If only the film makers had taken another leaf from James Cameron's book. When he was making Titanic he'd originally included a subplot about a stolen diamond which involved a chase and guns and shooting. But when he was completing the film he realised that this was just a silly distraction from the main thrust of the story — the tragic sinking of the ship. So he cut it.

In keeping with a general tendency among Hollywood blockbusters, Captain America: the Winter Soldier is overloaded with action — bloated almost to the point of torpor — and it doesn't quite know when to quit. It could do with some Cameron-style cuts. But it's nonetheless clever, engrossing, thrilling and brilliantly made.

In keeping with a general tendency among Hollywood blockbusters, Captain America: the Winter Soldier is overloaded with action — bloated almost to the point of torpor — and it doesn't quite know when to quit. It could do with some Cameron-style cuts. But it's nonetheless clever, engrossing, thrilling and brilliantly made.Will these fine Marvel movies never stop?

(Image credits: All pictures from Ace Show Biz.)

Published on March 30, 2014 01:31

March 23, 2014

Veronica Mars: the Film

Okay, I'll put you out of your suspense — and me out of mine — I just saw the Veronica Mars movie and it's good. It's better than good. It's a delight. Everything is in place. The noir setting, the tight plotting, the fine characterisation, the sassy dialogue. I loved it.

Okay, I'll put you out of your suspense — and me out of mine — I just saw the Veronica Mars movie and it's good. It's better than good. It's a delight. Everything is in place. The noir setting, the tight plotting, the fine characterisation, the sassy dialogue. I loved it.The film was only playing in one cinema in London, which at first seemed to me a depressingly bad sign. But it's thriving in that one screen — of course it is, legions of fans of the TV series want to see it. And in North America it seems to have achieved much wider distribution. (My brother lives in a small town in Canada and it's in the movie theatre there.)

It's amazing how easily the film transfers its basic concept — teen detective in high school — to the adult world without losing anything. It turns out that what were originally the main selling points — teen, high school — are actually irrelevant. What matters are the characters, Veronica (Kristen Bell), her dad (Enrico Colantoni), her on-and-off boyfriend Logan Echolls (Jason Dohring).

It's amazing how easily the film transfers its basic concept — teen detective in high school — to the adult world without losing anything. It turns out that what were originally the main selling points — teen, high school — are actually irrelevant. What matters are the characters, Veronica (Kristen Bell), her dad (Enrico Colantoni), her on-and-off boyfriend Logan Echolls (Jason Dohring). Rob Thomas, who created the show (inspired by the teenage girls he knew when he was a teacher) has produced and directed the film. He also wrote the story and co-wrote the screenplay, in collaboration with Diane Ruggiero. Ruggiero was one of the mainstays of the original TV series. She wrote the classic 'Betty and Veronica' episode in which Veronica goes undercover at another high school, calling herself Betty and saying she's transferred from Riverdale High (both cheeky references to Archie comics). Working with Thomas, she's delivered a wonderful film.

Rob Thomas, who created the show (inspired by the teenage girls he knew when he was a teacher) has produced and directed the film. He also wrote the story and co-wrote the screenplay, in collaboration with Diane Ruggiero. Ruggiero was one of the mainstays of the original TV series. She wrote the classic 'Betty and Veronica' episode in which Veronica goes undercover at another high school, calling herself Betty and saying she's transferred from Riverdale High (both cheeky references to Archie comics). Working with Thomas, she's delivered a wonderful film. My only reservation is that it contains some spoilers for people who — like me — haven't seen all three series of the TV show. (I did my best, but my series 2 boxed set only plonked through my letter box while I was out seeing the movie.)

My only reservation is that it contains some spoilers for people who — like me — haven't seen all three series of the TV show. (I did my best, but my series 2 boxed set only plonked through my letter box while I was out seeing the movie.) I suspect the film will be a hit. A modest hit, perhaps, but that's all it needs to be. After all, it has a modest budget — I believe about six million dollars — which was raised up front through its Kickstarter campaign. So I'm sure it will not only break even, it will go into profit. Which raises the possibility of sequels

I suspect the film will be a hit. A modest hit, perhaps, but that's all it needs to be. After all, it has a modest budget — I believe about six million dollars — which was raised up front through its Kickstarter campaign. So I'm sure it will not only break even, it will go into profit. Which raises the possibility of sequelsThe success of Veronica Mars is heartening not only in itself, but because it suddenly gives hopes of a cinematic afterlife for any TV series with a devoted cult following which is cancelled before its time. This was a genuine example of people-power winning out over the bone headed decisions of executives. The idea of low budget, niche market, crowd-pleasing movies is immensely appealing. Let's hope it's a sign of things to come.

(Image credits: all the pics are from Ace Show Biz.)

Published on March 23, 2014 01:15

March 16, 2014

Veronica Mars by Rob Thomas

I've been aware of Veronica Mars for years but I've only just now found time to catch up with this excellent TV show. (Translation: I finally found a boxed set that was cheap enough.) A teen noir set in a California high school it's involving, funny, stylish and brilliantly written.

I've been aware of Veronica Mars for years but I've only just now found time to catch up with this excellent TV show. (Translation: I finally found a boxed set that was cheap enough.) A teen noir set in a California high school it's involving, funny, stylish and brilliantly written. Veronica (Kristin Bell) is the eponymous teenage private eye, working for her dad Keith who had to set up his detective agency when he was unjustly kicked out as the local chief of police.

Created by Rob Thomas, it has sharp characterisation and it's consistently funny. When Veronica goes on a stakeout her dad warns her to "Take back up." It turns out that Back Up is their pet dog, who pluckily launches himself on the bikers who try to molest Veronica, and smartly drives them off, jaws snapping.

Created by Rob Thomas, it has sharp characterisation and it's consistently funny. When Veronica goes on a stakeout her dad warns her to "Take back up." It turns out that Back Up is their pet dog, who pluckily launches himself on the bikers who try to molest Veronica, and smartly drives them off, jaws snapping.And the dialogue is lovely. In an episode written by Harry Winer we have the following exchange. Veronica, who is a magnet for trouble, says to her fellow social outcast Wallace "I need a favour." Wallace says, "Why did the hair on the back of my neck just stand up?"

I love this show. My only criticism is the way some flashbacks and fantasy scenes are shot. When Veronica's ex boyfriend comes off his medication he starts to hallunicate. His dead sister (Veronica's best friend, played by Amanda Seyfried) comes and sits on the couch with him, chatting happily despite her lethal head wound.

I love this show. My only criticism is the way some flashbacks and fantasy scenes are shot. When Veronica's ex boyfriend comes off his medication he starts to hallunicate. His dead sister (Veronica's best friend, played by Amanda Seyfried) comes and sits on the couch with him, chatting happily despite her lethal head wound.The scene is shot with a greenish tinge and smoke floating in the background... in fact, they do everything except run a caption on the screen reading It's an hallucination, folks! I assume some suited dullard insisted on this to prevent audience confusion — those suited dullards really do have a rock-bottom opinion of their viewers.

Instead, the scene should have been staged in as naturalistic fashion as possible. This would have been far more effective and creepy — and more like a real hallucination. (That's the way Polanski would have shot it.)

Instead, the scene should have been staged in as naturalistic fashion as possible. This would have been far more effective and creepy — and more like a real hallucination. (That's the way Polanski would have shot it.)Anyway, minor quibble. Veronica Mars may well be my favourite US TV series of all time. Individual episodes are delightful but the entire first season adds up to an arc-story of breathtaking adroitness. It was a whodunnit which completely pulled the wool over my eyes.

And in the course of researching this post I discovered that Veronica Mars, which ran for three seasons before being cancelled in 2007, is alive and well as a movie project. The feature film was first proposed by Rob Thomas when the series was cancelled, but Warner Bros. passed on it. Earlier this year Thomas launched a Kickstarter campaign to fund the project. It set a new record when it reached its two million dollar goal in less than ten hours, and eventually topped out at nearly six million dollars.

The film has now been shot and and indeed was released in the UK this week (albeit in a handful of cinemas) and as a digital download.

I notice that Rob Thomas didn't start working on the movie script until the two million dollars were in place. That's my boy. Professional writers everywhere will love him for that.

I notice that Rob Thomas didn't start working on the movie script until the two million dollars were in place. That's my boy. Professional writers everywhere will love him for that.(Image credits: the DVD cover is from Wikipedia as is the shot with Veronica and her dad, gun in hand. The shot of Amanda Seyfried with her head wound is from Fanpop. The nifty noir poster is from Telestrekoza. Very Very Veronica is from Rolemancer, another Russian site. The Russians seem big on Veronica. )

Published on March 16, 2014 09:44

March 9, 2014

More Thoughts on Dune

Here I am following up my earlier post on Dune by Frank Herbert... I had thought, a tad optimistically, that I'd said all I needed to say about this excellent novel. After all, one post was enough to wrap up other childhood favourites like Watership Down and The Hobbit. No disrespect to those masterpieces — I'm not sure that I don't actually prefer Watership Down to Dune, in terms of pure storytelling — but Herbert's book deserves and demands further exploration.

Here I am following up my earlier post on Dune by Frank Herbert... I had thought, a tad optimistically, that I'd said all I needed to say about this excellent novel. After all, one post was enough to wrap up other childhood favourites like Watership Down and The Hobbit. No disrespect to those masterpieces — I'm not sure that I don't actually prefer Watership Down to Dune, in terms of pure storytelling — but Herbert's book deserves and demands further exploration.At over 500 pages, Dune is longer than either of those novels. But that isn't why. While all three books represent detailed creations of imaginary worlds, Dune is more packed with ideas than the others. It reflects — or perhaps anticipates — such major 1960s concerns as ecology and mind expanding drugs.

The ecological aspects of the book come across in Herbert's loving description of the desert and the power and detail of his imaginary world. Everything on Arakis is detailed in terms of water and its scarcity. ("The flesh belongs to the person but his water belongs to the tribe.") I've never forgotten the stillsuits, the ingenious garments the Fremen wear to preserve and recycle the water of their bodies. And then of course there are the giant sand worms and their mysterious relationship with the hallucinogenic spice.

The ecological aspects of the book come across in Herbert's loving description of the desert and the power and detail of his imaginary world. Everything on Arakis is detailed in terms of water and its scarcity. ("The flesh belongs to the person but his water belongs to the tribe.") I've never forgotten the stillsuits, the ingenious garments the Fremen wear to preserve and recycle the water of their bodies. And then of course there are the giant sand worms and their mysterious relationship with the hallucinogenic spice.Which brings us to the druggy aspects of the book. At times Herbert's prose is positively trippy: after Paul drinks the Water of Life "He felt that his head had been separated from his body and restored with odd connections. His legs were remote and rubbery... Paul felt the drug begin to have its unique effect on him, opening time like a flower."

Elsewhere in the book, the elaborate political intrigues are also rather well handled — "Feints within feints within feints." In stark contrast to, say, the science fiction politics of The Star Wars movies which, to this viewer at least, made no sense at all.

Elsewhere in the book, the elaborate political intrigues are also rather well handled — "Feints within feints within feints." In stark contrast to, say, the science fiction politics of The Star Wars movies which, to this viewer at least, made no sense at all.And as I touched on in my last post, Dune is memorable for some beautiful descriptions, usually related to the desert landscape. When Paul is waiting tensely for an attack to commence "He felt time creeping like an insect working its way across an exposed rock." Or dawn on the desert: "A faint green-pearl luminescence etched the eastern horizon." Or this evocation of a storm: "The horsetail twistings of blown sand could be seen against the dark of the sky."

Indeed, the climactic battle of the book takes place in the same kind of eerie storm light that presided over the rabbits' escape from Efrafa in Richard Adams' Watership Down. Brilliant stuff.

Indeed, the climactic battle of the book takes place in the same kind of eerie storm light that presided over the rabbits' escape from Efrafa in Richard Adams' Watership Down. Brilliant stuff.But the single most striking thing about Dune on this re-reading was Frank Herbert's prescience. He anticipated certain aspects of our modern world with disturbing accuracy. When he talks of his desert warriors with their prophet, religious fervour, suicide commandos, and holy war it now gives us a chill. The fanaticism of the Fremen has taken on an unsettling new dimension. When he writes "His people scream his name as they leap into battle. The women throw their babies at us and hurl themselves onto our knives to open a wedge for their men to attack us," it has an effect on the 21st Century reader that Herbert could never have anticipated.

This both strengthens the book and undermines it — events in the real world have rendered Dune simultaneously more relevant than ever, and less pleasurable to read.

(Image credits: All the book covers are from Good Reads. They include Polish, Spanish and French editions. The first illustration is of the rather handsome Barnes & Noble leather bound collectible edition. A couple weeks ago this was available for less than twenty dollars. Now it seems to be out of print and greedy profiteers are charging about a hundred bucks for it. So it goes...)

Published on March 09, 2014 01:30

March 2, 2014

Person of Interest by Jonathan Nolan

I was going cold turkey having finished watching Season One of the magnificent Veronica Mars (is this the finest TV series of all time?) when a friend came to my rescue by recommending Person of Interest.

I was going cold turkey having finished watching Season One of the magnificent Veronica Mars (is this the finest TV series of all time?) when a friend came to my rescue by recommending Person of Interest.What a first-rate, beautifully crafted show this is. It's created by Jonathan Nolan, screenwriter for his brother Christopher's Batman films. And, indeed, if you look closely it is a cheeky little rewrite of the Batman myth.

Batman is a high-tech billionaire and a vigilante combat master. If you split that into two characters you get Finch, played by Michael Emerson and Reese played by Jim Caviezel, both of whom are splendid in Person of Interest.

The concept of the show is simple, strong and endlessly fertile. It's essentially a reworking of (and a considerable improvement on) the movies Eagle Eye and Minority Report: Reese has created a super computer, called 'The Machine', which uses surveillance data to spot patterns of behaviour. When it senses a lethal crime is imminent, it spits out a social security number.

This person of interest may be the victim — or possibly the perpetrator. This is one of the brilliant little strokes which make this such a clever and endlessly entertaining show.

This person of interest may be the victim — or possibly the perpetrator. This is one of the brilliant little strokes which make this such a clever and endlessly entertaining show.Finch built the computer for the government to catch terrorists. But it also spots deadly crime of the vanilla, domestic variety and the government just isn't interested in those. So Finch decides to deal with them himself, enlisting the assistance of troubled former black-ops warrior Reese.

What ensues is some of the finest television drama available, splendidly crafted, smart and funny. A couple of the episodes in the first season are no more than expert entertainment. But most of them have something extra.

What ensues is some of the finest television drama available, splendidly crafted, smart and funny. A couple of the episodes in the first season are no more than expert entertainment. But most of them have something extra.Like Number Crunch by Patrick Harbinson which adroitly takes Reese's nemesis, the police detective Carter, and turns her into his ally, Super by David Slack which cheekily borrows the notion of Rear Window and energetically subverts it, and Wolf and Cub by Nic Van Zeebroeck & Michael Sopczynski which deliberately evokes the Lone Wolf and Cub manga series but develops the idea very movingly as Reese partners with a young ghetto kid out to avenge his brother's death.

This is great televsion. It's in its third season. I hope it runs for decades.

(Image credits: The DVD cover is from Amazon. Reese with the handgun is from TV Dot Com. The surveillance image of Finch is from Sci Fi Empire. The other images are from the official CBS website for the show, which is cumbersome to navigate — just try clicking all the way back to the Episode 1, Season 1 Gallery — and has a remarkably dull selection of photos. Sigh.)

Published on March 02, 2014 01:21

February 23, 2014

Dune by Frank Herbert

I'm continuing my series on rediscovering great books of my childhood. After Watership Down and The Hobbit, we now have Frank Herbert's Dune.

I'm continuing my series on rediscovering great books of my childhood. After Watership Down and The Hobbit, we now have Frank Herbert's Dune. Herbert's writing wasn't as instantly engaging as Tolkien's or Richard Adams'. Dune is full of odd names and terminology — come to think of it, so were The Hobbit and Watership Down — yet in Herbert's case, the prose is somewhat dense and awkward, difficult to get into.

But as soon as we reach Chapter 2, which introduces the evil Baron Harkonnen and his plans to destroy our heroes, the Atreides clan, the story achieves escape velocity. Herbert does something brilliant here. He immediately tells the reader the identity of the traitor in the Atreides' midst.

So we spend the next 160 pages in a state of agonising suspense watching the characters we care about sleepwalk towards their doom, before the betrayal is finally (and bloodily) enacted and the trap is sprung.

As soon as we arrive on the planet Arrakis (Dune to you) Frank Herbert's prose really takes flight. His descriptions of the desert world bring it to vivid life: "chasms of tortured rock, patches of yellow-brown crossed by black lines of fault shattering. It was as though someone had dropped this ground from space and left it where it smashed." And "the cliff lifting golden tan in the morning light." It's obvious that, as with Edward Abbey, here we have a writer who loves the harsh beauty of his desert landscapes.

Herbert is also adept at evoking the futuristic machinery and technology, making it seem real through the use of small, telling detail. Like the personal force fields that act as shields to protect the wearer as Paul and his trainer fence with rapiers: "The air within their shield bubbles grew stale... With each new shield contact the smell of ozone grew stronger."

Herbert is also adept at evoking the futuristic machinery and technology, making it seem real through the use of small, telling detail. Like the personal force fields that act as shields to protect the wearer as Paul and his trainer fence with rapiers: "The air within their shield bubbles grew stale... With each new shield contact the smell of ozone grew stronger." Or his depiction of the ornithopters they use to fly over the barren deserts of Arrakis. Herbert makes them seem real through small, subtle detail ("the craft creaked as the others clambered aboard") and then he deploys them in the great sequence where they have to evacuate a massive Sand Crawler vehicle because of the approach of a giant worm, bent on their destruction. The personnel pour into the Duke's squad of small ornithopters and take to the skies: "Aircraft began lifting off the sand around them. It reminded the Duke of... carrion birds lifting away from the carcass of a wild ox."

And the wonderful portrayal of the gargantuan worms themselves, their "uncaring majesty" as they go sliding through the sand.

And the wonderful portrayal of the gargantuan worms themselves, their "uncaring majesty" as they go sliding through the sand.However, what really keeps the reader entranced is the intoxicating combination of action and suspense as Paul Atreides and his mother Jessica are plunged into peril after peril while they discover this strange new world.

Add this beautifully conjured world to an irresistible adventure story and a fascinating array of concepts and you begin to see the elements which make Dune such a classic.

Add this beautifully conjured world to an irresistible adventure story and a fascinating array of concepts and you begin to see the elements which make Dune such a classic.I'm delighted that another beloved book of my childhood has withstood the years so well.

(Image credits: As usual, I have taken a selection of the covers from Good Reads. And, as usual, many of my favourites were either missing or inadequate images. So the cover of the copy I'm actually reading, with the big gold lettering by Howard J. Shaw and the Gerry Grace art featuring the guys riding the worms — spoiler alert! You shouldn't put stuff like that on the covers, you silly publishers — is from a mysterious Russian site. Beware pop-ups if you go to it.

The lovely Illustrated Dune cover, with art by the great John Schoenherr, is from the blog of Schoenherr's son Ian. Just as Pauline Bayne was the finest illustrator for the works of Tolkien and for Richard Adams' Watership Down, Schoenherr was the perfect Dune artist. The magnificent John Schoenherr cover for the original Analog magazine serialization (entitled Dune World) is from the excellent Ski-Ffy. The handsome Gollancz 'yellow jacket' 50th anniversary hardcover image is taken from eBay.)

The lovely Illustrated Dune cover, with art by the great John Schoenherr, is from the blog of Schoenherr's son Ian. Just as Pauline Bayne was the finest illustrator for the works of Tolkien and for Richard Adams' Watership Down, Schoenherr was the perfect Dune artist. The magnificent John Schoenherr cover for the original Analog magazine serialization (entitled Dune World) is from the excellent Ski-Ffy. The handsome Gollancz 'yellow jacket' 50th anniversary hardcover image is taken from eBay.)

Published on February 23, 2014 02:51

February 16, 2014

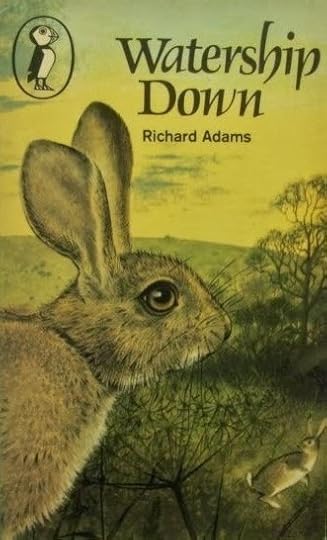

Watership Down by Richard Adams

Having just enjoyed re-reading The Hobbit, the next great novel to revive from my childhood is Richard Adams's Watership Down. I was partly prompted to do this by hearing an excellent radio dramatisation.

Having just enjoyed re-reading The Hobbit, the next great novel to revive from my childhood is Richard Adams's Watership Down. I was partly prompted to do this by hearing an excellent radio dramatisation.But Watership Down proved to be a felicitous choice, not just because it is an immensely pleasurable read, but because of the pronounced similarity to Tolkien.

I'd never considered this before, but it really struck me now: both Adams and Tolkien write in a cosy, very English voice — the rabbits say things like "I'm sorry, old chap." Both writers have a deep love of nature and offer intoxicating descriptions of the countryside: "June was moving towards July and high summer. Hedgerows and verges were at their rankest and thickest. The rabbits sheltered in dim-green, sun-flecked caves of grass, flowering marjoram and cow-parsley."

And, like Tolkien, Adams has created a coherent, self-contained fantasy world complete with history, folklore, mythology, a language of its own — and maps.

And, like Tolkien, Adams has created a coherent, self-contained fantasy world complete with history, folklore, mythology, a language of its own — and maps.(And, by an odd coincidence, both writers had Pauline Baynes as their definitive illustrator. She did the beautiful book cover at the beginning of this post, just as she did with The Hobbit last week.)

Best of all, both these writers can tell a thunderingly good story which utterly immerses the reader in their created worlds. This is not least because they both understand that a great adventure story requires a great villain. Where The Hobbit had Smaug, Watership Down has General Woundwort, the iron-willed tyrant who rules the totalitarian warren Efrafa. He's a truly formidable bad guy.

But he isn't two-dimensional. Adams clearly admires Woundwort and the readers ends up, grudgingly, feeling the same. Indeed, Woundwort is tempted at one point to become a good guy: "At that moment, in the sunset on Watership Down, there was offered to General Woundwort the opportunity to show whether he was the leader of vision and genius which he believed himself to be, or whether he was no more than a tyrant with the courage and cunning of a pirate."

But he isn't two-dimensional. Adams clearly admires Woundwort and the readers ends up, grudgingly, feeling the same. Indeed, Woundwort is tempted at one point to become a good guy: "At that moment, in the sunset on Watership Down, there was offered to General Woundwort the opportunity to show whether he was the leader of vision and genius which he believed himself to be, or whether he was no more than a tyrant with the courage and cunning of a pirate." (Luckily for the adventure story, Woundwort plumps for the latter.)

(Luckily for the adventure story, Woundwort plumps for the latter.)This sort of nuanced, shaded characterisation is a feature of the book: Hazel is uncertain that he's worthy of leadership and only gradually grows into the role, while Bigwig starts off as a heavy and only gradually becomes sympathetic — indeed, heroic. He's magnificent as the final battle approaches, unafraid of Woundwort and spoiling for a fight

In fact Bigwig's line of dialogue when he confronts Woundwort has stayed in my mind ever since I read it as a kid: "Silflay hraka u embleer rah." Which roughly translates as "Eat shit you stinking boss."

The book is an addictive, engrossing read, packed with magnificent set-pieces. Notably the immensely suspenseful escape from Efrafa in a gorgeously described storm: "a long roll of thunder sounded from the valley beyond. A few great, warm drops of rain were falling. Along the western horizon the lower clouds formed a single purple mass, against which distant trees stood out minute and sharp."

The book is an addictive, engrossing read, packed with magnificent set-pieces. Notably the immensely suspenseful escape from Efrafa in a gorgeously described storm: "a long roll of thunder sounded from the valley beyond. A few great, warm drops of rain were falling. Along the western horizon the lower clouds formed a single purple mass, against which distant trees stood out minute and sharp."And of course there is the unforgettable final battle when Woundwort and his legions attack our heroes' burrow.

The suspense and action are brilliantly evoked, but there's much more to the book than that. Adams shows the rabbits struggling with abstract concepts, such as the boat they encounter, or the mosaic made by some very strange rabbits — only a few exceptional individuals among our heroes, like Blackberry and Fiver can grasp these things. This gives Watership Down an edge of intelligence and profound insight which most books of any kind lack. Let alone a thriller about rabbits ostensibly written for children.

The suspense and action are brilliantly evoked, but there's much more to the book than that. Adams shows the rabbits struggling with abstract concepts, such as the boat they encounter, or the mosaic made by some very strange rabbits — only a few exceptional individuals among our heroes, like Blackberry and Fiver can grasp these things. This gives Watership Down an edge of intelligence and profound insight which most books of any kind lack. Let alone a thriller about rabbits ostensibly written for children.This was a tremendously rewarding novel to re-read. It gave me as much pleasure as it did the first time around, decades ago.

Next on my pile of books: Richard Adams's second novel Shardik.

Next on my pile of books: Richard Adams's second novel Shardik.(Image credits: As usual, most of the covers are from the useful Good Reads, including the rather terrific art for the audio book version; I tried to identify the artist, but haven't been able to yet. But, bizarrely (yet typically) the best cover and the edition I actually re-read, the lovely Pauline Baynes original 1973 Puffin edition, is almost impossible to find on the internet. So for the main image at the beginning of this post I had to resort to a slightly tilted postcard of the cover I found for sale on eBay. And the Italian cover was sourced from the Italian site Fantasy Magazine.)

Published on February 16, 2014 01:32

February 9, 2014

The Hobbit by JRR Tolkien

Pete Jackson's recent film adaptation of The Hobbit — I'm not going to provide a link to it; it's all over the internet — which has now reached its second part, spurred me to take the novel down off my shelf and re-read it. (Actually I borrowed my young nephew's more expendable non-vintage paperback to read on buses and trains.)

Pete Jackson's recent film adaptation of The Hobbit — I'm not going to provide a link to it; it's all over the internet — which has now reached its second part, spurred me to take the novel down off my shelf and re-read it. (Actually I borrowed my young nephew's more expendable non-vintage paperback to read on buses and trains.)I initially had some niggles about the book. Well, one niggle. Tolkien used anachronistic analogies which seemed to jar the reader (or this reader) out of the ancient fantasy world of the story. Similes including a sound "like the whistle of an engine", knowing a route "as well as you do to the nearest post office" and a "smell like gunpowder" in a pre-gunpowder world.

But then I realised this was utterly deliberate. Tolkien here is what we call an omniscient narrator. He address the reader directly, in an informal and colloquial voice — and was after all aiming at a young audience. Which also explains and forgives the cosy tea-and-crumpets-at-the-fireside tone the book often has

But then I realised this was utterly deliberate. Tolkien here is what we call an omniscient narrator. He address the reader directly, in an informal and colloquial voice — and was after all aiming at a young audience. Which also explains and forgives the cosy tea-and-crumpets-at-the-fireside tone the book often hasNow that's over, let's get to the goodies, of which there are many. There's amusing, authentic sounding dialogue (notably from the trolls), fine violent fights, rhapsodic portrayal of the countryside and wildlife — "the patches of rabbit-cropped turf, the thyme and the sage and the marjoram, and the yellow rockroses all vanished" — and wonderful moody descriptions, like the "enormous uncanny darkness" of Mirkwood, or "furtive shadows that fled from the approach of their torches" or the moment when "it seemed as if darkness flowed out like a vapour from the hole in the mountain-side."

I also really liked this sketch of Thorin, after he's been floated down a river in a barrel and left overnight: "out crept a most unhappy dwarf... He had a famished and a savage look like a dog that has been chained and forgotten in a kennel for a week."

And Tolkien's characterisation is often marvellous, especially when he's discussing Smaug, the terrifying, gold-besotted dragon snoozing on his horde of treasure. Smaug's name may today suggest an item of furniture from Ikea, but Tolkien brings him unforgettably to life. As Bilbo approaches with trepidation the dragon's lair he hears "a rumble as of a gigantic tom-cat purring."

Smaug is genuinely fearsome, especially when he realises he's been robbed. "Up he soared blazing into into the air and settled on the mountain-top in a spout of green and scarlet flame." (And our heroes' poor old ponies don't fare too well, between Smaug and the goblins...)

I also particularly enjoyed the implicit class-war edge when Tolkien says of Smaug, "His rage passes all description — the sort of rage that is only seen when rich folk that have more than they can enjoy suddenly lose something that they have long had but have never before used or wanted."

What's more, Tolkien has a surprisingly line of wit and understatement. "Smaug had rather an overwhelming personality," he remarks at one point. And Bilbo calls him "Smaug the unassessably wealthy." And, in a priceless moment, Smaug goes flapping off towards the lake-town Esgaroth whose people are expecting the fulfilment of prophecies promising untold wealth coming back to them from the dragon's mountain. Instead what they get is an apocalyptic inferno and the fiery wrath of Smaug.

"The prophecies had gone rather wrong," remarks Tolkien.

But even better than Smaug is Thorin, leader of the dwarfs. For the entire book he has been likable enough and sympathetic — one of the good guys. But at the end he turns into an impressive bad guy and gives the plot a sudden new burst of energy.

Maddened by gold and corrupted in a manner worthy of worthy of B. Traven's characters in Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Thorin refuses to share the hard-won treasure wrested from the dragon and goes to war against those who should be his allies and friends.

In many ways it's the best part of the book and gives depth and complexity and sophistication to what was regarded as a children's novel.

(Image credits: all the book covers are from Good Reads including the one at left ('International Children's Bestseller') with the cover art by Max Meinzold, which I borrowed from my nephew. Thank you, Simon. But the main illustration is by the woman I consider the greatest of all Tolkien artists, Pauline Bayne. It was taken from the wonderful Bayne's own website. And there's an article about her Tolkien art here.)

(Image credits: all the book covers are from Good Reads including the one at left ('International Children's Bestseller') with the cover art by Max Meinzold, which I borrowed from my nephew. Thank you, Simon. But the main illustration is by the woman I consider the greatest of all Tolkien artists, Pauline Bayne. It was taken from the wonderful Bayne's own website. And there's an article about her Tolkien art here.)

Published on February 09, 2014 02:08

February 2, 2014

Black Cargoes by Daniel P. Mannix

Ridley Scott's film Gladiator was conceived by screenwriter David Franzoni, and Franzoni got the idea from a book called Those About to Die by Daniel P. Mannix. He describes Mannix's book as "sort of a tawdry slash semi-serious novel about the Colosseum."

Ridley Scott's film Gladiator was conceived by screenwriter David Franzoni, and Franzoni got the idea from a book called Those About to Die by Daniel P. Mannix. He describes Mannix's book as "sort of a tawdry slash semi-serious novel about the Colosseum." Well, for a start it's not a novel, but a very compelling historical over-view. And "tawdry"? If he means in the sense "cheap, showy, of poor quality" then absolutely not. But arguably it is somewhat sensational. Mannix had a gift for choosing utterly compelling, and often gruesome, subjects and writing books about them which you can't put down.

Besides the Roman games he also wrote historical accounts of torture, the Hellfire Club, Aleister Crowley... and the slave trade. Which brings us to the book at hand. Following on rather neatly from last week's post about that slavery malarkey (it's a pure coincidence, I swear guv) Black Cargoes is subtitled 'A History of the Atlantic Slave Trade.' It is co-written with Malcolm Cowley, but I'm not really doing him a disservice by discussing it as Mannix's book. In the introduction Cowley says "This is Daniel Mannix's book, based on his researches in London and East Africa. My own contribution was chiefly editorial." Cowley also wrote three of the book's twelve chapters.

Besides the Roman games he also wrote historical accounts of torture, the Hellfire Club, Aleister Crowley... and the slave trade. Which brings us to the book at hand. Following on rather neatly from last week's post about that slavery malarkey (it's a pure coincidence, I swear guv) Black Cargoes is subtitled 'A History of the Atlantic Slave Trade.' It is co-written with Malcolm Cowley, but I'm not really doing him a disservice by discussing it as Mannix's book. In the introduction Cowley says "This is Daniel Mannix's book, based on his researches in London and East Africa. My own contribution was chiefly editorial." Cowley also wrote three of the book's twelve chapters.In common with many of Mannix's other works, Black Cargoes is an intelligent and informative catalogue of horrors. If you want to learn about the slave trade I doubt there's a better or more readable book on the subject (despite it being published half a century ago).

Among the fascinating facts that I gleaned from it: the guinea coin, which was worth slightly more than the pound, got its name because it was made from exceptionally high quality gold from Guinea on the slave coast of Africa. The term "piccaninny" for a black child comes from the Spanish word "pequeño", meaning small.

The infamous "middle passage" which referred to the hellish sea journey from Africa to the West Indies, on which so many slaves died, is so called because it was the mid-stage of a triangular trade which ran from Europe to Africa (you buy the slaves, swindling the seller as much as you can), Africa to the New World (you trade your surviving slaves for goods like sugar), and then from the New World back to Europe (you cash in and buy a big house in Liverpool).

The infamous "middle passage" which referred to the hellish sea journey from Africa to the West Indies, on which so many slaves died, is so called because it was the mid-stage of a triangular trade which ran from Europe to Africa (you buy the slaves, swindling the seller as much as you can), Africa to the New World (you trade your surviving slaves for goods like sugar), and then from the New World back to Europe (you cash in and buy a big house in Liverpool). And, lastly, Wall Street is named after the wall which was put up to keep the slaves captive. The shrewd early American settlers soon discovered that the native American 'Indians' made lousy slaves — "either they proved intractable or they simply died." Indeed the Massachusetts Legislature complained that they were "of a malicious, surly and revengeful spirit; rude and insolent in their behaviour and very ungovernable." Good for the Indians.

The solution found by the canny Yankee traders? Sell off their ungovernable Indians in the West Indies before the word got out, and exchange them for more useful African slaves. Ah, business... Isn't it wonderful?

Daniel Mannix is rather frowned upon in serious circles because, I suspect, he writes highly readable ("enjoyable" isn't quite the right word) studies of the darker side of human nature, and explores some of the most disturbing episodes in our history. Such subject matter shouldn't be fun to read about. But Mannix comes close to making it so. Which makes for guilty readers... who can't put his books down.

Daniel Mannix is rather frowned upon in serious circles because, I suspect, he writes highly readable ("enjoyable" isn't quite the right word) studies of the darker side of human nature, and explores some of the most disturbing episodes in our history. Such subject matter shouldn't be fun to read about. But Mannix comes close to making it so. Which makes for guilty readers... who can't put his books down.Incidentally, I can't help wondering if David Franzoni wasn't also acquainted with this book by Mannix. After all, Chapter 10 of Black Cargoes contains a detailed discussion of the Amistad slave mutiny of 1839. And what was Franzoni's breakthrough script? You guessed it, Amistad for Steven Spielberg.

Perhaps we shouldn't throw words like "tawdry" around when discussing such a valuable and rewarding writer as Daniel P. Mannix.

(Image credits: Most of the covers are taken from Amazon UK, except for this one from Amazon USA. Click on the links and buy a copy.)

Published on February 02, 2014 00:25