Roland Clarke's Blog, page 59

April 17, 2015

O is for Ontario

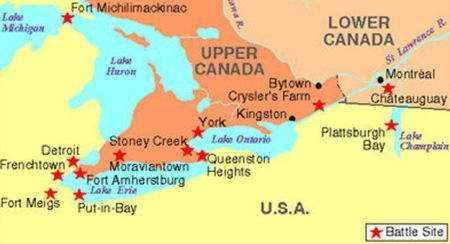

Lake Ontario and the area that became Ontario was a key battleground during the War of 1812. Upper Canada, the predecessor of modern Ontario, was created in 1791 by the division of the old colony of Quebec into Lower Canada in the east and Upper Canada in the west. A wilderness society settled largely by Loyalists and land-hungry farmers moving north from the United States, Upper Canada endured war with America, an armed rebellion, and half a century of economic and political growing pains until it was merged again with its French-speaking counterpart into the Province of Canada.

Upper Canada – The Canadian Encyclopedia

During the War there were three theatres, but varying in significance as well as the fierceness of the encounters.

Detroit Frontier

Niagara Frontier and York

Kingston and the St. Lawrence

The most significant ones on land were: Detroit Frontier – the Battle of Fort Michilimackinac (see A is for Anishinaabe); and on the Niagara Frontier – Queenston Heights fought on October 13, 1812 on the Niagara Escarpment (Q will be for Queenston – but see also B is for Brock), and most notably the Battle of York fought on April 27, 1813, in York (present-day Toronto), the capital of the province of Upper Canada (Y will be for York).

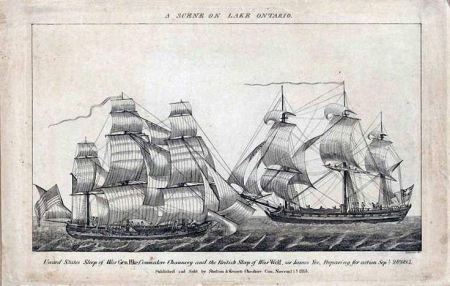

A scene on Lake Ontario – United States sloop of war Gen. Pike, Commodore Chauncey, and the British sloop of war Wolfe, Sir James Yeo, preparing for action, September 28, 1813. Published and sold by Shelton & Kennet, Cheshire, Con. November 1st 1813

There were also engagements on Lake Ontario, a prolonged naval contest for control of the lake during the War. Few actions were fought, none of which had decisive results, and the contest essentially became a naval building race, sometimes referred to sarcastically as the “Battle of the Carpenters”. Both sides (especially the British) renamed, re-rigged and re-armed their ships several times during the war. Both sides also possessed several unarmed schooners or other small vessels for use as transports or tenders.

Because neither side had been prepared to risk everything in a decisive attack on the enemy fleet or naval base, the result of all the construction effort on Lake Ontario was an expensive draw. The great demands for men and materials made by both squadrons adversely affected other parts of the war effort in the region.

Blockhouse and Battery in Old Fort, Toronto, 1812, [ca. 1921] C. W. Jefferys Pen and ink drawing on paper 29.2 cm x 36.8 cm (11.5″ x 14.5″) Government of Ontario Art Collection, 621228

During the war, Upper Canada, whose inhabitants were predominantly American in origin, was invaded and partly occupied. American forces were repulsed by British regulars assisted by Canadian militia. The war strengthened the British link, rendered loyalism a hallowed creed, fashioned martyr-heroes such as Sir Isaac Brock and Tecumseh, and appeared to legitimize the political status quo.The war ended Upper Canada’s isolation. American immigration was formally halted, but Upper Canada received an increased number of British newcomers — some with capital to spend.

Further Information

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upper_Canada

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/upper-canada/

http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/1812/index.aspx

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Engagements_on_Lake_Ontario

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS

A is for Anishinaabe ~ B is for Brock ~ C is for Coloured Corps ~ D is for Detroit ~ E is for Erie ~ F is for First Nations ~ G is for Ghent ~ H is for Harrison ~ I is for Impressment ~ J is for Jackson ~ K is for Key ~ L is for Lundy’s ~ M is for for Madison ~ N is for New Orleans

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 16, 2015

N is for New Orleans

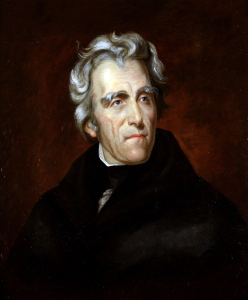

The Battle of New Orleans was a series of engagements fought from December 24, 1814 through January 8, 1815 and was the final major battle of the War of 1812. American combatants, commanded by Major General Andrew Jackson, prevented an invading British Army, commanded by General Edward Pakenham, and Royal Navy, commanded by Admiral Alexander Cochrane, from seizing New Orleans as a strategic tool to end the war. New Orleans was a vital seaport considered the gateway to the United States’ newly purchased territory in the West. If it could seize the Crescent City, the British Empire would gain dominion over the Mississippi River and hold the trade of the entire American South under its thumb.

Americans believed that a vastly powerful British fleet and army had sailed for New Orleans (Jackson himself thought 25,000 troops were coming), and most expected the worst. The victory, leading a motley assortment of militia fighters, frontiersmen, slaves, Indians and even pirates came after weathering a frontal assault by a superior British force, and inflicting devastating casualties along the way.

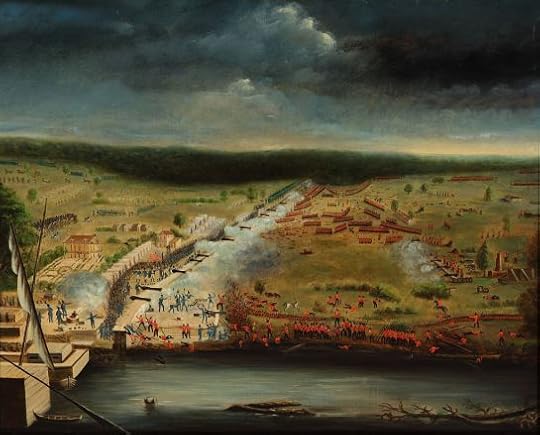

1815 painting of the battle by participant Jean Hyacinthe de Laclotte of the Louisiana Militia based on his memories and sketches made at the site.

New Orleans boosted the reputation of Andrew Jackson and helped to propel him to the White House. The anniversary of the battle was celebrated as a national holiday for many years, and continues to be commemorated in south Louisiana.

The Treaty of Ghent was signed on December 24, 1814 (but was not ratified by the US Government until February 1815), and hostilities would continue in Louisiana until January 18 when all of the British forces had retreated, finally putting an end to the Battle of New Orleans

From December 25, 1814, to January 26, 1815, British casualties during the Louisiana Campaign, apart from the assault on January 8, were 49 killed, 87 wounded and 4 missing. Thus, British casualties for the entire campaign totalled 2,459: 386 killed, 1,521 wounded, and 552 missing. American casualties for the entire campaign totalled 333: 55 killed, 185 wounded, and 93 missing.

Further Information:

http://www.history.com/topics/battle-of-new-orleans

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_New_Orleans

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS

A is for Anishinaabe ~ B is for Brock ~ C is for Coloured Corps ~ D is for Detroit ~ E is for Erie ~ F is for First Nations ~ G is for Ghent ~ H is for Harrison ~ I is for Impressment ~ J is for Jackson ~ K is for Key ~ L is for Lundy’s ~ M for Madison

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 15, 2015

M is for Madison

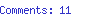

James Madison, Jr. (March 16, 1751 – June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, political theorist, and the fourth President of the United States (1809–17). He is hailed as the “Father of the Constitution” for being instrumental in the drafting of the U.S. Constitution and as the key champion and author of the Bill of Rights. He was President throughout the War of 1812, and served as a politician much of his adult life.

No war monger, Madison found himself pressured into declaring war and was grateful when the chance for peace arose. However, Madison’s chief goal was to defeat and occupy part of Canada, which many in the US believed would eventually be absorbed into the United States anyway as the nation grew. By defeating British forces in North America, Madison hoped to end British abuses of US citizens and trade for good.

Despite having declared war and begun military operations against their enemy, Madison found his nation initially unprepared for serious or sustained campaigns. Congress had not properly funded or prepared an army, and a number of the states did not support what was referred to as “Mr. Madison’s War” and would not allow their militias to join the campaign. Despite these setbacks, American forces attempted to fight off and attack British forces. The U.S. met defeat much of the time both on land and at sea, but its well-built ships proved to be formidable foes.

James Madison, 4th president of the United States (courtesy White House Historical Association)

But that did not stop the British from pressing their land forces closer and closer to Washington. While Madison was gone from the capital, the British carried out a daring and terrible raid and ransacked the White House and the capital building, setting fires and raising hell as payback for the sacking of York [Toronto], which the Americans, after defeating the British, had vandalized and set ablaze 27 April 1813.

But British victories were soon repelled, and with control of the lakes and successful operations in Baltimore and later New Orleans, Madison’s war efforts were now finding the public stoked and supportive. But it was too late. By 1814, both American and British leaders were tired of the conflict, and, finding themselves in mutual agreement, signed the Treaty of Ghent in 1814. The Treaty’s resolutions essentially pretended the war had never happened. Territory and prisoners were returned. Old boundaries were re-established. It was a war for which peace became the only of sign of victory.

Though the war was mismanaged, there were some key victories that emboldened the Americans. Once blamed for the errors in the war, Madison was eventually hailed for its triumphs.

Madison survived this first unpopular war in American history. No lover of military affairs, he quickly turned his attention to matters of economics, law and trade, but now keenly knew the value of a well-armed and prepared army and navy.

Further Information

http://www.history.com/topics/us-presidents/james-madison

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Madison

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng/Topic/5

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS

A is for Anishinaabe ~ B is for Brock ~ C is for Coloured Corps ~ D is for Detroit ~ E is for Erie ~ F is for First Nations ~ G is for Ghent ~ H is for Harrison ~ I is for Impressment ~ J is for Jackson ~ K is for Key ~ L is for Lundy’s

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 14, 2015

L is for Lundy’s Lane

The Battle of Lundy’s Lane (also known as the Battle of Niagara Falls, the fiercest and bloodiest land action during the War of 1812, took place on 25 July 1814, in present-day Niagara Falls, Ontario. It was one of the deadliest battles ever fought in Canada.

The battle took place around the junction of Portage Road and Lundy’s Lane, in what is now the city of Niagara Falls. At the height of the 5-hour-long battle, much of which was fought after dark, about 3,000 British and Canadian soldiers faced some 2,800 American invaders. Casualties were heavy, with both sides losing more than 850 men killed, wounded or missing in action. Tactically, the battle of Lundy’s Lane can be considered to have been a draw, since neither side had been defeated. Strategically, however, it was a British victory since the battle ended the Americans’ Niagara offensive; by early November 1814, they had retreated to the New York side of the Niagara River.

The Battle of Lundy’s Lane, [ca. 1921]

C. W. Jefferys

Pen and Ink Drawing

Government of Ontario Art Collection, 621234

Winfield Scott during War of 1812 – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In 1895, the federal government erected a 12-metre-high granite memorial monument in the Drummond Hill Cemetery, the centre of the battleground. Various plaques and smaller memorials are also on the site. The battleground received formal designation as a national Historic Site from the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada in 1937.

Further Information:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng/Topic/117

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Lundy%27s_Lane

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS

A is for Anishinaabe ~ B is for Brock ~ C is for Coloured Corps ~ D is for Detroit ~ E is for Erie ~ F is for First Nations ~ G is for Ghent ~ H is for Harrison ~ I is for Impressment ~ J is for Jackson ~ K is for Key

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 13, 2015

K is for Key

Francis Scott Key (August 1, 1779 – January 11, 1843) was an American lawyer, author, and amateur poet, from Georgetown, who wrote the lyrics to the United States’ national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner”.

During the War of 1812, one of Key’s friends, Dr. William Beanes, was taken prisoner by the British. Key went to Baltimore with British Prisoner Exchange Agent Colonel John Stuart Skinner, and on a British ship negotiated the release of several prisoners. Skinner, Key, and Beanes were not allowed to return to their own sloop because they had become familiar with the strength and position of the British units and with the British intent to attack Baltimore.

From aboard a British ship located about eight miles away, Key watched the bombarding of the American forces at Fort McHenry on the night of September 13–14, 1814. After a day, the British were unable to destroy the fort and gave up. Key was relieved to see the enormous American flag still flying proudly over Fort McHenry and reported this to the prisoners below deck. The 30 x 42 feet flag had been pieced together on the floor of a Baltimore brewery, and has been preserved in the Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC.

This 1873 image is the first known photograph taken of the Star-Spangled Banner. Taken at the Boston Navy Yard on June 21st, 1873. (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.)

Back in Baltimore and inspired, Key wrote a poem about his experience, “Defence of Fort M’Henry”. The poem was printed in newspapers and eventually set to the music of a popular English drinking tune called “To Anacreon in Heaven” by composer John Stafford Smith. It was a popular tune Key had already used as a setting for his 1805 song “When the Warrior Returns,” celebrating U.S. heroes of the First Barbary War. (Key used the “star spangled” flag imagery in the earlier song.)

People began referring to the song as “The Star-Spangled Banner” and it became increasingly popular, competing with “Hail, Colombia” (1796) as the de facto national anthem by the Mexican-American War and American Civil War. In 1916 President Woodrow Wilson announced that it should be played at all official events. It was adopted as the national anthem on March 3, 1931.

“Francis Scott Key by Joseph Wood c1825″ by attributed to Joseph Wood (1778-1830) – . Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons –

Francis Scott Key died of pleurisy on January 11, 1843. Today, the flag that flew over Fort McHenry in 1914 is housed at the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

http://www.si.edu/Encyclopedia_SI/nmah/starflag.htm

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-story-behind-the-star-spangled-banner-149220970/

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/key-pens-star-spangled-banner

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Scott_Key

http://amhistory.si.edu/starspangledbanner/the-war-of-1812.aspx

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS:

A is for Anishinaabe ~ B is for Brock ~ C is for Coloured Corps ~ D is for Detroit ~ E is for Erie ~ F is for First Nations ~ G is for Ghent ~ H is for Harrison ~ I is for Impressment ~ J is for Jackson

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 11, 2015

J is for Jackson

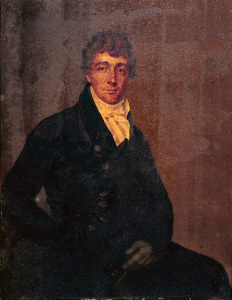

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) gained national fame through his role in the War of 1812 and became the seventh President of the United States (1829–1837).

He was born near the end of the colonial era, somewhere near the then-unmarked border between North and South Carolina, into a recently immigrated Scots-Irish farming family of relatively modest means. During the American Revolutionary War Jackson’s family supported the revolutionary cause, and he acted as a courier. He later became a lawyer, and in 1796 he helped found the state of Tennessee. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, and then to the U.S. Senate. In 1801, Jackson was appointed colonel in the Tennessee militia, which became his political as well as military base.

As a major general in the War of 1812, Jackson commanded U.S. forces in a five-month campaign against the Creek Indians, allies of the British. Aided by other Native American nations such as the Cherokee and Choctaw, the decisive American victory in the Battle of Tohopeka (or Horseshoe Bend) in Alabama in mid-1814 ended the campaign, Jackson then led American forces to victory over the British in the Battle of New Orleans (January 1815). The win, which occurred after the War officially ended, but before news of the Treaty of Ghent had reached Washington, elevated Jackson to the status of national war hero.

Jackson in 1824, painting by Thomas Sully

Nominated for president in 1824, Jackson narrowly lost to John Quincy Adams. Jackson’s supporters then founded what became the Democratic Party. Nominated again in 1828, Jackson crusaded against Adams and the “corrupt bargain” between Adams and Henry Clay that he said cost him the 1824 election. Building on his base in the West and new support from Virginia and New York, he won by a landslide.

For some, his legacy is tarnished by his role in the forced relocation of Native American tribes living east of the Mississippi. Despite the assistance of nations such as the Cherokee and Choctaw in the Creek Campaign, as President he supported, signed, and enforced the 1830 Indian Removal Act, which relocated a number of native tribes to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Jackson

http://www.history.com/topics/us-presidents/andrew-jackson

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS:

A is for Anishinaabe ~ B is for Brock ~ C is for Coloured Corps ~ D is for Detroit ~ E is for Erie ~ F is for First Nations ~ G is for Ghent ~ H is for Harrison ~ I is for Impressment

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 10, 2015

The Role of the Editor: Guest Post by Sue Barnard

Fascinating and insightful interview with Sue Barnard, the editor that I’ve just used for “Storms Compass”.

Originally posted on Vanessa Couchman, author:

Originally posted on Vanessa Couchman, author:

Author and editor, Sue Barnard

Author and editor, Sue Barnard

I’m delighted to welcome my friend and fellow Crooked Cat author, Sue Barnard, to the chaise longue this week. Not only is Sue an author in her own right, but she’s also an editor. More precisely, she is my editor. And a cracking job she did, too, of The House at Zaronza. She saved me from many a howler and smartened up my prose no end.

View original 1,055 more words

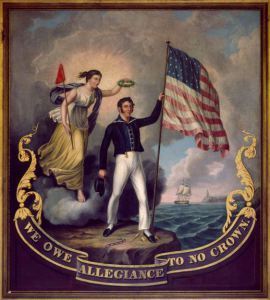

I is for Impressment

Impressment, or removing seamen from U.S. merchant vessels and forcing them to serve on behalf of the British, was one of the main causes of the War of 1812, according to most sources. During the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15), the Royal Navy expanded to 175 ships of the line and 600 ships overall, requiring 140,000 sailors to man. While the Royal Navy could man its ships with volunteers in peacetime, it competed in wartime with merchant shipping and privateers for a small pool of experienced sailors and turned to impressment when it could not operate ships with volunteers alone. Britain did not recognize the right of a British subject to relinquish his status as a British subject, emigrate and transfer his national allegiance as a naturalized citizen to any other country. Thus while the United States recognized British-born sailors on American ships as Americans, Britain did not.

The United States believed that British deserters had a right to become United States citizens. Britain did not recognize naturalized United States citizenship, so in addition to recovering deserters, it considered United States citizens born British liable for impressment. Aggravating the situation was the widespread use of forged identity or protection papers by sailors. This made it difficult for the Royal Navy to distinguish Americans from non-Americans and led it to impress some Americans who had never been British. (Some gained freedom on appeal.)] American anger at impressment grew when British frigates were stationed just outside U.S. harbours in view of U.S. shores and searched ships for contraband and impressed men while in U.S. territorial waters. “Free trade and sailors’ rights” was a rallying cry for the United States throughout the conflict.

We Owe Allegiance to No Crown, by John Archibald Woodside. c. 1814. Photograph copyright Nicholas S. West. Photography by Erik Arnesen.

Between 1803 and 1812, approximately 5,000-9,000 American sailors were forced into the Royal Navy with as many as three-quarters being legitimate American citizens. Though the American government repeatedly protested the practice, British Foreign Secretary Lord Harrowby contemptuously wrote in 1804, “The pretention advanced by Mr. [Secretary of State James] Madison that the American flag should protect every individual on board of a merchant ship is too extravagant to require any serious refutation.”

The Royal Navy also used impressment extensively in British North America from 1775 to 1815. Its press gangs sparked resistance, riots, and political turmoil in seaports such as Halifax, St John’s, and Quebec City. In 1805 this led to a prohibition on impressment on shore for much of the Napoleonic Wars. The protest came from a wide swath of the urban community, including elites, rather than just the vulnerable sailors, and had a lasting negative impact on civil–naval relations in what became Canada. The local communities did not encourage their young men to volunteer for the Royal Navy.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impressment

http://www.marinersmuseum.org/sites/micro/usnavy/08/08a.htm

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS:

A is for Anishinaabe ~ B is for Brock ~ C is for Coloured Corps ~ D is for Detroit ~ E is for Erie ~ F is for First Nations ~ G is for Ghent ~ H is for Harrison

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 9, 2015

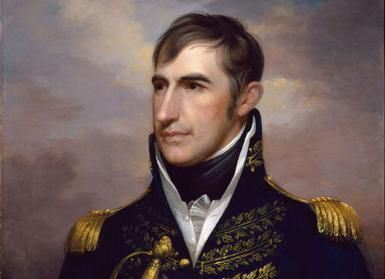

H is for Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773 – April 4, 1841) originally gained national fame for leading U.S. forces against American Indians at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811, where Harrison’s forces fought off followers of the powerful Shawnee leader Tecumseh (1768-1813). Although the U.S. suffered significant troop losses and the battle’s outcome was inconclusive and did not end Indian resistance, Harrison ultimately emerged with his reputation as an Indian fighter intact, and earned the nickname “Tippecanoe” (or “Old Tippecanoe”). He capitalized on this image during his 1840 presidential campaign, using the slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler too,”

After a dozen years as governor of the Indiana Territory, Harrison rejoined the Army when the War of 1812 began. He was made a brigadier general and placed in charge of the Army of the Northwest, on September 17, 1812. Promoted to major general, Harrison worked diligently to transform his army from an untrained mob into a disciplined fighting force. Unable to go on the offensive while British ships controlled Lake Erie, Harrison worked to defend American settlements.

In late September 1813, after the American victory at the Battle of Lake Erie, Harrison moved to the attack. Ferried to Detroit by Master Commandant Oliver H. Perry’s victorious squadron, Harrison set off in pursuit British and Native American forces under Major General Henry Proctor and Tecumseh. Catching them on October 5, Harrison won a key victory at the Battle of the Thames which saw Tecumseh killed, the war on the Lake Erie front effectively ended, and the dissolution of the Indian coalition.

William Henry Harrison ~ National Portrait Gallery, Washington DC. ~ Photograph Source: Public Domain

Harrison told US Secretary of War John Armstrong, Jr. that all his casualties were a result of the native warriors, not the British regulars. Unable to sustain or build on his victory, Harrison and his men headed for Detroit, the Americans now in firm control of the North West frontier. Procter would continue to command those who had fought with him, but his poor handling of the retreat and battle would be his undoing. Though a skilled and popular commander, Harrison resigned the following summer after disagreements with Secretary of War John Armstrong.

After the war, Harrison moved to Ohio, where he was elected to the United States House of Representatives. In 1824 the state legislature elected him to the U.S. Senate. He served a truncated term after being appointed as Minister Plenipotentiary to Colombia in May 1828. In Colombia, he spoke with Simón Bolívar urging his nation to adopt American-style democracy.

Harrison was elected as the ninth President of the United States in 1840, and died on his 32nd day in office of pneumonia in April 1841- the first president to die in office and serving the shortest tenure in United States presidential history. He was the last President born as a British subject. His death sparked a brief constitutional crisis, but its resolution settled many questions about presidential succession left unanswered by the Constitution until the passage of the 25th Amendment in 1967. He was the grandfather of Benjamin Harrison, who was the 23rd President from 1889 to 1893.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Henry_Harrison

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng/Topic/29

http://www.history.com/topics/us-presidents/william-henry-harrison

http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/1800sarmybiographies/p/whharrison.htm

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS:

A is for Anishinaabe ~ B is for Brock ~ C is for Coloured Corps ~ D is for Detroit ~ E is for Erie ~ F is for First Nations ~ G is for Ghent

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

April 8, 2015

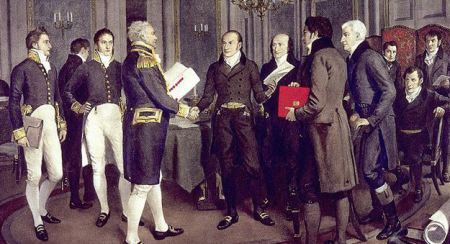

G is for Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent), signed on December 24, 1814, was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain. The treaty restored relations between the two nations to status quo before the war — that is, it restored the borders of the two countries to the line before the war started in June 1812. The Treaty was approved by the Prince Regent (the future King George IV). It took a month for news of the peace treaty to reach the United States. American forces under Andrew Jackson won the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815. The Treaty of Ghent was not in effect until it was ratified by the U.S. Senate unanimously on February 18, 1815.

The peace discussions began in the neutral city of Ghent in August 1814. As the peace talks opened American diplomats decided not to present President Madison’s demands for the end of impressment and suggestion that Britain turn Canada over to the U.S. They let the British open with their demands, chief of which was the creation of an Indian barrier state in the American Northwest Territory (the area from Ohio to Wisconsin). It was understood the British would sponsor this Indian state. The British strategy for decades had been to create a buffer state to block American expansion. The Americans refused to consider a buffer state and the proposal was dropped. Article IX of the treaty included provisions to restore to Natives “all possessions, rights and privileges which they may have enjoyed, or been entitled to in 1811″, but the provisions were unenforceable and in any case Britain ended its practice of supporting or encouraging tribes living in American territory.

In his 1914 painting A Hundred Years Peace, artist Amedee Forestier illustrates the signing of the Treaty of Ghent between Great Britain and the US, 24 December 1814 (courtesy Library and Archives Canada/C-115678).

After months of negotiations, against the background of changing military victories, defeats and losses, the parties finally realized that their nations wanted peace and there was no real reason to continue the war. Now each side was tired of the war. Export trade was all but paralyzed and after Napoleon fell in 1814 France was no longer an enemy of Britain, so the Royal Navy no longer needed to stop American shipments to France, and it no longer needed more seamen so impressment was not an issue.

Consequently, none of the issues that had caused the war or that had become critical to the conflict were included in the treaty.

The treaty thus made no significant changes to the pre-war boundaries, although the U.S. did gain territory from Spain. Britain promised to return the freed black slaves that they had taken. In actuality, a few years later Britain instead paid the United States $1,204,960 for them. Both nations also promised to work towards an ending of the international slave trade.

Canadian author, Pierre Berton wrote of the treaty, “It was as if no war had been fought, or to put it more bluntly, as if the war that was fought was fought for no good reason. For nothing has changed; everything is as it was in the beginning save for the graves of those who, it now appears, have fought for a trifle:…Lake Erie and Fort McHenry will go into the American history books, Queenston Heights and Crysler’s Farm into the Canadian, but without the gore, the stench, the disease, the terror, the conniving, and the imbecilities that march with every army.”

The Peace Bridge between Buffalo, New York, and Fort Erie, Ontario, opened in 1927 to commemorate more than a century of peace between the United States and Canada.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Ghent

http://www.history.com/topics/treaty-of-ghent

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng/Topic/55

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS:

A is for Anishinaabe ~ B is for Brock ~ C is for Coloured Corps ~ D is for Detroit

E is for Erie ~ F is for First Nations

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

![Blockhouse and Battery in Old Fort, Toronto, 1812, [ca. 1921] C. W. Jefferys Pen and ink drawing on paper 29.2 cm x 36.8 cm (11.5](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1429359286i/14576338.jpg)

![A2Z-BADGE-000 [2015] - Life is Good](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1428092352i/14364582.jpg)

![The Battle of Lundy's Lane, [ca. 1921] C. W. Jefferys Pen and Ink Drawing Government of Ontario Art Collection, 621234](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1429359286i/14576350.jpg)