Roland Clarke's Blog, page 58

April 29, 2015

Y is for York

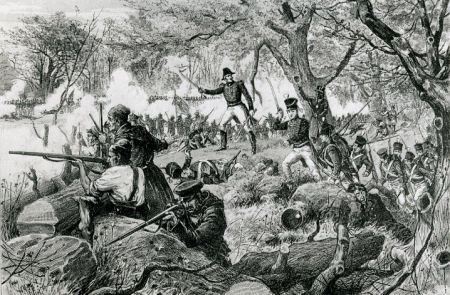

The Battle of York was fought during the War of 1812, on April 27, 1813, in York (present-day Toronto), the capital of the province of Upper Canada (present-day Ontario), between United States forces and the British defenders of York. U.S. forces under Brigadier General Zebulon Pike were able to defeat the defenders of York, comprising a British-led force under the command of Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe, combined with a small group of Ojibwe allies.

An American force of approximately 1700 men, supported by a naval flotilla of 16 American ships under Commodore Isaac Chauncey, landed on the lake shore to the west, suppressed the small group of warriors defending the shore, while knocking out the town’s meagre batteries. With the fort poorly defended by an undersized garrison of 700 soldiers and backed by an unenthusiastic (indeed, almost wholly absent) militia, the Americans captured the fort, town and dockyard. To circumvent looting, Sheaffe had ordered all valuables to be destroyed before retreating. A ship, then under construction, was burned, the naval stores were destroyed, and the fort’s magazine was set on fire. Two local militia officers were left behind to negotiate the terms of surrender.

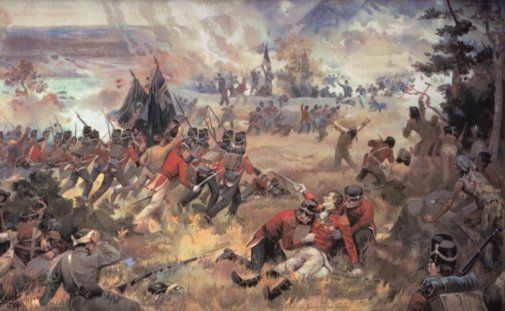

The death of American General Pike at the Battle of York, 27 April 1813 (courtesy Canadian Military History Gateway, Government of Canada).

The Americans themselves suffered heavy casualties, including Zebulon Pike who was leading the troops, when the burning magazine blew up with devastating results. The American forces subsequently carried out several acts of arson and looting in the town themselves, before withdrawing. Over the course of their six-day occupation, American troops sacked any home they found deserted, along with several businesses and public buildings.

Though the Americans won a clear victory, it did not have decisive strategic results as York was a less important objective in military terms than Kingston, where the British armed vessels on Lake Ontario were based. The loss of naval and military stores was crippling, particularly for the British efforts on Lake Erie.

Fort York was sacked twice by the Americans during the War of 1812 (courtesy Library and Archives Canada/C-40091).

The capture of the capital was an embarrassment for the British, exposing fatal inadequacies in their defences. Indeed, so poorly defended was the town that Chauncey returned in July, landing unopposed to burn several public buildings and boats, destroy a lumber yard, and make off with their supplies. The British attack on Washington in August 1814 was seen as just retaliation.

Further Information:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_York

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng/Topic/47

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS

Details on my 2015 A to Z theme and a linked list of posts can be found on my A to Z Challenge page, which also has a linked list of my 2014 posts.

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 28, 2015

X is for X-mark signature and literacy

So some of those that fought in the War of 1812, the X-mark signature would have been an easier option than signing their names when required – and a mere description of their appearance didn’t suffice to identify them. Literacy rates in North America ranged from 60% to 90%, but more in the towns. In rural and frontier areas this was much lower, and the figures excluded slaves that were not allowed to read and write, plus many First Nations had a more oral tradition. Great Britain had the highest literacy rate in Europe.

However, there is a misconception that people used X’s because they were illiterate. Not so! Literate people also used the X mark on legal documents until about 1860. (And illiterate people often knew how to draw a signature even if they couldn’t read.) What mattered was not the size of your signature but the guarantee by the notary that you were who you said you were. Until 150 years ago, most legal forms were copied by hand by a clerk or scrivener; the notary or lawyer (or the clerk) would then carefully write in the dates and names. All this was done with a quill or steel dip pen, which were difficult for the average person to handle.

For some of the participants in the War of 1812 the conflict was the defining moment of their lives, and they were well aware of it. A number of young soldiers penned brief diaries and journals that show how the war began for them as an adventure, but ended in many cases with injury, imprisonment and grief. For women, too, the war was a trial, a test of their fortitude and resourcefulness, but it was also a window onto a wider world. Their journals in turn have become our window onto a war that took place two centuries ago.

Paul Jennings

Although substantial first-person records of the war comes primarily from the educated classes, exceptions are the memoirs written by the British foot solider, Shadrach Byfield, and the American militiaman, William Atherton. Their experiences encompass the full experience of war – battles, injuries, imprisonment and aftermath. And don’t forget James Madison’s personal slave, the fifteen-year-old boy Paul Jennings, who was an eyewitness and published his memoir in 1865, considered the first from the White House.

Teyoninhokovrawen aka John Norton

Most of the journals were written by men, such as law student John Beverly Robinson, Mohawk chief John Norton, and well-educated John Pendleton Kennedy. But several diaries and letter collections from women survive, notably of Mrs. Josiah (Lydia) B. Bacon, wife of the U.S. Lieutenant and Quartermaster Josiah Bacon. The more famous quotes are from first lady Dolley Madison, whose letters to her sister, Lucy, are the basis for her well-known account of the burning of Washington. Anne Prevost – Anne was a daughter of General Sir George Prevost, Governor General of the British forces in Canada. At seventeen she was a faithful journal keeper, and she made almost daily entries during the time her father was prosecuting the war.

Anne Prevost

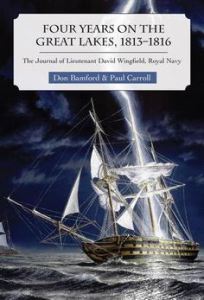

The fictional memoirs in my novel “Seeking A Knife” are loosely based on the journal of Lieutenant David Wingfield, Royal Navy.

Further Information:

http://umbrigade.tripod.com/articles/women.html

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/personal-journals-war/

http://colonialquills.blogspot.co.uk/2011/06/literacy-in-colonial-america.html

https://wardsville.wordpress.com/2010/03/10/the-roles-women-played-in-the-war-of-1812/

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS

Details on my 2015 A to Z theme and a linked list of posts can be found on my A to Z Challenge page, which also has a linked list of my 2014 posts.

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 27, 2015

W is for White House, Washington

Throughout the history of the United States, the United Kingdom is the only country to have ever burned the White House or Washington, D.C., and this was the only time since the American Revolutionary War that a foreign power captured and occupied the United States capital.

In the final summer of the War of 1812, the British presence in the Chesapeake region was strengthened by the large numbers of troops arriving after the Napoleonic wars in Europe ended. This diverted the American forces from the frontiers of Upper and Lower Canada, but despite Britain’s strong naval presence in the region, very little was done to protect the small town of Washington. The American secretary of war, John Armstrong, was convinced that Baltimore was the target, and he was half-right as one British attack came there.

The taking of the city of Washington, wood engraving by G. Thompson, c. 1814 (courtesy Library of Congress/ LC-USZC4-4555)

However, British forces led by Major General Robert Ross raided the Chesapeake Bay and after defeating the hastily arrayed Americans at the Battle of Bladensburg, the British occupied Washington City on August 24, 1814 and set fire to many public buildings, including the White House (known as the presidential mansion at the time), and the Capitol, as well as other U.S Government facilities including the treasury building, and the navy yard. This action was taken as retaliation against the American destruction of private property in violation of the laws of war, including the Burning of York [present day Toronto] on April 27, 1813, and the Raid on Port Dover.

President James Madison and members of the military and his government fled the city in the wake of the British attack. The Americans’ quick retreat later earned the nickname the “Bladensburg races.”

First Lady Dolley Madison

Before leaving, later, the First Lady Dolley Madison and the staff managed to save many of the cabinet records and White House treasures. Nevertheless, the extent of the damages was extreme. James Madison’s personal slave, the fifteen-year-old boy Paul Jennings, was an eyewitness and published his memoir in 1865, considered the first from the White House..

Most contemporary American observers condemned the destruction of the public buildings as needless vandalism. Many of the British public were shocked by the burning of the Capitol and other buildings at Washington; such actions were denounced by most leaders of continental Europe. However, the majority of British opinion believed that the burnings were justified following the damage that United States forces had done with its incursions into Canada.

Further Information:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burning_of_Washington

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng/Topic/52

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dolley_Madison

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Jennings_(slave)

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS

Details on my 2015 A to Z theme and a linked list of posts can be found on my A to Z Challenge page, which also has a linked list of my 2014 posts.

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 25, 2015

V is for Voltigeurs

The Canadian Voltigeurs were a light infantry unit, raised in Lower Canada (the present-day Province of Quebec), that fought in the War of 1812. Most colonial forces raised to fight the Americans were English, Irish and Scottish in origin. But French Canada also served, and distinctly.

On 15 April 1812 Sir George Prevost, the Governor General of Canada, authorised the enlistment of a Provincial Corps of Light Infantry under Lieutenant Colonel Charles de Salaberry. The unit, known as the Voltigeurs de Quebec was officially part of the militia, and its enlisted personnel were subject to the Militia laws and ordinances, but for all practical purposes, it was administered on the same basis as the fencible units, also raised in Canada as regular soldiers but liable for service in North America only.

De Salaberry selected members of the leading families of Lower Canada as officers, many related to de Salaberry, though all were treated to his fierce discipline and high standards. Commissions were not confirmed until they had recruited their quota of volunteers. The Voltigeurs were full-time professional soldiers, and had a distinctly “Canadian” pedigree.

Almost all the soldiers and most of the officers were French-speaking, which led to the unit being widely known as the Voltigeurs, a French word meaning “vaulter” or “leaper”, and given to elite light infantry units in the French Army. However, all formal orders on the parade ground or in battle were given in English.

The new unit mustered at Chambly. Quebec. It had eight companies of light infantry, and some Mohawk warriors were attached. Two further companies were recruited from militia of the Eastern Townships of the Montreal district, and officially listed as the ninth and tenth companies, but they formed a separate corps, the Frontier Light Infantry, throughout the war.

Canadian voltigeurs prepare to defend Lacolle Mills during the War of 1812 (painting by G.A. Embleton, courtesy Parks Canada)

Some of the Voltigeurs were in action at the Battle of Lacolle Mills (1812), and early in 1813, three companies were detached under the unit’s second-in-command, Major Frederick Heriot, and moved up the Saint Lawrence River to form part of the garrison of Kingston, the main British base on Lake Ontario. On 29 May, two of these companies took part in the Battle of Sackett’s Harbor. Later in the year, the detachment moved to Fort Wellington at Prescott, and subsequently played an important part in the Battle of Crysler’s Farm.

The main body of the unit formed part of a light corps stationed to the south of Montreal, which was commanded by de Salaberry in person. Learning that an American division under Major General Wade Hampton was advancing from New York State, de Salaberry’s force entrenched themselves by the River Chateauguay. On 26 October, Hampton attacked. At the resulting Battle of the Chateauguay, Hampton was repulsed by this all-Canadian force. While primarily a series of skirmishes, the Battle of Chateauguay was a very “Canadian” victory.

Voltigeurs in action at the Battle of the Chateauguay

Early in 1814, the entire unit concentrated at Montreal, and was built back up to strength. De Salaberry had been appointed Inspecting Field Officer of Militia, and Major Heriot became the Voltigeurs’ acting Commanding Officer. The Voltigeurs were brigaded with the Frontier Light Infantry, and another militia light infantry unit, the Canadian Chasseurs. The combined light infantry force formed part of a brigade under Major General Thomas Brisbane during the Battle of Plattsburgh, where the British army retreated after its supporting naval squadron was destroyed. On the end of the war, the unit was disbanded, on 24 May, 1815.

The current Les Voltigeurs de Québec today perpetuate the history and traditions of the Canadian Voltigeurs within the Canadian Army.

Further Information:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng/Topic/17

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canadian_Voltigeurs

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS

Details on my 2015 A to Z theme and a linked list of posts can be found on my A to Z Challenge page, which also has a linked list of my 2014 posts.

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 24, 2015

U is for United States Navy

The United States Navy saw substantial action in the War of 1812, where it was victorious in eleven single-ship duels with the Royal Navy. The navy drove all significant British forces off Lake Erie and Lake Champlain and prevented them from becoming British controlled zones of conflict. The result was a major defeat for the British invasion of New York State, and the defeat of the military threat from the Indian allies of the British. Despite this, the U.S. Navy was unable to prevent the British from blockading American ports and landing troops on American soil.

Various U.S. Navy vessels played notable roles in the War, but this focuses on three of them:

USS Constellation by John W. Schmidt

USS Constellation was a 38-gun frigate, one of the “Six Original Frigates” authorized for construction by the Naval Act of 1794. She was distinguished as the first U.S. Navy vessel to put to sea and the first U.S. Navy vessel to engage and defeat an enemy vessel. Constructed in 1797, she was decommissioned in 1853. On June 22, 1813, her crew played a crucial role in the Battle of Craney Island. The American victory at Craney Island saved Norfolk and Portsmouth from being captured and pillaged by the enemy.

BOSTON (July 4, 2014) USS Constitution fires a 17-gun salute near U.S. Coast Guard Base Boston during the ship’s Independence Day underway demonstration in Boston Harbor. Constitution got underway with more than 300 guests to celebrate America’s independence. (U.S. Navy photo by Seaman Matthew R. Fairchild/Released)

USS Constitution is a wooden-hulled, three-masted heavy frigate, named by President George Washington after the Constitution of the United States of America. The boat is the world’s oldest commissioned naval vessel afloat.[Note 1] Launched in 1797, Constitution , like USS Constellation, was one of the “Six Original Frigates”. Joshua Humphreys designed the frigates to be the young Navy’s capital ships, and so Constitution and her sisters were larger and more heavily armed and built than standard frigates of the period. Constitution is most famous for her actions during the War of 1812, when she captured numerous merchant ships and defeated five British warships: HMS Guerriere, Java, Pictou, Cyane, and Levant. The battle with Guerriere earned her the nickname of “Old Ironsides” and public adoration that has repeatedly saved her from scrapping.

USS Essex capturing Alert. 13 August 1812 – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The first USS Essex participated in the Quasi-War with France, the First Barbary War, and in the War of 1812. When war was declared, the 32 gun frigate, commanded by Captain David Porter, made a successful cruise to the southward. By September, when she returned to New York, Essex had taken ten prizes, including the sloop HMS Alert. The youngest member of the Essex crew was 10-year-old midshipman David Glasgow Farragut, who would become the first admiral of the US Navy.

Essex sailed into South Atlantic waters and along the coast of Brazil until January 1813, decimating the British whaling fleet in the Pacific, and capturing thirteen British whalers. In January 1814, Essex sailed into neutral waters at Valparaíso, Chile, only to be trapped there by the British frigate, HMS Phoebe, and the sloop-of-war HMS Cherub. On 28 March 1814, in the Battle of Valparaiso, Essex, armed almost entirely with powerful, but short range carronades, resisted the superior British fighting power and longer gun range for over 2 hours. Eventually, the hopeless situation forced Porter to surrender. The captured frigate then served as HMS Essex until sold at public auction on 6 June 1837.

Patrick O’Brian adapted the story of Essex ’s attack on British whalers for his novel The Far Side of the World.

Further Information:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Navy

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Constellation_(1797)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Constitution

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Essex_(1799)

http://www.army.mil/article/98107

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS

Details on my 2015 A to Z theme and a linked list of posts can be found on my A to Z Challenge page, which also has a linked list of my 2014 posts.

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 23, 2015

T is for Tecumseh

Tecumseh (/tɛˈkʌmsə/ te-kum-sə) (March 1768 – October 5, 1813) was a Native American leader of the Shawnee and a large tribal confederacy (known as Tecumseh’s Confederacy) which opposed the United States during Tecumseh’s War and became an ally of Britain in the War of 1812.

Tecumseh grew up in Ohio during the American Revolutionary War and the Northwest Indian War, where he was constantly exposed to warfare. With Americans continuing to move west after the British ceded the Ohio Valley to the new United States in 1783, the Shawnee moved farther northwest. In 1805 Lalawethika, one of Tecumseh’s younger brothers, experienced a series of visions becoming a prominent religious leader. Taking the name Tenskwatawa, or ‘The Open Door,’ the Prophet’s message seemed to offer the Indians a religious deliverance from their problems.

Tecumseh allied his forces with the British. Painting by W.B. Turner (courtesy Metropolitan Toronto Library, J. Ross Robertson/T-16600)

Tecumseh seemed reluctant to accept his brother’s teachings until June 16, 1806, when the Prophet accurately predicted an eclipse of the sun, and Indians from throughout the Midwest flocked to the Shawnee village at Greenville, Ohio. In 1808, they settled Prophetstown in present-day Indiana. Tecumseh slowly transformed his brother’s religious following into a political movement. With a vision of establishing an independent Native American nation east of the Mississippi under British protection, Tecumseh worked to recruit additional tribes to the confederacy from the southern United States.

In November 1811, while Tecumseh was in the South attempting to recruit the Creeks into his confederacy, U.S. forces marched against Prophetstown. In the subsequent Battle of the Tippecanoe they defeated the Prophet, and burned the settlement. After returning from the South, Tecumseh tried to rebuild his shattered confederacy. When the War of 1812 broke out, Tecumseh’s confederacy allied with the British and helped in the capture of Fort Detroit, and subsequent actions in southern Michigan (Monguagon) and northern Ohio (Fort Meigs).

There is no known picture of Tecumseh but most

specialists agree that this sketch, drawn from an

eyewitness description of the man, is the closest likeness.

Library and Archives Canada (C-000319)

After the U.S. Navy took control of Lake Erie in 1813, the Native Americans and British retreated. On October 5 1813, American forces caught them at the Battle of the Thames, (also known as the Battle of Moraviantown,) and forced to retreat with the demoralized British, Tecumseh was killed. With his death (his body was never recovered), his confederation disintegrated. Tecumseh’s political leadership, oratory, humanitarianism, and personal bravery attracted the attention of friends and foes. And Tecumseh became an iconic folk hero in American, Aboriginal and Canadian history.

Further Information:

http://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/tecumseh

http://www.history.com/news/6-things-you-may-not-know-about-tecumseh

http://www.napoleon-series.org/military/Warof1812/2006/Issue2/c_abos.html

http://www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhh-dhp/pub/boo-bro/abo-aut/chapter-chapitre-03-eng.asp

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tecumseh

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS

Details on my 2015 A to Z theme and a linked list of posts can be found on my A to Z Challenge page, which also has a linked list of my 2014 posts.

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 22, 2015

S is for Secord

Laura Secord (née Ingersoll; 13 September 1775 – 17 October 1868) was a Canadian heroine of the War of 1812. Born in Massachusetts and the daughter of a Revolutionary War patriot, Laura Secord might be an unlikely Canadian icon. But on the evening of June 21, 1813, the 37-year-old wife of a Canadian Loyalist soldier and mother of five learned of secret American plans to ambush a nearby British outpost. But her husband James Secord was bedridden after being seriously wounded at the Battle of Queenston Heights. However, Laura hiked across 20 miles (32 km) out of American-occupied territory, through swamps and forests to warn the British, being helped by a group of First Nations men she encountered along the way. She reached Lieutenant James FitzGibbon in the territory that the British still controlled. The information helped the British and their Mohawk warrior allies repel the invading Americans at the Battle of Beaver Dams.

Meeting between Laura Secord and Lieutenant FitzGibbon, June 1813 (painting by Lorne Kidd Smith, courtesy Library and Archives Canada/C-011053)

The official reports of the victory made no mention of Laura Secord. Laura never revealed how she came to know of the American plan, and while she did take a message to FitzGibbon, it is uncertain if she arrived ahead of Aboriginal scouts who also brought the news. FitzGibbon’s report on the battle noted: “At [John] De Cou’s this morning, about seven o’clock, I received information that . . . the Enemy . . . was advancing towards me . . . .” However, FitzGibbon did provide written testimony in support of the Secords’ later petition to the government for a pension, in 1820 and 1827.

Her action was forgotten until 1860, when the future king Edward VII awarded the impoverished widow £100 for her service. Since her death she has been frequently honoured in Canada, taking on mythological overtones. Her tale has been the subject of books, plays, and poetry, often with many embellishments. Since her death, Canada has bestowed honours on her, including schools named after her, monuments, commemorative chocolates, a museum, a memorial stamp and coin, and a statue at the Valiants Memorial in Ottawa.

Further Information:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng/Topic/43

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laura_Secord

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS

Details on my 2015 A to Z theme and a linked list of posts can be found on my A to Z Challenge page, which also has a linked list of my 2014 posts.

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 21, 2015

R is for Rottenburg

Baron Francis de Rottenburg (1757–1832) was a Swiss-born officer and colonial administrator who served in the French army 1782-1791, and then joined the British army in 1795. He was promoted to Major General and assumed command of the Montreal district when the War of 1812 broke out. This was an important post because of its location on the St Lawrence River and its close proximity to the American border.

In June 1813, he succeeded Major General Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe as military and civil commander in Upper Canada. He was accused of neglecting civil duties and of being unduly cautious in his military decisions. Rottenburg’s main concern was to preserve the army, and he was prepared to withdraw his forces to Kingston, a potential target for an American attack, if Sir James Yeo lost naval control of Lake Ontario. Nevertheless, Rottenburg ordered probing attacks against the American occupiers of Fort George and the town of Niagara as well as raids across the Niagara River. However, his refusal to send reinforcements to Major General Henry Procter, commanding on the Detroit frontier, contributed to the British defeats at the Battle of Lake Erie and the Battle of Moraviantown.

Colonel Francis de Rottenburg’s 1799 work “Regulations for the Exercise of Riflemen and Light Infantry, and Instructions for their Conduct in the Field” was widely consulted by officers during the War of 1812.

By early November he knew an American army was proceeding down the St Lawrence River against Montréal and he ordered Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Morrison to pursue the invaders. Morrison defeated part of the army at Crysler’s Farm on 11 November 1813.

The partial martial law that Rottenburg imposed in the Eastern and Johnstown districts, to force farmers to sell food and forage to the army, was an unpopular move which his successor repealed but was nevertheless forced to re-impose upon all of Upper Canada.

In December 1813, Rottenburg was succeeded by Lieutenant General Sir Gordon Drummond, and returned to his previous posts in Lower Canada. Later in 1814, when substantial British reinforcements arrived in Canada. Sir George Prevost prepared to invade the United States by way of Lake Champlain. He placed Rottenburg in command of a division of three brigades. However, Prevost personally led the campaign, which was defeated at the Battle of Plattsburgh. However, Rottenburg played no conspicuous part in the battle, with the result that he was not touched by the chorus of criticism that descended on Prevost, in part from the three brigade commanders, all of whom had seen action in the Peninsular War. In fact, Rottenburg served as president of Procter’s court martial.

Rottenburg remained in Lower Canada until July 1815 when he returned to England, where he died in 1832.

Baron Francis de Rottenburg

Further Information:

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio.php?BioId=37228

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng/Topic/93

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_de_Rottenburg

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Plattsburgh#Land_battle

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS

Details on my 2015 A to Z theme and a linked list of posts can be found on my A to Z Challenge page, which also has a linked list of my 2014 posts.

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 20, 2015

Q is for Queenston

The Battle of Queenston Heights was the first major battle in the War of 1812 and took place on 13 October 1812, near Queenston, in the present-day province of Ontario. It was fought between United States regulars and New York militia forces led by Major General Stephen Van Rensselaer, who had been humiliated at Detroit. He faced a smaller defending force of British regulars, York volunteers and Mohawks led by Major General Isaac Brock, ‘The Hero of Upper Canada’ after the victories at Fort Michilimackinac and Detroit.

Part of the American strategy in the early stages of the war was to establish an invasion bridgehead on the Canadian side of the Niagara River before campaigning ended with the onset of winter. Brock had garrisons at vulnerable points and was waiting to concentrate his defenders when American intentions were clear. Although he initially thought the main attack would come at Fort George. When the ferocity of the artillery attacks convinced him that Queenston was the invasion point, Brock took command at Queenston. After the Americans captured a strategic battery on the escarpment, Brock was killed leading a counterattack.

“Push on, brave York Volunteers!” A mortally wounded Brock urges the York Volunteers forward. (Apocryphal reconstruction, oil on canvas).

However, the American troops were pinned down on Queenston Heights by a small detachment of Mohawk and Delaware warriors. British reinforcements led by Major General Roger Hale Sheaffe arrived from Fort George, including the Coloured Corps. With many of the American militia in Lewiston unwilling to cross into Upper Canada, the poorly trained and demoralized American army was forced to surrender.

Almost 1000 Americans were taken prisoner, with 300 killed or wounded, while the victors lost only 28 killed and 77 wounded. Unfortunately, one of the losses was irreplaceable – the much-admired Isaac Brock. But his memory inspired Upper Canada to fend off subsequent American invasions.

However, US Lieutenant Colonel Winfield Scott, who had signaled the surrender, went on to become a Brigadier General and lead troops to victory at Chippewa Creek in 1814. By then American regular forces had evolved into a highly professional army, under his guidance, having modeled and trained his troops using French Revolutionary Army drills and exercises.

Further information:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng/Topic/120

http://www.history.com/news/how-u-s-forces-failed-to-conquer-canada-200-years-ago

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng/Topic/15

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Queenston_Heights

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS

A is for Anishinaabe ~ B is for Brock ~ C is for Coloured Corps ~ D is for Detroit ~ E is for Erie ~ F is for First Nations ~ G is for Ghent ~ H is for Harrison ~ I is for Impressment ~ J is for Jackson ~ K is for Key ~ L is for Lundy’s ~ M is for Madison ~ N is for New Orleans ~ O is for Ontario ~ P is for Pushmataha

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

April 18, 2015

P is for Pushmataha

Pushmataha (c. 1760s–December 24, 1824; also spelled Pooshawattaha, Pooshamallaha, or Poosha Matthaw), the “Indian General”, was one of the three regional chiefs of the major divisions of the Choctaw in the 19th century. Rejecting the offers of alliance and reconquest proffered by Tecumseh, Pushmataha led the Choctaw to fight on the side of the United States in the War of 1812.

When the neighbouring Creek Indians, then located in present-day Alabama, killed more than 500 Americans at Fort Mims on 30 August 1813, Pushmataha assumed his position as war leader. He quickly organized a Choctaw military force to assist General Andrew Jackson in fighting against the Creeks.

PUSH-MA-TA-HA. Choctaw chief, ca. 1837-1844, Publisher: McKenney and Hall, Copy after Charles Bird King

For that assistance, Jackson was forever grateful, but when the American general returned to Choctaw country in 1820 to negotiate the Treaty of Doak’s Stand, which called for Choctaw removal to lands west of the Mississippi River, Pushmataha resisted. He told Jackson that the lands in the west (present-day Arkansas) were too poor to support agriculture and hunting. In addition, Pushmataha pointed out that white settlers already lived on those lands. He knew that they would not leave voluntarily simply because the U.S. government had decided that those lands now belonged to the Choctaws.

Pushmataha tried to get a promise from Jackson to evict the white settlers, but this issue was never settled and it brought Pushmataha and other chiefs to Washington D.C. in 1824. They sought compensation for those Arkansas lands that they could never settle because of the large numbers of whites already living there. During the 1824 negotiations, his portrait was painted by Charles Bird King. Pushmataha also became sick and died. He was buried with full military honours in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Portrait of Pushmataha unveiled April 1, 2001. It hangs in the Mississippi Hall of Fame, Old Capitol Museum, in Jackson, Mississippi. The portrait was presented by the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. Portrait by Mississippian Katherine Roche Buchanan. ~ Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Many historians considered him the “greatest of all Choctaw chiefs”. Pushmataha was highly regarded among Native Americans, Europeans, and white Americans, for his skill and cunning in both war and diplomacy.

NOTE: The Memoirs in my novel “Seeking A Knife” are received by a Choctaw journalist, whose ancestors might have fought alongside Pushmataha.

Further Information

http://mshistorynow.mdah.state.ms.us/articles/14/pushmataha-choctaw-warrior-diplomat-and-chief

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pushmataha#War_of_1812

PREVIOUS A TO Z POSTS

A is for Anishinaabe ~ B is for Brock ~ C is for Coloured Corps ~ D is for Detroit ~ E is for Erie ~ F is for First Nations ~ G is for Ghent ~ H is for Harrison ~ I is for Impressment ~ J is for Jackson ~ K is for Key ~ L is for Lundy’s ~ M is for Madison ~ N is for New Orleans ~ O is for Ontario

The brainchild of Arlee Bird, at Tossing it Out, the A to Z Challenge is posting every day in April except Sundays (we get those off for good behaviour.) And since there are 26 days, that matches the 26 letters of the alphabet. On April 1, we blog about something that begins with the letter “A.” April 2 is “B,” April 3 is “C,” and so on. Please visit other challenge writers.

My theme is ‘The War of 1812’, a military conflict, lasting for two-and-a-half years, fought by the United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its North American colonies, and its American Indian allies. The Memoirs of a British naval officer from the war is central to my novel “Seeking A Knife” – part of the Snowdon Shadows series.

Further reading on The War of 1812:

http://www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng

http://www.history.com/topics/war-of-1812

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-debate/the-war-of-1812-stupid-but-important/article547554/

http://www.shmoop.com/war-1812/

http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/

![A2Z-BADGE-000 [2015] - Life is Good](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1430635005i/14737280.jpg)

![A2Z-BADGE-000 [2015] - Life is Good](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1428092352i/14364582.jpg)

![A2Z-BADGE-000 [2015] - Life is Good](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1430146589i/14686163.jpg)