Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 379

June 9, 2015

12 or 20 (small press) questions with JenMarie and Travis Macdonald on Fact-Simile editions

Fact–Simile editions

publishes handmade books, poetry trading cards, and an annual magazine. We craft books that unite content and form and expand the definition of (while bringing greater awareness to) the act of reading. We use recycled and reclaimed material when possible. Visit us at www.fact-simile.com.

Fact–Simile editions

publishes handmade books, poetry trading cards, and an annual magazine. We craft books that unite content and form and expand the definition of (while bringing greater awareness to) the act of reading. We use recycled and reclaimed material when possible. Visit us at www.fact-simile.com.JenMarie Macdonald is a writer and bookmaker living near Philadelphia. DoubleCross Press is publishing her chapbook of two essays in their Poetics of the Handmade series this spring. She collaborates with Travis Macdonald on chapbooks, including Graceries (Horse Less Press) and forthcoming Bigger On the Inside (ixnay press), as well as their press Fact-Simile Editions.

Travis Macdonald is a 2014 Pew Fellow in the Arts. He is the author of two full-length books – The O Mission Repo [vol.1] (Fact-Simile Editions) and N7ostradamus (BlazeVox Books) – as well as several chapbooks. He is a creative director by day and by night he co-edits Fact-Simile Editions with his wife JenMarie.

1 – When did Fact-Simile first start? How have your original goals as a publisher shifted since you started, if at all? And what have you learned through the process?

In 2007, Travis started publishing some short-run, staple-bound chapbooks by fellow Naropa students under the name Fact-Simile. But it wasn’t until JenMarie joined in the spring of 2008 that the press really and truly got up and running. Our original goal was pretty broad early on—we simply wanted to make lively, living spaces for our fellow writers.

At first, those spaces took shape as the simple, mimeo-style, staple-bound literary journal we still publish today. As we began experimenting with chapbook forms and learning more about the craft of bookmaking, our goals became more focused. Today, our aim is to create books whose structures perform their contents, providing tactile interactive experiences that expand upon and redefine the act of reading.

2 – What first brought you to publishing?

We both came to publishing from very different backgrounds. Travis from poetry and JenMarie from magazine journalism. Ultimately, though, what drew us both to role of small press publisher was the desire to discover and share new work. We both completed our grad studies at Naropa where there was a palpable sense that, as writers and as readers, it is absolutely critical that we create community and participate in the bigger conversation. Whether that community is enacted through a reading series, a journal, a blog, etc…the medium doesn’t matter so much as the act of connection. In many ways, that sort of public contribution feels just as necessary as the more personal acts of writing and reading.

3 – What do you consider the role and responsibilities, if any, of small publishing?

It’s probably safe to say that the role of publishers in general is, at its most basic, to connect writers with readers. In the not too distant past, that connection was made largely by a relatively small number of big publishing houses with broad distribution networks. But with more writers and (we hope) readers alive today than at any other time in the history of civilization, those monolithic publishing houses simply can’t serve the needs of an increasingly diverse population with increasingly fractured interests.

As the speed of information continues to accelerate, it enables the creation of loosely interconnected communities, connecting those fractured interests and audiences beyond geographical boundaries. We see the small press as a locus for that kind of connection, creating spaces for the exchange between writers and readers who might otherwise be disenfranchised by mass market publishing.

Since small presses are mission driven rather than profit driven, they are also able to take bigger risks than big publishing houses. This enables them to push the boundaries of what is possible in a way that we believe is vital and necessary.

4 – What do you see your press doing that no one else is?

There are a lot of talented and dedicated people running a bunch of really amazing small presses in the world today. Each of us specializes in a different combination of aspects of publishing, editing, bookmaking, etc. So there isn’t really any one thing that we are doing that no one else is, but we may spend more time considering the act of reading and how the physical form of the book affects the reading experience for each individual book more than other presses. Whether that’s through poetry trading cards or more obscure forms.

5 – What do you see as the most effective way to get new books out into the world?

For the more tactile, physical book objects we create, we still believe in the power of the post office. And other good old fashioned methods like face-to-face exchanges through book fairs and readings and such. But when it comes to building our readership, we’ve embraced many of the more technologically advanced media for promotion and communication: Facebook, email announcements, etc.

6 – How involved an editor are you? Do you dig deep into line edits, or do you prefer more of a light touch?

We look at ourselves as collaborators rather than editors. We select work for publication that we consider to be a more or less finished product. Of course, we proofread all our publications and query the writer with small suggested edits or to identify potential errors. But, for the most part, we see it as our job to focus on creating a form for the book that works with and through the text, rather than manipulate the text to fit a pre-established form or expectation.

7 – How do your books get distributed? What are your usual print runs?

The ability to take control of the means of production and distribution was really one of the things that drew us to small press publishing. While we occasionally turn to commercial printers, for the most part we make and distribute all of our books ourselves. We sell them online through our website (www.fact-simile.com), at book fairs and at readings. Because we use almost entirely recycled and reclaimed material to make our books, our print runs depend on the quantity of materials we have. But it’s typically around 100 for chapbooks. The PDF version of the journal we distribute for free online and the print version usually comes in somewhere in between 350-500 copies that we print ourselves. For the poetry trading card series, we printed 500-1000 of each.

8 – How many other people are involved with editing or production? Do you work with other editors, and if so, how effective do you find it? What are the benefits, drawbacks?

Fact-Simile is just the two of us. The benefit is that we live together, so we don’t have to work around a bunch of schedules or coordinate big editorial meetings. The drawback is that, depending on what else is happening in our life, press work can get sidelined at times.

9– How has being an editor/publisher changed the way you think about your own writing?

If there’s a secret to writing, it’s reading. As writers, WHAT we read ultimately influences our writing. Which raises the question of access. If we allowed Barnes & Noble or Amazon to curate everything we read, we would be much different writers. And with so many small presses out there publishing so many different kinds of work, curating our own experiences online can be daunting at times. As editors, we are very aware that we are curating a distinct experience for our readers. That awareness not only informs our consideration of the work that is submitted, it also helps us be more aware of how another editor may consider our own work when writing, editing and submitting. In the end, approaching our work with the understanding that every editor is curating a different sort of experience loosens the grip of doubt a little and lets us lessen our attachment to what is on the page so we can be more ruthless and risky in cutting and experimenting.

On the other hand, whether or not they know it, the readers and writers who submit to our press, are curating our reading experience in interesting and often unexpected ways, exposing us to work we may not have sought out or encountered on our own. That inevitably has a significant impact on how we read and edit our own writing.

10– How do you approach the idea of publishing your own writing? Some, such as Gary Geddes when he still ran Cormorant, refused such, yet various Coach House Press’ editors had titles during their tenures as editors for the press, including Victor Coleman and bpNichol. What do you think of the arguments for or against, or do you see the whole question as irrelevant?

10– How do you approach the idea of publishing your own writing? Some, such as Gary Geddes when he still ran Cormorant, refused such, yet various Coach House Press’ editors had titles during their tenures as editors for the press, including Victor Coleman and bpNichol. What do you think of the arguments for or against, or do you see the whole question as irrelevant?One of the first books we published was The O Mission Repo, Travis’s erasure of The 9/11 Commission Report. It gave us autonomy and the luxury to put out the book as we wanted on a specific timeline. We could be riskier with our editorial choices, and we could release the book while The 9/11 Commission Report was still something relatively fresh in people’s minds. So while we aren’t against publishing our own work in certain instances, our primary aim is to make space for the work of others.

11– How do you see Fact-Simile evolving?

In addition to the chapbooks that we make, we’d like to create more intricate book arts pieces. Eventually, we’d like to enlist some more editors and bookmakers. We’d also like see Fact-Simile evolve beyond a press into a community-based literary arts organization. With that goal in mind, we’ve recently begun collaborating with Vox Populi Gallery in Philadelphia to host craft talks and poets theater. We’re also exploring the possibility of taking on interns and eventually offering workshops.

12– What, as a publisher, are you most proud of accomplishing? What do you think people have overlooked about your publications? What is your biggest frustration?

We’re most proud of making magazines, books, and book objects that bring people new reading experiences. We have no pre-set expectation for how people should perceive and engage our work, so we can’t identify anything they’ve overlooked or that really frustrates us. Once our books are in their hands, it's about their experience, not ours. On thing does come to mind, though it’s more of a fascination than a frustration: some of our books go unread because some people are afraid to open and handle them. For instance, some people have confessed to having never broken the seal and unrolled Dale Smith’s July Oration or pulling off the rubber bands and opening the scrolls of our a Sh Anthology. This sort of behavior points to one of the ways that people engage with and develop relationships with books, letting them sit unread on shelves. Ultimately, that’s the sort of relationship we’re hoping to help shift.

13– Who were your early publishing models when starting out?

As we’ve already indicated, Naropa was a fertile and supportive place to start a literary journal, and we were taught about the history of small press publishing. Naturally, other Naropa small presses like Hot Whiskey and summer stock were models, but also Angel Hair, Big Table, Kulchur, The Floating Bear, 0 to 9, United Artists.

Elizabeth Robinson (of Instance and Etherdome) and her generous heart were huge inspirations. The Waldrops’ Burning Deck. Catherine Taylor of Essay Press was an early influence for JenMarie. The way we wanted at one time to collect every single Black Sparrow hard cover regardless of the writer, simply because they are so gorgeous. The book artist Suzanne Vilmain and her Counting Coup Press were also big influences.

14– How does Fact-Simile work to engage with your immediate literary community, and community at large? What journals or presses do you see Fact-Simile in dialogue with? How important do you see those dialogues, those conversations?

We consider ourselves extremely lucky to live in Philadelphia where there is an incredibly rich, vibrant, diverse and exciting literary community. Our most immediate interactions and engagements with that community takes place at the many readings and events we attend and host. If we extend our definition of community a little bit further, the magazine has put us in touch with an incredible network of writers across the country and beyond. While we each have our own favorite small presses (too numerous to name here) the real dialogue, from an editorial standpoint, is found in the bios of the writers we publish. As for the importance of these different levels of dialogue? It’s critical. The threads that connect the small press community are like an intricate, ongoing series of overlapping conversation where you can tune in at any one point and follow along to find yourself in some of the most unexpected and invigorating places.

15– Do you hold regular or occasional readings or launches? How important do you see public readings and other events?

Readings and other events are very important as they are phenomenal and often fertile social spaces of play, discovery, mourning, celebration, activism, generosity, etc.

For a long time, we avoided creating our own reading series simply because Philadelphia has so many great ongoing and spontaneous events that we can’t always attend them all. So, while we held sporadic, occasional readings for launches and have hosted reading slots a couple of times at the Boog Festivals in NYC, it wasn’t until this year we started hosting regular literary events for a local Philadelphia gallery called Vox Populi.

Our first event was a pair of wonderful Kevin Killian plays brilliantly performed by Philadelphia poets Jenn McCreary, Jason Mitchell, Mel Bentley, Philip Mittereder, and Alexa Smith. Our next event is a craft performance by Kristin Prevallet of her most recent work “For He Who Will Never Know How Pornography Kills the False Woman and Prevents the Live One From Breathing,” which is available for free on the Essay Press website.

A poetic game play event called “What’s the Science?” (based on an in-class prompt described to us by the poet Zach Savich) is in the works and will be a collaboration of several local presses including Philadelphia Stories , Gigantic Sequins , Apiary, and Cleaver Magazine .

16– How do you utilize the internet, if at all, to further your goals?

The internet is an important virtual social space of play, discovery, mourning, celebration, activism, generosity, etc. The internet has made it possible to better engage and unify a local community as well as cultivate and engage with a global community in real time. We share news and events on Facebook and Twitter, and the only place (beside our house and at book fairs) that our whole catalog is available is on our website. In this way, it’s a device of curation and canonization for people much in the way that anthologies have been in the past, so it has become important to provide content in the possibility that it could end up in an individual “canon." For a press focused on the physicality of books, we maintain a good deal of our relationships virtually.

17– Do you take submissions? If so, what aren’t you looking for?

We have an annual submission period for the magazine, usually January 1 through April 1 (but we opened late this year, so we may read longer). In the past, we’ve run an annual Equinox Chapbook Contest in order to accept chapbook submissions. We’ll probably open this back up next year but we’re also exploring the possibility of a more collaborative, solicitation-based system that would allow us to explore new book forms in conjunction with the writer. At this point, we’re not looking for full-length manuscripts.

18– Tell me about three of your most recent titles, and why they’re special.

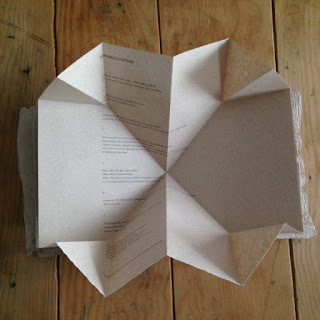

We’ve just released Jane Wong’s graceful chapbook Impossible Map. It’s a quiet, meandering text that whispers in contractions and expansions…a stillness upon which every sound is magnified. The physical book is a small 6x6 square with several Turkish map pop-up pages that unfold to four times the book’s size. Papermaker & artist Nicole Donnelly harvested the kozo for and made the Amate paper covers.

Brian Foley’s TOTEM is a microscope for image and syntax (and/or for experience) that reveals language as an (un)equatable talisman. The physical book is a denim and leather girdle book, a medieval form mostly used to hitch Bibles to a person so that they may lift it and read at any time.

Frank Sherlock’s Very Different Animals is a long poem which stops at the beginning and starts at the end. The interstitial space between these that is/is not the poem wilds itself between aggression and generation. The physical text is printed on a long sheet, accordion folded, and caged in the back hollow of a miniature canvas. Each canvas-as-cover features an original painting by the artist Nicole Donnelly.

12 or 20 (small press) questions;

Published on June 09, 2015 05:31

June 8, 2015

call for submissions : seventeen seconds: a journal of poetry and poetics,

Currently seeking submissions of interviews, essays and other critical materials for the next issue of the online journal seventeen seconds: a journal of poetry and poetics:

Currently seeking submissions of interviews, essays and other critical materials for the next issue of the online journal seventeen seconds: a journal of poetry and poetics:http://www.ottawater.com/seventeenseconds/

The first eleven issues remain online, and recent issues include work by Michelle Detorie, Cameron Anstee, Andy Weaver, Claire Molek, Chus Pato, Michael Boughn, Margaret Christakos, Victor Coleman, Marilyn Irwin, Donato Mancini, Erín Moure, Christine Stewart, Brecken Hancock, j/j hastain, Jessica Smith, David O'Meara, Wanda Praamsma, Amy Dennis, Phil Hall, Joshua Marie Wilkinson and plenty of others.

Send submissions, suggestions and pitches to editor/publisher rob mclennan via rob_mclennan (at) hotmail (dot) com

Published on June 08, 2015 05:31

June 7, 2015

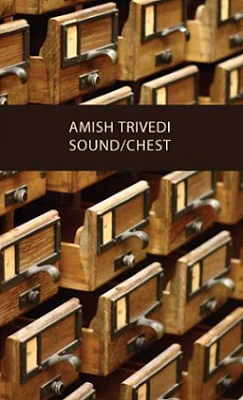

Amish Trivedi, Sound/Chest

PAINT/SWEEP 1714

This is the office soshe leans forwardagain. My washtub isblood-spattered and raucous.Even at night, Ican hear the fireworksas they bounce off theengraved faces. Elviswishes he were backin time. My president hasa handle that lacks vision. Inthe doorway I felt the brushpassed of a hand and two miceracing the hands up and down:these many aisles waveringin sawdust. It’s grainyeven when you’ve goneover a dozen times and stillthere are no songs youremember hearing.

In the “After/Word” at the back of his first trade poetry collection (and the first title by new publishing house Coven Press), Sound/Chest (Birmingham AL: Coven Press, LLC, 2015), Providence, Rhode Island poet and editor Amish Trivedi writes:

The titles to these poems come from labels on a discarded card catalogue that I found while wandering around the basement at the University of Iowa’s Main Library in June of 2008. There were several cabinets that were being prepared to go to surplus, and while normally I paid no attention to them, the fact that this one cabinet still had labels drew my eye.

While there is probably no way of knowing exactly what the catalog’s function was, a librarian’s best guess is that they were used for a custom filmstrip collection. What the words and numbers are in relation to has been lost. The filmstrip, though, is that archaic bit of grade school technology that required the teacher to assign a student to turn a knob when the supplemental audio urged her to do so, usually through the use of an annoying beep that caused the inattentive turner to startle and flip the knob quickly but always too late.

My goal was to create a relationship between these words and in most cases, the numbers. Our minds, through the use of language, create relationships between ideas all the time, and I felt that with such a diverse set of ideas existing in one collection, there was little to do but manufacture that relationship.

Through the course of sixty-one poems, Trivedi utilizes the card catalogue phrases as bouncing-off points, composing poems that link through a tenuous series of stitches, including tone, structure and the occasional reference to the library. In a forthcoming interview over at

Touch the Donkey

, he discusses some of the thematic linkages, writing: “So yes, it’s something thematically I want to figure out better but I don’t want to be heavy-handed with the social aspect of it. I want the poems to function as by themselves. It’s like Sound/Chestwhere not every poem is about being in a library or being in a flood: the poems should have an overall direction but maybe each individual portion can do its own thing and that’s cool.” What becomes less interesting than the relationships between the text and the numbers is the relationship between the binary that exists in each title, and their relationship with the resulting poem, as Trivedi allows the expanse of the archive to enter into his poems, presenting small bits of information and salvage on just about everything. Through the build-up of poems that slowly accumulate into the collection Sound/Chest, one realizes that there is a flood, and there is something kept safe in a drawer, both of which expand, and even multiply, even as they are allowed equal weight. As he writes: “I’ve stolen all the /regrets I know about.”

Through the course of sixty-one poems, Trivedi utilizes the card catalogue phrases as bouncing-off points, composing poems that link through a tenuous series of stitches, including tone, structure and the occasional reference to the library. In a forthcoming interview over at

Touch the Donkey

, he discusses some of the thematic linkages, writing: “So yes, it’s something thematically I want to figure out better but I don’t want to be heavy-handed with the social aspect of it. I want the poems to function as by themselves. It’s like Sound/Chestwhere not every poem is about being in a library or being in a flood: the poems should have an overall direction but maybe each individual portion can do its own thing and that’s cool.” What becomes less interesting than the relationships between the text and the numbers is the relationship between the binary that exists in each title, and their relationship with the resulting poem, as Trivedi allows the expanse of the archive to enter into his poems, presenting small bits of information and salvage on just about everything. Through the build-up of poems that slowly accumulate into the collection Sound/Chest, one realizes that there is a flood, and there is something kept safe in a drawer, both of which expand, and even multiply, even as they are allowed equal weight. As he writes: “I’ve stolen all the /regrets I know about.”TRUNCATED/OBVIOUS 1713

This is the worst say I know:I had this memorized before,so just turn it when—you’remissing—this finger or thatone—to a lawnmower I—heard it like that I—nogo back to the one beforethe jelly—you’re the one whospilled the paste—you’re theone who flushed thepiece of her hair bandand shat on the edge of the—problem I have is withher Father—you’re missingthe beeps and we’reout of people with—fingers.

Published on June 07, 2015 05:31

June 6, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Ian Burgham

Ian Burgham is the author of five collections of poetry published in Canada, Australia and the UK. Burgham has performed his work in many poetry venues in different parts of Canada, England and Scotland, published in over twenty-five literary and poetry journals and toured Great Britain reading at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and at Canada House in London. His newest work,

Midnight

, has just been launched by Quattro Books this year. He is winner of the Queen’s University Well-versed Award and Nominee for the ReLit Award. In October he is touring the UK with poets Steven Heighton, Catherine Graham and Manchester spoken-word poet, Mike Garry.

Ian Burgham is the author of five collections of poetry published in Canada, Australia and the UK. Burgham has performed his work in many poetry venues in different parts of Canada, England and Scotland, published in over twenty-five literary and poetry journals and toured Great Britain reading at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and at Canada House in London. His newest work,

Midnight

, has just been launched by Quattro Books this year. He is winner of the Queen’s University Well-versed Award and Nominee for the ReLit Award. In October he is touring the UK with poets Steven Heighton, Catherine Graham and Manchester spoken-word poet, Mike Garry. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I ‘m not sure the first book changed my life in substantive ways. But what it did was to convince me that someone else felt there was value for others in what I was producing. The idea that what was the result of an isolated act, a difficult solitary exercise, might be meaningful to someone else was almost a surprise. It provided me with increased confidence in showing work to others. Seeing it in print also gave me a new way to look at my poems …and suddenly you felt that maybe they just weren’t as good as they could be.

I think my most recent work is a little more ambitious in a number of ways – but I think my voice remains the same. One new thing I’ve tried in the most recent book is to link the poems with a continuous narrative that traces a moral and spiritual journey.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

When I was nine I tried to write a novel. It was as hopeless an exercise then as now. I am not a novelist or in any sense a prose writer. I don’t read novels. I can’t. I don’t like the form. I have always loved poetry – initially because it is a form of music, and that is fundamental to my being. My grandmother, with whom my family shared a house as I was growing up, kept poetry books by my Scots and Orcadian grandfathers on the shelf. So poetry was never foreign territory.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

A work, whether a long poem, or a thematic collection or an individual short poem arises out of image, sound, but always out of a feeling that declares its own significance. I don’t always know what the feeling signifies. But I start. Then what comes unfolds in a series of hooks and eyes of ideas and emotions. The first drafts are rarely anything but a beginning. And yes, I make notes over a course of time. I go through many drafts, always trying to hold on to where the poem is going. You have to be brave and be prepared to encounter anything and to move toward it, into it. Poetry is not for the fearful.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

As I said emotion, image, music, sound, smell, anything that triggers memory and the insect cloud of ideas – but always emotional significance. I do play with directed ideas later…but they tend to drag the work down into prose. However, my most recent book is more than a collection of separate poems; I started with the idea of linking locations with emotions and images, and it evolved into a narrative.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I read rarely. It is not that I don’t enjoy readings but performance is not writing. As a former musician, I know how performance can feed the ego. In a way, you work with an audience, but you can also manipulate an audience too. Primarily, performing does not engage the poetic mind; it is not the same way of mind and not the same way of being. I prefer making the work to the promotion and performing of it. I think the value in reading is that you, the poet, can hear it and know whether the music and the structure, your word and phrase choices are working. You encounter it in a new way. But my primary audience is my own ear. Reading for others is often valuable as part of the editing process, but it is a distraction. What audiences do when they hear my work, how they react, is not my business or my concern. I just hope that whatever they might find in it is meaningful.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I have one concern that may lie behind my writing; in fact, it haunts me. Why do we exist; what is the value of existence? So far the only answer I have is that we exist to make. If you strip away distractions and beliefs in anything, you come to the core of existence which seems to me to be nothing but pain and imperfection. But art gives me reason. It is the divinity of us, or in us, or at least the closest we come to it.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The role of the writer is to write. And what you create can’t be in any way satisfying, beautiful or meaningful without coming from a place of truth. So poets confront and expose and work in truth. That is a damned and unforgiving place. Who wouldn’t prefer distractions? But poets have no choice when they are in the act of making if they hope to make something that is of value.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It is essential. When I was much younger, I worked as an editor with a number of major poets in Scotland. There wasn’t one of them who didn’t work with one editor, or more than one, during the evolution of their poems. It is essential because comment and advice can strengthen the work. But editors of poetry must be poets themselves. We are often trying to overcome a nervousness that what we are producing is not quite right; there is lots of room for getting it wrong. An ignorant editor can embrace the nervousness, but a discerning one can reveal where the poetry really wants to go.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Work at the craft and then get out of the way when the poem begins to form. Then, when you think it is finished, put it away for weeks and months – when you see it again you’ll know what needs to be done. And be honest…write honestly or what you produce will have no lasting value.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I write almost every day. If I don’t, I become “antsy”, restless, unhappy. But I can’t work on poems at my desk for longer than 3-4 hours at a time.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Often other poets’ work unblocks me – one word or phrase from a good poem and my imagination and emotions begin.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The sea and salt on a cool day. I am always wondering what and where that place is.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Science is a great source of image, symbol, metaphor and meaning. But so are all the others you have mentioned.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I do not read novels. But the poetry of many others, and the writings of poets on the nature of the poetic process, are key to my understanding of where all this business comes from. However, having said that, it is James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as A Young Man to which I return often. It was the work that, when I first read it at the age of 17, gave me the first glimpse that the way the world appeared to me, and what my mind did with the ways of the world I encountered, and the words and images that emanated from it, that this was all “normal” for some – I had a community.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I have done it. But I would like to again live a life of daily literary endeavour, thought and study in exile in some other part of the world. A life lived in exile is delicious, loaded with new ways of thinking, seeing and feeling. Also I would like to collaborate with a musician/composer on a poetic work.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

A stonemason like my grandfathers.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Necessity made me write. I was born with the need and the passion, and never really wanted to do anything else.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Philip Larkin: The Complete Poems , and the notebooks of Jack Kerouac.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I am working on an idea to link a series of poems that focus on the salvation that resides in poverty, humiliation, disease, disfigurement and grief. I am heavily influenced at the moment by the paintings of the English painter, L.S. Lowry.

[Ian Burgham reads in Ottawa as part of The Sawdust Reading Series with Steven Heighton on June 10, 2015]

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on June 06, 2015 05:31

June 5, 2015

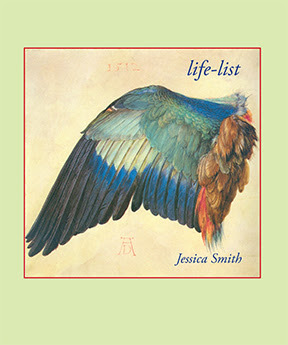

Jessica Smith, life-list

American poet Jessica Smith’s long-awaited second trade collection,

life-list

(Victoria TX: chax press, 2015), is a remarkable collection of expansive and exploded lyrics stretched and pulled apart to form staccato breaches into memory, multilinearity, meaning and language. As she explains in a recent interview posted over at Touch the Donkey: “I want to use the whole space of the page and approach it like a kind of blend between painting and poem, in that the words are usually arranged roughly left-right, top-bottom, but not entirely. I see the space of the page as already having a certain “weight,” like it’s not a blank/silent space, and that concept was molded for me by John Cage, Marcel Duchamp, Jackson Pollock and Steve McCaffery. I was also inspired, early on, by installation art, which along with sculpture is still what excites me the most: I want the audience to physically participate in the making of the object.” Structured into two sections—“observation” and “memory” (a selection of the second section published as a chapbook, here)—the poems in life-list, published a full nine years after the appearance of her Organic Furniture Cellar (Outside Voices, 2006), suggest far more might be possible, with further titles in what could simply be the opening work of something far larger. If this is Smith writing out a “life list,” how many entries might there be?

American poet Jessica Smith’s long-awaited second trade collection,

life-list

(Victoria TX: chax press, 2015), is a remarkable collection of expansive and exploded lyrics stretched and pulled apart to form staccato breaches into memory, multilinearity, meaning and language. As she explains in a recent interview posted over at Touch the Donkey: “I want to use the whole space of the page and approach it like a kind of blend between painting and poem, in that the words are usually arranged roughly left-right, top-bottom, but not entirely. I see the space of the page as already having a certain “weight,” like it’s not a blank/silent space, and that concept was molded for me by John Cage, Marcel Duchamp, Jackson Pollock and Steve McCaffery. I was also inspired, early on, by installation art, which along with sculpture is still what excites me the most: I want the audience to physically participate in the making of the object.” Structured into two sections—“observation” and “memory” (a selection of the second section published as a chapbook, here)—the poems in life-list, published a full nine years after the appearance of her Organic Furniture Cellar (Outside Voices, 2006), suggest far more might be possible, with further titles in what could simply be the opening work of something far larger. If this is Smith writing out a “life list,” how many entries might there be?Part of what is remarkable about Smith’s work is her use of fragment and space, allowing the poems such a breadth of multiple readings and meanings, even while allowing a strong intuitive narrative grounding. There is something lovely and deceptively light in the way her poems accumulate so subtly into such hefty, serious weight, pinging across the margins of the book in ways that deserve as much to be heard aloud as experienced upon the page. Further in her Touch the Donkey interview, she responds:

I choose the page as a constraint: Often when I asked for poems for periodicals, I ask the editor about the margins, page size, and font, and then I write a poem specifically for the magazine within those constraints. When I write a larger project on my own, I choose my own visual constraints. I enjoy writing by hand on square pages, but when I transfer drafts to the computer I try to choose standard printer sizes for paper and margins and standard, readable typefaces. I am constrained by the current standards of publishing, but I choose the constraint for myself with an eye to publishing because I want a larger audience than the kind of micropublishing that non-standard pages/typefaces would require. So, yes, I sometimes feel limited by page space, but the limitation is positive. I need boundaries! It helps me concentrate on other things.

Given her use of space, it becomes nearly impossible to replicate the poems in a forum such as this, but one should attempt to read as many as possible online in other places, such as here and here and here.

Published on June 05, 2015 05:31

June 4, 2015

configurations: pinhey's point (poem)

I've a new poem, "configurations: pinhey's point," on Pinhey's Point, the Ottawa historic site, now online at

Monday Night Lit

.

I've a new poem, "configurations: pinhey's point," on Pinhey's Point, the Ottawa historic site, now online at

Monday Night Lit

.

Published on June 04, 2015 05:31

June 3, 2015

Noah Eli Gordon, The Word Kingdom in the Word Kingdom

A FACT CUTS ITSELF IN TWO on the landing below the Book of Dreams. Becomes part flowering muscle, half a piece standing in for the Queen. But what of the magistrate, up in arms & waving from the margins where there is endless commerce & an amaranth on the sill? & the window itself? Its hypotheses & electronics? The white wires will stand for science, lines in the author’s poker face taken on faith. Betraying the historical underpinnings, a pin pulled outside of Alexandria. (“THE LAUGHING ALPHABET”)

Colorado poet, editor and publisher Noah Eli Gordon’s ninth poetry collection is

The Word Kingdom in the Word Kingdom

(Brooklyn NY: Brooklyn Arts Press, 2015), a collection, as his notes at the end acknowledge, “composed and revised variously between 2000 and 2013.” Given the amount he’s published over the past decade—including

Figures for a Darkroom Voice

(with Joshua Marie Wilkinson; Tarpaulin Sky, 2007),

A Fiddle Pulled from the Throat of a Sparrow

(New Issues, 2007),

Novel Pictorial Noise

(Harper Perennial, 2007),

The Source

(Futurepoem Books, 2011) and The Year of the Rooster (Ahsahta Press, 2013), as well as the work-in-progress “The Problem”—it’s curious to interact with a collection of his that include some of the first writing of his that I really connected with, discovered via his chapbook

Acoustic Experience

(Pavement Saw Press, 2008). Gordon appears to work on multiple projects concurrently, which means that some of the work in the current collection might even pre-date a couple of his entire already-published poetry books. Going through the poems that make up The Word Kingdom in the Word Kingdom, and being aware of so much of his other poetry books have been constructed as book-length projects, this collection almost appears as a collection of stray poems, composed over an extended period as comparatively stand-alone pieces that simply accumulated. The linkages between the poems are there, both in tone and structure, even amid the variety of prose poems, short sequences and tight lyrics. Jack Spicer referred to such disconnected or stand-alone pieces as “one night stands,” and Gordon, now, has a collection of such, akin to Toronto poet and BookThug publisher Jay MillAr’s Other Poems (Nightwood Editions/blewointment, 2010), or Vancouver poet George Bowering’s book of magazine verse, In The Flesh (McClelland & Stewart, 1974), which itself riffed off Spicer’ own “Book of Magazine Verse” from The Collected Books of Jack Spicer (Black Sparrow Press, 1975). In his “Afterword” to the collection, Gordon writes:

Colorado poet, editor and publisher Noah Eli Gordon’s ninth poetry collection is

The Word Kingdom in the Word Kingdom

(Brooklyn NY: Brooklyn Arts Press, 2015), a collection, as his notes at the end acknowledge, “composed and revised variously between 2000 and 2013.” Given the amount he’s published over the past decade—including

Figures for a Darkroom Voice

(with Joshua Marie Wilkinson; Tarpaulin Sky, 2007),

A Fiddle Pulled from the Throat of a Sparrow

(New Issues, 2007),

Novel Pictorial Noise

(Harper Perennial, 2007),

The Source

(Futurepoem Books, 2011) and The Year of the Rooster (Ahsahta Press, 2013), as well as the work-in-progress “The Problem”—it’s curious to interact with a collection of his that include some of the first writing of his that I really connected with, discovered via his chapbook

Acoustic Experience

(Pavement Saw Press, 2008). Gordon appears to work on multiple projects concurrently, which means that some of the work in the current collection might even pre-date a couple of his entire already-published poetry books. Going through the poems that make up The Word Kingdom in the Word Kingdom, and being aware of so much of his other poetry books have been constructed as book-length projects, this collection almost appears as a collection of stray poems, composed over an extended period as comparatively stand-alone pieces that simply accumulated. The linkages between the poems are there, both in tone and structure, even amid the variety of prose poems, short sequences and tight lyrics. Jack Spicer referred to such disconnected or stand-alone pieces as “one night stands,” and Gordon, now, has a collection of such, akin to Toronto poet and BookThug publisher Jay MillAr’s Other Poems (Nightwood Editions/blewointment, 2010), or Vancouver poet George Bowering’s book of magazine verse, In The Flesh (McClelland & Stewart, 1974), which itself riffed off Spicer’ own “Book of Magazine Verse” from The Collected Books of Jack Spicer (Black Sparrow Press, 1975). In his “Afterword” to the collection, Gordon writes:This is where the poem begins: the Word Kingdom. When I was about twenty, I remember sitting in my room one night, annoyed with something my housemates were up to, and a bit bored with whatever my other friends were doing. It was one of those evening[s] where you just feel aimless, off-balance, agitated. There was something gnawing at me, but I didn’t know what. Then, out of nowhere, a procession of sirens passed by my house. I mean there were fire trucks, police cars, a few ambulances, lots and lots of noise—sudden, alarming noise; then, nothing. It was dead silent for maybe a second or two before the sirens picked up again. This time they seemed to come from every direction, as though they were surrounding the house. But the pitch was off, all wobbly, a weird vibrato, like electronics trying to run on nearly dead batteries. The sound wasn’t coming from the sirens at all. It was an animal sound. It was every dog in the neighborhood at once attempting to imitate the noise. It was the word kingdom. None of them could do it quite right, but damn were they going for it. It felt simultaneously sad and triumphant. It was the exact moment I decided to be a writer. I’m not writing the noise of the sirens, nor am I writing the noise of the dogs. I hope my poems take root in the silence after the two have sounded: mimetic chatter and babble paradoxically from intellection to imagination. The word kingdom in the Word Kingdom.

The collection reads as though Gordon, over the years, has been utilizing short lyrics as a way to sketch out a series of commentaries on contemporary poetry, and this is simply the accumulation of pieces that could easily have been written as short essays. These are notes on form, structure and subject, playing off a level of cultural expectation in poetry, with the occasional playful jab or exploration at elements of his contemporary field, as a number of his titles suggest, such as “A THEORY OF THE NOVEL,” “FOR EXPRESSION,” “QUESTIONS FOR FURTHER STUDY,” “AGAINST ERASURE,” “ARS POETICA,” “ANOTHER COMMENT ON THE TEXT” or the three poems titled “BEST AMERICAN EXPERIMENTAL POETRY.” I find it curious that Gordon has chosen to explore ideas of poetry through the form of the poem (much in the way that Stephen Brockwell and Peter Norman once collaborated in a conversation on the form of the sonnet through the form of the sonnet, or Mark Truscott’s short prose pieces on poetic brevity). His is a call to action, attention and an engagement with form over fashion, such as in the poem “EIGHT MEDITATIONS ON ENORMITY, PETRIFACTION, AND WORK,” that includes: “But wasn’t there much left to learn from the old ways? / Hadn’t we heard a literal train of thought approaching from / the past?” In a field of poetic discourse that is too often far too unpoetic and staid, Gordon’s notes on form are a welcome relief.

CONTINUED ETHICAL ENGAGEMENT OF THE NARRATIVE TRADITION

Concise articulation wasn’t what we’d wanted, exactly.I’m not so sure the line matters. I’m not so surethe line matters. You don’t just get on a motorcycle and becomea kind of historical category. First, they considered foundinga unified artistic school with a coherent program. Them, the sunagain disappeared over hilltops. Was this the extension of powerby an expansionist idea about the world being purely internalized?Think: childhood but with the irony, an unattainable conditionin which we collectively float. It takes at least as much scrutinyas standing on one shore and looking at another. Instead, we spenda lot of tie staring at ink stains. Call it disregard for whateverone proposes as the latest craze of substantive adherenceand simplistic acquiescence to wallpaper wallpaper wallpaper.Look imaginatively at a pineapple and disappear. Look imaginativelyat a pineapple and disappear. The poem isn’t interested in helping you.

Published on June 03, 2015 05:31

June 2, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Anne Champion

Anne Champion is the author of

Reluctant Mistress

(Gold Wake Press, 2013) and The Dark Length Home (Noctuary Press, 2017). Her poems have appeared in Verse Daily, The Pinch, Pank Magazine, The Comstock Review, Thrush Poetry Journal, Redivider, Cider Press Review, New South, and elsewhere. She was a recipient of the Academy of American Poet’s Prize, a recipient of the Barbara Deming Memorial grant, a Pushcart Prize nominee, a St. Botolph Emerging Writer’s Grant nominee, and a Squaw Valley Community of Writers Poetry Workshop participant. She holds degrees in Behavioral Psychology and Creative Writing from Western Michigan University and received her MFA in Poetry from Emerson College. She currently teaches writing and literature at Wheelock College in Boston, MA and is a staff writer for Luna Luna Magazine.

Anne Champion is the author of

Reluctant Mistress

(Gold Wake Press, 2013) and The Dark Length Home (Noctuary Press, 2017). Her poems have appeared in Verse Daily, The Pinch, Pank Magazine, The Comstock Review, Thrush Poetry Journal, Redivider, Cider Press Review, New South, and elsewhere. She was a recipient of the Academy of American Poet’s Prize, a recipient of the Barbara Deming Memorial grant, a Pushcart Prize nominee, a St. Botolph Emerging Writer’s Grant nominee, and a Squaw Valley Community of Writers Poetry Workshop participant. She holds degrees in Behavioral Psychology and Creative Writing from Western Michigan University and received her MFA in Poetry from Emerson College. She currently teaches writing and literature at Wheelock College in Boston, MA and is a staff writer for Luna Luna Magazine.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book, Reluctant Mistress, didn’t significantly change my life. The process of writing it taught me a lot, both about myself and about craft. Publication was simply a goal completed that allowed me to move on and dedicate my energies to other projects. The best part of publication was having readers who fully understood my work. I’m so humbled and grateful for the warmth of the poetry community—that simply means everything. It gives my life a sort of fulfillment that I never dreamed I’d have.

My new collection set for publication by Noctuary Press, The Dark Length Home, is a collaborative collection that I wrote with the incomparable Sarah Sweeney. It was an experience I treasure. I generally have a plan as I sit down to write a poem. I know what images I will focus on, I know what story I want to tell, and I have a general idea of how it will end. With Sarah, we alternated line by line. I had to let go of control, and it was exciting. Poems would take turns I didn’t expect, and I had to adapt to tones and voices that were not my own. I’m really proud of how we navigated the process, and I think it pushed me in new directions.

I’m working on other collections, and I always want to challenge myself in terms of topics that I obsess over and formal constraints. I am trying to do something new with each one. At some point in time, I started to feel like I was writing about the same thing repeatedly, and I needed to challenge myself. I definitely think I’m doing that with my new work.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I actually came to fiction first. I wrote stories from the time I was a child and I studied primarily fiction through college. However, at some point in my college experience, poetry simply started to become the genre that spoke to me most forcefully, moved me most emotionally, and served me as a writer. Once I started writing poetry, I stopped writing everything else. I still read all genres of writing religiously, but poetry allows me to express what I want in a variety of creative ways.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

The initial draft work comes quickly to me. I’m usually struck by an image, a line, or a concept and it harasses me until I begin to interrogate it through writing it down. I’ll shape it into a poem fairly fast. However, the revision process is often long, tedious, and torturous. I have a group of writers that I bring drafts to and rely on for revision advice. I’ll often play with various forms and structures, going back and forth between new and old drafts. Sometimes the revision comes within weeks, sometimes I keep tweaking a poem for years. Some poems I finally abandon and throw away. Regardless, the final draft rarely looks like the original.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Within the last few years, I have focused on making a book from the beginning. It seems that, in terms of both getting a manuscript published and in reader’s experience of the work, it’s best to have a cohesive collection. My first two collections (one which is unpublished), did not really begin as a “book” per se, though I tried to structure them so that they look at specific themes. In writing them, I was simply writing poems about all different things that inspired me. Now, I generally start with a vision for a book, and focus my writing on exploring that vision.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Public readings are necessary to the process, as they get your writing out in the world and allow you to expose it to new people. I enjoy performing in front of crowds, so I’ve always enjoyed readings. However, after my first book, I did so many readings that I had to take time off from it—I got very burned out, and I just wanted to hole myself away and focus on new work.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I don’t have specific questions, but I do have obsessions that I’ve been exploring for years. Some of my obsessions include female sexuality, feminism, sexual liberation, abuse, war, race, and oppression. In terms of questions, I always think of my poems as interrogating a wound.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

In many cultures, poets are revered. When I was doing activist work in Palestine, Palestinians would always tell me that I was a messenger for God, because “a poet speaks God’s pain.” I found this sentiment lovely (though it certainly put a lot of expectation on my work!)

I think writers are important in that artists play a role in creating culture, reflecting cultural values, and capturing the sentiments of a historical moment. No matter what you are writing, you are writing in the context of culture and history; thus, we have a very important responsibility to respect that and reflect deeply upon the issues of our time. We need to be creatures of empathy and morality, though we may not be perfect ourselves—in our writing, we should be striving for the better world.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It’s essential for any writer to work with other people. Many people think of it as such a solitary profession, but I really don’t think it should be. Our work is not read in a vacuum, and it shouldn’t be written in one either. We need an audience and we need feedback to perfect our craft. I’ve never had a bad experience working with an editor. In fact, I quite like my editors!

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I saw Michael Cunningham speak when I was in college. Someone asked him what advice he could give to young writers. His answer was simple: “It’s going to take a really, really long time to see your work in print. You are going to be rejected a lot. You have to be really patient and really determined to keep trying and keep writing.” It seems like common sense, but I really took it to heart. I don’t let rejection bother me. I just keep focusing on trying to make my writing better and make my projects become something I’m personally proud of. Even if they never see the light of day, the process of writing is still very fulfilling to me, in and of itself. I want my work to be read, but I don’t make publication a measure of my happiness as a writer. When I have success, I consider it a bonus to something that I already love, something that is a major part of who I am.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don’t really have one. As a professor, I try to sneak in writing whenever I can. I dedicate myself most to writing when I have time off. I don’t think a writer needs to write every day to be a real writer; part of being a writer is experiencing life and processing the world mentally and emotionally.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I go to books of poetry that I know have powerfully moved me. When I re-read books that changed me, I usually feel inspired immediately. Or I look for new books of writers who are exploring themes that I’m interested in. Whenever I find a poem I wish I wrote, I get very excited about going back to writing and experimenting on the page.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I don’t think I’ve fully figured out what home means to me. I feel at home in a lot of places. I feel most at home when I’m traveling far from home. (Though I miss my cats!)

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I know a lot of writers that dabble in other arts or use other arts for their inspiration. For me, personally, books really do come from books. I love all forms of art and I try to expose myself to it as much as possible, but they rarely explicitly influence my work. Whereas writers influence my work constantly. I wouldn’t change or experiment if it were not for what I’d seen other writers do. I get most inspired while reading.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

There’s so many!! This is always the hardest question because I want to rattle off a long list. Sylvia Plath is really my backbone as a poet. If it were not for her, I would not be a poet. She showed me how to write about rage, pain, and abuse with such musical grace, and I still think no one holds a candle to her metaphors. Anais Nin influenced me in terms of sexual liberation and feminist themes. I also love Louise Gluck, Tarfia Faizullah, Traci Brimhall, Sharon Olds, Mark Doty, Sandra Cisneros, and Junot Diaz.

In terms of my life outside of work, there are several poets who have been an incredible support system: Lisa Marie Basile, Mary Stone, and Kristina Marie Darling, to name a few. I also greatly admire their writing.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Work in a refugee camp in the Middle East.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I would be a full time activist and community organizer. That’s hard to make a living doing, but I’m so inspired by revolutionaries that sacrificed everything for social change. I was really inspired by young peace activists that I met in Palestine; they are doing such creative things! I’d love to be fully immersed in that.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I write because I have to. Words haunt me, and if I don’t get them out then I’ll lose my mind. I write to know who I am and understand the world better. I write to increase my sense of empathy for others. I write because I simply have no choice. It gives my life depth in ways that nothing else does.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I recently read Nelson Mandela’s autobiography Long Walk to Freedom . As an activist, I found his voice to be monumentally inspiring, full of wisdom, dogged patience, and compassion.

I don’t see a lot of movies (I’m more of a TV gal), but I really loved Selma.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I’m currently working on revising a manuscript called Graveyard of Numbers which is the result of a Peace Delegation that I went to in Palestine. The manuscript documents the many stories I was told by locals in documenting the horrors of war and military occupation. It also ties in issues of race and oppression in American culture.

My next manuscript, which I’ve started the process of writing, will be Odes and Persona poems to famous historical women. So far I have poems to Annie Oakley, Amelia Earhart, Judy Garland, Sylvia Plath, Harriot Jacobs, Anne Frank, and others. I hope to have a broad range in terms of race and sexuality, including transgender women and men.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on June 02, 2015 05:31

June 1, 2015

dusie : the tuesday poem,

The Tuesday poem is two years old, with more than one hundred new poems and counting! Since April 9, 2013, I've been curating a weekly poem over at the dusie blog, an offshoot of the online poetry journal Dusie (http://www.dusie.org/), edited/published by poet and American expat Susana Gardner.

The Tuesday poem is two years old, with more than one hundred new poems and counting! Since April 9, 2013, I've been curating a weekly poem over at the dusie blog, an offshoot of the online poetry journal Dusie (http://www.dusie.org/), edited/published by poet and American expat Susana Gardner.http://dusie.blogspot.ca/

The series aims to publish a mix of authors from the dusie kollektiv, as well as Canadian and international poets, ranging from emerging to the well established. Over the next few weeks and months, watch for new work by dusies and non-dusies alike, including Steve McOrmond, Lily Brown, Daniel Scott Tysdal, Beth Bachmann, Harold Abramowitz, Sarah Burgoyne, David James Brock, Elizabeth Treadwell, Shannon Maguire, Mary Austin Speaker, Victor Coleman, Charles Bernstein, Jennifer K Dick, Eric Schmaltz, Kayla Czaga, Paige Taggart, Hugh Behm-Steinberg, Lillian Necakov, Liz Howard, Jamie Reid, Jennifer Londry, Rachel Loden, a rawlings, Jenny Haysom, Jake Kennedy, Beverly Dahlen, Kristjana Gunnars, Eleni Zisimatos, Pete Smith, Julie Carr, Natalee Caple, Alice Burdick and Phinder Dulai.

A new poem will appear every Tuesday afternoon, Central European Summer Time, just after lunch (which is 8am in Central Canada terms).

If you wish to receive notices for poems as they appear, just send me an email at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com.

So far, the Tuesday poem series has featured new writing by Elizabeth Robinson, Megan Kaminski, Marcus McCann, Hoa Nguyen, Stephen Collis, j/j hastain, David W. McFadden, Edward Smallfield, Erín Moure, Roland Prevost, Maria Damon, Rae Armantrout, Jenna Butler, Cameron Anstee, Sarah Rosenthal, Kathryn MacLeod, Camille Martin, Pattie McCarthy, Stephen Brockwell, Rosmarie Waldrop, Nicole Markotić, Deborah Poe, Ken Belford, Hugh Thomas, nathan dueck, Hailey Higdon, Stephanie Bolster, Jessica Smith, Mark Cochrane, Amanda Earl, Robert Swereda, Colin Smith, Sarah Mangold, Joe Blades, Maxine Chernoff, Peter Jaeger, Dennis Cooley, Louise Bak, Phil Hall, Fenn Stewart, derek beaulieu, Susan Briante, Adeena Karasick, Marthe Reed, Brecken Hancock, Lea Graham, D.G. Jones, Monty Reid, Karen Mac Cormack, Elizabeth Willis, Susan Elmslie, Paul Vermeersch, Susan M. Schultz, Rachel Blau DuPlessis, K.I. Press, Méira Cook, Rachel Moritz, Kemeny Babineau, Gil McElroy, Geoffrey Nutter, Lisa Samuels, Dan Thomas-Glass, Judith Copithorne, Deborah Meadows, Meredith Quartermain, William Allegrezza, nikki reimer, Hillary Gravendyck, Catherine Wagner, Stan Rogal, Sarah de Leeuw, Tsering Wangmo Dhompa, Arielle Greenberg, lary timewell, Norma Cole, Paul Hoover, Emily Carr, Kate Schapira, Johanna Skibsrud, Joshua Marie Wilkinson, David McGimpsey, Richard Froude, Marilyn Irwin, Carrie Olivia Adams, Aaron Tucker, Mercedes Eng, Jean Donnelly, Pearl Pirie, Valerie Coulton, Lesley Yalen, Andy Weaver, Christine Stewart, Susan Lewis, Kate Greenstreet, ryan fitzpatrick, Amish Trivedi, Lola Lemire Tostevin, Lina ramona Vitkauskas, Nikki Sheppy, N.W. Lea, Barbara Henning, Chus Pato (trans Erín Moure), Stephen Cain, Lucy Ives, William Hawkins, Jan Zwicky, Rusty Morrison, Jon Boisvert, Helen Hajnoczky, Steven Heighton, Jennifer Kronovet and Ray Hsu.

Published on June 01, 2015 05:01

May 31, 2015

prose in the park + the ottawa small press book fair!

Yes, there are two book fairs coming up in Ottawa, if you can believe it:

Yes, there are two book fairs coming up in Ottawa, if you can believe it:Prose in the Park: June 6: the first of what suggests as an annual event, comparable to when we used to have Word on the Street in town (remember those?). Big, medium and small publishers will be displaying and selling their wares, and a number of authors will be reading throughout the day. And of course, Chaudiere Books will be there as well (thanks to Marilyn Irwin...).

the ottawa small press book fair: June 12 (pre-fair reading) and June 13 (fair itself): co-invented by myself, I've been running it twice a year since it was founded way, way, way back in 1994. Quite honestly, the best of the small press. If you love great writing, small publishing and a whole ton of local materials that you might not otherwise be aware of, this is your event.

And then, of course, Congress is happening right now at the University of Ottawa, which also includes a book fair.

We live in glorious times, I'd say.

Published on May 31, 2015 05:31