Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 333

September 11, 2016

Jennifer Moore, The Veronica Maneuver

SONETTO

Think of the thing that dislocates your ear,then imagine how the ear is recovered. The blast

and cure, what detonates and mends; and then,how to restring the instrument. Here the gondoliers

have no need for us; they sing into their own canalsand navigate the city without sinking. Sound

is a form of energy that moves through air and water;its waves of pressure collect in us. What you want

is char without fuel, sonetto, a little song to fill the jar;you want shaken bottles and sudden explosions.

What I want is your flammable mouth, its cinematicmottle and cue. We agree to disagree. Gondolier,

navigate the city without poles. Let the little songand its echo fly through your unfastened ear.

I’m charmed by the narrative lyrics that make up Ohio poet Jennifer Moore’s first full-length poetry collection,

The Veronica Maneuver

(Akron OH: The University of Akron Press, 2015), a book that follows her poetry chapbook, What the Spigot Said (Salt Lake City UT: High5 Press, 2009). Set in two sections of shorter poems on either side of the eleven page poem-section “The Quiet Game,” the pieces in Moore’s The Veronica Maneuver are sharp, and even striking, in parts. The variety of her structure and line-breaks becomes interesting, from the pauses generated through an accumulation of short lines to her prose poems, packing in as much as possible in small spaces. As she writes in her title poem:

I’m charmed by the narrative lyrics that make up Ohio poet Jennifer Moore’s first full-length poetry collection,

The Veronica Maneuver

(Akron OH: The University of Akron Press, 2015), a book that follows her poetry chapbook, What the Spigot Said (Salt Lake City UT: High5 Press, 2009). Set in two sections of shorter poems on either side of the eleven page poem-section “The Quiet Game,” the pieces in Moore’s The Veronica Maneuver are sharp, and even striking, in parts. The variety of her structure and line-breaks becomes interesting, from the pauses generated through an accumulation of short lines to her prose poems, packing in as much as possible in small spaces. As she writes in her title poem:If I were a bull, I’d have to decide between focusing on a target and charging everything that moves. Either way, I’d get hooked behind the shoulder and brought to my knees in front of everybody. What the spectators want is the estocada, the death blow and difficult exit. So banderilleros toss darts into the bull’s back; then flowers for the matador, while the body’s dragged from the ring. You wear a muleta as a little retro jacket; we pour one out for the bull.

Occasionally there are places in which I wish her poems were tighter, but the wit and will of such a first collection, I’d suggest, allows for the occasional moment. Either way, I am curious to see what she might do next.

Published on September 11, 2016 05:31

September 10, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Angeline Schellenberg

Angeline Schellenberg’s

poems appear in journals such as

CV2

, TNQ, Grain, and

Lemon Hound

. Her first chapbook, Roads of Stone (the Alfred Gustav Press), launched in May 2015. Her poetry won third prize in Prairie Fire’s 2014 Banff Centre Bliss Carman Poetry Award Contest and was shortlisted for Arc Poetry Magazine’s 2015 Poem of the Year. Angeline lives and reads in Winnipeg with her husband, their two teenagers, and a German shepherd-corgi.

Tell Them It Was Mozart

(Brick Books) is her first full-length collection.

Angeline Schellenberg’s

poems appear in journals such as

CV2

, TNQ, Grain, and

Lemon Hound

. Her first chapbook, Roads of Stone (the Alfred Gustav Press), launched in May 2015. Her poetry won third prize in Prairie Fire’s 2014 Banff Centre Bliss Carman Poetry Award Contest and was shortlisted for Arc Poetry Magazine’s 2015 Poem of the Year. Angeline lives and reads in Winnipeg with her husband, their two teenagers, and a German shepherd-corgi.

Tell Them It Was Mozart

(Brick Books) is her first full-length collection.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?The day I got the email from Brick Book’s acquisitions editor Barry Dempster – asking for permission to shortlist my manuscript – was one of the happiest days of my life. Even if Brick had chosen not to publish this book, knowing Barry Dempster thought my work “had guts” and “resonated” made me feel like I’d become an author.

How the book will change my life remains to be seen! I expect it will give me opportunities to see more of Canada.

The difference between my 2015 chapbook Roads of Stone and this book is that Roads was inspired by other people’s stories, whereas Tell Them It Was Mozart is all about my own. And Mozart has more variation in form and tone; overall, Mozart is more playful, less serious.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?I did go to non-fiction first because it felt less risky. About ten years ago, I started sending good news stories about non-profits to a monthly newspaper, and they took them every time, eventually offering me a mental health column. Now I write/copyedit part-time for a national church magazine. I love it when an interviewee says things like “You captured the heart of what we’re about.” I’ve met some interesting people, from matchmakers to Elvis impersonators.

I always wanted to do poetry, but there was an anxiety in the way; I was afraid of writing bad poetry. What I discovered is that all poetry starts as bad poetry. You just have to keep writing past it. In 2011, my desire overcame my fear.

What I love about poetry is that I (as a reader and a writer) can dip deep into an emotional experience, and then come up for air in a hurry. I didn’t need a long attention span (what mother has one?) or a great memory (lost that too). The intensity of poetry was perfect for giving others an experience of mothering autism and for subverting some of the negative messages out there.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?I hear other people talk of running to a notebook because a great line just popped into their heads. Don’t I wish! I start scribbling and ideas come only as my pen is moving.

I find the blank page less frightening than the flashing cursor, so I start with erasable pen in notebooks and then I type out and rearrange the words on the screen.

I have the rare poem that keeps its original form (I think the final poem in the book is one of them), but most of them have gone from prose poems to couplets and back, been turned backwards and upside down.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?I always work on full manuscripts from the beginning. I need a topic, otherwise I don’t know where to start. With the autism poems, I had lists of things I wanted to cover; e.g., drug trials, echolalia, bolting. And every day, new experiences made the list longer. I never had to wonder what to write about.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?I love public readings, both as reader and a listener. The spoken poems buzz in my brain, and the energy of the audience adds to the experience.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?With Tell Them It Was Mozart, the political questions were always in my head. Am I portraying autism too negatively and thereby doing a disservice to the autism community that deserves to have their strengths known? Am I not being honest enough about the difficulties, thereby disrespecting other parents fighting for support? Am I putting myself on every psychiatrist’s blacklist by saying this?

Autism conversations can be polarizing. They get derailed quickly when someone wants their child referred to as “autistic,” and someone else prefers “person with autism.” Or when one parent thinks a vaccine causes autism and another says it’s a gluten issue. The very people who might actually be able to understand one another are sometimes the ones at each other’s throats. (Mostly it’s because we’re so darn tired!) The book rarely mentions autism directly (and when it does, it’s usually in the context of found poems) because the focus is on who the children are, not how they’re labelled.

Your question about questions makes me laugh because, well, here are the sorts of things Tell Them It Was Mozart asks: “Have already we watched ‘The Survivor in the Soap’?” “Did you notice I was holding a banana?” The media asks all kinds of things about autism. I think these are closer to the right questions.

The main thing I want to get across with this book is joy. The joy of looking at the world differently.

The joy of connecting as family, even if that looks different from what you expected.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?I don’t have any grand notions about changing culture. But eventually 600 people will own a copy of my book: that’s 600 people who may respond more gently to a child screaming in a checkout line or flapping his hands at his desk. If even just one reader tells a mom, “I’m here with you” (instead of “you should have been spayed”), that’s a big win.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)? Definitely both! Murphy’s Law: it often happens that the poems I want help to completely rewrite, editors beg me not to touch, whereas the poems that sing in my head are the ones they suggest I revise or cut completely.

At first, in the editing process, I had the mental picture of ripping seams, but then I realized that the fabric was intact. All we were doing was pulling out a few embroidered flowers and replacing them with equally beautiful songbirds. Then I felt better.

It was so valuable to hear an editor say that the effect I was going for wasn’t getting across yet. The tricky part was clarifying the message without losing the music. Sometimes I argued for my original, sometimes I fell in love with my editor’s wording, but more often it led to the creation of something brand new – a very productive process.

I recently went back over the many poems that I ached over cutting from the book, to see if I could turn them into a chapbook. I realized that none of them were worth keeping. And when I read the proofs, some of the new poems – which I was originally unsure about adding – became my favourites.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?Don McKay told me to “Let the dog off the leash.” In encouraging me to write more prose poetry, he said, “The lyric is a bird flying from treetop to treetop. The narrative is the dog sniffing here and here: it brings home unlikely things.”

In my fear that what flowed out of me naturally wasn’t “poetic” enough, I’d been privileging the bird and forgetting the dog. Since then, I’ve given myself more permission to write long lines about everyday things like vomit and dryers without fear of being prosaic. It doesn’t have to look like a poem (or smell like roses) to be poetry.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?On my days off, I get home from dropping my daughter off at school, walk the dog, make my second cup of coffee, sit down on my sofa at my south-facing window, and write most of the day. Saturday morning I go straight to work in my pajamas and don’t stop until “lupper” – like brunch but we eat it between lunch and suppertime to stretch out that Saturday morning feeling. Sundays after church are another peaceful time for poetry. Even on days I’m going into the office, I do some poetry with my first coffee before getting the kids up for school. I write best in the morning – before my inner critic wakes up. My best time of year is summer when I can sit on my backyard swing, or by a campfire, or on a dock somewhere and write.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?When I get stalled writing new material, I rework old pieces and submit completed ones to journals and contests. Or when it feels like there aren’t any words in my own head, I write found poetry: erasure, oulipo, collage.

For inspiration, I reread some of my mentors’ work, until I hear the encouraging things they’ve told me in the past singing in my head again. (Don McKay once told me, “You rock!”) I read poets I love, and sometimes I try finishing one of their sentences and see where it takes me.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?The farm where I grew up: lilacs, freshly mowed grass, French bread baking.

My current home in Winnipeg: bologna, sweaty teenager, and dog.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?Mostly my work comes from everyday life experiences, either my own or the ones I live vicariously in conversations with others.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?Joanne Epp and I have workshopped our new poems every month since 2011. I rarely submit anything without it passing her desk first. Our styles are different, but I trust her completely.

Sarah Klassen’s book Journey to Yalta was the first poetry book I picked up when I decided to become a poet, and she was the first poet I asked, “Is this any good?”

Meira Cook and Don McKay were a big part of how Tell Them It Was Mozart came together. Meira mentored me through the Manitoba Writers’ Guild Sheldon Oberman Mentorship Program in 2012 when I was just starting out. Don McKay was my instructor at Sage Hill in 2013 when I was getting the manuscript ready for submission.

Jennifer Still led the first poetry workshop I attended and many I’ve attended since. She’s the one who directed me to found poetry.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?Since my relationships with my husband of 22 years and with God are the most intimate, and sometimes the most difficult, I’d like to write great love poems and devotional poems – both very hard to do well.

I’ve always wanted to visit the Maritimes. And to take my family to Straubing, Germany – the village where I lived in the summer of 1993, when I volunteered for an organization that assisted refugees.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?I wish I could be a figure skater, contemporary dancer, or gymnast, but since (growing up Mennonite in the 1970s) I wasn’t allowed to even tap my toes until my twenties, the connection between my limbs and my brain is lacking.

I enjoy languages, so I thought of being a translator or linguist. I studied French and German in high school; and Greek, Hebrew, Ugaritic, and Aramaic in seminary. But two weeks after earning my MA, I gave birth (trading textbooks for Dr. Seuss) and promptly forgot all of them.

Clarinet was my thing in high school, so I considered studying music performance. But I let the competitiveness of the music scene scare me away. I don’t regret it; writing does everything music did for me and more.

I love babies. I think I’d enjoy fostering someday. But I’ve gotten used to not having my cupboards emptied and sleep interrupted, so it would take some adjustment, for sure.

Someday I might like to be a spiritual director. Walking alongside someone through their spiritual journey is as profound as poetry.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?Writing makes me happy.

I tried teaching college, and I could do it, but I hated feeling on the spot for three hours at a time in front of a room full of bored 18-year-olds. With writing, I can mull over what I want to say for ages before anyone else needs to hear it.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?I read poetry almost exclusively. Recently I’ve enjoyed Our Andromeda by Brenda Shaughnessy, Transmitter and Receiver by Raoul Fernandes, Verge by Lynda Monahan, and Heaven’s Thieves by Sue Sinclair.

I won’t even try to comment on cinema. I have two teenagers, so I mostly watch things with Iron Man in them.

19 - What are you currently working on?Two years ago, I started a side project about colours. It was a fun break from the difficult emotional work of confessional poetry. This research-based work allowed me to write about cultures and history I hadn’t experienced, to explore my darker, sexier, more exotic side. Now that it’s my main project, I really miss confessional writing: that satisfaction of moving something from deep inside me into the world.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on September 10, 2016 05:31

September 9, 2016

Drunken Boat blog "spotlight" series #5: Jennifer Kronovet

The fifth in my monthly "spotlight" series over at the Drunken Boat blog, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online: American poet Jennifer Kronovet. The first four in the series feature

Ottawa poet Jason Christie

,

Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough

,

Ottawa poet Amanda Earl

, and

American poet Elizabeth Robinson

. A new post is scheduled for the first Monday of every month.

The fifth in my monthly "spotlight" series over at the Drunken Boat blog, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online: American poet Jennifer Kronovet. The first four in the series feature

Ottawa poet Jason Christie

,

Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough

,

Ottawa poet Amanda Earl

, and

American poet Elizabeth Robinson

. A new post is scheduled for the first Monday of every month.

Published on September 09, 2016 05:31

September 8, 2016

Tommy Pico, IRL

Regret is a giftthat keeps on giving I think it was Sontagor Sonic the Hedgehogwho said just dash dodgeweave faster than youcan think n there’s notime to shame spiralCrushingon Muse—whoseeven slight squint burstsme into high July—while dialing,essentially, a trick.This is my argument:Muse crashes intothe edges of my nights,isn’t crushing,doesn’t love me,doesn’t have his shittogether (tho neither,frankly, do I) but yanksme n my hand onto the dancefloor til tilt-a-whirl Goes onlike land, just accum-ulating in my eyes.

“[A] sweaty, summertime poem composed like a long text message” is how the back cover describes Brooklyn, New York poet and editor Tommy Pico’s first full-length poetry title,

IRL

(Birds, LLC, 2016). There is something very clear in the text as to why Pico was named by Flavorwire as one of their “50 Writers You Need to See Read Live,” a kind of breathless, insistent energy and rush, demanding every bit of your attention. Composed closer to the staccato-shorthand of text messaging than the lyric, Pico’s IRL is lively, pulsing and sassy, writing out a long poem that speaks of history and language, pop culture idols and icons, and a heritage that includes his rhetorical declaration, spawned from, it would seem, his background as a member of the Kumeyaay nation: “I survive seven generations / into a post-apocalyptic America / that started 1492. Maybe / you’ll live too?” Pico’s book-length poem reads as incredible immediate, seemingly composed via texts from his (ie: the narrator’s) shared apartment, writing out everything and anything, a busy chatter quickly turning from the seemingly mundane to an almost divine clarity and back in a blink, writing: “America / reclines undying I want America / to know who is still dying / for its sins. I want America taken / alive w/ all my names. I have cocks / in my eyes and songs / in my stars and so Yeah, / I fucking hate you / for wanting to die. / And hate myself for thinking / it might be for the best.” This is a rich and confident text by a poet worth paying attention to; his writing demands it.

“[A] sweaty, summertime poem composed like a long text message” is how the back cover describes Brooklyn, New York poet and editor Tommy Pico’s first full-length poetry title,

IRL

(Birds, LLC, 2016). There is something very clear in the text as to why Pico was named by Flavorwire as one of their “50 Writers You Need to See Read Live,” a kind of breathless, insistent energy and rush, demanding every bit of your attention. Composed closer to the staccato-shorthand of text messaging than the lyric, Pico’s IRL is lively, pulsing and sassy, writing out a long poem that speaks of history and language, pop culture idols and icons, and a heritage that includes his rhetorical declaration, spawned from, it would seem, his background as a member of the Kumeyaay nation: “I survive seven generations / into a post-apocalyptic America / that started 1492. Maybe / you’ll live too?” Pico’s book-length poem reads as incredible immediate, seemingly composed via texts from his (ie: the narrator’s) shared apartment, writing out everything and anything, a busy chatter quickly turning from the seemingly mundane to an almost divine clarity and back in a blink, writing: “America / reclines undying I want America / to know who is still dying / for its sins. I want America taken / alive w/ all my names. I have cocks / in my eyes and songs / in my stars and so Yeah, / I fucking hate you / for wanting to die. / And hate myself for thinking / it might be for the best.” This is a rich and confident text by a poet worth paying attention to; his writing demands it.Boundariesaren’t cages. Meteris a fine flute.But maybe nobody wantsto hear you. Maybeyou are just an asshole.

Published on September 08, 2016 05:31

September 7, 2016

Hoa Nguyen, Violet Energy Ingots

I DIDN’T KNOW

I didn’t know my milk could return racing

to save the orphan babythis morning with ghosts

minor men and shookthe tricky omnivorous bandit

before it could bite againTruck exhaust enters the house

One hydrangea flower and leaves gust in the wind

on “my” side of the fence (stolen)The smooth cup is upheld by a brown

hand as if to say Today is the 70th anniversary

of the bombing of Hiroshima

New from Toronto poet, editor and teacher Hoa Nguyen [see my 2012 profile on her here] is the poetry collection

Violet Energy Ingots

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2016), her first full-length collection since her selected/collected poems, Red Juice: Poems 1998 – 2008 (Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2014) [see my review of such here]. For those keeping score, it’s been four years since the appearance of a new full-length collection of poems by Nguyen—the poems from her chapbook TELLS OF THE CRACKLING(Brooklyn NY: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2015) are included here—back to her

As Long As Trees Last

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2012) [see my review of such here], and Violet Energy Ingots continues her work in the small, personal moment, presenting a series of narratives stiched together in coherent lyric collages of halting breaths, pauses and precise descriptions. As she writes in the poem “Torn”: “To be original is to arise / from a novel origin?”

New from Toronto poet, editor and teacher Hoa Nguyen [see my 2012 profile on her here] is the poetry collection

Violet Energy Ingots

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2016), her first full-length collection since her selected/collected poems, Red Juice: Poems 1998 – 2008 (Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2014) [see my review of such here]. For those keeping score, it’s been four years since the appearance of a new full-length collection of poems by Nguyen—the poems from her chapbook TELLS OF THE CRACKLING(Brooklyn NY: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2015) are included here—back to her

As Long As Trees Last

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2012) [see my review of such here], and Violet Energy Ingots continues her work in the small, personal moment, presenting a series of narratives stiched together in coherent lyric collages of halting breaths, pauses and precise descriptions. As she writes in the poem “Torn”: “To be original is to arise / from a novel origin?”The short lyrics that make up Nguyen’s Violet Energy Ingots quilt together into a sustained conversation around pop culture, history, domestic matters and other concerns both large and small that in her hands become intimate, whether referencing the 70thanniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, Anna Karenina, the song “Judy in Disguise,” Toronto trees, motherhood, the poet Philip Whalen or the colour red. To preface a recent interview with Nguyen posted online at The Walrus, Toronto poet and critic Michael Prior wrote that:

Her poems often use carefully juxtaposed phrases—images, fragments of dialogue, puns—in order to reveal the power structures and ideologies embedded in the seemingly most innocuous of comments and objects. Accordingly, Nguyen’s poetics are attentive to what she calls “the constellations of influences and community.” Nguyen’s phrase captures the striking allusiveness of her own work—in the first twenty or so pages of Violet Energy Ingots, the reader encounters 1960s song lyrics, Hellenic furies, an Egyptian pharaoh, Jane Fonda, and US poet Jack Spicer among many other literary and cultural figures past and present.

Published on September 07, 2016 05:31

September 6, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Roberto Montes

Roberto Montes is the author of

I DON'T KNOW DO YOU

, named one of the Best Books of 2014 by NPR and a finalist for the 2014 Thom Gunn Award for Gay Poetry from The Publishing Triangle. His poetry has appeared in

The Volta

,

Guernica

, The Literary Review, Whiskey Island, and elsewhere. A new chapbook, GRIEVANCES, is forthcoming from the Atlas Review TAR chapbook series.

Roberto Montes is the author of

I DON'T KNOW DO YOU

, named one of the Best Books of 2014 by NPR and a finalist for the 2014 Thom Gunn Award for Gay Poetry from The Publishing Triangle. His poetry has appeared in

The Volta

,

Guernica

, The Literary Review, Whiskey Island, and elsewhere. A new chapbook, GRIEVANCES, is forthcoming from the Atlas Review TAR chapbook series.How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?Publishing has so little to do with poetry it is important to undergo it every once in a while. I don’t mean this to sound negative; it was mostly a positive experience for me. But there is so much push and clamor for publication in the culture of MFA’s and fellowships that we never have any time to discuss what it actually means. Both for the work and for the poet. What do you gain and what do you lose? The most concrete thing I gained was the muted respect of my psychiatrist after my book showed up on the NPR end of the year list. A person stands to lose a lot if they allow that kind of valuation to swallow them. I’ve seen poets win an award or get a publication and then begin chasing that same kind of success by reproducing the works that got them there. Some people call this ‘finding your voice’ but, in my opinion, the voice you find in those situations is rarely your own.

How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?By accident! I took an introductory poetry workshop in undergrad taught by the amazing poet Rebecca Morgan Frank. My original concentration was fiction but after that class I switched to poetry. It helped that my fiction was terrible.

How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?You’ve hit a sore spot. For the first book all my poems came in short bursts nearly fully-formed. Over time I began to write longer, sprawling pieces that drag on for days. I tend to edit as I write so it’s sort of a back-and-forth as the lines go on. It is like a colony of ants building a bridge with their bodies. I oftentimes have no idea where a poem is going until I hit the other shore. And then, just like that, it’s over.

Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?In the past I’ve stumbled upon engines more so than single poems. For example, I became infatuated with spam for a period of time—the way they so expertly prey on our insecurities and clotted hopes—and that led to 30 or so poems. In the first book I happened upon the phrase “One way to be a person is” and that led to a few poems. I’m in an awkward in-between, really. I write series that are too short to be books but too numerous to be one-offs.

Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?I am a ham so I love reading. I do admit, however, that when I read I view myself as first and foremost a performer of sorts. It’s not that I think “serious” poetry can’t be shared in a public space but when I always choose poems to read that I think are engaging and can be performed. It is strange because I have a few poems that I genuinely like but will never read because I don’t think they’re suitable to that environment. The written word plays with a different affective space than something spoken. I think both are interesting and have their merits. But they should not be confused.

Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?I do not think poetry can answer anything. Not to be gooey, but, I think poetry operates in purely in an interrogative affective space. I try not to engage in theoretical concerns because I believe that can lead to a strangling of that space in a way that helps no one. The closest thing that I have to a theoretical concern is the belief that good poetry exists in such a way that it saps power from the powerful and gives power to the powerless.

What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?The writer should write. I privilege poetry over the poet so I don’t concern myself so much with how an individual should act or what role they should occupy. As a rule, though, whatever role a poet feels they should have in the world is probably the wrong one and I encourage them to avoid it at all costs.

Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?A good editor is invaluable. The further from you they are aesthetically the better. When you are reduced to pleading “but that’s not what I was going for” it really forces you to view the work in a manner you wouldn’t have if your editor just ‘got it’. Sometimes I think I use aesthetics as an excuse for laziness or to enter the poem and ham it up. Someone who doesn’t share your inclinations can bend your poems in really interesting and necessary ways.

What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)? “Another poet’s success does not take from your own. So fuck it.” (paraphrasing)

What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?I write in-transit, mostly. I used to have an hour train ride to and from work every day that I dedicated to writing and editing. It was amazing! I recently moved, however, and my commute is much shorter so I’m having difficulty writing as much as I used to. Writing is such a superstitious act it is so strenuous when you are forced to change your rituals!

When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration? Fear.

What fragrance reminds you of home?There’s a particular dish my grandmother would make: picadillo. My partner and I are vegetarian so when we make it we use veggie ground beef but, somehow, the smell of the spices still rings true.

David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?I have a great interest in the lives of mathematicians. I feel a strong connection with those who work for years to discover the mechanics of reality using only inscrutable symbols.

What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?A few poets who invigorate and inspire me: Jenny Zhang, Natalie Eilbert, Wendy Xu, Sara Woods, Joshua Jennifer Espinoza, Eduardo Corral, Carrie Lorig, & Rigoberto Gonzalez.

What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?Realize myself in such a way that, when I’m done, I can simply unlace my body of existence.

If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?I have no idea. From a very early age writing was something that I bent toward. I cannot imagine an existence other than the one I have. Sometimes I imagine what it might be like for people who don’t have poetry but then I freak the hell out and am forced to imagine something else.

What made you write, as opposed to doing something else? ^ ^ I never had a choice.

What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film? The Feel Trio by Fred Moten helped me greatly during a difficult time.

What are you currently working on? I am working on a full-length manuscript and editing a chapbook, Grievances.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on September 06, 2016 05:31

September 5, 2016

Jordan Scott, Night & Ox

you’re smallyour smallso cry’sinky stampedeblotchyin beecostumein glyph kitchenon glottis islandstuddedsturgeonweighsdashberrymirror drumdecimalcosmoglottalmudstone, lookborealisit’s crystallinestarboard boyformmetadata toneboxslipsalmonoidheavinessalwaysdignityunlikedcub

After the poetry collections silt (Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2005) and blert (Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2008), as well as the collaborative Decomp (with Stephen Collis; Coach House Books, 2013) [see my review of such here], comes Vancouver poet Jordan Scott’s Night & Ox (Coach House Books, 2016), a book composed as a lengthy, single, extended poem. As he writes in his afterword, “&”:

Night & Ox were written during the winter of 2013 and the summer of 2016. During this time, the European Space Agency’s Rosetta spacecraft caught up with Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko and dropped the Philae lander onto its surface. The lander bounced across the comet’s terrain and settled somewhere on its duck-shaped head, where it finally received enough sunlight to emerge from hibernation and contact the Rosetta spacecraft. I first saw the images taken by Rosetta’s navigation camera when the comet reached perihelion, its closest approach to the sun. The first images I saw were of a comet deep in shadow surrounded by crisscrossing sunlit jets of gas and dust; a comet’s silhouetted underbelly surrounded by faint traces of debris; grainy images of a two-lobed comet uneven in gravity and surrounded by a matrix of stars, particles and a halo of camera noise. Within the intervals of these transmissions between Rosetta and Philae, I was learning to be a father. The same sunlight that woke Philae covered the backyard and kitchen and my two sons at play in our home on Trinity Street, Vancouver, where I wrote most of Night & Ox. These images taken by Rosetta became the mood lighting of a poem that constantly defied containment. When I started the poem, I was just beginning to learn about my boys. I was, as Tom Raworth writes, ‘alive and in love’ and both completely adrift in this intimacy and completely contained by the rituals of parenting: the bedtime, the snacktime, the naptime, the shit. I wrote Night & Ox within these rituals, typing the first lines of the poem with one hand, holding my son Sacha as he slept. With his form attached to mine, the lines took on a shallow and hurried breathing, one of restlessness and the infinitesimal movements of a body bound tightly to a larger form.

I’m curious about how such a work was composed around and through new considerations of fatherhood, of children; on the surface, this is immediately comparable to some of Ottawa poet Jason Christie’s recent poetry, as well as some other recent works: Ottawa poet Monty Reid’s Meditatio Placentae (London ON: Brick Books, 2016) [see my review of such here], Minneapolis poet Chris Martin’s The Falling Down Dance(Coffee House Press, 2015) [see my review of such here], Dallas, Texas poet Farid Matuk’s My Daughter La Chola (Boise ID: Ahsahta Press, 2013) and Dan Thomas-Glass’ Daughters of Your Century (Furniture Press Books, 2014). For some, the shift to new-fatherhood (and new-parenthood, generally) is impossible to not write about [see my own four-part essay on fatherhood here], from the distractions and attentions to the expanded and connecting perspectives upon family, mortality and being (“entrail’s equinox / purring kid sounds / translunar and / clay parsec”), and simply wondering how the whole thing can hold itself together without collapsing. From a poet highly aware of breath and stammer, Scott’s short, predominantly single-word lines highlight a movement of, as he says, “a shallow and hurried breathing […],” and even include the occasional created compound word, a la Paul Celan, pushing to increase his precision with words that hadn’t yet been built. As he writes: “stutterkiss / in / blithe / scorpion / some / endless / typhoon / spill / I / here / endless / obedience / forms / sight / wounding / longer / I / wait / for / little / things / to / cross / a / threshold […].” Scott’s poem-structure is even slightly reminiscent (albeit a pared down version) of the rush of American poet Ron Silliman’s Revelator (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2013) [see my review of such here]. With the single, extended poem running left-margined along each page, there is a breathless rush that can’t help itself, one that also focuses highly on each line, pausing and accumulating and quickly moving in a staccato-accumulation that feels, if not endless, certainly ongoing.

I’m curious about how such a work was composed around and through new considerations of fatherhood, of children; on the surface, this is immediately comparable to some of Ottawa poet Jason Christie’s recent poetry, as well as some other recent works: Ottawa poet Monty Reid’s Meditatio Placentae (London ON: Brick Books, 2016) [see my review of such here], Minneapolis poet Chris Martin’s The Falling Down Dance(Coffee House Press, 2015) [see my review of such here], Dallas, Texas poet Farid Matuk’s My Daughter La Chola (Boise ID: Ahsahta Press, 2013) and Dan Thomas-Glass’ Daughters of Your Century (Furniture Press Books, 2014). For some, the shift to new-fatherhood (and new-parenthood, generally) is impossible to not write about [see my own four-part essay on fatherhood here], from the distractions and attentions to the expanded and connecting perspectives upon family, mortality and being (“entrail’s equinox / purring kid sounds / translunar and / clay parsec”), and simply wondering how the whole thing can hold itself together without collapsing. From a poet highly aware of breath and stammer, Scott’s short, predominantly single-word lines highlight a movement of, as he says, “a shallow and hurried breathing […],” and even include the occasional created compound word, a la Paul Celan, pushing to increase his precision with words that hadn’t yet been built. As he writes: “stutterkiss / in / blithe / scorpion / some / endless / typhoon / spill / I / here / endless / obedience / forms / sight / wounding / longer / I / wait / for / little / things / to / cross / a / threshold […].” Scott’s poem-structure is even slightly reminiscent (albeit a pared down version) of the rush of American poet Ron Silliman’s Revelator (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2013) [see my review of such here]. With the single, extended poem running left-margined along each page, there is a breathless rush that can’t help itself, one that also focuses highly on each line, pausing and accumulating and quickly moving in a staccato-accumulation that feels, if not endless, certainly ongoing.

Published on September 05, 2016 05:31

September 4, 2016

12 or 20 (small press) questions with Catriona Wright (and Emma Dolan) on Desert Pets Press

Desert Pets Press

was founded in 2015 by illustrator Emma Dolan and writer Catriona Wright. Based out of Toronto, Ontario, the press publishes limited edition poetry and prose chapbooks and strives to combine exciting contemporary writing with innovative design.

Desert Pets Press

was founded in 2015 by illustrator Emma Dolan and writer Catriona Wright. Based out of Toronto, Ontario, the press publishes limited edition poetry and prose chapbooks and strives to combine exciting contemporary writing with innovative design.Catriona Wright is a writer, editor, and teacher. Her poetry has appeared in Prism International, Prairie Fire, Arc Poetry Magazine, Rusty Toque and Best Canadian Poetry 2015 (Tightrope Books). She is the poetry editor at The Puritan and a co-founder of Desert Pets Press. @CatTreeWright

Emma Dolan is a Toronto-based designer and illustrator. In 2015 she co-founded Desert Pets Press. @emmadarkandweird

1 – When did Desert Pets Press first start? How have your original goals as a publisher shifted since you started, if at all? And what have you learned through the process?My friend Emma and I discussed starting a chapbook press several years ago when I was enrolled in the MA in Creative Writing at the University of Toronto and she was working as a book cover designer. We’ve been friends for over 15 years, and we wanted to collaborate on something creative together. But then we procrastinated for a long time (including many months of brainstorming a name). Finally we got our act together in early 2015, and Desert Pets Press was born!

We’ve published four books so far over two seasons (Fall 2015 and Spring 2016). Our original goal was to have fun, publish people we like, and make beautiful books, and I don’t see those goals changing any time soon.

We’ve learned a lot through the process! I’m also the poetry editor at The Puritan, where I work with a big team of people who do the publicity, grant writing, event organizing etc., so it was eye-opening to be responsible for everything ourselves. The thing that amazes me most is the sheer number of emails we’ve sent. So. Many. Emails.

2 – What first brought you to publishing?I still consider myself primarily a writer, so I came to publishing from that perspective. I first became aware of the small press world in Ottawa when I took a workshop with you at Collected Works in 2007, and when I moved to Toronto, I learned about many other presses, both large and small. I was a spectator/consumer for many years, and I eventually found the courage (and the right partner) to participate more actively.

After completing a literature degree at Queen’s, Emma enrolled in the Book and Magazine Publishing Program at Centennial, so she was exposed to that side of things. She worked for several publishers before going freelance as a book designer and illustrator.

3 – What do you consider the role and responsibilities, if any, of small publishing?We can only speak for ourselves, but for us it’s all about putting out work we’re proud of and that we’ve enjoyed producing. We love to support other presses by collaborating and attending their events, but at the end of the day, putting the work in and getting the books out into the world is our biggest focus.

4 – What do you see your press doing that no one else is?I think it’s a bit unusual to have an artist and a writer working together. Emma has done an exceptional job with the design (covers, interior illustrations, etc.). We were inspired by two other small presses, Ferno House Press and Odourless Press, both of which are no longer publishing new books. I’d like to think we’ve done justice to their strong emphasis on design.

5 – What do you see as the most effective way to get new chapbooks out into the world?I have no idea! We’re still new to this. We’ve definitely found that the majority of our sales have occurred at launches, but our Etsy store has been active, as well. Toronto boutiques and independent bookstores have also been taking notice of chapbooks and independent publications and are carrying them in their stores, and we have some chapbooks for sale at TKVO on Dundas and Type Bookstore on Queen. Chapbook creation is a collaborative process, so we also rely on our authors to spread the word through social media and their personal networks.

6 – How involved an editor are you? Do you dig deep into line edits, or do you prefer more of a light touch?I’m still finding my editing rhythm, and so far my approach has depended on the book. For example, E Martin Nolan’s chapbook had already been heavily edited by Bardia Sinaee before it came our way. I was more involved in Michelle Brown’s editing process, but I’m also in a poetry workshop with her, so some of that editing came in the form of earlier workshop comments. Before we start on a new project, I like to ask writers about their expectations to get a sense of what they want from me, and then I go from there.

7 – How do your books get distributed? What are your usual print runs?We sell most of our books at launches, but we’ve sold several at Meet the Presses and the Ottawa Small Press Fair, and we’re lucky enough to have some on the shelves at Type bookstore. We also have an Etsy store, which has been quite successful this season.

For our first season of books, we did a 50 book print run, but we sold out almost immediately. This time we did 100 of each book.

8 – How many other people are involved with editing or production? Do you work with other editors, and if so, how effective do you find it? What are the benefits, drawbacks?As I mentioned before, Bardia Sinaee edited most of E Martin Nolan’s book, but that was an unusual circumstance, and we don’t generally work with other editors. We get our books printed at Colour Code, a great local printer and a press themselves, and we’ve been very pleased with their work.

9– How has being an editor/publisher changed the way you think about your own writing?I’m not sure it’s changed the way I think about my writing, but it’s certainly increased my respect for publishers and all the tough work they do. Before Desert Pets Press I didn’t fully realize how much attention has to go into each stage of the process (editing, layout, design, etc.), so I hope I’ll be more understanding when my own books are going through production.

9– How has being an editor/publisher changed the way you think about your own writing?I’m not sure it’s changed the way I think about my writing, but it’s certainly increased my respect for publishers and all the tough work they do. Before Desert Pets Press I didn’t fully realize how much attention has to go into each stage of the process (editing, layout, design, etc.), so I hope I’ll be more understanding when my own books are going through production. 10– How do you approach the idea of publishing your own writing? Some, such as Gary Geddes when he still ran Cormorant, refused such, yet various Coach House Press’ editors had titles during their tenures as editors for the press, including Victor Coleman and bpNichol. What do you think of the arguments for or against, or do you see the whole question as irrelevant?Still working out my thoughts on this question! I haven’t published my own work yet and have no plans to do so soon (but a part of me would love to have Emma create some illustrations for my poems, so we’ll see).

11– How do you see Desert Pets Press evolving?We’re content at the moment, but we’ll probably try to start publishing more books a season (3 rather than 2), and we’d like to start printing some broadsides. We’re hoping to attend more book fairs (Expozine, Brooklyn Art Fair, etc), as well. I don’t anticipate Desert Pets Press ever expanding into a full trade press. We’d like to keep our scale small and our ideas big.

12– What, as a publisher, are you most proud of accomplishing? What do you think people have overlooked about your publications? What is your biggest frustration?We’re still babies in the publishing biz so just getting our chapbooks into the world has been our greatest accomplishment. Blissfully free of bitterness and frustration…perhaps that happens later.

13– Who were your early publishing models when starting out?As I mentioned earlier, Ferno House Press and Odourless Press were our main models. They both created some beautiful, intelligent books. Spencer Gordon and Bardia Sinaee have also been helpful sources of information about making and distributing the books.

14– How does Desert Pets Press work to engage with your immediate literary community, and community at large? What journals or presses do you see Desert Pets Press in dialogue with? How important do you see those dialogues, those conversations?We collaborate with several other small presses. In the spring, we co-ran our launch with the excellent Emergency Response Unit, and we’re hoping to work with Metatron and words (on) pages on some events/readings/launches in the next year. I’m also an editor at The Puritan, so we have close ties with those folks.

These connections are absolutely vital to our existence, and we support other presses by attending/publicizing events and trading/buying books. We got into publishing because we wanted to create something for a community, and we are continually inspired by the ingenuity of the Canadian literary world.

15– Do you hold regular or occasional readings or launches? How important do you see public readings and other events?We’ve held two launches/readings so far, both at Reunion Island Coffee, and they were magical. It’s so gratifying to see the authors read and share their work. Public readings are important for publicity and sales, but even more important for celebratory purposes. No one is making any money from these books. It’s a gift economy, an exchange of creative energy, and we want to nurture this connection by bringing people together in person.

16– How do you utilize the internet, if at all, to further your goals?Selling online has been a big help because it allows us to reach more people. We’ve had lots of sales all over Canada and the US (and even New Zealand!). Posting on social media has been our main method for getting the word out about our projects and events and getting people excited about what we’re doing.

16– How do you utilize the internet, if at all, to further your goals?Selling online has been a big help because it allows us to reach more people. We’ve had lots of sales all over Canada and the US (and even New Zealand!). Posting on social media has been our main method for getting the word out about our projects and events and getting people excited about what we’re doing.17– Do you take submissions? If so, what aren’t you looking for?We’re not taking submissions at the moment.

18– Tell me about three of your most recent titles, and why they’re special.Moon Bones/Silver Tooth by Brooke Lockyer is our first fiction chapbook. A flip book with two covers/stories, this chapbook delves into the dark heart of childhood. The writing is compassionate, sad, subtle, and gorgeous.

Foreign Experts Building by Michelle Brown is silly on the surface, but don’t let that fool you. These poems are anxious and death-obsessed. Plus, the chapbook features some gorgeous animal illustrations.

Poems from Still by E Martin Nolan features spare, haunting poems about two post-industrial cities, New Orleans and Detroit. These poems will also appear in E Martin Nolan’s full-length collection, which is coming out in fall 2017 with Invisible Publishing.

12 or 20 (small press) questions;

Published on September 04, 2016 05:31

September 3, 2016

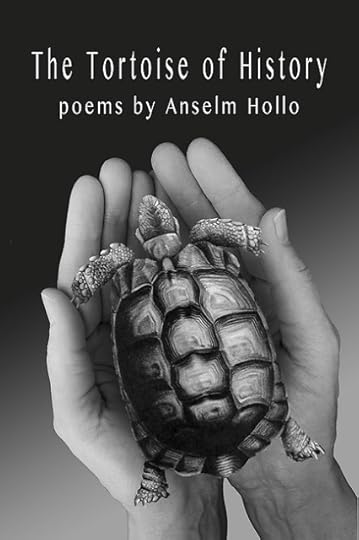

Anselm Hollo, The Tortoise of History

The Way They Pop Up Now

late in this lifethe dead and the living

Technicoloror black and white

different parts of the brainbegin talking to each other

small children reappearand now they’re either dead

or alive as film directorsrecord producers high tech designers

but some ancients are still present tooeven more ancients than this brain life

looks out the windowthinks squirrels are not very contemplative

but the cats watching them are

There is a sweetness to the foreword by Anselm Hollo’s widow, Jane Dalrymple-Hollo, that opens the posthumous volume The Tortoise of History: poems by Anselm Hollo (Coffee House Press, 2016):

Could Anselm have possibly foretoldthat The Tortoise of History, this peculiar compilation of old and newmusings, revisitations, letters to past and future, love notes to friends—and to me

was an inevitable foreshadowing of this day, when I, his Janeywould stop the endless fuss, unplug the phone, sit quietly for 20 minutes,

and then settle into his chair, in our kitchenand read thisbook—aloud, in his cadenceand reallytake in

this “message in a bottle”?

I’ll admit, my reading of the late poet and translator Anselm Hollo’s extensive work isn’t nearly as complete as it should be. My engagements with his more than forty titles is limited to but four works: the chapbook Tumbleweed (Weed Flower Press, 1968) (generously gifted from the publisher, Nelson Ball), and larger trade collections

Maya

(Cape Goliard Press, 1970) (generously gifted by Nicky Drumbolis),

Pick Up The House

(Coffee House Press, 1986) and

Notes on the Possibilities and Attractions of Existence: Selected Poems 1965–2000

(Coffee House Press, 2001), meaning that my take on this posthumous volume is limited (at least, based upon what it could be). How does one easily assess a potential “last volume” by a writer with such a lengthy career? In the poems collection in

The Tortoise of History

, Hollo swivels his short meditations on small turns in short lyrics and the occasional longer sequence, composing staccato moment after moment in a first-person cadence that runs through the length and breadth of what I do know of his work, such as the poem “Crocus,” that reads:

I’ll admit, my reading of the late poet and translator Anselm Hollo’s extensive work isn’t nearly as complete as it should be. My engagements with his more than forty titles is limited to but four works: the chapbook Tumbleweed (Weed Flower Press, 1968) (generously gifted from the publisher, Nelson Ball), and larger trade collections

Maya

(Cape Goliard Press, 1970) (generously gifted by Nicky Drumbolis),

Pick Up The House

(Coffee House Press, 1986) and

Notes on the Possibilities and Attractions of Existence: Selected Poems 1965–2000

(Coffee House Press, 2001), meaning that my take on this posthumous volume is limited (at least, based upon what it could be). How does one easily assess a potential “last volume” by a writer with such a lengthy career? In the poems collection in

The Tortoise of History

, Hollo swivels his short meditations on small turns in short lyrics and the occasional longer sequence, composing staccato moment after moment in a first-person cadence that runs through the length and breadth of what I do know of his work, such as the poem “Crocus,” that reads:Hello yellowcrocus she sayssnaps a picture looks away turns to seethe deer that later swallows the crocusoh well Springwill spring

The collection wraps up with an essay on the Greek poet Hipponax, via William Carlos Williams, and Hollo’s own take on the “halting meter” he discusses, through a sequence of poems. As Hollo opens his short essay:

William Carlos Williams ends Book 1 of his Paterson (New Directions 1992, p. 40) with a quote from John Addington Symond’s two-volume Studies of the Greek Poets, prefacing it with an “N.B.:”

“In order apparently to bring the meter still more within the sphere of prose and common speech, Hipponax ended his iambics with a spondee or a trochee instead of an iambus, doing thus the utmost violence to the rhythmical structure. These deformed and mutilated verses were called choliambi, lame or limping iambics. They communicated a curious crustiness to the style. These choliambi are in poetry what the dwarf or cripple is to human nature. Here again, by their acceptance of this halting meter, the Greeks displayed their acute aesthetic sense of propriety, recognizing the harmony which subsists between crabbed verses and the distorted subjects with which they dealt—the vices and perversions of humanity—as well as their agreement with the snarling spirit of the satirist.”

There is an echo of this quote, one that Williams found relevant to his search for a new measure, in the final lines of Book 5, the last complete installment of Paterson(p. 236):

We know nothing and can know nothing but the dance, to dance to a measure contrapunctally, Satyrically, the tragic foot.

Published on September 03, 2016 05:31

September 2, 2016

Touch the Donkey : back issue sale,

JOIN THE CROWD! Until September 15, 2016, why not pick up any five of the first ten issues of the quarterly Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] for only $20? (plus shipping, of course)

JOIN THE CROWD! Until September 15, 2016, why not pick up any five of the first ten issues of the quarterly Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] for only $20? (plus shipping, of course)Touch the Donkey #1 : new work by Camille Martin, Eric Baus, Hailey Higdon, rob mclennan, Norma Cole, Elizabeth Robinson, Rachel Moritz, Gil McElroy and Pattie McCarthy. Touch the Donkey #2 : new work by Julie Carr, Catherine Wagner, Susanne Dyckman, Pearl Pirie, David Peter Clark, Susan Holbrook, Phil Hall and Robert Swereda. Touch the Donkey #3 : new work by Gil McElroy, j/j hastain, derek beaulieu, Megan Kaminski, Roland Prevost, Emily Ursuliak, Susan Briante and D.G. Jones. Touch the Donkey #4 : new work by Maureen Alsop, Stan Rogal, Laura Mullen, Jessica Smith, Lise Downe, Kirsten Kaschock, Gary Barwin, Chris Turnbull, Nikki Sheppy, Lisa Jarnot. Touch the Donkey #5 : new work by Edward Smallfield, Rob Manery, Elizabeth Robinson, lary timewell, nathan dueck, Paige Taggart, ryan fitzpatrick, Christine McNair. Touch the Donkey #6 : new work by Lola Lemire Tostevin, D.G. Jones, Aaron Tucker, Deborah Poe, Jason Christie, Jeffrey Jullich, Jennifer Krovonet, Kayla Czaga, Jordan Abel. Touch the Donkey #7 : new work by Stan Rogal, Helen Hajnoczky, Kathryn MacLeod, Shannon Maguire, Sarah Mangold, Amish Trivedi, Suzanne Zelazo. Touch the Donkey #8 : new work by Mary Kasimor, Billy Mavreas, damian lopes, Pete Smith, Sonnet L’Abbé, Katie L. Price, a rawlings, Gil McElroy. Touch the Donkey #9 : new work by Stephen Collis, Laura Sims, Paul Zits, Eric Schmaltz, Gregory Betts, Anne Boyer, François Turcot (trans. Erín Moure, Sarah Cook. Touch the Donkey #10 : new work by Meredith Quartermain, Mathew Timmons, Luke Kennard, Shane Rhodes, Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Amanda Earl.

To order, send cheques (add $1 for postage; outside Canada, add $2) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9 or paypal at www.robmclennan.blogspot.com

Be sure to check out the Touch the Donkey blog for some sixty interviews (and counting) with a variety of contributors!

And of course, subscriptions for future (quarterly) issues are available as well! Five issues for $30 (CAN/US). Watch for the issue #11, due to land October 15th!

And check out our Facebook group for ongoing interview and issue notifications!

https://www.facebook.com/groups/664316740327618/

Touch the Donkey. Everywhere you want to be.

http://www.touchthedonkey.blogspot.ca/

Published on September 02, 2016 05:31