Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 85

July 4, 2023

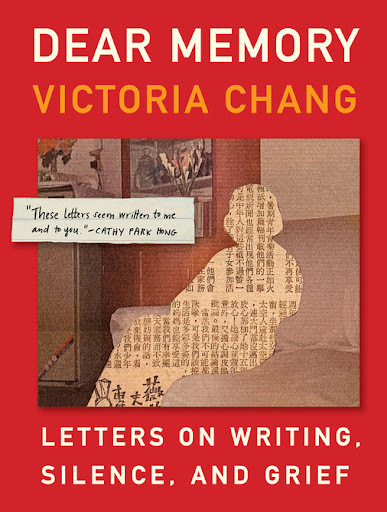

Victoria Chang, Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief

I wonder whether memoryis different for immigrants, for people who leave so much behind. Memory isn’t somethingthat blooms but something that bleeds internally, something to be stopped. Memoryhides because it isn’t useful. Not money, a car, a diploma, a job. I wonder ifmemory for you was a color.

When we say thatsomething takes place, we imply that memory is associated with a physicallocation, as Paul Ricoeur states. But what happens when memory’s place of origindisappears? (“Dear Mother,”)

LatelyI’ve been going through Los Angeles-based poet Victoria Chang’s strikingnon-fiction project, the stunning and deeply felt, deeply intimate

Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief

(Minneapolis MN: MilkweedEditions, 2021), a book of memory, history and mentors. Interspersed with collagedarchival photographs and other documents, the collection is composed as asequence of letters individually directed to intimates such as her lateparents, childhood friends, acquaintances and former teachers, as well as to herdaughter. Dear Memory follows Chang’s poetry collections Circle (SouthernIllinois University Press, 2005),

Salvinia Molesta

(University of GeorgiaPress, 2008),

The Boss

(McSweeney’s, 2013) [see my review of such here],

Barbie Chang

(Copper Canyon, 2017) [see my review of such here] and

Obit

(Copper Canyon, 2020) [see my Griffin Prize-shortlist interview with her here],although I’m realizing how far behind I am on her work, having missed

TheTrees Witness Everything

(Copper Canyon, 2022), with a further poetrycollection forthcoming in 2024 with Farrar, Straus & Giroux: With MyBack to the World.

LatelyI’ve been going through Los Angeles-based poet Victoria Chang’s strikingnon-fiction project, the stunning and deeply felt, deeply intimate

Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief

(Minneapolis MN: MilkweedEditions, 2021), a book of memory, history and mentors. Interspersed with collagedarchival photographs and other documents, the collection is composed as asequence of letters individually directed to intimates such as her lateparents, childhood friends, acquaintances and former teachers, as well as to herdaughter. Dear Memory follows Chang’s poetry collections Circle (SouthernIllinois University Press, 2005),

Salvinia Molesta

(University of GeorgiaPress, 2008),

The Boss

(McSweeney’s, 2013) [see my review of such here],

Barbie Chang

(Copper Canyon, 2017) [see my review of such here] and

Obit

(Copper Canyon, 2020) [see my Griffin Prize-shortlist interview with her here],although I’m realizing how far behind I am on her work, having missed

TheTrees Witness Everything

(Copper Canyon, 2022), with a further poetrycollection forthcoming in 2024 with Farrar, Straus & Giroux: With MyBack to the World.Thisis a book of contemplation, recollection and reconciliation, as Chang offers thefluidity of a combined book-length essay and memoir through the form of journaledand unsent letters. There is such an intimacy and an openness to the way sheholds the book’s form, one that predates, arguably, even the novel; think of bookssuch as The Pillow Book (1002) by Sei Shōnagon, or even Bram Stoker’soriginal Dracula (1897). The back-and-forth of recollection in Chang’s DearMemory are even reminiscent to what Kristjana Gunnars wrote about in hernovella, The Prowler (Red Deer College Press, 1989): “That the past resemblesa deck of cards. Certain scenes are given. They are not scenes the remembererchooses, but simply a deck that is given. The cards are shuffled whenever agame is played.” Or, as Chang writes, mid-point through the collection: “Now I admirewriters who write with an intimate intensity but also a generous capaciousness.I enjoy reading work that expands while it contracts. Writing made by aninstrument with a microscope on one end and a telescope on the other, leavingsome powder on the page in the form of language.”

Dear Memory writes to and around her immigrant parents,offering her childhood as a foundation for the collection the narrative spreadsinto, through and beyond, including her own ways through thinking and intopoetry. Chang writes of memory as a way to articulate becoming, and anarticulation around writing, around poetry, is as foundational to her as the lostthreads of either of parent’s lives, the sequence of multiple familyrestaurants they ran and the difficulty of being the only child of Asian descentin predominantly white communities. There is such an intimacy to these pieces,one that demands slowness, demands attention. One that is framed around an acknowledgmentof loss, both long past and those losses that are ongoing, but composed in amanner through which to solidify, before those losses slip entirely away. “Memoryis everything,” she writes early on, in a lettet to her mother, “yet it isnothing. Memory is mine, but it is also clinging to the memory of others. Some ofthese others are dead. Or unable to speak, like Father.” Or, as the piece “DearTeacher,” begins:

I stumbled into yourpoetry workshop even though I wasn’t studying poetry. I was one of the fewgraduate students there. I remember you at the head of a long wooden table,presiding, as if your chair were a throne. The room was brown with woodeverywhere. We were knights of poetry. our plates were white sheets of paperfilled with our own flesh. Your words were infinite. They were an entirecountry.

At the end of class, youwrote each student a note. Your note said my poetry had become poems out ofpoetry and that my poems had begun to strike forward to the possibility…You also wrote that you wished I had made my voice more present in class andthat my form of articulation was far from shy. You told me to call totalk about next semester.

July 3, 2023

Jerome Sala, How Much? New and Selected Poems

Look Slimmer Instantly!

Read this poem.

WhileI will revive my usual complaint about selecteds produced sansintroduction-for-context (an oversight I consider nearly criminal), there issomething almost preferable to experiencing American poet Jerome Sala’sintroduction-less

How Much? New and Selected Poems

(Beacon NY: NYQBooks, 2022). Having read poems here and there of his over the years, this isthe first collection I’ve explored, and it includes selections from his priorfull-length titles I Am Not a Juvenile Delinquent (STARE Press, 1985), TheTrip (The Highlander Press, 1987),

Raw Deal: New and Selected Poems,1980-94

(Jensen/Daniels, 1994), Look Slimmer Instantly (Soft SkullPress, 2005),

The Cheapskates

(Lunar Chandelier Press, 2014) and Corporations Are People, Too! (NYQ Books, 2017), as well as a healthy opening section ofnewer work, and a closing section of poems produced prior to that firstpublished collection. It is interesting that the book is structured chronologicallyin reverse, the opposite of how selecteds are often compiled, offering the newestpoems at the end. Whoever put this selection together (another frustration I havewith certain selecteds; whether the author, an internal or external editor withthe press, it should be offered somewhere as a credit) chose for the reader tocatch a sense of where Sala the poet has been most recently, before launchingfurther back into that panorama of his publishing history. As the back coveroffers, this collection “offers a panoramic view of a poet whose work has oftenbeen a cult-pleasure until now. Spanning Sala’s early years as a punkperformance poet in Chicago to his career as a copywriter/Creative Director inNew York City, these poems offer satiric insights from the ‘belly of the beast’of commercial and pop culture.”

WhileI will revive my usual complaint about selecteds produced sansintroduction-for-context (an oversight I consider nearly criminal), there issomething almost preferable to experiencing American poet Jerome Sala’sintroduction-less

How Much? New and Selected Poems

(Beacon NY: NYQBooks, 2022). Having read poems here and there of his over the years, this isthe first collection I’ve explored, and it includes selections from his priorfull-length titles I Am Not a Juvenile Delinquent (STARE Press, 1985), TheTrip (The Highlander Press, 1987),

Raw Deal: New and Selected Poems,1980-94

(Jensen/Daniels, 1994), Look Slimmer Instantly (Soft SkullPress, 2005),

The Cheapskates

(Lunar Chandelier Press, 2014) and Corporations Are People, Too! (NYQ Books, 2017), as well as a healthy opening section ofnewer work, and a closing section of poems produced prior to that firstpublished collection. It is interesting that the book is structured chronologicallyin reverse, the opposite of how selecteds are often compiled, offering the newestpoems at the end. Whoever put this selection together (another frustration I havewith certain selecteds; whether the author, an internal or external editor withthe press, it should be offered somewhere as a credit) chose for the reader tocatch a sense of where Sala the poet has been most recently, before launchingfurther back into that panorama of his publishing history. As the back coveroffers, this collection “offers a panoramic view of a poet whose work has oftenbeen a cult-pleasure until now. Spanning Sala’s early years as a punkperformance poet in Chicago to his career as a copywriter/Creative Director inNew York City, these poems offer satiric insights from the ‘belly of the beast’of commercial and pop culture.”The People on TV

The people on televisionmove so slowly.

They walk through bighouses and stare into wide spaces

where meaningfuldiscussions appear. Animated clouds

of talk, stirred bylaughter, tears, anger, and catharsis

produce thunderstorms onthe plush rugs

where they roll aroundwith each other,

disrobing in awkwardclenches, wrestling

with the narrativesfoisted upon them by invisible

characters off screen,who theorize our desires

and write to them. youcan’t help but feel sorry

for those earnest, twodimensional souls, who struggle

mightily with thestereotypes prescribed to their situation

like drugs that enhancesocially desirable dialog.

For in every episode,even as they bask in their own beauty,

you feel we make them anxious,as if we were problem children

whose hang-ups theirmasters could only hope to solve.

Thereare elements of Sala’s work that remind of Canadian poets Stuart Ross or Gary Barwin: imagine either of those poets writing corporate-speak, and with farmore swagger, confident or foolhardy enough to be brightly coloured in suchswagger-subtlety, of course. If Jerome Sala had appeared in Toronto orHamilton, say, over Chicago, I could easily have seen his work alongside thatof Alice Burdick and Lance La Rocque, or even that of Victor Coleman or the late Daniel Jones, offering highly literate and literary poems that might bestbe experienced from a corner of some dark music venue, listening to the authorread aloud between sets of local bands. There’s a propulsion behind these poemsthat offers observation, documentation, critique and a kind of first-personreportage from a slightly surreal perspective of shifting soil. The ground willgive way, but Sala manages to hold on. His poems capture culture, politics andcultural movements through language, whether across tone, subject or speech,and probes best when swirling across all simultaneously. His gestures requireattention, whether screamed from a stage or as a whisper; his poems don’t simplyrequire or demand one’s attention but provide openings for one’s attention tofall into. “The map to be redrawn grows stubborn,” he writes, to open the poem “TheGlobe Fell Off the Table,” “refusing the clumsy crayon-holding fingers / of moronicmanipulators. / Things stay as they were the day before / yesterday began. Forgetabout tomorrow: / you can’t hit that pitch.”

Lately,I’ve been reexperiencing (through reading aloud to our nine-year-old) the “witand comic grace” of Winnipeg writer David Arnason’s short story collection The Dragon and the Dry Goods Princess (Winnipeg MB: Turnstone Press, 1994), andthere are echoes, too, I can find between these two volumes, in how Salaapproaches elements of humour and narrative via the prose poem, as the firststanza of the poem “The Fakir” reads:

I am not Elvis Presley, yet I am in love with a woman wholoves a man who thinks he is Elvis Presley. That man is me. But if she knows I don’treally think I am Elvis Presley, she will no longer love me. She loves the deludedand only them. So, all day long I pretend I am Elvis Presley back from thedead. Like the majority of the people who voted for the postage stamp, I preferthe young Elvis. I myself look more like the older Elvis, as I am middle-agedand gaining weight. But you can see how this makes her love me twice as much,for I am, in her eyes, doubly deluded: on one level I am a mere mortal who thinkshe is Elvis Presley. On another, I am the old Elvis who foolishly thinks he isstill young. I know I am neither. I also know I want her love more than anythingin this world and will do anything to get it.

July 2, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jenny Molberg

Jenny Molberg is theauthor of Marvels of the Invisible (winner of the Berkshire Prize,Tupelo Press, 2017), Refusal (LSU Press, 2020), and The Court of No Record (LSU Press, 2023). Her poems and essays have recently appeared orare forthcoming in Ploughshares, The Cincinnati Review, VIDA,The Missouri Review, The Rumpus, The Adroit Journal, OprahQuarterly, and other publications. She has received fellowships andscholarships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Sewanee WritersConference, Vermont Studio Center, and the Longleaf Writers Conference. Havingearned her MFA from American University and her PhD from the University ofTexas, she is Associate Professor and Chair of Creative Writing at theUniversity of Central Missouri, where she edits Pleiades: Literature inContext. Find her online at jennymolberg.com or on Twitter at @jennymolberg.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

When I was studying for my doctorate, I was honored to winTupelo Press’s Berkshire Prize for Marvels of the Invisible, my firstbook of poems. It changed my life in that the opportunity opened many doors forme—I was then qualified for teaching positions that required a published book(and thus was hired at my current position at the University of CentralMissouri), and the award gave me a sense of confidence in my work. I wasthrilled to join Tupelo Press’s catalog of incredible writers, and I was invitedto read from the collection at the AWP Conference in 2017. I am so grateful forthe award and the opportunities it led to. My first book was inspired by mydoctoral studies in historical connections between poetry and medicine; I waswriting about my mother’s breast cancer, but also did extensive research onmedical literature from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The bookinterrogates the ways in which gender norms negatively affected the progress ofscientific study, as well as my own experience as a woman dealing with medicalissues and loss. My more recent work is also research-driven, but through thelens of law. As a survivor of intimate partner abuse and assault, I wanted toconfront the ways victims are ignored or subjugated by the U.S. justice system,and looked to outside study to reflect on these issues.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

In a way, I came to poetry last—as a child and young adult,I was interested in journalism; I majored in journalism in college for twoyears, until I was fired from the university newspaper and switched my major tocreative writing. After declaring a creative writing major, I took primarilyfiction classes until my last year at the university, when I enrolled in myfirst poetry workshop. All genres of writing greatly interest me, and I’vewritten poetry, too, since I was a child; however, when my wonderful professorRandolph Thomas at LSU gave me permission to take myself seriously as a poet, Iknew that I had found my language. As someone particularly interested in musicand visual art, poetry seems to make most sense in my brain—the negative spaceon the page, the lyric, the associative nature of imagery. Dedicating my lifeto the study of poetry is the best decision I’ve ever made.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

I’ve learned to let myself off the hook a bit, in terms ofhow long a new project takes. The “thinking part” tends to take months, evenyears. I’ll become obsessed with a field of study or a concept and research,read, and take notes for a long time before I ever approach shaping thesethoughts into poems. I’ll fill notebooks and notebooks with ideas, quotations,images, sketches, etc. and then usually, one day, something clicks and I’mready to write poems. There are some poems that have taken me years to write,and some that have taken an hour. My mentor calls those poems that take an hour“poems from the future”—some future version of myself knew how the poem wentand it fell from the sky fully-formed. But I do think that those poems that arequick to appear are actually the product of a lot of thought and study, andmany failed drafts of other poems, as if the repeated failure finally gavebirth to a fleshed-out form.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

I think that depends—I write many poems that don’t end upin a book, as they’re not necessarily cohesive with a larger thought I might bewriting towards. I’ve often had the experience, too, where I write what I thinkis an essay, until I whittle it down to a poem. Some of my longer poems beganas essays. From the very beginning of a new line of thought, I don’t think I amworking on a “book” from the start, though I do have several title ideas andconcepts for books I’ve never written. I think it’s fun to come up with a bookidea, but usually the poems arrive in a shape I never expected, following aline of inquiry that almost shapes itself into a collection.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

What I love about readings is the connections I am able tomake with new people, especially when they relate personally to something Ihave written and I can see that they have been touched or inspired in some way.I still keep in touch with many people I’ve met at my own readings or thereadings of other poets. Also, though, I don’t know that I necessarily enjoyreadings, as I’m introverted—as a southerner and as a woman, I think I’vealways been well-trained to be sociable and outgoing, but being on a stage andthe social anxiety that comes along with readings can be draining. I haveencountered the work of so many poets I love because I first saw them read,too, so I believe community and sharing work is integral to the creativeprocess, especially considering poetry as a part of a larger dialogue.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind yourwriting? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? Whatdo you even think the current questions are?

I recently wrote a piece for the LSU blog where I exploredsome central questions of my most recent work. Here’s a brief excerpt thataddresses some of the central theoretical and craft questions I’m asking with TheCourt of No Record: “Whilewriting The Court of No Record… I found myself asking: When legal rhetoric ismanipulated to exhaust, damage, and financially and emotionally drain people,especially disenfranchised people, how can one reempower themselves withlanguage? How can one write about unfair legal proceedings without settingthemselves up for more?… Even though poetry, as Auden attested, “makes nothinghappen,” can it give evidence that will never be heard in a court of law? Canmetaphor, though it distorts, also serve and protect in a way the law fails todo?”

Here is a link to that post: https://blog.lsupress.org/metaphor-as-shelter-in-the-court-of-no-record/

The theoretical questions are always evolving,but my work has always been concerned with what it means to say the unsayable,what it means to live in a female body in the world, both politically and inliterary spaces, and how poetry can get to deeper truths in order to looktoward positive systemic change.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

I think the writer has a responsibility to listen, toanalyze, to challenge, and to dream. Like scientists, writers must interrogatehistory and articulate the present in order to imagine a future that is more inclusive andopen to evolutions, both in language and in culture. Because words matter, and words last, I believe writershave an enormous responsibility to be empathetic, to challenge oppressivesystems of power, and to be open to new ways of seeing.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outsideeditor difficult or essential (or both)?

For the most part, I find it essential and not difficult.My editors at LSU Press are fantastic, and I think they see my intentions andconcerns really clearly. I also have a few friends who are my trusted readers—Ithink it’s important to get others’ perspectives in order to fully beconsiderate of the reader.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

From my mom: “one thing at a time”. I say this to myselfnearly every day.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, ordo you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

As a professor and editor, it’s often difficult to keep aconsistent writing routine for myself—I typically find larger chunks of time inthe summer, or at a writers’ residency, to really dedicate to craft. I try towrite and read something every day, but I need long periods of time toreflect, read, and imagine in order to create more than little scratchings on apage.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn orreturn for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I like to visit my local museum, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, or read fiction, which always renews my sense ofimagination.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Sunscreen, gasoline, chili, fresh-cut grass.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come frombooks, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature,music, science or visual art?

Yes—I am heavily influenced by visual art, music, andscientific study, especially (but not limited to) works and studies thatprogress our thinking about restrictive binaries of gender.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

There are so many that it’s difficult to list.Writers I surrounded myself with while writing my most recent book include:Muriel Rukeyser, bell hooks, Maggie Nelson, Carolyn Forche, Natasha Trethewey,Vievee Francis, Shara McCallum, Anne Carson. Writers I’m always looking towardsas guides: David Keplinger, Kathryn Nuernberger, W.B. Yeats, Seamus Heaney,Sylvia Plath, Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

There are things I’ve done that I would like to do more,like travel, campaign for causes I care about, and spend more time with my grandmother.I’ve always dreamed of going along on a scientific research expedition of somekind.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt,what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended updoing had you not been a writer?

I always wanted to be a marine biologist. If I could do itall again, I think I would go to medical school.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing somethingelse?

I really think I have to write. No matter what myjob is, I’ll always be a writer. At one point, I was working four jobs, barelymaking rent, and then, as now, I don’t know who I would have been if I hadn’tbeen writing.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was thelast great film?

Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan, The Galleons by Rick Barot.I just saw the film Orlando for the first time, and can’t stop thinkingabout it (1992, starring Tilda Swinton).

19 - What are you currently working on?

I have recently beenawarded a studio residency at the Charlotte Street Foundation in Kansas City,and I’m excited to embark on a project that blends poetry with visual art,working with visual artists in my cohort.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

July 1, 2023

last day(s) of school :

Aoife completed Grade 1 on Thursday, and Rose completed Grade 4 (achieving the 'honour roll' for citizenship, I'll have you know) the Wednesday prior. Do you remember, four or five years back, when I suggested their personalities could be boiled down into "casual" and "swagger"? Now that they're home, I suspect the next few weeks will be very busy.

Aoife completed Grade 1 on Thursday, and Rose completed Grade 4 (achieving the 'honour roll' for citizenship, I'll have you know) the Wednesday prior. Do you remember, four or five years back, when I suggested their personalities could be boiled down into "casual" and "swagger"? Now that they're home, I suspect the next few weeks will be very busy.

June 30, 2023

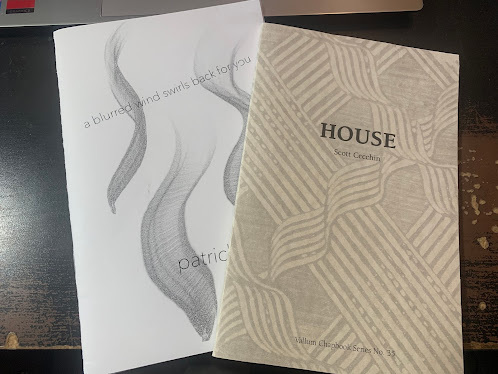

Ongoing notes: late June, 2023: Scott Cecchin + Patrick Grace,

Oddto think that my mother would have been eighty-three today; my father wouldhave been eighty-two this past Monday.

Oh, and don’t forget I have a substack, yes

? I think I’m gearing up for another book-length non-fiction project(possibly).

Oddto think that my mother would have been eighty-three today; my father wouldhave been eighty-two this past Monday.

Oh, and don’t forget I have a substack, yes

? I think I’m gearing up for another book-length non-fiction project(possibly).Montreal QC: A resident of Nogojiwanong/Peterborough, poet Scott Cecchin’s second chapbook is HOUSE (Montreal QC: Vallum Magazine/VallumChapbook Series No. 35, 2022), following Dusk at Table (O. Underworld!Press, 2020). I’m intrigued by the breaks, breaths and halts, the rhythms ofthis particular chapbook-length suite, and his poems expand upon their rhythmsas the poems progress. What I find most interesting is how and where he holdsthe small moments and fragments of speech, appearing far more compelling thanlater on in the collection, as his narratives stretch into more traditional andeven conventional plain-speech. But there is something here, and I amintrigued. As the opening title poem, “HOUSE,” reads:

The house flowers

in light. Be-

low that,

dirt. Deeper,

a glacier. And deepest:

fire.

Inside you, a moon. And

in the moon, somewhere, is

you. The sun gets inside every-

thing; and when the sun’s out

we are too.

*

The house, pressed

into the deep,

like a seed,

sinks. Look up:

air, so

many ships sinking up

there. Above that,

ice—and higher:

fire.

The earth

is shaped by fire andwater, while

water enters earth andair. The air,

sometimes, holds fire andwater,

and fire gives earth tothe air.

Montreal QC: One of the latest titles from James Hawes’ Turret Press is a blurred wind swirls back for you (2023), a secondchapbook by Vancouver poet and editor Patrick Grace, following Dastardly (AnstrutherPress, 2021). Set in three sections of sequence-fragments—“a brazen thing,” “thesky cottoned” and “a blurred wind swirls back for you”—this is a curious chapbook-lengthsequence, offering one step and then another, towards a kind of expansion, say,over a particular ending or closure. The first section offers what might be aflirtation, writing as the third page/fragment:

lightning came lightning lit the night

it gave us an easy in

an ice

to break

Whatstrikes most are the rhythms, the pacing; a very fine patter across a length oftethered fragments, although there are some moments in the language that strikefar less. Either way, there is something interesting here, and worth payingattention to, to see where Grace moves next. I say keep an eye on this one.

June 29, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Matthew Hollett

Matthew Hollett is a writerand photographer in St. John’s, Newfoundland (Ktaqmkuk). His work exploreslandscape and memory through photography, writing and walking. Optic Nerve, acollection of poems about photography and visual perception, was published byBrick Books in 2023. Album Rock (2018) is a work of creative nonfiction andpoetry investigating a curious photograph taken in Newfoundland in the 1850s.Matthew won the 2020 CBC Poetry Prize, and has previously been awarded the NLCUFresh Fish Award for Emerging Writers, The Fiddlehead’s Ralph Gustafson Prizefor Best Poem, and VANL-CARFAC’s Critical Eye Award for art writing. He is agraduate of the MFA program at NSCAD University.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book, AlbumRock, is a mix of creativenonfiction, poetry and archival material investigating a strange photo taken inNewfoundland in the 1850s by Paul-Émile Miot. The project began as a blog post,then expanded over several years to a research grant, an exploratory road trip,and eventually a published book. You learn so many things over the course of along-term project like that (publishing contracts, working with editors anddesigners, image permissions). It’s not lightning-bolt life-changing, but morecumulative. It snowballs.

My most recent book, OpticNerve, is a collection of poems aboutphotography and visual perception. It took shape over many years, too, and hadits own complicated flight path. Both books gesture towards some of the sameideas and preoccupations – ekphrasis, photography and complicity, a sense ofplace – but they’re very different. Album Rock is a macro lens, OpticNerve more fish-eyed. I like that oneis published by Boulder and one by Brick. A good solidity there.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction ornon-fiction?

I came to poetry through My Body Was Eaten by Dogs by David McFadden – it caught my eye one day in my high school library,and I read it cover to cover and almost immediately started writing poems.Terrible poems. Shortly afterwards I became fascinated by E.E. Cummings, andfilled notebooks with floaty visual cloud-poetry.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

My projects always begin as a nebulous collection of small things whichgradually cohere into a larger thing. I am always generating small things:journal entries, field notes from walks, poem fragments, quotes from books,photographs. Every project is rooted in these archives. So beginning somethingnew is usually a matter of sifting through bits and pieces, finding unexpectedconnections.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of shortpieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

A single poem usually begins either as a firsthand observation, or as anexploration of language (sometimes I think of the poems as either “outdoorsy”or “indoorsy”). Bookwise, OpticNerve is themed around photography andseeing, and I’m working on a new collection of poems about walking.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love reading aloud. During solo writing residencies I’ve often readentire books aloud to an empty house, which is a fantastic way to feel immersedin the writing’s texture and soundscape. I write my own poems with the ideathat they will be read aloud, and enjoy public readings.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kindsof questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even thinkthe current questions are?

I like looking at things. The current question depends on what I’mlooking at. The bigger question, of course, is what to look at.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

I’ve always liked Kurt Vonnegut’s take on this: “I sometimes wonderedwhat the use of any of the arts was. The best thing I could come up with waswhat I call the canary in the coal mine theory of the arts. This theory saysthat artists are useful to society because they are so sensitive. They aresuper-sensitive. They keel over like canaries in poison coal mines long beforemore robust types realize that there is any danger whatsoever.”

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficultor essential (or both)?

Working with an editor is difficult in the best kind of way, where youfeel discomfort, which is the sensation of being challenged and learning andchanging. I find it essential, but never easy.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily givento you directly)?

From Guy Debord’s autobiography: “My method will be very simple. I willtell what I have loved; and, in this light, everything else will become evidentand make itself well enough understood.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry tophotography)? What do you see as the appeal?

It doesn’t feel like moving between genres – both poetry and photographyare the work of seeing things in new ways. I’m fascinated by the way that poemsand photos can complement each other. They both feel like quieter, moreintimate ways of making, creating meaning by stringing a series of smallobservations together.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you evenhave one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My only routine is to read for about 45 minutes as I eat breakfast. Irealize it’s a luxury to structure my mornings this way, and I cling to itdesperately. I don’t have a regular writing routine, but I make writing timeduring evenings or days off, or once in while through grants, residencies orcreative writing classes.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for(for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Going for a long walk works miracles. I can sometimes also unblock mybrain by switching from my computer to writing on paper.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Ocean wind – not so much the fragrance but the force of it. There’snothing like the breath-burgling, voice-snuffing, brain-numbing winds out onthe headlands near St. John’s.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, scienceor visual art?

I went to art school, and I really enjoy writing in response to images –paintings, photographs, films. Anything visual. I’m especially interested inthe way that documentary films can be lyrical and poetic (I love Agnès Varda’swork, and Werner Herzog’s), and the way that they can weave real-lifeobservations together to create meaning. There are lessons there for poetry, Ithink.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

Teju Cole is an incredible writer and photographer and I enjoy his booksimmensely. I just finished reading Robert Macfarlane’s Underland and reallyloved it. Likewise Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass. And one of my favourite films is Agnès Varda’s The Gleaners and I, a documentary about finding things, which begins in whimsy and moves almost surreptitiously to morepoignant social concerns.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

A really long walk, like the Kumano Kodō or the Pennine Way or theCamino de Santiago.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would itbe? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had younot been a writer?

Writing is an ongoing creative practice for me, but I wouldn’t call itan occupation. I do lots of things that are not writing – photography, designwork, web development, arts administration.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Writing gives me a specific kind of joy that I don’t experienceelsewhere. I love language – its sound, its mouthfeel, the deep deep history ofwords – and I get enormous pleasure from the process of wrangling language intosomething poem-shaped or book-shaped.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last greatfilm?

Teju Cole’s BlackPaper is a collection of brilliant,incisive essays about art, photography and seeing. Cole traces Caravaggio’stravels in exile, considers what it means to look at photographs of suffering,and writes about writing during dark times. “The secret reason I read, the onlyreason I read, is precisely for those moments in which the story being told isdeeply alert to the world, an alertness that sees things as they are or dreamsthings as they could be.”

I watch a lot of movies. The one I’ve enjoyed the most recently is CiroGuerra’s The Wind Journeys. It’s set in Northern Colombia, and in addition to marvellouscinematography, characters, and music, it features the most captivatingaccordion battles ever put to film.

20 - What are you currently working on?

A collection of poems about walking.

June 28, 2023

Béatrice Szymkowiak, B/RDS

Re/sound

How pleasing when aclouded sky

ripens with rain. Water-logged

seeds imagine blossoms& the swell

of duration / wings sail along

ponds & hedges /clear rivulets

root rivers. Hear in shallowpools,

the unremitted flappings/ flocks

wading the course of days

in the afterstorm / an axe’sthud

hung at the extremity ofa twig

drops & drowns. Ringsripple,

quills / fly off.

Thefull-length debut by French-American writer and scholar Béatrice Szymkowiak [see her recent '12 or 20 questions' interview here],following RED ZONE (Finishing Line Press, 2018), is B/RDS (SaltLake City UT: The University of Utah Press, 2023), published as winner of theAgha Shahid Ali Prize in Poetry. Much like New Hampshire-based Polish-American poetand translator Ewa Chrusciel’s recent Yours, Purple Gallinule (Omnidawn,2022) [see my review of such here], B/RDS (obviously) is a book of birdsthat writes into the Anthropocene and out of John James Audobon’s Birds ofAmerica (1827-1838) as a source text both for content and language, pullingthreads and highlighting the losses of entire species of birds due to humaninterference. As Szymkowiak offers as part of the book’s “Preface”:

My writingprocess started by considering the text of Birds of America (the OrnithologicalBiography accompanying the drawings) as an archival cage. For this reason, Iresolved to strictly abide by the rule of keeping the order of the words (orletters) from the text-source—my text-source being Birds of America in alphabetical order. I then selectively erasedthe textual cage to reveal its ambiguity and the complex relationship betweenhumanity and the other-than-human world. As the cage disappeared, birdsescaped, their voices inextricably entangled with ours—a spectral, equivocal “we.”Finally, I reshuffled the resulting poems and added migratory poems written inmy own words and prompted from lines from the erasure poems. These migratorypoems, like ripples, trace the link between past and present.

B/RDS is a book of precision and moving through space,through air, propelled and attuned to a uniquely-magical language and lyric. Thereis such delight and play of strike and sound through these lines, even as eachpoem sits as an individual cobblestone or brick, each set to articulate theaccumulated outline of her subject of ecological erosion. She writes on birds,and the waves of man-made losses and their rippling effects. As Agha Shahid AliPrize judge Monica Youn writes as part of her “Foreward”: “Throughout Béatrice Szymkowiak’sdevastatingly beautiful B/RDS, I felt as if I were responding to asimilar call, but the echoing voices in this collection are real, urgent,inescapable—a fusion of elegy and prophecy. With its trills and elisions, gracenotes and percussive cries, the collection gives voice to the billions of birdslost on this continent over the past decades through human predation, industrialization,waste and sprawl—James Elroy Flecker’s classic phrase seems apt: ‘That silencewhere the birds are dead / yet something pipeth like a bird.’” Szymkowiak simultaneouslywrites directly and slant on birds and their losses, writing of seasons andflights, of sun and landscapes along the ridge. As the prose poem “Wherever SunEnds” writes, in full: “Two crows perched in the pine grove caw ghosts ofunsung passing. Ice spears from the eaves. Dread devours clouds. I fear howtangible your tongue before its silence. Deer ellipses dot the snow thawing clock.On the ground, a red-tailed hawk claws & tears its own disappearance.”

The Night Is Pitch-Darkbut We /

murmur through shatteredglass breathe, breathe, the light from dead stars still glows! Along nighteaves, mangled starlings heave stellar wings to tenebrous ceilings & tiltequinox back to breathe, breathe constellations. Light isshattered from the mangled night. how many dead stars still glow?Tenebrous wings cleave away from you, heave equinox back to pitch-darkceilings. Breathe, breathe, starlings murmur along mangled eaves, howconstellations tilt from dead stars to light! Still you,shattered wings through tenebrous glass murmur how many, how many dead stars

& cleave equinoxhalves away.

June 27, 2023

A manifesto on the poetics of Asphodel Twp.

Sadto hear, via the Canadian Bookbinders and Book Artists Guild (through a facebook post) that Canadian bookbinder Michael Wilcox has died. Back out in2011 (July, I think) we drove out to Big Cedar so Christine could interview himfor the CBBAG magazine, and she brought me along for the sake of the three-plushour drive, as well as for the fact that the Wilcox was well-known for hisgruffness. Wilcox was a Master Bookbinder, and had been decades been repairingbooks for the University of Toronto Rare Books Library, driving up to pick upbooks to take home for repair (I suspect he was the only one allowed to leavethat building with any of their materials).

Wedropped into his studio, and apparently the fact that I tagged-along allowedfor some stories he might not have told. Before the interview officially began,he showed us his studio workshop, including the incredible array of tools he’d hand-made.Given I’m unaware of most printing and book-repair tools (especially then), I keptasking him what various items and equipment were and were for, which wouldprompt him to tell a small story for each (stories he might not have told,Christine says, as she would have known what all that equipment was). It was aninteresting visit, and his wife Suzanne was delightful, and she said we couldcome back and visit at any time (he didn’t seem against the idea, but also notthe sort of thing he might have offered). I’m wishing we would have taken her upon that (although he and Christine did correspond quite a bit after our visit).

Here'sa poem I wrote them, after we landed back home (and yes, they did live inAsphodel Township):

A manifesto on the poetics of Asphodel Twp.

for Michael & Suzanne Wilcox,

Ihave forgot

and yet I see clearly enough

something

centralto the sky

which ranges round it.

William Carlos Williams, “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower”

1.

If Heaven, river. What greeny something. Shine,Kawartha Highlands. Lake, and early hum. Once, in the shadows. Glowingoutwards, temperate. Ontario syntax. Reassuring this, and self. A revelation,you. I see the world. Claw, in architecture. Bipolar lift, a tongue. A peacethe mind can breathe. Although the dark remains, small lights in favour.Celebration, soar.

2.

The mouth, at Cameron's Point. An acid-free layer.Craft: a promise, fold. Is this all nothing? Repair, a situation. Sorrow, and acock-eyed grin. In this room, this other room. A complicated, binding. Thismorning, Highway 7. Double-binding, surface of a still. Lovesick Lake, meetinghip to shape to shore to night. A glacier, made. Such frozen light.

3.

Asphodel, greeny flower. Surveyed in 1820, RichardBirdsal. To warm up, bottles under covers. All the uphill way. If it is,repeated. Notes, and highway. Hummingbird feeders, to keep from ants, fromblack bears. An empty bench, among. Back and forth, snow-scribbling. Some otherstar. The metaphor: cast iron, photo-legal. Walking. John Becket and his wife,five children.

4.

You left your mark. Combination of industry. Vaguelyseen, but can't cross. Waterskin. Go, central-eastern. The shores of Rice Lake,frequent. Burned away. Big Cedar, smoke. Yours, truly. Tell, no other story.Picked up, by useless clouds. Such well-bred manner, brush. Such lovely liquid.A leather casing, isolation. Those that have the will.

June 26, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Tucker Leighty-Phillips

Tucker Leighty-Phillips is the author of

Maybe This Is What I Deserve

(Split/Lip Press, 2023). He lives in Whitesburg, Kentucky. Learn more at TuckerLP.net.

Tucker Leighty-Phillips is the author of

Maybe This Is What I Deserve

(Split/Lip Press, 2023). He lives in Whitesburg, Kentucky. Learn more at TuckerLP.net.1 - How did your first chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

It’s difficult to answer this question in past-tense, because it continues to change my life. It has been a comfort to hold it and know that I created it. I used to work with a lot of musicians–I was a show promoter, a booking agent, a tour manager and merch guy. But I was never an artist myself, and I envied that a lot. I wanted something to call my own. I wanted it to be music, but I could never play. Releasing my first chapbook feels like releasing my first EP. It’s something I can point to and feel good about.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I think it’s just the form that interests me the most. When I was a kid, I read Louis Sachar’s Sideways Stories From Wayside School over and over. It contained everything I could ever want in a book–humor, invention, brilliant callbacks and lively storytelling. Something about the possibilities contained within that book made me want to contribute to the world in a similar way.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Every draft is different, which is a boring answer, but it’s true. Some of my favorite stories are ones I’ve hammered out in one sitting, or thought about in my head for a long time before committing it to the page. I’m also not a very good editor, so if it doesn’t work early on in the process, I may lose interest. Pitiful, I know.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I’ve always wanted to be a “project” writer, because some of my favorite books are projects. I love the long-form exploration of an idea. I’m reading Joe Brainard’s I Remember right now, and his approach is so fascinating. It’s a true honeycomb of a novel. I’d like to commit to doing something similar at some point. I typically just write short stories and see what they do when placed in close proximity, rather than thinking about an umbrella theme from the jump.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I think readings are fun, but I wish they were more fun. I want to be more deliberate about creating an atmosphere when I read, being a performer. There are some authors whose readings I’ve really loved, because they know how to perform. Danez Smith comes to mind. I’m also a longtime fan of Scott McClanahan’s boombox readings, where he would read a story with music playing on a boombox in the background, and in a climactic moment would destroy the boombox, hold a lull in the room, and then pull out another boombox playing the same song, picking up where the last boombox left off.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I was doing a bunch of applications a year or two ago, and I always led with a mission statement: Tucker’s work celebrates the lives of the impoverished, but never romanticizes their poverty. I wanted to create work that felt true to a lived experience, without doing the hokey “everything’s okay and we don’t actually require material needs because we have each other.” We can still have each other, even if nothing is okay.

I think that continues to be a major theme in my work, but it’s also evolved. I’ve been writing a lot about nostalgia, a concept I’m skeptical of, but love to play with in my work. Nostalgia feels conservative in a lot of ways. It yearns for a previous time. It glorifies individual experience. But it can also be a tool of connection–to find our similarities, to understand the ways we think alike. I’m trying to use it as a critical tool in my work, to reexamine the past and imagine a collective, more communal future.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Oh man, that’s a much bigger question than I can wrap my brain around. I think they should punch up, for sure, and be willing to call out those punching down. I think they should continue to find possibility and explore it, even in places where it seems there is none.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I’ve never had a problem with them. Sometimes, a difficult editor is one who cares a lot, and wants to tighten your work. It has done me good to fight to defend my prose.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Well, I don’t think it works anymore, but I once read that you should sign up for AAA Membership from your cell phone after you’ve broken down. But now I think they make you wait a week for your membership to kick in. I used it once and it saved me a ton of money.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to plays to essays/reviews)? What do you see as the appeal?

The ease fluctuates! There are months where I can’t envision anything beyond a single medium. And then there are days where I am working on three at the same time. I am also always interested in blurring the lines between genre distinctions and toying with what’s possible. I remember there being an old Reddit thread about what Major League Baseball would be like if games were only played once a week, and the post turned into this heartbreaking, harrowing account of love, artistic success, and loneliness. It was deleted a while back, but I think about it often, because it was one of the first times I was genuinely surprised by a piece of writing on the internet.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I have absolutely zero routine. I am very flighty and cannot commit to any kind of schedule. When it hits, it hits. When it isn’t hitting, I don’t bother.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I like attending readings. There aren’t a ton where I live, but I always come away with new ideas and enthusiasm. I think that’s important, trying to be in a shared space with people who are excited about art. We’re communal creatures.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Grippo’s potato chips and compost.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Oh absolutely. I would say I’m arguably more inspired from non-books than I am books. Nickelodeon shows like Hey Arnold, The Adventures of Pete & Pete, and Rugrats play a huge role in my work. Old Looney Tunes cartoons; their internal logic and engines especially. The films of have been massively important to my progression as an artist. I’m also heavily influenced by gossip–I try to write stories that feel like anecdotes from within a community.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

There are a few writers or books who I’ve read and found something unlock within me–the most notable being Deb Olin Unferth, Scott McClanahan, Shivani Mehta, Renee Gladman, Michael Martone, and Lucy Corin. When I was a teenager, I read Vonnegut and Brautigan, and I think they helped attract me to the short-form.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I really want to get into mudlarking. I watch lots of videos of people in England doing it.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Well, when I first went to school, I thought I wanted to go into PR. I don’t think I ever wanted to do it, but it felt like a good use of my skills. I really like cooking, and felt like working in kitchens gave me a lot of tangible skills. It’s important to know how to use a kitchen knife.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Honestly, I have no idea. I didn’t really write until my mid-twenties, and it felt like something clicked. Like I mentioned, I always wanted to be a musician, but could never get it right in lessons. I started writing, and felt like I was always steadily improving, which was motivating. It feels good to progress in something.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last book I loved was Lindy Biller’s Love at the End of the World, which is a chapbook story collection about climate change, motherhood, and the experience of trying to be a kind person even amidst an apocalypse. I haven’t watched a movie in a hot minute, because I’ve gotten really into Columbo , but I did recently rewatch Ozu’s Good Morning, which is one of my favorites.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m mostly sending emails to promote MTIWID, but I’m still kicking around a couple projects. I’m superstitious, but I’ll say one of them is a novel-length quasi-historical Appalachian fairy tale. Someone referred to it as “Evil E.T.”

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

June 25, 2023

two poems + an upcoming (Ottawa) reading,

I've two poems online as part of the new issue of horseshoe literary magazine! So, that's pretty cool.

Oh, and did you see I'm reading this Thursday night with touring poet Kevin Spenst (Vancouver) and Conyer Clayton (Ottawa)

?

I've two poems online as part of the new issue of horseshoe literary magazine! So, that's pretty cool.

Oh, and did you see I'm reading this Thursday night with touring poet Kevin Spenst (Vancouver) and Conyer Clayton (Ottawa)

?