Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 64

January 31, 2024

David Melnick, Nice: Collected Poems, eds. Alison Fraser, Benjamin Friedlander, Jeffrey Jullich & Ron Silliman

I found Melnick’s work after moving to Berkeley, where helived in the late 1960s and early ‘70s before moving across the Bay to San Francisco.I had heard tell of his readings of PCOET—his “correct” pronunciations, howonly a few could remember the exact sounds his private language formed. I hadheard of his famous Homer Group, and read how Melnick’s voice was infectiousamong the other “Homersexuals,” how his homophonics perversely instigated akind of Bacchic frenzy. I remember being shown an event flyer from 1974, fromthe now-defunct Cody’s Books, featuring Melnick reading with Telegraph’s “BubbleLady,” Julia Vinograd. I would walk past the former Cody’s building daily tofeel their presences decades after.

Melnick’s workcreated a kind of orbit, tugging me to its center, but the force that propelledmy obsession was impossible to see. Was it that Melnick gave language to queerfeelings I had known somewhere deep inside me, but had been unable to voice?Was it that his work points to a kind of unspeakability of these very “qqrer!”feelings? I am left wondering what kinds of queer feelings we can represent inqueer (il)legibilities. Whether Melnick offers us a cipher, a code, a means ofreckoning with language and its limits, feelings and the limits of representingthose feelings, too. (Noah Ross, “(POETS; EXIST?”)

Ihadn’t even heard of San Francisco poet David Melnick (1938-2022) before thisnew collection landed in my mailbox—

Nice: Collected Poems

, eds. Alison Fraser, Benjamin Friedlander, Jeffrey Jullich & Ron Silliman (New York NY:Nightboat Books, 2023)—a book that includes preface on the author by poet and critic Noah Ross [see my ’12 or 20 questions’ with him here; see my review of his second collection here], and a collaborative introduction-proper by thefour editors. I’m fascinated by these seeming-reclamation projects that Americanpublisher Nightboat Books has been publishing over the past decade or so(possibly longer, but I’ve only been aware of their work for the past dozen-plusyears), all of which swirl around particular writers and writings, allowing documentationfor a wealth of literary activity, specifically: by, about and through queerwriters and writing. Some of the collections I’ve been particularly impressedby include their

Beautiful Aliens: A Steve Abbott Reader

, edited byJamie Townsend with an afterword by Alysia Abbott (2019) [see my review of such here],

We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics

, eds.Andrea Abi-Karam and Kay Gabriel (2020) [see my review of such here] and

WritersWho Love Too Much: New Narrative 1977-1997

, eds. Dodie Bellamy and KevinKillian (2017) [see my review of such here]. I’d probably also include thecollection

On Autumn Lake: The Collected Essays

(2022) by American poetand critic Douglas Crase [see my review of such here] to this list as well. Thereis something to be acknowledged and appreciated in Nightboat’s ongoingattentions to providing critical consideration, examination and celebration tothese histories that might otherwise have been overlooked, misunderstood oreven completely forgotten. As the first poem of Melnick’s posthumous collection,the five-page “I. LE CALME,” ends:

Ihadn’t even heard of San Francisco poet David Melnick (1938-2022) before thisnew collection landed in my mailbox—

Nice: Collected Poems

, eds. Alison Fraser, Benjamin Friedlander, Jeffrey Jullich & Ron Silliman (New York NY:Nightboat Books, 2023)—a book that includes preface on the author by poet and critic Noah Ross [see my ’12 or 20 questions’ with him here; see my review of his second collection here], and a collaborative introduction-proper by thefour editors. I’m fascinated by these seeming-reclamation projects that Americanpublisher Nightboat Books has been publishing over the past decade or so(possibly longer, but I’ve only been aware of their work for the past dozen-plusyears), all of which swirl around particular writers and writings, allowing documentationfor a wealth of literary activity, specifically: by, about and through queerwriters and writing. Some of the collections I’ve been particularly impressedby include their

Beautiful Aliens: A Steve Abbott Reader

, edited byJamie Townsend with an afterword by Alysia Abbott (2019) [see my review of such here],

We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics

, eds.Andrea Abi-Karam and Kay Gabriel (2020) [see my review of such here] and

WritersWho Love Too Much: New Narrative 1977-1997

, eds. Dodie Bellamy and KevinKillian (2017) [see my review of such here]. I’d probably also include thecollection

On Autumn Lake: The Collected Essays

(2022) by American poetand critic Douglas Crase [see my review of such here] to this list as well. Thereis something to be acknowledged and appreciated in Nightboat’s ongoingattentions to providing critical consideration, examination and celebration tothese histories that might otherwise have been overlooked, misunderstood oreven completely forgotten. As the first poem of Melnick’s posthumous collection,the five-page “I. LE CALME,” ends:These languages passaway:

:fellatio, ofsubjection

now kings are dead

becausethe head is lowered

“eyes ripe asolives

“a green seaknobby

bit by worms

stirred, in

the main stream

“bee keeperseized the earth

“size of a star

Walking, sorrowslew me

Nice: Collected Poems collects four previously-publishedlimited-edition works by Melnick across nearly fifty years of scattered production:Eclogs (Ithica House, 1973), PCOET (G.A.W.K., 1975), Men inAïda (Tuumba Press, 1983) and A Pin’s Fee (Logopoeia website, 2002;Hiding Press, 2019). There’s a liveliness to this work, one that sweeps unapologeticallyinto experimentation and the playfully-ridiculous, a quality that is quiterefreshing; the earlier works clearly showcase a poet of his period, employinga particular flavour of 1960s and 70s experimentation, but somehow timeless,offering an expansive play across meaning, sound and the lyric through apoetics of subverted and invented language. It would be impossible not to be simultaneouslycharged and charmed by the expansive heft of the poem “Men in Aïda,” a homophonictranslation of the Iliad, a piece that can’t not be heard aloud, evenfrom within the bounds of quiet reading. The language really is propulsive, andmy ears can catch comparisons with language/sound poets north of the border,from bpNichol and Christian Bök to The Four Horsemen, Gary Barwin and Gregory Betts (among others). Such glorious gymnastics of sound! As Melnick’s poem begins:

Men in Aïda, they appeal,eh? a day, O Achilles!

Allow men in, everyAchaians. All gay ethic, eh?

Paul asked if tea moussesuck, as Aïda, pro, yaps in.

Here on a Tuesday. ‘Hello,’Rhea to cake Eunice in.

‘Hojo’ noisy tap ashideous debt to lay at a bully.

Ex you, day. tap wrote a ‘D,’a stay. Tenor is Sunday.

Arreides stain axe andRon and ideas ‘ll kill you.

Movingthrough the material, I’m simultaneously surprised and not that I hadn’t heardof this poet before this book landed, making me wonder just how much materialexists in the world by those otherwise-forgotten writers? We move so quickly tothe next book and the next book that there are probably dozens of poets leftbehind: “only alive as long as in print,” to paraphrase a line by the (since late)Canadian poet Patrick Lane. So much literary history is unrecorded andoverlooked, and this is a wonderfully vibrant collection, even through the darkelements of Melnick’s later work, as the collaborative “INTRODUCTION” writes:

In parallel with hislife, Melnick’s poetry also yields story, a compact one. Four books comprise his legacy: Eclogs (written1967-1970), PCOET (mostly 1972), Men in Aïda (1983), and A Pin’sFee (1987). As the dates of composition show, his years of creativity spana crucial two decades in the rise of queer community: his first book begunbefore Stonewall; his last written in the crisis years of AIDS. And each bookreflects a truth of its moment, though in a manner entirely its own. In Eclogs,the beautiful façade of coded language preserves an experience it screens fromview. PCOET yields to the joy of invention, creating a language all its own. Menin Aïda, the pinnacle of this span, is his epic: an act of gayworldbuilding, embracing the past and transforming it through homophonic translation.A Pin’s Fee, the shortest of the four, is anguished: its last word, “DEATH, “repeating forty-five times. After this, nothing. For the rest of Melnick’slife, another thirty-five years, no other poetry would surface.

January 30, 2024

Maxine Chernoff, Light and Clay: New and Selected Poems

3.

Roll over, Oscar Wilde. MeetGertrude Stein

and the Little Sparrow. MeetJim Morrison and

Chopin too. Deeper and deeperour travels

took us: there wasCreate, whose indoor toilets

were the first preserved.The tourists

from the cruise had sealegs, as Knossos listed

right or left. TheMexican economist hated

America’s presumptions,he confessed at dinner,

before the ping pong balldisappeared into the Aegean.

I thought Ship ofFools, how doomed

our journeys, feltcomfort in moss roses curled

around a railing wheremen worked sums.

The castle from the Crusades,rehabbed by Mussolini:

palimpsest of wrongideas: and no plot to save us. (“Zonal”)

Iwas curious to see a copy of Mill Valley, California poet and editor Maxine Chernoff’s latest, Light and Clay: New and Selected Poems (Cheshire MA:MadHat Press, 2023), a collection that selects poems across six of her nineteenbooks of poetry— (Apogee Press, 2005),

The Turning

(Apogee Press, 2007) [see my review of such here],

To Be Read in the Dark

(Omnidawn, 2011),

Without

(Shearsman Books, 2012) [see my review of such here],

Here

(Counterpath Press, 2014) [see my review of such here] and Camera(Subito Press, 2017) [see my review of such here]—as well as a healthy openingsection of new poems. Focusing on her work with and through sonnets, sequences,extended lines and other lyric structures, Light and Clay exists as a counterpointto her

Under the Music: Collected Prose Poems

(MadHat Press, 2019) [see my review of such here], andthe two collections paired offer an interesting overview of Chernoff’sattention to poetic structure. “Love’s tender mercies clear the air,” shewrites, to open the poem “Traced,” “Unhinging the gate to practiced longing. /Tied to life, you spill into water, deeper / Than any atmosphere.” Chernoff’spoems extend lines of thought across great distances, whether the line, thepoem or as a sequence of pulled-apart sentences, offering a lyric that works toarticulate and examine intellectual and physical space. Hers is a lyric,essentially, of seeing, and what she sees is illuminating. As the short poem “Granted”ends: “We stayed in bed for years / and took our cures patiently / from eachother’s cups. / We read Bleak House and / stored our money in socks. /Nothing opened as we did.”

Iwas curious to see a copy of Mill Valley, California poet and editor Maxine Chernoff’s latest, Light and Clay: New and Selected Poems (Cheshire MA:MadHat Press, 2023), a collection that selects poems across six of her nineteenbooks of poetry— (Apogee Press, 2005),

The Turning

(Apogee Press, 2007) [see my review of such here],

To Be Read in the Dark

(Omnidawn, 2011),

Without

(Shearsman Books, 2012) [see my review of such here],

Here

(Counterpath Press, 2014) [see my review of such here] and Camera(Subito Press, 2017) [see my review of such here]—as well as a healthy openingsection of new poems. Focusing on her work with and through sonnets, sequences,extended lines and other lyric structures, Light and Clay exists as a counterpointto her

Under the Music: Collected Prose Poems

(MadHat Press, 2019) [see my review of such here], andthe two collections paired offer an interesting overview of Chernoff’sattention to poetic structure. “Love’s tender mercies clear the air,” shewrites, to open the poem “Traced,” “Unhinging the gate to practiced longing. /Tied to life, you spill into water, deeper / Than any atmosphere.” Chernoff’spoems extend lines of thought across great distances, whether the line, thepoem or as a sequence of pulled-apart sentences, offering a lyric that works toarticulate and examine intellectual and physical space. Hers is a lyric,essentially, of seeing, and what she sees is illuminating. As the short poem “Granted”ends: “We stayed in bed for years / and took our cures patiently / from eachother’s cups. / We read Bleak House and / stored our money in socks. /Nothing opened as we did.”Whereasher prose poem selected opens with an introduction by Robert Archambeau, thiscollection exists without, which, as regular readers of this space are alreadyfully aware, I consider a severe oversight for any selected or collected; it isimportant to place writer and writing within context, and offer why and howthis collection was decided upon, let alone shaped. For example: did the authormake the selections herself? What was the process of these books selected, andselected from, and not others? Either way, opening with the sixteen-part sonnetsequence, “Zonal,” the poems in the “new” section employ an increased complexity(compared to the other poems throughout), providing a layering of image, insight,craft and instability, finely-woven with deceptive ease. The shift across thebody of her work, at least as presented in this two hundred page-plus volume,is intriguing, subtle and even clarifying. This is an incredible work by a severelyunderrated poet, sliding under the radar for more than enough time (a recentfolio on her work did appear recently in Denver Quarterly, Vol 57 No. 4(2023), edited by Lea Graham, although the issue itself doesn’t seem to belisted anywhere on their website).

You Took the Dare

To live here and there,as recluse

and as host. While everythingexploded

and flames turned waterred, you

suggested a menu and gaveto

a proper cause. Nothing endured

the losses around you,the final note

that sounded past alarm. Acloudy

resemblance of what oncesufficed came

to be known as grace asyou listened

to grass growing, to aboy praying

near the great stonewall. Crisis after

crisis stacked up likeplanes in fog.

You counted moss-coveredbricks near

the former factory,where, at sunset,

brown light flickered.

What else to do but live?

January 29, 2024

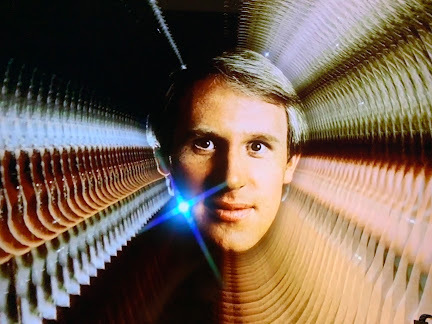

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Melia McClure

Melia McClure

is the author of the novels

All the World’s a Wonder

and

The Delphi Room

. After a childhoodspent dancing and acting, she has been seen on film, television, and the stageof The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Favourite acting memories include aturn as Juliet in an abridged collage of Shakespeare’s classic and . Film and theatre along with visual artare the three muses that inspire her writing. They kindle her fascination withthe book-to-film metamorphosis. Her fiction is a confluence of magic realism,black humour, and abnormal psychology, opening unexpected backroads to elementsof the metaphysical. Melia is a graduate of The Writer's Studio at Simon FraserUniversity in Vancouver, where she was born. She now divides her time betweenCanada and Europe.

Melia McClure

is the author of the novels

All the World’s a Wonder

and

The Delphi Room

. After a childhoodspent dancing and acting, she has been seen on film, television, and the stageof The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Favourite acting memories include aturn as Juliet in an abridged collage of Shakespeare’s classic and . Film and theatre along with visual artare the three muses that inspire her writing. They kindle her fascination withthe book-to-film metamorphosis. Her fiction is a confluence of magic realism,black humour, and abnormal psychology, opening unexpected backroads to elementsof the metaphysical. Melia is a graduate of The Writer's Studio at Simon FraserUniversity in Vancouver, where she was born. She now divides her time betweenCanada and Europe.1 - How did your first bookchange your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? Howdoes it feel different?

The publication of my firstbook vindicated my conviction that I could do something unusual with the novelform and see this odd literary concoction enter the wider world. The DelphiRoom mixes prose—much of it in the form of an epistolaryrelationship—with screenplay and is a nod to cinema. Mymost recent work, All the World’s a Wonder, is a hat-tip to the theatreand marries playscript with prose, some of the latter as diary entries andemails, but almost all as character monologues that speak directly to theaudience. One of my aims with this book was to transform the novel into a stageperformance, with the reader in the front row. A play within a novel.

The Delphi Room is a love story about two cinephilestrapped in adjacent rooms which they believe to be hell; it uses an insularsetting to access the expansive internal realities of its characters. Incontrast, All the World’s a Wonder traverses from Manhattan to Corfu,and from modern day to the Jazz Age; it likewise plunges into emotional abyssesand psychological chasms, but through a broader scope of storytelling.

2 - How did you come tofiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I’m an actor, and for me,fiction is a natural extension of performing. When I write, I’m channelling thecharacters the way an actor does, and for that reason my fiction isvoice-driven and dialogue-rich.

3 - How long does it take tostart any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly,or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their finalshape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I can be slow to commenceand slow to proceed. My approach is careful and intuitive. I can also writescenes at a rapid pace once I’ve said to hell with it and stepped on stage, soto speak. I often have an opening scene in mind. Because I work by listeningfor direction from the characters, who frequently say surprising and inconvenientlyillogical things, I must make an epic pact of trust that what they say isleading somewhere, preferably not off a cliff. Although the editing process isinvaluable, my early drafts look quite similar to the final result. Perhapsthis is because I need to be loving the language and the voices and feel thatthe bones of the piece are strong to continue the journey.

4 - Where does a work ofprose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end upcombining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" fromthe very beginning?

I began my writing life withshort fiction, but now most of my prose begins with the idea that what I’mwriting will become a book. That said, a novel is constructed scene by scene, andbecause my work tends to spring from the perspective of a dramaturge, I ventureforth with a focus on the dramatic microcosm and let the macrocosm take care ofitself.

5 - Are public readings partof or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoysdoing readings?

My novels are written forlive performance. Storytelling is an oral tradition. I love to put on my actorhat and share the work with an audience.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

When I began writing Allthe World’s a Wonder, I was musing on how one might go about bringing toliterary life the mysticism and theatrics of the creative process, itsdevastation and exultation. My lens was on the artist as conduit, on theartistic impulse being dictated by deathless otherworldly characters.

All my work asksmetaphysical questions, bends time and space while remaining rooted in realism,and probes the possibilities of the mind, love, and redemption.

Art is a call and responseabout the search for meaning. So, although the questions posed by a given workmay be coloured by the details of the day, the answers we are striving towardare intemporal. An artist offers incomplete answers which are perhaps fragmentsof an ineffable completeness.

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

Art reminds us that what werefer to as reality is just one possibility plucked from an infinite spectrumof potentials. The writer opens the door to dimensions which are not already unveiledin the temporal world, and these dimensions would never be actualized here,were it not for the artist’s insistence on prying into shadowy corners.

It is through the stories wetell and the stories we read that the stories we live are revealed anew.

8 - Do you find the processof working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

A keen editor is theessential first audience member, and the editorial process is an extended dressrehearsal, to lean on theatre jargon. Is the performance playing to the back ofthe house? Will tomatoes be tossed?

Still, the process isdelicate, and thus stepping into it involves a degree of trepidation. To feelprotective of one’s creations is only natural; for the writer, a difficultbalance of defensive vigilance and open-minded serenity is required.

9 - What is the best pieceof advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved inyour heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and likebooks that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek theanswers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them.And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you willthen gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into theanswer.”

—Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

10 - How easy has it beenfor you to move between genres (writing to acting to dance)? What do you see asthe appeal?

Dance was an important partof my childhood and my introduction to performance. Acting also began early, asdid making up stories and writing them down. Storytelling and self-expressionwere always essential, no matter what form they took. Writing and acting seem anatural pair to me, the internal and external versions of the same expressiveimperative. With writing, I love that I can both become the characters as anactor does—even though no one can see me—and perch in the director’s chair, guiding theaction.

11 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

Morning, when the mind hasjust journeyed back from the other side of elsewhere and life has yet to pouncefrom all angles, is preferred. Tea, reverie, write, celebrate wee victories.

12 - When your writing getsstalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

Years ago, I began dabblingwith paint. It is a way to experience the pure freedom and joy of creationwithout the pressure of striving to excel. The art of child’s play.

13 - What fragrance remindsyou of home?

The scent of backstage, of aslant of spotlight streaming with dust.

My parents gave me thechance to taste the stage early on. Their support is my talisman. Even when I wasa very young child in a ballet recital, the scent of an old theatre and the warmsmell of bright lights felt like a second home and meant both a deep connectionto my family and to grand unknown realms, soon to be born.

14 - David W. McFadden oncesaid that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influenceyour work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Books are sensory experiencesthat come from other sensory experiences. Henry, a character in All theWorld’s a Wonder, is a violinist. I was inspired by the singulartransporting sensation of a solo violinist playing Ravel. Anais, from the samenovel, is passionate about cuisine, her culinary creations paying homage both toher Hungarian grandmother and to the beauty of Greece.

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I will read the gamut fromcrime fiction to haiku to stage play. I am less concerned with my taste andmore simply curious about the possible majesty of words and story. Many of thewriters I’ve long loved—Alice Munro, to name a beloved icon—have a style very different from my own. If anything,I am drawn to what is far departed from my favoured stomping ground. I love reading stage playsas it feeds my fondness for dialogue. I adored The Cripple of Inishmaanby Martin McDonagh when I sawit on the stage and recently loved it again on the page.

16 - What would you like todo that you haven't yet done?

Travel the Silk Road. When I think ofstorytelling as a spoken-word tradition, I think of a caravanserai full oftraders bearing tales. The chronicles collected and shared along these fabledroutes doubtless served as spiritual lamps for weary travellers in the coldfirelight, and likely influenced the world of then and now in far more waysthan we can imagine.

As both the traveller and the storyteller know,and in the words of André Breton, “…literature is one of the saddest roads thatleads to everything.”

17 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

The healing arts. Words canheal, but if not words, then herbs.

18 - What made you write, asopposed to doing something else?

It is in writing the voicesof others that I feel most myself.

19 - What was the last greatbook you read? What was the last great film?

I reread Lisa Moore’s short-storycollection Open. A white napkin, marked with red lipstick and fallen tothe ground, is a wounded dove. Arresting.

One of my treasured films isThe Road Home, directed by Zhang Yimou. Simple, gentle, graceful, timeless.

20 - What are you currentlyworking on?

There seem to be characterschattering in my ear, flinging themselves between Southeast Asia and New York, barkingout another novel. Heaven forfend.

January 28, 2024

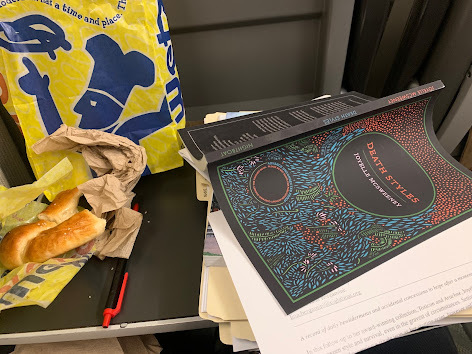

London (Ontario) Calling : report from Greg Curnoe's studio, Doctor Who + Antler River Poetry,

In case you hadn't heard, I took a VIA train nearly two weeks ago to London, Ontario for the sake of a reading I was doing through Antler River Poetry, which is pretty exciting. Given the length of the train (five hours to Toronto; an hour's wait; two-plus hours into London), the series was good enough to provide me with two nights of hotel, so I didn't have to worry about reading on a travel-day. I wandered leisurely across a Tuesday west along lakeshore, into, through, and beyond Toronto suburbs and into the wilds of Southwestern Ontario. The new Joyelle McSweeney title (which lands properly in April), I should have you know, is astounding.

In case you hadn't heard, I took a VIA train nearly two weeks ago to London, Ontario for the sake of a reading I was doing through Antler River Poetry, which is pretty exciting. Given the length of the train (five hours to Toronto; an hour's wait; two-plus hours into London), the series was good enough to provide me with two nights of hotel, so I didn't have to worry about reading on a travel-day. I wandered leisurely across a Tuesday west along lakeshore, into, through, and beyond Toronto suburbs and into the wilds of Southwestern Ontario. The new Joyelle McSweeney title (which lands properly in April), I should have you know, is astounding. I can't even remember the last time I did a reading in London, Ontario (and I seem not to have done notes about such, although I know I read there circa 1998 or so) [but you saw my report on my prior reading, when I ventured in Toronto for Art Bar, yes?]. I spent the train ride there sketching out edits on my book-length genealogical essay (you are following along with posted excerpts of this work-in-progress via my substack, yes?), and the train ride home sketching out edits on short stories, along with moving through a small handful of previously-unread books as I stared out the window. Oh, the cold. Oh, the minus fourteen of London, Ontario.

I can't even remember the last time I did a reading in London, Ontario (and I seem not to have done notes about such, although I know I read there circa 1998 or so) [but you saw my report on my prior reading, when I ventured in Toronto for Art Bar, yes?]. I spent the train ride there sketching out edits on my book-length genealogical essay (you are following along with posted excerpts of this work-in-progress via my substack, yes?), and the train ride home sketching out edits on short stories, along with moving through a small handful of previously-unread books as I stared out the window. Oh, the cold. Oh, the minus fourteen of London, Ontario.Once there, I slipped and slid the two blocks from train station to hotel (which was chilly, admittedly, once inside), and had considered venturing out for proper food and a drink or two until I caught that the hotel had a CLASSIC DOCTOR WHO CHANNEL. How was I expected to leave the hotel after discovering that? I'd already been moving the past few weeks through the Tom Baker period, and managed to move further through Baker and into the Peter Davidson run. Some stellar stuff there. Interesting to see earlier stories that are later referenced in the reboot era (my knowledge of Doctor Who began with the 2005 reboot; I was vaguely aware of it as a youth, but I never quite managed to get into it then).

Wednesday morning I sat for an hour or so with coffee, bags and a notebook at a small place on the corner (working on drafts of short stories), and saw a car run a red light, which seemed stunning. Again, minus fourteen. Downtown London has an enormous amount of smoke shops, and businesses you need to ring into, and reminded me of downtown Winnipeg, or Vanier, with nicer/older buildings. I managed a couple of used bookstores, and even found copies of books by myself and Christine (and a copy of Jean McKay's Gone to Grass, which I finished reading while in hospital awaiting Aoife's birth); should I have picked them up? Cheaper than perhaps I paid for my author copies, most of them. Instead, I floated through the historical titles and picked up a couple of guidebooks from Upper Canada Village, hoping there might be some information there I require for my genealogical researches. I ended up at Moxies for lunch, which felt like nonsense, but most of the more interesting places looked a bit dodgy (including a pizza place that hadn't any windows, which is always a bit of a red flag). Stupid Moxies. The food was tolerable, and the televisions were relentless (Moxies requires a safe space, naturally, to allow no distractions while your soul slowly leaves your body). And then, I saw another car run a red light. Um, what?

Wednesday morning I sat for an hour or so with coffee, bags and a notebook at a small place on the corner (working on drafts of short stories), and saw a car run a red light, which seemed stunning. Again, minus fourteen. Downtown London has an enormous amount of smoke shops, and businesses you need to ring into, and reminded me of downtown Winnipeg, or Vanier, with nicer/older buildings. I managed a couple of used bookstores, and even found copies of books by myself and Christine (and a copy of Jean McKay's Gone to Grass, which I finished reading while in hospital awaiting Aoife's birth); should I have picked them up? Cheaper than perhaps I paid for my author copies, most of them. Instead, I floated through the historical titles and picked up a couple of guidebooks from Upper Canada Village, hoping there might be some information there I require for my genealogical researches. I ended up at Moxies for lunch, which felt like nonsense, but most of the more interesting places looked a bit dodgy (including a pizza place that hadn't any windows, which is always a bit of a red flag). Stupid Moxies. The food was tolerable, and the televisions were relentless (Moxies requires a safe space, naturally, to allow no distractions while your soul slowly leaves your body). And then, I saw another car run a red light. Um, what?

I had mentioned to Penn Kemp a week or so prior that I'd made a pilgrimage to the late Greg Curnoe's house at the end of July [see my note on such here], not wishing to bother his widow, Sheila, by what would have been a random stranger ringing her doorbell. I lingered on the street for a bit, which I was content enough with, at the time. Kemp (who had been Curnoe's assistant during a brief period in her teens: if you want to know more about that, I recommend James King's 2017 biography, THE WAY IT IS: The Life of Greg Curnoe, although the writing is a bit dry, which was surprising for such a lively subject and subject matter) was kind enough to respond by arranging a visit to the house, and Sheila and Penn picked me up at the hotel mid-afternoon (and we saw another car run a red light: that's three I saw on that day alone doing such). Sheila was such a delightful, generous host, and we sat and chatted the three of us in the Curnoe kitchen for a while before she took me into the studio, where Greg Curnoe (1936-1992) produced some twenty-plus years of artwork before his untimely death. I was there for a couple of hours, and it was completely glorious. We chatted, gossiped a bit (ahem), and Sheila was gracious enough to offer me copies of the original "big little" duo The Great Canadian Sonnet (Coach House Press, 1970) by David McFadden, that Curnoe did all the artwork for (a single reprint edition was produced through Coach House Books more recently; you should find a copy if you can).

I had mentioned to Penn Kemp a week or so prior that I'd made a pilgrimage to the late Greg Curnoe's house at the end of July [see my note on such here], not wishing to bother his widow, Sheila, by what would have been a random stranger ringing her doorbell. I lingered on the street for a bit, which I was content enough with, at the time. Kemp (who had been Curnoe's assistant during a brief period in her teens: if you want to know more about that, I recommend James King's 2017 biography, THE WAY IT IS: The Life of Greg Curnoe, although the writing is a bit dry, which was surprising for such a lively subject and subject matter) was kind enough to respond by arranging a visit to the house, and Sheila and Penn picked me up at the hotel mid-afternoon (and we saw another car run a red light: that's three I saw on that day alone doing such). Sheila was such a delightful, generous host, and we sat and chatted the three of us in the Curnoe kitchen for a while before she took me into the studio, where Greg Curnoe (1936-1992) produced some twenty-plus years of artwork before his untimely death. I was there for a couple of hours, and it was completely glorious. We chatted, gossiped a bit (ahem), and Sheila was gracious enough to offer me copies of the original "big little" duo The Great Canadian Sonnet (Coach House Press, 1970) by David McFadden, that Curnoe did all the artwork for (a single reprint edition was produced through Coach House Books more recently; you should find a copy if you can).

And, oh, this absolutely beautiful dollhouse Curnoe made for their daughter when she was young. Completely the kind of dollhouse that could only be produced by Greg Curnoe. Oh, Sheila Curnoe and Penn Kemp, thank you again for this kindness, this gift, of being allowed into this space. Pilgrimage, indeed. So very very cool. (I was abuzz most of the rest of the day, as you might imagine).

After being dropped back at the hotel for a quick bite (and further Doctor Who), one of the organizers collected me from the hotel DURING WHICH WE LITERALLY SAW ANOTHER CAR RUN A RED LIGHT; THAT IS FOUR TIMES I SAW CARS RUN RED LIGHTS IN A SINGLE DAY IN DOWNTOWN LONDON, ONTARIO. THIS IS CLEARLY A LAWLESS PLACE. The reading itself opened with "local opener" poets Sunday Ajak reading a couple of poems, followed by Katie Jeresky and Penn Kemp, who each read from their contributions to the three-poet chapbook (the third being Jessica Lee McMillan) Intent on Flowering (Rose Garden Press, 2024). Poet Kit Roffey was scheduled to be there to read from their recent 845 Press poetry debut, Civilian of Dirt (2023) [see my review of such here], but was under the weather, so publisher Aaron Schneider read in their stead (it is a really good chapbook debut, I should say). It was very good, also, to hear Karen Schindler read from her chapbook debut (I was startled to realize it was only her debut!) from Gaspereau Press, THE SAD TRUTH (2023) [see my review of such here]. And Tom Cull was there! Very good to meet him. And Jason Dickson! And Sarah Marie! And Tom Prime! It was a solid crowd, honestly.

And then I read!

photo of myself reading, by Misha Bower / Antler River Poetry

photo of myself reading, by Misha Bower / Antler River Poetry There was even a bit of a conversation after, during which host and moderator David Barrick asked a couple of us publisher-sorts (being Karen and myself as features, the evening had been framed as a small press event) about submitting, publishing and other sorts of things: Karen, myself, Aaron and the two Michelles (whom I had not previously met) from Rose Garden Press (I had a chapbook with them a while back; remember?).

There was even a bit of a conversation after, during which host and moderator David Barrick asked a couple of us publisher-sorts (being Karen and myself as features, the evening had been framed as a small press event) about submitting, publishing and other sorts of things: Karen, myself, Aaron and the two Michelles (whom I had not previously met) from Rose Garden Press (I had a chapbook with them a while back; remember?). After the reading, I convinced Aaron that we should head out for drinks, which was an awful lot of fun; he says we originally met at a pub once in Kingston, but I couldn't think of a time I was in Kingston out for drinks without doing a reading (he says there wasn't a reading; if there had been, he would have been there), so I have no idea when that would have been. Otherwise, it was good to spend time with him and get a better sense of him, his writing, his press, etcetera. I'm curious to see where 845 Press, and, for that matter,

The Temz Review

, goes next. He's doing some solid work.

After the reading, I convinced Aaron that we should head out for drinks, which was an awful lot of fun; he says we originally met at a pub once in Kingston, but I couldn't think of a time I was in Kingston out for drinks without doing a reading (he says there wasn't a reading; if there had been, he would have been there), so I have no idea when that would have been. Otherwise, it was good to spend time with him and get a better sense of him, his writing, his press, etcetera. I'm curious to see where 845 Press, and, for that matter,

The Temz Review

, goes next. He's doing some solid work. And then it was back to the hotel for some more Doctor Who, which began again with first light. Peter Davidson!

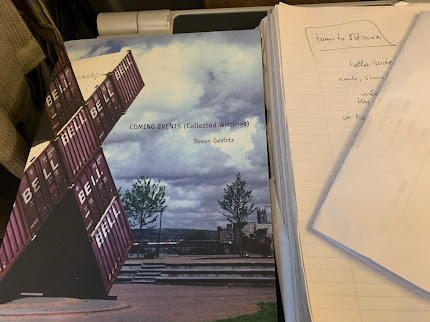

And then it was back to the hotel for some more Doctor Who, which began again with first light. Peter Davidson! And the train again, around 10am. Making notes and reading an interesting collection of collected writings by American poet and critic Susan Gevirtz, among other items. Back to Toronto, briefly. Back to Ottawa. All in all a glorious trip. Have you thought of heading out towards London?

And the train again, around 10am. Making notes and reading an interesting collection of collected writings by American poet and critic Susan Gevirtz, among other items. Back to Toronto, briefly. Back to Ottawa. All in all a glorious trip. Have you thought of heading out towards London?January 27, 2024

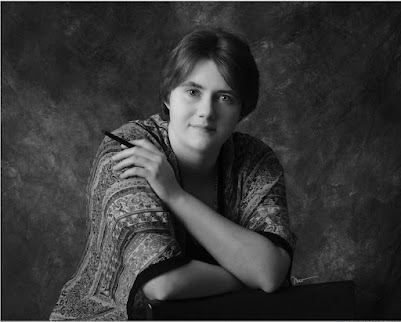

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Kelly Weber

Kelly Weber (they/she) is the author of We Are Changed to Deer at the Broken Place (Tupelo Press, 2022) and

You Bury the Birds in My Pelvis

,winner of the 2022 Omnidawn First/Second Book Prize (December 2023).They have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. Their work has appeared or isforthcoming in AGNI, Pleaides, Waxwing, Gulf Coast Online, ElectricLiterature’s The Commuter, Southeast Review, and elsewhere. Sheholds an MFA from Colorado State University. More of their work can be found atkellymweber.com.

Kelly Weber (they/she) is the author of We Are Changed to Deer at the Broken Place (Tupelo Press, 2022) and

You Bury the Birds in My Pelvis

,winner of the 2022 Omnidawn First/Second Book Prize (December 2023).They have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. Their work has appeared or isforthcoming in AGNI, Pleaides, Waxwing, Gulf Coast Online, ElectricLiterature’s The Commuter, Southeast Review, and elsewhere. Sheholds an MFA from Colorado State University. More of their work can be found atkellymweber.com.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Writing andpublishing my first book really changed my life in that the manuscript reallybecame this unexpectedly relational object. Collaborating with people to puttogether readings and events, having readers from around the world connect withthe book—it’s been a much more tender process than I expected, developing newconnections with people as a result of the book. With every book I hope to findways to be even more honest, and I think my recent work finds ways to do thateven more. I think this most recent collection, You Bury the Birds in MyPelvis, leans even further into lyric intimacy and my formal interests as apoet. I think with new work I’m also increasingly interested in deconstructingmy old approaches to work, so each book feels like a new attempt at poetry.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction ornon-fiction?

I really wanted tobe a fiction writer and tried hard at it for a long time, but I ultimatelyrealized I have no interest in dialogue, character, or plot. Form and languageare interesting to me, so I think poetry was the more natural fit even though Iresisted it for a long time. But poetry was mostly just a cold intellectualexercise for me for a long time. It took a lot of work and practice and diggingto finally reach a place of feeling in the work for me.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

It’s a really slow composting process as I basically freewrite my waythrough what interests me, and then poems gradually emerge. Sometimes I sitdown and write a poem that’s basically in its final shape, but that’s usuallylate in the process of drafting a book, or after a really long period ofjournaling.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of shortpieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

I feel like Icatch the tails of poems before I find where they start, as they sort of emergein a messy journaling process. It’s also really hard for me to write severalshort pieces that combine into a larger project. I find poems usually comebound up together, in a plural that’s hard to extricate from each other, so Ikind of have to write through a whole book and figure out what the form of thatbook is before the final poems reveal themselves and their individual shapes.Divisions between poems can feel really artificial to me. Sometimes that’sproductive for the work, sometimes it's not.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I really enjoy thecommunal aspect of the readings I’ve been a part of. I like how there can bethis special group attunement that happens at readings, in the same way thatI’ve heard theatre folks talk about becoming very attuned to what others intheir group are thinking / feeling as they work and act together. A goodreading can be a really sensory, even sensual, experience, and in the revisionprocess, I sometimes try to think about how it would feel to give a publicreading of a piece, even when the work is very experimental in form. Will thisbe impactful for an audience?

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kindsof questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even thinkthe current questions are?

I think thequestions are changing all the time for me. I’m not sure I could evenarticulate what they are—I feel like with every project I work on, I have towrite through several of them before the actual manuscript emerges with its ownset of questions. I do know that I don’t consider myself a very theoreticalperson at heart. I write about concrete things until something happens, maybe apoem, and then I look at the questions its asking from there.

7 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficultor essential (or both)?

Working with theTupelo and Omnidawn editorial teams to bring both collections into the world asfinalized aesthetic objects was absolutely crucial. Both teams were sobrilliant and thoughtful in all of the design choices and in bringing thesebooks into the world as beautiful objects for people to hold / engage with. Andboth teams published essentially what I submitted to them, with some finaledits from me, so it was interesting to really witness the manuscript becomethe final printed copy.

In terms ofdevelopmental editing, I’ve heavily relied on feedback from trusted friends onmanuscripts late in the revision process. Time is also a great editor—when Ispend enough time away from the work, the issues with a piece become morereadily apparent.

8 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily givento you directly)?

Ross Gay once saidthat counter to the advice he and many poets have been given—to just keep cutting,cutting, cutting a poem until it’s whittled down to only what’snecessary—sometimes you have to plant a garden in the middle of a poem instead.That radically changed my approach to everything in writing, especiallyrevision.

9 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even haveone? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I’m a morningwriter. I try to write at least an hour a day before work, etc. More when Ican.

10 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (forlack of a better word) inspiration?

I go back to thebooks I love and try to think about what I’m not understanding about thecurrent writing. Sometimes I just need a rest, but a lot of the time I can tellwhen I’m not understanding something essential about the work yet. I can tellwhen I’m trying to drive the work vs. the work is driving me, and getting tothe latter takes a lot of patience and a willingness to keep re-examining whatI want vs. what the work wants.

11 - What was your last Hallowe'en costume?

I love costumes,but I feel so self-conscious in them! I think one of the last ones I wore was awitch, but I didn’t enjoy it like I enjoyed looking at other people’s costumes.

12 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, scienceor visual art?

I think filmsinfluence me the most because of how image-driven they are, since I’m soimage-driven in my work. My dear writer friends Margaret F. Browne, MichelleThomas, and Megan Clark introduced me to so many lush queer and horror filmsthat have influenced all of us to some degree. I also find myself drawn totrailers for good films because the speed, compression, editing, and imagery(often without context) can feel like a poem in its movement, when it doesn’tjust feel like another piece of marketing.

13 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

Oh my gosh, thatlist could go on forever! Chen Chen, Jake Skeets, Victoria Chang, Solmaz Sharif, Kaveh Akbar, sam sax, torrin a. greathouse, Danez Smith, KB Brookins,K. Iver, Kay E. Bancroft, Kayleb Rae Candrilli, Diana Khoi Nguyen, Craig Santos Perez, Franny Choi, Ely Shipley, Lucien Darjeun Meadows, Natalie Diaz, Saeed Jones, Eduardo Corral, Cody-Rose Clevidence…

14 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I don’t knowexactly what that will look like next, but I hope every new book I write answersthat question. I can’t envision it until I have to write it.

15 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be?Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you notbeen a writer?

I really wanted todo environmental studies as a kid, and I think at heart I’m still fascinated byfield research. But I think the arts would always have to be a part of my lifesomehow, no matter what my occupation.

16 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

As much as I lovevisual art—I grew up in a household of visual artists—I just found myselfhooked into writing once I really tried it. I think I’m drawn to exploring theimage in written form, as opposed to on a canvas or through a lens, but it’s asimilar impulse to the other artists in my family.

17 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I just read TaylorByas’ I Done Clicked My Heels Three Times, which is brilliant. I alsorecently saw and really enjoyed Godzilla Minus One, both for theever-welcome return of Godzilla and the bigger questions and concerns the movieis thinking about.

18 - What are you currently working on?

Newpoetry! I don’t typically share anything about work while it’s in progress, sothat’s all I can offer for now.

January 26, 2024

Pattie McCarthy, extraordinary tides

form is content – contentis form – it is the only commandment

but there is no shape todays

the long border of anevening intertidal

never resolves itselfnever dissolves

never solves for anyvariable –

it is simply stretchedbeyond recognition

or usefulness – a king ofnothing

& nowhere – but if wewant

process not product –which we do – then

it will be evening allseason & we will stretch into it (“neap tide – autumn”)

Thereis something fascinating about the shift in Philadelphia poet Pattie McCarthy’slyric across her sleek new collection,

extraordinary tides

(Oakland CA:Omnidawn, 2023), a book that follows on the heels of her six prior full-lengthcollection, all of which appeared with Berkeley publisher Apogee Press: bkof (h)rs (2002), Verso (2004), Table Alphabetical of Hard Words(2010), Marybones (2013) [see my review of such here], Quiet Book(2016) [see my review of such here] and

wifthing

(Berkeley CA: ApogeePress, 2021) [see my review of such here]. McCarthy has long been engaged with the book as her unit ofcomposition, composing book-length lyric suites as thematic and structuralexaminations around language, history, gender, time and lost threads of thehistories of women (much of which focused on Medieval women), but there issomething quieter and more immediate about this particular poem, something akinto a moment of calm—almost a palate cleanser—as she stands on the shoreline,listens to the water and considers the horizon. “the sky keeps bright / eyes onus – we // look up into the cold / the tide makes,” she writes, as part of thesecond section, “a friction like / a song in glass // that is the tide sings / while it spins in glass //so deep midwinter the light turns iron / there is no end to your tongue [.]”

Thereis something fascinating about the shift in Philadelphia poet Pattie McCarthy’slyric across her sleek new collection,

extraordinary tides

(Oakland CA:Omnidawn, 2023), a book that follows on the heels of her six prior full-lengthcollection, all of which appeared with Berkeley publisher Apogee Press: bkof (h)rs (2002), Verso (2004), Table Alphabetical of Hard Words(2010), Marybones (2013) [see my review of such here], Quiet Book(2016) [see my review of such here] and

wifthing

(Berkeley CA: ApogeePress, 2021) [see my review of such here]. McCarthy has long been engaged with the book as her unit ofcomposition, composing book-length lyric suites as thematic and structuralexaminations around language, history, gender, time and lost threads of thehistories of women (much of which focused on Medieval women), but there issomething quieter and more immediate about this particular poem, something akinto a moment of calm—almost a palate cleanser—as she stands on the shoreline,listens to the water and considers the horizon. “the sky keeps bright / eyes onus – we // look up into the cold / the tide makes,” she writes, as part of thesecond section, “a friction like / a song in glass // that is the tide sings / while it spins in glass //so deep midwinter the light turns iron / there is no end to your tongue [.]”Setas a quartet of extended lyrics—“neap tide – autumn,” “[untitled yule tide],” “lent– in extraordinary tide” and “neap tide – spring”—McCarthy’s lines hold a deepmeditation across the opening and closing of the winter months, researched andresponsive, as is her way, but held across a sequence of moments, from tides throughthe difference of seasons. “the sky spangled with crows,” the second sectionoffers, “a night body of water // serrated wrack saw wrack toothed wrack / dulse spiraled tidy into // a whole universe [.]”

Thespace between her words, her lines, through this book-length suite areenormous, and allow for leaps and silence as connective tissue, providing thereader enough space and time to not merely fill in the blanks, but to employand occupy those silences that are as important as the words themselves. Towardsthe end of the second section, writing: “I don’t even know what’s good /anymore – I only know // what makes a pause – even / the smallest stop in therelentless // present tense – [.]” One could suggest the poem itself isentirely about perspective, from the perfect blend of form and content toincrements of time—from the markers of seasons, religious holidays and the tidesthemselves—to the very movement of birds, light and water. Given the dates sheprovides, the first autumn into winter, and winter into spring of pandemic lockdown,one could even see this meditation entirely as a response to a particular kindof Covid-era isolations; a Covid-era book that provides a tone, without asingle reference, beyond the dating of each of these quartet-stretches. Or, towardsthe end of the collection, as she writes:

& I have been inlanda while

the virgin of the dry tree

the tidal shift is not

seamless – even

the neaps mark

circatidal margins

whelks fast during neapcycles

unknot the fishing ropeto unrestrain

the wind – we werequizzed on the birds

we made flashcards of allthe trees

January 25, 2024

Rose finally gets a fish

1.

Her monthsof drawings, pressure ; reminders

to ourwhispered ears, to

plasteringthe fridge with several clones

of hersingle magnet-held artwork: “fish,” she writes, above

each sketchof same, “I want one.” I, for one,

hesitateto introduce a new character

into thishousehold menagerie, with the increased risk

of cancellingthe whole business. Richie’s brother Chuck

from HappyDays’ first season, or to simply

jumpthe shark.

2.

She wantsa fish. Demands: a petof her own,

to sharewith younger sister,

since Irefuse to entertain a dog ; ourcat

wouldtarnish, and my difficulty with lack

of unaccompaniedurban territory. A dog

requiresan excess unavailable. Ioriginated

from afarm ,after all, where dogs

possessthe amplitude

toroam. Preferring,also, not

a defecatedyard. Rose wants a fish, she

wantsa fish, she wants a fish. In case

themessage was unclear. She offers

promisesof pet care and routine,

hopingsomeone will believe her.

3.

Bellwether,prep; to establish and assemble her aquarium

beforeany fish might land. Rose plucks

acastle, mermaid , small plastic greenery; harvests

twosmall bags of coloured gravel. Her bearing, shifts,

she vibrates,crosswise; strums PetSmart shelves.

Each step

astop, a break inlinearity. She laughs,

aheadof her own debate. With fresh tank sidelining

her seasonale-learning retreat

offormer dining room, she holds: the soon-keeper

of thesacred fish.

4.

Thisbiological filter media.Her fishless

ten-gallonvessel, which will be,

soonenough. How water catches sound

inmotion, motion. Apparently boundless. This approximation

of asingle misstep, stanza,

verset,word. Once home, and set ,she stares, across

this dimpledglow of light-emitting diode

into oxygenatingwater.

January 24, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Walter Ancarrow

Walter Ancarrow

lives in New York City and sometimes Alexandria, Egypt. He is the author of

Etymologies

(Omnidawn, 2023), which won the 2021 Omnidawn Open.

Walter Ancarrow

lives in New York City and sometimes Alexandria, Egypt. He is the author of

Etymologies

(Omnidawn, 2023), which won the 2021 Omnidawn Open.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I’m not sure it did. I imagined it for so long that when it happened it seemed an inevitable extension of who I’ve always been. A second book has not been imagined as much, so when that happens…

2 – How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

My first poem was typed into the glowing blue screen of MS-DOS when I was five or six, and since then I've never stopped. The poem went:

There’s an alligator3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

in the refrigerator

he isn’t very nice

he’s eating all the ice

I've never kept a notebook but I do keep drafts. Etymologies emerged, like all of my writing, from play. I had stacked three words on top of each other merely because I found it visually appealing and therefore a poem:

ahuakatlSeveral years later I was looking through old drafts and realized these three words were telling a story. The story was not being told through the meanings of the words, which all mean avocado, but through how Nahuatl, Spanish, and English relate to each other, a relation that is always changing and that comes from outside of language.

aguacate

avocado

I knew this would be the opening poem. From there I had a conceptual framework and tried to write two or three poems a month. After two years the book was complete.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

One friend said I write in “systems” and another that my poems are “engineered.” What I think is meant by this is that my poems are very short but usually part of a larger conceptual apparatus. I take an idea and then think it through, all the way until my thought pokes out the other end.

This approach is especially true of Etymologies. For a book so influenced by linguistics, I wanted a quasi-structuralist feel in which the poems, some as short as two words, become meaningful through their relation to the poems around them, which may or may not add up to “a moiré pattern with associations emerging” as John Yau wrote in his illuminating introduction to my book. Language creates sense also in this way but ironically etymology does not.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

After my book came out, I had to remind myself why I write poetry and why I publish, because there is a lot of expectation to do readings, sit on a panel, lead a workshop, be social. Those are fine; sometimes I enjoy them. But they come a distant second to creation itself.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Many of the poems in Etymologies are ideas from philosophy of language. Naturally many of them are about origin. And some are about words that live on long after the mouth that shaped them has gone silent.

My background is in linguistics and for several years I worked for the Journal of Psycholinguistic Research under the late Robert Rieber, an expert on Vygotsky. One question psycholinguistics asks is how exactly we process language. There are no clear answers, which makes it great for poetry.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

It’s for non-writers to decide. Ask a poet and he will place himself on the highest pedestal.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

My best editor is the person my book is dedicated to. He is also my best reader. He is many other things to me but that will take another book to express.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“Rien n’est joué; nous pouvons tout reprendre.”

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

No routine and usually no writing!

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I let the problem bore a hole in my brain until what are sometimes called “creative juices” splash out.

12 - What was your most recent Hallowe'en costume?

The last time I dressed up was in 2019. I went as a gay Hezbollah member.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

As I mentioned in another interview, the soundtrack to Donkey Kong Country 2 for its lush minimalism. Similarly, Another Green World .

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Anything the Library of Arabic Literature publishes. What a mesmerizing, offensive, befuddling, mischievous, stereotype-smashing selection of texts! Included among these is Ahmed Faris al-Shidyaq’s As-saq ‘ala l-saq (usually translated as Leg over Leg), a sexually explicit dictionary-travelog that was important in writing Etymologies.

The Peterson Field Guide to Mushrooms for its precise color descriptions (“grayish brown to yellowish brown, sometimes flushed with olive in age”); The New Yorker’s insistence on diereses, which make bland words look like jungle insects (“coördinate”); the Wikipedia page on nuclear semiotics, which reads like the script to a Tarkovsky film; and the cute grocer boy who misspelled many words on the menu at the local deli, inspiring this.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

To leave my apartment one day and walk. Then to keep walking, city to city, town to town, land to land, on “man’s unending pilgrimage towards himself.”

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I hope to never consider poetry as an occupation. In another world, I'm an architect.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Because all it takes to write is imagination. It is the cheapest way to bring yourself into the world.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

This year I resolved to read more science fiction—a big gap in my literary knowledge. Stanislaw Lem seemed to have a nice prose style no matter his translator, so I bought a few of his books— His Master’s Voice , The Cyberiad , and Imaginary Magnitude —and finished all three in a week. It had been years since I was so enraptured by anything.

I don’t watch many movies. I’ve not for instance seen Solaris .

19 - What are you currently working on?

Many books, mostly in my mind. I will write them down when they are ready.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

January 23, 2024

Ian Seed, Night Window

Spoilt

For the historicalfiction workshop, one of my students brought in a prose poem. She’d also made abeef-and-radish sandwich for me to try, and wanted to know if it representedfood of the era in which her poem was set. All the ingredients are genuine, I said,but I feel it needs a little more salt, or perhaps pepper, since that’s thehealthier option, but then again, I added, perhaps that’s simply because mytaste buds have become spoilt over time. I was about to offer her a couple moretips when she picked up her books, snatched the half-eaten sandwich out of myhand, and walked out. The workshop always took place in an old, ratherbeautiful room, which had once been part of a vicarage. The students sat onchairs with folding tables set out in a horseshoe shape. The ceiling was soancient that sometimes it leaked, and I would find myself talking to themthrough the rain.

Thelatest from British poet Ian Seed, and the first I’ve seen of his ninefull-length collections, is

Night Window

(Swindon UK: Shearsman Books,2024), a collection set as three numbered sections of prose poems, the first poemof each—“Blessing,” “Geometry” and “Worth”—almost sit as thematic overviews of thosethree untitled sections. As the opening poem, “Blessing,” begins: “There was aheap of pink bubbles on the round table in the middle of the trattoria at thetop of the hill. I placed my hand over the bubbles and let it hover there for afew moments like a priest blessing a boy. The bubbles rose and solidified intothe form of a tall cake, but when I took my hand away again, the cake collapsedand dissolved back into bubbles.” The trajectory of the prose poem acrossBritish and UK literature is one I know extremely little of, but one that I gatheris far closer in overlap with the American prose poem than anything we’re doingin Canada. Seed’s poems give the sense of less akin to the short story throughlyric prose than a sequence of scene-studies, providing echoes with what I’veseen of the work of Russell Edson [see my review of

Little Mr. Prose Poem:Selected Poems of Russell Edson

, ed. Craig Morgan Teicher (Rochester NY:BOA Editions, 2023) here], as well as Seed’s own British contemporaries such asLydia Unsworth, Vik Shirley and Tom Jenks [see my recent review of their Beir Bua titles here]. His poems exist as prose blocks of sentences, set intonarratives that suggest straightforward narratives, but instead, lean andswerve, leap and deflect. Much like Edson, there’s something of Seed’s prosepoems that lean pretty hard into the postcard or very short story, offeringechoes of works by Lydia Davis, Stuart Ross and Gary Barwin, but one that holdsback with the insistence of the lyric, offering up to narrative conclusionsthat are left for the reader to discern. As he offered as part of his 2022 noteas part of the “short takes on the prose poem” feature for periodicities: ajournal of poetry and poetics: “The prose poems that I admire and enjoy arethose which take me into a different reality with its own logic, whether thatreality be a more abstract one or one shaped mainly by narrative.”

Thelatest from British poet Ian Seed, and the first I’ve seen of his ninefull-length collections, is

Night Window

(Swindon UK: Shearsman Books,2024), a collection set as three numbered sections of prose poems, the first poemof each—“Blessing,” “Geometry” and “Worth”—almost sit as thematic overviews of thosethree untitled sections. As the opening poem, “Blessing,” begins: “There was aheap of pink bubbles on the round table in the middle of the trattoria at thetop of the hill. I placed my hand over the bubbles and let it hover there for afew moments like a priest blessing a boy. The bubbles rose and solidified intothe form of a tall cake, but when I took my hand away again, the cake collapsedand dissolved back into bubbles.” The trajectory of the prose poem acrossBritish and UK literature is one I know extremely little of, but one that I gatheris far closer in overlap with the American prose poem than anything we’re doingin Canada. Seed’s poems give the sense of less akin to the short story throughlyric prose than a sequence of scene-studies, providing echoes with what I’veseen of the work of Russell Edson [see my review of

Little Mr. Prose Poem:Selected Poems of Russell Edson

, ed. Craig Morgan Teicher (Rochester NY:BOA Editions, 2023) here], as well as Seed’s own British contemporaries such asLydia Unsworth, Vik Shirley and Tom Jenks [see my recent review of their Beir Bua titles here]. His poems exist as prose blocks of sentences, set intonarratives that suggest straightforward narratives, but instead, lean andswerve, leap and deflect. Much like Edson, there’s something of Seed’s prosepoems that lean pretty hard into the postcard or very short story, offeringechoes of works by Lydia Davis, Stuart Ross and Gary Barwin, but one that holdsback with the insistence of the lyric, offering up to narrative conclusionsthat are left for the reader to discern. As he offered as part of his 2022 noteas part of the “short takes on the prose poem” feature for periodicities: ajournal of poetry and poetics: “The prose poems that I admire and enjoy arethose which take me into a different reality with its own logic, whether thatreality be a more abstract one or one shaped mainly by narrative.”

January 22, 2024

Buck Downs, NICE NOSE

FIVE SECOND RULE

all the dirt in my house

is created by me

or by the creatures

who feed on me

so I feel safe

eating any food

that hits the floor

Thelatest from Washington DC poet Buck Downs is the self-published

NICE NOSE

(2023), following on the heels of his chapbook-length

GREEDY MAN: selectedpoems

(Brooklyn NY: Subpress Collective/CCCP Chapbooks, 2023) [see my review of such here],

OPEN CONTAINER

(Washington DC: privately printed,2019) [see my review of such here] and

Unintended Empire: 1989-2012

(Baltimore MD: Furniture Press, 2018) [see my review of such here], amongmultiple other titles. Downs’ has long been an observational, thinking lyricthat veers into surrealism, but there’s been an interesting shift over the pastcouple of years, as he’s moved into shorter forms for the sake of posting poemsto Instagram (find him at @thesomethingfornothing), and subsequently, asstickers distributed around his home city of Washington. The scope of his poemsremain, but with further density; more punch than meander, although thatelement isn’t removed entirely. The development of an increased density and brevityin his poems for the sake of a publishing form is curious, and comparable to familydoctor and poet William Carlos Williams, who wrote poems that ran down the pagebut with short lines due to composing first drafts on prescription pads. Downs’surreal meditations and skewed humour, social commentary and quirky observations,“Passive-aggressive pro-mask propaganda, dusty riddles” and other elementsremain from what he’s previously published, but with a fascinating pared-downlyric compared to prior work. This is a fantastic book that requires repeatedreading; there is much packed into the quick quirks of his lines, more than youmight even imagine.

Thelatest from Washington DC poet Buck Downs is the self-published

NICE NOSE

(2023), following on the heels of his chapbook-length

GREEDY MAN: selectedpoems

(Brooklyn NY: Subpress Collective/CCCP Chapbooks, 2023) [see my review of such here],

OPEN CONTAINER

(Washington DC: privately printed,2019) [see my review of such here] and

Unintended Empire: 1989-2012

(Baltimore MD: Furniture Press, 2018) [see my review of such here], amongmultiple other titles. Downs’ has long been an observational, thinking lyricthat veers into surrealism, but there’s been an interesting shift over the pastcouple of years, as he’s moved into shorter forms for the sake of posting poemsto Instagram (find him at @thesomethingfornothing), and subsequently, asstickers distributed around his home city of Washington. The scope of his poemsremain, but with further density; more punch than meander, although thatelement isn’t removed entirely. The development of an increased density and brevityin his poems for the sake of a publishing form is curious, and comparable to familydoctor and poet William Carlos Williams, who wrote poems that ran down the pagebut with short lines due to composing first drafts on prescription pads. Downs’surreal meditations and skewed humour, social commentary and quirky observations,“Passive-aggressive pro-mask propaganda, dusty riddles” and other elementsremain from what he’s previously published, but with a fascinating pared-downlyric compared to prior work. This is a fantastic book that requires repeatedreading; there is much packed into the quick quirks of his lines, more than youmight even imagine.FAMOUS LAST WORDS

come on

what have

you got

to lose