Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 60

March 11, 2024

Rosa Alcalá, YOU: poems

You, Supplicant

Over sashimi tostados andchelas, you tell your girlfriends about the time you kneeled on the carpetedstairs that led to the bedroom of the guy who dumped you, pleading. O, his longhair—his thinness—like Jesus! They said they couldn’t see it. “You, for a man,begging?” And how his roommate gently lifted you to your feet, an act ofkindness like so many meted out in those days by men adjacent to another man’sdestruction. He was trying to pull you from the image of yourself, not asbeautiful but as a supplicant before beauty. A penitent whose suffering was thedeep and persistent condition of being a woman. It was, like dictatorship, likeFirst Communion, a perversion. You didn’t say this to your girlfriends. You movedon to translation problems, and your humiliations remained fuzzy backdrops,like bookcases in author photos.

Thefourth full-length collection by Texas-based poet Rosa Alcalá is

YOU: poems

(Minneapolis MN: Coffee House Press, 2024), “a collection of prose poetryexploring the intergenerational inheritance of gendered violence.” In astriking assemblage of lyric scenes composed via a suite of hefty prose poems, Alcaláwrites on age and of distance, gendered violence and teenaged exploration, focusingon points along the path from child to young woman to becoming and being the motherof a young daughter. “What I mean to say is that this book is still about mymother,” she writes, as part of the opening poem, “How It Started, How It’sGoing {An Introduction},” “that in the absence of her I mothered myself allover again with worry, / which is how I mother. // I spoke to myself, the onlyrecourse when you’re / invisible.” Alcalá composes her poems through anaccumulation of direct statements that unfold, unfurl, each sentence anothercard placed, face up, on the table. She is showing you her cards, more oftenthan not as a warning. “Everything was lies,” she writes, as part of the poem “YouLie,” “and there was nothing / to keep you from your own fabrications, noeternal fire.” And then, how to warn her daughter without gifting her a newtrauma; how to protect without offering frightening tales of what could happen,or what had happened to her.

Thefourth full-length collection by Texas-based poet Rosa Alcalá is

YOU: poems

(Minneapolis MN: Coffee House Press, 2024), “a collection of prose poetryexploring the intergenerational inheritance of gendered violence.” In astriking assemblage of lyric scenes composed via a suite of hefty prose poems, Alcaláwrites on age and of distance, gendered violence and teenaged exploration, focusingon points along the path from child to young woman to becoming and being the motherof a young daughter. “What I mean to say is that this book is still about mymother,” she writes, as part of the opening poem, “How It Started, How It’sGoing {An Introduction},” “that in the absence of her I mothered myself allover again with worry, / which is how I mother. // I spoke to myself, the onlyrecourse when you’re / invisible.” Alcalá composes her poems through anaccumulation of direct statements that unfold, unfurl, each sentence anothercard placed, face up, on the table. She is showing you her cards, more oftenthan not as a warning. “Everything was lies,” she writes, as part of the poem “YouLie,” “and there was nothing / to keep you from your own fabrications, noeternal fire.” And then, how to warn her daughter without gifting her a newtrauma; how to protect without offering frightening tales of what could happen,or what had happened to her.The“you” of Alcalá’s title suggests both singular and the multiple, from the narrator’semerging self to the multitude of male abusers to the narrator’s daughter, insteaddirected as the second-person “you” spoken by the narrator to and of thenarrator. “Run into a school if a man is chasing you. Run into a church. Fallin love / with art and mess up your dress.” she writes, to open the poem “YourMother’s Advice.” These are direct statements offered as wisdoms and warningsto the self, offering as both witness and document, declaration andexclamation. “That it was the only / thing you had to give.” she writes, aspart of the poem “What You Knew About Virginity,” “That once you handed itover, you could never get it / back.” Alcalá writes that this is a book abouther mother, but really, this is a book about her daughter, and attempting toclarify and come to terms with the past in order to properly communicate thoseconcerns, without offering trauma, to her own daughter. “In the early andlonely days of mothering,” she writes, to open the poem “You & the DyingLanguages,” “when you felt old at forty-one, / you’d examine pictures posted ofhomegrown arugula, read updates on / a chicken coop’s constructions, theadoption of a baby goat.” The poem offers a frustration of feeling useless as anew parent, unable to offer her daughter the language of her forebears, but in afurther poem, “Your Daughter Refashions the Flag into a Crop Top,” we see howthe narrator catches her daughter’s reactions, her confidences, writing: “Ceciliaonce thought she had to choose between poetry and painting, but / she no longerbelieves this and is recovering what was lost, rejected, sto- / len. To yourdaughter you bequeath what was left of the flag, and reject- / ing itsunflattering form, she refashions it into a crop top to show off / her midriff.She’s on the verge of something, that beautiful precipice.” Through a sustainedline of gestures and clear, perfect prose, Alcalá’s lyrics reach across the detailsof a life for the sake of questions, lessons and survival, working to breakthrough cycles of inherited violence. “Because your fathers fled a dictatorshiponly to set up their own,” she writes, to open the poem “While Your Fathers DidSecond Shifts,” a sentence that seems to hold the space of an entire universewithin, “and / took with them the belief that a woman shouldn’t enter a barunless it / was an emergency and had to use the pay phone, you shared with your/ cousins one eyeliner pencil, applying in rearview mirrors the blackest /breves to lower lids.” This is a collection of incredible strength and wisdom,much of it hard-won, but one that emerges out the other side, stronger forhaving not only survived, but thrived.

March 10, 2024

Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] : tenth anniversary sale,

To celebrate the tenth anniversary of the quarterly Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal]: anyone who subscribes (or resubscribes) anytime between now and the end of April 2024 has the bonus option of three (3) items: three Touch the Donkey back issues of your choice, OR three above/ground press (2023 or 2024) titles of your choice (while supplies last) OR any combination thereof.

OR: copies of ten (10) different back issues for $50 / copies of five (5) different back issues for $25 / copies of twenty different back issues for $100 / while supplies last on individual issues, naturally / add $5 for US orders ; add $10 for international orders,

Issue #41 of Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] (a slightly larger issue than usual) lands on April 15, 2024: with new work by Julie Carr, rob mclennan, Pattie McCarthy, ryan fitzpatrick, Conyer Clayton, Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Amanda Earl, Gil McElroy and John Barlow.

2023-2024 above/ground press titles include chapbooks by: Sacha Archer, Dale Tracy, Melissa Eleftherion, Kyle Flemmer, Saba Pakdel, Katie Ebbitt, Amanda Deutch, Phil Hall + Steven Ross Smith, Peter Myers, Terri Witek, Pete Smith, russell carisse, Micah Ballard, Clint Burnham, Angela Caporaso, Cary Fagan, Blunt Research Group, Gary Barwin, Lydia Unsworth, Kyla Houbolt, Zane Koss, Ben Robinson, Colin Dardis, Aaron Tucker, Adriana Oniță, Julie Carr + rob mclennan, Stephen Collis, Rae Armantrout, Jason Christie, Nikki Reimer, Noah Berlatsky, Miranda Mellis, MLA Chernoff, Marita Dachsel, Report from the fitzpatrick Society, Kevin Stebner, Meghan Kemp-Gee, Gil McElroy, Robert van Vliet, Stephen Cain, Geoffrey Olsen, Heather Cadsby, Evan Williams, Grant Wilkins, nina jane drystek, Sophia Magliocca, Jennifer Baker, Karen Massey, rob mclennan, Jérôme Melançon, Monty Reid, Jamie Hilder, George Bowering + Artie Gold, Ryan Stearne, Brad Vogler, Andrew Gorin, Report from the Pirie Society, Julia Drescher, Ken Norris, Joseph Donato, Samuel Ace, Stuart Ross, Leesa Dean, Report from the Reimer Society, Jessi MacEachern, G U E S T [a journal of guest editors] #26, Jordan Davis, The Peter F Yacht Club #32 : 2023 VERSeFest Special, Report from the Smith Society, Nick Chhoeun, Ben Jahn, William Vallières, Report from the Iijima Society, Derek Beaulieu, Isabel Sobral Campos, Mark Scroggins, Laura Walker, Report from the Trivedi Society, Nathanael O'Reilly, Lindsey Webb, Jason Heroux and Barbara Henning.

Touch the Donkey: Canadian subscriptions $35 for five issues / American subscriptions $40 / International subscriptions $50 / All prices in Canadian dollars /

To order, e-transfer or PayPal at at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com or the PayPal button at www.robmclennan.blogspot.com or www.touchthedonkey.blogspot.com

Issues are also available as part of the above/ground press annual subscription.

Because everybody loves a birthday. Who doesn’t love a birthday?

Touch the Donkey. Everywhere you want to be.

March 9, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Rose McLarney

Rose McLarney’s collections of poems are

Colorfast

,

Forage

, and

Its Day Being Gone

, from Penguin Poets, as well as

The Always Broken Plates of Mountains

, published by Four Way Books. She iscoeditor of

A Literary Field Guide to Southern Appalachia

, fromUniversity of Georgia Press, and the journal

Southern Humanities Review

.Rose has been awarded fellowships by MacDowell and Bread Loaf and SewaneeWriters’ Conferences; served as Dartmouth Poet in Residence at the Frost Place;and is winner of the National Poetry Series, the Chaffin Award for Achievementin Appalachian Writing, and the Fellowship of Southern Writers’ New WritingAward for Poetry, among other prizes. Her work has appeared in publicationsincluding American Poetry Review, The Kenyon Review, TheSouthern Review, New England Review, Prairie Schooner, Orion,and The Oxford American. Currently, she is professor of creative writingat Auburn University.

Rose McLarney’s collections of poems are

Colorfast

,

Forage

, and

Its Day Being Gone

, from Penguin Poets, as well as

The Always Broken Plates of Mountains

, published by Four Way Books. She iscoeditor of

A Literary Field Guide to Southern Appalachia

, fromUniversity of Georgia Press, and the journal

Southern Humanities Review

.Rose has been awarded fellowships by MacDowell and Bread Loaf and SewaneeWriters’ Conferences; served as Dartmouth Poet in Residence at the Frost Place;and is winner of the National Poetry Series, the Chaffin Award for Achievementin Appalachian Writing, and the Fellowship of Southern Writers’ New WritingAward for Poetry, among other prizes. Her work has appeared in publicationsincluding American Poetry Review, The Kenyon Review, TheSouthern Review, New England Review, Prairie Schooner, Orion,and The Oxford American. Currently, she is professor of creative writingat Auburn University.1 - How did your first book change your life?

I signed the contractfor my first book, The Always Broken Plates of Mountains (Four WayBooks), right after graduating from the Warren Wilson MFA Program for Writersand that must have been part of why I was chosen for a teaching fellowship inthe college’s undergraduate program. That teaching experience led me to applyfor more academic jobs, to be hired for some of them, and to move to all overthe country. The Always Broken Plates of Mountains was largely aboutfidelity to place, so it’s sort of perverse that it was the reason I left myjob with the Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project, family, and property.But the positive spin is that this is a case of one love leading me to others.

Also, my partner inthese repeated relocations was Justin Gardiner, a fellow writer I met whileteaching at Warren Wilson, and surviving uncertainties together led tomarriage, and a strong fidelity between us.

2. How does your most recent work compare to your previous ?

The book of mine thatmost stands apart from the others is Forage (Penguin, 2019), my thirdbook. While my other books center on Appalachia, Forage is more about mycurrent location, the Deep South, and the environment at large. And I put greatereffort into Forage than anything else I’ve ever done. Colorfast,my fourth and newest book, forthcoming from Penguin in March 2024, is a bit ofa return and I didn’t write it with any illusion that it would change mycareer. In it, I am again writing about the mountains where I grew up, thesubject I naturally turn to if I don’t direct myself otherwise. Yet, I amreexamining the stories about the culture and my own girlhood I have been toldand told myself and recognizing problems such as how the perspectives of womenand others were omitted.

Colorfast’s poems are more complex in their content than my firstbook’s, and they’re more advanced in their construction. My lines and stanzasare becoming more meticulously counted and shaped with each volume.

3 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

I’ve never had anycapacity for writing plot, conceiving of things happening. My mind wants tostay fixed in the moment and on a particular image and idea. I rememberreading, early on, in Lynn Emmanuel’s “The Politics of Narrative: Why I Am A Poet”: “So please, don't ask me for a little trail of breadcrumbs to get from the smile to the bedroom, and from the bedroom to the deathat the end, although you can ask me a lot about death. That's all I like, the very beginning and the very end. Ihaven't got the stomach for the rest of it.” That resonated with me, thoughshe’s got far more swagger than I ever will. When I began writing, I had verylittle time because I was holding down jobs in other fields (and working insome literal farm fields). Also, frugality was probably the highest virtue tome, then. I wanted to avoid the prosey task of explaining and the waste ofwords I thought it required.

Now I recognize that language inany genre can be subtle and economical, care at least as much about musicalityas economy, and like some little flourishes. But there’s still no chance of mewriting action scenes.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

My poems usually beginwith an impression or scrap of information jotted down in my journal. Then Imust figure out what I have to say about, what use I can make of, this materialI’ve gathered that may appear to have nothing to do with my own experiences orbe well outside areas in which I have expertise. For Colorfast, I minedinformation from reading about gemology, archaeology, natural dying, colortheory, and linguistics, among other subjects.

To start a book, I mustlet myself write all sorts of poems that may seem to be of separate species,until I can identify some larger concern or little characteristics they share.In Colorfast, feminist themes were obvious from the outset, but I wasalso aided in revising and sequencing by noticing details such as how often thepoems referred to hands and holding. After I have some general notions andgrace notes for a book, I can write with more purpose (and pleasure), creatingan arc for the manuscript, conversations between the poems, cohesion.

5 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

“Make do.” That advicemay have never been directly issued or verbalized to me. But it’s an aestheticthat helped with practicalities when I was younger—such as finding the charm indilapidated houses and learning how to wear secondhand clothes as if I intendeda vintage look—and helps now when I begin writing projects and worry that I’veused up the good stuff. It’s also a sort of exemplary piece of syntax. It’s economical,with just two words. It’s active, since both those words are verbs. And it’s acommanding imperative.

That said, I’m not asrigorous as I once was and I’m recalling the New Year’s Eve when a friendadvised me to “Resolve to be less resolved.”

6 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres(poetry to essays)? What do you see as the appeal?

I have writtenwhat may be a full-length manuscript of lyric essays. (I’ve been letting themsit, so I can come back and assess them with more objectivity.) It has not been easy. Transitions arethe problem—and I mean not just between genres, but between paragraphs andparts. As I said earlier, I’m wary of—bored by—explication and exposition. So,I’ve aspired to write prose with a line of reasoning running underneath, butthat, on the surface, leaps and seems to move from point to point by followingelements such as alliteration or off-rhyme as much as by argument.

I took on thechallenge of writing prose because I had information from research that was toocumbersome for poems to carry. Because there’s the possibility that people whodon’t read poetry will give an essay a chance (though they’ll find my essayscan actually be more heady than my poems). And, well, because I’ve completedfour books of poetry and it was a challenge.

7 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or doyou even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I start each morningby looking out the window before I let my eyes turn to any printed words orscreens. Then, I try to see that the first thing I read is a poem. Then, Iwrite something down in my journal—not any sort of narrative or record ofevents, just an observation. For instance, my last two journal entries arequotes from an overheard conversation between airport bartenders and anarchitectural text. Then, I go running and try to think about how what I’vewritten in my journal or drafted the previous day (though that’s gotten moredifficult as I’ve gotten older and more injured and have started to have tothink about the form of my body and the running itself). I will try to makesome revisions or expansions over breakfast.

If I am not going tocampus to teach or attending to other errands, I’ll work on typed drafts untilnoon. It’s useful to me to have that cut-off point so that I don’t stickrelentlessly, as I am prone to do, to a draft that isn’t going to amount toanything in the end, and so I don’t feel guilty about the laundry I’m nothanging and email I’m not answering—yet. (If you send me an email, I’ll answer you the same day, but not untilthe afternoon.)

8 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The house Justin and Ishare often smells like kafir lime leaves or cardamom or ginger. He mortar andpestle pounds roots and spices into curry pastes. I am heavy handed with anyspice available and like to improvise cultural mutt meals. (To be honest, a person who does not have ourcallous palettes may be greeted at the door with a cloud of air peppery enoughto make them choke.)

Underneath thosefragrances, there are notes of antique furniture--my grandparents’ and greatgrandparents’ old possessions I’ve drug around with me—and his many books. I’mglad you asked this question because the first portion of Colorfast hasa setting like my childhood home and deals with problematic relationships withmen. I appreciate a chance to mention my current home and the love poems, aftera reader makes it through the harder sections, in the latter part of thecollection.

9 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books,but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

Nature and biologyinform most of my work. I have no scientific training or taste for precisefigures and facts as firm answers. But I like to ask questions such as why snowmelts around trees, where it’s shaded, before it melts in open fields; somedead-looking leaves stay on tree branches into winter; and fossils form in somesoils and not others. Those inquiriesbecame poems in Colorfast.

I have published a fewekphrastic poems, yet I’ve probably written as many about the hushed atmosphereof museums—modern people exhibiting their most reverent behavior—as I have theactual art. And I may not have written any poems focused on music. Yet otherart forms undoubtedly influence my writing. My musical tastes, for example, aremuch edgier and more diverse than the kind of poem it is easiest for me togenerate. Music has inspired me to allow for some experimentation, dissonance,and noise in poems. In particular, musicians such as , who makesfolksy songs weird, innovative, and utterly his own, prompted me to avoidcliches associated with writing about rural America. (You can read more of my thoughts on music andlisten to a playlist I put together at Largehearted Boy.)

10- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, whatwould it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doinghad you not been a writer?

Veterinarians havetold me I should be a vet. I’m not squeamish in the least and I have much morepatience for and rapport with animals than the average human. I doubt I would enjoythe job, since vets meet animals when they’re distressed. And it’s an awfullynon-verbal alternative for a poet to choose. But at least I might be competentat it and I suppose both vocations involve plenty of perceiving of emotion andreading of implication and tone.

I am more certain ofthe job at which I’d be worst: valet. I hate cars and driving, and beingentrusted with (presumably) rich people’s fancy cars would wreck me.

11 - What was the last great book you read? What was the lastgreat film?

I read so much poetrythat it’s hard for me to choose one book to mention. So I’ll tell you the lastnovel that I loved: Milkman by Anna Burns. It is set in Northern Irelandduring The Troubles, and addresses political and cultural issues present inother countries and communities too, in some of the most colorful and originalprose I’ve encountered. I admire how elements of the style—never givinganyone’s proper name, for instance—aren’t only artistic touches, but tied tothe psychology of the people in the story, who must keep many secrets becausethey are under constant surveillance.

The film that’s stayedon my mind recently is Chocolat, directed by Claire Denis and set inCameroon (not the Johnny Depp movie). It’s from the ‘80s and, obviously,not American, but its commentary on race relations felt very relevant and itsapproach original. My husband found the film because Claudia Rankine referencesthe director in Citizen and Chocolat’s artful final scene, whichleft me with much to contemplate, felt like the conclusion of one of thosegreat poems that open out to more thoughts rather than closing down with apronouncement.

12 - What are you currently working on?

I already noted that Ihave been writing a collection of lyric essays. But, with my new poetry bookjust about to come out, it’s not the time for another publication. And I am tryingto put aside the validation of having the essays readily accepted by journalsand learn to gauge for myself what finished really is for my prose,since I’m a beginner in the genre.

I am also composingnew poems, because there will be a fifth collection someday. In order to helpme get out of essay mode and back to poetry, I assigned myself to draft withoutany capital letters or punctuation. This is hardly revolutionary, I know. Manypoets have written in this manner, including Ellen Bryant Voigt in herwonderfully refreshing Headwaters. But it’s a huge shift for me and, sofar, these poems are more fun than what I usually produce. That said, theycan’t contain as much information as essays and they don’t yet have theintricate craftmanship I tried to achieve in Colorfast and my othercollections. Maybe a current projectshould be remembering to celebrate Colorfast when it is finally in printand, rather than newness of style, the quality of endurance that is often whatthe poems are about.

March 8, 2024

VERSeFest : Ottawa's International Poetry Festival, March 21-24, 2024 :

VERSeFest, Ottawa's International Poetry Festival, returns for our fourteenth glorious year of events.

VERSeFest, Ottawa's International Poetry Festival, returns for our fourteenth glorious year of events.This year's festival, as part of our ongoing rebuilding year, will feature a wide range of award-winning performers in English and French.

A mix of readings and performances will allow participants and poets to gather once more under the roofs of some iconic Ottawa establishments. Read on for full location details.

At this year's festival, poets/performers will have copies of their books/chapbooks/cds on hand to sell. Please support them directly!

Thursday, March 21, 2024: Avant-Garde Bar, 135 Besserer Street, 7pm

Thursday, March 21, 2024: Avant-Garde Bar, 135 Besserer Street, 7pmAnita Lahey, Monty Reid, Marjorie Silverman, Laila Malik [pictured]

hosted by Jennifer Baker / Arc Poetry Magazine,

Daniel Groleau Londry, nina jane drystek, MayaSpoken

hosted by Allison Armstrong

Friday, March 22, 2024 : Happy Goat, 35 Laurel Street, 8pm

Friday, March 22, 2024 : Happy Goat, 35 Laurel Street, 8pmAmanda Earl, DS Stymiest, IAN MARTIN, Mary Lee Bragg

hosted by Stephen Brockwell

Susan McMaster, Sneha Madhaven-Reese [pictured], Shane Rhodes

hosted by rob mclennan

Saturday, March 23, 2024 : Redbird, 1165 Bank Street, 8pm

$12 for the evening: available here

Jaclyn Piudik, Chris Turnbull, Mark Goldstein, Derek Webster

hosted by rob mclennan

Sandra Ridley, David O’Meara, Madeleine Stratford [pictured]

hosted by Zishad Lak

Sunday, March 24, 2024: Spark Beer, 702 Somerset Street West, 8pm

Sunday, March 24, 2024: Spark Beer, 702 Somerset Street West, 8pmAJ Dolman, Myriam Legault-Beauregard, Nduka Otiono,

hosted by Madeleine Stratford

Jason Christie, Klara du Plessis+ Khashayar “Kess” Mohammadi

hosted by rob mclennan

check out our website for further information, including full author biographies.

for information/queries: rob_mclennan@hotmail.com

March 7, 2024

Spotlight series #95 : Adriana Oniță

The ninety-fifth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Edmonton/Sicily-based poet, educator, translator, researcher, editor and publisher

Adriana Oniță [photo credit: Shawna Lemay].

The ninety-fifth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Edmonton/Sicily-based poet, educator, translator, researcher, editor and publisher

Adriana Oniță [photo credit: Shawna Lemay].

The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon, New York-based poet Emmalea Russo, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz, San Francisco poet Maw Shein Win, Toronto-based writer, playwright and editor Daniel Sarah Karasik, Ottawa poet and editor Dessa Bayrock, Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia poet Alice Burdick, poet, writer and editor Jade Wallace, San Francisco-based poet Jennifer Hasegawa, California poet Kyla Houbolt, Toronto poet and editor Emma Rhodes and Canadian-in-Iowa writer Jon Cone.

The whole series can be found online here .

March 6, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Michael B. Tager

Michael B. Tager is stardust currentlyin the form of the author of Pop Culture Poetry: The Definitive Edition(Akinoga Press, ’24), and Managing Editor of Mason Jar Press.1. How did yourfirst book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to yourprevious? How does it feel different? The first book I "really" readwas The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. I was in 2nd grade and itwas like "oh, books can do this? They can transport me away entirely andmake me forget about everything else? Well I'm into that!" It was quite amoment and I never looked back. As for how it relates to my current writing?When I write prose, I often lean into magic and/or the unexplained. I'm a genreboy at heart. But I tend to write more poetry these days, and poetry about popculture as opposed to fantasy. Maybe I'll write a thing about Turkish Delight,or my deep confusion at Christian iconography (cause I'm Jewish and that wholeJesus parallel went woosh over my head!)

2. How did youcome to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction? I came to poetry wellafter prose! I have never taken a poetry course, either lit or writing. So thefact that my first book is poetry is an irony not lost on me. I came to poetrybecause it allows me to be weird more than prose. Maybe because I was nevertaught in poetry, I don't have any bad habits that I need to break, like I dowith prose. Plus I can be really vulnerable and hide it in imagery and funphrases, which is harder (for me) than in prose. In fiction, I layer myown self a bit too deep and in nonfiction I fight the vulnerability at everysingle step. Poetry is a happy medium for me!

3. How long doesit take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initiallycome quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close totheir final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes? When I'm writing--whichisn't now--I have two ways I come to writing. The first is that I have a settime every day in which to write on current projects or on new ideas. The otherway is that when inspiration strikes, it doesn't matter what I'm doing, I haveto get a pen or a computer and just start writing as much as possible,because I've learned that if I ignore inspiration, it goes away. Shockingright? Now, when I get into a project, the writing comes fast-fast-fast. I'vebeen known to write a 5,000 word story or 10 poems in one sitting. Revising cantake longer, but first drafts? That's not slow at all.

4. Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are youan author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or areyou working on a "book" from the very beginning? Skipped

5. Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process?Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings? I like performing! I haveminors in theater and speech communication, I have done dance performances anddebate, I've given presentations at conferences and trainings. I like karaokeand I've done weird experimental art exhibits. So, performing isn't a barrierto me. It isn't part of my process or anything, and I don't write for theperformance, but I enjoy giving readings. I don't like what leads up tothe reading (because stage fright and general introvertedness) but once I'm onstage, it's all downhill.

6. Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you tryingto answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are? I'mtrying to get back to the weirdo I was when I first began writing. That senseof fun and play that MFA and general adulthood beat out of me. It's why I amdrawn more to poetry these days; it's the genre I have the least experience inand by far the least training. I'm able to access that "fuck it"mentality that eludes me in prose. So while I don't have any particularconcerns or theoretical roots that I'm exploring, I do have a goal, which is tocapture that childhood uniqueness.

7. What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be? Writers are artists and artistsare the soul of culture. No one remembers Odysseus because of his awesomeness,we remember him because a dope ass book was written. Without artists, there'sno memory. You're welcome, world.

8. Do you find the processof working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)? I LOVEworking with an editor and I find it easy as pie. Possibly because I'm aneditor, but also because I love collaboration and I love people telling me howto make my stuff better. Improve me, daddy!

9. What is the best pieceof advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)? I was at an SF&F panel when I was a baby writer and they were all smart genre writerstalking. One jabroni in the audience asked about money and you could feel thepanelists' eyes rolling. one of them said something along the lines of there'sthree reasons to me to write. The first is because you want to getpaid--in which case you should just follow the career paths and writing stylesof Stephen King or Jodi Picoult or something, or just write cookbooks. Thesecond is because you only feel the need to write and create--in which case whocares about money--or even being published. The last--and the reason I writeand probably my colleagues--is because you want people to read you and thinkabout what you think. We like money and we'd like to make a full living bythis, but it's not the main concern. So, my advice is to figure out why you'rewriting and go from there. Don't start at the money.

10. How easy has it been foryou to move between genres (poetry to prose)? What do you see as the appeal? Pretty easily! One thing leads to another and beingaround brilliant creative people gives ideas and thoughts that I want to try.Plus, I get bored and need to experiment or I lose my mind. But I also findthat one informs the other. My poetry makes my prose prettier, my fiction makesmy nonfiction (incidentally my least favorite genre and one I really only dothese days when paid) more interesting, my nonfiction helps me get to the pointin my fiction, and the prose helps me keep my head out of my ass with poetry.It's a circle.

11. What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin? Well, I'm not writing at all now since I have kids and twojobs and a press but eventually that'll change. (answered routinequestion above)

12. When your writing getsstalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration? Either physical activity in order toempty my brain of all the stuff clogging it: working out, walking, dancing,etc., or other forms of entertainment. By that I mean video games, movies, cardgames like Magic the Gathering, and stuff like that. I've written severalstories inspired by video games, for example. Get the inspiration from otherplaces!

13. What fragrance remindsyou of home? What fragrance reminds you of home? I'm more triggered by physicalsensations than smell, so also the weight of light jackets, warm sun and chillbreeze, walking for hours without sweating or shivering. Yeah, that's thestuff.

14. David W. McFadden oncesaid that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influenceyour work, whether nature, music, science or visual art? (see 12)

15. What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work? My favorite book is Startide Rising byDavid Brin, which is hard sci fi about space dolphins. I love pulpy fantasy anddetective stories. I cut my teeth on Dragonlance and earlyStephen King. in other words, given the choice between never reading literaryfiction or genre fiction again, I'd be like "fuck you lit fiction."Even though I primarily write lit fiction and poetry, I get most of myinspiration from other venues.

16. What would you like todo that you haven't yet done? skipped

17. If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer? If and when Iswitch careers again, I'm going into hospitality. Being a concierge, or making eventsat a hotel (weddings, cons, whatever) would be my jam. I'm good at it!

18. What made you write, asopposed to doing something else? I don't know. Does anyone know? I'm justbiding my time on this earth until I die and writing makes me happy. I’man optimistic nihilist: nothing matters, so let’s have fun and make everythingbrighter and cheerier before the void swallows us whole. I like writing, I’mgood at it, I recognized that early so I guess fuck it let’s write some books?

19. What was the last greatbook you read? What was the last great film? I haven't read a book in two yearsbut the best storytelling I've read is the video games Hades. It's a rogue-likewherein each game is different, and it's designed to kill the hell out of you.In between deaths, you talk to characters from Greek myth like Thanatos,Persephone, Hades (duh), Cerberus, Achilles, the Furies, and so on. Thebackstories, romances, subversions of myth that are parsed out over 50-100hours are absolutely brilliant. Video games have become art. It's afact. As for film, you don't really want to open that can of worms. I cango on. But, ummmm, Hunt for Red October was pretty baller. I missed it when itcame out and so watched it. It was dope.

20. What are you currentlyworking on? NOTHING! I have two kids, my parents now live with me, two jobs, asemblance of a social life, a wife, and a press that I run (which satisfiesmost of my artistic cravings). When the baby goes to day care and my wifegoes back to (paid) work so I can decrease my hours, I'll probably write again.Until then, I have no guilt at not writing.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

March 5, 2024

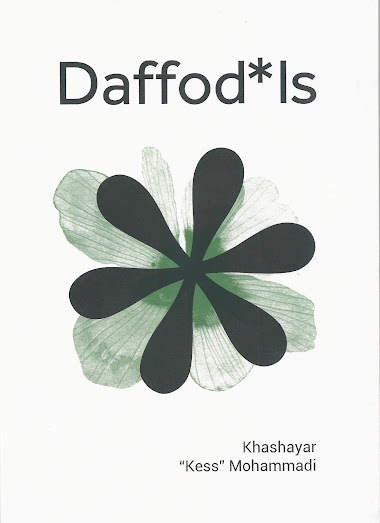

Khashayar “Kess” Mohammadi, Daffod*ls

I have no space forhumility

lets manifest destinyourselves out of poverty

let’s lift ourselves outfrom poetry and

sit in penthouses

lets steal w*ne in the nameof c*vil d*sobedience

and sit on the bed-bugsmeared mattress

reading WALDEN arm in arm

until friends leave

until everyone

and everyone

moves out

I’vebeen increasingly interested in what UK-based international publisher Pamenar Press has beenproducing lately (see my review of the Laynie Browne trio from last year, which included a title they produced), and the latest I’ve seen is by Toronto-basedpoet, writer and translator Khashayar “Kess” Mohammadi, the book-length suite

Daffod*ls

(Pamenar Press, 2023). This is Mohammadi’s third full-length collection,following

Me, You, Then Snow

(Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2021) [see my review of such here] and the dos-a-dos WJD conjoined with TheOceanDweller, by Saeed Tavanaee Marvi, trans. from the Farsi by Mohammadi (GordonHill Press, 2022) [see my review of such here]. Mohammadi is also the author ofthe recent and collaborative G with Klara du Plessis (Palimpsest Press,2023), and already has a fifth full-length poetry collection, Book ofInterruptions, scheduled for fall 2025 with Wolsak and Wynn. Structured verydifferent than his first two collections, both of which suggest chapbook-lengthworks conjoined into a larger unit, Daffod*ls is composed as abook-length suite, moving and flowing as a single unit of individual, accumulatedlyric sections. The shift is interesting to witness, and one many poets have doneover the years (I think back to Toronto poet Kevin Connolly’s infamous debut AsphaltCigar, for example), watching in real time as a poet’s attention expands beyondthe chapbook and into the collection. Set as an assemblage of slightly surrealfirst-person observations, musings and commentaries, Daffod*ls is a book-lengthlyric suite across more than a hundred pages of sweep and nuance, offering anexpansive gesture into history, time and language. There’s a heft here, onethat requires careful, repeated readings, even through what at times mightappear a kind of rush. Through the space of Daffod*ls, Mohammadi utilizesthe lyric form and space as a means of study, through which to explore thecollisions, contusions and conflicts that emerge through the eyes of a narratorsituated within and between two weighty world cultures. “I miss behind firmly satin the middle of a patch of dirt you / can claw into. Its finished. skyscrapersno longer scrape the / sky. clouds have all moved out of our town. I used towrite / differently so speak to me NOW, through the noise my hand / ispiercing. you’ve got the right idea, sitting with coffee table / magazines andtuned into classical music.” There’s something of the inconsistent puncutationsand capitalizations, and the asterisks, also, that provide a particular kind ofimmediacy, propelling the lines across the page, offering an urgency to theseexplorations, these declarations.

I’vebeen increasingly interested in what UK-based international publisher Pamenar Press has beenproducing lately (see my review of the Laynie Browne trio from last year, which included a title they produced), and the latest I’ve seen is by Toronto-basedpoet, writer and translator Khashayar “Kess” Mohammadi, the book-length suite

Daffod*ls

(Pamenar Press, 2023). This is Mohammadi’s third full-length collection,following

Me, You, Then Snow

(Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2021) [see my review of such here] and the dos-a-dos WJD conjoined with TheOceanDweller, by Saeed Tavanaee Marvi, trans. from the Farsi by Mohammadi (GordonHill Press, 2022) [see my review of such here]. Mohammadi is also the author ofthe recent and collaborative G with Klara du Plessis (Palimpsest Press,2023), and already has a fifth full-length poetry collection, Book ofInterruptions, scheduled for fall 2025 with Wolsak and Wynn. Structured verydifferent than his first two collections, both of which suggest chapbook-lengthworks conjoined into a larger unit, Daffod*ls is composed as abook-length suite, moving and flowing as a single unit of individual, accumulatedlyric sections. The shift is interesting to witness, and one many poets have doneover the years (I think back to Toronto poet Kevin Connolly’s infamous debut AsphaltCigar, for example), watching in real time as a poet’s attention expands beyondthe chapbook and into the collection. Set as an assemblage of slightly surrealfirst-person observations, musings and commentaries, Daffod*ls is a book-lengthlyric suite across more than a hundred pages of sweep and nuance, offering anexpansive gesture into history, time and language. There’s a heft here, onethat requires careful, repeated readings, even through what at times mightappear a kind of rush. Through the space of Daffod*ls, Mohammadi utilizesthe lyric form and space as a means of study, through which to explore thecollisions, contusions and conflicts that emerge through the eyes of a narratorsituated within and between two weighty world cultures. “I miss behind firmly satin the middle of a patch of dirt you / can claw into. Its finished. skyscrapersno longer scrape the / sky. clouds have all moved out of our town. I used towrite / differently so speak to me NOW, through the noise my hand / ispiercing. you’ve got the right idea, sitting with coffee table / magazines andtuned into classical music.” There’s something of the inconsistent puncutationsand capitalizations, and the asterisks, also, that provide a particular kind ofimmediacy, propelling the lines across the page, offering an urgency to theseexplorations, these declarations.brace for the itch

brace for all the itches!

when I came here therewere still thoughts here

dear Daffod*ls:

WHAT IS THE EASIEST WAYTO AVOID SWEETNESS

there’s this practice of restraint

honed only in teeth

the soil that cultivates

b*tter ol*ves

I’mcurious at Mohammadi’s use of the asterisk, switching out the letter “i” from wordsfor reasons not entirely clear to my reading. I’m reminded of Roy Kiyooka’s useof the word “inglish,” offering a shifted perspective on a language not hisfirst, and one approached with and through caution, aware of the cultural baggageheld by his adopted language. Through Mohammadi, the shift is visual above all,and one might wonder if this might be a play on the narrative “I,” thesuggestion of a forceful presence even through the absence; what can neither beremoved or completely obscured. And yet, Mohammadi switches out the letter onlywithin words, not solo, so the effect is predominantly visual, suggestinghighlight or even a kind of drift, beyond pure language. Might this be a daffodilset within the very word? “I swear,” Mohammadi writes, fairly early in thecollection, “I’m reading up on pedagogy / and by the discussion / I promise I willunderstand! / and subtitled with an aster*sk / is a muddy delta of sedimentedthoughts / with my cat / nibbling on my toes / and hands / Infinite in theircapacity for wonder [.]”

I attest: half my wordshave disappeared from the dictionary

so I guess this is mylanguage now

whats up?

whats wrong?

whaddya need now?

I don’t have space rightnow

March 4, 2024

Klara du Plessis, I’mpossible collab

“There isn’t a full stopanywhere,” [Dionne] Brand writes in “Verso 14” of The Blue Clerk. “Butwhat do you need a full stop for? You have the end of the line. The full stop isirrelevant. A full stop is really not even a point to discuss. Why discuss afull stop when you have a line? A line ends, and that is what that is.” In contrastto narrative, which Brand feels needs a full stop to hedge in its inherentlinearity and determinism, poetry embodies openness. Lineated poetry isstructured in such a way that there is always open space on the page where aline breaks off, so that a line doesn’t need to be marked by a period. The endof a line fulfills the function of a full stop without its conclusion closure. AsBrand summarizes, a line “ends yes as you say, but it doesn’t conclude.” (“CENTERINGTHE FULL STOP”)

Itis such a delight to read the thoughtful, thinking prose of Montreal-based poet, writer and critic Klara du Plessis, made more possible through the tenessays collected in her

I’mpossible collab

(Kentville NS: GaspereauPress, 2023), an expansion upon the chapbook-length

unfurl: Four Essays

(Gaspereau Press, 2019) [see my review of such here]. As the back cover of I’mpossiblecollab offers, the collection “asserts the collaborative nature of literarycriticism […],” and is made up of “ten essays discussing works by contemporaryCanadian poets such as Jordan Abel, Oana Avasilichioaei, Dionne Brand, AnneCarson, Kaie Kellough, Annick MacAskill, Erín Moure, M. NourbeSe Philip, andLisa Robertson, [as] scholar and poet Klara du Plessis explores the critic’sinterpretive agency and the valuable playfulness of pursing our own insights,proposing a more fluid, organic, and open-ended approach to how we think andwrite about poetry.” The prose and thinking in these pieces absolutely sparkle,and I’m fascinated in how these pieces might not have originally been composed towarda collection but emerged as and into one, able to catch the ongoing threads ofconcerns and conversations on writing, thinking and form (and honestly, herpiece on Dionne Brand alone is worth the price of admission). Her pieces are simultaneouslyexpansive and precise, offering such a level of glorious detail across a widearray of reading. In “BLUE INK & THE DEFERRAL OF SILENCE,” an essay on thereissue of M. NourbeSe Philip’s Looking for Livingstone. An Odyssey ofSilence (The Center for Expanded Poetics, 2018), du Plessis writes: “Silenceand language coexist and interrelate. The word for silence is a breaking ofsilence, and silence persists in the word for word. The narrative now adopts atheoretical edge, apt for thinking that happens at least partially in poetry.”

Itis such a delight to read the thoughtful, thinking prose of Montreal-based poet, writer and critic Klara du Plessis, made more possible through the tenessays collected in her

I’mpossible collab

(Kentville NS: GaspereauPress, 2023), an expansion upon the chapbook-length

unfurl: Four Essays

(Gaspereau Press, 2019) [see my review of such here]. As the back cover of I’mpossiblecollab offers, the collection “asserts the collaborative nature of literarycriticism […],” and is made up of “ten essays discussing works by contemporaryCanadian poets such as Jordan Abel, Oana Avasilichioaei, Dionne Brand, AnneCarson, Kaie Kellough, Annick MacAskill, Erín Moure, M. NourbeSe Philip, andLisa Robertson, [as] scholar and poet Klara du Plessis explores the critic’sinterpretive agency and the valuable playfulness of pursing our own insights,proposing a more fluid, organic, and open-ended approach to how we think andwrite about poetry.” The prose and thinking in these pieces absolutely sparkle,and I’m fascinated in how these pieces might not have originally been composed towarda collection but emerged as and into one, able to catch the ongoing threads ofconcerns and conversations on writing, thinking and form (and honestly, herpiece on Dionne Brand alone is worth the price of admission). Her pieces are simultaneouslyexpansive and precise, offering such a level of glorious detail across a widearray of reading. In “BLUE INK & THE DEFERRAL OF SILENCE,” an essay on thereissue of M. NourbeSe Philip’s Looking for Livingstone. An Odyssey ofSilence (The Center for Expanded Poetics, 2018), du Plessis writes: “Silenceand language coexist and interrelate. The word for silence is a breaking ofsilence, and silence persists in the word for word. The narrative now adopts atheoretical edge, apt for thinking that happens at least partially in poetry.”Thisis a remarkable collection, and there is something I very much appreciate in duPlessis’ approach, the notion of collaboration between reading and writing, textand reader, offering an experience she brings to any material that can’t helpbut interact with her own individual approaches to writing. She offers herpieces in conversation, which seems almost the opposite of the JohnMetcalf critical declarative, offering a critical engagement as bothreader and practitioner that informs her responses but refuses to automaticallydirect those same responses. These essays, as well, provide an argument for howevery writer should attempt to explore or examine their reading in criticalprose, whether as a review or an essay. Such a process forces a deeper kind ofreading habit, one I know full well: there are plenty of poetry titles I didn’tfully comprehend or appreciate until attempting my way through composing areview. “When poetry faces its public,” she offers, as part of her introduction,“ESSAYS, AS SAY—,” “the welcoming gesture is implicit.” As she continues,further on:

When I write essays, it is a collaboration. Poetry uncollarsitself from the illusion of essentializing definition, and I bring myself notonly into interpretation but also into openness as an author and thinker inrelation to texts. What I write about is poetry. how I write about it is as apoet myself, but also from my positionality as a person. Reciprocal generosityoverlays and merges literature and literature. There is a minimalism to thisconceptualizing of collaboration, one which does not invite poets to producenew work with me or on my behalf, but which assumes that when art exists in theworld, it renews itself through dialogue. If another were to write essays aboutthe same sequence of poetries, it would result in an altogether different book.

March 3, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Sabrina Reeves

Sabrina Reeves

grew up in Boston and New York and currentlylives in Montreal. She founded the performance company Bluemouth Inc., withwhom she’s written and staged over twelve original works and performed all overthe world. She was awarded the Dean of Arts and Sciences Award for Excellencein Creative Writing upon completing her MFA at Concordia University in 2018.

Sabrina Reeves

grew up in Boston and New York and currentlylives in Montreal. She founded the performance company Bluemouth Inc., withwhom she’s written and staged over twelve original works and performed all overthe world. She was awarded the Dean of Arts and Sciences Award for Excellencein Creative Writing upon completing her MFA at Concordia University in 2018.1- How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent workcompare to your previous? How does it feel different?

It feels like I’vebeen handed a permission slip to continue writing prose. My background is in writingfor theatre and performance, texts that are meant to be spoken aloud. I’m sure thereare writers who find performing their writing more daunting than simply leavingit on the page. But I find it much easier to perform my words than to trust thepaper to convey all the emotion. There are no qualifiers, no added emotions orgestures on the page. The words must speak for themselves. Did I choose theright ones? What if my ideas change and I later disagree with myself? There isa permanence to writing that is daunting. Also, the sustained focus of long-form prose was a new challenge for me. Building sentences that add up to sectionsthat add up to chapters that connect necessarily one to the other to build toan inevitable ending requires a very particular and sustained focus—and a fair numberof rewrites!

2- How did you come to performance texts first, as opposed to, say, poetry,fiction, or non-fiction?

I have been anactor for several decades. I co-founded the Toronto-based performancecollective Bluemouth inc. I think it was in this transition from performing inother people’s work to creating my own that my affinity for writing becameclear.

3- How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

It’s a bit ofboth. Some of the chapters were written in one sitting and have changed verylittle since that first draft, while others have been worked over and over—someof the chapters I’d probably still be fiddling with if not for the deadline.

4- Where does a work usually begin for you? Are you an author of short piecesthat end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

I would say thereare multiple parts to my process. In the beginning, I like to have several differentideas percolating simultaneously. I collect bits of this and that: sentences,observations, research, free writing, etc., and then loosely file them underdifferent project headings. The part of my brain that plans and has ideas aboutwhat I should write about is, unfortunately, not a very good writer. My controlledside is a bit too controlling; it doesn’t allow for anything unexpected, and sothe writing is stilted and dry. I do, however, find constraints very freeingonce I start to know what I’m working on. Nothing to do with content, strictlyform. For example, write sections of exactly 15 lines each, write lots of them,write until you have 20 pages worth and organize those into a coherent piece.Or write a page without using the letter S. Sometimes, those constraintsshort-circuit the “control freak” side of the brain and remind the creativeside that it has its own organizational logic and to trust that.

5- Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sortof writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doingreadings.

6- Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

This may seemredundant, but I am drawn to the power of story. I have friends in differentartistic disciplines, mostly dance and visual art. And sometimes they ask mefor feedback, and I can’t help but put a narrative to what I see, even if whatthey’re doing is, for example, exploring the color blue. I believe in Joan Didion’s line, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” I suppose that hassomething to do with how I approach writing. I am drawn to women’s stories, mentalhealth issues, generational trauma, and the opioid epidemic, for example. But Ibelieve personal stories have the power to resonate on a mythic level, and sowould always approach any issue through personal narrative. One of my favoritewriters is Claire Keegan. Most of her stories are deceptively simple, usually setin Ireland, or some small rural place where not many people live, in a timethat is unspecified, featuring humble characters, and I don’t think she’swritten anything longer than a novella. So, never some grand issue-based opus.And yet, every single one of her stories hits me like she has reached acrosscontinents, stuck her hand in my chest and touched my heart. Images of theatomic bomb come to mind; each story, an atom that annihilates. Even the simpleststory can hold tremendous power.

7– What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Doess/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think the roleof the fiction writer is to make big issues personal by transmuting facts intostory.

8- Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Not difficult atall. For me, particularly writing something autobiographical, it provedessential. At times, I couldn’t see the forest for the trees; Shivaun reallyhelped me find the throughline.

9- What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

“The cave youfear to enter holds the treasure you seek.” Joseph Campbell

I think everyday, almost every moment we have the choice not to be afraid, to choose life.We are so driven by habit, but many of our habits came into being to protect usfrom things we were afraid of. It can be a daily effort to remind oneself thatwe have choices; we don’t have to still be afraid of things we were afraid ofas children.

10- How easy has it been for you to move between genres (performance texts/playsto fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

Two of the mostimpactful books I read when I was younger were Faulkner’s The Sound and the Furyand Woolf’s The Waves. I didn’t realize it was “allowed” to write novelslike that. That rulebreaking that defined Modernism had a profound effect onme.

11 - What kind ofwriting routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does atypical day (for you) begin?

I free write everymorning. And I keep a small notebook with me to collect thoughts andobservations as they arise throughout the day. In nice weather, I walk on themountain (in Montreal) in the morning and then write in a café afterward. Lotsof thoughts come to me when I’m walking. The afternoons are a bit lesspredictable. I’d love to say, “I sit at my desk for three hours everyafternoon.” But that’s not true. I have two kids and my life is unpredictable.Sometimes I get more writing done in the afternoon, but sometimes not.

12- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

Free writing,observation, and unusual writing constraints

13- What fragrance reminds you of home?

Lilacs.

14- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

Little Crosses was heavilyinfluenced by the landscape of the southwest. In general, being in a verydifferent landscape or climate or city than the one I live in makes me noticemore. It awakens my curiosity. Another thing that inspires me: I have a lot offriends in the dance community and my daughter is a dancer, so we go to a lotof dance shows. When I am at a dance show, I am often flooded with ideas andimages. Dance is so much about architecture of space and rhythm and tone, andoddly there is something about plotting that is similar. The necessity ofarchitecture and orchestration. Often I will bring a very small pad of paperand a pen when I go to a show and I surreptitiously take notes.

15- What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

Toni Morrison, Cormac McCarthy, James Hillman, Louise Erdrich, Claire Keegan, Jenny Offill, George Saunders, Miriam Toews, Joseph Campbell, Fyodor Dostoevsky, William Faulkner,and Virginia Woolf.

16- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Live somewhereelse for an extended period. Japan and Ireland come to mind.

17- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

I would love tobe a farmer or run a small bookshop. Not exactly an exciting response, butthere you have it. I have no desire to skydive or hike the Himalayas, thoughthat would be a more exciting answer.

18- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Though mycreativity takes various avenues, it is always fueled by storytelling. Iconsider myself a beginner in writing fiction, but in storytelling and dialogueand creating scenes that evoke emotion, I feel comfortable saying that this iswhat I do. From years of performing my writing in front of an audience, I havegained an immediate visceral sense of how to connect with an audience throughwords.

19- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I just finished LydiaDavis’s collection Our Strangers, which I loved and Dennis Lehane’s SmallMercies. And last week I saw the film American Fiction, which I reallyenjoyed.

20- What are you currently working on?

Various shortpieces, that will likely turn into longer pieces.

March 2, 2024

some recent substack posts: reading in the margins + the genealogy book,

I’vebeen working a couple of threads over at

my incredibly clever substack

over thepast few months, most of which has been my ongoing genealogical non-fictionproject, “the genealogy book,” exploring new genealogical threads as well asseeking further details along previously known genealogical threads, working myfamily histories in multiple directions, now that I’m aware of the biological threadsof my adopted-self (

here's a recent example

). I’ve been working this particular manuscript since June oflast year, and have been finding out some really fascinating details and connections,and the comparisons between my previously-known self (McLennan/Campbell/Aird/Page/Swain/Friend andother lineages throughout) against the newly-explored biological threads(Adams, etcetera) I’m finding pretty interesting. The biological lines havebeen over here far longer, for example, including numerous United EmpireLoyalist lines (which I haven’t had before this), leaning into some prettyneat stories, connections and lengthy histories across Dundas County, the War of 1812, New England and the American Revolution, none of which I thought I had any connection to.

I’vebeen working a couple of threads over at

my incredibly clever substack

over thepast few months, most of which has been my ongoing genealogical non-fictionproject, “the genealogy book,” exploring new genealogical threads as well asseeking further details along previously known genealogical threads, working myfamily histories in multiple directions, now that I’m aware of the biological threadsof my adopted-self (

here's a recent example

). I’ve been working this particular manuscript since June oflast year, and have been finding out some really fascinating details and connections,and the comparisons between my previously-known self (McLennan/Campbell/Aird/Page/Swain/Friend andother lineages throughout) against the newly-explored biological threads(Adams, etcetera) I’m finding pretty interesting. The biological lines havebeen over here far longer, for example, including numerous United EmpireLoyalist lines (which I haven’t had before this), leaning into some prettyneat stories, connections and lengthy histories across Dundas County, the War of 1812, New England and the American Revolution, none of which I thought I had any connection to.Myother ongoing thread is a series of short essays on fiction writers, “readingin the margins: a writing diary,” with the most recent piece is on London,Ontario writer Jean McKay, focusing on her 1983 “autobiographical novel” Goneto Grass (Coach House Books). Naturally, this is a book I highly recommend,if you can find a copy. Previously posted pieces across this same series includewrite-ups on Gail Scott, Joy Williams, Ernest Hemingway, Bobbie Louise Hawkinsand Kristjana Gunnars. I’m slowly (very slowly, it might seem) working onfurther pieces, on Dany Laferrière, LM Montgomery and Sheila Heti, amongothers. We shall see how far it goes.

I’vealso been posting the occasional short story (here's a good one), from a manuscript I’ve been slowlycarving over the past few years, a follow-up to this fall’s On Beauty(University of Alberta Press), a book already on pre-order, I might add. I’vealso been sprinkling through some small bits of flash fiction, a manuscriptnearly a decade in-progress (an example, here), furthering The Uncertainty Principle: stories,(Chaudiere Books, 2014), a book still available through Invisible Publishing.

Priorto that, I’m sure you saw all the excerpts from the “Lecture for an Empty Room”non-fiction project, focusing on reading, literature and community (here's my piece on John Cage, for example, as part of such), “A riverruns through it: a writing diary,” my lengthy essay on collaborating with Denver poet Julie Carr and the lengthy essay (posted in two parts: one and two) on the thirtiethanniversary/history of above/ground press! There’s also been a piece or two on “theblue year,” a writing journal/diary from 2019-2020 that I have yet to rework (an example, here), ahefty manuscript from a period of father illness (als), my weekends attending care and his eventual death, new half-siblingdiscoveries, Christine’s health crises and eventual pandemic (there was a lot toprocess during that period, honestly). I’m hoping to get into that again at some point,once the genealogical project is further along. Also, I’m hoping to get backinto the novel I began in 2021, one that furthers some threads from On Beauty,so once I’m there I’ll start posting those as well. There are other threads too, but I'll let you figure that out on your own. Beyond that, who knows? Really, this whole substack process I deliberately began to push me further into a couple of prose directions, assisting to get pieces furthered, furthered and finished. Having the weekly slot does provide a good impetus for getting a piece done.

Rightnow I’m attempting to post weekly (although recently I accidentally posted twopieces recently on the same day, oops), with every third or fourth piece for payingsubscribers only. I mean, I’m attempting to treat this like a weekly column, ina certain way, but it would be nice to have a few dollars in my pocket also,along the way. And can you believe I'm only 9,750 away from ten thousand subscribers?