Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 375

July 17, 2015

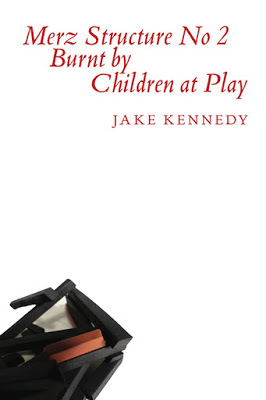

Jake Kennedy, Merz Structure No. 2 Burnt by Children at Play

1. That It Is Madness to Judge the True at the False from Our Own Capacities

So there could be a party for the celebration of our absurd expectations…—please join us for The Brittle Years and for the recitation of the elegy entitled “Our Finest Earlier Pronouncements or Boy Are We Jerks”—with all the guests holding crystal Y’s: their empty questions, really—which (let us) fill with sand or the guts of watches or Kool-Aid—ah, the best writing says: we are stupid and beautiful, keep it up! (“Giant Omen”)

Kelowna, British Columbia poet and editor Jake Kennedy’s third poetry collection is the absurdist and sincerely earnest

Merz Structure No. 2 Burnt by Children at Play

(Toronto ON: BookThug, 2015). Following The Lateral (Montreal QC: Snare Books, 2010) and Apollinaire’s Speech to the War Medic (BookThug, 2011), this new book concerns itself with discovery and being lost, and how one can only truly be achieved through the other, composing a series of striking poems deliberately meant to occasionally unsettle, forcing a deeper attention of his incredibly sharp and precise poems that shift from meditation to improvisation, and tight lyric to prose poems, and even include a sequence of poems composed as billboard-style single sentences. Kennedy’s poems delight in the mix of classical reference, meditative lyric and mischievous speech, tossing in the occasional line or phrase of casual diction, or a pop reference that at first might seem entirely out of place. Kennedy revels in the play between the two—high and low culture, high and low speech—and shows the possibilities of what poetry can become through the blending of worlds too commonly kept apart in contemporary poetry (think also of David McGimpsey’s self-titled “chubby sonnets”).

Kelowna, British Columbia poet and editor Jake Kennedy’s third poetry collection is the absurdist and sincerely earnest

Merz Structure No. 2 Burnt by Children at Play

(Toronto ON: BookThug, 2015). Following The Lateral (Montreal QC: Snare Books, 2010) and Apollinaire’s Speech to the War Medic (BookThug, 2011), this new book concerns itself with discovery and being lost, and how one can only truly be achieved through the other, composing a series of striking poems deliberately meant to occasionally unsettle, forcing a deeper attention of his incredibly sharp and precise poems that shift from meditation to improvisation, and tight lyric to prose poems, and even include a sequence of poems composed as billboard-style single sentences. Kennedy’s poems delight in the mix of classical reference, meditative lyric and mischievous speech, tossing in the occasional line or phrase of casual diction, or a pop reference that at first might seem entirely out of place. Kennedy revels in the play between the two—high and low culture, high and low speech—and shows the possibilities of what poetry can become through the blending of worlds too commonly kept apart in contemporary poetry (think also of David McGimpsey’s self-titled “chubby sonnets”).A Brief History of the Tornadoes of Oxford County, Ontario

Because the future needs spacethe wind makes a field

the labourer himselfand the crow further on

in order to place two keyholesin the horizon

what gives up as the sun gives upto obtain other reputations: down

or anyway going towards gone—one does not believe in assurance

I don’t at least—only vulnerabilitiesas different stages of imam-blow-yer-fkin-shack-down

their threats and this relinquishing:a cow, then a church

moving above the trees.

Much like his previous collection, Apollinaire’s Speech to the War Medic, Merz Structure No. 2 Burnt by Children at Play, Kennedy concerns himself with history, citing a variety of historical figures and their works including Camille Claudel, René Char, Cezanne, Stan Brakhage and even Harold Ramis, as though, through them, working through his own sense of the contemporary. As he writes in “A Brief History of the Cemeteries of Huron County, Ontario”: “for those who do or no not / reach into their past like darkened rooms[.]” His poems move from elegy to lyric fragment, exploring a looseness (in comparison to McGimpsey, certainly) that allows his poems a particular quality of lightness, and a cadence of sound and collision that nearly make one want to read each piece aloud.

Composition 2

To be all, especially a body. Look, a a well has coherence but no singleness of focus; nothing within it (you) is irrelevant. The body as array; you have a wish to make a thread fused to another: ordering them, you give the way you want, while the other, ordinary body deals with its singleness by focusing attention on time. In other words, you lose the “logically”—you look to unity to be irrelevant digressions and unnecessary shifts in points of view: “you” as rearranging body: your disrupted singleness: a wish in a well.

Published on July 17, 2015 05:31

July 16, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Marie Buck

Marie Buck

is the author of the poetry collections

Life & Style

(Patrick Lovelace Editions, 2009) and

Portrait of Doom

(Krupskaya, 2015), and she teaches literature and writing in Brooklyn. Some of her recent poems appear in Poems By Sunday, a Perimeter, and Fanzine. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?My first book, Life & Style, came out in 2009. I was super happy to have the work out in the world, and the fact that the book was out in the world also put me in touch with a lot of interesting poets in other places. So, one great thing was just being part of a larger aesthetic community. Krupskaya put out my new book, Portrait of Doom, this past spring. The projects are pretty different. One key difference, I think, is that, while both projects are partially collaged, I’m not really interested in the Internet with this new one. With the first, I was interested in publicity and privacy, especially in relation to gender. I grabbed a lot of language from MySpace accounts; the Internet at that moment was a really good thing to use in thinking about the things I wanted to think about. Now, though, I feel pretty uninterested in the Internet and also like we’re in a very different cultural moment in the wake of Occupy and with the ongoing Black Lives Matter movement, Greek resistance to austerity, the general uptick in resistance across the globe. So I guess I want/expect my work to reflect this larger cultural shift. I’m really interested in political affect, the transmission of political affect, and moments of collective hope and disappointment. I’m drawing on broader range of sources that I collage from (in addition to writing from scratch). That said, all of my work seems to wind up circling around a few things: power, the grotesque, quotidian expressions of power relations, political and personal angst as one and the same, bodies, over the top self-reflexivity on the part of the speaker. 2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?Hmm. I wrote both poetry and fiction initially, and I found I liked writing poetry more most of the time. In high school, I read Sylvia Plath’s Collected Poems over and over, despite mostly reading fiction at that point. Then in undergrad, I took classes with a really amazing professor, the poet Carol Ann Davis, who created a fantastic writing community at the College of Charleston. So I had a lot of room to write in different genres, explore, read friends’ work. I ended up mostly delving into poetry and then went on to the M.F.A. program in poetry at the University of Massachusetts. I do sometimes write fiction and creative essays, though.3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?For the past couple of years, I’ve collected bits of language into my phone and into various draft files. The bits of language are things that I’ve overheard, things from conversations I’ve had, things from specific television shows or movies that I might watch because I'm interested in the register of language they use, things from specific documents that I might look up because I’m interested in something thematically. Then when I want to write, I start working from that language but end up writing a lot from scratch, too. I move things around, recontextualize, etc etc. and come up with something that is a poem eventually. Later I’ll go back and edit a few times. Giving a reading or submitting poems motivates me to do the editing part. (I seem to have to imagine a specific and immediate audience in order to do it.) I use Scrivener (which I find much better to work in than Word) to write and also to figure out how a manuscript is going to work. 4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?In between projects, I write short pieces. It takes me a while to figure out what it is I’m doing. But once I have something in mind to assemble, something that I’ve hit on that I want to keep working with, I’m writing the project by writing individual poems. And I incorporate repetitions, threads, etc. 5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?Oh yeah, I love reading. Readings are fun. And helpful—I can’t totally know if a poem is working until I read it out loud, in front of people. Not so much because of feedback, but because I become a much better evaluator of my own work then.6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?Ha! This is a very big question! I feel like I kind of hit some of this with question 1, actually. But, to be more specific: right now I am very interested in thinking about political hope and disappointment—how these affects work, how they might play into the formation of collectivities. Right now there is a lot of up and down, social movements springing up but only briefly, heavy repression, lack of organization. I’m interested in thinking about contemporary hope and disappointment through thinking about the 1970s and 1980s. I was born in 1982. Myself and anyone roughly my age grew up in the wake of the 60s—i.e., in this larger cultural mood of expectation for better things, and simultaneously, deep disappointment that the movements of the 60s didn’t bring about more substantive change. I’m intrigued by

Star Trek

, right now, for instance. Compare its vision of the future to contemporary visions of the future. I'm thinking of, say, Children of Men (which is a fantastic movie). We all picture dystopia now. Literally no one even imagines a world like in Star Trek, where humans have eliminated want. No one imagines things progressing. Pretty much everyone imagines things getting worse and worse. If I’m feeling really depressed about the state of the world, sometimes I’ll just watchStar Trek and remember that this made sense as a piece of cultural production just a couple of decades ago, and that cheers me up a bit. So—Star Trek isn’t in my poems in any direct way, but Star Trek and various other relics of the post-60s era are spurring me to hash out some questions in my work. 7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?Well, poetry communities are always kind of their own thing I guess. But in a less stupid world, everyone would have a lot more time to be creative, and a lot more people would be writers. There would be more arts funding. People would have access to thriving aesthetic communities everywhere. 8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?Hmm—is “outside” here someone outside of whoever is publishing your work? I’ve been edited mostly by friends and by editors publishing my work, and I pretty much always find it extremely helpful. Krupskaya’s editors, Stephanie Young, Brandon Brown, Jocelyn Saidenberg, and Kevin Killian, were amazing to work with. For instance, Stephanie helped me tremendously with some issues with capitalization and other nitty gritty things that ran throughout the manuscript and were small, but pervasive and so really important for the work. I was so glad for the help. 9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?Hmm. I'm really not sure; perhaps I have not received any good advice. Please advise me, readers! 10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?I don’t have a regular poetry writing routine, though I do usually set deadlines and other goals for myself. A typical day involves dissertation writing and research, and sometimes teaching, and sometimes poetry. 11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?Books, TV. Going to readings. Seeing art. Consuming culture, basically. 12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?I used to live in an apartment in Detroit that was too close to a garbage incinerator. I live in Brooklyn now, and NYC famously smells like hot garbage. So I’m gonna go with hot garbage. 13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?Oh yeah, totally. Certainly visual art, certainly film, certainly political theory. The most exciting thing I’ve seen recently is the exhibit America Is Hard to See at the new Whitney. It’s huge, and sort of all-encompassing and amazingly curated to let you really think through historical themes and moments. I was really into the Jeff Koons retrospective at the Whitney last year, too. 14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?Lately, David Wojnarowicz, specifically his collection of essays

Close to the Knives

. Emily Dickinson. James Baldwin. 15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?Incorporate more narrative elements into my writing. 16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?Professional athlete with a dual appointment as a socializer of feral cats. 17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?As a teenager, I was really interested in making visual art too. But writing seems to come much more naturally to me. I have a lot more control over words; I can work them into what I want, or figure out the shape of something I want to make through the process. With visual art, I don’t really have the technical skill, among other problems, so I’m always kind of flailing around and can’t get things to actually work. 18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?The last book I read is

Black Against Empire

, a history of the Black Panther Party. It’s a really carefully researched, analytically sharp book. Fiction-wise: I recently read Jacqueline Susann’s The Valley of the Dolls, Mary McCarthy’s The Group, Rona Jaffe’s The Best of Everything, and Muriel Spark’s The Girls of Slender Means in quick succession and they were amazing—I’m really interested in this midcentury female bildungsroman subgenre that I've only recently discovered. Also, Phillip K. Dick’s Do Android’s Dream of Electric Sheep?, James Baldwin’s Another Country, and Marilyn French’s The Women’s Room, which is this really great second wave feminist classic. Also, Henry Dumas’s collected short stories, Echo Tree, which I keep coming back to. Dumas was a Black Arts Movement writer who ought to be better known than he is—he wrote these amazing Black Arts magical realist stories. I moved to New York recently and so now I read fiction when I’m on the train. I’ve probably read more fiction in the last five months than in the previous five years—it’s great.Poetry-wise: Alli Warren’s Here Come the Warm Jets, Steven Zultanski’s Bribery, Anna Vitale's chapbook Unknown Pleasures. Lots of other things too, but I'll stop there. Films: I recently saw Gregg Araki’s Mysterious Skin for the first time, and it’s probably one of the best movies I’ve ever seen. I also saw Jennifer Phang’s Advantageous, which just came out and is excellent—about austerity and dystopia and set in a future that is basically now. TV-wise: I’ve been getting into

Bob’s Burgers

, which, is hilarious and also has this thing I really like where all the characters are sympathetic characters, and additionally they all get along with each other. It’s super sweet about people’s relationships to one another, basically, even though the humor of the show is pretty cynical. That sweetness reminds me of Freaks and Geeks, one of my other favorites. At some point maybe I’ll write something about the politics of this sweetness. 19 - What are you currently working on?I’m in the final stages of completing a Ph.D. right now, so I’m finishing a dissertation project about the cultural production of the Women’s Liberation and Black Power movements. The new poetry project I have going doesn’t have a title yet, but it seems to be a sort of sequel to Portrait of Doom—but starting from a place of political disappointment.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Marie Buck

is the author of the poetry collections

Life & Style

(Patrick Lovelace Editions, 2009) and

Portrait of Doom

(Krupskaya, 2015), and she teaches literature and writing in Brooklyn. Some of her recent poems appear in Poems By Sunday, a Perimeter, and Fanzine. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?My first book, Life & Style, came out in 2009. I was super happy to have the work out in the world, and the fact that the book was out in the world also put me in touch with a lot of interesting poets in other places. So, one great thing was just being part of a larger aesthetic community. Krupskaya put out my new book, Portrait of Doom, this past spring. The projects are pretty different. One key difference, I think, is that, while both projects are partially collaged, I’m not really interested in the Internet with this new one. With the first, I was interested in publicity and privacy, especially in relation to gender. I grabbed a lot of language from MySpace accounts; the Internet at that moment was a really good thing to use in thinking about the things I wanted to think about. Now, though, I feel pretty uninterested in the Internet and also like we’re in a very different cultural moment in the wake of Occupy and with the ongoing Black Lives Matter movement, Greek resistance to austerity, the general uptick in resistance across the globe. So I guess I want/expect my work to reflect this larger cultural shift. I’m really interested in political affect, the transmission of political affect, and moments of collective hope and disappointment. I’m drawing on broader range of sources that I collage from (in addition to writing from scratch). That said, all of my work seems to wind up circling around a few things: power, the grotesque, quotidian expressions of power relations, political and personal angst as one and the same, bodies, over the top self-reflexivity on the part of the speaker. 2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?Hmm. I wrote both poetry and fiction initially, and I found I liked writing poetry more most of the time. In high school, I read Sylvia Plath’s Collected Poems over and over, despite mostly reading fiction at that point. Then in undergrad, I took classes with a really amazing professor, the poet Carol Ann Davis, who created a fantastic writing community at the College of Charleston. So I had a lot of room to write in different genres, explore, read friends’ work. I ended up mostly delving into poetry and then went on to the M.F.A. program in poetry at the University of Massachusetts. I do sometimes write fiction and creative essays, though.3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?For the past couple of years, I’ve collected bits of language into my phone and into various draft files. The bits of language are things that I’ve overheard, things from conversations I’ve had, things from specific television shows or movies that I might watch because I'm interested in the register of language they use, things from specific documents that I might look up because I’m interested in something thematically. Then when I want to write, I start working from that language but end up writing a lot from scratch, too. I move things around, recontextualize, etc etc. and come up with something that is a poem eventually. Later I’ll go back and edit a few times. Giving a reading or submitting poems motivates me to do the editing part. (I seem to have to imagine a specific and immediate audience in order to do it.) I use Scrivener (which I find much better to work in than Word) to write and also to figure out how a manuscript is going to work. 4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?In between projects, I write short pieces. It takes me a while to figure out what it is I’m doing. But once I have something in mind to assemble, something that I’ve hit on that I want to keep working with, I’m writing the project by writing individual poems. And I incorporate repetitions, threads, etc. 5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?Oh yeah, I love reading. Readings are fun. And helpful—I can’t totally know if a poem is working until I read it out loud, in front of people. Not so much because of feedback, but because I become a much better evaluator of my own work then.6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?Ha! This is a very big question! I feel like I kind of hit some of this with question 1, actually. But, to be more specific: right now I am very interested in thinking about political hope and disappointment—how these affects work, how they might play into the formation of collectivities. Right now there is a lot of up and down, social movements springing up but only briefly, heavy repression, lack of organization. I’m interested in thinking about contemporary hope and disappointment through thinking about the 1970s and 1980s. I was born in 1982. Myself and anyone roughly my age grew up in the wake of the 60s—i.e., in this larger cultural mood of expectation for better things, and simultaneously, deep disappointment that the movements of the 60s didn’t bring about more substantive change. I’m intrigued by

Star Trek

, right now, for instance. Compare its vision of the future to contemporary visions of the future. I'm thinking of, say, Children of Men (which is a fantastic movie). We all picture dystopia now. Literally no one even imagines a world like in Star Trek, where humans have eliminated want. No one imagines things progressing. Pretty much everyone imagines things getting worse and worse. If I’m feeling really depressed about the state of the world, sometimes I’ll just watchStar Trek and remember that this made sense as a piece of cultural production just a couple of decades ago, and that cheers me up a bit. So—Star Trek isn’t in my poems in any direct way, but Star Trek and various other relics of the post-60s era are spurring me to hash out some questions in my work. 7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?Well, poetry communities are always kind of their own thing I guess. But in a less stupid world, everyone would have a lot more time to be creative, and a lot more people would be writers. There would be more arts funding. People would have access to thriving aesthetic communities everywhere. 8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?Hmm—is “outside” here someone outside of whoever is publishing your work? I’ve been edited mostly by friends and by editors publishing my work, and I pretty much always find it extremely helpful. Krupskaya’s editors, Stephanie Young, Brandon Brown, Jocelyn Saidenberg, and Kevin Killian, were amazing to work with. For instance, Stephanie helped me tremendously with some issues with capitalization and other nitty gritty things that ran throughout the manuscript and were small, but pervasive and so really important for the work. I was so glad for the help. 9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?Hmm. I'm really not sure; perhaps I have not received any good advice. Please advise me, readers! 10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?I don’t have a regular poetry writing routine, though I do usually set deadlines and other goals for myself. A typical day involves dissertation writing and research, and sometimes teaching, and sometimes poetry. 11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?Books, TV. Going to readings. Seeing art. Consuming culture, basically. 12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?I used to live in an apartment in Detroit that was too close to a garbage incinerator. I live in Brooklyn now, and NYC famously smells like hot garbage. So I’m gonna go with hot garbage. 13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?Oh yeah, totally. Certainly visual art, certainly film, certainly political theory. The most exciting thing I’ve seen recently is the exhibit America Is Hard to See at the new Whitney. It’s huge, and sort of all-encompassing and amazingly curated to let you really think through historical themes and moments. I was really into the Jeff Koons retrospective at the Whitney last year, too. 14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?Lately, David Wojnarowicz, specifically his collection of essays

Close to the Knives

. Emily Dickinson. James Baldwin. 15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?Incorporate more narrative elements into my writing. 16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?Professional athlete with a dual appointment as a socializer of feral cats. 17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?As a teenager, I was really interested in making visual art too. But writing seems to come much more naturally to me. I have a lot more control over words; I can work them into what I want, or figure out the shape of something I want to make through the process. With visual art, I don’t really have the technical skill, among other problems, so I’m always kind of flailing around and can’t get things to actually work. 18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?The last book I read is

Black Against Empire

, a history of the Black Panther Party. It’s a really carefully researched, analytically sharp book. Fiction-wise: I recently read Jacqueline Susann’s The Valley of the Dolls, Mary McCarthy’s The Group, Rona Jaffe’s The Best of Everything, and Muriel Spark’s The Girls of Slender Means in quick succession and they were amazing—I’m really interested in this midcentury female bildungsroman subgenre that I've only recently discovered. Also, Phillip K. Dick’s Do Android’s Dream of Electric Sheep?, James Baldwin’s Another Country, and Marilyn French’s The Women’s Room, which is this really great second wave feminist classic. Also, Henry Dumas’s collected short stories, Echo Tree, which I keep coming back to. Dumas was a Black Arts Movement writer who ought to be better known than he is—he wrote these amazing Black Arts magical realist stories. I moved to New York recently and so now I read fiction when I’m on the train. I’ve probably read more fiction in the last five months than in the previous five years—it’s great.Poetry-wise: Alli Warren’s Here Come the Warm Jets, Steven Zultanski’s Bribery, Anna Vitale's chapbook Unknown Pleasures. Lots of other things too, but I'll stop there. Films: I recently saw Gregg Araki’s Mysterious Skin for the first time, and it’s probably one of the best movies I’ve ever seen. I also saw Jennifer Phang’s Advantageous, which just came out and is excellent—about austerity and dystopia and set in a future that is basically now. TV-wise: I’ve been getting into

Bob’s Burgers

, which, is hilarious and also has this thing I really like where all the characters are sympathetic characters, and additionally they all get along with each other. It’s super sweet about people’s relationships to one another, basically, even though the humor of the show is pretty cynical. That sweetness reminds me of Freaks and Geeks, one of my other favorites. At some point maybe I’ll write something about the politics of this sweetness. 19 - What are you currently working on?I’m in the final stages of completing a Ph.D. right now, so I’m finishing a dissertation project about the cultural production of the Women’s Liberation and Black Power movements. The new poetry project I have going doesn’t have a title yet, but it seems to be a sort of sequel to Portrait of Doom—but starting from a place of political disappointment.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on July 16, 2015 05:31

July 15, 2015

Jane Jordan’s Books

Recently, John White, the son of the late Ottawa poet Jane Jordan (1926-2007) [see my obituary for her here] contacted us through our Chaudiere Books email address to offer us some books from her mother’s library. “I want the books to go to poets,” he told us. We said “Sure, of course, I guess,” not realizing the treasure-trove of six (so far) bins of books, journals, chapbooks, flyers and manuscripts that would end up in our living room. Sara Jane Jordan [see her Penumbra Press bio here] was known in Ottawa for many years as being one of the first to organize a reading series in the city, hosting events through Pestelozzi College on Rideau Street in the early 1970s, and her library shows an engagement with numerous writers both local and national including Ted Plantos, Juan O’Neill (who took over Jordan’s series and renamed it The Sasquatch Reading Series), Robert Craig (poet and co-editor/co-publisher of publications such as Sparks magazine and Ottawa Poetry News), Al Purdy, William Hawkins, Harry Howith, Seymour Mayne, George Johnston, Margaret Atwood, Enid Rutland, Ralph Gustafson, Milton Acorn, Patrick White and multiple other writers (and journals) I’ve not even heard of.

Recently, John White, the son of the late Ottawa poet Jane Jordan (1926-2007) [see my obituary for her here] contacted us through our Chaudiere Books email address to offer us some books from her mother’s library. “I want the books to go to poets,” he told us. We said “Sure, of course, I guess,” not realizing the treasure-trove of six (so far) bins of books, journals, chapbooks, flyers and manuscripts that would end up in our living room. Sara Jane Jordan [see her Penumbra Press bio here] was known in Ottawa for many years as being one of the first to organize a reading series in the city, hosting events through Pestelozzi College on Rideau Street in the early 1970s, and her library shows an engagement with numerous writers both local and national including Ted Plantos, Juan O’Neill (who took over Jordan’s series and renamed it The Sasquatch Reading Series), Robert Craig (poet and co-editor/co-publisher of publications such as Sparks magazine and Ottawa Poetry News), Al Purdy, William Hawkins, Harry Howith, Seymour Mayne, George Johnston, Margaret Atwood, Enid Rutland, Ralph Gustafson, Milton Acorn, Patrick White and multiple other writers (and journals) I’ve not even heard of. As the story goes, Jane White was involved with a variety of Toronto poetry circles (such as those around Poetry Toronto, a monthly poetry and listings publication that would later influence the creation of the monthly publication Bywords—which itself later morphed into bywords.ca) throughout the 1960s, divorced and moved to Ottawa just after her children moved out of the house. She didn’t see in Ottawa what she had left behind in Toronto, so she decided to organize events. She changed her name to Jane Jordan, and began organizing events. She published her poems in journals, and even produced a small handful of books.

As the story goes, Jane White was involved with a variety of Toronto poetry circles (such as those around Poetry Toronto, a monthly poetry and listings publication that would later influence the creation of the monthly publication Bywords—which itself later morphed into bywords.ca) throughout the 1960s, divorced and moved to Ottawa just after her children moved out of the house. She didn’t see in Ottawa what she had left behind in Toronto, so she decided to organize events. She changed her name to Jane Jordan, and began organizing events. She published her poems in journals, and even produced a small handful of books.Scattered across six bins, there are copies of WORDFEST, a publication produced as part of an annual poetry festival held at SAW Gallery: the first was held on August 6 and 7, 1982, and the second, August 12-14, 1983. To get a sense of activity, the 1982 chapbook includes work by Cyril Dabydeen, Mark Frutkin, Alice Groves St. Jacques, Blaine Marchand, George Miller, Riley Tench, Lorna Uher (who became Crozier) and Patrick White. The second annual includes work by Richard Truhlar, Steven Smith, Colin Morton, steve mccaffery, Robert Hogg, Michael Dean and Catherine Ahearn.

There are copies of short-lived journals I’ve never heard of, including Ottawa Poetry News, Review Ottawa and Reenbou: revue plurilingue de poésie / plurilingual poetry magazine (1979), as well as some I’d heard of but never actually seen, including the infamous Sparks (1976-77) and the three issues of Stephen Brockwell’s The Rideau Review(1987-8), and even publications I haven’t thought about in years, such as Hook and Ladder (1994). There are notebooks, journals and unpublished manuscripts by Jane Jordan that I haven’t even begun to open yet. There are dozens of poetry books (including signed and/or hardcovers) by Margaret Atwood, Eli Mandel, Seymour Mayne, Leonard Cohen, Diana Brebner, Al Purdy and many, many others, all of which include a lingering smell of stale cigarette smoke.

There are copies of short-lived journals I’ve never heard of, including Ottawa Poetry News, Review Ottawa and Reenbou: revue plurilingue de poésie / plurilingual poetry magazine (1979), as well as some I’d heard of but never actually seen, including the infamous Sparks (1976-77) and the three issues of Stephen Brockwell’s The Rideau Review(1987-8), and even publications I haven’t thought about in years, such as Hook and Ladder (1994). There are notebooks, journals and unpublished manuscripts by Jane Jordan that I haven’t even begun to open yet. There are dozens of poetry books (including signed and/or hardcovers) by Margaret Atwood, Eli Mandel, Seymour Mayne, Leonard Cohen, Diana Brebner, Al Purdy and many, many others, all of which include a lingering smell of stale cigarette smoke.What these bins really offer is the opportunity to begin crafting a portrait of poetry in the capital throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s, a period that hasn’t been documented anywhere that I’ve been able to find. Once I began to move deeper through the material, I’m hoping to start crafting individual blog posts to highlight some of these lost titles and lost histories. I’ve already started talking to Steve Artelle and Cameron Anstee about the best way to track and acknowledge some of these histories and publications, and even begun sending out a variety of emails to those Ottawa poets who might be able to help answer some questions on individual writers, titles or journals, as well as the period generally (if you were around for any of this, shoot me an email: we should talk).

Also: once some of the material is properly sorted and organized, I’ll be working to get books out into the hands of local poets (have already handed out a small amount of books during the last session of my poetry workshops). Perhaps a small gathering in our house over drinks.

Just going through the bulk of the titles included in these bins, I wouldn’t see much overlap by way of interest between she and I, such as works by Plantos, Gustafson, Mayne or White, for example. Her attention focused on a poetry built of plainer speech, attempting occasionally to break out of the lyric, but not often. And yet, the books quickly present a portrait of a writer deeply engaged with poetry and a community of writers, one she helped encourage and foster, back in the days when Ottawa literature had very few champions.

Just going through the bulk of the titles included in these bins, I wouldn’t see much overlap by way of interest between she and I, such as works by Plantos, Gustafson, Mayne or White, for example. Her attention focused on a poetry built of plainer speech, attempting occasionally to break out of the lyric, but not often. And yet, the books quickly present a portrait of a writer deeply engaged with poetry and a community of writers, one she helped encourage and foster, back in the days when Ottawa literature had very few champions.Imagine: The TREE Reading Series was still a decade away, and Arc Poetry Magazine had yet to emerge from Carleton University. William Hawkins had left his heady 1960s days hosting poets and musicians at Le Hibou for the security of driving a cab for Blue Line. What else was there?

One thing I do find curious, and slightly frustrating, is a lack of names from Ottawa’s 1980s, during a period that included an influx of poets from Peterborough—Michael Dennis, Dennis Tourbin, Riley Tench, Ward Maxwell and Luba Szkambara, for example (active in that period contemporary and slightly prior to the emergence of Ottawa poets Colin Morton, Nadine McInnis, Stephen Brockwell, Sandra Nichols, Susan McMaster, John Barton, Holly Kritch and others)—all of whom I’d be interested in knowing more about, as far as their particular activities and publications. Were these writers she simply didn’t encounter, engaged in their own events around the city? Are there simply more bins to come?

Published on July 15, 2015 05:31

July 14, 2015

jwcurry's Room 302 Books offers its first e-list

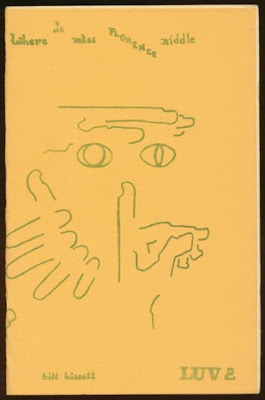

jwcurry's Room 302 Books offers its first e-list of small press rarities, including works by 1. AYLWARD (David), BALL (Nelson), CRAVAN (Arthur), FOUR HORSEMEN (Rafael Barreto-Rivera, Paul Dutton, Steve McCaffery, bpNichol), GARNER (Don), HOUÉDARD (Dom Sylvester), KABIN (Marje), LABA (Mark), NICHOL (bp), ONDAATJE (Michael), POWER (Nicholas), SWEDE (George), UU (David), VALOCH (Jiri), ZAPPA (Frank), ALLAND (Sandra), BOOKS (Jennifer), DURR (Pat), FUJINO (David), GILBERT (Gerry), KILODNEY (Crad), LEFLER (Peggy), ROSS (Stuart), TRUHLAR (Richard), ZACHARIN (Noah), BALL (Nelson), COLEMAN (Victor), DEDORA (Brian), EVASON (Greg), FARRANT (M.A.C), HOOD (Wharton), JEWINSKI (Hans), SPARLING (Ken), ZELLER (Ludwig), AGUIAR (Fernando), BISSETT (Bill), CURRY (jw), DEAN (Michael), IRWIN (Marilyn), JOHNSTON (Brain David), LABA (Mark), MORIN (Gustave), NICHOL (bp), ORD (Douglas), PHILLIPS (David), RIDDELL (John), SHANGER (Gio) K, TALLMAN (Warren), MORIN (Gustave) B and WADE (Seth).

jwcurry's Room 302 Books offers its first e-list of small press rarities, including works by 1. AYLWARD (David), BALL (Nelson), CRAVAN (Arthur), FOUR HORSEMEN (Rafael Barreto-Rivera, Paul Dutton, Steve McCaffery, bpNichol), GARNER (Don), HOUÉDARD (Dom Sylvester), KABIN (Marje), LABA (Mark), NICHOL (bp), ONDAATJE (Michael), POWER (Nicholas), SWEDE (George), UU (David), VALOCH (Jiri), ZAPPA (Frank), ALLAND (Sandra), BOOKS (Jennifer), DURR (Pat), FUJINO (David), GILBERT (Gerry), KILODNEY (Crad), LEFLER (Peggy), ROSS (Stuart), TRUHLAR (Richard), ZACHARIN (Noah), BALL (Nelson), COLEMAN (Victor), DEDORA (Brian), EVASON (Greg), FARRANT (M.A.C), HOOD (Wharton), JEWINSKI (Hans), SPARLING (Ken), ZELLER (Ludwig), AGUIAR (Fernando), BISSETT (Bill), CURRY (jw), DEAN (Michael), IRWIN (Marilyn), JOHNSTON (Brain David), LABA (Mark), MORIN (Gustave), NICHOL (bp), ORD (Douglas), PHILLIPS (David), RIDDELL (John), SHANGER (Gio) K, TALLMAN (Warren), MORIN (Gustave) B and WADE (Seth).For a copy of the price list, email jwcurry directly at jwc3o2 [at] yahoo.com.

You can see previous of his lists here and here, as well as my piece on his archive posted earlier this year at Jacket2.

As he writes:

online picture-list #1 : some standards

this list's a first tester toward putting up a series of online lists through Flickr. since Flickr's not really supposed to be used for blatant advertising, prices must be left off, which is where this document with its accompanying links comes in. if y'r happy with a print list, here it is. if you want illustrations of the fronts of each of these titles (along with all the list text accompanying each image), they can be found at https://www.flickr.com/photos/48593922@N04/collections/72157654809545832

as per usual, orders should be directed to jwcurry & payment sent to our new address at #3o2 – 28 Ladouceur Avenue, Ottawa Canada K1Y 2T1. orders by regular mail accompanied by payment will not suffer a post & packing fee; all other orders will be dinged extra.

hours at the store, though it's still in serious disarray, can accommodate anytime visits; just be sure to call ahead (613 798 2522) to make sure i'm in & up.

Published on July 14, 2015 05:31

July 13, 2015

Mary Hickman, This is the homeland

Rub it all over the forearms whitepush then red.Sandalwood explains the crane nested in the mountain.Her wild hips, jagged beak.

Body lumps & chest-hole. What land is this? (“Territory”)

I’m quite taken with the precision of the poems that make up Iowa City poet Mary Hickman’s first trade collection, This is the homeland (Boise ID: Ahsahta Press, 2015), a book that “consists of eight poetic sequences written over a ten-year period, begun when she worked as a surgical assistant in open-heart surgeries.” As she writes in the poem “Territory”: “This is the way to the steel table. / This is the homeland.” The press release informs us that:

The homeland of the title sequence is the body, open upon the steel surgical table; the sequences are linked by an attention to the visceral elements of language and by an exploration of the themes of health, transformation, desire, and identity. Hickman charts the precarious and ecstatic response of consciousness surrendering itself to language and experience, a vertigo in which the self is called back to itself and the world through losing itself. These poems are as much about love as loss, therefore—elegies to times, places, and people whose presences sear and haunt the poems.

Part of what intrigues about the collection is in the way that the “eight sequences” aren’t set side by side but occasionally weave through and between each other, creating very much a cohesive unit over an assemblage of sequences composed over such an extended period. “My desire immense / domestic, she says.,” she writes, in the poem “The Locust II.” Her poems are scalpel-sharp, insightful, bone-dense, attentive, unapologetically heartfelt, and savagely beautiful. As she writes in the poem “Remembering Animals,” a poem composed after the death of her brother-in-law: “I’d like to think / I could solve the problems of / love lives, libraries, wildlife, / obfuscating / griefs.” Given her professional experiences, one can easily read the meditative aspects of the body throughout, writing a series of questions of the physical body and how it relates to living, identity and death, stretching an intricate and intimate range of concerns relating to, and even separate from, that same body. If Robert Kroetsch once asked, “How do you grow a poet?,” Hickman’s poems, in their own way, might actually be showing exactly how at least one poet came to be, emerged through this first remarkable collection of poems on grief, live and love. Hickman is writing the most intimate of our concerns through poems that expand outward toward all else, writing out basic, human lines of questioning in an entirely original cadence.

Part of what intrigues about the collection is in the way that the “eight sequences” aren’t set side by side but occasionally weave through and between each other, creating very much a cohesive unit over an assemblage of sequences composed over such an extended period. “My desire immense / domestic, she says.,” she writes, in the poem “The Locust II.” Her poems are scalpel-sharp, insightful, bone-dense, attentive, unapologetically heartfelt, and savagely beautiful. As she writes in the poem “Remembering Animals,” a poem composed after the death of her brother-in-law: “I’d like to think / I could solve the problems of / love lives, libraries, wildlife, / obfuscating / griefs.” Given her professional experiences, one can easily read the meditative aspects of the body throughout, writing a series of questions of the physical body and how it relates to living, identity and death, stretching an intricate and intimate range of concerns relating to, and even separate from, that same body. If Robert Kroetsch once asked, “How do you grow a poet?,” Hickman’s poems, in their own way, might actually be showing exactly how at least one poet came to be, emerged through this first remarkable collection of poems on grief, live and love. Hickman is writing the most intimate of our concerns through poems that expand outward toward all else, writing out basic, human lines of questioning in an entirely original cadence.I don’t want my name. He has hidden his own fair name in a clown, in the dark corners of my crown my feet my handkerchief. Your name is strange: Lapwing. You flew, Seabedabbled lapwing, because you know.

I am anticipating what you have to say. I am asking too much, tired of my voice. Lapwing. The voice that makes love to the seacoast. Or his last written words.

You are a delusion. You, brought all this way, do you believe?

Write! Visit! Help me believe. I called on the birds. This will end. I shall be there, laughing into a shattering daylight.

And scribble nightly, unwed. (“Joseph & Mary”)

Published on July 13, 2015 05:31

July 12, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Sandra Simonds

Sandra Simonds is the author of four books of poetry including

The Sonnets

(Bloof Books, 2014),

Mother Was a Tragic Girl

(Cleveland State University Press, 2012) and the forthcoming

Steal It Back

(Saturnalia, 2015). Her poems have been anthologized in the Best American Poetry 2014 and 2015. She lives in Tallahassee, Florida. Follow her on Twitter at @sandmansimonds

Sandra Simonds is the author of four books of poetry including

The Sonnets

(Bloof Books, 2014),

Mother Was a Tragic Girl

(Cleveland State University Press, 2012) and the forthcoming

Steal It Back

(Saturnalia, 2015). Her poems have been anthologized in the Best American Poetry 2014 and 2015. She lives in Tallahassee, Florida. Follow her on Twitter at @sandmansimonds 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Pretty much my first book did nothing for me. I was broke as fuck then and I’m broke as fuck now. My recent work is somewhat more narrative and sadder because life gets harder, more complicated and sadder as it goes on!

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

For me poetry follows the logic of music and the logic of the body. I think you have to follow your ear in order for a poem to work—you know the hidden story that can only be told through blind faith in the sound. I’m a really bad fiction writer, so I can’t speak to that. I have only published one story in my whole life. I do write nonfiction and I think there’s more of an affinity between nonfiction and poetry—many people have noticed this strange overlap. I actually love nonfiction.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I write very quickly and manically when I’m in a writing mode. No notes or anything like that. I write the beginning of the poem to the end, usually in one draft and then revise it when my head is in boring “logical mode.” If a line comes into my head, say if I’m at Walmart or something, I sometimes will use it in a poem later but my test is if I don’t remember it, it didn’t happen so who cares. I’m generally against coddling language and hanging on to bits and pieces like they are diamonds or something—guess I just don’t work that way but I know a lot of great poets who do. Everybody’s different. I can’t afford to write like that because most of my energy is poured into just trying to survive on this sad planet of ours.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I have no idea. Language just pops into my head and then I sit down and write a poem. I have no idea where my poems come from. I guess I just make them up or maybe I’m an alien or witch.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Readings are like acting to me and I can pretend to be someone else who isn’t me who is me. It’s kind of fun and I like meeting new people. Plus, I love fashion so readings are a great excuse to try out cool clothes and wear them in public. Sometimes I enjoy readings. Being very drunk helps though I don’t do that anymore.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I tend to focus on strategies to destroy patriarchy and capitalism in my poems but I really can’t say that I’m answering any questions and even if all my strategies failed, I feel like I tried, so there’s that.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

As a woman, as a single mom, to try to be a public intellectual and engage in the political even though it’s difficult and we are all fighting all of the time and there’s a lack of support.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Yes because I’m not that meticulous and I make a lot of mistakes with my writing. I need an editor.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

As a writer? Don’t listen to what anyone tells you to do and go on your nerve (O’Hara)

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to creative non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

I like to write critically about poetry and I like creative nonfiction. I would write a memoir but I don’t really want anyone to know anything about my life, so I guess you could say there’s a conflict of interest.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

When I’m teaching I get up at 6, make my two kids breakfast, drive them to school, then drive to Georgia from Florida where I teach (45 minute commute), then I teach all day and go to meetings and then I come back to Florida and then I pick up my kids from school, then I bring them home, make them dinner then I give them a bath, read them books and sing them songs and then I put them to bed. When this whole thing is over it is usually about 9pm and then I sometimes write for a few hours but often I just pass out because I’m exhausted and complaining about the ills and terrors of capitalist labor and how it gives me no time to think, read, write or love.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I don’t have anxiety about this at all. When I’m not writing, I accept it and have complete faith that I will write again. When I was younger, I had anxiety about this, but my experience tells me that it’s not something I should worry about.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Opium

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Just really living, being a human, fucking up, making mistakes, celebrating the small triumphs (both my own and the triumphs of the people that I love) so for lack of a better phrase “keeping it real.” I want my work to speak to real people with real problems and struggles and in order to do that, I feel like it’s important to stay in the trenches, in some sense. It’s about fidelity, understanding, sympathy. I go to Walmart. My kids are in public school. I struggle. I want my life to be relatable so that my work always will be.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

There are too many to name. People who immediately come to mind are poets the Anne Boyer, Joshua Clover, Chris Nealon, Dana Ward, Cathy Hong, David Lau but the list just goes on and on. I love, respect and admire the work of my peers.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I really want to go to Nepal.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I think I would have been a good pediatrician.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Because it’s the only thing I’ve ever done that has repeatedly saved my life!

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I just read three books that I thought were fantastic: The Compleat Purge by Trisha Low, Mr. West by Sarah Blake, Women In Public by Elaine Kahn and Dear Alain by Katy Bohinc. I enjoy the way that all of these books think through women’s lives in 21st century capitalist society in ways that are both complex and moving.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Long poem called Orlando about a few recent life fantasies and disasters.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on July 12, 2015 05:31

July 11, 2015

12 or 20 (small press) questions with Kent MacCarter on Cordite Books

Kent MacCarter

(Managing Editor, Site Design, Short Reviews Editor) is a writer and editor in Castlemaine, with his wife and son. He holds a BA in Accounting from the University of Montana, a BA in Finance from the University of Montana, and an MA in English with focus on Creative Writing from University of Melbourne. His publishing career began at University of Chicago Press in 2000, and since he has work with educational publishers Cengage Learning and Curriculum Press in Australia. He’s the author of three poetry collections – In the Hungry Middle of Here (Transit Lounge, 2009), Ribosome Spreadsheet (Picaro Press, 2011) and Sputnik’s Cousin (Transit Lounge, 2014). He is also editor of Joyful Strains: Making Australia Home (Affirm Press, 2013), a non-fiction collection of diasporic memoir. He is an active member in Melbourne PEN, and was executive treasurer on the board for Small Press Network from 2009-2013. In 2012 he received a Fulbright Travel Award to attend writing festivals and lecture at Indonesian universities.

Kent MacCarter

(Managing Editor, Site Design, Short Reviews Editor) is a writer and editor in Castlemaine, with his wife and son. He holds a BA in Accounting from the University of Montana, a BA in Finance from the University of Montana, and an MA in English with focus on Creative Writing from University of Melbourne. His publishing career began at University of Chicago Press in 2000, and since he has work with educational publishers Cengage Learning and Curriculum Press in Australia. He’s the author of three poetry collections – In the Hungry Middle of Here (Transit Lounge, 2009), Ribosome Spreadsheet (Picaro Press, 2011) and Sputnik’s Cousin (Transit Lounge, 2014). He is also editor of Joyful Strains: Making Australia Home (Affirm Press, 2013), a non-fiction collection of diasporic memoir. He is an active member in Melbourne PEN, and was executive treasurer on the board for Small Press Network from 2009-2013. In 2012 he received a Fulbright Travel Award to attend writing festivals and lecture at Indonesian universities.1 – When did Cordite Books first start? How have your original goals as a publisher shifted since you started, if at all? And what have you learned through the process?Cordite Books began quite recently, November 2014 to be exact. But Cordite Press Inc., the non-profit that publishes Cordite Poetry Review, was founded in 1997 by Australian poets Peter Minter and Adrian Wiggins. The first five issues of Cordite Poetry Review were newsprint broadsheets, then it went online-only just a few months after Jacket began. Interestingly, it was these two poetry publications that pioneered the space for Australian literature (of any kind) online, before many other publications that have come and gone, and even before a number of Australian newspapers, too.

Alan Loney’s new collection, Crankhandle, is what pushed me over the edge to do print books. I’d been hounding Loney to run some of his work for years – online – and he’d steadfastly refused, finding the treatment and ultimate display of his poetry online in Jacket (years earlier) so poor and traumatising for him that he vowed never to do it again. And he hasn’t, and still won’t. Loney chiefly does short-run art books with various small presses around the world, which most readers cannot afford. Beautiful things. I’m not sure how he came to be in Australia initially, but he’s been here and, sadly, largely ignored for at least a decade, and has forsaken, or been forsaken by, his native New Zealand (for rumour and conjecture that I’m not going to wade into). Anyhow, your English-language poetry collection is incomplete without Crankhandle, no matter where you are on Earth. Which gets me back to when Cordite Books started; pretty much as soon as I had my e-hands on the manuscript he emailed me. I had to do it in an accessible way, and online wasn’t an option. Ross Gibson, John Hawke and Natalie Harkin followed. I spent way more than I could have on cover design and high-quality paper stock – Zoë Sadokierski’s series design is absolutely worth it – yet this expense was offset by printing four books at once. It’s worth it to make non-POD books with paper that won’t fox by your next birthday. And I am unbelievably fortunate to start with these four authors.

2 – What first brought you to publishing?My publishing career began, such as it’s been, wending its circuitous way around the constraints of geography I have foisted upon it, at University of Chicago Press. I certainly wasn’t working on their storied poetry list at the time, however. There, it was my duty to cajole university libraries around the world to renew subscriptions to Critical Inquiry, as well as a litany of other journals. One of those journals had a circulation under 40. Really, some were easier to shill than others. I started in January 2000: the world had remained after Y2K, replete with hibachi and bottled-water caches, and jobs still required extant warm bodies to perform them. Journals were just moving online, then, and most of the fusty editors were terrified of this migration. I spent fours years there.

It soon dawned on me how foolish it’d be to not ‘take advantage’ of the spoils on offer at UC. No matter how hoity-toity that university’s policy was to not offer degrees in creative arts, and it was, asphyxiatingly so, it did stock some excellent minds to lurk its waters: Robert van Hallberg, Mark Strand, etc. Initially, I was too naive to be intimidated by them, which I quickly grew out of! I was enormously lucky to be accepted into one of Thom Gunn’s last ever poetry workshops. And so began the tide of language to return fire, carve a niche and then completely usurp the financial accounting and commerce degrees I got from University of Montana in 1996.But what first brought me to publishing? I was living in a baby blue Ford Tempo, jobless and listless, when an enterprising old friend of mine from Grade 1 (true!) managed to finagle me into a junior role at the Press. I needed a job. And a room with heat.

3 – What do you consider the role and responsibilities, if any, of small publishing?My goals as a publisher of poetry and publisher of critical poetry book reviews, and now books, are still being honed, but you can glean from these links an insight into my editorial mandate.

4 – What do you see your press doing that no one else is?I could say that we’re interested in putting out exquisite-looking objects written by poets heretofore ignored or from those who’ve gone silent for years or new voices worth a read. And that’s all true. But many presses do that. The admittedly rather bonkers publishing model of Cordite Poetry Review – relying on a new guest editor every four months to deliver the backbone of our raison d’être (!!) – means that while what and who we publish is amazingly diverse, there are many cases where a poem is published that I wouldn’t have selected. Too, this means a lot of excellent work is not taken for publication. And that’s okay. It’s what we’re known for now, although the old guard seems totally incapable of understanding why we do that. So doing books is, quite selfishly, a way for me to get work I feel especially important out into the world. Expect to see books from Amanda Stewart, Berni M Janssen, Claire Nashar and Tony Birch in the near-ish future.

We’re also big on the transmedia overlap of comics and poetry, which we’ve championed for a while. There are some active pockets of this in the States, but we’ve been right there as well, though in Australia, so few people have actually noticed. Our special issue ‘PUMPKIN’ was great fun to produce, and the first of its kind anywhere. A pity the print publisher that wanted to do an expanded version lost the plot. Maybe we’ll do it one day. But we do have some Mandy Ord–Anna Krien and Bruce Mutard–Amanda Johnson collaborations in the works.

5 – What do you see as the most effective way to get new books and chapbooks out into the world?

Chapbooks? Well, if you can manage it, print off 100 copies and give them away to anybody who wants one. But that’s easier waxed-lyrical than done. Since I am fortunate enough to have/am saddled with a pragmatic day job that has nothing whatsoever to do with poetry or my writing but does earn me a middle-class wage, I have been fortunate enough to do just as I’ve espoused. I gave a rudimentary guest lecture on O’Hara at Hasanuddin University in Indonesia – given I neither speak Bahasa Indonesia nor am an O’Hara scholar – and the best part was being able to dole out 50 copies of my Ribosome Spreadsheet to all the eager students who voluntarily showed up. That’s worth gobs more than, say, the ten bucks (or less) I might’ve made in trying to sell them. Most knew of O’Hara because of Mad Men.

But what about thicker, slightly ‘chappier’ books, such as the four I have just published? I have deliberately kept them trim, but long enough to be considered full-length collections in the eyes of peers and funding bodies. Somebody else can do the mighty tomes, not us. I talked to a few book distributors in Australia about carrying them. But, frankly, I already have the most captive market there’s going to be for a poetry book to make a sale within Australia, and a goodly ways outside our border, too. Some small Australian presses like Hunter Publishers and Sleepers Publishing have both the quality books and the connections to piggyback their smaller lists onto the chuckwagon of larger publishers’ distribution deal with Macmillan or Penguin. I would do that if I was given the opportunity but, again, I’m not sure Cordite Books needs to do that. Obviously, the print runs are minuscule compared to novels and non-fiction. And the books are not POD; they’ve been done in limited print runs.

For Cordite Books, the most effective way to get exposure for a book is to offer it up as an optionfor contributor payment. So, we have. Unfortunately, we’re still only able to pay Australian citizens or permanent residents, but we’ve tenaciously made sure we’ve been able to do that for a dozen years now. (We’re otherwise completely independent with no university lifeline or philanthropy. Yet.) But the majority of writers we publish are eligible for payment, so they can chose: full payment in cash for a poem, a combo of cash and books or just books. Up to them. No pressure. Free postage within Australia. This is brand-new for us, and while I am not naive enough to think that most contributors will opt for this, some definitely have. The point is, this model places the books front and centre to the most receptive audience possible, between four and six times a year. Constantly. No distribution company will ever be able to deliver that. And as a distribution channel it costs us nothing … save the 18 years of journal issue publishing we’ve already done. Of course, Cordite Books also has an online shop.

A journal’s circulation, be it in print or online, is calculated by a significant input of codswallop and fuzzy math. But funding bodies such as those partners Cordite Press Inc. (the parent non-profit company) has worked so hard to cultivate dolike to see some numbers, and I can’t blame them. So, in their metrics, Cordite Poetry Review has a circulation of about 250,000 per year. More specifically, that number represents unique IP accesses per year. The location of our readers is: 56 per cent from Australia, 15 per cent from the USA, 5 per cent from the UK, 4 per cent from the Philippines, 3 per cent from Canada, 2 per cent each from India and New Zealand, and 1 per cent each from Germany, South Korea, Ireland, Indonesia, France and Singapore. Seventy-seven nations had 50 or more unique sessions per year that do not trip the bounce rate. It’s highly imperfect measuring, but it’s an indication of readership and subsequent exposure for the books.

So, I am comfortable that we’ll be able to get the books out to whoever may want them. I’m still pursuing getting tangible copies into the States, Canada and the UK, though. Any tips or nepotistic overtures in so doing are welcome. Also, I can highly recommend this article, ‘On Novelists and Poets,’ by Ivor Indyk, director of Giramondo Press in Sydney, which delves into the unique economy of poetry publishing worldwide.

6 – How involved an editor are you? Do you dig deep into line edits, or do you prefer more of a light touch?

Much more often than not, pretty light on from me regarding poems. Depends on the guest editor, though, for specific issues. At times we do take a poem on the condition of an edit or two, but that’s not too common. I was more involved with edits of the first four books, but even then, not deeply. Having typeset all the books myself, I can say that far more time went into getting the poems to look right and balance on the spreads. Natalie Harkin’s book took weeks to get right in that regard, and when you’re shoehorning a text done originally in Word into an InDesign space nowhere near the dimensions, well, that’s quite challenging. So form and appearance editing is as, or more, important to me. Mind you, I have been awfully choosy in going with the manuscripts I have, and that will remain. Frankly, Australian poetics is so fecund right now with exciting new writers (and, very much so, a number of poets always overlooked and still writing) that you can see it practically seep honey and blood all over the zeitgeist of our national letters (not to be confused with the narrower-defined bounty deemed ‘commercially viable’ and of the ilk of ‘what people want’). I can afford to be enormously choosy right now, so the deep-slicing edits aren’t needed. The basics, of course, are all part of the deal/fun.

As for reviews, essays, interviews and all the rest, the edits can be as deep as they need to be without an outright rejection of the work. Were we to have more resources, I’d be stricter still.

7 – How do your books get distributed? What are your usual print runs?

I think I’ve covered this one already. Print runs are small. It’s poetry: worth doing, and can be done without losing money. But we’re not doing these books with a commercial imperative.

8 – How many other people are involved with editing or production? Do you work with other editors, and if so, how effective do you find it? What are the benefits, drawbacks?

We have an excellent Feature Reviews Editor in Bonny Cassidy, Scholarly Editor in Matthew Hall, Site Producer and Digital Editor in Benjamin Laird, Audio Producer in Ella O’Keefe and copy editors in Zenobia Frost and Penelope Goodes. Superlative minds, all. But, in terms of production, I am everything from ‘janitor’ to Managing Editor to CEO to grant writer to coder to bookkeeper to you name it. Most people assume we have a street address and an office with some staff and some computers and, you know, operate like an ‘actual’ not-for-profit small business. We need to. We are that. There is absolutely enough to do. We’re working on rectifying that. Before the print runs of our first four books in 2015, the only permanent asset that Cordite Press Inc. had owned since 1997 was the spring-loaded address stamper that inks our PO box address on mailers we use to send out review copies and, now, sold books. The rest? It’s ephemeral, loaned or donated.

9 – How has being an editor/publisher changed the way you think about your own writing?

We get between 5000–6000 poems submitted to us per year. We do about 50 reviews annually. And, everything else. Reading and assessing other writers’ work is an extremely effective way to discover problems in your own. I spot trends, and am afforded the at times perilous spot on the tip of the diving board where I can compare that which is really happening for me at a given time to what other writers are producing. More often than not, though, who cares? This far in to writing poetry, I’ve stopped trying to sculpt my own work to fit what I thinkothers might like.

10 – How do you approach the idea of publishing your own writing? Some, such as Gary Geddes when he still ran Cormorant, refused such, yet various Coach House Press editors had titles during their tenures as editors for the press, including Victor Coleman and bpNichol. What do you think of the arguments for or against, or do you see the whole question as irrelevant?

For me, just about never. In my time as Managing Editor, I’ve had one poem taken by a guest editor, Duncan Hose, who indeed read it blind and selected it as per. I tossed a poem into the UMAMI-themed submissions recently, and Luke Davies selected it anonymously. That’ll make two poems in five years. Plenty. We’ve run some poems from editors on the masthead, and I have made it perfectly clear that’s fine by me. But we won’t be publishing my next book nor any of the masthead’s next books either. Cordite Poetry Review has a long history, though, and there are clearly points earlier in the aughts where some generous takes occurred. I have no tirade against doing so; it’s just not for me.

11– How do you see Cordite Books evolving?

We’re in, or, more apt, hoping to be in soon, a major transition for Cordite Press Inc. (Books and the journal). Having an actual, paid part-time staff member, some self-generated income and some long-term funding would see Cordite become a permanent fixture in Australia literature (though recent government funding shenanigans will likely derail this, more on this further on). True, we’ve managed to stick around for 19 years now, but in every MacGyver way possible. I’m not sure that’s tenable for much longer. We’ve been giving away the journal for free nearly the whole time. And I aim to keep it that way. As we all know from anywhere on Earth, arts funding is a cutthroat racket. So staying alive is the first order; evolving would be excellent. In nematode stage at the moment – get back to me when we’re a bivalve of some sort.

12– What, as a publisher, are you most proud of accomplishing? What do you think people have overlooked about your publications? What is your biggest frustration?

As a print book publisher, we’re just starting out. It took five months from the germination of the idea of printing books to having four of them available, and I am proud of that. Typesetting in InDesign is a perpendicular experience to tagging poems with HTML. Each has its nuances and constraints, but all up, it’s easier to do in print. It’s been fun. I’m not sure we’ve been around long enough to be noticed much at all, let alone overlooked! Yet.

As for greatest frustration(s)?

The macro answer is: being fettered to the vagaries and political kniving that directly affect our funding. For our first 18 years of publishing, we had only one source of funding: the Australia Council for the Arts, a benevolent but not problem-free organisation that distributes public monies to the arts. The current bonkers right-wing government here has recently halved the Council’s budget, diverting that huge chunk of cash into an unnecessary new parallel government centre of arts ‘excellence’ so that it can further support the already well-funded machinery behind Australian opera, symphony and theatre, politicos’ chums and/or perceived pillars of said ‘excellence’. It’s a massive boondoggle that rorts public arts funding in just about every way. Since my time at Cordite Press Inc., I’ve diversified our funding. Now, we’re selling books.

The micro answer is: writers using the false constraints of Microsoft Word to arbitrarily centre whole poems (just because they can do it in three keystrokes) or using its tab function to create indents. Word’s tabs are untranslatable in HTML. If you submit poems to an online journal, please consider using hard spaces for floating lines.

13 – Who were your early publishing models when starting out?

Book-wise, I’ve always been a fan of Shearsman in Bristol, its books and journal combo, and the nature of what it publishes. Too, Salmon Poetry in County Clare; Graywolf Press in Minneapolis; Les Figues in Los Angeles; Titus Books in Auckland; BookThug in Toronto; Rabbit Poetry in Melbourne and Vagabond Press in Tokyo, run by Australian poet Michael Brennan. All going concerns that have managed to find a way to keep on. Call me a bourgeois twit, but I applaud when university presses still bother with poetry. In Australia, that’s UQP and UWAP. Truth is, I am making this caper up as I stumble along. Pass the refried beans, please.

14 – How does Cordite Books work to engage with your immediate literary community, and community at large? What journals or presses do you see Cordite Books in dialogue with? How important do you see those dialogues, those conversations?

There is a near-fetishisation (by funding bodies, writers’ festivals, etc) of the ‘new’ and ‘emerging’ and ‘young’; all appellations which deserve a gearing for coverage and attention (though it’s rather lopsided towards those bents at the moment). Cordite has some books coming up by poets that are thus: Autumn Royal, Claire Nashar, Siobhan Hodge. But we’re also interested in publishing new collections by writers who’ve been at it for a long time and toil in ‘woefully under-read’ eddies for years: Javant Biarujia, Berni M Janssen, Amanda Stewart.

The past decade has seen a significant changing of the guard in who holds the keys to Australia’s literary journals, which is an excellent development. Yes, the small scrum of editors that I am a part of are still ‘gatekeepers’ (as soon as you put out even the most DIY of zines, you assume a role of gatekeeper), and you have pockets of writers who will bellyache about that to their last breath, but at least some of those people are now women, openly gay or lesbian with a positive agenda to match, non-Anglo and many now under 50 years of age. Of course, the Internet has helped that significantly: foem:e , Tincture Journal , Verita La , Mascara Literary Review , Peril Magazine , Plumwood Mountain are all worth reading.

There is an upcoming double issue we’re doing with Melbourne’s The Lifted Brow , and, as mentioned, we recently did something similar with Arc Poetry Magazine in Ottawa. We did a fully bilingual issue(English and Bahasa Indonesia) with the Lontar Foundation in Jakarta and a similar bilingual project in English and Korean with the Sidney Myer Asialink Foundation, again here in Melbourne. We’ve got a bilingual Australian poetry sample in the works with Lichtungen in Graz, and are just about to launch a major bi-national issue with a heavy focus on New Zealand poetry and its literary goings-on. I think the e-chapbook on contemporary Scottish poetry we did with Robyn Marsack of the Scottish Poetry Library was great.

15 – Do you hold regular or occasional readings or launches? How important do you see public readings and other events?