Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 373

August 7, 2015

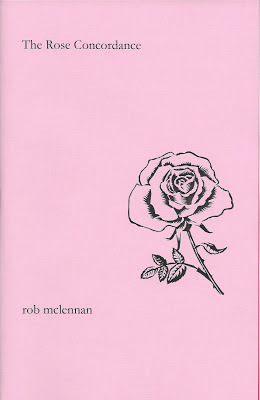

a new chapbook (and how to order) + The Sawdust Reading Series (reminder,

In case you've forgotten, I'm featuring at The Sawdust Reading Series on Wednesday, August 19, 2015 at 7pm (see the link here for further information). I've produced a wee chapbook through Apostrophe Press as a handout for such, but if you wish for a copy (while supplies last) and can't make the event, paypal me $4 via the donate button on the sidebar, and I'll mail you a copy. That work?

In case you've forgotten, I'm featuring at The Sawdust Reading Series on Wednesday, August 19, 2015 at 7pm (see the link here for further information). I've produced a wee chapbook through Apostrophe Press as a handout for such, but if you wish for a copy (while supplies last) and can't make the event, paypal me $4 via the donate button on the sidebar, and I'll mail you a copy. That work?

Published on August 07, 2015 05:31

August 6, 2015

(another) weekend in old glengarry (+ the glengarry highland games,

We spent the weekend in Old Glengarry again, for the sake of the 68th edition of the Glengarry Highland Games on Saturday, and my sister's fifteenth annual afternoon pot-luck on Sunday [see last year's entry here; the previous year's entry here].

We spent the weekend in Old Glengarry again, for the sake of the 68th edition of the Glengarry Highland Games on Saturday, and my sister's fifteenth annual afternoon pot-luck on Sunday [see last year's entry here; the previous year's entry here].Saturday, August 1, 2015: Kate, Christine, Rose and I left Ottawa first(ish) thing in the morning, and arrived just in time to participate in the Clan parade, alongside my sister and her three children, which bulked up the representatives behind our banner (which the other participants were quite pleased for). Unfortunately, they mis-announced our Clan name ("McLellan"), which annoyed, but they were quickly corrected. I mean, weren't we carrying a big damned banner ahead of us as we walked?

I didn't realize we have a "new" plaque; given we hadn't a Clan Chief for some three hundred and fifty years until 1976, a new one was produced around that time. Apparently we have the old one, with three heart nails. I took a picture of the new one, just to know what it looks like (I prefer the old one).

I didn't realize we have a "new" plaque; given we hadn't a Clan Chief for some three hundred and fifty years until 1976, a new one was produced around that time. Apparently we have the old one, with three heart nails. I took a picture of the new one, just to know what it looks like (I prefer the old one).My sister, Kathy, was there for the sake of her middle child, Rory, dancing as part of the morning's festivities. We sat in the heat and took many photos. Oh, what a warm day to be wearing such outfits.

We spent the day wandering, to see what and who we could see. Neither Christine, Kathy nor Kate could get their cellphones to work, which made us wonder why the Highland Games (incidentally, said to be the largest highland games outside of Scotland) even bothered having a hashtag. They really need to get the space properly set up for wi-fi. And perhaps provide a bit more information on their website. And yet, the event certainly doesn't suffer a lack of crowd...

We wandered; Rose ran around a bit, and even played in the gravel (she was removed against her wishes). Kathy's wee children complained. And I visited with a couple of people there and here I hadn't seen in some time.

Usually, some of the daytime musical entertainments can be, ahem, varied in their quality, but we caught The Brigadoons just before we left, which was quite nice. Rose and I danced a bit, as Kathy and I used up the last of our beer tokens.

The day was long; we were home around 5pm or so, but it meant that we'd been walking for about six or more hours, which explained how we were all exhausted by the end of it.

Once we arrived at the homestead, Rose sat awhile in Gran'pa's chair.

Sunday, August 2, 2015: After a breakfast at the local truck stop, Rose, Kate and I wandered off having adventures for the morning, allowing Christine some quiet time to get some work done. Our pal Clare Latremouille and her husband recently purchased a farm nearby, so we spent the morning with her, getting a lay of the land, and the strange space of land they now get to figure out.

Sunday, August 2, 2015: After a breakfast at the local truck stop, Rose, Kate and I wandered off having adventures for the morning, allowing Christine some quiet time to get some work done. Our pal Clare Latremouille and her husband recently purchased a farm nearby, so we spent the morning with her, getting a lay of the land, and the strange space of land they now get to figure out. The house was absolutely lovely! And Clare and Bryan regaled us with tales of the previous owner, who frightened the neighbours with his strange leavings, creations and pathways, including mirrors (facing in) replacing every window in the house. Rose was enormously happy, given she was immediately given an orange popsickle, and a variety of other foods while we were there. She wandered around the house, dribbling and sticky and laughing. Clare even let her leave with two stuffed toys, including an Ernie.

The house was absolutely lovely! And Clare and Bryan regaled us with tales of the previous owner, who frightened the neighbours with his strange leavings, creations and pathways, including mirrors (facing in) replacing every window in the house. Rose was enormously happy, given she was immediately given an orange popsickle, and a variety of other foods while we were there. She wandered around the house, dribbling and sticky and laughing. Clare even let her leave with two stuffed toys, including an Ernie. The house and the surrounding buildings are impressive, and have an enormous amount of potential. Despite wishing never to move ever again, I was quite jealous of what they've managed to find, and the work they've been putting into it (they're very good at that kind of renovation work, which I haven't a clue about).

The house and the surrounding buildings are impressive, and have an enormous amount of potential. Despite wishing never to move ever again, I was quite jealous of what they've managed to find, and the work they've been putting into it (they're very good at that kind of renovation work, which I haven't a clue about). Once home, we gathered Christine and headed up to my sister's house for her annual bbq, yard-party, whatever it is they call it now (they haven't roasted a pig in years). Rose swam in the pool a bit with her cousins, and spent the remainder of the day running, running, running and running, most of the time calling for her cousin, Emma.

Once home, we gathered Christine and headed up to my sister's house for her annual bbq, yard-party, whatever it is they call it now (they haven't roasted a pig in years). Rose swam in the pool a bit with her cousins, and spent the remainder of the day running, running, running and running, most of the time calling for her cousin, Emma.Occasionally, she would even stop to colour.

By dusk, there was the annual fire, and the eventual fireworks. Rose ran until she couldn't anymore, and Christine convinced her into one of her carriers, where she fell asleep (somewhere around 10 or 10:30pm) on the walk back to the homestead.

By dusk, there was the annual fire, and the eventual fireworks. Rose ran until she couldn't anymore, and Christine convinced her into one of her carriers, where she fell asleep (somewhere around 10 or 10:30pm) on the walk back to the homestead.

Published on August 06, 2015 05:31

August 5, 2015

Erika Staiti, The Undying Present

I haven’t consulted the map. I didn’t know there was a map until after they returned to the car at the beginning and spread it over their laps. I know I am trying to get to the magnified view as indicated. I will have to go through many rooms. In some cases I might have to stay overnight. It all depends.

Oakland, California writer Erika Staiti’s striking first full-length book, The Undying Present (San Francisco, CA: Krupskaya, 2015), exists in the nebulous space between prose poetry and novel. Constructed as a collage-work, The Undying Presentis a pastiche of scene-sections, including scenes presented from multiple perspectives, a set of semi-travel narratives, multiple examples of overlap, deliberate obfuscation and occasional contradition. Writing out a series of movements without specific details, the narrative allows itself to not be limited by a single trajectory or reading. As Ariel Goldberg and Rachel Levitsky wrote in their “Conversation about Erika Staiti’s ‘The Undying Present,’” as part of their “Social reading” series in Jacket2: “Under erasure, constant revision: questions left by Staiti’s outlines and silhouettes must only be answered in multiples, of bodies, desires, expirations hiding from each other, revealed in the reading, by the readers: for how long can a hand be held?” They continue:

In a narrative that is about an underground replete with unspoken dynamics that are probably sado-masochistic, the open field of the mystery is significant. The narrative is not master of its own mystery. The narrator is not in control.

“False harmony warms the network. Secrets eat through the spaces between bodies.”

There is something going on in The Undying Present but it’s a secret. There is a necessity of uncovering the mystery, the structural body of the scene that can’t be addressed singularly by the author who is included in it. How are we going to be asked to question the surface? To get to the matter, when intimacy lapses. The reader is being asked to help.

Narrative, one might argue, is as arbitrary as any other idea upon which to hang a story. Staiti’s narrator is not in control, they write, and yet, it takes a remarkable amount of control to allow such a space for the narrator to drift so artfully, highlighting a comparison and difference between this and, say, Richard Brautigan’s novel Sombrero Fallout: A Japanese Novel (1976), in which narrator, narrative and, supposedly, author erode simultaneously. Staiti’s montage of prose-sections accumulate in such a way that are reminiscent of the novels of Toronto writer Ken Sparling, yet writing out longer scenes than his novels often include. Both writers, somehow, manage to create full-length prose-works that suggest that the order of the sections aren’t fixed, but simply one way of reading; might The Undying Present be equally readable if the sections were re-ordered? Would it make for an entirely different, yet equally satisfying, experience?

Narrative, one might argue, is as arbitrary as any other idea upon which to hang a story. Staiti’s narrator is not in control, they write, and yet, it takes a remarkable amount of control to allow such a space for the narrator to drift so artfully, highlighting a comparison and difference between this and, say, Richard Brautigan’s novel Sombrero Fallout: A Japanese Novel (1976), in which narrator, narrative and, supposedly, author erode simultaneously. Staiti’s montage of prose-sections accumulate in such a way that are reminiscent of the novels of Toronto writer Ken Sparling, yet writing out longer scenes than his novels often include. Both writers, somehow, manage to create full-length prose-works that suggest that the order of the sections aren’t fixed, but simply one way of reading; might The Undying Present be equally readable if the sections were re-ordered? Would it make for an entirely different, yet equally satisfying, experience?Staiti is also the author of the chapbooks Verse/Switch & Stop-Motion (2008), In the Stitches (Trafficker Press, 2010) andBetween the Seas (Aggregate Space & Featherboard Writing Series, 2014), and in an interview conduced by Ariel Goldberg, Staiti discusses In the Stitches in a way that seems to connect to this current work: “There is some kind of world in which this language is existing but I don’t really know what it is. It’s partly an imagined/fantasized world but it steals objects and ideas from our world. I don’t feel so literate in this world at all. I feel pretty removed from it. In the earliest version, I was trying to write lines that would negate themselves. I wanted to see what something looked like if it could be itself and also its own negation. I was writing longhand, which I almost never do. As the piece over time transformed into this thing, I realized that something kind of ambient but real came out in the attempt to negate. I thought a lot about ambience. I wanted to see a world in which ambience dominated. It’s interesting about the different voices you mentioned because I’ve been hearing it as un-voiced, as a humming or something.” In remarkably precise prose, Staiti appears very much to be creating a world through halved information, presenting just enough to create an incomplete portrait, and make the reader aware of what might be missing. One might say that this new work is just as much ambient than setting or narrative, suggesting what another writer would have fleshed out more fully, yet most likely lessening the effect.

I walk through the City of Margins. Tall angular buildings shimmer in the sun. Dozens of people move past me walking in straight lines with conviction. I am moving in this way too. The streets push us to our destinations efficiently. We push ourselves there.

A narrow alleyway appears. I turn and walk down the torn street. I reach an empty parking lot. I feel the Second City beneath me. The shell of a burned out car sits at the edge of the frame. An abandoned and deteriorating building sags into the ground. This is where we enter.

I open the doors of the building and walk around peering in each room. The rooms hold remnants of the past, forgotten objects slathered in dust and rodent feces. I climb the stairs dragging knobby fingers over a dusty banister. A young woman is crumpled in the corner at the end of the hallway. Her body is a mouth, a dark open hole telling a story. Speaking not speaking.

Published on August 05, 2015 05:31

August 4, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Leslie Vryenhoek

Leslie Vryenhoek is the acclaimed author of

Scrabble Lessons

(short fiction) and Gulf (poetry). Her first novel,

Ledger of the Open Hand

, published in May 2015, looks at how our relationship with money colours how we relate to our loved ones, and how we come to treat love as a balance sheet. Leslie’s work has been published and broadcast across Canada and internationally, winning awards across genres. As a communications specialist, Leslie has worked in advanced education, international development, emergency response, and the arts. A former Manitoban now based in St. John’s, Newfoundland, she is the founding director of Piper’s Frith: Writing at Kilmory. There’s more at www.leslievryenhoek.com.

Leslie Vryenhoek is the acclaimed author of

Scrabble Lessons

(short fiction) and Gulf (poetry). Her first novel,

Ledger of the Open Hand

, published in May 2015, looks at how our relationship with money colours how we relate to our loved ones, and how we come to treat love as a balance sheet. Leslie’s work has been published and broadcast across Canada and internationally, winning awards across genres. As a communications specialist, Leslie has worked in advanced education, international development, emergency response, and the arts. A former Manitoban now based in St. John’s, Newfoundland, she is the founding director of Piper’s Frith: Writing at Kilmory. There’s more at www.leslievryenhoek.com.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?My first book, Scrabble Lessons (short stories), changed my life by disabusing me of the notion that publishing a book would change my life. Other things, like deciding to change my life, have been much more effective.

Writing those stories, I wasn’t part of a “writing community” yet. I had such confidence in my voice and my ability and felt really comfortable inside the skin of the stories. By the time Scrabble Lessons was published, I’d moved across the country and in with another writer, and I was suddenly surrounded by writers whose own first books had garnered big acclaim, catapulting them into hot careers. My experience was different—and my confidence took a beating. I’m not proud of it, but there it is.

So when I began Ledger of the Open Hand, I allowed external advice to rule and dismissed my instincts. It took me a long time to come back to my own voice and intent. Ultimately, though, I think the circuitous journey made me a better writer and produced a better book.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?I didn’t come to fiction—or any genre—first. I came to words first—words, and the desire to arrange them in ways that created an understanding, a different way of seeing, both for me and for the reader or listener.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?It’s very changeable, project to project. Some things arrive whole in my head—so immediate, so just there that I can’t scribble fast enough to get them down. Those are the best experiences—and usually the best pieces.

More often, whatever I’m writing will emerge as I’m writing it, unspooling just far enough out in front to keep me moving, the way an unfamiliar highway does when you drive it at night. The trick, I find, is to not to speed up and overdrive the headlights.

I jot notes when I’m conceiving a larger project, before it’s gelled enough to start typing. But I end up ignoring most of them. I go back to writing out notes when I’m editing, redrafting, rethinking—that for me is where the best creative work happens, and those notes prove far more useful.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?There’s always some seed—some idea or character I want to get inside, so I have to find the best way to get at it. It’s intuitive. Usually I know quickly if it’s a poem or a short story, an essay or a novel. I’ve never started anything thinking it would be short and then had it develop into something longer—a story that became a novel, for example—but I’ve sure embarked on long narratives, only to realize I didn’t have that much to say after all.

What it’s all to become is often less obvious. Stories and poems often begin as discrete, and then I realize there’s something larger evolving, some vein I’m mining.

5 – Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?I love reading. I love microphones. Maybe I love being the centre of attention. I’m the sort who needs to be disciplined about a time limit (and I am) because I could stand up there and read the whole damn book as long as I thought people were (even politely) listening. The magic of it is in seeing how the audience responds—because you rarely get to hang over someone’s shoulder while they’re reading your stuff.

6 – Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?When another writer said to me, “We all have some core issue we return to in different ways, hoping to resolve it,” I realized my thing might be “But it’s not fair.” I’m not sure that actually qualifies as a theoretical concern so much as my inner four-year-old’s lament, but the imbalance of give and take in life—certainly in relationships—seems to keep coming up. I suppose the question behind it that interests me is just how much luck, good and bad, plays in the average life, how much is what we’re dealt and how much is what we choose. In Ledger, the uneven distribution of life’s rewards, of good fortune and good feelings, love and money, are undercurrents throughout the novel. In a small way, in a microscopic way, I’m trying to interrogate the larger issues about inherent inequity in the way the world works.

I also return, over and over, to the concept of belonging. The poetry in Gulf was concerned with how to define home. A new project that’s hovering in my peripheral vision and just starting to coalesce is focused on what it means to belong to a place—who gets to claim it and whether it’s granted externally or found within.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?God, that’s the question that’ll keep me up all night. I don’t have anything close to a solid answer, so allow me to equivocate. I think there are as many roles as there are writers. There’s room for entertaining, and there’s room (sometimes in the same house) for the hard reality of deep journalism. Most of us, writing in any genre, are trying to reveal something, small or large, about the world in which we find ourselves.

But we are at a very tricky place in our evolution—as a nation, as a global community—and a century or two from now, people are going to scour what we’re creating today for some understanding about how we got here and how we responded, and I’m hoping there are a few good writers who will last to shed some honest light on the early part of the 21st century.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)? Utterly essential, once the work is far enough along. It’s like having someone come into your new house after you’ve arranged the furniture and say, “You know, if you just moved that there and turned it sideways, you’d open up the whole space.” What a different brain can see always amazes me.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?Annie Dillard—and I’m very much paraphrasing—said something like, “Don’t hoard the best stuff. Use it and trust more good stuff will come.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to short stories to the novel)? What do you see as the appeal?It’s easy across a long span of time, though when I’m working in a particular genre I stay there. Usually for months. I can switch gears between two prose pieces, but I can’t write a poem in the morning and a story in the evening. I wish I could, because poetry opens up channels for using language and emphasizes potency and brevity in a way that is very good for my prose.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?I tend to have a lot of obligations—contract and volunteer work, family responsibilities, online Scrabble games—so my routines are always changing. As a result, I write in big, concentrated blocks, quite obsessively for days at a time when the world isn’t pulling on my sleeve. I would love to be able to write a few hours each morning, but when I get going I have trouble stopping. So I like to clear my schedule and then write like mad.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?Much depends on the nature of the stall. A long, fast walk if I’m just jammed. Our old country house in a small Newfoundland outport if I’m utterly lost. Vodka if I’ve just lost my nerve.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?My head went straight to: Home? Please define your terms. My gut went straight to lilacs. Lilacs and Ozonal.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?Conversations, whether they involve me or not. Eavesdropping, especially when I have to fill in the blanks. Also news stories that leave something to the imagination. Much like Daneen in Ledger, I pilfer other people’s juicy details, plunder their screwed up families.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?My husband is a writer, and a fantastic cook. He feeds me, which I find essential to my work. Also, sometimes other writers invite us over and feed us. Very important. Especially if they let something slip about their screwed up families over the main course.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?1. Write a screenplay. 2. Hike by myself through the southwestern US—Utah, Nevada, New Mexico. I’m certain there’s something waiting for me there, though I have no idea what. Death by tarantula, perhaps.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?For many years I worked in communications—public relations, all that—which is part writing, but also the opposite of writing in the sense we’re talking about here. And I loved it: loved honing the message, loved managing crises, loved deflecting the heat in heated interviews. The desire to focus on my own writing took me away from that career, but I might go back to it yet if the right opportunity presents itself.

My other fantasy career: house painter (interiors only and get to pick the colours).

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?I did do something else. And then something else and something else again, all in a vain attempt not to write. But the writing kept banging on my door, so I let it in and then bam, next thing I knew I got used to not having to leave the house every morning—and to asserting ideas that were actually my own.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill recently blew me away. Gorgeous, evocative, gutting. The last great film I saw was probably a television series: Scott & Bailey comes immediately to mind. I’m enamoured of the TV that’s happening these days, especially in Britain and Scandinavia. Sharp writing, complex characters, and no pat answers.

20 - What are you currently working on?I have a pretty solid idea for another novel that I’ve just started about interconnectivity—in nature, among people, and through the internet—and the near impossibility of escaping the past. But just now I’m longing to write something short and saucy, so I might detour into short stories to satisfy that craving.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on August 04, 2015 05:31

August 3, 2015

new from above/ground press: Robinson + Markotić

Simplified Holy Passage

Simplified Holy PassageElizabeth Robinson

$4

See link here for more information

ins & outs

Nicole Markotić

$4

See link here for more information

keep an eye on the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material;

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

July 2014

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

To order, send cheques (add $1 for postage; outside Canada, add $2) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9 or paypal (above). Scroll down here to see various backlist titles (many, many things are still in print) or see the sidebar list of names on the above/ground press blog.

Review copies of any title (while supplies last) also available, upon request.

Forthcoming chapbooks by Amanda Earl, Ashley-Elizabeth Best, Hugh Thomas and Katie L. Price!

and don’t forget about the above/ground press 22nd anniversary reading/launch/party on August 27th!

Published on August 03, 2015 05:31

August 2, 2015

A short interview with Meredith Quartermain

My short interview with Vancouver writer Meredith Quartermain on her new work of short fiction,

I, Bartleby

(Talonbooks, 2015), is now online at Queen Mob's Teahouse.

My short interview with Vancouver writer Meredith Quartermain on her new work of short fiction,

I, Bartleby

(Talonbooks, 2015), is now online at Queen Mob's Teahouse.

Published on August 02, 2015 05:31

August 1, 2015

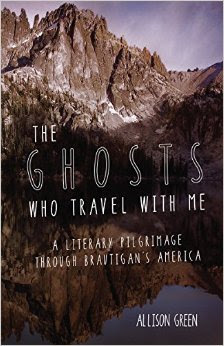

Allison Green, The Ghosts Who Travel With Me: A Literary Pilgrimage Through Brautigan’s America

Brautigan’s books offered more than a bohemian world, where pretty women made their poet lovers paintings and wore nothing under their pretty dresses. His books gave me words and sentences, rhythms, a style. He was the first lyrical writer I’d ever read, the first writer more interested in sentences and words than story. I responded by shrugging into the pajama sleeves of his style.And then, again, there was the sex. In one chapter of Trout, the narrator and his wife have sex in a hot springs. She asks him to pull out early and, Brautigan writes, “My sperm came out into the water, unaccustomed to the light, and instantly it became a misty, stringy kind of thing and swirled out like a falling star.” I’m thirteen, in my aunt and uncle’s postwar house after my cousins have gone to sleep. I read this passage and turn back to the cover of the book, with its black-and-white photograph of Brautigan with an unidentified woman. He is wearing what looks like a felt hat, a pinstriped vest over a paisley shirt, a peacoat, and two strands of beads. She has granny glasses, a lace headband, and a cape over a skirt. They are the kind of people who have sex in hot spring pools and later write about it. They are people I could become. My little cousins are sleeping, and I’m almost done reading Trout Fishing in America. I haven’t closed the curtains, even as night has fallen. My aunt and uncle’s house is perched on a hill in the Magnolia neighborhood, and if I were to walk to the window I would see the streetlights across the valley, shining in the cold. But instead, I look at myself in the glass and wonder whether his world is one I’ll ever enter.

I admit to being uncertain, yet intrigued, when I first heard of Seattle, Washington writer Allison Green’s [see my recent interview with her here]

The Ghosts Who Travel With Me: A Literary Pilgrimage Through Brautigan’s America

(Portland OR: Ooligan Press, 2015). There have been dozens of books on the late Beat writer Richard Brautigan, spawning multiple ‘pilgrimage’ titles over the past few decades, yet the handful of titles I’ve seen so far include a wide variety of quality. Given this, I wasn’t sure what to expect from Allison Green, a writer I hadn’t previously heard of.

I admit to being uncertain, yet intrigued, when I first heard of Seattle, Washington writer Allison Green’s [see my recent interview with her here]

The Ghosts Who Travel With Me: A Literary Pilgrimage Through Brautigan’s America

(Portland OR: Ooligan Press, 2015). There have been dozens of books on the late Beat writer Richard Brautigan, spawning multiple ‘pilgrimage’ titles over the past few decades, yet the handful of titles I’ve seen so far include a wide variety of quality. Given this, I wasn’t sure what to expect from Allison Green, a writer I hadn’t previously heard of.Since I first read Richard Brautigan’s Revenge of the Lawn: Stories 1962-1970 (1972) as a seventeen year old [see my write-up on such here], I’d been hooked. I read every book I could get my hands on, moving eventually from titles by Brautigan to titles on him, from essays, poems, memoirs and travelogues, as well as a very fine memoir by his daughter, Ianthe. It took six months for me to read through the thousand pages of his recent biography, a book absolutely incredible for its attention, scope and detail (I really can’t recommend it enough). The lack of new material on Brautigan, I suspect, drove a number of us to write our own works on Brautigan. My own attempts include a poetry collection, and a fiction work-in-progress.

Composed in five sections of short, self-contained sections, Green’s creative non-fiction work The Ghosts Who Travel With Me: A Literary Pilgrimage Through Brautigan’s America accumulates much in the way Brautigan’s own prose did, and explores her own love of his writing through a highly entertaining memoir of a series of trips she and her partner took across Brautigan’s geography, taking her map directly from Trout Fishing in America (1967). Composed as a love letter to Brautigan’s writing, she writes of the bucket list she made when she was thirteen, including the wish to meet the author: “Why him? I keep asking myself. Why, of all people, Richard Brautigan?” She writes of, being born in 1963, just missing out on a cultural movement that America had simply moved on from, which kept calling her back. The summer she was twelve, she discovers his work in a library:

The sentence on the cover was the most beautiful sentence I had ever read: “In watermelon sugar the deeds were done and done again as my life is done in watermelon sugar.” Three times the word “done,” like a bell tolling. A life somehow lived in sweet, pink juice, distilled to its essence. I looked up at the librarians, the shelves of books, the men reading newspapers, and said the sentence under my breath, glancing back at the cover until I had it memorized. The book as an object was itself a distillation of what I perceived to be hippie culture—and this was the mid-1970s, so the culture was waning. Hippies meant plain but beautiful women and earnest, artistic men. The black and white of the photo signaled an authentic aesthetic, simple and true. The design, with the first sentence of the novel on the cover, meant anything could happen. And the book was small and slender, like a poem in my pocket. I took the sixties home with me.

With sections “The Girl from Idaho,” “Generation Jones,” “Richard Brautigan Slept Here,” “Ancestors” and “Mayonnaise,” as well as a short “Epilogue,” the narrative does spend much of the first section warming up, but quickly develops into an impressive combination of memoir, essay, travelogue and unapologetic tribute to Brautigan, as she explores her relationship to that work through travel. As she writes:

By the end of the 1970s, the mood in the United States—at least in my United States—was bleak. Tom Wolfe said the older baby boomers, my heroes, had become obsessed with themselves and were no longer championing the greater good. President Carter was wearing sweaters and telling us to turn down the thermostat if we didn’t like energy prices. And one more thing: disco. In a cultural and adolescent funk, I took refuge in Brautigan. He inhabited an America of hope and imagination, of surreal but engrossing dreams. And what exactly was the nature of those dreams? That was one of the things I went to Idaho to find out.

The Ghosts Who Travel With Me: A Literary Pilgrimage Through Brautigan’s America is a compelling travelogue, and a worthy addition to the plethora of titles on and around Richard Brautigan, exploring a space and a time in American myth, and how one attempts to live in the present, against all of that history. There might be occasional moments in the book that wane, but overall, Green’s Ghosts are impressive, even including sections that transcend themselves in the most magnificent ways, such as “Abraham, Martin and John” that opens: “Girls at slumber parties have séances. Girls at slumber parties in the early 1970s had séances to raise the spirit of John F. Kennedy.” The three page piece ends:

Laura opened my orange-and-white plastic record player and set the arm on the 45 record she had brought. By the time the singer asked if we’d seen John, tears streamed down our cheeks. The good died young, and weren’t we good? But I think we were crying for more than our young selves. I think we had absorbed the sadness of our parents who held us in their arms when the man they’d felt such passion for died. And the despair they felt, five years later, when those other beacons of hope were taken from this earth forever. Our séances didn’t call forth an assassinated president; our séances called forth our parents’ sorrow.

Published on August 01, 2015 05:31

July 31, 2015

A short interview with Andy Weaver

My short interview with Toronto poet Andy Weaver on his forthcoming third poetry collection, this (Chaudiere Books, 2015), is now online at Queen Mob's Teahouse.

My short interview with Toronto poet Andy Weaver on his forthcoming third poetry collection, this (Chaudiere Books, 2015), is now online at Queen Mob's Teahouse.

Published on July 31, 2015 05:31

July 30, 2015

On Writing : an occasional series

We're more than two years and nearly seventy posted essays into the occasional series of "On Writing" essays I've been curating over at the ottawa poetry newsletter blog. I've included an updated list, below, of those pieces posted so far, and the list is becoming quite substantive. Way (way) back in April, 2012, I discovered (thanks to Sarah Mangold) the website for the NPM Daily, and absolutely loved the short essays presented on a variety of subjects surrounding the nebulous idea of “on writing.” I would highly recommend you wander through the NPM Daily site to see the pieces posted there.

We're more than two years and nearly seventy posted essays into the occasional series of "On Writing" essays I've been curating over at the ottawa poetry newsletter blog. I've included an updated list, below, of those pieces posted so far, and the list is becoming quite substantive. Way (way) back in April, 2012, I discovered (thanks to Sarah Mangold) the website for the NPM Daily, and absolutely loved the short essays presented on a variety of subjects surrounding the nebulous idea of “on writing.” I would highly recommend you wander through the NPM Daily site to see the pieces posted there.Forthcoming: new essays by Jennifer Kronovet, Natalie Simpson, Susannah M. Smith, Rebecca Rosenblum, Renee Rodin, Pam Brown and Sheryda Warrener.

On Writing #67 : George Stanley : Writing Old Age : On Writing #66 : George Fetherling : On Writing : On Writing #65 : Gail Scott : THE ATTACK OF DIFFICULT PROSE : On Writing #64 : Laisha Rosnau : The Long Game ; On Writing #63 : Arjun Basu : Write ; On Writing #62 : Angie Abdou : The Writer & The Bottle ; On Writing #61 : Carolyn Marie Souaid : Lawyers, Liars & Writers ; On Writing #60 : Priscila Uppal : On Creative Health ; On Writing #59 : Sky Gilbert : Yes, They Live ; On Writing #58 : Peter Richardson : Cellar Posting ; On Writing #57 : Catherine Owen : "Bright realms of promise": ON THE POETIC ; On Writing #56 : Sarah Burgoyne : a series of permissions-givings ; On Writing #55 : Anne Fleming : Funny ; On Writing #54 : Julie Joosten : On Haptic Pleasures: an Avalanche, the Internet, and Handwriting ; On Writing #53 : David Dowker : Micropoetics, or the Decoherence of Connectionism ; On Writing #52 : Renée Sarojini Saklikar : No language exists on the outside. Finders must venture inside. ; On Writing #51 : Ian Roy : On Writing, Slowly ; On Writing #50 : Rob Budde : On Writing ; On Writing #49 : Monica Kidd : On writing and saving lives ; On Writing #48 : Robert Swereda : Why Bother? ; On Writing #47 : Missy Marston : Children vs Writing: CAGE MATCH! ; On Writing #46 : Carla Barkman : Tastes Like Chicken ; On Writing #45 : Asher Ghaffar : The Pen: ; On Writing #44 : Emily Ursuliak : Writing on Transit ; On Writing #43 : Adam Sol : How I Became a Writer ; On Writing #42 : Jason Christie : To Paraphrase ; On Writing #41 : Gary Barwin : ON WRITING ; On Writing #40 : j/j hastain : Infinite Chakras: a Trans-Temporal Mini-Memoir ; On Writing #39 : Peter Norman : Red Pen of Fury! ; On Writing #38 : Rupert Loydell : Intricately Entangled ; On Writing #37 : M.A.C. Farrant : Eternity Delayed ; On Writing #36 : Gil McElroy : Building a Background ; On Writing #35 : Charmaine Cadeau : Stupid funny. ; On Writing #34 : Beth Follett : Born of That Nothing ; On Writing #33 : Marthe Reed : Drawing Louisiana ; On Writing #32 : Chris Turnbull : Half flings, stridence and visual timber ; On Writing #31 : Kate Schapira : On Writing (Sentences) ; On Writing #30 : Michael Bryson : On Writing ; On Writing #29 : Sara Heinonen : On Writing ; On Writing #28 : Stan Rogal : Writers' Anonymous ; On Writing #27 : Lola Lemire Tostevin : What's in a name? ; On Writing #26 : Kevin Spenst : On Writing ; On Writing #25 : Kate Cayley : An Effort of Attention ; On Writing #24 : Gregory Betts : On Writing ; On Writing #23 : Hailey Higdon : Hiding Places ; On Writing #22 : Matthew Firth : How I write ; On Writing #21 : Nichole McGill : Daring to write again ; On Writing #20 : Rob Thomas : Hey, Short Stuff!: On Writing Kids ; On Writing #19 : Anik See : On Writing ; On Writing #18 : Eric Folsom : On Writing ; On Writing #17 : Edward Smallfield : poetics as space ; On Writing #16 : Sonia Saikaley : Writing Before Dawn to Answer a Curious Calling ; On Writing #15 : Roland Prevost : Ink / Here ; On Writing #14 : Aaron Tucker : On Writing ; On Writing #13 : Sean Johnston : On Writing ; On Writing #12 : Ken Sparling : From some notes for a writing workshop ; On Writing #11 : Abby Paige : On the Invention of Language ; On Writing #10 : Adam Thomlison : On writing less ; On Writing #9 : Christian McPherson : On Writing ; On Writing #8 : Colin Morton : On Writing ; On Writing #7 : Pearl Pirie : Use of Writing ; On Writing #6 : Faizel Deen : Summer, Ottawa. 2013. ; On Writing #5 : Michael Dennis : Who knew? ; On Writing #4 : Michael Blouin : On Process ; On Writing #3 : rob mclennan : On writing (and not writing) ; On Writing #2 : Amanda Earl : Community ; On Writing #1 : Anita Dolman : A little less inspiration, please (Or, What ever happened to patrons, anyway?)

Published on July 30, 2015 05:31

July 29, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Suzette Bishop

Suzette Bishop teaches at Texas A&M International University in Laredo, Texas. She has published three books of poetry,

Horse-Minded

and She Took Off Her Wings and Shoes, and a chapbook,

Cold Knife Surgery

. Her third book,

Hive-Mind

, was released January 2015. Her poems have appeared in many journals and in the anthologies Imagination & Place: An Anthology, The Virago Book of Birth Poetry, and American Ghost: Poets on Life afterIndustry. A poem from her first book won the Spoon River Poetry Review Editors’ Prize Contest. In addition to teaching, she has given workshops for gifted children, senior citizens, writers on the US-Mexico border, at-risk youth, and for an afterschool arts program serving a rural Hispanic community.

Suzette Bishop teaches at Texas A&M International University in Laredo, Texas. She has published three books of poetry,

Horse-Minded

and She Took Off Her Wings and Shoes, and a chapbook,

Cold Knife Surgery

. Her third book,

Hive-Mind

, was released January 2015. Her poems have appeared in many journals and in the anthologies Imagination & Place: An Anthology, The Virago Book of Birth Poetry, and American Ghost: Poets on Life afterIndustry. A poem from her first book won the Spoon River Poetry Review Editors’ Prize Contest. In addition to teaching, she has given workshops for gifted children, senior citizens, writers on the US-Mexico border, at-risk youth, and for an afterschool arts program serving a rural Hispanic community.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?My chapbook, Cold Knife Surgery, was edited with a loving hand by Laura Qa, the editor of Red Dragon Press. That was a life-changing experience, having another writer and editor believe in my work that much, an astonishing faith in my work after four long years of rejection. She also asked me to write a Forward about the long poem comprising the manuscript. As the poem was about surviving cervical cancer and the kinds of invasive procedures used in the early 1990's to diagnose and treat it, summarizing what I was trying to do and say became a final step of healing, for me. The exercise relegated cervical cancer to the past instead of something I kept re-living.

I continue to want the free verse lyric poem and the experimental long prose poem in my life and go back and forth between the two, seeing how one might inform the other. My most recent book, Hive-Mind, starts with lyric poems and then shifts to collaged prose poems and then to phrases scattered across the page, while Cold Knife Surgery is all one long collage prose poem. The chapbook has lyric moments, I think, but doesn’t include both types of forms the way my recent book does. The narrative of Cold Knife Surgery is disrupted but basically follows a straight line from my cancer diagnosis to post-surgery. Hive-Mind, on the other hand, attempts to tell the story of Colony Collapse Disorder and of beekeepers with my life at times intersecting. The narrative is more recursive and also is about a shifting of shapes: hive-like centered poems, bees gathered on a screen in a hive box, swarming.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?Actually, I started with fiction. I had very little exposure to reading or writing poetry until my senior year in high school, and, honestly, little interest in it! I wasn’t able to enroll in my college intro creative writing class my freshman year because it was too full, but a poet, Stuart Friebert, agreed to a poetry independent study for my Winter Term project based on the poems I had written in high school. He prescribed “shock therapy” as he called it, giving me a long list of mostly contemporary female poets to look up and read in the snowbound library. He also required me to write three poems a week. Stuart usually felt one poem was strong, much to my surprise, a second poem weak but had potential with a lot of work, and a third poem needed to “go in the attic” as he would put it. Once I took the intro creative writing class my sophomore year, I found myself falling in love with poetry and filling up the five-page weekly requirement with poems more than with stories as the course progressed. Something cliqued for me about the way I’ve always thought metaphorically and through images.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?It varies. A short lyric poem draft happens quickly, but how long it will take me to revise it and tinker with it is anyone’s guess, from a few hours to years. The idea for a collage poem may occur to me suddenly, but executing the idea is a slower piecing kind of work, like quilting. Yes, I will take notes on subjects requiring research, such as bees and beekeeping, and some poems or parts of them will result from the notetaking.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?It was difficult to get started on new poems right after my first book publication because it became clear I needed to shift to thinking more about working on a book from the very beginning. The first book came together in an organic way after creating a body of work and selecting poems from that body of work that fit together. But a second poetry book, I realized, involved more planning up front and stifling of the voice that questioned whether I could produce another book as good as, if not better, than the first book. Listening to music helped a lot to stifle that voice. Having an idea, as vague as it might be, about a subject matter for a book and calling it a “project” also helps with the way I work around the academic calendar and with the critical voice in my head. I will end up with poems that don’t fit with the project, too, and those I’ll submit separately to literary magazines or allow to sit to see if they may develop into a different book project.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?Well, I’m an introvert. I’m also an introvert who works as a professor which forced me to get more comfortable with public speaking. It’s a double-edged sword, however, as I can use up my limited energy for social interaction by the end of a work week and need the weekend, when readings are usually scheduled, to recharge. Rather than simply “shyness,” introversion is also about the way social interaction takes more energy for introverts than for extroverts and the way introverts can experience sensory overload in social environments. Add Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Fibromyalgia to the mix, and I find I have to be ruthless about pacing my social interactions and getting in enough quiet and solitude to recharge. I’ve struggled, too, with how to translate the visual qualities of my work in a reading forum. How my poems look on the page is important to me. I worked up a pdf of my poems for my second book and have done the same for Hive-Mind. It was great to finally feel that an essential part of my work wasn’t be lost during readings.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?I have no idea if the questions are answered in my work or how relevant those questions may be for other writers, but I ask myself two questions: what happens when I approach poetics and form with both/and thinking instead of either/or thinking, and what can I make use of to piece together like squares of cloth for a quilt. I’m guessing the second question may come from a background that includes poverty and near-homelessness as I had to become good at making due with what I had. For poetry, the “pieces” I use are my experiences, the approaches and techniques I was taught by my teachers, what I read, other texts. The first question may in part come from an association of either/or thinking with schools of poetry in the past that didn’t include women or relegated them to a position of being seen but not heard.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?Poetry’s readership is very limited, and if print runs are any indication, typically 1,000 copies when my first book came out in 2003, 100 print-on-demand copies today, the readership is shrinking. Even when it was 1,000 copies, nearly half were bought by university libraries and may have never been checked out. Despite that grim reality, I continue to write and hope my work will affect at least a few people. Validating others’ creativity, whether it’s been in the classroom or through nonprofit organizations, has been a helpful service, I hope. It’s a part of who we are that gets denounced or devalued, and I feel priviledged to be in a position to have constructed some safe zones for creative expression.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?I’ve been very grateful to my book editors. My current editor at Stockport Flats Poetry, Lori Anderson Moseman, like Laura Qa, devoted a tremendous amount of her time editing and designing my manuscript. I think the book is much the better for it. And she kept me on task and provided encouragement and cheering when I needed it.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?Persistence. I wrote my first poem my senior year in high school but didn’t get a poem published in a literary magazine (other than my college literary magazine) until ten years later. I submitted my chapbook to zillions of presses for four long years until a small press accepted it. My second book involved another four years of submitting before accepted, the current one, three years. There were a lot of rejection letters during those years, and rejection letters will continue to be in my life. Keep submitting.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?I think, now, more about a writing routine over a year's trajectory than a daily one. I teach at Texas A&M International University, a fairly new university of primarily first-generation students with a newly implemented creative writing minor I helped to develop. In other words, there’s labor-intensive building from the ground up to do. Teaching has priority for me over writing once the semester is underway. I don't seem to be wired to limit how much time and energy I put into lesson plans, grading, or responding to students' or programmatic needs. It just doesn't seem right to do that. So, it becomes a 7-day work week once the semester is underway. I steal time to do low-stakes writing, such as writing in my journal, doing freewriting while a class is doing an in-class writing exercise, or doing reading and researching. Happily, I end up tricking myself into producing more rough drafts of poems than I think I will or than I ever did when trying (unsuccessfully) to keep to a daily routine. The holiday break and summer are when I do the more intensive, high-stakes writing and revising, avoiding a clock as much as possible.

My day will begin very differently depending on what time of the week or year it is. During the school year on a school day? It starts by rushing to get ready for work and out the door. During the summer, I'll head straight to the computer to answer emails, work on poems, and then fix some breakfast when I'm ready for a break.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?To my experiences, observations, dreams, reading, day-dreaming.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?When I open a book to the title page, that smell.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?My current book, Hive-Mind, is about bees while my previous book, Horse-Minded, also included poems about environmental concerns and disease. Cold-Knife Surgery was informed by what I was reading about the scientific research of cervical cancer. My first book, She Took Off Her Wings and Shoes, included a section of poems based on female visual artists, with some additional poems on that included in Horse-Minded. Although not declared, I had enough college credits for an art history minor and had taken some art courses and worked in the college museum. I’m also married to an art historian. I have very fond memories of the classical music environment at Oberlin because of the conservatory. One of my roommates was very musical, another was a celloist, I dated an oboist, and there were always free concerts and recitals.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?Memoirs and biographies seem to be what I’ve been craving lately for my life outside of work. Those of other female writers and artists, of course, but more recently, memoirs by survivors of dysfunctional and poverty-striken families like my own: Let the Tornado Come by Rita Zoey Chin and The Glass Castle by Jeannette Walls.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?Combine my love of therapeutic horseback riding which I do for CFS/FM with therapeutic writing for a community in need.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?Many years and pounds ago, I was returning to college, taking a bus from New York City back to Oberlin, Ohio. A gentleman sat down next to me after looking me up and down. My first thought was that this was going to be a really long trip. His first words changed my first impression as he asked me if I had ever thought about exercising racehorses. He turned out to be a racehorse trainer, and he gave me his card to contact him. I sometimes wonder what it would have been like if I had contacted him. Anyway, it was a very congenial bus ride and the time flew by.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?Poetry records what it’s like to be alive, to be human. I love the way a poem can slow down or stop a moment and describe all the internal and external facets of that moment. Given our rushed lives, poetry allows us to slow down and look at something closely and to even see what someone else sees and experiences. I love the chance to reach someone else and move another person, make someone laugh or see things in a new way or articulate something someone may have always known or felt. I like the challenge of working with language in a new and surprising way, especially visually on the page, getting the reader to even pause for a moment to look at the poem's shape and "see" the images I've created. Given our overly hectic days, I think we need those moments of contemplation more than ever. And writing poetry provides a rare opportunity to be completely honest.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film? Emily Dickinson: The Gorgeous Nothings edited by Marta Werner and Jen Bervin, compiling Dickinson’s envelope writings. I watched Sense and Sensibility again last week.

19 - What are you currently working on?I’m working on a series of poems about an endangered species. I have fifteen poems so far, and I’m not sure if it will be a chapbook or a book or a section of a book. We’ll see!

12or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on July 29, 2015 05:31