Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 368

September 26, 2015

bibliography of ottawa literary magazines and presses,

Given the recent appearance of bins of material in our household, thanks to John White donating a wealth of materials from his late mother's library (the Ottawa poet Jane Jordan),

I've been prodded to, yet again, attempt to track a history of Ottawa literary magazines and presses, which I've been constructing here

. The interviews I've been doing lately (with Colin Morton on Ouroboros and Blaine Marchand on Sparks) are part of the same project, with forthcoming interviews with b stephen harding on graffito: the poetry poster, and Victoria Vernell on Hook & Ladder magazine (with, hopefully, further interviews to come). Given how little most of this material has ever been discussed or tracked, and how quickly activity is forgotten, it seems important to acknowledge.

Given the recent appearance of bins of material in our household, thanks to John White donating a wealth of materials from his late mother's library (the Ottawa poet Jane Jordan),

I've been prodded to, yet again, attempt to track a history of Ottawa literary magazines and presses, which I've been constructing here

. The interviews I've been doing lately (with Colin Morton on Ouroboros and Blaine Marchand on Sparks) are part of the same project, with forthcoming interviews with b stephen harding on graffito: the poetry poster, and Victoria Vernell on Hook & Ladder magazine (with, hopefully, further interviews to come). Given how little most of this material has ever been discussed or tracked, and how quickly activity is forgotten, it seems important to acknowledge.Cameron Anstee did a write-up of Ottawa poetry anthologies in 2014 also worth looking at, and Pearl Pirie put together a more recent list of Ottawa literary activity as well. Consider my ongoing list a work-in-progress, with updates/corrections/additions very welcome.

Published on September 26, 2015 05:31

September 25, 2015

Daniel Scott Tysdal, Fauxccasional Poems

Tell Me HowComposed by Buddy Holly, January 24, 1986, for his wife Maria Elena Holly, on the occasion of his flight home from New York after his induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Originally published in the liner notes for Buddy Holly’s Greatest Hits: Volume 3. MCA, 1988.

“It’s magic!” squeals the boy acrossthe airplane’s aisle, his explanationfor flight. I couldn’t agree more, returningto you. Each day, during this week apart,I was a dark-trapped rabbiteager to be revealed to the vastapplause of your smile. Tell me, how magicis the airplane in making possiblethis trick? How airplane-like is magicwith the flights of its surprise?

How upward lifting are the tricksyou perform? With a wave of your hand,you transform all that ever wasfor us and will be, every momentin parting and mile apart, into the nowof our first and last touchand every touch between.

It would be easy to feel overwhelmed by the expansive montage that makes up Toronto poet and critic Daniel Scott Tysdal’s third poetry collection, Fauxccasional Poems (Fredericton NB: Goose Lane Editions / icehouse poetry, 2015). Following his first two collections— Predicting the Next Big Advertising Breakthrough Using a Potentially Dangerous Method (Regina SK: Coteau Books, 2006) and The Mourner’s Book of Albums (Toronto ON: Tightrope Books, 2010)—Tysdal’s poems in Fauxccasional Poems are a wonderfully playful mix of pop culture, philosophy, historical detail, classical forms and tabloid parlance, much of which exist as framing for a series of lyric narratives that twist, cajole and even contain the occasional surreal shift. Tysdal composes sonnets, pantoums and other structured forms on subjects as diverse as the Taliban, Kermit the Frog, Buddy Holly, Nicholas Cage and T.S. Eliot. However playful and even outrageous at times his subject matter and framings might be, the poems themselves are classically formed, managing an intriguing blend of formal experimentation within highly conservative structures. Through his experimentation, Tysdal shows himself to be very much an admirer of the very forms he twists and collides, allowing new life and breath into structures that so rarely allow for the possibility of real experimentation. In this, for example, one could compare his work to that of Montreal poet David McGimpsey [see my recent piece on him in Jacket2 here].

Sleepless, I watch the clip of myself on my iPad,the girls pressed tight as a pair of tires to the chassisof my arms. Abbott and Costello Meet Frankensteinplays chaste scares on the hotel’s flat screen. Sasha“Da-ad!”s me into muting the NBC affiliate’s segmenton our Detroit campaign stop. I don’t need soundto know the hope my image labours to radiate:“One hundred years ago this very day, in this greatcity, hardworking Americans like you built the firstModel T. The prodigious Mr. Henry Ford called itthe car ‘for the great multitude.’ What we needto build together today, with the same fearlessnessand determination, is a better America for us all,the still great multitude.” Even a glimpseof the blueprints my image pretends to possesswould help me sleep, or a glance at Ford’s ancient plans.Was it from ruins or raw material that he fashionednew parts? Did he invent a new vehicle for the peopleor from his creation were a new people cast? (“Detroit City Meets the Invisible Hand”)

Each poem is composed through a very distinct “voice” and for a particular purpose, including “Ballad composed on the occasion of the founding of the First Church of the Free Follower Fellowship,” “Composed by T.S. Eliot in April of 1926 on the occasion of the fifth anniversary of the first War of Art victory by ‘The Waste Land,’” “Sestinaiku composed on the occasion of the seventieth anniversary of the Enola Gay’s refusal to drop an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan” and “Recorded by war activist John Lennon in protest of the seventy-five years of involuntary global peace imposed at the end of the Great War.” Utilizing historical facts and figures, Tysdal’s deliberate twists and shifts in composing poems for occasions that, for the most part, could never have existed, is a curious set of “what ifs,” writing out the possibilities had a particular point in history turned one way, say, instead of another. His use of “voice” (composing poems that claim composition by another) is reminiscent, also, of some of the work by Ottawa poet Stephen Brockwell [see my recent interview with him in Jacket2 here], whether in his most recent collection,

Complete Surprising Fragments of Improbable Books

(Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2013) [see my review of such here] or his prior collection, The Real Made Up (Toronto ON: ECW Press, 2007). One might wonder what Tysdal is exploring through such faux occasions and historical fictions, but for what the best of speculative fiction writers could ever hope to articulate: a way to see through into the present with fresh, critical eyes.

Each poem is composed through a very distinct “voice” and for a particular purpose, including “Ballad composed on the occasion of the founding of the First Church of the Free Follower Fellowship,” “Composed by T.S. Eliot in April of 1926 on the occasion of the fifth anniversary of the first War of Art victory by ‘The Waste Land,’” “Sestinaiku composed on the occasion of the seventieth anniversary of the Enola Gay’s refusal to drop an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan” and “Recorded by war activist John Lennon in protest of the seventy-five years of involuntary global peace imposed at the end of the Great War.” Utilizing historical facts and figures, Tysdal’s deliberate twists and shifts in composing poems for occasions that, for the most part, could never have existed, is a curious set of “what ifs,” writing out the possibilities had a particular point in history turned one way, say, instead of another. His use of “voice” (composing poems that claim composition by another) is reminiscent, also, of some of the work by Ottawa poet Stephen Brockwell [see my recent interview with him in Jacket2 here], whether in his most recent collection,

Complete Surprising Fragments of Improbable Books

(Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2013) [see my review of such here] or his prior collection, The Real Made Up (Toronto ON: ECW Press, 2007). One might wonder what Tysdal is exploring through such faux occasions and historical fictions, but for what the best of speculative fiction writers could ever hope to articulate: a way to see through into the present with fresh, critical eyes. There is something quite charming in the way that Tysdal composes his speculative fictions, even through his notes at the end of the collection that continue to perpetuate his created facts. There is almost a sense of Tysdal exploring history, just as much as poetic form, through his speculations of it. As he writes:

“Shell”: This poem is often misread as a response to the assassination of Jacqueline Kennedy. However, such a reading is not possible. “Shell” was composed a full year before November 22, 1963, and published four months before that tragic day. Not surprisingly, conspiracy-minded critics have read “Shell” as Munroe’s attempt to warn Jackie of her impending assassination, a plan Munroe knew about, these critics argue, due to her mob connections.

Published on September 25, 2015 05:31

September 24, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Carrie Hunter

Carrie Hunter received her MFA/MA in the Poetics program at New College of California, edits the chapbook press, ypolita press, is on the editorial board of Black Radish Books, and co-curates the Hearts Desire reading series. Her latest chapbooks were with Little Red Leaves Textile Editions and Dancing Girl Press. She has two full-length collections, both from Black Radish Books,

The Incompossible

, and

Orphan Machines

. She lives in San Francisco.

Carrie Hunter received her MFA/MA in the Poetics program at New College of California, edits the chapbook press, ypolita press, is on the editorial board of Black Radish Books, and co-curates the Hearts Desire reading series. Her latest chapbooks were with Little Red Leaves Textile Editions and Dancing Girl Press. She has two full-length collections, both from Black Radish Books,

The Incompossible

, and

Orphan Machines

. She lives in San Francisco.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?My first book that I didn’t self-publish was a chapbook published by Mark Lamoureux’s Cy Gist Press, in 2007. Vorticells. I’m not sure if it changed my life, but it allowed entrance into publishing, which seemed impossible at the time.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?I was always a reader, but never a writer, until a friend in high school introduced me to the idea of writing poetry, and I’ve never stopped.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?Starting is easy. I have millions of ideas all the time. It is finishing that is hard. And editing. Every project is different. My first full-length book’s form did not change. It started out as prose poems and ended much the same. The current new book Orphan Machines, started out as a rebellion from that form, takes four different forms in all, with a desire for variety and multiplicity, and a Guattari-Deleuzian “flow.” The format changed from being 3 big sections to being 12 sections with multiple mini-sections. The title also varied from starting as Anti-Oedipus, to being Anti-Oedipus’s Daughter, to being the current title.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?I do enjoy just sitting with paper or computer open, and seeing what happens, what will the poem bring, but over all I just love the project. I have a list of project ideas that just keeps growing and growing. I will never get to them all.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?I love doing readings, but don’t consider them to be too much of my creative process. Although the performance aspect can help you see what works and doesn’t work, writing for the performance is always the danger, and I want the text to supersede the performance, so I try to ignore that impulse. Although I do like to have a side project going that is entirely for the performance, as well.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?Theory for me is an entrance into poetry. I’ve never really felt much use for it on its own, although theoretical concepts are good to think about for themselves. But really, I just use it for my own devices. I mean there are philosophers who read philosophy for philosophy, and there are poets who read philosophy for poetry. I think both are valid, but I am the latter. I also do love residing in difficulty. I may or may not understand it, but I like being in that space.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?The Black Lives Matter movement has really helped me see the sometimes conscious, sometimes unconscious narcissism and privilege of white people writing poetry, and I’ve become more conscious of my own problems in addressing that. So how to turn away from that solipsism, and connected, the always romantic and pulling, hermitism. I think keeping oneself far away from problems up in your room writing does nothing, naturally, and probably harms by its lack of involvement. Thinking of “polite white supremacy” and all of its detriments. Of course, the Emily Dickinson mythology prevails and pulls, but I also think about the importance of acts of refusal, of refusing to engage in the dominant cultural milieus that include capitalism and white supremacy. I think often too of a refusal to publish as part of this, with a focus more on teaching and activism through that, but am not quite there. I am thinking more also as a curator and publisher, about how to maximize exposure to poets of color. (Send work!) ypolitapress@gmail.com; hearts.desire.series@gmail.com

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?I think it can be very cool indeed when someone helps you see outside of your vision, new eyes so to speak. But I also, after having taken 15 poetry writing workshops in my life, feel a bit done with too many outside eyes. It’s not essential but can be interesting. The problem is seeing your own vision too clearly that you can’t see outside of yourself, which an editor can help with.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?Take every opportunity offered. Even if it seems like it is not your thing, it can lead to other things and opportunities that may be. My abovementioned hermitism sometimes wants to retire and refuse, but that (I think) can often lead to stagnation.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?Every book seems to have its own routine. The Incompossible was written almost entirely on lunch breaks, and Orphan Machine was written largely on Sunday nights, to an ambient music radio program.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?I’m actually there right now. I have tons of writing ideas, that’s not the problem. The problem is its not pulling me anymore. Advice?

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?Menthol cigarettes.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?Music, art, theory, other literature, and lately teaching ESL.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?I used to say my strongest influences were, together, H.D. and Hejinian, in a sort of collage experimental lyricism, but my interests are moving more towards education than poetry these days. I’m thinking more along the lines of Paulo Freire, bell hooks, Cornel West, and Fred Moten.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?Write a book of non-fiction of some sort.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?Teaching. I love it.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?Typical childhood dysfunctional family where I had no voice.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?Just re-read H.D.’s Vale Ave, from New Directions, reissued as a chapbook. Also enjoying and working through Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s The Undercommons.

19 - What are you currently working on?My last two chapbooks (Scienza Nuova, Little Red Leaves, and Vice/Versa, dancing girl press) were two parts of a trilogy riffing off of Finnegan’s Wake. Working on part 3. Also doing a Tumblr poem (also a trilogy) that collages poetry quotes, Dante, literary criticism on Dante, impressions from poetry readings, stuff from my journal, stuff from thinking about yoga and spirituality, stuff from prose readings, grad school, and now teaching. (http://perunaselvaoscura.tumblr.com/ and http://percorrermiglioracque.tumblr.com). (The first is loosely connected to The Inferno, and the second to The Purgatorio.) Also have been working on another collage project that combines a bunch of even differentthings and different projects.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on September 24, 2015 05:31

September 23, 2015

The Collected Poems of Chika Sagawa, translated by Sawako Nakayasu

PLEASE COVER ME WITH DIRT EVERY YEAR

Listlessly walking silently,Clinging to the honeysuckle on the hedgeCrouched beside the roadO, decrepit old winter – The hair on your head has driedAnd those who walked upon itHave died too, along with their memories

The Collected Poems of Chika Sagawa , translated by Sawako Nakayasu (Canarium Books, 2015) is the first comprehensive collection by Japanese poet Chika Sagawa (1911-1936) available in English translation. In a recent review of the book over at Heavy Feather Review, AK Afferez writes: “[T]his first comprehensive collection of Sagawa’s poems and prose—diary excerpts, notes and reviews, vignettes that read like prose poems—reveals a complex and assured voice, one in constant expansion, always seeking new poetics.” As Nakayasu opens her introduction:

Sagawa Chika was Japan’s first female Modernist poet, whose work resonated deeply with, and helped shape, the most dynamic shifts and developments in the poetry of the era. She was a singular and remarkably inventive poet who had developed a poetics influenced by French literary movements as they were imported to Japan, English and American Modernist writers whose work she translated, and contrasts between her nature-filled upbringing and cosmopolitan Tokyo. Despite her death in 1936 at the young age of 24, it is impossible to overstate the importance of her remarkable oeuvre, which was created in less than six years of poetic production during one of the greatest social and cultural shifts of her nation’s history.

In her lengthy introduction, Nakayasu, a remarkable poet in her own right [see my review of her most recent collection, The Ants, here], goes on to describe Sagawa’s career cut short through a number of factors, including her early death, being female in a male-dominated field, and the advent of the Second World War:

In her lengthy introduction, Nakayasu, a remarkable poet in her own right [see my review of her most recent collection, The Ants, here], goes on to describe Sagawa’s career cut short through a number of factors, including her early death, being female in a male-dominated field, and the advent of the Second World War:Chika’s early death, along with the effects of World War II, did not help her work find a strong foothold in literary history. For the writers who lived through the war, however, it created a special set of difficulties. In addition to the general strain that the war placed on everyone, an FBI-like organization called the Tokubetsu Kōtō Keisatsu, also known as the Shisō Keisatsu or “Thought Police,” had taken to arresting writers and intellectuals whose work was deemed unpatriotic. Poets were pressured by the government to prove their loyalty by writing patriotic verse.

Her introduction is essential reading, and provides a fascinating overview of Sagawa’s life and work, and the factors that led to her work being forgotten, and later rediscovered. At nearly one hundred and forty pages, the range of the collection is remarkable, even moreso when one considers it was created in the space of some six years, until the author’s death at twenty-four. This is a work of poems, journals, short prose pieces and diary entries by someone remarkably mature and curious, stretching out the possibilities and energies of youth into something contemplative and knowing. Her poems, stretching between the lyric and the prose poem, are meditative and incredibly immediate, and read as remarkably contemporary, articulating a relationship between nature and the body, the smallest and simplest examples of beauty, the possibility of failure and a shadow of death that runs across and through the entire collection:

FALLING OCEAN

A red riot takes place.

In the early evening the sun dies alongside the ocean. The waves are unable to catch the clothes that float away after them.

The ocean builds a blue road from the vicinity of my eyes. Countless gorgeous corpses are buried below it. Annihilation of a band of tired women. There is a boat that hurriedly covers its tracks.

There is nothing that lives there.

Published on September 23, 2015 05:31

September 22, 2015

an experiment : rob's patreon page,

I'm not sure if it might come to anything, but

I'm experimenting with a Patron page

; basically, a way for myself as a working artist to perhaps get closer to a living wage, in exchange for exclusive content, future chapbooks and books. We shall see. Apparently Amanda Palmer is doing quite well.

I'm not sure if it might come to anything, but

I'm experimenting with a Patron page

; basically, a way for myself as a working artist to perhaps get closer to a living wage, in exchange for exclusive content, future chapbooks and books. We shall see. Apparently Amanda Palmer is doing quite well.

Published on September 22, 2015 05:31

September 21, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jen Sookfong Lee

Jen Sookfong Lee

was born and raised in Vancouver’s East Side, where she now lives with her son. Her books include The Conjoined (forthcoming in Fall 2016),

The Better Mother

, a finalist for the City of Vancouver Book Award,

The End of East

, and Shelter, a novel for young adults. Her poetry, fiction and articles have appeared in a variety of magazines and anthologies, including Elle Canada, Hazlitt and Event. A popular radio personality, Jen was the voice behind CBC Radio One’s weekly writing column, Westcoast Words, for three years. She appears regularly as a contributor on The Next Chapter and is a frequent co-host of the Studio One Book Club. Jen teaches writing in the Continuing Studies departments at both Simon Fraser University and the University of British Columbia.

Jen Sookfong Lee

was born and raised in Vancouver’s East Side, where she now lives with her son. Her books include The Conjoined (forthcoming in Fall 2016),

The Better Mother

, a finalist for the City of Vancouver Book Award,

The End of East

, and Shelter, a novel for young adults. Her poetry, fiction and articles have appeared in a variety of magazines and anthologies, including Elle Canada, Hazlitt and Event. A popular radio personality, Jen was the voice behind CBC Radio One’s weekly writing column, Westcoast Words, for three years. She appears regularly as a contributor on The Next Chapter and is a frequent co-host of the Studio One Book Club. Jen teaches writing in the Continuing Studies departments at both Simon Fraser University and the University of British Columbia.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book was a novel, The End of East, and it completely changed my life in all ways. I was exclusively a poet before, and The End of East was the first piece of fiction I had ever written, apart from school assignments. So, the development of that book rewired my brain. Also, its reception in the big bad world was really positive, which meant that I was suddenly A REAL WRITER, and being invited to festivals and being interviewed and drinking free wine. And it led to my secondary career in broadcasting.

The novel that will be published in 2016, The Conjoined, is so different from my other books, which were largely written around character and theme. The Conjoined is plot-based, and messes with the conventions of crime fiction. The writing of it was hugely freeing for me, because I think readers have come to expect a certain amount of sad lyricism from me, and this book is far more gritty and, let’s face it, gross. I’ve come to realize that I really enjoy grossing people out.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I actually came to fiction second, and started in poetry, and had a few things published in literary magazines before I started writing The End of East. Oddly, The End of East began its life as a long poem, but at some point, when the long poem was getting unwieldy, I made the decision to turn it into a novel. I was 24 at the time, and my youthful fearlessness had me convinced it would all be fine. And it was, but that novel took seven years.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

For novels, my first drafts take between six months to a year, which is probably an average amount of time. I do a fair amount of planning and initial research, but I do it concurrently, while I’m writing the first scenes. It’s important to me to have a sense of the tone of the book before I can really create an outline or make any notes at all. But I do need to plan and plan carefully, because I like to write toward a destination, and to have a sense of how the narrative should develop. This is not to say, of course, that the outlines don’t change as I discover new threads during the writing.

My first drafts are horror shows! They are so, so different from the final versions. I have a habit of tearing novels apart structurally and putting them back together again, which is a process that feels really essential to me. Each book contains an element that is consistent throughout the seven or eight drafts I usually write. The End of East kept one main character intact. The Better Mother’s narrative arc was set very early on. And the first chapters of The Conjoined haven’t changed at all.

All novels seem like they take forever to write. Come on now.

4 - Where does a work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

With the exception of my first novel, I always know what I’m writing before I start. My ideas are very genre-specific; I have novel ideas, or poetry ideas, or short fiction ideas, or cultural criticism ideas. Fiction ideas can come from anywhere—news stories, other art forms, something you overhear in a conversation. I’m never at a loss for ideas. But I often fail at the execution.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I don’t like the actual reading part. It’s more fun for me to be on a panel, or have a discussion on stage with other people or the audience. I like the performance aspect of it, but standing at a podium and reading from my books feels musty and creaky. I would rather make jokes and talk about writing.

Meeting people and being out in the world always fuels my creativity. I always say that my books would be the most boring things in the world if I wasn’t a social person. I am relentlessly social and an obnoxious ham, but this is how I observe humanity, and I keep those observations in my head for my next project.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

My umbrella goal is always to create a narrative that attempts to give shape to the mess of our lives. It’s a universal compulsion for all writers, I think. More specifically, I like to explore expectations, meaning the expectations we place on ourselves, or expectations that are placed on women and their bodies, or people of colour and their positions in majority culture, or those who live in poverty. All of my novels have been set in and around Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, which is very much a neighbourhood of density, both in terms of population and human experience. And it’s a neighbourhood that holds a lot of meaning for me personally. It’s where my family began their journey in Canada, and I am firmly committed to its health and the lives of its residents.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Sweet cracker sandwich, I have no idea! Writers are the ones who create stories and the world will always need stories, in evolving forms, of course. I suppose our job is to reflect humanity; we’re the ones who remind you of your past, and who give space to your experiences. And I think the main job for writers is to create narratives that resonate, that make readers feel less alone. A big reason I read books at all is so that I can have that aha moment. You know the one.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love editors. All of my editors have genuinely wanted to help make my books the best that they could possibly be. And that’s never a bad thing. I like to be challenged, and I like it when someone forces me to consider my choices.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

To expect nothing but celebrate everything. This should be tattooed on every writer’s arm.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (literary journalism to fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

It hasn’t been difficult. I used to work in magazines and small press publishing, so was always used to writing different things for different audiences. The key has always been to write something I deeply care about, whether it’s gender politics or pop culture or poems about dying relationships. I do think writing in different genres helps every genre you tackle, in the same way that playing more than one instrument will give you a better understanding of music in general.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Right now, I write at night, after my son has gone to bed. It’s exhausting, but that’s all the time I have! When he goes to school full-time, I’m very much looking forward to not living like a vampire. I work in bed, surrounded by books, while my dog snores beside me.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I just write through the pain. I’m a bulldozer like that. I always say that even if you write 2,000 words of garbage, if even one line or one idea is worth keeping, then your time was still well-spent.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Simmering chicken stock.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I’ve been influenced by photography specifically, partly because there have been so many brilliant photographers from Vancouver who have used the city’s idiosyncrasies to create images that are both intimate and epic. Fred Herzog has played a big role in both The End of East and The Better Mother, and I kept going back to Jeff Wall’s images over and over again during the writing of The Conjoined. Theodore Wan’s photographs have also highly influenced my writing,

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I was always a Canlit nerd and I love Margaret Laurence more than any other Canadian fiction writer. I find her books comforting, like a cushy armchair. The poems of John Thompson slay me every time I read them. Donna Tartt and Junot Diaz are my favourite contemporary fiction writers. And a friend of mine recently introduced me to Kim Addonizio’s poems and I think she very well might be my spirit animal.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would love to publish a poetry collection. After many years away from poems, I’ve been writing them again lately. And I love it.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I would really like to make pies. I have this idea that I should be driving a vintage truck and delivering pies to happy people. Because who doesn’t love pie?

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I don’t think I had a choice. I am tenacious as a writer and have never had a back-up plan. There is nothing else I can or should do.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book I read was Birdie by Tracey Lindberg. I don’t think I’ve seen a great film in years. Seriously. I have really bad taste in movies sometimes.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on finishing up the edits for The Conjoined, and I’m also writing a book about the Gus Van Sant film, My Own Private Idaho. And I’m chipping away at that elusive poetry collection.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on September 21, 2015 05:31

September 20, 2015

Sparks magazine (1977-1978): bibliography, and an interview

this interview was conducted over email from August to September 2015 as part of a project to document Ottawa literary publishing. see my bibiliography-in-progress of Ottawa literary publications, past and present here

The author of eight books, six of which are poetry, Ottawa writer Blaine Marchand’s most recent books are Aperature (poems, prose and photos of Afghanistan, 2008), and The Craving of Knives (2009), both of which were nominated for the Archibald Lampman Award for Poetry. A young adult novel, African Adventure (translated as Aventure africaine) was published in 1990. His work has been published in Canadian and American literary journals and forthcoming in Pakistan.

He was co-founder of Sparks , Anthos (1977- 1986), Ottawa Independent Writers (founded in 1986) and the Ottawa Valley Book Festival (1986-1997), and President of the League of Canadian Poets (1992-94.)

He is working on a new manuscript of short stories (entitled Nomads), two series of poetry (one on Pakistan and one on growing up in Ottawa) and on a work drawing upon his journal entries while living in Islamabad, Pakistan (August 2008-2010). He co-edited a collection of Pakistani poetry in English by 24 poets from Pakistan, the UK, US and Canada for Vallum Poetry Magazine , which appeared in the winter issue, 2012.

Q: What was the original impulse for starting Sparksmagazine, and how did you choose the format? I’ve heard say that Bywords (which began in 1990) was influenced in part by the monthly Poetry Toronto (which began in January 1976). Was Sparks a direct result of it as well?

Q: What was the original impulse for starting Sparksmagazine, and how did you choose the format? I’ve heard say that Bywords (which began in 1990) was influenced in part by the monthly Poetry Toronto (which began in January 1976). Was Sparks a direct result of it as well?A: Ottawa has always had a diverse and active poetry scene. The 60s and 70s were a time of an explosion in Canadian literature and poetry. Anchored by the two universities, which largely brought in ‘academic canon’ Canadian poets and held symposiums and colloquiums focusing on poets (such as Isabella Valancy Crawford), the local poetry scene was always remained very much grassroot. So coffeehouses (such as the original Le Hibou on Bank Street and then on Sussex, the Well on Laurier at King Edward), local galleries from Saw Gallery (in its various locations) to Wallacks held poetry readings. Even the NAC held poetry evenings in the early days of its mandate, one of which featured an evening of Duke Redbird. Local bookstores, such as Octopus and Books in Canada, also were willing to host readings.

Because of the two universities and the government, Ottawa has drawn students and employees who pursued poetry as a passion. In the 60s, the universities underwent a hiring spree that saw poets within their ranks – Christopher Levenson, Seymour Mayne, George Johnston, Robin Mathews, Robert Hogg, to name a few. Among the ranks of the civil servants were Arthur Stanley Bourinot, RAD Ford, Harry Howith, Grant Johnson. These poets followed in the tradition of the early civil servant poets Archibald Lampman, William Wilfred Campbell and Duncan Campbell Scott.

There was also an active Canadian Authors Association branch in Ottawa. Joan Finnigan was the most prominent member of the local chapter, with many others not well known but published by Ryerson Press. These included Lenore Pratt and Ruth E. Scharfe.

In addition, you had the burgeoning folk-poetry scene that included Bill Hawkins, Bruce Cockburn, David Whiffen, and Sandy Crawley to name a few.

At the grassroots level, poets from Toronto came to Ottawa to pursue livelihoods. These included Tim Dunn, Misao Dean, Robert Craig, Carolyn Grasser and David Freedman. Also among these was Jane Jordan White, who quickly set up a reading series at Pestalozzi College and whose readings often twinned a local poet and a national Canadian poet, believing that the national poet would draw and audience and give greater exposure to the local poet. She would also invite young poets from Toronto to read at her events.

These poets from Toronto kept referring to a new magazine in Toronto called Poetry Toronto, which not only published poems but had a calendar of events so that readers would have one central reference point to know what was happening across the city each month. This led to a group of Ottawa poets – Robert Craig, Kathryn Oakley and John (as he was then known) O’Neill and myself to attempt the same thing in Ottawa. In a meeting at my place, we began to plot the magazine, feeling it should feature local poets in addition to having a calendar. Publication of Sparksstarted in February 1977.

Throughout each month, the group would meet, review submissions and gather information about upcoming readings. All of this was typed up and taken to a local printer to do the layout and print 750 copies. These were then distributed to bookstores, the universities, libraries and handed out at readings. Response to the magazine was enthusiastic and submissions flowed in. Cost for the magazine was covered out of the pockets of the five poets, all of whom were then trying to establish careers and found the cost onerous.

In 1978, we approached the city for funding but they did not have the cultural funding they currently have. Then the editorial board decided to apply for Canada Council and Ontario Council Funding. Our requests were turned down as Sparks was deemed too local (and perhaps, unsaid, amateur). Our last issue was in 1978.

Q: I find it interesting what you say about the universities, given their presence has been all but invisible since I’ve been paying attention (I arrived in 1989). Amateur or not, the fact that Sparks was local was entirely the point, something that I think the Ottawa literary community has been grappling with for decades. What is it about Ottawa, in your mind, that causes so many to deny, refuse or flat-out dismiss the quantity and quality of the literary work occurring within our borders?

Q: I find it interesting what you say about the universities, given their presence has been all but invisible since I’ve been paying attention (I arrived in 1989). Amateur or not, the fact that Sparks was local was entirely the point, something that I think the Ottawa literary community has been grappling with for decades. What is it about Ottawa, in your mind, that causes so many to deny, refuse or flat-out dismiss the quantity and quality of the literary work occurring within our borders?A: This is an interesting question.

In fact, the tenure of the times has changed greatly since the 60s and 70s. Back then, even though the universities were always enclaves unto themselves, there was a great interest in the burgeoning Canadian literary scene. Ottawa U had a writer-in-residence program. Dorothy Livesay was one. Writers-in-residence draw younger or emerging poets and create a buzz.

The Ottawa Citizen had a good book page, under the editorship of Burt Heward. He was keenly interested in and supportive of local writers and the readings taking place. He was always willing to do profiles. Today, all we get is a few standard National Post reviews of books, rarely poetry, by authors, from elsewhere on a bland inconsequential page.

Yes, you are correct. Sparks was to assist with the Ottawa community. In looking at your bibliography, it made me realize that I had forgotten how, in the last months, we attempted to make it a bilingual publication, with the assistance of Evelyne Voldeng (a Carleton University French professor) so it would reflect more fully the bilingual nature of Ottawa.

More to your question, many decades ago, I did a reading in Toronto with short story/novelist André Alexis, whom as you might know, grew up in Ottawa. I asked him why he chose to go to Toronto rather than live in Ottawa. He told me point blank that he realized if he wanted to be a presence in the writing community, to make a name for himself, he had to be in Toronto as that is where the scene was. I often think about his comment. When I was young, I thought the key thing was the quality of the writing. While it is, other key factors are making connections, being mentored and gaining exposure, which is easier to do in other places.

Canada has several literary scenes – Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal (to a certain extent for the English side of it) and in the west, perhaps Winnipeg; in the east, perhaps Fredericton. But Edmonton seems to have emerged as a vibrant literary/poetry community, as I saw recently when I attended the Edmonton Poetry Festival. So, what makes one city more vibrant than the others? Consistency and longevity, I think.

Ottawa has always had a vibrant reading scene. That goes without question. But there has been a lot of start and stop. I have been guilty of that myself with the Ottawa Valley Book Festival, which was going great guns and then just petered out. Luckily, the new generation has VersFest, which is a welcome initiative. Literary mags start and stop. There was the aforementioned poet-in-residence at UofO (at Carleton, I think they thought of Chris Levenson as the poet-in-residence, which was an easy way out). On the other hand, Chris did have the Ottawa Poetry group, which brought along many of my generation’s poets, many of whom had come to Ottawa from elsewhere. (I am thinking of Colin Morton and John Barton.) There was the Ottawa poet laureate program, which went defunct after three poets (I think it was) and which Rod Pederson is now trying to revive. There was poetry on the bus program. Things start and do not last. With the exception of Arc and the Lampman Award, there seem to be no long-term consistency.

Why is this? Perhaps it has to do with the fact that there is really no “national” poet in Ottawa (by that I mean a poet whose name is known elsewhere) to lead the charge. Surely, David O’Meara, Shane Rhodes, Sandra Ridley, Monty Reid and yourself come close. And of course, there are John Akpata and Ikenna Onyegbula from the slam community. But as the saying goes, close only counts in horseshoes. Going back to Edmonton, one clearly sees the role that Alice Major plays in that writing scene there – Poet Laureate mentoring younger writers, starting the Edmonton Poetry Festival and then allowing others to take the helm so it could continue, continuing to play a role as a matriarch. This is what I think Ottawa lacks – someone around whom the poetry community can rally. Someone who speaks for or represents the community to the larger community. Perhaps, if the Poet Laureate is re-established, this will be a boon if that role is seen as being more than just writing occasional poems for city functions.

Why is this? Perhaps it has to do with the fact that there is really no “national” poet in Ottawa (by that I mean a poet whose name is known elsewhere) to lead the charge. Surely, David O’Meara, Shane Rhodes, Sandra Ridley, Monty Reid and yourself come close. And of course, there are John Akpata and Ikenna Onyegbula from the slam community. But as the saying goes, close only counts in horseshoes. Going back to Edmonton, one clearly sees the role that Alice Major plays in that writing scene there – Poet Laureate mentoring younger writers, starting the Edmonton Poetry Festival and then allowing others to take the helm so it could continue, continuing to play a role as a matriarch. This is what I think Ottawa lacks – someone around whom the poetry community can rally. Someone who speaks for or represents the community to the larger community. Perhaps, if the Poet Laureate is re-established, this will be a boon if that role is seen as being more than just writing occasional poems for city functions. There are also good and worthy small presses here, including your own, but none of them seems to have made a mark nationally, the way Coach House or Arsenal have. In a way, this causes poets to look elsewhere to be published. Again, publishing has changed so much since the boon years. There is less funding and even less for promotion of books and touring, so unless the poet is willing to reach into their own pockets to supplement what is available, little recognition of their work exists outside of the city. There are new poets competing for publication with older established poets for the few spaces. Perhaps my comments reflect my age and are generational and demonstrate I am not as in touch with the current poetry scene as I should be.

But, at the core, I think that Ottawa’s reputation as a grey city dominated by politics and civil servants colours how people see the city and its poets. People do not realize what excellent poets and what a diversified community exist here. Luckily, I feel, the poetry community itself is very supportive of its own and that in itself is a richness. It also means that there is not the divisiveness and factions among poets that one finds in other cities – those on the in and those on the out. But it does not somehow lead to Ottawa poets being recognized for the quality of their work.

Q: Despite the short tenure of the journal, you managed nearly twenty issues. What do you feel were the biggest accomplishments of the two years of Sparks?

A: There were two things I feel were real accomplishments in Sparks – the monthly listing of readings, which meant that in one place people could see all the activities going on; and secondly, one I had forgotten until I saw your Sparks bibliography, that we moved toward a bilingual edition that reflected the French and English communities in the city. (Same thing with the Ottawa Valley Book Festival/Festival de livres de l’Outouais, which tried to bring together the two poetry/literary communities.) I think perhaps we may have been ahead of our time.

Sparks bibliography:

Vol. 1, No. 1: March 1977. Eds. Robert Craig, Timothy Dunn, Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley, John O’Neill. Poems by Jane Jordan, Ellen Fawcett, Dorothy Livesay, Chas Macli.

Vol. 1, No. 2: April 1977. Eds. Robert Craig, Timothy Dunn, Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley, John O’Neill. Poems by Shelley Civikin, Phil Mader, Nancy Stegmayer, Patrick White.

Vol. 1, No. 3: May 1977. Eds. Robert Craig, Timothy Dunn, Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley, John O’Neill. Poems by Madeleine Dubé, Joy Kogawa, Pete Vainola.

Vol. 1, No. 4: June 1977. Eds. Robert Craig, Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley, John O’Neill. Poems by Victoria Wonnacott, Vi Archambault, Don Mattocks, Joyce Leclair. Interview with Joe Rosenblatt.

Vol. 1, No. 5: July 1977. Eds. Robert Craig, Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley, John O’Neill. Poems by Barry Baker, Joan Goudreau, Gordon Powers.

Vol. 1, No. 6: August 1977. Eds. Robert Craig, Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley, John O’Neill. Poems by Misao Dean, Rita Rosenfeld, Peter Vasdi, Patrick White.

Vol. 1, No. 7: September 1977. Eds. Robert Craig, Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley, John O’Neill. Poems by Steve Balkou, Tom Howe, Ray Jones. Interview with Milton Acorn.

Vol. 1, No. 8: October 1977. Eds. Robert Craig, Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley, John O’Neill. Poems by Rudi Aksim, Joan Goodreau, Robert MacDermid, Carol Tweedie. Interview with Christopher Levenson.

Vol. 1, No. 9: November 1977. Eds. Robert Craig, Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley, John O’Neill. Poems by Alexandre L. Amprimoz, Seymour Mayne, Rod McDonald. Interview with Seymour Mayne.

Vol. 1, No. 10: December 1977. Eds. Robert Craig, Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley, John O’Neill. Poems by Robert Craig, Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley, John O’Neill.

Vol. 1, No. 11: January 1978. Eds. not listed. Poems by Sharon Drache, David Gervais, William Hawkins, Frances Ilgunas, Christopher Levenson. Interview with William Hawkins. Article by Vi Archambault.

Vol. 2, No. 1: February 1978. Eds. Robert Craig, Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley, John O’Neill. Poems by Steve Harris, Chuck Macli, Patrick White. Interview with Louis Dudek.

Vol. 2, No. 2: March 1978 (mis-dated 1977). Eds. Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley, John O’Neill. Poems by M.W. Foley, Harry Howith. Interview with Harry Howith. Article by Chas. Macli.

Vol. 2, No. 3: April 1978. Eds. Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley. Poems by Cyril Dabydeen, Barry Demptster, David Freedman, Nancy Huggett, David Skyrie.

Vol. 2, No. 4: May 1978. Eds. Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley. Assoc. Ed. Chuck Macli. Redaction Francaise: Evelyne Voldeng. Ed. Assistant: Kathleen O’Doherty. Promotion Manager: Vi Archambault. Sales: John O’Farrell. Poems by Tim Dunn, Tom Howe, Max Meunier, Elaine Plummer.

Vol. 2, No. 5: June 1978. Eds. Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley. Assoc. Ed. Chuck Macli. Redaction Francaise: Evelyne Voldeng. Ed. Assistant: Kathleen O’Doherty. Promotion Manager: Vi Archambault. Sales: John O’Farrell. Poems by Marienne Bluger, Robert Boudreau, M.W. Foley, Madeleine Leblanc, David Skyrie. Review of With My One Hand Free by Steven Mayoff.

Vol. 2, No. 6-7: July-August 1978. Eds. Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley. Assoc. Ed. Chuck Macli. Redaction Francaise: Evelyne Voldeng. Ed. Assistant: Kathleen O’Doherty. Promotion Manager: Vi Archambault. Sales: John O’Farrell. Poems by Cyril Dabydeen, Marco Fraticelli, Albert M. Jabara, Judy McGillivary, Donald Officer, Jacques Rancourt (in French). Articles (in French) by Alvina Ruprecht and Evelyne Voldeng.

Vol. 2, No. 8: September 1978. Eds. Blaine Marchand, Kathryn Oakley. Assoc. Ed. Chuck Macli. Redaction Francaise: Evelyne Voldeng. Ed. Assistant: Kathleen O’Doherty. Promotion Manager: Vi Archambault. Sales: John O’Farrell. Poems by Pier Giorgio Di Cicco, Christine Lenoir-Arcand, Joël Désir, Patrick White. Articles by Seymour Mayne, Robin Mathews, “The Editors.”

Published on September 20, 2015 05:31

September 19, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Simeon Berry

Simeon Berry lives in Somerville, Massachusetts. He has been an Associate Editor for Ploughshares and received a Massachusetts Cultural Council Individual Artist Grant. His first book,

Ampersand Revisited

(Fence Books), won the 2013 National Poetry Series, and his second book,

Monograph

(University of Georgia Press), won the 2014 National Poetry Series.

Simeon Berry lives in Somerville, Massachusetts. He has been an Associate Editor for Ploughshares and received a Massachusetts Cultural Council Individual Artist Grant. His first book,

Ampersand Revisited

(Fence Books), won the 2013 National Poetry Series, and his second book,

Monograph

(University of Georgia Press), won the 2014 National Poetry Series.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Since my books were accepted, I feel like more strangers say they know my work, though I just could be imagining that. Before my first book was published, I found this very weird. I still have a difficult time believing that anyone reads poems by someone they don’t know and isn’t famous, though I myself do it all the time, of course. So I guess the books have made it easier for me to maintain the hallucination of feeling like an actual writer.

Having both these books come out in the same year is a little disorienting, since Ampersand Revisited is actually my third manuscript and Monograph is my seventh. I’m sure that this arbitrary publication order implies some kind of wildly incorrect evolutionary narrative, but that’s a champagne problem.

Ampersand is fairly ornate and has a pretty relentless argument, and Monograph is stripped-down and elliptical. Ampersand goes all the way across the page and Monograph is a string of small paragraphs that hang out in the middle, so spatially, they’re at opposite ends of the maximalist/minimalist spectrum, which makes me happy.

I find it funny that actors worry about being type-cast, but a lot of poets can’t seem to wait to do it to themselves by coming up with a unique brand and sticking with it until they die. My ambition is to write books that no one would be able to identify as mine in a blind taste-test based on the last book. This is probably a fruitless endeavor, but oh well.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I used to feel supremely underqualified to write fiction and non-fiction, in that I am congenitally unable to remember huge categories of facts: flowers, plants, trees, you name it. And my margin for chronological error before the twentieth century is plus or minus 80 years. (This is a big part of why I chose not to be an academic.)

However, I think I just wasn't thinking smartly enough about structure, persona, and argument in prose, and now creative non-fiction is very much a part of my writing life.

Poetry grabbed me because the bar seemed very, very low. In high school, I dated this very nice girl from Lowell, Massachusetts, who wrote poetry. She wasn’t an intellectual, but she knew what not to say and when to stop on the page, and it changed my life. Before that—despite having read T.S. Eliot and Sylvia Plath—I still thought poetry had to rhyme and be in meter.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I used to free-write all my first drafts, relying on speed to trick myself into a good image or line before I knew what I was doing. So all my poems had definite birth dates, like cans of beer.

All the individual poems I wrote before and during grad school either died or found themselves assimilated into the Borg-like inevitability of Ampersand Revisited. Now I only work on a book as a whole, rather than mess around with individual poems in isolation. I got tired of having to cut published poems that were simply redundant or tangential.

The initial shape of any poem is almost never the final one. I'll put a piece into 15 to 20 different shapes, trying to find one that has the perfect trade-off of clarity, organization, and musicality. Sometimes I’ll just futz around with them forever until the white space feels right. Or, as they say in the construction industry, abandon them in place, like a burned-out conduit behind dry-wall.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I went into grad school worshipping the short lyric and came out as someone who wrote long-ass things, having appropriated as much tech from fiction writers as I could. So my books are always a project now (whatever that means) because I find epic structures more rewarding and challenging than one-offs.

As for the origin of said projects, it’s often as much an ambition as an irritant. I wrote one book because Brian Teare challenged me to investigate the origin story of the femme fatale in my early work. I wrote one for Justin Petropoulos because of an argument we had about the compromising effects of audience, and I wrote another for Julia Story because I thought she might enjoy a good Midwestern gothic.

Every few years, I’ll NaPoWriMo for the core of a new manuscript (and then sometimes NaPoWriMo again to replace the 50% that I end up cutting), but it’s usually about six months before I can even stand to look at what I wrote and try to shape it into a book. Until that point, I sort of treat it like a toxic waste dump from an overheated nuclear reactor.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Reading to people who are probably sitting in uncomfortable chairs and resisting the urge to check their phones helps to remind me of the stakes. I feel like some poets think about the audience as an afterthought or like they’re civilians. But no one is putting a gun to people’s heads and forcing them to read poetry. Readings help me to remember that.

They also serve as a supplementary editing stage for me. If I read a poem and I want to skip a line or a section, the knives come out. Much like submitting to magazines, I find the prospect of the potential indifference of strangers to be very sobering. Any poems that can’t handle either of those stress tests get tossed out.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I know a lot of writers who are theory-driven and have a single-minded devotion to the experiment, but I find that merely trying not to repeat myself offers up plenty of problems to be solved. I try to make my next manuscript a whole new ecology, with life forms that are silicon-based, say, as opposed to carbon-based. There’s nothing more tiring to me than reading someone who feels a little bored by what they’re writing.

This has no relation whatsoever to my work, but I’ve been thinking about Conceptual Poetry a lot this past year, and I read someone very smart (I forget who—there were so many articles on Facebook and Twitter) who said that when you appropriate something, you have to pay it back with interest. Otherwise, it’s just theft. You’re trading on the power of the cultural material you’re quoting without having any responsibility to that material or being thoughtful in the piece itself about the implications of what you’re doing.

You can perform (as it were) those intentions off-line from the piece, but I find that to be a little like a terrible poem being read by a magnificent actor. The art lies elsewhere than on the page. If the justification required for the work is far more complex than the piece itself, then maybe it should be in the work. Otherwise, the work kind of devolves into a press release for the artist.

Looking back over the manuscripts I’ve written, I do see a preoccupation with gender construction and a generalized silence around sexuality, as well as the discontinuity between people's interior, Akashic mansions and the relative poverty of their speech.

There’s a pleasure in subversion which I think is still (and always will be) inadequately understood and under-implemented, so I’m mildly obsessed with the types of permission we both grant and withhold from ourselves.

I also find myself wrestling with how to negotiate confrontations with The Other, however you want to define that, which, of course, has only been going on since the Stone Age. My first two books have a strong thread of spiritual difference, which kinda makes me feel like Stephen Vincent Benét, what with his unfashionable patriotism and all.

Frankly, I’m more invested in how theoretical tensions are embedded in people and history. No anxieties but in things!

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Obviously, writers can speak in a timely fashion to issues that are causing turbulence at the culture at large. Just look at Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, Eula Biss’s On Immunity, and Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, which speak to the debates over police violence, the anti-vaccination movement, and transgender rights. And there’s stuff like Patricia Lockwood’s “Rape Joke” going viral on social media and being read by over 100,000 people or Richard Siken’s Crush selling 20,000 copies.

I think our ideas about culture (or race, gender, nationality, ethnicity, sex, etc.) are often woefully inadequate, and our relationship to history is tenuous and/or erroneous. The job of writers is to complicate and destabilize these fixed ideas. Sometimes that can be done by speaking very publicly and being inclusive of other people’s experiences, and sometimes that can be done very intimately and confessionally.

There’s this Arthur Miller quote I love: “Data is a lot like humans: It is born. Matures. Gets married to other data, divorced. Gets old. One thing that it doesn't do is die. It has to be killed.” I think writers need to take down bad cultural data. You can do that by looking at what memes society has given you and making them absurd, threatening, or irrelevant, or (conversely) investing them with a beauty, power, and meaning that was not intended by their makers.

I’m suspicious of writers who point a way forward, but I’m grateful to those who demonstrate that what I thought might be true simply isn’t workable, whether for me or for everyone.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love being edited. My favorite thing is when someone absolutely dismantles one of my poems in a concrete way. Then I can see what was making the fan belt underneath that stanza wonky. Certainly, taking a bunch of fiction workshops in undergrad helped me be less precious about my work.

As long as an editor can communicate what they like and don’t like in a piece effectively, I can get a sense of how their ear is working and where their strengths are, and I find that enormously helpful. I’ve always found revision to be the most gratifying part of the process anyway. That’s where you can get forgiveness for all your sins in the first draft.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

In the Oughts, when it seemed like all my contemporaries from grad school were getting their books taken and I was racking up the rejections, I got pretty dispirited, and Justin Petropoulos passed on this gem from Susan Briante: “It’s a marathon, not a sprint.”

She’s right. There are quite a few poets on my shelf who only published a book or two, and I read a lot of second books that feel like they were rushed into publication with imperfect structures or placeholder poems.

The pressure to publish seems at least partially responsible for this hurriedness, and I know that I have the luxury of being able to set my own timelines without worrying about tenure, but that doesn’t stop me from wishing the books were better.

At the time, it sucked, but I’m glad in retrospect to have had all that time in the wilderness to make the books the best they could be. Both Ampersand and Monograph didn’t find their final shapes until a year before they were accepted.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I have no writing routine whatsoever. In undergrad, I wrote almost exclusively after 10 pm, and I'm embarrassed to admit that I wrote my creative writing thesis entirely by candlelight. In grad school, I wrote whenever the computer lab was open, since my basement room had no air-conditioning and lots of spiders.

Since I got a real job, I write whenever I have a spare fifteen minutes. When I’m doing NaPoWriMo, I write a poem at 7 am and at 5 pm (if I’m doing 2 poems a day). I’ll go months without writing, and then I’ll spend weeks revising on the train into work, during lunch, on the train home, and until I go to bed. So my creative life is less orderly and more the equivalent of binge and purge.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I’ve found that I have to read poetry more or less constantly to believe in the whole endeavor. Otherwise, it starts to seem like riding a unicycle or knowing how to speak Esperanto. You begin to feel surplus to requirements, culturally speaking.

When I really need to jump start my enthusiasm, I find myself re-reading books like Jack Gilbert’s Monolithos, C.D. Wright’s Translations of the Bible Back Into Tongues, or Brenda Shaughnessy’s Interior with Sudden Joy.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

In order to get to my grandparent’s cottage in Connecticut on Long Island Sound, you had to drive through this huge salt marsh. I have incredibly vivid memories of being in the car on summer nights and feeling comforted when we hit the swamp and the smell of skunk cabbage and mud flooded through the windows, along with the thunderous sound of peepers. Basically, I grew up in a Lovecraft novel.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

My dad is a photographer, so I spent a lot of time in the darkroom hearing him talk about composition and light. My favorite thing as a kid was to go to the movies with him and debrief each other about our likes and dislikes later. After we saw A Midnight Clear, he gave me a journal entry on it. I’ve never forgotten how beautifully he wrote about its carefully controlled palette of white, grey, and brown; how this emphasized the gold accent of light on a pair of wire glasses and the red of a bloody cross on a sheet; how the movie gracefully lingered on a statue of a bishop with his head in its hands without ever having to tell us that this meant the bishop was wrongfully executed.

I have no doubt the DNA of these talks with him is all through my poems. It’s why I saw Saving Private Ryan and The Piano four times in the theater. The former because it made me cry and unable to form a coherent thought afterwards and I wanted to study my reactions. The latter because I wanted to break down the lyrical argument in the cinematography.

I always wanted to be a visual artist, but a pen-and-ink course in undergrad confirmed that I have all the sense of proportionality and symmetry of an addled sloth.

I love science and have jacked all kinds of great stuff from its diction. I feel like it’s a high risk-activity though, since a good portion of what’s cool at one time or another turns out to be false within 10 to 15 years. In undergrad I wrote a poem about the six flavors of quarks: up, down, strange, charm, top, and bottom. Now I fully expect to discover that there are 50 or more.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Douglas Adams’s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy blew my mind in fifth grade, and I did a low-rent version of him for many years. Similarly, my book club recently read Michael Chabon’s Wonder Boys, and one of them gave me possibly the best compliment I’ve ever received by noting how much they could hear my voice in the style. That book rearranged all my furniture.

Mary Oliver, Kenneth Patchen, and Yusef Komunyakaa taught me how to write an image, and Raymond Chandler and William Gibson showed me the wisdom of leaving enough space and silence to let an image breathe. I didn’t know how to think in poems before I read Larry Levis’s The Widening Spell of the Leaves, Brian Teare’s The Room Where I Was Born, and Anne Carson’s “The Glass Essay.” Likewise, I was far more of a dolorous bastard before I encountered Lynn Emanuel’s Then, Suddenly.

As far as intellectual positioning and identity, I remain awed by the courage of Eula Biss’s Notes from No Man’s Land and her way of raising questions about difference without seeming merely provocative, ducking the issues, or falling back on solipsism (i.e. despair). I also love Philip Levine’s non-fiction (especially his “Part of the Problem” essay) for the way it's vulnerable, frank, and combative all at the same time, as well as its ability to touch the third rail of the literary world—class—without being fried.

Finally, I owe a huge debt to Maggie Nelson’s Bluets for making me realize that I just don't give a fuck about whatever container writers put the content in, as long as it's good. Genre is bunk.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d love to learn sign language, go bungee-jumping, and take a train across the U.S. Before I die, I'd also like to visit Gaudi's cathedral, have a slice of Sacher-Torte in Vienna, and see every Vermeer in the world. (This last ambition is stolen from Thomas Harris.)

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

My day job is as a contracts person, which has given me the unexpected benefit of feeling like I'm contributing usefully to society. Believe me, no one's more surprised than I am that I ended up dealing in numbers and forms. Back in undergrad, I couldn't fill out a financial aid application without breaking into a cold sweat. Now I can warp time and space with complicated spreadsheets. Economic desperation gives you wings. I also wish that I could have succeeded as a painter, actor, or astrophysicist, but those were not in the cards.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I have a mania for detail—the more upsetting and weird, the better—but a terrible memory for things at the intersection of time and space: facts, dates, history, the harder aspects of how science works. In other words, I’m obsessive, but not usefully so.

I just don't function very well in a Cartesian universe. Once we hit calculus in high school math class, I knew I was fucked. I couldn't memorize the 21 identities without knowing why they were identities and where they came from. (I've never had a nightmare starring a differential equation, but I expect to someday.)

Failure is a big part of my writing career. I can be very performative and I tried acting, but I'm still an introvert. Being raised by a photographer instilled in me a love for the image, but I don't have an aptitude for visual problem solving. I love the diagrammatic nature of physics and science, but can't think mechanistically very well.

However, all those thwarted impulses harmonize when I'm making a poem and I need to find an urgent voice, populate a landscape, and make sure everything that's set in motion works well linguistically and dramatically. I love the absolute control that the page gives you—nothing is too past tense or beyond your reach if you have enough guts and thoughtfulness.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The best book of poems I’ve read recently was Cate Marvin’s Oracle. I love its bleakly hilarious tableaux and its chorus of dead girls. It's like a David Fincher movie starring Tilda Swinton on mushrooms with a Wes Anderson script and an Edward Gorey production design. Or maybe that's just me fantasizing.

As for prose, I loved Caitlin R. Kiernan’s The Drowning Girl, a piece of dark fiction about a schizophrenic painter in Providence being haunted by a contagion of ideas and historical facts. I’m a sucker for the New England Gothic, and Kiernan’s updating of it is masterful, a fugue of unreliable narration, unsettling lyricism, and gender fluidity.

The last great thing I saw was The Secret of Kells , this sweet and ominous fable about illuminated manuscripts and why you should always listen to girls with fantastic hair in the woods who tell you about wolves. I've never encountered another animated film where the physical movements of its characters were so unmistakably its politics. It's like someone decided to live in a world made of medieval mandalas. See it! Hear Brendon Gleeson be the best gruff monk!

19 - What are you currently working on?

I'm working on a memoir about comic books and literary gatekeeping. I found that I just can’t shut up about superhero comics around writers, especially when they furrow their brow and look confused, as if (to quote Douglas Adams) I had just asked them for a lightly-fried weasel on a sesame seed bun. The literary world seems chronically short of such weasels, so my hope is that writing this book will relieve me of this particular compulsion, or at least give me something heavy to hit them with when they look askance at me.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on September 19, 2015 05:31

September 18, 2015

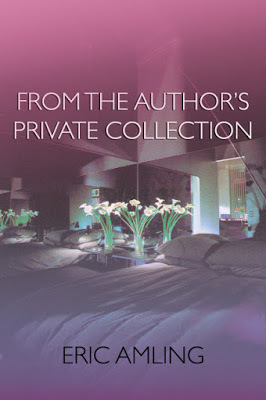

Eric Amling, From the Author’s Private Collection

Some lines I cut as the author of this book:

The Haitian poet Roumer admires an ass so spectacular

It is like a gorgeous basked brimming with fruits and meat

When I’m out walking I think of this

Rationing an individual thought

To my classified adulteries

I have to dig into a platform of reason

Create a pond in the land of misconduct

Though because of truth I have trouble with its reflections (“2010 – 2015”)

The poems that make up New York City poet and artist Eric Amling’s first trade collection, From the Author’s Private Collection (Birds, LLC: 2015), are constructed out of an accumulation of phrases, as each poem builds its slow and unexpected way towards something odd, even confusing, and bafflingly coherent. Writing on Amling’s visual art in the “Visual Interview: A Poetic Interlude with Eric Amling” at The Wild, Michael Valinsky refers to Amling as “a master collage-maker,” a description that could also refer to his poetry. “It’s hard to explain / My ghost writing / When I remained / An insular entity,” he writes, to open the eighteen-part sequence “Rare and Special Interests.” Amling’s poems might appear, at first, to be all over the place, but manage to include a multitude of directions while maintaining a coherent through-line; the mélange is simply how he travels from one point to another. One could compare his poems to the work of Calgary poet Natalie Simpson, who also works from a series of notes structured together in a series of collisions, specifically her

Thrum

(2014) [see my review of such here]. “How do you kill / A mountain of a man / But with a river of fries / Grass / Growing around the gurneys / Because the cancer patients / Are in hammocks,” he writes, further in the same extended poem. In poems that stretch, fragment and sequence, it is really in the collision of phrases and sentences that his pieces cohere, coming together from a near-chaos into something unique, connecting pockets of clarity and insight to form a broader spectrum of serious questions and observations on culture, morality, human interaction and the nature of art. As he writes to open the poem “Liquid Assets”: “The civic purposes of the museum, were not to be a ‘mere cabinet of curiosities which serve to kill time for the idle’ but instead ‘tend directly to humanize, to educate and refine a practical and labourious people.’ Given his main focus as a visual artist, it would seem his poetry exists both as a serious work that stands on its own merits as well as an extension of his visual practice, each medium allowing a potential insight into his work in the other. I would be curious to see how his practice continues.