Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 364

November 5, 2015

Reviewers on Reviewing: mclennan, Webb-Campbell, Marchand, Zomparelli + Del Bucchia

At Erin Wunker's request, I recently wrote a short blurb on why reviewing matters for the CWILA site, posted this week alongside similar pieces by Shannon Webb-Campbell, Philip Marchand, Jonathan Ball and Daniel Zomparelli and Dina Del Bucchia.

At Erin Wunker's request, I recently wrote a short blurb on why reviewing matters for the CWILA site, posted this week alongside similar pieces by Shannon Webb-Campbell, Philip Marchand, Jonathan Ball and Daniel Zomparelli and Dina Del Bucchia.As Wunker writes over at Facebook:

Reviewing as feral practice, as the strike-out and slow carve. Reviewing as necessary in a world where books seem to matter less and less. Reviewing as joyful dissent and a refusal to be 'boring as fuck.' Check out what Shannon Webb-Campbell, rob mclennan, Jonathan Ball, Daniel Zomparelli & Dina Del Bucchia, and Phillip Marchand have to say about why book reviews matter.

Have thoughts of your own? Send me a message and we can get your views on why you review up at CWILA's Reviewers on Reviewing site!

Published on November 05, 2015 05:31

November 4, 2015

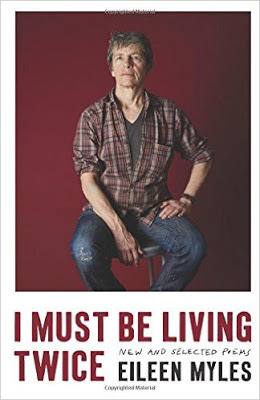

Eileen Myles, I Must Be Living Twice: New and Selected Poems

AUTUMN IN NEW YORK

It’s something like returning tosanity but returningto something I havenever known likea passionate leafturning greenAugust almost gone“—that’s my name,don’t wear it out.”As if I doffedmy hat & founda head orhad an ideathat was alwaysminebut just camehome, the balloonsare going by sofast. I lean onbuttons accidentallyjam the workswhen I simplyam thisgreen.

With the publication of

I Must Be Living Twice: New and Selected Poems 1975-2014

(Ecco, 2015), as well as the reissue of her 1994 novel, Chelsea Girls (Ecco, 2015), New York poet Eileen Myles is enjoying a bit of a renaissance lately. Not that she’s been silent for any extended stretch, having published “nineteen books of poetry, criticism, and fiction,” but, as she says to headline a recent interview in New Republic: “I’m the Weird Poet the Mainstream Is Starting to Accept.” Basically, Myles is a writer that other writers have known about for decades, finally, as the stories suggest, moving into a larger and broader readership. Much of Myles’ work explores the line between fiction and memoir, utilizing elements of personal detail, in varying degrees of alteration. Often more straightforward, and sometimes deceptively so, her poems engage with elements of narrative, the lyric, performance, meditation, social and political commentary, the confessional and the short story, all of which she presents as “the poem.” When reading through this collection, I can see very much how some of these poems would have fit perfectly being performed at the late lamented CBGBs, where her first readings were held in the 1970s. As the New Republic interview informs us: “Eileen Myles seems to come from a New York that no longer exists. Her first reading took place at CBGBs, she lived four floors below Blondie, and contemporaries with Richard Hell, progenitor of the spiky-haired, torn-suit jacket look.” That might all read as a tad romantic, and even sensational, but hers has been a New York also populated by Ted Berrigan, Alice Notley, Kathy Acker, Chris Kraus, John Ashberyand Charles Bernstein, among so many, many others. A recent interview over at Electric Lit (an interview worth reading in its entirety), explores her frustrations with accessibility and readability, the limitations of form, and the limitations of naming form:

With the publication of

I Must Be Living Twice: New and Selected Poems 1975-2014

(Ecco, 2015), as well as the reissue of her 1994 novel, Chelsea Girls (Ecco, 2015), New York poet Eileen Myles is enjoying a bit of a renaissance lately. Not that she’s been silent for any extended stretch, having published “nineteen books of poetry, criticism, and fiction,” but, as she says to headline a recent interview in New Republic: “I’m the Weird Poet the Mainstream Is Starting to Accept.” Basically, Myles is a writer that other writers have known about for decades, finally, as the stories suggest, moving into a larger and broader readership. Much of Myles’ work explores the line between fiction and memoir, utilizing elements of personal detail, in varying degrees of alteration. Often more straightforward, and sometimes deceptively so, her poems engage with elements of narrative, the lyric, performance, meditation, social and political commentary, the confessional and the short story, all of which she presents as “the poem.” When reading through this collection, I can see very much how some of these poems would have fit perfectly being performed at the late lamented CBGBs, where her first readings were held in the 1970s. As the New Republic interview informs us: “Eileen Myles seems to come from a New York that no longer exists. Her first reading took place at CBGBs, she lived four floors below Blondie, and contemporaries with Richard Hell, progenitor of the spiky-haired, torn-suit jacket look.” That might all read as a tad romantic, and even sensational, but hers has been a New York also populated by Ted Berrigan, Alice Notley, Kathy Acker, Chris Kraus, John Ashberyand Charles Bernstein, among so many, many others. A recent interview over at Electric Lit (an interview worth reading in its entirety), explores her frustrations with accessibility and readability, the limitations of form, and the limitations of naming form:Before I was really writing I lived in Cambridge with friends after college. One day I went to Dunkin’ Donuts for a cup of coffee and the guy next to me just turned and started unloading his mind completely. There was no civilized introduction, no nothing. He was completely crazy but what was really astonishing was how seamless it was. I try to kind of do that. The most interesting moment in The Bell Jar is when they take the famous poet out to lunch and he sits there quietly eating the salad with his fingers. The narrator concludes that if you act like it’s perfectly normal you can do almost anything. John Ashbery said he writes as if he’s in the same room as the person who’s reading the poem. For example, if I wanted to describe…well that wainscoting I’d just begin right there: “I’m not sure how i feel but the black next to it is actually really great.” What it creates is a feeling of intimacy, if a reader will go with it. A lot of fiction makes narrators that just happily give it up! They show all the scenery, the whole plodding entrance. I’d call them “obedient narrators”. I don’t ever want to write an obedient narrator. I want you to have an actual relationship with the narrator.

This is only the second title I’ve seen of hers, after the more recent Snowflake: new poems / different streets: newer poems (Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Poetry, 2012) [see my review of such here], but the poems in I Must Be Living Twice: New and Selected Poems allow the reader the possibility of seeing across four decades of her published poetry. Bookending the collection with “New Poems” and an “Epilogue,” the collection includes selections from The Irony on the Leash (1978), A Fresh Young Voice from the Plains(1981), Sappho’s Boat (1982), Not Me (1991), Maxfield Parrish (1995), School of Fish (1997), Skies (2001), On My Way (2001), Sorry, Tree (2007) and Snowflake / Different Streets (2012). What is curious is in seeing how the precision and rush of the pieces in the “New Poems” section are comparable to poems throughout her published work; Myles’ work has evolved, and honed over the decades, but the precision, energy and rush of her lyric, and the subtle shifts of tone and tenor of her lines, remains throughout. She knew what she was doing very early; she knew what she was doing, and pushed the boundaries while keeping her writing centred around an essential core of her narrative/meditative lyric.

WOO

out in a bus stopamong themountainsa yawn, boy drive byblue mountainslittle tan mountainhouse, similareach scapeis all its own placeno womanis like anyother

Still: given the heft of such a collection, at nearly four hundred pages, why not include an introduction? (I don’t understand any selected/collected poems that doesn’t include an introduction.) She does, at least, include a short essay-as-epilogue, an essay that works through considerations of narrative, genre and form; an essay that opens with her poem “What Tree Am I Waiting” and poet Dana Ward, who caught sight of it in the online journal Maggy, and offered praise:

His explanation of why my poem was important to him was like balm to my ears. He wrote:

To hear someone arrive with that purpose & then put it right there, getting out of the way of everything else to get it right to the top of the thought & the poem. That’s the best stuff in the world to me, that sound. It seems harder than ever to do, or I’m confused right now somehow, regardless, it just tolled in the room for me.

This was huge praise from someone whose work I currently adore. I was pee-shy too about my own poem in particular because it was too emotional. How will it be received. Dana did refer to his own piece in Maggy as “a poem” which intrigued me cause it looked like prose. It’s prose in a world in which I’ve never really noticed whether people describe Bernadette Mayer’sinfluential early works “Moving” and “Memory” as poetry or prose. Didn’t she call it writing. I mean I think even for Lydia Davis genre is like gender in the poetry world. I’m remembering Amber Hollibaugh explaining gender this way once. It’s not what you’re doing, it’s who you think you are when you’re doing what you’re doing. So prose writers in the poetry world always felt less like prose writers to us, more like fellow travellers and someone like Bernadette was probably writing poems that looked like prose, or like Lydia, prose in the poetry world which for a while at least adds up to the same thing. She was a fellow traveller for a time, and still is, truly, though she’s also everyone’s now. John Ashbery’s greatest book I think is Three Poems which certainly looks like prose. So if Dana Ward wants to call his prosey looking stuff a poem it probably has more to do with how he feels about the work. Or whose he thinks it is. When I read it, it’s mine for sure.

Published on November 04, 2015 05:31

November 3, 2015

new from above/ground press: Price, Christie + Touch the Donkey,

The Charm

The CharmJason Christie

$4

See link here for more information

Sickly

Katie L. Price

$4

See link here for more information

Touch the Donkey #7with new poems by Stan Rogal, Helen Hajnoczky, Kathryn MacLeod, Shannon Maguire, Sarah Mangold, Amish Trivedi and Suzanne Zelazo.

[keep an eye on the Touch the Donkey blog for upcoming interviews with a variety of contributors!]

$7

See link here for more information

and watch the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material;

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

October 2015

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

and don’t forget about the 2016 above/ground press subscriptions; still available!

To order, send cheques (add $1 for postage; outside Canada, add $2) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9 or paypal (above). Check the sidebar of the above/ground press blog to see various backlist titles (many, many things are still in print).

Review copies of any title (while supplies last) also available, upon request.

Published on November 03, 2015 05:31

November 2, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Anne Gorrick

Anne Gorrick [photo credit: Peter Genovese] is a poet and visual artist. She is the author of:

A’s Visuality

(BlazeVOX Books, Buffalo, NY, 2015),

I-Formation (Book 2)

(Shearsman Books, Bristol, UK, 2012),

I-Formation (Book 1)

(Shearsman, 2010), and

Kyotologic

(Shearsman, 2008). She has co-edited (with Sam Truitt) In|Filtration: An Anthology of Innovative Poetry from the Hudson River Valley (Station Hill Press, Barrytown, NY, 2015).

Anne Gorrick [photo credit: Peter Genovese] is a poet and visual artist. She is the author of:

A’s Visuality

(BlazeVOX Books, Buffalo, NY, 2015),

I-Formation (Book 2)

(Shearsman Books, Bristol, UK, 2012),

I-Formation (Book 1)

(Shearsman, 2010), and

Kyotologic

(Shearsman, 2008). She has co-edited (with Sam Truitt) In|Filtration: An Anthology of Innovative Poetry from the Hudson River Valley (Station Hill Press, Barrytown, NY, 2015). She has collaborated with artist Cynthia Winika to produce a limited edition artists’ book called “Swans, the ice,” she said with grants through the Women’s Studio Workshop in Rosendale, NY, and the New York Foundation for the Arts. She has also collaborated on large textual and/or visual projects with John Bloomberg-Rissman and Scott Helmes.

She curated the reading series, Cadmium Text ( www.cadmiumtextseries.blogspot.com ) and co-curated (with Lynn Behrendt), the electronic journal Peep/Show at www.peepshowpoetry.blogspot.com

Her visual art can be seen at: www.theropedanceraccompaniesherself.blogspot.com

Anne Gorrick lives in West Park, New York.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book taught me think in books. After Kyotologic came together with Shearsman in the UK, it got easier to think of my work as clustering, hivelike pieces. The real estate of a book, that possible space makes one less sensitive to limits. It also brought me out of almost total writing isolation.

The consecutive books so far aren’t exactly consecutively written. My second book has some of my earliest work in it, work that embraced a complex long form I keep playing with: to break numerous pieces apart and reattach them. It’s like Isis looking for parts of Osiris. That’s my poem-making.

My latest book, A’s Visuality, out from BlazeVOX, continues a formal and spacial poetic inquiry, and language might occasionally turn into paint. This book really attempts to sew together the textual and visual, and includes color plates of two of my artist’s books that ended up generating the first half of the book.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I’ve been writing poetry since I was a kid, not even really knowing what poetry was yet, but the scratch of the pen on paper was everything I ever wanted. Now it feels like poetry is my personal Hadron collider - I think up these extravagant ways to collect text, smash the particles together, and hope for some new thing I never knew before. There’s the sense that when I do this, that language is coming to tell me something, what it knows. Lately, my work is getting more sentence-y, so who’s to say it doesn’t at some point morph into fiction. Diana Vreeland, when asked if her stories were fact or fiction, said they were “faction.” Not sure where the line is between poetry and fiction. Now I’m thinking hard about the word “depiction.”

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I’ve always had to work pretty fast, because I don’t have a huge luxury of time. Think: working full-time in educational administration; serving as President of Century House Historical Society and its Widow Jane Mine; being married to a lovely being; that on top of my art/writing life. Usually a writing project becomes apparent pretty quickly - an inquiry will turn vast. I’ll find a way of searching, noticing, manipulating text in such a way that I don’t want to stop until I’ve used it up. I’ll often have elaborate worksheets of source text that I create at the beginning, but then the poem jumps out of it pretty quickly to me. I liked frayed edges, deckles, so I don’t overwork things. It bugs me when things are too smooth.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I can see a book now pretty early on (i.e. some technique I want to explore until I’m done). I’ve completed a manuscript of poems about perfumes that combine various poetic manipulations into one work, instead of keeping processes separate. This seems like a huge leap in my own poetic, generative process, due partly to a collaboration and friendship with poet John Bloomberg-Rissman. Anything goes with John, so this was a great teaching for me. “Scorn nothing,” John would say and attribute this to poet Robert Kelly.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I had to learn how to give readings, and now I enjoy them. I curated a reading series called Cadmium Text for seven years. I like readings as a forum to test drive new work, hear what my friends are doing, hopefully hear something that blows me away. I’m half-introvert, so I have to push myself sometimes out the door to engage.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

The cartoon idea of quantum physics, that particles can be many things at once, in many places at once, strikes me as something to strive for: a quantum poetics. That language can mean and dart multiply. The internet has primed us to be more associative, more able to make thought leaps easily. We live in a time more complex than our language is capable of holding. Can language be made more pliable, more plastic to better suit our world? It’s almost a moral quest: to mean in many directions, and to mean complexly.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

My practice is almost one of finding sites of ruin porn - to play with the shambles left to us, a parking garage made out of a theatrical palace. A reviewer in the UK said that my first book was more like graffiti on palace walls. I took this as such a compliment. I wrote a poem once that said “This is a poem for a small and skeptical audience / It’s about vajazzling AND Paul Celan“ I want the high and low world in my work. All of it. Vajazzling AND Paul Celan. To put the world in. Poetry is our Hadron collider - we can find the tiny particles that compose our culture, find new ways to mean multiply at once.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It’s always been interesting. I don’t find that people want to change my work too often, but I’m usually curious and interested to see other ways forward. I might not adopt that direction, but it’s fascinating, and I appreciate being read deeply.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I’ve always cherished a letter that Ted Hughes sent to Anne Sexton in regard to listening to critics and reviews: “They tend to confirm one in one’s own conceit—unless they praise what you yourself don’t like. Also, they make you self-conscious about your virtues. Also, they create an underground opposition: applause is the beginning of abuse. Also, they deprive you of your own anarchic liberties—by electing you into the government. Also, they separate you from your devil, which hates being observed, and only works happily incognito.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to visual art)? What do you see as the appeal?

I’m lucky to have a pretty broad creative continuum, mostly shuttling between writing, visual art, gardening and now perfume and its making. If I get sick of one thing, I can always go do something else. Even if it’s tedious. Digging holes for 20 Rose of Sharon bushes is pretty boring, but also an investment in future beauty. Or digging holes for 150 peonies.

Many years ago, I threw poetry out of the house like a bad boyfriend, yelling at it from upstairs windows and chucking its clothes on the lawn. I was tired of poetry’s limit to a 8 ½” x 11” page. So damn tired of it. I broke up with poetry and I started to learn traditional Japanese papermaking, printmaking, indigo dyeing and encaustic painting. It helped break through the ice dam of the traditional page and let me range over larger spaces. Of course poetry came crawling back, apologizing. And I took it back into my house.

My last visual art project was a series of 30+ encaustic monotypes, worked over in pastel based on deceptively simple photographs of Luis Barragán’s architecture. His work is so spare and lush at the same time. I’m a maximalist, so it’s fun to lay in the sun of his opposite light.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

From 2008 until 2014, I got a lot of work done. I could spend up to three days a week at my writing/visual practice, from a few hours to much more if I felt like it. It was good to write in the morning. My life is different now. Less time, new job, a recently herniated disc in my neck that makes sitting for long periods difficult. Finishing my latest book used up some bandwidth, as well as completing the editing with poet Sam Truitt for our new book In|Filtration: An Anthology of Innovative Poetry from the Hudson River Valley, due out this summer from Station Hill Press.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Since 2010, I’ve kept a notebook of poem ideas, fun things to search and make poems, notes, diagrams. Anytime I’m stuck, I can turn to it because the book grows faster than I can write. I also have some long term projects that I can turn to and pick up the thread when I’m stalled.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Great question because I’m crazy for perfumes! The smell of the ocean reminds me of lost home (At the Beach 1966 by CB I Hate Perfume). My house smells like the grassy paws of a dog (Grass by CB I Hate Perfume), woodstove smoke (Burning Barbershop by D.S. & Durga), flowers I drag in (Carnal Flower by Frederic Malle), wet dirt (Black March by CB I Hate Perfume), firewood (Cambodian oudh), snow that gets stuck in boots (yes, snow has a smell). My husband builds and restores old race cars, so he’s got this terrific motor oil, exhaust thing I love. That’s true home.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yes, everything we pour into ourselves becomes food for the work. That’s why I’m sort of careful about what I pour in. Not a lot of junk food anymore. I hike. I read a ton of non-fiction. I make visual art.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

To write, I need to move. Until recently I studied tennis and played it seriously, this beautiful physical chess. Now I hike and bike. Writing is very physical to me, and I need to be able to do it.

Sooooooo many writers have filled my head. A very partial list might include Nabokov early on. The Situationists. Dada (Tristan Tzara was my first poetic love). The Pillow Book of Sei Shonogon . Susan Howe. Robert Kelly. Carole Maso. Anchee Min. Leslie Scalapino. Laura Moriarty (both - the painter and the poet). Work by friends over the years like: Maryrose Larkin, Elizabeth Bryant, Geof Huth, Nancy Frye Huth, Lynn Behrendt, Teresa Genovese, Cynthia Winika, Scott Helmes, John Bloomberg-Rissman, Reb Livingston, Michael Ruby, Sam Truitt, Lori Anderson Moseman…

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

It’s fun to dream aloud, if aloud is a lit screen.

I’m undertraveled. I’d like to walk the Camino de Santiago. I’d like to visit Grasse. The burial mounds of Ohio. India!

Writing-wise, I’ve got several long projects that are somewhere on the continuum of complete: a long work on the American desert, a project working with an essay by John Burroughs (my dead neighbor), a project writing into an unpublished manuscript by Eileen Tabios.

There are some encaustic teachers I’d like to study with.

I’d like to make a film. It might have snow and people wrapped in saran wrap.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Poetry isn’t an occupation for me. As far as I can tell, it isn’t really an occupation for anyone. Although I’d love to live in a world where I could afford to do it all the time.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It was inevitable. I never got to choose.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus by Charles C. Mann and La Grande Bellezza.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I spent the summer finishing edits on a few of manuscripts that were 90% done. I will co-curate with poet Melanie Klein a new reading series in 2015-2016 called Process to Text, which will bring adventurous writing to beginning poets at the local college where I work. There’s a long manuscript I pick up and put down where I’m writing into work by Eileen Tabios. Trying to heal up my back issues, but I see now this will take a long time. Started studying qigong, which seems to be helping. There are some ashes right now. I’m injured and curious to see what happens next.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on November 02, 2015 05:31

November 1, 2015

Cole Swensen, LANDSCAPES ON A TRAIN

Green. Cut. And I count: the green of the lake the green of the sky and the field

Which is green and breaking. Waking out of an opening, a sudden field opens

Out with a suddenness that instantly places us miles away across a field of wheat.

The publicity for American poet, editor and translator Cole Swensen’s LANDSCAPES ON A TRAIN (New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2015) reads:

Influenced by the history of landscape painting, Cole Swensen’s new book is an experiment in seriality, in the different approach and scope that language must take to record the way that fluctuations of minutiae transform a whole. These poems meditate on what it is simply to look at the world, without judgment, without intervention, without appropriation. Swensen’s lyric observations, lilting and delicate, distill the act of seeing.

The author of more than a dozen poetry collections, Swensen has long favoured constructing poetry collections around a central theme or thesis, from hands to gardens to ghosts. What might have been explored through a more expansive detail in previous works, Swensen’s touch across the poems of LANDSCAPES ON A TRAIN display a lighter touch. One might suggest that this is less a book about capturing the shifting views of landscapes than about describing the interplay of light across a screen, canvas or window. Through her lines, light shifts, shimmers and alters, refusing to remain static.

An extended meditation constructed out of fifty-eight untitled, unnumbered prose-poems, each accumulated section of

LANDSCAPES ON A TRAIN

suggest a series of quick notes composed during travel, capturing the details of landscape in the smallest brushstrokes, and held together to build into an essay on landscape and light around landscape painting during the Romantic (and even late Medieval) period.

An extended meditation constructed out of fifty-eight untitled, unnumbered prose-poems, each accumulated section of

LANDSCAPES ON A TRAIN

suggest a series of quick notes composed during travel, capturing the details of landscape in the smallest brushstrokes, and held together to build into an essay on landscape and light around landscape painting during the Romantic (and even late Medieval) period.Light slices across the tops of trees. White light cuts the presence back. The lack

Thereof. Light replaced. Light that is an approach. That we can’t see the light enter

The cells of the trees, not what leads, the path down to the cells below the trees.

This collection is slightly reminiscent of another of her ekphrastic works, her Such Rich Hour (University of Iowa, 2001), which wrote around a fifteenth-century book of hours, the Trés Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. As she wrote in her “Introduction” to that collection:

The poems that follow begin as a response to this manuscript, and specifically to the calendar section that opens this and all traditional books of hours. The calendar lists the principal saints’ days and other important religious holidays of the medieval year in a given region. In keeping with the cyclical rhythm of a calendar, the poems follow the sequence of days and months and not necessarily that of years.

Poems titled the first of a given month bear a relation to the Trés Riches Heures calendar illustration for that month, though they are not dependent upon it. Rather, they – like all the pieces here – soon diverge from their source and simply wander the century. And finally, they are simply collections of words, each of which begins and ends on the page itself.

Swensen seems very drawn to exploring human responses to the world, whether the Victorian-era development of the garden, medieval sketches of the human hand, ghost stories around an English village or, in this current work, the Romantic period of landscape portraits: each consideration depicting a response to and removal from the original subject. It is not the subject she is attracted to, but how those particular subjects are seen, understood and described. As she writes further on in the collection, “The unfurled sight of empty paths.” She discusses her approach to subject with Andy Fitch in a recent interview:

Andy Fitch: Could we first contextualize Gravesend amid a sequence of your research-based collections? Ours , for example, comes to mind. What draws you to book-length projects, and do you consider them serialized installments of some broader, intertextual inquiry? Does the significance of each text change when placed beside the others? Or do they seem discrete and self-contained?

Cole Swensen: They revolve around separate topics, yet address the same social questions: How do we constitute our view of the world (which, of course, in turn constitutes that world), and how does the world thus constituted impinge upon others? Ours examines an era in which science put pressure on definitions of nature. We cannot pinpoint when such pressures started, but 17th-century Baroque gardens give us a chance to focus on this pressure and question the accuracy and efficacy of making a distinction between science and nature in the first place.

[Skype glitch]

In short, both books question how we see, and how this shapes the world we perceive. Ours examines 16th– and 17th-century notions of perspective in relation to conceptions of scientific precision, knowledge, beauty and possibility in Western Europe. Gravesend poses quite different questions, foregrounding that which we do not, or cannot, or will not see. Certain passages address this directly, such as “Ghosts appear in place of whatever a given people will not face.” Communal guilt and communal grief remain difficult to acknowledge because our own lines of complicity often get obscured. Perhaps our inability to deal directly with such guilt and grief causes them to manifest in indirect forms. The English town of Gravesend offered a site through which to examine this because it can be read as emblematic of European imperialist expansion—a single port through which thousands of people emigrated, scattering across the world, creating ghosts by killing cultural practices, individuals, and in some cases, whole peoples. But the word “Gravesend” also hints at an after-life, a life that exceeds itself. The town of Gravesend stands at the mouth of the Thames. When people sailed out of it, they cut off one life and began another. So the concept of a grave as a swinging door seemed crystallized by the history and name of this town. And ironically, the first Native American to visit Europe, i.e., to have gone willingly (even before Columbus, many had been kidnapped and brought back to Europe, but), the first who seems to have regarded it as a “visit,” died in Gravesend, as she waited for a ship to take her back to Virginia. The New World, the Western hemisphere, finally capitulates to Europe, and dies of it.

Published on November 01, 2015 05:31

October 31, 2015

A short profile on The Peter F. Yacht Club

My short profile on

The Peter F. Yacht Club

(an irregular publication through above/ground press) is now online at Open Book: Ontario, with input from Laurie Anne Fuhr, Anita Dolman, Vivian Vavassis, Peter Norman, Amanda Earl, Peter Richardson, Wes Smiderle, Janice Tokar, Pearl Pirie, Cameron Anstee, Ben Edgar Ladouceur and Marilyn Irwin.

My short profile on

The Peter F. Yacht Club

(an irregular publication through above/ground press) is now online at Open Book: Ontario, with input from Laurie Anne Fuhr, Anita Dolman, Vivian Vavassis, Peter Norman, Amanda Earl, Peter Richardson, Wes Smiderle, Janice Tokar, Pearl Pirie, Cameron Anstee, Ben Edgar Ladouceur and Marilyn Irwin.

Published on October 31, 2015 05:31

October 30, 2015

a new poem up at our teeth

Published on October 30, 2015 05:31

October 29, 2015

Chaudiere Books Fall Poetry Launch! Weaver, Londry, Turnbull + Hawkins; November 28, 2015 at The Manx

The Writers Festival is pleased to be hosting a special Fall launch for Ottawa’s own Chaudiere Books!

The Writers Festival is pleased to be hosting a special Fall launch for Ottawa’s own Chaudiere Books!

Co-publishers rob mclennan and Christine McNair, have another great slate of books coming your way! Join us for readings and launches by Andy Weaver ( this ), Chris Turnbull ( continua ), Jennifer Londry ( Tatterdemalion ) and William Hawkins ( The Collected Poems of William Hawkins ).

Published on October 29, 2015 05:31

October 28, 2015

Joseph Massey, Illocality

POLAR LOW

Half-sheathed in icea yellow double-wide trailer

mirrors the inarticulate morning.The amnesiac sun.

And nothing elseto contrast these variations of white

and thicketchoked by thicket

in thin piles that dim the perimeter.

Every other nounfreezes over.

On the heels of his California trilogy comes American poet Joseph Massey’s fourth poetry title, Illocality (Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2015). His previous collection, To Keep Time (Richmond CA: Omnidawn, 2014) [see my review of such here], was the “third and final book grounded in the landscape and weather of coastal Humboldt County, California, and contains the last poems I wrote there before moving to the Pioneer Valley of Massachusetts in the winter of 2013.” As the press release for this new title informs: “Joseph Massey composed Illocality in his first year in Western Massachusetts. Massey’s austere landscapes channel the quiet shock, euphoria, and introspection that come with reorientation to place.” Illocality is a sequence of exploratory moments composed in short bursts, as Massey attempts to locate himself in the physical and philosophical spaces that make up his new geography, although one that seems devoid of human interaction.

The world is realin its absence of a world. (“TAKE PLACE”)

His short, precise lines echo William Carlos Williams and Robert Creeley, but place themselves in entirely different ways: the physical shapes of his immediate physical environment. And Pioneer Valley (especially during the winter) is very different than Humboldt County, California. As he writes in the poem “PARSE”: “This rift valley // A volley of / seasonal beacons // Window / where mind // finds orbit [.]” Where Williams and Creeley included the domestic and other other human interactions in their precise explorations (that included geography and the physical landscape), Massey’s poems allow for the suggestion of human presence without any kind of direct interaction. Where are all the people in Pioneer Valley?

His short, precise lines echo William Carlos Williams and Robert Creeley, but place themselves in entirely different ways: the physical shapes of his immediate physical environment. And Pioneer Valley (especially during the winter) is very different than Humboldt County, California. As he writes in the poem “PARSE”: “This rift valley // A volley of / seasonal beacons // Window / where mind // finds orbit [.]” Where Williams and Creeley included the domestic and other other human interactions in their precise explorations (that included geography and the physical landscape), Massey’s poems allow for the suggestion of human presence without any kind of direct interaction. Where are all the people in Pioneer Valley?ROUTE 31

Yellow centerlinesplit with roadkill.

First day of summer—I’ve got my omen—

the clouds are hollow, rovingabove a parking lot.

Each strip-mall pennant blurred.

So much metalshoving sun

the sun shoves back.

Massey’s invocations of the natural world are often in parallel, or even in conflict, with the human world: “the sun shoves back.” His is an uneasy balance between the two. Logics of the natural and human elements of the geography collide, and become illogical, creating their own set of standards, logics and rules, all of which he attempts to track, question and even disentangle. As he writes in the extended sequence “TAKE PLACE”:

As if a field guidecould preventthe present

from disintegratingaround us.

Published on October 28, 2015 05:31

October 27, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Colin Smith

Colin Smith’s second book of poems is

8x8x7

(San Francisco: Krupskaya, 2008). Latest is

Multiple Bippies

(North Vancouver: CUE Books, 2014), a republishing of two out-of-print titles, plus some uncollected prose yapping about poetry.

Colin Smith’s second book of poems is

8x8x7

(San Francisco: Krupskaya, 2008). Latest is

Multiple Bippies

(North Vancouver: CUE Books, 2014), a republishing of two out-of-print titles, plus some uncollected prose yapping about poetry. He lives in Winnipeg.

1. How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?It — Multiple Poses, Vancouver: Tsunami Editions, 1997 (though not actually emerged until spring ’98; long out of print) — mostly or merely convinced me I wasn’t a complete lame-ass at this poetry stuff. That book represents ten years of destroying previous work, generating anew, rethinking refeeling regrowing toward a different, Language-based poetics. Which was preceded by fifteen years of being a very prolific, substantively meagre Lyric poet with a poor ear and a snide sense of humour.

Now the ear is cacophonous and the humour’s deliberately vile!

Recent work — Carbonated Bippies!, Vancouver: Nomados Literary Publishers, 2012 (also out of print, ridiculously enough) — is partly my attempt to recapitulate the disavowed Lyric, but by making of it an icky formalism.

2. How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?(But I’ve always thought and felt that poetry wasnon-fiction! Creative non-fiction. Didn’t both Melvil Dewey and Charles Bernstein plump for that?)

I came to poetry simultaneously with making 8mm silent movies and writing horror fiction.

I was emotionally drawn to it without knowing why.

There’s still something ineffable about poetry to me. It can be mischievous, mysterious, flexible, anarchic. Any day I whollyapprehend what it does or upon it losing those qualities will be the day I likely stop writing poems.

That impulse to make movies is long gone, without regret. Same for the horror stories, although it’s very fair to say that most of my poems are in essence that, “transcribed” into broken-plot, poetic takes.

“Brains!” ejaculates zombie capitalism. “The political economy did this to me” cries the dying patient.

3. How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?“Copious notes” is a phrase that rings a big gong. My basic unit of composition is the line. Which can be a single word. I’m always scribbling quickly to no particular order. (This fully unleashes the hounds of inspiration and evades the potentates of censorship.) Adding the lines to a permanent stack of pages. Quick lines, slow poems.

4. Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a “book” from the very beginning?Rarely do I know that I’m working on a book. It’s more like one old poem-foot before the next old poem-foot, soldier, selah. The material for the poems comes from that motherlode of single lines I accumulate from daily writing. I get (in pukka) a conceptual arc or (in common yammering) a lightbulb for something that might make an interesting or exciting text, then start collating lines from the wad that speak to and against it. Lines get rewritten, new lines pop up, lines get shifted around, some of what I think are my better lines get cut, then Un Viola!, poem.

I don’t write a poem as much as edit one into being.

5. Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?I do enjoy giving readings, although they make me deeply nervous. Which I figure should be the case, part of the human comedy.

More to the point is public readings as part of our social process. No actual public without people in a room, perpetrating live text. This may be heresy, but I consider poetry readings to be television. Aaaiiiii! Well, they’re mytelevision, anyway (I live without standard toys and furniture). I prefer noisier readings, though there’s a lot to be said for the quiet of responsive listening. Poetry shouldn’t resemble a religious service. We need no Church of Poetry idolatry.

Now I’ll contradict myself by saying I also believe that Bill Hicks quip: “Watching TV is like taking black spray paint to your third eye.”

6. Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?No theoretical concerns whatsoever. I’m not that bright when it comes to theory and I’m in thrall to my kitbag of horrid obsessions (power, war, money, sex, pain, death) and I’m devoted to creating a high-octane reading experience for people and I’m not interested in hacking out cultural recipe cards. I try to complicate answers rather than solve any questions. I have a questing sensibility and I want that doing whatever throughout a poem. “Botches? We don’t feed no stinking ….”

7. What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?Ideally, the writer should be a bisexual hermaphrodite. A witness, a testifier, a historian, a saboteur, an agent devoted to destroying the normative. A living-room comic and a bedroom doctor.

8. Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?Both. It’s humbling though necessary to realize that it’s fatuous, risky, arrogant, and self-sabotaging to consider your own sentience an infallible god; that you need help; that you need an outside perspective; that you yourself can’t be that outsider. Best to seek assistance.

9. What is the best piece of advice you’ve heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?“Make it weirder.” The incredible Kevin Davies ( The Golden Age of Paraphernalia , among others) goes around proselytizing that. To the degree that he will ever proselytize anything!

This was something I learned from years of being his friend, briefly in Toronto and then longer in Vancouver (he’s lived predominantly in New York since 1992). What I believe he means is that one should be brave and take chances in text and not homogenize them into safe or simple objects with a forced or false single point of view. Make them richer, make them stranger.

10. What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?I wake at dawn (or earlier, if lucky or unfortunate). Harvest the nightmares. Put the coffee on. Drink it (two cups, max). Maintain the dream-state of a silent apartment. Read other people’s poetry for an hour. Write poetry for another hour. Then Amy Goodman’s “Democracy Now!” Then into the quotidian roar.

Needles to say, when trying to get a poem made, batches of long hours have to happen. Scheduled whenever practical.

11. When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?I let it get stalled. There’s no virtue in rushing or forcing anything. I’ve learned that over a goodly spell of bitter years! You just wreck the text if you try.

12. What fragrance reminds you of home?Notwithstanding that my sense of home is largely prosthetic … My mother’s cigarette smoke.

13. David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?Music.

14. What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?Political material.

15. What would you like to do that you haven’t yet done?Live in a democracy (as opposed to In Capitalism).

16. If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?No idea.

Maybe I would have run away with a circus. The classical “geek” job might have suited me best.

Or maybe that would have been unnecessary. Could be that the circus has always already surrounded us and is now most certainly the Panopticon.

17. What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?We need language. We are language. Why not work with the primal stuff? And, on a practical level, it’s the most flexible, portable, and materially cheap art form.

18. What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?I resist completely even the notion of Great Books. I find that thinking in those terms at all is a shortcut to ending up with sexist, classist, and racist Top Tens, as well as canonical reifications.

I prefer to consider and revisit the “merely interesting”!

I read a fair bit and my tastes are pretty catholic. I’ll restrict my picks to recent Canadian poetry in the more Language-y or conceptual parts of the spectrum. (Which will exclude a lot.)

To anyone looking for adventure, I strongly recommend Sandra Ridley’s Post-Apothecary and Christine McNair’s Conflict. Both these books are emotionally hot and brave, marbled with darkness, tonally and syntactically complex.

I’m always happy to revisit the planets constituted by Donato Mancini’s Buffet World and Louis Cabri’s Poetryworld. Their conceptual rigours, bold politics, and anarchic humours are exemplary. (See also new books by these fine fellows: Posh Lust by Cabri and Loitersack by Mancini.)

Speaking of anarchy, NDN word-warrior Annharte’s Indigena Awry is a critically important and gloriously troublesome feast. Often woundingly funny and very moving. (See also her more recent book of essays, AKA Inendagosekwe.)

Jonathan Ball’s The Politics of Knives trucks in a more pixilated blackness and crueler humour than his previous, Clockfire , which is saying a lot!

Roy Miki’s Mannequin Rising might be his most affable book yet, as well as his most difficult. Go figure. Most dystopian, and funniest.

Cecily Nicholson’s Triage deploys a stunningly elliptical, pulverized syntax to theatricalize, internalize, and confront the crises in and of capitalism. Very impressive! It’s a humane muttering in service of a permanent rebellion, and demands slow reading.

Roewan Crowe’s Quivering Land is a significant, liberatory queering of the Western. A protean text (prose? poetry? both? say what?) complicated by bleakness and lavishness. Crowe is also a visual artist, and this book has to be one of the more gorgeous objects in contemporary trade book production. Includes reproductions of hand-cut paper images by Paul Robles.

Jeff Derksen’s The Vestiges is fabulously necessary. It’s a sober and often witheringly witty examination of the Permanent Neoliberal Crisis we’re all living in. Long poems; the parenthetical shifted into the relative city square of things; lots of hot, centripetal action.

Catriona Strang’s first solo book in about twenty years (she being more inclined to collaborate with the late Nancy Shaw) is Corked , and it is a gorgeous riot. Outraged female life and labour in neo(bruta)liberal Vanhattan BC HarperLand. Poetically and sonically exact; satirically geologic. Ponk rawk, wiped memory, a sensible sadness. “Dear Strang, You are so not yoga [cackle].”

Trish Salah’s work is a big new love for me. Her Lyric Sexology, Vol. 1 is a thrilling swirl of poetic field work on gender construction from an exquisitely smart trans perspective. Language spirals through itself thickly, and there’s a sardonic, camp humour happening, too. “I didn’t mean to become an I.” “I am counting the kinds of impossible / No one ever is”.

With Janey’s Arcadia, Rachel Zolf has gifted us with an acidic and coruscating calling out of the permanent colonialism and devolved racism against Kanata’s indigenous peoples. It is a beautiful (and occasionally blackly funny) fury. I hope it helps destroy Canada into a just formation.

The densely rippled sonics happening throughout Natalie Simpson’s Thrum are, not simply, thrilling! “Poetics of hop and pop.” A book of abundance.

Over thirty years and several books, Colin Browne has been working up his slantwise, scholarly, and underhandedly irreverent take on the Lyric tradition to an increasing sophistication and oddness. Thus: The Properties .

o w n is a unique book. Three authors — a rawlings, Heather Hermant, and Chris Turnbull — are yoked together by their ecological concerns. Styles here are wide-ranging, though — rawlings contributes a play that would be impossible to mount, while Hermant and Turnbull have image-text pieces coming from very different sentiences and poetics. Fascinating!

Nikki Reimer’s Downverse is such a dark read, O god! She’s fond of procedural sculpting toward rich, overdetermined textures. Subject matter is often harrowing — economic and political violence and injustice. There are a lot of trolls in this book. Hideous socialscapes of Vancouver and Calgary. Cultural horrors. Anthracite wit. So much “inappropriate” fun, yum!

With Un/inhabited, Jordan Abel has rejigged a text dump of ninety-one Westerns — using techniques of erasure, cartography, and extraction — into a righteous reverse engineering that enables us to look accurately at Canada as a colonialist entity. As much a piece of visual art as poetry, this book is baffling, moving, and bleakly funny in all the good ways.

What else?

The (to my mind) much overdue emergence of Lary Timewell with a big book, posthumous spectacle nodes . (There’s a shorter one out, too: the ubiquitous gaze of che .)

The complicated historical takedown or mixtape that is Paul Zits’s Massacre Street is quite interesting. Unreliable and unlocatable narrators, erm, “rule.” (Along similar topical and tactical lines, Dilys Leman’s The Winter Count.)

Mercedes Eng’s Mercenary English and Roger Farr’s MEANS offer, respectively, properly enraged and antically disinhibiting takes on the dark matter of some political “social”s (torture paradigms, money loops) too many of us are trapped in.

Kristian Enright’s madly optimistic Sonar. Erín Moure’s passionate The Unmemntioable. The luscious contrivance that is Lesley Trites’s echoic mimic.

Elizabeth Bachinsky’s I Don’t Feel So Good has several “something about”s about it. Jennifer Still’s Girlwood is a complicated ha’nt.

The plangent, furious, and terrifying dystopia (world-class size) that is Sachiko Murakami’s Rebuild. The alchemical zaniness that is Ken Fox’s Azmud.

Aisha Sasha John’s lusciously strange THOU. Gil McElroy’s haunted and bruising Ordinary Time. A couple of minimalist texts I enjoyed very much are Chantal Neveu’s Coït (translated by Angela Carr) and Mark Goldstein’s Form of Forms.

Speaking of making more with less, a production entity yclept Intercopy has perpetrated a worthy insanity by vastly reducing Georges Bataille’s novel Saccades into a sparse poem obsessed with liquids. Yow!, it’s funny and serious.

Sina Queyras’s astounding (and wonkily funny!) essay on grief, M × T. Jen Currin’s School wends through the bent theology that is life — surrealism on a pogo stick; lots of wry emotion.

For those interested in how technology is changing our worlds and how social-media devices are affecting the ways we communicate, Jason Christie’s Unknown Actor and Margaret Christakos’s Multitudes are similar yet different takes on the matter. Both, however, stand as droll and disturbing.

Claire Lacey’s Twin Tongues is a sharp investigation of language imperialisms. Starring a crow named Jasper, a white teacher’s aide named English, the ideolect of Tok Pisin, and Papua New Guinea.

The transmutation-by-subtraction effects of Alex Leslie’s The things I heard about you give these prose-poems a weird charm and anarchic wobble.

The broken-Lyric-bendy-Anti-Lyric contemplations of rob mclennan’s Glengarry.

The hankering mess of human erotics going on in Ian Williams’s Personals.

We must not flinch from the comprehensive unease happening in Rita Wong’s political ode to water, undercurrent.

Anything else? Yes.

Some wonderful books of deeply off-kilter humour: kevin mcpherson eckhoff’s easy peasy; Alice Burdick’s Holler; Pearl Pirie’s Thirsts; Jon Paul Fiorentino’s Needs Improvement; Charles Noble’s The Kindness Colder Than the Elements; Beatriz Hausner’s Enter the Raccoon; Jay MillAr’s Timely Irreverence; [N]athan [D]ueck’s he’ll; Emma Healey’s Begin with the End in Mind; David McGimpsey’s Li’l Bastard; and Kathryn Mockler’s The Purpose Pitch(caution: this one includes a ghastly poem about rape).

Twelve chapbooks I care to tout: Edward Byrne’s translations of Louise Labé, Sonnets; Michael Barnholden’s The Regina Monologues: So(cial safety)nnets; Reg Johanson’s Mortify; Robert Manery’s Richter-Rauzer Variations; Fenn Stewart’s An OK Organ Man; Marilyn Irwin’s flicker; Stephen Cain’s Zoom; Jen Currin’s The Ends; Christine Leclerc’s Oilywood; Lissa Wolsak’s Of Beings Alone: The Eigenface; Brian Dedora’s Two at High Noon; and Christine Stewart’s The Odes.

Finally, I’ll swerve off the editorial path I set at the beginning of answering this question (oh, you expected me to be consistent, did you?) to recommend Clint Burnham’s The Only Poetry That Matters: Reading the Kootenay School of Writing and Amber Dawn’s How Poetry Saved My Life: A Hustler’s Memoir. Not many books like these two. Not enough of their ilk, either.

Last kick-ass film? That’s way easier to answer. I’ll give you my last two: Michael Haneke’s Amour and Jeff Nichols’s Take Shelter.

19. What are you currently working on?A chapbook-length manuscript of poems for Lary Bremner’s obvious epiphanies press. These’ll be more intimate in tone and address than what I most often do (which is a large motivation for writing them). Although I doubt I can ever truly duck the hideous Public Service Announcement UnVoice that I tend to use, these are all dedicated to actual people and have a homier slant to them.

Am also working on a longish poem called “Quear.” Nuff said.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on October 27, 2015 05:31