Greg Mitchell's Blog, page 57

August 6, 2014

Conservatives Who Hit Hiroshima Attack

Good new piece by Bart Bernstein, the Stanford prof and nuclear era expect, describing the surprising number of conservatives who have criticized the use of the atomic bomb almost from the beginning. List includes everyone from Herbert Hoover to mad bomber Gen. Curtis LeMay. Oddly, he leaves out Gen. Eisenhower and John Foster Dulles.

Published on August 06, 2014 12:00

Hawking a New Trailer

Just out: first trailer for the Stephen Hawking bio-pic coming this November.

Published on August 06, 2014 11:47

Rudoren to the Rescue on Civilian Toll

What a shock: NYT Jerusalem bureau chief finally journeys to Gaza--to promote Israeli claims that the civlian toll is much lower than everyone else has it. Of course, it's the top story on the Times' site now, even with her record of taking ultra-seriously false Israeli claims at face value (such as attacks on schools and captured soldier). Note that early on she cites "impressive documentation" of one Israeli group---based on just 152 casualties.

What a shock: NYT Jerusalem bureau chief finally journeys to Gaza--to promote Israeli claims that the civlian toll is much lower than everyone else has it. Of course, it's the top story on the Times' site now, even with her record of taking ultra-seriously false Israeli claims at face value (such as attacks on schools and captured soldier). Note that early on she cites "impressive documentation" of one Israeli group---based on just 152 casualties."Palestinians and their supporters contend...." No, it's the UN and such groups, not just the Palestinians. Balance: Palestinians claim there was indiscriminate fire killing whole families, but: "Israel has published extensive video images of warplanes aborting missions to avoid collateral damage, and provided summaries of warnings it gave residents before attacking buildings." Rudoren concludes that "perhaps" a majority were civilians (apparently far less than than 72% to 82% figures provided by all others, except the Israelis).

Then:

But the difference between roughly half the dead being combatants, in the Israeli version, or barely 10 percent, to use the most stark numbers on the other side, is wide enough to change the characterization of the conflict.First the "other side" is the UN. And they do not claim 10% but 28%. Finally, her claim that if the world would only accept the Israeli tally of just half being civilians then this will change common view of the tragedy--which is straight stenography.

Then we see that she highlights the claim that most of the men between 20 and 29 might quite likely be Hamas fighters, which is ludicrous. She wonders why men of that age seem to be "over-represented" in the death counts. Well, could it be that they make up the vast majority of people who are out in the streets gathering the dead and injured, digging in the rubble, rushing for home supplies who then fall victim to Israeli strikes--not to mention the many medics, ambulances drivers, even a dozen journalists, killed? She also points to claims that anyone who is merely "affiliated" with Hamas--which, after all, is the elected government and runs the ministries and daily services--might be considered combatant.

Published on August 06, 2014 06:24

August 5, 2014

That Ray Conniff Singer and Nixon

If you watched the HBO doc Nixon on Nixon last night, or on HBO GO this week, you may have noted an incident I'd long forgotten--the night at the White House in early 1972 when a singer with the super-square Ray Conniff Singers held up a protest sign vs. the Vietnam war and gave a little speech--"Bless the Berrigans, and Bless Daniel Ellsberg"--as they were about to go into their first super-square song. Nixon was there, for course, but so were Charles Lindbergh, Frank Borman, Lionel Hampton, Billy Graham, Bob Hope, and so on. It was a dinner for the Reader's Digest. Martha Mitchell said, "She ought to be torn limb from limb." You don't learn any of this from the doc but it's all in a lengthy 1997 piece in the Wash Post. She got booted out after that first song. Her name now rings a bell--Carole Feraci. And she was still alive in '97 and talked to the Post.

Published on August 05, 2014 20:48

When Truman Opened the Nuclear Era With a Lie

[image error]

When the shocking news emerged that morning, exactly sixty-nine years ago, it took the form of a routine press release, a little more than 1,000 words long. President Harry S. Truman was in the middle of the Atlantic, returning from the Potsdam conference with Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin. Shortly before 11 o’clock, an information officer from the Pentagon arrived at the White House carrying bundles of press releases. A few minutes later, assistant press secretary Eben Ayers started reading the announcement to about a dozen members of the Washington press corps.

In this way, on this day, President Truman informed the press, and the world, that America’s war against fascism—with victory over Germany already in hand—had culminated in exploding a revolutionary new weapon over a Japanese target.

The atmosphere was so casual, many reporters had difficulty grasping the announcement. “The thing didn’t penetrate with most of them,” Ayers later remarked. Finally, the journalists rushed to call their editors.

The first few sentences of the statement set the tone: “Sixteen hours ago an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese Army base. That bomb had more power than 20,000 tons of TNT.…The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid many fold…. It is an atomic bomb. It is a harnessing of the basic power of the universe.”

Truman’s four-page statement had been crafted with considerable care over many months, as my research at the Truman Library for two books on the subject made clear. With use of the atomic bomb rarely debated at the highest levels, an announcement of this sort was inevitable—if the new weapon actually worked.

Those who helped prepare the presidential statement—principally Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson—sensed that the stakes were high, for this marked the unveiling of both the atomic bomb and the official narrative of Hiroshima, which largely persists to this day. It was vital that this event be viewed as consistent with American decency and concern for human life.

And so, from its very first words, the official narrative was built on a lie, or at best a half-truth.

Hiroshima did contain an important military base, used as a staging area for Southeast Asia, where perhaps 25,000 troops might be quartered. But the bomb had been aimed not at the “Army base” but at the very center of a city of 350,000, with the vast majority women and children and elderly males (probably 30,000 children would die that day or in weeks and months that followed).

In fact, the two most important reasons Hiroshima had been chosen as our number-one target were: it had been relatively untouched by conventional bombs, meaning its large population was still in place and the bomb’s effects could be fully judged; and the hills which surround the city on three sides would have a “focusing effect” (as the target committee put it), increasing the bomb’s destructive force.

Indeed, a US survey of the damage, not released to the press, found that residential areas bore the brunt of the bomb, with less than 10 percent of the city’s manufacturing, transportation and storage facilities damaged.

There was something else missing in the Truman announcement: because the president in his statement failed to mention radiation effects, which officials knew would be horrendous, the imagery of just “a bigger bomb” would prevail for days in the press. Truman described the new weapon as “revolutionary” but only in regard to the destruction it could cause, failing to even mention its most lethal new feature: radiation.

In many ways, the same dangerous myth about nuclear weapons, first promoted by Truman, persists in the minds of many today: that any use of the more powerful weapons of today by a state (say, the United States or Israel) could be and would be targeted on strictly military enclaves or weapon sites, with little threat to thousands or millions living nearby.

Many Americans on August 6, 1945, heard the news from the radio, which broadcast the text of Truman’s statement shortly after its release. The afternoon papers carried banner headlines along the lines of: “Atom Bomb, World’s Greatest, Hits Japs!”

On the evening of August 9, Truman addressed the American people over the radio. Again he took pains to picture Hiroshima as a military base, even claiming that “we wished in the first attack to avoid, in so far as possible, the killing of civilians.” By then, an American B-29 had dropped a second atomic bomb over the city of Nagasaki, which killed tens of thousands of civilians and only a handful of Japanese troops (along with Allied prisoners of war). Nagasaki was variously described by US officials as a “naval base” or “industrial center.”

Greg Mitchel is the author of more than a dozen books, including Atomic Cover-Up (on the decades-long suppression of shocking film shot in the atomic cities by the US military) and Hollywood Bomb (the wild story of how an MGM 1947 drama was censored by the military and Truman himself).

In this way, on this day, President Truman informed the press, and the world, that America’s war against fascism—with victory over Germany already in hand—had culminated in exploding a revolutionary new weapon over a Japanese target.

The atmosphere was so casual, many reporters had difficulty grasping the announcement. “The thing didn’t penetrate with most of them,” Ayers later remarked. Finally, the journalists rushed to call their editors.

The first few sentences of the statement set the tone: “Sixteen hours ago an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese Army base. That bomb had more power than 20,000 tons of TNT.…The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid many fold…. It is an atomic bomb. It is a harnessing of the basic power of the universe.”

Truman’s four-page statement had been crafted with considerable care over many months, as my research at the Truman Library for two books on the subject made clear. With use of the atomic bomb rarely debated at the highest levels, an announcement of this sort was inevitable—if the new weapon actually worked.

Those who helped prepare the presidential statement—principally Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson—sensed that the stakes were high, for this marked the unveiling of both the atomic bomb and the official narrative of Hiroshima, which largely persists to this day. It was vital that this event be viewed as consistent with American decency and concern for human life.

And so, from its very first words, the official narrative was built on a lie, or at best a half-truth.

Hiroshima did contain an important military base, used as a staging area for Southeast Asia, where perhaps 25,000 troops might be quartered. But the bomb had been aimed not at the “Army base” but at the very center of a city of 350,000, with the vast majority women and children and elderly males (probably 30,000 children would die that day or in weeks and months that followed).

In fact, the two most important reasons Hiroshima had been chosen as our number-one target were: it had been relatively untouched by conventional bombs, meaning its large population was still in place and the bomb’s effects could be fully judged; and the hills which surround the city on three sides would have a “focusing effect” (as the target committee put it), increasing the bomb’s destructive force.

Indeed, a US survey of the damage, not released to the press, found that residential areas bore the brunt of the bomb, with less than 10 percent of the city’s manufacturing, transportation and storage facilities damaged.

There was something else missing in the Truman announcement: because the president in his statement failed to mention radiation effects, which officials knew would be horrendous, the imagery of just “a bigger bomb” would prevail for days in the press. Truman described the new weapon as “revolutionary” but only in regard to the destruction it could cause, failing to even mention its most lethal new feature: radiation.

In many ways, the same dangerous myth about nuclear weapons, first promoted by Truman, persists in the minds of many today: that any use of the more powerful weapons of today by a state (say, the United States or Israel) could be and would be targeted on strictly military enclaves or weapon sites, with little threat to thousands or millions living nearby.

Many Americans on August 6, 1945, heard the news from the radio, which broadcast the text of Truman’s statement shortly after its release. The afternoon papers carried banner headlines along the lines of: “Atom Bomb, World’s Greatest, Hits Japs!”

On the evening of August 9, Truman addressed the American people over the radio. Again he took pains to picture Hiroshima as a military base, even claiming that “we wished in the first attack to avoid, in so far as possible, the killing of civilians.” By then, an American B-29 had dropped a second atomic bomb over the city of Nagasaki, which killed tens of thousands of civilians and only a handful of Japanese troops (along with Allied prisoners of war). Nagasaki was variously described by US officials as a “naval base” or “industrial center.”

Greg Mitchel is the author of more than a dozen books, including Atomic Cover-Up (on the decades-long suppression of shocking film shot in the atomic cities by the US military) and Hollywood Bomb (the wild story of how an MGM 1947 drama was censored by the military and Truman himself).

Published on August 05, 2014 19:29

Marquez and Kurosawa on Hiroshima

One of the greatest novelists of the past century, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, died this April at the age of 87. I join, what, hundreds of millions in declaring his One Hundred Years of Solitude one of my all-time 20 favorite novels. He was, of course, extremely outspoken about American wars in his part of the world, the Pinochet coup, and much more, displeasing many Americans, of course. And he had a long interest in one of my pet subjects--controlling nuclear weapons, and exposing truths about Hiroshima. His famous speech marking one of the anniveraries of the Hiroshima attack was titled "Cataclysm of Damocles."

One of the greatest novelists of the past century, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, died this April at the age of 87. I join, what, hundreds of millions in declaring his One Hundred Years of Solitude one of my all-time 20 favorite novels. He was, of course, extremely outspoken about American wars in his part of the world, the Pinochet coup, and much more, displeasing many Americans, of course. And he had a long interest in one of my pet subjects--controlling nuclear weapons, and exposing truths about Hiroshima. His famous speech marking one of the anniveraries of the Hiroshima attack was titled "Cataclysm of Damocles."Here is part of a transcript from a dialogue he conducted with my favorite director, also at times obsessed with The Bomb, Akira Kurosawa. It was at the time of his very late film, Rhapsody in August, set in Nagasaki. They even refer more than once to the focus of my recent book, Atomic Cover-up. The full interview is here.

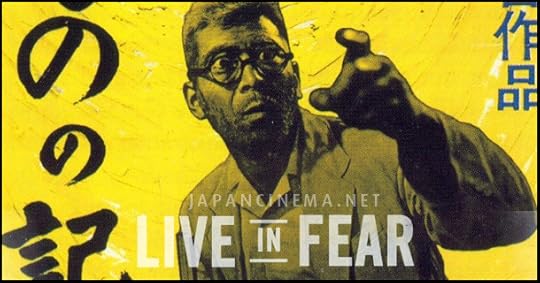

Marquez: What does that historical amnesia mean for the future of Japan, for the identity of the Japanese people?Poster for Kurosawa's mid-1950s anti-bomb film, with Toshiro Mifune:

Kurosawa: The Japanese don't talk about it explicitly. Our politicians in particular are silent for fear of the United States. They may have accepted (President Harry) Truman's explanation that he resorted to the atomic bomb only to hasten the end of the World War. Still, for us, the war goes on. The full death toll for Hiroshima and Nagasaki has been officially published at 230,000. But in actual fact there were over half a million dead. And even now there are still 2,700 patients at the Atomic Bomb Hospital waiting to die from the after-effects of the radiation after 45 years of agony. In other words, the atomic bomb is still killing Japanese.

Marquez: The most rational explanation seems to be that the U.S. rushed in to end it with the bomb for fear that the Soviets would take Japan before they did.

Kurosawa: Yes, but why did they do it in a city inhabited only by civilians who had nothing to do with the war? There were military concentrations that were in fact waging (war).

Marquez: Nor did they drop it on the Imperial Palace, which must have been a very vulnerable spot in the heart of Tokyo. And I think that this is all explained by the fact that they wanted to leave the political power and the military power intact in order to carry out a speedy negotiation without having to share the booty with their allies. It's something no other country has ever experienced in all of human history. Now then: Had Japan surrendered without the atomic bomb, would it be the same Japan it is today?

Kurosawa: It's hard to say. The people who survived Nagasaki don't want to remember their experience because the majority of them, in order to survive, had to abandon their parents, their children, their brothers and sisters. They still can't stop feeling guilty. Afterwards, the U.S. forces that occupied the country for six years influenced by various means the acceleration of forgetfulness, and the Japanese government collaborated with them. I would even be willing to understand all this as part of the inevitable tragedy generated by war. But I think that, at the very least, the country that dropped the bomb should apologize to the Japanese people. Until that happens this drama will not be over.

Marquez: That far? Couldn't the misfortune be compensated for by a long era of happiness?

Kurosawa: The atomic bomb constituted the starting point of the Cold War and of the arms race, and it marked the beginning of the process of creation and utilization of nuclear energy. Happiness will never be possible given such origins.

Marquez: I see. Nuclear energy was born as a cursed force, and a force born under a curse is a perfect theme for Kurosawa. But what concerns me is that you are not condemning nuclear energy itself, but the way it was misused from the beginning. Electricity is still a good thing in spite of the electric chair.

Kurosawa: It is not the same thing. I think nuclear energy is beyond the possibilities of control that can be established by human beings. In the event of a mistake in the management of nuclear energy, the immediate disaster would be immense and the radioactivity would remain for hundreds of generations. On the other hand, when water is boiling, it suffices to let it cool for it to no longer be dangerous. Let's stop using elements which continue to boil for hundreds of thousands of years.

Marquez: I owe a large measure of my own faith in humanity to Kurosawa's films. But I also understand your position in view of the terrible injustice of using the atomic bomb only against civilians and of the Americans and Japanese colluding to make Japan forget. But it seems to me equally unjust for nuclear energy to be deemed forever accursed without considering that it could perform a great non-military service for humanity. There is in that a confusion of feelings which is due to the irritation you feel because you know Japan has forgotten, and because the guilty, which is to say, the United States, has not in the end come to acknowledge its guilt and to render unto the Japanese people the apologies due to them.

Kurosawa: Human beings will be more human when they realize there are aspects of reality they may not manipulate. I don't think we have the right to generate children without anuses, or eight-legged horses, such as is happening at Chernobyl. But now I think this conversation has become too serious, and that wasn't my intention.

Marquez: We've done the right thing. When a topic is as serious as this, one can't help but discuss it seriously. Does the film you are in the process of finishing cast any light on your thoughts in this matter?

Kurosawa: Not directly. I was a young journalist when the bomb was dropped, and I wanted to write articles about what had happened, but it was absolutely forbidden until the end of the occupation. Now, to make this film, I began to research and study the subject and I know much more than I did then. But if I had expressed my thoughts directly in the film, it could not have been shown in today's Japan, or anywhere else.

Marquez: Do you think it might be possible to publish the transcript of this dialogue?

Kurosawa: I have no objection. On the contrary. This is a matter on which many people in the world should give their opinion without restrictions of any sort.

Marquez: Thank you very much. All things considered, I think that if I were Japanese I would be as unyielding as you on this subject. And at any rate I understand you. No war is good for anybody.

Kurosawa: That is so. The trouble is that when the shooting starts, even Christ and the angels turn into military chiefs of staff.

Marquez: What does that historical amnesia mean for the future of Japan, for the identity of the Japanese people?

Kurosawa: The Japanese don't talk about it explicitly. Our politicians in particular are silent for fear of the United States. They may have accepted (President Harry) Truman's explanation that he resorted to the atomic bomb only to hasten the end of the World War. Still, for us, the war goes on. The full death toll for Hiroshima and Nagasaki has been officially published at 230,000. But in actual fact there were over half a million dead. And even now there are still 2,700 patients at the Atomic Bomb Hospital waiting to die from the after-effects of the radiation after 45 years of agony. In other words, the atomic bomb is still killing Japanese.

Marquez: The most rational explanation seems to be that the U.S. rushed in to end it with the bomb for fear that the Soviets would take Japan before they did.

Kurosawa: Yes, but why did they do it in a city inhabited only by civilians who had nothing to do with the war? There were military concentrations that were in fact waging (war).

Marquez: Nor did they drop it on the Imperial Palace, which must have been a very vulnerable spot in the heart of Tokyo. And I think that this is all explained by the fact that they wanted to leave the political power and the military power intact in order to carry out a speedy negotiation without having to share the booty with their allies. It's something no other country has ever experienced in all of human history. Now then: Had Japan surrendered without the atomic bomb, would it be the same Japan it is today?

Kurosawa: It's hard to say. The people who survived Nagasaki don't want to remember their experience because the majority of them, in order to survive, had to abandon their parents, their children, their brothers and sisters. They still can't stop feeling guilty. Afterwards, the U.S. forces that occupied the country for six years influenced by various means the acceleration of forgetfulness, and the Japanese government collaborated with them. I would even be willing to understand all this as part of the inevitable tragedy generated by war. But I think that, at the very least, the country that dropped the bomb should apologize to the Japanese people. Until that happens this drama will not be over.

Marquez: That far? Couldn't the misfortune be compensated for by a long era of happiness?

Kurosawa: The atomic bomb constituted the starting point of the Cold War and of the arms race, and it marked the beginning of the process of creation and utilization of nuclear energy. Happiness will never be possible given such origins.

Marquez: I see. Nuclear energy was born as a cursed force, and a force born under a curse is a perfect theme for Kurosawa. But what concerns me is that you are not condemning nuclear energy itself, but the way it was misused from the beginning. Electricity is still a good thing in spite of the electric chair.

Kurosawa: It is not the same thing. I think nuclear energy is beyond the possibilities of control that can be established by human beings. In the event of a mistake in the management of nuclear energy, the immediate disaster would be immense and the radioactivity would remain for hundreds of generations. On the other hand, when water is boiling, it suffices to let it cool for it to no longer be dangerous. Let's stop using elements which continue to boil for hundreds of thousands of years.

Marquez: I owe a large measure of my own faith in humanity to Kurosawa's films. But I also understand your position in view of the terrible injustice of using the atomic bomb only against civilians and of the Americans and Japanese colluding to make Japan forget. But it seems to me equally unjust for nuclear energy to be deemed forever accursed without considering that it could perform a great non-military service for humanity. There is in that a confusion of feelings which is due to the irritation you feel because you know Japan has forgotten, and because the guilty, which is to say, the United States, has not in the end come to acknowledge its guilt and to render unto the Japanese people the apologies due to them.

Kurosawa: Human beings will be more human when they realize there are aspects of reality they may not manipulate. I don't think we have the right to generate children without anuses, or eight-legged horses, such as is happening at Chernobyl. But now I think this conversation has become too serious, and that wasn't my intention.

Marquez: We've done the right thing. When a topic is as serious as this, one can't help but discuss it seriously. Does the film you are in the process of finishing cast any light on your thoughts in this matter?

Kurosawa: Not directly. I was a young journalist when the bomb was dropped, and I wanted to write articles about what had happened, but it was absolutely forbidden until the end of the occupation. Now, to make this film, I began to research and study the subject and I know much more than I did then. But if I had expressed my thoughts directly in the film, it could not have been shown in today's Japan, or anywhere else.

Marquez: Do you think it might be possible to publish the transcript of this dialogue?

Kurosawa: I have no objection. On the contrary. This is a matter on which many people in the world should give their opinion without restrictions of any sort.

Marquez: Thank you very much. All things considered, I think that if I were Japanese I would be as unyielding as you on this subject. And at any rate I understand you. No war is good for anybody.

Kurosawa: That is so. The trouble is that when the shooting starts, even Christ and the angels turn into military chiefs of staff. - See more at: http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/jacke...

Published on August 05, 2014 14:00

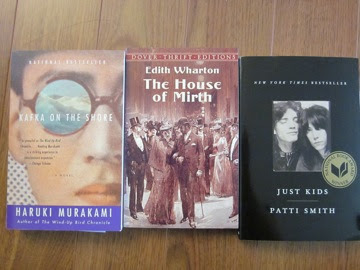

Patti in 'Review'

NYT just posted review (maybe even its the cover) from its Sunday Book Review coming up, by Patti Smith on the new Murakami novel. "The writer sits at his desk and makes us a story. A story not knowing where it is going, not knowing itself to be magic. Closure is an illusion, the winking of the eye of a storm. Nothing is completely resolved in life, nothing is perfect. The important thing is to keep living because only by living can you see what happens next."

NYT just posted review (maybe even its the cover) from its Sunday Book Review coming up, by Patti Smith on the new Murakami novel. "The writer sits at his desk and makes us a story. A story not knowing where it is going, not knowing itself to be magic. Closure is an illusion, the winking of the eye of a storm. Nothing is completely resolved in life, nothing is perfect. The important thing is to keep living because only by living can you see what happens next."

Published on August 05, 2014 12:55

Climate Change and Hiroshima

Not sure I agree with her conclusion, but interesting analysis at esteemed Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists on climate change activists (and Neil Young) comparing it to "Hiroshima." Writer looks at pros and cons of this but ultimately concludes that it is apt. (My latest Hiroshima piece.)

Sure, the mushroom cloud has become a cliché image for conveying disaster. It’s an apt one in this case, though. The picture of a mushroom cloud over Hiroshima is buried deep within America’s national consciousness, and awareness of the bomb’s impacts is what ultimately led to international treaties aimed at preventing any future use of nuclear weapons. To avert another tragedy of global proportions, the world’s superpowers must now lay down their fossil fuels as well.

Climate change won’t destroy future generations as instantaneously as Little Boy incinerated the people of Hiroshima, but continuing with business as usual guarantees that millions of people will die as a result. If the Hiroshima meme “trades on human tragedy to make an illustrative point,” as one blog commenter complained, it does so with abundant moral justification.

Published on August 05, 2014 08:40

Colbert Does Nixon

Special show last night on Nixon and Watergate and resigning 40 years ago....with John Dean and Pat Buchanan (plus sideburns and cig). One segment:

The Colbert Report

Get More: Colbert Report Full Episodes,The Colbert Report on Facebook,Video Archive

The Colbert Report

Get More: Colbert Report Full Episodes,The Colbert Report on Facebook,Video Archive

Published on August 05, 2014 07:44

'Dog Day' in August

New doc opening this week on true-life guy who inspired the Pacino portrayal in great film. Trailer:

Published on August 05, 2014 07:34