Greg Mitchell's Blog, page 56

August 8, 2014

Hannibal Lectures

NYT finally with full piece on the controversial Hannibal Procedure (aka Protocol or Directive), under which Israeli forces are allowed to take great risks that could lead to death of one of their soldiers if taken captive. The last time this came up in a Times story a few days ago the reference was later cut, with no explanation from the paper why. This piece seems to accept the IDF claim that the dead/captured soldier Goldin was not killed by Israeli fire or shelling although others have raised that as a real possibility--but the Times presents no evidence and admits Israeli spokesman dodges key question. The Times reporter herself says it "appears unlikely"--how's that for hedging a bit?

Originally the Times and Israel claimed the soldier was blown up by suicide bomber but Haaretz cited a source saying not true and now this is left vague. The fact that it took DNA probe to ID remains of body suggests to some that poor Goldin perhaps was blown up, and not by suicide vest.

Now see major new Haaretz story which includes this: "The information available to Haaretz on the events is partial and based on sources from the Israeli side only. Realizing the possibility of legal proceedings abroad, the IDF is in no hurry to volunteer all the details." It too is hazy on what killed Goldin. It does note that a soldier tossed grenade into a tunnel where Goldin might have been taken. In any event, Israel's all-out response led to the deaths of over 120 Gazans.

The chance that Goldin died by friendly fire seems to have occurred to some Israelis, if not most reporters. Public Radio International covered Goldin's funeral:

Originally the Times and Israel claimed the soldier was blown up by suicide bomber but Haaretz cited a source saying not true and now this is left vague. The fact that it took DNA probe to ID remains of body suggests to some that poor Goldin perhaps was blown up, and not by suicide vest.

Now see major new Haaretz story which includes this: "The information available to Haaretz on the events is partial and based on sources from the Israeli side only. Realizing the possibility of legal proceedings abroad, the IDF is in no hurry to volunteer all the details." It too is hazy on what killed Goldin. It does note that a soldier tossed grenade into a tunnel where Goldin might have been taken. In any event, Israel's all-out response led to the deaths of over 120 Gazans.

The chance that Goldin died by friendly fire seems to have occurred to some Israelis, if not most reporters. Public Radio International covered Goldin's funeral:

Shlomo Deutsch, one of thousands of Israelis who attended the funeral, says he supports the Hannibal Doctrine — even if it were to be directed at his own son, who also served in Gaza during this conflict. “If something happened with my son, and Hamas picked him up ... better his friend kill him,” Deutsch says. “For the country it’s better. It’s impossible what they want [Israel] to pay.”

By holding a funeral for his scant remains, Deutsch says, Goldin’s family refused Hamas a bargaining chip.The New Yorker also posted a piece yesterday.

Published on August 08, 2014 00:09

Hannibal Lecture

NYT finally with full piece on the controversial Hannibal Directive, under which Israeli forces are allowed to take great risks that could lead to death of one of their soldiers if taken captive. The last time this came up in a Times story a few days ago the reference was later cut, with no explanation from the paper why. This piece seems to accept the IDF claim that the dead/captured soldier Goldin was not killed by Israeli fire or shelling although others have raised that as a real possibility--but the Times presents no evidence and admits Israeli spokesman dodges key question. The Times reporter herself says it "appears unlikely"--how's that for hedging a bit?

Originally the Times and Israel claimed the soldier was blown up by suicide bomber but Haaretz cited a source saying not true and now this is left vague. The fact that it took DNA probe to ID remains of body suggests to some that poor Goldin perhaps was blown up, and not by suicide vest.

Now see major new Haaretz story which includes this: "The information available to Haaretz on the events is partial and based on sources from the Israeli side only. Realizing the possibility of legal proceedings abroad, the IDF is in no hurry to volunteer all the details." It too is hazy on what killed Goldin. It does note that a soldier tossed grenade into a tunnel where Goldin might have been taken. In any event, Israel's all-out response led to the deaths of over 120 Gazans.

Originally the Times and Israel claimed the soldier was blown up by suicide bomber but Haaretz cited a source saying not true and now this is left vague. The fact that it took DNA probe to ID remains of body suggests to some that poor Goldin perhaps was blown up, and not by suicide vest.

Now see major new Haaretz story which includes this: "The information available to Haaretz on the events is partial and based on sources from the Israeli side only. Realizing the possibility of legal proceedings abroad, the IDF is in no hurry to volunteer all the details." It too is hazy on what killed Goldin. It does note that a soldier tossed grenade into a tunnel where Goldin might have been taken. In any event, Israel's all-out response led to the deaths of over 120 Gazans.

Published on August 08, 2014 00:09

August 7, 2014

Leonard Cohen: Forever Young

Leonard Cohen biographer Sylvie Simmons, a Facebook friend, justed posted there: "A new Leonard Cohen studio album! Yep, as good as done and due out the last week of September, just after his 80th birthday." Recall that Leonard on tour has long threatened to start smoking again when he turns 80. Here's a new song he's done live recently. Below that a lately-discovered quite different version of "Hello Marianne" that he did in 1993 in Oslo.

Published on August 07, 2014 17:36

Hiroshima: The Day After

As noted yesterday, President Truman's announcement to the nation--in which he carefully IDed Hiroshima only as a "military base," not a large city--broke the news of both the invention of an atomic bomb and its first use in war. By that evening, radio commentators were weighing in with observations that often transcended Truman's announcement, suggesting that the public imagination was outrunning the official story. Contrasting emotions of gratification and anxiety had already emerged. H.V. Kaltenhorn warned, "We must assume that with the passage of only a little time, an improved form of the new weapon we use today can be turned against us."

As noted yesterday, President Truman's announcement to the nation--in which he carefully IDed Hiroshima only as a "military base," not a large city--broke the news of both the invention of an atomic bomb and its first use in war. By that evening, radio commentators were weighing in with observations that often transcended Truman's announcement, suggesting that the public imagination was outrunning the official story. Contrasting emotions of gratification and anxiety had already emerged. H.V. Kaltenhorn warned, "We must assume that with the passage of only a little time, an improved form of the new weapon we use today can be turned against us."It wasn't until the following morning, Aug. 7, that the government's press offensive appeared, with the first detailed account of the making of the atomic bomb, and the Hiroshima mission. Nearly every U.S. newspaper carried all or parts of 14 separate press releases distributed by the Pentagon several hours after the president's announcement. They carried headlines such as: "Atom Bombs Made in 3 Hidden Cities" and "New Age Ushered."

Many of them written by one man: W.L. Laurence, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for the New York Times, "embedded" with the atomic project. General Leslie Groves, military director of the Manhattan Project, would later reflect, with satisfaction, that "most newspapers published our releases in their entirety. This is one of the few times since government releases have become so common that this has been done."

The Truman announcement of the atomic bombing on Aug. 6, 1945, and the flood of material from the War Department, firmly established the nuclear narrative. It would not take long, however, for breaks in the official story to appear.

At first, journalists had to follow where the Pentagon led. Wartime censorship remained in effect, and there was no way any reporter could reach Hiroshima for a look around. One of the few early stories that did not come directly from the military was a wire service report filed by a journalist traveling with the president on the Atlantic, returning from Europe. Approved by military censors, it went beyond, but not far beyond, the measured tone of the president's official statement. It depicted Truman, his voice "tense with excitement," personally informing his shipmates about the atomic attack. "The experiment," he announced, "has been an overwhelming success."

The sailors were said to be "uproarious" over the news. "I guess I'll get home sooner now," was a typical response. Nowhere in the story, however, was there a strong sense of Truman's reaction. Missing from this account was his exultant remark when the news of the bombing first reached the ship: "This is the greatest thing in history!"

On Aug. 7, military officials confirmed that Hiroshima had been devastated: at least 60% of the city wiped off the map. They offered no casualty estimates, emphasizing instead that the obliterated area housed major industrial targets. The Air Force provided the newspapers with an aerial photograph of Hiroshima. Significant targets were identified by name. For anyone paying close attention there was something troubling about this picture. Of the 30 targets, only four were specifically military in nature. "Industrial" sites consisted of three textile mills. (Indeed, a U.S. survey of the damage, not released to the press, found that residential areas bore the brunt of the bomb, with less than 10% of the city's manufacturing, transportation, and storage facilities damaged.)

On Aug. 7, military officials confirmed that Hiroshima had been devastated: at least 60% of the city wiped off the map. They offered no casualty estimates, emphasizing instead that the obliterated area housed major industrial targets. The Air Force provided the newspapers with an aerial photograph of Hiroshima. Significant targets were identified by name. For anyone paying close attention there was something troubling about this picture. Of the 30 targets, only four were specifically military in nature. "Industrial" sites consisted of three textile mills. (Indeed, a U.S. survey of the damage, not released to the press, found that residential areas bore the brunt of the bomb, with less than 10% of the city's manufacturing, transportation, and storage facilities damaged.)On Guam, weaponeer William S. Parsons and Enola Gay pilot Paul Tibbets calmly answered reporters' questions, limiting their remarks to what they had observed after the bomb exploded. Asked how he felt about the people down below at the time of detonation, Parsons said that he experienced only relief that the bomb had worked and might be "worth so much in terms of shortening the war."

Almost without exception newspaper editorials endorsed the use of the bomb against Japan. Many of them sounded the theme of revenge first raised in the Truman announcement. Most of them emphasized that using the bomb was merely the logical culmination of war. "However much we deplore the necessity," the Washington Post observed, "a struggle to the death commits all combatants to inflicting a maximum amount of destruction on the enemy within the shortest span of time." The Post added that it was "unreservedly glad that science put this new weapon at our disposal before the

end of the war."

Referring to American leaders, the Chicago Tribune commented: "Being merciless, they were merciful." A drawing in the same newspaper pictured a dove of peace flying over Japan, an atomic bomb in its beak.

Published on August 07, 2014 10:57

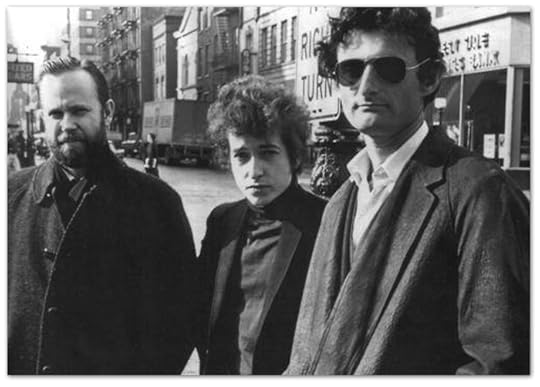

His Back Pages

What a week for NYT's Sam Tanenhaus--he slams Rick Perlstein in The Atlantic, then offers this preview of much-rumored upcoming memoir of longtime famed Bob Dylan pal, whose face and name I've known for, what, nearly fifty years (ouch). Among tidbits: Dylan leaving folk days behind, seemingly in one day, after hearing The Beatles on the radio on an epic road trip--then turning the Beatles on to weed (not a new story but with fresh image of Bob himself passing out). Great bit on Dylan's wife pouring out heart on divorce with "Blood on the Tracks" playing and Bob walking in. And so on.

What a week for NYT's Sam Tanenhaus--he slams Rick Perlstein in The Atlantic, then offers this preview of much-rumored upcoming memoir of longtime famed Bob Dylan pal, whose face and name I've known for, what, nearly fifty years (ouch). Among tidbits: Dylan leaving folk days behind, seemingly in one day, after hearing The Beatles on the radio on an epic road trip--then turning the Beatles on to weed (not a new story but with fresh image of Bob himself passing out). Great bit on Dylan's wife pouring out heart on divorce with "Blood on the Tracks" playing and Bob walking in. And so on.

Published on August 07, 2014 08:23

That Rocket Launcher

Interesting and "balanced" background report by guy from Indian TV who shot that rocket launcher and firing next to his hotel. He says it's not quite the "ah-hah" moment claimed by many.

There is one final risk associated with stories like this -- and one that often keeps journalists awake at night -- is that our report could end up serving the goals of propagandists. To let this fear cripple our work would amount to erasing the difference between journalism and propaganda.

We chose to not let that happen. We did not turn our sight away from a rocket launch site, just as we did not flinch while filming the dead piled up in Rafah's morgues.

Published on August 07, 2014 07:42

Confirming Israeli Attacks on 'Health Workers'

Amnesty International just posted report it titles "Mounting Evidnece of Deliberate Attacks on Gaza Health Workers By Israeli Army." Of course, we've all seen the videos and photos and tally of number of medics, doctors and ambulance workers killed. Now:

An immediate investigation is needed into mounting evidence that the Israel Defense Forces launched apparently deliberate attacks against hospitals and health professionals in Gaza, which have left six medics dead, said Amnesty International as it released disturbing testimonies from doctors, nurses, and ambulance personnel working in the area.

“The harrowing descriptions by ambulance drivers and other medics of the utterly impossible situation in which they have to work, with bombs and bullets killing or injuring their colleagues as they try to save lives, paint a grim reality of life in Gaza,” said Philip Luther, Middle East and North Africa Director at Amnesty International.

“Even more alarming is the mounting evidence that the Israeli army has targeted health facilities or professionals. Such attacks are absolutely prohibited by international law and would amount to war crimes. They only add to the already compelling argument that the situation should be referred to the International Criminal Court.”

Published on August 07, 2014 07:15

When the U.S. Failed to Draw a 'Red Line' on Use of Nuclear Weapons

See my recent book

Atomic Cover-up

, my piece at The Nation on that, and my popular brief video below.

Published on August 07, 2014 06:52

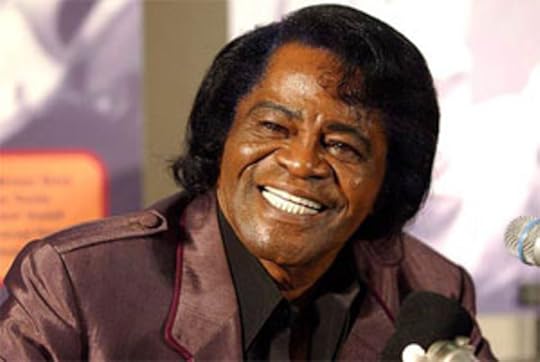

Get On Down

Man who worked for James Brown at two of his radio stations in the late-'60s and early '70s in article calls him not the hardest working man in show business but biggest "asshole" in show business. The other side of the new Get On Up flick. From trailers and reviews, it seems film paints Brown as a true "progressive" but my memory from those years--beyond the important"I'm Black and I'm Proud"-- has him as mainly an establishment Democrat who backed the war and then a Nixon Republican. "James Brown’s relationship to the Black people he touched most directly – those who worked for him – was cruel, petty, and contemptuous. South Carolina-born actor Chadwick Boseman's performance sometimes made me think I was looking at a ghost – except that Boseman is too tall and Brown’s malice was inseparable from his short stature." h/t @Bbedway

Man who worked for James Brown at two of his radio stations in the late-'60s and early '70s in article calls him not the hardest working man in show business but biggest "asshole" in show business. The other side of the new Get On Up flick. From trailers and reviews, it seems film paints Brown as a true "progressive" but my memory from those years--beyond the important"I'm Black and I'm Proud"-- has him as mainly an establishment Democrat who backed the war and then a Nixon Republican. "James Brown’s relationship to the Black people he touched most directly – those who worked for him – was cruel, petty, and contemptuous. South Carolina-born actor Chadwick Boseman's performance sometimes made me think I was looking at a ghost – except that Boseman is too tall and Brown’s malice was inseparable from his short stature." h/t @Bbedway

Published on August 07, 2014 05:34

August 6, 2014

When Truman Failed to Pause in 1945--and the War Crime That Followed

By August 7, 1945, President Truman, while still at sea returning from Potsdam, had been fully briefed on the first atomic attack against a large city in Japan the day before. In announcing it, he had labeled Hiroshima simply a "military base," but he knew better, and within hours of the blast he had been fully informed about the likely massive toll on civilians (probably 100,000), mainly women and children, as we had planned. Despite this--and news that the Soviets, as planned, were about to enter the war against Japan--Truman did not order a delay in the use of the second atomic bomb to give Japan a chance to assess, reflect, and surrender.

After all, by this time, Truman (as recorded in his diary and by others) was well aware that the Japanese were hopelessly defeated and seeking terms of surrender--and he had, just two weeks earlier, written "Fini Japs" in his diary when he learned that the Russians would indeed attack around August 7. Yet Truman, on this day, did nothing, and the second bomb rolled out, and would be used against Nagasaki, killing perhaps 90,000 more, only a couple hundred of them Japanese troops, on August 9. That's why many who reluctantly support or at least are divided about the use of the bomb against Hiroshima consider Nagasaki a war crime--in fact, the worst one-day war crime in human history.

Below, a piece I wrote not long ago. One of my books on the atomic bombings describes my visit to Nagasaki at length.

*

Few journalists bother to visit Nagasaki, even though it is one of only two cities in the world to "meet the atomic bomb," as some of the survivors of that experience, 68 years ago this week, put it. It remains the Second City, and "Fat Man" the forgotten bomb. No one in America ever wrote a bestselling book called Nagasaki, or made a film titled Nagasaki, Mon Amour. "We are an asterisk," Shinji Takahashi, a sociologist in Nagasaki, once told me, with a bitter smile. "The inferior A-Bomb city."

Yet in many ways, Nagasaki is the modern A-Bomb city, the city with perhaps the most meaning for us today. For one thing, when the plutonium bomb exploded above Nagasaki it made the uranium-type bomb dropped on Hiroshima obsolete.

Yet in many ways, Nagasaki is the modern A-Bomb city, the city with perhaps the most meaning for us today. For one thing, when the plutonium bomb exploded above Nagasaki it made the uranium-type bomb dropped on Hiroshima obsolete.

And then there's this. "The rights and wrongs of Hiroshima are debatable," Telford Taylor, the chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials, once observed, "but I have never heard a plausible justification of Nagasaki" -- which he labeled a war crime. Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., who experienced the firebombing of Dresden at close hand, said much the same thing. "The most racist, nastiest act by this country, after human slavery, was the bombing of Nagasaki," he once said. "Not of Hiroshima, which might have had some military significance. But Nagasaki was purely blowing away yellow men, women, and children. I'm glad I'm not a scientist because I'd feel so guilty now."

A beautiful city dotted with palms largely built on terraces surrounding a deep harbor--the San Francisco of Japan -- Nagasaki has a rich, bloody history, as any reader of Shogun knows. Three centuries before Commodore Perry came to Japan, Nagasaki was the country's gateway to the west. The Portuguese and Dutch settled here in the 1500s. St. Francis Xavier established the first Catholic churches in the region in 1549, and Urakami, a suburb of Nagasaki, became the country's Catholic center. Thomas Glover, one of the first English traders here, supplied the modern rifles that helped defeat the Tokugawa Shogunate in the 19th century.

Glover's life served as a model for the story of Madame Butterfly, and Nagasaki is known in many parts of the world more for Butterfly than for the bomb. In Puccini's opera, Madame Butterfly, standing on the veranda of Glover's home overlooking the harbor (see left), sings, "One fine day, we'll see a thread of smoke arising.... " If she could have looked north from the Glover mansion, now Nagasaki's top tourist attraction, on August 9, 1945, she would have seen, two miles in the distance, a thread of smoke with a mushroom cap.

By 1945, Nagasaki had become a Mitsubishi company town, turning out ships and armaments for Japan's increasingly desperate war effort. Few Japanese soldiers were stationed here, and only about 250 of them would perish in the atomic bombing. It was still the Christian center in the country, with more than 10,000 Catholics among its 250,000 residents. Most of them lived in the outlying Urakami district, the poor part of town, where a magnificent cathedral seating 6000 had been built.

At 11:02 a.m. on August 9, 1945, "Fat Man" was detonated more than a mile off target, almost directly over the Urakami Cathedral, which was nearly leveled, killing dozens of worshippers waiting for confession. Concrete roads in the valley literally melted.

While Urakami suffered, the rest of the city caught a break. The bomb's blast boomed up the valley destroying everything in its path but didn't quite reach the congested harbor or scale the high ridge to the Nakashima valley. Some 35,000 perished instantly, with another 50,000 or more fated to die afterwards. The plutonium bomb hit with the force of 22 kilotons, almost double the uranium bomb's blast in Hiroshima.

If the bomb had exploded as planned, directly over the Mitsubishi shipyards, the death toll in Nagasaki would have made Hiroshima, in at least one important sense, the Second City. Nothing would have escaped, perhaps not even the most untroubled conscience half a world away.

Hard evidence to support a popular theory that the chance to "experiment" with the plutonium bomb was the major reason for the bombing of Nagasaki remains sketchy but still one wonders (especially when visiting the city, as I recount in my new book) about the overwhelming, and seemingly thoughtless, impulse to automatically use a second atomic bomb even more powerful than the first.

Criticism of the attack on Nagasaki has centered on the issue of why Truman did not step in and stop the second bomb after the success of the first to allow Japan a few more days to contemplate surrender before targeting another city for extinction. In addition, the U.S. knew that its ally, the Soviet Union, would join the war within hours, as previously agreed, and that the entrance of Japan's most hated enemy, as much as the Hiroshima bomb, would likely speed the surrender ("fini Japs" when the Russians declare war, Truman had predicted in his diary). If that happened, however, it might cost the U.S. in a wider Soviet claim on former Japanese conquests in Asia. So there was much to gain by getting the war over before the Russians advanced. Some historians have gone so far as state that the Nagasaki bomb was not the last shot of World War II but the first blow of the Cold War.

Whether this is true or not, there was no presidential directive specifically related to dropping the second bomb. The atomic weapons in the U.S. arsenal, according to the July 2, 1945 order, were to be used "as soon as made ready," and the second bomb was ready within three days of Hiroshima. Nagasaki was thus the first and only victim of automated atomic warfare.

In one further irony, Nagasaki was not even on the original target list for A-bombs but was added after Secretary of War Henry Stimson objected to Kyoto. He had visited Kyoto himself and felt that destroying Japan's cultural capital would turn the citizens against America in the aftermath. Just like that, tens of thousands in one city were spared and tens of thousands of others elsewhere were marked for death.

General Leslie Groves, upon learning of the Japanese surrender offer after the Nagasaki attack, decided that the "one-two" strategy had worked, but he was pleased to learn the second bomb had exploded off the mark, indicating "a smaller number of casualties than we had expected." But as historian Martin Sherwin has observed, "If Washington had maintained closer control over the scheduling of the atomic bomb raids the annihilation of Nagasaki could have been avoided." Truman and others simply did not care, or to be charitable, did not take care.

That's one reason the US suppressed all film footage shot in Nagasaki and Hiroshima for decades (which I probe in my book and ebook Atomic Cover-up).

After hearing of Nagasaki, however, Truman quickly ordered that no further bombs be used without his express permission, to give Japan a reasonable chance to surrender--one bomb, one city, and seventy thousand deaths too late. When they'd learned of the Hiroshima attack, the scientists at Los Alamos generally expressed satisfaction that their work had paid off. But many of them took Nagasaki quite badly. Some would later use the words "sick" or "nausea" to describe their reaction.

As months and then years passed, few Americans denounced as a moral wrong the targeting of entire cities for extermination. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, however, declared that we never should have hit Japan "with that awful thing." The left-wing writer Dwight MacDonald cited America's "decline to barbarism" for dropping "half-understood poisons" on a civilian population. His conservative counterpart, columnist and magazine editor David Lawrence, lashed out at the "so-called civilized side" in the war for dropping bombs on cities that kill hundreds of thousands of civilians.

However much we rejoice in victory, he wrote, "we shall not soon purge ourselves of the feeling of guilt which prevails among us.... What a precedent for the future we have furnished to other nations even less concerned than we with scruples or ideals! Surely we cannot be proud of what we have done. If we state our inner thoughts honestly, we are ashamed of it."

Greg Mitchell's books and ebooks include "Hollywood Bomb" and "Atomic Cover-Up: Two U.S. Soldiers, Hiroshima & Nagasaki, and The Greatest Movie Never Made." Email: epic1934@aol.com

After all, by this time, Truman (as recorded in his diary and by others) was well aware that the Japanese were hopelessly defeated and seeking terms of surrender--and he had, just two weeks earlier, written "Fini Japs" in his diary when he learned that the Russians would indeed attack around August 7. Yet Truman, on this day, did nothing, and the second bomb rolled out, and would be used against Nagasaki, killing perhaps 90,000 more, only a couple hundred of them Japanese troops, on August 9. That's why many who reluctantly support or at least are divided about the use of the bomb against Hiroshima consider Nagasaki a war crime--in fact, the worst one-day war crime in human history.

Below, a piece I wrote not long ago. One of my books on the atomic bombings describes my visit to Nagasaki at length.

*

Few journalists bother to visit Nagasaki, even though it is one of only two cities in the world to "meet the atomic bomb," as some of the survivors of that experience, 68 years ago this week, put it. It remains the Second City, and "Fat Man" the forgotten bomb. No one in America ever wrote a bestselling book called Nagasaki, or made a film titled Nagasaki, Mon Amour. "We are an asterisk," Shinji Takahashi, a sociologist in Nagasaki, once told me, with a bitter smile. "The inferior A-Bomb city."

Yet in many ways, Nagasaki is the modern A-Bomb city, the city with perhaps the most meaning for us today. For one thing, when the plutonium bomb exploded above Nagasaki it made the uranium-type bomb dropped on Hiroshima obsolete.

Yet in many ways, Nagasaki is the modern A-Bomb city, the city with perhaps the most meaning for us today. For one thing, when the plutonium bomb exploded above Nagasaki it made the uranium-type bomb dropped on Hiroshima obsolete.And then there's this. "The rights and wrongs of Hiroshima are debatable," Telford Taylor, the chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials, once observed, "but I have never heard a plausible justification of Nagasaki" -- which he labeled a war crime. Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., who experienced the firebombing of Dresden at close hand, said much the same thing. "The most racist, nastiest act by this country, after human slavery, was the bombing of Nagasaki," he once said. "Not of Hiroshima, which might have had some military significance. But Nagasaki was purely blowing away yellow men, women, and children. I'm glad I'm not a scientist because I'd feel so guilty now."

A beautiful city dotted with palms largely built on terraces surrounding a deep harbor--the San Francisco of Japan -- Nagasaki has a rich, bloody history, as any reader of Shogun knows. Three centuries before Commodore Perry came to Japan, Nagasaki was the country's gateway to the west. The Portuguese and Dutch settled here in the 1500s. St. Francis Xavier established the first Catholic churches in the region in 1549, and Urakami, a suburb of Nagasaki, became the country's Catholic center. Thomas Glover, one of the first English traders here, supplied the modern rifles that helped defeat the Tokugawa Shogunate in the 19th century.

Glover's life served as a model for the story of Madame Butterfly, and Nagasaki is known in many parts of the world more for Butterfly than for the bomb. In Puccini's opera, Madame Butterfly, standing on the veranda of Glover's home overlooking the harbor (see left), sings, "One fine day, we'll see a thread of smoke arising.... " If she could have looked north from the Glover mansion, now Nagasaki's top tourist attraction, on August 9, 1945, she would have seen, two miles in the distance, a thread of smoke with a mushroom cap.

By 1945, Nagasaki had become a Mitsubishi company town, turning out ships and armaments for Japan's increasingly desperate war effort. Few Japanese soldiers were stationed here, and only about 250 of them would perish in the atomic bombing. It was still the Christian center in the country, with more than 10,000 Catholics among its 250,000 residents. Most of them lived in the outlying Urakami district, the poor part of town, where a magnificent cathedral seating 6000 had been built.

At 11:02 a.m. on August 9, 1945, "Fat Man" was detonated more than a mile off target, almost directly over the Urakami Cathedral, which was nearly leveled, killing dozens of worshippers waiting for confession. Concrete roads in the valley literally melted.

While Urakami suffered, the rest of the city caught a break. The bomb's blast boomed up the valley destroying everything in its path but didn't quite reach the congested harbor or scale the high ridge to the Nakashima valley. Some 35,000 perished instantly, with another 50,000 or more fated to die afterwards. The plutonium bomb hit with the force of 22 kilotons, almost double the uranium bomb's blast in Hiroshima.

If the bomb had exploded as planned, directly over the Mitsubishi shipyards, the death toll in Nagasaki would have made Hiroshima, in at least one important sense, the Second City. Nothing would have escaped, perhaps not even the most untroubled conscience half a world away.

Hard evidence to support a popular theory that the chance to "experiment" with the plutonium bomb was the major reason for the bombing of Nagasaki remains sketchy but still one wonders (especially when visiting the city, as I recount in my new book) about the overwhelming, and seemingly thoughtless, impulse to automatically use a second atomic bomb even more powerful than the first.

Criticism of the attack on Nagasaki has centered on the issue of why Truman did not step in and stop the second bomb after the success of the first to allow Japan a few more days to contemplate surrender before targeting another city for extinction. In addition, the U.S. knew that its ally, the Soviet Union, would join the war within hours, as previously agreed, and that the entrance of Japan's most hated enemy, as much as the Hiroshima bomb, would likely speed the surrender ("fini Japs" when the Russians declare war, Truman had predicted in his diary). If that happened, however, it might cost the U.S. in a wider Soviet claim on former Japanese conquests in Asia. So there was much to gain by getting the war over before the Russians advanced. Some historians have gone so far as state that the Nagasaki bomb was not the last shot of World War II but the first blow of the Cold War.

Whether this is true or not, there was no presidential directive specifically related to dropping the second bomb. The atomic weapons in the U.S. arsenal, according to the July 2, 1945 order, were to be used "as soon as made ready," and the second bomb was ready within three days of Hiroshima. Nagasaki was thus the first and only victim of automated atomic warfare.

In one further irony, Nagasaki was not even on the original target list for A-bombs but was added after Secretary of War Henry Stimson objected to Kyoto. He had visited Kyoto himself and felt that destroying Japan's cultural capital would turn the citizens against America in the aftermath. Just like that, tens of thousands in one city were spared and tens of thousands of others elsewhere were marked for death.

General Leslie Groves, upon learning of the Japanese surrender offer after the Nagasaki attack, decided that the "one-two" strategy had worked, but he was pleased to learn the second bomb had exploded off the mark, indicating "a smaller number of casualties than we had expected." But as historian Martin Sherwin has observed, "If Washington had maintained closer control over the scheduling of the atomic bomb raids the annihilation of Nagasaki could have been avoided." Truman and others simply did not care, or to be charitable, did not take care.

That's one reason the US suppressed all film footage shot in Nagasaki and Hiroshima for decades (which I probe in my book and ebook Atomic Cover-up).

After hearing of Nagasaki, however, Truman quickly ordered that no further bombs be used without his express permission, to give Japan a reasonable chance to surrender--one bomb, one city, and seventy thousand deaths too late. When they'd learned of the Hiroshima attack, the scientists at Los Alamos generally expressed satisfaction that their work had paid off. But many of them took Nagasaki quite badly. Some would later use the words "sick" or "nausea" to describe their reaction.

As months and then years passed, few Americans denounced as a moral wrong the targeting of entire cities for extermination. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, however, declared that we never should have hit Japan "with that awful thing." The left-wing writer Dwight MacDonald cited America's "decline to barbarism" for dropping "half-understood poisons" on a civilian population. His conservative counterpart, columnist and magazine editor David Lawrence, lashed out at the "so-called civilized side" in the war for dropping bombs on cities that kill hundreds of thousands of civilians.

However much we rejoice in victory, he wrote, "we shall not soon purge ourselves of the feeling of guilt which prevails among us.... What a precedent for the future we have furnished to other nations even less concerned than we with scruples or ideals! Surely we cannot be proud of what we have done. If we state our inner thoughts honestly, we are ashamed of it."

Greg Mitchell's books and ebooks include "Hollywood Bomb" and "Atomic Cover-Up: Two U.S. Soldiers, Hiroshima & Nagasaki, and The Greatest Movie Never Made." Email: epic1934@aol.com

Published on August 06, 2014 22:30