Brian J. Walsh's Blog, page 36

December 5, 2013

Jesus, Obama and de Certeau: Redemptive Tactics in the Security State

It’s a good thing that the whole Jesus thing didn’t happen in the 21st century.

November 21, 2013

Pale Reflection. Black Mirror.

by Andrew Stephens-Rennie

A meditation inspired by Luke 20:27-38 and Arcade Fire’s Reflektor.

Where were we again?

Trapped in a prison, a prism of light

Alone in the darkness, a darkness of white

Oh right. That was it.

Entre la nuit, la nuit et l’aurore

Entre le royaume des vivants et des morts

Between the night, the night and the dawn, between the kingdom of the living and the dead, that’s where we were. Imprisoned somewhere entre la nuit et l’aurore, between the kingdom of the living and the dead. And the persistent question on our lips, the persistent question on our hearts: where is God in the midst of all this?

Watching, waiting, hoping and praying for the dawn to come, for new life, we find ourselves caught up in the contradictions of daily existence. There are days we’re on top. Others we’re in the pits of hell. There is darkness, and there is the promise of dawn.

The Sadducees, it seems, are there to expose Jesus as a fraud. They seem keen on catching him up in his inconsistent testimony. They’ve written him off, and this is one last question to hammer the point home:

In the resurrection, whose wife will this woman be? And Jesus, quoting Win Butler might find himself saying:

Thought you were praying to the resurrector

Turns out it was just a reflektor.

Jesus pushes back, redirects, and turns it on them. Why do you think that God is limited by your understanding of the divine? Trapped in this prison, your prism and lens. Trapped in your self-imposed prison, you’ve appointed yourself judge, jury and executioner for those without the right answers. But this is the God of the living, not of the dead. This God is more than a reflection of your finite mind.

And the question. The Sadducees prompt the question for you, for me, for all of us: how often do we try to limit God within the prisons our own enlightened understanding? How often do we put Jesus on trial?

And how often do we find ourselves praying, not to the resurrector, but to our own pale reflections in the black mirror?

Filed under: Andrew Stephens-Rennie Tagged: Arcade Fire, Black Mirror, Reflektor, Sadducees

Pale Reflection. Black Mirror.

Where were we again?

November 18, 2013

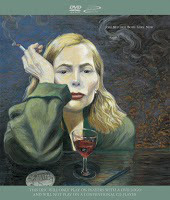

Joni and Jesus: Poets of Endings

by Brian Walsh

[On Sunday, November 17, the Wine Before Breakfast community joined our friends at the Church of the Redeemer, Toronto, for a service featuring the music of Joni Mitchell. The texts for the evening were Psalm 98 and the beginning of the apocalyptic discourse in Luke 21.5-19. The Mitchell songs performed were "Woodstock", "River", "Shadows and Light", "Slouching Towards Bethlehem", "Passion Play (When all the Slaves are Free)", "Both Sides Now", "A Case of You", "The Circle Game", and "Big Yellow Taxi". While this sermon makes allusions to most of these songs, the primary point of reference is "Slouching Towards Bethlehem." When that song, based on William Butler Yeats' poem, "The Second Coming," is performed just before the reading of this apocalyptic gospel text, it isn't sure whether the song interprets the gospel, or the gospel interprets the song.]

When things fall apart,

when the centre does not hold,

there will always be a blood dimmed tide,

loosed upon the world.

When nothing is sacred,

and innocence is drowned in anarchy,

then the best will simply lack any conviction,

while the worse will be full of passion without mercy.

It is never pretty when things fall apart.

And there is no cheap celebration when the centre cannot hold.

Maybe things should fall apart.

Maybe it was all a house of cards.

Maybe it was all built on lies.

And maybe the centre could not hold,

because it was a false centre,

rooted in idolatry.

But when you come to the end of things,

it doesn’t really matter how justified

and how necessary that ending might be,

it will always be violent.

Joni Mitchell is a poet of endings.

And it is no wonder that she is drawn

to William Butler Yeats’ apocalyptic poem,

“The Second Coming.”

Many have cited Yeats.

The phrase, ‘the centre did not hold’

has almost been a mantra of postmodernity,

an apt description of the aspirations of modern culture.

But few have taken Yeats’ poem to such new heights

or, for that matter, new depths,

as Joni Mitchell.

Joni Mitchell is a poet of endings, I say.

A poet trying to get her soul free.

A poet who wants to lose the smog,

who knows that the time is ripe

for endings, and maybe, for new beginnings.

But she is not a poet of cheap hope.

She knows that we’ve been caught up in the devil’s bargain.

She knows the shadows of every picture,

the prevalence of blindness over sight,

the dominance of night over day,

the devastating power of wrong over right.

She knows the threat of all things,

the contradictions of life,

the tension between cruelty and delight,

the penchant to break the ever-present and ever-lasting laws.

Joni Mitchell knows that things fall apart

and the centre cannot hold.

And she knows that none of this is innocent,

none of it is safe.

We might well be on a carousel of time,

the seasons may well go round and round,

but this circle game can be deadly.

When you pave paradise and put up a parking lot,

something dies:

an eco-system,

a sense of place,

a relationship.

So what happens when things fall apart,

when the centre cannot hold,

when we are lost in spiritual disconnection

and cultural disintegration?

Well, write both Yeats and Mitchell,

“surely some revelation is at hand,

surely it’s the second coming.”

Surely this ending, this falling apart,

will call forth a new revelation,

nothing less than a second coming.

But a second coming of what?

Wrath … Yes, wrath.

The blood-dimmed tide that is loosed upon the world

is nothing less than wrath finally taking form;

nothing less than the awakening of a rough beast, in the form of a sphinx,

opening its eyes, vexed by the nightmare of 20 centuries,

coming in judgement.

This beast slouches towards Bethlehem to be born,

but this is no Christmas story.

The hour has come and it is a terrible hour,

an hour of violence,

an hour of devastating endings.

Thanks Joni.

That’s just what we all needed at the end of the last two weeks in Toronto.

No late night humour from Joni Mitchell, here.

Just a deepening of the crisis.

Thanks Joni.

That’s just what we all needed in the wake

the humanitarian crisis in the Philippines.

Thanks Joni.

That’s just what we need as we face Canadian irresponsibility

in the face of the crisis of climate change.

Thanks Joni.

Joni Mitchell is a poet of endings.

So it is not surprising that Jesus, the Bible and faith

show up so often in her work.

Never before, she sings,

was a man so kind,

so redeeming.

This heart healer,

this magical physician,

this diver of the heart,

this one who prays,

thy kingdom come,

thy will be done.

Yes, there does seem to be some affinity between Joni and Jesus.

You see, they are both poets of endings.

Folks in Jesus’ time knew that the Temple was the centre of it all.

Here this wonderful architecture of beautiful stones;

this place dedicated to God;

this place where the everlasting laws were proclaimed;

this place where the sacred resides in the holy of holies;

this place where innocence is restored;

this place of mercy;

this place of ceremony and liturgy.

Surely, this is the place of revelation.

Surely, this is the place that holds it all together.

Surely, this is nothing less than the centre of the world!

But Jesus says,

things fall apart,

the centre cannot hold.

It is all coming down,

not one stone will be left on another.

And when the centre does not hold,

a blood dimmed tide is loosed upon the world.

There will be wars and insurrections,

nation will rise against nation;

nothing less than geo-political collapse,

and a loosening of violence.

There will be great earthquakes,

famine and plagues, and dreadful portents;

a wide-ranging ecological collapse,

and there will be great suffering.

Endings never come easily.

Not in geo-politics,

not at city hall,

not in vast global economic structures,

not in the intricately interconnected eco-systems of the world,

and not in my life or your life.

Of course, both Joni and Jesus are talking here about

the endings of cultural epochs,

of systems of meaning,

of structures of oppression,

of civilizations,

their ideologies,

their stories,

and their idolatries.

But we all know that no endings come easily.

When things fall apart,

in your marriage,

in your family,

in your relationships,

deeply within yourself;

when the centre does not hold,

and you don’t know who you are anymore,

you don’t know what matters and what doesn’t,

you don’t know what you believe,

you don’t know who you can trust;

then violence can be so near to hand,

lashing out at others,

letting lose with a passion devoid of mercy,

anger and alienation,

and maybe even violence to yourself.

Many of us know that beast arising from the desert,

many of us know of earthquakes in our own lives,

many of us are the walking wounded,

and the beast is always just around the corner.

Joni hopes and hopes,

as if by her weak faith,

that the spirit of this world would rise and heal.

Jesus isn’t so keen on the spirit of this world.

Jesus figures that the spirit of this world just might be the problem.

The spirit of this world is what conjures up the beast,

and this spirit, he says,

is a spirit of persecution,

a spirit of violence,

a spirit of betrayal.

And so he offers a different path.

Testify, he says.

Tell a different story.

Sing a new song.

In the face of the violence, bear witness.

And trust, he says.

Trust that in the midst of it all, this heart healer will be with you.

Trust that in the face of the anarchy of it all coming apart,

there is a wisdom that is deeper than the foolishness of the world.

Trust that the nightmare of the last twenty centuries,

the nightmare of the last two weeks,

indeed, the nightmare that haunts you every night and every day,

can be transformed into the dreams of the Kingdom of God.

Trust and pray,

Thy kingdom come.

Thy will be done.

In such trust, Jesus says,

not a hair of your head will perish.

In such trust, Jesus says,

you will have life,

you will regain your souls.

And in that trust,

maybe you’ll be able to see the victory of God

in which blindness gives way to sight,

day flowers out of the night,

and righteousness overcomes all wrong.

And maybe in praying,

thy kingdom come,

thy will be done,

you will find the voice to join all the earth in a song of praise,

and things that once were falling apart

will come together anew in songs of joy.

May it be so, dear friends, may it be so.

May this be a second coming,

not slouching towards Bethlehem,

but marching towards the New Jerusalem.

Amen.

Filed under: Brian Walsh, Luke, Psalms, Season after Pentecost, Sermons, Wine Before Breakfast Tagged: Brian Walsh, Church of the Redeemer, Faith, Hope, Joni Mitchell, Sermons, William Butler Yeats

November 17, 2013

Joni and Jesus: Poets of Endings

November 5, 2013

God Bless Toronto: The Piety of Rob Ford

by Brian Walsh

“God bless the people of Toronto.”

So ended Mayor Rob Ford’s apology before the press assembled outside his office this afternoon.

And there were audible giggles and laughter from the audience.

He had just said,

“I sincerely, sincerely, sincerely apologize.”

Followed by,

“God bless the people of Toronto.”

Then came the laughter.

Incredible rudeness from the press?

An anti-religious secularist arrogance mocking religious sentiment?

Laughter at the only too obvious allusion to another discredited leader who was always invoking the blessing of God on America?

Or just the involuntary laughter at this cheap faux spirituality at the end of a faux apology?

After a threefold ‘sincerely’ maybe the insincerity of this little bit of piety at the end of it all was just too much.

Let’s be clear about something here.

Rob Ford was clearly embarrassed and it was incredibly difficult for him to make this apology. He said this was one of the hardest things that he has ever done. He said repeatedly how very, very, very sorry he is.

But what was he sorry for?

He was sorry that he had been a drunk.

He was sorry that he had smoked crack.

He was sorry that he kept his substance abuse from his family.

And all of this was very hard for him.

But the truth of the matter is that he is sorry that he got caught.

And if he was really sorry, if he really wanted to come clean with the people of Toronto, if he really wanted to begin to address the damage of what he had done, then he had a more important apology, indeed a more important confession, to make.

He should be sorry that he lied to the people of Toronto.

He should be sorry that he engaged in a cover up.

He should be sorry that his closest associate in all of this has been charged with extortion.

You see, the damage done by his substance abuse, while significant, pales in comparison to the damage done to the public trust by his deceit.

And then he has the audacity, the spiritual hypocrisy, the false piety to say,

“God bless the people of Toronto.”

How exactly might God do that?

What would God’s blessing look like if Rob Ford’s little prayer was to be answered?

Maybe it would mean that we would have politicians who did not betray the public trust.

Maybe it would mean that we would have a mayor who did not lie to us.

Maybe it would mean that honesty and transparency would replace cover ups.

Maybe it would mean a civil discourse which did not demonize one’s political opponents.

Maybe it would mean that we would have a vision for the common good that went beyond ‘saving the tax payer’s money.’

The City of Toronto has been living under a curse.

Maybe that curse could be lifted and we could start to make some steps towards blessing, if Rob Ford would do the right thing, the true thing, the honest thing.

It is time for Rob Ford to resign.

Of course we all know that this will not happen.

So please, please, please, Mr. Ford,

leave God out of this.

Do not insult the people of faith in this city for whom the name of God is sacred.

Do not take this God’s name in vain.

Do not insincerely invoke the name of God as a spiritual coating for your own deceit.

Filed under: Brian Walsh, Politics, Toronto Tagged: Brian Walsh, God, Rob Ford, Toronto

November 3, 2013

Cloud of Witnesses :: Remembering Josephine Butler

Josephine Butler (1828-1906) | Colossians 1:15-20

by Andrew Stephens-Rennie

Bright, blinding lights ahead.

You stare. Transfixed.

Unable to move, unable to see, unable to comprehend

All that is before you

All that you’re taking in

All that this could be.

All that this might mean.

Bright, blinding lights ahead

And I struggle to avert my gaze.

Transfixed, uncomfortable, unnerved.

Desiring deeply to move from this place

To look away, to close my eyes, never to be confronted

With all that is before me

With all that I’ve taken in

With all that this could be

With all that this might mean

For he is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and for him.

And I stand there transfixed, unable to move, unable to see, unable to comprehend the vastness, the implications of what this might mean. Unable to wrap my mind around what it might mean for such a thing to be true.

This one. This man. This Jesus. Conceived by the power of the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary. This very same Jesus who suffered under Pontius Pilate. The very same one who was crucified, died, and was buried. This one. The image of an invisible God. The firstborn of all creation. The one who has been raised from the dead.

If you’re anything like me, and I don’t know if you are, you stop. You stare. Transfixed. Excited. Worried. Unable to comprehend what this might mean.

You stop here in the heart of Colossae, an outpost of the Roman Empire. In the heart of East Vancouver.

You stop, transfixed.

Transfixed by what, in this world, sounds like fanatical heresy. Unable to move, for fear of being accused of treason. Worried to look, for fear of being named a co-conspirator. Unwilling to comprehend the power and the extent of this claim. Full comprehension might mean the end.

The end of life as we know it.

The end of whatever comforts we’ve known.

The end of that dream of a quiet life in the country,

the suburbs, or

that up-and-coming part of Fraser (I hear it’s the new Main Street).

Transfixed and terrified by this terrific treasonous treatise, this bold proclamation that God is God and Caesar is not. Leaking the Empire’s deepest, darkest secrets, its underbelly weakness, you’ve seen Snowden’s insurrectionist cable, a note slipped under the table with the words to this subversive freedom song.

For he is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and for him.

The world, and all that is in it, was created in and through Jesus the Christ.

Not in and through Caesar, Obama, Putin or Harper.

Not in Mulcair, May or even JT – whether we’re talking Trudeau or Timberlake.

It’s not in Sean Parker or Mark Zuckerberg that we live and move and have our being – no matter what stake they have in your digital image.

The world and all that’s in it. All that is, seen and unseen, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers. All of these things have been created in and through Jesus Christ. All are subservient to their creator no matter what they say. And all are united in the oneness of God’s creation, for

He himself is before all things, and in him all things hold together. He is the head of the body, the church; he is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead, so that he might come to have first place in everything.

Eye on the prize, we’ve fixed our eyes on this one, God’s firstborn son, the one who was, and is, and is to come.

For Josephine Butler, a well-known British social activist who lived from 1828-1906, it was this God revealed in Jesus Christ that was the source and object of all worship. No matter what the cost, no matter the opposition around her, she fought tirelessly, fueled by faith, unable to avert her gaze from Christ and the needs of God’s children, especially those shoved carelessly to the margins.

And though the battles were long and hard, though they took a great toll on her health, Josephine Butler remained faithful to Jesus. Butler’s story is a well-known feminist tale, but little has been written about her deep-rooted evangelical Christian faith.

Apparently, in this world, that’s just confusing.

As anyone with access to Wikipedia can tell you, Josephine was the seventh child of John Grey and Hannah Annett. Her father, John, was a cousin of Prime Minister Charles Grey, under whose administration slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1833, all the while sipping his own special blend of tea.

But this isn’t about John or Earl Grey, although they too are a part of our cloud of witnesses. This is about Josephine Butler and her faithful response to the Image of the Invisible God.

Josephine’s tireless activism focused almost exclusively on advocacy for the rights of women in an era where such rights were less than guaranteed. She focused her concern and her advocacy primarily on the plight of women who had been forced to prostitute as a means of economic survival. Her most famous campaign was for the repealing of the Contagious Diseases Act, an act that gave the state the powers to seize and arrest women suspected of having (what we might call today) Sexually Transmitted Infections, but didn’t worry so much about the men whose use and misuse of these prostituted women was the real cause of pathological and social contagion.

Her activism, rooted in an evangelical Christian faith, pushed the boundaries of what might be considered proper. Her zeal for this work amongst prostituted women was formed in a family deeply engaged in another abolitionist movement.

Reflecting on a lifetime of advocacy, Butler wrote:

When my father spoke to…his children, of the great wrong of slavery, I have felt his powerful frame tremble and his voice would break. You can believe, that at that time sad and tragical recitals came to us from first sources of the hideous wrong inflicted on negro men and women.

Josephine’s earliest feminist instincts were awakened by tales of slavery. For her, prostitution and slavery were deeply intertwined. The connections between money, greed, and power – specifically male power and privilege – were self-evident. And while some of our churches are still today fighting about the proper hierarchy of men and women in the Christian household, Josephine and her husband George lived an intentionally mutual relationship.

In a letter to his wife, George Butler – an Anglican Priest – shared:

“I should think it undue presumption in me to suggest anything to you in regard to your life and duties. He who has hitherto guided your steps will continue to do so. Believe me, I value the expression of your confidence and affection above ‘pearls and precious stones’, but I must not suffer myself to be dazzled, or to fancy that I have within me the power of judging and acting aright which would alone authorize me to point out to you any path in which you ought to walk. I am more content to leave you to walk by yourself in the path you shall choose; but I know that I do not leave you alone and unsupported, for His arm will guide, strengthen and protect you.”

That is to say, that this Victorian marriage was remarkably founded on an assumption of and the practice of true equality.

In her writings, Butler draws clear connections between the lust and greed of the slave-dependent British Empire and the way in which its barons of power treat women. Speaking of the wrongs inflicted on black women as a part of the slave trade, Butler says of women:

“I think their lot was particularly horrible, for they were almost invariably forced to minister to the worst passions of their masters, or be persecuted and die…how keenly they awakened my feelings concerning injustice to women through this conspiracy of greed and gold and lust of the flesh, a conspiracy which has its counterpart in the white slave owning of Europe.”

Greed. Money. Power.

Insatiable appetites

and the worst passions of their masters.

Powers of individuals

Shaped and reinforced

by the insatiable lusts of empire

Desires to rape, subjugate, and control

All that is not powerful

All that is not of the empire

All that does not fit into

What is good and right, and wealthy, and male.

It sounds familiar.

Sounds familiar to ears new and old.

To meek and bold

Seeking to live lives of faith

In the midst of what some might call this confusing

communion of corporate sponsors and advocates,

these principalities that dominate our airwaves,

that pump their audacious power through palaces and marble halls

on movie screens and in shopping malls

and even though in our heart of hearts, we all know

that every single empire falls,

we can’t help but wondering

How did we end up here?

It sounds all too familiar, and in response, Josephine Butler declares

“Ours is a battle in which ‘we declare on whose side we fight; we make no compromise; and we are ready to meet all the powers of earth and hell combined.”

Principalities that seem too great to bear,

Powers that seem too strong to resist

And yet in the midst of it, we hear this freedom song crackling in the background:

For in him [in Jesus] all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, by making peace through the blood of his cross.

And so the question becomes: whose side are we on? The question is not simply “who is Lord of your life,” although that’s a part of it.

The question raised by St. Paul in this Colossian hymn, and by Josephine Butler’s life is rather, who is the Lord over all of life?

Reconciled in Christ.

All Things Reconciled.

The powers have been defeated,

And in Christ reconciled.

And though we wage battle.

And though there is injustice left to fight

The powers have been defeated

And been reconciled to God in Christ.

There are struggles that continue for us today. A few weeks ago, some of these struggles for justice were named in our very own community:

Our posture with indigenous peoples

In light of all that has happened

All we’ve been a part of

From Residential Schools and Systemic Racism

To our ignorance and indifference

Which is just as bad

Our posture towards LGBT communities

In light of all that has happened

All we’ve been a part of

From division and hurt

To outright exclusion

Delivered at the hands of the church

And as we approach the table.

As we approach our Lord’s table,

to partake in the food of redemption, and

the drink of reconciliation,

As we, the Church, the Body of Christ, offer ourselves

As living sacrifices

Broken

Poured out

We do not offer to God

Offerings that cost us nothing

Because we are reminded that

all has been reconciled.

To God in Christ

and that all will be reconciled

to God through Christ’s body, the Church

Broken

Poured out

For the life of the world.

And that somehow, through the power of the cross,

Jesus has reconciled all things

Not just the good guys

Not just the people with whom we agree

But that Jesus has reconciled all things

And that our kingdoms,

Our quests after power and control

Our miserable attempts at fidelity

All end in the same place, recognizing that

All have sinned

All have fallen short

And all will somehow,

Through the power of Christ

Be redeemed because

We who were once estranged and hostile in mind, doing evil deeds, have been reconciled in Christ’s fleshly body through death

Josephine Butler fought her entire life for the dignity of those pushed to the margins by both society and the church. She was strong, yes. And at times was weak. She succeeded, and encountered failure. But in it all, she was not so much motivated by Ideas About God, but by staring fully into the face of Christ Crucified.

As we conclude, listen to some of Josephine Butler’s personal reflections on faith:

“I never yet knew a heart which was constituted to feel a deep human love for a doctrine. Every heart must learn to love a Person….For my part I cannot truthfully echo the complaints of those say they do not love, for I do love. I have many complaints against myself, but not this one—I love my Lord and not chiefly because He has saved me. I love Him for that, but I love Him most because He loves me, and because He is so loving, so glorious, so awful in beauty.”

Bright, blinding lights ahead.

We stare. Transfixed.

Starting to move, starting to see, starting to comprehend

All that is before us

All there is to take in

All that could be.

All this might mean.

No longer captive to the powers of this world

We are united in Christ

We are united through Christ

We are united because of Christ

And off in the distance,

Winding its way

through Colossian streets,

along 1st Ave

and to the ends of the earth

We hear this Freedom Song:

For he is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and for him.

Amen. And Amen.

Filed under: Andrew Stephens-Rennie, Colossians Tagged: Christian Feminism, Colossians, Earl Grey, Empire, Greed, Josephine Butler, power

Brian J. Walsh's Blog

- Brian J. Walsh's profile

- 14 followers