Curtis Edmonds's Blog, page 11

February 5, 2019

Four Short Stories Whose Heroes Are Extremely Passive-Aggressive, Which You Totally Don’t Have To Read If You Don’t Want To, It Won’t Hurt My Feelings

THE TIMELY TIP

It was close to the end of Karen’s shift at The Monmouth Inn. She was clearing away her last table, and picked up the credit card slip. The signature was neatly written in perfect handwriting, “Mrs. Regina Blankenship.” But the tip was only two cents.

“This is so disappointing,” Karen said.

Her fellow waitress, Rebecca, came over to examine the tip. “Oh, yeah, old Mrs. Blankenship. You must not have gotten her a refill on her coffee. She’s done that to me before.”

“I thought I was doing such a good job,” Karen said.

“You did just fine, sweetie,” Rebecca said. “It’s just her way of letting you know you could have done better. She means well, you know.”

Karen went home at the end of her shift and thought about the two-cent tip. She went back into work the next day, determined to be a better waitress. She was more solicitous to her patrons. She made every effort to notice when they were trying to be helpful by stacking their plates. She worked harder to anticipate their needs and to make sure that they always got their coffee refilled.

The next week, Mrs. Blankenship was sitting again at one of Karen’s tables. Karen made sure not to notice when Mrs. Blankenship gave her a frosty stare at the beginning. She convinced the kitchen to make Mrs. Blankenship a club sandwich with the crusts cut off, even though it was kind of a pain for them. And she made sure Mrs. Blankenship got a second cup of coffee.

Karen was so thrilled when Mrs. Blankenship gave her a ten-percent tip this time. “I wish it were fifteen percent, but I guess she’s trying to tell me I have a long way to go before being the kind of waitress I know I can be,” she said.

THE BIRTHDAY DINNER

“Have you decided where you wanted to go for dinner for your birthday, Mother Reese?” Josh said.

Amanda Reese straightened her back in her armchair. Josh had been her son-in-law for five years now, and he still didn’t know how to handle the simplest of social situations.

“Wherever you and Melinda would like to take me would be fine,” she said.

“I thought you might say that,” Josh said.

Amanda tilted her head a fraction of a degree. She had never thought that Josh was fully as dim-witted as he appeared to be. Could it be that he was finally learning?

“So I thought about it, and did some research, and came up with three options.” Josh looked pleased with himself, although Amanda couldn’t imagine why. “First, there’s the new Thai place that opened on 206 last month. It got a very good review in the Princeton Packet.”

“I see,” Amanda said. She had never had Thai food in her life, and she wasn’t about to start.

“The second option,” Josh continued, “was the White Horse Tavern. It’s a little bit of a drive, but it’s through pretty countryside, and Melinda thought you might want to look into one of the antique shops on the same block.”

Amanda made a slight motion with her fingertips, as to encourage Josh to go on. She didn’t know if Josh could actually afford the White Horse Tavern on his salary, but she wasn’t going to turn down a nice meal there.

“Finally,” he said, “there’s the American Harbor Grill out on Route One. It is a little closer, and I know you’ve been there a few times.”

Amanda stiffened with horror. Surely Josh wouldn’t take her to the American Harbor Grill for her birthday.

“So where would you like to go, Mother Reese?”

“They all sound lovely,” Amanda said. “Why don’t you young people choose?”

“Josh,” Melinda said, “I’m not sure I’m really up for Thai food. And do you remember that Bill and Priscilla went to the American Harbor Grill with Mother last month, and the service was so bad?”

“Oh,” Josh said. “Well, I guess we ought to try the White Horse Tavern, then.”

“That would be fine,” Amanda said. She was pleased to know that Melinda, at least, knew how the game was supposed to be played.

THE TEAM PLAYER

Mark was sitting in his office when Gina came in, as he knew that she would.

“Excuse me, Mr. Parker?” she said. “Do you have a moment?”

“My door is always open for you, Gina,” he said.

“I got your memo about the team meeting on Friday,” she said.

“Oh, good,” Mark said. “I look forward to having your input on the project.”

“Well, Mr. Parker, it’s just that Monday is a holiday.”

“Thank you for letting me know, Gina,” Mark said. “It’s always nice to be reminded about dates on the calendar.” Mark hoped that Gina caught the faint tinge of sarcasm, but unfortunately for her, she usually didn’t.

“It’s just that my husband and I were planning a long weekend in the Poconos,” Gina said. “I had put in for a vacation day on Friday two weeks ago.”

“I understand that,” Mark said. “But the memo—you said you got it, right?—made it very clear that this was a mandatory team meeting.”

“We’ve really been looking forward to this chance to get out of the city,” Gina said. “Is there any way we can move up the meeting to Thursday afternoon?”

“I’m afraid not,” Mark said.

“What should I do?” Gina said.

“I think that you should decide on what’s best for you,” Mark said. “Take some time and think about what your priorities are. If you decide that your marriage is more important than your team, then by all means go to the Poconos.”

Gina’s face brightened. “I knew you’d understand, Mr. Parker. Thanks. I’m sorry to miss the team meeting, but it’s so important for us to get away right now. I’ll see you on Monday.”

Mark smiled to himself. He knew that he would be able to mark Gina down on her performance report as a result of her missing a mandatory team meeting. He was one step closer to being to tell HR that she had to be fired. It was for her own good, he thought. She wasn’t a team player.

THE THANKSGIVING MIRACLE

Audrey Prescott put the remnants of the Thanksgiving turkey in the refrigerator. Most people would have just thrown the bones away, but Audrey knew that they would make an excellent stock—much better than ordinary chicken soup. It was too bad, she thought, that younger people didn’t always take the time to think ahead. Like her daughter-in-law, Cindy.

Cindy had called her the week before Thanksgiving to ask if she could bring anything. Audrey had her Thanksgiving menu planned already, and didn’t need another dish. But it would be rude just to tell Cindy not to bring anything.

“I don’t think you should feel compelled to bring anything,” she had told Cindy. “Maybe something simple, like a nice bottle of wine.” Audrey didn’t think that Cindy knew enough about wine to pick out a nice bottle, mind you, but even if she brought a third-rate red, Audrey could use the wine to make coq au vin or something.

“Oh, no, Mother Prescott,” Cindy had said. “I really want to contribute this year.”

“Please don’t feel that you have to go to any trouble,” Audrey had told her. “Perhaps something simple, like a pie.” Surely Cindy could go to the Shop-Rite and pick out a pie.

“I know just the thing,” Cindy had said.

As it turned out, “just the thing” had turned out to be a rather large pot of corn casserole. Unfortunately, what with the turkey and the cornbread dressing, Audrey didn’t have room in her oven to re-heat the casserole. She had generously offered Cindy some microwave time, but the microwave didn’t heat up the casserole all the way, and it turned out a little runny.

And now Audrey faced the task of scooping out the casserole, and putting it in a Tupperware for Cindy to take home. She went to the cupboard for a clean ladle and had just started the chore when Cindy came over to her.

“Let me help you with that,” Cindy said.

“It’s no bother, my dear,” Audrey said. “You just run along and do whatever it was you were doing. I’ll take care of the cleaning up.”

“I just wanted to say that I was sorry,” Cindy said. “I should have realized that there was a reason you didn’t want me to bring anything. I thought it was because you didn’t think I could cook.”

“Why would I think that?” Audrey said. In fact, she didn’t think that Cindy could cook, but that, again, would have been rude.

“I realize now it was because you had your menu planned, and the casserole was just one extra dish that you didn’t have time for. I’m so sorry, Mother Prescott. I’ll try to do better next year.”

“You don’t have to apologize,” Audrey said. “You’re a dear for wanting to help. I appreciate that.”

“I was just thinking,” Cindy said, “we can have Christmas dinner at our house next month. It would take some of the pressure off you.”

“That would be lovely,” Audrey said. “Assuming that we don’t get snowy weather. It’s a little far for me to drive when the streets are slick.”

“Well, then, we’ll just plan to do Christmas here, then,” Cindy said. “If you’ll excuse me, I think Andrew is looking for me.”

Audrey smiled. She made a note to herself to give Andrew a list of wines that would go well with Christmas dinner, and then have him make sure that he and Cindy brought a bottle over instead of that ghastly attempt at a casserole. The holidays were always such a special time.

This International House Of Pancakes Is A Sanctuary For All

In this time of political turmoil, it is important that each of us have a safe space–a space where we can come together to discuss the important issues of the day, and partake of the bounty of delicious Rooty Tooty Fresh ‘N Fruity®Pancakes. The International House of Pancakes has always celebrated the importance of caring and diversity, and we want to re-affirm our commitment to providing a welcoming environment, free from the constraints of the capitalist patriarchy. So, welcome. Welcome, one and all, to this sanctuary IHOP.

Welcome, refugees from war-torn Muslim countries. Sit back, and partake of our delicious coffee, made from 100% arabica beans. Take some respite from your cares and troubles. Can we tempt you with our crispy chicken Cobb salad? I’m almost certain that the chicken is halal.

Welcome, feminist revolutionaries. You and your pink hats are a vital part of our caring, nurturing IHOP community. Our Harvest Grain ’N Nut® Pancakes can help you get the energy you need to throw off the shackles that have enslaved women for far too long. Toby will be your server today–did you know he has a graduate degree from Oberlin in womens’ studies? I think he’s contributing his tips to Planned Parenthood this month.

Welcome, illegal Central American immigrants. Curl your battered, work-hardened hands around a cold iced tea. Our chicken fajita omelette will give you the protein you need for another day on the construction site. There are no walls keeping you out from this IHOP.

Welcome, our transgender brothers and/or sisters. Just as you have chosen to embrace gender fluidity, we have chosen to diversify our menu of crepes. If you want a banana crepe and a raspberry crepe together on the same plate, you need only to ask. And of course you can use whichever bathroom you want. We don’t judge.

Welcome, radical college students. Nestle into our spacious booths. Relax and enjoy some calming herbal tea. You’ll never find microaggressions here at the IHOP. If you’d like a coloring page and some crayons, we can set you up. Anything you like. Unless you want something gluten-free, because we haven’t been able to convince corporate that we need to do that.

Welcome, antifa protesters. Go out into the streets with your signs and your songs of freedom with the full knowledge that this IHOP is behind you one hundred percent. The appetizer sampler is on the house.

Welcome, long-haul trucker with the “Make America Great Again” hat. We understand how your loneliness and angst led you to believe the lies that you’ve been told about our country. Rest assured that the IHOP won’t turn its back on the hard-working backbone of our country, unlike some people we can name. We’ll have your eggs and hash browns out in just a minute, just as soon as Toby comes back from his break. I think he’s finishing this article he was reading on the Mother Jones website.

Welcome, welcome, one and all, to this warm, inclusive, nurturing International House of Pancakes, where we celebrate coexistence and diversity every day. Unless you’re one of those deplorable alt-right types, who can get right the hell out. Go to Waffle House; that’s where your kind belongs anyway.

Surprise! Your Feminist Aunt Is Here To Take You To See The Wonder Woman Movie!

Hey, there, Jayden.

Yeah! It’s me! Your Aunt Frieda! You remember Aunt Frieda, right?

Okay, it’s been a while. Last Christmas, remember? You went to Grandpop’s, and I got you that Sally Ride action figure? And then I got into a big fight with your mom because she voted for that idiot Trump? You remember that, right? Crazy Aunt Frieda!

You remember me, I know you do.

Anyway. Get your shoes on, please. We are going to the movies! Yeah! It’ll be fun!

Sure, we can go. I talked to your dad, and he said, “Yo, whatever,” and since your mom is away at that conference, we thought now would be a good time for a little aunt-nephew bonding. I even got some organic pretzels that we can sneak into the theater for a little snack. That’ll be fun, right?

What movie? I am so glad you asked. We are going to see the Wonder Woman movie! Yeah! Won’t that be fun! We are totally going to see an empowered female superhero kick some patriarchal ass. I mean butt. Patriarchal butt. Yeah!

Of course you want to see Wonder Woman. Did you know that she’s friends with Batman AND Superman! Seriously! It’s going to be awesome, and we can leave as soon as you get your shoes on.

I’m sorry? You want to see what? Captain Underpants? Not sure who that is, exactly, Jayden, but it sounds like maybe he’s part of the military, and you know the military is one of the tools of the patriarchy, right? So we don’t want to celebrate military successes. No, we do not. But Wonder Woman is a symbol of feminist uprising against the patriarchy, and that is so cool. Am I right? Of course I’m right. I’m your crazy Aunt Frieda, so I can’t be wrong.

Good job with that one shoe. Can we work on the other one?

Does Wonder Woman have any cool powers? Well, she has an invisible airplane. That’s kind of cool. And this magic rope that makes you tell the truth. Maybe she’ll lasso our so-called President and make him tell the truth about how he helped the Russians steal our democracy. That would be so awesome, right?

Great! Both shoes on. If you can go potty real quick, we can go to the theater. I am so psyched for this. Wonder Woman!

Did you wash your hands? Good job. All good feminist allies should always do a good job washing their hands.

Your dad is in the garage; he’s putting your car seat in my Volvo. I have a Howard Zinn lecture in the tape deck, so we have something to listen to on the way to the theater. Fun, right?

Okay, let’s go. Say goodbye to your dad, okay? Yeah! We are going to have so much fun, Jayden, and we are going to learn so much about female empowerment today! I can’t wait.

And you don’t need to tell your mom we went to the movies, right? Because, I mean, your mom is awesome, but she’s maybe still a little mad at your crazy Aunt Frieda for calling her a misogynist. But you know, that’s what I do. Speak truth to power. I bet Wonder Woman does that, too, when she’s not punching white supremacy in the face.

Yeah! Okay, let’s go! Wonder Woman! Yay!

Mission Statement and Strategic Vision, Happy Fun Co. (Internal)

Our company exists to take money from small, gullible children and their irritable, easily wheedled parents, while giving nothing in return but a minuscule chance at receiving a stuffed animal.

Who We Are

We are your neighbors. We are your friends. And we are the people who construct those claw machine games you see on the Boardwalk, you know, the ones where you put in a dollar and maneuver the little claw and drop it on top of a pile of stuffed animals, with the idea that the claw will pick up a stuffed animal and drop it in the little chute, only the claw isn’t actually capable of picking anything up, and you just lost your dollar. And we’re also the people who pack the stuffed animals down in the machine so there’s really no way you could get one out anyway, even if the claw worked, which it totally doesn’t.

Our Strategy

It’s really simple. We construct these machines with lots of flashing lights, and bright, cheerful signs, and make sure that we use the cheapest materials possible in building the claw part of it. Then we stuff the machines full of Beanie-Baby knockoffs that we order wholesale from Cambodia. Then we put the machines in places that parents might take their children to have a little fun, and where the parents might have their inhibitions lowered enough to say, “Okay, quit bugging me, here’s a stupid dollar, go play the claw machine if that makes you happy.” Then we take the dollar, and the kid doesn’t get their stuffed animal, and maybe they try again. And maybe some other kid sees it and wants to try it, and we make yet another dollar.

How We Do What We Do

Well, Jeff and Clay over there make up the machines–Jeff cuts the glass, and Clay does the sheet metal work. Paul does all the electrical work, and Mark installs the little machine that has the slot where you put in the dollar. And then Chet play-tests it to make sure you can’t get the stuffed animal out of the machine, no matter how hard you try. I order all the stuffed animals–well, mostly it’s stuffed animals, sometimes we put other stuff in there, depending on the client. I handle the sales, and everybody helps load up the machines on the truck so that Clint can drive it to wherever it is that’s ordered one. Pretty standard stuff.

How We Sleep At Night

Pretty good, although I get back spasms every once in awhile, especially when Mark takes a day off and I have to help load machines on the truck. Clay has sleep apnea and has to use one of those machines, but other than that he’s fine. Chet stays up late on Monday nights during football season, and sometimes when the Mets are out on the West Coast, but he always makes it in to work on time.

No, How Do You Sleep At Night Knowing That You Take Allowance Money From Innocent Children

Well, that’s our market. I mean, you know, really, when you think about it, we’re doing them a service. We’re providing entertainment, the same kind of entertainment you get when you put a quarter in the slot machine, or buy a lottery ticket. And we have better odds than the lottery. I mean, maybe not much better, but you get the idea. And what else are they going to do with it? Spend it on candy? Yeah, right, like that’s a good idea. It’s a little bit of harmless fun, and the kids learn something. Or at least they learn to be less gullible, and that’s a good thing. I mean, you ought to read the crap that people post on Facebook.

February 3, 2019

The Incredibly Awesome Story of the World’s Greatest Fantasy Football Trophy That I Made Myself

I won my fantasy football league some years back.

You don’t care. I know that you don’t care. I know that you especially super-double don’t care if you lost your fantasy football league last year, as most of you did. But I won my league that year.

My team, “Ghost of Don Meredith,” went 10–4 in the regular season, and won the first-round playoff game by thirty points, thanks to strong showings by Seattle Seahawks running back Marshawn Lynch and New Orleans Saints wide receiver Marques Colston on my team, and a total, epic meltdown by Cleveland Browns quarterback Johnny Manziel on the other side. The championship game wasn’t even close, as running back Lamar Miller of the Miami Dolphins and tight end Antonio Gates of the San Diego Chargers led the Ghosts to a resounding triumph over my wife’s nephew’s team.

I cannot tell you how many fantasy football leagues I have been in over the years, mostly because I don’t care, but this was the first fantasy football league I had ever won. (Technically, my wife and I won — everyone else in the league is in her family — but she defers to me on most of the moves.) I guess that explains what happened next. Something had to.

Not shown: Pass being intercepted by opposing cornerback late in game.

Not shown: Pass being intercepted by opposing cornerback late in game.I don’t remember where I saw the story about the OYO minifigs. You can buy tiny little OYO (note, NOT Lego) replicas of pretty much any NFL, MLB, or NHL star that you desire. I will stress again that these are not official Lego products, but they are compatible with other Lego stuff, at least as far as I can tell. I remember reading the story, thinking, “Huh,” and then not thinking about it any more after that.

But the Monday after the Ghosts of Don Meredith clinched their victory, there I was on Amazon, buying an OYO minifig for each of the players on my fantasy team. I did a little bit of Google searching and found someone on Etsy who made Lego minifig stands that made it look as though the minifigs were standing on risers, like you’d see in a football team picture.

Perfect for your next minifig Village People reunion.

Perfect for your next minifig Village People reunion.From that point on, it was all simple. All I had to do was wait for Amazon to send me the various OYO figures that I needed. My fantasy league has deep rosters, so I went ahead and got fifteen different figures. Etsy came through again with a minifig that was supposed to represent Will Ferrell in “Anchorman,” and sported a perfect gold blazer to represent unofficial team captain Don Meredith, as he appeared during his Monday Night Football career.

Top Row: Lamar Miller, Miami Dolphins, Anquan Boldin, San Francisco 49ers, Antonio Gates, San Diego Chargers, Dez Bryant, Dallas Cowboys

Second Row: Alshon Jeffrey, Chicago Bears, Mark Ingram, New Orleans Saints, Marshawn Lynch, Seattle Seahawks, Richard Sherman, Seattle Seahawks (defense)

Third Row: Andrew Luck, Indianapolis Colts, Marques Colston, New Orleans Saints, Andy Dalton, Cincinnati Bengals, Hakeem Nicks, Indianapolis Colts

Bottom Row, Don Meredith, Team Namesake, Steven Hauschka, Seattle Seahawks, Ben Roethlisberger, Pittsburgh Steelers, DeSean Jackson, Washington Redskins

The use of the OYO figurines lends itself to a little pose-ability. You will note that the kicker’s leg is up, and that Dez Bryant is “throwing up the X,” as he does after touchdowns.

Everything didn’t go well when I put the figurines together. The facemasks on the minifigs aren’t attached to the helmets and have an awkward tendency to go flying in the air. Sometimes players would pop off their stands and knock two other players off. But overall, I was pleased with the results.

I say all of this to say three things. First, I do not have very much time on my hands, thank you very much, just enough to do this. Second, I don’t care what you think; I think this is the most incredibly awesome fantasy football trophy ever and I shall cherish it always.

Third, I have to tell the story of Don Meredith’s head. I decided to swap it out. The head that the minifig came with had muttonchop sideburns and didn’t look like Meredith. It turns out you can’t buy just a minifig head at the Lego Store; you have to buy three figurines. (The trophy that Meredith is holding is from the Lego Store, by the way.)

So I was at the local Lego Store, a grown man on his lunch break, trying to find just the right head for my awesome fantasy football trophy, and one of the cashiers came up to ask if she could help. “Thanks,” I said. “I got it.”

She said, “What are you working on?”

I said, “I can’t say. It’s too crazy.”

She shook her head. “No, baby. Whatever it is, I guarantee you, I’ve heard crazier.”

So there you go. I have a few more up-close pictures if you want to see them, below. Thanks for reading.

LOCK IN, by John Scalzi — the “Horrifying Scenario” Analysis

This is not a book review. I wanted to do a book review for Lock In, by John Scalzi, which is a book that I both think very highly of, on one hand, and which I also think has a couple of serious flaws. The problem is that I try to write book reviews without giving away plot spoilers, and I can’t talk about the single biggest flaw in Lock In without giving away the big spoiler in the book. So this isn’t a book review; it can’t be.

What I decided to write instead of a book review is to talk about the world of Lock In and the (largely unstated) horrifying consequences that would ensue from such a world. This approach assumes that you’ve either read Lock In or are at least willing to listen to a brief synopsis of the plot. WARNING: This discussion contains major spoilers for Lock In. Please do NOT read this if you have any intention of reading the book at a future point.

Horrifying Scenario #1: The Experience Machine

In Lock In, a significant minority of Americans–Scalzi likens it to the population of Kentucky–experience “lock in” as a result of a mutated flu virus that attacks people’s brains. Individuals affected with the “Haden” virus cannot move or blink or even scratch where it itches, which does not sound good. The scope of the Haden infection is so vast that the government spends a trillion dollars on research-and-development to consider what can be done to mitigate the suffering of the locked-in.

What the research comes up with is a four-fold system. First, a surgeon cracks open your head and installs a new neural network (complete with tentacles) that interfaces with your brain. (Scalzi tells us that this can be installed in the brains of the very young, although you’d think that would mess with normal brain development.) The network then transmits your consciousness to your choice of outlets. You can access “The Agora,” which is described as a “three-dimensional social network,” which doesn’t mean anything except pointing out how two-dimensional current social networks are. You can transfer your consciousness to a big clanky robot, colloquially known as a “threep.” Or, you can interface with an “Integrator,” someone who was infected with the Haden virus but not locked-in, who has a similar neural network and is not doing anything on Saturday and is happy to let you use their bodies for a couple of hours for cash.

Each of these aspects of the system has its own horrifying scenarios, but the most philosophical of them deal with the concept of “The Agora.” Scalzi does almost nothing to explain “The Agora,” classifying it all as it’s-a-Haden-thing-you-wouldn’t-understand. Very well then. This leaves the reader free to imagine what it’s like, and what it’s like is probably something close to the Experience Machine. Wikipedia:

[Harvard professor Robert] Nozick asks us to imagine a machine that could give us whatever desirable or pleasurable experiences we could want. Psychologists have figured out a way to stimulate a person’s brain to induce pleasurable experiences that the subject could not distinguish from those he would have apart from the machine. He then asks, if given the choice, would we prefer the machine to real life?

The classic response to this is “no,” or at least “not permanently.” But this is from people who are capable of both being able to respond and to scratch that place behind their knee. Would somebody who was totally locked in want to spend at least some part of their day in an Experience Machine? The answer, unsurprisingly, is HELL and YES.

That positive response is reinforced by two other factors. First, “The Agora” is superior to the Experience Machine in that the Experience Machine is a solo endeavor and “The Agora” seems to be more social, so there’s that. Second, at the end of the book, the protagonist announces a plan to set up a competing version of “The Agora” free from government control, which could make it even more awesome (i.e., free of censorship).

So why is this horrifying?

Scalzi makes the point that the Haden economy is dependent on dwindling government largess, and has to be offset by tax dollars brought in by Haden workers. Fair enough. Medical care for Hadens has to be a really big number (as we’ll see) and it’s got to be offset somehow. If said Haden who is receiving said medical care is on “The Agora” playing an immersive version of Madden 2025 for twenty-four hours a day, that sort of eats into one’s productivity. (Ask me how I know.)

So here’s the question: Given the choice, as a Haden, would you plug into “The Agora” 24/7, or get a job (that is to say, the kind of job you can get as a robot)? In Lock In, the answer seems to be largely up in the air. The protagonist (more on him/her later) lands a job as an FBI agent, and there’s a general strike of all Haden workers that serves as a backdrop. (We’re not told much about what sort of jobs Hadens get in the economy–a lot of them seem to be truck drivers, although we see a doctor and a software developer.) The general strike is a response to the funding cuts for Haden patients, and is part of a political movement for Haden independence (which seems at cross-purposes with the need for more funding but there you go and political movements in fiction don’t have to make perfect sense any more than they do in real life).

If “The Agora” is largely how Scalzi represents it, it may not be much of a question. But if “The Agora” is anything like, say, the OASIS in Ready Player One, where you can hop in your DeLorean and spend the day shooting wamp rats with your proton pack and your nights drinking pina coladas, eating lobster and making love like sea otters, that might be a different story altogether.

Look, you don’t even have to have a Ready Player One virtual reality universe for this to be a problem. Japan already has an issue with its hikikomoripopulation of young people who don’t work, live off government assistance, and fool around with anime and manga comics all the livelong day–and who don’t have sex or reproduce, cutting into Japan’s fragile birthrate. Could the American economy support caring for multiple millions of helpless people who are spending their time eating virtual bonbons on Planet Hershey?

And that’s just the Haden population. What about everyone else? Scalzi tells us that the non-Hadens can access “The Agora,” but only in restricted settings. If anyone can tune in, turn on, drop out, and spend their days doing (oh, let’s say) Starsky and Hutch virtual cosplay? What does that do to the economy?

Starsky and Hutch cosplay would be a lot of fun. I am just sayin’.

Starsky and Hutch cosplay would be a lot of fun. I am just sayin’.In Ready Player One, the protagonist is driven past a small camp of homeless people standing around a trash fire, waving around their haptic gloves and staring into their visors, oblivious to the ruined society all around them. In the Lock In world, you wouldn’t even need the visors and gloves — the entire virtual world is hard-wired directly to your brain.

Obviously everyone wouldn’t plug in–but you’d have to think that enough people would, enough to depress the economy and wreck the birthrate.

Horrifying Scenario #2: The Medical Model

A brief aside here.

I am not really qualified to talk about the disability issues in Lock In because I don’t have a disability. Having said that, I’ve got over twenty years of experience as a disability advocate. I run the state assistive technology program in New Jersey. I’ve written four law review articles on the ADA and the Air Carrier Access Act, and two or three scholarly articles on website accessibility. So maybe I’m a little qualified to talk about it a little bit.

Lock In has a scene where its protagonist, Chris Shane, Special Agent of the FBI, transmits his/her consciousness to the Los Angeles FBI office, where he/she is given a defective threep, which he/she is expected to operate by means of a manual wheelchair. It’s not clear as to whether this is meant as a practical joke of some kind or just an outside-the-box way to re-purpose broken equipment. Chris doesn’t comment on this other than dropping the mic and renting a threep from Avis, but the implication is that Chris is rejecting the disability label.

Which is fine. Generally speaking, society doesn’t have an issue when people with disabilities want to be treated like they’re not disabled. You hear that people have “overcome” their disability, or you hear parents bragging that they treated their child with a disability just like any other kid. We’re fine with that sort of thing as a society. Able-bodied people want to think that having a disability is not a big deal, and can be overcome with character and work ethic. (It doesn’t work in reverse: society hates it when able-bodied people park in accessible parking spaces.)

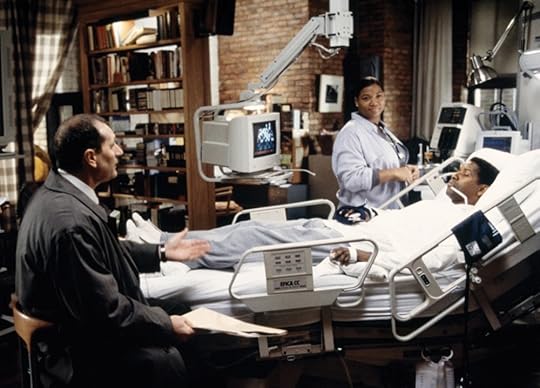

The problem is that, to pull something like this off, it is really helpful to have lots of resources available to you. You might have seen a movie a few years back, The Bone Collector, where a bed-ridden Denzel Washington fights crime–with the aid of about sixty different computer screens and enough processing power to run Cheyenne Mountain. That’s how disability works in Hollywood. And as someone who has spent a great deal of his work life trying to get Medicaid to pay for even simple durable medical equipment, I can tell you, Hollywood ain’t real.

I mean, seriously, look at all this stuff. I have to fight like hell to get Medicaid to pay for any of this crap for my clients, much less all of it.

I mean, seriously, look at all this stuff. I have to fight like hell to get Medicaid to pay for any of this crap for my clients, much less all of it.What Scalzi does here is cheat by giving Chris a set of billionaire parents, who can afford to give him/her a dedicated medical cradle and twenty-four hour care and the latest hot-off-the-assembly-line threep. Which is fine; there are people in society who are rich and obviously their children are going to rate better medical care. Chris may not think of himself/herself as having a disability, but that hardly makes him/her what you would call typical.

So what kind of treatment does the typical Haden get?

You guessed it.

You guessed it.Scalzi hints at this when he talks about rental properties for Hadens, which are basically closets where their threeps can recharge. (I imagined these as being like Bender’s apartment in Futurama.) But those properties are for the threeps. Where are the bodies?

I don’t know for certain, but I bet they’re in nursing homes, or something worse than nursing homes. I mean, think about it from the perspective of a Medicaid administrator. (You may want to take a shower after you do this.) You have a greatly increased number of patients who need around-the-clock care and monitoring. What’s the cheapest way to do that? Answer: fill up old and disused facilities with Haden patients. The patients are all locked in, so you don’t need to have programming for them, or feed them anything but sludge, or provide clothes or counseling or even sunlight. It would be like The Matrix, but instead of using the patients as batteries you’d use them to collect federal Medicaid dollars. Tell me your average state Medicaid administrator wouldn’t do this in a second. (I would say “in a heartbeat” but, well.)

Take the red pill, and your federal Medicaid waiver plan is approved. Take the blue pill, and you’ll see just how far the rabbit hole goes.

Take the red pill, and your federal Medicaid waiver plan is approved. Take the blue pill, and you’ll see just how far the rabbit hole goes.There are two competing orthodoxies in disability policy. One is the “civil rights model,” which says that people with disabilities are people and have the right to be free and independent and not to experience discrimination, and sometimes discrimination comes in the form of a stairway or a doorknob or a toilet paper dispenser that’s three inches too high. Then there’s the “medical model,” which says that you have a disability if you meet a certain medical criteria, and if you do, we’re going to do our best to cure you, and if we can’t, well, that’s too bad, here’s some federal benefits and maybe a job at a sheltered workshop or something. What you have in Locked In, largely, is a situation where the civil rights model is ascendant, but only for people who have both a threep and the resources to arrange home care. It doesn’t say what happens to everyone else under the medical model. I don’t think that was good to start off with, and with the severe budget cuts Scalzi describes, it might get worse.

(Oh, and if you don’t think that the mass institutionalization of a large disability subset is ipso facto horrifying, you have my permission to visit a large state psychiatric hospital sometime. Please. I’ll hold the door open for you and everything.)

Oh, come on. Don’t be a fraidy-cat.

Oh, come on. Don’t be a fraidy-cat.Does Scalzi do a fine job of having a heroic protagonist with a serious disability? Yes, unreservedly. But the only major Haden characters in the book are Chris, a diabolical billionaire and his lackey attorney, a software engineer, a doctor, and a political leader. Maybe that’s not the top 1% of Hadens, but it’s telling that there’s not a representative character who’s in the 99%. I think Lock In handles the disability issues in the book with sensitivity, but it’s clearly not telling the whole story.

Horrifying Scenario #3: The Sexual Aspect

Scalzi goes to great lengths to keep the question of whether Chris Shane is male or female open, going so far as to say that “I personally don’t know Chris’s gender.” I am not going to speculate here on why he made that particular choice. I think it’s simultaneously kind of brilliant and kind of screwy, which is mostly meant as a compliment. I am OK with it in that I think that it’s an idea that progresses naturally from the premises of the novel, as Chris presents to the world as a non-gendered threep. I have very mixed feelings from the disability perspective, as there’s already a social stigma about talking about disability and sexuality together. I dislike that you have a heroic protagonist with a disability who is also genderless–I think that’s problematic.

What’s even more problematic is that Scalzi never, not even once, talks about Haden sexuality.

One of the characters in Lock In is a former Integrator, and according to her, what Haden patients typically do, when they are integrated with an Integrator for the first time, is go to Five Guys and get a bacon double cheeseburger.

Come to papa.

Come to papa.Now, look. I have nothing against the bacon double cheeseburger from Five Guys. I’d like one myself right about now. I’m from Texas, so I’d rather have a Whataburger, but to each his own. I just don’t think that would be everyone’s first choice. (Even from a gustatory perspective, I’d rather have Texas sheet cake and homemade vanilla ice cream.)

How many people, do you think, would hire an Integrator in order to have sex with their significant others? Or, you know, themselves?

I know what you’re thinking, because I am thinking it too, and I am thinking SQUICK SQUICK SQUICK SQUICK SQUICK. It’s okay. Take a deep breath.

Because I haven’t even gotten to the whole part about robot sex.

SQUICK SQUICK SQUICK SQUICK SQUICK.

SQUICK SQUICK SQUICK SQUICK SQUICK.OKAY. Calm down.

Look. There are a lot of different sexual scenarios that could, conceivably, come to mind in this particular universe. (And Scalzi discusses them at length in the sequel, Head On, which I didn’t like anywhere near as much.) I think that there is some wisdom, from an authorial perspective, to not exploring them, to leaving them unsaid. (I will point out that Scalzi has had no problem with exploring the group-sex implications of his fictional universe in the Old Man’s War books.) But by making Chris essentially genderless, Scalzi effectively walls off the reader from any discussion of Haden sexuality. (Or, to put it another way, he leaves it to the devices of the masses of fan-fiction writers. Squick.)

Horrifying Scenario #4: The Plague Years

Scalzi just happens to mention, at one point, that people are still getting lock-in, all the time, although not at the levels that were happening at the height of the epidemic. Meanwhile, you never see anyone, you know, wearing a surgical mask, or slathering themselves with Purell, or refusing to go outside, or generally behaving how people would behave if they thought they could catch the Haden flu and be locked in their bodies for the rest of their lives.

I am just throwing this out there.

I know why you have to have normal people running around doing normal things, because otherwise there wouldn’t be a story, but still. You’d think that people would be, you know, a little afraid of catching the flu in this universe. It’s already a paranoid thriller, you’d think that would amp it up a bit.

Horrifying Scenario #5: The Brain Hack

There’s a scene in Lock In where Chris sits in his/her Bat Cave (no, really), as he/she considers all the different suspects in his multiple murder case, and narrows them down to either an influential community organizer or a powerful billionaire titan of industry bent on cornering the market for Haden services.

Who do you think the killer is?

Go on, guess.

You’ll never guess.

Wow! You guessed right. It was the evil billionaire! How did you ever figure that out?

(Okay, I’m done now.)

(Okay, I’m done now.)This is the horrifying scenario that Lock In spends the most of its time exploring. Can evil billionaires hack your brain and turn you into a zombie assassin? The answer is yes. The problem is that (at the time of the novel) it’s incredibly expensive, and very much an emerging technology, and it’s just as easy to use an Integrator to shoot whoever you want shot. So there’s that.

What else can the technology do? Maybe you don’t want to turn your army of hacked Integrators and threeps into zombie assassins. Maybe you want them all to move to Delaware and vote for you for the open Senate seat. Maybe you want to hack their brains to play the Meow Mix jingle constantly in their brains until they commit suicide. Maybe you want to go seriously old-school Othello and convince someone that their wife is cheating on them until the point where he decides to murder her.

Anyway, point is, lots of things you can do if you can hack into someone’s brain. Including making them write very long blog posts that aren’t book reviews, instead of writing a new novel. Hey, wait.

The Less-Horrifying Conclusion

Lock In is a lot of fun to read and has at least one memorable character in Chris’s partner, who is Lynchian but the wrong kind (Jane and not David). It reads much better as a near-term science-fiction drama (a genre where it excels) than it does as a police procedural (where it largely falls flat). You should read it, and if you’ve read this far, you already have. It has cool zombie assassins and ninja robots. And it makes you think deeply about what the implications of new technology, both medical and robotical, might be for our own future, to the point of writing a long blog post about it that very few people will read. These are all good things, and it is to Scalzi’s credit that he produced a novel that generates such good things.

February 2, 2019

Why I Wrote a Picture Book About America in the Age of Trump

There is only one real reason anyone writes a book for children, and that is because they have children who pester them until they do. Or at least that’s what happened to me. I have eight-year-old twin daughters, and they are both avid readers. They know that I’ve written a couple of books for grown-ups, and they are not incredibly happy that they’re not allowed to read them. So they started lobbying me to write a book they could read.

This kind of thing does not always work, of course — I have successfully turned a deaf ear to multiple entreaties to get a dog, or a cat, or a hamster, or an iPhone. And, initially, I was able to deflect request to write a children’s book. “It’s actually harder to come up with a new idea for a children’s book than you think,” I would say. “You also have to illustrate it, and I have no idea how to draw.” I figured that would be enough to defuse the issue.

It might have been, too, except that I was driving the children home one day, and they were prattling to each other, pretending to be different people with different names. “Well, my name is Amanda,” one of them said to the other, and something about that struck home. (Amanda is their main babysitter.) Later that night, I wrote the first couplet for the book:

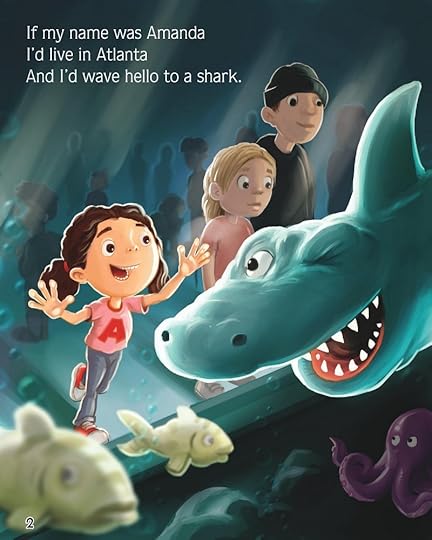

If my name was Amanda

I’d live in Atlanta

And I’d say hello to a shark.

If my name was Bonnie

Then I’d live in Boston

And catch fly balls in Fenway Park.

That was the easy part. (The “shark” reference is for the Georgia Aquarium.) Once I had the basic formula established, I had to figure out matching first names and cities for each letter in the alphabet, and then I went back and tried to get the rhymes to work. (I also ended up taking the Fenway Park reference out; I didn’t want to run into any trademark issues if I could avoid them.) After that, I had to get the meter just right, so it would be easy to read. That involved taking the entire text and putting it into a spreadsheet, with a separate syllable for every cell.

Once I got the text finished, and decided that the title should be , it was time to find help with the artwork. I lucked out and found an illustrator on Twitter — an English artist who turned out excellent work at a bargain price. Once I got the artwork put together, then it was time for the acid test — reading the book to the other kids at my daughters’ school. (They liked it, and their teacher was enthusiastic about the book’s use as a classroom aid to American geography.)

But why go through all the trouble to put out a children’s book in a market that’s already glutted with children’s books? There are already, literally, hundreds of rhyming alphabet picture books alone, many of them incredibly well-done and well-known. Why bother with another?

Ultimately, there were three reasons why I persevered and kept the project going.

1. I wanted to write a picture book that kids and parents could both enjoy.

This is sort of a cop-out — who wouldn’t want to write a children’s book that kids and parents can both enjoy? But there are a lot of picture books that don’t make for easy and convenient bedtime reading. Even the esteemed Dr. Seuss wrote Fox in Socks, which is just tongue-twister after tongue-twister; I finally put my foot down and refused to even touch it. I never did figure out why Goodnight Moon was so popular. The nearly-wordless Good Night, Gorilla is lovely, but requires the adult reader to fill in the blanks — and woe betide the tired parent who leaves out a key detail. I wanted my book to be short and concise, and I wanted it to have a simple rhyme pattern with a good rhythm for easy reading, and I think I accomplished that. (My model in this was Sandra Boynton; if you have a very small child in your house, you can’t go wrong with one of her board books for bedtime.)

But I also wanted it to be a book that wasn’t pushing any particular kind of behavior. A lot of children’s books focus on discouraging negative behaviors. We liked the Llama Llamabooks by the late Anna Dewdney, but they are almost all about how the young character has to learn not to throw tantrums every time something doesn’t go his way. (If that was, in fact, the intent of the books, they have been a spectacular failure at our house.) We also liked the Elephant and Piggie books by Mo Willems, but several of those are behavior-related, too — like I Really Like Slop, which is all about Piggie trying to push “pig culture” on Elephant Gerald (sound it out) by making him try a nasty-looking bucket of slop. I have nothing against any of these books, you understand, but I also didn’t want something with a heavy-handed behavioral message. Kids get that sort of thing all day long; can’t they get the occasional break from it?

2. I wanted to write a picture book that showed that America is more than a collection of strip malls.

I live in a small town in central New Jersey that has a lot of the same big-box retailers and fast-casual restaurant chains that you probably have in your town. I dislike the essential sameness of the suburban outback; when I travel with my kids, I want to try to get away from it as much as I can.

was designed to introduce some of the beauty and majesty of our country to children. It also showcases just how different the different parts of our country are. The young girl who is featured in the story visits beaches and ski slopes, monumental structures and pizza joints, wilderness hikes and urban adventures. In her imagination, she crisscrosses the country from the badlands of South Dakota to a balloon ride over New York. This is a big, interesting, diverse country, and I tried to capture some of that flavor in the book.

3. I wanted to show children a positive vision of America.

One of the most depressing statements of the last decade was Michelle Obama’s declaration that she had not been proud of America until the point that her husband began his Presidential campaign. (One wonders how she feels nowadays.) Akin to that in spirit, although not in content, is Donald Trump’s promise to “Make America Great Again,” which of course implies that America is not great now (and that only Donald Trump can make it great again). Both statements are not only profoundly negative, but depend on the premise that politics — and only politics — can make America more praiseworthy.

What a pathetic lie to tell to children! America is great in spite of her political leadership, not because of it. There is not a whiff of politics in , outside of a background picture of the Capitol dome. That’s because the things that make America great have little or nothing to do with politics.

There are a few political children’s books out there. One of the top-selling rhyming alphabet books on Amazon is a book called A is for Activist, which features a raised fist on the cover. One reviewer says “Reading it is almost like reading Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, but for two-year olds.” Charming. Chelsea Clinton published a book in May that riffed off of the rebuke Senator Elizabeth Warren received for criticizing the nomination of Attorney General Sessions; She Persisted: 13 American Women Who Changed the World features profiles of Oprah Winfrey and Sonia Sotomayor, among others. There are a few political children’s books on the Right as well — most notably by Rush Limbaugh.

I want my kids growing up with a sense of pride in our country and our people, unimpaired by political strife — to the extent that such a thing is possible anymore. I wanted to reflect that sense of pride, and to help strengthen it. It’s important for everyone, in spite of our political differences, to recognize that there is a great deal about our country that is worth celebrating, and if one little rhyming alphabet picture book can help do that, I feel like I’ve done a good job.

Curtis Edmonds is the author of IF MY NAME WAS AMANDA (if you haven’t figured that out by now) which is available on and .

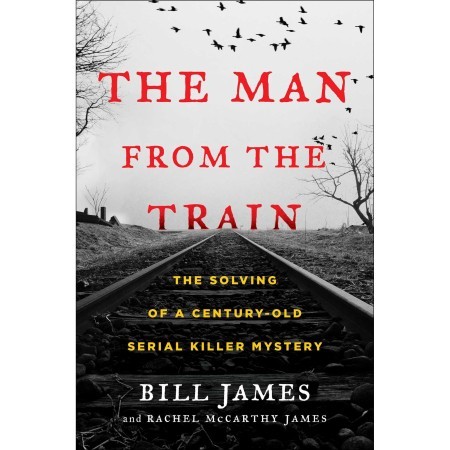

Bill James, Dave Kingman, and “The Man from the Train.”

This is a not-review of THE MAN FROM THE TRAIN, by Bill James and Rachel McCarthy James. (I do not for one minute want to discount the role of Rachel McCarthy James in writing this book, but the book is delivered in Bill James’s inimitable voice, and so I’m going to primarily focus on him, okay?) This is a not-review, because I’m focusing not so much on the book itself, which is (necessarily) repetitive, badly disorganized, and focuses on truly awful carnage. I want to focus on the big idea in the book, which is behavioral analysis. It’s a simple enough term; behavioral analysis focuses on what people do, and not the reasons behind what they do, or their justifications or excuses for why people do what they do.

All I am saying is that the font size for Bill’s name is a lot bigger for a reason.

All I am saying is that the font size for Bill’s name is a lot bigger for a reason.James uses the super-extreme example of a person he identifies as “The Man from the Train,” who James suspects of killing hundreds of people across America in the early years of the twentieth century by breaking into their houses and bashing their skulls in with the blunt end of an ax. Okay, so that’s a behavior. We’re doing behavioral analysis, so we’re looking at what this guy does, not what sick, perverted fantasies drive him to do this.

But you know, as much as you might enjoy reading about The Man from the Train, the whole thing gets so gruesome so quickly that talking about it is kind of tiresome, and if you’ve read the book, you’re likely sick of it, and if you haven’t, you’ve got a lot of stories about kids getting their faces smashed in ahead of you, so instead let’s talk about Dave Kingman.

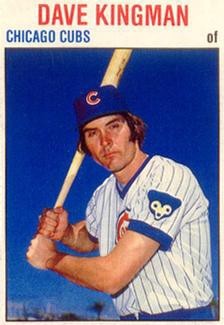

This guy. Not some other Dave Kingman, Just so we’re clear.

This guy. Not some other Dave Kingman, Just so we’re clear.Why Dave Kingman? Well, The Man from the Train was a strong guy who roamed around the country hitting people with an ax; Dave Kingman was a strong guy who traveled around the country destroying baseballs with baseball bats. It’s a thin connection, but I’m going with it. Anyway, it’s a lot more fun talking about Dave Kingman.

The important thing in behavioral analysis is understanding what a trait is and what a behavior is. Dave Kingman was a guy who played baseball a lot differently from most people, and he was a guy who had a lot of traits, and those traits get used to explain his behavior a lot. Example:

And in New York the much-publicized Dave Kingman character came out — here was the moody Kingman who swung hard at everything, who almost never walked, who pulled everything, who hit 500-foot home runs and 325-foot pop-ups, who ran the bases like a child coming in for dinner, who played defense not just poorly but with utter disdain. — Joe Posnanski, Sports Illustrated, 2008

So some of that is traits: “moody” is a trait, “disdain” is a trait. Wanting to hit every ball that you see 500 feet is a trait; it ties in with impatience and maybe being a little bit of a glory hound. But a lot of these are behaviors; swinging at everything is a behavior, no matter why Kingman did it, playing defense poorly is a behavior.

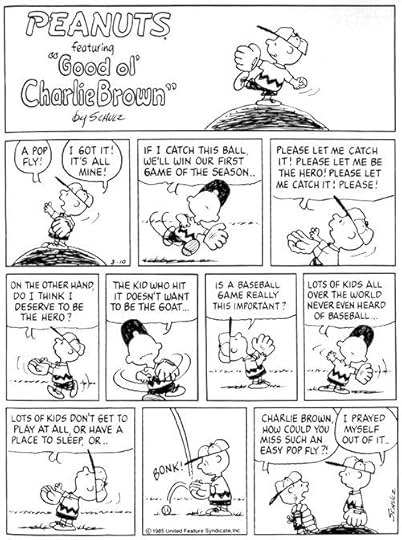

This is a good example of what I’m talking about. Charlie Brown misses the catch because of his traits, right? But all the official scorer cares about is his behavior — that he dropped the ball. (Baseball, you understand, is the sport that counts your errors, and punishes you for them in the box score.)

This is a good example of what I’m talking about. Charlie Brown misses the catch because of his traits, right? But all the official scorer cares about is his behavior — that he dropped the ball. (Baseball, you understand, is the sport that counts your errors, and punishes you for them in the box score.)One reason why baseball is such a great game is that it melds traits and behaviors. We are attracted to baseball partly because it’s a narrative sport that incorporates the traits of the players — the struggling pitcher who makes good on the game’s biggest stage, the slugger who comes through in the bottom of the ninth, the slick-fielding rookie who turns heads making an impossible double play. But it’s also the most behavioral and analytical of the sports, where everything anyone does is documented and available for analysis. It appeals to the half of our brain that loves stories and the half of our brain that loves numbers.

So when we go to the great and noble Baseball Referenceand look up Dave Kingman, you get

.236 BA, .302 OPB, .478 SLG, 442 HR, 1210 RBI, 1816 Ks.

Okay, you can look at those numbers (assuming you know what the numbers mean) and say, “Yeah, that looks like Dave Kingman.” A lot of power — 442 career home runs — but a lot more strikeouts, and a lousy batting average and on-base percentage. That tells you a lot about Kingman’s behaviors — he swung a lot, and missed a lot, but when he connected, the ball went over the fence.

James makes the point that we knew a lot about ballplayers like Kingman at the time, but we know even more about them now, because we have access to the sort of advanced statistical tools that James and others invented. We know more about Kingman than his contemporaries did — we know information about Kingman that he never knew about himself, information that’s only available through modern insights like Value Over Replacement Player statistics, or through the application of modern information technology analytical tools.

So the question in THE MAN FROM THE TRAIN is, well, we have technology and analytics at our disposal now. Can we go back and look at the data that they had then, re-evaluate it, and come up with a recognizable pattern? And once we have that pattern, can we reverse-engineer it to find our serial killer?

To give you an idea about what’s involved, let’s try a thought experiment. I am going to give you the statistics of three players from the 1979 Chicago Cubs; you tell me which of them is Dave Kingman:

Player A: .288 BA, 48 HR, 115 RBI, 131 K

Player B: .272 BA, 19 HR, 73 RBI, 85 K

Player C: .284 BA, 14 HR, 66 RBI, 28 K

Which one is it? It isn’t a trick question; Player A is Kingman. (Player B is Jerry Martin, Player C is Bill Buckner.)

Right? I mean, this is obviously Kingman, you can tell from the high levels of home runs and strikeouts. This was Kingman’s career year; his batting average was fifty points over his career average, and somehow he drew 45 walks, third on the team behind Ivan de Jesus and Steve Ontiveros . (This may be a function of intentional walks, though.) So far, so good, we can find a set of behaviors in a specific year that lines up well with Kingman’s known behaviors.

So what we’ve shown so far is that we can pick Kingman, basically, out of a lineup. Let’s try again. 1976 Mets:

Player A: .238 BA, 37 HR, 86 RBI, 135 K

Player B: .292 BA, 10 HR, 49 RBI, 38 K

Player C: .306 BA, 5 HR, 31 RBI, 35 K

Again, super-easy. Player A is Kingman, Player B is Ed Kranepool, Player C is Joe Torre. This is maybe a little easier because, well, there weren’t any other players with power on the 1976 Mets; Kingman tallied over a third of the team’s home runs by himself.

Well then. 1973 Giants:

Player A: .283 BA, 39 HR, 96 RBI, 148 K

Player B: .203 BA, 24 HR, 55 RBI, 122 SO

Player C: .319 BA, 11 HR, 76 RBI, 73 SO

Did you say Player A? Those certainly look like Kingman-level statistics, but in fact they are not; that’s what Bobby Bonds did for the Giants that year. Kingman is Player B, and Garry Maddox is Player C. Kingman still has a low batting average and a few home runs, and a ton of strikeouts, but Bonds showed a lot more power that year. This doesn’t invalidate the process, mind you; it just shows that we need to be careful.

Another important note; context here is super-important. If you take Kingman out of the baseball context, and just posit him as someone who travels the country like Jack Reacher, well, his travel pattern looks pretty odd. He starts out in San Francisco, on the National League circuit, and then a few years later shows up in New York, and then there’s the one year where he ends up playing for four different teams, one of them being the Yankees for some reason. And then he goes to Chicago, and then back to the Mets, and then Oakland. If you look at what’s basically fifteen years of travel plans without knowing that Kingman was a baseball player, you’d have thought that he was a traveling salesman. (The Man from the Train has his own pattern of peregrination, one that James explains as being consistent with his supposed job as a logger, or miner.)

The job that James has in working backwards on finding instances where The Man from the Train smashed people over the head with an ax is (as he explains) quite a bit easier. There are a lot of people playing big-league baseball at any one point in time; there are not a lot of people who go around murdering families in their beds — so there’s less statistical noise to look at. We’re looking at Kingman exhibiting only a few behaviors (striking out a lot, hitting home runs, not walking, not stealing bases). James has identified thirty some-odd key behaviors related to The Man from the Train, ranging from the time of day of the attacks to covering up mirrors in the house with cloth for some reason. (I will warn you that you will know far, far too much about the signature behaviors of the Man from the Train by the end of the book.)

James is using the book, I think, to make three key points:

Illustrating the power of modern analytical tools — in this case, online databases of old newspapers. This allows Bill and Rachel (mostly Rachel, one suspects) to go through and find data on crimes from over a hundred years ago and link them to their behavioral profile of The Man from The Train — informational tools that weren’t available to local law enforcement (what there was of it) at the time. However, when you’re dealing with press coverage from a hundred years ago… you’re dealing with press coverage from a hundred years ago. Most of it is incomplete, a lot of it is biased, and a good bit of it is just as racist as it could possibly be.Illustrating the power of behavioral analysis. James has, essentially, made a career out of this, pointing out that a lot of the things that “everybody knows” about baseball isn’t based on behavioral evidence. To the extent that THE MAN FROM THE TRAIN is focused just on the killer’s behaviors, it’s an excellent read. But (as I just said) the record he is looking at is necessarily incomplete, and James, for the sake of narrative coherence, is always throwing in suppositions about the killer’s state of mind; why he did this-and-that instead of thus-and-so, whether he liked cold weather or not, stuff that is just pure conjecture. I think that this, up to a point, is kind of necessary and unavoidable — we can’t help but impose narratives on chaos, it’s what we do. (James even says at one point, hey, you can have conjecture, or you can have nothing.) But it’s a contradictory approach, and it can make for a frustrating read.In kind of a backhanded way, THE MAN FROM THE TRAIN is about the limits of behavioral analysis. The only way that this book works is because the Man from the Train has a) behaviors that get documented in the newspapers, which in turn got archived; b) behaviors that are on the extreme edge of human experience; c) rather a lot of very distinctive, idiosyncratic behaviors that are easily identifiable and d) a lot of specific data points to look at. But even then — even with a highly organized serial killer with very specific behaviors — there’s a certain level of inconsistency about the whole thing.

It is this third thing that bugs me the most about THE MAN FROM THE TRAIN, and I think it will bother most readers. James spends half the entire book setting up this laundry list of behaviors exhibited by his killer, and then has to spend the other half of the book explaining away inconsistencies. At first, this was kind of maddening. The Man from the Train kills people who lives near railroads — except for this one family who lived in Alabama, far from the railroad. The Man from the Train kills families with prepubescent girls — except for the times that he doesn’t. The Man from the Train kills people in small towns, except for the one time he killed those people in San Antonio, so we have to explain that away, too.

(Come to think of it, this is largely the plot of GRANT, the Ron Chernow biography, where Chernow spends half the book trying to figure out whether a certain time in General Grant’s life coincides with his usual behavioral pattern of alcoholic binges. That got repetitive, too.)

The key to understanding this is that the Man from the Train had just so many of these behaviors — James counts thirty or so — and, well, even if you have thirty personally idiosyncratic behaviors, you don’t do them all every day, do you? There’s always some inconsistency. And people change — the Man from the Train changes his pattern over time, moving out of the Southeast and killing people in the Midwest and Northwest.

Like I said, this is an un-review, and I am not going to do the thing you do in book reviews where I tell you to read the book or not. You make the call. I did not enjoy THE MAN FROM THE TRAIN, but it was a book that I had to wrestle with a good deal, and it’s always a good idea to read books like that from time to time. (I liked POPULAR CRIME a good deal more, despite James’s insistence that President Kennedy was shot by accident by a Secret Service agent, which would be a trillion-to-one coincidence — a shot that the agent probably couldn’t make if he tried.) If you find James’s signature barstool know-it-all ratchetmouth style unappealing, go read something else.

May 23, 2018

Bill James, Dave Kingman, and “The Man from the Train.”

This is a not-review of THE MAN FROM THE TRAIN, by Bill James and Rachel McCarthy James. (I do not for one minute want to discount the role of Rachel McCarthy James in writing this book, but the book is delivered in Bill James’s inimitable voice, and so I’m going to primarily focus on him, okay?) This is a not-review, because I’m focusing not so much on the book itself, which is (necessarily) repetitive, badly disorganized, and focuses on truly awful carnage. I want to focus on the big idea in the book, which is behavioral analysis. It’s a simple enough term; behavioral analysis focuses on what people do, and not the reasons behind what they do, or their justifications or excuses for why people do what they do.

All I am saying is that the font size for Bill’s name is a lot bigger for a reason.

All I am saying is that the font size for Bill’s name is a lot bigger for a reason.James uses the super-extreme example of a person he identifies as “The Man from the Train,” who James suspects of killing hundreds of people across America in the early years of the twentieth century by breaking into their houses and bashing their skulls in with the blunt end of an ax. Okay, so that’s a behavior. We’re doing behavioral analysis, so we’re looking at what this guy does, not what sick, perverted fantasies drive him to do this.

But you know, as much as you might enjoy reading about The Man from the Train, the whole thing gets so gruesome so quickly that talking about it is kind of tiresome, and if you’ve read the book, you’re likely sick of it, and if you haven’t, you’ve got a lot of stories about kids getting their faces smashed in ahead of you, so instead let’s talk about Dave Kingman.

This guy. Not some other Dave Kingman, Just so we’re clear.

This guy. Not some other Dave Kingman, Just so we’re clear.Why Dave Kingman? Well, The Man from the Train was a strong guy who roamed around the country hitting people with an ax; Dave Kingman was a strong guy who traveled around the country destroying baseballs with baseball bats. It’s a thin connection, but I’m going with it. Anyway, it’s a lot more fun talking about Dave Kingman.

The important thing in behavioral analysis is understanding what a trait is and what a behavior is. Dave Kingman was a guy who played baseball a lot differently from most people, and he was a guy who had a lot of traits, and those traits get used to explain his behavior a lot. Example:

And in New York the much-publicized Dave Kingman character came out — here was the moody Kingman who swung hard at everything, who almost never walked, who pulled everything, who hit 500-foot home runs and 325-foot pop-ups, who ran the bases like a child coming in for dinner, who played defense not just poorly but with utter disdain. — Joe Posnanski, Sports Illustrated, 2008

So some of that is traits: “moody” is a trait, “disdain” is a trait. Wanting to hit every ball that you see 500 feet is a trait; it ties in with impatience and maybe being a little bit of a glory hound. But a lot of these are behaviors; swinging at everything is a behavior, no matter why Kingman did it, playing defense poorly is a behavior.

This is a good example of what I’m talking about. Charlie Brown misses the catch because of his traits, right? But all the official scorer cares about is his behavior — that he dropped the ball. (Baseball, you understand, is the sport that counts your errors, and punishes you for them in the box score.)

This is a good example of what I’m talking about. Charlie Brown misses the catch because of his traits, right? But all the official scorer cares about is his behavior — that he dropped the ball. (Baseball, you understand, is the sport that counts your errors, and punishes you for them in the box score.)One reason why baseball is such a great game is that it melds traits and behaviors. We are attracted to baseball partly because it’s a narrative sport that incorporates the traits of the players — the struggling pitcher who makes good on the game’s biggest stage, the slugger who comes through in the bottom of the ninth, the slick-fielding rookie who turns heads making an impossible double play. But it’s also the most behavioral and analytical of the sports, where everything anyone does is documented and available for analysis. It appeals to the half of our brain that loves stories and the half of our brain that loves numbers.

So when we go to the great and noble Baseball Reference and look up Dave Kingman, you get

.236 BA, .302 OPB, .478 SLG, 442 HR, 1210 RBI, 1816 Ks.

Okay, you can look at those numbers (assuming you know what the numbers mean) and say, “Yeah, that looks like Dave Kingman.” A lot of power — 442 career home runs — but a lot more strikeouts, and a lousy batting average and on-base percentage. That tells you a lot about Kingman’s behaviors — he swung a lot, and missed a lot, but when he connected, the ball went over the fence.

James makes the point that we knew a lot about ballplayers like Kingman at the time, but we know even more about them now, because we have access to the sort of advanced statistical tools that James and others invented. We know more about Kingman than his contemporaries did — we know information about Kingman that he never knew about himself, information that’s only available through modern insights like Value Over Replacement Player statistics, or through the application of modern information technology analytical tools.

So the question in THE MAN FROM THE TRAIN is, well, we have technology and analytics at our disposal now. Can we go back and look at the data that they had then, re-evaluate it, and come up with a recognizable pattern? And once we have that pattern, can we reverse-engineer it to find our serial killer?

To give you an idea about what’s involved, let’s try a thought experiment. I am going to give you the statistics of three players from the 1979 Chicago Cubs; you tell me which of them is Dave Kingman:

Player A: .288 BA, 48 HR, 115 RBI, 131 K

Player B: .272 BA, 19 HR, 73 RBI, 85 K

Player C: .284 BA, 14 HR, 66 RBI, 28 K

Which one is it? It isn’t a trick question; Player A is Kingman. (Player B is Jerry Martin, Player C is Bill Buckner.)

Right? I mean, this is obviously Kingman, you can tell from the high levels of home runs and strikeouts. This was Kingman’s career year; his batting average was fifty points over his career average, and somehow he drew 45 walks, third on the team behind Ivan de Jesus and Steve Ontiveros . (This may be a function of intentional walks, though.) So far, so good, we can find a set of behaviors in a specific year that lines up well with Kingman’s known behaviors.

So what we’ve shown so far is that we can pick Kingman, basically, out of a lineup. Let’s try again. 1976 Mets:

Player A: .238 BA, 37 HR, 86 RBI, 135 K

Player B: .292 BA, 10 HR, 49 RBI, 38 K

Player C: .306 BA, 5 HR, 31 RBI, 35 K

Again, super-easy. Player A is Kingman, Player B is Ed Kranepool, Player C is Joe Torre. This is maybe a little easier because, well, there weren’t any other players with power on the 1976 Mets; Kingman tallied over a third of the team’s home runs by himself.

Well then. 1973 Giants:

Player A: .283 BA, 39 HR, 96 RBI, 148 K

Player B: .203 BA, 24 HR, 55 RBI, 122 SO

Player C: .319 BA, 11 HR, 76 RBI, 73 SO

Did you say Player A? Those certainly look like Kingman-level statistics, but in fact they are not; that’s what Bobby Bonds did for the Giants that year. Kingman is Player B, and Garry Maddox is Player C. Kingman still has a low batting average and a few home runs, and a ton of strikeouts, but Bonds showed a lot more power that year. This doesn’t invalidate the process, mind you; it just shows that we need to be careful.

Another important note; context here is super-important. If you take Kingman out of the baseball context, and just posit him as someone who travels the country like Jack Reacher, well, his travel pattern looks pretty odd. He starts out in San Francisco, on the National League circuit, and then a few years later shows up in New York, and then there’s the one year where he ends up playing for four different teams, one of them being the Yankees for some reason. And then he goes to Chicago, and then back to the Mets, and then Oakland. If you look at what’s basically fifteen years of travel plans without knowing that Kingman was a baseball player, you’d have thought that he was a traveling salesman. (The Man from the Train has his own pattern of peregrination, one that James explains as being consistent with his supposed job as a logger, or miner.)

The job that James has in working backwards on finding instances where The Man from the Train smashed people over the head with an ax is (as he explains) quite a bit easier. There are a lot of people playing big-league baseball at any one point in time; there are not a lot of people who go around murdering families in their beds — so there’s less statistical noise to look at. We’re looking at Kingman exhibiting only a few behaviors (striking out a lot, hitting home runs, not walking, not stealing bases). James has identified thirty some-odd key behaviors related to The Man from the Train, ranging from the time of day of the attacks to covering up mirrors in the house with cloth for some reason. (I will warn you that you will know far, far too much about the signature behaviors of the Man from the Train by the end of the book.)

James is using the book, I think, to make three key points:

Illustrating the power of modern analytical tools — in this case, online databases of old newspapers. This allows Bill and Rachel (mostly Rachel, one suspects) to go through and find data on crimes from over a hundred years ago and link them to their behavioral profile of The Man from The Train — informational tools that weren’t available to local law enforcement (what there was of it) at the time. However, when you’re dealing with press coverage from a hundred years ago… you’re dealing with press coverage from a hundred years ago. Most of it is incomplete, a lot of it is biased, and a good bit of it is just as racist as it could possibly be.

Illustrating the power of behavioral analysis. James has, essentially, made a career out of this, pointing out that a lot of the things that “everybody knows” about baseball isn’t based on behavioral evidence. To the extent that THE MAN FROM THE TRAIN is focused just on the killer’s behaviors, it’s an excellent read. But (as I just said) the record he is looking at is necessarily incomplete, and James, for the sake of narrative coherence, is always throwing in suppositions about the killer’s state of mind; why he did this-and-that instead of thus-and-so, whether he liked cold weather or not, stuff that is just pure conjecture. I think that this, up to a point, is kind of necessary and unavoidable — we can’t help but impose narratives on chaos, it’s what we do. (James even says at one point, hey, you can have conjecture, or you can have nothing.) But it’s a contradictory approach, and it can make for a frustrating read.

In kind of a backhanded way, THE MAN FROM THE TRAIN is about the limits of behavioral analysis. The only way that this book works is because the Man from the Train has a) behaviors that get documented in the newspapers, which in turn got archived; b) behaviors that are on the extreme edge of human experience; c) rather a lot of very distinctive, idiosyncratic behaviors that are easily identifiable and d) a lot of specific data points to look at. But even then — even with a highly organized serial killer with very specific behaviors — there’s a certain level of inconsistency about the whole thing.

It is this third thing that bugs me the most about THE MAN FROM THE TRAIN, and I think it will bother most readers. James spends half the entire book setting up this laundry list of behaviors exhibited by his killer, and then has to spend the other half of the book explaining away inconsistencies. At first, this was kind of maddening. The Man from the Train kills people who lives near railroads — except for this one family who lived in Alabama, far from the railroad. The Man from the Train kills families with prepubescent girls — except for the times that he doesn’t. The Man from the Train kills people in small towns, except for the one time he killed those people in San Antonio, so we have to explain that away, too.

(Come to think of it, this is largely the plot of GRANT, the Ron Chernow biography, where Chernow spends half the book trying to figure out whether a certain time in General Grant’s life coincides with his usual behavioral pattern of alcoholic binges. That got repetitive, too.)

The key to understanding this is that the Man from the Train had just so many of these behaviors — James counts thirty or so — and, well, even if you have thirty personally idiosyncratic behaviors, you don’t do them all every day, do you? There’s always some inconsistency. And people change — the Man from the Train changes his pattern over time, moving out of the Southeast and killing people in the Midwest and Northwest.