Stephen Morris's Blog, page 14

February 8, 2021

“…like the sun in all its brilliance”

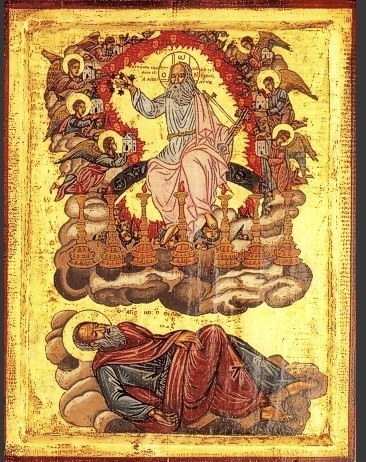

Christ in glory as described in the Apocalypse, surrounded by the four heavenly beasts which are emblematic of the four evangelists. The 8-pointed stars in the concentric heavenly spheres are iconographic shorthand for the Saints gathered around Christ.

Christ in glory as described in the Apocalypse, surrounded by the four heavenly beasts which are emblematic of the four evangelists. The 8-pointed stars in the concentric heavenly spheres are iconographic shorthand for the Saints gathered around Christ.“In his right hand he held seven stars, and coming out of his mouth was a sharp, double-edged sword. His face was like the sun shining in all its brilliance.” (Apoc. 1:16)

St. John describes his initial vision of Christ in the Apocalypse in terms very similar to the description of Christ at the Transfiguration in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Christ is shining more brilliant than the sun, in clothes more brilliantly white than possible on earth. The transfiguration itself is commonly associated with the End, the final Judgement and the revelation of the saints and righteous who will also shine more brilliantly than the sun. This “theosis” or “divinization” is also the common term for Greek-speaking Christians to describe salvation itself: by cooperation with God, the human person becomes like God and comes to share certain divine attributes–primarily love-charity. This assimilation of human to divinity is described in 2 Peter 1:4: “… that you may be partakers of the divine nature, having escaped the corruption that is in the world through lust.”

The seven stars in Christ’s hand are commonly seen painted–many times over!–on the ceilings of churches. These stars are not meant to be stars in the sky, as if the roof were invisible, but are artistic shorthand for painting the saints in the Kingdom of Heaven. Rather than painting a multitude of faces, the church is adorned with a multitude of stars just as the righteous are commonly described as stars in visionary literature.

The sword which is the word of God (Isaiah 49, Wisdom 18, Hebrews 4) is both text and person. The “word of God” in English is commonly understood to be text, the word(s) spoken by God while the “Word” of God is understood to be the Divine Person who was incarnate. These distinctions of upper-case and lower-case are all editorial choices based on the theological opinions of the editors or typesetters. But in the Greek manuscripts there were few–if any–distinctions between upper-case and lower-case letters so that each time the phrase “word of God” appears it would have been understood to be BOTH the text spoken and the Divine Person who was made flesh.

The post “…like the sun in all its brilliance” appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

February 1, 2021

“I hold the keys of Death and Hades …”

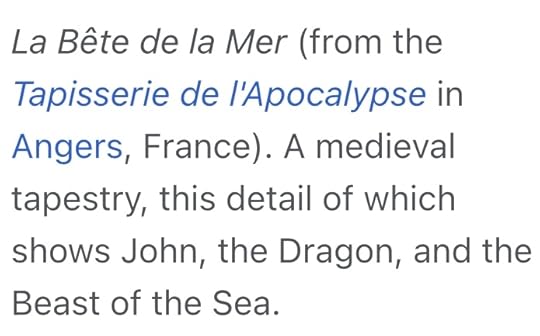

St. John, in the cave on Patmos, experiences his vision of Christ who holds 7 stars and the keys of Death and Hades-Hell as he is enthroned among the 7 candlesticks. The angels of the 7 churches offer the parishes they protect to Christ.

St. John, in the cave on Patmos, experiences his vision of Christ who holds 7 stars and the keys of Death and Hades-Hell as he is enthroned among the 7 candlesticks. The angels of the 7 churches offer the parishes they protect to Christ.“Do not be afraid. I am the First and the Last. I am the Living One; I was dead, and–behold!–I am alive for ever and ever! Amen. And I hold the keys of Death and Hades.” (Apocalypse 1:17-18)

In the opening chapter of the Apocalypse, the phrase “I am the First and the Last” is a refrain that occurs several times. First and Last, beginning and the end, alpha and omega (the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet). The original phrase seems to have been “the first and the last, the alpha and the omega;” the words “beginning and the end” seem to have been added in the Latin manuscripts to explain what “alpha” and “omega” were to readers who didn’t know Greek. The phrase is also similar to the famous Ego emi… (“I Am….”) phrases in the Gospel According to St. John: I am the true bread… I am the good shepherd… I am the true vine… etc.

“I am the Living One” is also reminiscent of the Old Testament identification of “the Living God” (Deut. 5:26, Joshua 3:10, Isaiah 37:4, 17). The one who appears to St. John in Patmos is the same Divine Person who revealed himself to Moses at the Burning Bush and repeatedly to the kings and prophets of Israel.

Death and Hades-Hell (Sheol, in some versions) can be understood as two names for the same thing (the experience of separation from God). Hebrew poetry is built on this repetition of ideas and experiences. Many of the psalms repeat themselves in this way.

But Death and Hades are also personified in Apoc. 6:8 as one of the famous Four Horsemen: the fourth rider, who rides a pale horse, is named “Death and Hades.” Early Christian preaching–reflected in the Gospel of Nicodemus–identified Death and Hades as two distinct personages who oversee the land of the dead; they argue as Christ approaches and are overthrown as Christ leads their prisoners to freedom through the gates he has smashed during his Descent into Hell. Some early Christian poetry identify “Death” as a person whiles “Hades” is the place where Death reigns.

Gregory Nanzianzus, commonly known as Gregory the Theologian, thought that the two names Death and Hades referred to the physical and spiritual aspects of death–the result of separation from God. A person can die spiritually many years before they experience death physically–Adam and Eve are examples of people who die spiritually long before their bodies die. Likewise, in baptism people can experience spiritual resurrection before they experience physical resurrection.

The post “I hold the keys of Death and Hades …” appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

January 26, 2021

Many Faces of Antichrist

The figure of the Antichrist appears in several places in the New Testament before he appears in the Apocalypse (Book of Revelation). In the first epistle of St. John, we read Children, it is the last hour; and as you have heard that antichrist is coming, so now many antichrists have come; therefore we know that it is the last hour.” (1 John 2:18) The antichrists are those who oppose the apostle’s teaching. They are the heretics (lit. “the choosers”) who choose a different teaching and place themselves in opposition to the Church.

In the 2nd epistle to the Thessalonians, the antichrist is the “man of lawlessness” (2 Thess. 2:3-10) who opposes peace, order, and harmony–both civil and ecclesiastical. The seven-headed, ten-crowned dragon of the Apocalypse is typically identified with this “man of lawlessness,” the Antichrist. The dragon deceives and destroys, confusing and laying waste to the Church and the known world.

St. Paul makes the cryptic remark: “… the mystery of lawlessness is already at work; only he who now restrains it will do so until he is out of the way.” (2 Thess. 2:7) Who restrains the Antichrist? St. Paul seems to presume that his readers know but later readers have had to surmise. Even St. Augustine threw up his hands and exclaimed, “I admit that the meaning of this completely escapes me.” (City of God, Book 20, chapter 19)

St. John Chrysostom considered the Antichrist to be the personification of chaos and destruction. It was the power of Rome (even in her pagan days) that kept complete anarchy and destruction at bay. Chrysostom thought of himself as a “Roman” living in the “New Rome” of the ongoing Roman Empire that continued to constrain the Antichrist. Many early fathers and preachers agreed with him and would probably say that “that which restrains the Antichrist” continued to do so until 1917-1918, when Austro-Hungary and imperial Russia–the last two governments to see themselves as the continuation of the Roman Empire–finally collapsed or were overthrown.

The idea that imperial rule kept the world safe from evil is ancient. In the Old Testament, it seems that the ancient Israelites thought the kings of Israel were the “first line of defense” against the evil angels. (For more about this, see Margaret Barker‘s book, The Last Prophet.)

The post Many Faces of Antichrist appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

January 18, 2021

Proskynesis and Apocalypse

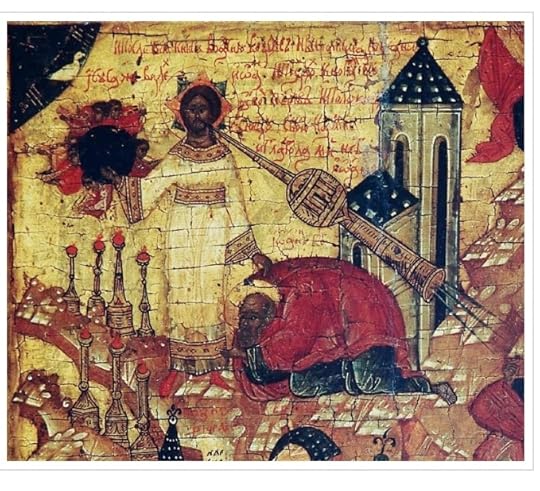

We see Jesus standing with an 8-pointed star behind his head, emblematic of “eternity,” in this iconographic depiction of the first chapter of the Apocalypse. Christ appears in gleaming white priestly vestments, shining more brightly than the sun much as he is described as appearing at the Transfiguration on Mt. Tabor. Transfiguration, in patristic sermons, is seen as an anticipation of the End and a foretaste of the Apocalypse. Transfiguration reveals the goal and intended destination of humanity in communion with God. St. John, who saw Christ transfigured on Tabor, recognizes Christ transfigured again on Patmos.

The Apostle John makes a proskynesis (“prostration “) before Christ. Christ’s voice, which is described as sounding like a trumpet blast, is depicted by the elaborate trumpet coming from his mouth. We see the seven lamps depicted as candlesticks at Christ’s side. It became customary in the Christian West to always have seven candlesticks on the altar when the bishop celebrates the Eucharist.

The proskynesis, or “prostration,” is a gesture that appears many times throughout the Old and New Testaments. The prophet Daniel makes a proskynesis (Daniel 8:17; 10:7-9) while Joshua made a proskynesis to an angel (Joshua 5:14) and when King Solomon dedicated the Temple, the priests all make a proskynesis when the glory of God fills the newly-dedicated Temple.

Proskynesis is frequently translated “worship” in English Bibles but—according to the 7th ecumenical council—technically speaking proskynesis is precisely not worship. It is an act of honor, of reverence, of veneration. But not worship. Proskynesis is an act of veneration appropriate to make towards holy things—the altar, relics, icons—but it is not worship which is appropriate to offer only to God. Worship may include an act of proskynesis but proskynesis is not limited to acts of worship.

The post Proskynesis and Apocalypse appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

January 11, 2021

Top Posts in 2020

The Tower, one of the Major Arcana of the Tarot deck, is associated with challenges or sudden, unexpected changes which can be seen as disasters (if we chose to see them like that). Doesn’t that just about perfectly sum up 2020, the year we have all just gone through?

The Tower, one of the Major Arcana of the Tarot deck, is associated with challenges or sudden, unexpected changes which can be seen as disasters (if we chose to see them like that). Doesn’t that just about perfectly sum up 2020, the year we have all just gone through?What were the most popular posts here in 2020? There were many posts that might be included in the category of “Most Popular” but these posts were far and away the ones that generated the most interest.

In chronological order, as they were published this past year:

Lent is Coming …. view here

When the Mother of God Went to Hell …. view here

St. Mary Major and the Miracle of the Snow… view here

Archangel Uriel …. view here

San Apollinaire in Ravenna and the Magi … view here

“I am Black and Beautiful:” The Queen of the South … view here

Frankincense … view here

Thank you, readers, for your continued interest! It means so much to me to know that people take the time to read this blog on a regular basis and are actually interested in what I might have to say each week. Looking forward to 2021 with you!

The post Top Posts in 2020 appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

December 7, 2020

I am Wounded with Love

The heart of the Mother of God is pierced by sorrows because she loves God; although St. Simeon foretold when Christ was 40 days old that his mother’s heart would be pierced by sorrow, the classic Christian belief is that her heart had already been pierced by love for God from the day she was born. This icon is also known as the “Softener of Evil Hearts” as the Mother of God can soften/pierce the hearts of those whose hearts are stony and unforgiving. Many pray before this icon to soften feelings of enmity that make it difficult to forgive others.

The heart of the Mother of God is pierced by sorrows because she loves God; although St. Simeon foretold when Christ was 40 days old that his mother’s heart would be pierced by sorrow, the classic Christian belief is that her heart had already been pierced by love for God from the day she was born. This icon is also known as the “Softener of Evil Hearts” as the Mother of God can soften/pierce the hearts of those whose hearts are stony and unforgiving. Many pray before this icon to soften feelings of enmity that make it difficult to forgive others. In Christ, that which is uncreated, eternal, existing before the ages, is completely inexpressible and incomprehensible to all created intellects. Yet that which was revealed in the flesh can to a certain extent be grasped by human understanding. It is towards this in Christ that the Church, our teacher, looks, and of this does she speak. inasmuch as this can be made intelligible to those who listen to her.

… he who sees the Church looks directly at Christ–Christ building and increasing by the addition of the elect. The bride then takes the veil from her eyes and with pure vision sees the ineffable beauty of her spouse. Thus she is wounded by a spiritual and fiery dart of desire. For love that intense is called desire. No one should be ashamed of this as the arrow comes from God…. the bride is proud of her wound for this desire has pierced her to the depths of her heart. This she makes clear when she says to the others, I am wounded with love (Song of Songs, 5:5).

(St. Gregory of Nyssa, On the Song of Songs)

The bride–who is always the Mother of God, the Church, and each believer personally–is wounded with love. Driven mad by desire for her divine bridegroom. Delirious with love. In this mad, intense desire for the groom she finds it possible to love all those whom he loves as well even though she may not even like them herself. In this all-encompassing love we see a little of the incomprehensible love of God.

Many mystics describe an experience of being pierced by love for God during their own personal prayer. But more important than being pierced in such a personal way and having a particular emotional experience during prayer is the ongoing living out day-to-day of the love which all believers are wounded by. All those who struggle in some way to see God or apprehend the truth of reality are pierced by this desire. This wound–this desire–should shape and motivate all our actions as go about our business and not be limited to a particular “quiet time” we have alone although those quiet times are vital to nurture and develop this ongoing wound of desire and love.

To see the Church–corporately and personally–wounded with love for God is to see Christ wounded with love for us.

The post I am Wounded with Love appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

November 30, 2020

Thy Rod and Thy Staff

Mary, the Mother of God, is identified with the Bride in the Song of Songs. As the bride, she is also the Church. Through her consent to bear Christ and through the prayers of the Church, Christ is in the midst of his people who can approach him in the Cup which overflows with blessing (Psalm 23).

Mary, the Mother of God, is identified with the Bride in the Song of Songs. As the bride, she is also the Church. Through her consent to bear Christ and through the prayers of the Church, Christ is in the midst of his people who can approach him in the Cup which overflows with blessing (Psalm 23).Thy rod and thy staff, they have comforted me. (Psalm 23) The great King David tells us that this rod causes a consolation, not a wound. Indeed, it is by this rod and staff that the divine table is prepared and all these other details as well: oil for the head, a cup of unmixed wine (for sober intoxication), the mercy of God that follows us so well, a long dwelling in the house of the Lord. These are the blessings implied by that sweet striking…. hence, that striking must be a good thing since it produces such an abundance of grace…. the divine rod, or staff, that brings comfort and cures by striking is the Spirit…. This shows us that the wounding of the bride, by which her veil is stripped off, is a grace. In this way the soul’s beauty is unveiled and not hidden under the mantle of darkness. (St. Gregory of Nyssa, On the Song of Songs)

Psalm 23 is associated with the Eucharist because not only does King David describe the table that the Lord prepares and the cup of blessing but because King David is said to have composed this psalm when he was hiding from King Saul, who was intent on murdering him. Hiding in the dry Judean wilderness, and on the brink of death without food or drink, he was miraculously saved by God, who nourished him with a taste of the World to Come. David gratefully burst out in song, describing the magnitude of his trust in God.

According to the traditional Jewish interpretation of the psalm, David alludes to how God provided for the Jews’ every need throughout their 40-year sojourn in the desert, and to how they will sing when God brings them back to the Promised Land; David sings, not just for himself, but for every Jew.

As Christians, we understand how King David sings for each of us as well, as we taste the food of the World to Come: the Bread of heaven and the Cup of salvation. We often read Psalm 23 either in thanksgiving after the Eucharist or in preparation before the celebration of the Eucharist.

St. Gregory of Nyssa points out that the rod and staff mentioned in the psalm are the sufferings of the faithful by which God strikes us in order to help us become more spiritually beautiful. Just as David was struck by affliction–running for his life and hiding in the desert as he and his followers nearly starved to death–we are also struck by various afflictions that are certainly hard to see as “good” as we experience them but which we can see later to have enabled us to experience the presence of God afresh. More deeply. More profoundly.

In some liturgical practices, these sufferings that lead us to experience God anew are summarized in the striking of the chest at the beginning of the Eucharist and again just before approaching Holy Communion. (St. Jerome remarked that the reason we strike our chest, rather than any other body part, is because the heart is the seat of all desires and it’s our desire to do our own will that causes suffering by dividing us most from the will of God.)

The shepherd’s staff–the Spirit of God–both wounds and heals. The wounds come, whether we want them or not. It is our choice to see them as the opportunity for healing.

The post Thy Rod and Thy Staff appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

November 23, 2020

Joy of all who sorrow

This Russian icon of the Mother of God, the “Joy of all who sorrow,” depicts the Mother of God holding Christ in one arm while holding a scepter aloft with her right hand. She receives the prayers of various groups of the needy, those in distress or sorrow: the elderly, the poor, the hungry, those naked and cold. They pray, certain that she and her Son will provide what they need. They receive these gifts from her and from the Church.

This Russian icon of the Mother of God, the “Joy of all who sorrow,” depicts the Mother of God holding Christ in one arm while holding a scepter aloft with her right hand. She receives the prayers of various groups of the needy, those in distress or sorrow: the elderly, the poor, the hungry, those naked and cold. They pray, certain that she and her Son will provide what they need. They receive these gifts from her and from the Church.“You have stolen my heart, my sister, my bride.” (Song of Songs 4:9)

“I think that the expression, You have stolen my heart, means the same as You have given us life or You have put heart in us. For the sake of clarity … I will call on the divine Apostle for an explanation of these mysteries. For he tells us, in writing to the Ephesians, about the great economy of salvation through the epiphany of God in the flesh, that the Church–the bride of Christ–reveals the manifold wonders and wisdom of God to the race of angels as well as to the human race…. If the Church is Christ’s body and he is the head of the Church, then it is his face we see on her. Perhaps this is what the friends of the Bridegroom saw when they were given heart: in her they see clearly what is otherwise invisible…. So the friends of the Bridegroom see the Sun of Justice by looking upon the face of the Church as though it were a pure mirror. Thus, the Bridegroom can be seen by his reflection.” (St. Gregory of Nyssa, On the Song of Songs)

Christ, the image (lit. icon) of the invisible God is seen in both his Body–the Church–and in his most holy mother. He continues to act in this world through both his mother–who gave him flesh–and his body, the community sustained by his Body and Blood.

It is too easy to forget that everything human about Christ comes from his mother Mary. His flesh is her flesh, his blood is her blood, his DNA is her DNA. When we see her, we see her Son; when we see him, we see his mother. And when we see him, we see the whole Christ–that includes his body throughout time and space. Wherever Christ is, there his whole body is. When we encounter him–whether in personal prayer at home or in liturgical prayer at church–we encounter ALL of him.

And when we encounter all of him, our hearts are stolen.

The post Joy of all who sorrow appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

November 16, 2020

“I am wounded with love”

Painter: Greek School 17/18th Century

Painter: Greek School 17/18th CenturyMedium: Tempera on panel

Location: National Museum of Fine Arts, Valletta, Malta

The bride says: “I am wounded with love.” (Song of Songs 2:5) She explains that the dart has gone right through her heart and the Bowman is love. We know that God is love (1 John 4:8) and that he sends forth his only begotten Son as his chosen arrow (Isaiah 49:2) to the elect, dipping … its tip in the Spirit of life. The arrow’s tip is faith and unites to the Bowman whomsoever it strikes. (St. Gregory of Nyssa, On the Song of Songs)

The bride in the Song is wounded by the arrow shot by the divine Bowman. The arrow, whose tip is dipped in the Spirit of life rather than the venom or poison common in the ancient world, binds her to the one who shot the arrow: God, the Father. Christ is the arrow and—unlike most arrows we are familiar with—this arrow’s wound does not kill; it causes the bride to live. Forever. Bound by faith and love to the Bowman who shot the arrow into the world, she shares the divine life of the Bowman (the Father), the arrow (Christ), and the Spirit.

The Mother of God, brought to the Temple when she was three years old, is presented by her parents to be brought up serving the Lord in his house. We see in the upper left hand corner of the icon the angel that brought her bread from heaven each day; this is a pictorial way of saying that she trusted in the Lord for her sustenance and support and so was capable of conceiving the one who is the true bread come down from heaven. This bread that she received from the angel united her in love to the giver of the Living Bread just as the arrow united the bride to the Bowman. The bread brought by the angel is spiritual sustenance just as the arrow’s point was said to be anointed with the Spirit.

Annunciation is the only time we read of in the Bible when the first words out an angel’s mouth were not “Don’t be afraid! Fear not!” The daily visitation of the angel to bring bread to the Mother of God is also a way to explain why she was not shocked to see the angel Gabriel although she was shocked at the angel’s announcement.

The post “I am wounded with love” appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

November 9, 2020

Mother of God as Fortress and Incense

This icon, similar to the icon in Rome of the Mother of God known as “Health/Salvation of the Roman People,” illustrates the Song of Songs 4:4, which reads, “Like the Tower of David is your neck … a thousand shields hang upon it, all arrows of the mighty.”

This icon, similar to the icon in Rome of the Mother of God known as “Health/Salvation of the Roman People,” illustrates the Song of Songs 4:4, which reads, “Like the Tower of David is your neck … a thousand shields hang upon it, all arrows of the mighty.” “Who is she that goes up from the desert, as a pillar of smoke of aromatic spices–of myrrh and frankincense and all the perfumer’s powders?” (Song of Songs 3:6)

The friends of the groom are surprised by what they see, St. Gregory of Nyssa tells us. They know she is beautiful more splendid than gold or silver. But now they see her ascending and are struck with amazement and compare her beauty and virtue to not just a simple, single variety of incense but to a mixture of frankincense and myrrh together.

“One aspect of their praise is derived from the association of these two perfumes: myrrh is used for burying the dead and frankincense is used in divine worship…. a person must first become myrrh before being dedicated to the worship of God. That is, a person must be buried with Christ who assumed death for our sake and must mortify themselves with the myrrh–understood as repentance–which was used in the Lord’s burial.” (St. Gregory of Nyssa, On the Song of Songs)

A person must embrace ongoing self-examination and repentance; only then is it possible to then possible to enter the presence of God as the frankincense which is offered by the angels before the throne of God (Rev. 8:4).

Another of the spices used by perfumers was cinnamon. It was thought to have several remarkable properties, such as stopping putrefaction or infection and would cause a sleeping person to answer questions truthfully. So the application of “spiritual cinnamon” would stop anger, induce honest/truthful self-examination, and calm the anxious.

Myrrh and cinnamon were therefore metaphors for attitudes and practices that would protect a person from sin. In the Song, the bride–who was a type of the Mother of God–was not only myrrh and cinnamon but a protective fortress as well. The bride–in patristic sermons, the Mother of God–is a fortress with shields hanging from the battlements. The walls of the fortress are impervious to spears. The early fathers took this to mean that the prayers of the Mother of God could protect Christians from the darts and arrows of temptation. The fortress could also be seen as the Church herself, steadfast and immoveable on the rock of faith.

There were 18th century icons to illustrate this idea of the Mother of God as fortress; the inscription at the top of these icons was commonly:

“Like the Tower of David is your neck, built on courses of stone; a thousand shields hang upon it, all arrows of the mighty.” (Song of Songs 4:4)

In the example of this kind of icon seen above, the two saints appearing at the sides are additions generally not found in other versions. They are the Martyr Adrian and the Martyr Natalia. Some examples have instead the military saints such Alexander Nevsky at left, and George at right, but many have no saints added to the main image.

Much thanks to the Icons and Their Interpretation blog for information about this icon.

The post Mother of God as Fortress and Incense appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.