Stephen Morris's Blog, page 13

April 19, 2021

The Seven Seals

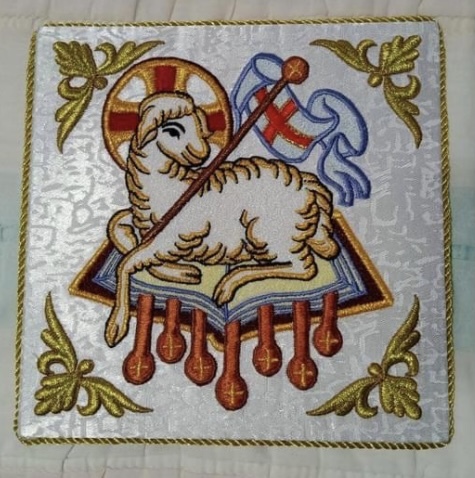

The Lamb of God and the book/scroll sealed with the seven seals, a popular motif embroidered on a variety of vestments and altar linens. Note that most depict the seven seals still unbroken although occasionally the seals are already open.

The Lamb of God and the book/scroll sealed with the seven seals, a popular motif embroidered on a variety of vestments and altar linens. Note that most depict the seven seals still unbroken although occasionally the seals are already open.I watched as the Lamb broke the first of the seven seals and …. as I watched, there was a pale horse. Its riders name was Death and Hades followed with him. (Apocalypse 6:1-8)

The book/scroll with the seven seals is among the most well-known images from the Apocalypse. Even if people don’t know the biblical source of the image, they at least know about the last, the Seventh Seal, from the famous movie by Ingmar Bergman. The seals and the riders or other visions that are revealed as each seal is broken have appeared many times in books and movies, whether in Agatha Christie mysteries or horror-fantasies or even comedies.

The seals reveal aspects of the liturgy–such as the relics of the martyrs contained in the altars on which the Eucharist is celebrated–as well as aspects of life that are judged by liturgical participation throughout history. Famine, plague, pestilence, and misery are constants throughout human experience. Many expect these to become especially intense just before the world ends; because of this, when these experiences have become intense in the past, many people expected that the world was about to come to an end.

Everyone loves to calculate and predict when exactly the End will come. Even St. Augustine has to tell his congregation, “Give your fingers a rest!” when they spend too much time and energy doing complicated math problems, trying to figure out when exactly the apocalypse will come. (Full disclosure: I still depend on my fingers to do even simple math problems!)

But it has not yet come to an end.

But the world does come to an end each time we celebrate the Eucharist and take our places in the eternal Kingdom of God. The apocalypse happens every time we proclaim, “Blessed is the Kingdom of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.”

The apocalypsehappens every time we lift up our hearts.

The apocalypsehappens every time we ask the Father to send down the Holy Spirit on us and onthese Holy Gifts of bread and wine.

The apocalypse happens every time we say, “Our Father… thy kingdom come.”

The apocalypse happens every time because the Holy Spirit lifts us up from earth to heaven to see Christ revealed in all his glory.

When will the seals be broken? They are always being broken, throughout time (during what we call “secular” history) and eternally (in the celebration of the Eucharist).

The post The Seven Seals appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

April 12, 2021

A New Song

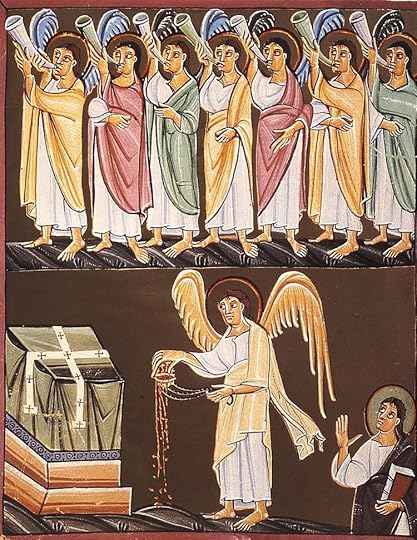

The seventh angel of the Apocalypse (illumination approx. 1180)

The seventh angel of the Apocalypse (illumination approx. 1180)And they sang a new song, saying: “You are worthy to take the scroll and to open its seals, because you were slain, and with your blood you purchased for God persons from every tribe and language and people and nation.” (Apocalypse 5:9)

The angels lead the singing of the “new song” around the Throne of God. Several times, the “new song” is mentioned in the Apocalypse, together with many other “new” things — a new name, a new heaven and a new earth, the New Jerusalem. These “new” things are not simply more recent than what they replace but are different in quality as well. The “newness” is a description of their character and purity as well as their permanence. They will not be replaced or supplanted, much like the “new covenant-testament” established by Christ at the Last Supper.

The psalms frequently mention a “new song” as well — Psalms 33, 40, 96, 98, 144, 149. Again, the “new song” is an eschatological hymn, a song to be sung at the End of Days when God’s people are vindicated and God’s final triumph is celebrated. But what is the “old song” that the new one is being contrasted with? The “old song” — maybe, the “first song” is a better way to describe it–is the Song of Miriam and Moses that God’s people sang on the shore of the Red Sea after escaping from Egypt. This song that celebrates the Exodus is also a celebration of God’s victory and the vindication of his people; it is a dress rehearsal for the victory God will win over his cosmic enemies at the End of Days.

During the Middle Ages, it was common for rabbis to identify the “old-first song” as the song sung when King Solomon dedicated the Temple in Jerusalem and the “new song” being that which was sung when the Temple was rebuilt and rededicated after the people returned from exile in Babylon. This can also be understood as a hymn sung to celebrate God’s deliverance of his people from their enemies and his re-establishment of them in the Promised Land.

The post A New Song appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

April 5, 2021

Christ is risen!

Harrowing of Hell/Resurrection icon from an iconostasis in a church on Crete. Kings David and Solomon with St. John the Baptist stand behind Adam. Old Testament prophets stand behind Eve.

Harrowing of Hell/Resurrection icon from an iconostasis in a church on Crete. Kings David and Solomon with St. John the Baptist stand behind Adam. Old Testament prophets stand behind Eve.Are there any who are devout lovers of God?

Let them enjoy this bright and beautiful festival!

Are there anywho are grateful servants?

Let them rejoice and enter rejoicing into the joy of their Lord!

….The Lord gives rest to those who come at the eleventh hour,

as well as to those who toiled from the beginning. For the Lord is gracious and receives the last even as the first.

To one and all the Lord gives generously.

The Lord accepts the offering of every work.

He honors every deed and commends the intention.

Let us all enterinto the joy of the Lord!

First and last alike, receive your reward.

Rich and poor, rejoice together!

Conscientiousand lazy, celebrate the day!

You that have kept the fast, and you that have not,

rejoice today, for the table—the altar of the Lord—is richly laden!

Feast royally, for the calf is fatted.

Let no one go away hungry.

Partake, everyone, of the banquet of faith.

Enjoy all the riches of his goodness!

Let no one grieve because of their poverty,

for the universal Kingdom has been revealed.

Let no onelament that they have fallen again and again,

for forgiveness has risen from the grave.

Let no one feardeath,

for the Savior’s death has set us free.

He destroyedDeath by enduring death.

He descended into Hades and took it captive.

It was in turmoil as soon as it tasted his flesh.

Isaiah—in chapter 14—foretold this when he said, “Hell was in turmoil when it encountered him in the lower regions.”

It was in turmoil because it was abolished.

It was in turmoil because it was mocked.

It was inturmoil because it was slain.

It was in turmoil for it was eclipsed.

It was in turmoil for it was annihilated.

It was in turmoil for it was wrapped in chains.

Hell took a corpse, and met God face to face.

It seized earth and encountered heaven.

Hell took what was seen and was overcome by what was unseen.

O death, where is your sting?

O hell, where is your victory?

Christ is risen and you are overthrown!

Christ is risen and the demons are fallen!

Christ is risen and the angels rejoice!

Christ is risen and life reigns!

Christ is risen and not one (of the) dead remains in the grave.

For Christ, beingrisen from the dead,

is become the first-fruits of those who have fallen asleep.

To Him be gloryand dominion forever and ever.

Amen!

(Paschal homily attributed to St. John Chrysostom)

The post Christ is risen! appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

March 29, 2021

Can These Bones Live?

From left to right: three figures represent Ezekiel being set down by God`s hand among the Dry Bones, hearing God and witnessing the beginning of the resurrection. Over a split mountain, littered with destroyed buildings and body parts, are two additional hands of God.

From left to right: three figures represent Ezekiel being set down by God`s hand among the Dry Bones, hearing God and witnessing the beginning of the resurrection. Over a split mountain, littered with destroyed buildings and body parts, are two additional hands of God.(Dura Europas Synagogue fresco in the National Museum of Syria, Damascus)

“Son of man, can these bones live?” (Ezekiel 37)

Ezekielheard the dry bones rattle, saw them come together to form skeletons, saw thesinews and tendons grow and stretch. He saw the flesh that spread to coverthem. And then he prophesied to the wind and called it to come, to fill thelungs of the dead. He saw the dead raised, the People of God restored,reconstituted, made whole. More than simple resuscitation—which only delayeddeath—he saw the dead resurrected. If they were resurrected, never to dieagain, that meant that Death itself was dead.

St. Ambrose of Milan—and most contemporaryBiblical scholars as well, but my money is always with St. Ambrose—understoodEzekiel’s vision of dry bones (which occurred around 600 BC, just after thePeople of Israel had been taken to Babylon in exile) to mean two things: one,that Israel would be restored to their homeland. All the people who felt lost,hopeless would be revived and brought home, to where they belonged. It was apromise to the People as a whole, that although they were as good as dead inBabylon, God would eventually –on his own timetable—bring them home and givethem life again in the Promised Land.

Secondly, the resurrection of the drybones, says St. Ambrose, is also about the Resurrection of us all—each andevery one of us—that will occur at the End of Days. (Many Jewish teachers hadalso come to understand the dry bones in this way, about 100 years beforeChrist.) Israel restored and the human race raised. Not resuscitated. Resurrected.

And we do not have to wait for theEnd of Days to experience resurrection and come home. Because Death is alreadydead and is already losing its power. The dead are being raised every day. “ButDeath is not dead yet and the dead are not being raised every day,”reasonable people pointed out to St. Ambrose. But death is dead. Just as afarmer catches a chicken and cuts off its head, only to have the corpse get upand run around the farmyard, spouting blood and making a mess and scaring thekids before it finally collapses, Christ cut the head off Death when he who isLife itself died. Death—like that chicken—can still run around and make a mess andscare people but it is already dead and it will finally collapse altogether—justlike that already dead chicken—when Christ comes again in glory.

How do we experience Resurrection inadvance? The dead are raised and come home every time someone is baptized. Thedead are raised and come home every time we approach the altar to receive theBody of Christ—bread as dead and dry as those bones Ezekiel saw but which becomesthe living and life-giving Body of Christ. The dead are raised and come home everytime we actively disconnect from the things and behaviors which we use to hidefrom God and ourselves and our neighbors, the things and behaviors that tie us downto the fallen aspect of the world.

To live in Babylon is to live in the cemetery which is the fallen world and Jesus famously healed the possessed and destitute who lived in the cemeteries. But using Ezekiel’s voice, God promises Israel that he would deliver them from Babylon and bring them into the Promised Land; in Psalm 116, we sing, “I will walk in the presence of the Lord in the land of the living.” We understand the land of the living is the Promised Land. The living. Those raised from the dead. In a famous Byzantine church mosaic, we see Christ Himself identified as “the land of the living.” Because the land of the living is Christ himself, we see the land of the living anywhere Christ is—Heaven. The Church.

The post Can These Bones Live? appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

March 18, 2021

Angels and Deacons

On the left, we see angels-deacons in the Apocalypse blowing trumpets and emptying thuribles of coals and incense before the heavenly altar as St. john watches (illumination from the Bamberg Apocalypse). On the right, we see smoking thuribles in the hands of deacons during the celebration of the Eucharist on earth.

On the left, we see angels-deacons in the Apocalypse blowing trumpets and emptying thuribles of coals and incense before the heavenly altar as St. john watches (illumination from the Bamberg Apocalypse). On the right, we see smoking thuribles in the hands of deacons during the celebration of the Eucharist on earth.Then I saw a strong angel proclaiming with a loud voice, “Who is worthy to open the scroll and to loose its seals?” (Apocalypse 5:2)

We encounter many figures in the Apocalypse who are mysterious at best and confusing at worst or commonly misunderstood. Angels might seem to be one of the more easily understood figures of the Apocalypse but we should not jump to such conclusions so quickly.

When reading early Christian texts like the Apocalypse, it is a rule of thumb that the animals and monsters we meet are there to stand in for people that the original readers might recognize–for instance, Roman emperors like Nero. Human figures are to be understood as angelic beings–like the “young men in white” who announce that Christ is risen to the women who meet them at Christ’s tomb. But figures who are introduced as angels–who are they?

The angels in the Apocalypse are understood to be the deacons who serve at the eternal celebration of the Eucharist before the Throne of God, just as earthly deacons at the celebrations of the Eucharist were commonly understood to be angels, the “messengers” who announce the Gospel and the prayer intentions of the community and who make other liturgical announcements (such as “Let us bend our knees” or “Arise! Stand upright!” or “Bow your heads unto the Lord”) and who swing the censers-thuribles of smoking frankincense. The angels in the Apocalypse make similar announcements, such as calling forth the one worthy to open the scroll, and offering the incense that fills the air around the heavenly altar and the Throne of God. The angels-deacons of the Apocalypse tell the visionary author what to write and when to stand up or step forward.

The angel-deacons in the Apocalypse are also wearing vestments similar to those that earthly deacons wear during the celebration of the Eucharist: splendid tunics and sashes/stoles. (The stoles that earthly deacons wear are sometimes compared by early Christian liturgical commentaries with the wings of the angels, especially when the stoles are tied to one side to make the distribution of Holy Communion easier.)

Burning incense is one of the most important things angels-deacons do. The smell of incense is more than aroma therapy; it is profoundly theological. The sense of smell is an affirmation that we have bodies. Christ in his Incarnation came to save our entire being – body, soul, mind, and spirit, not just our intellects. The classical approach to Christian worship provides an embodied approach to worship.

Angelic figures in the Apocalypse are also sometimes compared to the eunuchs who function as imperial officials that keep the imperial system running. When the Apocalypse was written, eunuchs and angels were both thought to be asexual, beardless adults who served the imperial-heavenly court in a variety of ways–messengers, announcers, stenographers, record-keepers. Typically, eunuchs could not be ordained deacons but they could become monks.

Deacons! Angels! They coordinate the actions of the Eucharist on earth and in heaven, standing before the Throne and altar. They tell us what to do and when to do it. They burn the fragrant incense that nourishes the righteous and drives the devils away. They assist with the distribution of Holy Communion that also nourishes the faithful. They are one of the ways we unite what happens on earth with what happens eternally.

The post Angels and Deacons appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

March 15, 2021

“Heaven” in the Apocalypse

A 13th century Cluniac ivory carving of Christ in Majesty surrounded by the four living creatures. The four living creatures, each having six wings, were full of eyes around and within. And they do not rest day or night, saying:

A 13th century Cluniac ivory carving of Christ in Majesty surrounded by the four living creatures. The four living creatures, each having six wings, were full of eyes around and within. And they do not rest day or night, saying:“Holy, holy, holy,

Lord God Almighty,

Who was and is and is to come!”

The four living creatures reflect a combination of the cherubim in Ezekiel 1 and seraphim in Isaiah 6:2, they function as ‘the priests of heavenly temple’. Their song is an adaption of Isaiah 6:3.

“After this I looked, and lo, in heaven an open door!” (Apocalypse 4)

The vision of the heavenly throne room opens Chapter 4 of the Apocalypse; it is an interlude between the first two series-of-sevens of the book, the seven letters to the churches and the seven seals. (The series-of-sevens are the basic building block of the Apocalypse. Each series-of-seven tells the story of the Church’s journey through history from a different perspective or from another point of view. Each series becomes more intense but the Apocalypse does not tell a linear, sequential story; rather, it is a re-examination of the same story several times.)

The seer of the Apocalypse sees an open door in heaven. Most of us think of heaven as the eternal abode of God, the place of light and glory where the saints and angels stand before the Holy Trinity. We think that only Good exists in heaven. But that does not match the description of “heaven” in the Apocalypse.

Heaven, in the Apocalypse, is not eternal. It will be destroyed: “heaven and earth shall pass away,” we famously read. Heaven will cease. The eternal residence of God, we are told, is the New Jerusalem that will come down from out of heaven (chapter 21). There will be a new heaven and a new earth. Heaven, as it is currently constituted, will be replaced after the End of Days.

The “good” are not the sole residents of heaven. Evil dwells there with God. Spiritual realities and beings populate heaven–we meet the dragon and the rebel angels and the the beast with seven heads and ten horns, not just the four living creatures and the saints.

Rather than consider “heaven” as the equivalent of the Kingdom of God, we would do better to see heaven in the Apocalypse as the equivalent to “spiritual-invisible world.” It is this invisible world that we glimpse from a variety of angles in the different series-of-sevens that make up the Apocalypse. Each series-of-seven is true but it is not literal (as we understand that word in contemporary English).

I will be giving a talk on the Apocalypse this evening, Monday March 15 at 7 p.m. (New York City time) as part of the adult education series at St. Luke’s in the Fields. Join us here. A recording of the talk will also be available afterwards; the link will be posted on the Bible Study tab of this website.

The post “Heaven” in the Apocalypse appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

March 8, 2021

Jezebel and the Nicolaitans

Israel’s most accursed queen carefully fixes a pink rose in her red locks in John Byam Liston Shaw’s “Jezebel” from 1896. Jezebel’s reputation as the most dangerous seductress in the Bible stems from her final appearance: her husband King Ahab is dead; her son has been murdered by Jehu. As Jehu’s chariot races toward the palace to kill Jezebel, she “painted her eyes with kohl and dressed her hair, and she looked out of the window” (2 Kings 9:30). Image: Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum, Bournemouth, UK/Bridgeman Art Library.

Israel’s most accursed queen carefully fixes a pink rose in her red locks in John Byam Liston Shaw’s “Jezebel” from 1896. Jezebel’s reputation as the most dangerous seductress in the Bible stems from her final appearance: her husband King Ahab is dead; her son has been murdered by Jehu. As Jehu’s chariot races toward the palace to kill Jezebel, she “painted her eyes with kohl and dressed her hair, and she looked out of the window” (2 Kings 9:30). Image: Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum, Bournemouth, UK/Bridgeman Art Library.“Nevertheless, I have this against you: You tolerate that woman Jezebel, who calls herself a prophet.” (Apocalypse 2:20)

There is a woman in Thyatira who is a rival of St. John the Apostle. She teaches a group known as the Nicolaitans. She–and her followers–reject the authority of the St. John and disobey his teaching. He compares her to the Old Testament queen, Jezebel.

Jezebel appears in the Old Testament (2 Kings). She is the archenemy of the prophet Elijah. She teaches the people to commit adultery and practice sorcery. Tyconius–the first Biblical scholar to write a commentary on the Apocalypse–says that the figure of Jezebel in the Apocalypse “stands for the whole fallen order.” She is everything that stands in opposition to God. Always and everywhere, whatever opposes God is “Jezebel.” Tyconius also says that her followers, her “children,” can be seen as Goliath, who refused to admit the truth: that Israel’s God is the true God and that David was the one chosen by God to protect the people. Jezebel’s followers refuse to admit the truth: that the Apostle John is the authentic teacher chosen by God and serves as the protector of the Christian communities, as David was in the Old Testament.)

The woman in Thyatira that St. John was concerned was an “antinomian.” (That’s a fancy word that means “against the rules.” Antinomian groups always object to having to follow any rules.) She taught her followers that it didn’t matter what they ate or who they slept with or if they denied Christ when arrested by the Romans and were facing execution. (There was an antinomian faction among the Christians in Corinth, as well–people thought it didn’t matter what they ate or who they slept with.)

“Jezebel” in Thyatira told her followers to just blend in with mainstream society. St. John did not want the Christians to assimilate at all with the society in which they lived. “How much assimilation is acceptable?” was a difficult question that different Christian teachers answered in different ways in different places at different times.

The post Jezebel and the Nicolaitans appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

March 1, 2021

Balaam and the Nicolaitans

Left: Balaam and the angel. Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)

Left: Balaam and the angel. Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)Right: Balaam and the Ass, by Rembrandt van Rijn, (1626)

“There are some among you who hold to the teaching of Balaam, who taught … the Israelites to sin so that they ate food sacrificed to idols and committed sexual immorality.” (Apocalypse 2:14)

The gentile prophet Balaam appears in the Old Testament book of Numbers, chapters 22-24. He is hired by a pagan king to curse the Israelites before they can conquer the pagan king’s territory. Balaam warns the king that he cannot do anything the gods do not approve of; the king hires him anyway. Balaam attempts to curse the Israelites three times but each time his words become blessings for the Israelites. The king is furious.

The three blessings that Balaam pronounced over the Israelites were understood by the Israelites to refer to the Messiah, especially the third blessing: “A star will rise out of Jacob, a scepter shall rise out of Israel.” Christians often read this story at Christmas and Epiphany.

The story of Balaam and his donkey reports that as Balaam was going to a cliff that was near the Israelite camp–he wanted to look out over the Israelites as he tried to curse them–the donkey he was riding suddenly refused to walk any further. Balaam kept hitting the donkey, trying to force it to go forward. At least the donkey turned to him and said, “Don’t you see the angel blocking the road ahead?!” Shocked that the donkey spoke, he looked ahead and DID see the angle blocking the road. But the angel withdrew and allowed the donkey and Balaam to go forward although Balaam never was able to curse the Israelites. (Balaam’s donkey is one of the only two animals who are ever reported to speak in the Bible; the other one is the serpent in Eden.)

But in Numbers 25, we are told that the Israelites abandoned the true God and ate non-kosher food and engaged in a wide variety of sexual misbehavior. Later in Numbers, we read that Balaam and the pagan king taught the Israelites to do these things; they hoped that God would abandon the people if they disobeyed the commandments they had been given. (Since the king couldn’t get Balaam to curse the people, he tried this as a Plan B.) The plan worked: God struck the Israelites with a plague because of their disobedience. But they repented and eventually conquered the pagan king’s territory anyway.

The heretics in Asia Minor–false Christian teachers who instruct their followers to behave in ways St. John thinks are sinful–are compared to Balaam who taught the Israelites to disobey God even after he had blessed them and promised that the Messiah would appear among them.

The post Balaam and the Nicolaitans appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

February 22, 2021

Every Eye Shall See

Eve is born from the side of Adam.

Eve is born from the side of Adam.Left: Cathedral of Monreale, Sicily (built AD 1172-1267)

Right: Basilica of St. Mark, Venice (mosaic approx. 13th century)

“Every eye will see him, even those who pierced him, and all peoples on earth will mourn because of him.” (Apoc. 1:7)

The first chapter of the Apocalypse is the “cover letter” that was sent to accompany each of the seven letters to the seven churches, whose contents we read in chapters 2-3. This sentence quotes Zechariah 12:10, which is also quoted in the Gospel of St. John (19:37) in connection with Christ’s side being pierced by a spear as he hung on the Cross. The prophet in the Old Testament describes how God will share the suffering of His people in exile and that those who inflict this suffering will realize–too late?–who it is that they have been really tormenting. The gospel cites this allusion to illustrate how Christ is the fulfillment of all that Israel has been hoping for. In the Apocalypse, the true identity of the letter-writer–the true author who ‘dictates’ the letter to John, to be written down–is the same Christ who hung on the Cross and was pierced.

When Christ’s side was pierced on the Cross, blood and water poured forth. (Scientists report that the “water” was most likely hydropericardium, a clear fluid that collects around the heart during intense physical trauma.) Early Christians saw the piercing of Christ’s side as the birth of the Church. Just as Eve was born from Adam’s side as he slept in Paradise, many preachers and teachers said that the Church was born from the side of Christ as he “slept” on the Cross. Methodius of Olympus, a famous second century preacher and Biblical interpreter, said that “Christ slept in the ecstasy of his Passion and the Church–his bride–was brought forth from the wound in his side just as Eve was brought forth from the wound in the side of Adam.” The Church, the Bride of Christ, is often identified as the “new Eve” just as Christ is the New Adam. (In other contexts, the Mother of God is also identified as the New Eve. Both can be the New Eve, just as the Church and the Eucharist are both the Body of Christ–just in different manner and context.)

The blood and water that poured from Christ’s side are also considered signs of baptism and the Eucharist. Read selections from a sermon by St. John Chrysostom here about those images.

The post Every Eye Shall See appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

February 15, 2021

Blessed is the one who reads

St. John receives the heavenly message from an angel and then dictates it to his disciple-secretary so that others can read it —or hear it read aloud—and experience what he has seen.

St. John receives the heavenly message from an angel and then dictates it to his disciple-secretary so that others can read it —or hear it read aloud—and experience what he has seen.“Blessed is the one who reads aloud the words of this prophecy, and blessed are those who hear it and take to heart what is written in it, because the time is near.” (Apocalypse 1:3)

St. John tells us that whoever reads the words of the Apocalypse is “blessed.” This is the first of seven times a person or a group is pronounced “blessed” in the Apocalypse. These seven beatitudes (Rev. 1:3, 14:13, 16:15, 19:9, 20:6, 22:7, 14) are similar to the Beatitudes announced in the gospels during the Sermon on the Mount.

The term rendered as “blessed” in English is a Greek word that can mean both “happy” and “blessed by God;” it has become common to find English translations of the gospels that render the Beatitudes as “Happy are those who mourn… Happy are those who hunger and thirst after righteousness… Happy are the merciful… Happy are the poor in spirit….” This translation is true on one level: those who live in such a way do find happiness but that idea of “happiness” is probably better thought of as “joy.” “Happy” can sound flip and lighthearted, a fleeting emotion that has no roots or stability. To be “blessed by God” certainly contains the idea of joy but also has an austere edge to it: this way of life is difficult but worthwhile and demands self-sacrifice from those who practice it.

Church Slavonic also uses the word “blessed” as a way to describe those the world deems “foolish, crazy, or insane.” The fools-for-Christ (ex. 1 Cor. 4:10) are called “blessed.” The merciful, the poor in spirit, those who hunger and thirst after righteousness are all crazy. Foolish. Insane. Because living like that will always arouse the animosity of “the world,” the fallen order that opposes God.

In the beginning of the Apocalypse, the “blessed” are those who read aloud the words that St. John has written. Reading aloud is a liturgical act. The text that St. John sends to the churches is to be read aloud during the celebration of the Eucharist just as the letters of the Apostle Paul were read aloud during the celebration of the Eucharist. This introduction of the Apocalypse establishes the liturgical context of the whole book. This “reading aloud”–just as the phrase, “I was in the spirit on the Lord’s Day,” i.e. was attending the celebration of the Eucharist on Sunday–make clear that the Apocalypse is best understood as a pastoral letter and a commentary on the Eucharist itself.

The epistle to the Hebrews is the other “liturgical commentary” in the New Testament; it is interesting to note that the two texts that were most problematic in the establishment of the New Testament canon–the epistle to the Hebrews and the Apocalypse–are the two commentaries on the liturgical practice of the early Church.

The post Blessed is the one who reads appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.