Galen Watson's Blog: The Psalter - Posts Tagged "steampunk"

Let's Party Like it's 1864! - Honest Abe's Imagination Celebration

The Nevada Museum of Art in Reno hosted a steampunk-themed party Saturday, November 1, to celebrate the State’s sesquicentennial anniversary. Nevada became the 36th state on October 31, 1864, just days before Abraham Lincoln’s November 8 presidential re-election. The four story museum was transformed into party central, with bars and sweet and savory hors d’oeuvres on three of its four levels. El Radio Fantastique rocked the ground level with a Halloween- and Steampunk-themed show, featuring genre-defying music that seemed to be a dreamlike, 19th century, modern rock fusion.

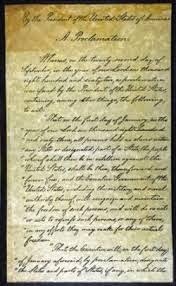

The Nevada Museum of Art in Reno hosted a steampunk-themed party Saturday, November 1, to celebrate the State’s sesquicentennial anniversary. Nevada became the 36th state on October 31, 1864, just days before Abraham Lincoln’s November 8 presidential re-election. The four story museum was transformed into party central, with bars and sweet and savory hors d’oeuvres on three of its four levels. El Radio Fantastique rocked the ground level with a Halloween- and Steampunk-themed show, featuring genre-defying music that seemed to be a dreamlike, 19th century, modern rock fusion.While a party atmosphere reigned throughout most of the museum, the second floor held a solemn calm, in marked contrast to the high-spirited revelry. On exhibition for four days, the original Emancipation Proclamation was on loan from the National Archives. Partiers paused from merrymaking to queue up for a glimpse at one of the most important documents in American history. It’s a rare viewing, since the fragile and faded proclamation can only be shown in very dim light for a mere 48 hours per year. The Nevada Museum of Art has it for 36 of those hours. Also on display for the first time were Civil War muster rolls from the cavalry and infantry stationed at Fort Churchill, as well as period photographs.

The party ended at 11 pm; and band members—led by a high-stepping, Effie Trinket-garbed museum staffer--marched a few blocks to Tavern 1864, with revelers in tow dancing in the street. The band played outside in the chill autumn air while patrons bellied up to the bar. An animated crowd chatted and laughed in steampunk attire. Yet through the cacophony, my eye was drawn to the wall facing me. A photograph of Abraham Lincoln stared back beneath a pleated fan of red, white and blue; and I pondered America’s 16th president: the signer of the fading Emancipation Proclamation I had just witnessed.

Lincoln had long been a vocal opponent of slavery. He proclaimed in the 1850’s that it was “an unqualified evil to the negro, the white man, and the State.” And, his response to his opponent Stephen A. Douglas’ draft of the Kansas-Nebraska Act that allowed settlers to decide whether they would expand slavery was just as pointed: “I cannot but hate it. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself.” Yet, in his first address to Congress in the summer of 1861, Lincoln reassured the assembly that he had “no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with slavery in the States where it exists.” Why the apparent contradiction? The answer lies in the pandemic support for slavery, not just in Southern States, but Border States, and southern sympathizers in the North. Lincoln was compelled to navigate a minefield, if the Union was to be preserved.

It might be hard to imagine today—unless you live in the South--but Lincoln wasn’t a popular candidate in 1860 even in some Northern States, particularly the Midwest. He won his first presidential race with only 40% of the popular vote, although the Electoral College was decisive. Southern States were outraged. Even before he took office, secessionists made clear their intent to leave the Union; and assassination plots were already being hatched. Lincoln was forced to travel to Washington DC in disguise, and placed under a military guard for protection.

For Southern States, Lincoln’s election spelled disaster. They were a mostly agrarian economy--primarily cotton and tobacco--and heavily dependent on slave labor. The slave population had exploded in the South by 1860, and was 57% of the population in South Carolina! Most of the South’s capital was invested in cotton land and slaves, and banks used them as collateral for debt. The mere idea of emancipation was tantamount to financial destruction for the 45,000 planters who owned over half of the slaves, as well as the banks that financed them.

Even Christians in America were bitterly divided. Southern churches justified enslavement, arguing that Abraham had slaves, and the Ten Commandments given by God proclaimed, "Thou shalt not covet…his manservant, nor his maidservant…." The Apostle Paul returned a runaway slave to his owner, and even Jesus never spoke out against slavery. On the other side, Christian abolitionists--the largest part of Lincoln’s Republican constituency--condemned slavery and demanded an end to the vile institution. Pope Gregory XVI condemned the slave trade in a Papal Bull in 1839. Northern Methodists and Quakers had long been in the vanguard to put an end to slavery, and the founder of Methodism, John Wesley, believed “slavery was one of the greatest evils that a Christian should fight.” But Southern Methodists didn’t agree, and the protestant sect divided in 1850. Southern Presbyterians also broke away in their religious support for slavery. Likewise, Baptists in the south defended slavery, and separated to form Southern Baptists

This was the bitter atmosphere in the fragile union of the United States, as newly-elected President Abraham Lincoln stepped to the podium to deliver his first inaugural address. He begged the South for unity as a country, even if they weren't in agreement: "We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies….” Lincoln’s words fell on deaf ears in Southern States. They formed their own Confederate States of America, drafted a constitution, and General Pierre Beauregard opened fire on the Union Army at Fort Sumpter, South Carolina. The Civil War had begun.

It’s often a small thing in the course of human events that goes viral and changes history. A pro-slave lawyer turned Union General, Benjamin Franklin Butler, occupied Fort Monroe in Virginia in May of 1861, when three slaves escaped from their labor constructing Rebel fortifications. Despite the law requiring him to return slaves to their lawful masters, Butler used his legal mind to reason that since their efforts aided the enemy, and since they were property, he declared them “contraband,” and refused. News of Butler’s refusal spread like wildfire, and slaves escaped their oppressors by the thousands for Union lines and protection as “contrabands.” Congress passed a wartime confiscation act that gave slaves who had been forced to aid the Confederate war effort “contraband” status, and forbade army officers from returning them to their masters.

The Union suffered a disturbing string of defeats in the summer of 1862, and the military strategy of emancipation to weaken the South’s war machine grew increasingly persuasive. Congress passed a second confiscation act, giving safe haven to runaway slaves. A militia act allowed freed slaves to serve in the Army. But Lincoln grasped that what began as a military strategy to weaken the South could be much bolder and far-reaching than anyone imagined. He planned to free all slaves in states waging war against the United States; and he would sell the idea as a military necessity. On January 1, 1863 President Lincoln, as Commander in Chief, issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring slaves held in states still in rebellion “then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

The wartime proclamation didn’t apply to border slave states or states controlled by the Union, however. And, Lincoln and the abolitionists in the Republican Party knew his wartime proclamation would have no Constitutional legality at the end of the war. So, Radical Republicans drafted a Constitutional Amendment proclaiming, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude,…shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” President Lincoln made the 13th Amendment his top legislative priority, and it was finally ratified by three quarters of the states and adopted on December 18, 1865.

Tragically, Lincoln didn’t live to see the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment. Two days after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of the South, a jubilant crowd gathered in front of the White House in the misty night air, praising President Lincoln and calling on him to speak. The president stood in the window over the over the main door, pages clutched in one hand. A reporter held a lamp, so he could read his prepared words. His young son, Tad, stood by his side. But it wasn’t the sort of victory lap the assembly wanted. A gaunt, thoughtful Lincoln pleaded for re-construction and reconciliation; and he called for black suffrage, voting rights for African Americans. In the crowd, a popular actor and Confederate spy was so incensed by the very idea that he spat, “That is the last speech he will make.” Three days later, John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theater—just a year after the proposed 13th Amendment passed the senate.

I gazed at the costumed revelers crowding Tavern 1864, many of whom were garbed in Civil War uniforms or antebellum gowns. One young man was meticulously dressed as a humble private in the service of the Union Army. I imagined him posted in General Butler’s tense lines, protecting Fort Monroe as he intercepted three accidental “contrabands” that started a veritable wave of slave defiance. Then, the photograph of America’s 16th president--creator and signer of the Emancipation Proclamation--captured my gaze once again. I raised my glass in an outstretched hand to the tall, slender, bearded man who helped expiate a loathsome stain from our beloved and United States: “well done Mr. President, from a grateful nation.”

P.S. The Southern Baptist Convention adopted a resolution apologizing—at long last—for its racist origins, support for slavery, segregation, and white supremacist theology in 1995. They resolved to “to repudiate historic acts of evil, such as slavery, from which we continue to reap a bitter harvest.”

P.P.S The Methodist Church apologized for “centuries of racism”—at long last—in 2000. Bishop William Boyd Grove confessed that “Racism has lived like a malignancy in the bone marrow of this church for years…. It is high time to say we’re sorry.”

P.P.P.S. The Episcopal Church apologized for its support of slavery and institutionalized racism—at long last—in 2006. They confessed that “The Episcopal Church lent the institution of slavery its support and justification based on Scripture, and after slavery was formally abolished, the Episcopal Church continued for at least a century to support de jure and de facto segregation and discrimination,…”

Published on November 08, 2014 09:17

•

Tags:

abolition, abraham-lincoln, civil-war, contraband, emancipation-proclamation, episcopalians, nevada-day, nevada-museum-of-art, reno, slavery, southern-baptists-methodists, steampunk, thirteenth-amendment