S.R. Piccoli's Blog, page 9

July 13, 2017

Along the River Sile

I must confess that I didn't know about this before… I've just come across a very beautiful video about Treviso—the town where I live—and its river Sile (among the longest resurgence rivers in Europe). Subtitled in English and narrated by Red Canzian, a popular Italian musician in a band named The Pooh, the video is titled “Sile, oasi d’acque e di sapori” (Sile, oasis of waters and tastes). Hope you'll enjoy it!

PS: Check out some of the following links to learn more about the river Sile:

Park of the River SileTreviso–Mestre. From the River Sile to the LagoonAlong the River Sile in TrevisoAncient trades on the banks of the SileAlong the Sile River by BikeCOPYRIGHT NOTICE:

All original content of this blog [Wind Rose Hotel] is subject to

Creative Commons license (by-nc-sa)

PS: Check out some of the following links to learn more about the river Sile:

Park of the River SileTreviso–Mestre. From the River Sile to the LagoonAlong the River Sile in TrevisoAncient trades on the banks of the SileAlong the Sile River by BikeCOPYRIGHT NOTICE:

All original content of this blog [Wind Rose Hotel] is subject to

Creative Commons license (by-nc-sa)

Published on July 13, 2017 01:03

June 3, 2017

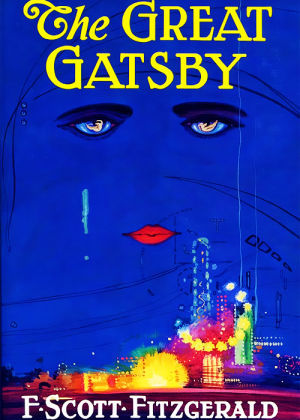

Are We All Jay Gatsby?

Most of the big shore places were closed now and there were hardly any lights except the shadowy, moving glow of a ferryboat across the Sound. And as the moon rose higher the inessential houses began to melt away until gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors' eyes—a fresh, green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby's house, had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.

Most of the big shore places were closed now and there were hardly any lights except the shadowy, moving glow of a ferryboat across the Sound. And as the moon rose higher the inessential houses began to melt away until gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors' eyes—a fresh, green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby's house, had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder. And as I sat there brooding on the old, unknown world, I thought of Gatsby's wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy's dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that's no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther. . . . And one fine morning——

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

~ Francis Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby.

Francis Scott FitzgeraldI’ve always loved the ending lines of The Great Gatsby, not just the last sentence, which is the one that is quoted the most, but, say, the last four paragraphs, which I tend to regard as, essentially, more of a poem than a piece of prose—while the ending line is, even on a formal level, very close to poetry, due to both a wave-like alliteration with the letter b, as we read the monosyllabic words “beat,” “boats,” “borne,” and “back,” and to being written almost in iambics (as we well know, iambic is a meter, often used in Shakespeare’s writing, that alternates stressed and unstressed syllables to create a da-DUM, da-DUM, da-DUM, da-DUM pattern).

Francis Scott FitzgeraldI’ve always loved the ending lines of The Great Gatsby, not just the last sentence, which is the one that is quoted the most, but, say, the last four paragraphs, which I tend to regard as, essentially, more of a poem than a piece of prose—while the ending line is, even on a formal level, very close to poetry, due to both a wave-like alliteration with the letter b, as we read the monosyllabic words “beat,” “boats,” “borne,” and “back,” and to being written almost in iambics (as we well know, iambic is a meter, often used in Shakespeare’s writing, that alternates stressed and unstressed syllables to create a da-DUM, da-DUM, da-DUM, da-DUM pattern). But apart from the lyricism of these lines, I must confess that the more I get older, the more I understand how much truth there is in them. To a certain extent, they connect Gatsby to all of us. After all, by ending the way it does, the novel makes Gatsby explicitly represent all humans, “boats against the current” whose fate is already sealed since the very beginning of the story: being “borne back ceaselessly into the past,” or alternatively being frustrated in our dreams to restore a past that cannot return. One way or another, we are all losers. You can’t escape it. That’s also why Gatsby, Myrtle, and George Wilson die, and why no one come to Gatsby’s funeral. It all feels kind of empty and pointless, especially after all the effort that Gatsby put into trying to recreate his and Daisy’s love … Well, that empty feeling is basically the whole point.

At the same time we must remember that this is one side of the coin. The other side is that while all human beings appear to be condemned to an inevitable defeat, there’s a chance that our defeat might be only apparent. Take the most inevitable of defeats, the one against time. Whoever you are and whatever you do, you are subject to the inexorable law of time, and yet, in a way, time is not, by necessity, the last word, in just the way in which, for us Christians, death is not a disaster, but a new beginning—Death is swallowed up in victory. O death, where is thy victory? O death, where is thy sting? (1 Corinthians 15:54-55). In other words, death is not the last word for those who are believers in the resurrected Christ.

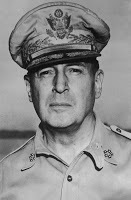

General Douglas MacArthurAs for time, if our body can’t help submitting to the laws of nature, the same cannot be said for our soul. Whether you want it to or not, the body gets old—sure, we may be able to slow down the process, but it cannot be reversed. On the contrary, the spirit may continue to be young, because, well, “youth is not a time of life; it is a state of mind; it is not a matter of rosy cheeks, red lips and supple knees; it is a matter of the will, a quality of the imagination, a vigor of the emotions; it is the freshness of the deep springs of life.” Or at least that’s the way Samuel Ullman put the whole thing in his poem “Youth.” But I couldn’t figure out a more eloquent and effective way of putting it, and general Douglas MacArthur—who hung a framed copy of a version of the poem on the wall of his office in Tokyo, when he became Supreme Allied Commander in Japan—probably couldn’t either.

General Douglas MacArthurAs for time, if our body can’t help submitting to the laws of nature, the same cannot be said for our soul. Whether you want it to or not, the body gets old—sure, we may be able to slow down the process, but it cannot be reversed. On the contrary, the spirit may continue to be young, because, well, “youth is not a time of life; it is a state of mind; it is not a matter of rosy cheeks, red lips and supple knees; it is a matter of the will, a quality of the imagination, a vigor of the emotions; it is the freshness of the deep springs of life.” Or at least that’s the way Samuel Ullman put the whole thing in his poem “Youth.” But I couldn’t figure out a more eloquent and effective way of putting it, and general Douglas MacArthur—who hung a framed copy of a version of the poem on the wall of his office in Tokyo, when he became Supreme Allied Commander in Japan—probably couldn’t either. “Youth,” the poet continues, “means a temperamental predominance of courage over timidity, of the appetite for adventure over the love of ease. This often exists in a man of 60 more than a boy of 20. Nobody grows old merely by a number of years. We grow old by deserting our ideals.” Yes, courage, adventure, ideals—isn’t that what being young at heart and in spirit is all about? The rest of the poem is a glorious crescendo of joy and confidence..

Years may wrinkle the skin, but to give up enthusiasm wrinkles the soul. Worry, fear, self-distrust bows the heart and turns the spring back to dust.

Whether 60 or 16, there is in every human being's heart the lure of wonder, the unfailing childlike appetite of what's next and the joy of the game of living. In the center of your heart and my heart there is a wireless station: so long as it receives messages of beauty, hope, cheer, courage and power from men and from the Infinite, so long are you young.

When the aerials are down, and your spirit is covered with snows of cynicism and the ice of pessimism, then you are grown old, even at 20, but as long as your aerials are up, to catch waves of optimism, there is hope you may die young at 80.

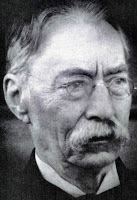

Samuel UllmanWhat a great, simple lesson for all of us! Here, among these lines, is where F. Scott Fitzgerald’s melancholic and pessimistic view of life is bound to founder and, even more so, is proved to be wrong. And mind you, without calling into question metaphysical and/or religious beliefs, which are personal and subjective. If the inexorable law of time can be eluded, then there is still hope, nothing essential is lost. Or, to put it very simply, as Billy Graham says, “When wealth is lost, nothing is lost; when health is lost, something is lost; when character is lost, all is lost.” It’s up to you to live life to the fullest, to follow your dreams and make the world a better place for you and everyone. COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

Samuel UllmanWhat a great, simple lesson for all of us! Here, among these lines, is where F. Scott Fitzgerald’s melancholic and pessimistic view of life is bound to founder and, even more so, is proved to be wrong. And mind you, without calling into question metaphysical and/or religious beliefs, which are personal and subjective. If the inexorable law of time can be eluded, then there is still hope, nothing essential is lost. Or, to put it very simply, as Billy Graham says, “When wealth is lost, nothing is lost; when health is lost, something is lost; when character is lost, all is lost.” It’s up to you to live life to the fullest, to follow your dreams and make the world a better place for you and everyone. COPYRIGHT NOTICE:All original content of this blog [Wind Rose Hotel] is subject to

Creative Commons license (by-nc-sa)

Published on June 03, 2017 10:32

May 20, 2017

Hypocrisy

I was chatting with a friend of mine the other day about the topicality of Dante’s Divine Comedy. What we both agreed upon was that the first of the three canticles of the poem, Inferno, is by far the most topical one. Nowhere else is there a more perfect description of human nature, its weakness, passions, miseries and sordidnesses. And nowhere else is there a deeper sense of justice in the face of sin and evil. We also agreed that the most topic among all the sins mentioned in the Comedy is hypocrisy.

Detail of miniature of Dante and Virgil encountering three couples of hypocrites, clad in gilt hoods, while on the ground are stretched Caiaphas and Annas, in illustration of Canto XXIII. (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450

Detail of miniature of Dante and Virgil encountering three couples of hypocrites, clad in gilt hoods, while on the ground are stretched Caiaphas and Annas, in illustration of Canto XXIII. (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450

London, British Library, Yates Thompson, 36 fol-42b Hypocrites

And now, down there, we found a painted people,

And now, down there, we found a painted people,

slow-motioned: step by step, they walked their round

in tears, and seeming wasted by fatigue.

All were wearing cloaks with hoods pulled low

covering the eyes (the style was much the same

as those the Benedictine wear at Cluny),

dazzling, gilded cloaks outside, but inside

they were lined with lead, so heavy that the capes

King Frederick used, compared to these, were straw.

O cloak of everlasting weariness!

We turned again, as usual, to the left

and moved with them, those souls lost in their mourning;

but with their weight tired-out race of shades

paced on so slowly that we found ourselves in

new company with every step we took;

(Inferno, Canto XXIII)

In fact, if we look at today’s world—particularly in the fields of politics, media, religion, and academia—you can’t help seeing that we’re surrounded by hypocrites—for the record, the word hypocrisy comes from the Greek ὑυπόκρισις (hypokrisis), which means “jealous,” “play-acting,” “acting out,” “coward” or “dissembling.”

We live in a “do as I say, not as I do” culture that is slowly breeding an entirely new generation of Pharisees, blinder than those who killed Jesus, where double-standards ARE the standard and double thinking is routine. What applies to Obama, Clinton, Podesta, etc. doesn’t apply to Trump and his men (and women), and vice versa. The same exact behavior is bad when someone you don’t agree with does it, but great when someone you do agree with does. We preach dialogue but practice monologue. We preach brotherhood but practice Cainhood. Our eleventh silent commandment is, “Preach sugar and honey, practice venom and vinegar.” This whole thing would be a farce if it were not a tragedy—not a small one, but a major tragedy in the rapidly darkening fortunes of the Western world.

Back to the main story, as everybody knows, in Dante’s Inferno there is a level for each sin committed, i.e. different circles, with the depth of the circle (and placement within that circle) symbolic of the amount of punishment to be inflicted. As the eighth of nine circles, Malebolge is one of the worst places in hell to be—and the only circle that has a proper name. Malebolge means evil ditches, or evil bolgias, and this Circle is dedicated to the sins of fraud, and each ditch is for a specific kind of fraud.

Dante and his guide, Virgil, make their way into Malebolge by riding on the back of the monster Geryon, the personification of fraud, who possesses the face of an honest man “good of cheer,” but the tail of a scorpion. In Bolgia Six lie the hypocrites. They are forced to wear heavy lead robes as they walk around the circumference of their circle. The robes are bright and golden on the outside, and resemble a monk’s cowl similar to the elegant ones worn by the Benedictine monks at Cluny, but are lined with heavy lead, symbolically representing hypocrisy. Just as Jesus compares hypocritical scribes and Pharisees to tombs that appear clean and beautiful on the outside while containing bones of the dead (Matthew 23:27).

By the way, who knows whether Dante knew that the specific weight of gold is much higher than that of lead? ;-) Be it as it may, I wish poetry could cure our moral diseases! The Divine Comedy would be our salvation! And instead we cannot but recall Eliot’s famous response when I.A. Richards took up Matthew Arnold’s cry, “it may be poetry will save us”: “it is like saying that wall-paper will save us when the walls have crumbled.” (T. S. Eliot, “Literature, Science, and Dogma,” Dial, 82, 1927: 243)

Interesting stuff, isn’t it? Maybe next time we’ll talk about the ninth circle: Betrayers...

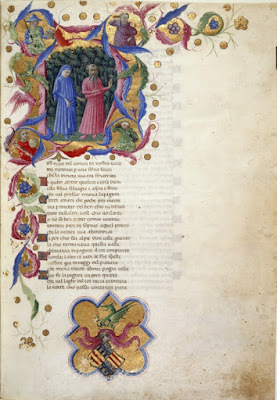

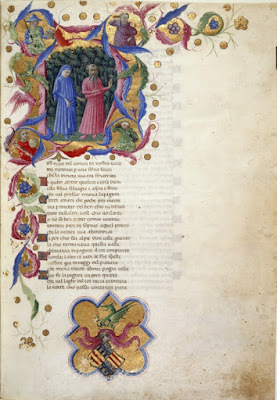

Historiated initial ‘N’(el) of Dante and Virgil in a dark wood, with four half-length figures representing Justice, Power, Peace, and Temperance, with the arms of Alfonso V below, at the beginning of the Divina Comedia, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 1r

Historiated initial ‘N’(el) of Dante and Virgil in a dark wood, with four half-length figures representing Justice, Power, Peace, and Temperance, with the arms of Alfonso V below, at the beginning of the Divina Comedia, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 1r

COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

All original content of this blog [Wind Rose Hotel] is subject to

Creative Commons license (by-nc-sa)

Detail of miniature of Dante and Virgil encountering three couples of hypocrites, clad in gilt hoods, while on the ground are stretched Caiaphas and Annas, in illustration of Canto XXIII. (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450

Detail of miniature of Dante and Virgil encountering three couples of hypocrites, clad in gilt hoods, while on the ground are stretched Caiaphas and Annas, in illustration of Canto XXIII. (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450London, British Library, Yates Thompson, 36 fol-42b Hypocrites

And now, down there, we found a painted people,

And now, down there, we found a painted people, slow-motioned: step by step, they walked their round

in tears, and seeming wasted by fatigue.

All were wearing cloaks with hoods pulled low

covering the eyes (the style was much the same

as those the Benedictine wear at Cluny),

dazzling, gilded cloaks outside, but inside

they were lined with lead, so heavy that the capes

King Frederick used, compared to these, were straw.

O cloak of everlasting weariness!

We turned again, as usual, to the left

and moved with them, those souls lost in their mourning;

but with their weight tired-out race of shades

paced on so slowly that we found ourselves in

new company with every step we took;

(Inferno, Canto XXIII)

In fact, if we look at today’s world—particularly in the fields of politics, media, religion, and academia—you can’t help seeing that we’re surrounded by hypocrites—for the record, the word hypocrisy comes from the Greek ὑυπόκρισις (hypokrisis), which means “jealous,” “play-acting,” “acting out,” “coward” or “dissembling.”

We live in a “do as I say, not as I do” culture that is slowly breeding an entirely new generation of Pharisees, blinder than those who killed Jesus, where double-standards ARE the standard and double thinking is routine. What applies to Obama, Clinton, Podesta, etc. doesn’t apply to Trump and his men (and women), and vice versa. The same exact behavior is bad when someone you don’t agree with does it, but great when someone you do agree with does. We preach dialogue but practice monologue. We preach brotherhood but practice Cainhood. Our eleventh silent commandment is, “Preach sugar and honey, practice venom and vinegar.” This whole thing would be a farce if it were not a tragedy—not a small one, but a major tragedy in the rapidly darkening fortunes of the Western world.

Back to the main story, as everybody knows, in Dante’s Inferno there is a level for each sin committed, i.e. different circles, with the depth of the circle (and placement within that circle) symbolic of the amount of punishment to be inflicted. As the eighth of nine circles, Malebolge is one of the worst places in hell to be—and the only circle that has a proper name. Malebolge means evil ditches, or evil bolgias, and this Circle is dedicated to the sins of fraud, and each ditch is for a specific kind of fraud.

Dante and his guide, Virgil, make their way into Malebolge by riding on the back of the monster Geryon, the personification of fraud, who possesses the face of an honest man “good of cheer,” but the tail of a scorpion. In Bolgia Six lie the hypocrites. They are forced to wear heavy lead robes as they walk around the circumference of their circle. The robes are bright and golden on the outside, and resemble a monk’s cowl similar to the elegant ones worn by the Benedictine monks at Cluny, but are lined with heavy lead, symbolically representing hypocrisy. Just as Jesus compares hypocritical scribes and Pharisees to tombs that appear clean and beautiful on the outside while containing bones of the dead (Matthew 23:27).

By the way, who knows whether Dante knew that the specific weight of gold is much higher than that of lead? ;-) Be it as it may, I wish poetry could cure our moral diseases! The Divine Comedy would be our salvation! And instead we cannot but recall Eliot’s famous response when I.A. Richards took up Matthew Arnold’s cry, “it may be poetry will save us”: “it is like saying that wall-paper will save us when the walls have crumbled.” (T. S. Eliot, “Literature, Science, and Dogma,” Dial, 82, 1927: 243)

Interesting stuff, isn’t it? Maybe next time we’ll talk about the ninth circle: Betrayers...

Historiated initial ‘N’(el) of Dante and Virgil in a dark wood, with four half-length figures representing Justice, Power, Peace, and Temperance, with the arms of Alfonso V below, at the beginning of the Divina Comedia, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 1r

Historiated initial ‘N’(el) of Dante and Virgil in a dark wood, with four half-length figures representing Justice, Power, Peace, and Temperance, with the arms of Alfonso V below, at the beginning of the Divina Comedia, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 1rCOPYRIGHT NOTICE:

All original content of this blog [Wind Rose Hotel] is subject to

Creative Commons license (by-nc-sa)

Published on May 20, 2017 15:36

January 30, 2017

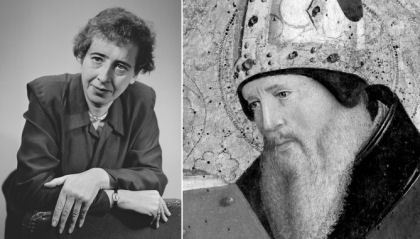

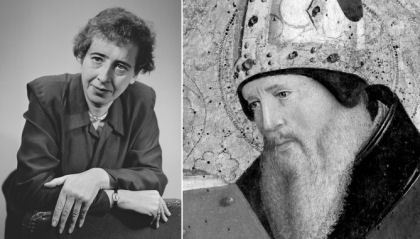

Hannah Arendt, St. Augustine and the Problem of Evil

Friday, January 27th was International Holocaust Remembrance Day, a time for people to both honor those killed under the Nazi regime and prevent future genocide. As every year at this time, I wanted to post something on the matter, but had a particularly busy day and didn’t have much time to jot down some ideas. I took advantage of the weekend and what follows is the result.

It is indeed my opinion now that evil is never ‘radical’, that it is only extreme, and that it possesses neither depth nor any demonic dimension. It can overgrow and lay waste the whole world precisely because it spreads like a fungus on the surface. It is ‘thought-defying’ […] because thought tries to reach some depth, to go to roots, and the moment it concerns itself with evil, it is frustrated because there is nothing. That is its ‘banality’. Only the good has depth and can be radical.

It is indeed my opinion now that evil is never ‘radical’, that it is only extreme, and that it possesses neither depth nor any demonic dimension. It can overgrow and lay waste the whole world precisely because it spreads like a fungus on the surface. It is ‘thought-defying’ […] because thought tries to reach some depth, to go to roots, and the moment it concerns itself with evil, it is frustrated because there is nothing. That is its ‘banality’. Only the good has depth and can be radical.

~ Hannah Arendt, Letter to Gershom (Gerhard) Scholem, July 24, 1963.

When in 1961 Nazi SS Lieutenant Colonel Otto Adolf Eichmann, one of the major figures in the organization of the Holocaust, was taken captive in Argentina by agents of the Israeli government and brought to trial in Jerusalem, the German-born Jewish-American writer and philosopher Hannah Arendt saw an opportunity to confront the “realm of human affairs and human deeds . . . directly.” And so it was that she decided to undertake a reporter’s job and started to report on the trial for The New Yorker magazine. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, published in 1963, was the result of Hannah Arendt’s coverage of the trial, and one of the most controversial books of the 20th century.

Covering the trial Arendt used the phrase “the banality of evil,” a definition that has since become a classic. By the way, it wasn’t Arendt who first coined the phrase. In fact, in her correspondence with her mentor Karl Jaspers about the Nuremberg trials, the great German psychiatrist and philosopher highlighted a risk involved in the use by Arendt of the Kantian term radical evil to refer to the horrors of the Holocaust (her precise words, however, were that totalitarian terror had “the appearance of radical evil”): in his view it might endow perpetrators with a “streak of satanic greatness” and mystify their deeds in “myth and legend.” To escape this danger Jaspers emphasized the “prosaic triviality” of the perpetrators and coined the phrase “the banality of evil” to make his point. In reply Arendt agreed with this observation.

The distinction between radical evil and banality of evil is developed in detail in the above quoted

Scholem, also known as Gerhard Scholem, a German-born Israeli Jewish philosopher and historian, accused her of not having a love for the Jewish people, of using a “heartless, frequently almost sneering and malicious tone.” “Your account,” he wrote, “ceases to be objective and acquires overtones of malice.” Explaining why the Jewish critics at least were so upset by the book, Scholem wrote: “In the Jewish tradition there is a concept, hard to define and yet concrete enough, which we know as Ahabath Israel: ‘Love of the Jewish people....’ In you, dear Hannah ... I find little trace of this.” “I have little sympathy,” he added, “with that tone—well expressed by the English word ‘flippancy’—which you employed so often in the course of your book. To the matter of which you speak it is unimaginably inappropriate.” Arendt’s reply was unapologetic:

Arendt’s reply also shows that, although she had suffered herself and witnessed the suffering of other Jews, she was not inclined to let these experiences overcome her ability to critically analyze the facts. Actually, she brought an independent and probing mind to her coverage of Eichmann trial. And that’s perhaps one of the most interesting aspects of her approach to the whole thing.

But let’s go back to the point—the banality of evil. What did she really mean by that? What she certainly did not mean was that evil had become ordinary, or that Eichmann had not committed an exceptional and, to some extent, unprecedented crime. What she actually meant was that, as it is explained in the above quoted excerpt from her letter to Gerhard Scholem, there is nothing in evil for thought to latch onto. The banality of evil is its own lack of depth. What is banal are not the murderous deeds per se, but the lack of depth in the evildoer Arendt faced in Jerusalem, and by consequence in the horrors he inflicted on his victims and on humanity at large.

It is especially interesting now to note that St. Augustine’s idea that evil is not something fully real but only something dependent on that which is more real—his account of the original nature of evil in the contexts of ontology, society and divine providence—in fact provides the basis for Arendt’s analysis of the banality of evil in the individual, the social, and the political spheres. As David Grumett put it in an article published in 2000, “[a] small amount of attention has been given to Arendt’s work on Augustine, though surprisingly none has focused on the concept of evil.” Arendt’s concept of the origin and nature of evil, he wrote, “is usually attributed to her personal experience of totalitarianism and later coverage of the trial of the Final Solution bureaucrat Adolf Eichmann. This however fails to give a full account. Its intellectual roots are rather to be found in her doctoral dissertation on Augustine, published in 1929.” ("Arendt, Augustine and Evil," in The Heythrop Journal, Volume 41, Issue 2, April 2000)

Especially in his early works, Augustine identifies evil negatively. Take the Confessions (7. 12. 18):

Or Eighty-three Different Questions (6 “On Evil”):

But Augustine’s best known and most quoted definitions of evil are the ones he gave in Enchiridion: On Faith, Hope, and Love, Chapters 3 and 4:

In the light of the similarities between Augustine’s and Arendt’s concepts of evil, according to Philip Reiff, we are allowed to speak of “Arendt’s theology of politics.” (The Theology of Politics: Reflections on Totalitarianism as The Burden of our Time," Journal of Religion 32, 2, 1952, p. 119) As David Grumett puts it, though Arendt is not a specifically Christian thinker, “she in places laments the decline in acceptance of aspects of a Christian world-view.” “She does not, for instance, hold divine grace or the mediation of Christ as components of her thought, as Augustine does,” Grumett explains, “[s]he rather brings Augustine’s world-view, explored in her early study of Augustine, to bear on the modern and contemporary human condition.”

To conclude, in David Grumett’s words, Arendt’s and Augustine’s “recognition of the existence of great evil in the world and of the facticity of human existence in the world” is far from pessimistic. “On the contrary, it is precisely by being content to live in the world that a human may do his or her part to safeguard its reality and protect it from evil.” COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

All original content of this blog [Wind Rose Hotel] is subject to

Creative Commons license (by-nc-sa)

It is indeed my opinion now that evil is never ‘radical’, that it is only extreme, and that it possesses neither depth nor any demonic dimension. It can overgrow and lay waste the whole world precisely because it spreads like a fungus on the surface. It is ‘thought-defying’ […] because thought tries to reach some depth, to go to roots, and the moment it concerns itself with evil, it is frustrated because there is nothing. That is its ‘banality’. Only the good has depth and can be radical.

It is indeed my opinion now that evil is never ‘radical’, that it is only extreme, and that it possesses neither depth nor any demonic dimension. It can overgrow and lay waste the whole world precisely because it spreads like a fungus on the surface. It is ‘thought-defying’ […] because thought tries to reach some depth, to go to roots, and the moment it concerns itself with evil, it is frustrated because there is nothing. That is its ‘banality’. Only the good has depth and can be radical. ~ Hannah Arendt, Letter to Gershom (Gerhard) Scholem, July 24, 1963.

When in 1961 Nazi SS Lieutenant Colonel Otto Adolf Eichmann, one of the major figures in the organization of the Holocaust, was taken captive in Argentina by agents of the Israeli government and brought to trial in Jerusalem, the German-born Jewish-American writer and philosopher Hannah Arendt saw an opportunity to confront the “realm of human affairs and human deeds . . . directly.” And so it was that she decided to undertake a reporter’s job and started to report on the trial for The New Yorker magazine. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, published in 1963, was the result of Hannah Arendt’s coverage of the trial, and one of the most controversial books of the 20th century.

Covering the trial Arendt used the phrase “the banality of evil,” a definition that has since become a classic. By the way, it wasn’t Arendt who first coined the phrase. In fact, in her correspondence with her mentor Karl Jaspers about the Nuremberg trials, the great German psychiatrist and philosopher highlighted a risk involved in the use by Arendt of the Kantian term radical evil to refer to the horrors of the Holocaust (her precise words, however, were that totalitarian terror had “the appearance of radical evil”): in his view it might endow perpetrators with a “streak of satanic greatness” and mystify their deeds in “myth and legend.” To escape this danger Jaspers emphasized the “prosaic triviality” of the perpetrators and coined the phrase “the banality of evil” to make his point. In reply Arendt agreed with this observation.

The distinction between radical evil and banality of evil is developed in detail in the above quoted

Scholem, also known as Gerhard Scholem, a German-born Israeli Jewish philosopher and historian, accused her of not having a love for the Jewish people, of using a “heartless, frequently almost sneering and malicious tone.” “Your account,” he wrote, “ceases to be objective and acquires overtones of malice.” Explaining why the Jewish critics at least were so upset by the book, Scholem wrote: “In the Jewish tradition there is a concept, hard to define and yet concrete enough, which we know as Ahabath Israel: ‘Love of the Jewish people....’ In you, dear Hannah ... I find little trace of this.” “I have little sympathy,” he added, “with that tone—well expressed by the English word ‘flippancy’—which you employed so often in the course of your book. To the matter of which you speak it is unimaginably inappropriate.” Arendt’s reply was unapologetic:

You are quite right – I am not moved by any ‘love’ of this sort, and for two reasons: I have never in my life ‘loved’ any people or collective – neither the German people, nor the French, nor the American, nor the working class or anything of that sort. I indeed ‘love’ only my friends and the only kind of love I know of and believe in is the love of persons. Secondly, this ‘love of the Jews’ would appear to me, since I am myself Jewish, as something rather suspect…. I do not ‘love’ the Jews, nor do I ‘believe’ in them; I merely belong to them as a matter of course, beyond dispute or argument.

Arendt’s reply also shows that, although she had suffered herself and witnessed the suffering of other Jews, she was not inclined to let these experiences overcome her ability to critically analyze the facts. Actually, she brought an independent and probing mind to her coverage of Eichmann trial. And that’s perhaps one of the most interesting aspects of her approach to the whole thing.

But let’s go back to the point—the banality of evil. What did she really mean by that? What she certainly did not mean was that evil had become ordinary, or that Eichmann had not committed an exceptional and, to some extent, unprecedented crime. What she actually meant was that, as it is explained in the above quoted excerpt from her letter to Gerhard Scholem, there is nothing in evil for thought to latch onto. The banality of evil is its own lack of depth. What is banal are not the murderous deeds per se, but the lack of depth in the evildoer Arendt faced in Jerusalem, and by consequence in the horrors he inflicted on his victims and on humanity at large.

It is especially interesting now to note that St. Augustine’s idea that evil is not something fully real but only something dependent on that which is more real—his account of the original nature of evil in the contexts of ontology, society and divine providence—in fact provides the basis for Arendt’s analysis of the banality of evil in the individual, the social, and the political spheres. As David Grumett put it in an article published in 2000, “[a] small amount of attention has been given to Arendt’s work on Augustine, though surprisingly none has focused on the concept of evil.” Arendt’s concept of the origin and nature of evil, he wrote, “is usually attributed to her personal experience of totalitarianism and later coverage of the trial of the Final Solution bureaucrat Adolf Eichmann. This however fails to give a full account. Its intellectual roots are rather to be found in her doctoral dissertation on Augustine, published in 1929.” ("Arendt, Augustine and Evil," in The Heythrop Journal, Volume 41, Issue 2, April 2000)

Especially in his early works, Augustine identifies evil negatively. Take the Confessions (7. 12. 18):

And it was made clear unto me that those things are good which yet are corrupted, which, neither were they supremely good, nor unless they were good, could be corrupted; because if supremely good, they were incorruptible, and if not good at all, there was nothing in them to be corrupted. For corruption harms, but, less it could diminish goodness, it could not harm. Either, then, corruption harms not, which cannot be; or, what is most certain, all which is corrupted is deprived of good. But if they be deprived of all good, they will cease to be. For if they be, and cannot be at all corrupted, they will become better, because they shall remain incorruptibly. And what more monstrous than to assert that those things which have lost all their goodness are made better? Therefore, if they shall be deprived of all good, they shall no longer be. So long, therefore, as they are, they are good; therefore whatsoever is, is good. That evil, then, which I sought whence it was, is not any substance; for were it a substance, it would be good. For either it would be an incorruptible substance, and so a chief good, or a corruptible substance, which unless it were good it could not be corrupted. I perceived, therefore, and it was made clear to me, that Thou made all things good, nor is there any substance at all that was not made by You; and because all that You have made are not equal, therefore all things are; because individually they are good, and altogether very good, because our God made all things very good.

Or Eighty-three Different Questions (6 “On Evil”):

Everything which is, is either corporeal or incorporeal. The corporeal is embraced by sensible form, and the incorporeal , by intelligible form. Accordingly everything which exists is not without some form. But where there is form there necessarily is measure, and measure is something good. Absolute evil, therefore, has no measure, for it lacks all good whatever. It thus does not exist, for it is embraced by no form, and the whole meaning of evil is derived from the privation of form.

But Augustine’s best known and most quoted definitions of evil are the ones he gave in Enchiridion: On Faith, Hope, and Love, Chapters 3 and 4:

And in the universe, even that which is called evil, when it is regulated and put in its own place, only enhances our admiration of the good; for we enjoy and value the good more when we compare it with the evil. For the Almighty God, who, as even the heathen acknowledge, has supreme power over all things, being Himself supremely good, would never permit the existence of anything evil among His works, if He were not so omnipotent and good that He can bring good even out of evil. For what is that which we call evil but the absence of good? In the bodies of animals, disease and wounds mean nothing but the absence of health; for when a cure is effected, that does not mean that the evils which were present—namely, the diseases and wounds—go away from the body and dwell elsewhere: they altogether cease to exist; for the wound or disease is not a substance, but a defect in the fleshly substance,—the flesh itself being a substance, and therefore something good, of which those evils—that is, privations of the good which we call health—are accidents. Just in the same way, what are called vices in the soul are nothing but privations of natural good. And when they are cured, they are not transferred elsewhere: when they cease to exist in the healthy soul, they cannot exist anywhere else. [Emphasis added]

[…]

From this it follows that there is nothing to be called evil if there is nothing good. A good that wholly lacks an evil aspect is entirely good. Where there is some evil in a thing, its good is defective or defectible. Thus there can be no evil where there is no good. This leads us to a surprising conclusion: that, since every being, in so far as it is a being, is good, if we then say that a defective thing is bad, it would seem to mean that we are saying that what is evil is good, that only what is good is ever evil and that there is no evil apart from something good. This is because every actual entity is good. Nothing evil exists in itself, but only as an evil aspect of some actual entity. Therefore, there can be nothing evil except something good.

In the light of the similarities between Augustine’s and Arendt’s concepts of evil, according to Philip Reiff, we are allowed to speak of “Arendt’s theology of politics.” (The Theology of Politics: Reflections on Totalitarianism as The Burden of our Time," Journal of Religion 32, 2, 1952, p. 119) As David Grumett puts it, though Arendt is not a specifically Christian thinker, “she in places laments the decline in acceptance of aspects of a Christian world-view.” “She does not, for instance, hold divine grace or the mediation of Christ as components of her thought, as Augustine does,” Grumett explains, “[s]he rather brings Augustine’s world-view, explored in her early study of Augustine, to bear on the modern and contemporary human condition.”

Perhaps it was from Augustine that Arendt learnt the importance for political thought of properly recognizing human sinfulness and worldly facticity if it is to confront the problem of the origin of evil. This is what makes her concept of the origin of evil and her existentialism valuable and believable.

To conclude, in David Grumett’s words, Arendt’s and Augustine’s “recognition of the existence of great evil in the world and of the facticity of human existence in the world” is far from pessimistic. “On the contrary, it is precisely by being content to live in the world that a human may do his or her part to safeguard its reality and protect it from evil.” COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

All original content of this blog [Wind Rose Hotel] is subject to

Creative Commons license (by-nc-sa)

Published on January 30, 2017 07:30

January 24, 2017

A Chance Encounter

This morning I had a chance encounter with an old priest—an 80-something-year-old man—whom I had known when I was in my twenties. At the time, he was a teacher at the Seminary of the Diocese of Treviso, but he also served as vice-parish priest in my then parish church in Treviso. I remember him as a very cultured, good-natured and amiable person. That’s also why I was really pleased to meet him after all this time. But the main reason why I was so happy about the chance encounter was that all these years I have always remembered something he told me once about how to read publicly the Word of God with effectiveness. Even then I was appalled by the sloppiness of so many lectors (and priests), so I asked him for some guidance on that matter. And he gave me what I asked for, and it was actually a great lesson. “The Word of God,” he told me, “is to be neither ‘recited,’ nor merely ‘read.’ It is to be ‘proclaimed.’” Proclaimed, with all that this implies (which is a lot of things, as you can easily figure out).

This morning I had a chance encounter with an old priest—an 80-something-year-old man—whom I had known when I was in my twenties. At the time, he was a teacher at the Seminary of the Diocese of Treviso, but he also served as vice-parish priest in my then parish church in Treviso. I remember him as a very cultured, good-natured and amiable person. That’s also why I was really pleased to meet him after all this time. But the main reason why I was so happy about the chance encounter was that all these years I have always remembered something he told me once about how to read publicly the Word of God with effectiveness. Even then I was appalled by the sloppiness of so many lectors (and priests), so I asked him for some guidance on that matter. And he gave me what I asked for, and it was actually a great lesson. “The Word of God,” he told me, “is to be neither ‘recited,’ nor merely ‘read.’ It is to be ‘proclaimed.’” Proclaimed, with all that this implies (which is a lot of things, as you can easily figure out). I told don Andrea (for such is his name) about this memory of mine, and he seemed to be pleased with that.

Sometimes it’s incredible how a simple sentence can become a sort of personal brand, to the extent that, in the mind of another person, a man perfectly coincides with a sentence he uttered decades ago. That’s also why we should be always very careful about what we say.. You never can tell what might become “your brand” in someone else’s imagination and memories! COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

All original content of this blog [Wind Rose Hotel] is subject to

Creative Commons license (by-nc-sa)

Published on January 24, 2017 14:48

January 22, 2017

Facebook Friends Lists

Recently a friend wrote in her timeline, “Evidently I've been talking to myself since Christmas. All my FB posts were privacy set to ‘Only me.’” That did automatically ring a bell for me, because something similar happened to me as well in the past—I don’t want to be too specific on that… Actually, it was frustrating and comic at the same time.

Nevertheless, such events have the power to bring attention to the wide range of opportunities Facebook offers us : you can decide—either once and for all or on a case-by-case basis—who (and where and when) can see your posts: Public, Friends, Friends of Friends, Only me, Custom (lists of friends, etc). Most users have their Facebook privacy set to Friends only or Friends of friends. As a rule I personally prefer the “Public” option, but from time to time and for specific purposes I may make exceptions—most of the times for reasons of respect and elegance.

However, and apart from specific preferences, what matters most is to make the best out of one’s Facebook account. For this purpose here are some suggestions and tips.

How to Artfully Cull Your Facebook Friends ListHow To Manage Your Facebook Relationships With Friend ListsHow to Create a Custom Facebook Friend ListFacebook Friends List Can Help Control Your News FeedHow to Hide Your Facebook Friends List

COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

All original content of this blog [Wind Rose Hotel] is subject to

Creative Commons license (by-nc-sa)

Published on January 22, 2017 17:39

November 14, 2016

An Open Letter to My Social Media Friends

Dear Social Media Friends,

A few notes on my birthday, which occurred just yesterday. First, let me say a huge thank you to all of you that have been kind enough to stop by at my Facebook page and other social media, and leave your birthday wishes! All included—Facebook (timeline and chat), Twitter, LinkedIn, etc.—I received as many as several hundreds of birthday wishes from almost all over the world, especially from the United States of America, the UK, and the European Union. Let me just let you know that I appreciated each and every one of them and that I’m both grateful to you for your friendship and happy for the wonderful opportunities the new information and communication technologies offer to us. Especially for people of my generation, the state of the art of the ICT—which I consider a true blessing and a gift from God—is a continuous source of wonder and excitement.

A few notes on my birthday, which occurred just yesterday. First, let me say a huge thank you to all of you that have been kind enough to stop by at my Facebook page and other social media, and leave your birthday wishes! All included—Facebook (timeline and chat), Twitter, LinkedIn, etc.—I received as many as several hundreds of birthday wishes from almost all over the world, especially from the United States of America, the UK, and the European Union. Let me just let you know that I appreciated each and every one of them and that I’m both grateful to you for your friendship and happy for the wonderful opportunities the new information and communication technologies offer to us. Especially for people of my generation, the state of the art of the ICT—which I consider a true blessing and a gift from God—is a continuous source of wonder and excitement.However, I must say that what amazes me most about yesterday, is that my presence in the social media, and on the Internet in general, is not of the common kind, my most frequent posts being about political, philosophical and cultural issues: a bit boring for a lot of people, I’m afraid. At the same time I cannot but congratulate myself for choosing the right people to be friends with!

Of course, as always happens, birthdays are a great, if not unique, opportunity to unfriend and be unfriended... this time they were half a dozen, in addition to those—at least another half a dozen people—who have unfriended me in the last few weeks. But I don’t complain about that: I knew that supporting Donald Trump would have some consequences. Well, in a sense, I am grateful to them: I have never unfriended anyone on Facebook for political reasons, and never will, that’s contrary to my beliefs, but perhaps they were right in doing so. In other words, as we say in Italy, they pulled my chestnuts out of the fire.

Also, ever since I started supporting Trump things have cooled down with some of my best friends. No surprise at all, but then again every choice has a cost. I’m sorry about that, but I did what I had to do, and I’m proud about that. Do what is right, not what is easy. That’s integrity, I presume, or at least as much integrity as possible.

By the way, I want to point out one thing about the recent presidential election: Hillary was absolutely right when, in the immediate aftermath of her defeat, she said, “I want you to remember this: our campaign was never about one person or even one election…” That’s perhaps exactly the reason why so many people in America and around the world (including me) have spent their time and energies in fighting against her, her supporters, and what they stand for—the “values” they share, and the vision they hold—with all means at their disposition. The lesson is: whenever and wherever it’s needed, we’ll be there.

Published on November 14, 2016 08:55

November 5, 2016

The Craziest Sermon I Have Ever Heard

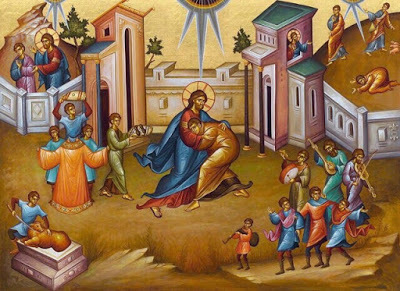

The Prodigal Son (Orthodox Icon)

The Prodigal Son (Orthodox Icon)Yesterday afternoon I attended the funeral of a neighbor—a 80-something-year-old man, and a very kind and good person. I didn’t know the priest who celebrated the Funeral Mass, the only thing I know about him is what he said about himself in his homily, namely, that he is 74 and that in the long-ago he had lived in that parish, that he was a lifelong friend of the man and his family, and that he was familiar with most of those attending the ceremony.

It was one of the craziest, most unpredictable and memorable homilies I had ever heard. He talked in spurts—as many basically shy but very intelligent people often do—with sudden and vivid flashes of lightning, so to speak, rather than complete sentences, as if he was trying to say something pretty profound and at the same time a bit too difficult to put in words. So he danced around the issue the whole time without saying anything explicitly “religious.” He talked about “backing home”—his own’s and his friend’s. He talked about friendship, work ethic, dedication to the family, but the true meaning of the whole speech was, “hey, your friend, husband, father, etc., isn’t really dead, because he simply can’t die..” He was uttering the most touching and profound Christian truths without ever appearing to do so. A homily full of faith and hope without ever pronouncing the words “faith” and “hope,” as if there were no need to explicitly mention what everyone already intimately knows. Because hey, you folks know how things really are.., don’t you?

A poet, a humble but great man, a street philosopher and a man of God. I regret not having the opportunity to listen to his homilies every Sunday, but thank God for having had the chance to listen to him yesterday. COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

All original content of this blog [Wind Rose Hotel] is subject to

Creative Commons license (by-nc-sa)

Published on November 05, 2016 11:07

October 30, 2016

About Poking on Facebook

Times are tough, I know, but let’s talk about something a bit more cheerful than my normal rants, let’s talk about Facebook, the most popular of all the social media platforms. There’s a question I’ve been meaning to ask someone in the know—you’ve just received a Facebook poke, and the first thing that comes to your mind is, “What is this, and what does it mean?”

Times are tough, I know, but let’s talk about something a bit more cheerful than my normal rants, let’s talk about Facebook, the most popular of all the social media platforms. There’s a question I’ve been meaning to ask someone in the know—you’ve just received a Facebook poke, and the first thing that comes to your mind is, “What is this, and what does it mean?” Of course you may have an idea about the likely meaning of this specific event, in the light of the literal meaning of the word “poke”—“to push your finger or something thin or pointed into or at someone or something” (Merriam-Webster). But to dispel any doubts, an investigation is needed. Thus I googled for answers.. and found hundreds and hundreds of questions and answers.

First of all, what I learned from my search is that a very beloved feature—a button called “Poke”—was enabled since the day Facebook launched in 2004. The button didn’t come with any explanation or rules. Mark Zuckerberg, then 23, said he just wanted to make something with no real purpose..

Secondly, I learned that the Facebook poke was once considered to be a creepy flirting tool, but now it has evolved into something very different. In fact, the most common answer is that a poke on Facebook is more or less the equivalent of tapping someone on the shoulder to say a quick “hello.”

Another popular interpretation is that it is a way to let other people know that you are thinking of them without going through all the trouble of sending private messages or posting publicly to their online wall. A very simple and kind way of saying things like “Remember that I’m here if you’re in troubles, if you feel worn out, or if you need anything,” or just “I miss you,” or “I want you to know that I care about you and what you're going through.” Interesting, isn’t it? Well, of course you might say, “Wouldn’t it be better to just pick up the phone and call her/him?” To which one could reply, “Yes, but sometimes (not to say always) life is more complicated than we would like!” A very strong counter argument, in my view.

Thus, Facebook makes it easier to express our inner feelings and thoughts. Which is not a small thing, above all in these harsh and troubled times.

That being said, however, it is clear that you shouldn’t poke people you don’t really know, especially because you can’t always predict the consequences, if you understand what I mean.., and certainly you shouldn’t take a poke too seriously—remember that 99 times out of 100 a poke is meant to be just for fun.

In any case, and to conclude, I’d say that the main result of my investigations on this subject may be stated as follows: there are no rules for this kind of thing—instinct, common sense, and good taste should guide us here. My viewpoint, for what it’s worth, can perhaps best be summed up by the cartoon below.. ;)

Keep up the good poking!

COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

All original content of this blog [Wind Rose Hotel] is subject to

Creative Commons license (by-nc-sa)

Published on October 30, 2016 07:51

October 24, 2016

Feeling Compelled to Vote for Donald Trump

Have you noticed that the Mainstream Media—both in the U.S. and in Europe—is distrusted by growing numbers of people? Have you noticed that the cronyism between the Establishment and the MSM has become too blatant to ignore? It has been evident for years that the U.S. Establishment and their MSM cheerleaders have been manipulating a rigged political system to impose their self-serving politics. That’s why so many people—even among those who, until recently, were anti-Trump—feel compelled to vote for him. Here is an example. “Bias has always been a factor in journalism,” writes Derek Hunter, a DC based writer, radio host and political strategist, and “it’s nearly impossible to remove. Humans have their thoughts, and keeping them out of your work is difficult. But 2016 saw the remaining veneer of credibility, thin as it was, stripped away and set on fire.” “More than anything,” he continues,

I can’t sit idly by and allow these perpetrators of fraud to celebrate and leak tears of joy like they did when they helped elect Barack Obama in 2008. I have to know I weighed in not only in writing but in the voting booth.

The media needs to be destroyed. And although voting for Trump won’t do it, it’s something. Essentially, I am voting for Trump because of the people who don’t want me to, and I believe I must register my disgust with Hillary Clinton. […]

The Wikileaks emails have exposed an arrogant cabal of misery profiteers who hold everyone, even their fellow travelers deemed not pure enough, in contempt. These bigots who’ve made their fortune from government service should be kept as far away from the levers of power as the car keys should be kept from anyone named Kennedy on a Friday night. My one vote against it will not be enough, but it’s all I can do and I have to do all I can do.

The Project Veritas videos, he notes, “exposed a corrupt political machine journalists would have been proud to expose in the past.” The Wikileaks emails “pulled back the curtain on why that didn’t happen —journalists are in on it. I can’t pretend otherwise, and I have no choice but to oppose it.”

This, however, isn’t a call to arms for Never Trumpers to follow suit, says Hunter, “this is my choice, what I must do. Each person has to come to this decision on their own terms.” Yet, he observes,

A simple protest vote for a third party or a write-in of my favorite comic book character might feel good for a moment. It might even give me a sense of moral superiority that lasts until her first executive order damaging something I hold dear—or her first Supreme Court nominee. But the sting that will follow will far outlive that temporary satisfaction.

I oppose much of what Donald Trump has said, but I oppose everything Hillary Clinton has done and wants to do. And what someone says, no matter how objectionable, is less important than what someone does, especially when it’s so objectionable. A personal moral victory won’t suffice when the stakes are so high. As such, I am compelled to vote against Hillary by voting for the only candidate with any chance whatsoever of beating her—Donald Trump.

COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

All original content of this blog [Wind Rose Hotel] is subject to

Creative Commons license (by-nc-sa)

Published on October 24, 2016 17:29