Barbara Ross's Blog

December 12, 2024

Saying Good-bye to the Wickeds

The moment we’ve all been talking about for a week, and that I’ve been anticipating since May, has finally come. This is my last post as a member of the Wicked Authors. Partings are difficult and this one particularly so.

I will miss my fellow authors and readers. Some of the relationships created here are among the most meaningful in my life. I have appreciated every one of you—your contributions, posts, and comments, and your general good cheer. What a lovely place this has been—and no doubt will continue to be.

As I have assured my fellow Wickeds repeatedly, I am #notdying. I’ll still be around on some social media platforms and can be reached via my website. I extend that invitation to all of you. The Wickeds have said I can visit as a guest author if I should ever be published again. So maybe I’ll see you here. Not shutting the door. More of a “so long” than a “farewell.”

Take care of yourselves. Have great holidays. And thank you, thank you, thank you, from the bottom of my heart.

@font-face<br> {font-family:"Cambria Math";<br> panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4;<br> mso-font-charset:0;<br> mso-generic-font-family:roman;<br> mso-font-pitch:variable;<br> mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}@font-face<br> {font-family:Aptos;<br> panose-1:2 11 0 4 2 2 2 2 2 4;<br> mso-font-charset:0;<br> mso-generic-font-family:swiss;<br> mso-font-pitch:variable;<br> mso-font-signature:536871559 3 0 0 415 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal<br> {mso-style-unhide:no;<br> mso-style-qformat:yes;<br> mso-style-parent:"";<br> margin:0in;<br> mso-pagination:widow-orphan;<br> font-size:12.0pt;<br> font-family:"Aptos",sans-serif;<br> mso-ascii-font-family:Aptos;<br> mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;<br> mso-fareast-font-family:Aptos;<br> mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin;<br> mso-hansi-font-family:Aptos;<br> mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;<br> mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman";<br> mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;<br> mso-font-kerning:1.0pt;<br> mso-ligatures:standardcontextual;}.MsoChpDefault<br> {mso-style-type:export-only;<br> mso-default-props:yes;<br> font-family:"Aptos",sans-serif;<br> mso-ascii-font-family:Aptos;<br> mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;<br> mso-fareast-font-family:Aptos;<br> mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin;<br> mso-hansi-font-family:Aptos;<br> mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;<br> mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman";<br> mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}div.WordSection1<br> {page:WordSection1;}

November 4, 2024

The Business of Writing

by Barb, in Key West at last!

Welcome to the sixth and last of my posts about what I’ve learned in my fourteen years as a published author. This post is about the Business of Writing.

I’ve spent most of those years as a traditionally published author and I’m writing from that experience, so view what I have to say from that perspective.

And by the way, I’m astonished that after twenty years we’re somehow seeing instances of traditional versus indie bomb-throwing. It reminds me of the working mom versus stay-at-home mom tempests my younger self was subjected to. These conversations always seem to come from a defensive crouch. Do what’s right for you. Make the most of the choices you have. Let others make the best choice for themselves. Live and let live.

For years, when I’ve talked about the publishing business, I’ve used air quotes. The publishing “business,’ because if you come to it with experience in other industries, publishing will be unrecognizable to you as a business.

[After this, I wrote several paragraphs about the ways the publishing business is insane and the reasons why I think that is so, but I’ve scrapped them. That’s not the point.]

Here’s the point. Author, you are on your own. Whether you are traditionally or independently published, it is down to you. You are running your business and nobody cares about it as much as you do.

Will agents and editors give you professional advice and help you grow as a writer? Yes, they will. But they are inherently conflicted.

Your agent works for you. But unless he or she is a very bad agent, he is doing a lot more business with your publisher than he is doing with you. I’m not suggesting agents are unethical. I am merely saying their bread is buttered on both sides of these transactions and you had best bear that in mind.

Your editor and publisher work in a shrinking industry under ever worse price and margin pressure. This makes them reflexively conservative. If you are even modestly successful, they will want you to do more of what you have been doing. Because doing something else is risky and businesses that are surviving under threat don’t take risks.

If you are lucky, your agent and your publisher are your partners in the development of your business. Your junior partners.

You come into this business as a supplicant. “Please, please like my work.” “Please please publish my work.” So it’s easy to see how, having come to the business as supplicants, writers have trouble immediately shifting into the role of partner. Senior partner. But remember way back in the first post in this series when I said Voice is confidence. Having a fulfilling career, the one you want, is all about confidence, too.

It’s hard to have confidence when you’re dealing with an agents and editors who have way more experience than you, and who have the power to say no. But if you are going to spend your time writing fiction, for goodness sake, write what you want. Have the career that you want. Will you fail? Probably and often. But trying and failing will leave you happier and more satisfied than toiling away at something that is difficult, that you don’t enjoy, with compensation that is far from guaranteed. If you going to indulge yourself by writing, indulge yourself by doing what you want.

Readers: Do you have questions about the publishing business? Barb has nothing to lose at this point, so she’s likely to give you a candid answer.

October 7, 2024

Writing Advice: The Good, the Bad, and the Indifferent

by Barb, still in Maine where it has been the most glorious fall

Welcome to my fifth post about what I’ve learned in fourteen years of being a published author and a lifetime of writing. The first four posts are about Voice, Emotion, Narrative Distance, and Dialog Tags. In this post, I’m going to pass along the bits of advice I (and almost every other fiction writer) have received along the way along with my (current) judgement about how useful the advice was. As I side note, I did examine several pieces of advice related to dialog tags in my previous post, so I’m leaving that topic out here.

“Thirty years ago my older brother, who was ten years old at the time, was trying to get a report written on birds that he’d had three months to write, which was due the next day. We were out at our family cabin in Bolinas, and he was at the kitchen table close to tears, surrounded by binder paper and pencils and unopened books about birds, immobilized by the hugeness of the task ahead. Then my father sat down beside him put his arm around my brother’s shoulder, and said, “Bird by bird, buddy. Just take it bird by bird.”

When people ask me what books I recommend on writing, I always answer Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, and Stephen King’s On Writing : A Memoir Of The Craft. The quote above is one of the central tenets of Bird by Bird, that you need to tackle overwhelming writing tasks by breaking them down into manageable chunks. It took a couple of runs at this and a good friend reinforcing it before I incorporated the discipline into my writing and my entire life. But once I learned not to think in terms of writing an entire book, but in terms of writing 1000 or 1200 words or a scene or a chapter at a sitting, I was a happier and more successful person and writer.

That being said, one of my personal eccentricities is that I have never, ever typed, “The end.” I know there will always be more drafts, and copy-edits, and page-proofs, and publicity, and reviews, comments, and e-mails. Your relationship to your book never ends.

“Perfectionism is the voice of the oppressor, the enemy of the people. It will keep you cramped and insane your whole life, and it is the main obstacle between you and a shitty first draft.”

Two other central tenets of Lamott’s amazing work are the idea of “shitty first drafts” and the enemy to creativity that is perfectionism. Most of us who begin writing have been reading heavily for years, some of it the great works of literature. Thinking that what flows from our fingers has to be that good from the get-go is one of the great barriers to writing. Understanding that you can get it done and you can (and will) fix it later is a key to finishing and to success.

“I began to stalk around his living room, like a trial lawyer making her case to the jury, explaining various aspects of the book, some of which, in my desire not too appear to obvious, I had forgotten to put down at all.”

This is a much less often cited quote from Bird by Bird. In fact, it’s not Googlable, but it is terribly meaningful to me. I was, and remain, a sparse writer, especially in first drafts. But in the beginning I also suffered from the unconscious belief that what the character had to be thinking or feeling must be so obvious that I didn’t need to put it on the page. I was young, and now that I’m older, I have a better appreciation that what is glaringly obvious to me is not obvious to everyone. Not because they are not smart but because their lives and experiences are different from my own. As a friend of mine says, “When my mother says ‘No one would ever do such a thing,’ what she means is ‘No one who lives within eight square blocks of me would ever do such a thing.'” Our contexts are unique.

Also, as I said in my post on emotion, in fiction, particularly crime fiction, readers need to see how point of view characters are reacting to and processing information both intellectually and emotionally, in order to know those characters and to root for them. I come back to the quote above all the time to remind myself not to leave out the things that seem obvious to me.

“Pow! Two unrelated ideas, adolescent cruelty and telekinesis came together, and I had an idea.”

Since I cited On Writing as my other north star, I wanted to include advice from it as well. It’s not so much an advice book. Like Bird by Bird, it’s part autobiography and it also contains advice about how to be in the world as a writer. Not that many (or any) of us can be in the world like Steven King, but I found it helpful nonetheless. The quote above relates to Carrie, and how two unrelated ideas can come together to create a premise. I’ve since heard Tom Perrotta say this too–that it takes two concepts to make an interesting idea. This advice has been very helpful to me, especially when I’ve had an idea too thin to be a book, or, minimalist that I am, I’ve been tempted to reject that second idea as something that will muddy the book instead of make the book.

“Start with your character in motion.”

I’m not sure who said this to me. I think it might have been in a class I took with Hallie Ephron, whose excellent book is Writing and Selling Your Mystery Novel Revised and Expanded Edition: The Complete Guide to Mystery, Suspense, and Crime. This advice has been very helpful too me. Sometimes my character starts in literal motion, going out a door, driving up a driveway. But the more important thing to remember is that stories are about change, things that happen outside the norm.

On the other hand I feel free to ignore advice like “Never start with the weather.” Or “Never start with a phone call.” The weather thing might be good advice for beginners, especially those who are tempted to “set the scene.” But in more adept hands starting with the weather is fine. The phone call thing I’ve never gotten. What can set events in motion more than a a phone call in the middle of the night?

“If you’re going to tell a lie, tell it fast, tell it straight, don’t justify, don’t explain.”

This advice comes from my friend and fellow writing group member for 20 years, Mark Ammons. What he means is that if you need the reader to buy something, dithering around and shoring it up with all sorts of explanations, only calls attention to it, which makes the reader suspicious of your motives. If you say it quick the reader may move on without questioning it.

“You can put the Statue of Liberty in New Orleans if you can convince the reader.”

This piece of advice was given to me by fellow Wicked Sherry Harris, who was paraphrasing John Dufresne, whose amazing book is The Lie That Tells a Truth: A Guide to Writing Fiction. For me, what this means is, when a reader says, “I didn’t find it believable,” what they are actually saying is, “The writer didn’t sell it to me.” Convincing readers of improbable, unlikely, and unbelievable things is what writers do everyday. But the world-building and the character development have to be there to make it believable.

This piece of advice might seem to contradict the one above–don’t justify or explain. But to me the two go together. Justifying or explaining when an event happens or a character makes a decision in a book will undermine it. But if the foundation is already there, you don’t need to do that in the moment. Mark also says, “You get one gimme per story,” meaning that you can ask the reader to swallow one improbable thing, no more. But that’s meant to be one moment in a story and it had better not be something like, “He looked up from his porch in New Orleans and saw the Statue of Liberty,” unless you’ve laid the foundation, or you want to shock the reader into reading further.

“You know more about your story than you think you do.”

Speaking of Wickeds, this is not so much something Jessie Crockett says when running her Polka Dot Plotting coaching sessions or workshops, but something that she models. Using Jessie’s methodology, which she walks you through, you discover that you do, indeed, have all sorts of assumptions about your story embedded in your subconscious dying to come out. Some will be good, some bad. Some will make it to the final draft, some will not. But they are there and once you’ve had the courage to articulate them, they will be much easier to write.

“Writing a novel is like driving a car at night. You can see only as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way. You don’t have to see where you’re going, you don’t have to see your destination or everything you will pass along the way. You just have to see two or three feet ahead of you.”

This piece of advice from E.L. Doctorow kept me going on many a day. It was especially helpful when I was a pure pantser, but even in the later stages of my career when I did some plotting (see Polka Dot Plotting above) I could never come up with all the scenes, and though my list of scenes might have included the what and the why, they never included the how. So I treasure this advice.

“When people tell you something’s wrong or doesn’t work for them, they are almost always right. When they tell you exactly what they think is wrong and how to fix it, they are almost always wrong.”

This piece of advice from Neil Gaiman always makes me laugh because it takes me back to my 20 happy years in my writing group. It is always more fun and so much easier to write someone else’s book. And while there are times and places for brainstorming, (exclusively when the writer asks for it) the fun other writers in a group have making suggestions of the “you know what you should do,” type is not anything you should pay attention to. Let them have their fun. Keep your own counsel.

“Show don’t tell.”

An old chestnut and good advice for the beginner but of limited value. As Julia Glass, the brilliant author of Three Junes said in a seminar I took with her, “Sometimes you just tell it.” I always think of showing and telling like a camera in a movie, zooming in and pulling out. Pulling out for the establishing shots, viewed from a distance, the details fuzzy or obscured. The B roll. It’s a pacing thing, mostly.

“Describe the fast things slow and the slow things fast.”

This bit of advice is attributed to Lee Child. I think it is a human-being thing as much as a writing thing but very good writing advice that relates to the above. Say you have an hour long commute. The first time you drove it, to the job interview, you were white-knuckled and noticed every sign, building, and vehicle along the way. By a month on the job, you often arrive in the parking lot wondering how you got there. That commute will be a single phrase for your character, “By the time Jack arrived at the office…” But my husband and I were in a car accident a year and a half ago. For insurance reasons, we asked for the read-out from the car’s computer. I was astonished to see the car had careened with my husband fighting for control for a total of nine seconds. I remember every beat as the passenger, not knowing what was happening, screaming, seeing the plastic picnic table explode as we plowed into it and being thankful even then there was no one sitting there. My husband, trying to control the car, making decisions, hearing me screaming and pleading, undoubtedly remembers it differently but in the same slow-motion, goes-on-forever mode.

“No head-hopping.”

This is common advice everyone will give you when you’re new. What it means is that when telling the story from one character’s point of view you shouldn’t suddenly jump into another’s point of view revealing things the original character couldn’t know or feel. The most common place to change point of view characters is at a scene break.

I’m not as doctrinaire about this as some. I’ve enjoyed many books by authors who change point of view mid-scene or who hide the point of view in a new scene for a couple of paragraphs to keep you guessing. As long as the reader is not unintentionally confused I think both of these techniques are okay.

What’s not okay is some of the tortured constructions that result from the over-interpretation of this guideline. We look at other people all the time and think, “Joe is sad.” As sentient beings we are constantly drawing conclusions about other people’s status. We don’t think “Joe appears to be sad.” That is stupid. Cut that out.

I am always amused by new writers who greet advice like this simple guideline about heading hopping with responses like, “But in the fourth section of The Sound and the Fury, William Faulkner…” To which I always reply, “If you think your skills and talent are at the same level as Faulkner, go for it.” Some day I will meet someone brimming with self-confidence who will take my up and this and be right about their abilities. I look forward to having that happen.

“If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired. Otherwise don’t put it there.”

This guideline, recorded in letters by Anton Checkov, is an old saw but deservedly so. To me it means that every detail must serve the story in some way. Nothing is random or has no purpose. It also helps me think about payoff for the reader and character. Often when writing you don’t know why something is there or someone is in a scene or the story keeps returning to the same place. Then in a later draft, when you know what you are doing, you discover the reason. Your subconscious knew all along.

Readers and Writers: What bit of advice have I forgotten, one that means something to you? I am sure there are many. Are any of these new to you?

September 9, 2024

Tag, You’re It!

by Barb, just back from a wonderful week on Prince Edward Island

I’m here with the fourth post in my series about what I’ve learned while writing my 15 published mystery novels, 6 novellas, and dozen or so short stories. (You can see the previous posts here, and here, and here.)

So much writing advice and instruction is aimed at beginners. Learning opportunities get harder to find as you get more advanced. Yes, if you’re lucky, you’re getting feedback from your agent and/or editor, but that’s usually specific to a manuscript. Julie Hennrikus and I have often bemoaned the lack of a support group specifically for the Middies–mid-career, mid-list, middle-aged. (Ha, ha. Well, not necessarily that last one.)

What I’ve tried to do with this series is capture things it took me a while to catch onto. But, of course, writing doesn’t work like that. What is easy or obvious to one person has to be learned by dint of hard work by another. And vice versus. Also, I’ve found I’ve had to learn things in layers. Something that made no sense when I first heard it will click into place when I’ve had more experience.

I’m doing my best to pass on hard-earned wisdom in this series but your mileage may vary.

One of the things you have to do along the way is discard a lot of advice that was good, or at least well-meant, when you were a beginner. I mean by that lessons that were intended to steer you away from the most obvious pitfalls. “Show, don’t tell,” is a good example. Er, yes, but not always.

Another example is about dialogue tags. The first level of advice about dialogue tags that you get is that you should never add an adverb, as in, “Thanks for the fish,” Joe said, gratefully. Yes, that is bad, redundant, and does have the whiff of Dick and Jane about it. But it’s hard for me to imagine that anyone who has read a lot of contemporary fiction would even think to do that.

The next layer of prohibition is that you should use no tag but “said.” No whispered, shouted, asked, wondered, queried, explained, complained, etc. The theory here is two-fold. One, you should be able to get anything you need beyond said from the context. The reader should be able to tell from the quote if someone is screaming or musing. Two, said is the least disruptive, most invisible of dialogue tags. It all but disappears in the reader’s mind and therefore doesn’t interrupt the flow of the characters’ conversation.

My reaction to these first two layers of prohibition is often something like, “English is a big, beautiful language and I can use any part of it I want!” (Which is patently untrue since I spent most of my career writing cozy mysteries and there were words I couldn’t use. George Carlin listed most of them in 1972.) I do understand this advice, though my characters do occasionally ask, respond, whisper, or stage-whisper and so on.

The third level of prohibition is that you shouldn’t use dialogue tags at all. Every character, this piece of advice goes, should have such a distinct voice that the reader will know who is saying what.

My reaction to this is three-fold. 1) Great when it works, but as anyone who has ever had to read backwards through three pages of dialogue to figure out which character is speaking will tell you, having to do that definitely takes you out of the story. 2) While I buy that I need to understand who my minor characters are and why they’re saying what they’re saying, short of giving each minor character some kind of accent or speech impediment, endowing each one some instantly recognizable speech pattern seems unduly burdensome to both reader and writer. And 3) if I had known dialogue tags were undesirable, I wouldn’t have had a team of two police detectives and an amateur sleuth because that combination results a in a lot of three-way and four-way conversations.

Seriously, what I have found is that dialogue tags are often unnecessary, but not because of distinct ways of speaking, or thoughts that could only be expressed by one specific character (though that’s good if you can achieve it). Instead I find the best way to eliminate dialogue tags is via bits of business that anchor the conversation in time and space, add to character development, and slow down and open up the conversation, allowing it (and the reader) to breathe.

Example (with tags):

“Where are you going?” Jack asked.

“Dunno.” I answered.

“Really?” Jack said. He was skeptical.

“Let’s go to the spring house,” I responded.

Example (but did you really need them?):

“Where are you going?” Jack drew alongside me, his boots scuffing in the dry dirt of the trail.

“Dunno.” I’d fled the house knowing only that I had to get I had to get away from the oppressive atmosphere that followed the discover of Esme’s body. I’d been walking with no destination in mind.

Jack raised an eyebrow. He didn’t believe me.

“Let’s go to the spring house.” I realized the moment I spoke the words that I’d unwittingly invited him along.

As I’ve said in previous posts in this series these are things I’ve learned along the way, so you’ll see me adding unnecessary tags all the way through to the last book. There is one “said” in Torn Asunder that I justified keeping in “for rhythm” through a dozen revisions. Then, finally, when I read the book in print, I realized (at long last and way too late) the tag was unneeded. (Smacks forehead. Doh!)

Readers and writers: How do you feel about dialogue tags? Do you adhere to the rule of “said” only or none at all? Do you notice dialogue tags? All the time, or only when they’re done badly?

August 5, 2024

A view from a distance

by Barb, writing in Maine, where the weather has been so beautiful this summer it’s almost hard to believe

Here we are for the third in my series of posts about what I’ve learned after putting in my 10,000 hours writing mysteries.

The first in the series, The Voice, is here.The second, It’s the emotion, stupid, is here.

This time I’m writing about narrative distance.

From time to time, I’m asked to review manuscripts by pre-published writers. Often this is as a part of a conference in which people can pay for manuscript reviews, or in association with a group, like the Sisters in Crime Guppies. (Great UnPublished)

One of the two most common issues I see is narrative distance. Too often I see the insertion of “distancing” words. Like this:

I wondered what he was doing down by the dock by himself. My mind reeled at the idea he might be guilty. I believed him to be a good man. His reputation alone placed him above suspicion. I’d known him a long time. I’d thought he was my friend.

Nothing wrong with that, right? We’ve all read books like that, which is why those words unspool so easily from our minds when we’re writing. But most of the books we’ve read that use this style of narration are older. Modern commercial fiction is most often written in a very close point of view.

Words like “wondered,” “believed,” “my mind,” “idea,” “might,” and “thought” place distance between the point of view character and the narrative. And between the narrative and the reader. You probably don’t use those words when you’re talking to yourself in your head.

Try this:

Jack was alone by the dock. Did he kill Esme? No. He was a good man with a solid reputation. More than that, he was my friend.

When I coach writers to remove all those distancing words, what I am really saying is– remove the distance. Try to get as deep inside the character as you can. Crime fiction requires readers to understand what the POV character, particularly the protagonist, is observing, how they’re processing the information they’re getting, and how they feel about it. The best way to do this is for the narration to come from the inside, looking out. Not to come from somewhere above, looking down.

This works in the third person as well.

He walked along, muttering, watching his step on the rocky path. He thought about Esme. It was hard to grasp that she was truly dead. Like all life partners he’d imagined her death before, what it would be like to go on without her. Somehow it hadn’t prepared him for the reality.

Try this:

His boot slid on the steep, rocky path. He sucked air over his teeth, his arms pinwheeling. For a moment, until he regained his footing, his body was as unsettled as his mind. “Esme is dead. Esme is dead. Esme is dead.” It was unreal, illusive. In his head but not in his bones. Not in his heart. The times he’d imagined his life without her flooded back, closing his throat with guilt and shame. It hadn’t been like this. Not at all.

Am I giving you a rule? “Narration must be in very close POV.” No. As you’ll find out in future posts, I hate it when one writer tells others how they must write. In the examples above you can probably think of lots of places the narrative might have landed in between the two extremes, or beyond them. You might even want to play with distance, closer for a protagonist, farther for another POV character.

Here is my advice: Think about distance. Be aware as you write. If something seems wrong, if beta readers or your writing group aren’t responding as you’d hoped, if agents are saying, “I’m just not in love with the main character,” check the distance. Maybe you’re too far away.

Readers: We have such educated readers. You know what point of view characters are, and the difference between first person and third person narration. But do you ever think about narrative distance? Or is it one of those things that is most successful if you don’t notice it? Writers, do you think about narrative distance?

July 8, 2024

It’s the emotion, stupid

by Barb, heading out with the grandkids (and some of their parents) to Boothbay Harbor this week

Here we are for the second in my series of posts about what I’ve learned after putting in my 10,000 hours writing mysteries. The first post in the series, about Voice, is here.

As I said in my introduction to the series, “One caveat: Since these are things I’ve learned along the way, you will find as the posts go on that I have violated or neglected every one of them in my work. Don’t bother looking for examples because you will definitely find them.” That is particularly true of this month’s post because it is the lesson I learned last.

I’ve written before about how I started my career at Information Mapping, a company that offers a proprietary methodology for analyzing, organizing, and presenting complex information. I worked there for a dozen very formative years from my late twenties to my early forties. The Information Mapping methodology forms the bedrock of my intellectual approach to everything.

There’s a whole lot more to it but the methodology starts with two questions:

What do you want readers to do? And,What do they need to know in order to do it?What you want the reader to do can be as simple as putting part A into slot B or as consequential as making a decision that will affect your company for years to come. But you always start with what you want the reader to do and what they need to know in order to do it.

For a long time that way of looking at writing confounded me in terms of creating fiction. What did I want the reader to do? Turn the page, I suppose is one answer, but not a very actionable by itself. I decided my old discipline didn’t apply to my new work and I discarded it.

But then, as I said, late in the game I realized the paradigm was this:

What do I want readers to feel? AndWhat do they need to know in order to feel it?Once you see this, you realize emotion is the lens through which to view the whole project. What we want is for readers to feel. The books we remember are the ones that make us feel. The books we press on our friends, saying, “You have to read this!” are the ones that resonated in our emotions.

In the crime fiction world we work on the worry/anxiety/fear/dread emotional axis a great deal. As crime writers, we talk about creating suspense all the time. But we also want people to love, or hate, or be puzzled by, or feel empathy for, or to cheer on our characters. We want readers to long to visit our settings and shed a tear at our weddings, and at our funerals. We want them to care. They will care because they have been moved.

Often in panels and interviews, writers are asked if there’s a reader they picture when they write. It just happened in the panel Liz, Edith, and I were on at the Kensington CozyCon in May. Often the question comes in a marketing context–do we have a target demographic? I’ve never found this idea the slightest bit useful and I doubt most other writers do. I always answered this in terms of thinking of a reader giving me their precious time and not wanting to waste it–which is the beginning of an answer but not all the way there.

Now I realize writers should not be thinking of a reader, or a group of readers, but of readers writ large. What do I want the reader to feel right now? And what they need to know, either in the moment, or before we got here, in order to feel it?

When we choose one word over another, when we paint a picture or invoke one of the five senses, what do we want the reader to feel? A slippery piece of seaweed between the toes evokes a different emotion than a slimy rope of seaweed entwined around an ankle. A night so dark you can’t see your companion is different than gazing at his profile in the moonlight. These scenes are clear to us as we envision and create them, but thinking in terms of how we want our readers to feel, and what they need to know in order to feel it, it tells us what and how much to put on the page.

Novel writers work alone. We don’t have directors or actors to interpret, to help the audience find the emotion. This is both the best and the worst part about writing books. But we do have partners. When readers read about our specific wedding between two specific characters, in a specific place, they bring with them every wedding they have ever attended and how they felt in those moments. Then the story belongs to them. Our job is to get them there.

Writers: Do you think about the emotion you are evoking in the readers as you create or edit? Readers, do you agree that the books that stay with you are the ones that touch you emotionally?

June 10, 2024

The Voice

by Barb, in Massachusetts, babysitting for grandchildren

I turned in the last manuscript for the Maine Clambake Mysteries a year ago. Since then I haven’t felt retired. There were still cycles of copy-editing and page proofs to get through, and two releases to support, Easter Basket Murder in January, and Torn Asunder at the end of April. But now, aside from some speaking appearances this summer, I am well and truly done.

Which leaves the challenge of what to post about here.

Because I got a late start in publishing, one of the ironies of retiring now is that I feel like I have finally put in my 10,000 hours. I’m beginning to understand what I’m doing when it’s time to go. So I thought, with everyone’s indulgence, I would use the next several blog posts to talk about what I think I’ve learned as a writer. Many of our blog readers are writers, and most of those who are readers are not ordinary readers. They don’t read a book a month or pick up a book at the airport on the way to vacation. They are readers who treat books and stories as others might treat a serious hobby. So I thought our readers might be interested.

One caveat: Since these are things I’ve learned along the way, you will find as the posts go on that I have violated or neglected every one of them in my work. Don’t bother looking for examples because you will definitely find them.

The first subject I will tackle is Voice.

VoiceVoice is the most amorphous yet important concept in writing fiction (or memoir or narrative non-fiction). If you look up definitions you will find them confusing and even contradictory.

Agents or editors will reject a book, saying, “The voice wasn’t quite there for me.” Or, “I didn’t love the voice.” Or, the famous expression attributed to various agents and editors, “I can fix everything but the voice.” For writers this can be frustrating. What does that even mean?

Here are some things voice is not.

The voice is not the prose style.The voice is not the way a point of view character or narrator speaks or thinks.The voice is not the order in which the tale is told, or the pace.Voice is instantiated in all those things, but describing them as voice is like describing symptoms in order to identify a disease. The symptoms are real, but the disease lurks deep inside.

Voice is the voice of the storyteller. It is unseen, behind, and above the story.

At it’s best, voice is

seductive. It says, “Come with me…”confident. “…and I will tell you an amazing story…”in command. “I won’t lose the way or let you down.”authentic. No matter how many layers of fiction are loaded on, ultimately, the writer’s intellectual and emotional life, values, and personality are there somewhere, on the page.How do writers develop voice? Prodigies have it out of the gate. But writing is a field with very few prodigies. Most people who begin writing seriously as grown-ups have several things working against them.

For one, writing is hard. I hate when people moan about how hard writing is because a) it is an entirely voluntary activity, and b) it’s not coal mining. But there is a lot to master– character, plot, pace, setting, theme, structure, and the words themselves.

For another, by the time they get serious, most writers will have heard hundreds of stories about the obstacles ahead and the infinitesimal chances of success.

And, to be authentic, writers expose themselves in a way that leaves them vulnerable. There is the inevitability of judgement and, often, fear of judgement. Judgement not just of the writing but of the writer.

So most writers begin supremely unconfident in their abilities. Exactly the wrong place to be. Because unconfident means in your head, worried, second-guessing.

How do you develop a seductive, confident, in command, authentic voice?

You can put in your 10,000 hours.(1)You can revise and revise until you are confident in the story and that confidence comes through on the page.You can let it all go, get out of your head, and trust yourself. (This is not as easy as it sounds.)I often liken writing to riding a bicycle. When you start, there are so many things to pay attention to–balance, steering, pedaling, braking, speed control, road, route, obstacles. But with practice, you aren’t conscious of the individual skills and mechanics. You just go.

Does having a seductive, confident, committed, authentic voice mean you will write a great book? Of course not.

There are the deluded, those whose confidence is sadly misplaced. And the arrogant–authors whose books are precious in a “look at me!” self-conscious way,. There are authors who are confident they have written the best book they can in the moment but who are still learning. The next book will be better. The best and the worst thing about writing is that there is always more to learn.

But the converse is also true. You can’t write a great book without a seductive, confident, committed, authentic voice propelling it.

So why not go for it?

Readers: What do you think voice is? Are you conscious of the author’s voice when you read or write? Do you think you should be?

(1) The authors of the original 10,000 hours study have disputed that they meant it exactly the way Malcolm Gladwell uses it in Outliers. But it sure is a handy way to describe how you get to Carnegie Hall. Practice, practice, practice.

May 6, 2024

Spoiler, spoiler, spoiler! (Not so much)

by Barb, typing this on our Wickeds retreat at Jessie’s fabulous house in Old Orchard Beach, Maine

So the time has come to talk about the end of the Maine Clambake Mystery series. Back when I tried to envision what it would like to go down this road, I thought this blog post would contain a spoiler. But since almost every single NetGalley, Amazon, and Goodreads review has mentioned that the twelfth book, Torn Asunder, is the last, I don’t think this is really a spoiler.

I didn’t pre-announce Torn Asunder as the last, though the Wickeds, my family, and close personal friends knew. I didn’t think I should say it was the end. I wondered if that would convince people not to buy the book or even not to start the series with another book.

I can see why people included the information it was the last in their reviews. It isn’t in any serious sense a spoiler. It doesn’t give away the solution to the mystery. But back in November, when reviews first started appearing on NetGalley and Goodreads, I wasn’t prepared to deal with the issue. When people asked outright on social media if Torn Asunder was the last, I bobbed and weaved, or didn’t answer at all.

I did address the end of the series in the Acknowledgements of the book but I’m going to answer some of the questions I have been asked since here.

Why did you decide to end the series? Did you run out of stories to tell about Busman’s Harbor? Or, were you bored with Busman’s Harbor?

I think, honestly, I could have made up stories about Julia Snowden and friends for years to come. The reasons I ended the series were personal, business, and creative.

The personal reason is the deadlines were getting to me, affecting my life and my health, not in a good way, and causing me to miss out on things I no longer wanted to miss. I know there are authors (more than one on this very blog) who can write many more books in a year than the one-book-and-one novella that were killing me. I used to think I could be better and faster if I just pulled myself together and applied more discipline. But then I turned seventy and adopted an approach to life I call “radical self-acceptance,” or the Popeye Philosophy, “I yam what I yam.” I decided to abandon my sixty-plus year project of trying to be a better or different person.

I write slowly. I read slowly. I need that frisson of fear of an approaching deadline to get the job done. In other words, my work ethic is that of a college sophomore. I was always going to write to deadline and the deadlines were always going to be tough.

I’m also pretty single-threaded. As a busy mother and boss, I multitasked, but it’s not my default approach. I prefer to be focused and immersed. There are projects beyond fiction-writing I want to tackle. Lots of people could do both, and more, but now I accept that I won’t.

This is who I am. The question was, what was I going to do about it?

The business reason was that the Maine Clambake Mysteries are what they are–mass market paperback and thoroughly mid-list. They were never going to be anything else. While entertaining a smallish number of people has been, in fact, very satisfying, there was no point in pretending I was doing anything different or that it was going to change.

Finally, there is the creative dimension. I am a completer. I have many flaws (see above) but I finish stuff. There is no string of abandoned projects in my life (even ones I probably should have). I like endings, full arcs, drawing a line under things. For me, fiction writing has always been about control. I worked on teams all by life and loved it. There is nothing more exhilarating than working with a group of people toward a common purpose. But I wanted writing to be something I did on my own. Writers often say, “My characters take over and do what they want.” To which I always say, “I have enough people in my life who don’t do what I think they should. That is not what I need from people in a world I am creating.” I wanted to end the series on my own terms. I wanted to finish Julia’s personal arc and leave her the place both she and I wanted her to be. Taking control of the ending was the only way I could do that.

What are you working on now? What will you write next? Will you publish again?

I’ve retired twice before and it’s my belief everyone who has ever retired, been laid-off, or quit a job has a list of things they have long wanted to do when they weren’t working. When my company, WebCT, was sold there was a constant joke among the former employees about how clean our closets, attics, basements, and garages were. In my experience, it takes six months to a year to recover and be ready for the new to flow in, depending on how intense the work was and how exhausted you were when it ended.

In examining my life, I find it breaks nicely into 10 to 12 year chunks. I worked for twelve years at Information Mapping, a company that offers a methodology for analyzing, organizing, and presenting complex written information. I was hired as a freelance writer and ended up at one time or another running every division and department in the organization except finance. But then it was time for me to go. The discipline for thinking that Information Mapping instilled in me is an immutable part of my character and I still have tremendous affection for almost everyone I worked with. After I left, I wrote the early drafts of my first book, The Death of an Ambitious Woman. Similarly, for ten years, I was at WebCT, a company that with several others pioneered putting both distance and traditional classes on the internet. Again, it was a fantastic experience which I still cherish along with the people I worked with. Afterward I dug out the Death of an Ambitious Woman manuscript, rewrote it and had it accepted for publication. I became one of the co-editors of the Best New England Crime Story series. Each ending, each hiatus has resulted in something better coming after.

I wrote the Maine Clambake Mysteries, twelve books and six novellas, for twelve years. I don’t know what comes next. I know that it may not be better than what came before. I do have a few ideas, but they are complex, requiring a lot of research and time, and I’m not sure if I’ll actually write any of them. Plus, having been a mid-list writer, there is no guarantee I’ll get published again. It may even make it harder. So we’ll see is the answer.

Lightening Round(Spoilers ahead) Do you regret breaking up Julia and Chris?

No. Chris was never going to be right for Julia, which I feel badly about because I made him that way. However, if I’d known I would end at twelve books, I would have broken them up sooner to give Julia and Tom’s relationship more time to develop.

Is there anything you would have changed in the first book if you had known the series would go to twelve?

I don’t think so, though I certainly would have written that first book better if I had the experience I have after writing twelve.

Who is your favorite character to write?

Gus and Mrs. Gus, Fee and Vee Snugg. It’s so freeing to write secondary characters.

Is there a character whose arc became a pain?

Not really. I really enjoyed writing Quentin Tupper, but unlike all the other regulars he is a summer resident. Sliding Quentin in and out of the series was a bit of challenge.

The other was Le Roi the Maine Coon cat. I hadn’t intended to have a cat, but when I saw what life was like for a cat on the real Cabbage Island, I had to include one. However, Le Roi was always in town when my characters were on the island or on the island when my characters were in town. Keeping track of his whereabouts and making sure there was someone available to feed him was a real pain.

Who’s a character you should have killed off?

No one. Julia’s brother-in-law, Sonny, was designed in the series proposal to be the antagonist. Some people who didn’t make it to the turn about three-quarters of the way through the first book, Clammed Up, gave up on the book due to too much family conflict. But I wouldn’t kill Sonny. His wife and kids would suffer too much and he and Julia both grow and change each other, however minimally, which was satisfying to write.

Who’s a character who should have been spun off?

Kensington approached my agent, casually, about a spinoff featuring Fee and Vee Snugg. I didn’t want to write another series in the Busman’s Harbor world, so I never followed up.

Thank youFinally, at the end of the world’s longest blog post, for the superfans of the Wickeds and the Maine Clambake Mysteries still with me, I want to thank the readers. As I say in the Torn Asunder Acknowledgements, you have been a joy of my life. You have given me this opportunity and the community that has gone with it.

The many, many emails and social media comments I have received since Torn Asunder was published have been lovely and 100% supportive. Many have expressed satisfaction that the series actually resolved and they knew what happened to the characters. I can’t express how much I have appreciated these notes.

With tremendous gratitude. Barb

Readers: How do you feel about series ending? Do they run their course or should they go on as long as the author lives?

April 23, 2024

Torn Asunder Released and a #Giveaway!

I’m thrilled to announce today’s release of Torn Asunder, the twelfth novel in my Maine Clambake Mystery series. I loved writing this book, which takes place entirely on Morrow Island, the island in Busman’s Harbor, Maine where my protagonist, Julia Snowden, runs the Snowden Family Clambake.

To celebrate, I’m giving away a signed copy of Torn Asunder to two lucky commenters below.

Here’s the Description

Here’s the DescriptionIn Barbara Ross’ award-winning series featuring sleuth Julia Snowden and her family’s coastal Maine clambake business, Morrow Island is a perfect spot for a wedding—and a Snowden Family Clambake. Julia Snowden is busy organizing both—until a mysterious wedding crasher drops dead amid the festivities . . .

Julia’s best friend and business partner, Zoey, is about to marry her policeman boyfriend. Of course, a gorgeous white wedding dress shouldn’t be within fifty yards of a plate of buttery lobster—so that treat is reserved for the rehearsal dinner. Julia is a little worried about the timing, though, as she works around a predicted storm.

When a guest falls to the floor dead, it turns out that no one seems to know who he is, despite the fact that he’s been actively mingling and handing out business cards. And when an injection mark is spotted on his neck, it’s clear this wasn’t caused by a shellfish allergy. Now, as the weather deteriorates and a small group is stranded on the island with the body—and the killer—Julia starts interrogating staff, family members, and Zoey’s artist friends to find out who turned the clambake into a crime scene . . .

I’ll be doing some appearances this spring-summer and love to meet readers! Each listing below provides links to sites where you can get more information.

Friday through Sunday, April 26-28, 2024 in Bethesda, MD, I will be at Malice Domestic. Registration required. I will be moderating the panel, “Cozies: All in the Family,” with Donna Andrews, Olivia Blacke, Maya Corrigan, and Maddie Day on Saturday, April 27, from 10:00 to 10:50 a.m. in Ballroom A.Saturday, May 18, 2024, 10:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. in Groveland, MA. I will be at the Kensington Cozy Con, sponsored jointly with Jabberwocky Bookshop and the Langley-Adams Library. I will be on the Wicked Authors Panel with Maddie Day, and Cate Conte from 1:00 to 1:45 pm, and will be available to chat and sign books all day. Pre-registration is suggested.Thursday, June 13, 2024, 6:30 to 8:00 p.m. in Scarborough, ME. I will appear with Maine authors Dick Cass and Kate Flora in an interactive Making a Mystery panel at the Scarborough, Public Library.Friday through Saturday, June 14-15, 2024 in Portland, ME, I will be at at the Maine Crime Wave. Friday evening is free and open to the public. Saturday requires pre-registration. I will be teaching the workshop, Examining the Bones (that Hold your Story Together): The Structures of Mysteries and Thrillers, 10:30 to 11:30 a.m. on Saturday. I will also introduce the keynote speaker, Juliet Grames, SVP and Editorial Director at Soho Press, and participate in the last panel of the day.Thursday, July 11, 2024 at 6:30 p.m. in Southport, ME. I will be speaking at the Southport Memorial Library.Additional talks and panels are in the works so be sure to check the Appearances page on my website.

The GiveawayIn my head all the time I wrote the Maine Clambake Mystery series, Julia was worried about a diner having a massive allergic reaction to shellfish. When I got to book twelve (and six additional novellas) and hadn’t used it yet, I knew the omission had to be remedied.

Readers: Do you or does anyone close to you have any serious allergies? Or food allergies–serious or merely inconvenient? Answer the question in the comments below or just say “hi” to be entered to win one of two signed copies of Torn Asunder. Winners will be notified on April 30. Sorry, US only due to mailing costs.

April 8, 2024

The Wednesday/Thursday Club

by Barb, first post of 2024 from Maine, where there is snow on the ground and the temperature went down to 32 degrees last night. Quite a change from Key West. Here in Portland, we’re in the “Path of Partiality” for the eclipse today, and I am interested to find out what that means.

It is appropriate that with Torn Asunder, the 12th book in the Maine Clambake Mystery series, coming in 15 days that this should be (almost certainly) the last post about book 11, Hidden Beneath.

In Hidden Beneath an old friend of my protagonist Julia’s mother disappears while out for an afternoon swim. She lives in a summer colony on an island in Busman’s Harbor and is a member of the Wednesday Club. At the beginning of the book, five years after the disappearance, the woman has been declared dead. The remaining members of the Wednesday Club host her memorial service, which Julia and her mother attend.

Later in the book, one of the daughters explains the club to Julia.

“What exactly is the Wednesday Club?”

She smiled. She had pleasantly round cheeks and a dimple near her mouth. “The Wednesday Club is nothing more and nothing less than a group of women who pick a topic, say Pompeii, or Elizabethan England, or the Bloomsbury group. Then each member chooses an aspect of that topic and writes a research paper about it.”

“A research paper?” Of all the things I imagined April was going to tell me the club did, writing research papers wasn’t one of them. “Writing a research paper for summer fun?”

April chuckled. “With footnotes and everything. The writing takes place over the winter, when they have access to libraries and such. The papers get presented in the summer, one every Wednesday. The paper’s author hosts the meeting in her home. They have the same little sandwiches, cookies, and fruit squares for every single meeting.”

In the Acknowledgments for Hidden Beneath I wrote:

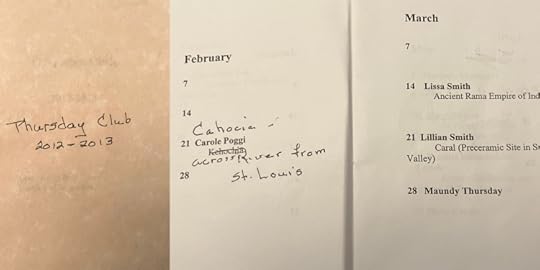

My mother belonged to a group called the Thursday Club, which is more or less as described in the book. It was a chance for college-educated women to exercise their brains. Also to pull out the silver tea service and china cups once a year. It was already an anachronism when my mother joined in the 1960s, but it went on into the 2000s, and for all I know, it may be going still. I have the little notebook where Mom kept the lists of research topics and menus. Nothing was better than coming home from school the day your mother hosted. There were always finger sandwiches and petit fours left over.

From the time my mother was asked to join, when I was in junior high or high school, I have been fascinated with the idea of the club. It seemed like a delightful anachronism, not to mention a great way to gather a pool of suspects together.

When it came time to use the club in a book, I renamed it the Wednesday Club, due to Richard Osmond’s completely delightful Thursday Murder Club series. I emphasize I didn’t know much about the club. The meetings, including the one held every year in our home, took place while I was at school. My mother died in 2013 and any knowledge or source thereof ended there. I didn’t do any research about the club for Hidden Beneath. When I wind people or things I vaguely know about into fiction, I am better off not learning too much. That way the “truth” of the matter doesn’t trip up my imagination. I can get the person or entity to be what it needs to be for the sake of the fiction. For example in this case I had to twist the schedule and practices of the club around to work in a summer colony. Also, if I don’t know I can be sure whatever I’ve created isn’t too much like the real thing.

Hidden Beneath went out into the world last June and I thought that was the end of it. Then I happened to come upon the little book with the paper topics and authors from my mother’s last year and noticed a friend of hers had delivered a paper on the history of the club. Sure enough the friend was on Facebook. Desperate for a blog topic last August, I reached out. A month or so ago a package containing not one but three histories of the Thursday Club arrived in my mailbox. All three histories are so charming and amazing and illuminating I wish I could offer you the chance to read them in their entirety but here are some excerpts for you to enjoy.

The first was written in September 1929 by Mrs. Eben Greenough Scott.

One day in early September, 1885, it happened that several ladies met at the house of one of them.

In looking forward to the coming winter, plans were discussed for study to occupy their leisure hours. The Shakespeare Club, to which they had belonged, had died a natural death the preceding year.

A number of the group had been studying Dante for three years past, and now the others wished to join in something more general. Mrs. Stanley Woodward, one of those present, turned to me and said, “Cannot you plan something that would interest us all?”

I asked for time to consider, and after thinking it over, proposed a study of the History of Art. A few days later, eight ladies met at my house, I being the ninth (the number of the Muses).

I had no experience in this co-operative kind of study, but thought it was worth trying. We formed no organization, but agreed to meet once a week to see what we could do. There was no Public Library at the time, and our books were few, consisting chiefly of the Encyclopedia Britannica and a few antiquated books on archeology.

As I look back I see the courage of ignorance in our undertaking, but we plunged boldly into Egypt…

The second history was written in 1980 in celebration of the club’s 95th birthday. The author, Phyllis McCausland River, catches us up and fills in some details about the original founder and history writer, Mrs. Eben Greenough Scott.

When she was eighty-five she broke her hip. Knowing she would be laid up for a long time she sent her nurse uptown to buy her a Spanish grammar. All her life she had spoken French and Italian fluently. She lived 15 more years, until within 5 months of her hundredth birthday. Two days before her death she wrote out checks paying all her bills. Once when a friend 20 years her junior complained that she feared her mind was slipping, Mrs. Scott leaned forward in her chair, looking earnestly at her friend and asked, “With what are you feeding it, my dear?”

To me this is such a wonderful portrait of a grande dame, a ferocious lady of a certain time and disposition.

The subject of art eventually became confining. In 1933 the club members branched out into the world. That year the subject was Mexico, later Sweden and Norway, eventually covering the greater part of the globe. Members pursued their own interests. One wrote often of flora and fauna, another architecture, another costumes.

We have no Constitution and By-laws, no expenses and no rules. Our underlying principles have been two: cooperation and loyalty.

Yet we are still the same Thursday Club, but like all manners and morals today we follow a more flexible code…We still enjoy each other’s company and brain-children (papers); no one strains to lay a lavish tea table; we never gossip…we have a deadline and a goal once a year to have the house in ship-shape order and condition; and best of all, we learn so much we never knew before about all sorts of places and people.

Am I allowed one more observation? It has to do with the question of why the Thursday Club has vitality to this day. It seems anachronistic. Perhaps the answer is that it is refreshing. We lay aside a few hours of time to do serious reading, time to think, time to renew a somewhat leisurely way of life. Thursday Club does something for us.

The most recent history was written in 2019 by Kathy Montz Miller as the club approached its 135th anniversary The author puts the history in context, placing the accomplishments of women like Margaret Sanger, Jeannette Rankin, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Amelia Earhart, Shirley Chisholm, Sandra Day O’Connor, Sally Ride, Condoleezza Rice, Nancy Pelosi, and Hilary Clinton alongside the evolving story of the club to illustrate how women’s roles have changed.

The 2019 history describes the evolution from women arriving in carriages or sleighs, and then in cars with drivers and then driving themselves. Hats were worn until the 60s, slacks were possible in the 70s.

We are now comprised of more professionals than we ever have been. We no longer dress up for Thursday Club, but that too is a sign of the times as many members come directly from work or other meetings.

I notice the names in the annual booklet are ever more diverse. I wonder of they wives if the coal barons who were present at the founding of the club imagined that one day their descendants would be sitting discussing scholarly papers with the descendants of the men who worked in those mines and the shopkeepers who sold them goods. This change over multiple generations is what Hidden Beneath is about.

The paper ends by returning to the words of Mrs. Eben Greenough Scott, whose given name we learn from a later history (not the one she wrote) was Elizabeth.

All our newcomers are most welcome. We look for growth and renewed energy from their presence. May they and all, lone continue to enjoy the work and companionship of the Thursday Club.

The club continues to this day, 139 years in September. It seems truly remarkable in this age of binge-watching and internet and bowling alone. I know how much the group meant to my mother over decades, both intellectually and for the camaraderie, and I’m glad it’s still out there. (And I’m sorry about all the secrets and the murders.)

Readers: Can you think of an example of an organization with this kind of longevity in your town?