Neville Morley's Blog, page 25

December 18, 2020

Blogs of the Year 2020

One of the things I always do in the Christmas vacation is catch up on the year’s music that I’ve missed. Partly it’s a matter of having a little bit more leisure to try out the unfamiliar, that might throw me off my stride or drive me up the wall, rather than sticking to things that I know will relax me or offer a suitable background for lecture prep or marking. Partly, though, it’s because of the End of Year lists – not so much those of the mainstream press, but something like The Spill, for its random eclecticism and the fact that I know that if contributor X likes something then it is at least worth a listen. It’s how the Spotify algorithm ought to work: a selection of people from across the globe with very different tastes, just presenting what they thought was great. Especially this year, when my involvement in composition classes means I’ve been listening to much more jazz and much less of anything else, this is invaluable in giving me a sense of what else is out there. (And I now have some new marking music – strong recommendation for the latest album from Ulrike Haage, not to mention her soundtrack to the recent Berlin 1945 series).)

And that is what I aim to do with this post every year: to offer you all a selection of what I came across that seemed really great and/or thought-provoking and that would be worth your time. It has an added impetus this year, as I have been really feeling the lack of something like it on a more regular basis; that is to say, I’ve had more time for reading but with less ability to concentrate on a proper book, so blog posts are ideal – and so I have often been reduced to scanning the Twitter in the hope of finding mention of something interesting. One hears tell of the glory days of the blogosphere, when everyone would be engaging with and recommending everyone else; I missed all that – and my sense is that there seem to be fewer blogs and fewer posts on them (Crooked Timber has felt very quiet).

The people with a monetisable profile are busy monetising it in proper outlets (and don’t need my advertising), and everyone else is too tired or dispirited? It has felt like this at times – and my own viewing stats have continued their year-on-year decline, albeit a bit less precipitous than in the last few years. Writing about an obsolete subject in an obsolete medium… But I still love the freedom of the shortish impromptu essay or spontaneous thoughts and reactions – this is where one should publish experimental creative musings prompted by reading a book, not trying to pass them off as a proper review – and there are still amazing people out there writing amazing things…

January: Miko Flohr on ‘global Romans’, seeing the classical world through postcolonial eyes, and considering his own relationship with the empire; Venkatesh Rao on the Internet of Beefs; and the first of many excellent Chris Grey posts this year offering ruthless common sense on the idiocies of Brexit.

February: Tegan Burnett on whether academic blogs can be trusted; Charlotte Lydia Riley on academic sexual abuse; Anton Howes on why untold generations failed to invent D&D and what this tells us about process of technological innovation.

March: the ever-amazing Deborah Cameron on gendered colour vocabulary; and the equally reliably brilliant Maria Farrell on The Prodigal Techbro; Keri Facer on thinking about the future in the time of pandemic. And as we go into coronavirus lockdown…

April: Will Pooley on antibiography; Jake Newcomb on Rage Against The Machine as Radical Historians; Helen Lovatt, as part of her new project on The Power of Sadness, on COVID-19 and grief.

May: Charlotte Riley (again, and it’s not just because I’m in her new collection on Free Speecg) on British exceptionalism; Maria Farrell (again) on post-viral fatigue – which was horribly close to the bone, as one reason this month is a bit thin is that by this point I was struggling with the after-effects of the plague…

June: Katherine Blouin on the loss of beloved pets; Gemma Tidman on RhodesMustFall.

July: Sam Kinsley on mental health and performative tweeting in lockdown; Vanessa Stovall’s excellent response to that Joshua Katz article; Mixed Classicist‘s reflections and call for action on what may be an even more dreadful article in The Spectator.

August: Rebecca Kennedy and Maximus Planudes on citation practices; my wonderful collaborators Fast Familiar on their experience of switching things online; Roberta Mazza on the lessons of the ‘Jesus’ wife’ fragment.

September: Catherine Baker on recording Eurovision videos and the lessons for online teaching; Adam Roberts on his pandemic project of translating the Christiad; anonymous game designer on QAnon understood as a game, not least as a key to understanding Thucydides’ appeal; Foluke Ifejola Adebisi on Black Lives Matter.

October: Josephine Grahl on living alone in lockdown; the indispensable Sententiae Antiquae on its ten-year anniversary. Yes, by this point term was starting to get to me, and spare time and energy for reading largely disappeared.

November: Bret Devereaux on military history; Brett Scott on the Flintstones History of Money. Spare time and energy still absent…

December: Michael Shanks on academic voices in classical studies/; Chris Bertram on labour rights and migration, even if this isn’t technically a blog post; Notes from the Apotheke on work-life balance – if only I’d learnt something like this in graduate days…

And finally, if there’s one positive thing that’s come out of Coronavirus, it’s Cora Beth Knowles’ wonderful series Comfort Classics.

December 16, 2020

The Glorious Land

Fascinating times on the Twitter yesterday, after I posted a remark about the incoherent racism of the “indigenous population of Britain” component of the ‘Great Replacement’ conspiracy theory and attracted a lot of very angry people with English flags in their handles. One suspects they’ve been conducting broad searches for the key terms ‘indigenous population’ and ‘racist’, since none of them looked like the sort of accounts who would normally be looking for random thoughts on Thucydides and jazz composition.

Of course the idea of an “indigenous population of Britain” is incoherent racist gibberish; it aims to subsume Celts, Romans, Normans, the builders of Stonehenge, and assorted Germanic and Scandinavian peoples into a single special category without naming the common thread.

— Neville Morley (@NevilleMorley) December 15, 2020

Two things really stood out for me. The first is that the vast majority were perfectly polite; angry, yes, and incredulous that I was not backing down in the face of their powerful assertions about genome analysis, but apart from one assertion that obviously I was simply obeying the orders of my masters in the communist media and one person apparently cross that my profile picture includes a Siamese cat, a total absence of abuse, threats of violence etc. Perhaps there would have been more if I’d bothered to engage, but basically this is another data point for the general truth that being a man on social media is playing the game on its easiest setting.

The second is how far the responses essentially proved my starting point: this is an incoherent ideological claim whose sole function is to present a far-right racist agenda as a matter of objective scientific and historical truth and natural justice. This is OUR land; WE were here first; other indigenous peoples get special privileges (they seem particularly furious about the Maori, for some reason), so it’s only fair that the Native British should too. This then entails a frantic two-step between claims about unbroken genetic heritage since the builders of Stonehenge, with invading forces contributing minimally to the pure bloodline, and claims that Celts, Vikings, Normans etc. are all closely related so that gene mixing is all good and historical (don’t mention the w-word…).

This suggests that they disagree with each other almost as much as they disagree with me: the British Exceptionalists versus the Pan-Nordics, the Genetic Purists versus the Selective Input Of The Right Sort Of Blood, the Autocthonists versus the Spirit Of The Volk crowd and so forth. But of course this is either beside the point – they started with the conclusion, that they should have special status in Their Own Country, and are simply developing arguments to justify this in publicly acceptable terms – or it’s precisely the point, that True Britishness in these terms is highly malleable and inclusive much of the time, just not in the one obvious respect. Which isn’t racism, or else it’s racist to talk about Native Americans, so there.

I was a little surprised to be accused of denying the existence of Britishness, suggesting that it’s not a real thing because it’s made up of different ingredients (What about a cake, EH?!?). On the contrary, that’s why I like it as a cultural identity; it reasonably characterises my own mongrel heritage, and it can be open and inclusive and capable of constant change and refinement – a cake that’s significantly improved by West Indian sugar and Indian spices and so forth rather than sticking rigidly to the bland 1930s recipe…

Part of the agenda here is to make ‘British’ a less accommodating identity by making it less cultural; going beyond the infamous ‘cricket test’ (which would have got me thrown out of the country…) to suggest that identifying with Britain is not enough, you need to have ancestors who were born here centuries ago, or millennia, or at any rate before 1948. Some people, then, can never be truly British – but that’s fine, because none of this is about discriminating against them (that’s what Bad Racists do), just treating Proper Brits fairly.

What worries me is how much of this stuff I can imagine receiving nods of assent from otherwise decent people whom I used to meet at drinks parties down here in darkest Somerset, back when such things happened or at least when I used to go to them; it’s all just common sense, and it’s expressly claimed as Not Racist so that’s all right. The discourse is cleverly designed to mainstream ideas that justify and promote racial discrimination without ever stating this as the intended outcome, while making it ever harder to call them out without appearing to disparage the natural, blameless feelings of ordinary decent folk. After all, the Maori…

I must go and find a white van to respect.

December 12, 2020

Mr X

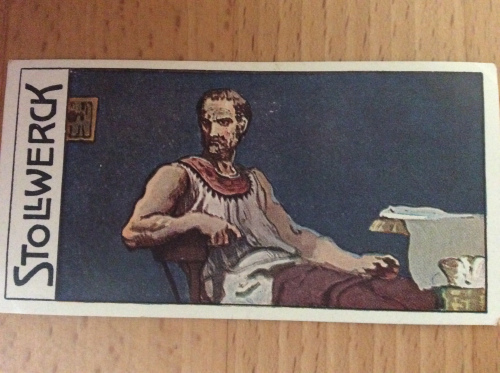

It’s the most chocolaty time of the year, so it seems like an appropriate time to get round to writing about the latest addition to my incredible small but interesting collection of Thucydideana: a chocolate card!

Köln-based chocolate manufacturer Gebrüder Stollwerck turns out to have been one of the most innovative enterprises of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In 1887 it introduced the world’s first chocolate bar vending machine, thousands of which soon appeared across Germany and in New York railway stations. In the early 1900s it also became a leading manufacturer of cinematography and phonographs, including one which played chocolate records. And way back in 1840, long before the cigarette card (c.1875) or the Panini football sticker (1960), the firm’s founder came up with the idea of including a collectible picture with every bar of chocolate, with special albums for preserving the whole series appearing a few decades later.

Thucydides dates from 1908, and the collection ‘Helden des Geistes und vom Schwert (Heroes of the Spirit and the Sword). It’s a copious category: heroes of myth (classical, Nordic and Germanic), of ancient, medieval and modern history, and of Geist and Kultur, including scientists, inventers, philosophers and authors. Thucydides featured as one of the Beruhmte Dramatiker und Historiker (Group 411), along with the three Attic tragedians, Herodotus and Thucydides.

There are two things I really like about this card, besides the whole back story. The first is the information on the back of the card (repeated in the album, so it could still be read after the card had been stuck in).

In historiography, Thucydides represents a high point that it never attained again in antiquity and in the modern period was only recently reached. He was indeed not a full-blooded Athenian, but fully absorbed its elements of education, and became statesman and general. Because in this role he was unable to present the capture of Amphipolis by the Spartan general Brasidas, he was banished, and as a result had the leisure to write the history of the Peloponnesian War. After a twenty-year exile he was allowed to return to Athens. He died when, in the eighth book of his work, he had reached the year 411. His work is of monumental greatness. The unostentatious construction and close control are exemplary. He depicts not only the war, but in the introduction also the development of Greece from the earliest times.

Mostly that’s boilerplate stuff, but it’s handy to have such an explicit statement of the ‘not matched until modernity’ judgement. It is interesting to speculate about the implications of some of the less usual elements. Why present his ‘schlichte Anlage und strenge Geschlossenheit’ rather than any other aspect of his work? Why is it so important that he also discussed the early development of Greece? Why so much emphasis on the fact that he was a half-blood but nevertheless absorbed Athenian education fully – this isn’t a theme that I recall from any 19th-century academic discussions?

What I really love is the picture. The expression is priceless: THUCYDIDES IS DISAPPOINTED IN YOU, AND WITH HUMANITY GENERALLY. Maybe the artist has just been given the biography on the back of the card, and has gone with the two themes of military strength (look at that right arm) and anger. It’s good to have a style that is something more than bland neoclassicism (Stollwerck seem to have gone quite heavily for modern, almost expressionistic artists for some of their cards). Above all, there is a sense of the artist taking the familiar ancient portraits of Thucydides as a starting point, rather than as the be all and end all.

I originally thought of writing this whole post about modern depictions of Thucydides and what they suggest about how he is imagined or valued. But it’s clear from a quick survey that most of them simply reproduce one or other ancient portrait bust (not the mosaic depictions, oddly enough, and that’s an interesting question in itself) – and that immediately raised the thought that these, too, are basically imaginary – I don’t think we have anything remotely contemporary, but I need to check – and opens up a whole can of worms about which I know very little. More research is needed; maybe no one has written about ancient Thucydides portraits, but surely someone has written about ancient portraits of Homer, which would be an interesting comparison.

This may end up as a long blog post, or maybe even a proper article – just when I think I’m getting to the natural end of my Thucydides researches, he pulls me back in again… For the moment, just enjoy the thought that, once upon a time, your Christmas chocolate bar might have come with an ancient Greek historian glaring at you…

December 3, 2020

Losing My Religion

A crucial element of Thucydides’ depiction of the plague in Athens is that it appears as, so to speak, a heuristic crisis: it is an event that no one can make any sense of. It’s not that fifth-century Athenians were unfamiliar with epidemics, in myth, literature and reality, but all of those had an explanation in terms of their inherited concepts and assumptions. In this situation, however, every explanation falls short – belief in the fulfilment of oracular prophecy or other supernatural explanation, rumours of enemy action, even the more recently developed ideas of the doctors. Whatever the actual nature of the disease – and this point holds true even if we follow the idea that there wasn’t actually a single plague, but a multitude of more common diseases, perceived as a single baffling phenomenon – Thucydides shows how its unfathomable and irresistible nature then became the dominant influence on behaviour, sweeping away the traditional institutions of religion, law and social norms by revealing that everything was actually random and unpredictable. Why pray when it doesn’t help? Why deny yourself pleasure when you might die tomorrow? Why obey the law when you probably won’t get caught? Why strive for virtue when it doesn’t bring any reward? Why worry about what the neighbours think when they might be dead tomorrow?

We are, thankfully, a long way from that degree of crisis, perhaps because most of us still have faith in the power of the scientific understanding of plague to make sense of things and save us. But it’s still an interesting starting-point for reflection, on two related issues. The first is the persistent promotion of a limited, fetishised imago of ‘normality’, even when this not only makes little sense but will be actively harmful: most obviously the obsession with ‘a normal Christmas’ even at the expense of rising infection rates and a still more severe lockdown in January, where people might have settled for a sensible, COVID-appropriate celebration this year. I can’t decide how far this is driven by the government’s belief that this is what people want to hear, and reluctance ever to announce bad news in a serious manner, and how far it’s all about the attempted rescue of the pre-Christmas shopping binge. Quite possibly they don’t know either.

In my little corner of the world, this has been most visible in the insistence of the government on face-to-face in-person teaching as the only truly acceptable mode of higher education, in the confused guidance about how to get everyone home for Christmas (continuing assumption of a default model student as 18-21, living away from home during term and returning to single nuclear family with labrador during holidays), and in the exciting new even more confused guidance about getting everyone back in the new year. Again, it’s over-determined: the persistence of very traditional ideas of what universities are all about, drastically simplifying a complex reality, and the fact that ignoring messy complexity in this manner just happens to sidestep and displace issues of money, accommodation costs etc. It’s as if the Athenian answer to the plague was having Pericles repeat his funeral oration on a regular basis as a defence against the Spartans poisoning the wells.

At least within the subset of my group of first-year tutees who turned up for a session on well-being this morning – which in retrospect would probably have gone better if I’d just introduced them to the cats rather than trying to dispense advice – this is already having a somewhat Thucydidean impact: asked to describe one of their concerns anonymously on Padlet, they returned time and again to themes of fear, uncertainty, not knowing how to prepare for what problems might arise, and feelings of doubt about the point of it all. Okay, none is this is exactly new or unprecedented, but I’m not sure it would have got more or less unanimous assent in the past. The study of classical antiquity can feel like a luxurious indulgence at the best of times, but perhaps especially so when the future is so dark and potentially apocalyptical.*

The obvious contrast between Athens and today – that is, among the obvious contrasts – that is, one of the innumerable obvious contrasts – is that the demos was the government, and vice versa, rather these being separate entities. The closest we get to a Prime Minister desperately trying to deflect blame and insist that everything is fine and we’ll come through this soon is Pericles’ resentful final speech, continuing to insist that he’s right about everything and it’s the Athenians’ fault for not trusting him – and, while that actually does offer quite a lot of parallels in rhetorical terms, the demos retained the power to vote for a different course of action whereas we remain powerless, just trying to anticipate future events and dramatic changes of course so we can try to prepare for them.

And perhaps this accounts in part for the continuing insistence on maintaining things like university terms and Christmas shopping and summer A-levels and GCSE exams, making lots of minor adjustments and hasty bodges in order to keep the old Ptolemaic system staggering on rather than contemplating a new approach. The demos might be more open to, say, scaled-down festive celebrations or more emphasis on teacher assessment, or more money and power to local government to manage the pandemic, but they’re not being given the option.

So we have the appearance of, well, not ‘business as usual’ per se, but ‘business as usual’ as the unquestioned default state to which we will return as soon as possible – while underneath the taken-for-granted rightness of many aspects of this have been seriously shaken. And this is the second issue I mentioned some paragraphs ago: the weakness of the entire British higher education model, the corruption of the relationship between government and (selected) private enterprise, the incompetence and venality of our ruling class have all been thrown into sharp relief by the pandemic, only partly disguised by the media’s obsession with making this all about the court politics of Johnson’s gang. As in Athens, the plague doesn’t create problems and divisions; it reveals the hollowness and fragility of the funeral oration’s version of society.

This isn’t to suggest, as the more excitable ‘heighten the contradictions!’ people tend to do in such situations, that we’re on the cusp of a revolutionary re-ordering of society, as the majority realises quite how badly it is governed and how far the system is stacked against them. On the contrary, recent history shows how easily distrust and discontent can be turned to the advantage of the elite. The Athenians did pull themselves together and (wisely or not) continue to fight Pericles’ war; insofar as the plague offered them an opportunity for a new course, they didn’t take it. But it does imply that ‘normality’ may be harder to restore than just allowing people to hug their grandparents – even if we are, as the Education Secretary has recently suggested, the greatest little country in the known universe.

* Perhaps unwisely, I did note that one of the rites of passage for any first-year classics or ancient history student was facing the interrogation of elderly relatives at Christmas as to “why are you doing that, then?”, and the one thing to be said for the pandemic was that they’ll probably be seeing fewer elderly relatives this year…

November 26, 2020

Bad Company

In 1924, the Croatian writer Miroslav Krleža was travelling on a night train from Riga to Moscow, and fell into conversation with a Lithuanian schoolteacher of German heritage who was reading Oswald Spengler’s Prussianism and Socialism. She had, she said, become interested in him when he held a lecture in Riga the previous year at the invitation of the Courlandic German Bund.

“But everyone was disappointed with the gentleman. He is a boring, elderly professor with illusions of grandeur, who earned a pretty fee with his lecture. The Courlandic German Bund had to pay for his trip in a sleeping car, first class, all the way from Munich to Riga and back, and on top of that even the door receipts, and then he came, read from his papers for half an hour, and at the banquet did not speak a single word with anyone the whole evening. A disagreeable, opinionated fool!”

I don’t know if this is a remotely representative anecdote – ‘elderly’ is rather unfair, for a start, since Spengler had just turned forty at this date – but I treasure it nevertheless. The publication of the first volume of Der Untergang des Abendlandes, his sprawling and idiosyncratic overview of world history in terms of the natural organic development of different cultures, had made Spengler a celebrity, especially in German communities across Europe, and so able to command substantial speaking fees without feeling the need to offer more than the bare minimum in return.

Or perhaps he had other things on his mind; Spengler was just about to embark on a brief and entirely unsuccessful career in politics, seeking to put into practice the ideas he had developed in Prussianism and Socialism – a highly nationalistic vision of society without trade unions, strikes, unemployment benefit, progressive taxation or days off work, united in harmony under a dictatorship who would conduct the people like an orchestra. True socialism is about the innately Prussian qualities of discipline, self-sacrifice, productivity and working for the greater good (“the greater good”), and Frederick William I of Prussia had been the first conscious socialist, whereas Marxism, tainted with the spirit of Englishness, was “the capitalism of the working classes”, setting poor against rich rather than uniting everyone in the service of the nation. We have the origins of recent silly Twitter “the Nazis were socialists therefore all socialists are Nazis” debates right here…

This is quite entertainingly mad, and deserves to be as well known as the ragbag of misappropriated scientific concepts he applied to human history in Der Untergang. Spengler is a fascinating figure, with ideas that merit consideration, and not solely as a ‘what the hell were people thinking in the mid-20th century?’ cultural artefact. But it’s less obvious that he offers a good model for contemporary research, as opposed to an object of contemporary research – let alone that he’s the sort of person you want to dedicate a society to and still expect to be taken seriously.

The Oswald Spengler Society engages in the understanding of the principles underlying Human Evolution and World History and its perspectives. It is dedicated to the comparative study of cultures and civilizations, including pre-history, the evolution of humanity as a whole and extrapolations regarding the possible future of man.

Uh huh. That could be unexceptionable boilerplate; loose references to ‘evolution’, potential reification of “cultures and civilizations” and vague portentous aspirations to futurology notwithstanding. It’s the Spengler name that initially rings alarm bells – an informal poll of acquaintances in politics and history found precisely nobody who thought this was a name you’d choose for a purely academic exercise – but maybe, if you’re a researcher interested in comparative history and you meet a wealthy potential supporter with a Spengler obsession, maybe you’d go along with it as a means of funding some worthwhile conferences…

…and establish a Spengler Prize, to be awarded at the conference, and award the first one to the French novelist Michel Houllebecq. As the Society’s president described him:

…an author who has given expression like no one else to the deep feeling of loss and frustration that is at the heart of The Decline of the West—and who has sounded the alarm of the potential take-over of what remains of Europe by Islam.

Yes, I think the subtext is rapidly becoming text. Amusingly, Houllebecq’s acceptance speech seems to have disappointed his hosts by being insufficiently gloomy about the imminent doom of the West, even suggesting optimistically that history might not be wholly predetermined.

Still, plenty of opportunity for discussing the impact of immigration on European culture and society, a theme on which many of the Society’s officers have expressed their views, with or without dubious classical analogies. And the publication of the relevant speeches as Volume 2 of the Journal of the Oswald Spengler Society found its perfect home in Edition Sonderwege (no, nothing dubious about that name), described even by its parent company (publisher of various luminaries of the AfD) as “ein Tummelplatz für Konsensstörer, Schimpfer, Spötter, Polterer, Misanthropen und ähnlich antiquarisch gewordene Temperamente.”

I imagine that you don’t submit a proposal to a conference celebrating the centenary of Der Untergang des Abendlandes without some idea of what you’re getting into, even if one might have hoped for a bit more subtlety. This year’s event was much more interesting; explicit emphasis on comparative global history (‘from Herodotus to Spengler’), a number of papers that look from the titles to be perfectly sensible discussions of pre-modern historiography, alongside the ones asking questions about whether Western culture has chosen mass immigration as its suicidal end stage (yes, obviously any credible academic conference would let that one through, if the abstract was good enough), and the necessity of a hybrid approach whereby online participants might remain happily oblivious to what’s going on around their papers (which obviously underlined the acuteness of Spengler’s prophecies about the doom of western civilisation).

And the second recipient of the Prize, following Michel Houllebecq? The eminently credible and distinguished Walter Scheidel. One assumes he accepted it; there’s been an odd silence about this on his social media, but YouTube has a video of the Society’s President offering the ‘ceremony speech’. Alas, no sign of Walter’s acceptance speech, as it would be interesting to know how he responded to the, erm, interesting account of contemporary historiography and the role of comparative approaches. One might also imagine that an award speech would spend more than one minute out of sixteen and a half talking about the recipient and his work – but in the circumstances, perhaps it is better not to receive too many compliments from some sorts of people. Being praised for “clean methodology”, that is to say the absence of any consideration of class or race, would be bad enough…

Let he who is without embarrassing past associations cast the first aspersion? That’s me out, then. A limited amount of internet research, if anyone was bothered, would reveal that I once spoke at a summer workshop organised by the Institute of Ideas, part of the sprawling hard-right libertarian network established by former members of the Revolutionary Communist Party that includes such luminaries as Baroness Fox of the Brexit Party, Spiked magazine and Boris Johnson’s political adviser Munira Mirza, and organises debates about the damaging effects of immigration on British society and the like. (But at least I just went there, gave my talk and left. I’ll spare the blushes of the friend who spoke at the same event, stayed for lunch and said afterwards that they were “really interesting people”…). And just this autumn I gave a talk as part of a private online seminar organised by an organisation that promotes ‘classical wisdom’ as the foundation of Western Civilization, where another speaker was from the Ayn Rand Institute, promoter of hard-right libertarian dogma on the other side of the Atlantic.

Okay, two data points in ten years isn’t exactly a pattern, but it undoubtedly sounds the death-knell for any hope of a career in left-wing politics – I guess there’s still the option of getting a life peerage by renewing acquaintance with the ex-Living Marxism crowd – and undercuts any moral authority I might claim to criticise those who have signed up for the Spengler Revival Campaign. But the point of this blog is not to claim ideological purity and denounce others, but to reflect on the situation from my own solipsistic perspective: how does this sort of thing happen, and how do I stop it happening to me again?

Why do we accept invitations to speak? Easy: an over-determined combination of the fact that we are fascinated by our topic and would happily lecture the rest of the train carriage or restaurant about it given half a chance, the importance of such engagements for employment/promotion, the endorphin hit that someone has heard of us and actually wants to hear what we have to say (I can only imagine how much more of an ego boost it is to be given a prize), the imposter syndrome making us think that if we turn this one down there may never be another one.

Okay, why do we accept invitations that might be considered a bit iffy? The obvious answer is: obliviousness – the iffiness may be a matter of opinion or political conviction (is giving talks to fee-paying schools ‘iffy’?), or it may not be completely obvious (I mean, the Institute of Ideas looks like it’s just about people interested in ideas), or we may just not have done any research because it didn’t occur to us that we should (naïveté is a not uncommon academic trait). I’ll be quite honest, with the recent online seminar I was so pleased with myself that I’d asked about the gender balance of speakers before accepting the invitation that it didn’t occur to me to ask any other questions until too late.

And then there is the issue that might, wholly unhelpfully, be characterised as the difficulty of identifying the dividing line between ‘iffy’ and ‘dodgy’, where iffiness might be mitigated by a strong enough imperative but dodginess probably can’t be. In concrete terms: even if one regards giving talks to students in fee-paying schools as a matter of enhancing a pernicious institution without even getting paid for it, this iffiness might still be outweighed by the wish to encourage the study of classical antiquity regardless of the context.

The fact that the study of classical antiquity and its legacy has traditionally been elitist, and carries hefty cultural baggage, means that many of the invitations we receive to speak outside universities are likely to be associated with one or other of these. People who retain an interest in these topics are likely to be convinced of the wonders and continuing relevance of classical culture, because that’s how they feel about it – which means that distinguishing them from people who go on about the wonders and continuing relevance of classical culture as part of a right-wing racist agenda is not completely straightforward.

Yes, when an organisation invites someone from the Ayn Rand Institute to speak (albeit not about Rand but about Greek philosophy), and then responds to pushback with a blog post that suggests Rand was a genius whose ideas need to be taken seriously, then it becomes ever harder to justify associating with them – but I still think it is the case that a profit-making enterprise focused on teaching people about classical antiquity is more or less bound to start talking about the glorious legacy of antiquity, without this being a deliberate right-wing dog whistle (after all, look at how university classics departments continue to market their courses…). Even if this does involve the most remarkable contortions in explaining how my book really supports their agenda.

That’s the closest we got to any idea that my opinions need to be modified to fit with the agenda of the enterprise, and at least they didn’t ask me to do it… But of course that isn’t exactly the point. We do need to consider, in trying to decide whether or not to participate in a given event, that our ideas may be less important than our simple participation. It isn’t that the Institute of Ideas was seeking to recruit me; on the contrary, the basic aim was simply to offer their paying punters a wide range of lectures on different topics, and the possible additional aim – this would be more important, I suspect, if they’d invited me to participate in one of their debates – is precisely to be able to say, Look, we have a range of serious people with different views, this is not a cult or an ideological enterprise but a serious academic debate!

That is to say: we cannot ignore the possibility, however faint, that we are being invited to play the role of the useful idiot – someone whose commitment to the ostensible aims of the enterprise (intellectual exchange and debate) can be used to offer cover for the underlying agenda, not least by making the whole thing appear completely legitimate. To put it bluntly: if an organisation were to hand out awards consistently to racists, islamophobes, right-wing culture warriors and the like, people might start suspecting their good faith; give it to the occasional eminent scholar who cannot be suspected of any such views, and that elevates the whole thing and endorses their claims to be a proper scholarly enterprise.

It’s rarely going to be clear-cut. Most of us academics – by which of course I mean ‘I’ – tend to take people on trust, believe that everyone is involved in honest enquiry, fall instantly for the flattery of simply being noticed, and are far too polite and nervous to cause anyone any trouble by pulling out at a later stage. It is therefore a very good thing that no one is likely to offer me any awards. But I am resolved to be a lot more cautious about accepting invitations in future…

One might, provocatively, suggest that Spengler himself is actually being used in a similar manner by his eponymous Society. Engaging with his ideas offers an opportunity and excuse to talk about the absolute incompatibility of different cultures, the impossibility of cultural influence and mixing, the whole panoply of claims about the decay of Western culture and a whole load of other dog whistles, always with the potential excuse that this is an exercise in the history of ideas rather than the speaker’s own intellectual commitments – analysis not endorsement.

Even more crucially, it represents a cast-iron argument that discussion of such ideas can be easily disassociated from Nazism. Far-right as Spengler was, he didn’t think much of Hitler and his followers (much too proletarian, and too obsessed with race rather than culture). This explains the choice of quotations on the Society’s front page: endorsements of Spengler’s importance from Henry Kissinger (but of course) and Joseph Campbell, wacky mythologist who inspired Star Wars (I assume members of the Society were prominent participants in the storm of criticism of The Last Jedi), and a warning to take Spengler seriously from Theodor Adorno.

There is also – and this is the significant bit – a quote from the author (oddly, described also as a physician, whereas I thought he did that only for a year or so) Friedrich Reck-Malleczewen, who died in Dachau concentration camp (for the crime of “insulting the German currency”, perhaps because he’d complained about the effect of inflation on his royalties) – claiming that no one was hated by the Nazis more than Spengler. Now, that seems prima facie implausible as a claim – but who could gainsay the words of someone whose books were banned by the Nazi regime, and who was eventually executed by them? Clearly ideas like Spengler’s are not a slippery slope towards genocidal authoritarianism, but precisely their opposite! And honouring Spengler’s work is a sign that we are the true anti-Nazis! You should be honoured to be honoured by us…

November 16, 2020

Working in a Coalmine

My email inbox this morning contained one of the oddest invitations I’ve received in a long time – odd, to the degree that I’ve just spent ten minutes trying to check whether it’s actually an elaborate bit of phishing, or a practical joke on the part of whoever suggested my name. The message offers the opportunity to become a Detailed Assessor for the Australian Research Council – to write extensive peer review reports on, say, 5-20 applications per year, term unspecified. This is of the order of being asked to pay £20 to secure my fabulous First Prize of unscheduled pancreas removal.

Invitations to review stuff – research applications, articles, book proposals, tenure and promotion cases etc. – become ever more common once you reach a certain level of seniority and pompousness. Occasionally (mostly, foreign research councils and publishers) they are remunerated; otherwise, one takes such things on, within the constraints of time and energy, as part of a fuzzy sense of professional obligation and doing one’s share of the general effort to keep the discipline on the road. The obvious point is that all of this is on a one-off basis, not an ongoing commitment. The exceptions are one’s own national or supra-national research bodies – AHRC, ERC (at least for the moment…) – where the professional obligation feels greater, not least because one is likely to benefit from the efforts of other peer reviewers.

Well, I’m not Australian, and the chances of my ever applying for Australian research funds seems vanishingly remote, so what gives? I can see the logic from their side: much easier and cheaper if you can recruit a limited number of people who can be given lots of reviews without further negotiation than if you have to recruit new reviewers for every application. But why would anyone sign up to this, absent a sense of patriotic duty? Why would they even imagine that someone would? Is the lure of ticking the ‘international research recognition’ box on the cv really so great?

If that is indeed the case, I have a much better idea. I am delighted to announce the foundation of the ERP (Eurasian Research Partnership) and PRC (Pacific Research Council) – snazzy websites to follow – and for £20 I will send you something to peer review, rigorously, via a simple online tick-box form. Bingo! Achievement unlocked, cv enhanced! We will also be accepting application – 80% fEC – for those of you whose progression and promotion criteria demand the submission of £Xk-worth of research funding attempts, without needing them actually to be awarded – but on the understanding that the success rate is very, very low, which just goes to show how rigorous the peer review process is…

Update: I am rather disappointed to learn that at least one other colleague has received the same Exclusive One Time Only Offer For You Personally, Distinguished Academic! email. I thought I was special…

November 13, 2020

Stupid Boy

Reasons why the department really should be paying the fees for my online jazz composition course, #47… I’ve commented before that we teachers in higher education have to be very, very careful about extrapolating from our own experience as students; leaving aside the extent to which very many things have changed in the decades since we were undergraduates, most of us were extremely atypical, and what suited us may not be remotely useful for the majority of those we are now teaching. My class yesterday evening emphasised the corollary of this: most of us lack any experience whatsoever of something that is absolutely central to the difficulties experienced by the students who need help and support the most: the feeling of being completely crap and useless.

It’s not that we have always been wonderful at everything, but at a guess the failures were a long time ago, we dropped those subjects at the earliest possible opportunity, and probably in most cases the psychological trauma was created by being unexpectedly average rather than actually rubbish – having to accept the superiority of some other people, not of the entire class. But take the memory of that failure, ditch the usual “oh I was always rubbish at maths/science/woodwork” deflection and imagine that this is happening in a subject you have chosen and really want to do well in; not imposter syndrome, but clear proof that you don’t belong, and not for a high-powered academic career but for being at university at all.

My experience yesterday was utterly trivial in comparison – this is just a hobby, with nothing at stake for my future prospects – but still a glimpse into what it must be like for some of our students. Look, I know my homework exercise is hopeless, so can’t we just skip it – give me a zero and move on, rather than discussing it in class? We’re out of time, we’ve made it to the end before my turn came up, I’ve got away with it… and the tutor decides to carry on until he’s dealt with everyone. (Bloody Zoom; couldn’t do that in a normal class with the next lot of people waiting to use the room… and I hope his partner gave him MASSIVE grief for being late for dinner…). I seriously started thinking about staging a broadband problem, or just quietly logging out.

I should stress that I can’t fault the tutor for any of this. The feedback process might well have been less painful if I hadn’t been able to see exactly what he was doing, because it’s exactly what I would be doing myself: the ‘feedback sandwich’, finding vaguely positive things to say as a sugar coating for the devastating bits; trying to put the devastating bits in a constructive forward-looking form; phrasing the same point in several different ways; giving lots of practical advice about how to fix things or do them differently rather than just making abstract comments AND NONE OF THIS HELPS because I know it’s rubbish, I see through all the transparent attempts at making me feel better, and the practical advice is useless because I don’t want to try and improve this mess, I want to forget all about it and start again from scratch in the hope it will be better next time…

I know in theory why the students who most need to talk through the feedback on their work are the ones least likely to take up opportunities to do this; I haven’t felt it before. Maybe the strategies are less obvious and so more effective with students who don’t do feedback professionally – but it’s not just about rational calculation, it’s about the emotions, and I now completely get the sense that, yes, I could learn something from this process, but it’s not enough to outweigh the misery involved in getting there.

Okay, so what does work? At this point we’re back at the issue that I am unlikely to be typical – and in particular, that I have already learnt how to learn (and so a major issue with the jazz is that I simply can’t spare the time to put in serious work getting to grips with this stuff, which is what I would be doing if it actually mattered). Feedback is one of the ways we try to teach students how to learn and improve their work, so what do we do when the feedback process is part of the problem?

This is all very provisional, therefore, but for a start: worked examples. Seeing someone else’s homework being examined can be really helpful – no, not the guy who took the instruction ‘write a tune based on a mode’ as the basis for an elaborate multi-part exploration of an Abyssinian scale in 9/4 with percussion and string section*, but something a little more normal (in 3/4, say. Was I the only person who stuck to 4/4? I am just so square…). Even better: worked examples of real actual publications – but ideally ones where the gap between them and what students might imagine themselves capable of isn’t too great. Yes, we can analyse some horribly complex bit of Kenny Wheeler or John Henderson to work out what’s going on, and that has its uses – but it’s not going to help anyone with their own writing until they’re at a very advanced level.

The other thing that comes immediately to mind is privacy; I would certainly have been less uncomfortable having my composition taken apart if it were not happening in front of the rest of the group. Yes, I can see how it could be useful to them, precisely because my approach was relatively unambitious and so the lessons of its flaws more widely applicable, where issues with a piece based on a John Zorn scale in 5/4 might be sui generis and/or simply attributed to over-ambition. But it’s not fair to me… Okay, problem in getting students to engage with personal debriefing sessions, as noted above, and time implications if they all suddenly decided to – but THE thing we have to avoid is public humiliation. Yes, it is a spur to try to do less badly for next time, but I can see how it could easily become a reason not to go back…

* Some interesting lessons about class dynamics, and the roles adopted by different students, too. I sincerely hope I was never ‘that guy’, even in classes when I knew what I was talking about. In this one, I think I’m rapidly turning into a cross between the class clown and the one who asks questions that are transparently intended to divert the conversation. Still it is not bad acktually as during a bit of parsing or drawing a map of Spane you can just look up and sa. ‘Did you hav a tomy gun during the war sir?’…

November 11, 2020

Week 10 is the New Week 12

I for one am overjoyed at the announcement of the government’s cunning plan for getting students home for Christmas, as it solves at a stroke the knotty problem of what to do with my Thucydides class in the final week of term. It’s always been the case that student attention tends to be lagging by then, and attendance dropping (especially for classes later in the week, as most of them disappear off home), which then creates the dilemma of whether to plough on with material regardless for the few who do turn up, having then to repeat it all at the beginning of next term, or just have an informal chat and knock off early, which then seems like short-changing the few who do bother to turn up. My solution in recent years has been a session on ‘Thucydidean Games’, not essential for the core elements of the module but containing potential both for serious analysis and for just playing some games, depending on the general mood.

As it’s become increasingly obvious that messing about with scores of pieces and cards, clustered around a board, is a sure-fire way to break at least half of the university’s COVID-security rules, I’ve been wondering what on earth to do instead. I need worry no more! Week 12 will clearly be a write-off, as effectively it becomes the first week of the Christmas holidays; week 11 will probably be disrupted by everyone packing up and travelling home. So all I need to do is cram all the scheduled material into Week 10, and save the following fortnight for any especially keen student who wants to talk about their assessments or dissertation…

Because obviously what I want to do at this stage of term is reorganise reorganise all my modules because the government has randomly decided, in its obsessive pursuit of insisting that universities must continue as normal during the November lockdown but must then get students home in a way that government can’t be blamed if it goes wrong, that all teaching should switch online at a date that disrupts the last couple of weeks of term for the majority of universities but just happens to come after teaching has finished in two of them. This, I’m sure, is coincidental. It is not that there won’t also be disruption in Oxford and Cambridge in implementing the latest decrees, but it is nevertheless striking that they are not being told to change their teaching delivery or to cope with the possibility of students disengaging and/or having complaints about the change.

Why couldn’t this year’s higher education re-enactment of the Fall of Saigon be staggered, so different universities organise the departure of their students according to their existing term dates and teaching arrangements? This would surely be preferable to having everyone trying to evacuate at once, after all. To be honest, the only explanation that presently comes to mind is that they just want to get it over with, not with any notion that it’s preferable to manage it like this, but to limit the number of days this story might feature in the newspapers. Get them all home, and with a bit of luck any ensuing plague-spreading will be buried in the general noise.

One of the things that most strikes me in this whole mess is that a government with a dedicated Behavioural Insights unit seems to be remarkably clueless about human behaviour. This is especially the case when it comes to students, who are, apparently randomly, perceived in three different but equally problematic ways: (1) hard-headed consumers focused solely on the economic value of their degree; (2) irresponsible delinquents; (3) malleable children who will do exactly as they’re told.

None of these reflects the reality that students are entirely rational adults but with a much wider and more complex range of motivations; it’s scarcely surprising that policies based on these assumptions tend to run into problems, and still more when they hop from one to another according to which suits their other purposes. Such as responding to a perception of (2) by building a fence, a policy which was always doomed unless students were actually (3), or assuming you can address anxieties about (1) and demands for fee refunds by switching to (3). (Almost the only positive aspect of the pandemic from an HE perspective has been the rapid abandonment of all the student-consumer-choice rhetoric – except that it’s been replaced by even stupider ideas, and has of course only disappeared temporarily for as long as the government finds it threatening).

What this does mean is that the last proper, non-disrupted class this term will, fittingly, be on The Plague…

November 3, 2020

I Was Wrong

I was wrong – about so many things (thank you, the anonymous gentleman at the back), but I’m thinking specifically of developments in higher education this autumn. I really thought, after my scheduled face-to-face-in-person seminar was switched online for the first two weeks of term as part of a ‘staggered return to campus’, that I wouldn’t be back in Exeter until 2021. And I certainly imagined, as the case numbers rose (nationally and on campus), that we’d be online by now – officially, I mean, rather than the de facto situation whereby the combination of students isolating and students voting with their feet leaves me talking to one or two masked students in a room and simultaneously trying to engage with the larger numbers on the screen.

However, there are degrees of culpability. I don’t feel that I over-estimated the likely spread of infection among the student population, or the probability of a second wave in the autumn. Given that I was asked if, hypothetically, I would want to go completely online and said no – thinking at that point that the majority of students would prefer some face-to-face – I don’t think I can be accused of being someone willing to sacrifice young people’s educational prospects in my eagerness to shirk my duties ((c) the ex-RCP crowd).

No, the basic flaw in my reasoning, I think – confirmed by the letter from the Universities Minister this morning, setting out government expectations about higher education under the new lockdown – was underestimating the fetishisation of face-to-face learning amongst those in power. It is asserted – with no visible evidence – that a switch to fully online teaching would jeopardise student learning and damage their mental health and well-being. So, universities must remain open (as if they were ever closed…), teaching must retain significant elements of face-to-face, standards must be maintained OR ELSE, and students must be kept on campus until someone comes up with a cunning plan for December, whether they like it or not.

My best guess is that this is a combination of dogma – online learning is by definition inferior, we never studied like that, it’s for OU type people rather than ‘normal’ students etc. – and fear that the more deviation there is from ‘normal’ provision, even on the grounds of quality, the more likely it is that students will demand refunds, universities will fall into financial black holes, and government will have to bail them out. It’s virtually cargo cult thinking: quality will be magically ensured by repeating the traditional rituals regardless of changing circumstances, whereas doing anything different, even if a rational case can be made that it would be better, jeopardises everything. It reveals the utter vacuousness of their conception of ‘quality’ – but actually they probably haven’t even thought it through that much; rather, exactly as with the hopeless plans for managing A-levels this summer, they just insist on inertia for inertia’s sake.

I do think that a seminar of people wearing masks and seated 2 metres apart, all facing forwards rather than being able to interact with one another, could have been made to work, and might indeed have given students a positive experience of talking to other people. There is no doubt that it would be significantly inferior to a seminar in normal circumstances, and the jury is out as to whether it would really be better than a proper online seminar where at least everyone can see each other.

But the crucial point is this: in retrospect it’s clear that such a scenario was never on offer. It was never going to be a choice between face-to-face seminar with social distancing and online seminar, but between fully online seminar and the current awkward bodge in which I try to engage with students via two media at once, having to improvise most of the technology myself. As I may have mentioned in a previous post, if it were just one or two students listening in online, I could concentrate my attention on the people in the room with a clear conscience, leaving online people to chip in if they wanted to. But when there are one or two people in the room with everyone else online, where am I actually supposed to focus? No one is getting my proper attention, and my ability to draw people into the discussion is effectively nil.

As I’ve mentioned before, in normal times teaching gives me energy and self-confidence that then feeds into research and general sense of self. It’s now the opposite, as I struggle to think how to prepare for sessions without any idea of what the circumstances will be, and every class leaves me tired and demoralised and full of anxiety and a sense of failure. It’s got to the point where – given that encouraging the remaining students to shift online will presumably bring down disciplinary charges – the least worst option seems to be to offer an extra hour per week just for online people, reserving the face-to-face session for anyone who actually turns up – which is pretty pointless, as there will then be no serious group discussion, but it can’t be as bad as me trying to talk to room and laptop simultaneously.

It’s not that online teaching is perfect and wonderful – yesterday also brought the unedifying experience of putting students in a Zoom session into breakout groups and immediately seeing several of them log out altogether. I honestly do not understand that – I’m more ready to cut some slack to those who didn’t turn up at all – but I am conscious that they must all be tired and anxious and probably miserable. We just have to get through this the best we can – working around external constraints as flexibly and humanely as possible…

October 26, 2020

Nothing But Flowers

It’s Reading Week – or, as various people have sagely commented on the Twitter, At Last I Can Catch Up On Sleep Get Ahead With My Teaching Prep Write Those Reviews Comment On Postgrad Drafts Spend Some Time With Family Do A Bit Of Reading Finally Get Some Research Done Hey Where Did That Go Week. And that’s in a normal year. This autumn, I imagine I’m not the only person who has found the switch to online teaching and the constant worrying about students thoroughly draining, absorbing every minute of the working day and disturbing every night – with the result that I both need to sleep for a week and have a list of overdue commitments that is at least twice as long as usual.

I seem to have spent much of this year reassuring myself, or demanding reassurance from others, that at some point I will start feeling like myself again; capable of sustaining ideas beyond ten minutes or so, able to manage several different things at once, having a degree of confidence in what comes out of my mouth. With the teaching, I think it’s starting to get there, as I get used to the technology (and get into the swing of adapting my technique every bloody week as the proportion of in-person and online students shifts) – though it remains difficult not getting any sense of how things are going from the faceless blobs on Zoom or the masked people in the room (when there are any); talking into the unresponsive void, all too often I feel that my words are becoming hollow and aimless, and everyone has actually switched off and gone to do something more interesting and useful. But it’s a lot better than it was at the start of term.

With research, I think things may actually be getting worse. Partly, this is a function of the fact that the ‘to do’ list gets no shorter but more and more of the things on it become due or overdue, hence suppressed panic. Partly, the external context feels increasingly overwhelming; it’s not just that things keep getting published that I have no time and energy to read, but that innumerable seminars and conferences, which in the past I would have happily ignored if I knew about them at all, are now all online, and some bit of my psyche clearly feels I ought to be viewing them and stokes the guilt that I simply can’t face it – what, you think you’re too grand to pay attention to what young researchers in Italy or Newcastle or China are doing? Shame!

And partly my generally terrible research/writing practices – an excessive reliance on ‘feeling in the mood’, which requires a couple of clear days of faffing about before inspiration starts to stir, until I get into the final quarter of a project when suddenly I can engage with it in odd hours – are even less suited to pandemic conditions than they are to normal academic life. And my fragile-at-the-best-of-times self-belief is definitely missing the regular confidence boost of a successful class as a reminder that, yes, I can occasionally articulate ideas in a coherent manner.

As I keep asking myself, is this the new normal? I can’t get used to this lifestyle… Obviously I’m not the only person to be having such reflections, though others seem to be a bit less morbid about it. In the spirit of assuming that current developments support one’s prior commitments, people who have been arguing for ‘slow scholarship’ as an alternative to the relentless pursuit of mounds of hasty publications and grant applications have claimed the pandemic as clinching proof that we do need a new approach. On the contrary, someone else argued earlier this month in a piece that I now cannot find, what we actually need is fast scholarship, as we all have much less time than we did, and resources are likely to be stretched in future, so we need to do more with less.

As I remarked at the time, what we really need is short scholarship. As Buffy remarked of a course on ‘Introduction to the Modern Novel’, “I guess that means I’d have to read the modern novel? Isn’t there an introduction to the Modern Blurb?” So, articles of no more than 5,000 words, fewer books, more focused arguments, and greater validation for the medium of blog posts. And tweets. And why can’t all these proliferating online workshops be done as recorded presentations with asynchronous discussion boards, rather than implicitly demanding that we all organise our lives around them? But above all, surely this is the cue for the triumphant return of the short but engaging essay as the key form of scholarly publication?

Well, apparently not; just at the moment when it might have established its status as timely and indispensable beyond any dispute, Eidolon has announced that it’s shutting up shop. I am still deeply pissed off about this – and one of the reasons is the sense that I’m not allowed to be. Of course I’m enormously grateful to Donna Zuckerberg for having put her energy, creativity and other resources into creating and sustaining Eidolon, and of course there is no suggestion that she should continue whether she likes it or not, regardless of cost, because the rest of us demand it, or because of a claim that we need this journal.

But the idea that, because Donna doesn’t want to continue, Eidolon must cease to be strikes me as entirely wrong; it suggests that it was never anything more than her pet project, the academic equivalent of an eighteenth-century enlightened monarch patronising some philosophers and musicians for as long as it amuses them. I don’t think that’s what she ever had in mind – and I don’t think it’s what occurred; on the contrary, by creating this space, Donna fostered the emergence of a distinctive style of scholarly writing and engagement, a loose community of like-minded people, that transcended her example or influence. Yes, an Eidolon under someone else’s leadership might well change in the course of time; isn’t that better than leaving it as no more than a museum piece to be reduced in due course to being seen as a mere reflection of its cultural context?

As Donna’s short essay suggests, we might hope for the emergence of new publications to fill the gap. But they are going to have to start from scratch in building an audience and a reputation – and will face a peculiar double-bind in trying to negotiate their relationship with Eidolon, balancing claims to continuity with assertions of change for fear of being dismissed as a pale, derivative epigone (yes, a post-Zuckerberg Eidolon might have faced similar accusations, but to a greatly reduced degree).

Well, assuming that the need for short, engaging, polemical, well-written, serious yet fun essays about the relationship between classical antiquity and the present isn’t likely to evaporate any time soon – still more in the era of pandemic – then somehow this will have to happen. Anyone out there got any energy?

Neville Morley's Blog

- Neville Morley's profile

- 9 followers