Neville Morley's Blog, page 24

February 21, 2021

Remember (Walking on the Strand)

A year ago, I was in London, coming to the end of an intensive week of workshops and rehearsals with the amazing group of actors and creative people with whom I was exploring the dramatic potential of Thucydides’ Melian Dialogue. Yes, long days with a bunch of people from different households in a room with the windows shut because the weather was so awful; lots of warm-up exercises with us all in a tight circle breathing at one another; breakfast and lunch in crowded cafes; evenings in restaurants, either solo or meeting friends. All leading up to a gathering on the final day of seventy or so people in a small theatre for the 45-minute performance and subsequent panel discussion. Another time, another country…

It was a strange experience this week, having to cast my mind back to that week in order to compose an interim report on the ResearchFish system – what was it that I thought it was all about? It’s just a provisional report – second phase of the project was dramatically delayed by the pandemic, and is now being developed as an online thing – so no need for lots of serious recollection; at some point I am going to have to revisit my detailed notes of the experience, and hope that I can somehow recover the feelings and ideas and energy of that week. What scares me is that I might not be able to.

This isn’t a problem with the duty of reporting results to the research funder, not really – I’m confident we will have done everything promised, and I can describe it all in the appropriate language. Rather, the problem is that I want to be that person again – energised, inspired, full of ideas for doing unusual and creative things and for new research projects and arguments – and I fear that it will never happen. I’m still not properly myself, ten months on from contracting a relatively mild and certainly non-life-threatening version of the plague; I hang onto the fact that I’m definitely better than I was in the autumn (when I had to try to get back to proper full-time work, with the teaching if not the writing, after taking things very easy over the summer), but there’s clearly something stuck in my system that breaks out whenever I get slightly tired or stressed, and brings back the brain fog, the sore throat, the headaches and the swollen glands. It is particularly unfortunate that this tends to be associated with my halting attempts at catching up with the various things I’m supposed to have written…

To be honest, this solipsism is what I mainly associate with the idea of a return to some sort of normality. Yes, it would be wonderful to engage with students face-to-face once again, but I don’t particularly miss shopping or pubs or dining out. In lots of ways, lockdown has been great, as I have exactly the sorts of privilege that make it bearable: decent-sized garden that has for the first time ever been properly under control (and we’re still eating home-grown veg), plenty of solitary hobbies and experience in homecraft, interest in wildlife and enough surplus income to buy a bat detector. And any ‘new normal’ will need to include more of this stuff than before the pandemic; gardening, brewing, jazz composition, just spending time at home.

And maybe this would be the healthiest option; not retirement, but a less obsessive dedication to academic and intellectual life, and a bit more balance, with the prospect of less frustration and thwarted ambition as a bonus. But I can’t quite forget last year’s intimation of a future path, a future self; not that I had infinite energy and capacity then (deranged insomniac cat was already being deranged and insomniac, and depression and lassitude are my life’s companions), but it seemed possible then to imagine hacking my way through the ‘to do’ list in six months and finding a new balance on the other side. Well, a lot of us had plans. George Zipp had plans.

(I was prompted to write this by the post by the ever-wonderful Maria Farrell over at Crooked Timber, but since her piece is vastly better than mine, as well as being a lot more positive and content, I’m putting the link down here at the bottom).

February 15, 2021

Have A Cigar

You’re going to go far? Well, no. I have long since resigned myself to the fact that I am not suddenly going to embark on the sort of media career that allows one to produce a calendar of swimsuit shots in exotic filming locations or be interviewed for a weekend supplement about my favourite recipes or (sob) get invited onto Strictly Come Dancing or Desert Island Discs. Am an attendant lord, fit to sneak onto the occasional In Our Time when everyone else is busy.

But I remain wholly susceptible to the thought that someone in the Real World has actually noticed me, and that I might get to do something that friends and relatives might stumble across, and so I am a very easy mark for anyone wanting some free research. In fact, my willingness to ramble on about different aspects of ancient history at the drop of a hat is an even bigger weakness; I’ve just recalled that I spent half an hour last week writing a reply to a random stranger who’d sent me an email with some questions about Pericles. A production company wouldn’t need to dangle the carrot of a brief screen appearance with their celebrity presenter, they’d just have to pose as an ordinary person and express an interest in my thoughts. Because if they do mention that they’re a production company, I have now taken on board the need to insist on proper remuneration for providing expertise, less for my own sake than for the sake of those who need to make a living out of this. However much it makes me deeply uncomfortable having to broach the subject of money.

And I am very glad that I did – yes, let this be a lesson to me – because I’ve now had an email to say that the interview I recorded last year will not be used after all. If I had taken half a day to travel to the location, having previously spent time talking, exchanging emails and doing some extra research, without any sort of fee, and then been cut, I’d be deeply pissed off.

As it is, I’m simply miffed – and busy speculating about an explanation that is less depressing than “you’re ugly and tedious”. The stated reason was that they “simply have too much great material”. Not impossible, but a little odd; one assumes that they asked me questions that needed answering for the purposes of the programme, so did they ask someone else the same questions and go with whoever was more decorative?

Or, whoever gave them the answers they wanted – the topic was the life of an enslaved woman under the Roman Empire, and I was determined not to let them sugar-coat it. I mean, they didn’t tell me not to talk about sexual exploitation and the threat of violence… But perhaps they then decided to get someone to offer a less negative view – or, they’ve given all the material they got from me to the presenter, so they can pretty it up a bit without having to worry about awkward academics. Or, they’ve decided that this is too much of a minefield, and will be focusing on the more cheerful aspects of Roman imperialism…

Which would be a shame, as I really could see the potential in their idea, if done properly. True, there is (and was at the time) the fear that they could have edited my contribution so as to appear to support a version of Roman enslavement that would have called down a storm of condemnation. But, hey, getting cancelled by a bunch of woke SJWs seems to be the only route left to me for a career as a public intellectual, so it could still have been my break-out moment…

February 11, 2021

Western Death Cult

The discipline of Classics considered as an episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

The Institute of Ancient Wisdom, one of the oldest and most prestigious organisations in Sunnydale, comes to the school to deliver some curriculum enhancement activities and recruit new members. Willow is entranced by their erudition and sophistication, and the promise of, well, ancient wisdom. Cordelia is attracted by the aura of power and social status. Xander is suspicious and hostile at first, but then they explain that he too is an inheritor of their great traditions, simply by virtue of being himself, and so he should help defend them.

Only Buffy feels that the whole thing is a bit elitist, and rather too keen on metaphors of purity and light, and generally icky. Giles remarks that Americans always obsess about this, and it’s just a function of being such a young country; everyone else assumes she’s simply looking for attention.

Further investigation reveals that, behind its energetic programme of school outreach and earnest scholarly debates and advising the Mayor on architecture, the Institute is indeed involved in mystic activities – but apparently on the side of good, as it draws on Ancient Wisdom to combat the forces of darkness. And yet some of its members appear to be vampires and demons, using Ancient Wisdom to ensnare the innocent.

Xander gets a tattoo with incomprehensible writing, and talks a lot about Sparta.

Cordelia ends up in a perilous yet also humiliating situation; it’s unclear whether this is a sophisticated commentary on genre tropes or gratuitous cruelty from the writer/director.

After extensive archival research, Giles stumbles across the terrifying, hitherto unsuspected truth that the Ancients were slave-owning imperialist bastards. The whole thing about civilisation and enlightenment is a lie!

Breaking into the Institute’s headquarters – because of course they do – the true situation becomes apparent: virtually all the members are entirely sincere, but they have been infected by an Ancient spirit that is completely indifferent to good or evil but simply seeks to survive and replicate by tempting people with genuine insights and the endorphin rush of superiority.

Can its influence be managed or diluted by expanding and diversifying the membership, and by rooting out those who use its power for evil? Or does the combination of brilliance, utter self-interest and toxic behaviour permeate the whole enterprise so much that it devalues everything it touches, and needs to be burnt to the ground? Is Xander’s tattoo just silly, or a harbinger of disaster..?

February 6, 2021

Village Green Preservation Society

I suspect that for a lot of people the joy of the Handforth Parish Council Planning & Environment Committee Zoom meeting (video here, if somehow you haven’t already seen it), besides the entertaining spectacle of chaos and surrealism, is the discovery of a bizarre, alien world where the question of whether someone is a Proper Officer or who actually has The Authority In This Meeting is a matter of high political drama. For me, it was a nostalgia trip. I should stress that Castle Cary Town Council was never anything like this bad, even at its worst moments, but it’s easy to see the potential that existed for such a breakdown, and there are other councils in this area whose Zoom meetings would probably be equally comedy gold. And, given that the video leaves out a significant amount of context, it was great fun to revive my once intensive knowledge of local government procedures and standing orders, to work out what must be going on and who actually did have the Authority, if not Jackie Weaver…

The answer? Sue Moore, by virtue of being Vice-Chair of the Committee, once the Chair of the Committee, Brian Tolver, had declined to take on the role on the grounds that the meeting was illegal. It is the one major flaw in the otherwise excellent discussion of this case on David Allen Green’s Law & Policy blog that he suggests Tolver was offered the role of chair for the meeting by virtue of being the Chair of the Parish Council, whereas it’s clear from the agenda and other papers that he was the Chair of the committee – whether or not ex officio as Chair of the Council isn’t clear, and wouldn’t make a difference to this being a distinct role – and so would normally chair meetings. It’s clear that Tolver had not called a meeting for many months (which would have left him in the position of making many decisions by chair’s action; one might speculate that this could be significant…); two councillors had written to ask him to call a meeting, which is usually a procedure for an emergency meeting in addition to scheduled meetings, but works equally well when scheduled meetings have not been scheduled; after his refusal or failure to do this (not clear which; doesn’t matter), it was then not only perfectly legal but a statutory requirement for a meeting to be called anyway. Absent the regular Chair, the Vice-Chair takes over (and the Vice-Chair of the committee, not the Vice-Chair of the Council, whatever he might claim). Absent the Vice-Chair (or if they decline), the committee can vote to appoint another of its members to take on the role for that meeting.

One of the fun things about local government is that there is always an answer to this sort of question. It is not the case that every councillor should always know the answer (I’m slightly weird, both in being a natural bureaucrat and in having been for a while Chair of the HR committee, hence responsible for inducting new councillors into the basics of council workings). Rather, every council has a professional, qualified Clerk, whose role includes knowing the rules and advising the council on proper procedure, the legality of its actions and so forth. And if there are issues with this, or a problem seems especially knotty, then it’s possible to solicit advice from the county Local Government Association (which is where Jackie Weaver comes in, serving as clerk to this particular meeting – not to the whole council, and certainly not taking on the role of Proper Officer).

But the Handforth kerfuffle illustrates perfectly a couple of reasons why this doesn’t necessarily work. Firstly, the complexity of the rules and standing orders creates enormous opportunity for the barrack-room lawyer type, able to cite terminology and paragraph numbers in his (of course it’s almost always ‘his’) own interests with an air of confidence and authority. The fact Tolver didn’t want a meeting to take place doesn’t make it illegal, nor was he entitled to declare himself Clerk (putting it as his Zoom identity doesn’t make it so), nor was the fact Jackie Weaver was not the council’s Proper Officer make the slightest difference, and in the face of actual authoritative knowledge (i.e. Jackie Weaver’s) this all falls apart – but it is easy to see how ordinary councillors with a fuzzier sense of the detail might be brow-beaten into submission, let alone members of the public.

Secondly, the rules are insufficient to ensure effective operations; what this episode shows, at least as well if not better than the ongoing problems in the government of the United States, is the role of unwritten norms, and the consequences once they start being flouted. This layer of local government works on the assumption that everyone involved is basically public-spirited, volunteering their time and energy (the demands on which can be considerable) for the good of the community. Of course there will be different views on what would be best for the community – just as there will always be grey areas where a councillor might seem to have personal interests even if they do not clearly fall into the category of the sort of interests that must be declared and which rule you out of relevant discussions and decisions. And the way these are dealt with is that everyone goes out of their way to acknowledge that other opinions are valid, and to assume good faith, and to raise their own possible conflicts of interest even if manifestly over-cautious, and to be civil to one another.

Some – the council on which I once served – go further, with an unwritten rule that no one has a party affiliation and that overt party politics are kept out of everything. This can work in a small community where people know each other rather than relying on party affiliation to decide whom to vote for – and still more when most if not all councillors have to be co-opted because there are never enough candidates for an election. It can indeed be helpful in smoothing relations with representatives of higher levels of local government – county councillors, and in our area also district councillors – who are normally elected on a party platform, that may be quite different from the dominant local tendency. Of course we all know that most of us have Views, but those are for the pub afterwards (yes, this is a very blokey world, still), not for council meetings.

One thing to be said in favour of allowing party affiliations is that, at least in theory, individuals are then subject to some sort of external discipline; independents, notional or actual, are a law unto themselves. Which is fine, so long as they play by the unwritten rules. Once someone starts insisting loudly on the letter of the law, or openly questioning the good faith of others, or overtly abandoning any attempt at finding compromise positions, or even just ignoring the basics of courtesy, you have a problem. Of course there are disciplinary measures that can be invoked, but that’s a sign that things have already failed, and generally just make things worse. Either the whole council (or at least its dominant figures) abandon the behavioural norms and start quoting statute and trying to manipulate the rules or just yelling at one another, or the majority carry on trying to manage business as normal but are constantly derailed. There is tremendous power, at least for disruption, in being someone who ignores expectations when everyone else is sticking to them.

At this point, some academic readers may be reminded of department meetings, where a similar dynamic can sometimes play out if one colleague is happy to push the boundaries of collegial discourse – worse, arguably, in the absence of any sort of rulebook for the conduct of meetings or of an equivalent of the professional Clerk, so the only option is the invocation of higher layers of management and disciplinary proceedings which no one wants to do (members of a local council calling in the Monitoring Officer may be embarrassing, but since everyone is an unpaid volunteer the range of actual consequences is very limited).

Of course there’s a flip side to all this stuff about unwritten norms, deliberate politeness and collegiality: the way in which they can be used to silence or marginalise minority voices, and ignore inconvenient arguments on the grounds that they haven’t been expressed appropriately, ignoring their merits. Local councils can be stultifyingly conformist and sexist, and their dependence on unpaid volunteers means they are often thoroughly unrepresentative of their whole communities, but convinced that they speak for the (right sort of) people. And they can be extremely resentful of anyone questioning their self-image – because after all they are giving up their spare time for this.

But there are three obvious advantages over similar situations in the academic department. Firstly, it is only a part of anyone’s existence, rather than their whole professional life, and you can always walk away. Secondly, there are rules about the conduct of business, with the Clerk obliged to enforce these even if, hypothetically, he might sympathise with the small-c-conservative wing – and these rules can be used to stymie any tendency to agree things down the pub outside of regular meetings. Thirdly, this is politics: if your position is genuinely marginal and unpopular, then you shouldn’t get to impose it on the community anyway – but if it isn’t, then you just need to recruit allies, build a platform and work to change the composition of the council, which is not something you get to do with your department…

Tl;dr: maybe I need to jack in this academic malarkey and train as a town clerk…

January 24, 2021

Near The End

Thinking that we’re getting older and wiser, when we’re just getting old…

There’s a painful scene towards the end of season 1 of Shtisel (and if you don’t already know this series, I recommend it highly: engrossing low-key family drama with a side order of comparative religion and anthropology). Shulem, the Shtisel patriarch, has been puzzled that his monthly pay as a teacher in the local cheder is substantially lower than normal. Initially the principal tells him that there’s a general cash-flow issue, but when he realises that he’s the only one affected the truth comes out: this is actually his pension; he was officially retired at the age of sixty, and since then the money to make up the difference to his old salary has been coming from his mother, as his wife was so worried that stopping work would kill him within a few months.

Well. Quite apart from the logistics and paperwork, I don’t think it’s very likely that any of my family would hatch such a plan, and I don’t think it would be necessary – with the gardening and brewing and music and sausage-making, and maybe even finally getting round to the novel, I’ll have plenty to keep me occupied. But I can imagine how much of a wrench it will be, finally to stop teaching and lose the adrenalin rush of engaging with young people (even in online conditions, it remains a a thrill and a privilege). And still more I can imagine the feeling of being suddenly confronted with the reality of being too old, irrelevant, redundant.

And so you should! heckles the imaginary voice from the gallery. You may have been the future once – a rather peculiar, borderline dystopian future – but it’s time for a new generation, old man! Stop trying to be down with the twenty- and thirty-somethings, and just shuffle off into the twilight!

Yes, well. Having spent much of the last nine months wondering if my brain would ever work properly again, struggling through the after-effects of the virus on top of a longer-standing tiredness, it’s unfortunate that, just when I’m feeling a bit more on top of things and have actually caught up with some my very long ‘to do’ list, circumstances conspire to raise the same questions from a different direction. Perhaps as a result of the sudden hole that’s opened up in university budgets – extended lockdown, rent refunds, government merrily throwing universities under the bus – there are suddenly plans for job cuts at multiple places, and lots of rumours elsewhere. This is almost never good for the humanities. And so, alongside my own self-doubt, I find myself wondering how far I might seem to others to be past my prime, not as good as I used to be, ripe for down-sizing instead of someone with more productive years left in them.

This overlaps with a broader, perhaps more existential, question, as to whether the discipline to which I have more or less committed myself over the last few decades is in a similar state: no longer fit for today’s world, getting by on past achievements and status, and – as I might as well go the whole hog in imagining classical studies as a reflection of myself, and vice versa – tempting fate by developing a searching self-critique. This was a thought prompted by current developments at the University of Leicester, where the pre- and early modern sections of the English department are threatened with radical cuts, in the name of a more diverse and relevant curriculum – despite the fact that medieval studies, as a field, has been notably active in addressing problematic aspects of its traditions, assumptions and what the far right does with some of its material. Or maybe ‘despite’ isn’t the right word; maybe someone has picked up on these debates, and concluded that the field is too problematic to survive.

This is the problem with critiques of Classics that, however rhetorically and however understandably, take the position of “Burn it down!” There are people – which is to say, university management – who may be all too happy to, and not in the sense of investing in the range of new posts required to develop an alternative field of Ancient Studies or Global Antiquity. We can happily imagine alternative configurations of subject areas, exciting new multi-disciplinary enterprises that expand the horizons of our activities and set up lots of productive new conversations – but we’re more likely to find ourselves in the situation of ‘sauve qui peut’, in which a capacity to expand teaching and research beyond the traditional focus on Greece and Rome becomes a requisite for continued employment in a diminished department rather than an argument for expansion in visionary directions.

And it’s easy to see, both in some of the responses to Sarah Bond’s Twitter thread on this issue and in the fall-out to the Leicester announcement, how this might develop further: a doubling-down on the very claims that made these disciplines problematic in the first place. How dare anyone suggest dismantling the study of the very foundations of Western Civilisation? It’s a clear sign of the bankrupt wokeness of the modern university that it dares attack such eternal values! Etc. And, while I doubt that most classicists have much sympathy with the sorts of commentators who trot out the whole “why can’t we celebrate Our Culture without people going on about slavery and racism?” brigade, would they reject them as potential allies if it came down to saving some jobs?

The deferment of disciplinary retirement on the basis of cheques drawn on someone else’s account, for the wrong reasons…

January 9, 2021

Power to the People?

Over the last couple of months, one Thucydides quote has been quite widely circulated on the Twitter: “In a democracy, someone who fails to get elected to office can always console himself with the thought that there was something not quite fair about it.” As I discussed a few years ago, it’s a genuine quote (from 8.89) albeit a pretty loose translation (by Rex Warner) – and since that discussion was in October 2016, I’m guessing that this appears on various websites listing Quotes on Democracy, which the sorts of people who like tweeting quotations refer to every four years. While many of the tweets are completely without context, however, enough of them appear in discussion threads that you can make a pretty good guess at their intended meaning, and what’s interesting is that there are two diametrically opposed uses: on the one hand, there those who (as was the case in 2016) offer this as evidence that sore losers are always going to claim they were cheated, but on the other hand this time around there are significant numbers – probably a majority – who put this line forward in support of the claim that there is going to be something unfair about a vote in a democracy, that ‘they’ are always going to cheat and manipulate the system.

Heads Thucydides is always right, tails current events once again confirm the eternal relevance of Thucydides. If you assume an insightful, illusionless authority figure, you can equally well imagine him having a clear-eyed view of politicians and of political systems. What most struck me this time around was the way that the quote actually encapsulates fundamental differences between ancient and modern democracy. Firstly, there’s the nature of the office for which an election is being held – never, in Athens, supreme executive power, but either a one-year role as one of the generals, or a largely honorific position as one of the magistrates; real power remained in the hands of the demos, and those who actually wanted to shape decisions and events, rather than simply enjoy a boost in status, had to persuade the assembly time after time to keep following their leadership. This could, as Thucydides’ account shows, result in abrupt changes of political direction, and the fact that the demos was prone to changing its mind was one of the main planks of the oligarchic critique of democracy. But it meant that no one was given several years’ worth of free hand in power – and, conversely, that every voting setback might be only temporary.

Secondly, there’s the nature of the relationship between the candidates and the electorate (anachronistic terms in relation to Athens, but you know what I mean). The Athenian demos got to choose between a selection of members of the elite who made no pretence about their different status, and who might indeed emphasise rather than try to disguise it (as Josh Ober pointed out), presumably because it’s a key part of their claim to be qualified for a generalship or magistracy. If we take the perspective of Aristophanes’ Knights, the suggestion is that such leading figures are indulged so long as they are useful, and flatter the people in an acceptable manner; there is no suggestion that they should in any way mirror or resemble the ordinary citizens.

Modern western democracies are much less, one might say, pragmatic: even though in practice the electorate are mostly faced with a choice between a selection of members of the elite, the idea is that the best candidate is representative of (a majority of) the voters, in beliefs and values if not in wealth and lifestyle (hence the phenomenon of Jacob Rees-Mogg). The demos has vastly less control over what these individuals then do, but has to believe that their actions in power will reflect those supposed common values. The politicians in turn regularly need to reaffirm or perform those values, asserting common ground with their ‘base’, regardless of their actions and of their actual view of their supporters (cf. Kieran Healy’s comment, in a discussion of Wednesday’s events in Washington DC, that “Trump loves his crowd, but he has no tolerance at all for the individuals who make it up.”).

Electoral failure is then generally blamed not (publicly, at least) on the ignorance and irrationality of the voters but on a failure (whether by the candidate, or the party programme, or as a result of opposition tactics) to communicate the right values successfully to mobilise key constituencies. But that’s then tricky if a representative political system starts to involve populism, with politicians claiming to represent ‘the people’ rather than specific constituencies of them (and decrying any concern for particular groups as a dangerous form of factionalism or identity politics). Then electoral defeat can only be the result of cheating, thwarting the will of the people (or the Real People), and the populist politician cannot concede without undermining their claim to represent the people – he must sustain the narrative of betrayal.

The closest we get to anything like this in classical Athens is Pericles, when what was in name a democracy became the rule of the leading man, as Thucydides put it, with hefty doses of coercive rhetoric to try to subsume citizens within the polis and to put this entirely in the service of his agenda. (Cleon is regularly denounced as a populist, for his alleged flattery of the demos, but I’m increasingly convinced that he’s radically distinct from any modern populism, unlike Pericles). But mostly this comparison emphasises the differences; Pericles’ power still depends on his ability to persuade everyone else of his wisdom and foresight, and it’s constantly subject to revision and limiting. He might feel betrayed, as in his petulant final speech, but there is no plausible recourse to claims of cheating in his defeat.

What is potentially ‘unfair’ in an ancient election is not the voting mechanism but the failure of ordinary citizens to discern true virtue when offered the opportunity to vote for it, because of their ignorance and/or the devious rhetoric of opponents. But no one cites Thucydides in relation to current events because they’re genuinely interested in the workings of Athenian democracy…

January 5, 2021

The Bare Necessities

Here we go again… The return of lockdown brings some very familiar feelings: relief that what seemed like pessimism in early December (stocking up on cat food and soya milk in anticipation of possible Brexit disruption, deciding to stick with entirely electronic reading lists although students were asking about hard copies of stuff in the library) has left me in a better position than I might have been, frustration and uncertainty about how to modify teaching plans again. This term should have been easier (and maybe still will be) as we’ve all got better at the different elements of online learning, not least by working out which ones aren’t worth bothering with. However, someone somewhere was obviously feeling optimistic at a critical moment, and so we’re currently scheduled to have less recorded and asynchronous stuff and more face-to-face time in any given module – although the latter will now be online for most if not all the term. A more precautionary approach would have been to assume that we’d be lucky if we could just carry on in the way we have been, but no…

You could label this an unforced error, insofar as it reflects (and reinforces) the general perception that asynchronous learning is by definition inferior, rather than being the result of direct government incompetence and wishful thinking. The good news is that it’s relatively easy to fix, probably just by me recording more material than planned on top of the extra ‘class’ time. But it does feel like a repeated pattern; not just the tendency towards optimism about things returning to ‘normal’ as soon as possible, but also the particular (and not always intuitive) definitions of what ‘normal’ is. The paradigm remains the A-level fiasco back in the summer, where until far too late it was simply taken for granted that whatever else happened results must be made to conform to the patterns of previous years; ‘normal’ is students from the best schools getting their expected grades while other students know their place and accept it. Similarly, many of the issues facing universities stem from the almost unquestioned assumption that the normal pattern of mass student migrations in September, December, January etc. will naturally take place, regardless of how different things may be in between. Yes, of course there are also all the financial imperatives to maintain this; that just emphasises how far priorities may be skewed…

If occurred to me this morning that one of the issues here is a repeated confusion about the identification of what is ‘essential’ and ‘necessary’ (and therefore should be a priority) and what is ancillary or superfluous – driven, most of the time, by a lack of any sort of analysis, instead just assuming that it’s obvious. Take the idea that all but essential shops should close. Shops are precisely the sorts of places where infection is likely to spread (strangers mingling indoors); but people still need to be able to buy essential supplies; QED. But one potential consequence is that more people then visit the shops that remain open, increasing infection risk; what you really want to discourage is non-essential shopping, but keep as many shops as possible open so as to space out the people who do need to buy things.

Further: how do you define an ‘essential’ shop, or commodity? Intuitively, it’s obvious – hence those stories in the first lockdown about over-zealous supermarkets cordoning off some aisles. But, like the distinction between ‘luxuries’ and ‘staples’ – a major part of my life’s work in ancient economic history has been to try to banish such terminology completely, as being utterly unhelpful – the distinction tends to fall apart the moment you look at it in any detail. Flour: clearly an essential – except, how many people today actually depend on baking their own bread (and that’s before we get to the question of whether organic spelt flour is more or less essential than plain white Home Pride…)? Chocolate: clearly not essential – except for psychological well-being and a little comfort. Bookshops: clearly not essential – unless you have children at home and would prefer them not to be staring at screens all the time. And so forth. You can make a case that most things may seem essential, or at least more than a superfluous luxury, for some people at some point – and the correct response is not to condemn them for their decadence and lack of moral fibre (it is striking how far the advent of any sort of crisis brings out a latent Puritanism, or atavistic reversion to imagined Spirit of Rationing and the Blitz) but to think a bit harder about what you’re actually hoping to achieve by closing ‘non-essential’ shops. I assume that it wasn’t, consciously, just to boost the profits of Amazon and other people who can still provide people with things they need.

There was a brief period, back in the first lockdown, when there seemed to be some recognition of the problems with taken-for-granted ideas of the ‘essential’: when it was noted that actually delivery drivers, shop and warehouse workers and the like were just as vital for keeping society on the rails as the much-clapped NHS. It didn’t last; the idea that we might re-think some of our assumptions and priorities as a result of the pandemic faded rapidly, not least because the government was so determined to get things ‘back to normal’. Same procedure as last year? Same procedure as every year. So there must be A-level results so children can be sorted, and they must be similar to results in previous years regardless of all other circumstances; and students must migrate around the country for the standard university experience, even though they won’t actually be getting anything like that, and they must all return home for Christmas, because Christmas, and so forth.

While the luxury/staple distinction is not helpful, except insofar as it helps us interrogate some assumptions, there is a useful idea within that discourse: substitutability. How easily can one thing be replaced with another, without a significant loss of utility and/or additional expense? How adequate is the substitute in different respects? We can agree for the sake of argument (and before I get yelled at from Oxford as usual) that face-to-face-in-person teaching is easily best, especially for more advanced seminars – but is it completely irreplaceable (even if increasingly adulterated with masks, distancing, 75%+ of the students being online etc.)? Or is there a point where you can reasonably say, this isn’t butter, but in the absence of any butter it will do, and in some respects it’s actually better for you? The problem… one of the problems… among the many problems with teaching this year has been the dogged insistence that only a single specific form of interaction with students is properly acceptable, regardless of circumstances – so when the circumstances have forced a change regardless, everyone is primed to assume that it is by definition inferior and inadequate. I maintain that the substitute isn’t half bad, and it could have been better if we’d been able to devote more time and energy to developing it on its own merits.

But there are things that cannot be so easily substituted. Is sitting in a room all day on your own with occasional (mostly passive) online interactions, or at best seeing the same small group of people twenty-four seven, an adequate substitute for the usual ‘university experience’? Manifestly not. As Jim Dickinson at WonkHE has chronicled throughout the year, we’re faced with a weird double-think: students must be brought back to campus because that’s what university is all about, but then denied any sort of social life – massive restrictions on what student unions and societies were allowed to organise – because that’s not what university is all about. If f2fip teaching were genuinely non-substitutable then this might be an acceptable trade-off, but since we can do good-enough teaching online at a distance, that rationale falls away. I don’t think I’m just being naive in thinking that this is not only about the money (though clearly any more radical approach would require rent refunds, government support to universities etc.); it’s about the pretence of (or desperate longing for) a return to something resembling ‘normality’ in some respects, crossed with assumptions about the ‘essential’ and ‘non-essential’ aspects of a university education, all of which tends to fall apart if you examine it carefully, but that doesn’t stop it being powerful.

And, realistically, things are unlikely to improve. We’ll muddle through this term, with or without a return to limited f2fip classes in March (my money is on ‘nope’, but even if we do I doubt that many students will actually return to campus then), all predicated on the assumption that this is a temporary thing and we’ll be back to normal in September. And by the time it becomes clear that this won’t happen – that the roll-out of vaccination is slower than currently promised, or that it has less of an impact than hoped – it’ll be too late to make significant changes, so we’ll have to muddle through next year as well. From a teaching point of view, that’s manageable, as we’ve already done it. What’s worrying is that we are nowhere near developing decent alternatives to the default idea of student experience and social life, as this year it’s simply been dumped in the deep freeze. And of course there is no realistic alternative to the current model of the UK university, because Too Big And Complicated, plus sunk costs.

Happy New Year! Meet the new crisis, same as the old crisis…

January 1, 2021

What I Did On My Holidays

It’s that time of year when I feel even more directionless and dispirited than usual; obviously, as resolutions go, “be less crap and stop feeling sorry for yourself” sets the bar simultaneously too high and too low. I’m honestly not sure whether I should be planning to devote a bit more time and energy to this blog, or swearing off it for at least a couple of months.

The one thing I do increasingly realise about myself is that I like making and doing things, rather than all this wretched brain work. Maybe the alternative career plan, of becoming a chef, made more sense than I realised – though I doubt that I’m robust enough for all that pressure and shouting. But I can at least make sure I schedule time this year for cooking and brewing and gardening and sausage-making and the like, rather than just beating myself up that I’m failing to get any writing done.

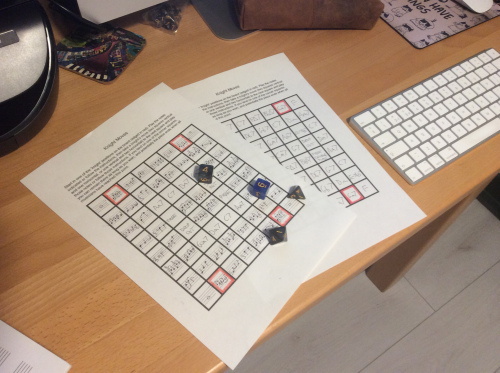

And I will certainly be carrying on with the music; composition classes resume in a fortnight, and in the meantime I’ve been experimenting with the graphic score approach I mentioned last month. ‘ Knight Moves’ does indeed consist of a chess board, around which the musicians plot their way using the classic knight’s move, remaining on each square for as long as they wish (and with some interpretative latitude), until eventually everyone reaches one of the corner squares and decides to stay there. For the purposes of recording a version of the track, I simply rolled dice…

No, it doesn’t sound great – I think I need to write better melodic fragments (I was hoping for more interest to be generated from the interplay of the different instruments), and probably think of ways of messing about with the tonality more. But it doesn’t matter, because no one else is ever going to play this or worry about it. Might it work better with actual musicians listening to one another at the same time as following the score? We will undoubtedly never know…

December 27, 2020

Journal of the Plague Year: 2020 on The Sphinx

As I remarked in the run-down of my favourite posts of 2020 by other people, it’s now traditional at this time of year to bemoan the continuing, apparently inexorable decline of blogging, and to wonder whether it’s worth the trouble. Page views are down another 20% or so on last year – though the optimistic perspective here is that this represents a slowing of the decline in absolute terms, and the number of visitors is more or less the same (and might even be slightly higher, if this end-of-year review gets some traction…). Writing posts has at times felt almost impossible, as I struggled with the joys of Long COVID – but less impossible than any proper academic writing, so the result has been a reasonable level of production here, while my ‘to do’ list for the professional stuff gets ever longer. And this year, more than ever before, the pleasure of reading old posts is the rediscovery of things I genuinely have no recollection of writing…

January: ah, those fabled days Before It Happened, when we were all exhausted and alienated in f2fip mode rather than on Zoom or Teams. I seem to have started the year in a state of professional confusion, whether reflecting on Hunger Games at the SCS conference (something it now seems vanishingly improbable that I will ever attend in person) or on the laughable idea of having any sort of career plan. It is a direct consequence of having now had three or four decent nights’ sleep in a row, thanks to a combination of imperial stout and deranged insomniac cat being slightly more normal recently, that my angst is currently limited to the number of deadlines I’ve missed or will miss in the next couple of months, and the still ill-defined nature of next term’s teaching.

February: as evidence that I was still capable of thinking in joined-up sentences despite all my struggles with teaching Macedonian history, I enjoyed engaging with the ideas of Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman as applied to C5 Greece in Weaponised Imperialism. I also finally managed to finish a piece on staff-student relationships in academia and why they are an unbelievably bad idea, only fourteen months or so after I first started thinking about it. But the major thing this month – the one thing I’d claim as an academic achievement this year, not an individual one but a collaborative project, was the Do What You Must/Melian Dialogues performance, and I’m not going to miss the chance to promote this again:

March: this, of course, is when things got interesting. On the 6th, I was sarcastically (but also opportunistically) developing a Grand Theory of the Whole of History. On the 7th, we get the first of many commentaries on how Thucydides can and can’t help us make sense of Coronavirus, and the first of a fair number of commentaries on the experience of teaching under these new conditions. What is striking, in retrospect, is how much energy I had at this point, whether because my inner Ballardian antihero was coming into his own, or in response to a new set of challenges, or simply because the deranged cat was in one of his better phases (to be honest, I’d forgotten how long this has been going on). Result: twice as many blog posts, determined making of kimchi and other preserves, and a sudden urge to make silly videos in a false beard…

April: it’s very difficult not to see this month’s posts through the lens of dramatic irony; still full of energy at the beginning, belatedly catching up with and offering snarky critique of dubious Thucydides receptions and misattributions, then some reflections on the start of the new term and the ‘new normal’ of teaching with the first hint of some flu-like symptoms, and finally an attempt at coming to terms with not doing too much after definitely succumbing to something nasty.

May: it was, in the first instance, a pretty mild dose of COVID-19, and by the end of the first week of May I was happily blogging again about the possible styles of teaching under pandemic conditions and, still more cynically, about the possibility that some universities were taking advantage of the crisis to put existing plans into practice. There was then a fortnight of silence, that I didn’t discuss at the time because I was feeling awful again, a pattern that was to repeat over the next few months. And then I felt well enough to comment on a truly astonishing US State Department paper on Huawei and state security.

June: if I recall correctly, I decided to take June pretty well off, rather than running myself further into the ground by trying to get some writing done – which is why I was posting quite a lot at the beginning of the month: continuing reflections on next year’s teaching, which I guess will date rapidly, and a comment on John Cleese’s take on toppling statues of racists. At the end of the month, I felt energetic enough to get furious about private schools fiddling grade predictions on UCAS forms. In between, I reflected on the beetles in the new pond.

July …was not great. There were posts, on topics from interactions with Thucydiocy deniers to reflections on the future of conference networking. But increasingly they were short, fragmentary, underdeveloped and distracted – I really would like to find an illustrator with whom to collaborate on a comic book Thucydides, but I could have done a much better job of selling the project if my brain was working better at this point in the year.

August: all a bit dark this month, from worrying about student mental health in the coming academic year, to sheer fury about the A-Level fiasco. It was necessary to go back to the 1950s, and the unexpected deployment of Thucydides to recruit nuclear weapons scientists, to find anything cheery to write about.

September: generally, when I do these retrospectives, it’s quite obvious which posts are worth trying to revive, or at least which ones I want to try to force people to read. This year, not so much. Yes, there’s an interesting discussion of the background to yet another Thucydides misattribution that opens up all sorts of fascinating aspects of 19th-century American political thought and the Civil War. But mostly this month was the start of a rolling diary of my struggles with teaching, from ominous foreboding to Welcome Week shambles to simply feeling old and useless, and while it’s a kind of historical record, and an important bit of my autobiography, I’m honestly not sure how much it has to say to anyone else.

October: and it continued… By the end of the month, try as I might to focus on the demise of Eidolon and the need for short scholarship, rather than ‘fast’ or ‘slow’, the predominant theme was my inability to think or write. Similarly, while I would probably have had thoughts about social media and teaching in any case, now it was impossible to detach these from my struggles with online teaching.

November: one of the genuinely positive things about this year were my online jazz composition courses, which offered valuable insight into the experience of being a student in these new conditions – most valuable of all, the experience of being useless. Perhaps because term was settling down by this point, if only in a ‘no one know anything, expect the unexpected and expect government policy to be gibberish’ manner, I found the energy to comment on wider academic developments, with the establishment of exciting new peer review opportunities and some reflections on Oswald Spengler and reasons for shunning him.

December: finally… As term began to wind down, I had some final reflections on student well-being through the lens of Thucydides, and found the time to write up something I’d been planning for ages on Thucydides as chocolate card, and even to deal with a lot of people on the Twitter getting angry about the incoherence of ‘indigenous British population’. And of course there had to be one more reflection on teaching through the lens of jazz composition, this time imagining the seminar as jam session. It’s been that sort of year.

December 23, 2020

The Masterplan

I think it’s only appropriate to round off my blogging year – apart from the usual annual review, and unless something else strikes me in the meantime – with a final reflection on teaching inspired by my jazz composition course, which has been the one unquestionably positive experience in this basically rubbish year. This time it’s not about online learning and teaching, but a more general thought about managing seminars; and it’s inspired not by the tutor, but by conversation with other students on the discussion thread where we posted our homework exercises for comment (stifles deep sigh at total failure to get any sort of online discussion going in any of my modules this past term…).

This was in the week when we were exploring writing and arranging for a larger number of instruments; one person raised the topic of graphic scores, another talked about their experience of actually performing one, and we all started developing projects to work on over Christmas. Graphic scores are fascinating things, as this handy explainer with pretty pictures from, ahem, Classic FM handily explains. Partly, the exercise is a matter of “why the hell not?”, bringing together art and music in a way that goes beyond video projection as a background to performance, but still more such scores aim to push musicians to expand their imaginations and explore new creative approaches – rather than just playing boring old specified notes. And considered at the level of the ensemble performance and from the perspective of the composer, especially in jazz, it’s a means of finding new balances between freedom and structure, through elements of chance and play.* (And, yes, I’m indulging in especially long sentences with a lot of subordinate clauses, as a kind of antidote to the experience of having to revise a chapter for an editor who regards semi-colons as some kind of Old World decadence…).

This is where I start ambling towards a point. Let’s think of a seminar as an extended jazz performance, with the lecturer in the role of band leader – but a Charles Mingus sort of band leader, where it’s all about the ensemble, rather than one of those flashy show-offs who just want a backing group. The topic and the prescribed reading are the lead sheet, so everyone is working with the same material, Ideally everyone has rehearsed these enough to improvise successfully around the themes and structure and create something interesting and worthwhile – even another retread of Autumn Leaves can be exciting and productive for those involved, if only as practice for interacting with others and responding to their ideas. No, no one’s going to want to listen to a recording (even in pandemic times); it’s about what happens in the moment.

That’s the aim. More often, it’s a matter of hoping that enough people have done the prep to carry the rest, and that there are one or two who can produce flashes of brilliance out of nothing on the spur of the moment (but not allowing them to unbalance the whole performance). And we’re all familiar with the occasions when the only thing to do to produce anything passable is to stick closely to the music, or for the leader to become increasingly dictatorial in forcing people to perform, or to take solo after solo to fill the silences.

And I do understand why this is from my own playing career, or rather lack of one – I find playing with others terrifying, so haven’t done it much (I was just gearing up to try again in March…), so it feels even more terrifying. I know the answer is to be well prepared and to stick to what I know in the first instance – but until I’ve actually got some experience, there is no way of knowing how much preparation is sufficient, and that then becomes a reason for finding excuses to postpone. Yes, it would do me good to have a scheduled session and know that I’ll be told off if I don’t show; if I had to do it, I would. For a significant number of my students, either the thought of having to improvise around some passages of Thucydides is even more appalling than the idea of having to improvise around Satin Doll is for me, or they have even less motivation.

So what’s the way forward? Thinking about this in terms of jazz isn’t just whimsical self-indulgence; above all, it offers an alternative perspective on things which I’ve come to take for granted, and suggests new approaches that I might try…

(1) It’s not just about the material. Okay, this may be a tricky starting-point, since in many cases seminars are about the coverage of new material, necessary for the assessment, not least because that’s how we persuade students they’re worth turning up to. But if we focus on the contents as raw material to be explored and reconfigured in the way that jazz musicians take apart a standard, where does that take us? Need to find the balance between forbidding complexity and excessive simplicity, either of which demand a higher level of knowledge and ability. Need to find the balance between too little and too much – again, discussion of a single paragraph could make for a fascinating hour in the right hands, but not with beginners, while setting too much for fear of running out of things to say will just lead to everyone being under-prepared. Select stuff that’s the right level of difficulty, and a good basis for practice, not because it’s classic or especially important.

(2) Learning to participate. There are many different facets to being a skilful improviser and constructive group member. It’s about having something to say when it’s your turn – and the prepared riff or solo, and structures that allow people to make use of stuff they’ve prepared, certainly have their place – but also being able to come up with something when suddenly put on the spot. But it’s also about responding to what others have said – ideally, the discussion takes on a life of its own, rather than ping-pong exchanges between the leader and individual students, but while waiting for that to develop there’s a lot to be said for structured dialogue, designating specific people to respond to one another – develop the previous motif in some way… Spontaneity has to wait until everyone is up to it, even if that’s less enjoyable for the leader, who needs to know when to cajole, when to orchestrate, and when to get out of the way for a bit.

(3) Creating a safe space. I think one of the reasons I am so terrified of trying to play jazz with other people is the anecdote about the drummer throwing his cymbal on the floor when a young Charlie Parker tried to sit in and didn’t know his scales well enough; yes, the whole point of the story is that Parker then practised his socks off and anyway was a genius they just didn’t recognise it yet – but since I’m definitely not a genius, what I get is the fear of utter humiliation. Actual amateur jam sessions aren’t like that (even if there is always That Guy needing to demonstrate his superiority); seminars are even less like that – but I think that is what students fear. Even with lots of preparation, you can’t know if what you have to say is worthwhile or stupid (and there is always That Guy who sounds boundlessly confident on the basis of very little actual knowledge). The goal is to make sure that everyone feels they can try things out without fear, that there is something valuable in every contribution even if it’s just the making of it rather than the contents. And this links back to (1): the more that the seminar contents matter for assessment, the more often the leader will need to spend time – and risk student demoralisation – by correcting errors and misapprehensions, explaining things at length, calling a halt to a promising line of discussion because it’s a bit off topic etc. Ideally, what happens in the seminar discussion stays in the seminar discussion; it’s about the process, not the product.

And what about graphic scores and the like? Well, those are really about shaking experiences participamts out of their comfort zones, so not on the whole relevant to inexperienced participants who don’t yet have a comfort zone. But I can still imagine some possibilities, whether to destabilise the ‘me leader, you humble rabbits’ dynamic of the seminar room by shifting responsibility for organising the discussion to chance, or by presenting the task of commenting on ancient sources in a new way. I’ll need to think about this further…

* Yes, my Christmas project is Knight’s Moves, an 8×8 board with different patterns of notes or instructions on each square, which each musician moves about as they wish using the knight’s chess move, partly in tribute to Georges Perec’s La Vie Mode d’Emploi…

Neville Morley's Blog

- Neville Morley's profile

- 9 followers