Neville Morley's Blog, page 19

August 15, 2022

Release the Bats!

Yes, it’s been a quiet month on here. Too much heat for my liking; a lot of time spent watering the chillis and aubergines in the greenhouse as a result; and [whispering very quietly so the gods don’t hear] I have actually been feeling slightly more myself at last, so have actually made some progress with writing. But I’ve also been doing some other stuff, in particular organising the Castle Cary Big Bat Count that took place on Saturday.

One of my lockdown investments – probably the second-best one after the new pond (which is looking rather sorry for itself at the moment – but water is still clear, what’s left of it, and there are still lots of mating dragonflies) – was a bat detector. We get lots of bats flying over the garden, but had no idea what they were – basically, due to combination of smallness, speed and darkness it’s pretty well impossible to identify bats visually beyond ‘some sort of pipistrelle’ (very small, fluttery) and ‘maybe a serotine’ (bigger, more swooping). The answer is some sort of ultrasound detector, as all the different species have distinctive echolocation and social calls; there are gadgets that allow you to listen (is it a rapid peep-peep-peep or a slower pwoop pwoop?), and fancy expensive gadgets that plug into a tablet to give you a visual representation of frequency range and ‘shape’, and then the software offers its best guess.

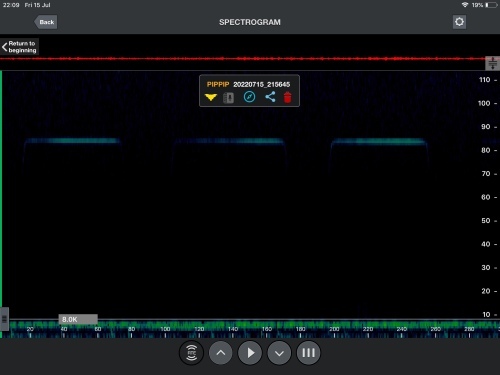

Having now had this thing for two years, I’ve got reasonably good not just at spotting and identifying the common signals before the software does, but even occasionally spotting things that the software doesn’t. It records and analyses a segment, and bases its suggestion on frequency of identifiable calls within that segment, so does not cope well when several bats are squeaking at once; the image above shows the utterly distinctive call of the Greater Horseshoe Bat, which came in at the tail end of a vocal Common Pipistrelle so the latter is what the software identified. And a fair number of bats have similar calls, and can be mistaken for one another especially if they’re further away, so I now analyse the more unusual ones with the help of a detailed guide, rather than just accepting the offered identification. We regularly get seven or eight species, and over two years I’m reasonably confident that we’ve had at least ten or twelve and maybe as many as fourteen of the UK’s eighteen breeding species – I’m realistic enough to mistrust some of the software’s more esoteric suggestions without a really clear recording.

I have in various occasions taken the detector round to friends’ houses, though the results have been a little humdrum – either our garden is a particular hotspot, or, more likely, you need to spend quite a lot of time detecting, which isn’t entirely compatible with being sociable. The idea of the Big Bat Count is, in a way, to test these two hypotheses by getting a decent picture of bat activity in the area. It’s part of a Somerset-wide endeavour to record wildlife; the Somerset Bat Group is organising some big public events, e.g. in Taunton, where they bring along a load of detectors and organise volunteers into groups to survey the town, but they’re also happy to loan the equipment and support the endeavour if other people want to organise such an event. Which is what I did, rounding up assorted friends and neighbours who had at one time or another unwisely expressed interest. We gathered at eight pm for briefing, then headed out after sunset to detect bats for an hour and a half before reconvening at the pub.

It was, overall, a great success; we doubled the number of Somerset bat observations (these now all need to be verified by experts), detecting eleven species on the night, and we have at least a partial picture of the different areas of concentrated activity. It’s not a complete picture owing to the phenomenon of “thank you Neville for your carefully designed division of survey areas and instructions, but we think there should be a load of bats up at the old Priory so we’re going there” – from someone I didn’t actually know, so couldn’t tell them not to…

I guess this must be a relatively common phenomenon in ‘citizen science’ – the tension between different motives, between enthusiasm and rigour. For a proper survey, you’re actually interested in identifying areas of low activity – evidence of relative absence in some parts is potentially significant for getting a sense of where bats may be roosting, where their feeding grounds and flight routes are etc. But the people who’ve volunteered to take part are there to detect bats – hence the drive to go to places where they expect to encounter them. It is perhaps a bit like the impulse behind certain kinds of metal detecting – the primary desire is to find rare and interesting things, rather than to survey an area as an end in itself, even if that would be more significant from a scientific perspective.

This was the first time the Bat Group has supported one of these events, so I think lessons have been learned, including about how to communicate the aims of the activity effectively – certainly I’d do some things differently next time. In the meantime, I am fighting the urge to become obsessively rigorous in my own record-keeping – at the moment, I record what species I detected on a given evening, rather than the number of observations. I feel compelled to start creating spreadsheets…

July 27, 2022

Dog Eat Dog

What should an academic career in the humanities look like today – beyond “not like this”? The question is prompted in the short term by the fact that Mary Beard, to mark her retirement, has taken the opportunity to promote discussion of the academic precariat and the extent to which things have changed over the course of her own career; but if, like me, you use Twitter partly as a means of networking with younger colleagues and early career researchers, this is a topic which has long been pretty well impossible to avoid. One way of trying to think about it, from a not-as-old-as-Mary-but-still-moderately-decrepit-and-comfortably-established perspective, is to wonder about the ideal against which the present situation is being compared; what is it so much worse than, and when did it all change?

No, this isn’t an attempt to segue into “actually in my day we had it so much worse than you snowflake youngsters. Cardboard box?” I am, I hope, quite conscious of my own privilege here, above all the fact that my entire education was publicly funded rather than involving student fees and debt. But I think a bit of historical perspective might offer a starting point for reflection.

So, back to the 1990s… My own experience was one of getting through the fourth year of the PhD on a mixture of what we’d now call zero-hour undergraduate teaching jobs, hardship funds and my supervisor hiring me to do some preliminary work towards a planned Collected Papers, while failing to get anywhere with applications for Junior Research Fellowships; for the following year – just as I was busy applying for the civil service – I was hired as maternity cover for six months in Lampeter, and with a bit of extra income for examining in the summer term, managed to make the salary cover nine months before moving back to my parents for the summer. By this point I had been offered a further two-year contract in Lampeter and a permanent position in Bristol, so didn’t need to worry about staying more than three months in the family home or going back to civil service applications – but I had no sense that this was guaranteed, not least because my JRF applications had continued to impress absolutely nobody. In one alternative timeline I could have quit academia at that point; in another, I got a two-year extension and then couldn’t find anything else after that.

Were any of these possibilities more or less normal for the time? I’m not sure; thinking of my rough contemporaries, there are some who followed a similar trajectory into permanent positions after a couple of temporary teaching jobs; some who got JRFs and then moved seamlessly into longer-term positions in Oxbridge; some who got JRFs and then permanent posts elsewhere, some who got JRFs and then didn’t find any other jobs, some who never got even temporary posts, some who never tried, and some who embarked on careers of temporary positions that continue to this day. And all these people were fully qualified with PhDs and a track record in giving conference papers and the like – it was an older generation, now long since retired, where you found people who had apparently wandered into permanent lectureships or fellowships without actually getting round to acquiring a doctorate or any sort of research record, and that was surely linked closely to the contingent circumstances of the massive expansion of higher education in the 1960s.

So, not everyone got a job, let alone straight after the PhD; great researchers and teachers were already falling out of academia, and it was already possible to imagine a career of endless temporary posts (not least because I remember setting myself a time limit for how long I’d be willing to do that). I’ve no idea of which path was more common, or in some way normal, back then, and I’m not sure how you’d establish this with any certainty. Is it possible that our current sense of crisis is shaped partly by persistent memories of the generation that really did easily got jobs in the 1960s, and/or by the dominance until relatively recently of Oxbridge graduates who had (on average) a better chance of getting a JRF to write up the PhD and hence put themselves in a better position for a permanent job, and/or the survivors’ bias that we see the people who got jobs not the ones who didn’t?

Some things have undoubtedly changed. Firstly, the expectations of qualifications and achievements to be taken seriously for a permanent position have mushroomed to an absurd degree – actual publication record not just plans, social media profile, impact ideas, experience in everything – which partly reflects the impact of the REF and mostly suggests that there really is a higher level of competition for positions, such that job adverts can demand such things and would-be applicants find themselves in a never-ending arms race to have done more than their rivals.

Secondly, it seems plausible that there are more post-doctoral research opportunities, with the greater emphasis on big research grants with PDRAs – scarcely a thing thirty years ago – and on externally funded research leave requiring fixed-term replacements, all driven by the demands of the REF. This doesn’t mean that any individual ECR has a better chance of getting one – that depends on the level of competition – but it is surely easier than it once was for some ECRs to extend their sequence of temporary positions rather than quitting academia altogether at an earlier stage.

Thirdly: I have no data, but I imagine that there may simply be more people completing PhD study. Partly because it offers an obvious explanation for the escalating competition noted in point one, partly because PhDs represent income and prestige and an element in REF so there’s an imperative for universities to recruit more of them, partly because of increasing internationalisation with the UK now drawing from a wider pool of potential researchers. If this is the case, has the number of permanent jobs expanded proportionately? Probably not; some departments have certainly expanded, especially as a result of the change in the student fee regime and expansion of student numbers, but others have not, or have declined or been closed.

Fourthly – and I am really not saying this to try to dismiss the issue – the problem is simply more visible, with the advent of social media. People talk about their experiences, and there are public discussions of the issues in structural terms, where once this was a matter of individual misery/anxiety or at least small-scale conversations with a few fellow ECRs, seeing everything in terms of one’s own inadequacies. The problem has been named, and enough organisations like CUCD and people with responsibility and power in individual departments have acknowledged its existence that there must be at least some hope of stopping things getting much worse too quickly. It’s identified as a problem rather than just the way things are.

Of course there is a downside to this international solidarity, insofar as differences between national systems can be obscured because of the dominance of US-based perspectives. There are undoubtedly issues with some 9- and 12-month teaching fellowships in the UK, and the extent to which the duties and the lack of funding for individual research may undermine the chances of that person then getting a permanent position; and there is always something worrying about seeing someone with a string of temporary positions in the same department, even if that might be the least bad option for that person if the alternative was having to move round the country every year. But I still feel that, thankfully, we are still a way away from the thorough-going adjunctification of higher education on the US model. I appreciate that this is no comfort whatsoever to those who find themselves in precarious positions at the moment, or can see this coming down the line, but we have to name the problems accurately to have any hope of tackling them.

Where does this leave us? I don’t feel any more certain about what the expected, or rather once-upon-a-time expected, academic career looks like to those at the sharp end. Insofar as it’s something like my experience – a couple of years of precarity and then a permanent position for the lucky ones – then comparing now with thirty years ago suggests it’s a matter of degree rather than step change, with the biggest factor – maybe – being that the supply of qualified ECRs has absolutely no connection to the actual demand for them, beyond people being warned by social media or individuals that the academic job market is really tight. Indeed, if you want to get pessimistic, it looks as if it’s going to get a whole lot worse…

This all leads me to wonder if one of the ways in which I have been fortunate in my academic career, besides actually having one, is that I have never had more than one graduate student applying for academic jobs at the same time – I have never had to choose to support one over another, or worry about how to decide between them. I’ve known supervisors with lots of students who will back one student for years, at the expense of others, because of their judgement about relative quality or because of personal affinity. I’ve known supervisors who operate something like a ‘fair chance’ policy – if student A hasn’t got anywhere after a year or a couple of interviews, then weight of support shifts to student B. I can imagine that some supervisors make carefully calibrated decisions about which student to support for a specific position. I have had the luxury of showing unqualified enthusiasm every time.

I don’t otherwise have any sort of conclusion to this, other than to admit the limitations of my own perspective. I would be genuinely interested to know what ECRs do have in mind as the sort of academic career they ought to have been able to expect, and where they think this model comes from…

July 5, 2022

Write Here, Write Now

The continuing joys of Long COVID… The main function of this blog post is just to give a link to a profound and thought-provoking piece by the ever-wonderful Maria Farrell over at Crooked Timber, talking about her experience of living with and adapting to ME/CFS, with an eye to this new epidemic of the after-effects of the plague. It’s full of striking and memorable phrases (“cosplaying normality”!), and you simply need to go and read it, and reflect.

I found it quite uncomfortable, to be honest. This is clearly because, while she emphasises that acceptance is something that will come in its own time, or not, and one shouldn’t rush towards it, this is still an essay about acceptance, about letting go of the life that went before and the person you used to be and, perhaps most importantly and painfully, the life you thought you would go on to lead.

The life you still feel you can almost reach out and touch gradually becomes less vivid, less immediate, until it really does seem like it belongs to someone else, someone who’s gone.

But I am nowhere near this point. I am still at the stage of feeling that I am not me, and struggling – not really to the benefit of my overall health – to try to recover that person, grasping after the flashes and flickers of my old self that emerge from the fog and fatigue, tantalisingly out of reach, like the marsh lights that lead travellers into bogs. The constant hope that suddenly this will all just go away, the clouds will lift and I’ll be back, or if I can just do X, or find Y, it will all be right again. This, at the moment, is not who I am, and I’m not willing to give up on everything that ‘I’ had in mind for the coming years, even if I’m not capable at the moment of any of it.

I feel this especially at the moment because I’m trying to write, and finding it painful even on the good days – and the fact that I can still do this sort of stream-of-consciousness personal stuff may not be helping. So I really empathised with Maria’s account of this:

I remember pulling each sentence rather brutally from the morass of my former abilities and piling them on top of each other. Let’s just say the angel of history made sense to me in a way she had not, before. Minute on minute, I could barely make the letters settle into words, forget about forming sentences or ideas, but day on day it turned out I could do it. It just took a higher threshold of discomfort than I’d previously believed manageable, and about eight times longer.

Again, I’m not there (yet?). I don’t have piles of sentences even; it’s more like a floor covered with fragments of sentences, like the pieces of a jigsaw when you’ve just emptied them out of the box, and the picture that would help me start putting them together is stained and torn and partially lost, and maybe this is a couple of different jigsaws jumbled together. A blg post can start, and ramble on for a bit, and then stop; that doesn’t really work for academic articles. And perhaps this is another ground for refusing to accept things, that I simply don’t know if I can learn a new approach, even if I recognise that the old one was pretty hit-and-miss.

I can’t remember if I mentioned on here that I had actually got to the point of having a chat with Occupational Health; it’s not that I had any expectation of them producing a magic solution, or even that I particularly need accommodations, but the idea was that this would make me take this more seriously, as an ongoing condition rather than a temporary blip. I think this needs a bit more work…

June 28, 2022

Was It Worth It?

And so farewell then, the Thucydiocy Podcast. In seven episodes, stretched out irregularly over several years, you established in mind-numbing detail the different ways in which people have misattributed things to Thucydides, to an audience of many tens of people, two of whom once posted positive feedback… Wait a minute! There is a faint pulse! It lives, to be largely ignored for another day!

Yes, this was all set to be an obituary for my lacklustre foray into podcasting as part of my ongoing dabbling in different forms of engagement. Maybe if I’d managed to stick to a regular monthly schedule, as originally planned, I’d have built up more of a regular audience, but the combination of COVID, Long COVID and general work issues put paid to that – cf. the impact on this blog – and of course I’d have run out of misattributed Thucydides quotes a lot earlier.

Was it worth it? Yes, of course; I always like talking about stuff, and trying to raise the overall level of knowledge and understanding in the world by a minuscule amount, and experimenting with different formats. The more critical question was: is it worth it? Do I keep this going – if only as a legacy project? That’s partly a matter of how to deploy limited amounts of time and energy when I’m horribly behind with everything – cf. this blog again – though spending a couple of hours every couple of months to research, sketch out and record an episode isn’t a huge commitment.

But it’s also, bluntly, about money: Podbean subscriptions have crept steadily upwards, and more significantly the value of pound sterling against the dollar has plummeted, producing a 15% rise in the subscription from last year to this all on its own. It didn’t help that we’ve had over £1K of vet bills in the last two months and are facing an indefinite ongoing charge for pills… How much is it reasonable to pay to subsidise what is, at least in a sense, part of my job? Because, unlike this blog, podcasting isn’t fun enough to count as a hobby, and it isn’t offering incidental benefits (e.g. the ability to sketch out ideas that might turn into something else in future, or even just making a note of things I might want to refer to); it is no more and no less than an alternative means of disseminating research.

I did actually wonder whether, in that case, I might be able to fund it using my research expenses allowance. The answer appears to be no – ‘impact’ activities are an allowable expense, but for things that are intended to form a future Impact Case Study, which an intermittent podcast series is never going to do – and that of course raises further questions about the value of the whole exercise, since my university clearly doesn’t think it’s worth supporting.

On the other hand, this is why the podcast will be running for at least another year: while waiting for an answer as to whether I might be able to get the subscription paid by someone else, I suddenly realised that I didn’t actually have all the episodes saved separately, and so had to renew in order to download them. Which is deeply silly and aggravating – but, since we are where we are, I just have to make another episode to mark the occasion…

Podbean: https://abahachi.podbean.com/e/thucydiocy-episode-8-the-tyranny-athens-imposed/

Apple podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/thucydiocy/id1468450689#episodeGuid=abahachi.podbean.com%2F73278821-23db-38da-b434-b8cacb215524

June 24, 2022

Blank Space

I am not, I would like to think, an unreasonable Luddite. I suppose it could be said that what I am is at best inconsistent; sometimes not a Luddite at all, indeed sometimes the sort of middle-aged man who desperately strives to keep up with odd bits of the technological Zeitgeist, enjoying catch-up TV while wondering what happened to car CD players, and sometimes an entirely reasonable Luddite. I can see, for example, why my favoured approach to constructing an index – creating a simple Word table by working methodically through page proofs, and then doing an A-Z sort – is clearly unsuited to the world of eBooks and online publication. And so I didn’t whine too much when asked to provide a list of index terms when submitting the manuscript of a forthcoming edited volume.

I’m not sure that I really thought about how this list might be used; I simply thought of the terms I would expect to see in the final index. Having now received the proof copy, I have no real idea how the list has been used. In some cases, clearly, they’ve simply done a word search, so we end up with some key terms (‘Thomas Piketty’ is the one that really leaps out at me) being indexed multiple times in a single paragraph. Sometimes, this doesn’t seem to have happened; ‘Egypt’ is in the index list, so why hasn’t it been consistently indexed? ‘Marx, Karl’ is in the list, and whatever mechanism is involved has successfully grasped that ‘Karl Marx’ should be linked to this – but not ‘Marx’ alone, although this problem doesn’t occur with Piketty.

Sometimes there is clearly sone human judgement involved, or a higher level of AI, as it knows to index ‘returns on capital’ and ‘capital returns’ as the same thing; mostly, however, it’s utterly hopeless at synonyms or variations or near equivalents. If the list says ‘population, see demography’, why does it then index neither population nor demography? It is symptomatic that the Author Query claims that the index terms ‘data, reliability of’ and ‘property, rural’ are not to be found anywhere in the text, when the latter topic features in at least a third of the chapters and the former in virtually all of them…

And I have FIVE DAYS to turn the whole thing around? Actually they told me five days and then sent the link to the files on Saturday, with the deadline then set as Thursday… Not going to happen. This gives me just enough time – since, thankfully, all the contributors seem to have done a great job in getting their submissions ready, and my editing doesn’t seem to have missed too much – to insert additional index entries where clearly necessary, but certainly not enough time to remove all the redundant ones, even if I could work out how to do that – even if the system allows it…

I do now wonder what I could have done differently, to learn lessons for next time – and to be honest I’m not sure. Rigidly enforce a limited vocabulary on everyone, to do away with synonyms and variations? ‘Always refer to “rural property” not to “country estate” or “agricultural investment”; never say “unfree labour” when you mean “enslaved people”‘ and so forth… I guess the crucial point is to recognise that where once the art of indexing was about trying to anticipate what future readers might want to look up, it’s now about trying to anticipate what an indexing algorithm that I don’t understand will make of the text…

June 23, 2022

Broken English

It’s always nice to learn that someone has found something you did a while ago useful – yes, I know there are giants in the field who get thoroughly sick of being told how they’ve transformed the understanding and indeed life philosophy of another dozen junior scholars this month, but us provincial types have more modest horizons. This month, I’ve actually had it twice. Someone liked an obscure thing I wrote on ‘historiography as trauma’ in Thucydides and has done the hard yards of a proper analysis of the theme in relation to the Sicilian Expedition rather than just tossing out a few random ideas on the topic – so, watch out for the new piece by Bernd Steinbock. And then I heard about what may prove to be my greatest, if rather unsung, contribution to the world of learning…

Some considerable time ago – twelve years? fifteen? – when I was doing the faculty UG education director role in Bristol, I oversaw the development of a web-based student resource on grammar skills, utilising the then still relatively novel power of hyperlinks, and the help of a student who wrote the draft guidance and quizzes. This was used by a reasonable number of Bristol Arts students over the years – I never gathered any evidence that it actually improved the use of apostrophes, or reduced the incidence of comma splices, but at least it gave us something to direct them towards in essay feedback – and I remember being asked once by someone from another university – Bradford, maybe – if I was happy for them to link to it.

This then just became something referred to in the long version of my cv, as evidence of concern with student skills development if that looked like something worth emphasising (I gave much more attention to my various pieces on forms of assessment, all of which now seem to have disappeared from the Internet, and in any case are long obsolete). Two years ago, however, I was contacted by the Bristol university library to ask if I was happy for them to revamp the resource as part of their student support pages, and I agreed readily with the request that I’d be really interested to hear how much use it then got. Yesterday I received a summary of the last two years: counting people who stayed on the site for more than a minute as ‘engaged users’, the figure is… 38,624.

That is a lot. I mean, this blog has had over 150,000 visitors in its lifetime, but no individual post, even the most popular, even posts retweeted by Mary Beard, has more than a few thousand views at the most, and who knows how many of these people have actually found it useful in any meaningful sense. The Bristol resource is accessible to all – it’s at https://www.ole.bris.ac.uk/bbcswebdav/courses/Study_Skills/grammar-and-punctuation/index.html#/ – and apparently a lot of the users are from overseas, as well as it being linked by other UK universities (one colleague commented on the Twitter that they knew it but had no idea I had anything to do with it).

Of course, this does then become a source of anxiety. The revamp two years ago was just of the platform and the appearance, not the contents – does the guidance still stand up? (Another colleague commented that it’s overly prescriptive on split infinitives…). It was written for Bristol Arts students – might it be in desperate need of revision to cater for a more diverse audience? Language does change, and my intention was to help people avoid the worst errors, not to impose a rigid traditional framework on their writing. Well, it’s long since beyond my control or influence; it’s just nice to know that it’s still there – and that I still have somewhere to direct students who string together multiple clauses with commas…

May 31, 2022

Everything’s Fine

There is a small, rather marginal community, struggling to survive in the face of the pressures of the modern world, heavily dependent on attracting tourists. There is a series of odd and sometimes alarming occurrences, which most people ignore – but a few argue that there is a pattern to them and actually they are signs that the community is faced with an existential threat. The music becomes ominous.

And then there is Denial Guy. Nothing to see here, folks. Just rumours spread by a few self-centred malcontents who want to undermine their own community, and some disaffected tourists angling for a refund. Everything is absolutely fine, and any suggestion that it isn’t will discourage visitors.

Maybe he’s entirely sincere, just complacent and myopic, or simply terrified of change. Maybe he likes the attention from the local newspaper, as it sets him up as the heroic defender of communal values against troublemakers who don’t respect tradition. It doesn’t matter; either way, he can prevent anything being done until it’s too late by raising questions about the necessity of doing anything at all.

No, this isn’t about anyone in particular. If it was, I might be expected to name names, rather than just offering vague insinuations about fifty-something subversives and angry graduate students in the expectation that enough of them will get cross about this and thereby out themselves.

And the one thing we know from the movies about Denial Guy is that reasoned argument gets nowhere, and impassioned protest simply confirm him and his supporters and the press in their belief that he is indeed the voice of reason and common sense, being cancelled by a mob. If the community is to be saved, we just need to get on with things, and ignore him.

May 26, 2022

Public Image

Ah, the brand. The backbone of all that we do, the foundation of international success, the very heart of the institution. It’s not enough to produce excellent teaching and research if your logo fails to communicate your core values in just the wrong shade of green.

But things could be worse. I am still trying to process the fact that there is a bona fide research consultancy firm called Melian Dialogue. The strong p-hack, the weak just accept their disappointing data? Charitably, maybe it is just about the crude recognition factor of Thucydides’ name and the most famous bit of his text – after all, there is already a software testing library called Thucydides. But the ‘About Us’ section of their website isn’t wholly reassuring to a cynical Thucydidean.

Melian Dialogue dramatises a series of negotiations between Athenians and Melians written by Thucydides, a classical Athenian historian in his book History of the Peloponnesian War. It is taught as a classic study of political realism and unapologetic rationalisation of one’s actions… We use Melian Dialogue as our unapologetic approach to shape research the way we think it should be and discover practical insights and meaningful data not guided by dogma, tradition, academic convention, or expectations. We are unapologetic in our questioning of what is considered ‘acceptable’ knowledge and business intelligence.

Uh huh. The thing about ‘unapologetic rationalisation’ wasn’t supposed to be a recommendation. You can read the Athenian line at Melos as a hard-headed account of reality, as the Realist tradition in IR does, or you can see it as a critique of the self-justifying rhetoric of the powerful. Taking the latter interpretation – these are the specious justifications the Athenians offer for aggression and self-interest – as a model is… special. Maybe they’re a bit shaky on the meaning of ‘rationalisation’. ‘Cos otherwise this looks terribly like “we will get you the research results you’ve paid for by whatever means necessary, rather than those feeble people who will bleat on about academic conventions and integrity and acceptable methodology”.

So, it could be worse. As things stand, the university has yet to propose adopting ‘The society that separates its scholars from its warriors’ as the new webpage strapline…

Update: happy to report that, while the @DialogueMelian account does tweet out lots of vacuous inspirational quotations, including one that is allegedly Seneca, it has just to offer any misattributed Thucydides ones. Give them time…

May 24, 2022

Dead Flag Blues

One of the many interesting questions raised in yesterday’s final session of the series of workshops I’ve organised to explore ‘The Politics of Decadence’ was this: would you describe the current UK government as decadent, and why (not)? Corrupt, undoubtedly, among many other things; but, while decadence always involves corruption, it’s fair to say that not all corruption is a sign of decadence (h/t Shushma Malik, one of the loyal workshop participants, and her work with the Potsdam-Roehampton project on corruption in antiquity). The best questions get to the heart of a range of issues and open up the problems inherent in a concept or approach; while ostensibly light-hearted and trivial, this is one of those questions…

Now, despite my propensity for quoting doom-laden GY!BE lyrics in response to thr state of the world – we’re trapped in the belly of this hossrible machine, and the machine is bleeding to death – my instinct is to avoid embracing the term ‘decadence’ with respect to anything other than ice cream and barrel-aged imperial stout. This is a project about taking seriously other people’s use of the term, and associated complex of ideas, rather than taking it very seriously as an actual description of the state of things. ‘Decadence’ may obstruct rather than aid understanding.

(1) It is overtly rhetorical, over the top and uncomfortably metaphorical (hence, as I argued years ago, historians are happy to use ‘dead’ metaphors like ‘decline’ but steer clear of decadence). The fact that it’s rhetorical and polemical doesn’t mean it isn’t important – on the contrary, and there are important questions to be asked about the nature of its appeal, in different contexts (fascinating observation from Dimitri Almeida of Halle last week, that the French right-wing populist Éric Zemmour deploys such ideas copiously in his books but not in his recent presidential campaign). But this apocalyptical, rabble-rousing dimension is precisely why I feel cautious about adopting the concept myself.

(2) Evoking decadence in a serious manner presents the behaviour of Johnson and his regime as symptomatic rather than a matter primarily of individual choice and values – which is not intrinsically unreasonable, except that ‘decadence’ immediately shifts the discussion to the level of an entire society or culture, rather than to intermediate systems like the British political class or the University of Oxford. It presents the decay of values and virtue as a more or less natural phenomenon, the results of the effects of time on a civilisation or institution. It misidentifies the problem – indeed, arguably this is the point, as ‘decadence’ works as an agglomerator, framing multiple phenomena (many of which might seem quite unproblematic to most people – the divorce rate, for example) as symptoms of the same cultural-level process of decay.

(3) Given that the Johnson persona is already predicated on the trampling underfoot of norms and standards and the enthusiastic embrace of vice and self-indulgence, there is an obvious risk that labelling this as ‘decadence’ actually feeds the myth. I can see the case for a revaluation of decadence as a positive quality in the context of, say, gay rights or modern art; extending this to old-fashioned elite male promiscuity, greed, self-entitlement and boorishness seems unnecessary.

Put another way: as someone (Seth Jaffe?) observed yesterday, decadence is one response to the crisis of liberal democracy; it’s not the only available interpretation, and one can recognise this without thereby denying that there is actually a problem worth thinking about. It’s not an exclusively right-wing response either, though that is where it’s most commonly found; similar ideas about the corruption and decay of society can be found in revolutionary left-wing traditions since the 19th century. Both perspectives aggregate multiple phenomena as symptoms of a system-wide crisis, thereby mobilising genuine grievances and anger for the project of ‘Burn it all down!’ The crucial difference is the imagined future: heightening the contradictions in order to hasten the advent of the new society, or a cleansing fire to root out the corruption and restore the old.

British democracy is clearly in a bit of a state. But it’s not at all obvious that this is a reflection of a corrupt and decaying culture. On the contrary, one issue is the extent to which the ruling class is detached from and out of step with most of the people over which it exercises power – and one reason for that is the success with which it, like other contemporary populist-authoritarian regimes in recent years, has mobilised the tropes and emotions of decadence – demographic anxiety, fear of difference and change, discomfort with modernity, envy and resentment – to win elections.

Since the workshops began, I’ve been sounding the #decadenceklaxon ever more frequently on the Twitter, and not just because I’ve been more alert to examples. The primary target – equally the case before and after Putin’s attack on Ukraine – has been ‘wokeism’, and the defence of racial and sexual equality. This is not a political concept we should be signing up for, or deploying ourselves – but it’s one we need to understand.

May 19, 2022

Caught Out There

This weekend, there’s a fabulous-looking conference at Cornell on Thucydides and Aristophanes in honour of the great and wonderful Jeff Rusten. The advertising on the Twitter is slightly less wonderful…

The Cornell Classics department presents "Plato, Thucydides, comedy: tyrants, demagogues, and the Republic," a conference in honor of professor Jeffrey S. Rusten, an expert on the history of comic drama. May 20–22 at the A. D. White House.https://t.co/Xt7P6hgN3O pic.twitter.com/ZTzYMYLukP

— CornellArts&Sciences (@CornellCAS) May 18, 2022

Now, if this were my colleagues organising a conference in my honour, this would be deliberate trolling; thankfully that’s a very unlikely eventuality, so even if this gives them any ideas they won’t be able to put them into practice. In this case? Yes, it may be that sophisticated Ivy League humour one hears about, and of course (as has been noted on the Twitter) Jeff is far too nice actually to beat anyone to death with a tire-iron in retaliation.

More likely, this is the College’s publicity department sincerely looking for a suitable Thucydides quote for the advertising, and not actually checking it with anyone. It’s relevant to note that the image doesn’t appear on the website as far as I can see. Mostly, this is just evidence of how embedded this and similar quotes are in the information sphere – and how readily people just accept what they find with a quick google search, if it suits their purposes. Earlier in the week we had a different example from the UK, a fake motivational Churchill quote painted on the wall of a school:

This really makes no sense. If I were to write that William the Conqueror invaded Scotland in 1147 it would be wrong. Plain and simple. Accuracy is important. Fact checking is important. Getting basic things right – particularly when you are an educator – is important. https://t.co/Su1df31Zuw

— Otto English (@Otto_English) May 16, 2022

What’s most interesting about this one is the response from the head teacher responsible (who isn’t just a head teacher, it should be noted, but a prominent figure in educational debates, much favoured by the current government): the quote may not be genuine but it “captures the essence” of truth, it may not be real but it works, objecting to it is actually an assault on the school and its great successes, and anyway whom should she apologise to, Churchill?

As has often been noted, there is a remarkable cross-over between people who loudly object to the dismantling of statues, claiming that this destroys history in pursuit of an ideological agenda, and people who loudly object to historical/factual objections to their ideological claims. I don’t think the Cornell College of Arts and Sciences publicity team is in this category – but perhaps they do reflect a more widespread lack of critical thought, that allows the ideologues to get away with their blustering…

Neville Morley's Blog

- Neville Morley's profile

- 9 followers