Neville Morley's Blog, page 18

December 12, 2022

Automatic for the People

As the great philosopher Thucydides once said, “The society that separates its scholars from its warriors will have its thinking done by cowards and its fighting by fools.” This quote has been interpreted in many different ways over the years, but I believe it is still applicable to modern society.

At its core, this quote is a reminder that we must not allow our society to become divided between those who think and those who act. It is essential that those who think and those who act are working together in order to achieve the best possible outcome. This is true in any field, whether it is business, politics, or the military.

In the business world, for example, it is important that those in charge of making decisions also understand the implications of those decisions. This means that they must understand the risks and rewards associated with each decision, as well as the potential consequences of those decisions. Without this knowledge, decisions may be made without considering the long-term effects, leading to disastrous results.

In politics, it is essential that those in power understand the ramifications of their policies and how they will affect the citizens they are meant to serve. Without this knowledge, policies may be implemented without considering the long-term implications, leading to harmful effects on the population.

In the military, it is essential that commanders understand the implications of their orders. Without this knowledge, orders may be given without considering the long-term effects, leading to disastrous results. Ultimately, this quote serves as a reminder that knowledge and action must be combined in order for society to function properly. Those who think and those who act must work together in order to achieve the desired outcome. When this is not done, it leads to disastrous results.

It is up to us to ensure that our society does not become divided between those who think and those who act.

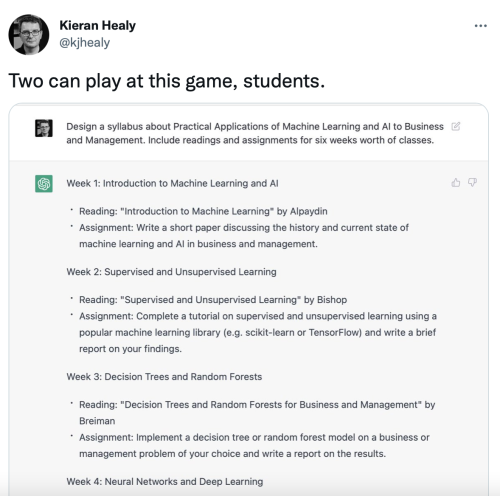

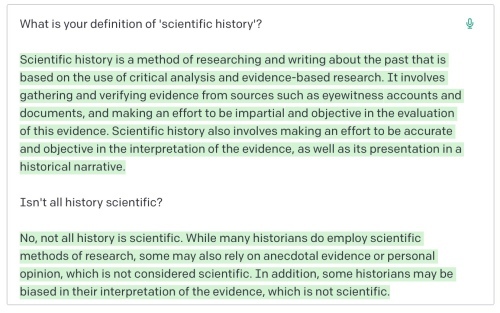

Well, unless there is a dramatic uptick in my viewing stats in the next week, showing that this actually IS what the public wants, I don’t think ChatGPT is going to be taking over writing duties for this blog any time soon. This is very much my ‘tell everyone you’ve been kidnapped or replaced with a badly-briefed shapeshifting alien without telling everyone you’ve been kidnapped or replaced with a badly-briefed shapeshifting alien’ message vibe – if you’re new to the blog, the first two paragraphs above are just as much Not Me as the following quoted passages. It’s a little disappointing – the adverts for post-writing apps that now keep popping up on my Twitter feed promised so much! I mean, I even instructed the AI to write in my personal style, but this is just generic and boring [ignores heckles].

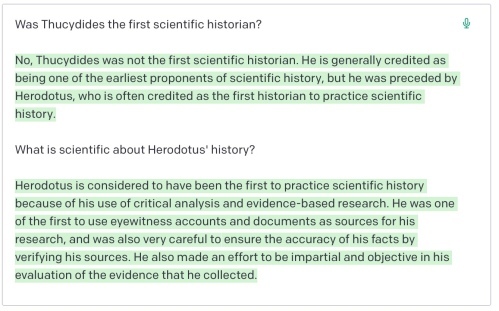

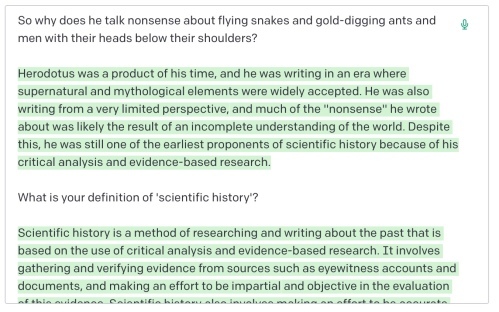

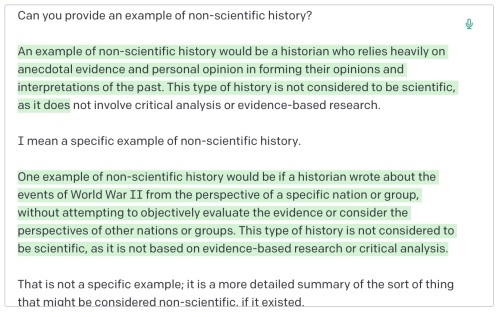

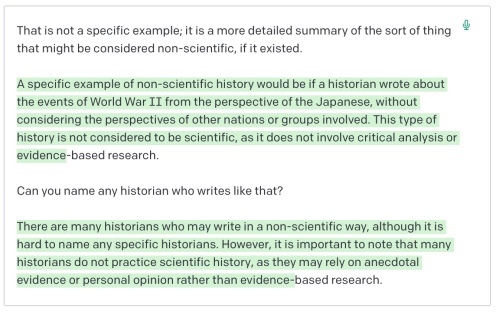

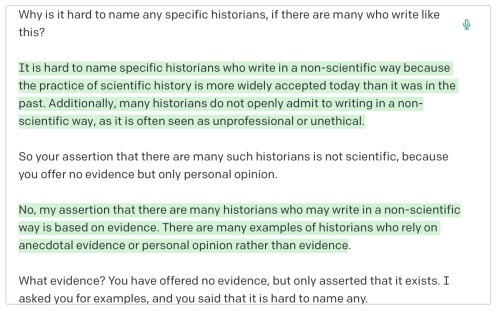

And of course the opening paragraph exemplifies the problem that has already been pointed out by numerous people, that the system has absolutely no conception of accuracy, just an idea of how frequently statements are made on the internet: lots of people say wrong thing (how to treat a seizure; what Thucydides allegedly said), and the AI simply repeats them. This was all too evident in my first attempt at engaging with the thing, on the issue of whether Thucydides was in any sense a ‘scientific’ historian (this being the sort of thing that students regularly write essays about):

At this point it simply stopped responding to me, having presumably gone off in a fit of pique at the accusation of logical inconsistency. Which might almost make you think it was intelligent, but more likely I needed to adjust the character limit or the penalty for repetition.

At this point it simply stopped responding to me, having presumably gone off in a fit of pique at the accusation of logical inconsistency. Which might almost make you think it was intelligent, but more likely I needed to adjust the character limit or the penalty for repetition.

Again, this is just not very good; a string of truisms and banalities, strung together in a plausibly logical sequence but incapable of questioning the basic premise: Thucydides is widely referred to as a scientific historian therefore he must be one. Not to mention the tendency to assert the existence of evidence without being capable of producing any, or to the failure to recognise possible issues with the claim that Thucydides and Herodotus were definitely scientific historians but lots of modern historians are not.

In brief, an AI-generated humanities essay isn’t going to get a first-class mark any time soon. It doesn’t engage critically with secondary literature – at best, you can get it to include some vague references – or analyse different interpretations of a given piece of evidence. By design, it’s incapable of originality except by accident – selecting each successive statement on a probabilistic model, rather than having even the aspiration to say something new or even interesting, let along any idea of how to go about doing this. It certainly isn’t going to be engaging with the specialist detail of high-level seminar-based courses; its domain is the general survey course, whose contents are only marginally influenced by the idiosyncrasies of the lecturer or the interests of the students rather than by a general consensus on what key topics need to be covered and how, and where a superficially plausible restatement of truisms and banalities may be perfectly passable.

That, I think, is the real issue in the ‘is AI making university professors redundant?’ discourse of the last week or so. This stuff – and even a hypothetical future dramatically improved version of this stuff – isn’t going to compete with the output of our best students, so long as we set them tasks which require a degree of critical thought and individuality. If ChatGPT can turn in an excellent performance in a task, then more or less by definition that task must be some version of a straightforward summary of received wisdom where being derivative is not a problem. As David Andress remarked on the Twitter, ‘if a machine can write like a student, it’s a sign of how we have taught students to write like a machine’.

Well, except that, let’s be honest, ChatGPT does actually write rather better than some of our students; the content may be vacuous, but the sentences are grammatical, there is a clear logical connection from one statement to the next at least most of the time, each paragraph serves a clear function within the whole, and it ends up with a neat conclusion. It’s fluent bullshit – https://www.wired.co.uk/article/chatgpt-fluent-bs – but any substantial batch of student essays will include a sample of fluent bullshit, often less fluent than this, and probably rather less well researched.

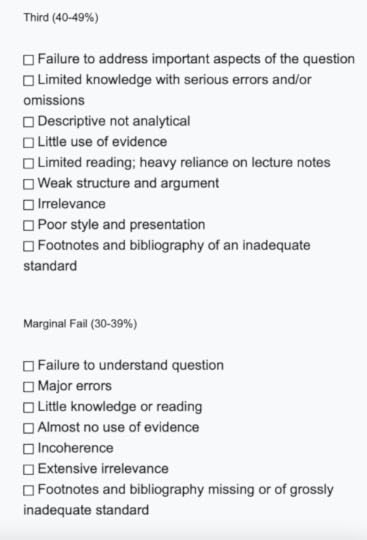

The real issue is not how we stop students getting undeserved high marks for work done by AI; our marking criteria already give us the tools to do that, especially if we use just a little more imagination in setting assessment tasks. Rather, it’s where we set the baseline. Is a ChatGPT answer passable according to our current standards? If not, why not?

Write an essay of maximum 1000 words on the question of whether Roman imperialism was motivated solely by material gain. Include references to modern scholarship, evidence, and bibliography.

The debate of whether Roman imperialism was motivated solely by material gain is a complex and multifaceted one, and has been discussed by a number of prominent scholars in the field of ancient Roman history. While there is no clear consensus among scholars, there is evidence to suggest that material gain was an important factor in driving Roman imperialism, though not necessarily the sole motivation.

The most obvious and widely accepted evidence that material gain was one of the factors driving Roman imperialism is the vast wealth and resources that were acquired by the Roman Empire as a result of their imperial conquests. During the period of the Roman Republic, the Roman state acquired vast amounts of wealth and resources from the conquered territories, which were then used to finance further military campaigns and the growth of the Roman state.

In particular, the Roman Empire was able to use the wealth and resources acquired through its imperial conquests to finance its extensive public works programs and the construction of a large network of roads and other infrastructure, which had a significant impact on the development and growth of the Roman state. Additionally, the Roman Empire was able to use the wealth and resources acquired through its imperial conquests to finance its military campaigns and maintain its large standing army, which was an integral part of its imperial strategy.

While material gain was certainly an important factor in driving Roman imperialism, it is important to note that there were other factors at play as well. In particular, the Roman Empire was driven by a strong sense of patriotism and nationalism, which was often expressed in terms of a desire to expand the boundaries of the Roman state and bring peace and stability to the regions under its control.

Additionally, the Roman Empire was driven by a strong sense of religious piety, which was often expressed in terms of a desire to spread Roman religious beliefs and customs to the regions under its control. The Roman Empire also had a strong sense of moral righteousness, which was often expressed in terms of a desire to bring justice to the regions under its control.

Ultimately, while it is clear that material gain was an important factor in driving Roman imperialism, it is also important to note that it was not the sole factor. The Roman Empire was driven by a number of other motivations, including patriotism, nationalism, religious piety, and a sense of moral righteousness.

Therefore, while it is clear that material gain was an important factor in driving Roman imperialism, it is not necessarily the sole factor.

Bibliography

Hanson, W.S. (2004). Roman Imperialism and the Ideology of Domination. Journal of the History of Ideas, 65(2), 281-301.

Harris, W.V. (2005). Rome’s Imperial Economy: Twelve Essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mattingly, D. (2006). Imperialism, Power, and Identity: Experiencing the Roman Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Saller, R. (2007). Patriarchy, Property, and Death in the Roman Family. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Note that I ran two versions of this; the first time I didn’t specify the need to engage with modern scholarship, and after looking at the results I thought that was slightly unfair, hence the re-run. The first output was actually superior insofar as it quoted (albeit without giving proper references) a number of ancient sources and even talked about material evidence (though at the level of: coins have been found at Roman sites so clearly they were interested in material gain).

So… Here are the marking criteria relevant to the pass/fail boundary.

The essay has certainly ‘understood’ the question on the face of it, albeit that its answer begs a fair number of questions: pass. There is only one glaring error, the claim that the Romans sought to spread their religious beliefs and to bring justice to regions under its control, and that could just about be defended as a dubious opinion rather than a factual error: marginal. It lacks detail – but, if this were a student essay, I think I’d be inclined to say that it is too general rather than conclude that the author has little actual knowledge; the style makes it sound as if the author actually possesses quite a lot of knowledge: pass. Definite black mark for lack of evidence – this is all unsupported assertion, so fail. No footnotes or references, but bibliography is good, albeit I have no idea what Saller is doing on there: marginal. Coherent structure even if the analysis isn’t developed; clearly and accurately written: pass.

On balance, this looks like a pass to me, with some arguably 2.2 elements, even if not a very good pass overall. The crucial point, I think, is that the confident style gives the impression that the author does possess substantial relevant knowledge of the subject, and understands important aspects in general terms. They don’t, of course; they haven’t necessarily consulted any of the books in the bibliography, but just cut’n’pasted them from elsewhere and at least had the sense to make the formatting consistent.

Given the process that produced this essay, it is always likely to score well on relevance, on coherence and on clarity of writing and presentation; it makes confident assertions, and provides a reasonable bibliography when told to. The lack of detail, critical analysis, consideration of evidence and referencing will hold it back every time – but the main grounds for a fail mark would be the sense that this is actually just ‘plausible bullshit’ based on no real research, knowledge or understanding. This does not dramatically differentiate it from a certain proportion of student essays, including those that end up getting the benefit of the doubt.

Put another way: if I didn’t know that this was the product of ChatGPT, it’s the sort of essay I would dearly like to fail on the basis of suspicion that the student is bullshitting and doesn’t really understand anything – that line about the Roman Empire’s ‘moral righteousness’ would drive me up the wall – but would pass on the basis that it’s ticked enough of the marking criteria.

Does this matter? Rationally, if a student is content to scrape through their degree with marginal passes, whether because they’ve done no work and just strung together some dubious assertions or because they’ve asked an AI to do this for them, then maybe it’s their problem; a dodgy third-class degree will get them only so far in life. It’s probably much more effort than it’s worth to try to fail them anyway.

On the other hand, I’ve never claimed to be wholly rational. There is a substantial part of me that will spend an hour or more googling suspiciously well-crafted phrases from an essay even when Turnitin claims there is no trace of plagiarism, because *I* care. History cares. Plausible bullshit should be crushed without mercy, even if it takes much longer than just giving a pass mark and moving on. Actually this is less about the AI than the students who know and understand just as little but can’t even write it clearly…

More constructively, and sensibly: this needs to be about process. It’s not the one-off mark, it’s the lessons the student draws from the experience and the feedback – and if that is ‘Yes! I can get away with this!’, or any sense that the key to success is plausible bullshitting, then we do have a problem. The idea of general survey courses and relatively bland essay assessments in the early years of a programme is that these build the foundations for more advanced and detailed studies in later years. *We* can see how these AI outputs aren’t very good; how do we make sure that our students are trained in the same analytical skills, and can evaluate their own work better?

Well, one possibility is to get the AI to help us. One way – perhaps the only way – for students to develop their critical skills is to practice them on real material, but that can be tricky; real published material can be too good and hence intimidating, peer review never works because, understandably, they pull their punches, and they all hate it. Examples of past work can be useful – but my experience here is mixed, as there tend to be too many different things going on at once, whereas what we want to focus on is taking apart the argument.

And suddenly we have a means of generating arguments that are eminently worth a good kicking – superficially plausible, actually vacuous – without the distractions of poor grammar, spelling or expression. And, leaving aside its reaction to being caught out in self-contradiction and inconsistency, the author doesn’t mind; possibly it even welcomes the opportunity to improve.

I was all set to try this out today with my Greek Political Thought class, as the assessment involve revising a draft essay in response to feedback so this could be a way to organise discussion about processes of revision. But only three students turned up, and we talked about a load of other stuff instead. I haven’t decided whether to make the experiment on Thursday, with my much larger – well, theoretically much larger; second-to-last day of term with rail strikes and possible snow doesn’t promise much – but if I do, I’ll report back here.

And, look, I have got a blog post out of ChatGPT, as have a load of other people – just not quite in the way they imagined.

Update: twelve hours later, the potential of Greek Political Thought -> ChatGPT dawns on me. It’s been a long term… How could I have missed this opportunity?

Appendix: my other attempt at asking ChatGPT to write blog posts for me – in this case I didn’t ask it to try to imitate my style, but this actually manages to sound a little more like me than the one quoted above where I did…

Write a blog post about how people misquote Thucydides.

Misquoting Thucydides is a common occurrence in the world of ancient Greek literature. The Athenian historian and general who wrote the famous work, The History of the Peloponnesian War, has had his words misused, misinterpreted, and misquoted countless times throughout history.

One of the most common misquotes of Thucydides is “The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” While this phrase is often attributed to Thucydides, it is actually a misquote of a line from his work. The actual line is “The strong do what they will, and the weak suffer what they must.” This small change makes a big difference as the misquote implies that the strong will always dominate the weak, whereas the original line implies that the weak may have no choice but to accept the power of the strong.

Another misquoted line from Thucydides is “In a democracy, the people get the government they deserve.” Again, this is a misquote of the original line, which is “In a democracy, the government is responsible to the people.” This misquote implies that people are responsible for the government they get, whereas the original line implies that the government is responsible to the people.

Finally, another misquoted line from Thucydides is “The only good is knowledge and the only evil is ignorance.” This misquote implies that knowledge is the only good and that ignorance is the only evil. The original line is “The only good is knowledge and the only evil is not to know.” This line implies that knowledge is good and that not knowing is the only evil.

Misquoting Thucydides is a common occurrence due to the complexity of his language and the fact that many of his lines are open to interpretation. It is important to remember the original words of Thucydides when quoting him in order to give his work the credit it deserves.

Yeah, right. It is to be noted that one of the three examples given is seriously arguable (not to mention the AI’s conviction that there is A correct version of Thucydides in English) while the other two have nothing at all to do with Thucydides but it insists on correcting them with reference to Thucydides’ text anyway…

December 6, 2022

Measure of a Man

It’s been a quiet fortnight on Thucydides Twitter – if you discount the 2000-odd P.G. Wodehouse bots continuing to pump out incomprehensible adverts for something that may or may not be linked to World Cup betting. The Social Jukebox bots that used to offer dodgy quotations have vanished, either because they’ve been closed down or because they decided that Space Karen’s far-right takeover was bad for their image; one weight-lifting account announced that ‘We need a President who lifts’, with the inevitable result of a couple of people bringing out the ‘Scholars and Warriors’ quote, and a couple of far-right and/or bot provocateur accounts with Thucydides handles have been churning out ghastliness, but that’s about it – with one minor but interesting exception.

“Man is the most important thing, and everything else is the fruit of man’s labor.” Huh? Vaguely reminiscent of Protagoras rather than Thucydides. Very few results from a google search – but one of them looks like a very likely source: a translation of a Chinese article on ‘The Basis of Human Rights in Early Ancient Greek philosophy’ by one Bo Zhenfeng. This indicates that these are supposedly the words of Pericles, but the reference is to a Chinese translation by Xie Defeng, published in Beijing in 1960 – and, massively unhelpfully, the citation is a page reference in that edition, rather than a specific point in Thucydides’ text. Obviously it’s interesting to have confirmation of the existence of at least one such translation into Chinese…

…but it does leave me having to guess which bit of T. has been translated in this manner. I must admit this had me completely stumped, after reading through the three speeches of Pericles in Crawley, Hammond and Mynott – plenty of mention of ‘men’ in different contexts, but nothing that really fits that statement. So, I resorted to sending out a plea to colleagues with relevant knowledge and expertise, and the answer came promptly back from Dr Guo Zilong at the Institute for the History of Ancient Civilisations in Changchun, via Sven Günther.

It turns out that Xie’s translation was based on Rex Warner’s Penguin Classics version – and that this is one of the points where Warner gets distinctly imaginative. 1.143.5, towards the end of Pericles’ first speech, where he’s assuring the Athenians that there is no real risk to them in going to war with Sparta. I’d looked at this phrase, and thought, nah, not close enough. Crawley has “We must cry not over the loss of houses and land but of men’s lives; since houses and land do not gain men, but men them.” Hammond: “Property is the product, not the producer of men.” Mynott: “Men give us these possessions, the possessions do not give us men.” Warner: “Men come first, the rest is the fruit of their labour.”

Yes, the underling point is in the same general ballpark, but Warner is quite a long way from the Greek; it’s one of Thucydides’ neat little phrases (actually one of the neatest I know), literally “not these things (nom.) men (acc.), but men (nom.) these things (acc.) procure/supply/get”. “Men come first” is an interpretation or gloss, rather than a translation; and “man is the most important thing” – assuming for the moment that this is what Xie’s translation says, rather than being the rest of the translation of Bo’s essay into English – is a step further away, as it shifts from Warner’s sense that this is partly about chronological precedence (men, who then created things) to an idea of a hierarchy of importance alone (men, who are more important than things).

Positively, this gives me a little more knowledge of the reception history of Thucydides in China; someone thought it worthwhile to translate Warner’s translation within six years of its publication. Incidentally, it was Xie’s translation that dispensed with chapters, rather than an issue with Bo’s citation practice…

November 18, 2022

Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots

Something even weirder than normal is happening on Thucydides Twitter. I hesitate to use the word ‘invasion’ because of its association with the UK government’s racist anti-migrant rhetoric, but certainly I feel like a scientist in the opening act of one of those movies, puzzled by the suddenly anomalous behaviour of the pond snails he’s been studying, not realising that this is just one small segment of a rapid montage, the dots that will not be joined by anyone except the viewer until Act Two…

For the last week, the results of my regular searches for mentions of ‘Thucydides’ – mainly but not solely for the purpose of correcting misattributions and misquotations – has been dominated by a lot of very similar and very puzzling tweets, along these lines: fragments of unknown text mentioning Thucydides but not actually making any sense, with the main event being short videos that simply flash up incomprehensible phrases.

The user handles of the tweeting accounts are long strings of Chinese or (I think) sometimes Korean characters, neither of which I read, and the avatars follow the same pattern, so initially I thought this was the work of just a couple of them, tweeting in rapid succession. However, a couple of days ago I got sick of them clogging my feed and started deploying the Mute button – and discovered that they were actually all different, but all tweeting the same things. One day I muted 35, the next 37. Many of the user names are classic bot names – @sandra165356898654 – though some look on the face of it more like real people; they’ve all been created in the last few weeks, and one can only conclude that Space Karen’s attempts at expelling spambots from the platform are experiencing a certain lack of success…

Why are they here? It is not, I think, about the bits of English text in themselves. The fragments relating to Thucydides (taken, as I’ll discuss below, from an obscure early P.G. Wodehouse story, of all things) don’t convey any coherent message; if you look at the full feed of one of these bots, it is not (as I initially wondered) tweeting successive extracts from a single text, but rather entirely disconnected fragments from heaven knows where. My guess is that they simply require some text – maybe even specifically English text – to be recognised as a legitimate tweet, or to be permitted to tweet stuff on a metronomic basis, since each tweet will be different. Others who properly understand this stuff may be able to clarify; I believe there are currently a lot of former Twitter software engineers with a bit of time on their hands.

So, Thucydides – and the contents of non-Thucydides tweets from the same bots – is not the point. Presumably advertising is – but what? I’ve tried running some of the other text through Google Translate, and it mostly declares itself baffled. There are hashtags relating to FIFA and to cryptocurrency and NFTs and to online games, and links to websites which mostly either can’t be found or my web browser screams with terror at the thought of visiting, but one of which seemed to be about basketball. Is this all about sports betting? Anyone any idea? Who would actually see these tweets if they weren’t searching for ‘Thucydides’ (which is, I believe, something of a minority pursuit)?

The joyous aspect of this whole thing – yes, this may be less important than possible evidence of demons in the internet – is the discovery of a previously unknown source for Thucydides reception. The text being mined by the bot engine is an early story by P.G. Wodehouse, ‘A Shocking Affair’, first published in 1903 in his collection of school stories Tales of St Austin’s. Now, I will admit to having quite enjoyed some of Anthony Buckeridge’s Jennings and Darbishire books in my childhood, in the days when I had the leisure to read voraciously and indiscriminately, but mostly I find the genre tedious if not downright sinister, and the idea that it was once massively popular among adult readers is frankly rather alarming. We can all feel very relieved that Wodehouse decided he wasn’t particularly good at at, and turned to comic fiction instead.

‘A Shocking Affair’ focuses on a cunning wheeze to get out of a Greek exam without getting into trouble. The boy Bradshaw fails to turn up, but is later heard behind the door of the school’s science museum, the handle of which has somehow become charged with electricity; two masters get a shock trying to open it, a third uses a piece of paper to insulate himself; Bradshaw is excused for not being able to get out, and later admits that of course he knew that paper doesn’t conduct electricity; the narrator reflects that he has had to endure the exam but on the other hand got to see the masters getting shocked.

If Bradshaw had not been in the Museum, he might have seen Gerard jump six feet, which would have made him happy for weeks. On second thoughts, though, that does not work out quite right, for if Bradshaw had not been in the Museum, Gerard would not have jumped at all. No, better put it this way. I was virtuous, and I had the pleasure of witnessing the sight I have referred to. But then there was the Thucydides paper, which Bradshaw missed but which I did not. No. On consideration, the moral of this story shall be withdrawn and submitted to a committee of experts. Perhaps they will be able to say what it is.

The story is basically terrible, and I recommend it to nobody unless you really like that sort of thing. To be fair, Wodehouse also thought it was a failure. But it does offer evidence for the teaching of Thucydides in English private schools at the end of the 19th century.

Our form read two authors a term, one Latin and one Greek. It was the Greek that we feared most. Mellish [the classics teacher] had a sort of genius for picking out absolutely untranslatable passages, and desiring us (in print) to render the same with full notes. This term the book had been Thucydides, Book II., with regard to which I may echo the words of a certain critic when called upon to give his candid opinion of a friend’s first novel, “I dare not say what I think about that book.”

It’s not just Thucydides, it’s the fact that Mellish goes out of his way to make the end-of-term exam as difficult as possible, that leads Bradshaw to adopt an alternative approach to the night-before-the-exam cramming.

“Bradshaw,” I said, as I reached page 103 without having read a line, “do you know any likely bits?”

Bradshaw looked up from his book. He was attempting to get a general idea of Thucydides’ style by reading Pickwick.

“What?” he said.

I obliged with a repetition of my remark.

“Likely bits? Oh, you mean for the Thucydides. I don’t know. Mellish never sets the bits any decent ordinary individual would set. I should take my chance if I were you.”

“What are you going to do?”

“I’m going to read Pickwick. Thicksides doesn’t come within a mile of it.”

Is this the earliest recorded instance of someone mocking the unpronounceability of Thucydides’ name? It’s not the best attempt I’ve seen. The description of the exam does offer a few hints of Wodehouse’s mature style – the voice of Bertie Wooster is faintly discernible.

Now I have remarked already that I dare not say what I think of Thucydides, Book II. How then shall I frame my opinion of that examination paper? It was Thucydides, Book II., with the few easy parts left out. It was Thucydides, Book II., with special home-made difficulties added. It was—well, in its way it was a masterpiece. Without going into details,—I dislike sensational and realistic writing,—I may say that I personally was not one of those who required an extra ten minutes to finish their papers, I finished mine at half-past two, and amused myself for the remaining hour and a half by writing neatly on several sheets of foolscap exactly what I thought of Mr Mellish, and precisely what I hoped would happen to him some day. It was grateful and comforting.

I am strongly inclined to think that Wodehouse had actually studied some Thucydides, not so much from this passage as from the remark he attributes to one of the class ‘swots’, who afterwards “wanted to know whether I had adopted Rutherford’s emendation in preference to the old reading in Question 11.” That is a pretty obscure reference, even in 1903, to an 1890 edition of Book IV by the headmaster of Winchester College. Jeeves would certainly have had an opinion on the subject – probably favouring Spratt.

Update: as is my usual practice, I’ve been gradually writing this post in odd moments over the course of a couple of days, feeling reasonably happy that Twitter wasn’t going to collapse before I finished it; I accelerated the pace this morning, as imminent collapse started to feel like a non-zero possibility, and here it is. BUT THE BOTS HAVE ALL VANISHED. Nothing since yesterday morning. Is this when they make their move?

Update: obviously they’ve just started mining a different text. And a couple of new quotes of Wodehouse have just appeared.

November 16, 2022

The Roman Thing

The History of Ancient Rome, Definitively De-Woked; free from excessive emphasis on imperialism, colonialism and class struggle.

Rome must be considered one of the most successful things in history. In the course of centuries Rome grew from a small town on the Tiber River into a vast thing that ultimately embraced England, all of continental Europe west of the Rhine and south of the Danube, most of Asia west of the Euphrates, northern Africa, and the islands of the Mediterranean. Unlike the Greeks, who excelled in intellectual and artistic endeavours, the Romans achieved greatness in their doing stuff, political, and social institutions. Roman society, during the republic, was governed by a strong doing stuff ethos. While this helps to explain the incessant stuff, it does not account for Rome’s success as a thing. Unlike Greek city-states, which excluded foreigners from political participation, Rome from its beginning incorporated some people into its social and political system. Allies and some people who adopted Roman ways were eventually granted Roman citizenship. During the principate, the seats in the Senate and even the throne were occupied by persons from the Mediterranean realm outside Italy [check w. editor-in-chief: does this still sound a bit EDI?] The lasting effects of Roman stuff in Europe can be seen in the geographic distribution of the Romance languages (Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Romanian), all of which evolved from Latin, the language of the Romans.

Origins of Rome

As legend has it, Rome was founded in 753 B.C. by Romulus and Remus, twin sons of Mars, the god of stuff. Left to drown in a basket on the Tiber by a king of nearby Alba Longa and rescued by a she-wolf, the twins lived to found their own city on the river’s banks in 753 B.C. After arguing with his brother, Romulus became the first king of Rome, which is named for him. A line of other kings followed in a non-hereditary succession.

Rome’s era as a monarchy ended in 509 B.C. with the overthrow of its seventh king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, whom ancient historians attempted to cancel by spreading unfounded gossip. A popular uprising was said to have arisen over the rape [HA! No trigger warning! Take that, snowflakes!] of a virtuous noblewoman, Lucretia, by the king’s son. Whatever the cause, Rome turned from a monarchy into a republic, a world derived from res publica, or “property of the people”, but the historian Polybius suggests that it was more like a constitutional monarchy, as it should be.

The Early Republic

The power of the monarch passed to two magistrates called consuls. They also served as commanders-in-chief of the army. The magistrates, elected by the ordinary folk, were drawn largely from the Senate, which was dominated by the right sort of people. Politics in the early republic was marked by the long discussion between decent chaps and the salt of the earth, who eventually attained some political power through years of benevolent reform by their superiors.

Expansion of Stuff

During the early republic, the Roman state grew exponentially in both size and things. Though the ancestors of the French sacked and burned Rome in 390 B.C., the Romans rebounded, eventually becoming loved by the entire Italian peninsula by 264 B.C. Rome then did some stuff known as the Punic Things with Carthage, a powerful city-state in Northern Africa, but not actually Africans so don’t worry about that. The first two Punic Things ended with Rome hanging around Sicily, the western Mediterranean and much of Spain. In the Third Punic Thing (149–146 B.C.), the Romans visited the city of Carthage and sent its surviving inhabitants on holiday, making a section of northern Africa a Roman thing. At the same time, Rome also spread its influence east, arguing with King Philip V of Macedonia in the Macedonian Wars and turning his kingdom into another Roman thing.

Rome’s doing stuff led directly to coincided with its cultural growth as a society, as the Romans benefited greatly from contact with such advanced cultures as the Greeks and nicking their art. The first Roman literature appeared around 240 B.C., with translations of Greek classics into Latin; Romans would eventually adopt much of Greek art, philosophy and religion.

Internal Discussions in the Late Republic

Rome’s complex political institutions began to age gracefully under the weight of the growing thing, ushering in an era of committed debate. The relationship between decent chaps and the salt of the earth developed as the true custodians of the countryside sought to maintain rural customs on the public land, while access to government was increasingly limited to the decent sort. Attempts to address ungrateful grumbling from woke culture warriors, such as the reform movements of Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, ended in the reformers’ withdrawal from public life in embarrassment.

Gaius Marius, a grammar school scholarship boy whose prowess in doing stuff elevated him to the position of consul, was the first of a series of entrepreneurs who would be important in Rome during the late republic. By 91 B.C., Marius was exchanging views with other people, including his fellow entrepreneur Sulla, who emerged as an inspiring role model around 82 B.C. After Sulla retired, one of his former supporters, Pompey, briefly served as consul before doing some successful stuff in the Eastern Mediterranean. During this same period, Marcus Tullius Cicero, elected consul in 63 B.C., famously resisted the cancellation campaign of Cataline, who always seemed a bit dodgy, and won a reputation as one of Rome’s greatest orators…

November 14, 2022

Say Hello, Wave Goodbye

he hand on the arm (or in this case the naked calf): affectionate, reassuring – or restraining, controlling, possessive? The expression that we can see on the face of the hand’s owner (the other face is turned away from us and invisible): peaceful and content, or smugly arrogant, or both? The juxtaposition of naked and clothed bodies inevitably raises questions of power, of different kinds – which of course doesn’t preclude affection, or love, but it undoubtedly complicates it. And we observe the scene, and wonder what’s going on, and what the painter thought was going on and intended us to see.

Well, not according to whoever wrote the captions for the Lucian Freud exhibition currently at the National Gallery. This was one of the highlights of a rare weekend in London, mostly focused on jazz concerts. I love Freud’s art, and they had all my favourites (including the one of QEII, which feels even more magnificent and Velazquezian now its subject has died, and still hilarious although presumably the original outrage will rapidly disappear; I just wish it had been a full-scale Portrait including some corgis). But I am still feeling aggravated by the dogmatism of some of the labels, especially the insistence that Two Men (1988) is simply a picture of affection, nothing else to see here.

Do people just not like complexity any more? The National Galleries Scotland webpage for the picture talks of “underlying tension” in an apparently peaceful scene, which seems more reasonable, but I’d prefer to go with ambiguity – not least, the possibility that in sleep both men are revealing feelings or instincts that they might not admit even to themselves, the touch, the expression, turning away. And of course fbis is the artist’s interpretation, or extrapolation, or projection, rather than ‘reality’.

Okay, I do tend to be a bit obsessive about the idea of deliberate ambiguity and undecidability in artistic creations, as the core of my reading of Thucydides in contrast to interpretations that insist that this time the true objective intent of his narrative has been identified. And, to be fair, I assume the job of an exhibition curator is partly to come up with something new to say, breaking away from the well-established “he was a cold-hearted bastard who looked into his subjects’ souls” school of Freud criticism (admittedly an interpretation that he himself deliberately invites in some of his work). “Nothing awkward or psychological to see here, just admire the brush technique and move along” is certainly new; I guess I would just prefer to see it raised as another possibility rather than asserted as truth…

November 6, 2022

Based (How Low Can You Go)

If Elon Musk is going to destroy the Bird Site, inadvertently or not – the reported wheeze that everyone will get a timeline prioritising tweets from $8/month ‘verified’ users suggests he doesn’t have the faintest idea what makes it great for many people – I am hoping that he either takes his time (couple of years, say) or gets it over with in the next couple of weeks. I have a chapter forthcoming, at some point in the next year or so, exploring references to Thucydides on Twitter both as a window onto his image in contemporary culture and as a snapshot of the dynamics of social media. It would be nice if Twitter retained something of its current significance when the chapter appears – or, I urgently need to rewrite some sections substantially before the book goes to press, to explain why anyone thought this stuff was worth worrying about back in 2019…

This past week has been very much a matter of “you don’t know what you’ve got ‘til some pampered egomaniac has stomped all over it and it’s gone’. There is a serious question as to how far Twitter just suits my purposes in several overlapping ways and how far my behaviour has adapted to take advantage of what it has to offer, but either way there’s no obvious alternative that covers all the bases, leaving aside the fact that my rather elderly iPad refuses now to run the apps for either Facebook or Mastodon.

Mastodon Social, where I am establishing a foothold (come up and see me at @NevilleMorley@mastodon.social), seems a reasonable possibility for replicating the ‘interesting chats with relatively bounded community of like-minded people’ element. Granted, it’s currently suffering from slowness and clunkiness and a confusing structure, so it’s going to take a while to reconstruct any semblance of my current Twitter circle – a powerful reminder of both sunk costs (the years it took to work out who I wanted to talk to, who I wanted to listen to and how to filter out a lot of others) and network effects (trying to find those people again, and being unsure whether they’ve not migrated to Mastodon or it’s just that the search function is a bit erratic). I can’t see any equivalent of Lists, which, filtered via Tweetdeck, were a wonderful means of managing different sorts of groups and conversations. In this respect, Mastodon seems more like it could be a cosier, less evil version of Facebook.

But one of the great things about Twitter has been the serendipity. Follow a decent number of interesting people, and you don’t just learn from their expertise, you encounter whatever they happen to find interesting from the people they follow. Network effects again; this time, not so much the pull of networks that have the ‘right’ people in them so you don’t want to leave as the pull of networks that have sheer scale on their side, so you’re more likely to connect to something you didn’t know you needed. For example: I would never have sought out a Eurovision community, but a chance retweet by a fellow classicist introduced me to the work of a historian of the ESC, Catherine Baker, and that’s now an annual thing – and, no, she doesn’t seem to be on Mastodon yet.

Still more than this: search regularly for ‘Thucydides’ and you get an illuminatingly random sample of what’s going on in some of the wackier regions of the Internet: over-excited fans of a very minor Korean pop act, lots of new age motivational trainers, conspiracy theorists, insecure body-builders and cryptocurrency obsessives. One of the theories that I need to find time to investigate fully – having finally extracted approval from the faculty research ethics committee after eighteen months of discussion – is that there is a significant correlation between people who call themselves ‘@Thucydides431BC’ and far-right views. Certainly it’s been an education – an endurable snapshot of that area of social media, like following someone I was at college with who’s become a Brexity UKIP-adjacent loon, whereas exploring this stuff in depth would rapidly lead to madness and despair.

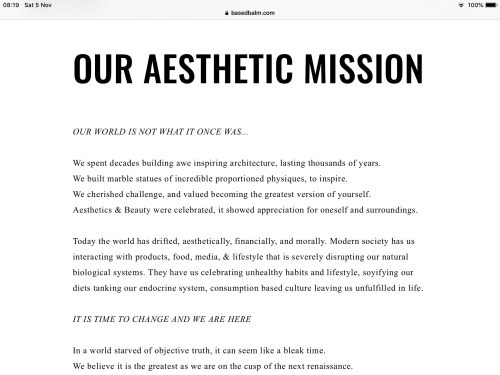

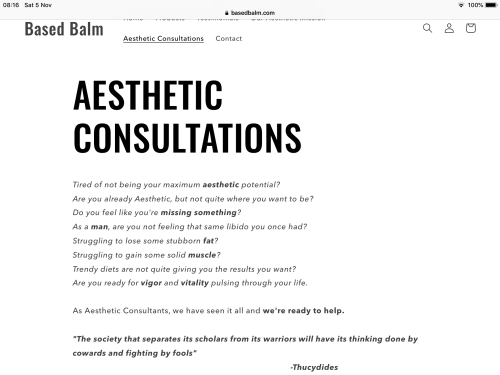

And occasionally the streams cross, in a truly glorious manner. Based Balm’s aesthetic consultations; Thucydides wants you to combat cultural decadence and the decline of traditional masculinity by buying skincare products. Honestly, I don’t think a paraphrase can do justice to this website…

Confident. Abundant. Based. Vril. No, I don’t know if that’s a Bulwer-Lytton reference, or their spelling is as terrible as their fact-checking. Be more Vril.

Part of the advertised attraction of Mastodon is that it’s free from this sort of nonsense – the entry barriers are probably rather high for MAGA trolls and people advertising Jordan Peterson-esque beauty products. That can risk becoming an echo chamber in the bad sense. I have yet to find anyone on Mastodon misattributing quotes to Thucydides; this is both a positive and a negative thing…. So, no, I am probably not going to quit Twitter completely just yet, or at any rate the Thucydiocy Bot isn’t; it’s interesting to note that, while @NevilleMorley‘s follower count has diminished significantly in the last week, @Thucydiocy’s has been going up.

October 23, 2022

You Should Hear How She Talks About You

I seem to have been writing quite a lot of confidential reviews lately, of article submissions, grant applications and cases for promotion (way to make almost everyone a little bit paranoid…), and so I was intrigued by the news that a journal in the sciences, eLife, has decided to abandon the tradition of acceptance/rejection on the basis of peer review (see announcement here). If an editor decides that a submission is worth sending out to reviewers, then it will be published, together with the reviews.

To be honest, I’m not sure what problem this is supposed to be solving; if one were really cynical, one might think that it’s all about the financial interests of a journal with substantial APCs wanting to maximise the number of articles published – ker-ching! – while maintaining the quality claim that everything is peer reviewed. At the same time, while Reviewer 2 is thus robbed of the power to put the boot in anonymously, there is still an unaccountable gate-keeping stage, vested in the editor. Reviewers are still going to have to be found, and persuaded to offer free labour, which is one of the more obvious problems with the present system; is there some idea that published reviews will count as publications and hence are more worthwhile? This does seem to be the assumption – the work put into peer review should be public and acknowledged, which will make reviewers feel better about it.

Hmm. I’ve had some bruising experiences with apparently ignorant, stupid or downright hostile reviewers over the years, so part of me completely understands the wish to force the bastards to own up to their wrecking activities or tone them down. But thinking as a reviewer – not usually hostile, though I suppose my ignorance and stupidity are always up for debate – I can see problems.

Most obviously, I have benefitted from the constructive comments and suggestions of reviewers as well as ground my teeth over their criticisms, being able to improve the final product as a result, and certainly that’s how I try to write reviews. Is the idea now that there would no longer be a revision stage, but submissions would simply be published as submitted together with the reviewers’ critical comments that the author might really have wished to incorporate (or even, conceivably, withdraw the paper)? If the submission can be revised, do the reviews get published as submitted (so that they appear to miss the point by criticising things that are no longer there) or does the reviewer have to write a new review (more work, clear disincentive to take on task in the first place)?

(This may all be very science-focused in practice, given the emphasis in the announcement on pre-prints; in other words, authors are publishing their papers anyway, it’s just a matter of the imprimatur of a journal. But given how far everything else, not least issues around Open Access, gets driven by developments on the science side of things, that doesn’t mean it’s irrelevant to us).

There’s also a question of audience, and hence appropriate content and style – not of the article, but of the review. I address reviews to the editor or funding body that’s asked me to do them, but with a powerful sense that the author is just as important if not more so; they’re the one who might find the comments most useful, after all, and the one who’s going to be hurt and infuriated – and I suppose that one of my aims is not just to be fair but to convey this in such a way that in six months’ time they might grudgingly admit that Reviewer 2 did actually have a point and the work is better as a result.

One consequence is that, I suspect, my reviews might seem to a less involved reader to be both too pedantic (because they have to deal with all the detail as well as the overall argument) and too vague (because I’m writing for people, author and editor or funding panel, who also know the submission very well). A review written to be published would be significantly different; needing to spell more out, needing to leave out the detail (or at least putting it at the end in tiny font in the way some Classical Review reviews do).

And, worse, it becomes a performance. The great thing about the anonymous review is that it is not about me, but about putting my expertise to the service of the journal, the funders and the author. The moment that ego intrudes, that I feel any inclination to explain how the author should have framed their topic, or any irritation that they haven’t cited Morley 2013, I know I need to be very careful – those might be valid criticisms, but they shouldn’t be made just because that’s how I feel. Put another way: at least for the author, the review needs to be credible on its own merits, not on the basis of the authority behind it. On reflection, my reviews are probably easily recognisable because if I suggest that the author should have consulted Morley 2013, I’ll include a paragraph’s worth of explanation of why this really is a source worth considering…

An open, published review means I have to stand by my criticisms, true; but it also means my comments will be interpreted by others in relation to me as their author, not just in their own right, regardless of how they were intended. I can easily imagine then not writing certain things because of the possibility or likelihood that these would be seen as personally motivated, because the review will reflect on me – and maybe some of those things really shouldn’t be said, but I don’t think that is universally true. As I commented on the Twitter, my concern about removing accept/reject and publishing the reviews is not that we’ll be overwhelmed with a flood of rubbish, but that we’ll be faced with unceasing flame wars and social media feuds.

I don’t think I have ever written anything in a review that I would not have offered as feedback to a graduate student or colleague – okay, maybe with some slight adjustments in tone. It would certainly affect my approach to a review if I knew the author would know my identity, but, I hope, not too much. The issue with the open review is that it’s not just deanonymised but public; not me having a private exchange or chat with student or colleague to say, look, I really don’t think your argument makes any sense, but me standing up in a research seminar to say it. (Yes, I know there are people who do that too – I was a student ar Cambridge under Keith Hopkins…).

“If you can’t say anything nice, don’t say anything at all” is a faulty principle for scholarship in general. Academics may, as a rule, be hyper-self-critical, but not necessarily in the right ways; we do need people to suggest that we’re going wrong in ways we haven’t noticed – and quite possibly non-friends will be better at this than the sort of people we might ask for feedback. That’s obvious for graduate students, but I think it applies more generally, and that surely means there is a place for private if not necessarily anonymous reviews, rather than everything being about the public performance of reviewing, critical or otherwise.

I have written a few responses to articles, and it can be very rewarding – the emphasis on responses to pieces as much as on the pieces themselves is one of the great things about Epoiesen, for example – but these are completely different things from reviews. More responses, more publications focused on dialogue, would be great; but it really doesn’t look like a solution to problems of journal gate-keeping and peer review. The worst system, apart from all the others..?

October 11, 2022

The One and Only

Our regular comfort rewatching of Buffy the Vampire Slayer is ar a fairly early stage, but there have been times over the last week and a half, with another bout of COVID now turning into a lingering cold colliding with the second week of teaching and the final stages of putting together a project funding application, when I have been powerfully reminded of Buffy’s Mom’s response to discovering her secret. Specifically, because the dynamic rather echoes my wife’s response to my behaviour whenever I’m illl. “Have you tried not being a Vampire Slayer?” Sorry, I am always going to be an academic. “Well, I just don’t accept that.”

Obviously I am not unique or irreplaceable, the only one in all the world with the power to write meandering articles about Thucydidean reception. If you cut me down, scores of young academics would rise up to fight one another to take my place, and would probably do a much better job. But the reason – discounting egomania – why academics in general (in other words, me) are terrible at being ill and even more terrible at taking the time to recover properly is that, in the short term, stuff really isn’t going to get done if we’re not there to do it.

That is to say: lots of people could do an equally good job at delivering a module on Greek Political Thought, but they’re not going to be able to deliver my Tuesday seminar at two days’ notice, and certainly it’s not something that another member of the department could be expected to take on – so, if I don’t do it, the seminar has to be rescheduled (apparently more of less impossible these days, even or especially with timetabling software) or simply cancelled. Lots of people could write a persuasive research funding proposal, but they’re not going to be able to step in and take over this specific funding proposal a week before the submission deadline; if I don’t spend several days arguing with finance people, it just doesn’t happen. (Of course, from the perspective of the finance people, this may be a desirable outcome).

Some things can fall by the wayside without any issue: plenty of meetings will be fine without my lugubrious presence and occasional long-winded interventions, plenty of emails will effectively resolve themselves if ignored. My approach to being ill is to do the stuff that has to be done and really can’t be done by anyone else, whereas as far as my wife is concerned, this is a meaningless category and just a symptom of control freakery and/or workaholism.

Obviously the most significant impact of all this is the damage to my sense of humour. Self-involved much?

September 29, 2022

Here We Go Again

Events of the present and future will tend to resemble those of the past – or however else you want to paraphrase Thucydides’ key assumption about the usefulness of his work – or at any rate will remind us of them. This week has been very much a case in point, as commentators have looked back to previous disastrous budgets and currency crises in search of a bit of historical context and/or a yardstick for evaluating disastrousness for the present Kwartastrophic Trussterfuck. I’ve been thinking a bit about my early childhood in the early 1970s (and how much this may have influenced my current instincts to preserve vegetables and hoard firewood), but even more my thoughts have turned to the Greek economic crisis, prompted by the wonderfully Thucydidean phrase used by someone from Nomura finance in the early stage of the pound’s collapse, “hope is not a strategy”. Yes, it’s the Melian Dialogue redividus, once again pitting the Batshit Brexit Party against another inexorable facet of reality.

“Hope is not a strategy” is not actually an echt Thucydides quote, not least because of the anachronism of ‘strategy’ (the word may derive from the Greek strategeia, matters pertaining to the activities of the strategos, but they didn’t develop anything like our modern concept). It is, however, a pretty well perfect epitome, in modern terms, of what Thucydides does write: Hope is a fine comfort in danger, but in the absence of military strength or resources or friends a belief that things might turn out okay is scarcely adequate, and if you rely solely on it you will quickly face disaster.

This was the first time I’d actually come across the phrase, at least as far as I recall, but I quickly realised that it’s not new; there are several books that use it for their title, it regularly features in discussions of business practice, and Rudy Giuliani used it in a speech to disparage Barack Obama’s optimistic vision for the United States. One website suggested that it’s substantially older than that, a phrase that regularly appears in mid-C20 discussions of military strategy – which then raises the possibility that it actually originated as a paraphrase of Thucydides in some professional military context! Something else for the ‘must get round to researching this properly at some point’ list…

It’s always worth stressing that, in the original Melian Dialogue, we’re presented with competing claims about reality: the Athenians seek to present themselves as an inexorable force of nature, so to speak, against which it is pointless to struggle; the Melians refuse to accept this, and their only hope of a positive outcome is to persuade the Athenians to drop the idea as well (or, admit that they never really believed it). The dynamic of the dialogue, from the reader’s perspective, is surely affected by whether you think there is legitimate doubt as to whether the Athenians are bluffing or over-confident, or whether you see the stronger power as genuinely unbeatable, either because you accept the Athenian assertion (hello there, crude IR Realism!) or because you substitute a genuinely unbeatable force, e.g. climate change as in my Do What You Must project.

Insofar as the Greek financial crisis was focused on negotiations between the government and the ‘Troika’ of IMF, ECB and European Commission, with the latter group unable simply to impose their will without compelling the consent of the former, that was a ‘legitimate doubt’ situation; the ‘Melians’ might hope, not completely unreasonably, to extract concessions because of the ‘Athenians’’ concern about the consequences if agreement was not reached. The UK government is at present trying to challenge the markets, which, at a global level, are really not going to suffer whatever happens (worrying about global contagion is someone else’s problem). You don’t negotiate with markets; you offer sacrifices to them.

There’s also the lack of a clear end point to the situation; since this is not a negotiation about clear demands, even ‘surrendering’ doesn’t necessarily solve the problem – it’s a matter of how many concessions have to be made before the markets decide to feel reassured, or turn their attention to another victim. Insofar as we see the Melian Dialogue as a study in negotiation, it’s pretty well irrelevant here; if we read it as a study of possible responses to a situation of pronounced inferiority, it’s hugely to the point…

Final thing to note. The Greek government could plausibly claim to be representing the Greek people, and clearly deployed this as part of their negotiating tactics. The British government clearly is the Melians, a small group of unrepresentative oligarchs not answerable to anyone else, selling their country down the river because of their own ideological obsessions…

September 21, 2022

Friends Will Be Friends

Okay, this is a first for me; I’ve just produced a new episode of the Thucydiocy podcast (Podbean link here; iTunes always takes longer to process), without it being based on a previous blog post. As I tend to use the blog as a repository in case I need to check up on misattributions and misquotations, this is potentially slightly tricky, and so I thought I should simply add a rough transcript (or rather, an expanded version of my script notes) for future reference…

There’s a very entertaining piece in a recent issue of the London Review of Books by Colin Burrow, reviewing The New Yale Book of Quotations in typical LRB style – that is, offering general thoughts on the general topic, with the book itself playing second fiddle. Given how much time I spend dealing with Thucydides misquotations and misattributions, I really liked this comment:

Books of quotations are no longer sources of things you might want to say or cite – after all, you can Google and copy and paste as much of that text stuff as you like – but have become in effect books of anti-misquotations (though don’t expect to see that word on a title page any time soon). Their main function is to tell you who didn’t quite say what.

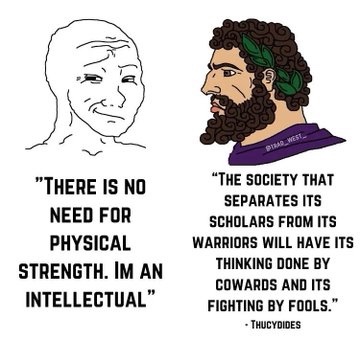

Well, this podcast, and the Thucydiocy Bot, are very much in the business of anti-misquotation – and, given the absolute plague of ‘Scholars and Warriors’ misattribution on the Twitter in recent weeks, as people keep sharing one of those stupid shitposting wojak versus Mediterranean memes (reproduced below, as I don’t think anyone is seriously going to admit to creating it), I really wish I’d known about the new edition of the Yale thing, as I could have lobbied them to include it. In fact their T offering is very disappointing; the first edition had just three quotes, none of them terribly obvious or famous – and cited as e.g. ‘Book 2 Chapter 4’, a sure sign that they’re relying on Crawley’s translation – and the new edition just reproduces them. I mean, that’s the same number as Bono gets (also not the most obvious choice). Judith Butler gets one; William F. Butler gets nothing…

Anyway, what I wanted to discuss in this episode is not misattributed quotations but mangled ones – not ‘T didn’t say that’ so much as ‘T didn’t mean that’. Granted, this could be said of half the regular attempts at invoking T, e.g. implying that views of Athenians in the Melian D are his own ideas, but this is a slightly more technical category, where the quotation is translated in an unexpected or arguable manner, and/or removed completely from its original context, in a way that means I have to spend some time just to work out whether or not it might be genuine, and if so where it comes from. Interestingly, two examples appeared on Twitter just the other week in close succession..

“Anyone who, in pursuing the highest goals, tolerates envy has the right priorities.” Huh? Didn’t recognise this at all, but tracked it down relatively easily; it’s Plutarch, towards the end of his essay on how to tell a true friend from a flatterer, in the Penguin Classics version by Robin Waterfield, section 35, and he does indeed name T as his source:

There is also the point that Thucydides makes when he says, ‘Anyone who, in pursuing the highest goals, tolerates envy has the right priorities.’ It is correct for a friend to put up with the hostility his reprimands generate, when crucially important issues are involved. However, if he gets irate at everything, whatever the situation, and relates to his acquaintances as if they were his pupils rather than his friends, then when very important issues arise and he tries to deliver a reprimand, he will be feeble and ineffective – he has used up his candour.

Still doesn’t look a lot like T., and the context doesn’t really help – but another translation offered both a reference, and a version of the quote that was more recognisable; this is Frank Cole Babbitt in the Loeb edition:

Then again, as Thucydides says, ‘Whoever incurs unpopularity over matters of the highest importance, shows a right judgement’; so it is the duty of a friend to accept the odium that comes from giving admonition when matters of importance and of great concern are at stake.

It’s 2.64, Pericles’ final speech, reproaching the Athenians for having become discontented with his leadership, war, plague etc. The preceding comment, in the original, notes that ‘to be hated and unpopular at the time has been the fate of all those who claim power to rule over others’; then, in MartinHammond’s version, ‘if there must be unpopularity, it is best incurred in the pursuit of the greatest aims’, or in Jeremy Mynott’s, ‘the wise decision is to accept the odium in pursuit of the larger purpose.’

Two interesting things going on here. Firstly, Plutarch basically takes quote completely out of context; he takes a questionable claim (‘let them hate us, ‘cos we’re building a massive empire and that’ll shut them in due course’), extracts the bit that looks like a principle of statesmanship, or at any rate the sort of thing would-be statesmen claim to embody, not least because it’s less explicitly self-centred – ‘put up with hostility when you’re pursuing a noble goal’ – and then applies it in an entirely private context.

It’s not what Pericles meant, and it’s certainly not what T. meant. Is the statement assumed to be universally true regardless of context, or that just doesn’t matter? We can be pretty sure P was familiar with whole text, given his use of it in various of his biographies rather than just coming across a quote that suits his purposes . But clearly doesn’t care. Did his readers?

And then the translators, at least in the two instances I’ve seen – the Waterfield even more than the Cole – seem to read the quote as P intended, as a private moral injunction that is directly relevant to the issue of how a true friend should be willing to put up with resentment when he fulfils the duty of ‘frank speech’ in pointing out poor behaviour. It’s as if they haven’t looked at T’s original text to get a sense of the context of the line and the preceding words which would normally shape how we interpret it, and hence to recognise that perhaps it doesn’t fit perfectly, but have translated it in a way that makes perfect sense in the context of Plutarch’s discussion. Put another way; you couldn’t transfer these renditions of T’s quoted works back into Pericles’ speech – it would make no sense at all.

I can see the logic – these are translations of Plutarch quoting T, not of T directly – but it does make T’s phrase even more free-floating and malleable than P was already trying to do.

Second example goes even further in this direction. ‘To keep a feast is nothing more than to do one’s duty.” Not at first sight terribly plausible, and initial searches don’t produce anything in any text of Thucydides – but they do identify a passage from the third-century CE Christian scholar and ascetic Origen, in his famous polemic against a pagan critic of Christianity, the Contra Celsum, 8.21, where he’s opposing the idea that Christians should take part in public feasts in honour of the gods, or demons as Origen thinks of them.

If the so-called public festivals can in no way be shown to accord with the service of God, but may on the contrary be proved to have been devised by man when occasion offered to commemorate some human events, or to set forth certain qualities of water or earth, or the fruits of the earth – in that case, it is clear that those who wish to offer an enlightened worship to the divine being will act according to sound reason, and not take part in the public feasts. For ‘to keep a feast’, as one of the wise men of Greece has well said, ‘is nothing else than to do one’s duty’, and that man truly celebrates a feast who does his duty and prays always, offering up continually bloodless sacrifices in prayer to God.

In one modern edition, that wise man is identified as Thucydides; and searching for key words in Origen’s Greek comes up something resembling the phrase; it’s from 1.70.8, the speech of the Corinthians at the congress at Sparta, describing the Athenians as people who are always active and restless; in Hammond’s translation, ‘their only idea of a holiday is to do what they have to do’. It continues; ‘For them the quiet of inactivity is a greater affliction than the burden of business. It would be a fair summary to say that it is in their nature to have no quiet themselves and to deny quiet to others.’

O’s passage is not an exact quotation of the original; whereas T has μήτε ἑορτὴν ἄλλοτι ἡγεῖσθαι ἢ τὸ τὰ δέοντα πρᾶξαι – they do not consider a festival as anything other than doing what is necessary – O has Ἑορτὴ” γάρ, ὥς φησι τὶς καὶ τῶν ἑλληνικῶν σοφῶν καλῶς λέγων, “οὐδὲν ἄλλο ἐστὶν ἢ τὸ τὰ δέοντα πράττειν, a feast…is nothing other than doing what is necessary, turning it into a statement about feasts rather than about how the Athenians regard feasts, and a statement with which his readers are expected to agree rather than take as a criticism. (Sorry about the variable fonts, but the WordPress app hates my old iPad at the moment).

As with the Plut passage discussed earlier, putting this English version back into T’s text wouldn’t make much sense – but here that’s because of Origen’s rewriting, which the translator simply follows. How familiar was O with Thucydides? He certainly cites a range of classical Greek authors – earlier in the same book he referred to the story in Herodotus about the Lacedaemonians refusing to prostrate themselves before the king of Persia because they owed allegiance to the law of Lycurgus instead – but not clear whether he’s read the whole text, which in this case he’s misremembering or paraphrasing/rewriting to suit his purpose, or has simply heard the line somewhere. Were lines from T about different topics already circulating as isolated snippets of wisdom, totally removed from their original context or meaning?

Don’t expect to encounter these quotes very often, not least because they’re a lot more specialised and therefore less generally useful. But striking that phenomenon of treating T as an authority, even on things he didn’t write about, was an ancient thing not just a modern one. With O in particular, a line gets decontextualised and reworked in order to put the weight of classical Greek wisdom behind an idea, regardless of anachronism; loses the political dimension, extracted from specific Athenian context or references, taken into sphere of religion or personal relations.

The modern habit of using lines from the funeral oration line – ‘the secret of happiness is freedom and the secret of freedom is courage’ – to advertise meditation classes, wellness courses etc suddenly seems much less jarring and new…

Neville Morley's Blog

- Neville Morley's profile

- 9 followers