Amy Licence's Blog, page 4

August 31, 2013

Was the downfall of Richard III caused by a Strawberry?

Richard III's actions in the summer of 1483, when he unexpectedly put aside his twelve-year-old nephew and became King of England, are considered to be out of character. Could a food allergy have triggered the series of events that lead to the fall of the House of York?

Here's my piece in the New Statesman:

http://www.newstatesman.com/ideas/2013/08/was-downfall-richard-iii-caused-strawberry

Published on August 31, 2013 03:31

August 10, 2013

Royal Babies; those we've forgotten and how times change.

Here are the links to two new pieces I've written recently:

How do the White Queen and the Duchess of Cambridge's baby experiences compare?

http://www.royalcentral.co.uk/blogs/how-times-change-two-royal-births-edward-v-1470-and-george-prince-of-cambridge-14075

Some of those who were born to be great but never made it- forgotten royal babies:

http://www.newstatesman.com/ideas/2013/07/forgotten-history-royal-babies-youve-never-heard

How do the White Queen and the Duchess of Cambridge's baby experiences compare?

http://www.royalcentral.co.uk/blogs/how-times-change-two-royal-births-edward-v-1470-and-george-prince-of-cambridge-14075

Some of those who were born to be great but never made it- forgotten royal babies:

http://www.newstatesman.com/ideas/2013/07/forgotten-history-royal-babies-youve-never-heard

Published on August 10, 2013 08:26

June 25, 2013

“It is the spectator, not life, that art really mirrors:” Does The White Queen have any responsibility towards its viewers?

With over 5 million viewers in the UK tuning in for the first episode of The White Queen last Sunday, fresh debates have been sparked over the nature of historical fiction. While some viewers have been happy to accept the medieval simulacra that the Sunday night Downton slot represents, others have been gleefully vocal in dismembering the series for its anachronistic armour or the wrong shaped pennants. Now there’s nothing wrong with that. The novels and the BBC adaptation can be enjoyed on a number of levels; there’s room for the swooning romantics and the penant pedants but more worrying, is the suggestion I have seen voiced this week, that novelists have some sort of moral responsibility.

Here's my review of the first episode: http://www.newstatesman.com/culture/2013/06/white-queen-romance-sex-magic-scowling-social-snobbery-and-battles

Historical fiction is a hybrid genre, almost oxymoronic in combining the roles of the accuracy-driven historian with the artistic freedom of a novelist. Often, these come into conflict and sometimes lead a work to be misunderstood. Such greats as Jean Plaidy, Anya Seton, Sharon Penman and Josephine Tey have long been enthusing readers with their depictions of real people from the past, which often spark a lifelong interest that quickly translates to the non-fiction shelves. But the most significant thing to remember is that a novel, set in any time period, remains a novel. As such, it is subject to different rules and necessities in order to satisfy its own definition. Novelists are a little bit magic; they can bend rules, adapt events, distort real people and even change the course of history, all in the name of art. The only responsibility a novelist has is to their creation.

Herein lies the problem with The White Queen adaptation.Those claiming that the series, and by association, the screenwriter, Emma Frost, novelist Philippa Gregory and all other historical novelists, have some sort of responsibility to tell history accurately, are operating with a different definition of what novelists do. This week, it seems clear that there are many definitions, depending on whether one is coming from the standpoint of a student of literature or history or both. Many critiques are offered of novels that fall short on the historical facts; if you know your stuff it is easy to pick out an incorrect date or the wrong family relationship, or that so-and-so was not actually at such-and-such a place because he was, in fact, elsewhere. Far less attention is paid to the literary skills displayed in such works. Ultimately, an historical novelist's first responsibility is to literature, then to history. Otherwise they should be writing non-fiction.

So what does the "novelist" part of the historical novelist do? Well, they do not simply tell stories. Nor do they narrate historical events with a few descriptive bits or imagined dialogue. They are jugglers of pitch and tone, balancers of opposing moods and sculptors of satisfying, complimentary narrative threads. They match protagonist against antagonist, lull us into a false sense of security before a sudden moment of fortune reversal (peripeteia in literary parlance) plunges us into pathos or catharsis. They exploit a character’s hubris, or hamartia (error of judgement), for dramatic effect. Factual concessions do sometimes need to be made in order to satisfy dramatic outcomes, so they cut and paste what is included and what left out. Novelists are subject to the same freedoms as artists rather than being bound to the accuracy of historical study. They use mimesis to imitate and perfect life, rather than depict it in a state of realism.

Real people from the past are not “real” to many novelists. (I do not claim to speak for all novelists and I am sure some will disagree.) Put in the simplest of terms, historical figures are the novelist's raw material, to be shaped at will into something beautiful, accurate and true to life. This does not imply a lack of respect nor an intense passion for historical accuracy. Many writers of historical fiction do meticulous research and combine excellent story-telling with spot-on facts. Yet they would be the first to concede that where the history leaves gaps for interpretation, the trade-off with fiction begins. History rarely records the conversations, private emotions and sometimes even the key events of our most beloved heroes and heroines, so the novelist steps in to supply them, in sympathy with their aims. Some may go further and write imagined scenes, or create new offspring, friends or servants alongside real people. Others might even use them as mouthpieces for scenes of witchcraft, as in The White Queen or attribute to them unproven crimes or adventures, in such potentially fertile dearths as Shakespeare’s missing years. The 2011 film Anonymousused the authorship question to explore similar unproven theories about the life of the Earl of Oxford, which was art doing what it does best. It has a licence that history does not. Whilst it might be in danger of irritating those who are wedded to their facts, it certainly does not betray any sort of moral responsibility, simply because it has none.

No one has expressed this more clearly that Oscar Wilde, whose prologue to The Picture of Dorian Gray offers such illuminations as “there is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written or badly written. That is all” and “the morality of art consists in the perfect use of an imperfect medium.” Wilde proceeds to exonerate writers; “an ethical sympathy in an artist is an unpardonable mannerism of style” which anticipates today’s debates about their role. For what novelists and adaptations like The White Queen ultimately sell is a dream. Their readers/viewers, predominantly women, want to enter into an escapist realm of romantic dreams, similar to those fairy tales of chivalry they read as children; princesses, knights on horseback, castles and battles against seemingly insurmountable odds. They want the chocolate box simulacra of the fifteenth century, not the reality of animals being slaughtered in the back yard and piles of dung in the corners, or dirty faces and clothing. They want clothes to be easily ripped off by lovers, even if that does require a zip being used on set. As Wilde wrote, “It is the spectator, not life, that art really mirrors.”

Historical novelists come in all shapes and forms, from those who loosely weave in and out of the facts to those who animate the past with every period detail correct. The opposing ends of this spectrum cater for very a different readership and are usually marketed as such. The responsibility also lies with the reader to be aware of their own reading requirements as well as remembering the nature and variation of the genre. The only sticking point arises when marketing can mislead and present some novels as vehicles of historical truth. What appears to have annoyed historians most this week is the rash of media headlines along the lines of “Philippa Gregory tells the truth behind The White Queen.” Gregory herself has acknowledged the nature of her work: “to combine the truth of an historical record with the truth that can be told in a novel is, I think, a great challenge and a pleasure.” She has been criticised by fellow novelist Robin Maxwell for rejecting what she knows to have been the “truth” in favour of what is “most dramatic” for her readers. This criticism would have some validity if she were writing non-fiction; it has none if she is writing a novel. From this, two types of conflicting authors emerge: those who are historians first and novelists second, against those who are novelists first and historians second. Maxwell is the former, Gregory is the latter.Here's my piece from the BBC History website: The White Queen, who was she really? http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/0/22840690

Of course there are truths and “truths”. There can be little argument in the case of unshakeable facts, such as the battle of Bosworth Field being fought in August 1485 or Anne Boleyn’s delivery of a daughter in 1533. The novelist can exploit the grey areas of emotion around these events, picture Richard charging headlong into Henry VII’s forces or imagine Anne’s feelings during pregnancy and birth. But novelists are also uniquely exploited to deal in emotional “truths”, to present what feels to them to be the most likely explanation of events or to be “true” to character. To facilitate this, they might need to tweak the facts to prioritise one version over another, creating a collision of “truth” and subjectivity which gives rise to criticism. Yet most historical events are open to debate and this variety of approaches makes for a rich and fascinating dialogue that can move all sides closer to an understanding of what actually happened, if indeed one single “reality” can be extrapolated from the experiences of all involved. Fiction has a part to play in this too, so long as its facility with artistic interpretation is recognised.

The only responsibility The White Queen BBC series has is to entertain. Its bed linen might be whiter than white but that is a necessary element in the set-design of a dream. The vast majority of Gregory’s fans want to be swept along with the romance, not put off by Edward and Elizabeth romping in grey, torn sheets. There’s nothing wrong with that, as we recognise what we’re looking at. So, criticise The White Queen and Gregory’s novels for being badly written or for falsely claiming historical accuracy, if you will, but do recognise them for what they are, which is “art.” Where we place them on the artistic spectrum is another matter entirely.

Published on June 25, 2013 09:02

June 21, 2013

Royal Babies

My forthcoming book ‘Royal Babies, a History 1066-2013,’ will be published to tie-in with the impending birth of the new royal baby in July 2013.

The expectant royal parents

The expectant royal parents

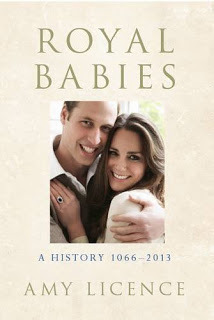

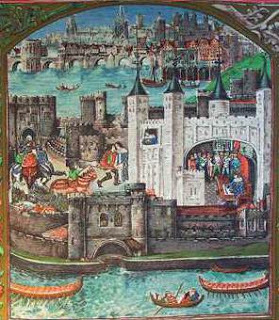

Babies are born every day, but only once or twice in a lifetime, a child arrives who will inherit the throne. This summer, the Duchess of Cambridge will deliver our future monarch. There will be predictions, expectations and a flurry of media attention around the new parents but apart from the flashing cameras and internet headlines, this is nothing new. Royal babies have excited interest since before their births, for more than a millennium. Edward V born in 1470 in sanctuary

Edward V born in 1470 in sanctuary

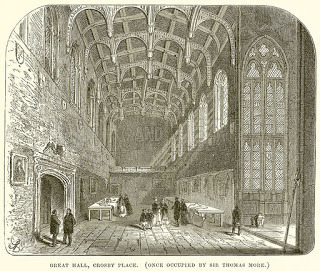

When a queen or princess conceived, the direction of a dynasty was being defined and the health and survival of the child would shape British history. Amy Licence explores the stories of some of these royal babies and the unusual circumstances of their arrivals from the Normans to the twenty-first century. 1470 saw the arrival of Edward, a longed-for son after three daughters, born in sanctuary to Edward IV and his beautiful but unpopular wife, Elizabeth Wydeville (The White Queen); he was briefly King Edward V at the age of twelve, but would disappear from history as the elder of the two Princes in the Tower. In 1511, amid lavish celebrations, Catherine of Aragon gave birth to the future Henry IX, whose survival would perhaps have kept Henry from having five more wives; alas, he was to die after just seven weeks. In 1817 came George, the stillborn son of Charlotte, Princess of Wales; had she not died as a result of the birth, she would have become queen instead of Victoria. James VI and 1 born to Mary Queen of Scots in 1566

James VI and 1 born to Mary Queen of Scots in 1566

This new book explores the importance and the circumstances of these and many other arrivals, returning many long-forgotten royal babies to the history books.

Available to pre-order on Amazon here: http://goo.gl/9aiSO [image error] or for free worldwide postage and packing, pre-order at the Book Depository here: http://goo.gl/sW6Xk [image error] Plus a link to Dhruti Shah's Royal Babies piece, which quotes me:http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/0/22623324

The Black Prince, born in 1330 but fated never to rule

The Black Prince, born in 1330 but fated never to rule

The expectant royal parents

The expectant royal parentsBabies are born every day, but only once or twice in a lifetime, a child arrives who will inherit the throne. This summer, the Duchess of Cambridge will deliver our future monarch. There will be predictions, expectations and a flurry of media attention around the new parents but apart from the flashing cameras and internet headlines, this is nothing new. Royal babies have excited interest since before their births, for more than a millennium.

Edward V born in 1470 in sanctuary

Edward V born in 1470 in sanctuaryWhen a queen or princess conceived, the direction of a dynasty was being defined and the health and survival of the child would shape British history. Amy Licence explores the stories of some of these royal babies and the unusual circumstances of their arrivals from the Normans to the twenty-first century. 1470 saw the arrival of Edward, a longed-for son after three daughters, born in sanctuary to Edward IV and his beautiful but unpopular wife, Elizabeth Wydeville (The White Queen); he was briefly King Edward V at the age of twelve, but would disappear from history as the elder of the two Princes in the Tower. In 1511, amid lavish celebrations, Catherine of Aragon gave birth to the future Henry IX, whose survival would perhaps have kept Henry from having five more wives; alas, he was to die after just seven weeks. In 1817 came George, the stillborn son of Charlotte, Princess of Wales; had she not died as a result of the birth, she would have become queen instead of Victoria.

James VI and 1 born to Mary Queen of Scots in 1566

James VI and 1 born to Mary Queen of Scots in 1566This new book explores the importance and the circumstances of these and many other arrivals, returning many long-forgotten royal babies to the history books.

Available to pre-order on Amazon here: http://goo.gl/9aiSO [image error] or for free worldwide postage and packing, pre-order at the Book Depository here: http://goo.gl/sW6Xk [image error] Plus a link to Dhruti Shah's Royal Babies piece, which quotes me:http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/0/22623324

The Black Prince, born in 1330 but fated never to rule

The Black Prince, born in 1330 but fated never to rule

Published on June 21, 2013 09:42

June 9, 2013

Christopher Marlowe's family and the birth of Modern English midwifery in Elizabethan Canterbury.

This is a speech that I delivered to the Marlowe Society in Canterbury on 8 June 2013:

An early Jacobean swaddled baby A very important birth took place in Canterbury in the 1560s. It was that of modern English midwifery. Three years after the first son of John and Katherine Marlowe arrived in the parish of St. George the Martyr, the ancient profession finally received recognition and regulation. In the chapter house of Canterbury Cathedral, Archbishop Matthew Parker administered the first English oath of its kind to a woman named Eleanor Pead. The content of this oath, recorded in Strype’s Annals of the Reformation, illuminates the nature of childbirth in the period that Katherine bore her family, particularly post-Reformation concerns regarding the customs and superstitions of the lying-in room. It raises questions of baptism, witchcraft, violence, deception, illegitimacy and poverty in Christopher Marlowe’s city, which will form the basis of this talk. By 1567, Eleanor was an established practitioner: she may have been the midwife recorded as living near the Marlowes in their house on the corner of St George’s Street and St George’s Lane, or an associate of hers. There is even a chance that her experienced hands helped bring Christopher and his siblings into the world.

An early Jacobean swaddled baby A very important birth took place in Canterbury in the 1560s. It was that of modern English midwifery. Three years after the first son of John and Katherine Marlowe arrived in the parish of St. George the Martyr, the ancient profession finally received recognition and regulation. In the chapter house of Canterbury Cathedral, Archbishop Matthew Parker administered the first English oath of its kind to a woman named Eleanor Pead. The content of this oath, recorded in Strype’s Annals of the Reformation, illuminates the nature of childbirth in the period that Katherine bore her family, particularly post-Reformation concerns regarding the customs and superstitions of the lying-in room. It raises questions of baptism, witchcraft, violence, deception, illegitimacy and poverty in Christopher Marlowe’s city, which will form the basis of this talk. By 1567, Eleanor was an established practitioner: she may have been the midwife recorded as living near the Marlowes in their house on the corner of St George’s Street and St George’s Lane, or an associate of hers. There is even a chance that her experienced hands helped bring Christopher and his siblings into the world.

This portrait is reputed to be of Christopher Marlowe

This portrait is reputed to be of Christopher MarloweKatherine’s childbearing record is typical of its times. Over a period of fourteen years, she bore nine children. Five of them reached adulthood. The average interval between the birth of one and conception of another was thirteen months, suggesting that she was breastfeeding for the recommended period of a year, although these intervals did vary. For example, after Christopher’s birth, her next recorded conception, with her daughter Margaret, did not occur for over two years, whereas, after the deliveries of both Jane and the first boy called Thomas, she fell pregnant again in only three months. This was a fairly punishing physical regime, with each additional child increasing her risk of mortality, taking a further toll on her body and adding to her domestic workload. In enduring this, as well as the general contemporary perils to health and the virulent outbreaks of bubonic plague that decimated the Marlowe’s parish by a third in 1564 and again, by a half in 1575, Katherine proved herself to be a survivor. Others in her immediate circle of family and friends were not so fortunate.

The twenty year old John Marlowe arrived in Canterbury in 1556, having grown up in nearby Ospringe. Three years later he was apprenticed to shoemaker Gerard Richardson and two years after that, on May 22 1561, he was married to Katherine Arthur of Dover. Their first child was conceived three months later. This again, was typical. My analysis of the parish records of a number of Essex towns and villages indicates that around one in five brides were already in their first trimester at the time of marriage, a further one in eight conceived around the time of the ceremony, giving birth almost exactly nine months later, whilst a quarter, like Katherine, fell pregnant in the first three months. Medical texts of the era did describe the act of love, giving clues about the way performance and ritual could influence conception but I prefer to let John and Katherine’s son draw a more poetic veil over the occasion. So, taken from his translation of Ovid’s fifth elegy:

“Stark naked as she stood before myne eye

Not one wen in her body could I spy.

What arms and shoulders did I touch and see

How apt her breasts were to be pressed by me!

How smooth a belly under her waist saw I

How large a leg and what a lusty thigh.

To leave the rest, all liked me passing well,

I clinged her naked body, down she fell.”

The Marlowe's house, destroyed by bombing in 1942.

The Marlowe's house, destroyed by bombing in 1942.There were no over-the-counter pregnancy tests in Katherine’s day. Doctors may have diagnosed her condition by examining her urine, with one text of 1552 describing that of a pregnant woman as a “clear pale lemon colour leaning towards off-white, having a cloud on its surface.” The practise of mixing wine with urine may actually have produced reliable results, as alcohol does actually react with some elements of urine. Other sources recommended observing a needle left to rust or a nettle turning black when placed in the liquid. Without reliable diagnostic tools, Katherine would have begun to wonder if she was expecting in the summer of 1561 yet she could not be absolutely certain until her quickening, at around five months, that October. Some women mistook the signs altogether. As recently as 1555 and 1557, Queen Mary had undergone two phantom pregnancies, sadly, producing no child from her swollen belly even though the first reputed birth was reported and celebrated in London. The Marlowe’s daughter, Mary, arrived a year after their wedding and was christened in the church of St George the Martyr on 21 May 1562, the day before their first anniversary.

All that remains of the church of St George the Martyr, where the Marlowe children were baptised

All that remains of the church of St George the Martyr, where the Marlowe children were baptised Almost exactly a year later, Katherine conceived for a second time. This interval is highly suggestive. Setting aside the more complex questions of fertility, abstinence and rudimentary birth control, it implies that like most women outside the aristocracy, Katherine Marlowe breastfed her baby. Royalty and noblewomen usually hired wet nurses to allow them to resume their duties earlier and for their fertility to more quickly return. Breastfeeding was convenient, safe and reliable for infants of the Marlowe’s class and, in theory, its contraceptive benefits could protect the recovering mother from conceiving again too quickly. In Christopher Marlowe’s plays, the breast is often synonymous with life. In Tamburlaine, “life and soul hover” in the breast, and it is frequently offered as a place which will accommodate a weapon or death-wound, resulting in the loss of life. Dido claims that Aeneas was suckled by “tigers of Hercynia,” echoing the belief that babies could imbibe the characteristics of the creature that suckled them, in this case, a fierce cruelty. More mundanely, Elizabethan advice warned the suckling mother to avoid harsh flavours such as garlic and spices and not to drink strong alcohol.

Katherine may also have used some of the folklore remedies from this time to assist her milk flow, such as wearing a gold or steel chain between her breasts or following the strange ritual of sipping milk taken from a cow of a single colour and spitting it out into a stream. Equally she may have used common herbs such as mallow, mint and even bitter wormwood to soothe sore breasts or lain cabbage leaves on them. Baby girls were traditionally suckled for less time than boys, as they were considered to be more independent. Their brothers often continued at the breast for up to two years, so it is interesting to note that after Christopher’s birth in February 1564, Katherine is not recorded as having conceived again for twenty-five months. She fell pregnant with their third child, Margaret, in March 1566.

For Katherine, six more children would follow. Of them, the next three would be lost before reaching adulthood; two sons born in October 1568 and the summer of 1570 would die soon after birth. Within weeks of the first loss, Katherine had conceived her daughter Jane, who arrived between these two, on August 20, 1569. This new baby survived the process of delivery, and the dangerous years of childhood, only to die at the age of thirteen: I will be returning to her fate later. Other mothers in Canterbury and the surrounding areas experienced similar patterns of conception to Katherine. The wife of Harry Finch, also resident in the parish of St George the Martyr, delivered six surviving children in nine years, with an average interval of a year between each one. Anne Finch of nearby Faversham conceived more quickly after delivery, at around ten months on average, whilst Dorothee Finch, also of Faversham, had a longer average conception interval of fourteen months. These records though, do not include the losses that women sustained when pregnancies did not reach full term or resulted in stillbirth.

Infant mortality rates during the Elizabethan period were shockingly high. A regular feature of parish registers is the record of an infant’s birth and death taking place on the same day, when circumstances necessitated christening by the midwife at home. Part of Canterbury midwife Eleanor Pead’s oath required her to swear to use the phrase, “I christen thee in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost,” rather than using “profane words” and to perform the baptism with plain water, instead of than the more fashionable rose or damask perfumed water. Otherwise, like Christopher, the Marlowe’s later children were baptised in the thirteenth century octagonal font in the nearby church of St George the Martyr.

An early Jacobean baby, William Larkin, dressed in his finery

An early Jacobean baby, William Larkin, dressed in his finery The Marlowes were more lucky with their final children, Anne, Dorothy and Thomas number two, who were born in 1571, 1573 and 1576 and all lived to adulthood. In fact, the family’s rate of infant mortality, losing one in three as children and a further daughter in her teens, was better than many. The gap of three years between the final two children could perhaps indicate the dwindling of Katherine’s fertility, as a similar pattern can be seen in other women’s childbearing records, such as Anne Finch of Faversham, whose final baby came almost four years after her penultimate one. Perhaps the Marlowes assumed there would be no more children and were caught out. There is also the possibility that other pregnancies occurred during this time but were not carried to term and would not therefore, be recorded, or that the pair deliberately practised some form of birth control or abstinence. This period did coincide with a virulent outbreak of the plague in the city, so survival rather than reproduction may have been the priority. In the previous outbreak, John Marlowe had seen his friend Harman Verson’s entire family wiped out.

*

What was the process of delivery like for an Elizabethan mother like Katherine ? She would have borne her children at home, which was not as routine as it sounds. Some young wives chose to labour in the homes of their parents but Katherine’s Dover roots, although not prohibitive, made a Canterbury birth easier. She probably lay in a four poster bed, with its flock mattress and curtains hanging from rods, an example of which is listed in a 1605 inventory of her goods. In the days leading up to her confinement, she would have waddled across to St George’s church to take communion, the blessing of which would extend to her unborn child during the approaching period of danger. And it was a very real danger, which mother and baby would be lucky to survive.

Even though she knew what to expect by the 1570s, Katherine’s chances of injury, infection and death increased with each child she bore, and mindful of the danger, she may have turned to some of the birthing talismen or charms of the day. Women typically used a variety of items such as gem stones, pieces of tin, cheese or butter engraved with charms, belts hung with cowrie shells, as well as potions including such strange ingredients as powdered ants’ eggs. As there was no pain relief in the modern sense, these may have acted as a panacea by giving a woman some limited degree of control or sense of ownership over a frightening and painful ordeal. Anything that helped the mother to relax, as far as possible, could have contributed to an easier labour.

Also used as birthing aids were girdles, of a real or symbolic nature. Mephistopheles makes Dr Faustus invisible by the use of a magic girdle, which was the traditional item that English queens used to wear to assist labour before the Reformation. Elizabeth of York and Catherine of Aragon wore the Westminster girdle of Our Lady but the destruction of relics and icons in the 1530s and 40s substituted their reputed healing power with something more sinister, which Marlowe exploits in the play.

Dr Faustus and the Devil

Dr Faustus and the DevilAccording to custom, John would have been excluded from the birth room and Katherine would have put herself in the capable hands of a midwife and several attending women, or gossips. So long as the child presented itself head first and everything else was relatively straight-forward, her labour would have progressed well. If the baby was breech, or an arm or leg showed first, then her chances of survival began to decrease. As part of her oath, Eleanor Pead swore that she would “be ready to help poor as well as rich women in labour” and that she would not “dismember, destroy or pull off” the limb of any child during the process. Sometimes, when a son was desired, the baby was stillborn or a live child was born with what was considered some form of defect, it was substituted for another. The bizarre case of Agnes Bowker, in 1569, saw her and her midwife claiming that she had delivered the skinned body of a dead cat, in circumstances and for motives that are still unclear. Two years earlier, Eleanor had sworn not to “suffer any other body’s child to be brought to the place of a natural child.”

Labouring mothers were also thought to be vulnerable to supernatural influences as they hovering on the margin of life and death and in the eyes of the church, midwives were uniquely placed to exploit this. Clergymen worried about the use of charms and old practises associated with witchcraft, magic and Pagan rites, suspecting them of making extra money by supplying witches with items for their cauldrons.

Shakespeare's witches from Macbeth

Shakespeare's witches from MacbethEleanor’s oath forbade her from retaining such items as the caul, placenta and umbilical cord, even body parts, like Shakespeare’s “finger of birth-strangled babe,” delivered in a ditch. There was a particular traffic in cauls, as these were believed to have powers to protect the bearer from drowning, so they were much sought after by sailors. We also have Faustus at one stage proposing to build an altar and a church to Beelzebub and offer him “lukewarm blood of new born babes.” Many of the herbs associated with childbirth, which were used by midwives came with associated rituals, such as being picked in moonlight or at midnight whilst a charm was muttered. Thus, the midwife, who was usually a woman of experienced years, also a repository of women’s secrets and skills, could easily attract an accusation of witchcraft. In 1566, when the future James I was born in Scotland, an attendant to his mother, Mary Queen of Scots, is reputed to have used sorcery to attempt to divert her labour pains to another woman.

In Elegy eight, Marlowe depicts a matchmaker called Dipsas, a medical woman or witch, whom he calls a “trot,” after the twelfth century female doctor Trotula, also Chaucer’s Dame Trot:

“She magic arts and Thessale charms doth know

And makes large streams back to their fountains flow.

She knows with grass, with threads on wrong wheels spun

And what, with mares’ rank humour may be done.

When she will, clouds the darken’d heaven obscure,

When she will, day shines everywhere most pure.”

When Christopher was seven years old, a Mother Hudson, of the parish of St Mary’s, near the Donjeon, not too far removed from the Marlowe’s home, was presented before a Grand Jury under suspicion of witchcraft. No doubt such a case would have been the subject of local gossip. Later, the playwright would depict Faustus being seduced by the concealed arts, which he considers enticing, challenging and superior; “both law and physic are for petty wits, ‘tis magic, magic, that ravished me,” and he feeds or “surfeits upon necromancy.” The elegy’s trot, Dispas, “with long charms the solid earth divides” and can “draw chaste women to incontinence.” Midwife Eleanor swore “I will not use any kind of sorcery or incantations in the time of travail of any woman.”

Returning to births in the Marlowe family, it transpired that Katherine’s daughter Jane, born in 1569 was less fortunate than her mother. She married young, at just twelve and died in childbirth the following year. While such an experience feels horrific to a modern audience, it was not uncommon at the time, being determined by the onset of puberty in the girl concerned, in line with the contemporary age of consent.

Jane Marlowe’s age, or perhaps her correlative size, could well have been factors in her death. Equally though, she could have been the victim of circumstances or the imperfect contemporary understanding of hygiene. Roger Schofield’s essay “Did the Mothers Really Die?” estimates that just under one per cent of Elizabethan mothers died in childbed, although in cities, such as London’s densely packed Aldgate, other studies indicate the figure was more like 2.35 per cent. Ian Mortimer, author of the popular Time Traveller’s Guide to Elizabethan England, places it at two per cent, or one in fifty. Having lost siblings, Christopher was aware of the fragility of life, a common Elizabethan motif that finds its way into the literature of the times; perhaps most apt is Tamburlaine’s comment “our life is frail and we may die today.” When it came to saving the lives of mother and child, a midwife’s interventions in such cases could range from the minimal to the downright harmful. The Elizabethans believed that illness and infection were transmitted through smell, hence the use of elaborate nosegays and pomanders as well as the beaks of later plague doctors, yet there was little understanding of the need to wash hands and prevent cross-contamination. The dirty hands of midwives must have cost many maternal lives.

*

One of the reasons for the introduction of Eleanor Pead’s oath was illegitimacy. Her vows were drafted in tandem with the new phase of Elizabethan Poor Laws and were part of a wider attempt to track down the fathers of such children and make them accept social and financial responsibility. Illegitimate children would have been cared for at the expense of the parish in which they were born, so the church was keen to ensure that parents were held accountable. Eleanor’s oath is placed between the 1563 law to categorised the different types of poor, and the 1574 imposition of compulsory taxes to support those in need. Illegitimacy was a problem in Elizabethan England; not necessarily of epic proportions but it was a culture that was very conscious of an individual’s origins.

Contemporary image of an Elizabethan beggar

Contemporary image of an Elizabethan beggarWhen Christopher Marlowe uses the words “born” and “birth” in his plays, it is primarily to identify a person’s social rank, indicating when upstarts are attempting to overreach their station. The next most common occurrence is when a character is described as base-born, of lowly birth and, as a result, of a crude and vulgar disposition. In some cases in his works, individuals identify the correlation between the positions of the stars in the heavens and the moment of their birth, inferring some greater destiny, beyond their mean origins. In Marlowe’s time, baseness and illegitimacy were considered key indicators of a person’s worth. In the Baines Note, the Harley Manuscript testimony of Richard Baines, which reputedly contained “the opinion of one Christopher Marley concerning his damnable judgement of religion and scorn of the word of God,” perhaps the worst blasphemy of all, is the assertion that, (and I quote) “Christ was a bastard.”

The midwife could be a figure of dread to an unmarried mother, playing an increasingly central role in court paternity examinations and the report of illegitimate births, such as the 1573 labour of spinster Agnes Hollway in Canterbury, which was reported to the ecclesiastical court. One of the key duties of the new profession was the attribution of paternity in cases of babies born to unmarried mothers. The midwife was expected to take advantage of the woman’s debility and fear, in the most extreme moments of labour, to cross-question her and ascertain the father’s identity. For the labouring mother, afraid and often deserted by the father, it meant that the one person on whom she was most hoping to rely, was also the one she could least trust. The court rolls include phrases from examinations such as “when she was in peril of her life and to her thinking more likely to die than to live” and “being in very grievous pain and great peril of death before the midwife until her deliverance.”

Cases in East Kent indicate that illegitimate births were not uncommon. In the parish of Rolvenden, in the Kent countryside but still in the Canterbury diocese, Margery Deedes, a midwife and four other women who had attended the delivery of Anne Jones were summoned to the local court to answer concerning the child’s paternity. Another baptismal record there, of 1570, contains the additional note “the mother has confessed before the midwife and other honest women at the very birth of the child.” One Canterbury man, a baker from the Westgate area, called John Davison, was summoned to appear and answer concerning being the reputed father of a bastard child born to Annis Ferriman, a spinster of Chartham. The punishments could be severe, with fathers being required to make weekly payments until the child reached a certain age, sometimes thirteen, or whenever they could earn their own living. The parents could expect to be stripped to the waist and flogged in the streets, often in front of the church or market place after evening or Sunday prayers. One grisly ruling required that both were whipped “until the blood shall flow”.

In Canterbury, women considered to have been living wanton lives were publicly shamed. In 1537, the wife of John Tyler, was presented before the Grand Jury for “living viciously… for the which her husband hath forsaken her and the Jury desire she may be banished by the feast of St James next, under the pain of open punishment in the ducking stool.” The year after the Marlowes were married, the jury were presented with “the wife of Stephen Colyer, for that she is not of good name, nor fame, but liveth viciously; for the which she hath been divers times banished, out of one ward into another, and in conclusion banished by all the Council of the Shire of Canterbury; and that, notwithstanding, she is abiding in the city, viciously and idly using herself.” It is interesting that neither woman is identified by their given name, instead being called “the wife of,” as their behaviour was reprehensible for the shame it cast upon their husband and the institute of marriage.

Christopher Marlowe’s fourth elegy depicts an adulterous relationship, through the eyes of a male protagonist lusting after a married woman:

“Thy husband to a banquet goes with me

Pray God it may his latest supper be

Shall I sit gazing as a bashful guest

While others touch the damsel I love best?”

“Mingle not thighs nor to his leg join thine

Nor thy soft foot with his hard foot combine.”

Clearly there was a fair bit of thigh mingling going on among the bachelors and spinsters of Canterbury. Whilst mothers who produced illegitimate children could not deny the fact, men who were judged to have fathered illegitimate offspring could be fined and jailed if they refused to comply. Another of the many inequalities in the expectations of male and female behaviour governed the question of rape. Women were thought only to be able to conceive if they had experienced pleasure during intercourse, so if a woman fell pregnant as a result of a forced encounter, her allegation was considered invalid. It is not surprising then, that some resorted to desperate measures, attempting to bring about a self-inflicted abortion by the use of certain herbs, which might have no effect at all or sometimes result in the death of the mother herself. Sadly, there were also cases of abandonment and infanticide in the city, prompted by social pressure or misunderstood post natal depression. If proven by witnesses, these could result in the sentence of death being passed on the perpetrator, who was usually the mother.

To explore the childbearing record of Katherine Marlowe, in the context of the oath sworn by Eleanor Pead, is to open an Elizabethan dialogue of paradoxes. It evokes the nature of pregnancy and birth as characterised by questions of life and death, frailty and survival, suffering and rejoicing. During delivery, women experienced real and inescapable fears about their own survival, which, for unmarried mothers translated as an uneasy relationship with their midwife, of dependency, denial and exploitation, legitimacy and illegitimacy, acceptance and rejection, nurture and abandonment. In attempting to gain some degree of ownership over their labouring bodies, women like Katherine may have employed some of the old superstitious methods, against which the church reacted in a battle of religion against magic. In the shadow of Canterbury Cathedral, with the potential abuses of midwifery considered worthy of legislation, Christopher Marlowe and his siblings arrived in the world at a significant moment.

Published on June 09, 2013 01:59

May 24, 2013

To drown or not to drown: The Sixteenth Century Suicide that Inspired "Hamlet".

Above, Millais' Ophelia 1851-2. Below, the river Stour as it passes through Canterbury

Above, Millais' Ophelia 1851-2. Below, the river Stour as it passes through Canterbury

I live in Canterbury. It’s not the only English city overflowing with history but it is a compact little circle, with plenty of Norman, medieval and Tudor features sitting atop its Roman streets. Until fairly recently, I used to teach English in a grammar school set in fields overlooking the cathedral. I often used my location to inject a bit of colour into my lessons, encouraging small boys to picture Chaucer’s pilgrims walking up the present day high street to the Checker of the Hope Inn, which is now a sweet shop, or Christopher Marlowe being born on the site of the new shopping centre. For a few years, I taught Hamlet for AS-level coursework, spending whole days acting and analysing imagery, context and the conventions of tragedy. Imagine my surprise then, when I was researching the history of my street in the sixteenth century and found that it had a direct influence on Shakespeare’s portrayal of the death of Ophelia.

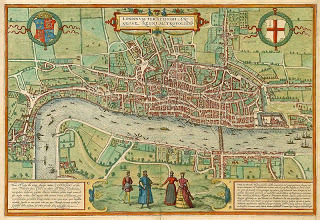

I live off a long, wide road called Wincheap, or Wine chepe, as it was in the medieval period when merchants gathered there to sell their imported wines. It begins opposite the Norman Castle and passes out of the old city walls for about a mile before it reaches the Thanington area. The manor there was owned by the prominent local Hales family, whose patterns of fertility and childbirth I was studying, when I uncovered an interesting anecdote about Sir James Hales.

Born around 1500, the son of John Hales, MP for the city, James had prospered under the regime of Henry VIII and Edward VI, becoming a judge and Baron of the Exchequer. However, as a devout Protestant, he had refused to convert to Catholicism under Mary and fell foul of Bishop Gardiner, who had him imprisoned. James appears to have been a volatile and melancholy character; his misfortune led him to try and commit suicide with a knife whilst in the Tower. By August 1554, he had been released and was staying with his nephew at the Thanington Manor when he succeeded in killed himself by lying face-down in the river. This branch of the Stour now runs alongside a path popular with walkers and cyclists, along which I had walked on the very day that I later discovered James’ fate.

....and more Stour

....and more StourHales’ death prompted a famous court case. His widow, Margaret, attempted to regain some of his property, which according to sixteenth century legal practice, would have been forfeit in the case of James taking his own life. Bizarrely, the argument turned on whether the “felony” had occurred before Hales’ death or afterwards. In 1554, the coroner had ruled that his death was a criminal act but the case dragged on until 1562, when the ruling finally went against Margaret. The lawyer Sir Edmund Plowden published a full report of the case in 1571, so it is likely that Shakespeare saw his version of this infamous struggle. It appears to have crept into the conversation of two incidental characters in one of his best known plays.

At the start of act five, two “clowns” debate the legal question of suicide. This is prompted by the death of Hamlet’s beloved Ophelia, whom, we understand, was “clambering to hang” the “fantastic garlands” she had made on a willow tree growing over a brook. When the branch broke and she fell, her heavy garments weighed her down and, driven to madness by Hamlet’s murder of her father, was “incapable of her own distress.” One clown tells us she is to have a Christian burial but the other argues that this is contrary to the contemporary notion that to take one’s own life was “self-murder,” thus excluding the culprit from burial in consecrated ground or receiving funeral rites. Then follows an odd little speech explaining that it is one thing if a man goes to water to drown himself and quite another if the water comes to him. This is almost word for word what the inquest ruled in the case of Canterbury’s James Hales.

When teaching Hamlet, I always found this scene strange. I can accept the juxtaposition of the jaunty little humour with the morbidity of Ophelia’s funeral; it’s a necessary outlet from all the intense passion. But this little section of dialogue seemed to relate to something so specific and sit oddly with the rest of the scene, that I concluded that there was simply something I was missing. Now I know what it was.

.... and the final piece of Stourage!

.... and the final piece of Stourage!As we walked home from town beside the river Stour this Saturday, the “glassy stream” was peaceful. There were indeed trees, if not willows, growing aslant the brook, reflecting their “hoar leaves” in its clear waters and nettles and daisies growing alongside. There were also teenagers on bikes, high speed trains rattling alongside and toddlers playing pooh sticks. Strange to think that almost five hundred and fifty years before, one man’s act of despair here could have inspired one of the greatest tragic scenes in early modern drama.

This piece originally appeared in the Huffington Post on May 13, 2013

Published on May 24, 2013 07:55

May 21, 2013

Forthcoming Book: "Royal Babies: A History 1066-2013"

In July this year, my book "Royal Babies; A History 1066-2013" will be published.

NB. This will not be the final cover- that will feature an image of the new royal baby.

NB. This will not be the final cover- that will feature an image of the new royal baby.

In it, I've chosen 25 births from the last millennium which are interesting in some way; these babies may have changed the succession, arrived in unusual circumstances, or not been the gender their parents hoped for. Others were eldest sons who did not make it to the throne or some who were not destined to rule but ended up as Kings or Queens. Quite literally, some were born great, some achieved greatness and some had greatness thrust upon them! The book will also include information about the changing practices surrounding pregnancy, childbirth and infant care. One narrative thread deals with the history of midwifes/accouchers, exploring the times when it was more fashionable to have a man or woman assisting at the birth and the effects of this. It's a subject that is already proving of interest to readers, so I thought I'd put up the links to two other pieces I've done on it, to give you a taster.

"More Lion's fat Ma'am?" Bizarre Birth Customs from History. 11/5/13

http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/amy-licence/royal-baby-kate-middleton_b_3243783.html

Royal Babies Trivia. April 2013

http://www.bounty.com/royal-baby/royal-baby-trivia

More to come on this topic....

NB. This will not be the final cover- that will feature an image of the new royal baby.

NB. This will not be the final cover- that will feature an image of the new royal baby.In it, I've chosen 25 births from the last millennium which are interesting in some way; these babies may have changed the succession, arrived in unusual circumstances, or not been the gender their parents hoped for. Others were eldest sons who did not make it to the throne or some who were not destined to rule but ended up as Kings or Queens. Quite literally, some were born great, some achieved greatness and some had greatness thrust upon them! The book will also include information about the changing practices surrounding pregnancy, childbirth and infant care. One narrative thread deals with the history of midwifes/accouchers, exploring the times when it was more fashionable to have a man or woman assisting at the birth and the effects of this. It's a subject that is already proving of interest to readers, so I thought I'd put up the links to two other pieces I've done on it, to give you a taster.

"More Lion's fat Ma'am?" Bizarre Birth Customs from History. 11/5/13

http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/amy-licence/royal-baby-kate-middleton_b_3243783.html

Royal Babies Trivia. April 2013

http://www.bounty.com/royal-baby/royal-baby-trivia

More to come on this topic....

Published on May 21, 2013 10:08

May 10, 2013

Read the introduction to "Anne Neville; Richard III's Tragic Queen."

As this is now available free on Amazon as a Kindle preview, I thought I would share the introduction to my latest book on here too. You are most welcome to have a look, make comments and decide whether it is for you:

Introduction Act One, Scene Two. The air is hazy. The room seems to be part medical, part industrial, yet there is a sense of neglect and disrepair. Tiles line the walls and a man in a long white coat stands with his back to the camera, busy over his work. A couple of brown glass bottles and a wooden crutch are visible in the foreground on the right. Rays of opaque light stream through the windows creating a sort of misty underworld. Discordant jazz plays, low and melancholy.

The double doors in the middle of the scene open and she appears. Only a dark silhouette at first, she steps into the room; a slim young woman dressed in a black coat with a large fur collar, glamorous with her lipstick, pearls, heels and dark glasses. Yet it is clear from her demeanour that she is in mourning. Reaching behind her, she pulls the door firmly shut before the camera draws close, foregrounding her face as she removes her glasses. Her expression is an uneasy mixture of subdued horror and resignation. The scene before her is a mortuary. Three bodies lie on marble plinths in a low-ceilinged room where the windows have been shortened with plaster board, making it feel subterranean. She approaches the dead, with her form bathed in shadow, and stops before the corpse of a young man. He lies white and maimed, visibly wounded on the forehead and chest. She leans on the plinth as if the sight of the corpse weakens her, before taking it in her arms and delivering her speech.

This is Anne Neville. Or at least it is the actress Kristin Scott Thomas, playing the role of Anne, in Ian McKellen’s 1995 film version of Shakespeare’s Richard III. But it is not Shakespeare as the playwright would have recognised it. The settings and costumes date the action to the first half of the twentieth century; it is martial, modernist, Art Deco. This Anne is more stilettoes and sunglasses than kirtle and chemise. The mortuary scene was shot in a lower storage room of the empty Pearl Assurance Building, a vast greying edifice constructed between 1912 and 1919 in Holborn, London. It was not a ploy to keep down production costs: the grimy, dimly-lit basement was perfect for the film’s new setting. Written by McKellen and Richard Loncraine, the screenplay updated the story to a fictionalised England of the 1930s, “a decade of tyranny throughout Europe…when a dictatorship like Richard III’s might have overtaken the UK.”[1] It was a fantasy, a parallel world exploring one of history’s “what-if” scenarios; a vision of the Home Counties being administered by the Nazis or Mosely’s Union of Fascists. Thus, a late medieval King was juxtaposed with the rise of the Third Reich in London, echoed in the uniforms, music and set design. Richard III’s story was co-opted as part of a wider history, beyond anything the King himself could have imagined. Recalling the process of writing, McKellen explained “we talked about it in the near-present tense and imagined it taking place yesterday rather than yesteryear. This, I suppose, was what Shakespeare intended.”[2] McKellen was right. As the Bard was writing, in 1591, the events he described were part of recent history, but as an entertainment, legend and a degree of dramatic licence were central to his work’s success. In 1955, Laurence Olivier’s and Claire Bloom’s memorable version of the scene followed more traditional lines and forty years later, McKellen reinvented its setting to draw modern parallels. In this way, Shakespeare’s play is subject to constant revision; each generation adds a new chapter to the afterlife of the text, for better or worse. Similarly, these changes continue the on-going narrative of Anne Neville, daughter of the Earl of Warwick, the legendary Kingmaker. Her life has undergone several phases of reinvention by later generations for the purposes of entertainment and propaganda, which is the very reason her brief existence is remembered. For the historian, Anne herself is not too dissimilar from a “text,” a set of clues to be decoded according to the standards of her day, which may have been mishandled and misrepresented through time. The process began early. Just as Olivier and McKellen adapted Shakespeare, so the Bard distorted actual events of the fifteenth century to better serve his dramatic intentions. The real Anne was not the sophisticated beauty Kristin Scott Thomas suggests; by modern standards she was a child when the key events outlined in this scene actually took place. In the year that she was widowed, 1471, Anne was only fourteen years old. That year she also lost her father and father-in-law, in violent circumstances, whilst she was alone among her former enemies. She would have had reason enough to grieve. McKellen altered Shakespeare again to portray her cradling the dead body of her husband, rather than that of the murdered Henry VI, and Scott Thomas leaves the audience in no doubt about the extent of her emotions. Yet the grief that the role demands is misleading: Anne had been married for about five months, but the union had been arranged for political reasons and was possibly consummated only briefly. After a long association with the Yorkists, Warwick had performed a dramatic u-turn and allied his younger child with their Lancastrian foes. Anne barely knew her boy-husband and no evidence survives to suggest she held him in any affection. The loss of her father was far more significant. It meant that Anne was left alone in the paradoxical position of the teenaged widow, midway through the civil wars that were commensurate with her life span. Clearly Shakespeare’s “history” was a fiction, re-animating well-known figures from the past and putting words into their mouths, within an abridged timescale. Previous chroniclers, story-tellers and historians like Rous, More, Holinshed, Hall and Vergil had done no less. However, Shakespeare’s dramatization of the incident has become so famous that it has almost entirely eclipsed historical fact in the popular imagination: the powerful scene develops along familiar lines as Anne’s grief is interrupted by Richard, Duke of Gloucester, the alleged killer of her relatives. According to the play of 1591, Anne recoils in horror from the blood-stained apparition, which displays the often-repeated physical deformities that were correlative in the Tudor mind with immorality and evil intentions. McKellen follows this interpretation. Playing the part of the King himself, his hunch-backed figure, dressed in military uniform, appears from behind the widow as Anne bends over her husband’s corpse. Sensing his approach, she turns in revulsion to see the “fiend” and curses him, yet Richard is able to manipulate her emotions to the extent that she agrees to become his wife before the exchange ends. Even as the villain, the character’s Machiavellian powers of persuasion cannot fail to impress.

In reality though, Richard was an old friend, perhaps more. His father, the Duke of York, had married Anne’s great-aunt and the young Gloucester had spent several years living as Warwick’s protégée at the family home of Middleham Castle. The Earl may even have been the boy’s godfather. The children would have been brought together regularly, in ceremonial and informal situations, so it not impossible that an early friendship had blossomed between them, surviving Anne’s arranged marriage with the enemy. After all, her family’s sympathies lay first with the Yorkists, then with her Lancastrian husband: next she would marry the boy she had known, whose family had made her a widow. Shakespeare truncates this: Richard forces Anne to accept his ring alongside her husband’s corpse, despite her curses. The actual ceremony took place over a year later in July 1472 and the pair lived together, apparently in harmony for over a decade. It may even have been a love match. The eighteenth century Ricardian Horace Walpole mentioned that Catherine, Countess of Desmond described him as “the handsomest man in the room.” There is no denying though, that the alliance was financially expedient to both, so much so, that they were prepared to enter a marriage that was possibly invalid in the eyes of the medieval church. Together, they were crowned in 1483: Anne was Richard’s companion, his wife, the mother of his child and his queen. Did he then go on to murder her, as Shakespeare suggests ? McKellen shows a rapidly deteriorating Anne. The haggard appearance of the wife contrasts sharply with the earlier elegance of the widow. In the back of a limousine she hitches up her skirt and, according to McKellen’s screenplay, “finds the appropriate spot in her much-punctured thigh.” Her unnamed drug of choice is described in the screen play as “calming” and she closes her eyes and “waits for it to work,” while the orchestra plays triumphantly. Later she appears “doleful” and sad, later still, in a drugged stupor, in a world of her own and finally, catatonic. [3] The last the audience see of her is a motionless form, lying in bed with wide, staring eyes. A spider descends and lands on her face, scurrying away as she remains unblinking. McKellen’s Anne Neville is dead. Obviously, the fifteenth century Queen’s death was not attributable to recreational drugs but the rumours of her demise were just as sinister. Popular culture has upheld Anne as another of Richard’s victims, with Shakespeare placing her among the accusatory ghosts that disturb his sleep before battle. This is unsurprising as the circumstances of her death are shrouded in mystery and, for once, the corrective facts are harder to establish. In early 1485, the corridors of Westminster Palace whispered of jealousy, flirtations, affairs and illness, as some contemporaries suggested Richard might have been planning his second marriage while Anne was still alive, perhaps to a foreign princess, perhaps to his own niece.

Aged only twenty-eight, the Queen passed away amid an eclipse of the sun and the chroniclers were swift to draw their conclusions. Did Richard really play a part in her death; did he “eschew her bed” as she was fatally ill, possibly contagious? Was she poisoned to make way for a younger, more fecund model? Perhaps she was lovingly tended, yet unwittingly administered with medicines that could themselves prove fatal. The truth of Anne’s demise remained unresolved at the time and the dramatic regime change that followed compromised the objectivity of many witnesses and chroniclers. It is time to tease out the facts from the fiction.

Here's the scene from McKellen's film:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3wxGfjcfZkA&list=PLN1dkbJ9dexduepI1w7wK5FfQjdCPgPqu

Introduction Act One, Scene Two. The air is hazy. The room seems to be part medical, part industrial, yet there is a sense of neglect and disrepair. Tiles line the walls and a man in a long white coat stands with his back to the camera, busy over his work. A couple of brown glass bottles and a wooden crutch are visible in the foreground on the right. Rays of opaque light stream through the windows creating a sort of misty underworld. Discordant jazz plays, low and melancholy.

The double doors in the middle of the scene open and she appears. Only a dark silhouette at first, she steps into the room; a slim young woman dressed in a black coat with a large fur collar, glamorous with her lipstick, pearls, heels and dark glasses. Yet it is clear from her demeanour that she is in mourning. Reaching behind her, she pulls the door firmly shut before the camera draws close, foregrounding her face as she removes her glasses. Her expression is an uneasy mixture of subdued horror and resignation. The scene before her is a mortuary. Three bodies lie on marble plinths in a low-ceilinged room where the windows have been shortened with plaster board, making it feel subterranean. She approaches the dead, with her form bathed in shadow, and stops before the corpse of a young man. He lies white and maimed, visibly wounded on the forehead and chest. She leans on the plinth as if the sight of the corpse weakens her, before taking it in her arms and delivering her speech.

This is Anne Neville. Or at least it is the actress Kristin Scott Thomas, playing the role of Anne, in Ian McKellen’s 1995 film version of Shakespeare’s Richard III. But it is not Shakespeare as the playwright would have recognised it. The settings and costumes date the action to the first half of the twentieth century; it is martial, modernist, Art Deco. This Anne is more stilettoes and sunglasses than kirtle and chemise. The mortuary scene was shot in a lower storage room of the empty Pearl Assurance Building, a vast greying edifice constructed between 1912 and 1919 in Holborn, London. It was not a ploy to keep down production costs: the grimy, dimly-lit basement was perfect for the film’s new setting. Written by McKellen and Richard Loncraine, the screenplay updated the story to a fictionalised England of the 1930s, “a decade of tyranny throughout Europe…when a dictatorship like Richard III’s might have overtaken the UK.”[1] It was a fantasy, a parallel world exploring one of history’s “what-if” scenarios; a vision of the Home Counties being administered by the Nazis or Mosely’s Union of Fascists. Thus, a late medieval King was juxtaposed with the rise of the Third Reich in London, echoed in the uniforms, music and set design. Richard III’s story was co-opted as part of a wider history, beyond anything the King himself could have imagined. Recalling the process of writing, McKellen explained “we talked about it in the near-present tense and imagined it taking place yesterday rather than yesteryear. This, I suppose, was what Shakespeare intended.”[2] McKellen was right. As the Bard was writing, in 1591, the events he described were part of recent history, but as an entertainment, legend and a degree of dramatic licence were central to his work’s success. In 1955, Laurence Olivier’s and Claire Bloom’s memorable version of the scene followed more traditional lines and forty years later, McKellen reinvented its setting to draw modern parallels. In this way, Shakespeare’s play is subject to constant revision; each generation adds a new chapter to the afterlife of the text, for better or worse. Similarly, these changes continue the on-going narrative of Anne Neville, daughter of the Earl of Warwick, the legendary Kingmaker. Her life has undergone several phases of reinvention by later generations for the purposes of entertainment and propaganda, which is the very reason her brief existence is remembered. For the historian, Anne herself is not too dissimilar from a “text,” a set of clues to be decoded according to the standards of her day, which may have been mishandled and misrepresented through time. The process began early. Just as Olivier and McKellen adapted Shakespeare, so the Bard distorted actual events of the fifteenth century to better serve his dramatic intentions. The real Anne was not the sophisticated beauty Kristin Scott Thomas suggests; by modern standards she was a child when the key events outlined in this scene actually took place. In the year that she was widowed, 1471, Anne was only fourteen years old. That year she also lost her father and father-in-law, in violent circumstances, whilst she was alone among her former enemies. She would have had reason enough to grieve. McKellen altered Shakespeare again to portray her cradling the dead body of her husband, rather than that of the murdered Henry VI, and Scott Thomas leaves the audience in no doubt about the extent of her emotions. Yet the grief that the role demands is misleading: Anne had been married for about five months, but the union had been arranged for political reasons and was possibly consummated only briefly. After a long association with the Yorkists, Warwick had performed a dramatic u-turn and allied his younger child with their Lancastrian foes. Anne barely knew her boy-husband and no evidence survives to suggest she held him in any affection. The loss of her father was far more significant. It meant that Anne was left alone in the paradoxical position of the teenaged widow, midway through the civil wars that were commensurate with her life span. Clearly Shakespeare’s “history” was a fiction, re-animating well-known figures from the past and putting words into their mouths, within an abridged timescale. Previous chroniclers, story-tellers and historians like Rous, More, Holinshed, Hall and Vergil had done no less. However, Shakespeare’s dramatization of the incident has become so famous that it has almost entirely eclipsed historical fact in the popular imagination: the powerful scene develops along familiar lines as Anne’s grief is interrupted by Richard, Duke of Gloucester, the alleged killer of her relatives. According to the play of 1591, Anne recoils in horror from the blood-stained apparition, which displays the often-repeated physical deformities that were correlative in the Tudor mind with immorality and evil intentions. McKellen follows this interpretation. Playing the part of the King himself, his hunch-backed figure, dressed in military uniform, appears from behind the widow as Anne bends over her husband’s corpse. Sensing his approach, she turns in revulsion to see the “fiend” and curses him, yet Richard is able to manipulate her emotions to the extent that she agrees to become his wife before the exchange ends. Even as the villain, the character’s Machiavellian powers of persuasion cannot fail to impress.

In reality though, Richard was an old friend, perhaps more. His father, the Duke of York, had married Anne’s great-aunt and the young Gloucester had spent several years living as Warwick’s protégée at the family home of Middleham Castle. The Earl may even have been the boy’s godfather. The children would have been brought together regularly, in ceremonial and informal situations, so it not impossible that an early friendship had blossomed between them, surviving Anne’s arranged marriage with the enemy. After all, her family’s sympathies lay first with the Yorkists, then with her Lancastrian husband: next she would marry the boy she had known, whose family had made her a widow. Shakespeare truncates this: Richard forces Anne to accept his ring alongside her husband’s corpse, despite her curses. The actual ceremony took place over a year later in July 1472 and the pair lived together, apparently in harmony for over a decade. It may even have been a love match. The eighteenth century Ricardian Horace Walpole mentioned that Catherine, Countess of Desmond described him as “the handsomest man in the room.” There is no denying though, that the alliance was financially expedient to both, so much so, that they were prepared to enter a marriage that was possibly invalid in the eyes of the medieval church. Together, they were crowned in 1483: Anne was Richard’s companion, his wife, the mother of his child and his queen. Did he then go on to murder her, as Shakespeare suggests ? McKellen shows a rapidly deteriorating Anne. The haggard appearance of the wife contrasts sharply with the earlier elegance of the widow. In the back of a limousine she hitches up her skirt and, according to McKellen’s screenplay, “finds the appropriate spot in her much-punctured thigh.” Her unnamed drug of choice is described in the screen play as “calming” and she closes her eyes and “waits for it to work,” while the orchestra plays triumphantly. Later she appears “doleful” and sad, later still, in a drugged stupor, in a world of her own and finally, catatonic. [3] The last the audience see of her is a motionless form, lying in bed with wide, staring eyes. A spider descends and lands on her face, scurrying away as she remains unblinking. McKellen’s Anne Neville is dead. Obviously, the fifteenth century Queen’s death was not attributable to recreational drugs but the rumours of her demise were just as sinister. Popular culture has upheld Anne as another of Richard’s victims, with Shakespeare placing her among the accusatory ghosts that disturb his sleep before battle. This is unsurprising as the circumstances of her death are shrouded in mystery and, for once, the corrective facts are harder to establish. In early 1485, the corridors of Westminster Palace whispered of jealousy, flirtations, affairs and illness, as some contemporaries suggested Richard might have been planning his second marriage while Anne was still alive, perhaps to a foreign princess, perhaps to his own niece.

Aged only twenty-eight, the Queen passed away amid an eclipse of the sun and the chroniclers were swift to draw their conclusions. Did Richard really play a part in her death; did he “eschew her bed” as she was fatally ill, possibly contagious? Was she poisoned to make way for a younger, more fecund model? Perhaps she was lovingly tended, yet unwittingly administered with medicines that could themselves prove fatal. The truth of Anne’s demise remained unresolved at the time and the dramatic regime change that followed compromised the objectivity of many witnesses and chroniclers. It is time to tease out the facts from the fiction.

Here's the scene from McKellen's film:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3wxGfjcfZkA&list=PLN1dkbJ9dexduepI1w7wK5FfQjdCPgPqu

Published on May 10, 2013 07:40

April 25, 2013

Educating Edward: What Sort of King Might Richard III's Son Have Made?

Edward of Middleham is most famous for having died young. Like his cousins, the Princes in the Tower, he was one of those many individuals who were briefly in line to the throne but never made it; one of history’s tantalising “what-ifs.” Another lost opportunity; the favourite food of historical fiction. Yet, certain clues suggest he might actually have made a good king.

Edward's parents, Richard and Anne

Edward's parents, Richard and AnneEdward was the only legitimate child of Richard and Anne, Duke and Duchess of Gloucester. His loss had significance far beyond the intense personal grief of his parents, who had by that time become king and queen. He appears to have often suffered from ill-health, forcing him to miss their coronation in 1483 and meaning he had to be carried on a litter to his investiture as Prince of Wales. Yet his father’s succession had come as a surprise to all. The boy’s namesake, the twelve-year-old Edward V, waiting in the Tower, had been anticipating his coronation that summer but had never made it into the Abbey. What a greater revelation was it then, to Richard’s son, who then learned he may one day become king ? Much of his life had been spent in his sick room: could he really rule England? It is impossible now to recapture anything about Edward’s character but one connection I explored whilst researching my biography of his mother, Anne Neville, shows us what would have been on the syllabus in the Middleham schoolroom.

Had young Edward lived to take the advice of his teachers, he could have proved a formidable opponent to Henry VII and a diplomatic ruler. Of course, the facts are the facts. After all, Richard was defeated on the battlefield at Bosworth and Edward of Middleham did die young. Hindsight tells us he would never sit on the throne of England. His suitability to rule is one of those “what-ifs” of historical speculation that allow us to glimpse tantalising alternatives. However, between June 1483 and April 1484, Edward’s future kingship was a very real possibility in which he and his parents could believe. The woman who presided over his nursery was well placed to prepare him for such a dazzling future.

The cenotaph in Sheriff Hutton Church that is reputed to commemorate Edward

The cenotaph in Sheriff Hutton Church that is reputed to commemorate EdwardEdward died on April 9 1484, aged somewhere between seven and ten. Little is known about his short life; even his birthdate is disputed, occurring somewhere between his parents’ marriage in 1472 and his inclusion in prayers offered for Richard and Anne, Duke and Duchess of Gloucester in the spring of 1477. He was born at Middleham Castle, where local tradition names one of the towers after him. The court rolls list an Isabel Burgh as his wet-nurse and the “mistress of the nursery” was Anne Idley, née Creting, from Oxfordshire. Anne had been widowed around the time of Edward’s birth and left her home at Market Drayton, to enter the Middleham household. Her husband had been Peter Idley, author of a book of manners, or education, for the rearing of boys, called Instructions to his Son.

Idley was contributing to an established tradition. The late fifteenth century saw a glut of instruction books, aimed at improving the manners of the aspirational middle classes in every respect, from dining etiquette, to appearance and protocol. The “Boke of Nurture,” the “Babees Book,” the “Young Children’s Book” and the “Book of Courtesy” were among many advising medieval “wannabes” to wash their hands and face, tell the truth and “let no foul filth” appear on their clothing. Idley’s Instructions were composed in the late 1440s, following his first marriage and the birth of his son John. Three decades later his widow, Anne, was the guardian of his book and his legacy. After she arrived at Middleham, John refused to pay her the annuity they had agreed, leading Richard to intervene to ensure the debt was settled. His father’s advice apparently had little impact on John but the future King’s son would have benefited from it instead.

As “lady governess” of Edward’s nursery, Peter’s widow would have overseen the arrangements for his education. It is not impossible that she taught him directly from the book herself. When she was employed by the Gloucesters, Edward never expected to be anything other than the nephew of the King, although it was crucial that he received a suitable training for this prestigious role. Idley’s advice is in two volumes, the first dealing with the theme of “wise business” and fickleness of fortune, while the second includes religious teachings and the handling of sin. Family connections and loyalty were important. A young man should leave idleness until his old age and “set his mind” to business, for the advancement of his friends and relatives. He should also honour his parents and see their blessing as a reward. His father’s advancing age should serve as a reminder to a “negligent” child that “after warme youth coometh age coolde.” In all dealings, he should be lowly and honest to rich and poor, in both word and deed, and respectful of his masters and superiors. It is no coincidence that the maxim “manners maketh man” dates from this period.

Discretion was considered important too. Idley advised keeping “within thi breste that may be stille” and not letting the tongue “clakke as a mille.” The avoidance of unnecessary conflict and the giving of offence are considered essential to personal control, as the “tonge” could give “moche pain” and “a grete worde may cause affray.” In fact, caution was a constant theme in the book. A boy should keep his ideas close “as thombe in fiste” and not be too keen to express an opinion, as it may lose him friends. He should aim for “meekness” as many had been “cast adoun” for their “grete pride.” Loyalty should be tempered by wisdom when it came to personal feelings.