Amy Licence's Blog, page 2

September 12, 2014

Review: George Boleyn: Tudor Poet, Courtier and Diplomat.

Ridgway and Cherry’s new Boleyn book could just be George’s marvellous medicine.[image error] George Boleyn has suffered from a bad press in certain quarters. Quite a lot of them in fact. In historical fiction and on TV, he seems to have been co-opted as the literary foil for his sister, from a reckless, hard-hearted homosexual to a ruthless adulterer who sailed too close to the wind. The biographical spotlight has rarely fallen on him in his own right, overlooking him in a way that has allowed for his reinvention as part of the narrative arc of his famous sister. Of course there have been hostile historical accounts too, putting words into his mouth that have festered into facts down the centuries, until George Boleyn has become more of a literary convention than a real person.This oversight is partly down to the lack of surviving material as, in the aftermath of the family’s fall in 1536, many of the traces of George’s life were probably destroyed. But it is also because no one has taken a dispassionate approach to analysing what remains. Until now. Claire Ridgway and Clare Cherry’s detailed and useful collaboration has explored this enigmatic man, shining light on areas such as his religion, politics and poetic work, that help reinstate George’s justifiable reputation as one of the most dazzling and talented members of Henry’s court. The exploration of his role as a courtier and diplomat allows the reader to see the full extent of George’s influence on some of the most important events of his time: as a member of the Reformation Parliament, as Ambassador to France and advocate for royal supremacy, he served Henry’s interests on the international stage. This book presents a new George, a man whose abilities and talents deserve to be seen independently from his downfall. Of course, though, it also explores in detail the most contentious issues of George’s life; his relationships with his sisters and wife, which reached their dramatic conclusion in May 1536.George was a survivor. He came back from Wolsey’s attempted cull of Henry’s “minions” in 1525 and survived the dreaded sweating sickness in 1528, yet his closeness to his sister meant that he was sacrificed when Henry required her removal. Readers of Ridgway’s other books on Anne Boleyn and her blog and facebook page, "The Anne Boleyn Files," will be familiar with the accessible, inclusive style of her writing. You don’t have to know anything about George to enjoy this book, whilst those with a good grounding in his life will find themselves pleasantly surprised, perhaps even revising their opinions. It is very hard to write a biography of a leading historical figure about whom little material survives. Ridgway and Cherry have filled out George’s life admirably and honestly, acknowledging the line between facts and reasonable supposition: it is this ability to use relevant historical material sensitively that transforms dry biography into a readable and engaging life. An eminently useful and long overdue focus on one of the leading English figures of the 1530s.

Buy the book here: http://www.amazon.co.uk/George-Boleyn-Tudor-Courtier-Diplomat/dp/8493746452/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1410527763&sr=1-1&keywords=george+Boleyn

Visit Claire Ridgway's blog here http://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/

And her facebook page here: https://www.facebook.com/theanneboleynfiles

Claire is also launching a new Tudor Society. See her blog and page for details.

Published on September 12, 2014 06:16

May 23, 2014

Pandora’s Box of Richard III’s Bones Closed

High Court judge rules against Richard III reburial challenge.

One of the most familiar images of 2013 was the bones of Richard III. Exhumed, cleaned and analysed, they appeared on our screens, in books and newspapers, in all their medieval glory, the focus of a fascinating tale of loss and dicscovery. For twenty months, those bones have awaited reburial. Initially scheduled to take place in Leicester's St Martin’s Cathedral this May, the ceremony was delayed by challenges mounted in the courts earlier this year. Finally, following months of speculation and argument, the High Courts of Justice have today rejected the Plantagenet Alliance’s objections to the exhumation licence of the University of Leicester.

The remains of the controversial King, discovered in a city centre car park back in September 2012, have ignited dispute since their identity was revealed to the public last February. In the euphoria that followed, with the curved spine and the reconstructions of Richard’s face making news headlines, few could have predicted the acrimonious lengths to which some of his supporters would resort over the following year. Yet some were dissatisfied with the Leicester association, preferring him to be buried elsewhere. While Westminster Abbey and Windsor were ruled out, the main alternative emerged as York Minster. Richard was certainly of the house of York and his main adult residence was in Yorkshire, but these were not the only considerations.

The Plantagenet Alliance, a group of collateral descendants of the King, was established by Stephen Nicolay, who discovered he was Richard’s 16th great nephew in 2011. They presented the case that Leicester University lacked “sufficient interest” in the King’s reinterment, in comparison with their own, as his relatives. The courts ruled today that the relation of Mr Nicolay and others had been “attenuated in terms of time and lineage.” Thus, the span of over five centuries was deemed to be significant. Whilst the court recognised the descent and wishes of the Plantagenet Alliance, they established that this group only represented a very small percentage, a “tiny fraction” of those people possibly related to him and their report included the estimate that today, between “one and well over ten million” people might legitimately claim a similar degree of relation. The Alliance added that they had been denied a period of consultation regarding the arrangements prior to the investigation. Today, the court ruled that this would have been “premature and unnecessary.”

The question remained of Richard’s intentions and the nature of his death. The simple fact is, there is no evidence whatsoever to suggest where the King hoped to be buried. None of his actions can be interpreted in that light and no will survives. It is most likely that as an anointed King, he anticipated lying alongside his wife in Westminster Abbey. After all, he chose to bury her there in March 1485. While his affinity with the city is undisputed, the questions raised in court over the correct procedure for the respectful burial of his skeleton were primarily concerned with the legality of the original paperwork, regarding the intention of the dig and suitable provision for a King’s remains.

Back in 2011, when the excavations at Leicester were being planned by Ricardian Philippa Langley, who sourced the funding and saw the dig through, The Ministry of Justice advised that there was no “statutory criteria for deciding licence applications” and that each was considered on their own merits, although they acknowledged that this was an unusual case. From before that point though, the project had already been named “Looking for Richard,” so the possibility of discovering the King was clear, even if it was considered unlikely. Press conferences in Leicester on 24 and 31 August 2012 announced the dig’s purpose. There was never any doubt that Leicester University were hoping to find the missing King.

Still, no one really anticipated the actual discovery of his skeleton in situ on September 5. It had always been considered an outside chance, a brief dream that seemed too unlikely to come to pass. The University had a series of objectives, including establishing the location of the Grey Friars Church and finding the stalls within the choir; Richard’s final resting place was the last of their five aims. But, with the exposure of his spine, the careful excavation and a series of rigorous tests, including mitochondrial DNA, it was established beyond reasonable doubt what the University of Leicester had achieved. Provision had made for Richard’s reburial in St Martin’s Cathedral, Leicester, within four weeks, “in the unlikely event of” him being found. Plans were made for his tomb and the details of his reinterment, all within the remit of the original legal paperwork.

The High Court ruled that the challenge made by the Alliance was not to the exhumation, or to a Cathedral burial. It was only a question of location. According to today’s announcement, the Justices believed that quashing the original licence in response to this would render the University’s dig illegal, making it a retrospective criminal offense. They were not prepared to do this. Equally, no fresh exhumation licence could be issued, as the bones had been exhumed already. Nor did they uphold the challenge that the original licence should have been revisited in 2013, once Richard’s identity had been established, suggesting a consultation “by the back door.”

Richard’s remains were always going to be controversial. In a statement issued on May 23, the court confirmed they had taken into account the long-standing cultural representations of the King and the establishment of the Richard III Society in 1924, with the intention of reassessing his character and reign. However, its ultimate decision rested on the need for the law to proceed on a “principled basis” rather than making a special case for a historical figure. The three Justices involved, Lady Justice Hallett, Mr Justice Ouseley and Mr Justice Haddon-Cave, clarified that the present royal family are not descended lineally from Richard. In fact, “no one is.” The Queen and Royal Family were consulted and expressed no concerns regarding the intention to rebury Richard at Leicester. The debate was also raised in Parliament, where the same statement was made. From February 2013, the position of York Minster regarding Richard’s remains has also been neutral.

The Court concluded there were no grounds for its intervention in the case and the Alliance’s call for a Judicial Review was rejected. It recognised the considerable investiture of Leicester Cathedral in preparing a suitable resting place for an anointed King. Now, it only remains for the date to be named. Hopefully, today’s ruling will open the door for England’s last Plantagenet King to be lain to rest in a respectful and fitting manner in St Martin’s Cathedral, Leicester. Initial reports suggest this will take place in the Spring of 2015.

Published on May 23, 2014 05:48

May 9, 2014

There's More to Thomas More than meets the Eye.

Who was Richard III’s greatest enemy? The obvious answer might be Henry Tudor, Henry VII, who defeated and killed the last Yorkist King at Bosworth in 1485. Others might cite Shakespeare, whose compelling portrayal placed the image of the hunch-back at the heart of later cultural representations. Some may even follow the Bard’s line by suggesting Richard was his own worst enemy, a classic over-reacher in the Marlovian model. Next on the list, reserved for a particular type of Ricardian derision, is the humanist scholar Sir Thomas More.

There is little doubt that More’s unfinished “history” re-enforces many of the excesses of anti-Richard myth, portraying an archetypal tyrant who removes his innocent nephews in cold blood in order to achieve his long-cherished ambition. And there is no question that More made things up, in order to make his work more vivid and powerful. This has brought the opprobrium of militant Ricardians down upon his severed saintly head, reputed to have been rescued from Tower Bridge and smuggled to Canterbury by his devoted daughter. Some have gone to the lengths of refusing to read him at all, or ridiculing references to his work, making him some sort of literary pariah.

Revered in the Catholic Church for his martyrdom in 1535, More is still being vilified in certain circles as a liar, steeped in bias, a self-serving partisan. Yet to judge his account in purely historical terms is to overlook the conventions and genres of late medieval literature, which determined the author’s methods and intentions. It also fails to recognise the important bridge he provides between classical accounts and modern historiography. And nowhere, does it take account of More the man. Just as it would be anachronistic to judge Richard III according to modern sensibilities, the same mistake must not be made when it comes to his early biographer.

More was born in 1480. He was three and a half when Richard III came to the throne and five at the time of the battle of Bosworth, which drew the Yorkist dynasty to a close. The rest of his life was spent in the service of Richard’s dynastic nemeses, Henry VII and his son, Henry VIII. He was the London-born son of lawyer John More, who had won favour and the right to bear arms under Edward IV. In fact, his 1530 will included provision for prayers to be said for the souls of Edward and his family. According to More’s son-in-law, William Roper, John had been treated vindictively by Henry VII, whilst employed as a sergeant at law. This meant that More had little reason to write purely out of subservience to the new regime and may account for the absence of Henry from the work.

According to the custom of the time, the young Thomas was placed in the household of the Archbishop of Canterbury and staunch Lancastrian, John Morton. He would describe his tumultuous life as the “violent changes of fortune” from which he had “learned practical wisdom.” Morton was equally pleased with his protégée, nominating him for a place at Oxford University. It is likely that during this time, More absorbed his patron’s opinions and experiences of Richard; perhaps as his clerk, he even wrote up notes Morton had made during the 1480s. The seventeenth century Ricardian George Buck even suggested that Morton was the original author of the work, which More simply copied up. With Bosworth less than a decade away, it is “inconceivable” according to Professor Caroline Barron, that it was not a frequent topic of conversation.

More went on to be an advocate of Renaissance Humanism, of female education, a lawyer and Speaker of the House of Commons, Chancellor, a prolific author, political visionary and devoted family man. In 1512, when Under Sherriff of London, he began work on his “history” of Richard III and tinkered with it for seven years, during which time he also wrote his most famous work Utopia (1516) and was appointed a Privy Councillor to Henry VIII. In 1519, for some reason, he put his account aside, unfinished. It may or may not be significant that the year before, he had moved into Crosby Place, the London house owned and occupied by Richard during many of the dramatic events of his 1483 coup.

More’s depiction of Richard tallies with other early Tudor chronicles, authored by John Rous and Polydore Vergil. More adds to Rous’s horrific picture of Richard’s birth, following a reputed gestation of two years, with the imagined details that he was breech-born, his head covered with hair and a mouth full of teeth. These would prove a gift to Shakespeare eight decades later and enter the literary canon as portentous of the king’s tragic fate. Soon though, sceptical voices were raised. Given the unlikeliness of More’s details, Enlightenment historians began to question why they, and other obvious fabrications, had been included in the account. The answer lies in the question of authorial intention. There is no doubt that More blends fact with fiction but this is exactly what his chosen genre dictated. He would have been remiss not to exaggerate, when his aim was to write within the didactic conventions of instructional literature.

More’s “history” is not history as we would recognise it; the term was synonymous then for “account” or “story”, a vehicle for a narrative in the classical model. True to his education and early Renaissance context, he followed the example set by the “histories” of Tiberius, written by Roman authors Tacitus and Seutonius. According to John Jowett, of the Shakespeare Institute, it “lays the foundations for modern historiography” by rejecting the linear portrayal of events in favour of an “admonitory narrative of people acting out their lives under the eyes of God.” More’s account must be seen within the context of late medieval literary tradition, with its emphasis on hagiography, miracle and morality plays and abstract virtues and vices. Whilst living with Morton, the young More also acted in early dramas by Henry Medwall, one of which, Nature, employed the abstract personification of “Pride”, who disguises himself to the audience as “Worship.” By 1513, More was well versed in the literary abilities of villains to conceal their true motives.

He also knew how the other half had lived. Saints’ lives was a very popular genre for the late medieval literate classes. A thirteenth century collection, The Golden Legend, was a bestseller by More’s day, having been copied into over eight hundred manuscript versions, then printed into every major European language. William Caxton brought out an edition in 1483, which was then reprinted nine times before 1527. As a devout Catholic, who was martyred resisting Henry VIII’s reforms, More was steeped in such tales. The usual hagiographic conventions included a birth attended by symbolic features, fictional episodes including conversations and flights of emotion, as well as historical facts. Saints were born to the fluttering of pure white doves and the ringing of bells. These literary signifiers gave less literate readers or listeners an easy shorthand to delineate the good from the bad, just as the costumes and props did in mystery cycles. Thus Richard’s tale of ignominious defeat required the apparatus of an ill-fated birth and physical deformity. Saints’ lives were important vehicles for the study of the past, intended to inspire the living to greater piety.

Yet More did something different with the genre. In taking Richard as his anti-hero and subjecting him to the rules of hagiography, he was not preaching the usual lesson. Instead he was teaching by negative example, creating a dramatic and sometimes terrifying tale that blended recent memory with the stuff of nightmares in order to show the consequences of misplaced ambition. Richard is his instrument in this, a conveniently memorable figure who served a literary purpose. Like Shakespeare, militant Ricardians may not forgive More for selecting the Yorkist King as his subject matter but for an author writing in the medieval tradition, Richard was a gift of a topic. Hindsight made him the perfect teaching tool.

More’s anti-hagiography can be seen as a partner work to the biography he wrote in 1510, the Life of John Picus. Derived from the life of Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, it outlined the virtues of the Italian Renaissance philosopher who was poisoned in 1494, probably on the orders of the Medicis. Thus More co-opts two real historical narratives for the benefit of future generations, in the hope that they would not “decline from the steps of their virtuous living” and that such example would “maketh the dark spot of our vice the more evidently to appear.” This was also within the spectrum of instructional literature of the day, encompassing moral fables and behaviour manuals which enacted learning by example in the same way as parables read in the pulpit. In 1522, More wrote the very specific Four Last Things,warning his readers against pride, envy, sloth, gluttony and covetousness. He also produced a number of animal fables. There was little difference to him between animating abstract vices, creatures, classical Gods and the recent dead. All offered the opportunity to teach the living.

More’s work was also a reflection of evolving political models. He cast Richard as an ambitious villain, plotting to usurp the throne even before the death of Edward IV. This scheming, one dimensional version may have been accomplished by More mapping Richard’s story over the literary model of the Machiavel. In fact, Niccolo Machiavelli’s manuscript of The Prince was being circulated among his correspondents and humanist friends well in advance of its 1532 publication. One of its chapters deals with “conquests by criminal virtue” in which a Prince secures his power through cruel deeds and the execution of his political rivals. Machiavelli’s advice was that all such acts should be carefully planned then executed in one swift blow, to allow his subjects the opportunity to forget them. It was only recently that the extensive correspondence between Machiavelli, Erasmus and Thomas More was discovered in the Palazzo Tuttofare in Florence, exploring questions about methods of governance and the nature of writing. More’s Richard III stands at the interface of these.

Of course, none of this is to deny that there are problems with More’s account. Just as with any historical source, it needs to be considered in context and evaluated according to the light it can shed, if any, on the true story of Richard III. However, that context is very much a literary one as well as a historical one. Calls to reject More’s work out of hand fail to do precisely that which they assert as essential: More must not be simply read and digested, he must be used with caution within a framework of contemporary cultural influences. As a master of his craft, he deserves to be read afresh and placed firmly back within the Ricardian canon.

More was a man with a conscience. Having agreed to enter the service of Henry VIII on the provision that he be allowed to act according to his scruples, he had not banked on the momentous religious reforms that his King was to introduce in the 1530s. Refusing to swear allegiance to Henry according to the Act of Succession, he was convicted of high treason and beheaded in July 1535. On the scaffold, he was reputed to have said that he remained God’s servant first and the king’s second. His unfinished account of Richard’s life and reign was published after his death. Perhaps the key to rejections of his writing is explained by the clash of ideologies: ultimately his use of the hagiographic conventions has little in common with the deluded deification of Richard which takes places in some forums. There really is more to More than may appear.

Published on May 09, 2014 11:06

March 28, 2014

Rifling through our Great-Grandmother’s Drawers: What Domestic History Reveals About our Modern Selves.

What did medieval Londoners use to treat colicky babies? Why were they punished for wearing twenty-foot long shoes? What did they wear in bed? A recent trend in popular history provides the answers to such domestic questions in lurid and often grisly detail. If publishing and TV viewing figures are anything to go by, twenty-first century readers love these anecdotes about the daily lives of their ancestors, and witnessing re-enactments of past life. Yet there is more to this increasing fascination with the bedpan: for readers, many these books will parallel a personal journey. The meta-modern interest in domestic history might be a reassuring tool in an increasingly uncertain world.

The pendulum of history swings between battlefields and butterdishes. Following the late twentieth century’s focus on microhistory, which produced such fascinating studies as Carlo Ginzburg’s “The Cheese and the Worms” and Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie’s “Montaillou,” many historians have followed the tradition of focusing in on the minutae of life in a particular place or time. Traditionally the narrative of the lives of great men, as evidenced by the essay written by Virginia Woolf’s 1922 eponymous hero, Jacob, history has been wrested away from the council chamber into the bedchamber. Modern readers are fascinated by the intimate, private nature of human existence over time: the remedies for coughs and colds, the charms recited in childbirth or the many uses for nettle leaves. This is unsurprising, as such small details simultaneously remind us of our difference and similarity with our ancestors.

Recent studies of the domestic sphere have been vividly entertaining and bring the past to life in a way that makes it immediate and accessible. Amanda Vickery’s romp through Georgian bedrooms is aptly titled “Behind Closed Doors” and Lucy Worsley’s intimate history of the home bears the name “If Walls Could Talk.” These books place the reader in a voyeuristic role, as modern ghosts, able to time-travel through their pages and witness the private acts of eating and washing, childbirth and sex. It creates a sense of reassuring omnipotence along with the thrill of spying on our ancestors. And perhaps that is where the attraction lies; in laying bare the laundry of the dead, we are reminded of our origins and direct linear connection with them. That’s how they did their washing; this is how we do ours. Such books give credence and importance to the contents of the rubbish tip and personal habits. In turn, this reflects on the disposable, routine details of our own modern living. Witnessing this continuity validates the often-tedious daily routines of our own lives. Living is an art form: we are part of the continuous process. Our works of art are the meals we cook, the homes we decorate, the persona we sculpt in social media. We can’t all be historically important, but in the future, someone in a museum might be looking at our old washing machine!

Domestic history creates a paradox of otherness and similarity for the reader. Ian Mortimer’s “Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval History,” recently a popular TV series, consciously creates a divide between the people of past and present, reminding us that we are moving back in time to a place where things are done differently. Written and presented as something of a survival guide, it creates a dialectic of opposition: the medieval world is a place where the modern reader is under threat and requires the historian’s advice to escape intact. Thus Mortimer is the conduit and protector of his reader against disease, disorder and alien customs. This differs slightly from the approach of historians like Toni Mount, who bring the past into the present world, throwing open the doors of the bedchamber for a modern audience to participate in, creating an illusion of a temporary simultaneity of eras. As a re-enactor, Mount’s long-standing skills in practical history: cooking in medieval pots and wearing clothes cut to their cloth, lends her new book “Everyday Life in Medieval London” a wealth of fascinating practical detail. The increasing popularity of individuals and companies who dedicate their weekends to recreating the past is further testimony to the increasing desire to overlay our modern lives with those of our ancestors.

Perhaps most powerful, is the personal involvement of the reader or audience. The recent accessibility of online records has facilitated the beginning of millions of journeys of rediscovery. Using sites like Ancestry.com, it is possible to trace back your family tree through the generations and, with a few online clicks, discover the names, locations and professions of your great-great grandparents. Not so long ago, this process would have involved lengthy journeys to record offices, perhaps scattered around the world, and the decoding of yellowing pieces of paper. This could require considerable historical and medical understanding or even require palaeographic skills. Now, we are seeking to make sense of what we learn by understanding the world in which our relatives lived. It is the next best thing to having a conversation with them.

Objects have power. Those items that are passed down through the generations; your grandfather’s pipe or your great-grandmother’s watch create a direct connection, cupped in the hands of their direct descendants. They provide a tangible link between us and those whose bloodline we share, more intimate and powerful than the grave. Holding them is a substitute for holding the hand of our ancestor. It is little wonder then, that we are also fascinated by items that are their parallel in time: a museum tea-cup made in the same year as our mother’s brooch or a display of recreated life in the Victorian era. Standing on the other side of the rope, we can imagine ourselves walking into the scene and interacting with our long-dead family. Perhaps sitting beside them on that sofa or playing a duet on that piano. The popular history books and TV programmes that explore these domestic environments provide us with universal talismen, symbols that connect the modern Everyman with past narratives. Perhaps they are the twenty-first century’s secular substitutes for Freud’s “oceanic feeling” of limitless and belonging.

What is the gap in the modern mentality that domestic history fills? In a world that seems increasingly disposable and random, prey to horrific acts of terrorism, this sense of continuity acts like an anchor, providing reassurance that we are part of a chain. It creates a solidarity with our relatives, who lived through wars, famines and other disasters. A knowledge of their lives allows us to reassure ourselves that their sacrifices and struggles were worth it, because we are the outcome. Our own struggles, therefore, retreat into historical perspective. This doesn’t make domestic history an egotistical history. It makes it an important tool for modern individuals to make sense of their own identity and resolve some of the dilemmas of the post-post-modern, or meta-modern world. Domestic history is armour.

Books such as those by Worsley and Vickery, Mortimer and Mount, are fascinating and delightful reads. They allow us to dip in and out of the past and appeal to our senses with revolting anecdotes and the touching details of individual stories of objects, buildings, locations and specific people. They are history for the sake of history, pure enjoyment to read. Yet they are also part of a significant new phenomenon, in that they act as conduits to our personal pasts. They are the accessible doors to individual and collective identity. We may not all have ancestors who graced the hallowed halls of palaces or government; our forebears may have lived quietly, humbly, in modest professions, and such books help us to see the significance of these lives and, by extension, our own. Why are we all so fascinated by domestic history these days? Because we are all living it, today.

Published on March 28, 2014 05:09

February 9, 2014

Amy Licence's new Website

Hello all, I'm finding with all my writing commitments that I'm having less and less time to keep up with this blog. I will be posting some guest writers and updating it occasionally but now I'm launching a new website for all my writing. On it, you can see what I'm working on at the moment, read samples of my published work and ask questions.

Thank you for all your support.

You can find the website on:

www.amylicence.weebly.com

Thank you for all your support.

You can find the website on:

www.amylicence.weebly.com

Published on February 09, 2014 12:05

January 22, 2014

Capturing the King's Face: An Interview with Laurie Harris, the artist behind a new portrait of Richard III.

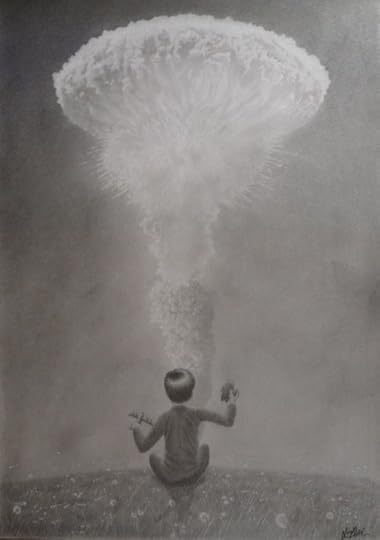

My new book, "Richard III: The Road to Leicester," features a fascinating new interpretation of the King by an exciting young artist, Laurie Harris. I spoke to Laurie about the way he approached the portrait, his thoughts about the man and his influences:

Richard III by Laurie Harris

How did you research the portrait?

Perhaps the core objective I set myself for this new portrait of Richard III was to produce a recognisably human figure we can all, to some extent, connect with. This involved stripping back some layers of royalty and title, and presenting an altogether plainer vision which lends itself to graphite and charcoal. The tonal range cleaves closer together and unifies the image in its ordinariness and essence, which helps to divest some of the grandeur of Richard’s position. This is an aspect I thought lacking in other pictures I have seen of Richard III, which contrast the figure more starkly against his robes and riches. Most keenly was this brought to my attention when I visited London to observe the two anonymously authored 15th/16th Century colour portraits housed in the National Portrait Gallery. Richard is depicted with a pained expression (in fact not unlike the expression in my portrait), dressed in all his finery, and ambiguously fingering his ring. (Students of semiotics could have a field day!) To me these paid close attention to the dynamic of and contrast between the man and the title, thereby manifesting a political intention, which I can say did not intentionally factor in to my designs. Aesthetically I took much greater interest in capturing the scientific reality of Richard – that is, closely analysing the recent reconstruction of his face put together by a team at Leicester University using the craniometry of his recently unearthed skull. The bust they produced was a revelation but, to my eyes at least, a little stale and lacking vitality. So I went about trying to inject some emotion, some humanity and some life, as better identified in the earlier portraits. Thus, the combination of a scientific foundation and a human interest sensibility perhaps makes my portrait a very contemporary production.

What impressions did you draw of Richard and how did you convey them in the drawing?

I was aware of some of the controversy surrounding Richard III. Certainly this is a man whose reputation and legacy remains fluid and indefinite, and it is perhaps that contestation and dispute that account for his endurance in the public imagination. Shakespeare’s ‘Crookback’ characterisation of course has done much to guide public perception through the ages, but the posthumous play seems likely part of a Tudor propaganda offensive used to discredit Richard and distort or embellish real truths. The question of whether the ‘disappeared’ Princes in the tower, Richard’s two nephews, were executed by Richard remains a pertinent one. To my mind, any ruler seeks to legitimate his or her right to rule whether through ancestry, ritual, myth-making, or plain bloodshed, so the question I posed myself was how ruthless was this man’s desire to rule? Would he kill his nephews without feeling? Would he kill them with profound conflict? Would he kill them at all? To that extent I weighed down more sympathetically on Richard. I wanted to eke out something of the man, and thus rather suggest the crown through the man. In that sense I tried to convey something of the human impact of Kingship, such as those revealed by the fate of his nephews. To this extent I suppose I am intimating a certain humanity and feeling to Richard, which perhaps courts as much controversy as befits the figure.

What are your influences as an artist?

When I was young my parents read a story to me called ‘Christopher and the Dream Dragon’, written by Allen Morgan and illustrated by Brenda Clark. The pictures were greyscale and the story of a boy who has to recover a coin from the dragon’s golden hoard nestled away amongst the clouds really shook my imagination. Perhaps I can say that since that point, fantasies, myths, fairy tales and high adventures (culturally coloured throughout the world) have been my home away from home. Pictures, as words, are dialogical. And like words they are both aesthetic and conceptual. In this way pictures are the very fabric of storytelling. Certainly I like to see the pictures I create as telling or being a part of some kind of story, however small and inconsequential. My intention is for them to exist as a moment caught in a long timeline of a past and future in a real or abstracted world. Therein lies the narrative possibility. So when I think about influences, I am certainly thinking as much about stories as I am about art. These influences spread across multiple mediums including literature, film, documentaries, music, and so on. Particularly I would like to mention the work of Japanese animation house, Studio Ghibli, whose films continue to inspire me both through their bewitching visuals and the power, emotion, and brio of their storytelling. I share with them a wonder and reverence of both subtle and outlandish fantasy, and remain indebted to them in that respect. A few other notable visionaries that have fired my ambition and fed my imagination are the fairy tale artist and old favourite, Arthur Rackham, father of modern fantasy, J.R.R. Tolkien and his artists Alan Lee and John Howe, and the lyrical and bittersweet fantasies of Japanese author Osamu Dazai.

What are your future plans?

Reflexivity is a great asset to an artist (and indeed perhaps a curse!). Among critics of my picture, I am perhaps king (pun vaguely intended) – although perhaps that will change once this portrait is in print! But that self-criticism motivates me to improve with each picture, and demands each picture pushes my ability, both technically and methodologically. In short, I still have everything to learn, and this is just the beginning. I hope that getting my work out there might increase the possibility of producing more work for other projects, and open other pathways and opportunities that allow me to improve my skills and better articulate my ideas. Specifically I would like to illustrate children’s books, or even develop a story from scratch and run with that, with the ambition both of strengthening my portfolio and producing ever-more professional, atmospheric and imaginative work.

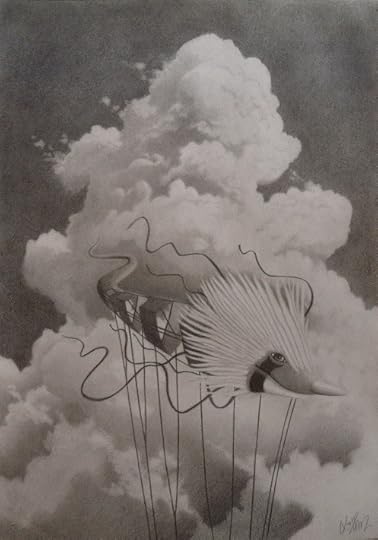

More work by Laurie:

Artist Laurie Harris

You can see Laurie's work at www.rie-zaki.deviantart.com

All the pictures on this post are @Laurie Harris. You may not reproduce them without the artist's permission.

Richard III by Laurie Harris

How did you research the portrait?

Perhaps the core objective I set myself for this new portrait of Richard III was to produce a recognisably human figure we can all, to some extent, connect with. This involved stripping back some layers of royalty and title, and presenting an altogether plainer vision which lends itself to graphite and charcoal. The tonal range cleaves closer together and unifies the image in its ordinariness and essence, which helps to divest some of the grandeur of Richard’s position. This is an aspect I thought lacking in other pictures I have seen of Richard III, which contrast the figure more starkly against his robes and riches. Most keenly was this brought to my attention when I visited London to observe the two anonymously authored 15th/16th Century colour portraits housed in the National Portrait Gallery. Richard is depicted with a pained expression (in fact not unlike the expression in my portrait), dressed in all his finery, and ambiguously fingering his ring. (Students of semiotics could have a field day!) To me these paid close attention to the dynamic of and contrast between the man and the title, thereby manifesting a political intention, which I can say did not intentionally factor in to my designs. Aesthetically I took much greater interest in capturing the scientific reality of Richard – that is, closely analysing the recent reconstruction of his face put together by a team at Leicester University using the craniometry of his recently unearthed skull. The bust they produced was a revelation but, to my eyes at least, a little stale and lacking vitality. So I went about trying to inject some emotion, some humanity and some life, as better identified in the earlier portraits. Thus, the combination of a scientific foundation and a human interest sensibility perhaps makes my portrait a very contemporary production.

What impressions did you draw of Richard and how did you convey them in the drawing?

I was aware of some of the controversy surrounding Richard III. Certainly this is a man whose reputation and legacy remains fluid and indefinite, and it is perhaps that contestation and dispute that account for his endurance in the public imagination. Shakespeare’s ‘Crookback’ characterisation of course has done much to guide public perception through the ages, but the posthumous play seems likely part of a Tudor propaganda offensive used to discredit Richard and distort or embellish real truths. The question of whether the ‘disappeared’ Princes in the tower, Richard’s two nephews, were executed by Richard remains a pertinent one. To my mind, any ruler seeks to legitimate his or her right to rule whether through ancestry, ritual, myth-making, or plain bloodshed, so the question I posed myself was how ruthless was this man’s desire to rule? Would he kill his nephews without feeling? Would he kill them with profound conflict? Would he kill them at all? To that extent I weighed down more sympathetically on Richard. I wanted to eke out something of the man, and thus rather suggest the crown through the man. In that sense I tried to convey something of the human impact of Kingship, such as those revealed by the fate of his nephews. To this extent I suppose I am intimating a certain humanity and feeling to Richard, which perhaps courts as much controversy as befits the figure.

What are your influences as an artist?

When I was young my parents read a story to me called ‘Christopher and the Dream Dragon’, written by Allen Morgan and illustrated by Brenda Clark. The pictures were greyscale and the story of a boy who has to recover a coin from the dragon’s golden hoard nestled away amongst the clouds really shook my imagination. Perhaps I can say that since that point, fantasies, myths, fairy tales and high adventures (culturally coloured throughout the world) have been my home away from home. Pictures, as words, are dialogical. And like words they are both aesthetic and conceptual. In this way pictures are the very fabric of storytelling. Certainly I like to see the pictures I create as telling or being a part of some kind of story, however small and inconsequential. My intention is for them to exist as a moment caught in a long timeline of a past and future in a real or abstracted world. Therein lies the narrative possibility. So when I think about influences, I am certainly thinking as much about stories as I am about art. These influences spread across multiple mediums including literature, film, documentaries, music, and so on. Particularly I would like to mention the work of Japanese animation house, Studio Ghibli, whose films continue to inspire me both through their bewitching visuals and the power, emotion, and brio of their storytelling. I share with them a wonder and reverence of both subtle and outlandish fantasy, and remain indebted to them in that respect. A few other notable visionaries that have fired my ambition and fed my imagination are the fairy tale artist and old favourite, Arthur Rackham, father of modern fantasy, J.R.R. Tolkien and his artists Alan Lee and John Howe, and the lyrical and bittersweet fantasies of Japanese author Osamu Dazai.

What are your future plans?

Reflexivity is a great asset to an artist (and indeed perhaps a curse!). Among critics of my picture, I am perhaps king (pun vaguely intended) – although perhaps that will change once this portrait is in print! But that self-criticism motivates me to improve with each picture, and demands each picture pushes my ability, both technically and methodologically. In short, I still have everything to learn, and this is just the beginning. I hope that getting my work out there might increase the possibility of producing more work for other projects, and open other pathways and opportunities that allow me to improve my skills and better articulate my ideas. Specifically I would like to illustrate children’s books, or even develop a story from scratch and run with that, with the ambition both of strengthening my portfolio and producing ever-more professional, atmospheric and imaginative work.

More work by Laurie:

Artist Laurie Harris

You can see Laurie's work at www.rie-zaki.deviantart.com

All the pictures on this post are @Laurie Harris. You may not reproduce them without the artist's permission.

Published on January 22, 2014 03:35

January 2, 2014

Are DaVinci's Demons Really Demons?

Popular belief vs. reality or science, a study of beliefs in the Middle Ages

A guest post by Andy Mcmillin

“ ‘Let the churches ask themselves why there is no revolt against the dogmas of mathematics though there is one against the dogmas of religion. It is not that mathematical dogmas are more comprehensible. The law of inverse squares is as incomprehensible to the common man as the Athanasian Creed. It is not that science is free form legends, witchcraft, miracles, biographic boosting of quacks as heroes and saints, and of barren scoundrels as explorers and discoverers. On the contrary, the iconography and hagiology of Scientism are as copious as they are mostly squalid.’ ” Medieval Minds pg. 39

Being a medievalist, we seem to be attracted or notice the oddities or subtle details in TV shows and various movies. In fact, I am drawn to the historical points or even inaccuracies in modern story telling, probably more often than not. While watching “DaVinci’s Demons”, this fascinating show struck a very interesting bit with my perception and knowledge of what we know about faith versus reality or science in the Middle Ages. The series is based around the earlier years of Leonardo DaVinci and his struggles to find a benefactor for his works. The show also has its setting in the middle of the vast conflicting and complex world of the Italian Renaissance. In watching the show, I can see perfectly where Shakespeare got his inspiration for “The Merchant of Venice” and “Romeo and Juliette.” Feuding and backstabbing, gain a new meaning in this show, yet the idea of science versus religious doctrine and the belief of the average medieval mind is hard to ignore.

In episode 3, “The Prisoner,” we gain a glimpse of how medieval or in this case renaissance society perceived mental illness or any illness that plays havoc with one’s psyche versus popular belief (the not so educated medieval man) which was, if you had something going on in your head; you were possessed by demons and or a witch. In this episode, it is not just normal peasants who are the ones doomed, but individuals close to God, nuns at a near by convent.

Word gets out that some thing is amiss and Leonardo and his crew are asked to investigate and find out what is causing the illness to befall the nuns. The Pope’s exorcism team later joins them, for they heard the nuns were possessed and needed salvation. Unfortunately, they do more harm than good. While the exorcisms are deemed helpful, and holy, a few people die as a result. The priest who does the exorcism claims on one case that he saw at ones very last breathe to be free from the ill that had befallen her, and she was in fact saved. To them, the ill are damned, possessed, and there is no other reason for their maladies, it is all a result from sin hence exorcism is the only way they can be cured. Leonardo at a few times himself suggests that it is something else making the women sick, but the head priest simply denies his ideas. This is a good example of how a modern approach to history can show how conflicted society was between the notions of science and teachings of the church during this time.

Now it is time for me to be the historian. What does this tell us about medieval society? A few things actually. It shows how easily, even a somewhat educated population can be convinced of a popular notion by a powerful entity. This is the devil’s work so they were told and there cannot be a scientific explanation; it was God’s will. The goal of the church at this time was to keep the pennies coming in on Sundays, install fear, and get motivation for people to avoid sin. In short come to church, pray, give offerings, and be protected from demons or other temptations. Back at the convent, Leonardo and his scientific knowledge eventually proves the cause of the demonic possessions is red ergot poisoning, which is has a fungus called Claviceps purpurea which also caused ergotism, on the statue. It is that fungus which is causing the nuns to become ill and causing their altered mental state. It is also noted that this problem with red ergot poisoning was also responsible for other outbreaks of similar circumstances in the Middle Ages. Notable outbreaks such as one in the 12thcentury recorded by Geoffroy du Breuil of Vigeois in France. Previous outbreaks gave the disease the name “St. Anthony’s Fire” named after the monks of St. Anthony who had been known to successfully treat the condition. When one is ill with this ailment, symptoms arise such as convulsive symptoms, seizures, mania, psychosis and headaches. In addition there are gangrenous symptoms from the poisoning that affect the poorly vascularized structures of ones body such as their toes, and fingers, loss of feeling and peeling of the skin. It is noted that this poisoning was responsible for the explanation of witchcraft, which would have been why the church’s exorcist was called in. (source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ergotism)

Now, why did this happen what lead people to think this way? It gets down to power and control. The church at the time was vast. It encompassed most of Europe and was if not richer than the kings and queens, but the most powerful entity in existence and in Christendom. How did they get this way; through deception, and influence, popular favor, as well as making sure the masses i.e. peasants or common folks believed everything they were told so they would get their backing and funds (via offerings from the peasants and nobles). To put it simply, everyone wanted to be saved by God at the time of final judgment. The sheep followed their shepherd quiet close during this time because no one wanted to face the fiery furnaces of hell. The easiest way to do this was make people believe, what they said by all means possible, even if that meant installing fear in the uneducated, and making examples of those who where so called “damned.” Exorcism, execution of witches; all were used to show society and teach that sin was bad, and those who walked on the line of thought or ideas outside of the norm whether they were ill or not, needed to be cleansed. If the church exorcised or cleansed a witches soul via penance, which resulted mostly in death, they gained salvation and a place in heaven.

In addition, there was a general fear that by denying someone’s means to salvation, was just about the quickest way to get any person to follow the word of God. The common peasant isn’t going to think of a cause for an illness or an event like Leonardo did; but they will believe the misfortune that falls upon them as a result. Because most of the population was not educated to what we would think of today, convincing a popular belief was quite simple and easy to manage. This is the same concept if one looks at mental illness, which the poisoning did cause and also shows this relationship.

How the medieval mind and the church perceived mental illness is a tricky subject but it has its similarities as it involved the church, popular belief, and limited medical intervention and knowledge. Unfortunately the monks of St. Anthony were not able to cure this. Because of the misunderstanding and lack of knowledge for these conditions, it created stigmas in society that took quite some time to get rid of and as a society even now; we still struggle with this stigma today. Some the best accounts and glimpses of how mental illness was perceived during this period is through accounts from some of the patients themselves, King Henry VI of England and France and his great-grandfather, Charles VI of France

It was well known Henry VI of England, had bouts of insanity and psychosis. His turbulent lifestyle and political unrest of his country didn’t help his condition. The stress of his position contributed to break downs especially in the summer of 1453. This breakdown would start, that would later leave him in total withdrawl, total mental and physical psychosis. Reports stated that he was completely oblivious to the world around him, thus unfit to rule. This was when Richard of York was named Lord and Protector of England. Family and familiar faces were unknown to him and even with the birth of his son Edward, brought no change in his demeanor or condition. Yet even in this state, he was cared for in the best of care partly because he was a man of office or high station. The regular person or peasant would not have had this luxury and the conditions were not even close as far as treatment. There is record that physicians at the time tried medications, syrups, potions, and bloodletting and even shaved his head believing that it would “purge him and rid the brain of its black bile and so restore the balance of the humors.” “The humors” it was thought if unbalanced caused such conditions. The theory that they had to be balanced was highly practiced and believed during the middle ages. The humors were four basic principals of medieval medicine: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. All were essential for one to be in harmony and in good health. Some of the medical treatments on King Henry VI exhibit this notion and seek to find a balance of these humors which were thought to be unbalanced and causing his illness, such as blood letting. But the king’s madness was not as simple as poisoning from a fungus found in bad grain or wheat nor was it able to be balanced out by bloodletting; it had more than likely a genetic component.

As historians we research, we dig and sometimes we find something that links the puzzle together. In the case of King Henry IV, we just follow the family tree and surprise! Family history of a similar illness and across the straight to France our trail leads. Medieval France is a country with a good share and history of “mad” kings. First we have Clovis II in the 5thcentury, his great grandson Childreic III, known as “the idiot” and then later Charles IX, (1550-1574) was mentally unstable, known to be a sadist with mad rages. He had two sisters as well, who were noted to be “ill mannered and spoiled beyond redemption.” Perhaps the most famous mad king was Charles VI (1368-1422) who was Henry VI’s great-grandfather. Careful researching and back tracking has led many to find the source of his illness, from a line of family from his mother. This suggests that it was a hereditary disease in the family and had been for sometime, passing itself on down generation after generation.

From what we know today, schizophrenia or bipolar disorder could have also been passed down, and it has a very varied and large genetic component as far as heredity is concerned. It is also suggested that the disease porphyria was another diagnosis. Porphyria has been noted to be diagnosed in his relatives. It is a rare hereditary disease that has symptoms such as inflammation of the bowels, painful weakness of the limbs and sometimes loss of feeling. Some bouts of the disease can even bring on visual and auditory disturbances, causing delirium and later lead to senility or dementia. The close relations in families as well did not help the pool of genetic variation, thus the maladies of mental illness became more apparent as a result and continued to occur and be passed down.

It is also suggested that Charles might have had encephalitis, which could have led to many of the bizarre symptoms described. It is this theory that many have tried to make sense of his April 1392 illness. Typhus has also been suggested. The suggested evidence that it could have been encephalitis was the occurrences of fever, hair and nails falling out, behaving incoherently, bizarre behaviors such as killing four of his own men as a result of a dropped lance, all hold suggestion. Accounts read by a modern historian with a medical background such as myself, suggest that the following the mania, he had a psychotic break of fit, or maybe even a seizure. Then he suffered from heavy psychosis or coma for two days. To any medieval man, educated or not, watching the events unfold it would be completely feasible that one would think the king was in fact possessed.

He had another incident in 1393 where surgeons actually drilled his head (trepanning) with holes to release pressure or the cloudiness of thought he was said to have suffered, in his brain. This was followed again by a relapse in 1395. Then finally, a historic account of the most common belief; it was eventually believed by churchmen and university doctors that Charles was a victim of sorcery. They attempted to exorcise him in 1398, during which he was noted to have cried out:

“If there is anyone of you who is an accomplice in this evil I suffer, I beg him to torture me no longer but let me die.”

Unfortunately, as Charles got older, the fits came more often and lasted longer, suggesting the ailment he had grew worse with age and time. At one point in time he thought he was made of glass and would break into pieces. He even had people insert metal rods into his clothes so he would not break.

What we know of today, is that many of these so called demonic possessions which the church would have tried to exorcised say in the case of Charles VI, were in fact biologically, or genetically caused. Interestingly noted during the Middle Ages, most the European societies gave the mentally ill their freedom, which we see with Henry VI and Charles VI, unless they are a danger. This became the case with Charles VI after he killed four of his men. To the common medieval man, people with these disorders, were often pegged as witches and or possessed by demons. As time went on, the medieval and renaissance societies started to isolate mentally ill people out of fear of unknowing how to treat them and fear from harm from the individual. At times, a mentally ill patient would be locked up in a dungeon in chains, as inhumane as it sounds, it happened. (source: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/nash/timeline/)

Modern story telling, as seen with film and other venues, do help us teach history at level that is both easy accessible to the viewer and to the general public. The example given in the beginning of this discussion with DaVinci’s Demon’s accomplished this. It gave us a glimpse of a very important topic in medieval society, which is the notion of popular belief versus reality or scientific cause. In this case, demonic possessions versus a scientific cause of a condition, causing temporary insanity and how this was translated to the general public. In addition to this one cannot help but notice the closeness of the church and secular society were intertwined in the Middle Ages. It is because of this these ideas were developed and continued on in society. As discussed, some of the sources of these interpretations have roots much earlier in society, especially within the ruling class. Finally, if we look how these conditions were treated back then and compare the practices to today, it shows how a society we have evolved to not just believe what is said, but to look and delve for the answers that we cannot necessary see but to look for the scientific cause not just the will of God in the sakes of our salvation.

Sources:

1. Graham, Thomas F. Medieval Minds, Mental Health in the Middle Ages. George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London, UK c. 1967

2. http://madmonarchs.guusbeltman.nl/madmonarchs/charles6/charles6_bio.htm

3. http://madmonarchs.guusbeltman.nl/madmonarchs/henry6/henry6_bio.htm

4. http://www.medievalists.net/2013/12/0...

5. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/nash/timeline/

6. http://www.maggietron.com/med/humors.php

7. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ergotism

By Andrea C. McMillin - B.A. Medieval Studies from University of California at Davis

A California native, Andy obtained her Bachelors of Arts degree in Medieval Studies from UC Davis in 1998. She has done graduate work in History in the past and is currently taking film and medical classes locally in Salt Lake City, Utah. She hopes to finish her degree at the University of Edinburgh via their online History MA program in 2015. When not writing/researching or working, she enjoys cooking, creating artwork, photography, and actively competes with her horses.

Her blog can be found here: http://medievalessays.blogspot.co.uk/

Published on January 02, 2014 03:45

December 9, 2013

Holbein and a Tudor World in Miniature: A Marriage Made in Heaven.

Holbein, miniature painting, identity and wealth: a guest post by L B Hathaway

I was lucky enough recently to find myself quite alone in gallery 643 of the Metropolitan Museum(the Met) in New York. As crowds rushed past on their way to ogle the deserved glory that is the Rembrandts, the palm-sized portrait of an Official from the Court of Henry VIII (the Portrait of a Man in a Red Cap), sat unnoticed in its display-case. But to its now-unknown sitter, it may have represented the most costly investment of his life. It was painted in 1534 by Hans Holbein, the German artist whose growing reputation and unnervingly-brilliant talent meant that by 1534, on his second stay in England, he was the hottest painter in town. He was much in demand, being taken up especially by the Boleyn faction at Court. Holbein started to paint miniatures (or ‘limning,’ as it was known) in around 1532, quickly surpassing Lucas Horenbout, the ‘Kings Own Painter,’ in artistic genius.The Portrait of a Man in a Red Cap is bigger than a miniature, but is still tiny, and it is painted in ‘miniature’ style. Stylistically, it is closest to a pair of paintings of Court Officials by Holbein now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Traditionally, historians have argued that the pair in Vienna represent Susanna Horenbout and her English husband, John Parker, and that the man in the Portrait of a Man in a Red Cap is in fact Susanna’s brother, the famous ‘King’s Painter’ himself, Lucas Horenbout. Whilst this opinion has been advanced over the last hundred years, recent publications have now thrown doubt on all three of these sitter’s identities. It is safe to say there is a lack of any corroborating evidence for Lucas Horenbout to be identified as the sitter of the painting in the Met with any degree of certainty. All that can be said for certain is that the sitter of a Portrait of a Man in a Red Cap is a man who worked for Henry VIII in some capacity at Court.

Assuming the portrait is not of Horenbout, I wondered at the possible motivation for commissioning the exquisite and expensive portrait. Tudor portraits famously contain all manner of contemporary symbolism to convey messages, most lost on us today. But we do know that Tudor portraits were commissioned for delicate negotiations such as engagements, as in the case of Holbein’s Jane Small in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, or to advertise wealth. Often, miniatures were used to broker and seal marriage deals, most famously of course in the case of Holbein’s gorgeous miniature of Anne of Cleves of 1539. Despite the image’s appeal, Henry VIII later dubbed its unfortunate sitter the ‘Flanders Mare’, stating he had been misled by the painting.The portability of a painting, usually in an integrated frame, was therefore crucial, and the painting in the Met is thought to have originally had a protective fitted ‘cover’ for preserving the painting and aiding its transport.

Conjecture and a sheer absence of any facts in this case allows me to guess at the possibility that this young Court Official was announcing in the costliest, showiest terms that he had available to him that he had ‘made it’ at Court; that he was a ‘good catch.’ As indeed he may have been; King Henry VIII famously rewarded his officials handsomely, far more than other noblemen would have paid to their retainers. To an official who worked hard, and well, there was also the promise of promotion, lodgings, ‘bouche’ of Court, and the right to receive tips or perks (unused food or clothing, for which there was always an eager market.) To hold a job at Court was seen as prestigious, and secure. There was even a certain expectation of a pension in old age.

If this Official was doing well enough to engage Holbein to capture his likeness, then he would indeed have made a promising marriage-match for some hopeful family. We can imagine the painting being sent out, carefully wrapped, to Kent or Surrey perhaps, or even further afield.If, in the unlikely event that this was commissioned by the Official for himself, then he commissioned well. For, unless he was attached permanently to one of Henry VIII’s great palaces, he would have found himself on the move a great deal; Henry VIII’s Court was famously an itinerant one, and in the 1530s the Court was averaging thirty moves to different houses and palaces per year. One can only imagine the repacking and packing the Court Officials found themselves involved in, a staggering feat that sometimes saw up to 3,000 people on the move at once; a truly portable Court. Such a painting (with its clever size and protective cover) would have been handy, when, at a moment’s notice (as could happen in times of political unease or plague,) a Courtier found himself having to throw his belongings into his knapsack or trunk, ready for another journey.

This painting is of course too large to be listed among the tiny miniatures painted by Holbein to be worn as a type of jewel, given as a sign of love. Legend has it that an irate Anne Boleyn tore a jewel from the neck of her supplanter, Jane Seymour, and found within it a miniature of the King, given to Jane by the King himself. And while it does not have the pathos of Horenbout’s tiny painting of a declining, night-cap-wearing Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond, or the mystery and intrigue of any of the miniatures of Henry VIII’s wives (the identity of some of which are still the subject of debate), I am sure that to the man who commissioned it, and possibly to the person who received it, the Portrait of a Man in a Red Cap was a rare jewel indeed.L.B.Hathaway

LB Hathaway is a Cambridge-educated British writer. Her Tudor thrillers, Cape Scarlett and The Night Crow (set at the Court of Henry VIII) will be released in 2014 as the first two novels of a Trilogy. Her non-fiction book Henry VIII: The Roaming King – the Tudor Court on the Move will be released at the end of 2014. For questions or quotations in support of the above, please contact her on:

Hathaway_lb@yahoo.comor follow her on twitter- @LBHathaway

Published on December 09, 2013 04:04

November 21, 2013

Aspiring Historians: Be a Guest Blogger.

This coming December, I'm going to be offering a few guest slots on my blog. If you are an unpublished, aspiring historian or simply have a passion for history and would like to write a piece on a topic of your choice, it could published here and shared for a wide audience.

The topic is up to you, whatever you find fascinating: it can be an article or review, about a person, place, event, book, or theme, with the focus on women's history. I'm looking for pieces around 500-1,000 words but will consider longer ones too. If you're interested, send me a reply telling me in a sentence or two what you'd like to write about and why.

Alternatively, you can contact me via facebook on my In Bed with the Tudors page, or via twitter @PrufrocksPeach

I look forward to hearing your ideas.

The topic is up to you, whatever you find fascinating: it can be an article or review, about a person, place, event, book, or theme, with the focus on women's history. I'm looking for pieces around 500-1,000 words but will consider longer ones too. If you're interested, send me a reply telling me in a sentence or two what you'd like to write about and why.

Alternatively, you can contact me via facebook on my In Bed with the Tudors page, or via twitter @PrufrocksPeach

I look forward to hearing your ideas.

Published on November 21, 2013 04:28

November 18, 2013

A Modernist Voice from the Warsaw Ghetto

Everyday Jews: Scenes from a Vanished LifeYehoshue Perle

The New Yiddish Library, October 15 2013

Hailed as a modern Yiddish masterpiece and dismissed as too bleak to be possible, this new translation of Perle’s 1935 autobiographical novel Everyday Jews belongs in the same tradition as Gorky’s My Childhood and Joyce’s Dubliners.

Exploring the harsh reality of life for a poor family in a provincial Polish town around the year 1900, this story’s focus and subject certainly place it within the remit of literary modernism but not at its heart. Direct and unblinking, it looks the conditions of poverty and abuse in the eye; the terrible snow storm in which the adolescent narrator passes out, his parents’ dysfunctional relationship and the older women who seduce him. It is bleak and shocking. Like Dubliners it captures a dying way of life, wrapping up family occasions and customs in a sort of breathless stasis that some readers may find suffocating.

And yet it is compelling, in a grim sort of way. The writing is lucid and accessible and Perle carries the reader through the various miserable scenes of his early existence with ease. Dostoevskian in places, its imagery and description are simply yet powerfully constructed, building symbolic landscapes of misery. In the Joycean model, though, it is more a collection of still lifes than a progressive narrative. There is little development beyond the passage of time; the dumb mute peasant figure stumbles on, little understanding his destiny or actions. We see the family constrained by customs, such as the day permitted for house removals or oppressed by the pictures hung in the house they have rented from Christians. Only at the end, very briefly, does Perle suddenly open a door, telling us that something had changed for his narrator, some rite of passage had been reached. Yet this remains unclarified and signals the book’s abrupt end.

The characters may not undergo much of a developmental arc but they are vividly depicted, perhaps mostly so in the case of his mother, with her nostalgia for her first marriage and civilised city life, her soft double chin and ebony wigs with a curl on the forehead. Her spirit continues to reassert itself, fighting against the conditions into which she considers she has fallen and the aspirations she still entertains. Easily the most compelling figure of the book, she is exceptional amongst the other characters in the depth of her portrayal, as we see her pragmatism when faced by her step-daughter’s miscarriage, then dancing with pride at the girl’s wedding. The continual struggle between husband and wife, the ongoing battle of man and woman, does not descend into a simple gender battle but is delineated as one part of a complicated and compelling marriage. Among their extended family, what emerges here is a sense of shared destiny, through good and bad.

As an insight, a mirror held up to a lost way of life, this book is fascinating and does have real literary merit but read it as a series of vignettes of poverty in early Twentieth century Poland, a reflection of life and character rather than an analysis. It works best as a series of sketches rather than as a novel. Perhaps in this element of its style, as well as its subject matter, it comes closest to being a Modernist text.

Perle was a fascinating figure, born in 1888 and dying in the Warsaw ghetto in 1943. He published Everyday Jews in 1935, looking back to memories of his childhood as Europe's decade was darkening. Those early criticisms, that the book was too bleak to be psychologically believable are unfounded; placed in the Modernist tradition it fits like a missing jigsaw piece. This new translation captures a bleakness and constant struggle for survival that will be like a slap in the face for the twenty-first century reader.

Buy the book here: http://www.amazon.com/Everyday-Jews-Scenes-Vanished-Life-ebook/dp/B00FFQOAZ0/ref=tmm_kin_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&sr=&qid=

Published on November 18, 2013 08:16