Larry Brooks's Blog, page 20

September 18, 2014

Case Study: When Your Concept Disappears

From my chair, sometimes it seems like folks encounter the “What is your concept?” question, and then they scramble for an answer. They conjure something conceptual, or what seems conceptual in that moment.

As if the weren’t ready for that question. Hadn’t considered it. This is part of the value of the analysis process, it shows you what you don’t know about your story, but should.

Usually they know the next question asks for their premise, and they’re pretty comfortable and ready for that one.

And they quickly forget about what came before it. In that case…

Too often, the two answers — and what follows — don’t connect.

You can identify a concept (perhaps in the moment, in retrospect), but when you get down to the business of describing your story that concept leaves the building.

Because it was never there in the first place.

Which leaves the story without a conceptual layer, something that is appealing before and separate from the characters and plot themselves.

A missed opportunity, that. And when the concept was there, however briefly, and then disappears, it’s a fumble, resulting (using football jargon here) in a turnover.

Which in this case usually costs you the ballgame.

Check out this case study, you’ll see how this fumble looks in print.

Click on this link — SF Concept Case 9-18 — to read a short Kick-Start Concept/Premise analysis where this is precisely what happened.

The learning is this: notice how potentially compelling the concept is, as a story landscape. And then, how less than compelling the premise becomes when it fails to harness the inherent power of that concept.

A concept is a promise to the reader: you will enjoy the contextual landscape of this story, because it empowers the story.

It’s a promise you should make from an informed basis, and when it comes to pitching your work, definitely not one you should break.

*****

Want to see if your concept and premise are playing well together?

Click HERE for the skinny on my Kick-Start Concept/Premise Analysis. If you can find a better $95 investment in your story — because your story depends on this — please tell me where it is.

*****

The free Deadly Faux deconstruction ebook (114 pages of workshop-worthy stuff) is still available. Click HERE to learn more.

Case Study: When Your Concept Disappears is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The post Case Study: When Your Concept Disappears appeared first on Storyfix.com.

September 14, 2014

Story Deconstruction: “Remember Me?” by Sophie Kinsella

A guest post by Jennifer Blanchard

Spoiler Alert: This deconstruction dig deeps to break down the novel. The story will be fully exposed. This process provides a great opportunity to follow along when reading the book and see how a badass story is put together.

There are a lot of things at play in this story, which is why I chose to deconstruct it.

At a surface level, we’re led to believe that it’s a story about a woman who gets in an accident and loses her memory of the last three years (a plot not unlike many others that have been done before, think: The Vow with Rachel McAdams and Channing Tatum). But there’s a lot more to it than what the surface presents.

There has to be, because that alone (a woman getting into an accident and losing her memory) isn’t compelling enough for a story. There has to be more.

To quote Larry, a story needs…

“A hero with a problem and/or an opportunity. We need a reason to invest in it on an emotional level, something we can relate to. We need something specific to root for, as well as feel. We need conflict and tension, a confrontation between what the hero wants and does, and what opposes him or her on that path, something more than “inner demons” (which are useful when they influence that the hero does about the problem he/she faces… rather than simply documenting how those demons feel along the way). And most of all — because this will make us care and root — we need to understand what is at stake for both sides of confrontation.”

A good story is not a documentary of a situation.

A good story takes us on a journey with the hero toward resolution through confrontation, action, courage, cleverness, risk taking and the conquering of both interior and exterior antagonists.”

When it works, there is an antagonist and/or antagonistic force at play. There must be stakes that the reader can relate to, prompting an emotional investment. The hero has to want something and be willing to get it no matter the cost. As the reader would, vicariously, if in that position.

Remember Me? is actually a love story. But you’d never guess that, at least not ’til much later in the story.

And with that, let’s begin the deconstruction…

The Hook

As with most great stories, there’s a Hook that occurs very early in the narrative, often the first chapter, sometimes the initial few pages. This moment is there to set up the story that’s to come.

In Remember Me? there seems to be two hooks. The first is the Prologue, which introduces and positions a protagonist named Lexi Smart, and her group of friends. We find out they’re going out for drinks and dancing—which they do every week—except this time they’re celebrating that they just received bonuses at work. Well, everyone except Lexi. She’s the only one who didn’t get a bonus.

It’s the night before her dad’s funeral, and her boyfriend had just stood her up. Her life is kind of a mess. Not to mention she feels ugly and unworthy because she’s got a few extra pounds on her, snaggly teeth, and frizzy hair.

The prologue ends with the protagonist tripping down a flight of stairs and falling—hard— while running in the rain for a taxi.

Then in Chapter One we find our same protagonist in the hospital. At this point we’re being led to believe that this is the same night (or the night following) her trip down the stairs. But then something happens.

An additional little Hook appears, on page 19 (an early inciting incident), which changes everything (and introduces what’s to come in the next part of the chapter). Lexi is in her hospital bed talking to the nurse and she says, “Wouldn’t it be great if just once, just one time, life fell magically in place?”

Immediately following this sentence we get the Big Hook: Lexi glances down at her nails and they’re perfectly manicured. This doesn’t seem like something out of the ordinary, except that Lexi has never had manicured nails—her nails are always bitten down to stumps, as they were back in the Prologue.

Suddenly we’re hooked. Something’s going on.

The fall from the Prologue doesn’t appear to be syncing up to why she’s in the hospital right now. We have to read on to find out what will happen next.

That’s the mission of a good Hook—to set up the story to come and to keep you turning the page (or watching the movie).

Part One Exposition

Now Kinsella continues to unfold the story. Lexi goes on to discover that she looks totally different—her teeth are perfect, her hair is long and silky, she’s slender and toned, her purse is Louis Vuitton. But she doesn’t recognize herself.

All she remembers is the Lexi from the Prologue (snaggly teeth, bad hair, broke). She has no idea how she got to look the way she looks right now.

We also find out why she’s in the hospital—she got into a minor crash in her Mercedes convertible. Of course, this is more set up, because Lexi from the Prologue never could’ve afforded a car like that.

And the story set up keeps unfolding: Lexi is married to a handsome, rich home builder; she’s the Director of Flooring at her company, she lives in a fancy, expensive loft that overlooks London.

We’re being set up for the story that’s to come, a lot of which is being shown in Part One. Or so we think…

The First Plot Point

The First Plot Point (FPP) happens on page 79—it’s the final scene of Chapter 6 (and it falls at the 20th percentile in the story—exactly where it should). We find out that Lexi has amnesia—and can’t remember the last three years of her life. Now this isn’t coming as a huge surprise to Lexi—or the reader—but it’s still a shift of what’s been in play for the course of the first 78 pages. It, in effect, launches the core story spine of the novel, after these 78 pages of set up. (Not all FPPs are in-your-face, some are subtle, but still just as powerful.)

The FPP defines what’s at stake for the remainder of the story. It put an antagonist into play (or at least implies one) who needs to be defeated.

In this case, the FPP defines the antagonist (her amnesia) and the stakes for Lexi for the rest of the story (she now has to piece her life back together and try to figure out what the hell she’s going to do).

In that same scene her doctor tells her the best way to try and recover her memory is to fall back into her life. She decides to go home and live with her husband after she’s discharged from the hospital—even though he’s a total stranger to her.

Part Two Exposition

The FPP has shoved Lexi into Reaction mode (which is the context of every scene in Part Two—this is important for character arc. In Part Two of the story, the Protagonist is a “Wanderer.” reacting to the FPP). Now she’s gotta go home and re-learn about her life. Of course, when she goes home it’s to an enormous, posh, high-tech loft that overlooks London.

But the more she learns about her life, the more she realizes she doesn’t recognize this new Lexi. She discovers that she changed her looks completely and then went on a reality TV business competition show, which is where she met her now-husband. She drinks wine and only wears neutral colors.

None of this is the real Lexi, though. (The real Lexi being the one we met back in the Prologue.)

During this part of the story we’ve also started to get hints that something’s not quite right. Hints that Lexi’s “perfect life” with her “perfect husband” is not what it seems.

Lexi’s husband does odd things. He makes her a “Marriage Manuel” that tells her all about their life together, with specific details on everything from what they eat for breakfast to how they have sex. And he gets irritated with her over small things, like leaving her shoes in the bedroom instead of putting them in her dressing room.

It’s pretty obvious that whoever she was before the car accident is the exact opposite of who she is now.

We also get a hint of something else that seems questionable: Lexi is trying to park her new car, but she can’t remember how to drive (because old Lexi didn’t drive) so she almost crashes again. A guy appears in the parking garage and yells at her to hit the breaks—literally. This happens at the end of Chapter Eight.

The guy recognizes her, but she doesn’t recognize him. He seems suspicious of her and her amnesia—he alludes to her faking it. They have an awkward exchange, he doesn’t mention his name and then quickly vanishes.

Around the middle of Part Two we get a little blip of what Lexi was really up to before the accident. That something shows up at Pinch Point One.

Pinch Point One

It turns out that Lexi had somehow snapped back three years prior, and decided to become super ambitious with her career. She changed everything about herself and somehow alienated all her friends in the process. Except now she can’t remember doing it or why she did it. She figures if she connects with her friends, maybe she’ll remember everything.

On page 150, she’s still reacting to the First Plot Point (finding out about her amnesia) and we find her chasing her friends out of the office building, trying to see if she can go to lunch with them. They have an awkward exchange and one of the friends tells her, “We don’t hang out with you anymore. We’re not mates.” (Before this point she had no idea that she was no longer friends with the people from the Prologue.)

That’s Pinch Point One: a reminder of what’s at stake for Lexi now that she’s back to her old self (from the Prologue). She’s got a lot of work to do if she’s gonna win her friends back.

The Midpoint

I love the Midpoint in this book, because there’s another moment that happens about 32 pages earlier than the actual Midpoint that feels so much like it’s the actual Midpoint, except it’s not. Because it doesn’t fulfill the contextual mission of the Midpoint story milestone.

The Midpoint is there to “part the curtain,” revealing new information and shifting the direction of the story. (It’s also what shifts the protagonist from Wanderer to Warrior, more on that in the Character Arc section below.)

So on page 169, Lexi has a bomb dropped on her.

She and her husband are hosting a dinner party, and one of the dinner guests—the guy from the awkward parking garage scene— corners her in the kitchen and tells her they’ve been having an affair—and are madly in love.

Boom! Lexi’s world starts to crumble a little. A very powerful moment… but it’s not the actual Midpoint. This illustrates that, in addition to the primary (and rather fixed) major story milestones, we can inject other “plot twists” as we please to serve the story’s exposition.

It’s not the “official” Midpoint because we didn’t get quite enough information yet for this to shift the story in a new direction. Nope, this little gem of a moment is just set up moment for the Midpoint to come.

Lexi is still Reacting in this part of the story. She’s got new information that was dropped on her in the form of a plot twist. But she’s still not ready to Attack. She’s still not ready to take action on this whole amnesia thing.

She’s still biding her time, pretending like this all might magically go away and her memories will simply resurface on their own.

Then comes the actual Midpoint of the story.

Lexi’s been Reacting to the news that she may be having an affair. She’s been searching for clues, trying to avoid the guy even though he keeps trying to talk to her about it, and feeling really confused about the whole thing.

Up until this point in the story, Lexi doesn’t know whether to believe what this guy is telling her about the affair or not. (The old Lexi was not the cheating type.) Then the two of them run into each other at a walk-through for her husband’s new home launch (her husband builds expensive loft-style homes that overlook London).

Her husband asks the guy to give Lexi a tour of the building (because he’s the architect who designed the building so he knows everything about it). Lexi and the architect, Jon, are walking through the building on their tour and they end up in an upstairs bedroom, away from everyone else.

Again Jon is trying to convince Lexi that he’s telling the truth, and that they love each other and had plans—she was going to leave her husband for him. Lexi gets flustered and doesn’t know whether to believe him or not.

Then, on page 201, as Jon is talking to her, he grabs her hand, holds it in his for a minute and then begins softly tracing circles on her skin with his thumb.

Suddenly she can’t move.

Her “skin is fizzing; his thumb is leaving a trail of delicious sensation wherever it goes.” She can feel prickles going up the back of her neck. She doesn’t want to him to let her hand go.

Now that’s what I call a Midpoint.

This one little moment—him grabbing her hand—has changed the entire story. Lexi has had no memory return whatsoever so far in the story… but her body remembers his touch.

We’ve shifted into a whole new context for the story. Because now Lexi has a reason to get her memory back; she has a reason to start taking action to figure this whole mess out.

We have now entered Part Three of the story.

Part Three Exposition

Immediately following the Midpoint Lexi starts taking action (which is precisely according to the principles of story structure). Whereas

before she was just sitting around letting her new life flood in, hoping her memory would return, now she’s actively trying to make it come back.

She watches the DVD from her reality business TV show and sees herself—a crazy bitch-boss-from-hell who she totally doesn’t recognize. So when she goes back into work she starts doing nice things for everyone, to try and prove that she’s different now. She buys gifts for her friends, she tries to rally the troops into a fun outing…but no one’s buying it.

Her old ways are still biting her in the butt. Hard. She’s got a lot more work to do if she’s gonna overcome those outer (and inner) demons.

Things are still really strange with her husband—she broke something and he actually invoiced her to pay him back for it. She’s tried becoming more intimate with him in hopes of unlocking her memories, but that doesn’t go well, either.

Not to mention this love affair that she’s supposedly been having. Of course after what happened at the walk through, she’s kind of eager to find out what’s really been going on.

That’s where Pinch Point Two comes in.

Pinch Point Two

This time we find Lexi at the launch party for Blue 42, the new home model her husband’s firm is launching.

After bumping into Jon again and talking for a minute, he gets asked to do a quick favor for the interior decorator—the rocks for her fish tank display arrived late and need to be tossed into the tank in the master bedroom before the tours of the home begin.

Jon asks Lexi to tag along, and still curious as to why she’s feel this energy between them, she goes with him. When they get upstairs to the bedroom, he again launches into more discussion about the love between them.

And then it happens. Pinch Point Two.

He’s telling her things about their life together, to try and jog her memory. He mentions sunflowers, mustard on fries, but she’s still blank. So he tries something physical.

First he kisses her neck and asks if she remembers it. She tells him to stop, but she doesn’t mean it. She can barely get the words out. She wants him to kiss her, in a way she didn’t want her husband to.

Then he does (the kiss is Pinch Point Two, bringing the core antagonist – her amnesia – back to center stage for a moment), and she’s losing herself in it. Even though she doesn’t remember anything, her mind and body are telling her this feels right.

This moment just ratcheted up the stakes big time. Now Lexi has to figure this whole thing out, if only to finally have an answer as to whether or not this affair is real. She’s starting to be swayed in that direction.

But there’s more to come. Some more pieces to the whole puzzle, and finally an answer as to why three years ago she suddenly changed everything about herself and got so driven to succeed at work.

The Second Plot Point

Now technically, according to story structure principles, the Second Plot Point should land at the 75th percentile of the story (but pushing up to the 80th if need be). This story technically breaks that principle (often the case, in a legit way, because the demands of the story trump the paradigm at this point… as long as you’re in the ballpark), because the Second Plot Point actually shows up just a little past the 80th percentile (which is in the ballpark). What we’re seeing in this book is an extended Part Three.

That’s the great thing about these story principles. Once you learn them and know how to use them the right way, then you can push the limits when the story needs it. (That said, it’s not something recommended for new authors or authors trying to get traditionally published… stick to the basic principles.)

Because of the extended Part Three, Part Four is just a little bit shorter than the other parts of the story. But overall it’s still very balanced scene-wise and information-wise.

This story has a lot of set up for the Second Plot Point. In fact, there’s so many mini plot twists going on it’s almost hard to pick out which one is the actual Second Plot Point.

That’s when you have to look to the contextual mission of each part of the story. That will give you the answer. The contextual mission of Part Three is Attack (in Part Four it’s Resolution). So as long as the protagonist is still Attacking and acting like a Warrior, we’re still in Part Three of the story.

So we have Lexi decide to finally meet up with Jon and hear the entire story—how they met, what happened between them, what’s been going on with her work stuff, why she lost her friends, everything. That’s when she discovers that she was still the real her, she just faking it because she went “too far too fast” with the total transformation, and alienated everyone in the process.

We keep getting little drips of information about what happened back three years ago… all leading up to the final bit of information.

That’s the thing about the Second Plot Point. It’s the final piece of story structure and the final place where new information can enter the story. After this moment whatever shows up must have been foreshadowed earlier or be a shift of something that’s already in play.

Here at the Second Plot Point we find out what happened three years ago, before Lexi went off the deep end, changed everything about herself, and became hellbent on succeeding no matter the cost.

Lexi was attending her dad’s funeral (back in the Prologue the funeral was the next day) and the bailiffs showed up to bankrupt her and her mom and sister. Lexi’s boyfriend came to the funeral to support her, but she ended up catching him having sex in the bathroom with a waitress. And when the waitress saw Lexi she took one look at her and called her “Dracula” (think back to Lexi being upset about having snaggly teeth).

Suddenly everything makes sense to Lexi. She now sees what could have driven her to become the person she’s been for the past three years (even though she no longer remembers any of it ).

Now she’s ready to become the Martyr. Now she’s ready to fix the problems at work, win her friends back and reclaim her life, regardless of what that may look like (and who may be missing from it).

Welcome to Part Four: Resolution.

Part Four Exposition

Now Lexi finally has all the facts. She’s figured out why she became what she became. She now also believes without a doubt that she was having an affair with Jon and that she isn’t in love with her husband at all.

Lexi has become the Martyr—she’s now willing to do whatever it takes to save her department at work, win her friends back and make a decision about what to do with her whole marriage-affair situation.

(I won’t tell you all the specific details of the ending… you can find them out when you read it yourself.)

In the end Lexi saves her friendships (though not the department at work—but she does manage to start a brand new company and employ her friends). She also chooses to walk away from both relationships—the husband and the affair—and to find herself again.

Then at the very end, she has a faint but powerful memory of her and Jon together, and she knows that means it was meant to be, so she goes to him and makes things right again.

Character Arc: Lexi Smart

The Protagonist in a story goes through four different phases that coincide with the Four Parts of Story (Part One: Set Up, Part Two: the Reaction, Part Three: the Attack and Part Four: the Resolution).

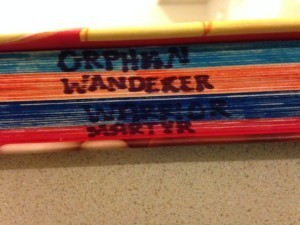

The four phases of character arc are: Orphan (Part One), Wanderer (Part Two), Warrior (Part Three), Martyr (Part Four).

In this story, Lexi goes through the same four phases. Here’s a description of each of them and how the plot points shift her into each phase.

In Part One of the story, the Set Up, Lexi is just an “Orphan.” She hasn’t been “adopted” by a journey. Yet. She’s just at the hospital, dealing with the things that are happening, but with no real purpose or mission.

But at the First Plot Point, when she finds out she has amnesia and can’t remember three years of her life—that’s when she’s “adopted” by a journey. Now she has to figure out what the hell she’s going to do; now she has to piece her life back together.

This moment shifts her from “Orphan” to “Wanderer.”

Because the context of Part Two is “Reaction,” the Protagonist is then “wandering” around, making plans, hiding out, trying to determine what to do next.

So Lexi is wandering around, getting reacquainted with her life, learning what she does every day, discovering what she’s been up to the last three years, etc.

Then the MidPoint happens, and Lexi discovers her body remembers things that her mind forgot. Now she’s done reacting and being the Wanderer.

She’s shifted into Warrior and is ready to Attack, which is the

contextual mission of Part Three. Now she’s taking action on the problem, instead of being a bystander. She’s battling her inner and outer demons and starting to make some strides.

When the Second Plot Point hits, and we find out the final details of what happened back three years prior that made Lexi change herself and her life so drastically.

That moment shifts her into the final character phase. At this point she’s ready to defeat what’s been holding her back the entire story—not having her memory—and fix her life: get her friends back, figure out her marriage-affair situation. She’s ready to do whatever it takes at this point—which is what makes her the Martyr.

The protagonist always has to have an arc in the story and change from beginning to end. Lexi’s character are is a strong one and her attempts at resolution are hysterical and clever.

Definitely a must-read. Hopefully, one that now, using this deconstruction, becomes a clinic to help you wrap your head around why it works so well.

About the Author: Jennifer Blanchard is an author and writing coach who helps emerging novelists take their stories from idea to draft, without fear, distractions or disorganization. If you want more story deconstructions and resources to help you write stories that work, check out her story community, Write Better Stories.

*****

Want more deconstruction? Using a case study is one of the best strategies to understand the structure and nuances of story architecture.

Click here — PDF DF Inner Life — for a FREE 114 page ebook that deconstructs my novel, Deadly Faux (see the sidebar for a review/blurb that might convince you this is worth the time).

Story Deconstruction: “Remember Me?” by Sophie Kinsella is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The post Story Deconstruction: “Remember Me?” by Sophie Kinsella appeared first on Storyfix.com.

September 8, 2014

A Process-to-Product Success Story

This post wasn’t my first impulse where this story is concerned.

I’d like to share a story with you, submitted to me for evaluation by a Storyfix reader. A story that is so good, so shockingly professional in execution, that it’s empowering and motivating to behold.

But I can’t. Not yet. Here’s why… and here’s the next best thing.

If you’ve been with Storyfix fora while, you know that part of what I do is coach stories using several levels of analysis. In a world in which the traditional approach calls for submitting and reading an entire manuscript — and costs thousands of dollars — I’ve developed much more accessible strategies that yield 99 percent of the same visibility and resultant analysis and coaching value.

You don’t have to cut open the body to diagnose a problem in need of repair, to stop the bleeding, as it were. They have MRIs for that… this analysis process does the same for your stories.

In this case, we added a biopsy, which served to solidify the verdict: we have a perfectly healthy winner.

More than healthy, this story is on steroids.

This writer opted for what I call the “First Quartile Analysis,” which includes the Part/Act 1 of a story submitted with a Questionnaire about the rest. It’s only $450, and yet is every bit as effective as reading and evaluating the entire story… at a fraction of that cost (which begins at $1800).

Everything one needs to do to an effective story shows up in the First Quartile, up through and including the First Plot Point. If it doesn’t, then the story — and possibly the writer — isn’t ready.

I’ve done nearly 600 story evaluations (in one form or another) in the last 2-plus years, of which several dozen were these First Quartile submissions. Among those 600, only three were ready for submission to an agent or a publisher (IMO).

Scary stats, that. But that’s not to say the others were badly broken. About 20 or so were a tweak or two away, build on solid conceptual ground.

The rest were — well, badly broken is too harsh… let’s just say, they needed significant work. Those writers heard what they needed to hear, what they paid to hear, and the ball went back into their court.

But this story, submitted by Eagan Daws, was by far the best thing I’ve ever read by an unpublished author.

I wanted to write about the story in this post.

To break it down for you. Expose its stellar concept and the powerful premise that springs from it. Dissect the First Quartile structure, which includes three killer inciting incidents, introduces an intriguing hero with a massive problem on his hands, and sets up the introduction of really intimidating antagonism with massive, unthinkably dark stakes in play.

And, then, a game-changing First Plot Point, which is the most important moment in any story.

All of it written with the touch of an experienced pro, from a concept we’ve never seen before (take note, that’s key). Ready to publish now. Every bit as good as what you’ll read from Demille, Childs, Joe Hill, or even his father (who is a guy named Stephen King).

Mark my words, this story will be published.

I often write about the value of seeing work-in-progress as a case study in how weak or missing principles are what is holding it back. Just as valuable — though orders of magnitude more rare — is seeing those principles totally nailed, with an evolved story sense driving them.

So I pleaded with the author to allow me to shine a light on this story.

He was, as you might imagine, pretty pleased with the feedback. In fact, he had no idea how good his story was, because he’s been wrestling with it in the planning and drafting stages for some time (a lot of learning from that, as well).

But he wants to wait. To finish the draft itself. His call, and I’ll honor it.

Instead, he offered to share his process with you.

As a case study in keeping the faith, staying true to the principles of craft, and listening with a keen ear when feedback arrives.

So what follows are his words, about that process. He has agreed to allow me to showcase the story’s bones at a later date, which I’m looking forward to. But for now, take heart in the success of one writer who gets it, and allowed the craft to fill his creative sails and propel him closer to the goal.

This never was about him endorsing me. The reverse is more accurate. But he’s lived the promise of a principle-driven, criteria-dependent process, and there’s immense value in experiencing that from his point of view.

From Eagan Daws, author:

The Larry Brooks approach to story coaching has basically allowed me to get unstuck and proceed with what I intend to be a 100,000-word novel. That’s a big deal and I spent some time trying to figure out what in particular worked in order to exploit it even more effectively. Here is what I came up with. It probably needs one of those “these views are solely those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect…” kinds of disclaimers.

I first encountered Brooks/Storyfix through Writer’s Digest and that led me to “Story Engineering,” the premise of which, as I read it, is that effective, satisfying stories follow the same, necessary structure, and you can, in fact must, learn to use it to make your story work. Cue the megawatt light bulb. It all made sense to me, the four major parts, the seven milestone moments, Larry’s descriptions of how these worked in the overall narrative.

Back to the keyboard! Hook. First Plot Point. Midpoint, Second Plot Point. Even those pesky Pinch Points. I worked away, but not much was happening. I was struggling as before to write from Point to Point, so to speak.

Damn. Was Brooks another failed writing guru? No. I was a poor student.

As I worked with the model, I began to realize I would have to approach the Brooks structure from another point of entry — the four big boxes, Setup, Response, Attack and Resolution. I started with the Brooksian “What if…” question and began to generate things that might happen, putting them in one of the four boxes while being mindful of Larry’s definitions of the plot points and their functions. The major boxes as defined in the Brooks approach proved specific enough to allow me to sort out the action, but loose enough to let me work through refinements.

The thing for me, then, was sequence — thinking first about what goes on in the story, then about where it goes in the four segments, then understanding and refining the plot points, and then the pinch points.

The engineering idea worked beautifully. It wasn’t even a metaphor. I was building something against a set of loose but vital specifications. Scenes become, if not fully fungible, then certainly movable. I have moved scenes and combinations of scenes between first and second segments, and I suspect the same will be true of the third and fourth segments. Plot points can slide left and right, as well, still following Larry’s guidelines on the appropriate percentile.

Using an effective structure in no way inhibits the writer’s imagination, just as meeting the engineering requirements of building construction doesn’t prevent an architect from designing a great building. Frank Gehry’s buildings are no less artful because he knows how to build them so they don’t fall down.

I should say here that I did not get to this point unassisted. I used Larry’s Conceptual Kick-Start Story Analysis ($95) not once but twice. The combination of structure and analysis from Larry was necessary.

I came to realize I could get my head around a 100,000-word narrative. This was the moment when I first felt confident I would produce an effective story at that length. Was I right about it being a big deal, at least for me?

Eagan Daws

A Process-to-Product Success Story is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The post A Process-to-Product Success Story appeared first on Storyfix.com.

September 2, 2014

The Six Great Epiphanies of Successful Authors

I love this word: Epiphany.

It comes from the Greek word epiphneia, which means apparition, in reference to the manifestation of a supernatural or divine reality.

The more contemporary definition, one of four contexts, is:

A sudden, intuitive perception of or insight into the reality or essential meaning of something, usually initiated by some simple, homely, or commonplace occurrence or experience.

In other words, an Epiphany is something that was right in front of us all along.

So it is when it comes to writing our stories.

It represents an opportunity, born of a recognition of the truth.

A truth that may have been holding you back because you weren’t fully acknowledging it, a truth that may propel you further and faster once you do.

When it comes to writing effective fiction, there are a handful of Epiphanies that await. And while the A-list authors you worship may or may not ascribe their success to them, or describe them in this way (as shown below) if they do, they nonetheless practice the craft of writing in context to them.

Every time, in one form or another.

So what do they know that we don’t?

While that’s perhaps a grievously black-and-white way to phrase the question, we can boil it down to a few key awarenesses, skills and belief systems – truths – that elevate stories to a consistent level of effectiveness.

But take caution, because these truths are subtle.

So subtle you might easily dismiss them, or naively believe you already align with them. If you’d prefer to wait a decade to crawl out from beneath a truckload of rejection slips to see the truth and value they represent, that’s an available option.

Or, you can inject them — force-feed them if you have to — into your conscious recognition of what creates successful fiction right now… in a world in which 990 of every 1000 stories written are not yet at that level.

That statistic in itself can and should ignite an Epiphany or two, or five… or at least clear the way for these truths to become one for you.

Here’s what successful authors understand at the very core of their writing souls:

1. They see craft, or the absence of it, in everything they read.

Perhaps the best way to elevate our storytelling craft — once we believe we have internalized the essences and structures and forces of story — is to go out and look for them and acknowledge them in the stories we read and the films we watch.

The enlightened pro sees craft (as structure and narrative forces) in every story, either as an asset or a diagnosis. They become Dr. House in a hospital full of suffering patients… one glance and they can explain why.

An analogy is in order here.

Let’s say you play golf with someone who is pretty good. To you their swing is beautiful and perfect. They are a 5-handicap, which is darn good, way better than yours. You can’t see a single thing this person is doing differently than the touring pros you watch on TV… and yet, you know that a 5-handicap doesn’t come close to being good enough to be one of those players.

And yet, a golf pro can look at the same swing and see what’s wrong, and what’s strong, right away. They can’t miss it. Why? Because they understand the game at a level of resolution that civilian golfers don’t.

Same with storytelling. You need to be the pro that sees and understands what works, and what doesn’t. Not just as an observer/reader, but as a practitioner who can apply that awareness to your own work.

The Epiphany is when you know you can do just that.

There are specific lists of criteria, benchmarks and levels that define those essences, and thus, the true Epiphany. The pro understands that list, the unenlightened writer either denies or under-appreciates them, preferring to just write.

“Just write” might be the most toxic advice a new writer can hear. Sadly, it’s among the most common pieces of so-called conventional wisdom out there. Some people “just write” for decades and never get anywhere.

It doesn’t matter if everyone in your critique group is crazy for your story. What matters is what an agent, an editor and ultimately what readers will think about it. The reading experience is very different than the writing experience, and the difference resides in those subtleties and essences.

In my work as a story coach, about two-thirds of the stories that come in are from authors who believe they’ve nailed it. The other third is from writers who know they haven’t and want clarity on what could be better.

Which means, most writers don’t know what they don’t know. And that gap will block their path until they do finally, truly, know.

A deep dive into the building blocks of craft (the six core competencies, and the six realms of story physics), will lead you toward a heightened awareness that is reinforced by seeing it out there in the real world.

Once you see the craft, you can’t unsee it. Seeing is believing. And unless you are content to rely on luck, or place your bet on your own intuitive storytelling sense (which, ironically, is the product of knowing craft) believing is required to reach the goal.

2. They dwell at the intersection of concept and premise.

The enlightened pro understands that the bar is high. That you can’t make a cow’s ear idea into a silk purse story (perhaps the most common downfall of the newer, unenlightened writer). That a story needs to have compelling energy at its very core, at the concept and premise level.

That particular assessment – what is compelling, what isn’t… or worse, what is compelling only to you – is the difference between successful published authors and those who, however fine their writing, can’t seem to break through.

A story was sent to me recently in which a man (the hero, for whom we were being asked to empathize with and root for) talked himself into believing that he could not achieve happiness until he bought his father’s drugstore. Which required him traveling to the third world to resolve a centuries old mystical question in order to raise the money to accomplish). The author believed that others would find this notion, this concept, compelling. I disagreed. There is absolutely nothing conceptual, and thus, compelling, about this idea. It was too contrived, it jumped lanes, it was highly unrelatable.

Click HERE for a roster of 13 articles on this topic, to see the difference between a concept and a premise (yes, Virginia, there is a difference, and it is critical), and what qualifies as compelling via the various of levels of story physics involved.

3. They understand what burns at the core of an effective story.

I refer to these story forces as story physics, and there are bunch of them (six, in fact). The most important, though, is already on the table and not remotely a new revelation: dramatic tension.

No drama, no story. Period. Conflict, the source of dramatic tension, is the most important and consistently essential element in all of fiction.

The mistake of the newer, unenlightened writer (pre-Epiphany) is when they focus on character (common in romance), time/place (common in historicals), or theme (common in all genres)… to the detriment or even the exclusion of conflict-driven drama that defines the expositional spine of the story.

In other words, not who your hero is, but what your hero does.

The Epiphany is this: the core dramatic question posed by the setup of the story is the element that defines its viability. Not a tour of the hero’s psyche, not a journal of their tormented background, not a Rick Steves-esque outline of the destination/setting and its beauty and historical significance… but rather, what happens to the character – what they need or want, what opposes and challenges them, and what’s at stake.

When a reviewer refers to a book as “a novel of Ireland,” they aren’t suggesting that the book works because it so vividly imagines Ireland, the place. Rather, when it works, it will be about what HAPPENS to someone in Ireland. Reviewers almost always miss this, and thus contribute to the misinformation that requires an Epiphany to correct.

It boils down to this:

A successful story is never just ABOUT something – a character or a place or an event in history. Rather, a successful story is always about something HAPPENING within the arena of a character’s life, or a place, or an event in history.

The awaiting Epiphany arrives when you completely understand the meaning and implications of those two sentences.

Do that, just that, and you will immediately be among the top ten percent of unpublished writers everywhere. It’s that important and empowering.

4. They understand the true nature of characterization.

You could state the previous entry as this, even though this is slightly different: enlightened writers understand that character is not the centerpiece of story. Oh horrors, your college lit professor is throwing his glass of fine Scotch against the faculty lounge wall as we speak.

But it’s the truth when it comes to commercially viable fiction in today’s market.

Rather – and this is subtle – the essential element of character is empowered by what he/she does in a story, what they decide, what actions they take, and how they conquer obstacles, both interior and (most importantly) exterior… all in context to what hangs in the balance as the stakes of those decisions and actions.

The Epiphany isn’t that character is less important than you believed it be, but rather, the means of showcasing and exploring character is different than you believed it to be.

Wrap your head around that, just that, and you will immediately be among the top five percent of unpublished writers everywhere.

An episodic journal of your hero’s life is destined to fail… unless and until each portion (episode) of the story is infused with dramatic tension. Not something that the reader simply notes and observes, but is emotionally engaged with to the extent they are rooting for an outcome.

I told you it was subtle. It takes some writers decades to get this one down. This Epiphany, a moment of clarity, will get you there quicker.

5. They understand the difference between a draft and a final draft.

The process of writing a story (novel or screenplay, even a short story) always breaks down into three linear phases:

a. The search for the story.

b. The development of the story, once defined.

c. The polishing and optimization of the story.

All processes – planning, plotting, pantsing, or a hybrid approach – engage with these three phases. Often the lines between them are blurry, allowing the writer to jump from phase to phase.

Dangerous, if you aren’t aware of what this means. Joyous, when you are.

Again, an Epiphany is required.

The Epiphany is this: the writer is completely aware of, in command of, the fact that they haven’t yet found the best and complete story. And thus, they are completely aware of which of the three phases they are currently engaged with. They understand that they are still in the search for story phase.

The opposite — when you have moved on to developing an undiscovered and incomplete story — is where the abyss awaits. That’s like trying to wallpaper the rooms in a house in which the concrete of the foundation is still wet.

Only when the search is complete can you then develop and optimize the story you have found.

Let’s say you’re a pantser. You write organically, with only a vague notion of where the story is going… you are counting on the story appearing before you as you go. Fine, go for it.

This is a viable process, but extremely risky if you are, in fact, less than enlightened about what is required before a story works.

So there you are, writing away, when suddenly – let’s say, around page 140 – everything about the story changes for you. A lightbulb flashes. Muses descend on clouds of hope. You find a different and better path for the story. A completely different ending. Maybe even a new hero emerging from the crowd.

And so you change lanes and keep going, finishing the book from that moment of clarity, writing in context to that clearer vision.

That draft, the one in which you did this, won’t work. It absolutely works as a process – as a means of completing the search for the story – but not as a viable draft.

A truly final, optimized draft will always be written in context to a fully-formed story… beginning, middle and end. Especially the end.

The enlightened writer gets this. They know and accept that they’ve used the draft as a tool in the search for story phase. And now that they’ve found it within that draft, they know they are now in the second phase, which is the development of the story across the four-parts and seven key milestones of its structure.

They know what those parts and milestones are, too, and where they should appear within the next draft, which will be a lot closer to “final.”

The unenlightened writer, however, who doesn’t understand all this, proceeds to implement a polish to that half-and-half draft and then stamps “FINAL” on it.

The Epiphany comes – if, in fact, it manifests at all – when the rejection slip arrives and the writer is open to being shown what went wrong.

6. They know how the game (publishing) is played, and they play to it.

The Epiphany here is the realization that established writers with proven history and a contract are held to a different standard than new writers seeking to break in. Many of which give up the fight and self-publish, thus cluttering this emerging segment of the equation with sub-par product.

If you are one of those established writers, chances are you are already post-Epiphany, so the work you submit comes close to the mark. You also know, because you’ve already received half of your advance – that there is a floor full of editors somewhere (or a single person in a smaller house) that will help you fix whatever needs fixing.

The dark side of not understand this is the likelihood that you may, however subconsciously, be writing a book that is modeled after an author or a specific book you have read. It looks easy from your favorite reading chair, story seems like an accessible thing, so you intuitively try to write it “like Baldacci.”

I once knew a country gentleman doctgor, a guy who was always the smartest guy in every room he’d ever been in. One day he announced his retirement so he could write a novel. He was a Clancy fan, and he had a killer spy story tell. Two weeks later he was done with his first draft, which he submitted all over the place. The draft was 89 pages long.

Nobody ever told him what had gone wrong. Because nobody could tell him things like that. He was A Doc-tor, and he knew best.

He remains unpublished.

Epiphanies only come to those who are open to it. “Need” has nothing to do with it.

The things that work within a story are subtle and complicated. Hard to see… unless you’re enlightened to them, in which case you can’t not see it.

You could do an appendectomy with a knife and fork, too, and then sew up the incision and pop a beer. When you’re done it looks just like what they do on Grey’s Anatomy.

But the patient is going to die.

Storytelling, at a level required to compete in today’s market, is that complicated.

The Epiphany is understanding what that list of forces, essences and nuances are, and how they are playing in your story.

It can take a lifetime of assimilation to get there.

Or, you can simply go to the right resources — books and workshops and coaching and enlightened groups — and completely immerse yourself in the building blocks of craft.

And when you do, you’ll find yourself circling back to #1 on this list… you’ll see it in play everywhere, in every novel and film and TV show and story you read. And your writing world will be forever changed, thanks to that Epiphany… an awareness and body of knowledge that you’ll now share with every successful writer on the bookshelves today.

Of course there is a long list of other things that come into play.

But pretty much all of them are subordinated to these major truths. Each of which announces itself to you, over and over again along the writing road, until you see it. Until you get it.

Until your Epiphany arrives.

******

Sometimes an Epiphany only happens when someone, a qualified someone, reads your stuff and shines a harsh light of critical assessment on it, looking for the basic elements of craft and story physics in what you’ve done. It’s clarity that is hard to find in that context, and invaluable when you do.

This is the mission of my story coaching work. I have several affordable levels to offer… check the links above the header of today’s post, or read the descriptions in the right-hand column.

I can show you where the Epiphanies are hiding in your work. Not just what isn’t work, but why it isn’t working, and usually with a fix in mind.

*****

Click HERE to get a FREE 114-page ebook that breaks down and analyzes my novel, Deadly Faux, from the point of view of the author. My publisher (Turner) has discounted the Kindle edition of the novel to only $1.99 (again, the deconstruction ebook is free), if you’d care to experience this learning opportunity in context to the actual story.

It’s a well reviewed book so far (check out the blurb from James Frey in the right hand column ), built upon the criteria and benchmarks written about above, so it’s a win-win either way.

Hope you’ll take advantage of this while that discounted price remains in place (which is up to the publisher’s discretion).

The Six Great Epiphanies of Successful Authors is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The post The Six Great Epiphanies of Successful Authors appeared first on Storyfix.com.

August 18, 2014

Story Structure: a Graphic You Can Use

You are one click away from a useable, printable, post-able (as in, on your wall) graphic representation of classic 4-part story structure, including the 7 major story milestone transition “moments” within the story.

Get it right here: Structure Graphic.

In the previous post I framed this… as part of a Powerpoint presentation on the subject of: how to put your story on steroids. While the live version had he witty and passionate audio that assists in clarity, the slides stand alone as a tutorial with punch.

Some readers have commented that a few of the other slides (#24, #25 and #28 especially) are just as valuable, if not more so. As in: what you need to know about your story before it’ll work as well as it could, and in what order of priority.

Yes, that’s what I said. Steroids. A total shot in the petard of your story, to make it stronger, bigger, faster, better. It’s legal, too, an added bonus.

If you’d like to see that entire presentation, click here: Story on Steroids

Hope you find this useful.

*****

Click HERE to land a trifecta opportunity: 1) score a mystery/thriller with killer reviews for only $1.99 for the Kindle edition; 2) download a totally FREE, no strings ebook that deconstructs the whole thing, while going behind the curtain to see how this book, and many like it, find their way to market; and 3) snag a rare learning opportunity to go deep and see the principles in play via an in-depth case study.

Story Structure: a Graphic You Can Use is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The post Story Structure: a Graphic You Can Use appeared first on Storyfix.com.

August 16, 2014

How to Elevate Your Story Above the Eager Crowd

The “crowd” is pretty good, too. And they want what you want.

So you need to be better.

Greetings from Los Angeles, where I’m presenting at the Writers Digest Novel Writing Conference. I did two sessions yesterday, and later today I’m doing a workshop entitled: “Your Story on Steroids.”

This is why I like working with Writers Digest.

Not just because they publish my writing books and put my articles in their magazine (or that they sent me to China last month), they’re just cool, hip, really smart people. They allowed me to use this title, they got the analogy.

I’ve tried several times to get this title on the agenda at a handful of other conferences, who were scared off by the word “steroids.”

Ooo… scary. Steroids. Bad.

Sure, they’re illegal if you’re talking about anabolic medication. But not in this context, the context of writing really strong, compelling stories. In that context we need all the medicine we can get, and we need the science that makes it happen.

And it’s an analogy, folks… deal with it. It — in this analogous context — won’t make you sick and it won’t make your testicles shrink to the size of chick peas, nor will you go to hell for getting the analogy.

Anyhow, in preparation for today I’ve created a killer Powerpoint slide deck that doesn’t mince words. I’d like to share it with you, too. The people here paid for the live presentation and discussion, but the content is universal, and I’d like you to have it.

Get it here: Story on Steroids.

There’s a new structure graphic here, too (slide #32), that simplifies the four part, 7-milestone story structure model, worthy of printing out. For all your visual thinkers out there.

Because good doesn’t cut it these days.

Our stories have to be great to separate from the incoming stream of good stories, most of which will be rejected for precisely that: they are merely good, totally solid… but not great.

Publishers are looking for the next home run. Not the next book to take up a slot on a bookstore shelf.

Let’s be great today. Hope this helps.

****

Click HERE to land a trifecta opportunity: 1) score a mystery/thriller with killer reviews for only $1.99 for the Kindle edition; 2) download a totally FREE, no strings ebook that deconstructs the whole thing, while going behind the curtain to see how this book, and many like it, find their way to market; and 3) snag a rare learning opportunity to go deep and see the principles in play via an in-depth case study.

How to Elevate Your Story Above the Eager Crowd is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The post How to Elevate Your Story Above the Eager Crowd appeared first on Storyfix.com.

August 8, 2014

The Value of “Pantsing”

(Click HERE to land a trifecta opportunity: 1) score a mystery/thriller with killer reviews for only $1.99 for the Kindle edition; 2) download a totally FREE, no strings ebook that deconstructs the whole thing, while going behind the curtain to see how this book, and many like it, find their way to market; and 3) snag a rare learning opportunity to go deep and see the principles in play via an in-depth case study.)

A Guest Post By Jennifer Blanchard

Since the very beginning of StoryFix, Larry has written about a term he calls “Pantsing,” which is when you write a story by the “seat of your pants.” Doing so, without doing any planning ahead of time, will almost always result in a full-draft rewrite (likely multiple draft rewrites).

But you’ll be a lot closer to knowing what your story is about.

Larry is obviously a huge advocate for story planning—as am I—but I’ve actually received emails from frustrated writers who are upset that Pantsing isn’t taken more seriously.

So I wanted to make a case for Pantsing having a valid place in the storytelling process.

Because that’s the thing about Pantsing. While it might not give you the draft of a story you can use (as will outlining; Larry also stresses that pantsing and outlining have the exact same goals), it will give you clarity on what your story is truly about.

And that, in and of itself, via either method, is gold.

Here are the benefits of Pantsing:

• Story Discovery—when you’re in Pantsing mode, you can go crazy writing whatever comes to you with regard to your story. You can write the details that inspire you most about this story idea; you can write dialogue for an important scene, to see how it could play out; you can write entire paragraphs describing everything from people to locations.

The Story Discovery Phase of writing a story really requires you to dive in and figure out what story wants to be told, who these characters are, and what their story really is. All of which are absolutely things you need to know if you want the draft to work as well as it possibly can.

It’s likely that by the time you enter the Planning Phase of your story, you won’t even recognize your initial idea seed. And that’s OK.

In his book, On Writing, Stephen King talks about how discovering what your story is really about is kind of like excavating the ground looking for fossils. He says:

“Stories are relics, part of an undiscovered pre-existing world. The writer’s job is to use the tools in his or her toolbox to get as much of each one out of the ground intact as possible. Sometimes the fossil you uncover is small; a seashell. Sometimes it’s enormous; a Tyrannosaurus Rex with all those gigantic ribs and grinning teeth. Either way, a short story or thousand-page whopper of a novel, the techniques of excavation remain the same.”

• Getting to Know Your Characters—Pantsing is a great way to get to know your cast of characters. And since you’re still in the Story Discovery Phase, you can go crazy writing your characters’ backstories; learning more about who they are and what they want; and digging deep into what their motives are in this story.

• Having A Writing Adventure—writing a novel is an adventure in itself, but Pantsing is truly an adventure, because you have no idea where you’re going. You’re just sitting down and typing whatever comes to your mind. The direction of your story is not yet defined, and anything is possible. This can be a lot of fun, if you let it.

The problem, however, is that too many writers don’t realize Pantsing is just a PHASE in the process of writing a story—but it’s not the only phase.

You really can’t just Pants your novel and expect it to work. That will, in nearly every case, never happen.

The only thing that works is having a plan, knowing your structure, and being able to clearly articulate a beginning, middle and end.

In that context, a “pantsed” story that succeeds in identifying a powerful core story is a plan, the goal having been arrived at using means other than outlining or using yellow sticky notes.

A Balance of Both

Like I said, Pantsing does have its place in the draft-writing process. But it’s only the first phase in the process, if you choose to not begin the story via an outline.

If you want to write a novel that you can publish, you have to push yourself to move past the Pantsing Phase (aka: the Story Development Phase) and into the next two phases: Planning Phase and Doing the Writing Phase. At that point there is no difference whatsoever between what the pantser is doing and the planner is doing, because when you reach those second and third phases the “core story” has been identified, using either process.

(You can learn more about the 3 Phases of Writing A First Draft here.)

You’ve gotta have a balance of Pantsing and Planning (and Doing the Writing), if you want to end up with a novel that’s worth putting out into the world.

The reason I often spend more time in the Planning Phase than I do in the Story Development or Doing the Writing Phases is because I have no desire to write more than one draft before finding what my story is about. I’ve tried that and it just doesn’t work for me. If I have to write more than one full-draft, I usually scrap the story.

But when I plan everything out ahead of time, and then write the draft, I have a lot of stuff I can actually use when I’m finished. And that allows me to avoid a full-draft rewrite.

Writing a novel that works isn’t science; there’s no specific success formula you can use or replicate. But there are principles in play, and a three-step process that will help you turn out a truly badass first draft.

How does Pantsing play a part in your story-writing process?

About the Author: Jennifer Blanchard is an author and writing coach who helps emerging novelists take their stories from idea to draft, without fear, distractions or disorganization. Her Idea to Draft Story Intensive—where she helps you take your story idea and turn it into a completed first draft—is enrolling right now.

The Value of “Pantsing” is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The post The Value of “Pantsing” appeared first on Storyfix.com.

August 4, 2014

A Great Read… a Learning Opportunity… a Massive Discount

A Major Price Reduction… and a FREEBIE, too!

Here’s something you’ve never seen before:

A well reviewed novel… written by a bestselling novelist who is also the author of bestselling “how to write novels” books… offered at a 75% DISCOUNT (Kindle version)… that includes a FREE 114-page “how it was done and what you can learn from it” ebook.

Which like the novel is also, according to readers, pretty entertaining.

The novel is question is mine – “Deadly Faux,” published last year by Turner Publishing. Check out the reviews on Amazon (that’s the link I just provided), and look to the right on this page to find the cover image, and read the adjacent blurb provided by James Frey, the hard-to-impress author of the iconic writing book, “How To Write a Damn Good Novel.”

The price of the Kindle edition of “Deadly Faux” has been temporarily reduced as part of this promotion — to $1.99 (it’s practically free).

Because we believe that once you read it, you’ll tell others and you’ll want more. (“Deadly Faux” is the second novel in a series, the first book being “Bait & Switch,“which was on the Publishers Weekly list of “Best Books of 2004,” (also their Editor’s Choice in the month of release) and which has been newly re-released by Turner.

Yes, we’re trying to hook you with the discount, but sincerely believe that once you’ve had a taste of “Deadly Faux” and its quite cinematic hero, Wolf Schmitt, that you’ll come back for more.

Here’s an idea: if you’re in a critique group, or even a reading group, consider grabbing this deal for your folks, because the deconstruction ebook makes a great discussion guide on the good stuff of writing a novel.

And speaking of more….

When an author assures you “my book is really good… trust me on this“… well, I think the reviews and that blurb say it better and more powerfully than I can. So please reference those.

But, as they say in those cheesy infomercials – “But wait, there’s more!” Which this case is true.

If you’re reading this, you’re a writer, too.

One who is looking for more information, more cutting-edge thinking, more case studies and examples, on how to write better stories. And there’s always the curiosity (sometimes cynical) to see if “this guy walks the talk.”

So with that in mind, I’ve written an in-depth deconstruction of “Deadly Faux” that not only provides an entertaining behind-the-curtain look at the harrowing road this novel traveled to publication last October, it also tears it apart, quartile by quartile, milestone by milestone, to provide a transparent model (both process and product) of how the novel is constructed according to those principles, and why.

And thus, you will come away with an even higher, clearer understanding of the tools, criteria, targets and benchmarks involved in creating an effective story.

The reviews on that have been amazing, too.

There are no strings here. You can have the deconstruction ebook, “The Inner Life of Deadly Faux,” at no cost. In fact, you can have it right now, right here as a PDF (which you can download to your Kindle) — click on this link and it’s yours — PDF DF Inner Life.

Of course, a deconstruction/analysis/case study is most valuable when you read the novel itself, before or after doesn’t matter. And at $1.99 for that novel, we’ve made it easy. Deadly Faux is available in trade paperback, as well (at the regular price), so you do have a choice in that regard.

Good books need good readers to start a buzz and shoot for a viral breakout. I’m hoping you’ll relate to that, and give “Deadly Faux” a shot… both as a reader and as a writer who will benefit from the “learning” that this accompanying ebook will provide.

Thanks for considering. At $1.99, it’s a no-lose situation – or, better put, a win-win proposition — and I appreciate your support.

Larry

*****

In a workshop state of mind?

Consider the Writers Digest Novel Writing Conference, held in Los Angeles on August 15 – 17, at the Hyatt Regency Century Plaza. A massive slate of A-list novelists and teachers, something for everybody, and in a big way.

I’ll be teaching three workshops… two at the “main” conference… and a 3-hour “intensive boot camp” session on Friday morning. The boot camp is a $99 add-on to he conference fee, a bargain by any standard.

For the main conference website, click HERE.

For the Boot Camp/Intensive page, click HERE.

Hope to see you there!

A Great Read… a Learning Opportunity… a Massive Discount is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

The post A Great Read… a Learning Opportunity… a Massive Discount appeared first on Storyfix.com.

July 30, 2014

The Epidemic and Systemic Sabotage via Brainwashing of Aspiring Novelists

As a writing coach and author of writing books and articles, I deal in numbers. Volume. Significant databases of writers and stories. Manuscripts, story plans, synopses, samples, story analysis and the hands-on witnessing of stories under development. And I’m here to tell you…

… there’s trouble in River City. I see it, I read it, every single day.

Too many of today’s writers don’t really understand what a “story” is.

I know, that’s a heretical thing to say. String me up and throw books at me, the ones that don’t tell you everything you need to know, or how it is in the real world.

But based on what I see, the stories I’m paid to read and evaluate, this story-thinness is too often the case. Often enough, in fact, to sense a trend, the presence of a career-killing writing virus that is the single most significant factor in why people can’t get their novel published.

The “story” just isn’t strong enough. In many cases, it’s not even a story at all. Even if the original idea has merit, the ensuring premise and the story built from it may not.

I’m on an airplane as I write this, heading to a Big Time writing conference, where I’m slated to present three workshops and — more germane to this post — sit down with 13 writers to go over their manuscript samples.

Add that to my coaching work, for which I’ve read over 500 story plans and dozens of full manuscripts in the past two years. All of it sort of mushes together in my head, leading me to a depressing conclusion.

Which is… somebody out there is leading our aspiring writers right into the dumpster. Where they got the idea that the stories I’m seeing – a much too large a percentage of them – are actually “stories” in the truest, most literary and commercial sense of the word, is beyond me.

It makes me sad, actually. These stories represent dreams and aspirations. Somebody has to say it: you need a better handle on what a good story IS… and what it ISN’T.

There are some terrific prose stylists out there pounding away, for sure. But eloquence and tricked out narrative won’t get you published. Not even close. In today’s market story trumps… everything…including your sentences, and — here’s the rub — including your characters.

Which is why we need to know what a story is… and what it isn’t.

Just showing us a character, from all sides and angles, does not a story make.

It’s as if these folks had all just emerged from a summer camp on “writing a literary novel” (perhaps with “M.F.A.” somewhere in the header) under the assumption that the ONLY thing that counts is “writing about a character.” Never mind giving that character something to DO, something that matters, or providing the reader with something to root for, via the unfolding of a dramatic plot.

Writing art… a noble pursuit. But writing for readers commercially… that’s a completely different ballgame. Thing is, too many aspiring to the latter are adopting the mindset of the former.

Somebody slept in on the day when the teacher told the class about CONFLICT being the most important element of fiction. Even in literary fiction, where the hero needs to be doing something — besides living their life — that the reader can relate to and empathize with.

Not a whole bunch of different episodic glimpses of conflict, the only connection between which is the fact that they feature the same protagonist… that’s a diary, a biography, not a story.

“All the stuff that happened to Bob that made him the man he is today…” is not a story, either. Not in a commercial sense.

Where do we get our notion of what a story is, and what it isn’t? Books, workshops, writing groups, something your freshman lit teacher said, blind naivete… I’m not sure. But it’s out there, and it’s killing dreams right and left.

Maybe those of us standing in front of the room aren’t doing enough talking about the right things. The things that make a story work at its most basic, fundamental level.

Most of us cover it, though, leaving me dumbfounded as to the source of this virus. Even writing teachers who aren’t big fans of structure — and there are plenty of ‘em – usually emphasize that dramatic tension and escalating exposition (versus episodic exposition) is what makes a story tick.

It’s what makes a story a story.

Today’s aspiring novelist, it seems, wants to “write about the life of a character.” Period. It just sounds so… literary. Very impressive in the foyer as we trade pitches over shrimp and cocktails.

And thus, we keep getting pitched the life story of a fictional character.

Which — somebody forgot to tell them along the way — almost never works. Because we (the readers) have no reason to care, there’s nothing to root for, very little with which to engage on an emotional level.

For all of that to happen there needs to be a PLOT.

There, I said it. A good story needs to have a PLOT. In one form or another. A bunch of smaller plots, told in sequence… isn’t a novel. It’s a biography of a fictional character. It’s a collection of short stories featuring the same protagonist.

Not a novel.

Unless you’re writing something to pass a class taught by a “literary author,” this is a true statement. If you want to publish your work in today’s market, you must have dramatic tension in play across the full arc of the story.

My conclusion — and it’s the most drastic, dramatic thing to say out loud in this business, to a room full of aspiring writers — is that too many aspiring writers today don’t really understand what a STORY is, at its most fundamental level. A real story, not just a character profile that spans the decades of a protagonist’s life.

That while you can certainly sit down and write about anything you want, you can’t expect anything and everything to be the raw material for a compelling novel with commercial plausibility.

Nobody seems to have the balls to tell these writers that they don’t have a STORY there. Which, if this is the case, is the most loving, timely and helpful thing they absolutely need to hear. Tell them that their story is thin on at least three of the six essential core competencies of fiction (you need ALL SIX of them for the story to work), and almost all of the six realms of story physics, which is the raw energy that makes any story work..

The life story of a fictional character is the most common case in point.

It’s all there, in the premise.

But there are other story killers that reside at the premise level, and until the premise changes there’s really no chance at making it come alive on the page. Such as: a killer concept leading to a lame premise. A vanilla premise with nothing conceptual about it at all. Or a complete mangling of the story’s structure in the name of “there are no rules.”

There aren’t. But there ARE principles, and they’ll sink you if you play too loose with them.

My favorite example of what a real story looks like, despite being well written, character-driven and thematically rich (the intoxicants of the literary-minded, and thus, the seductive alternative to plot), is the bestseller The Help, by Kathryn Stockett.

I get push-back that actually claims this novel is an example of “just a story about some characters living their lives, that it really has no plot, and look what happened. It’s all about the characters.”

Look again. Somebody isn’t reading the damn thing closely enough.

Because there is a significant PLOT at work in The Help, propping up and driving the thematic weight of the story as it fuels the entire thing… from providing a framework for all that stellar characterization and arc, to giving the hero (Skeeter, as the primary protagonist, and Aibeleen as a major enough player to claim co-protagonist props) something to DO in the story, a purpose, a mission, a quest, a problem to solve… something the reader will ROOT FOR because it is emotionally resonant, which the life story of a fictional character isn’t), all of it with massive stakes and significant opposition always in play.

Notice that this novel ISN’T “the life story of a colored maid in 1962 Jackson, Mississippi.” It’s a concentrated drama unfolding over a concise period of time.

Harry Potter? Totally plot-driven. With a great hero.

Jonathan Franzen’s books? Read them again… there’s a plot in every one of them.

Many well-intended “life stories of fictional characters” claim to have drama, but when you look closely it is delivered in chronologically-segregated chunks, as a series of vignettes that are, in essence, nothing other than short stories from the protagonist’s life, many of which are never resolved and have absolutely no drama. They just happen.

If you believe a “story” is simply a collection of words and scenes that feature a character, that give us a documentary and/or a chronology of something that happened as an isolated diary-entry from a fictional life… then go ahead, call it a “story” if you like.

Just don’t say it to an agent or an editor.

This is the type of assignment you received back in your creative writing class — write about something that happened to you, or happens to a character.

Fine. Learn to write scenes, that’s a good thing. But a scene is not a novel, and a series of scenes that aren’t parts of a connected plot spine aren’t a novel, either.

Character arc is not plot.

But somewhere along the line writers have come to believe they can just string these episodic chapters together and call it a novel… without a central dramatic arc… without a front-to-back contextual need or problem or mission driving the character… without giving the reader something to root for.

All this, under the assumption that the reader will be content to look in at it, as if peering through aquarium glass with voyeuristic pleasure. Or worse, to marvel at the symmetry and beauty of your prose.

If Skeeter didn’t need to write that book about the maids in Jackson, you have no novel. Perhaps more certainly, you have no mega-bestselling novel.

If the goal is to pass a writing class, to score a good grade and a comment from the teacher that “you write really well,” then sure, go for it. It’s good practice for writing scenes.

But that isn’t the game you’re in now.